#i added pinyin for the poetry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

春怨 - Spring Bitterness

春怨 - Spring Bitterness by 刘方平 (Liu Fangping, ~Kaiyuan Era, 713 to 741)

纱窗日落渐黄昏 shāchuāng rì luò jiàn huánghūn Beyond the silk window, the sun sets, yellow fading into dusk.

金屋无人见泪痕 jīnwū wú rén jiàn lèihén Within the gilded house, no one is here to see her trailing tears.

寂寞空庭春欲晚 jìmò kōng tíng chūn yù wǎn In the lonely silence, in the empty court, Spring longs for the close of day.

梨花满地不开门 líhuā mǎn dì bù kāi mén Parting’s blossoms carpet the way… to a door that does not open.

..............................................................................................

春怨 | Spring Bitterness is one of two homework poems (the other is 月夜 | Moonlit Night), for a poetry translation workshop hosted by Chenxin Jiang that ran from Jan to Feb of this year. Both are from the anthology 唐诗三百首 Three Hundred Tang Poems and were written by the Tang Dynasty poet and artist Liu Fangping.

Side note that no one asked for but that I always feel obliged to mention xD: Three Hundred Tang Poems does not collect the best of the best Tang poetry, that wasn’t the intention! Compiled by 蘅塘退士 Retired Master of Hengtang in 1763, Qing Dynasty, these were mostly popular works and poets from the Tang Dynasty during the Ming/Qing Dynasties (probably skewed toward his own preferences too lol) intended for a beginner or a child's gentle introduction to Tang poetry. This is also why many modern editions you will find at the bookstore today have the poems organized according to poetic form.

Poetry and Song

youtube

I found this cool video of a teacher, 吳秀真 Janice Wu, first reading Liu Fangping’s 春怨 then singing it in Hokkien. Sharing this here so we can appreciate the rhythm, rhyming and their effect in the poem together!

To help this along, another line which represents the tone pattern has been added. In Pinyin, the romanization system for mandarin which is used here, there are four tones.The first (◌̄) and second (◌́) tones are Level - longer sounds that are represented by the ‘_’ underscore in this notation. The third (◌̌) and the fourth (◌̀) pinyin tones are Oblique - shorter sounds represented by the ‘\’ backslash. The third tone is one that starts level, dips, then goes up again, and the fourth has an almost staccato rhythm. Words with Oblique tones are also bolded in the pinyin.

纱窗 | 日落 | 渐 | 黄昏 gauze window | sunset | gradual | twilight (lit. yellow, darkening) shāchuāng | rìluò | jiàn | huánghūn _ _ \ \ _ _

金屋 | 无 人 | 见 | 泪痕 gold house | no one | sees | tear tracks jīnwū | wú rén | jiàn | lèihén _ _ _ _ \ \ _

寂寞 | 空 庭 | 春 | 欲 晚 lonely silence | empty hall | Spring | desires lateness jìmò | kōng tíng | chūn | yù wǎn

\ \ _ _ _ \ \

梨花 | 满 地 | 不 | 开 门 pear blossoms | fill floor | no | open door líhuā | mǎn dì | bù | kāi mén _ _ \ \ \ _ _

Title

Now to the title - 春怨 chūn yuàn (lit. Spring Laments). There is a trope in poetry called 怀春 huái chūn embracing spring (lit.). You may have heard of the sexual connotation, and it can be that! But a lot of the time 怀春 is also a romantic thing. Being attracted, being drawn by beauty like the bright and lively sceneries of Spring, it’s natural to want to share the moment with someone close to her.

A twist on this trope comes when that person - a lover, a husband - isn’t around or can’t be around. There could be lots of reasons, ok? Like being called away to war, separated because of politics, posted to distant counties and difficulty uprooting the family to move for a three-year thing - in other words, life giving lemons in general or simply that his heart is not here. But whatever it may be, this is how you get a flaw, a regret, a dissatisfaction, some unhappiness in a life... and now we feel 怨.

Spring itself is also very about the world waking up again, a time of renewal where life is everywhere (or the seeds of it are being sown… literally!) and the year is young. A person’s youth is also often compared to Spring, and its passing or a ‘wasted youth’ is something worthy of regret.

The genre of poetry in which the speaker or main focus is a sorrowful lady usually for any form or combination of the mentioned reasons is called 闺怨 guī yuàn boudoir repining. It’s also called 宫怨 palace lament when the focus and setting is on the ladies - the empress, a concubine and so on - in the palace. (Roughly 10% of the Three Hundred Tang Poems are of the boudoir/palace repining genre. I really can’t help but wonder if this is one of the editor’s favoured tropes.) Such poems could be written by ladies, but the theme was often co-opted by men who used it to express adjacent feelings e.g. not being appreciated by their bosses (xD), failure to attain office via the state exams and so on. This is what has happened here for our poem of the day.

So now, Liu Fangping, what laments do you have for us this Spring?

[Family background check, praise and gossip - come get the scoop on Liu Fangping, beautiful man and mountain hermit from the Height of Tang Dynasty.]

Reading

The setting for this poem is in someone’s room, before their window. From it, they can see the fallen pear blossoms across the floor outside and the closed door.

Time for clue hunting to get some more context.

Who

The use of 纱 shā gauze, a light silk with an especially airy weave, as window screens was not something the average commoner family could afford.

(Source)

We know the POV character is in their room and facing their window, enough to observe the sunset. They must be indoors. What sort of building? The next line tells us it’s a 金屋 jīnwū, literally translated, that would be golden house - but this is should not be taken literally. This is actually a reference to the ‘urban legend’ (or maybe RPF as we call it these days LOL) that gave rise to the idiom, 金屋藏娇 jīn wū cáng jiāo a golden house to keep one's mistress (lit.).

