#i also drew this two weeks into exhibition install at work and in the middle of securing a lease on a new apartment so take from that what

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

those two vigilantes ruining your local pub are actually a wannabe businessman and his father's very capable butler!

#yonderland#six idiots#chris payne#the bird and the bee#yonderland fanart#debbie maddox#martha howe douglas#jim howick#mat baynton#mathew baynton#i tried watching yonderland and the amount of puppetry going on was a bit much for me but i applaud their creativity!#i also drew this two weeks into exhibition install at work and in the middle of securing a lease on a new apartment so take from that what#you will#the gesture studies from the bird in the pub were so fun to draw tho and great practice#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#csp#clip studio paint#illustration

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief History of Photography: The Beginning

Photography. An art form invented in 1830s, becoming publicly recognised ten years later.

Today, photography is the largest growing hobby in the world, with the hardware alone creating a multi-billion dollar industry. Not everyone knows what camera obscura or even shutter speed is, nor have many heard of Henri Cartier-Bresson or even Annie Leibovitz.

In this article, we take a step back and take a look at how this fascinating technique was created and developed.

Before Photography: Camera Obscura

Before photography was created, people had figured out the basic principles of lenses and the camera. They could project the image on the wall or piece of paper, however no printing was possible at the time: recording light turned out to be a lot harder than projecting it. The instrument that people used for processing pictures was called the Camera Obscura (which is Latin for the dark room) and it was around for a few centuries before photography came along.

It is believed that Camera Obscura was invented around 13-14th centuries, however there is a manuscript by an Arabian scholar Hassan ibn Hassan dated 10th century that describes the principles on which camera obscura works and on which analogue photography is based today.

Camera Obscura is essentially a dark, closed space in the shape of a box with a hole on one side of it. The hole has to be small enough in proportion to the box to make the camera obscura work properly. Light coming in through a tiny hole transforms and creates an image on the surface that it meets, like the wall of the box. The image is flipped and upside down, however, which is why modern analogue cameras have made use of mirrors.

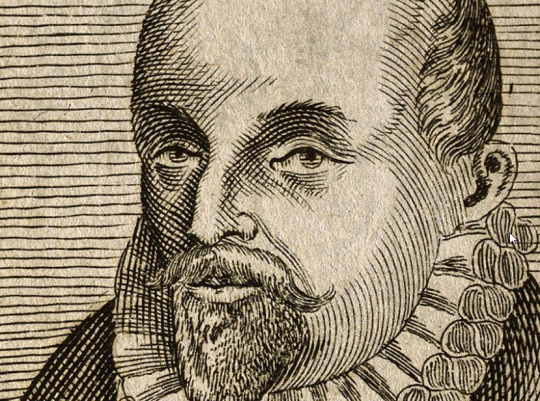

In the mid 16th century, Giovanni Battista della Porta, an Italian scholar, wrote an essay on how to use camera obscura to make the drawing process easier. He projected the image of people outside the camera obscura on the canvas inside of it (camera obscura was a rather big room in this case) and then drew over the image or tried to copy it.

The process of using camera obscura looked very strange and frightening for the people at those times. Giovanni Battista had to drop the idea after he was arrested and prosecuted on a charge of sorcery.

Even though only few of the Renaissance artists admitted they used camera obscura as an aid in drawing, it is believed most of them did. The reason for not openly admitting it was the fear of being charged of association with occultism or simply not wanting to admit something many artists called cheating.

Today we can state that camera obscura was a prototype of the modern photo camera. Many people still find it amusing and use it for artistic reasons or simply for fun.

The First Photograph

Installing film and permanently capturing an image was a logical progression.

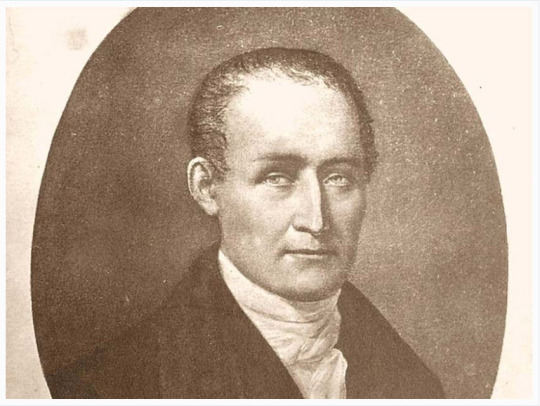

The first photo picture—as we know it—was taken in 1825 by a French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. It records a view from the window at Le Gras.

The exposure had to last for eight hours, so the sun in the picture had time to move from east to west appearing to shine on both sides of the building in the picture.

Niepce came up with the idea of using a petroleum derivative called "Bitumen of Judea" to record the camera's projection. Bitumen hardens with exposure to light, and the unhardened material could then be washed away. The metal plate, which was used by Niepce, was then polished, rendering a negative image that could be coated with ink to produce a print. One of the problems with this method was that the metal plate was heavy, expensive to produce, and took a lot of time to polish.

Photography Takes Off

In 1839, Sir John Herschel came up with a way of making the first glass negative. The same year he coined the term photography, deriving from the Greek "fos" meaning light and "grafo"—to write. Even though the process became easier and the result was better, it was still a long time until photography was publicly recognized.

At first, photography was either used as an aid in the work of an painter or followed the same principles the painters followed. The first publicly recognized portraits were usually portraits of one person, or family portraits. Finally, after decades of refinements and improvements, the mass use of cameras began in earnest with Eastman's Kodak's simple-but-relatively-reliable cameras. Kodak's camera went on to the market in 1888 with the slogan "You press the button, we do the rest".

In 1900 the Kodak Brownie was introduced, becoming the first commercial camera in the market available for middle-class buyers. The camera only took black and white shots, but still was very popular due to its efficiency and ease of use.

Color Photography

Color photography was explored throughout the 19th century, but didn't become truly commercially viable until the middle of the 20th century. Prior to this, color could not preserved for long; the images quickly degraded. Several methods of color photography were patented from 1862 by two French inventors: Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charlec Cros, working independently.

The first practical color plate reached the market in 1907. The method it used was based on a screen of filters. The screen let filtered red, green and/or blue light through and then developed to a negative, later reversed to a positive. Applying the same screen later on in the process of the print resulted in a color photo that would be preserved. The technology, even though slightly altered, is the one that is still used in the processing. Red, green and blue are the primary colors for television and computer screens, hence the RGB modes in numerous imaging applications.

The first color photo, an image of a tartan ribbon (above), was taken in 1861 by the famous Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who was famous for his work with electromagnetism. Despite the great influence his photograph had on the photo industry, Maxwell is rarely remembered for this as his inventions in the field of physics simply overshadowed this accomplishment.

The First Photograph With People

The first ever picture to have a human in it was Boulevard du Temple by Louis Daguerre, taken in 1838. The exposure lasted for about 10 minutes at the time, so it was barely possible for the camera to capture a person on the busy street, however it did capture a man who had his shoes polished for long enough to appear in the photo.

Notables in Photography

At one time, photography was an unusual and perhaps even controversial practice. If not for the enthusiasts who persevered and indeed, pioneered, many techniques, we might not have the photographic styles, artists, and practitioners we have today. Here are just a few of the most influential people we can thank for many of the advances in photography.

