#hyolith

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My 25 years of palaeoart chronology...

In 2013 I built 23 scale and life-size models for MUSE Science Museum, in Trento, Italy. Here's an enlarged hyolith (Lophotrochozoa), this one is from the Cambrian.

#Art#Painting#PaleoArt#PalaeoArt#SciArt#SciComm#DigitalArt#Illustration#Dinosaurs#Birds#Reptiles#Palaeontology#Paleontology#Hyolith#Cambrian#JurassicWorld

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cambrian Cuties

I love my friends the Hyolith, the Aysheaia, and Anomalocaris :)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

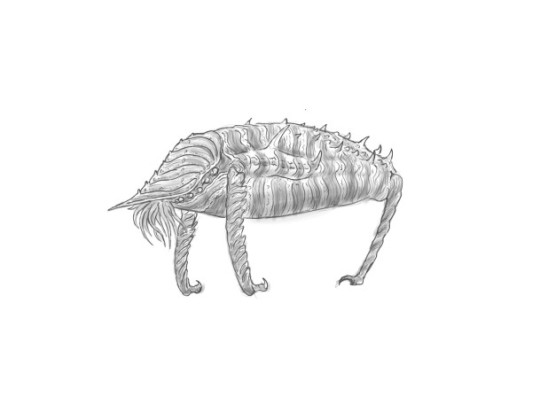

Apologies for the delays! This was meant to be a December post, but it got pushed to early January, so Happy New Year! Cave-Clicker (artwork by Yuujinner)

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: incertae sedis

Class: Hyolitha

Order: Anomalohyolithida

Family: Anomalohyolithidae

Genus: Anomalohyolithes

Species: A. troglodytus (“cave-dwelling unusual hyoid stone”)

Temporal range: unknown to recent (??? - present)

Information:

Relatively new to science, very little is known about this roughly cat-sized creature. The one thing which scientists know definitively is that it is a member of the hyolith clade, albeit one so heavily derived from the ancestral body plan, that it is hardly recognizable as one.

Typically covered in striated black and gray bands with a fleshy pink head, these creatures are seemingly adept at navigating through the canopies of giant fungi found deep below in the caverns, swinging and hopping to get across the difficult terrain. Their diet is not fully understood, but tissue sampling would suggest that they consume small animals in addition to the fungi found in their habitat, possibly filling a generalist omnivore niche, and observed behavior would indicate that they frequently get into scuffles over food, the horn-like projection on their “face” being used to jab at other individuals. Exceptionally social for a non-arthropod invertebrate, these creatures sometimes gather in groups of up to 50 individuals. Its social nature can be dually inferred by its broad set of vocalizations: chittering, squeaking, and clicking (the latter of which gave the creature its name) have all been recorded, though the actual functions of these calls remains unknown. The total population size is unknown, and based on any number of estimates given for the size of the cave system it inhabits, it could be anywhere from simply a few thousand to over half a million. It appears this animal is capable of seeing light in the UV and infrared spectrums, as wild specimens have reacted to such lights in the presence of researchers, whom they appear to be naturally inquisitive towards.

Their reproductive biology and life cycle is unknown, though as they are inferred to be poikilothermic, it is possible that they may live for several decades, maturing at a gruelingly slow pace and mating once or twice throughout their lifetime. Likewise, they are believed to be oviparous, though as no eggs have been found, much less even female specimens (it is known that they have separate sexes, but every specimen captured thus far has been male), there is no way to definitively prove this. The means by which these animals do sexually reproduce also leaves open more questions than it answers: there is no obvious orifice through which they could theoretically deposit sperm, and considering that this creature descends from an aquatic clade, it cannot be ruled out that they do not return to subterranean lakes and rivers to spawn. To further compound this issue, no young of this species have ever been identified, suggesting that they may have simply not been found yet, are indistinguishable from the adult form, or (most likely) that they look so radically different from the adult form, that they may be perceived as a different species entirely. Unfortunately, this is difficult to study in a laboratory setting, in part due to the fact that all captured specimens have been male and in part due to the fact that only 3 specimens have ever been brought to the surface, and within 2 days of being brought the surface, all 3 of them died of unknown causes.

