#hymnstoke

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you think there will ever come a time when you revisit Hymnstoke?

It's possible. Though recently I've been more focused on writing my stories. I stopped Hymnstoke in Act 4, and the biggest hurdle is that I don't know if there's all that much to talk about in Act 5, despite its length. Act 6, though, has a lot going on.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-postmodernism in Pop Culture: Homestuck’s Revenge

I recently saw an excellent video essay titled Why Do Movies Feel So Different Now? by Thomas Flight. Though the title is opaque clickbait, the video is actually about major artistic zeitgeists, or movements, in film history. Flight describes three major movements:

Modernism, encompassing much of classic cinema, in which an earnest belief in universal truths led to straightforward narratives that unironically supported certain values (rationalism, civic duty, democracy, etc.)

Postmodernism, in which disillusionment with the values of modernism led to films that played with cinematic structure, metafiction, and the core language of film, often with more unclear narratives that lacked straightforward resolutions, and that were skeptical or even suspicious of the idea of universal truth

Metamodernism, the current artistic zeitgeist, which takes the structural and metafictional innovations of postmodernism but uses them not to reject meaning, but point to some new kind of meaning or sincerity.

Flight associates metamodernism with the “multiverse” narratives that are popular in contemporary film, both in blockbuster superhero films and Oscar darlings like Everything Everywhere All at Once. He argues that the multiverse conceptually represents a fragmented, metafictional lack of universal truth, but that lack of truth is then subverted with a narrative that ultimately reaffirms universal truth. In short, rather than rejecting postmodernism entirely, metamodernism takes the fragmented rubble of its technique and themes and builds something new out of that fragmentation.

Longtime readers of this blog may find some of these concepts familiar. Indeed, I was talking about them many years ago in my Hymnstoke posts, even using the terms “modernism” and “postmodernism,” though what Flight calls metamodernism I tended to call “post-postmodernism” (another term used for it is New Sincerity). Years before EEAAO, years before Spider-verse, years before the current zeitgeist in pop cultural film and television, there was an avant garde work pioneering all the techniques and themes of metamodernism. A work that took the structural techniques of postmodernism--the ironic detachment, the temporal desynchronization, the metafiction--and used them not to posit a fundamental lack of universal truth but rather imbue a chaotic, maximalist world of cultural detritus with new meaning, new truth, new sincerity. That work was:

Homestuck.

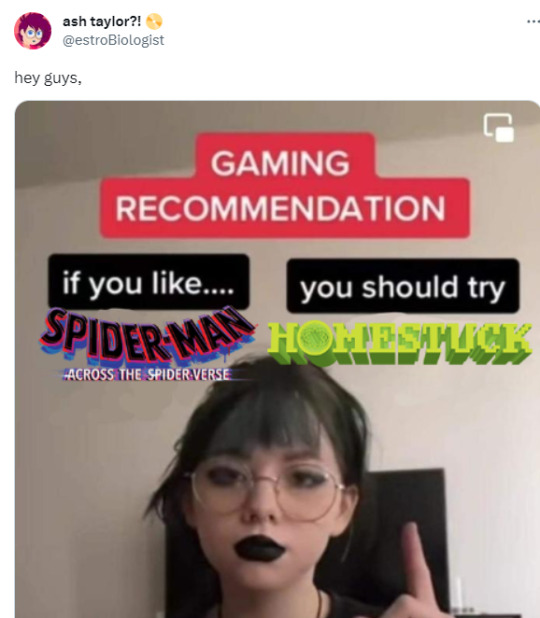

That’s right! Everyone’s favorite web comic. Of course, I’m not the first person to realize the thematic and structural similarities between Homestuck and the current popular trend in film. Just take a look at this tweet someone made yesterday:

This tweet did some numbers.

As you might expect if you’re at all aware of the current cultural feeling toward Homestuck, many of the replies and quotes are incredibly vitriolic over this comparison. Here’s one of my favorites:

It’s actually quite striking how many elements of the new Spider-verse are similar to Homestuck; aspects of doomed timelines, a multiversal network that seems to demand certain structure, and even “mandatory death of parental figure as an impetus for mandated personal growth” are repeated across both works. The recycling and revitalization of ancient, seemingly useless cultural artifacts (in Homestuck’s case, films like Con Air; in Spider-verse, irrelevant gimmick Spider-men from spinoffs past) are also common thematic threads.

As this new post-postmodern or metamodern trend becomes increasingly mainstream, and as time heals all and allows people to look back at Homestuck with more objectivity, I believe there will one day be a rehabilitation of Homestuck’s image. It’ll be seen as an important and influential work, with a place inside the cultural canon. Perhaps, like Infinite Jest, it’ll continue to have some subset of commentators who cannot get past their perception of the people who read the work rather than the work itself even thirty years after its publication, but eventually it’ll be recognized for innovations that precipitated a change in the way people think about stories and their meaning.

Until that day, enjoy eating raw sewage directly from a sewer pipe.

(Side note: I think Umineko no naku koro ni, which was published around the same time as Homestuck and which deals with many similar themes and then-novel ideas, will also one day receive recognition as a masterpiece. Check it out if you haven’t already!)

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

do you know of anything with a similar "clockwork storytelling" style of plot development that you used to described act 5 in hymnstokes?

I'm glad you asked this, because this is a concept I've kept in my mind for a long time.

The most obvious well-known examples of clockwork storytelling that come to mind are the films of Edgar Wright, with Hot Fuzz in particular standing out. Edgar Wright's style is that every detail and line of dialogue, no matter how seemingly inconsequential, comes back later to mean something more than it initially seemed. There is no wasted space, nothing extraneous or unneeded. It is all extremely tight and extremely satisfying to see play out.

Film in general, having significant restraints in terms of length, is often subject to this style, though at differing levels of complexity. What is so exciting about Act 5 of Homestuck is that it manages this style while juggling a zillion different characters and plot threads, so when the pieces all slot together it has the sprawling sense of a symphony with hundreds of individual performers working together at once. But I would argue that even something like, say, most Pixar films follow an ethos of extremely tight plotting with minimal extraneous elements. Pixar operates at a smaller scale, so it doesn't overwhelm with magnitude the way Homestuck does, but it still creates that feeling of satisfaction via structural perfection.

Another good example is Rick & Morty. Dan Harmon is an Edgar Wrightian who has his own personal "hero cycle"-style plot structure he likes to stick to, and that level of plotting is on display in most episodes of the first few seasons of the show. What makes R&M an interesting example, though, is the intrusion of Justin Roiland's influence. Roiland is like, a dumbass stoner whose storytelling ethos seems to be to adlib goofy noises into a mic, which is completely at odds with Harmon, but it complicates the otherwise simplistic story template and wound up creating some of the show's most quotable moments (wubba lubba dub dub).

I like works that fuse intricate and satisfying plotting with bizarre and difficult-to-grasp or even contradictory aesthetic decisions like that. My two favorite anime, Puella Magi Madoka Magica and Blood-C, both fall into that camp, and both times it's due to the utterly opposite aesthetic dispositions of the show's respective directors and writers. Madoka, for instance, balances Gen Urobuchi's tight, almost mathematical plotting (the show has a major plot development nearly every 3 episodes on the dot) with Akiyuki Shinbo's surreal and eccentric visual style. The visuals wind up complicating what would otherwise be a perfectly-composed but possibly quite dry narrative. Blood-C, a less well-known show, similarly combines a rather simple narrative by CLAMP -- where every event and line of dialogue gestures toward a major twist revealed at the end of the show -- with a manic, sleazy gorefiendery from Tsutomu Mizushima, the director of Bludgeoning Angel Dokuro-chan.

When it comes to clockwork narratives at the scale of Homestuck, it's harder to find examples. Of course, Homestuck is itself faking being a clockwork narrative, which I think I talked about in my old Hymnstoke posts. Homestuck's style is to simply toss out so many details that even by calling back to only a third of them it creates the impression via volume alone that it was all planned out and deliberate. A great example is John's toy chest. It contains some items like the Sassacre book that have a recurring purpose in the narrative, some items like the trick handcuffs that have one notable callback use (when John's Dad escapes captivity using them), and some items that only briefly reappear in the background of later panels. It also contains one item, the fake blood capsules, that never show up again (at least John's fake blood capsules don't; there are some fake blood capsules used by Dave's Bro during the whole puppet Saw misadventure). Hussie has only really meaningfully called back to a few of these details, but has created the impression he has called back to a lot of them, because there are simply so many.

