#i came up with ming after changing two letters in link

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Had this in my drafts for a while and forgot about it, but I been pondering this info

It definitely makes sense that ravio wouldn't be his real name since it's just two words related to his appearance mashed together,, I wonder what his potential real name could be

#ravio#loz#definitely not baiting u guys into giving ur ideas haha#since there's a two letter difference between hilda and zelda#i came up with ming after changing two letters in link#hilda and ming.. cute#🧿#🛡️

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

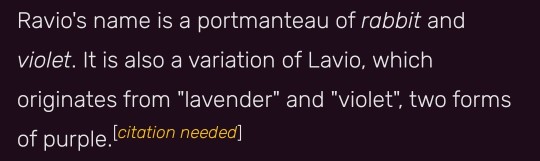

THE FUNERAL OF SALVATORE RICCIARDI: Celebrating a friend and comrade, while taking over public space again

WU MING

A final farewell to Salvo, to the songs of Su, communists of the capital! "This rebellious city, never tamed by ruins and bombings…"

Of all the measures taken during this emergency, the ban on funeral services is among the most dehumanizing.

In the name of what idea of "life" have these measures been taken? In the prevailing rhetoric of these past few weeks, life has been reduced almost entirely to the survival of the body, to the detriment of any other dimension of it. In this there is a very strong thanatophobic connotation (from the Greek Thanatos, or death), a morbid fear of dying.

Thanatophobia has permeated our society for decades. Already in 1975, the historian Philippe Ariès, in his landmark History of Death in the West, noted that death, in capitalist societies, had been "domesticated", bureaucratized, partly deritualized and separated as much as possible from the living, in order to "spare [...] society the disturbance and too strong emotion" of dying, and maintain the idea that life "is always happy, or at least must always look like it”.

To this end, he continues, it was strategic "to shift the site where we die. We no longer die at home, among family members, we die at the hospital, alone [...] because it has become inconvenient to die at home". Society, he said, must "realize as little as possible that death has occurred". This is why many rituals related to dying are now considered embarrassing and in a phase of disuse.

Even before the state of emergency we are experiencing, the rituality of dying had been reduced to a minimum. That is why we have always been so impressed by the manifestations of its re-emergence. Think of the worldwide success of a film like The Barbarian Invasions by Denys Arcand.

Forty-five years ago, Ariès wrote: "no one has the strength or patience to wait for weeks for a moment [death, Editor's note] that has lost its meaning". And what does the 2003 Canadian film depict if not a group of people waiting for weeks - in a context of conviviality and re-emerging secular rituality - the passing of a friend?

Eight years ago we undertook, together with many others, to set up an environment of conviviality and secular rituality around a dear friend and companion, Stefano Tassinari, in the weeks leading up to his death and in the ceremonies that followed. Much of our questioning on this subject dates back to that time.

If the rituality linked to dying was already reduced to a minimum, the ban on attending the funeral of a loved one had finally annihilated it.

Back on March 25th we shared a beautiful letter from a parish priest from Reggio, Don Paolo Tondelli, who was dismayed at the scenes he had to witness:

"And so I find myself standing in front of the cemetery, with three children of a widowed mother who died alone at the hospital because the present situation does not allow for the assistance of the sick. They cannot enter the cemetery, the measures adopted do not allow it. So they cry: they couldn't say goodbye to their mother when she gave up living, they can't say goodbye to her even now while she is being buried. We stop at the cemetery gate, in the street, I am bitter and angry inside, I have a strong thought: even a dog is not taken to the grave like this. I think we have exaggerated for a moment in applying the rules in this way, we are witnessing a dehumanization of essential moments in the life of every person; as a Christian, as a citizen I cannot remain silent [...] I say to myself: we are trying to defend life, but we are running the risk of not conserving the mystery that is so closely linked to it".

This "mystery" is not the exclusive prerogative of the Christian faith nor of those possessing a religious sensibility, since it does not necessarily coincide with the belief in the immortal soul or anything else, but something that we all ask ourselves, when we ask, 'what does it mean to live?' 'What distinguishes living from merely moving on or simply not dying?

That said, those who are believers and observers have experienced the suspension of ritual ceremonies - including funeral masses - as an attack on their form of life. It is no coincidence that among the examples of clandestine organization that we have heard about these days, there is the catacombal continuation of Christian public life.

We have direct evidence that in many parishes the faithful continued to attend mass, despite the signs on the doors saying they were suspended. One finds the "hard core" of the parishioners in the refectory of the convent, or in the rectory, or in the sacristy and in some cases in the church. Twenty, thirty people, summoned by word of mouth. In particular last Thursday, for the Missa in coena Domini.

The same can be said of funerals. In this case as well we have direct testimonies of priests who officiated small rites, with close family members, without publicity.

In the past few days, we have identified three types of disobedience to some of the stupidest and most inhumane features of the lock-down.

Individual disobedience

The individual gesture is often invisible but occasionally it is showy, as in the case of that runner on the deserted beach of Pescara, hunted by security guards for no reason that has any epidemiological basis. The video went viral, and had the effect of demonstrating the absurdity of certain rules and their obtuse application.

Continuing to run was, objectively and in its outcome, a very effective performance, an action of resistance and "conflictual theatre". Continuing to run distinguishes qualitatively that episode from the many others which offer "only" further evidence of repression. As Luigi Chiarella "Yamunin" wrote, the video brings to mind,

"a passage from Crowds and Power by Elias Canetti on grasping, which is indeed a gesture of the hand but also and above all is 'the decisive act of power where it manifests itself in the most evident way, from the most remote times, among animals and among men'. Later, he adds - and here comes the part pertinent to the episode of the runner - that 'there is nevertheless a second powerful gesture, certainly no less essential even if not so radiant. Sometimes one forgets, under the grandiose impression aroused by grasping, the existence of a parallel and almost equally important action: not letting oneself be grasped". The video [...] reminded me how powerful and liberating it is not to let yourself be caught. Then I don't forget that if you run away you do it to come back with new weapons, but in the meantime you must not let yourself be grabbed."

Clandestine group disobedience

These are the practices of the parishioners who organize themselves to go to mass on the sly, of the family members of a dearly departed person who agree with the parish priest to officiate a funeral rite... but also of the groups who continue in one way or another to hold meetings, of the bands who continue to rehearse, and of the parents who organize themselves together with a teacher to retrieve their children's school books. It's an episode that happened in a city in Emilia, which we recounted a few days ago.