However, the greatest mystery of this creature is not what it doesn’t tell us about its biology, but rather what it does: with a hard, knobby exterior with jagged hooks for feet and horn-like projections coating its “head” and back, this creature shows what appears to be a heavy degree of anti-predator mechanisms. However, for a creature which already has a high degree of protection thanks to a hard yet lightweight outer shell, this begs the question, just what kind of creature could be preying on this animal? So far, scientists have yet to figure that piece out, but terrifying rasping shrieks recorded from deeper in the cave appear to send these animals into a wild frenzy, immediately scattering back up into the canopy. Whatever it is that dwells in the deepest depths, it is clear the cave clickers are terrified of it…

#speculative evolution#fantasy#novella#scifi#scififantasy#speculative biology#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#worldbuilding#creature art#hyolith#sci fi creature#fantasy creature#fantasy worldbuilding#scifi worldbuilding#creature design#creature#sci-fi creature

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

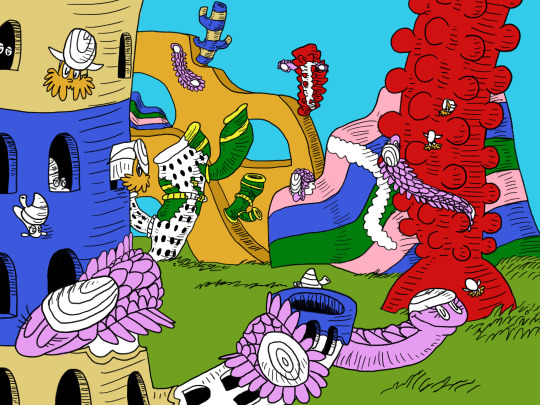

Perspectives paleoart five

"We Do Not Like This, Slugs Who Bug" Australohalkieria, Archaeocyathan sponges, Hyoliths (Turcutheca), Yochelcionella Early Cambrian, 520 mya, Australian sponge reef Out! the Beasts said. You'll ruin our reef! Go take your shell elsewhere, you Cambrian thief! But the mollusks stood steady and kept at their crawl. The Creatures just hoped they would not eat it all. Archaeocyathans were sponges that came in a variety of outlandish shapes and formed reefs much like the coral reefs of today. They may have sustained populations of halkieriids like Australohalkeria above, unfortunately going extinct around the mid-Cambrian. Hyoliths such as Turcutheca might be weird relatives of brachiopods, while Yochelcionella is repping that distinctive shell as one of the first shelled mollusks. This is a part of my Perspectives series! You can find previous entries in #perspectives on my blog.

#yee art#perspectives#paleoart#cambrian#ocean#halkieria#paleozoic#nature art#seuss#palaeoblr#paleoblr#paleontology

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you discovered a new type of animal, which bit of it would you name after your belov-Ed?

(OOC: TIL that there's a type of extinct animal called a hyolith, each of which has a pair of structures called helens - named after the discoverer's wife Helena and daughter Helen. Helens are supports.)

I got too excited before finishing reading this ask and immediately thought about naming any animal Stedicus Bonnicus or something silly so I guess I am not actually a selfless boyfriend because I wanted to name an animal after myself. Anyways, to answer your real question, I would name the cutest part of the animal after Ed.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

L’extinction du Cambrien n’en était pas une | Pour la Science

See on Scoop.it - EntomoNews

Un gisement paléontologique exceptionnellement bien préservé, découvert dans l’Hérault, contredit l’hypothèse d’une extinction massive d’espèces il y a 485 millions d’années.

François Savatier

04 avril 2024| POUR LA SCIENCE N° 558

"À Cabrières, dans l’Hérault, se trouve un rare trésor paléontologique : un lagerstätte floien polaire. Soit un gisement de fossiles préservant la plus grande partie de biodiversité d’un écosystème vieux de quelque 472 millions d’années, que l’équipe de Bertrand Lefebvre, chercheur au CNRS et à l’université Claude-Bernard, à Lyon, vient d’analyser. Or les structures internes des organismes y sont exceptionnellement bien conservées, même quand ils avaient des corps mous ou peu minéralisés, et cela change notre vision de la transition du Cambrien vers l’Ordovicien."