As collected by 班固 Ban Gu (32 to 92 CE) in his 汉武故事 Stories of Emperor Wu of Han, the story goes:

数岁,长公主嫖抱置膝上,问曰:儿,欲得妇不?胶东王曰:欲得妇。长公主指左右长御百余人,皆云不用。末指其女,问曰:阿娇好不?于是乃笑对曰:好!若得阿娇作妇,当作金屋贮之也。长主大悦,乃苦要上,遂成婚焉。 (Rough translation because I want to SLEEP) When he was couple of years old, the Grand Princess, (Liu) Piao carried him, put him on her knee and asked, “Child, do you want a wife?” The Prince of Jiaodong said, “Yes,” The Grand Princess pointed out over a hundred palace officials - similar to ladies-in-waiting - all of whom were refused. Finally, she pointed at her own daughter and asked, “Would a’Jiao suit?” And he smiled and said in reply, “Perfect! If I were to have a’Jiao as wife, I would build her a golden house and stow her away.” Delighted, the Grand Princess worked hard at convincing the Emperor to agree to their marriage and eventually succeeded.

Afterwards, when the Prince of Jiaodong also known as Liu Che (156 - 87 BCE) became the seventh emperor of the Han Dynasty, he built his Chen Jiao a beautiful palace and later officially made her his Empress. A fairytale might have ended there but while this is a story, it is also a story about real people… and so instead of a happily-ever-after, in real life we get this. The palace of gold that was built did not bring a’Jiao happiness, the childhood promise of love didn’t last half as long as the palace did, but the ironically romantic idiom that came from it outlasted them all.

Now back to Tang Dynasty in the 8th century!

Liu Fangping writes 金屋无人见泪痕. This 金屋 could hint at a broken promise of love, or it could be a hint at the identity of the lady in this poem. No matter the intent for both or either one of these though, what’s for sure is that the reason for 怨 is answered. More on this later.

When

There are three clues that answer this. First, line one tells us that it’s on an evening gradually painted in the colours of sunset (as seen through the silk screen window). Second, is how the poem’s POV tells us it seems to be late Spring in line three. Third, is the evidence that it is indeed late Spring - the fallen pear blossoms that are all over the floor in line four.

While we’re on the topic of pear blossoms, let’s segue into…

Imagery

Pear Blossoms

Observe the pear blossoms in this yard. How do you feel as you look at them?

(Source)

Each flower is so delicate and pure, their petals soft and velvety. Up close these white flowers give me a peaceful and refreshing vibe.

Pear blossoms bloom in late Spring when the weather has thoroughly warmed, around the solar term period of Qingming. They’re very fragile and are easily blown from their branches by the wind. But while they’re around and the pear trees fully blossomed, it’s a beautiful and tranquil sight to be appreciated.

(Source)

And we should appreciate them while they’re here because their flowering period is so short! All too soon, they’re strewn across the floor as time marches on.

(Source)

The sight of pear blossoms carpeting the ground is a marker of the end of Spring.

梨 lí, the word for pear in pear blossom is a homophone of 离 lí, parting, and this coupled with its image of fleeting, fragile beauty often leads to association with grief and/or mourning. Following from there, the image of a ‘sorrowful woman confined in the boudoir as her youth passes’ is easily linked and a common accompanying theme. (Yes it’s a trope xD I’ll point it out again in the future as we encounter them.)

Side note: Taking the ‘unfavoured concubine’ reading of this poem, the fact that the sun isn’t down, yet the yard is littered with flowers that likely have been there for a while and there are no servants attending to that - all of this just emphasizes ‘unfavoured’. Few would make that extra effort on a team with no future!

Empty courtyard

It is getting dark, the day growing colder and it is so very quiet in this house. The loneliness is the trigger for her tears; both the quiet and the empty courtyard from which Spring is receding only amplifies it.

Setting sun

黄昏 huáng hūn is sunset. Literally, it reads yellow-dim/dark. The movement of the light is the only thing in this poem. The sunset is gradual, dimming from the warm yellow tones of the setting sun to shadows and darkness. But the fallen white petals and flowers in the courtyard are going to be very visible until the very last of the light is gone.

In this poem, each line is a different, standalone image that stacks to build the atmosphere, expressing 春怨 perfectly.

Framed by her silk screen window, the sun goes down on her gilded house where there is no one to see, or no one who will care to see her tears. Her emotion overflows this evening because the loneliness has grown to fill her neglected yard, and she is accompanied only by the silence and the last remnants of her Spring. There is nothing for her outside, and no one comes. The door does not open.

Some pictures...

It's a rather depressing note to leave this post on, so I thought it might be on interest to all of us how a palace or a house might have looked!

Here is the scene of a banquet in a Tang Dynasty palace as imagined by an artist of the Five Dynasties or Song Dynasty some two to four hundred years later.

This painting is from the The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Visit the source for the writeup and description!

(Source)

This is an imagining of how a Tang (618 - 907) Palace concert might have looked like by a Yuan (1279-1368) Dynasty artist. Again, check out the description at the source!

(Source)

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, hope you’re doing well :D! i’ve been obsessing over all of your art and hcs of the mdzs older gen and i was wondering what your thought process of the names you chose for them were because they’re really cool!! like i was thinking how yixi’s name is probably referencing that she came from tibet or how qhj’s courtesy name is maybe referencing his position as heir then later sect leader, like him inheriting the responsibility of leading the lan clan, and maybe the night character is in reference to his quiet personality but also his future loneliness in seclusion? or maybe im just looking into it too deeply (T▽T)

hello hello!! i've been very busy, this new years is starting off with lots of farewells on my end & promises to see friends as they settle in to their lives, i hope you are well & i hope you've had a good holiday & will have a good year.