In order to retrieve the books from a first grade school that had been left at school for the last month, a teacher came to the school, took the books out hidden in a shopping cart, and entrusted them to two parents who live near a baker and a convenience store respectively, so that the other parents could go and pick them up with the "cover" of buying groceries, avoiding possible fines. The books were given to the individual parents by lowering them with a rope from a small balcony and stuffed into shopping bags or between loaves of bread, as if they were hand grenades for the Resistance. In this way those children will at least be able to follow the program on the book with the teacher in tele-education, and the parents will be able to have support for the inevitable homeschooling.

After a phase of shock in which unconditional obedience and mutual guilt prevailed, sectors of civil society - and even "interzone" between institutions and civil society - are reorganizing themselves "in hiding". In this reorganization it is implicit that certain restrictions are considered incongruous, irrational, indiscriminately punitive.

Furthermore: at the beginning of the emergency, parental chats were, in general, among the worst hotbeds of panic, culture of suspicion, toxic voice messages, calls for denunciation. The fact that now some of them are also being used to circumvent delusional prohibitions - why shouldn't a teacher be able to retrieve the textbooks left in the classroom? why should a dad or a mom have to resort to subterfuge, self-certification, etc. to retrieve those books? - is yet another proof that the "mood" has changed.

Provocative group disobedience

The performance of the trio from Rimini - a man and two women - who had sex in public places and put the videos online, accompanied with insults hurled at the police, is part of this rarefied case history.

The police have since held a grudge against the case, as exemplified by their official social channels.

The only thing missing from this catalog of disobedience is, of course...

Claimed group disobedience

Here we have in mind visible, and no longer merely clandestine collective disobedience.

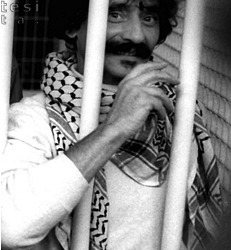

For a moment we feared that the fascists would be the first to bring it into play. Forza Nuova attempted to leverage the dismay of believers in the prospect of an Easter “behind closed doors,” and without the Via Crucis. However, when leaflets circulated calling for a procession to St. Peter's Basilica tomorrow (Sunday 4.12), accompanied by mottos such as "In hoc signo vinces" and "Rome will not know an Easter without Christ", they were dismayed to find that it wasn't the Fascists who were behind them. Instead, it was our comrades and friends from Radio Onda Rossa and the Roman liberatory movement who, this morning, in S. Lorenzo, greeted Salvatore Ricciardi with what in effect became the first political demonstration in the streets since the beginning of the emergency.

Salvatore Ricciardi, 80 years old, was a pillar of the Roman antagonist left. A former political prisoner, for many years he was involved in fights inside prisons and against prison conditions. He did so in a number of books and countless broadcasts on Radio Onda Rossa, which yesterday dedicated a moving four-hour live special to him. He continued to do so until even a few days ago, on his blog Contromaelstrom, writing about imprisonment and coronavirus.

Headlines about this morning's events can already be read in the mainstream press. A precise chronicle, accompanied by some valuable remarks, can be heard in this phone call from an editor of Radio Onda Rossa [here]. Among other things, our comrade points out: "here there are rows of people standing in front of the butchers shop for days and days, yet we cannot even bid farewell to the dead? [...] We're in the open air, while in Rome there's not even a requirement to wear a mask and yet many people had masks, and there were only a few people anyway"...Yet the police still threatened to use a water cannon to disperse a funeral ritual. The part of the district where the seditious gathering took place was closed and those present were detained by police.

During this emergency, we’ve seen so many surreal scenes - today, to offer just one example, a helicopter took to the sky, wasting palates of public money, in pursuit of a single citizen walking on a Sicilian beach - and even still, this morning's apex had not yet been reached.

For our part, we say kudos and solidarity to those who run, and are out running great risks to claim their right to live together - in public space that they have always crossed with their bodies and filled with their lives - out of pain and mourning for the loss of Salvo, but also out of happiness for having had him as a friend and companion.

"Because the bodies will return to occupy the streets. Because without the bodies there is no Liberation."

That's what we were writing yesterday, taking up the “Song of el-'Aqila Camp”. We reaffirm our belief that it will happen. And the government fears it too: is it by chance that just today Minister Lamorgese warned against "hotbeds of extremist speech"?

In her telephone interview, the Radio Onda Rossa editor says that the current situation, in essence, could last a year and a half. Those in power would like it to be a year and a half without the possibility of protest. They are prepared to use health regulations to prevent collective protests and struggles. Managing the recession with sub iudice civil rights is ideal for those in power.

It is right to disobey absurd rules

We should point out once again that, whilst keeping a population under house arrest, while prohibiting funerals, and de jure or de facto preventing anyone from taking a breath of fresh air - which is almost a unique phenomenon in the West, since only Spain follows us on this - and while shaming individual conduct like jogging, going out "for no reason", or shopping "too many times"...while this whole little spectacle is going on, Italy remains the European country with the highest COVID-19 mortality rate. Good peace of mind for those who spoke of an "Italian model" to be imitated by other countries.

Who is responsible for such a debacle? It is not a hard question to answer: it was the people who did not establish a medical cordon around Alzano and Nembro in time, because the owner asked them not to; it was those who spread infection in hospitals through an impressive series of negligent decisions; those who turned RSAs and nursing homes into places of mass coronavirus death; and lastly, those who, while all this was happening, diverted public attention toward nonsense and harmless behavior, while pointing the finger at scapegoats. This was blameworthy, even criminal behavior.

Everywhere in the world the coronavirus emergency has presented a golden opportunity to restrict the spaces of freedom, settle accounts with unwelcome social movements, profit from the behavior to which the population is forced, and restructure to the detriment of the weakest.

Italy adds to all this its standard surfeit of irrational ravings. The exceptionality of our "model" of emergency management lies in its complete overturning of scientific logic. For it is one thing to impose - for good (Sweden) or for bad (another country at random) - physical distancing as a necessary measure to reduce the possibility of contagion; it is quite another to lock the population in their homes and prevent them from leaving except for reasons verified by police authorities. The jump from one to the other imposed itself alongside the idea - also unfounded - that one is safe from the virus while "indoors", whereas "outdoors" one is in danger.

Everything we know about this virus tells us exactly the opposite, namely that the chances of contracting it in the open air are lower, and if you keep your distance even almost zero, compared to indoors. On the basis of this self-evidence, the vast majority of countries affected by the pandemic not only did not consider it necessary to prevent people from going out into the open air generally, as they did in France, but in some cases even advised against it.

In Italy, this radius is, at best, two hundred meters from home, but there are municipalities and regions that have reduced it to zero meters. For those who live in the city, such a radius is easily equivalent to half a block of asphalt roads, which are much more crowded than in the open space outside the city, if it could be reached. For those who live in the countryside, however, or in sparsely populated areas, a radius of two hundred meters is equally absurd, since the probability of meeting someone and having to approach them is infinitely lower than in an urban center.