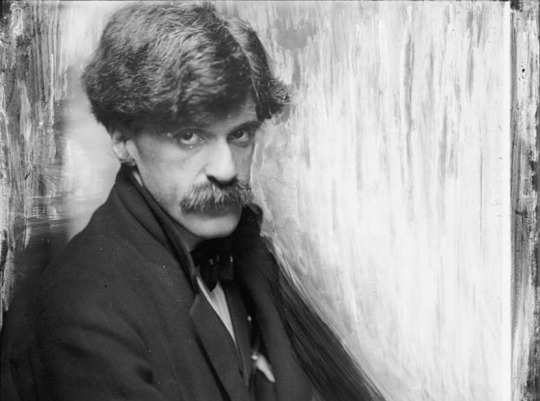

Alfred Stieglitz

Photography became a part of day-to-day life and an art movement. One of the people behind photography as art was Alfred Stieglitz, an American photographer and a promoter of modern art.

Stieglitz said that photographers are artists. He, along with F. Holland Day, led the Photo-Secession, the first photography art movement whose primary task was to show that photography was not only about the subject of the picture but also the manipulation by the photographer that led to the subject being portrayed.

Stieglitz set up various exhibitions where photos were judged by photographers. Stieglitz also promoted photography through newly established journals such "Camera Notes" and "Camera Work".

Example of Stieglitz's Work

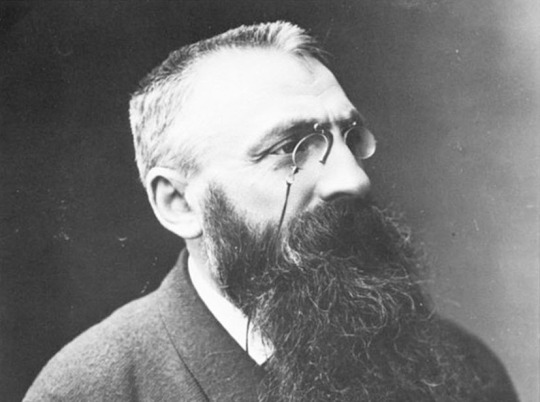

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (Felix Nadar)

Felix Nadar (a pseudonym of Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) was a French caricaturist, journalist and—once photography emerged—a photographer. He is most famous for pioneering the use of artificial lightning in photography. Nadar was a good friend of Jules Verne and is said to have inspired Five Weeks in a Balloon after creating a 60 metre high balloon named Le Géant (The Giant). Nadar was credited for having published the first ever photo interview in 1886.

Nadar's portraits followed the same principles of a fine art portrait. He was known for depicting many famous people including Jules Verne, Alexander Dumas, Peter Kropotkin and George Sand.

Example of Nadar's Work

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a French photographer who is most famous for creating the "street photography" style of photojournalism, using the new compact 35mm format (which we still use today). Around the age of 23, he became very interested in photography and abandoned painting for it. "I suddenly understood that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant," he would later explain. Strangely enough, he would take his first pictures all around the world but avoided his native France. His first exhibition took place in New York's Julien Levy Gallery in 1932. Cartier-Bresson's first journalistic photos were taken at the George VI coronation in London however none of those portrayed the King himself.

The Frenchman's works have influenced generations of photo artists and journalists around the world. Despite being narrative in style, his works can also be seen as iconic artworks. Despite all the fame and impact, there are very few pictures of the man. He hated being photographed, as he was embarrassed of his fame.

Example of Cartier-Bresson's Work

Check This Link To Know More About Photography : https://bit.ly/39Rpdsc

#studio serra photography#photo studio san diego#photography studio san diego#commercial real estate photography#commercial photography service#landscape photography#fine art photography#seascape photography#beachscape photography#scenic photography

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

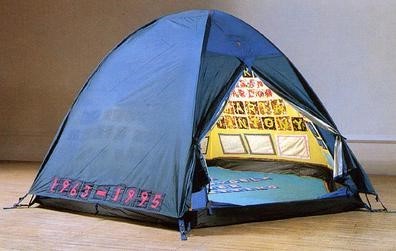

TRACEY EMIN

Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With (1995)

https://bilderfahrzeuge.hypotheses.org/3437

Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995)

https://www.artforum.com/video/tracey-emin-why-i-never-became-a-dancer-1995-49262

Tracey Emin, My Bed, (1999)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Bed

Tracey Emin, I've Got It All (2000)

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/emin-tracey/artworks/#pnt_4

Tracey Emin, To Meet My Past (2002)

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5709375

Childhood

Tracey Emin was born in Surrey, in England. She grew up in Margate, on the coast of Kent, with her twin brother Paul. She lived with her mother in a successful seaside hotel, where she claims she was treated "like a princess." Her Turkish father lived with them for half of the week, spending the other half with his wife and other children. After a few years, Emin's father left and took his money with him, leaving Emin's mother bankrupt.

The family was then forced to live in poverty; Emin later recalled that they had two meters, one for gas and one for electricity, but they could never afford to have them both on at the same time. When she was 13, Emin was raped; something that she later claimed, "happened to a lot of girls."

Early Training and Work

Emin left Margate to study fashion at the Medway College of Design between 1980 and 1982. She met the avant-garde personality Billy Childish, who was also a student at the college until he was expelled. Her relationship with the colourful writer, their work at Childish's small press, and her study of printing in Maidstone Art College, are all what Emin considers important artistic experiences in her maturing as an artist.

In 1987, Emin's relationship with Childish ended and she moved to London. She studied for an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art, which she received in 1989. However, after leaving the college she went through an emotionally traumatic period in which she had two abortions, and this experience caused her to destroy all the work she had made at the Royal College.

While she was still coming to terms with her own artistic practice, she influenced a reactive movement called Stuckism, which sought to promote figurative painting rather than the sort of conceptual art that Emin was focused on at the time. It was founded in 1999 by Emin's ex-boyfriend Billy Childish. The movement's name was inspired by Emin, when she had told Childish his paintings were "Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!"

In the years after breaking up with Childish, once Emin rose into fame, he became very vocal about Emin's art practice. He opposed the art business and in turn the popularity of her work and said, "Taking cultural things and turning them into mere commerce is very dangerous. Professional football has ruined football and professional art has ruined art. A decadence and superficiality have set in and sometimes I wonder if maybe we have got what we deserve. I think it is odd that the Brit artists cite the influence of someone like Duchamp who was involved in anti-art and who was taking the piss out of the pompous pretentious art establishment. The biggest irony is that now they are that pretentious art establishment themselves, yet they still put forward this idea that they are undermining something." Childish's own Stuckism movement is more about rejecting the frenzy of conceptual art and sought to champion the work of figurative painters. The Stuckism movement is still quite active and is famous for protesting the Turner Prize every year to show their continued opposition. The Stuckism art movement is an action against artists such as Emin, and yet her artistic presence is the basis for their fundamentals, for their movement would not exist without Emin. She inspired the movement not only through her criticism of Childish's work, but also through her artwork and the public acceptance of her work. They may be in opposition to her but require her brand of art fame to continue their plight.

Mature Period

Upon moving to London, Emin become friendly with many of the other artists who would later be called the Young British Artists, which included Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst. The group began to exhibit together in 1988, although Emin did not join ranks with them artistically until the early 1990s. The gallerist Charles Saatchi was a supporter and collector of the artists from the beginning of their careers and is often given credit for "discovering" them. The name of the group was from the title of an exhibition at Saatchi's gallery in March 1992 titled "Young British Artists I" but it was artist and writer Michael Corris who referred to the group of artists with that title in an ArtForum article in May 1992. Often all artists of that generation from Britain are called YBAs as it now holds a historic reference.