WAH you're too sweet 😭 i'm gonna be honest, a Lot of my thought process when Naming characters in general has been:

• "follow the naming process of mxtx," which means you can bet your butt i've been Carding through Tang Dynasty poetry for Months • making Absolute Sure that None of the names i settle on are homonyms for anything with a double-meaning such as: modern swear words, innuendos, or just anything in general that would make them look like a clown • do NOT be Airplane (Shang Qinghua) when naming characters- which in essence if you haven't read svsss means do Not give characters names that spell out the core of their origins. no "risen from the frozen river" names, "don't be too on-the-nose i'm Begging you do research" @ me • do your absolute Best not to choose characters with a ridiculous amount of strokes Especially for given names (a rule i've struggled to actually live by) • do your Best to not have too many overlapping characters that Canon names use • sparingly looking at the tao te ching because i'm too scared of being culturally insensitive to nitpick a name from any pinyin i might come across

i won't claim ever to be a native chinese speaker: i have enjoyed the incentive to learn characters that are the building blocks to actual words that reading mxtx's works (& subsequently other cnovels) have given me, but it is not a culture i was raised in and it is not a language i read fluently. can't speak mandarin or cantonese or suzhounese or any other dialect and have been blessed with multiple friends who do and have done their best to help steer me in the right direction. all that being said, here's some dumb facts with the names:

• regarding the last-most point, i've picked ONE name from the tao te ching. i'm glad you enjoy Chengye/承夜's name but i've deliberated over it too long and have come to the conclusion that it Will be changed. taking inspiration from qiren's name, there needs to be a verb in there paired with something abstract but innately Human & i've found a passage in the tao that i Really liked that i feel alluded to my own characterization of him had the phrase Yǒuqíng/有情 which is Just as abstract and ridiculous as Chengye (which i cannot remember where i pulled that name from), but comes with the added bonus of being from the Adjustment of Controversies. to Have affections but understand where they should be going or how they should be distributed, to question why a person favors One thing over Another despite the inevitable conclusion that All of it is working towards an inevitability completely out of a person's control, it all feels just absolutely peachy to thrust that onto qingheng-jun when he couldn't in his lifetime maintain the favor between his family & his wife. plus Wangji's name being tao-derrivative made me feel i needed at least one of the prev gen in this boat with their successors. i've studied the tao in a scholarly setting Once for a semester, and Once more for a week or two on my own time so Please do Not take my word as any level of expertise i'm begging you. • I Do remember when picking out a name for Qingheng-jun, coming across a name that in essence meant "Bear the Night" felt a little too on-the-nose. there was no double meaning though i tried applying one. he's a Leader, he's a Cultivator, it's Expected of him to bear this and bear it as if it weren't a burden. and the more i thought/think about it, the less it made sense especially when All cultivators are expected to soldier through the same conditions, yanno? • Cangse-Sanren is the only girl i've headcanon'd so-far with a courtesy name! and i Really Really wanted it to be something to do with celestial bodies Exclusively because Xiao Xingchen has the Most celestial name on this show outside of Lan Xichen but he doesn't count in my head. i also wanted it to have Anything to do with the moon because Xiao Xingchen's name has a good chunk of sun radicals in there, but also Moonbeam is what you'd call a fairy and she's a fairy and i Will Never let that go. the most buckwild batshit fairy you've ever met but a mortal worthy of being a celestial being. her Surname means Wish, so go wishing on the moonbeams because her husband certainly did. • Cangse-Sanren in my headcanons named herself. She was a whimsical child, she named herself something outlandish for her surname, & she was obsessed with the cowherd & weavergirl story as a child so she named herself Liu/浏 with the milky way in mind (here i go breaking my Not Too Many Strokes rule). • tragically Yixi's name was more utilitarian than anything else. i needed something that worked in multiple languages based on my headcanons of origin & with the limited selection i had to work with, 益西 was by & far my favorite. plus the implications of her having value, of being benificial to some far-off location that was as far away from Gusu as you could possibly get, how could i Not see the poetry in that? • Yixi has no surname. Yi is not her surname, her full name is Yixi. where i headcanon her From, surnames weren't particularly commonplace outside of nobility and i don't headcanon her family to be of major importance (though i believe they're relatively self-sustaining). She might be associated with a specific clan her family works under or for & that may come up in the future, but for now it's just Yixi until or unless you think of her as already a married Lan. jury's out on whether the Lan clan would've ever called her Madam Lan tho. • confession: Bu Xin's name was directly inspired by Unchained Love's Bu Xin. different spelling but iirc it's completely a homonym. second confession: i have yet to finish watching Unchained Love please go Easy on me

#pspspspspsp come off anon so we can be hyper obsessed freaks Together#mdzs#qourmet: aga#asks#anon#long#if i think of more to add i'll rb

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bai Juyi (also known as Bo Juyi) was a Chinese poet of the Tang dynasty (772–846 AD), and his poems had a significant impact on Japanese classical literature.

During the Tang dynasty, there were close diplomatic and cultural ties between the two nations, leading to the adoption and adaptation of Chinese literary forms in Japan.

His poetry often reflected a concern for common people and social justice. This resonated with Japanese poets and scholars who admired the clarity and accessibility of his writing.

Bai Juyi's influence on Waka can be observed in the adoption of certain themes, stylistic elements, and poetic techniques. Japanese poets admired Bai Juyi's ability to express deep emotions with simplicity.

Bai Juyi's poems often explored philosophical themes, including the transient nature of life, the beauty of nature, and the human condition.

Bai Juyi was known for his versatility, having written poems in various styles and on diverse subjects. His accessible language and relatable themes made his works appealing to a broad audience, including poets and readers in Japan who found inspiration in his approach.

Chinese literary works, including Bai Juyi's poems, were translated and adapted into Japanese.

Image: Bai Juyi (Chinese: 白居易, pinyin: Bai Juyi, Wade-Giles: Po Chü-i) (Xinzheng, Henan, China; 772 - 846) ; He was inspired by popular songs. His poetry was touched by values of Taoism and Buddhism.

edisonmariotti @edisonblog

.br

Bai Juyi (também conhecido como Bo Juyi) foi um poeta chinês da dinastia Tang (772-846 dC), e seus poemas tiveram um impacto significativo na literatura clássica japonesa.

Durante a dinastia Tang, existiram estreitos laços diplomáticos e culturais entre as duas nações, levando à adoção e adaptação de formas literárias chinesas no Japão.

Sua poesia muitas vezes refletia uma preocupação com as pessoas comuns e com a justiça social. Isso ressoou entre poetas e estudiosos japoneses que admiravam a clareza e acessibilidade de sua escrita.

A influência de Bai Juyi em Waka pode ser observada na adoção de certos temas, elementos estilísticos e técnicas poéticas. Os poetas japoneses admiravam a capacidade de Bai Juyi de expressar emoções profundas com simplicidade.