Not only that: we have seen that very few countries have introduced the obligation to justify their presence outdoors by authorizations, certificates, and receipts, even calculating the distance from home using Google Maps. This is also an important step: it means putting citizens at the mercy of law enforcement agencies.

We have recorded cases of hypertensive people, with a medical prescription recommending daily exercise for health reasons, fined €500; or people fined because they were walking with their pregnant partner, to whom the doctor had recommended walking. The list of abuses and idiocies would be long, and one may consult our website for further examples.

Legal uncertainty, the arbitrariness of police forces, the illogical limitation of behavior that presents no danger to anyone, are all essential elements of the police state.

Having to respect an illogical, irrational norm is the exercise of obedience and submission par excellence.

It will never be "too soon" to rebel against such obligations.

It must be done, before it’s too late.

Translated by Ill Will Editions

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Mid-Autumn Festival

The Mid-autumn Festival originated from the custom of moon worship in the ancient China. And the custom of moon worships dated back to the Zhou Dynasty more than 3,000 years ago. The ancient emperor then regarded the sun as the masculine and the moon as the feminine. So, people would worship the lunar deity at night in the autumn of the lunar calendar. For thousands of years, such imperial sacrificial activities have gradually evolved into the folk moon worship and moon watching. Although the contents of this festival have changed since many dynasties passed, but its date on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month has seldom changed.

Why on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month?

There are several reasons for the Mid-autumn Festival was set on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month. First, from the perspective of natural condition, we take the 8th lunar month as the Mid-autumn Festival, for the seventh, eight and ninth lunar months being to autumn and the eighth is just in the middle. And the moon on the 15th day is especially round and bright. In the autumn, it is a little humid. But the humid would be driven away by dry and cold wind from the north. So, the weather at this period of time would be very fine and the moon is also especially bright.

What’s more, because we can see the full moon clearly, it’s easy for us to associate the moon with a relation among people and expect to reunite with relatives. Of course, this is also a harvest season when people would feel pleasant. In such a pleasant festival, people always wish the world could be perfectly satisfactory and families could gather together. All these factors make this festival be arranged in the Mid-autumn Festival.

Documented about the Mid-autumn Festival

About the Mid-autumn Festival, the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, there are many poems in the Tang Dynasty. It’s counted that in the “Complete Tang Poems”, there are 111 people with the title of “Mid-autumn Festival” or “the 15th day of the 8th lunar month”. In the Tang Dynasty. Actually, there was already the term, the “15th day of the 8th lunar month”, But, no documents have clearly stated that the Mid-autumn was a festival and how the people celebrated it.

Until the Song Dynasty, the books, “Dongjing Meng Hua Lu”, and “Meng Liang Lu”, clearly recorded that the Mid-autumn was already a festival in the Song Dynasty. It’s recorded that in the Northern Song Dynasty, on the Mid-autumn Festival, people would buy a lot of liquors. Sometimes, after a shop sold up its liquors, it would put away its signboard. All people celebrated this festival happily. And said that at that time, there were also some imperial tributes like grapes and mooncakes.

The “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance” 霓裳羽衣曲

The “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance” was praised as a melody that could only be heard in the heaven but rarely on the earth.

The melody is known as “the melody from the moon” is the “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance”, a classic of the Chinese Tang Dynasty. It’s said that the melody was composed by Li Longji, the Emperor Tang Dynasty, in the Mid-autumn Festival. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, the melodious sound of the “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance” would spread in the imperial palace every Mid-autumn Festival. It’s very vigorous, and it makes us calm. It’s very intoxicating as if we were in a fairyland on the earth.

Legend of the “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance”

One day, exactly, on a Mid-autumn Festival night, Li Longji, the Emperor of Tang Dynasty, was watching the moon very excited when suddenly he came up with an idea. He wanted to go to the moon. So he consulted the imperial astronomer. The imperial astronomer said no problem. So, he sent the emperor to the moon where he heard a melody and saw the dance of the fairies. Then, he became excited and memorized this melody.

On the way back, exactly, in Luzhou, today’s Changzhi of Shanxi Province. In the bright and clear moonlight, the whole world was quiet. Then, the emperor said, “Ah, how enchanting that melody and dance are!” The imperial astronomer said. “Why don’t you play this melody here with a jade flute? The emperor agreed. So he played this melody with a jade flute. Then, before he left, he and some attendants spread some money from their pockets in the Luzhou city. More than ten days later, the officials of Luzhou reported to the emperor that on the night of the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, they heard the melody from the heaven and picked some money. It was an auspicious sign.

It’s said that later the emperor asked the imperial astronomer. “Can I go there again”? The imperial astronomer smiled and said, only on the night of the 15th day of the 8th lunar month could the emperor visit the moon palace. So, in the folklore, the “Rainbow-Skirt Feathered-Dress Dance” and the 15th day of the 8th lunar month are linked together. So, in that time, in the Tang Dynasty, people already celebrated the Mid-autumn Festival on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month.

Three symbols of the Mid-Autumn festival (mooncakes, goddess of the moon and Rabbit God)

1, mooncake

1) when is the earliest time when mooncakes first appear? The earliest mooncakes appeared a long time ago. For some round foods, we called them “cake”. In those days, cakes were always baked, steamed or cooked in many other methods. As for its special name “cake”, it could date back to the Tang Dynasty. In the Tang Dynasty, it is said that after a general won battles, he brought some “hu cake” from the western regions. When the emperor and the queen (the Imperial Concubine Yang) enjoying the moon, they ate “hu cake”.

After eating some, they thought it was tasty. Then the emperor said to the queen (the Imperial Concubine Yang), this “hu cake” was so delicious but its name was not good. Could you change a name for it? The queen (the Imperial Concubine Yang) agreed and she looked at the moon which was round as the “hu cake”. So she said mooncake was good and it was better than “hu cake”. So some people say the name of the mooncake come from “hu cake”.

2) Why eat mooncakes during the Mid-autumn Festival?

There is a Chinese folk story about it. It is widely believed that in the late Yuan Dynasty, the massed began to raise a rebellion against the Yuan Dynasty. Zhu Yuangzhang, the leader of the insurrectionary army, prepared to ally various insurgent forces to attack the Great Capital of the Yuan Dynasty. But officers and soldiers were strict in checking contact letters, so it was difficult for them to pass on the message of rebellion. Liu Bowen, the military counselor in Zhu Yuangzhang’s army, came up with a plan that he proposed to hide scrips written with “Uprise on the Mid-autumn Festival Night” in cakes and then gave out cakes to those soldiers to inform them about the rebellion. On the Mid-autumn Festival, insurgent forces who had received cakes responded highly and the great capital of the Yuan Dynasty was occupied soon.

