#hu lao gate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dynasty Warriors 5 Playstation 2 2005

#lu bu#hu lao gate#Dynasty Warriors#DW5#Dynasty Warriors 5#Playstation 2#sony#2005#nostalgia#00s#2000s#koei tecmo#ps2#retro gaming#sixth gen#gaming#video games#playstation#halberd#game gif#omega force#koei#three kingdoms#romance of the three kingdoms#rot3k#ps2 games#ps2 nostalgia#warriors#china#musou

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Shin Sangoku Musou#Dynasty Warriors#Shin Sangoku Musou Origins#Dynasty Warriors Origins#The Wall of Fate -DW Origins Mix-#The Wall of Fate#~DW Origins Mix~#Hulao Gate#Hu Lao Gate#Haruki Yamada#music musou#tune warriors

4 notes

·

View notes

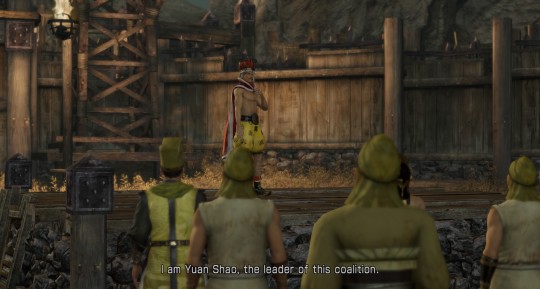

Photo

Yuan Shao giving a rousing speech before the Battle of Hulao Gate in one of his DLC outfits in Dynasty Warriors 8.

#dynasty warriors#dynasty warriors 8#yuan shao#dlc#hulao gate#hu lao gate#shin sangoku musou#the naked emperor#naked emperor#the emperor's new clothes#shin sangoku musou 7

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

COMPLETED: Dynasty Warriors 3 - Dian Wei Campaign

I didn't mean to keep playing. I had plenty of things I needed to do. But this game...it calls to me.

I had a little less fun this time than with Guan Yu. Part of it might be that the shine of nostalgia had run a little thin. Or maybe because I had some great items, I thought I could accomplish more with less. Also, Dian Wei has less range--by a little--so I think I had to adjust.

A challenge to Dian Wei is that he starts at Hu Lao gate, which is slightly more challenging than the Yellow Turban rebellion, and Lu Bu is there, ready to knock you out with a single Musou attack. And then his levels extend beyond that of Guan Yu's--meaning you face even greater challenges. The battle of He Fei castle is about as challenging as any of the levels get--which also means great officer drops--if you can survive. Also, I switched the game to Easy to finish up Guan Yu. I didn't do that this time. I did pick up some extra special items.

To get Dian Wei's 4th weapon I had to play the Wan Castle, Cao Cao escape. It seemed easy at first but then it got harder. I helped Cao Cao get to the exit--but he didn't escape. I cleared out the other offices, and Cao Cao still didn't escape. Then the final boss was standing 50 yards for Cao Cao, but wouldn't engage. I tried to engage, but got my ass kicked. The level only has about 15-20 minute limit so things were getting desperate. I had already almost died about 10 times, and now I was going to lose by default. WHY WOULD CAO CAO JUST RUN OUT THE DAMN DOOR?!

With about 3 minutes left, Cao Cao engaged the boss and I was able to sneak in hits with only about 5% health left. It was terrifying. And this is honestly a common experience with the rest of Dian Wei's campaign, only, I didn't always come out on top.

Part of the problem was my body guards. Guan Yu seemed to get 8 elite guards exactly when I needed them. No matter how many guards I got with Dian Wei, they just couldn't survive. I saw that they level'd up in attack but not so much in defense. Maybe they just never had a chance.

I did unlock some new levels that will be great for leveling up if I keep playing. I meant to start Munch's Oddysee...not keep playing DW3. But...we'll see.

#Zach's Game Journal#Dynasty Warriors 3#Dian Wei#COMPLETED#Video Games#Gaming#PlayStation 2#PS2#AetherSX2

0 notes

Video

youtube

Doug Plays Dynasty Warriors 4 Pt 3 - Why Did I Fight Lu Bu

#dynasty warriors#dynasty warriors 4#lu bu#hu lao gate#si shui gate#koe#koei#koei tecmo#hack n slash#let play#doug plays#mad hen house

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

INKTOBER 4 - Lu Bu, Dynasty Warriors

For those of us who have played the Dynasty Warriors series, we know that when Lu Bu arrives it is synonymous with Death, especially in the Battle of Hu Lao Gate.

Especially for me the Dynasty Warriors 5 which was the first one I played, Lu Bu was very overpower even at an easy level, there are 2 options to die before him if you were not prepared, you would die if he ran you over with his red horse or he killed you with a spear.

For worse in the battle at the Battle of Hu Lao Gate, the main objective is to defeat Dong Zhuo and avoid facing Lu Bu, but the allied soldiers their AI is idiotic, they were approaching the main gate where Lu Bu is and you know since this battle went to hell.

I admit that the first time I beat him it was on an easy level and with the help of my best friend Pamela, without her you can't complete the game just because of the battles when you face Lu Bu.

Another Inktober of "the difficult bosses that faced me" from this year.

Eme

#inktober#inktober 2020#lu bu#dynasty warriors#dynasty warriors lu bu#dynasty warriors 5#inktober 2020 day 4#inktober day 4

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you prefer a DW game to be completely Historic without any fictional aspects like characters like Diao Chan and battles like Hu lao gate or do you like that DW leans heavily on the fictional aspects of the Three Kingdoms ?

Take from this answer what you will. My opinion on any semi-historical adaptation is as follows: (this turned into a long, kind of rambling essay.)

First and foremost, I think it is the responsibility of anyone adapting something from history to represent the real people involved with integrity. People who did terrible things shouldn’t have that covered up for the sake of the narrative. People who did heroic deeds shouldn’t have their efforts dismissed. Even if used fictitiously, these were real people. Their hopes and dreams were real. Their suffering and struggles were real. And if you’re doing any kind of adaptation it is important to represent those things honestly. You have a duty to show people for who they were - or, more practically, who you perceive them to be.

Obviously the easiest way to do that is to stick as close to recorded facts as possible. The less you deviate from the truth, the less you have to worry about. If the narrative just doesn’t let you incorporate something factual, then it’s your responsibility to try to get as close as you can. The Sanguo Yanyi usually has Taishi Ci die heroically at Hefei. And while that didn’t happen it does show him as a brave man and a powerful warrior whose unexpected death is widely mourned. That’s now how it happened, but it at least represents the spirit of the man faithfully.