Os poemas de Bai Juyi frequentemente exploravam temas filosóficos, incluindo a natureza transitória da vida, a beleza da natureza e a condição humana.

Bai Juyi era conhecido por sua versatilidade, tendo escrito poemas em diversos estilos e sobre diversos assuntos. Sua linguagem acessível e temas relacionáveis tornaram suas obras atraentes para um público amplo, incluindo poetas e leitores no Japão que encontraram inspiração em sua abordagem.

Obras literárias chinesas, incluindo poemas de Bai Juyi, foram traduzidas e adaptadas para o japonês.

Imagem: Bai Juyi (chinês: 白居易, pinyin: Bai Juyi, Wade-Giles: Po Chü-i) (Xinzheng, Henan, China; 772 - 846); Ele foi inspirado por canções populares. Sua poesia foi tocada pelos valores do Taoísmo e do Budismo.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Poetry + Names? :D!!!! Can't resist adding ~

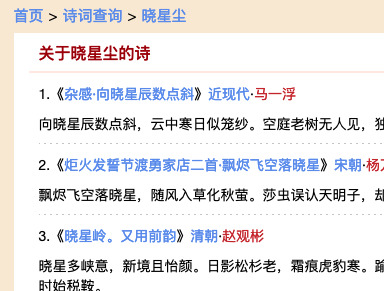

Stacking on to Hunxi's 晓星尘 example

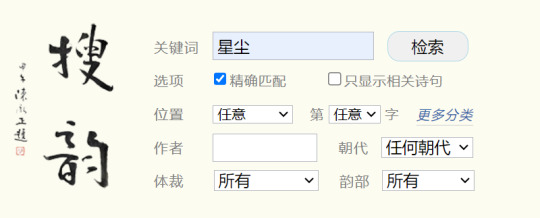

How to search for possible poetry references Another great resource that I love a lot besides gushicimingju and gushiwen (highly recommend the gushiwen app for its clean and user friendly interface if you're interested in reading poetry/exploring classics and keeping track of what you've learnt) is sou-yun.cn, which is particularly useful for searching up names and possible references because there are lots of parameters for advanced searching to chose from - like exact vs approximate match, position, dynasty etc.

Results are returned in their full poems with the text highlighted per the image below this paragraph. With the textual instability of ancient poems and all, you sometimes get alternate words - this site also displays them and their source, as you can see in the first example.

What's even cooler is that, hey, they may recognize me but I sure don't know them! What do these characters mean together? Click into the poem, select the word and you get both the pinyin and examples of usages in other poetry.

(I try to look at this only after doing the legwork for poetry club though, because this is seriously too much of a golden finger and my searching skills may grow rusty LOL)

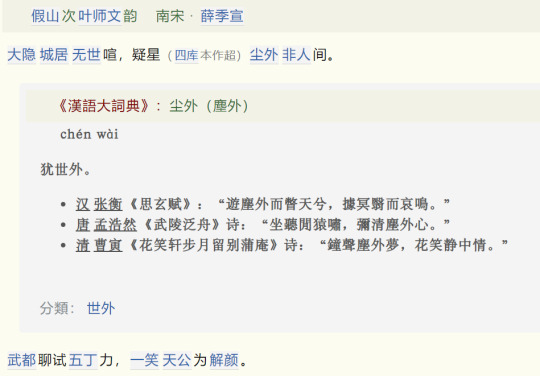

Gushicimingju is fantastic for the purpose of telling us how many instances does the word show up. Gushiwen actually returns results from texts as well as poetry which is also desirable because name inspo for Chinese characters is not limited to poetry and auspiciousness. If you select the 古籍 tab (indicated with a red dot below) and if the search term actually exists in any of the texts within the site's archive, then it will turn up. In this case for 星尘, there is none.

But besides all these bells and whistles, the difference between these sites is the pool of works available. Gushiwen only returned 5 results with 星尘 across the Song to Qing Dynasties. Sou-yun.cn gave me 9 from Song to Late Qing, and a further 7 from the Republican Era to our times. See below xD

/got sidetracked LOL

Oh, ctext is another of my fav go-tos as well!!!! But we all know that the search function there can be a little bit broken sometimes. So when you suspect that it's not working for you, a workaround is googling like this: "the characters you're looking for" ctext.

But let's say we're looking for something different, so you want to search within the site. And if for some reason, you want to know if a particular usage of a word was more popular in older texts (like Pre-Qin and Han) or later ones (like Wei-Jin and after), then use the search box like this!

星辰 with 'Pre-Qin and Han' selected returns 177 results. 星辰 with 'Post Han' selected returns 385 results.

Another method of researching a name Looking at the words themselves! Sometimes a return to simplicity works just as well (or maybe I just like digging many rabbit holes).

The Chinese baike.baidu (like wikipedia) these days has this cool etymology section 字源解说 at the beginning of the article for most words.

If you've ever wondered how people from the Shang Dynasty wrote the same word (ok it's not as simple as that xD but for the sake of not making this a long ramble let's go with this), there we go.

For 晓

And since this is a surname, don't forget to check out its origins!

For 星

For 尘

What did the words mean originally? How did they extend and drift to other meanings and when were these drifts becoming popular? Does it fit in with what you know of the character?

Does the conclusion you're drawing about the meaning of their name feel a bit forced, or does it make perfect sense and you're happy to make this your headcanon / share it as a possible fun fact?