In reality, Homestuck, even Act 5 Homestuck, is laden with extraneous and useless details. Most of the trolls are useless, which is why so many of them are glibly killed off. I used to think the only truly important troll to the narrative was Vriska, and by extension any troll that was important to Vriska, such as Terezi. Now, though, I realize that Vriska's breaking-the-game-for-personal-satisfaction shtick was hijacking Rose's whole bit. Rose was constantly seeking ways to break the game or exploit its boundaries. This ultimately culminates in nothing. Rose goes "grimdark," a completely meaningless state that causes her to be goth for a scene or two, and then that's over with and she becomes an essentially ancillary character for the rest of the story, useful only for a few bits of exposition. Even if we ignore the Act 6 part of that, it's a completely pointless set up with no payoff. Rose questioning the game and trying to break it leads nowhere. All the important game breaking is done by Vriska.

I think you could easily do a troll-less rewrite of Homestuck where the only major difference is that Rose is the one who creates Bec Noir instead of Vriska. It's true that the trolls frequently give the kids exposition that guides their actions, but the story has so many sources of exposition -- the sprites, random writing on their planets, Doc Scratch, their own future selves -- that you could easily fill the gaps they leave. That's the other way Hussie fakes a deliberate and satisfying clockwork narrative: redundancy. Hussie can have 100 characters who all "feel" like that have a role because many characters are all basically doing the same thing. I think I once said, in a spiel about database-driven storytelling, that Hussie wrote similar to how he coded. If you ever looked at the HTML of the old MSPA site, I might have been more right than I knew...

This all probably sounds quite harsh on Homestuck, but I think even creating this illusion of unity at such a large scale is impressive. Compare to a lot of the long-running shounen, which accumulate hundreds of characters who are relevant for their introductory arc and then become part of an increasingly gigantic crowd of tagalongs who are lucky if they even get to say a line now and then to remind the audience they exist. Hussie used the (at the time) brand new concept of the "meme" to accomplish a lot of this aesthetic clockworkery. The most common callbacks in Homestuck, after all, are repeated lines from Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff. The redundancy in characters and details helped the work's internal meme language because memes tend to disperse by being templatized and reused in a variety of similar-but-different contexts. In a normal story, you might see stairs several times, and not think anything of it. But in Homestuck, the concept of "stairs" is memetically meaningful. If stairs show up, you better be sure you'll soon get a memetic callback. A bunny? There's a bunny? Oh shit. You better put it back in the box. In this paradigm, a character being similar to another character, almost to the point of redundancy (i.e. Dave and Davesprite and Dirk), is aesthetically unifying, rather than pointlessly promulgating.

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just binge'd your Hymnstoke series. Now that HS^2 (HS^BC) is back up and running with James Roach at the helm, I was wondering if you could share your thoughts on the direction that HS^2 and Homestuck Beyond Canon are taking with the new updates?

Before I begin, I'll point you to a previous post I made on the topic of HS^2, back when it was under the previous management.

Truthfully, I still haven't read HS^2, either the old version or the new. I remain uninterested in it conceptually. For me, the Epilogues were the perfect finale to Homestuck and I no longer have any desire to see its story continued or its characters expanded upon.

I think I'm somewhat mismatched with the typical fans of Homestuck. From talking to fans, it seems many of them started reading as teenagers, who found in its something relatable and became invested in the journey of its characters. I wasn't like that. I began reading Homestuck in college. I was not introduced to it via fandom osmosis or seeing art of it or cosplays or so on. I didn't even learn of it from word-of-mouth from one of my friends. I was reading a post someone had made about so-called ergodic literature, which cited House of Leaves and Homestuck as examples. Having read House of Leaves only a few weeks prior, I was intrigued and looked up Homestuck, going into it almost as blind as possible.

As Hymnstoke probably indicates, my interest in Homestuck was literary from the start, and what impressed me most about it was always its boundary-pushing approach to medium and narrative. Even late into Act 6, past the point where most fans might say the story "gets bad" or whatever, Hussie was always, always concerned with that, and that is why I actually prefer Act 6 to Act 5 despite this being a fairly controversial take. I think in Act 6 Hussie is far more experimental, far more willing to take artistic risks and pursue innovative formal exercises. So, even as more traditional markers of narrative quality like character and plot stagnant, meander, or suffer altogether, Homestuck to me always felt like it was still growing in new and exciting directions.

At least until the series of super long pauses that ended with the whimpering and frankly pathetic Collide + Act 7 combo, two tragically substanceless flashes that really add nothing new or unexpected whatsoever.

The Epilogues, however, were a return to form on the formal front. The competing Meat and Candy narratives, though told in arguably Homestuck's most traditional format yet (prose narrative), are intertwined in ways that push even this ancient medium to new, unseen limits. In that sense, even ignoring all the plot/character stuff I mentioned in my previous HS^2 post, the Epilogues were a culmination of all Homestuck meant for me. A thematic capstone: A return to a traditional format that is then enlivened through daring experimentation. My Hymnstoke series often mentioned the theme of the meteors wiping out Earth so that a new society could be created out of recycled detritus from the old and stagnant world. The Epilogues are that simply in how they are made, and to me that is peak Homestuck, the chief thing that matters most about it.

HS^2 has not seemed interested in formal experimentation at all. The pre-Roach group was mindbogglingly retrograde in eschewing flashes altogether and even, really, art, preferring instead long script-style dialogues. Long pesterlogs were part of Homestuck before, but far from the only part. But there simply seemed to be zero interest in innovation, in doing anything new, in even trying anything new. To me, that's not Homestuck.

I'm not super keyed into the fandom drama, but my understanding is that the old HS^2 group was nasty and combative with the fans, while Roach has attempted to establish goodwill in the fans and repair some of the burned bridges from yesteryear. To that end, his approach seems to be succeeding. But there's a part of me that sees it as being similar to the Star Wars prequels and sequels. The prequels were an unmitigated trainwreck that the fans despised; the sequels, by contrast, began with a soft remake of New Hope that seemed tailored to tell fans "Look! Star Wars is Star Wars again! We're back! It's real! We have practical effects, and on-location filming instead of green screens, and the plot is straightforward instead of trade dispute politics!" It was like JJ Abrams watched the infamous Plinkett review of the prequels and decided to address everything directly, all to reestablish goodwill with fans.

For Episode VII, it worked. Perhaps if the rest of the trilogy were 1-to-1 soft remakes of the original trilogy, it would have continued to work. But the instant the new creators attempted any kind of innovation in the criminally underrated and over-hated Episode VIII, they were raked over the coals, and in the process of backtracking furiously wound up creating something on the same level as the prequels with Episode IX. And nobody was happy in the end.

In the position Roach is in, he can at best muster the kind of nostalgia-baiting soft remake that is so popular and common in Hollywood today, a Homestuck 2.0 rather than a Homestuck^2, something that is not in fact Beyond Canon but enslaved by it. By appealing to the goodwill of fans that's what you have to do, because what the fans love is the ghost of the story they remember, and the reason they come to Homestuck^2 over any of the endless amount of content online is because it has the name Homestuck in it, and they remember Homestuck. Waiter, I'm the critic from Ratatouille, bring me the thing I remember.

But that is conceptually antithetical to the thing I remember. And so, it'll be difficult for it to engender much interest in me. I think there are a lot of exciting, talented creators making amazing original content online today, new boundary-pushing content, a new avant garde, and that's where my interest will lie. I think the members of the Homestuck fandom who had the talent to create content like that, like Toby Fox and perhaps Tamsyn Muir (who I have not read but Gideon the Ninth is certainly popular so it must have some spark to it), have gone ahead and done it for their own original works outside the Homestuck label.

Anyway, those are my rambling thoughts on the matter, again without having actually read either the old or new HS^2, so take them with a grain of salt.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymnstoke Intermission

Andrew Hussie had the courtesy to drop some thoughts on the Epilogues, the full text of which can be found here. As you can probably tell, it’s dense, so I’ll summarize what I consider the key points.

1. Hussie intended the Epilogues to be “conceptually distinct” from the main narrative of Homestuck (i.e., Acts 1 through 7).

