#how exactly are you going to convince people not to engage with HP in any way because it empowers jkr

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'Here's a 4chan post about how liberals that like Harry Potter in current year see the world.'- post engaged with on here by people on the broader left for some reason.

#people forgetting the right wing exists again and also hates liberals#but even if people on 4chan have made good points occassionally (i didnt bother reading it but its possible)#how exactly are you going to convince people not to engage with HP in any way because it empowers jkr#using fucking 4chan?!#honestly there are so many left wing people on here with the weirdest blind spot when it comes to 4chan#the memes they use...the weird way they give it a pass at times like this#if u can avoid HP on your massive muscular principles but 4chan is ok then what state are your principles in

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

ur death of the author post reminds me of a recent headline i saw about a tiktoker stripping jkrs cover from the title cover and reselling the books for $1000+ with new covers which - that can technically be legal But its just kinda hysterical to me bc. the persons whole point was “now u can read hp wo engaging w jkr” which to me is just… not how that works? the whole thing feels performative and not exactly insulting to jkr if thats what u were going for since ur,,, literally paying a grand just to read her books wo her name on it

on another note, i really liked how you said “if we adhere to death of the author, then wolfstar as a couple is not any less real or valid than any other reading, because what matters is that readers are picking up on homoerotic subtext and drawing meaning from it--whether it was included intentionally or not” very well put! honestly i remember a time in older hp days where people were so convinced of wolfstar being “real” that it was practically canon we all thought she was trying sooo hard to hint to us that theyre a couple wo getting into trouble w her publishing agency or smthn lmfaodjfjkshhjdjsh

oh god yeah that's....well look no hate to that person because i think bookbinding is a very impressive skill and well worth fair compensation for the time and effort. and if someone has $1000+ and that's what they want to spend it on. well. i mean. well. i mean buying the books in the first place is still putting some money into jkr's pockets isn't it. unless these books are all old donated or resold copies or something?? like if people are sending in their own hp books??

but yeah um. that seems a little silly to me. as i said in my little jkr death of the author post i simply do not think there is any engaging with harry potter in which that woman can just be completely stripped away. i do think it's possible to engage without giving her any money and while keeping everything outside the profit economy, which personally is the only way i think hp should be engaged with at this point. but her influence is still very much steeped within the pages and as i said in my post i think it's important to acknowledge where these books are coming from so that we can be mindful of the biases that permeate the story.

anyway! to ur point about wolfstar--that's super interesting! i was still a young kid while the hp books were being published, so i was not at all involved in the fandom at that point and i find it really interesting to hear about the history and what it was like when the series was first coming out. i definitely understand the urge to want like...some validity coming from the creator of a story, and i've experienced firsthand how it can be meaningful to have creators come out and say "yeah that's not just subtext," but at the end of the day whether or not the person writing a story intends to imbue the text with certain meanings does not make the meanings readers draw from it any more or less real, imo! like sorry but regardless of whatever jkr was trying to do...those men are gay. always have been always will be <3

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reader profile: smozark

Next up in reader profiles we have the one, the only, the incredible @smozark. I must admit to fangirling when smo agreed to be profiled; she is an incredibly supportive reader who I have seen *all* over the fandom and have been truly wowed by how engaged she is in this fandom. Without further ado, I present to you @smozark!

Location: East Coast, United States Hogwarts House: Slytherdore Pronouns: she/her/hers

When did you start reading Dramione? How did you originally find fics to read? I think it was early to mid 2019-ish? I got started because I thought it was cool that Emma Watson and Tom Felton are friends. I read the word "Dramione," Googled it, and found “We Learned the Sea” and “Isolation.” I discovered AO3 shortly after and found authors like @provocative-envy and @lovesbitca8 and @indreamsink and I was hooked.

How have you gotten more involved in the Dramione community? What platforms/websites have you participated in, and which do you like? I got involved with the community by posting comments!! It was so much fun to interact that way, so when I figured out what Discord was I joined and started chatting there. I also really love the artists in this community and enjoy commissioning works when I can. I'm only on AO3, tumblr, and Discord. I am actually not a huge social media fan, so I am fairly passive and lurker-like on tumblr. I'm much more comfortable on Discord.