And sure, there’s room for ambiguity. Who is the “hero” in a story about Wei’s Zhengshi period? What were someone’s real motives? What were they really like? Our records only show certain sides of people. That’s okay. That ambiguity is where you have room to improvise and build a historical figure into a character. But if you’re taking advantage of ambiguities to wave away serious problems, you’re not acting in good faith

There is a lot of ambiguity, for example, in the Zhengshi period. At the same time, there are some interpretations that are simply not made in good faith. I don’t believe that anyone can look at Sima Yi’s actions and honestly believe that they were selfless, taken only in the interest of preserving Wei. You could argue that they were justified and logical, but saying that he was doing it all for “the greater good” would be dishonest. Depicting Cao Shuang and his group as innocent victims attacked senselessly by a jealous rival who just wanted to seize power is just as dishonest, as it requires one to ignore the efforts they made to consolidate power. You can build a good character in the ambiguities and the things left unsaid, but it should always come from a place of honesty.

This is a roundabout way of saying that the most important thing to get right - the thing that matters to me more than anything else in adapting a story - is representing the people involved with honesty and integrity. They were real and whether you see them as heroic, villainous, or elsewhere or that spectrum (most people were, of course, in the gray area between) it is important to show them honestly.

The easiest way to do that is, as I said, to stick as close to recorded facts as possible. The more inventions you toss in, the farther from the truth you’ll wander. You mentioned Diao Chan and Hulao, and those are actually two good examples on the opposite ends of this continuity.

Hulao is, of course, a fictional battle. It is often preceded by a battle at Sishui (which appears to have been another name for the same mountain pass) and followed by a battle where Cao Cao gets ambushed and is no longer able to pursue Dong Zhuo. The Sishui battle is pretty directly inspired by the battle at Yangren, the battle at Hulao is inspired by Sun Jian’s battle against Dong Zhuo at Dagu Pass, and the ambush is inspired by the battle at Xingyang between Cao Cao and Xu Rong, which actually happened before Yangren and Dagu.

As an adaptation of those three historical events (Xingyang, Yangren, and Dagu) Hulao is terrible, particularly at the Sishui and Hulao portions. at Yangren, Sun Jian defeated Lu Bu and killed a staff officer named Hua Xiong (a man of no special importance. Then at Dagu he defeated Dong Zhuo himself and drove him off to Chang’an. At Sishui, however, Sun Jian is unable to accomplish anything and Hua Xiong cuts through many fictional characters before being killed by Guan Yu - who was not at Yangren, the battle that inspired it. At Hulao, Lu Bu does the same feat before Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, and Liu Bei fight him to a draw. Again, none of those men were actually present at Dagu. That was all Sun Jian.

So in adapting Yangren and Dago into Sishui and Hulao to better fit the narrative, Luo Guanzhong completely cheats Sun Jian out of all credit. He was the only character to have success against Dong Zhuo, but he is rendered a minor figure and upstaged by three men who didn’t even fight against Dong Zhuo (they were in Qing or You at the time, nowhere near the campaign against Dong Zhuo). This is an adaptation with no integrity. Sun Jian is robbed of his heroic accomplishments and glory is showered on people who did not earn it.

The Diao Chan story, on the other hand, is a pretty fair adaptation. The woman herself is fictional but the events the story depicts are reasonably close to the truth, if a bit embellished. There was a rift that formed between Dong Zhuo and Lu Bu - and while it wasn’t due to both desiring the same woman that rift was very much a real thing, brought about in large part due to Dong Zhuo’s terrible treatment of Lu Bu (even throwing a halberd at him once). And Wang Yun did take advantage of this rift to turn Lu Bu against Dong Zhuo. This allowed him to arrange Dong Zhuo’s assassination by Lu Bu’s hand - all of which does happen in the fictionalized version of the tale with Diao Chan. My only major qualm is that it writes out Shisun Rui, who was another major architect of the plan, but he didn’t want credit for it anyway so I can let it slide.

What I’m saying is, it’s all about integrity. It’s easiest to represent people honestly when you just stay close to the truth. Inventing and embellishing things is fine - that’s how you get a story instead of an essay. But those inventions and embellishments should serve to reinforce who these people really were, not cover it up.

So what I ask from any adaptation of any historical period - Dynasty Warriors or something else - is this integrity. I don’t demand strict accuracy or realism but it’s easiest to achieve this integrity when you stick close to the truth.

One other thing I’ll add is that in most cases, and especially in the Three Kingdoms, I find the truth to be far more interesting than the stories made up later. I prefer that any adaptation/narrative about the period stay close to the truth not just to represent people with integrity but because the events that actually happened are usually more exciting than invented tales. And history can get away with things that fiction can’t. The story of Taishi Ci rescuing Kong Rong is downplayed in the Sanguo Yanyi because even for a novel like that, the truth seems hard to believe.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Games in 2021, Part 1 (January)

I have decided to play through all the Musou games I can get my hands on. Let’s see how long I last before I regret this decision.

= = =

Dynasty Warriors 2 System: PS2 Genre: Hack and Slash, Musou subgenre

I am committed to replaying the entirety of the Dynasty Warriors series this year, though technically I’ve never played Dynasty Warriors 2 before...

Anyway, I have seen this game likened to a tech demo and... yeah, that’s basically what it is. It was probably impressive for its time but in the year 2021, there’s no real reason to revisit this game.

It’s the Musou formula in its basest form. To give a sense of what that’s like, just picture Dynasty Warriors 3 but with less features. You don’t unlock rare or even new weapons (you’re stuck with that four hit combo all game baby), you don’t unlock or equip items, you don’t have much voice acting during stages and you can’t save from the pause menu mid-battle.

What is here is *checks notes* a system where, for some reason, if you knock an opponent down, they have a chance to fully heal themselves. You also have a counter attack that staggers enemies, which would be great except oops, this counts as a knockdown, so this just helps the enemy instead. Great.

Oh, and I guess bodyguards are still a thing. And archery was actually in this (I expected this to be an addition to DW3, but no, turns out this was in DW2). Also the draw distance for DW2 is like the draw distance for DW3′s co-op mode, except it’s for the entire game, not just co-op, and also there is no option for co-op. It’s a really weird experience. It’s like running into Lu Bu in Hu Lao Gate but Lu Bu doesn’t have theme music, no one is telling you to not pursue him and also he’s not that much harder than any of the other generals (if that example sounds overly specific, that’s because that’s exactly how Lu Bu is in this game.)