In 1993, Emin joined with Sarah Lucas to open a shop called "The Shop" in Bethnal Green, which was in the East End of London. They sold work by both artists, including anything from t-shirts to ash trays, to paper mache sex toys to dresses, adding a previously little-seen commercialism to their artistic practices, which would become a defining feature of Young British Art.

Emin had her first solo exhibition at London's White Cube in the same year. Named My Major Retrospective, Emin drew together a collection of personal items and photographs, creating a part-installation part-archive with a strongly autobiographical slant. This element of autobiography is key to her ongoing practice.

In the middle of the 1990s, Emin began a relationship with curator and art world figure Carl Freedman. Freedman was friendly with Damien Hirst and had worked with him on some of his important early shows that introduced Young British Art to the public. In 1994 the couple travelled in the US together, where Emin paid her way by doing readings. They also spent time in Whitstable on the Kent coast together, often using a beach hut that Emin purchased with her friend Sarah Lucas. She has spoken about how much she enjoyed owning property for the first time saying, "I was completely broke, and it was really brilliant, having your own property by the sea." In 1999 she later turned the hut into an artwork by bringing the structure from the beachfront into the Saatchi Gallery and calling the work, The Last Thing I Said to You is Don't Leave Me Here (1999).

In 1995, Freedman curated a show called "Minky Manky" for which he encouraged Emin to make artwork larger and less ephemeral. The result was her well-known work Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 (1995), which was a tent embroidered with the names of everyone with whom she had shared a bed, sexual or otherwise. This artistic touch through words is a common theme throughout her work. Emin uses her own handwriting, as seen in her neon messages, embroidered words, monoprints and hand-cut letters for her applique designs. Misspellings and grammar mistakes are present in her artworks, as if to add humiliations and failures to her authenticity.

Emin first came to the attention of the wider British public when she appeared on a television show about the Turner Prize in 1997, where she was belligerent and drunk, swearing on live television among a panel of academics. She finished her appearance by saying, "I'm leaving now, I wanna be with my friends, I wanna be with my mum. I'm gonna phone her, and she's going to be embarrassed about this conversation, this is live, and I don't care. I don't give a fuck about it." She ended with, "you people aren't relating to me now, you've lost me" before taking off her lapel mic while still talking and walking off in the middle of the live show.

Two years after her drunken television appearance, Emin was nominated for the Turner Prize for her controversial work My Bed (1998). Only one British artist of the four nominated can win the prize, and Emin lost the Prize that year to Steve McQueen. The surrounding press coverage dubbed her the "bad girl of British art". At the time, many voiced opinions about the types of stains and impurities contained in her artwork, even the lowest English tabloids weighed in. Although she never won the Turner Prize (yet), it was the catalyst for her fame.

Her work evolved during this period and she developed a more specific style. Her choice to use needlework and applique techniques place her work within a tradition of feminist discourse within modern and contemporary art. These techniques were considered domestic handicrafts and were typically considered low in the hierarchy of art, and a part of normalized feminine practice - a concept that Feminist art has waged war against with significant success. Emin herself has no fear of being associated with "low art" or "women's work", for she embraces her own sexuality and femininity; and most certainly places importance upon it.

Current Practice

Emin's personal life and public appearances have become less sensational since the late 1990s. Her work is in a variety of important collections, and many celebrities have become collectors of her art, including Elton John and George Michael. She has also become friends with many famous people from the music and fashion worlds, including Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, Vivian Westwood, Kate Moss, and Madonna. Madonna has described Emin as "intelligent and wounded and not afraid to expose herself."

In 2007, Emin was made a Royal Academician at London's Royal Academy of the Arts, marking her ascent into the upper echelons of British art society and her acceptance by the establishment. She was later also made a professor of drawing at the institution. In 2013, she was included on a list of the 100 most powerful women in the country by BBC Radio 4, and in the same year she was awarded a CBE for her services to the arts.

For the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007 Emin was the second female British artist to be nominated to represent the British Pavilion (the first was Rachel Whiteread in 1997). She exhibited a work titled, Borrowed Light which featured many of her early drawings alongside her recent works. The show received mixed critique, and she was criticized for being limited in her art practice.

In 2015, Emin took the unusual decision to "get married" to a rock in her garden in France. She later stated that "somewhere on a hill facing the sea, there is a very beautiful ancient stone, and it's not going anywhere," describing her rock-husband as "an anchor, something I can identify with." She symbolically chose to wear her father's funeral shroud for the short and unconventional ceremony. This is to be understood as a universal expression of love, and an expression of the soul or the invisible self. Emin has announced numerous times that she no longer has sex and is not invested in physical conquest, but rather, seeks to focus on love and her work.

The Legacy of Tracey Emin

Emin's work as part of the Young British Artists movement placed her firmly within a key legacy that was to affect the development of art in Britain for years to come. Similarly, she holds an international stage, for her work tackles universal ideas through her relationship to human behaviour and gender. Her seminal work My Bed helped redefine what a liberated woman can be. Emin’s work influenced a generation of female artists who explore womanhood and feminism through a self-confessional tone. These include artists such as Marie Jacotey-Voyatzis, whose print works explore her emotional life as a woman and include Emin-like misspellings, and Laure Prouvost, a Turner Prize winner who works with self-revelatory video as well as textiles and found objects to create striking tableaux. Emin has evaded aligning her ideology with a larger political cause, and has stated, "I'm not happy being a feminist. It should all be over by now."

Her work can be understood as belonging to the ethos of third-wave feminism; a belief that a woman can define her sexuality on her own terms. The lack of symbology in Emin's work forces audiences to focus on the real and often taboo aspects of femininity through modern women's issues, such as menstruation, abortion, promiscuity, and the shame associated with these topics. She has carved her own place and continues to produce artwork with her signature strong, yet vulnerable edge.

Emin continues to be active in her art practice, and the basis of her work remains tied to physical identity through corporeal and spiritual anguish. She is an active participant in her artwork, and through this she lends an openness and vulnerability to her audience through universal emotion. She rejects discussion of the feminist authority in her work, and yet she engages directly with modern female identity. Art allows the violation of social norms, and in turn a way for viewers to enter sharing the human social condition - often in a controlled environment.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In which Shirayuki met Obi's assistant

A part of the Flatmate AU

“I’m going to install the cabinet today,” Obi suddenly said as he arranged their used plates and mugs into the dishwasher.

“It’s about time we do it – the empty space is slowly getting on my nerves.” Shirayuki placed the half loaf of bread back into the bread box and glanced at the clock. It was already a little after ten. “But then you’ll need to hurry. You only have three hours until the quiet hours. Or do you plan to do it in the afternoon?”

She heard Obi snort and she rolled her eyes. Quiet hours. It was one of those typical things in this country which took Obi a while to get used to. She could understand why, though. Surely there are people who want to take an undisturbed nap after lunch on a Sunday, but sometimes it limits other people’s time to do things in their homes, like playing music, or installing kitchen cabinets. Especially when they only have Sunday to do these stuff.

“Nah, I’ll do it in a bit. Won’t take that long. Besides, I’ll have an assistant,” Obi said, smirking.