Tell us about any reading preferences or practices! I read daily on my phone. I've been known to block time on my work calendar to catch a chapter drop. [Editor’s note: GOALS] Honestly, this fandom was my refuge in 2020. I feel no shame in admitting that I escaped the dumpster fire by immersing myself in other people's creativity. I'm so grateful to authors who can make their ideas into published works so we can get some respite.

Do you like to leave comments? If so, what is your advice for leaving comments? YES. As often as I feel moved to do so. My advice is to comment whenever you can, but don't feel bad if you don't want to. Writers aren't obligated to publish, you aren't obligated to comment. That said, I will also advise that if you comment, make it positive. Why add needless negative to the world? I have read hundreds of fics. Some are really tough to get through. Maybe the story is slow, maybe the grammar is bad, maybe there are some characterizations I'm uncomfortable with. I will NEVER make a comment about any of that. If I'm not beta-ing, it's not my place. If I can't find anything to compliment, I close the tab and move on. That's rare, because there's always something wonderful. Even a story with poor grammar and usage can have a really cool story or interesting characters. So find what you like and tell the author about it! Unless you don't feel like it.

What is your all-time favorite fic you’ve read? Oh gosh, what a cruel question. I have no idea how to even answer. They are all so different!! Over/Under by @provocative-envy is my favorite in all of HP fandom. The entire summer camp collection, if I'm honest. My favorite Dramione ….. Gaaaahhhhhhh the pressure!!!!! Ummm. I'm going to shamelessly cheat and say my fave one-shot is My Brown-Eyed Girl by @pacific-rimbaud and my top 5 favorite finished multi-chaps right now are the Wait and Hope series by @mightbewriting (more cheating), Remain Nameless by @heyjude19-writing, A Thing With[out] Feathers by @senlinyu, and Anchors in a Storm by @inadaze22, and Protective Custody by @colubrina. I'm cutting myself off there. If I keep going or add WIPs, we'll be here all day!

What fic gave you the most feels? What You Think Is Right by @icepower55. Hands down. Didn't even have to think. It is a raw, unflinching, brutally honest look at a broken marriage. It was incredibly authentic and helped me process some of my baggage. It's just gorgeous. @icepower55 is so talented, and she has a great beta team!! I'm writing this the day the last chapter posted, so go binge if you haven't already.

Who is your favorite side character from any Dramione fic? Another impossible question!! How can I pick between Theo or Pansy from Wait and Hope? Grix from Love and Other Historical Accidents or Jonathan Gable from One and Done? Ginny or Sasha from Remain Nameless? Mippy or Blaise from Rights and Wrongs?? Charlie or Hamish from Universal Truths? You don't. You shamelessly cheat some more and list them all!!! (Please never make me play FMK. I'll spontaneously combust.)

Tell us a fun fact about yourself! I worked at a butcher shop for a while. I hated my first job out of college, but it was the recession so I couldn't exactly quit. I convinced a local artisan market to let me apprentice after work. They paid me in meat. It was awesome.

Thank you so much, smozark!! A true fangirl moment right here! Thanks for sharing with us, and please accept my apologies for the cruel questions.

Be like @smozark! Put a hold on your calendar when new chapters drop (I will repeat: GOALS) and also sign up for the Dramione Comment Fest! Sign-ups close ***TOMORROW*** aka Saturday, February 6, 2021. Check out the rules here and sign up here. We hope you can join us!

#dramione comment fest#dramione#dramione fanfic#dramione fest#reader profile#we heart readers#we heart commenters#we heart smozark#smozark is reader goals#calendar holds omg what genius

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

For A Greater Good Fun Facts and Self Assesment (spoilers)

Long Post

What worked and what didn’t:

I think the overall structure worked pretty well. The most difficult part was, with the plot and subplot already created, scattering all those ideas throughout the text in such a way that at least made some sense. I regret not writing more about Mer Yankelevich, I feel like the crumbs I left on the way were not enough; in my attempt to make it subtle it lacked information about her. The key piece was of course her sister, and I should have introduced her sooner.

MC’s evolution. I feel like Kate’s learnt a lot with this experience (I’m not only referring to the Deathly Hallows or Grindelwald) When it started, she was very discreet and kept a low profile, not knowing what to do really, not taking more risks than necessary. And then she ended poisoned and splinching just to protect a document she thought was important. I hope her evolution is noticeable for the reader.

Worldbuilding. Grabbing HP concepts that were forgotten and full of potential, plus a dash of original ideas from me and blending them with muggle features was my absolute favourite part of the process.