To be a bit more positive, the game has a whopping 28 character roster for its first game (even if that number is achieved through copious weapon cloning). There are also some fascinating oddities about this game. The lack of voice acting, for example actually makes battle messages / updates happen way faster. As someone who is currently replaying DW9 and has to sit through its horribly, horribly slow battle update system, this is quite amusing. I also mentioned the in-battle save system; you can’t pause and save whenever you want... but what you can do is break open a pot and pick up an item that *does* let you save. Putting aside the surreal imagery of picking up a giant sized PS2 memory card in the middle of an ancient Chinese battlefield, I actually quite like this system. From a game design perspective, this seems like a much fairer and less cheesier way of doing in-game saves.

Also the horses in this game are ridiculous. They still control like they do in DW3 (i.e. really badly) but in this game, enemies get hit by them like they’re being hit by cars. I think you can even infinitely juggle enemies with a horse (so long as you get them against the wall).

Though the later games have improved on a lot, it seems not everything they left behind was actually bad. With all that said, Dynasty Warriors 3, really does supersede this title. While you might find value in playing DW4 and DW5 for the differences in storytelling and characters interpretations, there’s not much to say since DW3 is really just a more complete version of DW2. There’s no stage in DW2 that’s not in DW3, all of “DW3′s music” is actually DW2′s, and most of the characters got very light touch ups to their designs (with some exceptions, like 80′s hair-Zhang Jiao and bucket helmet-Yuan Shao).

Mystic Heroes System: PS2 Genre: Hack and Slash (Musou subgenre, sort of)

How come no one told me that this game had kid Taigong Wang and female Nezha in it

Anyway, Mystic Heroes is a Musou-lite game by Koei that released after Dynasty Warriors 2 and 3. It is based on the Fengshen Yanyi, sort of. Koei apparently has this entire Fengshen Yanyi trilogy of games, with Mystic Heroes technically being the third in the trilogy. As for why the first two are so obscure, it’s because those games never made it out of Japan.

Mystic Heroes isn’t really a Musou game, hence the Musou-lite descriptor. It is very, very obvious that it uses the DW2/DW3 engine but it has differences (like less focus on AI allies and morale, and all characters having stronger crowd control moves) that it’s more like a beat em up. As for whether a dumbed down Musou game could be any good, it’s... okay. Not bad, but not terribly good either. The game is at its best during the battlefield levels. On such levels you can aggro every enemy, gather everyone in one spot and then decimate them with your invincibility-frame laden special attacks.

It’s a shame that the more ambitious parts of the games (like the boss fights) feel very clunky. Mystic Heroes’ combat system is great when you get into a chaotic brawl but when the game asks you to act more precisely to avoid a bosses attacks, it it can be a very frustrating experience.

...Nothing to say about the game’s other aspects. The story had me completely lost (I’m not particularly familiar with the Fengshen Yanyi) though I’m pretty sure Daji and Yang Jian are also in this game (albeit as NPC’s). Oh! I did love this game having female Nezha. It’s probably that early 2000′s deal where “Japan does effeminate male design, localizers mistake character for female” since there’s another character in the game who is mistaken for a girl (who has an animal form that is basically ‘topless anthropomorphic bird person’), but it was still cool to see.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Campaign of Liu Ji Part 3 (Final!)

A continuation from this post, and the conclusion to this most recent play-through of Romance of the Three Kingdoms 14. When it came to beginning the inevitable battle with Cao Cao, I was a little hesitant at first. It seemed like it was going to take a while and I wasn’t sure how interesting it would be to play. But I soldiered on. It was a bit of a stalemate for a while, with neither of us gaining or losing any ground, but the computer had a tendency to over-extend itself and leave places vulnerable. And I already had more cities and troops, so it was really only a matter of time. I spent one entire evening just shuffling around officers and moving troops and resources from place-to-place. If I hadn’t been writing out this loose narrative for my campaign, I doubt I’d have been motivated to finish it. I’ll be interested to see how this game changes when the power up kit is eventually released, as at the moment its a little bare-bones, and most turns are spent rewarding officers to maintain their loyalty and accepting mundane suggestions from advisors which increase agriculture or whatever in a town by ten points. I feel like the narrative I wrote out for this campaign would have been much more interesting to read if I had been more strict with myself about roleplaying the position whilst playing, in terms of (for example) who I could or couldn’t hire, of sometimes losing territory to my enemies when it made sense, and so on. But as it stands, I don’t think this game has enough tools to keep things interesting and varied. Nevertheless, Cao Cao has been backed into a corner and the conflict approaches its end. The fate of the famous three sworn brothers revealed. If you want to know more about the destiny of one Liu Ji, styled Jingyu, read on!

Cao Cao, along with his advisors Guo Jia and Xun Yu, had developed an idea early on of separating the three brothers Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei—in order to prevent them from causing any trouble. Liu Bei would be based in Xuchang with the Emperor, Zhang Fei was to hold the frontlines against Ma Teng in the northwest, and Guan Yu had been involved in conflict in the northeast against Gongsun Zan. Liu Bei desired greatly to travel south to join the forces of Liu Ji, but he was effectively a prisoner, and did not want to be parted from his brothers. If Guan Yu or Zhang Fei shirked their duties in the north, it would have been very costly for Liu Bei and his family. In the years after the conflict with those forces came to an end, Cao Cao turned his attention southward to Liu Ji—with the three brothers still separated across the realm.

To prevent Liu Ji from gaining access to Chang’an, Cao Cao turned his forces toward Liu Ji’s position at Hangzhong, whilst simultaneously advancing on Liu Ji’s bases in Xinye, Shouchun, and in Jianye. It was easily the largest conflict in recent history. Liu Ji was unable to maintain control of Hanzhong, which was a key base for moving on Chang’an. Once the area had been subdued by Cao Cao’s forces, Zhang Fei was placed in charge of the unit now stationed at Hanzhong—presumably to intimidate Liu Ji and prevent him from advancing. But when Cao Cao’s forces came to join Zhang Fei for a full-scale invasion of the riverlands, Zhang Fei refused to open the doors to the city they had occupied. Not long after, he was somehow joined by his sworn brother Liu Bei, who had escaped captivity in Xuchang during the ongoing conflicts with Liu Ji and had snuck his way over to Hanzhong with the help of some supporters in Cao Cao’s territory. As Cao Cao directed his forces to advance upon Zhang Fei at Hanzhong, Liu Ji sent his own generals to support that same position. It transpired that Fa Zheng had also been in contact with Zhang Fei over the past few months—which had made this surprising turn of events possible. Guan Yu was yet to be seen, but the conflict between Cao Cao and Liu Ji had begun in earnest.