Shirayuki frowned. This was unlike Obi. Usually he would have told her days before if he needed her help. “I can’t be your assistant, Obi. I’ve already promised Yuzuri to accompany her to this coffee exhibition, remember? Unless you could wait until I’m back? I can’t tell you for sure when I’ll be back, though...”

Obi chuckled, “Of course I remember, sweetie. Don’t worry, it’s–”

Just then the building’s doorbell rang. Obi grinned at Shirayuki. “I’ll get it. That should be my assistant.”

Shirayuki watched as Obi slammed the dishwasher’s door closed and trotted to the front door. He pressed the buzzer to let the person in and waited until they arrived at their floor. Who could that be, Shirayuki wondered. Obi rarely talked about his friends, other than Suzu. And even then, it was always in a work context. She wondered whether they were even friends outside of work. Creeping to the corridor Shirayuki hid herself behind the wall and peeked around the corner, just as the door opened.

“Right on time, Aki-chan!”

“Hi, Obi.”

Shirayuki’s eyes widened. The assistant was a big guy, half a head taller than Obi, muscular and proud of it, judging from the tight tee he was wearing. A second later he was pulling Obi into a tight embrace, his platinum blonde hair a stark contrast to Obi’s dark one. His face was beautifully carved, with a high nose bridge and thick, hard angled eyebrows. His eyes were closed and a huge smile was on his lips, showing a row of pearly white teeth.

Oh wow.

Obi’s chuckle brought her back from her fascination. “Why are you hiding, sweetie? C’mere. This is my friend Aki-chan. Aki-chan, meet my flatmate, Shirayuki.”

“Nice to finally meet you, Shirayuki,” the guy shook her hand excitedly. “I’ve heard so much about you.”

A pity I can’t say the same about you, Shirayuki thought. “Nice to meet you, uh, Aki...chan?”

The guy laughed. Even that sounded infuriatingly charming. The corner of his eyes crinkled as he continued to smile at Shirayuki. “You can just call me Aki. It’s embarrassing enough that Obi uses ‘-chan’ on me. I mean, it’s not that I look like a little Japanese girl, right?”

“U-um…”

Obi slung his arm around his friend’s shoulder. “Aww, come on, Aki-chan. It’s cute, and you’re cute!” He poked Aki’s cheek playfully and Aki pretended to bite his finger. “Besides, ‘Aki’ is also a Japanese name, so, why not?”

Shirayuki suddenly felt out of place in front of the two guys bantering about proper use of names and name ender, like a third wheel on a date, though this wasn’t one. Or wasn’t it? In any case, Shirayuki could do without watching her flatmate flirting with a hot hunk and started to head back to the living area. She had to get ready to meet Yuzuri anyway. She almost managed to escape to the bathroom when a hand on her arm stopped her.

“Whoa there, young lady.” Obi was scowling at her. “I wasn’t sure this morning but now I see it clearly. What’s wrong with your feet?”

Damn, she was found out. She had been hoping that Obi wouldn’t notice her slight limping. The pain had started yesterday after work. She had been wearing ballerinas that day, on Yuzuri’s insistence.

Just what do you think you’re wearing?! This is your first lunch with him! You know how extremely little time Zen has! You can’t waste time going to your locker to change shoes! Just wear these today, they’re lady-like but don’t have heels so you should be fine!

But Shirayuki was not fine. Not at all. Apart from the numbing pressure she felt on her soles at the end of the day, intermittently there was a pricking pain at the base of her right big toe. She was assuring herself that the pain was only temporary and that it would go away after she cushioned her feet in her comfy sneakers today.

“Oh, it’s nothing. Just a bit of pain. It’ll go away soon.”

To her surprise, Aki stepped forward and squatted in front of her. He looked thoughtful as he eyed her bare feet. Shirayuki held back the urge to curl her toes and hide them from his scrutiny. “Have you been wearing too small shoes lately? Your skin looks raw in some places.” Then, to Shirayuki’s horror, Aki reached out his hand towards her and she took a step back in reflex.

“Really, it looks worse than it actually is. Don’t worry about it.”

“Hmmm…” Aki stood up slowly, looking unconvinced. He threw a glance at Obi, then back at her. He jerked his thumb at Obi, raising his eyebrows. “You do know your flatmate does physio?”

Well, duh. It’s not like Shirayuki hadn’t considered asking Obi for help. But Obi deserved his rest. She just couldn’t let him work 6 days a week and have her as an additional patient on a Sunday. Besides, she wouldn’t know how to feel if he said no. Hell, she wouldn’t know how to feel if he said yes. Shirayuki would never admit to anyone, not even to Yuzuri, that she sometimes dreamed of having Obi’s lovely fingers roaming over her body, caressing her tenderly, squeezing at the right places–

In any case, she was worried that things could turn awkward between them.

Before she could protest she heard Obi say, “Why didn’t you tell me, sweetie? I’d be happy to check it out for you.” Did she just imagine it or did he look slightly dejected?

“You’d better listen to him,” Aki said, rubbing it in. “And he’s really good at massages, right Obi?”

Shirayuki wanted to ask how he knew that. She was also curious whether it was common practice for Obi to give others treatment outside of work. But she couldn’t find the appropriate words without sounding so nosy, so she just sighed, resigning to her fate and promised Obi she would let him take care of her later.

*****

Seven hours later Shirayuki found herself laying on the couch with her right foot resting on Obi’s thigh. The door to the balcony was open, letting some breeze in. It would still take a while until the sun set, but at least the air had cooled down a little.

Obi’s fingers probed carefully, stretching her big toe away from the rest. His hands were so big they looked almost comical encircling her foot. From time to time he looked questioningly at her, searching for signs of discomfort.

Shirayuki hummed quietly, keeping a small, reassuring smile on her lips. She did feel a little embarrassed at the beginning – her feet being not her favourite body parts – but Obi’s pure professionalism put her at ease.

Her eyes wandered back and forth from Obi’s focused face to his clever fingers. She had never seen him in such a concentrated state before. She didn’t think it was possible for her flatmate to look even more attractive than usual, but today she was proved wrong.

Watching him work, Shirayuki wondered whether this was how Obi’s patients felt during their sessions. She wondered whether he would be that one talkative, flirty therapist everyone was fond of. She also wondered whether the way his long, slender fingers moved ever made any of them felt ...aroused. Just like how they made herself feel now–

A twinge in her chest jolted Shirayuki back from her musings. Where did that come from? She should stop being ridiculous. Obi is gay. The hot assistant from this morning was another proof.

She mentally shook her head and drew her attention back to Obi, who was lecturing her. Well, actually he was lecturing Yuzuri. He had been going at it for a while. Good for Yuzuri that she wasn’t here. He would have chewed her ear off.

“–sure she works more at the back office, but she’s your coworker! She should know how much time you spend on your feet! To let you run around in flats like that! In borrowed flats! You both may have the same size, but every person’s feet are different! Borrowing shoes should be made illegal! I can’t believe you did that! Thank goodness it was only for one day! One day was bad enough! You could’ve seriously injured yourself–”

His words were scolding but his tone was soft, worried. “Hey, are you even listening to me?” He ground his knuckles into the middle of her sole.

“Ow-ow-ow-ow! I’m listening! And for the last time, I’m sorry!”

Obi sighed. “Promise me you’ll never do such a stupid thing again? If you’re worried about wearing clogs to your future lunch dates I’ll get you a nice pair of Birkenstocks, okay? Those are closed shoes, so your prince would never ever see your cupcake print socks.”