On that note, I dont own these concepts: Durmstrang, Igor Karkarov, Nerida Vulchanova, umbrella flowers, fanged geraniums, billywigs, Appare Vestigium, glow-worms, trick wand, chamaleon ghouls,

If you’ve read the fic and thought: “everything happened so fast” or got a general odd feeling about the timeline it's because I made a series of monumental mistakes: setting a chapter limit, telling you about it and then tried to stick to it. At first the idea sounded nice: this is my first “big” story with complicated components. I should (and I did) do an outline of what I want to happen in each chapter and stick to it methodically so I don't forget what's happening or lose track of the plot. Well...it kind of backfired. So I wrote the first 3 chapters and at that point I thought “okay everything is going as planned, I’m going to put it out there”, bam, instantly cursed. After that it got ridiculously difficult to make the story that I wanted. Why? I needed chapter space that I convinced myself I couldn’t add. Dumb.

The major consequence of this was the lack of character backgrounds. It started out good, but as I kept writing and publishing I realised that I missed some great opportunities to make amazing ocs. That’s Corentin’s fault in a way: he wasn't going to be a major character, really, just a piece to help Kate a bit. But we all fell in love with him so what was I supposed to do? Also, Sheyi Mawut owns my heart and he got just a bit of spotlight. A shame.

I wish I had written more about them, but I think I wasn’t ready just yet to make it even more complicated.I just wanted to prove I could concoct a mystery plot and now that I know I can manage a fair amount of information I think I can take it a step further and deepen new ocs a little bit more.

I’m thinking about the datura series and I know why I got blocked and tired of writing it; it wasnt going anywhere because I wasnt prepared, and I didn’t do the months of outlines and planning that I did with this one. I’ll come back to the datura story one day, subjecting it to a sever rewrite. The ideas are there, I just need to be organised.

Although the chapter limit was problematic it was also a good exercise of managing space and deciding which things were unnecessary for the story. I dont think there’s any filler chapters, perhaps the last ones, but there is important information there too so... However this sentence from the blog wordsandstuff reassured me (and I think I did a good job at that?)

If you set out to write 10 parts and you write a fantastic story in 8, you haven’t failed and it’s not too rushed. Concise writing is an underrated talent. Focus on how effectively you engage the reader, not for how long.

I spent more than year writing this! When I started, I had a lot of ideas, I wrote the last two chapters then the first 3 and I really thought it was going to be that way with the rest of the story... okay... lesson learnt. #humbled

Other thoughts:

I received a couple of comments on ao3 that said that they were pleasantly surprised. Maybe I should change the tags because they are misleading? Clearly this wasnt what people were looking for lol.

One particular comment stood out to me and quoting it said: “You did not choose the easy way with a fiction with so few characters from the fandom.” And I’ve been thinking about this since I read it. It didn’t occur to me that there were few mystery fics (maybe I should write more things like that? Maybe throwing some power couple detective work 👀 ) In any case, I’m glad I contributed with something different to the fandom, and the fact that the Charlie bits are very scarce but people who read it still liked it is really flattering.

I wanted to make sure that all the characters had strengths and flaws, I didnt want to severus-snape them so maybe I overdid it with that bit of introspection kate does at the end...

Also, I did the kiss and fade thing twice to mention sex. I know some people dont like that but since it wasnt the point of the story and I havent done research on how to write sex scenes I didnt include them. I have that on my “to learn” list.

Conclusions:

Writing the whole thing was incredible. It's my first ‘big�� project and its not a great work (there are some things I wish I did better, thats what you get when you are an agatha christie wannabe) and not writing more character backgrounds will haunt me to this day, but I think it's at least good for a first series and I’m proud of it. I loved spending hours doing research and trying to piece together this puzzle. And of course I’m not an expert and I dont want to sound pretentious (like this is my first story) but if you are planning to write this type of genre I can be another source of tips and tricks for you.

If I read the story after a while and I dont cringe, I would call that a success.

FUN? FACTS!