2. Hussie intended the Epilogues to set new narrative stakes and establish a way for the narrative to continue (as opposed to the traditional idea of an “Epilogue” as something that resolves what came before).

3. By labeling the Epilogues as “Epilogues” while not adhering to traditional expectations of what an epilogue entails, Hussie intended to prompt readers to question storytelling concepts and the agenda of the storyteller.

4. Hussie intended to cede his authorial control over the Homestuck story and “pass the torch” to the fandom.

5. Hussie intended to prompt the fandom to develop skills like “critical discussion, dealing constructively with negative feelings resulting from the media they consume, interacting with each other in more meaningful ways, and trying to understand different points of view outside of the factions within fandom that can become very hardened over time.”

I actually disagree with several of Hussie’s conclusions, which probably sounds hilariously presumptuous. But if Hussie truly wants the fandom to develop skills in critical discussion, and to foster and understand different viewpoints, while also ceding his authorial control over the work, then his word being “Word of God” has to be called into question. Act 6 of Homestuck already does this; Hussie’s author avatar is literally killed followed by a flash titled DOTA. DOTA, of course, being short for “Death of the Author,” a frequently-cited essay by Roland Barthes that argues that author's intentions can neither be wholly known nor taken as the sole interpretation of a work.

It’s arguable whether Hussie’s shout out to this essay is meant to be an endorsement of its thesis, and I think a claim could be made that the DOTA in Homestuck is inherently parodic; Hussie’s author avatar continues to exist and influence the story even after his “death,” and at times (such as the Meenah walkarounds) the author avatar appears to give direct statements of the author’s intentions behind certain creative decisions. In fact, the DOTA flash itself marks one of the Hussie avatar’s most direct interactions with the story, as it is during this flash that he gives Vriska the Ring of Life.

Even now, Hussie’s actions contradict his claims, at least to some extent; he cedes narrative control and promotes differing critical interpretations at the same time he dumps a tremendous block of text explaining the intentions and goals of his work. An author’s statement on “what the story means” usually affirms his or her control and quashes differing viewpoints, after all. But it’s not something new. Homestuck has always blurred the line behind author and fan. Some of Hussie’s statements I don’t take as major revelations but rather reiterations of themes that have been clear since Act 1.

If you have read my more recent Hymnstoke posts, you can probably guess which of Hussie’s points I disagree with. In particular, I think the Epilogues are too thematically important to Homestuck to be treated with the kind of “take it or leave it”/“canon or non-canon” ambivalence Hussie claims in his post. Or maybe it’s more that I wish it didn’t have that kind of ambivalence? Because his logic is sound; the Epilogues are presented in a way that sets them apart from “Homestuck Proper.” The AO3 fan fiction cover page, the prose, the way they’re organized as a distinct entity on the website, all of these elements contribute to and support Hussie’s claim of separation. Perhaps, then, my counterargument is that the Epilogues shouldn’t have been displayed this way; that they should have been a fundamental part of the story, one that is unquestionably considered “canon.”

Without the Epilogues, the ending of Homestuck is bad. Really bad. Game of Thrones bad. The original ending of Homestuck fails Homestuck on every conceivable level. It’s a poor resolution of the plot, as it relies on a deus ex machina (Alt!Calliope) while leaving tons of smaller narrative elements completely unresolved. It’s a poor resolution of the characters, as most of them wind up being irrelevant (even those given absurd amounts of screen time, like Jake) and their personal issues are resolved off-screen during a timeskip. It’s a poor resolution of the themes, as despite constant statements that one can’t cheat their way to “development,” that is exactly what happens when Vriska is revived and fixes everyone’s problems instantly. It’s a poor resolution of the structure or form, as what was a tightly-wound machine narrative that relied on innumerable tiny parts sliding into perfect order ended with a big dumb fight scene where people just whap each other over and over until the good guys whap hard enough to win. Beyond the fact that the ending is “happy,” I still can’t find much good to say about it even after years of turning it over in my head.

And during the hiatus-strewn period that marked Homestuck’s end, Hussie was noticeably scant on dropping essays about his intentions.

The Epilogues redeem so much of what went wrong with the ending of Homestuck. I won’t delve into the specifics in this post, as I should probably save it for a more comprehensive series of posts about the Epilogues. But from that perspective, it feels to me as though the Epilogues should not be divorced from Homestuck so thoroughly.

But see, my disagreement with Hussie on this point is a bit disingenuous for another reason. Because, like his claims of ceding authorial control, he’s contradictory here too. Consider these points:

1. Hussie intended the Epilogues to be the launching point of future story developments.

2. Hussie, ceding his own control, intended these future developments to be created by the fans.

3. Hussie designed the Epilogues so that the fans could accept or deny them outright, consider them “canon” or “non-canon.”

If the Epilogues are the breeding ground for Homestuck’s future, then that part of the fandom that denies them renders themselves inert. Without the Epilogues, Homestuck is over. It’s done. The window of our Pynchonian party is closed. All life has petered out; no energy enters to sustain it. The Epilogues open the window. Denying the Epilogues kills the story, and thus the fandom; accepting them leaves room open for the future. And if the part of the fandom that rejects the Epilogues withers and dies, that means only the fandom that accepts them will remain. Ultimately, the Epilogues will be considered canon by the Homestuck fandom, because those who disagree will no longer be part of the fandom, at least the active one.

That probably sounds imperious. But it’s not something I want; the people who deny the Epilogues ought to have a voice as well, and nobody is stopping them from providing their opinions. But I have a hard time imagining that people who deny the Epilogues will stick around in a fandom for a work now defined by the Epilogues. As such, many of Hussie’s conciliatory claims fall flat or seem overly idealistic. Can the fandom continue as a divided house on such a fundamental line when future developments to the Homestuck story will be based on the Epilogues? The canonical arguments for which books belonged in the Bible did not end in blithe harmony; one viewpoint prevailed and all schismatics extinguished. Obviously there will be no burnings at the stake over Homestuck canon, but in a world where there are so many options for entertainment, those who do not accept Homestuck’s active element will probably leave of their own volition.

There's also a third option, expressed by one of the commentators on the Reddit thread I link at the beginning of this post.

Here's my suggestion for you, Hussman. Big subversion, you'll like it: Make "Homestuck 2" and then not have anything form [sic] Homestuck in it at all and just make the story you actually want to make.

The Homestuck fandom might die, but the “Hussie” fandom will survive, as long as Hussie himself continues to create art. Before the Epilogues, I often expressed a similar sentiment. I wanted Hussie to get away from Homestuck, make something new, even if it was just something short and far less ambitious than Homestuck. I think Hussie is a strong storyteller and writer in his own right, and he did not merely “get lucky” with Homestuck the way a hack gets lucky when their trashily-written novel strikes a perfect chord with the culture and sells millions. If Hussie does actually intend to cede authorial control and leave Homestuck to the fandom, then what is his next move? Retirement at 40? I hope not.

Those were my hastily-written thoughts on Hussie’s commentary. While at times contradictory, I consider Hussie’s claims and actions in line with themes established throughout Homestuck. But I also question whether his storytelling decisions will be able to achieve the result he desires for the fandom.

Whether he or we can achieve it, I do agree with Hussie’s hope to create a fandom that is smarter, more willing to view the work with a critical lens, to discuss with one another, to understand each other’s viewpoints, to deal with difficult subject matter. I think a lot of people can be scared to delve deeply into a work, either because they only want their entertainment to be light escapism or because they feel gatekept by not knowing a lot about literary criticism as a field of study. Maybe escapism is fine, but it’s not the only use of art. Treat the stories you like as art and really ask yourself what you like about them, what makes them good, and especially what it means that those things make it good. Those questions will serve a fitting substitute for an understanding of postmodern literary trends of the 20th century.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymnstoke XIII

Have you heard the story of bladekindEyewear the Blind?

In infinite folly, this man strapped knives to his eyeballs, depriving himself of sight. Nonetheless he was known as the wisest man in Homestuck Tumblr, with a wicked pack of classpect analyses. As Homestuck progressed through its lengthy sixth act, he developed a wide sleight of theories as to how it would end and what it would mean when it ended that way, focused most famously on each character's SBURB class and aspect (classpect for portmanteau).

When Homestuck ended, and then ended a second time, he turned out to be wrong.