Taishi Ci, Ling Tong, Huang Zhong, Wei Yan and Ma Chao were his most capable generals, and had become the pillar of his military force—his five Tiger Generals. Zhuge Liang was promoted to Prime Minister, and Lu Xun became the Director General. He was not lacking for intelligent advisors, but they did not often agree. Even so, Liu Ji enjoyed weighing the value of the various suggestions presented to him, and actively encouraged lively and good-spirited debate within his halls. Spiteful, personal attacks and underhanded comments were not tolerated. This contributed towards a sense of camaraderie among the intelligent officers of his force, and ensured they were motivated and focused on the task at hand, working hard to develop their ideas and consider alternatives which might be suggested by their interlocutors.

Recognizing the value of maintaining a hold on Hanzhong, and furious at the betrayal of Zhang Fei and Liu Bei, Cao Cao dedicated himself to securing the area once more. He sent their sworn brother, Guan Yu—who had become so indebted to Cao Cao through his service over the years, and who had been poisoned with lies about the behavior of his sworn brothers. Zhang Fei met Guan Yu on the field, enraged that Guan Yu hadn’t already come to join his brothers, and was yet a peon under Cao Cao. The two clashed in an intense duel, rending heaven and earth.

Pushing one another to their limits in a battle which had both armies enraptured, more than two-hundred bouts had been concluded. Liu Bei yelled at both brothers to lower their arms and remember their oath. He got between the two in the midst of their duel without a weapon of his own, which took them by surprise. Liu Bei was accidentally struck in the head and bled from his ears. He died soon after. In their distress, both Zhang Fei and Guan Yu took their own lives. Soldiers on both sides attempted to prevent them from doing so, but to no avail. In the chaos that followed, Cao Cao regained control of Hanzhong for a short time. But being spread thin, and fearing Xuchang would fall, was unable to hold it for long.

Across the realm, Cao Cao’s bases had begun to fall to Liu Ji—Cao Mai’s navy was overrun off the shore of Guangling by He Qi and Lu Dai, enabling Liu Ji to build upon his forces on the northern shores of the Changjiang. Sensing that Cao Cao had acted too late to mount a meaningful opposition against Liu Ji, Zhang He turned on Cao Cao’s force at Wan Castle, joining with Liu Ji and providing them access to the castle. Xuchang was now within reach, and efforts were being made by Cao Cao to relocate the capital, and thereby the Emperor, north of the Huanghe to Ye, the Capital of Ji Province.

Xu Province had already been captured by Liu Ji, and the escape route to Ji Province had been cut off. Xuchang swiftly fell. Cao Cao barely escaped with his life, but he was unable to bring the Emperor with him. The carriage of the Emperor was surrounded by Huang Zhong and Wei Yan before it could reach the river. Liu Ji himself led a force through Hu Lao Gate to capture Luo Yang, with Taishi Ci, Ling Cao, and Lu Dai—some of his longest serving generals. Luo Yang was re-established as the capital city and the Emperor was encouraged to resume his role, but he vehemently opposed the idea, exhausted by playing his role as puppet Emperor. He threatened to kill himself if Liu Ji did not assume the throne and continue the Han Dynasty as an imperial ancestor. Hesitant at first, it was only at the insistence of his advisors that Liu Ji capitulated and accepted. He was named Emperor Da of Yang.

Cao Cao had become very ill, often bedridden by severe migraines. Sima Yi took care of most of his duties, which largely involved re-structuring and re-organizing their forces north of the Huanghe. Of his most capable generals, only Xu Huang and Xiahou Yuan were with him in Ye, but both were now over fifty years of age. Xiahou Dun was stationed in Liang Province, cut off from the rest of Cao Cao’s force.

A small force led by Ma Chao slowly encroached upon Xiahou Dun in Liang Province. Although he fought fiercely, being cut off from Cao Cao’s main force, supplies were lacking. The sparse fields of Liang were not enough to support a standing army, and morale was low. It is said that Xiahou Dun fought until his last breath. Ma Chao was elated to be able to recapture the lands rightfully belonging to his family.

This was now a time for Emperor Da and his forces to rest and recuperate, and focus on domestic affairs. A great deal of discussion centred on moving the capital again to somewhere in the south, but such discussions were tabled until a time when the realm had been completely unified. Liu Ji, now almost 40, had a daughter, but had yet fathered no sons—and this was another active point of discussion.

Many messages were sent to Cao Cao to entreat him to surrender his forces, but he adamantly refused. After a few years, the Emperor commanded that an enormous force cross the Huanghe and capture You, Ji, and Bing. But before the conflict could begin, Cao Cao suddenly passed away in the spring of 221AD. Sima Yi was the architect of the discussions which followed, pledging fealty to the new Han Emperor and surrendering their forces. Gongsun Gong eventually followed suit, and the realm was completely unified by 223AD.

Some years of peace and prosperity followed, but unrest remained surrounding the Imperial lineage. Sima Yi worked diligently at involving his family in Imperial affairs, ingratiating himself to the Emperor—he petitioned to have one of his sons marry the Emperor’s daughter and become Prince. The remaining members of the Sun family sought recognition for having supported the Emperor since His earliest days, and demanded the Emperor’s daughter marry one of their number. Any talk of moving the capital to the southlands was seen as tacit support for the Sun family, and so the conversation stagnated. As tensions flared, and years passed, the princess became aware of her own significance and the power it afforded her. She would sometimes leverage her own life in order to secure her own autonomy. It was announced that she would marry in her own time, on her own terms, as she intended to become the first Empress. Legislation was written to support her claim.

When Emperor Da passed away almost thirty years later, she ascended to the throne. But in the years which followed, internal conflict escalated and the land began to fracture once more, many refusing to accept this new state of affairs, and some making their own claims to the Imperial throne. A new age of conflict had begun.