Bakunawa really belongs to Filippines mythology

Snapdragons have different meanings, one of them being: “grace under pressure or inner strength in trying circumstances”

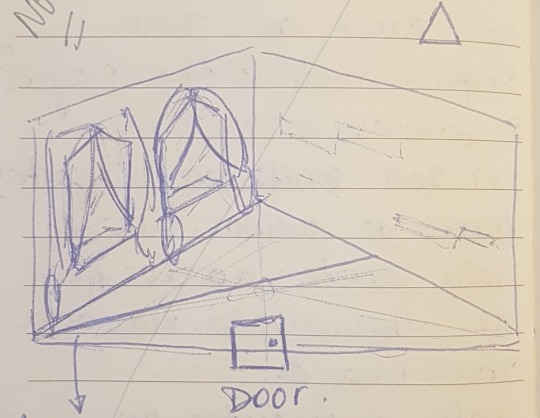

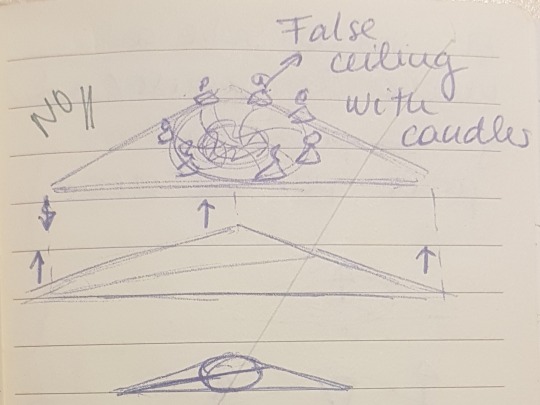

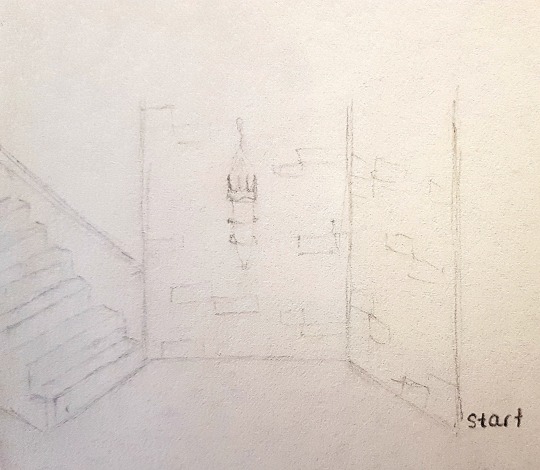

The entrance to Grindelwald’s room was going to be in the duelling classroom, strangely shaped as a triangle. I had this system where one of the round candle lamps descended and lined up with a line on the floor (serving as separation for duels) it created the Deathly Hallows symbol. I couldn’t make that work because it wouldn't make any sense for Nerida Vulchanova to shape a room like that. Here are some sketches:

Lucius Malfoy was going to appear as the Ministry employee that goes to Durmstrang, but after revising the events of the OoP I realised it was impossible.

Kent Jorgensen was going to be around Kate’s age and the charms teacher and he would have a small crush on her. After seeing some pics of Pen Medina, I rewrote the character completely.

The series was going to be 6 chapters long (I’m glad I decided not to) one for each month. The chapter names were ridiculous: January of Beginnings, February of reputation, March of Students, April of Discoveries, May I? and June of Endings. #tragic

The Dolohov family was going to be a part of the plot but I had to erase that part because it was unlocking another layer of complexity that I just couldnt handle.

I dont remember exactly the chapter but I got really confused with the names Rhode and Hodges and there’s one chapter where I accidentally mixed them (I corrected it I think), but for a while I could stop calling Rhode, Hodges, and vice versa lmao

Here are some sketches that helped me describe and imagine things

Thank you for accompany me in this journey, especially if you endured the process with me lmao. You’ve been here for over A YEAR! <3 Mindblowing

Also I’d love to know your opinions about the way you read the story, I mean, I know some people read it as I published, and some other readers found the story already finished, what are the differences? Should I stop the updating system and drop a story all at once? I know it is difficult to keep up with a complex story if there’s a lot of weekly or monthly gaps between the chapters, so I wanted to know.