Happy searching!

so I know that a lot of chinese names are references to specific poems. Is there a way to determine this (vs general auspicious meaning) and which poem specifically? I'd love to be able to figure this out for character names and I haven't been able to find any resources (in case it's helpful, I'd say I'm my understanding is maybe HSK4-level so I can clumsily make my way through the chinese internet with the help of a dictionary)

feel free to make this public so that others can benefit if you have any suggestions

oof... unfortunately I suspect that this, along with one's repertoire of chengyu, is something that one simply Just Learns with reading more. my personal repertoire of poetry is embarrassingly thin, so the horrible horrible process I've been going through is, well, throwing the name into a search bar and hoping for the best.

here's an example of how I (think I) went about doing this for Xiao Xingchen's name, way back when I wrote this post:

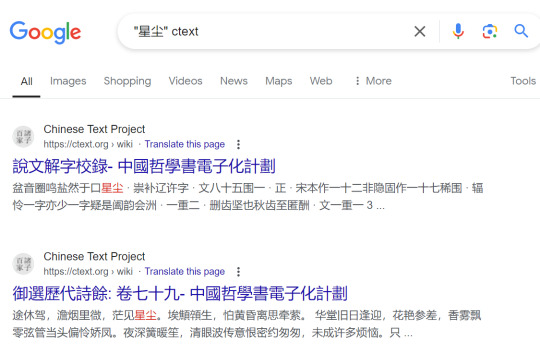

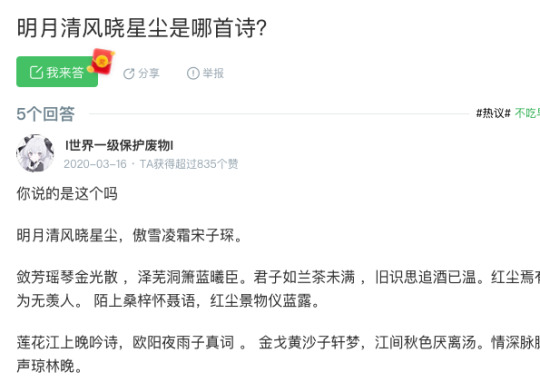

I went ahead and dropped "星尘 诗词" ("Xingchen poetry") into the search bar, which turned up this:

Generally speaking, I'll only put the name (minus the surname) because putting the character's full name into a search bar will probably turn up the character themselves, and if someone's name is being derived from a poem, it's usually independent of the surname anyway.

Xiao Xingchen's name is an interesting example because it doesn't quite come from a poem, but it doesn't not come from a poem. you can see that the search engine has automatically assumed that I am looking for poems about constellations, as "星辰" and "星尘" are homonyms, and one of these is more commonly seen. I usually consider that a solid indication that "星尘" (the name) is a novel formation of characters in a name, and not likely a poetic reference.

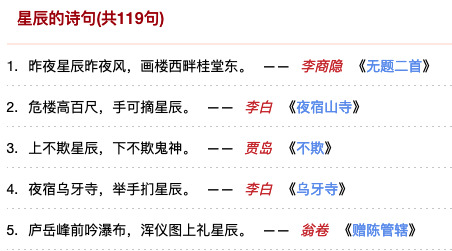

but! in for a penny, etc. I'm a huge fan of the first search result, gushicimingju, since it's a solid database of poetry and some prose. clicking into that listing informs me that gushicimingju is turning up. oh my. 119 possible matches:

note that these are matches for "星辰" (constellation), not actually our character's name. still! you can click in and peruse the selection if you'd like.

now that you're on gushicimingju's site, you can also use the search function within the site to search for more exact matches, without worrying that you'll accidentally activate the fandom itself.

looks like there's a few matches for "晓星," but nothing for the full name.

so! gushicimingju is a solid database I like to refer to most of the time. if for some reason I'm feeling particularly academically rigorous, I might also do some searches on ctext as sometimes names will come out of famous turns of phrases (a la Zhao Yun 赵云 / Zhao Zilong 赵子龙 from that post I linked earlier) rather than poems. searching the dictionary sometimes (Pleco, or zdic) doesn't hurt either. basically, I throw spaghetti at the search engine wall to see what results come back for these characters in this particular order to try and get the original referent (if any) to show up; I'll probably give up after a few permutations of search terms if nothing is actively jumping out at me

but back to the search results: sometimes, if your character is famous enough, straight up searching for "what poem is this character's name from?" will help you find like-minded people on baidu zhidao (basically yahoo answers):

although of course, take baidu zhidao result with all of the salt you would take with any yahoo answers (look for alternate sources to validate, good for a laugh most of the time)

best of luck!

#what i've learnt from this is that we're ALL rabbit holing disasters#sorry LOL i am aware this method of searching is very human unfriendly (especially if you don't find it fun hahahahah)

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

son-in-law is the cutest

From episode 29: 金风玉露一相逢,天上人间不算数。 在天愿为比翼鸟,在地愿为连理树。

Novel!canon Cao Weining is the king of messing up poetry & drama!CWN is no different. CWN's nickname is son-in-law, so I'll just be calling him SIL since that's what I'm used to; A-Xiang's nickname is "daughter". 😛

There aren’t really any hidden meanings here, just SIL professing his love for A-Xiang and foreshadows their BE 😢

The first two lines come from the poem 《鹊桥仙》. The first line: 金风玉露一相逢 Literal translation: A chance meeting when the golden winds* blow, and the ground covered with dew the colour of jade**

SIL: 天上人间不算数。(tian shang ren jian bu suan shu) Meaning: Nothing counts, whether it's in the heavens above or in this mortal world. Original poem: 便胜却、人间无数。(bian sheng que, ren jian wu shu) Meaning: But it's better than the innumerable other meetings in this world.

This poem refers to the cowherd & the weaver girl's love story, where they were not allowed to be together. One day a year, on the 7th day of the 7th month (qi xi), a flock of magpies would form a bridge across the heavenly river so they can reunite.

The whole meaning of this line is: When the golden autumn winds blow, and white dew rests on the ground, to meet (with you) just once is more than the innumerable other meetings in life.

I'm *guessing* what SIL means is: When the golden autumn winds blow, and white dew rests on the ground, to meet (with you) just once would make the rest of the world meaningless.

The next two lines come from poem 《长恨歌》: SIL: 在天愿为比翼鸟,在地愿为连理树。(zai tian yuan wei bi niao, zai di yuan wei lian li shu [tree]) Original poem: 在天愿作比翼鸟,在地愿为连理枝。(zai tian yuan zuo bi yi niao, zai di yuan wei lian li zhi [branch]) Meaning: In the skies, I'm willing to be two inseparable birds*** flying together. On the earth, I'm willing to be two branches**** interlocked with each other.