#rot3k#rot3k 14#Romance of the Three Kingdoms#koei#koei tecmo#three kingdoms#three kingdoms au#three kingdoms alternate history#alternate history#liu ji#cao cao#zhang fei#liu bei#guan yu#sima yi#han dynasty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Inbox Shenanigans || @paindealt || always accepting!

(in lieu of Wikia’s art)

I remember reading The Romance of the Three Kingdoms in my mother tongue when I was in elementary school (it was one of those things we learn, and I still recall other characters associated with him, predominantly Liu Bei and Zhang Fei. I definitely think that your inspiration for him really suits Kuai Liang, because so often, Guan Yu is portrayed as the noble and dignified oath brother for aforementioned two individuals who served both his long-time leader and friend Liu Bei and the enemy leader Cao Cao, and the way you portray him reflects the split light and dark, as he struggles to free from the Netherrealm’s grasp as some of our threads explore that.

For those who are unfamiliar with it; Guan Yu is a powerful general who is considered to be a hero in each kingdom. He meets and joins Liu Bei during the Yellow Turban Rebellion and follows his lord in the Allied Forces (I suppose Kuai Liang being the prominent protector of Earthrealm could be a good parallel). In most titles, he and his brothers duel Lu Bu while at Hu Lao Gate. Following Dong Zhuo's downfall, Guan Yu is eventually separated from his brothers and is often captured by Cao Cao (Quan Chi in this case?). Anyways, I certainly see the parallel between Guan Yu and Kuai Liang (the former being even revered as a deity), especially regarding their personalities; for Guan Yu is a stalwart general who firmly believes in justice and virtue. Normally calm and benign, he stands with an air of noble dignity and has respectful manners. A man who also excels in literary studies, he gains many admirers from each kingdom with his might and has earned the nickname "God of War/Army God". In the Asian script, he speaks in an archaic tone befitting a warrior. Kuai Liang has that defining timbre that befits a leader and also possesses virtuous qualities.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dynasty Warriors 4 Playstation 2 2003

#sun shangxiang#ssx#hu lao gate#musou#Dynasty Warriors#koei tecmo#Playstation 2#sony#2005#nostalgia#00s#2000s#ps2#retro gaming#sixth gen#gaming#video games#playstation#game gif#omega force#koei#three kingdoms#romance of the three kingdoms#rot3k#ps2 games#ps2 nostalgia#warriors#china#DW4#Dynasty Warriors 4

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Shin Sangoku Musou#Dynasty Warriors#Shin Sangoku Musou 8#Dynasty Warriors 9#Shin Sangoku Musou 8: Empires#Dynasty Warriors 9: Empires#Slash the Demon#Hulao Gate#Hu Lao Gate#MASA#originally from Dynasty Warriors 6#music musou#tune warriors

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mystical Qabalah: The Ayn, Vast Face, and Small Face

The Ayn The Mystical Qabalah describes the roots of the Tree of Life as an ultimate, negatively existent substratum of pure Being that is Self-conscious and all blissful. It is described as "negatively existent" in relation to the "positively-existent" four worlds of the Tree of Life. The three roots of the Tree are named: Ayn (lit. Nothing; pronounced "ai-n" as in 'nine'), Ayn Sof (lit. Without End, or Endless; pronounced "sof" as in 'sofa'), and Ayn Sof Or (lit. Endless Light, or Light of the Endless; pronounced "or" as in 'oar'). But these are only distinctions in human thought. The negatively existent Absolute Being, or shall we say "Mysterious Unknown at the Roots of All Things," alludes to a depth of consciousness beyond Name and Form, and beyond the finite and supernal aspects of the Tree of Life. Individual consciousness cannot usually sustain this experience at length. In fact, most souls do not return from the experience in the roots. Their shells of embodied existence (qlifoth) dissolve completely, and they pass from their physical sheath (i.e. die). In Qabalah, the negatively existent Absolute Being is also called the "NOT" (Heb. Lo, pronounced "lo" as in "below"). The experience of the "NOT" finds Its counterpart in every mystical tradition. The Sufis refer to the experience as fana 'l fana (fana means "extinction"). The Hindus call it nirvikalpa samadhi. The Buddhists call it nirvana, sunyata(emptiness), satori, and anuttara samyak sambodhi (full enlightenment). The Qur'an refers to the Mysterious Unknown by the same terms used in the Torah. In Arabic, the word for the NOT is "La": this is written , which is virtually identical to the Ezra letter Ayin. The shape of the Sinatic letter Ayin is also suggestive--it is a circle. Within qabalistic literature, the foundational concept of the negatively existent "NOT" is most strongly and directly portrayed in the Sifra Detzniyutha (Book of THAT Which is Concealed). The main body of the text begins: "The Book of THAT Which is Concealed is the book of the balancing in weight. Until NOT (Lo) existed as weight, NOT existed as seeing Face-to-Face. And the Earth (HaAretz) was nullified, And the Crowns of the Primordial Kings were found as NOT. Until the Head (Rosh), desired by all desires, Formed and communicated the Garments of Splendor. That weight arises from the place which is NOT Him. Those who exist as NOT are weighed in YH (Yah). In His body exists the weight. NOT unites, and NOT begins. In YH have they ascended; who NOT are, and are, and will be." The first chapter of Lao Tze's Tao-Te Ching opens with verses that address the Mysterious Unknown and Its two aspects: "1.1 The Tao that can be trodden is NOT, the enduring and unchanging Tao. The name that can be named is NOT, the enduring and unchanging name. 1.2 Conceived of as having no name, It is the originator of Heaven and Earth; conceived of as having a name, It is the Mother of all things. 1.4 Under these two aspects, It is really the same; but as development takes place, It receives the different names. Together we call them the Mystery. Where the Mystery is the deepest is the gate of all that is subtle and wonderful."