After Zhu Yuanzhang became the emperor, he was so glad that awarded “mooncakes” once used to pass on message secretly as gifts to all ministers. Therefore, there is a custom of eating mooncakes in Mid-autumn Festival. The fact is that its real origin is hard to know. But we can definitely say that the very time when mooncakes are used as sacrificial offerings is from Ming Dynasty.

In the Ming Dynasty, it is assured that people would eat mooncakes on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month.

2, Chang’e (a beautiful goddess of the moon) and toadBesides eating mooncakes in the Mid-autumn Festival, most people watch the moon. In China, there are many tales about the moon.

In “Classic of Mountains and Seas” exists description of the sun and the moon. It describes that a three-legged crow lives in the sun. So we usually call the sun Golden Crow. Simultaneously, “Classic of Mountains and Seas,” says that the moon is a toad, it is a symbol of the moon.

In fact, the toad was the idol for many tribes and ethnicities. It originated from such a fact that frogs are productive. And its stomach will be flat sometimes and be bulged in another time. Which is like the shape of waxing and waning of the moon. In ancient times, people worshiped toads. It mainly rooted in a kind of reproduction worship. Toads are very fertile. A toad can produce 5,000 spawns once. Therefore, in the view of the ancients, toads symbolized fertility and happiness.

Besides, they are nocturnal. Tradition has it that people treated them as the embodiment of the moon, and even think the Chang’e, the goddess of the moon flying to the moon and turned into a toad. So, almost all ancient women would worship the moon and the goddess of the moon in the Mid-autumn Festival to express their wishes of having more children and more happiness. Among the people, the tradition that “men don’t worship the moon” has been reserved all the time.

That’s also the reason why the ancient Chinese people also call the moon as the toad.

3, Jade Rabbit and Rabbit God on the moon, of course, we know there is a so-called Jade Rabbit

There’s a legend about the Jade Rabbit, that a plague hit the capital city one year. Many common people fell ill, and taking medicine was of no use. Chang’e, the goddess of the moon in the heaven felt very sorry for the common people suffering from torture, so she sent the Jade Rabbit to the earth to eliminate the plague. The Jade Rabbit cured the sickness and saved the patient from door to door, helping people go through the disaster. The Jade Rabbit didn’t ask return for its deeds of merit, and it only borrowed clothes from people to wear. So the Jade Rabbit had many images then. In order to thank the Jade Rabbit, people began to worship the Jade Rabbit as Rabbit God. The Rabbit God just became a target for ancient men and children to worship in the Mid-autumn Festival.

So people call it Rabbit God who is in the general’s costume. These above are its two long ears. It is in an embroidered robe, helmet. In general, it also rides on a tiger or other animals. Such a Rabbit God may not be a very serious and august object for worship from beginning to end. But it does give us a special and grateful expectation.

Chinese ethnic minorities

About twenty minorities celebrate the Mid-autumn Festival, such as the Axi people, a branch of the Yi people, celebrate it with dancing under the moon. When the Axi people dance under the moon, they form a circle, celebrating the Mid-autumn Festival in the most excited mood and happiest atmosphere. Their dance reflects their appreciation, worshiping and reverence toward the moon and expresses their gratitude to the harvest and the happy life as well.

Except for Axi’s dancing under the moon, a straw dragon dance in the Mid-autumn Festival prevails in some regions in Zhejiang Province. As for the straw dragon dance, it twists a large rope with straws first, and then bundles a dragon head and tail two ends of the rope, so that a dragon is formed. Plug burning incenses on the rope and villagers perform the straw dragon dance with burning incenses on the sunning ground. With the straw dragon dancing, sparks fly everywhere.

Reunion and Missing become the constant theme of the Mid-autumn Festival

From time immemorial, many poems about come down and have been appreciated by later generations. On a Mid-autumn Festival night, Su Shi (a great poet in Song Dynasty) drank a lot and got drunk heavily at that time, then he suddenly thought of his younger brother. So, he wrote a very famous poem of “Wishing We Last Forever (但願人長久)”. In this poem, although Su Shi expressed the sadness of toiling in obscurity, he further showed his endless yearning for his younger brother Su Zhe.

Wishing We Last ForeverWhen will the moon be clear and bright? With a cup of wine in hand, I ask the blue sky.I don’t know what time of the year, it would be in the palace on high. Though a thousand miles apart, we are still able to share the beauty of the moon together.

In the Mid-autumn Festival in A.D. 1076, the 41-year-old Su Shi hadn’t reunited with his families for seven years because of political exile. In the seven years, Su Shi held a variety of government positions throughout China. He had asked for transfer many times, hoping to be close to his younger brother Su Zhe. But this wish never came true. Being separated from families for many years made Su Shi miss families so much in this Mid-autumn Festival. Taking advantage of tipsy feeling and looking at the bright moon, Su Shi finished this Mid-autumn Festival masterpiece which has been handed down for thousands of years.

This poem depicts the moon and meanwhile, it expresses the yearning for families in the Mid-autumn Festival. He said, “Is it because men had made any mistakes, the moon tends to be full when our families were apart?” he thought of his brother, Then, without waiting, he said that maybe he shouldn’t think so, because men’s partings and reunions were like the moon’s waxing and waning. They are very common from ancient times to the present, it’s quite difficult for us to change them as we wish. At this moment, his sole aspiration was that we all could look at the moon and live in the world forever. The last line “Though a thousand miles apart, we are still able to share the beauty of the moon together”. The moon indicates Chang’e who is a very charming female, but in fact here we use it to stand for the moon. It said that we were at different places, though we were miles apart, we shared the same moon together. The moon will connect you and me as if we were together. So this poem must be widely recited in the Mid-autumn Festival.

Reunion and Missing

Finally, the Mid-autumn Festival, if we can use one word to summarize it, it would be yearning. This is a festival for missing. To miss our families, miss our hometown, and miss our motherland. Especially for the overseas Chinese, when they meet the day of the Mid-autumn Festival, the ethnic Chinese in various regions, whether the chamber of commerce or the natives association, they organize lots of celebration activities.

Actually, the reunion is the communication of emotions, namely, sense of identity. If we all have such kind of emotion, it is likely that our society will be harmonious. Regarding festival, we have a deep understanding. Knowing its history and a lot of stories about it, our feelings will be different. With such feeling, we will love it protect it and inherit it to create a new life. It is the significance of the festival.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essay on Malacca, introduction to the capture of Malacca.