It's "interesting" that both the poems SIL/CWN quoted, well, misquoted here, are all tragic (compared to the occasionally happy endings of the love poems that Lao Wen quotes for A-Xu). The first poem talks about the cowherd and weaver girl, who can never be together except for a single day a year. The second poem is very well known, featuring Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang dynasty and his Beloved Consort Yang (Yang Guifei).

T/N behind the cut

Also i finally made a tags page, so people can find stuff. After all, 300/301 posts are about WoH. For posts similar to this, follow this tag.

*Golden winds refer to the autumn winds blowing golden leaves. **Jade dew refers to White Dew (白露), a name of a season in the old calendar, around the 8th of September. ***The bird he mentions is "bi yi niao", it's a mythical pair of birds in Chinese folklore, where the two birds each have one eye and one wing. They can only fly when they're with each other. I can't find the English translated name for this, so I'm using pinyin. Although SIL used a slightly different word in the first line, the meaning is the same. ****The correct phrase should be "连理枝" (lian li zhi). It refers to branches from separate trees (different roots) that have grown and interlocked with each other that it's impossible to separate. It's also known as "husband and wife trees" or "life and death trees". There's nothing called a "连理树" (lian li shu); SIL just mixed up the name here, that's all.

LOOK AT SIL’S HAPPY PROUD FACE AT HIS OWN POETRY SKILLZ

#this was so hard#o.o#word of honor#xiangcao#cao weining#gu xiang#my lack of culture#xiao cao's happy proud face#he's adorbs#i added pinyin for the poetry#to make it easier to spot the differences

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

We at Temper crossed over to the dark side a lifetime ago, though admittedly our “edge” is brimming with red (wine), neon lights and bright eyesight-blasting graffiti. Being the tempestuously temperamental personalities we portray ourselves to be, Temper goes deep with founder of menswear brand Chronic Tiwill Tang as we talk dragon chimneys, conflict and Visual Kei.

ˈ”Color is something used to please the eye and bears within very strong emotional attachments,” Tiwill Tang

Chronic Blacklisted Collection. Courtesy of Chronic

Fun party fact to kick things off: Creative director and designer of menswear brand Chronic, and its current Blacklisted Collection, Tiwill Tang shares his official “pinyin passport” name with one very famous Chinese actress: Tang Wei. Tang, the thespian, in 2008 was blacklisted (i.e. boycotted) by the Mainland’s film industry after starring in Ang Lee’s erotic drama “Lust, Caution” when China’s State Administration of Radio Film and Television at the time demanded that “all local stations cease airing ads starring Tang, including her skin care commercials for cosmetics brand Pond‘s,” local media reported. Party tactics at work, indeed.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Code Black

Blackout, duskiness, eclipse, smokiness, shadiness, and so the thesaurus tags on; all in all, “darkness” invokes a sense of inquisitive mystery with some souls and a feeling of intrusive mortification with others. Nevertheless, the dark in its very nature comes with a special set of inspirational skills. Think of the so-called dragon chimneys which can be found in the ink black oceanic depths of the Pacific, steaming hot water eruptions eerily standing tall and petrified within the blindfolded darkness of their icy cold water surroundings. Eerie yet uplifting in their awesomeness, ever nurturing the creative mind – Chiaroscuro style.

Obscurity and gloom are no strangers to the realm of art, casting inspirational shadows from the worlds of music to photography to poetry and fashion. A quickie pitch:

Black in art: Picasso’s borderline obsessive use of black, white and grey – which came from his claim that color weakens, one with which I dare to disagree – highlights the formal structure and the autonomy of form inherent in his art.

Black in music: Black Sabbath. The use of black across the alternative/goth/punk/grunge mood board as literally donned by Generation X, a classically rebellious peer group who during the 1990s did not want their success to be judged by their property or money. The darkness of the grunge scene and the music in itself appealed to — and became the ultimate reflection of — their communal views. A sense of gloom was emblematic in the late 20th century.

Black in fashion: Marc Jacobs in 1992 became the first designer to bring grunge to the luxury platform and thus the cover of Vogue U.S. — one fashion stint that proved a deeply dark day in the Anna Wintour, Grace Coddington and Linda Evangelista accounts. Never we mind. All cringeworthy grungy looks aside, black conveys a myriad of contradictions, making it a fashion evergreen. Never you mind its slimming effects, black throughout the times has represented the embodiment of contrasting ideas such as “power and elegance, but also humility and submission, especially when worn by priests and others who bear a uniform” — as noted by The StyleCaster.

On a cultural level, too, this hotly debated “color” is susceptible to alternate interpretations. Despite being the epitome of elegance in fashion, black since the dawn of tailored man been the No.1 signifier for mourning in Western culture, the Japanese see black as a hue that represents seniority and experience. What of that Middle Kingdom, then?

Though its shady palette of shadows may not cater to everyone’s taste, the fashionable fortitude of the color black remains undeniable.

Artwork by JiiaKuann. Image courtesy of Tiwill Tang

China Black

Surprising as this may appear to our Western minds, the element of water in Chinese culture is not represented by the color blue, but by its black frenemy. The color black in Chinese culture stands for devastation, malice, disaster, cruelty, grief and suffering; it signifies bad fortune and must by no means ever be worn to positive events such as weddings. The Chinese word for black is ‘hei’ (黑)which stands for bad luck, wrongdoing plus illicitness.

In Beijing Opera terms, the use of a black (well, “monochrome” would be the word) mask means that the character is neutral. Black symbolizes roughness and fierceness, with the black mask either indicating a rough and bold character or an impartial and selfless personality. “Typical of the former are General Zhang Fei with a black cross butterfly face (of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms) and Li Kui (of Water Margin), and of the latter is Bao Gong (alias Bao Zheng), the semi-legendary fearless and impartial judge of the Song Dynasty (907-1279),” and I hereby quote Daphne Lei from her book “Alternative Chinese Opera in the age of globalization”. Yep, we are backing things up with some academic evidence. Well, we picked up a book…

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

As we turn our gaze towards the current China Fashion scene, one immediately notices how black is very much omnipresent. Though its shady palette of shadows may not cater to everyone’s taste, its fashionable fortitude remains undeniable; with Chronic’s latest collection called “Blacklisted” here a prime case in point. Pampering that person — male and female alike — who bears within a broad-ranging personality, a “temperamental character” is essentially that which sums up the Chronic client.