Vast Face In all mystical traditions, the "Mysterious Unknown at the Roots of All Things" is spoken of as having both inactive (impersonal) and active (personal aspects). These two aspects are called "Faces" in Qabalah. When referring to the inactive aspect, represented by the letter Ayin, the Zohar speaks of "Vast Face" (Arikh Anafin, also Arikh Afim). It is also known as Al (lit. upon), Shomer (Witness, Guardian), Atiqa (Hidden One), Supernal Israel, the Ancient of Days, and other Names found in the Sefer HaShmoth and the Torah. In the Sefer Yetzirah, the Ayin is alluded to as the "Organ of Nakedness." "Head" (Rosh), a word that occurs in the fifth line of the first verse above, is also a Name of Vast Face. Ayin means "eye," and in the Idra Rabba Qadusha it says: "This is the tradition: Were the Eye closed even for one moment, no thing could subsist. Therefore, It is called the Open Eye, the Holy Eye, the Excellent Eye, the Eye of Fate (mazal), the Eye which sleeps not nor slumbers, the Eye which is the Guardian of all things, the Eye which is the substance of all things." (Idra Rabba 136,137) Also, "And He Himself, the Most Ancient of Ancient Ones, is called Arikh Anafin, Vast Face, and He who is more external is called Ze'ir Anafin, or Small Face, in opposition to the Ancient Eternal Holy One, the Holy of Holy Ones." (Idra Rabba 54) And, "The Ancient One is hidden and concealed. Small Face is manifested and NOT manifested. The manifested is written in the letters. The NOT on its level is hidden in the letters, And He (Hu), the NOT, is settled in YH, The upper ones and the lower ones." (Sifra Detzniyutha 4) On the Tree, Vast Face is associated with the uppermost center at the crown of the head called Sefirah Crown/Above. Sefirah Crown/Above is a condition of Pure Being, a supernal station of superconsciousness that witnesses the singular modification "I AM" or simply "I." Even this singular modification disappears in the negatively existent roots of the Tree. The Sefer Yetzirah teaches that the spheres (Sefiroth) of the Tree emanate in pairs. Sefirah Crown/Above emanates with its polar opposite Sefirah Foundation/Below. The tension between these two Sefiroth manifests the descent of the Central Column of the Tree. The unmanifest Pure Being of Vast Face in Sefirah Crown/Above is reflected in the abysmal mirror of Sefirah Foundation/Below as veils of illusion appearing as planes of existence (see Diagram). These planes are unmanifest in the most sublime World of Atziluth (Emanation). The attributes of the Ayn are reflected in this mirror as the immense I-ness of Small Face as the Creator, Sustainer, and Destroyer of the universe. These attributes appear as finite in the consciousness of the embodied soul ensnared in the illusion of separation. The energy of consciousness of Small Face manifests the planes of existence in the lower three worlds of B'riyah (Creation), Yetzirah (Formation), and Asiyah (Making, Activity). Like Sefiroth Crown/Above and Foundation/Below, the two central Sefiroth Knowledge/First and Beauty/Last emanate as a pair, and represent two opposite stations in the consciousness of this Small Face I-ness. When the immense I-ness is centered in Sefirah Knowledge/First, It has the singular awareness that "I am Nothing;" when centered in Sefirah Beauty/Last that "I am All." The composition of the Tree and the four worlds are discussed in other pages of this site.

Small Face When referring to the active aspect of the NOT (Lo), the Zohar speaks of "Small Face" (Ze'ir Anafin, also Ze'ir Afim), represented by the letter Alef. Small Face is the power of the Ayn to superimpose billions of illusory universes (and their apparent sustenance and dissolution over time) upon the Vast Face of the Deep. The generation of universes is brought about by the balanced tension between Vast and Small Face, or between the Ayin and the manifest Alef of Unity. In the Sifra Detzniyutha, this tension in the Tree is called "weight" and the "balancing in weight." The relationship between Vast and Small Face is depicted in the Tree of Life ( see Diagram). Some of the most important Names of Small Face are YHVH , El (pronounced "ale," opposite of Lo), and Adonai (Lord, Master). Each universe has its own Small Face who-like a dreamer who knows he/she is dreaming-creates, sustains, and dissolves the Creation moment by moment by moment. Our sense of time is formed by our imperfect perception of the higher planes of existence. Our hopes for the future and our memories of a past (also created, sustained, and dissolved moment by moment) instill the impression that time is onflowing. To access the consciousness of Vast Face, one must renounce Small Face (in whose dream you are a creature) for release from the dream universe. Hence, it is "only through the Son (Small Face) that one can know the Father (Vast Face)."

Relationship Between Small and Vast Face in the Tree of Life The Small Face Alef is known as the "manifest Alef of Unity." Qabalists (and Sufis and Tantrikas) take the allusion of the alphabet quite literally, and see the universe as built from combinations and permutations of the letters that emanate from and return to the Alef of Unity. In Sanskrit, the Alef of Unity is called the Omkara . The Alef a of Unity/Omkara has unmanifest (Vast Face) and manifest (Small Face) aspects. As it is written: "By the First It created Elohim Eth (i.e. the twenty-two Hebrew letters in the Upper Worlds) the Heavens and VuhEth (i.e. the twenty-two letters in the Lower Worlds) the Earth." (Torah B'reshith 1:1)

In its unmanifest, inactive aspect in the roots of the Tree, the Alef a of Unity/Omkara is the undifferentiated source from which emanate the supernal Hebrew/Sanskrit letters in the uppermost center of the Tree of Life (Sefirah Crown/Above). At this point, the unmanifest letters stand alone and have not combined into Names. The letters vibrationally differentiate when the Alef of Unity becomes manifest in the throat Sefirah Knowledge/First. Each letter bears a characteristic root vibration or seed sound (Sans. bija). The Alef of Unity/Omkara is therefore called the "Seed of Seeds" (Bija of Bijas). Vocalization of the seed sounds is enabled by the vowels in the throat Sefirah Knowledge/First. The vowels also empower the undifferentiated Names in the supernal Sefirah Wisdom/East to become manifest with a characteristic vibrational signature in the World of Creation (see Diagram). The Sinatic Alef is written by scribing the vertical line first (Central Column), from the top point (Sefirah Crown/Above) downwards. Then the horizontal line is scribed from right to left (Column of the Right). Finally, the diagonal line is drawn from the left end-point of the horizontal line upward to the right across the vertical stroke (Column of the Left). The Columns of the Left and Right are opposite reflections in the clear mirror of the Central Column. In the Etz HaChayyim (Tree of Life), the vertical stroke is called the Line of Light (Kav). The Alif in Arabic uses only this vertical stroke, reflected in the principal Working Tree in the Sufi tradition that only uses the Central Column. The Cross is the Christian Alef +, with the diagonal stroke of the Column of the Left removed.