In 1509, two years before the conquest of Malacca, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira recorded his observations on his arrival in the city-state in a letter titled On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands. Two years later, the city was conquered by the Portuguese. These provide a view of the city at the end of its golden age, just before its fall. This letter, along with examination of a variety of secondary sources including essays, monographs and articles about the city build an image of the cultural and economic makeup of Malacca at the start of the 16th century. This examination will look at the geography, national identity, religious makeup, economic core and geopolitical basics that helped define the city-state before conquest. Then Malacca after conquest under rule of the Portuguese will be examined. The Suma Oriental: Which goes from the Red Sea to China, written by the first Portuguese ambassador to China Tome Pires, during his years in Malacca shortly following conquest will be the primary document used. It, supported by a similar variety of secondary sources will show the changes caused by first conquest and true contact. The examination will look at changes brought by Portuguese faith, trade practices and being a part of the greater Portuguese empire. It will be shown that Malacca was a multi-faith trade sultanate, founded and built around commerce, which projected power and protected itself from larger nations through trade, faith, and political maneuvering. It will be further demonstrated that the changes caused by contact and conquest destroyed the mercantile, imperial identity of the city, and was replaced with a highly autonomous, multi-ethnic and multi-faith identity of many nations built around the emerging concept of the Malay people.

In 1508-1509, a Portuguese expedition was sent to make port in Malacca, with stops farther west throughout the Indian Ocean. The Captain, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, wrote letters with his observations of the expedition, and his general rendition of events. Malacca would fall in 1511, meaning these letters, particularly the part concerning his arrival in the city, are just about the last available description of the free Malacca sultanate as it had been.

Malacca was founded by the last King of the Kingdom of Singapura, after being sacked by larger nations fearing it’s growing power.[i] It was built in a perfect place for trade, as the chosen location was on a major trade route, and it is described that “…the general monsoons die down forty or fifty leagues before the City of Malacca, which is situated half-way along the Straits, but nevertheless the currents and land-winds from both countries suffice for reaching port.”[1] Currents and winds meant Malacca served as a natural stopping point and destination for Indian Ocean, southeast Asian and Chinese traders. The same source, an article by P. E. Josselin De Jong, describes that, “[The] wind and current do always serve them to carry the ships to Malacca.”[2] The Portuguese on arrival describe the geography of the city itself, saying “The town of Malacca is situated almost in the middle of the straits at a latitude of two degrees north. It extends one league along the coast, and has a river which flows from inland and cuts it into two parts…” [3]A major central river flowing from inland allows even more trade to flow, taking goods from the inner peninsula to the city. This geography meant that Malacca was a natural commercial hub built for maritime trade.

With its natural geographic advantages to jumpstart and strengthen it, Malacca built itself as a trading empire. Unlike other regional contemporaries, Malacca was not a decentralised kingdom that took power from its large territory and many cities. Characterized both in contrast to contemporaries and successors by J. Norman Parmer, “The Malacca Sultanate was, however, a city-state with a sea port economy. Political power was centralized, and the Sultan was autocratic” [4] This wealth and central power allowed the city to grab territory for itself, eventually controlling the Malay peninsula including the former site of Singapura. The Portuguese description supports this, by saying that “…the town has an appearance of such majesty by reason of it’s size, the number of ships which are anchored in the harbour, and the extent of the movement of people by sea and by land, that in the opinion of the men of the Portuguese fleet it is greater than what that had heard of it and in it they saw more wealth then there was in India” [5] That massive wealth was supported by a great population of traders from countries all around the greater local region. In addition, the city used the Islamic faith to draw traders and merchants from the entire Islamic commercial sphere. Through this network, it extended its economic reach as far as places like Alexandria. These advantages all served to build a powerful trade empire without the need for the large local population base than was required by its contemporaries.

The national identity of Malacca was not a pre-existing ethnic identity that also applied to the city. Instead, through works produced in the city primarily sponsored by the Sultan, the city created its own national identity, culture, formalized writing and more. There was no one ethnically distinct people within the city, before or after founding. The region surrounding the city was a mix of different peoples, cultures and languages that made up the Malay peninsula. Malacca drew people from many of these groups, from the whole peninsula and beyond into the new city. Combined with the huge mass of foreign traders that resided in the city, as in all similar cities in the region J. M. Guillick described that “…there was a lack of cultural homogeneity in the subject class” [6]. The identity of the city, therefore, had to be formed around other factors. The emergent nation was based on a blend of a great number of differing cultural practices, some local, some Islamic and some imported from other regions. Distinct art, writing and traditions were all started in the city throughout it’s lifespan. Malacca was also strongly centralised, with a great amount of power resting in the city, and a great amount of the cities’ power resting with the Sultan. The Portuguese observed that “Although all the houses are made of wood, with the exception of the mosque and a few buildings belonging to the Sultan…”[7] Central control was strong enough that the only person in the city with actual stone buildings was the Sultan, and his long-time allies of the Islamic faith. This is important because it means the power in the city was concentrated around the rulership instead of with lower nobility, allowing a single identity to emerge from the many groups. Despite the massive wealth of all the traders in the city and the local nobility, only the Sultan had the power for stone construction.[ii] This combination of centralised power, great wealth, no single pre-existing ethnic identity and a unique culture allowed the development of a distinct national identity within the city in a relatively short amount of time.

Religion in Malacca was another important component to the city. While the city was said by both it’s rulers and explorers like the Portuguese to be Muslim, the actual situation was more complex. The local and regional religion at the founding of the city was a syncretic combination of Hinduism, Buddhism and Animism. Malacca was founded as a shift was occurring, and in the words of Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley, “Hindu and Mahayana Buddhist kingdoms that had prevailed in the western parts of the region for more then a millennium were being replaced by polities based … in the archipelago on Islamic doctrines of statehood.” [8] This shift was represented in the religions of the city itself. There was a mix of local faith, Islam, different Buddhist doctrines and Hinduism that were all represented. Conversion in Malacca among the ruling classes to Islam started with the Sultan. This was partly an economic choice to welcome Islamic trade to the city. This meant that Islamic traders, missionaries and scholars were naturally linked to the Sultan. The nobility followed, but “To speak of conversion is perhaps to imply too much. For a considerable part of the Malay nobility this was more a matter of reconciling themselves with the inevitable” describes C.H. Wake [9]. Islam had been spreading in the region for a great many years, and the city embraced it for its offered economic benefits foremost. This adoption of faith, however, did not imply that the lower classes within the city converted. Many of the locals continued to worship as they had since the founding of the city. This meant that Malacca for much of its existence had to deal with being a multi-faith polity. The mix in the city was compounded by the fact that no great efforts from any of the Sultans was made towards conversion. The attitude towards faith that would come to characterize the city allowed a great number of religions to be present and trading, if sometimes taxed at a higher rate under the Islamic jizya taxes. Lopes remarked on that attitude when they came to the city, (unknowingly) noting both Sunni and Shia traders from the Arab world, as well as “…Bengalis, Penguans, Siamese, Chinese, Luzons, Lui-Kius and others who frequented Malacca for trade.” [10] Just about every faith in the monsoon region of Asia at the time could be found in some form in the city, and this helped build the city it’s great riches.