In a recent post, he made this comment about his wrongness:

BlastYoBoots 04/26/2019: part of why all my theories were wrong is that they were arrogant and misguided and just all-around regrettable and I thought I "knew" what Andrew morally wanted out of a story when he wasn't after the same thing at all

I bring this tale to your attention not to drag our Sosostris through the mud. In fact, I'd say he's unduly harsh on himself here. He may indeed have had a decent grasp of Hussie's moral purposes regarding Homestuck—in 2013. It has been a long six years since then, during which Hussie followed in the footsteps of other noted New England authors J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon and vanished off the face of the planet. It would be fair to theorize that what Hussie "wanted" out of Homestuck changed considerably in those years. And the truth is, because Hussie has disappeared so utterly, any illusion of knowing his "moral" goals has completely dissipated. It's not even clear at this point how much of the Epilogues he wrote. What statements can possibly be made about authorial intent outside of baseless conjecture?

Mr. Eyewear had the unfortunate position of writing critical analysis of a work that was not yet finished, a position not often imitated by critics throughout the ages. It's relatively easy to look at a work by a long-dead author and make some grand, sweeping statement that "this is what it means." Because the author is literally dead, Death of the Author becomes much less controversial to apply. Even now, after the dust has settled, a new installment of Homestuck may unexpectedly arrive that obliterates any previous critical insight on what Homestuck "meant." Homestuck is ostensibly over, but the Epilogues left plenty of room for continuation.

Someone who read the previous Hymnstoke installments came to me and said (paraphrased), "Do you really think Hussie knows anything about Gnosticism? It's far more likely he googled it and used a few names here and there to sound smart." Thinking about it, I wouldn't be surprised if this turned out to be his modus operandi for the Pale Fire and Waste Land quotes I wrote so lengthily on in previous Hymnstokes as well. Wouldn't it make so much sense if Hussie googled "Literary quotes about April" and put in the Waste Land quote without ever having read the poem, without understanding its historical or literary context?

Would it matter?

Hussie may or may not be ignorant of literary history, or his own literary moment. In that Stanford interview he flatly denied any knowledge of "post-irony." But the author's ignorance doesn't excuse the work from the world. Homestuck itself is rapidly becoming a historical work, fading from the immediate cultural consciousness. Yet it has left a mark. How many works will be created in the coming years that draw heavy inspiration from Undertale, which itself was heavily inspired by Homestuck? And if we take Homestuck's most explicit inspiration to be Earthbound, what works inspired Earthbound? What works inspired the works that inspired Earthbound?

Whether Hussie knows what DFW stands for or not is inconsequential. Homestuck is not a work in a vacuum, neither the beginning nor the end. Con Air, the Greek Zodiac, Insane Clown Posse—whether the reader knows what those things are doesn't matter within the space of Homestuck, because Homestuck invented new meaning out of them all. Whether Hussie, the author, knew what Gnosticism, post-postmodernism, or Dadaism were—I would argue that is similarly inconsequential. Homestuck repurposed all of those -isms, either knowingly or unknowingly, into something new. It is the act of repurposing that is the most important part, not whatever those things were before.

So bladekindEyewear observed Homestuck through the lenses of knives strapped to his eyes. From that perspective, he conceived of what the facts (the text of Homestuck) "meant." I'll also be looking at Homestuck through a certain lens. Neither lens is the same as Hussie's lens. No lens except Hussie's can be Hussie's lens: that is something the postmodernists realized, that "truth" was fragmentary and differed from person to person. Perhaps even different within each person; the Hussie of 2013 may have a different lens than the Hussie of 2019. Put succinctly: No absolute truth exists.

But Homestuck, I feel, moves beyond the problems proposed by postmodernism. In Homestuck, differing lenses, even completely opposite lenses like "irony" and "sincerity," "science" and "magic," "time" and "space," or "author" and "reader" (as seen in the Epilogues) become blurred, indistinguishable, ultimately reconciled as essentially the same thing. It's that reconciliation that I think is Homestuck's most meaty—or candiey—thematic component.

With that in mind, let's continue.

What is under the rug is much worse than any trap you can imagine.

It is a member of a species that you do not recognize, with a ghastly furred upper lip.

I don't even know who this is. Jeff Foxworthy? I guess I might not be a redneck.

Soon these lugs will learn to show you some respect. You made this town what it is after all. Wasn't nothin' but a bunch of dust and rocks before you got here.

Okay. I was right. I knew it, all along when I was reading the Epilogues I knew something was off. I felt certain, and now it's been confirmed for me.

Homestuck does not use smart apostrophes, while the Epilogues did.

For those not in the know, a smart apostrophe is curved based on the text that comes around it, like so: ’

A regular apostrophe, by comparison, is not curved: '

As you can see in the quoted text, Homestuck proper uses your regular dumb apostrophes. Which is good, because smart apostrophes are the devil. They frequently get slanted the wrong direction and conflict aesthetically with Homestuck's monospaced, geometric Courier font. Yet all throughout the Epilogues, smart apostrophes are used. It drove me insane. I hate those things.

Can't overthink this time stuff.

I guess I should actually talk about the Intermission. Internally, it's pretty straightforward, borrowing liberally from Problem Sleuth. But what exactly is its purpose? Yes, on a purely plot level, elements of the Intermission return in Act 5. Spades Slick remains a character who exists all the way until Collide, although he is one of the unfortunate casualties of Act 6's awful ending and is too dead to get any kind of relevancy redemption in the Epilogues, unlike similarly extraneous Act 6 characters Jane and Jake.

Fundamentally, then, the relevance of the Intermission extends only as far as Cascade, with elements malingering longer but never amounting to anything new. Many things will extend only as far as Cascade, which eventually becomes Homestuck's midpoint. In earlier Hymnstokes, I mentioned a few times that I didn't think I had much to say about Act 5. I said that because, while Act 5 is impressive from a technical standpoint, it's a lot less dense in meaning compared to early Homestuck or Act 6. It functions a lot like a machine with many perfectly-placed parts (or rather, parts that were retroactively made to look perfectly placed, depending on how improvisational you think Hussie wrote) that slot together like a machine, rifle, or clock to create a flawless cascade of storytelling. I'll talk more about this kind of "clockwork storytelling" when I actually get to Act 5, but for now one might consider the entire Intermission to be one of those perfectly-placed pieces, and the Spades Slick storyline culminates in Cascade to slot alongside the other pieces in a satisfying way.

One might also interpret the Intermission as a primer for certain elements that will become important in Homestuck proper, such as the aforementioned "time stuff" that gets its first real exploration here before becoming a convoluted but finely-wrought entanglement in Acts 4 and 5. Toss in vague foreshadowing to Lord English and the Intermission's existence is at least purposeful, regardless of whether one considers it necessary.

But what about structurally? I mentioned in the previous Hymnstoke that the Intermission is similar to Act 5 Act 1 and Act 6 Act 1 in that it dramatically downscales the tension, introduces a slew of new characters, and shakes up the tone of the story. Each of these three parts are nostalgic for "Old Homestuck," the Homestuck that is more like Problem Sleuth, and they feature many text commands and faffery like what you see in Act 1. By juxtaposition, then, each emphasizes how far Homestuck has developed across its run, and the differences only become more striking each successive iteration.

The Intermission is probably the fragmenting point. In Homestuck proper, there are no more kids to introduce. John, Rose, Dave, Jade, for each of them we've cycled through the database-structured INTERESTS and INSTRUMENTS and WEIRD PARENTAL FIGURES. Bit by bit that kind of content will vanish in favor of a new sort of storytelling, and the Intermission is where it becomes obvious that this is happening. Jade's introduction already subverted most of the established tropes, and the Intermission reads like a parody of them, with the Midnight Crew's set of traits being plaintively ridiculous (each keeping a different kind of candy in their backup hat, each having a different kind of smutty material, et cetera). Act 5 Act 1 will also be parodic in its approach to these database traits, but I think in a less effective way, as the differences between the kids and the trolls are less extreme than the differences between the kids and the Midnight Crew. Furthermore, the Intermission really drives the nail into the coffin of Problem Sleuth, severing Homestuck finally from its predecessor. Act 6 Act 1, by comparison, is more of a wistful yearning for Act 1 than any kind of new take—which might itself be meaningful in the grand scheme of things.

Still, it might come in handy down the road. Lord English is supposedly indestructible. He's rumored to be killable only through a number of glitches and exploits in spacetime. The doll may ultimately help you work the system if it comes to that.