Shirayuki flung a cushion at Obi’s head. “He’s not my prince! And it was just a lunch, not a lunch date. I've only known him for a little more than a week!”

Obi hummed, smirking and not at all convinced. Shirayuki desperately searched for a way out of the embarrassing conversation.

“A-anyway, I’ve been wondering. Is Aki a model?”

“Huh? Aki-chan?” Though he seemed surprised by the drastic change of subject, Obi decided to humour her. “Does he look like one to you?”

Shirayuki raised a brow. Doesn’t he look like one to you? “W-well, he’s very handsome, a-and very well built, just like those male models from the magazines, so I thought...”

“Heee…” Obi’s smirk grew wider. “And here I thought your type is more of a delicate, classy looking bocchan like your prince.”

Shirayuki gritted her teeth in frustration. This change of subject was not working well. To her mercy, Obi dropped his teasing, though not his smirk, and answered her question. “Believe it or not, Aki is also a physiotherapist. He works at that big health centre near the main station.”

Ah, a fellow physiotherapist. That explained his actions this morning, Shirayuki thought. “I see. And how did you two meet?”

Obi gently replaced her right foot with her left one on his thigh. “Let’s see...We met at that training I went to in January. We had to work in pairs and he was assigned to be my partner. It wasn’t long before we found out that we both speak English and immediately after that we kind of clicked. It turns out he’s also from here. So we’ve been staying in touch since then.”

“Oh, then you’ve known each other for quite a while.” Shirayuki wondered why Obi had never mentioned him to her before. Though she was burning with curiosity, Obi must have had his reasons, so she held back her questions. “Is that how he knows how good you are at massages?” she asked instead.

Obi shrugged. “He and I help each other sometimes. Being in the same profession we know the problem zones well, so it’s more or less for practical reasons.”

“He’s right, though. You are amazing.” Shirayuki winced and groaned as Obi put the right pressure on the right spot. When she looked up again she thought she saw a tint of pink blooming on Obi’s tanned cheeks. “Why, sweetie, you know it’s always a pleasure for me to satisfy all of my patient’s needs,” he gave her a wink. Shirayuki threw another cushion at him and he dodged, laughing.

Adjusting her position on the couch, Shirayuki thought about the new gained information. Now that she knew more about the hot assistant, there was only one more thing still nagging at the back of her mind.

“Say, do you often give treatments outside of work?”

Obi pursed his lips. “Nah, why should I work for free? I mean, I’d totally do it for a friend if they asked, like Aki–” His fingers suddenly stopped working and he gazed intently at Shirayuki. “Speaking of which, you haven’t told me the reason you didn’t come to me?”

Shirayuki cursed inside. That was an unexpected turn of the conversation. “I-I…” Think, Shirayuki, think! “...I didn’t want to bother you on a Sunday,” she settled for the safest answer she could think of. It was the truth anyway, at least one of them.

“Hmmm…” Obi tickled her sole and Shirayuki pulled her foot away with a yelp. When he turned to her his expression was kind. “Next time don’t hesitate to come to me, okay? Even if it’s on a Sunday. I’ll always have time for you.” Then his expression turned stern, “Though, I forbid you to come back with this kind of stupidity again, you hear me, young lady?”

Shirayuki gave him a mocking salute. “Yes, sir!”

“Good. I’ll go grab the salve for your chapped skin.”

Shirayuki watched Obi disappear into his room and then blew out a long breath. That was close. She hoped Obi believed her. It’s not like she could tell him she didn’t know how to handle getting turned on by the view of him massaging her feet. She patted both her cheeks firmly.

Better order that Birkenstock soon.

——————–

Notes:

I’m not participating in the ObiYukiMadness20. It’s just a coincidence that I’ve started writing again during this event. Basically I just want to write some ObiYuki domestic fluff.

In case any of you is wondering, Aki is American born Finn and is based on the Finnish model Otto Seppäläinen.

Coffee exhibition do exist.

Guess in which country this was set? :D

Big thanks to @claudeng80 for beta-reading <3

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EXHIBITION PLANNING

In week five; we were asked to plan an installation of our own works for a cohort exhibition in weeks 9-12. We didn’t necessarily have to have any completed works by the submission of the mockup, so I went to work in planning a small scale installation with a textile work. I wasn’t sure how to go about planning the textile piece in particular, so I made a quick sketch of some of the ideas I had in mind (left image).

Pinterest is the source for most of my inspiration. I curate very specific boards with images that fit a certain aesthetic or interest. For uni; I have a single board for all of the images that i’m either inspired by or like that look of. There are original artworks from artists, textures, spaces and objects. I can’t specifically say my process in terms of what inspires/attracts me and what doesn’t but there is a very obvious trend in the sort of aesthetic i’m interested in creating. The link to my semester two board is below:

https://pin.it/wiTJuhm

For the exhibition, however, there were some really specific points of inspiration. particularly the texture of tentacles on jellyfish and portugese man-o-war. The concept of angels in the modern world was also another point of exploration in this work. I wasn’t necessarily brought up to be a Christian, but I attended a Christian school and am relatively familiar with the idea of these ethereal beings that are supposed to be our protectors. As a child, my angels were nature - they were the spiders and the mushrooms and the ocean. It was really hard for me to picture these human-like creatures as my guardians - as I was primarily failed by most of the actual adults in my life (particularly my mother).

I ended up deciding to create this hanging textile work that is pictured in my proposal sketch (middle image). The form of the sculpture is reminiscent of a jellyfish however it isn’t necessarily a sculpture of a jellyfish, I also drew inspiration from the old mosquito nets/bed curtains that I had as a child (example below).

I mainly just wanted to expand from canvas work and into a process that was more practical and involved and had a variety of elements involved in the creation of it.

There are still four 10x10cm canvases that will be installed alongside the hanging sculpture (right image).

0 notes

Photo

LA-based Noysky Projects and the Cph-based Syndicate of Creatures in Collaboration:

Empedocles' Ghost – an exhibition about exploring science and mysticism's forgotten relationship

On view: July 4-11, 2019

Opening Reception: Thursday, July 4, 5-8 pm at KRÆ Syndikatet (Warehouse9), Copenhagen

Live performances: Sunday, July 7, 4-8 pm

Artist talk and performance: Monday, July 8, 5-8 pm

Curated by Sean Noyce

Artists: Naja Ryd Ankarfeldt and Elena Lundquist Ortíz (DK), Michael Carter (US), Jenalee Harmon (US), Alexander Holm (DK), Larry and Debby Kline (US), Sean Noyce (US), Camilla Reyman (DK), Samuel Scharf (US), Katya Usvitsky (US), and Melissa Walter (US) (see below for more on the participating artists)

Performers: Alexander Holm & Mads Kristian Frøslev (DK), Mycelium (DK), Morblod (DK), and Family Underground (DK)

Empedocles' Ghost

“The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.” — Albert Einstein

KRÆ syndikatet and Noysky Projects presents Empedocles’ Ghost, a week-long exhibition and series of performances featuring works that explore the relationship between science and mysticism. Empedocles’ Ghost is a collaboration between artist-run galleries KRÆ syndikatet of Copenhagen and Noysky Projects of Los Angeles. Empedocles’ Ghost is Noysky Projects’ first off-site, international exhibition, which opens at Warehouse9 in Copenhagen.