Malacca, despite it’s great wealth and variety of trade partners, was a city under threat. While the city did fight both land and naval wars against it’s more powerful large neighbors, more often than not the survival of the city was built on politics. At different times, the city acted as a tributary of both Ming China, and Ayutthaya in Siam, and on more than one occasion, both at the same time. It played politics for alliances with local Muslim kingdoms as far away as Bengal. Locally, it was alternatively hostile and cooperative with nearby nations in a constant shift of policy, though rarely having to go to war. Because of this, alliances were not long term arrangements with shifts every few years. This policy allowed the city a degree on constant growth. The downside of this policy is that it left Malacca with few long-term friends for when larger nations began to eye the city. Throughout southeast Asia, Malacca looked to project and extend its soft power. Interestingly, it managed to project this power throughout the region with a very small military. As it’s described by M.J Pintado, “Malacca was too insignificant a city to have a navy to antagonize enemies even as Sri Vijaya had antagonized the Chulas and Majaphit. Yet imperialism on a small scale had payed off well.” [11] The city used politics, trade and faith as weapons for influence over the region. While willing to submit in the short term, Malacca would look to benefit from more powerful nations, such as the hegemony of early Ming China, and then throw them off as it suited them. Muslim missionaries proved to be little threat to stability for the city itself, and in fact proved to be some of the Sultans strongest supporters within the city. After conversion, Malacca used them as a weapon against other local kingdoms and to build alliances farther east. Projecting power into even the spice isles, Pintado describes that “Muslim missionaries sailing from its harbour hastened the decay of Majapahit and carried Islam and trade as far as Banda and the Moluccas.” [12] The Malaccan soft power doctrine was used in almost all cases, including against it’s largest enemies. A combination of altering war, antagonization and submission in name to Ayutthaya, while pushing for and helping along the decline of Majaphit were mainstays of Malaccan action. Even the arrival of Portugal, prior to the capture of the city, was not unprecedented to the Sultanate. The Chinese treasure fleets had stopped in the city as well, presenting a distant power projecting might into the city through naval force. Internally the city was drawn between different factions and powers of merchants which played a major part in whom the city favored. This allowed nations to support their traders in the city to gain major influence with the Malaccan government. This approach, however, allowed foreign rivalries to be imposed in the city. At the Portuguese arrival, a conflict is described in the opinion of the city between Arab world traders and non-Arab. “To their discredit those people [Muslim Traders] had frightened the gentiles by telling them about the Portuguese customs and commerce…”[iii] [13]. This extension of other rivalries like the Arab – Portuguese conflict into the city drove several painful conflicts for the city, including its invasion and occupation by the Portuguese a scant two years later.

The Portuguese expedition and its letter about the affair presented the last real look at the city before conquest. Malacca was a state different from its contemporaries for its pure trade economy, it’s slightly odd foreign policy of mostly soft power and its multi-ethnic and multi-religious construction. Rather than being the nation of a distinct ethnic people, Malacca was a city that created its own identity, one that had lasting impact on the region. The Malaccan identity was a trading nation with a multi-faith composition under Islamic governance. These qualities, however, would make it an attractive target for the western nations arriving in the region, and the Portuguese conquered the city less than ten years after their initial arrival. The Portuguese governance, it’s greater empire which Malacca was now a part of, and the echo of the true arrival of European empire would leave deep changes in the city itself.

Tome Pires was a Portuguese apothecary who arrived in Asia in 1511. Through his competence and his merits (and the nature of the Portuguese in Asia at the time), he became the first Portuguese Ambassador to China. Before that appointment, however, he spent two and a half years (through the year 1513 is the main date we have), in Malacca. During his say studying primarily Asian drugs, he wrote a major history text about the region known as the Suma Oriental. The second section of this text concerns Malacca after the Portuguese conquest. By its nature as a contemporary history text, it provides a window into the thoughts of the Portuguese about the city and region.

"Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice"[14], wrote Tome Pires. The trade of Malacca, especially to the Portuguese, represented more than just absurd profits at low risk[iv]; it represented control of trade through Europe. The Portuguese believed that control of the trade flow of Asia through their conquest of Malacca would allow them to strangle trade in the Arab world. This strangling, to the Portuguese, had the twofold advantage of damaging trade for their enemies, Venice and the Muslim sultanates. The Portuguese, looking to put in place the start of a mercantile system, imposed a tax of 20 percent on goods in Malacca[15] which rising power Johor, a rival state to Malacca, did not impose. With the absurd profits earned by trade ventures, the new tax affected but did not destroy trade. It did, however, deeply damage its mercantile identity. No longer a city of free traders under a hegemony, Malaccan identity was became far more reliant on the writing, art, and other cultural artifacts developed under the Sultanate. As Johor became the city of the many Malay villages and began to develop as Malay, the identity of Malacca remained mixed. The Portuguese observed this, and noted the lack of ethnic unity in the city, especially during war. Pires records "...the natives did not back the king of Malacca; because in, trading-lands, where the people are of different nations, these cannot love their king as do natives without admixture of other nations."[16] The Portuguese assumed that mixed loyalties were a natural part of a trading city, and that they could rule the city like the Sultan had, as outsiders. The near existential problem for Southeast Asian trade the Portuguese created was not just high tariffs in a single city. M. C. Ricklefs, an Indonesian historian writes “[The Portuguese] had fundamentally disrupted the organisation of the Asian trade system.”[17] This disruption was caused by the destruction of hegemony in the region, which had secured diverse trade into a single port. Ricklefs expands “There was no longer a central port where the wealth of Asia could be exchanged; there was no longer a Malay state to police the Straits of Malacca and make them safe for commercial traffic. Instead, there was a dispersal of the trading community to several ports, and bitter warfare in the Straits." Bitter warfare often manifested as state-sponsored pirate attacks among the powers of the region, but in no way precluded military action. This collapse in centralised trade in Southeast Asia was compounded by the Portuguese insistence on pirating Arab vessels, primarily in the Indian Ocean, and a state of near constant hostilities between the Portuguese and Aceh within the straits. This warfare meant that no nation, despite ambitions, would be the ‘heir of Malacca’. The conditions that had allowed the Sultanate to thrive, the traditional organisation of trade in Southeast Asia, had been lost.