Evolution of the Alef of Unity The second line of the first verse of the Sifra Detzniyutha (Book of THAT Which is Concealed) says, "Until NOT (Lo) existed as weight, NOT existed as seeing Face-to-Face." This is the condition where Small Face is turned toward Vast Face and therefore is not active in manifesting a universe. We find this condition further described: "And when Ze'ir Anafin looks back upon Him (Arikh Anafin), all the inferiors are restored in order, and His Countenance is extended and made more vast at that time. But not for all time is it vast like unto the countenance of the More Ancient One." (Idra Rabba 55) The "weight" referred to in the first verse of the Sifra Detzniyutha is the single combination of all the Sefiroth on the Tree. Weights are the individual Sefirah. The Primordial Kings allude to the unmanifest "Alef Worlds" or witness states of Vast Face in Sefirah Crown/Above. The "Crowns of the Primordial Kings" are the Sefiroth in the supernal World of Atziluth (Emanation), and the "Garments of Splendor" are the manifest Sefiroth in the successive three worlds. In the Torah, "Earth" (Aretz) is a synonym for the Sefirah Malkuth/Kingdom. Hence, the phrase "And the Earth was nullified" infers that matter was absorbed and disappeared. The Sifra Detzniyutha, and in smaller measure the Idra Rabba Qadusha (Greater Holy Assembly) and Idra Zuta Qadusha (Lesser Holy Assembly), also contain some wonderful verses pertaining to the allusions of the "beards" of the two Faces. The hairs of the beards are the Atziluthic letters convoluting into Divine Names in the World of Creation. The beards are said to each have nine formations i.e. strands manifest in Small Face, with four more inside the Skull of Vast Face as the Hidden Brain. The strands of the Names of Vast Face (see Diagram) generally convolute to the Atziluthic letter Ayin, and those of Small Face (see Diagram), to the Atziluthic letter Alef. "The Beard of Faith, NOT (al), is mentioned because it is the most precious of all. It egresses from the ears round about the face, The white locks [strands of Names] ascending and descending, Separating into thirteen of that most splendid of splendors." (Sifra Detzniyutha 2) "The formations of the Beard are found to be thirteen, That is the upper one [Vast Face]. In the lower one [Small Face] they are beheld in nine." (Sifra Detzniyutha 3) "Each hair is said to be the breaking of the hidden fountains that issue forth from the Hidden Brain [Vast Face]." (Idra Rabba 74) "And all those threads [i.e. convoluting Names] go out from the Hidden Brain and are disposed in the weights [i.e. Sefiroth]." (Idra Zuta 63)

Conclusion In speaking of two "Faces," it must always be remembered that we are talking about an absolute unity that is only differentiated by human thought, and can only be directly experienced in higher states of consciousness. Generally, mystical traditions are very fluid and flexible in assigning gender to Vast and Small Face. In most mystical traditions, both Vast and Small Face can take either the masculine or the feminine gender. Within a particular tradition, one may find Vast Face referred to in the masculine and Small Face in the feminine, and/or vice versa. The two Faces may also be both masculine or both feminine. In the Qabalah, for instance, we find many references to the white-haired ancient father and the raven-haired youthful king. We also find the ancient mother and the maiden Shekhinah. In virtually all traditions, we can also find many impersonal names and references to Vast Face that are neither masculine nor feminine. However, Small Face, as the active principle, is always named and referred to personally as masculine and feminine. It is cogent to note that the Torah commands us to "Honor thy father and thy mother." While this is commonly understood to refer to one's earthly parents, its higher meaning enjoins us to honor our Divine Father and Mother. The great and beloved nineteenth century Bengali saint Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa offered several useful analogies to the relation between Vast and Small Face (static and active aspects of the Divine). These included the relation between milk and its whiteness, a gem and its sparkle, a flame and its power to burn, and the Sun and its rays. An old Vedic analogy compares God to a spider that spins a web from and retrieves it back into its own body. An analogy in Qabalah cites the relationship between the letters of the alphabet and the vowels: without the vowels (active aspect), the letters (inactive aspect) cannot be pronounced. In the Tantra, it is said that "without the vowels, Shiva's bones can't dance." Another analogy that illustrates the nature and relation of the two Faces is presented in the parable of the rope and the snake: "A man was walking down a road in the country at dusk. Just as he turned a corner, he encountered what appeared to be a large snake. His whole body gripped with fear, and without thought, he jumped back to avoid getting bitten. As he looked at the snake, he noticed that it wasn't moving. He picked up a rock and threw it at the snake, and still the snake didn't move. He thought, 'Perhaps the snake is dead.' This thought diminished his fear, and he inched closer to the snake to get a better look. As he neared the snake, he was amazed and relieved to find out that it wasn't in fact a snake at all: it was a rope that he mistook for a snake." In this story, there had to be a rope in the first place for the man to have mistaken it for a snake. The "snakiness" was a superimposition upon the rope that only existed in the man's mind. Such is the nature of the Creation, which is a collective illusion. The "snakiness" of Small Face is an illusion superimposed upon the reality of the "rope" of Vast Face. This illusion of a "difference within Itself" is a play of the Divine arising from an unfathomable whim.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Deities

Part 7 // I could find very little on the Chinese Deities specifically. If you know any good places to find info please let me know.