Whereas tempers at times may flare and possible get one blacklisted, the chronic mode fanciers usually have something they are proud of and live life in free and easy fashion. It is their stories you’ll want to read; it is their stories Chronic aims to tell. The Blacklisted Collection presents us with perceptive intuitional forms of materialized Visual Kei — a movement among Japanese musicians, characterized by the use of varying levels of makeup and flamboyant costumes, often coupled with androgynous aesthetics — which are reflected and replaced by a stronger sense of thought and touch. We at Temper for one are intrigued. As the deepest, darkest designer depths bear many a sultry secret, we aim to bring them to the surface: No blackouts allowed as Tang tells all!

Through combining the sense of touch with the element of design, we create a way for people to coexist with themselves in full harmony deep down inside.

The Temper Questions

Temper: Who is Tang Wei, Tiwill Tang, the menswear designer?

Tang: It is I, serving as the head and designer of menswear brand Chronic.

Temper: How important is color to you as a designer?

Tang: Color is something used to please the eye and bears within very strong emotional attachments. In design, then, the choice of color follows the trends at hand. More importantly, the color palette should befit the emotions presented by the staple theme of the overall brand design and specific collections.

Chronic menswear. Courtesy of Tiwill Tang

Temper: About Blacklisted: As a designer, how “dark” are you?

Tang: I think “darkness” reflects a sharp and closed style. It’s somewhat of a contradiction which is in turn represents my personality and suits the emotions hidden deep down inside, in my heart. I try to capture it and present it in the temperament of clothing.

Temper: About Blacklisted: “Perceptive intuitional forms of materialized Visual Kei are reflected and replaced by stronger thinking and touch”. Please elaborate!

Tang: Seeing isn’t believing. Our visual experiences usually possess some type of prejudice and external disturbance. The “blacklisted” theme wants you to close your eyes and see through touch — like the blind. Therefore, feeling something on the inside coming in from the outside, you will find the subtle yet powerful energies people may neglect 99 per cent of the time. Braille is a way for the blind to learn about the world through the sense of touch. When incorporating the element of design into the process, we create a way for people to coexist with themselves. At that very point, people will uncover the most authentic and comfortable way to come into full harmony with themselves deep down inside.

Temper: What and who inspires you?

Tang: The experimental ways of Maison Martin Margiela and the art of Rei Kawakubo.

Temper: How important is “touch” in your design process?

Tang: Clothing functions as mankind’s second skin and the material of which clothes are made thus comes into close contact with our skin. Subsequently, the quality of fabric is very important. When choosing the materials to work with, I usually judge them by touch; with a flair for special and comfortable materials.

Courtesy of Chronic

Temper:What, to you, is the spirit of fashion?

Tang: Inspiration.

Temper: What’s your opinion on the China Fashion scene in 2017?

Tang: With the rise of design in China, there are many challenges to be faced and opportunities to be grasped. China Fashion doesn’t reflect one specific cultural item or event. Instead, it represents the contradiction and conflict between the nation’s previous internalized Eastern philosophical type of thinking and its current notion of a more open yet confusing, conflicted culture. Such contradiction and conflict are the underlying, hidden symbols of my designs.

Temper: What, to you, is the spirit of China Fashion?

Tang: It is changeable and harbors infinite potential.

Temper: What fashion item, according to you, should be forever blacklisted?

Tang: The copied stuff. Blacked out.

“Black is the hardest color in the world to get right — except for grey,” the great Diana Vreeland once ever so nonchalantly stated. Chronic and Tiwill Tang are getting it right; no confusion there.

Contact Tang via email: [email protected]

Follow Tang on Weibo: @TIWILL_China; on Instagram: @tiwilltang_designer

All images come courtesy of Tiwill Tang.

Copyright@Temper Magazine 2017. All rights reserved

Crossing Over To The Dark Side: Chronic's Blacklisted Collection We at Temper crossed over to the dark side a lifetime ago, though admittedly our “edge” is brimming with red (wine), neon lights and bright eyesight-blasting graffiti.

0 notes

Text

诗词 | Poetry

Poems that were not attributed to to being written within a specific year are dated with the lifespan of their writer. If the poet has neither a birth nor death date on record, the dynasty in which they were born will be used instead. All dates are sourced from baidu, 16Jan21 and earlier.

Information on each poem is presented as such:

Poet’s name in pinyin (Poet’s life and death / Dynasty, start and end) | 《Title of collection if any》 Poem title (date it was written, as provided by baidu) - Link to fwoopersongs translation post.

■ Commentary □ Accompanied by images

SHANG - QIN DYNASTY 【1600 - 206 BCE】

Unknown | 《诗经》郑风·子衿 (1000 - 600 BCE) - Shijing: Airs of the State of Zheng · His Collar □

Unknown | 《诗经》国风·郑风·山有扶苏 - Airs of the State of Zheng, Mountains Have Leaning Shrubs ■□

Qu Yuan (340 - 278 BC) |《楚辞》 渔父 - Songs of Chu: The Fisherman ■

HAN DYNASTY 【206 BCE - 220 CE】

Unknown | 白头吟 (202 - 8 BCE, Western Han Dynasty) - lament for a wish ■

Kong Rong (153 - 208) | 临终诗 (208) - last words ■□

THREE KINGDOMS 【220 - 265】

Cao Zhi (192 - 232) | 蝉赋 (220 - 226) - Ode to the Cicada

TANG DYNASTY 【618 - 907】

Wang Wei (699 to 759) | 鹿柴 (742-756) - Deer Villa ■

Wang Wei (699 to 759) | 杂诗三首 (755 - 761) - miscellaneous poems three ■□

Li Bi (722 - 789) | 长歌行·天覆吾 - Long Song (Heaven is above)