Scholars have ruminated on the connection between science and spirituality for thousands of years, applying folk pedagogy to explain the complexity of the world. The Greek philosopher Empedocles was one of the first to formalize this concept, stating that the foundation for all matter consisted of earth, wind, fire, and water. Respectively, Buddhist, Egyptian, Babylonian, Hindu, and Chinese scholars also drew connections with the four elements, emphasizing the universal nature of this concept.

But with the widespread implementation of the scientific method, science and religion separated, leaving folk practices like alchemy and esotericism to decline precipitously. The fallout from this schism has fostered the rise of literalism, pitting the definitive logic of science against the ascribed doctrine of religion.

Many of the works in Empedocles’ Ghost reconnect the fields of knowledge with that which is mysterious: Melissa Walter mines from her work as an illustrator for NASA, referencing near-fictional concepts like string theory, dark matter, and gravitational lensing, while Michael Carter’s interactive sculpture based on the methods of the ancient Egyptian harpedonaptai (“rope stretcher”) aligns the earth-bound viewer to the celestial bodies with great precision.

Some link the technology of today with the supernatural: Sean Noyce’s video projection renders data visualizations from sound frequencies of an ancient Greek funeral song, while Jenalee Harmon’s laminated transparent sequential photographs are an ode to time, space, speed, and technology of the Futurists that subtly allude to the hidden entities behind those forces.

Others reference Empedocles’ contribution to science and philosophy: Debby and Larry Kline’s large format pen and ink drawings of the four elements contain the visual language of illuminated manuscripts, while Samuel Scharf’s sculpture alludes to Empedocles’ himself, who was said to have committed suicide by throwing himself into Mount Etna; Scharf playfully invites viewers to toss a period-styled sandal into a ring of cobblestones, loosely referencing the active volcano.

About the artists

Sean Noyce’s Funeral Procession merges the technology of today with the mysticism and rituals of antiquity. Sampling a modern recreation of an ancient Greek funeral song, Noyce stretches the recording over 100 times so that the audible moments are abstracted to haunting drones and chimes. The recording is then imputed into a program that Noyce has written, rendering visualizations from those sound frequencies. The video projection references the fleeting moment when the spirit leaves the body as it travels between the transitory plane between the living and the dead.

Debby and Larry Kline’s The Alchemist is part of a large-scale installation devoted to the living cycle of trash. The main character is both ancient and modern. His garb is based on Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) jade burial suits. Through a contemporary translation, he has become a sleek superhero, emblematic of industry. The Alchemist shapes our world by creating value added products from raw or recycled materials, though his tendency towards overproduction is often to our detriment. We have created many drawings detailing his journey. The drawings in this exhibition are based on the alchemical principles of the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire).

Samuel Scharf’s sculpture alludes to the ancient Greek philosopher, Empedocles, who was credited as one of the first to theorize that all matter consisted of the classical four elements of earth, air, water, and fire. Empedocles was said to have committed suicide by throwing himself into Mount Etna so that the people would believe his body had vanished and he had turned into an immortal god. Scharf playfully invites viewers to toss a period-styled sandal into a ring of cobblestones, loosely referencing that dramatic moment at the volcano.

Michael Carter’s Solar Alignment reconnects the viewer to the hidden forces, properties, and geometries that bind the universe. Not unlike a neolithic earthwork, Carter’s interactive sculpture positions the earth-bound viewer with the sun using technology of the ancient Egyptian harpedonaptai (“rope stretchers”). As the viewer grounds themselves near the square patch of soil at the corner of the Euclidean triangle, they are positioned in alignment with path of the sun, represented as a golden disc perched high up in the gallery. Solar Alignment stresses the importance of hidden affinities and shared experiences that affect us on a deep, visceral way, and have inspired higher thinking for several millennia.

Jenalee Harmon’s photographs represent the liminal space between two distinct moments in time: the one that has just passed and the one that is yet to come. Meticulously produced and staged, her works are inspired by the theatrics of performers, magicians, illusionists, and trick photographers of 20th century cinema. Harmon’s sequential photographs exemplify a world in constant motion — an ode to time, space, and speed of the Futurists, machine learning and technology of artificial intelligence, and the mystery and intrigue of the supernatural.

Melissa Walter visually explores concepts concerning astronomy and astrophysical theories. Walter has worked as a graphic designer and science illustrator for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and as a team member of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Her experience has inspired her to visually articulate wonders of the Universe, such as black holes, supernovas, neutron stars, dark matter and more recently, dark energy. Walter’s use of sound, dramatic optics and lighting within her sculptural installations embed a transcendent quality to the experience of her work while infusing cosmic energy into ordinary materials such as ink and paper. She translates and materializes the intangible knowledge of the Universe into an aesthetic physical reality for a personal experience.

Camilla Reyman work within the fields of abstract painting, sculpture and installation art. She investigate the thought of consciousness being as a kind of matter and that matter might have agency of its own. Camilla prefer working with materials made by non-humans: plants, silk, dirt, bees wax, organic pigment etc, and sees her works as collaborations where her artistic intentions and the materials themselves create the final outcome on equal terms.

I am interested in how materiality has been perceived through out human history: how it is surrounds us in everyday objects, how it has been and is used in shamanic practices and how it is researched in science and dissolved in quantum physics.

Alexander Holm GiVa1G is a wooden usb drive amulet holding a number of files documenting an exploration of hollow oak trees collected in the southern forests of Norway in summer 2017. The drive includes sound, images and video, aswell as 1 hour of music based on these files. The material were collected in company with biologist Ross Wetherbee, and are originally thought to serve the Norwegian University of Life Sciences's research on the fading numbers of hollow oaks in Norway and the impact they have on local biodiversity as well as our time's global mass extinction. The files on the amulet captures a specific process, which goes as follows: When an oak tree is 2-3 hundred years old a goat horned beetle eats halfway trough the tree into the core of the trunk to eat it’s marrow. The beetle carries a virus that infects the tree to let it die slowly over the following 4-9 hundred years as a hollow grows inside it. As time passes the hollow hosts an increasingly huge number of plant and insect species which only exist in the conditions of the tree. The files points towards a specific time and place: Scandinavia around 1st millennium. Covered in forest — “Trees Of Life”. Norns sitting at the foot of Yggdrasil spinning the fade of humanity. A dragon slowly eating the roots. A squirrel bringing messages from the dragon to an eagle. The eagle sits in the crown watching over middle earth. On it’s beak sits a hawk waving its wings, pushing the winds. Somewhere else four deers are resting, eating off the crowns leaves.

Nymphaea/Åkande by Daughters of the 12th house (Naja Ryde Ankarfeldt & Elena Lundqvist Ortíz) Growing from a society that sees the human as outside, beyond or above nature, we initiated an exploration of the nature that is closest to us: our own bodies and the space surrounding. By very concretely placing our bodies directly on paper as templates and tracing the outlines of our limbs in different postures. Through the union and crystallization of our two practices and bodies, a new body emerges, that appears as an inversion of the Vitruvian Man. Rather than reproducing the narrative of anthropocentrism, and the white male human form as the measure of all things, Nymphaea re-figures the human as always entangled with other species. Using this method we want to craft another story of the human. The work is influenced by spiritual practices in a secularized society, in an attempt to re-integrate spiritual and material worlds. The project is part of an ongoing research and collaboration, where we use tarot and astrology, and more concretely investigating the 12th house, which represents the mystical and unknown dimensions of life. Initiating our collaboration we drew the tarot card “Philosopher of Stones”, more commonly known as “Page of Pentacles”, as a guide for our composite energy. The card renders a human in a lotus position that is also used as template for Nymphaea.