(...)

"... L’apport le plus remarquable de Cabrières consiste toutefois dans la grande moitié d’organismes mous (algues, vers…) ou peu minéralisés (éponges, arthropodes primitifs…), qui ne sont normalement jamais fossilisés."

(...)

[Image] En (a), un trilobite du genre Ampyx. En (b), des gastéropodes associés à une structure tubulaire. En (c), un cnidaire conulariide biominéralisé. En (d) des Brachiopodes articulés attachés à une possible éponge. En (e), assemblage formé de brachiopodes articulés (centre), de carapaces aplaties, probablement d'arthropodes bivalves (centre gauche et droit) et d'un cranidium de trilobite. En (f), un hyolithe avec de possibles organes internes. Les barres d’échelle représentent 4 millimètres en (a) et (e), 1 centimètre en (b) et (d), 5 millimètres en (c), et 2 millimètres en (f)

F. Saleh et al./Nat Ecol Evol

------

NDÉ

L'étude

The Cabrières Biota (France) provides insights into Ordovician polar ecosystems | Nature Ecology & Evolution, 09.02.2024 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-024-02331-w

0 notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion Month #30: Phylum(?) Hyolitha

Hyoliths were a group of small shelled animals that first appeared in the fossil record just after the start of the Cambrian, about 536 million years ago. They had conical calcareous shells with a lid-like operculum, and some species also featured long curling spines that made them look like ice-cream cones with mammoth tusks.

They were so odd that for a long time their evolutionary relationships were unknown. They were generally accepted to be lophotrochozoans, but some studies considered them to be part of their own unique phylum while others tended to place them as being closely related to molluscs.

It wasn't until 2017 that well-preserved soft tissue fossils revealed a tentacled feeding structure that resembled a lophophore – and hyoliths finally found their place in the lophotrochozoan family tree as close relatives of brachiopods and horseshoe worms, possibly even being a stem lineage within the brachiopod phylum.

However, this isn't universally accepted and some recent studies continue to dispute it. The feeding organ of a different hyolith fossil has been interpreted as not being a lophophore, classifying the group as an early lophotrochozoan stem lineage, while an analysis of shell microstructure has instead suggested realigning them with molluscs. I'm grouping them with brachiopods here, but future discoveries might still make this obsolete.

———

Lingulosacculus nuda might represent another possible link between brachiopods and hyoliths.

Discovered in the Mural Formation in Alberta, Canada (~524-522 million years ago), it was about 4cm long (1.6") and had a long conical shell that was either poorly-mineralized or completely unmineralized.

Its position within brachiozoan evolution is uncertain. It was originally proposed as a stem-phoronid, but other analyses place it as a stem-brachiopod, an early linguliform brachiopod related to lingulellotretids, or possibly a stem-hyolith.

———

The earliest true hyoliths were the conical orthothecids, which mostly lived resting on top of the seafloor feeding on organic detritus around themselves. A few have also been found vertically oriented in the sediment, suggesting they may have been filter-feeders collecting particles from surrounding water currents.

Later members of the lineage, the hyolithids, developed distinctive long tusk-like spines on each side of their opercula. These moveable structures have been termed "helens" and were probably used as stilts, holding up the front end of the animal slightly above the seafloor.

There's also some evidence that helens gave hyoliths the ability to move themselves around, albeit probably rather awkwardly. They may have dug out shallow scrape-like "burrows" in the surface of the seafloor to shelter from stronger currents that could overturn them, and clusters of individuals found around carcasses of larger animals indicate they might have been opportunistic scavengers.

Haplophrentis reesei was a typical hyolithid, known from Utah and Idaho, USA, about 509-504 million years ago. A closely related species, Haplophrentis carinatus, is also known from Canada (~508 million years ago) and southwest China (~516-513 million years ago).

Up to about 6cm long (2'4"), this hyolith was one of the first found to preserve soft tissue feeding organs, showing up to 16 tentacles in a lophophore-like arrangement.