Faith was a core component of the Portuguese conflicts and strategy within Asia. The Portuguese strongly believed in their own religious and cultural superiority over the native Muslim rulers. The Portuguese viewed that Islam in the region was doomed to fail and that as Christians they were inherently better rulers. "And since it is known how profitable Malacca is in temporal affairs, how much the more is it in spiritual [affairs], as Mohammed is cornered and cannot go farther, and flees as much as he can.”[18] Pires wrote, not long after the conquest of Malacca. The Portuguese failed to understand the vital role of Muslim merchants as a trading go-between from Alexandria to China. The Catholic Portuguese would also never bow to the power of the Dynasties of China as the previous ruler of the city had, seeing them as heretics. Despite this, the Portuguese were confident that there would be no true long-term disruption. Pire continued “… let people favour one side, while merchandise favours our faith; and the truth is that Mohammed will be destroyed, and destroyed he cannot help but be."[19] To them, the failure of the Muslim order in Asia, and the ascendance of Portuguese Malacca as the foremost trading port in the world was just a matter of time. "Malacca cannot help but return to what it was, and [become] even more prosperous, because it will have our merchandise; and they are much better pleased to trade with us than with the Malays, because we show them greater truth and justice."[20] Pires, and the Portuguese themselves saw Portugal as the preeminent global trade power and inherently better trade partners for their faith.

What the Portuguese failed to realise is that, despite its spectacular natural geography, Malacca was not at all the inevitable ruler of the region. Soon, competition from Johor and Aceh was fighting the Portuguese for southeast Asian trade. On the rise of Aceh, one of its new rivals, Ingrid S. Mitrasing, a Malaysian historian writes "The relocation of Muslim trade networks from the conquered port of Malacca to Sumatra's eastern ports was the impetus for Aceh's economic rise, laying the foundations for its becoming one of Asia's greatest maritime powers of that time."[21] Malacca lost a major component of its trade and prominence as Aceh took over as the Muslim trade center of southeast Asia. Within Malacca itself, the institution of Portuguese Christianity failed to gain prominence the way Islam had, and the concept of Islam as a centralising force within the city was simply lost instead of being replaced. Christianity even outside the city itself only gained any prominence later in Portuguese rule, and more as the work of several dedicated holy men than any true Portuguese effort. The Portuguese failed to seek and maintain the ties of faith and trade that the Malacca Sultanate had with used to build its power base. For Malacca, the nature of Islam as a symbol of status and connection beyond the city faded, with Islam simply becoming another part in the multi-faith city.

The Portuguese administration in Asia had deep-rooted problems from its very start. Optimistic about the state of their empire, Pires identifies flaws already present in the Portuguese system, but proposed solutions. He writes "Great affairs cannot be managed with few people. Malacca should be well supplied with people, sending some and bringing back others. It should be provided with excellent officials, expert traders, lovers of peace, ...for Malacca has no white-haired official."[22] The aid and administrative competence, sorely needed, never materialised in the city. Portuguese administration in the region was instead moved to Goa, on the west side of India, and Malacca seemed almost an afterthought to officials in Portugal. Resources from the homeland were few, especially capable men and leaders. Armando Cortesao, historian, remarks that "Castanheda[v] informs us that ‘the King of Portugal did not send any ambassador [from Portugal], because, thinking that the King of China was near, he ordered Femao Peres to send there one of his captains, or whoever he might choose....'[23] This failure to supply the Asian empire from the homeland represented a pattern of a lack of resources provided to the Portuguese administration in the region. In 1581, when the crown of Portugal was combined into the Iberian Union, the resources provided were lessened even more. The administration of the Portuguese Asian territories became a study in making do. The lone Christian power in the region, starved for resources and surrounded by hostile nations[vi], Malacca was forced to act as an autonomous entity to preserve its own interests, rather than those of the Portuguese empire. Internal rebellions[vii], and a vanishing technological advantage[24] provided more problems to the Portuguese, but two main factors allowed them to rule the city for 130 years despite their many problems.

Seamanship and geopolitics were the tools of survival for Portuguese Malacca. "...it is difficult to conceptualize the region before this century, because the boundaries of many states kept shifting and because many of the actors, ... were operating in areas beyond the borders of today's Republic"[25] Dennis Duncanson, historian, remarks. The period of Portuguese Malacca existed in a time and place where states and nations in constant flux and conflict. International relations and realpolitik dominated the region, with powers like Johor sometimes fighting and sometimes helping the Portuguese (and in one notable case, saving the Portuguese from a Chinese fleet). “Inter-state relations were at all times an important ingredient of political activity in Southeast Asia”[26] records S. Arasaratnam, a historian of Southeast Asia. The Portuguese empire in Malacca and other Asian possessions was highly autonomous and ruled by a local Bendahara who functionally ran much of the city and surrounding communities. International relations, in theory to be administered by the king in Portugal or Spain, were far to volatile and active to be run from a distance that took a full year for a round trip. The colonial government, on the far side of India, was often still too far away to run the city. Corruption[viii], confused commands and decisions made with strained resources were mainstays in the Portuguese administration; luckily much of the city ran itself. This culture of autonomy became a powerful part of Malaccan identity. Portuguese married into local families, and much of the colonial government was run by mixed children of locals and Portuguese for lack of lack local manpower. This mixed nature extended into trade, where “ships were seen in the Indonesian archipelago which had part Portuguese and part Indonesian crews, or which were owned by Indonesians and chartered by Portuguese.”[27] Malacca under the Portuguese, like the Sultanate before it, remained reliant on food sources external to itself and was forced to procure food for locals. The Portuguese Asian empire, starved for money and manpower, was reliant on this mixed society. To even call Malacca under the Portuguese ‘Portuguese in nature’ is a mistake. The city-state of Malacca simply accepted both Portuguese and mixed Portuguese as new nations within the wider city, and they had notably Malaccan flavor as a society.[28] The shifting nature of local politics, the able Portuguese and Portuguese/Malaccan naval power and the natural geographic advantages of the empire allowed it to survive long past what would be expected considering its resources and administration.

Conquest, not first contact, was the change that redefined Malacca. In the wake of the conquest, the city that was once the Sultanate of Malacca declined sharply in importance and was never again the kind of power it was after its founding. In the wake of conquest, Malacca lost its nature as a centralised, hyper mercantile nation who ruled the seas. Its identity as a multi-religious, multi-ethnic nation of autonomous peoples who shared a Malay culture was partly strengthened partly formed in the long wake of the capture.

[1] P.E De Josslin De Jong and H. L. A. Van Wijk, “The Malacca Sultanate”, Journal of Southeast Asian History, Vol. 1 No. 2 (Sep., 1960): 22.

[2] Ibid

[3] Manuel Murias, “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira” in Portuguese Documents on Malacca Vol. I, 1509 - 1511, Edited and Translated by M.J Pintado, (Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993), 43.