This line, along with the way Problem Sleuth ended, was probably the primary driver that led to people expecting a final boss fight with Lord English on par with the one with Mobster Kingpin. Although the Epilogues were a fantastic ending, it's still underwhelming to think about just how poorly-conceived Collide and Act 7 turned out to be. Of course, the Problem Sleuth sort of ending is definitely more of a "clockwork" storytelling style, and Act 6, as has become clear by now, has a much different style.

Dirk, the ultimate inheritor of the clockwork style—he specifically describes storytelling in terms of machines—has as one of his INTERESTS robotics and technology. Lord English, likewise, is surrounded by a clockwork motif. Of course, these characters will eventually become explicitly linked via the method of Lord English's creation. But unlike many other INTERESTS, which turn out to be irrelevant, this machinery fascination ties in to Homestuck's final thematic dichotomy. But more on that when we reach the Epilogues.

29/1000 CLOCKS DESTROYED

I guess we know what side of the dichotomy Spades is on.

This is the same calendar Dirk has in his apartment in Act 6. I remember I once had this theory that the Midnight Crew would be reunited at the end of Homestuck even though the B2 Hegemonic Brute was dead because it would be revealed that Hearts Boxcars was still in Dirk's calendar and would come out riding Dirk's mini Maplehoof.

I don't know why I had this oddly specific theory, and it was probably obvious it wouldn't happen.

And thus ends the intermission, with an eye toward the next bizarre deviation in the storyline (Act 5 Act 1).

It's been awhile since I last read Homestuck. My memory of Act 4 is dodgy, so I might actually stumble upon something new. But as I mentioned earlier, the Intermission is the big, obvious breakpoint between the old, Problem Sleuth style of Homestuck and the new, clockwork style. The database-driven character creation will gradually fall away (minus a parodic revival in Act 5 Act 1) and narrative elements will become more consistently introduced with an eye specifically toward Cascade. For many people, this is when Homestuck starts to "get good," and I think it's because there's something innately satisfying about a finely-crafted machine slotting into place. There is a kind of intrinsic beauty about it, art for art's sake if you will, and that is also what seems to draw Dirk toward it.

But more next time.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymnstoke XV

GC: TH3Y 4LL THOUGHT 1 W4S CR4ZY GC: BUT H4H4H4 1T TURN3D OUT W3 4LL W3R3 1N OUR OWN W4YS GC: TH4T H3LP3D US R34LIZ3 TH3 P4RTICUL4R D3ST1N13S THE G4M3 PUT TOG3TH3R FOR US GC: 1N TH3 VOC4BUL4RY OF L1K3 GC: TH3 HYP3R FL3XIBL3 MYTHOLOGY 1T T41LORS TO 34CH PL4Y3R GROUP

Bildungsroman.

I think the term "bildungsroman" (or its less-pedantic equivalent "coming of age story") is over-employed in contemporary critical analysis. It's a lot like the term "deconstruction," which can be draped atop a wide variety of stories to ostensibly make a critical statement without saying anything.

Hussie himself, in one of his old Formspring posts, described Homestuck as a "coming of age story." But who exactly is the one coming of age? Obvious answer is John. The story opens with him on the cusp of adolescence (thirteenth birthday) and ends, at least in one Epilogue, with him reconciling with his estranged wife and child. Obviously some coming-of-age has occurred, even if only literally. But in what way has John developed as a person? Is that development stymied by the existence of a parallel Epilogue in which he unceremoniously dies, or does even that branch of John's existence feed into who John becomes as a person?

I've only read the Epilogues once, so my thoughts on that part of the story probably won't be fully realized until I reread them at the end of this blog. Rooting myself purely in the current moment of Act 4, however, I can still discuss certain aspects of John as a character. I mentioned in previous Hymnstokes his beginning as a naïve, blank slate reader-surrogate who blindly fumbles his way through uncertain situations. His trajectory has been away from this initial naivete toward cynicism—or "irony" if you will—a more cautious, guarded approach to his understanding of the world around him. The main moment of development so far has been his foray into his Dad's room, which revealed to him that his Dad "isn't all that into clowns you guess." But I don't think it's until John's interactions with Vriska in Act 5 Act 2 that he's going to reach the done-with-this-shit, rolling-my-eyes attitude he possesses throughout Act 6. (And it's funny, because even when he takes on that attitude, he still serves as reader surrogate—as if the reader, too, sees what was once novel and wonderful as obnoxious and stupid—but that's for a discussion of Act 6 as a whole.) So that's John's coming-of-age "arc."

Which feeds into a larger discussion about duality, because as I mentioned previously Dave is moving in the opposite trajectory, away from irony and toward sincerity. Rose is moving away from scientific analysis and toward occult spiritualism, while Jade—well, Jade never really gets a "character arc" because she's more of a plot device than a real character. But Jade, functionally, begins as a spiritual prognosticator whose seemingly supernatural facets all eventually become explained by rudimentary technical features of the SBURB game.

The reason why I think describing Homestuck as a "coming of age story" is reductive is because while these young characters do develop (or at least change), these developments crisscross one another, lead to innumerable dead ends, and fail to satisfy the characters themselves. I would argue that almost all of the characters are more insecure, or even more immature, at the end of Homestuck than at its beginning. The thirteen-year-old versions of these characters speak with the vocabulary and understanding of a reasonably well-read 30-something dude, employing witty barbs and clever sentence constructions left and right as they empirically sort out the unfamiliar game world of SBURB to satisfactory results. They have "problems" with their parental figures, they don't "understand" themselves, but they are competent people capable of progressing despite immense challenges hurled their direction. The major failures of the B1 SBURB session are caused by the meddling of the trolls, not imperfections in John, Dave, Rose, or Jade. In fact, the kids' concerted, Herculean efforts to create a clockwork Cascade of perfectly-placed mechanisms are what salvage an otherwise hopeless situation.

Yet in B2 it all goes to shit, and John and pals wind up being totally useless despite having far more advantages than they did in the B1 session: three years to prepare, foreknowledge of the game's mechanics and even the specific situation of the B2 SBURB they are entering, being literal gods, retcon powers, et cetera. It's almost as if, rather than "coming of age" and "developing into adults," the kids undevelop, unmature, regress, fall apart, decay...

Kind of like entropy.

So if the characters themselves are progressing in these crisscrossing dualisms, irony versus sincerity, science versus faith, then the development of the characters as a whole is crisscrossing the development of the plot: Degeneration versus regeneration, destruction versus creation. In a way, these characters are relics of the world they left behind: that saturated, useless Earth. They are products of its cultural detritus, and while their aim is to create a world from its fragments, they themselves are among those fragments. In the Epilogues, their intrusion into the world they created hurls that world into chaos, and the Meat epilogue ends with them extracting themselves from a place in which they do not belong.

GC: 4CT1ONS TH4T COMPL3T3 LOOPS 1N TH3 T1M3L1NE GC: COGS 1N P4R4DOX SP4C3 TT: Paradox space? GC: OH H3LL GC: L1ST3N TH3 UN1V3RS3 W1LL 34T P4R4DOX3S FOR BR34KF4ST GC: 4ND SO W1LL TH1S G4M3 GC: G3T US3D TO 1T GC: BY NOW YOU SHOULD R34L1Z3 TH1S WHOL3 M3SS W4S 4 B1G S3LF FULLF1LL1NG CLUST3RFUCK GC: A HUG3 ORG14ST1C MOB1US DOUBL3 R34CH4ROUND

Or are the linear tracks of character development I described actually part of Homestuck's favorite structure, the mobius loop? Is the duality between irony and sincerity, science and magic not actually a duality, but two sides of the same one-sided shape?

Because the path of Homestuck might also be read not as a linear rise and fall, but a series of loops. John and pals degenerate in early Act 6, only to renew again after GAME OVER when Vriska sorts everything out and they have a huge pow-wow before the final fight. Yet they degenerate again in Epilogues, falling apart at times even more pathetically than they did on the three-year plane ride to the B2 session, only to finally reach a semblance of resolution at the end of either one Epilogue or the other. But even the ends of those Epilogues suggest a lack of finality, a way for the story to continue, more development upward or downward to be had.

A series of Ascents and Descents. It fits the naming structure employed for many key moments in Homestuck. But what does it mean? Why does it matter that Homestuck is structured this way?