Ba-Ja - Scarecrow deity of Defence

---

Cai-Shen - God of Wealth

Can-Nu - Goddess of Silkworms

Chang-E - Goddess of the Moon

Cheng-Huang - City God of Protection

Chuang-Kong - Goddess of the Bedroom

---

Di-Jun - Supreme God

Di-Kang-Wang - God of Ghosts and the Underworld

Du-Shi-Wang - God of the Underworld

---

Erh-Lang - God of Protection from Evil

Er-Lang-Shen - God of Truth

---

Fan-Kui - God of Butchers

Fei-Lian - God of the Wind

Fo-Hi - Supreme Ruler God

Fu-Xi - God of Invention and Creativity

Fu-Xing - God of Agriculture

---

Gao-Yao - God of Justice

Gong-Detian - Goddess of Good Fortune

Guan-Yin - Goddess of Mercy

Guan-Yu - God of Wealth

Gun - God of the Earth

Guo-Ziyi - God of Wealth and Happiness

---

He-Bo - God of the Yellow River

He-Xiangu - Goddess of Women and Femininity

Hou-Ji - God of Abundant Harvest

Hsi-Wang-Mu - Great Shamanic Goddess

Huang-Di - Yellow God

Hu-Jingde - God of Doors and Security

Hun-Dun - God of Creation and Chaos

---

Jun-Di - Goddess of Light

---

Kuan-Ti - God of War and Divination

Kui-Xing - God of Literature

---

Lao-Jun - Supreme God

Lei-Gong - God of Thunder

Lei-Zu - Goddess of Silk

Ling-Bao-Tian-Song - Supreme God

Li-Jing - God of the Heavens and it’s Gates

Li-Tieguai - God of Sickness and Disease

Lu-Ban - God of Builders

Lu-Dongbin - God of Poetry and Education

Lui-Hai - God of Wealth

Lu-Xing - God of Wealth and Status

---

Meng-Po - Goddess of the Underworld and Reincarnation

Men-Shen - God Duo of Doors and Security

Mi-Lo-Fo - God of the Household and Prosperity

Monkey - God of Mischief

Mu-Gong - God of Immortality

---

Nezha - God of Protection

Nu-Gua - Creator Goddess of Mankind

---

Pan-Gu - Creator God

Ping-Deng-Wang - God of the Iron Web

---

Roustem - God of Silk

---

Sao-Ts'ing-Niang - Goddess of Clouds

San-Guan - Triple Gods of Heaven

San-Qing - Triple Supreme Gods

San-Xing - Triple Gods of Good Fortune

Shen-Nung - God of Medicine

Shou-Xing - God of Longevity

Sien-Tsang - Goddess of Silk

Song-Di-Wang - God of the Upside-Down Prison

Song-Jiang - God of Thieves

Sui-Ren - God of Cooking

Sun-Bin - Door God

---

Tai-Shan-Wang - God of the Dead

Tai-Sui-Xing - God of Time

Tai-Yi - God of the Skies

Tian-Mu - Goddess of Lightening

Tu-Di-Gong - God of Fortunes and Virtues

---

Qi-Gu - Goddess of the Toilet

Qin-Guang-Wang - God of the First Court of Feng-Du

Qin-Shubao - God of Doors

Qi-Yu - God of Rain

Qu-Jiang-Wang - Ruler of Hell

---

Wei-Cheng - God of Security

Wen-Chang - God of Literature

Wu-Guan-Wang - Ruler of Lakes

---

Yen-Lo-Wang - God of the Dead

Yi-Di - God of Wine

Yu-Qiang - God of the Seas and Ocean Winds

Yun-Dun - Weather God

Yu-Zu - God of the Rains

---

Xiao-Wu - God of Prisons

Xi-He - Goddess of Light

Xi-She - Goddess of Beauty

Xi-Wangmu - Great Shamanic Goddess

Xuan-Wenhua - God of Hair and Beauty

---

Yi - God of Archery

Yuan-Shi-Tian-Zong - God of the Universe

Yu-Huang - Ruler of Heaven and Earth

---

Zao-Jun - God of the Hearth

Zhang-Fei - God of Doors

Zhang-Xian - God of Unborn Infants and Male Children

Zhi-Nu - Goddess of Weaving

Zhi-Songzi - God of Rain

Zhou-Wang - God of Sodomy and Discord

Zhuang-Lun-Wang - God of the Underworld

Zhu-Rong - God of Fire

Zhu-Yi - God of Literature

Zi-Gu - Goddess of Toilets

---

Sources:

https://www.smitefire.com/smite/forum/god-item-ideas/list-of-egypt-greek-chinese-hindu-norse-mayan-amp-roman-deities-3332

http://www.godchecker.com/pantheon/chinese-mythology.php?list-gods-names

http://godfinder.org

http://Wikipedia.com

#witch#witchcraft#deities#chinese#chinese culture#chinese traditions#chinese deities#chinese gods#gods and goddesses#pagan#paganism#witchblr#witchblog#witchy

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

They’re Making A Dynasty Warriors Movie!?

First off, in case you can’t tell, I’m very excited about this! I’ve been a big fan of the Dynasty Warriors games since my step-brother foolishly leant me his copy of Dynasty Warriors 2 and very nearly never got it back. I’m now one of those people who ends up buying Empires and Xtreme Legends even though I already have the original game… So yes, very excited. As such, this has been occupying a large space in my brain for the past week and will likely continue to do so until the movie comes out. Fortunately, that’s tomorrow, or I would probably be trying to find somewhere to watch the original Taiwanese version right now… Patience isn’t my strong suit.

So, why am I so curious? Well for starters, the movie is only 2 hours long (just under, technically speaking) so I think it’s safe to say it would be impossible for it to be covering the whole story (my copy is three books, and we know how that worked out for Lord of the Rings!) It’s based on the games though, not the book, so that trims it down a little bit. The banner image on Netflix shows Liu Bei, Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, so that suggests it’s probably near the beginning, but that still leaves us with quite a lot of story, especially as the games have always been about playing as all three kingdoms rather than favouring just Shu. In which case, are we starting with the Yellow Turban Rebellion again? Given that the Red Cliffs movie is four hours long and centred on just one battle, I can’t imagine we’d get very far past that though unless it’s moving very quickly (and are they really going miss out on the opportunity to include Lu Bu or Zhao Yun?) Soooo Hu Lao Gate then?

I think this might be our best bet. It’s got a strong focus on the three brothers, it includes Lu Bu, and it’s one of the signature battles of the games. “Don’t pursue Lu Bu!” anyone? We’re still the Allied Forces at this point too, so that means we get to keep the balance of kingdom focus in check too. Also, as some of the games split Hu Lao Gate and Si Shui Gate into separate stages, that gives us a bit of leeway of shifting focus too.

So yeah, my money is on Hu Lao Gate. I know I could probably have watched the trailer and found out that way, but this is more fun, right? You can all laugh at me this way when it turns out to be Fan Castle or something (though I’ll be too busy sobbing about Fan Castle to notice).

Also, if it really does cover just one battle (two chapters of the book) does this mean we might get more at some point? Could my heart even handle a dramatic, movie version of Wu Zhang Plains…? Hopefully one day I’ll get the chance to find out!

#not a meme#dynasty warriors#dynasty warriors movie#blog of the Three Kingdoms#will review when I've seen it#I'm super hyped

0 notes

Note

With no Dong Zhuo and Diao Chan and Sun Jian in Others I'm assuming you would use the Historical Campaign against Dong Zhuo not the fictional Hu Lao Gate?

Absolutely. I find the reality far more interesting.

And given how short Dong Zhuo’s presence in the overall narrative actually is, I don’t think there’s any need for him to be a playable character. An important NPC, sure, but he just wasn’t there very long.

1 note

·

View note