Liu Yuxi (772 - 842) | 八月十五日夜玩月 - Frolic ‘neath the moon on Mid-Autumn’s night ■

Zhang Jiuling (678 - 740) | 感遇十二首 (737) - sentiments on the road

Li Bai (701 - 762) | 大堤曲 - Song of the embankments

Li Bai (701 - 762) | 独坐敬亭山 (744) - Sitting alone on Mount. Jingting

Li Bai (701 - 762) | 侠客行 (744) - An Ode to Swordsmen ■□

He Zhizhang (655 - 744) | 回乡偶书·其一 (744) - Homecoming, random scribbles (½) ■

Li Bai (701 - 762) | 将进酒 (752) - An Invitation to Drink ■□

Li Ye (730 - 784) | 八至 - Eight Extremes

Du Fu (712 to 770) | 春望 (757) - The View in Spring

Zhang Wei (Tang Dynasty, 618 - 907) | 同王徵君湘中有怀 (758) - With Master Wang in Xiang Zhong, Speaking My Mind ■

Liu Changqing | 送灵澈上人 (761) - Seeing off Venerable Ling Che □

Du Fu (712 to 770) | 春夜喜雨 (761) - Delight at rain on a Spring night ■

Xu Ning (800s, exact date unknown) | 庐山瀑布 - Mt Lu Waterfall □

Yuan Zhen (779 - 831) | 离思·其四 (809) - Thoughts on Parting (Part 4) ■□

Bai Juyi (772 - 846) | 暮江吟 (822) - Sunset over the river, a song ■□

Bai Juyi (772 - 846) | 问刘十九 (772 - 646) - A question for Mr Liu □

Jia Dao (779 - 843) | 寻隐者不遇 - Failing to Meet the Recluse ■

Wen Tingyun (~812 - 866) | 新添声杨柳枝词 - Newly Added Melody to Willow Branch Lyric ■

Wen Tingyun (~812 - 866) | 商山早行 (859) - Morning Departure from Mount Shang ■□

Unknown (Tang, Zhaozhong period, 867 - 904 ) | 三生石上旧精魂 - An Old Soul On the Stone of Three Lives ■

SONG DYNASTY 【960 - 1279】

Li Yu (937 - 978) | 浪淘沙令·帘外雨潺潺 (978) - Waves Washing the Sand (Ditty) · The Sound of Rain Beyond the Windows ■□

Li Yu (937 - 978) | 虞美人·春花秋月何时了 (978) - Lady Yu · Spring flowers, Autumn moon, oh when will they end? ■

Tang Hui (Southern Song Dynasty, 1127–1279) | 八声甘州·摘青梅荐酒 - Eight Melodies of Ganzhou (Pluck the plums to taste with wine) ■□

Lin Bu (967 - 1028) | 山园小梅二首 - Little Plum Blossoms of the Garden in the Mountain (2) ■□

Wang Qi Song (Song Dynasty, 960 - 1279) | 梅 - Plum Blossom ■

Liu Yong (Northern Song, 984 - 1053) 归朝欢·别岸扁舟三两只 - boats on the opposite shore ■

Qian Weiyan (977 - 1034) | 玉楼春·城上风光莺语乱 (1033 - 1034) - Above the city

Su Shi (1037 -1101) | 江城子·乙卯正月二十日夜记梦 (1075) - River Town Melody · A Dream on the 20th Day of the Second Month in the Year Yimao

Su Shi (1037 -1101) | 明月几时有 (1076) - When will the bright moon appear?

Su Shi (1037 -1101) | 定风波·莫听穿林打叶声 (1082) - Still the Wind and Waves • heed not the sound of rain in the forest

Su Shi (1037 -1101) | 题西林壁 (1084) - Written On this Wall in Xilin ■□

Li Zhiyi (1048 to 1117) | 卜算子·我住长江头 (1102 - 1117) - Song of Divination · I live at the Long River’s head ■□

Li Qingzhao (1084 - 1155) | 如梦令·昨夜雨疏风骤 - Song of a Dream

Li Qingzhao (1084 - 1155) | 一剪梅·红藕香残玉簟秋 - plum blossom cutting · red lotuses linger in remnants of fragrance ■□

Li Qingzhao (1084 - 1155) | 满庭芳·小阁藏春 - The Little Courtyard Hides Spring ■□

Xin Qiji (1140 to 1207) | 青玉案·元夕- Green Jadeite Platter · Fifteenth Day of New Year ■□

Lu You (1125 to 1210) | 己酉元日 (1189) - First Day of Ji-You ■

Lu You (1125 - 1209) | Cat Poetry Collection - Lu You and His Cats □

Shi Xinghai (1224 - ?) | 送清上人归苕溪 - Seeing off Venerable Qing ■

JIN DYNASTY 【1115 - 1234】

Wang Liangchen (? - 1218) | 九月七日饮 - seventh day of the ninth month, drinking □

YUAN DYNASTY 【1271 - 1368】

Wang Mian (1310 - 1359) | 徐竹隐 - Seclusion in the Bamboo Forest

MING DYNASTY 【1368 - 1644】

Li Zhishi (Ming Dynasty, 1368 - 1644) | 为何凝生 题十九首其十二 · 浣月池 - for what were we born 2/19 · Moonwash Pool ■

Wang Guangyang (? - 1379) | 画虎 - Tiger painting

QING DYNASTY 【1644 - 1912】

Nalan Xingde (1655 - 1685) | 长相思·山一程 (1682) - longing for home (a journey)

Kuang Minben (1699 - 1782) | 是非审之于己 (1754 - 1757) - On a couplet from the Yuelu Academy ■□

REPUBLIC OF CHINA【1912 - 1949】& AFTER

Fei Ming (1901 - 1967) | 飞尘 (1936) - the flight of dust motes ■

Dai Wangshu (1905 - 1950) | 在天晴了的时候 (1944) - When the sky is clear and sunny □

Xi Murong (1943 - Present) | 回眸 - Look Back ■□

Unknown | 道别 (unknown) - Saying Goodbye

POETRY THEMED SETS

for childhood nostalgia (the first Chinese poems I ever learnt) ■

ART

南洋景色 (1945, Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee) - Nanyang Scenery

22 notes

·

View notes