Thomas Pynchon, that nefarious postmodernist, was a writer overtly concerned with entropy, given his background in science and engineering. He once wrote a short story about another one of his favorite interests: parties, bro. In this story, a group of young people are partying in a house. Having fun, drinking, all that young kid stuff. But as the night draws to an end, the energy disperses, everyone becomes tired and lazes about. The closed system of the party has succumbed to entropy. At the end of the story, someone opens a window and a breath of fresh air revives everyone so that the party can continue.

On a universal level, entropy is irrevocable. Eventually, millions or billions of years in the future, heat will disperse throughout the universe; no more stars, no more solar systems, only a cold expanse of space. But in a closed system, entropy can be easily overcome by opening the system and letting in energy from outside, the way it worked in Pynchon's party story.

In an earlier Hymnstoke, I exuberantly declared that Homestuck overcomes entropy. My argument was that, by making meaning out of meaningless cultural detritus, Homestuck resolves the problem of societal decay famously put forward by T.S. Eliot in the poem The Waste Land. That conclusion may have been overeager, especially in light of how Homestuck ends both in Act 7 and the Epilogues. But I think viewing Homestuck through this post- or post-postmodern lens of entropic decay sheds some insight on what exactly those tricky Epilogues mean.

Paradox Space appears to be a closed system that overcomes entropy. It can go both up and down despite being closed. It continually chews up and recycles its own parts to continue its progression, similar to how Hussie brings back seemingly irrelevant details to create meaning later. As characters state innumerably throughout the story, everything in Paradox Space is a "S3LF FULLF1LL1NG CLUST3RFUCK," designed with the sole intention of continuing the existence of Paradox Space.

But Paradox Space cares nothing for the existence of its constituent parts beyond what they can do to further itself. And because of this, the characters, while trapped within Paradox Space, cannot truly progress. They go up every time they go down, down every time they go up. Every state of maturity breaks apart into a state of immaturity, every revelation or self-understanding is later reframed as a shortsighted false epiphany. Eventually, like John at the end of the Meat epilogue, they are unceremoniously mulched so that Paradox Space can continue.

Where's the escape? In a world where the worth of an individual is only how much use can be drained out of them until they break, how does the individual "come of age"?

I think, moving forward, I'll keep a closer eye on how each character interacts with Paradox Space, that unseen clockwork machinist putting all its cute pieces together for the sake of continuing itself. If Homestuck is a "coming of age story," I do not believe it has an altogether positive view on the ability of children to mature and develop. Hussie may have intended it to at an earlier stage of Homestuck's creation, but that was PAH, Past Andrew Hussie. It has been, what, seven or eight years since that Formspring post?

TT: I'm starting to see that. TT: So the exiles are on Earth? Does that mean our goal is to get back there too? To resurrect it somehow? GC: NO NO NO GC: S33 1RON1C4LLY TH3Y G3T TO DO TH4T GC: 4FT3R TH3YR3 DON3 H3LP1NG YOU TH4T 1S GC: YOUR JOB 1S OF GR34T3R CONS3QU3NC3 TO S4Y TH3 L34ST GC: BUT P4RT OF TH31R JOB 1S TO R3BU1LD L1F3 4ND C1V1L1Z4T1ON TH3R3 GC: 4ND 1F TH3YR3 SUCC3SSFUL 1N THOUS4NDS OR M1LL1ONS OF Y34RS TH3 T3CHNOLOGY 1S UN34RTH3D 4ND TH3 PL4N3T 1S R1P3 FOR S33D1NG 4LL OV3R 4G41N

Oh hey, rebuilding and reseeding. Even the dead planet gets recycled so that another session of SBURB can begin.

(End of Meat epilogue, 2010 colorized.)

GC: 1M MOT1V4T3D BY S3LF 1NT3R3ST GC: TO H3LP YOU 4DV4NC3 MOR3 QU1CKLY GC: B3C4US3 1V3 GOT YOUR WHOL3 ADV3NTUR3 R1GHT H3R3 1N FRONT OF M3 EB: do you have a braille screen or something? GC: SHHHHHHHH! GC: 4NYW4Y TH3 PO1NT 1S GC: 1TS LONG AND BOR1NG GC: 4ND YOU COULD ST4ND TO SK1P SOM3 ST3PS

Vriska will eventually take on the role Terezi is performing here, but this exchange hearkens back to what I was talking about in the previous Hymnstoke about "skipping to the end." Doing it here gets John killed, because of course this skip is meant to "FUCK UP TH3 T1M3L1N3." At other times, screwing with the timeline is exactly what the timeline requires, so it is allowed in that instance (and it's even allowed in this instance because the doomed timeline created here allows the main timeline to progress in a necessary way). The concept of temporal causality, introduced in the Intermission, becomes more explicit in this episode with Terezi and John and the jetpack. Where Spades Slick and the Felt played by temporal rules, John will not, and the consequences for those actions will be revealed, as well as the harsh truth: the individuals within the system have no choice; the system commands their actions.

GA: I Just Would Like To Gather GA: Some Means Of Gauging Her Sincerity TG: ok well its easy TG: for everything she says take her to mean just the opposite TG: see not everybody always means literally what they say the way john and jade always do GA: Maddening GA: How Do Humans Forge Meaningful Relationships Using Such Communication Patterns GA: Perhaps It Is The Human Riddle That Is Truly The Ultimate Riddle

While this quote touches on the irony versus sincerity angle as it pertains to the kids, the reason I bring this passage up is: What the hell was the Ultimate Riddle? I completely forget if it was ever meaningful whatsoever. Did it get answered? Does it even show up after Act 5? Act 5 (and Act 4, its prelude) is so divorced from everything that comes before and especially after it. Act 6 gleefully forgets anything that happened in Act 5, and the Ultimate Riddle is only one of its many casualties.

I guess if you slap something into a story called "the Ultimate Riddle" you're going to provoke people to try and answer it, even if the riddle lacks any substance whatsoever.

GC: TH3 HO4RD CONT41NS SO MUCH MOR3 GR1ST TH4N YOU COULD 3V3R US3 1N 4N 4LCH3M1T3R GC: 1 M34N YOU COULD 1 GU3SS GC: BUT TH4TS NOT TH3 PO1NT GC: 1TS FOR TH3 ULT1M4T3 4LCH3MY EB: what's the ultimate alchemy? GC: 1TS NOTH1NG FOR YOU TO WORRY 4BOUT NOW

I think the Ultimate Alchemy also doesn't matter? I don't remember it, at least, although maybe it had more of an answer than the Ultimate Riddle. I think SBURB as a game doesn't matter all that much, that a lot of it is, eventually, skipped Vriska-style. (Maybe the Ultimate Alchemy created Caledfwlch? I seriously forget.)

JASPERSPRITE: Rose im just a cat and i dont know much but i know that youre important and also you are what some people around here call the Seer of Light. JASPERSPRITE: And you dont know what that means but you will see its all tied together! JASPERSPRITE: All the life in the ocean and all the shiny rain and the songs in your head and the letters they make. JASPERSPRITE: A beam of light i think is like a drop of rain or a long piece of yarn that dances around when you play with it and make it look enticing! JASPERSPRITE: And the way that it shakes is the same as what makes notes in a song! JASPERSPRITE: And a song i think can be written down as letters. JASPERSPRITE: So if you play the right song and it makes all the right letters then those letters could be all the letters that make life possible. JASPERSPRITE: So all you have to do is wake up and learn to play the rain!

God damn, we are just going on a tear of "shit that is introduced like it's important but turns out to be not important at all." I recall in particular several people were annoyed that Rose never "played the rain," that it was a point foreshadowed but never acted upon. But rereading this story from the viewpoint of knowing what is and isn't resolved, I think it's no accident that all these game concepts (Ultimate Riddle, Ultimate Alchemy, play the rain) are introduced in such rapid succession and all wind up not being that relevant. The quantity of these esoteric terms undermines their ostensible quality; when faced with Ultimate This, Ultimate That, the reader fails to affix narrative importance to all of it. And because all these things do, in fact, wind up being barely relevant (if relevant at all), this stylistic presentation turns out to be entirely appropriate. Of course, these pointless Ultimate Whatevers are framed against the backdrop of John "skipping to end," so the concept that certain things might not be important should already be implanted in the reader's mind.