Katya Usvitsky’s sculpture explores concepts of birth, growth and decay through the process of alchemy. Using women’s pantyhose as her primary material — a vestige from Victorian-era corsets and garter belts that constrict the female body — Usvitsky allows the materials to blossom, infusing her sculpture with energy that give the materials a new life, outwardly reminiscent of biological processes including cell division, mutation, and replication. The mysterious transmutation of the piece can be observed in the bell jar, as the piece is on the verge of becoming too large for its vessel.

Schedule of Events

Thursday, July 4, 5-8 pm: Opening reception Sunday, July 7, 4-8 pm: Performances by Morblod (‘Motherblood’); Alexander Holm /Sensorisk verden; and Family Underground Monday, July 8, 5-8 pm: Performance by Mycelium; Talk about the forgotten relation between science and mysticism, lead by curator and artist Sean Noyce (US); art-theorist Astrid Wang (DK); and participating artists Camilla Reyman (DK), Katya Usvitsky (US), and Melissa Walter (US). Thursday, July 11: Closing reception

Location

KRÆ syndikatet: Halmtorvet 11B, 1700 Copenhagen V Walking directions from Central Station: Head northwest on Reventlowsgade toward Istedgade; turn left onto Istedgade; turn left onto Helgolandsgade; at the roundabout, take the 3rd exit onto Halmtorvet; Turn left; Turn right; Turn left at Onkel Dannys Pl. Copenhagen V

https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Hovedbaneg%C3%A5rden+(Reventlowsgade),+Gammel+Kongevej,+K%C3%B8benhavn+V/WAREHOUSE9,+Halmtorvet+11A,+1700+K%C3%B8benhavn/@55.6711786,12.5595428,16.86z/data=!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x4652530cdf75ad83:0x8cd0951af261077e!2m2!1d12.5633991!2d55.6727713!1m5!1m1!1s0x4652537317cadaf9:0x506feac8da5b78f1!2m2!1d12.5609999!2d55.6694788!3e2

0 notes

Text

Throughout my career, I have worked to make a name for myself as a thought leader in the independent school world, specializing in strategic marketing and communications for schools. Having held positions in both admission and marketing, I used my passion for education to help make a private school accessible for students. Let’s face it, you can’t attend a school you don’t even know about!

But something many people don’t know about me is that I have also taught creative classes to students. Throughout my career, I have worked with talented middle and high school students on a variety of creative projects. I helped a group of high school students completely revamp their newspaper and create an awesome publication. I worked with middle school students teaching public speaking, digital photography, and yearbook – all elective courses. And, I worked with domestic and international students on marketing projects ranging from design and illustration to blogging and video production. I have to admit, I absolutely LOVED working with the students in the classroom, especially leading them in creative and artistic activities.

Think Bigger

For most of my life, I was envious of people who were natural artists, able to realistically replicate the world around them on paper and canvas. I grew up at a time when computers weren’t in every home and didn’t contribute to the creative world like they do today. But, I attended a high school and college that fostered a love of not just art, but creativity. I never mastered drawing, but what I took away from those experiences was the knowledge that I could be an artist, and that art and creativity weren’t mutually exclusive. As a result, I found a creative passion that I never knew I had within me.

Fast forward a little more than a decade. I was a teacher and administrator at a junior school in Massachusetts. The summer before my fourth year at the school, I took a trip out to Mass MOCA to view an exhibit of the work of Sol Lewitt, an artist I studied in college who helped me even further widen my once narrow vision of what constituted art and creativity. I walked away feeling energized and excited about bringing some new inspiration to my classes.

One of the many hats I wore at that school was Yearbook Advisor, an elective course for seventh and eighth graders. I had this wonderful idea of infusing our yearbook with influences from Lewitt, but my enthusiasm wasn’t translating to my students. I showed them slides of his work and talked about his work with publications. They weren’t nearly as excited as I was, but the reason why wasn’t what I expected. It turns out, I was thinking too small. The yearbook wasn’t enough.

Why would we want to just do something in a yearbook that was created by a small group of students and would get looked at for a few months and then put on a shelf? We wanted to do something bigger, better, more permanent, and involve the entire school!

Enter inspiration from Sol LeWitt’s “Wall Drawing #797” – an intricate piece of art created by multiple artists working together with precision, patience, and persistence. This isn’t an easy piece to create. Check out this time lapse video from Blanton Museum of Art, as they create Sol LeWitt’s “Wall Drawing #797.”

But a little challenge never bothered me. So, I charged my students with re-recreating this, involving the entire school. First, we created a “smart” wall drawing using the smart board in the computer lab, teaching them about the process that would go into this type of installation.

A School-Wide Project

The process was the most exciting part. As the preliminary drawings within the class itself began to unfold, the students started to realize the importance of consistency and staying close to the previous line, and they knew the type of line that was drawn with greatly impacted the type of final product we would get. They had a plan to create a school-wide project and it was time to get started.

We found a long wall that we could work on, behind the auditorium. We did the math, and learned that if every student and faculty member in the school added one line, one drawing wouldn’t fit. Accounting for the fact that we likely wouldn’t be nearly as precise as the artists in the video above, we made the decision to split the wall and create two individual wall drawings. Fortunately, the space we chose was perfect for this.

The class decided to not use the same primary colors as the original wall drawing, and instead opted for one drawing to be in warm colors (red, orange, and yellow) and the other to be in cool colors (blue, green, and purple).

We started with eighth graders, who stood on benches to draw their lines at the top of the wall, and worked our way down the grades, all the way to the PK-3 lower school. Every student was invited to participate and had the opportunity to draw a line. The art teachers were supportive of the effort, and most opted to take one period from each class to come over and add their lines to the wall. Some students were so excited that they wanted to autograph their lines or draw lines on both walls. It took several weeks and a lot of collaboration, patience, persistence, and even begging to complete our two wall drawings, but we did it.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The Outcomes

The best part of this project was what my students took away from the effort. They learned that the length of the wall made drawing the lines a bigger challenge than they expected. In fact, drawing a line was harder than they expected. They also realized that it was nearly impossible to “fix” a rogue line. When a student didn’t stay close enough to the line and large white spaces appeared, some students tried to fill in the space with extra lines, but then they realized that the new filler line wouldn’t match the subsequent line and would also mean that the color sequence would be off.

As the wall was coming together, the students started coming up with ideas on how they could improve it if they were to do it again. They talked about using paper to block off space below the lines, forcing people to stay closer to the original. There was an idea to time the artists so they didn’t rush their lines, forcing them to move slowly to avoid making lines too flat or adding swoops in where they didn’t belong. While initially autographs weren’t part of the product’s scope, the students started to embrace the idea of signing their work. But, they realized there needed to be some rules. So, they suggested having a designated place for signatures, keeping them neat and tidy and not randomly spread around, disrupting the flow of the drawing. This was all exactly what I wanted to hear. The students were learning, improving, and preparing for future initiatives. As a teacher, I couldn’t have been more proud of my group.