[4] J. Norman Parmer, review of Indigenous Political Systems of Western Malaya, by J. M. Guillick, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol 19, No. 1 (Nov., 1959): 91.

[5] Murias, “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira”, 43.

[6] J. M. Guillick, Indigenous Political Systems of Western Malaya: Revised Edition (London and Atlantic Highlands, NJ.: The Athlone Press, 1988), 44.

[7] Murias, “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira”, 43.

[8] Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley “The Historical Context,” in Melaka: the transformation of a Malay capital c. 1400-1980 Volume One, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley (Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1983), 3.

[9] C.H. Wake “Melaka in the Fifteenth century: Malay Historical Traditions and the Politics of Islamization in Melaka: the transformation of a Malay capital c. 1400-1980 Volume One, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley (Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1983), 140.

[10] Murias, “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira”, 43.

[11] M.J Pintado, Introduction to Portuguese Documents on Malacca Vol. I 1509 - 1511, Edited and Translated by M.J Pintado, (Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993), 4.

[12] Pintado, Introduction to Portuguese Documents on Malacca Vol. I 1509 – 1511, 5.

[13] Murias, “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira”, 43.

[14] Tome Pires and Francisco Rodriges, The Suma Oriental: an Account of the East, from the Red Sea to China Vol II (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944), Edited and Translated by Armando Cortesao, accessed March 2 2017, http://www.sabrizain.org/malaya/library/, 287.

[15] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 284.

[16] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 286.

[17] M. C. Ricklefs, A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200 Third Edition, (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001), 27.

[18] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 286.

[19] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 286.

[20] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 283.

[21] Ingrid s. Mitrasing, "Negotiating a New Order in the Straits of Malacca (1500–1700)," KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 21, No. 2, (2014): 56.

[22] (Pires and Rodrigues 1944), 285.

[23] Armando Cortesao , Introduction to The Suma Oriental: an Account of the East, from the Red Sea to China Vol I, by Tome Pires and Francisco Rodriges (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944), xxvii.

[24] (M. C. Ricklefs 2001), 27.

[25] Dennis Duncanson, review of Melaka: The Transformation Of A Malay Capital C. 1400-1980 By Kernial Singh Sandhu; Paul Wheatley, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland No. 1 (1985): 121

[26] S. Arasaratnam, Intoduction, in International Trade and Politics in Southeast Asia 1500-1800 ed. S. Arasaratnam (Singapore, Cambridge University Press, 1969), 391

[27] (M. C. Ricklefs 2001), 28.

[28] Ingrid s. Mitrasing, "Negotiating a New Order in the Straits of Malacca (1500–1700)," KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 21, No. 2, (2014): 61

[i] It’s recorded that the nations of Ayutthaya and Majaphit destroyed Singapura, and thusly the successor state of Malacca had those two states as it’s foremost enemies.

[ii] Stone buildings provide a level of safety and permeance over wooden buildings, but more then that were a function of status. Both stone and (probably Islamic) architects would have had to be imported to the city to build the structures at great expense, as all local construction was with wood.

[iii] While the Portuguese were rather convinced it was the Muslim traders that disliked them, this is not quite true. Gentiles, who are presented as the neutral traders, is used to refer to non-Christian and non-Muslim peoples of the region. The Portuguese consider the Muslim kingdom of Bengal, among others, to be gentiles. However, another Indian Muslim kingdom Gujarat and the Shia Persians are listed in the same general group of Muslims. The Portuguese, as one might expect from such a short time in the region, make numerous mistakes like this (or simply apply the name Muslim to nations they do not like.)

[iv] Profits varied by expedition destination, but for ever 100 ‘dollars’ put in the expedition would return between 140 for a short, pretty local voyage to 300 or more from a Chinese venture

[v] This being Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, a Portuguese historian from the mid 1500s, though no further information is provided by the source.

[vi] While Islam was a traditional enemy from the first Portuguese arrival, China became very hostile to the Portuguese later in their reign, and fought against them, both moving their main trade to Johor and launching an attempted invasion of Malacca.

[vii] The Malaccans did not simply accept Portuguese rule, with several coup attempts and more then one rebellion in the first few years of rule.

[viii] It’s noted that Malaccan leadership often traded in Johor for personal benefit, to get around the Portuguese tariffs, going against the monopoly the Portuguese were attempting to create.

Bibliography

Arasaratnam, S. “Intoduction”, in International Trade and Politics in Southeast Asia 1500-1800. ed. S. Arasaratnam, 391-395. Singapore, Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Cortesao, Armando. Introduction to The Suma Oriental: an Account of the East, from the Red Sea to China Vol I, by Tome Pires and Francisco Rodriges. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1944.

De Jong, P.E De Josslin and Van Wijk, H. L. A. “The Malacca Sultanate.” Journal of Southeast Asian History, Vol. 1 No. 2 (Sep., 1960): 20-29.

Duncanson, Dennis. Review of Melaka: the transformation of a Malay capital C. 1400-1980 By Kernial Singh Sandhu; Paul Wheatley. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1 (1985): 119-123.

Guillick, J. M. Indigenous Political Systems of Western Malaya: Revised Edition. London and Atlantic Highlands, NJ: The Athlone Press, 1988.

Mitrasing, Ingrid s. "Negotiating a New Order in the Straits of Malacca (1500–1700)," KEMANUSIAAN, Vol. 21 No. 2 (2014): 55-77.

Murias, Manuel. “On the deeds & discoveries & conquests made by the Portuguese in the seas and Eastern Lands – Diogo Lopes de Sequeira” in Portuguese Documents on Malacca Vol. I, 1509 - 1511, Edited and Translated by M.J Pintado, 38-52. Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993.

Parmer, J. Norman. Review of Indigenous Political Systems of Western Malaya, by J. M. Guillick. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol 19, No. 1 (Nov., 1959): 91-92.

Pintado, M.J. Introduction to Portuguese Documents on Malacca Vol. I 1509 - 1511, Edited and Translated by M.J Pintado. Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993.

Pires, Tome, and Francisco Rodrigues. 1944. The Suma Oriental: an Account of the East, from the Red Sea to China Vol II. Edited and Translated by Armando Cortesao. London: The Hakluyt Society. Accessed March 2, 2017. http://www.sabrizain.org/malaya/library/.

Ricklefs, M. C. A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200 Third Edition. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

Sandhu, Kernial Singh and Wheatley, Paul. “The Historical Context,” in Melaka: the transformation of a Malay capital c. 1400-1980 Volume One, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley, 3-69. Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1983.

Wake, C.H. “Melaka in the Fifteenth century: Malay Historical Traditions and the Politics of Islamization in Melaka: the transformation of a Malay capital c. 1400-1980 Volume One, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley, 128-161. Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1983.

1 note

·

View note