Does that make Paradox Space not as efficient as it seems to be? That's one interpretation, but here's another, based on a point I made previously: What is important for Paradox Space is not important for the characters. Paradox Space can put forth an Ultimate Riddle, and to Paradox Space that riddle may, in fact, be important. But it's only more jumbled detritus to the protagonists, a collection of obscure terms that are ultimately less important on their personal paths than, say, Con Air. And this fact might suggest that creating your own path ("skipping to the end") might be more important than following the preset path laid out for you, the path created by the system (society, biology, your parents, the government, whatever you consider the "system" to be). John's jetpack excursion fails. But it wasn't his idea to skip ahead anyway, it was Terezi's. He wasn't following his own path. Hence, his failure.

However, in this Jaspersprite instance, "irrelevant" is not a completely fair assessment. A song that can be written down as letters? The letters can make life possible? Jaspersprite also says this:

ROSE: Jaspers, the message you gave me years ago before you disappeared... ROSE: What did you mean? JASPERSPRITE: Meow. ROSE: Sigh... JASPERSPRITE: :3 ROSE: I don't understand.

M, E, O, and W are the four letters that represent GCAT and become essential later in Act 5 for creating Becquerel (if I'm remembering correctly). I think it's those letters that Jaspersprite refers to when he tells Rose to "learn to play the rain," meaning this mystery, at least, is not only relevant but was resolved long before things in Homestuck stopped being resolved.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymnstoke XIV

Like Act 2, Act 4 opens with a walkaround game.

I didn't comment much on the game at the beginning of Act 2, despite it being one of those much-discussed multimedia elements that make Homestuck so distinctive. In Act 2, the movement from linear story to game serves several purposes. First, it demonstrates an increase in scope, both in terms of Homestuck's story and in relation to Hussie's previous effort, Problem Sleuth. While Act 1 incorporated a couple of new elements not seen in other MSPA comics, such as protagonists capable of speech and a handful of simple videos, the Act 2 walkaround is the first dramatic increase in what readers could have reasonably expected from the comic at the time.

Secondly, the novel concept of incorporating a game into the story corresponds to and emphasizes the novel concept of SBURB within the narrative of Homestuck. Just as the world in which John now finds himself is completely new and unexpected, so too are the readers introduced to this world through a new and unexpected medium. This world is even called the "Medium"—and surrounding a space (Skaia) described as a crucible of pure creation. I previously discussed the significance of SBURB's geography in regards to Gnosticism, but one could also interpret it as a statement on Homestuck as a creative enterprise. A crucible of pure creation through which a new world, or a new mode of expression, will be built. Like how John and friends attempt to create a new world from the fragments of the old, Hussie creates a new kind of story from the fragments of all types of storytelling that came before it. Image, text, video, sound, game—Homestuck strings together these disparate modes of expression into an original creation. In short, the method by which Homestuck is presented mirrors its explicit thematic content.

Wikipedia defines phenomenology as "the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness." Remember how I mentioned that the modernists were often concerned with the conscious and subconscious, and how many attempted to reach truth by depicting the subconscious? Similar concept here.

I was introduced to the term "phenomenology" in relation to art history. In particular, my professor applied the term to modernist painting and sculpture that was designed so that the act of experiencing it changes its meaning. Let's take the following sculpture:

"Sculpture?" you may ask. Yes, I know. It looks more like a misshapen industrial structure. The problem with this sculpture is that no single photograph can truly depict it. Here's the same sculpture from a different vantage:

Another:

Still another:

Top down:

Is this sculpture broader at the bottom or at the top? What shape is it, exactly? You can find this sculpture at the University of California, Los Angeles, and you can even go inside it through the opening visible in some of the photographs. Inside, it takes on a completely different appearance, although unfortunately I couldn't find any good pictures of the inside that didn't have a gigantic Getty Images watermark on them.

In art, this phenomenological experience often boils down to optical illusion or a similar technical trick that appears novel at first but lacks much substance beyond its presentation. What meaning can we derive from this experiment or others like it?

I believe that the phenomenological creations of the modernists eventually reached an apotheosis in a more contemporary form of creative expression: Video games.

The way the player perceives a video game, even a video game you might consider simplistic or linear, is directly affected by how the player plays the game. Take, say, Super Mario Bros. (1985) for the Nintendo Entertainment System. In this game, the player moves Mario left to right to reach a fixed goal. But even this game is affected immensely by the innumerable choices each player makes in playing the game. For an extreme example, compare how a speed run of Super Mario Bros. looks compared to any casual experience of the game. Some elements of the speed run even involve elements assuredly not intended by the game's creator (glitches, for instance). But even at a less extreme level, every player's experience of Super Mario Bros. will differ depending on the routes they take to reach the end, the strategies they employ to evade obstacles, or even the amount of times they die before finally succeeding.

Why do I bring this up? The concept of phenomenology ties into Homestuck's "reader participation" elements, both via the prompt suggestions early on and the more psychological effect the fandom has on Homestuck's development in its back half. Of these two "reader participation" elements, the latter is the one that is probably better described as "phenomenological," in that it is the readership's perspective of Homestuck that eventually drives its trajectory (as opposed to the prompt suggestions, from which Hussie could pick and choose at will). In the back half of Homestuck, the narrative plays more and more on the author's interpretation of the readership's interpretation of the narrative, becoming a perspectival mobius double reach-around where the true driver of the narrative's creation becomes increasingly unclear.

But more specifically, I want to discuss this walkaround game at the beginning of Act 4 in particular. Compared to the one at the beginning of Act 2, this walkaround is not increasing Homestuck's scope. John is entering a new location, but the experience is less novel than entering the Medium in Act 2, both in terms of John's perspective and the reader's. While the Act 4 walkaround features mechanical improvements (inventory, combat) over the Act 2 walkaround, it is still essentially the same thing: a video game. The reader has seen this before in Homestuck. It's not new.

I cannot speak for the experience of every reader, but each time I read Homestuck I am tempted to skip this walkaround entirely. The combat mechanics are banal, the camera is zoomed too close to John to allow for satisfying exploration of an unfamiliar world. In Act 2, the walkaround takes place in an area with which the reader is already geographically acquainted (John's house), so the camera issues are less apparent. But trying to navigate this twisting maze of blue paths, surrounded on all sides by nondescript rocks and mushrooms, can become frustrating. Even if I consult the supplementary map image, I find it somewhat difficult to figure out where I am and where I'm supposed to go.

Which is just the thing. The reader is not supposed to go anywhere. There is no real resolution to this walkaround. The same, in fact, can be said for every walkaround, and we will continue to get amazingly nonessential walkarounds in the acts to come. What does the reader miss if they skip this Act 4 walkaround? Some tedious exposition on the nature of John's planet, its consorts, its customs. Superfluous W O R L D B U I L D I N G that the Homestuck narrative is quick to forget from henceforth on.

It kind of makes me want to, shall we say, skip to the end.

In Act 5, Vriska and Tavros will discuss how the way one plays a game affects the way the game is perceived. Hardcore speed runner Vriska will take my side of the argument and skip what she can; Tavros, more in line with readers inclined to learn as much about SBURB's lore as possible, will argue instead for assiduously completing every task. This conflict—between speed and lore, content and fluff, meat and candy if you will—eventually becomes the core and final dichotomy of Homestuck. But in Homestuck's later stages, the characters and narrative will apply this dichotomy not to how we experience video games, but how we experience all art—and how we experience our actual lives. I intend to trace that development, and this walkaround serves as a fine introduction.

In a few years, Flash will be deprecated and you'll only be able to experience this walkaround through this series of images. I don't know who created these images, or whether laziness or incompetency made them so shitty and SBaHJ-esque. But I give that person props for maintaining that sense of "God this sucks, can I just skip it?" Good job, intern.

You switch to PICTIONARY, a choice based on a strong whim from the mysterious ethers of democracy.

Another one of those traps, like the suggestion prompts. Wow! The readers get to pick Jade's fetch modus! What an amazing display of reader/author interaction! Except Jade's fetch modus doesn't matter. In fact, as we transition into this next phase of the story, nobody's fetch modus will matter. The fact that all of Jade's possible fetch modii are total jokes only emphasizes the point.