———

Whatever they actually were, the hyoliths were highly successful animals for a time, found abundantly worldwide for most of the Cambrian. They later began to decline, but still hung on throughout the rest of the Paleozoic and only finally went completely extinct during the catastrophic "Great Dying" mass extinction at the end of the Permian, about 252 million years ago.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion 2021#hyolith#brachiozoa#lingulosacculus#haplophrentis#brachiopod#lophophorata#lophotrochozoa#spiralia#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#hyoliths converging on corpses is a fascinating idea

99 notes

·

View notes

Link

433 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hyolithes (”the cambrian soldier”)

679 notes

·

View notes

Text

This summer I’m assisting in one of the labs in the geology department

Which means I stare at sand under a microscope for 8-12 hours a week

I see microfossils when I close my eyes now

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ferocious 'penis worms' were the hermit crabs of the ancient seas

These phallus-shaped worms were some of the top predators of the ancient seas, but even they needed protection.

The Cambrian period (543 million to 490 million years ago) brought the first great explosion of biodiversity to Earth, with the ancestors of practically all modern animals first appearing. One of the most feared among them was the penis worm.

Technically known as priapulids — named for Priapus, the well-endowed Greek god of male genitals — penis worms, as they’re commonly known, are a division of marine worms that have survived in the world's oceans for 500 million years.

Their modern descendants live largely unseen in muddy burrows deep underwater, occasionally freaking out fishermen with their floppy, phallus-shaped bodies. But fossils dating back to the early Cambrian show that penis worms were once a scourge of the ancient seas, widely distributed around the world and in possession of extendible, fang-lined mouths that could make a snack out of the poor marine creature that crossed them.

But, fearsome as they were, penis worms themselves were not without fear. In a new study published Nov. 7 in the journal Current Biology, researchers discovered four priapulid fossils that were nestled into the cone-shaped shells of hyoliths, a long-extinct group of marine animals...

Read More: https://www.livescience.com/penis-worms-hermit-shell-behavior

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient oddball invertebrate finds its place on the tree of life

Hyoliths are evolutionary misfits no more.

This class of ancient marine invertebrates has now been firmly pegged as lophophorates, a group whose living members include horseshoe worms and lamp shells, concludes an analysis of more than 1,500 fossils, including preserved soft tissue.

The soft-bodied creatures, encased in conical shells, concealed U-shaped guts and rings of tentacles called lophophores that surrounded their mouths. Fossil analysis suggests that hyoliths used those tentacles and spines, called helens, to trawl the seafloor more than 500 million years ago, researchers report online January 11 in Nature.

For years, paleontologists have argued over where on the tree of life these bottom-feeders belonged. Some scientists thought hyoliths were closely related to mollusks, while others thought the odd-looking creatures deserved a branch all their own. This new insight into hyolith anatomy “settles a long-standing paleontological debate,” the researchers write.

In this hyolith fossil specimen, six tentacles of the lophophore feeding organ (right) and two spines called helens (top and bottom) are visible.

ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM

via sciencenews

1 note

·

View note

Text

The latest episode of paleo after dark is real good and here’s some quotes

“every more recent trilobite you find in the fossil record is one step closer to the end of trilobites, thank god.” [i mean i disagree because i love trilobites but this is a good quote]

"i've been reading a lot about shell beds." "ghWHYYY?"

“we cryptically concentrate bodies”

“they must be molluscs because they're eating the poo”

“nobody knows which way's up on a hyolith”

Oh an since this is my first post about this great podcast, I have to share the BEST quote from it of all time about Lucy the australopithecus:

“Imagine Lucy, T-Posing, coming right at you.”

edit: oh crap there’s a newer episode. those quotes are from the cambrian foodchain episode.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

An article published in the journal "Nature" describes a research on Haplophrentis carinatus and in general of the group of hyoliths, animals that lived during the Cambrian period, starting from about 530 million years ago. A team of researchers from the University of Toronto found evidence that these animals are related to the brachiopods (phylum Brachiopoda), marine invertebrates that existed at the time of which some species still exist today.

0 notes