Was the finished product perfect? Absolutely not. But was it awesome? Absolutely yes. This wasn’t about creating the idyllic Sol LeWitt replica; this project was about bringing together our community to create something special together. Each perfect and imperfect line is representative of the students and faculty member who drew them, and how each of us plays a role in creating a community.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Throughout my career, I have worked to make a name for myself as a thought leader in the independent school world, specializing in strategic marketing and communications for schools.

0 notes

Text

A Performance in Queens Got Right What That Pepsi Ad Got Wrong

Performance by Àṣẹ Dance Theatre Collective. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

The past week has been a busy one for the art world. In Athens, Adam Szymczyk opened the first half of his documenta 14, the first edition in which such a large portion of the quinquennial show takes place outside of Kassel, Germany. In Venice, collectors ogled and Instagrammed their way through Damien Hirst’s splash back into the center of art-world attention—a massive, for-sale museum show spanning François Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, where a single, barnacled sculpture can reportedly run you north of $5 million. A performance in Queens, however, drew a very different audience—the parents, friends, and children of some 350 members of the community that took the stage—and packed a punch to the gut, rather than the wallet.

Protest Forms: Memory and Celebration: Part II (2017) is the work of Berlin and London-based, Italian artist Marinella Senatore and couples with her first American museum show “Piazza Universale / Social Stages” at the Queens Museum. It lasted for a little over two hours on Sunday afternoon and involved members of the Black Panthers, Black Lives Matter NYC, Middle Eastern folk music ensemble the Brooklyn Nomads, Indigenous Aztec dance group Danza Azteca Chichimeca, world champion jumping team FloydLittle Double Dutch, the Lesbian & Gay Big Apple Corps Symphonic Band, members of the Martha Graham School, rapper and activist Mysonne, and many, many others.

Participants were recruited to take part via the Queens Museum’s numerous community outreach programs, via referrals, and via Senatore’s own network. Each group was given a few minutes (which many, in their excitement, took the liberty to extend) to dance, drum, speak about their community’s current struggles as well as their histories of protest, sing, and then recede back into the audience as the next leaders of this great, circuitous, stop-and-go processional moved into the fore.

Performance by Batala New York. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

The performance is a follow-up to one Senatore staged for the Quadriennale di Roma last year, curated by Matteo Lucchetti, who also organized the Queens Museum show. It continues a core tenet of her practice, which takes a given community as its inspiration. In the past, that’s seen her create Rosas (2012), a roaming, multifaceted opera using 20,000 majority-amateur performers hailing from Spain, Germany, and the U.K.; and Speak Easy, a 2009 initiative that brought together over a thousand students and retirees from the periphery of Madrid to collaboratively create a film.

I watched a processional of Rosas in 2012, down Berlin’s Auguststraße to her former gallery Peres Projects’s former Mitte location (she’s now represented in the city by KOW and by Laveronica in Modica), and have seen films and other documentation for a number of Senatore’s past initiatives. I’ve enjoyed the work and thought her artistic approach to be genuinely interesting—if at times more so for the participants than the viewer. But on Sunday, artist, artistic approach, location, and present moment combined to create not only what I’d argue is Senatore’s magnum opus to date but also the most impactful work of art that went on view in the past week.

Senatore spent nearly three months working with members of the community to create Protest Forms. She choreographed the order and placement (though not the content) of each group’s performance both inside and outside of the museum. She also initiated an open call to Queens residents, asking them to submit local protest songs and the sounds that remind them of their neighborhood, which she then gave to Italian composer Emiliano Branda to create an original score titled Queens Anthem.

Performance by Bangladesh Institute of Performing Arts. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

In the span of a month that has seen the art world embroiled in fierce debate about Dana Schutz’s painting of murdered African-American teenager Emmett Till, Open Casket (2016), and the nation relatively more united in condemnation of Pepsi’s appropriation of protest and racial stereotyping in its now-infamous Kendall Jenner-starring ad, “Live for Now Moments Anthem,” Senatore’s work stands out for at least two reasons.

First, as Antwaun Sargent wrote for Artsy, the controversy around Schutz’s work “is, at its core, about the failure of the art world to truly represent black humanity, despite its recent insistence on “diversity,” and Schutz’s own attempt to empathize with the struggles of black Americans through her empathy with Till’s mother, Mamie Till, as a mother herself. Senatore is a white artist, and the Queens Museum, despite being located in the most diverse neighborhood in the world and having one of the more diverse staffs in New York City, is a white-run institution. But the artist’s and the museum’s role in Protest Forms was to provide a space, a time slot, and to move the audience into position to watch—in essence, to present whatever those who chose to participate wanted to put forward as their experience.

When Mahogany Browne, Shanelle Gabriel, Jive Poetic, and The Peace Poets each stood on the corners of the rectangular recess that makes up the museum’s Skylight Gallery just off its atrium and Black Creative Brilliance (BCB), Black Lives Matter NYC’s Arts & Culture Crew, at its center, there was little direct attempt on Senatore’s part to contextualize or represent their lived experience. Rather, she listened—and subsequently provided a venue for others to listen too.

Performance by Graham 2 from the Martha Graham School. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

It was one of two instances in the course of the performance in which music and spoken word poetry paired with actual physical resistance. In this case, words about police brutality, racial discrimination, and gentrification were rapped and recited into microphones and megaphones over the shuffling of feet and clashing of shoulders of young men from the Queens chapter of the youth wrestling program Beat the Streets.

In the other, two girls from the Women’s Initiative for Self-Empowerment—a self-defense, social entrepreneurship and leadership development movement for young Muslim women—practiced moves used to ward off a rising tide of racially motivated attacks that often begin with hijabs being snatched from atop Muslim women’s heads. They performed in front of the Unisphere globe created for the 1964 world’s fair, while folk musician Joshua Garcia played Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” and Pete Seeger’s “Which Side Are You On?” in the background.

In both cases, the combination was Senatore’s suggestion initially but one immediately taken on by both sets of participants.

Second, as Senatore’s performance’s title suggests, it is not simply a recording of past and current struggles and means of resistance but also a celebration of the many-layered community in which it takes place. Particularly exuberant were the parents of youth from the mariachi school Academia De Mariachi Nuevo Amanecer, who played under Anna K.E.’s installation in the Queens Museum atrium—one of 3 other exhibitions that opened on Sunday afternoon. But throughout Protest Forms’s two-plus hours, whether in the tap dance of Marshall Davis Jr., the step dance of the Lady Dragons from Brooklyn Technical High School, the bullerengue music of Bulla en el Barrio, the dance of the Bangladesh Institute of Performing Arts, or the singing of Jamaican vocalist Abby Dobson, a sense of creativity-induced unity was palpable.

Performance by Lesbian & Gay Big Apple Corps Symphonic Band. Courtesy of the Queens Museum. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

It’s the kind Pepsi ad director Bjorn Charpentier misguidedly tried to fabricate and package to sell cola. But it’s also a vision of America—one in which we celebrate our differences and listen to the struggles of our neighbors—that many of us hoped would be currently being furthered by a very different executive branch. Mounting that vision in the Queens Museum building, which initially served as the home of the General Assembly of the United Nations, and under the Unisphere globe isn’t just a brilliant example of the power of art, and particularly social practice, to tell our collective story. It is also an important reminder that if we listen and we collaborate, that vision is not at all lost.

—Alexander Forbes

from Artsy News

0 notes