I mentioned in the previous Hymnstoke that we're entering what I'm calling the "clockwork" part of Homestuck. In this part, Homestuck's audience has the least amount of control over its progression. While the suggestion prompts were mostly irrelevant because Hussie could pick whatever prompt he wanted, they occasionally paved actual story or character developments ("Become the mayor of Can Town") or formed memetic jokes that would mutate over the course of Homestuck into part of its mythos. And in Act 6, the immensity of the Homestuck fandom and its increasingly vocal demands will lead to a more subtle transition in what Homestuck becomes—the mobius double reach-around I mentioned previously. But here, in the clockwork part of the story, it's more Hussie than anywhere else. Of course it would be. It's Dirk, Hussie's analogue (connected via a series of motifs like horses and robotics), that comes to represent the Meat side of storytelling, that describes the way a story should be told as a perfect machine. An unfocused, nebulous gaggle of "readers" cannot hope to coordinate among themselves to create something so precise and efficient. Their strengths lie in different directions.

Ok, have at it! If you're at a loss, click the controller button up there.

This may or may not mean anything to you depending on your current perspective.

As it turns out, the story retreads everything that happens in the Act 4 walkaround anyway, making it even less relevant. Even Crumplehat and the Salamander Wizard appear as the walkaround's events are depicted from PM's perspective. This recap is actually pretty extensive, similar to the shitty SBaHJified image walkthrough that got put up in anticipation of Flash's deprecation.

I wonder if Hussie was self-conscious about people's patience for the walkaround? Or maybe he already anticipated Flash would not last forever? Perhaps he added this recap for accessibility reasons, in case of visually-impaired readers? Maybe he felt some new insight would come from seeing the same events replicated from a different character's viewpoint? Or maybe he simply wanted to reveal that the person speaking to John during the walkaround was PM instead of WV?

I'm doing exactly what I said I wouldn't do and trying to delve into Hussie's psyche. As it stands, the addition of this recap makes certain elements of the walkaround mandatory experiences for the reader to progress, as opposed to the walkaround itself which can be ended without experiencing anything. I'll leave the discussion by reiterating the second part of the quoted text:

This may or may not mean anything to you depending on your current perspective.

And I think it's safe to say our "current perspective" is much different than those who read this first.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just read Homestuck^2 again. The meat/candy dichotomy comes through in everything (Davebot's conception kinda feels like a blatant contrast to Dave's arc in Homestuck, hero's call and all). In the bonus content, Dirk even invoked the "reversal of entropy" thing that you indulged in back when you did hymnstoke. Homestuck^2 is still boring and bad, but it's a shame we may never get to see those ideas more thoroughly explored. With the way Homestuck plays meta? OH THE POSSIBILITIES, any thoughts?

They shoulda gotten me to write HS^2

I think I mentioned this in a previous ask, but my experience with HS^2 was reading the first update, finding it excruciatingly boring, and never looking at it again. I also felt like Homestuck got a perfectly fulfilling and conclusive ending with the Epilogues. All throughout Homestuck proper, there's this constant inescapable cycle of plot, literalized via the shitty circle of Paradox Space and Lord English's machinations wherein, and it's made increasingly clear that simply doing what the game expects and beating it is only what the game wants; it's not a tenable way to reach any kind of end.

After all, it was the trolls who originally "beat the game" by powergaming and bumrushing the boss, and that only led to a bigger game, and a bigger game beyond that, and a bigger game beyond that. When Karkat and crew bemoan that they fucked up by not doing the stupid frog breeding minigame, they're not talking about the stupid frog breeding minigame. They're talking about their inability to actually develop as people throughout the game. Frog breeding is the literal reason their game wasn't done right, but it's their personal stories that are the real, thematic reason.

Vriska exemplifies this theme the most. She wants to skip to the end, skip all the lore, find ways to win faster and better. And it's why she fails constantly. At least until Game Over, where a completely superfluous retcon (the Game Over timeline is perfectly salvageable given all the return-from-death horseshit Hussie had introduced by then--just give the Ring of Life to Jane and everything is honky fucking dory) brings Vriska back to life, she fixes everything during a three-year-spanning montage, everyone beats up some bad guys, et cetera et cetera. It's the ending you write if you've used up all of your life's energy during a four-year period of insane creative output and simply want the story to fucking end.

The Epilogues, where a somewhat regenerated Hussie could lean on some extra writers to handle a lot of the prose, ideologically bring Homestuck to the conclusion that makes sense for Homestuck. It doesn't matter that the Epilogues end with some dumbass new plot hook with spaceships and whatever-the-fuck. Actually, it does matter, but it matters because John is no part of it. John reaches the end of the story not by resolving some plot, but during that final scene in Candy of matrimonial reconciliation with Roxy. John has reached an ending, and yeah, there's some new adventure going on in the background, but to him, it's finally in the background. He's won his game.

Hussie logically understood this was how Homestuck had to end even during the rushed-and-gunned-it original ending. It's why the lilypad section exists, where everyone hugs it out and talks through their emotional issues and whatnot. A lot of people I know constantly bring up Hussie saying "real people don't have character arcs," but it's clear he was being facetious when he said that or babbling like he usually does, because the lilypad is just a way for him to try and tie up every character's arc in a few choice conversations. It doesn't work, because most everything said on the lilypad is predicated on three years of off-screen growth, so there's no actual throughline from point A to point B on most of the character arcs.

The Epilogues handle it a lot better. Hussie or whoever did the creative legwork said, "Wait, most of these side characters are kind of pointless and never mattered to the plot or themes," so instead of trying to give everyone satisfying arcs, he hones in particularly on John and a few other key characters while letting most of the chaff get embroiled in the latest dumbshit adventure. In both Meat and Candy, John grapples with becoming irrelevant to the "narrative." Literally in Meat, figuratively in Candy. But it's only in this irrelevance that he is finally able to come to deeper insights about himself. And that is what Homestuck has been about for a long time.

Early Homestuck is so orderly, so pattern-driven. Characters are depicted as template-based sprites in static environments and undergo the same collection of banal "life experiences"--fake names, instruments, weird parents, et cetera. John exits to get the mail and we get our first bit of thematic poignancy as he observes his suburban landscape and its bland conformity. He's the same as Dave and Rose and Jade with a different can of paint, really. Trapped inside a system that controls his every action, even though he believes himself to have individual agency. The system of the suburb is replaced by the system of Sburb, and while the stakes get bigger and the character customization options get more robust, it's still a system of control that dictates his every move. All of his actions are preordained, and if he does manage to deviate from his route it's a doomed timeline. Only one path is possible.

John in the Epilogues finally decides to just stop playing. This leads to his elimination as a viable narrative actor, but there's peace in that decision, peace in fading away and just living a life. His emotional peace is juxtaposed against the increasingly absurd narrative of the Epilogues whirling around him, and it makes that narrative seem even more juvenile by comparison. Which I think is the point. I don't think you're supposed to get excited by the narrative prospects of the rebellion against Jane "Trump Proxy" Crocker or Dirk's star trek with robot Rose. The Epilogues end on a cliffhanger, but it's not a cliffhanger where you want to know what happens next. It's a cliffhanger that makes you feel secure in the knowledge that for some, the cycle continues, but others are finally free of it.

As such, I doubt there's any possible way to make HS^2 good. You could clean up the writing, be witty and not boring, but the story will always feel ancillary. Hussie shoving it off on "the fans" is like a practical joke at the fans' expense, but given how HS^2 was cancelled abruptly, it seems most fans sniffed out the joke and, like John, were able to just step away.

Now that's the heart of Homestuck. The theme, the character, the emotional crux of it all. But on the other hand, it's telling to me how much the actual PLOT plot of the Epilogues, the one I just spent a bunch of time saying was "irrelevant" and "bad on purpose," explodes a conflict that has been simmering under the surface throughout all of Act 6; the conflict between Hussie and his readership. With Dirk as Hussie's stand-in, and Calliope as the readers', this conflict is brought to the most overt level it has ever been at throughout Homestuck--even more than when there was a literal Hussie self-insert prancing around. Seen in that light, John's decision to just... fade out of the fight, coupled with Hussie making such a big deal about "handing over the keys to the fans" for HS^2, seems like a narrative way for Hussie to cede that battle. He exited Homestuck just like John did. Sure, Dirk keeps fighting. But if Hussie's not there, Dirk is no longer Hussie. He's just some guy named Dirk.