Sending you a virtual hug 💜💜

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for the reply to that post and sorry if I made you feel like an asshole, that wasn't the aim at all! I'm glad we're good. As for hurt/comfort and catharsis... I mean, yes, I think that's exactly the function it serves. One of the things that I find super interesting about fan fic as a literary mode is the sort of unashamed emotional functionality of it? Things like the ability to search AO3 by tags, or blogs like SPN Storyfinders where you ask for a certain thing and people make (1/2)

suggestions, both of which permit you to narrow down to just exactly the right sort of fic that you’re looking for. That’s not to say that lots of fic isn’t acting in the same way as other literary modes or genres, like e.g. people might read and write horror fic for exactly the same reasons and in the same way that they’d interact with horror in the form of novels or TV, but there are also definitely areas of difference. (2/3)

For instance the porn content of fan fic is obviously higher than mainstream literature and I think there’s a really clear analogy between PWP and hurt/comfort in that they’re both about satisfying sort of iddy emotional-physical needs. (3/3 and sorry for the multi-asks, blame Tumblr!!)

The function of fanfiction is really interesting, you’re right. I think there’s probably a few schools of thought there, but if I had to run it down in a list-like format, I’d say that there’s a few different modes of creation happening:

1) Emotional/Id-fic, as you say–fic that’s looking to explore a very specific kind of emotion, for cathartic purposes both on the writer and readers’ parts.

2) Writing to write–and by that I mean, to explore character/tell a story as a thing in itself, absent the need for catharsis.

(There are probably lots more, but if we keep to very broad categories, that’s what occurs to me.)

On the first category, I think you’re absolutely right that PWP/porn and h/c and heavy angst and candyfloss-fluff all perform roughly the same function–they’re pinging some deep emotional/physical need. H/C is emotion-porn, as much as PWP is properly porn, or a long angst-fic is sadness porn. Now, personally, I think there’s nothing wrong with porn. Generally, porn is defined as something that lacks substance–but hell, who needs substance all the time. Not every meal can be whole-wheat bread and brussels sprouts; sometimes you need a taco and a chocolate bar. Sometimes you might just need a fic where Sam plays with puppies. Fair enough.

On the second category, I guess I’d call that a more–literary approach, for lack of a better term. As an example I’d use a fic by one of our classic authors in fandom: astolat’s SPN/HP crossover, Old Country. Just looking at the text, not knowing her mind while writing it, I’d call this a more ‘literary’ approach because it seems that the fic’s primary function is to explore an idea: what would it be, if Sam and Dean went to Hogwarts? Certainly there are what could be considered ‘cathartic’ moments in the vein of the first category–there is sex, and there’s a bit of dark!Sam, and Dean is saved from Hell. All things that take place in catharsis!fic, and yet it doesn’t feel like one of those.

The difference, I think, between the two types is how the writer (and reader) emotionally engage with the text. In type the first, the emotional goal is the main one. To get the reader (or writer) off, whether that be physically via a wank or emotionally via a cry or a squee or whatever. In the second, the more literary mode of writing is the goal–which, I’d say, is convincing the reader of the argument the text proposes, whether that’s a romance or a horror story or an adventure, or whatever.

This is really the place where fic diverges from traditional writing, I think. Fic tends to assume that the reader is already convinced. The tag says Wincest Hurt/Comfort, and so the reader enters with that mindset and doesn’t care about the realism of two brothers hooking up, or why they would, or why one would let the other baby him, or whatever–all of that is assumed by the tag. A traditionally published piece that featured homosexual incest, in which one brother has had a leg blown off and the other takes care of him (sexily), would have to put in a lot of work to make the reader first buy the conceit, and then build the argument that such a thing could work, and by painstaking logic force the reader to believe that Sam and Dean Winchester were in love. (Unless it were badly written, but that ought to go without saying.)

Personally, as a reader (and writer), most of the time I prefer the type the second. Maybe it’s the academic training that got beaten into my head, maybe it’s because I’m a snob–who knows. I enjoy the more complex, difficult characterizations and plots that tend to come with the ‘literary’ mode, as opposed to the sometimes more facile/simplistic characterizations that tend to come with catharsis!fic. (Note, I’m not saying that it’s simplistic all the time–it’s just a tendency.) I’m also not going to pretend like I only go for lit!fic–after watching Civil War, I definitely went on a round of reading all kinds of Tony-positive!fic, which often turned into Steve-negative!fic, just because I was so annoyed at how the characterization of Cap went. But I also wouldn’t ever say that those fics were good or canon-based, because the characterizations were so simplistic (Tony good! Steve mean!) as to be preposterous. Still–it gave a kind of catharsis.

The ‘problem’ with catharsis!fic, from a lit!fic point of view, is that in pursuing one emotional goal so steadily, all of the nuance tends to drop away. If as a Dean!girl I think that Sam was cruel to go to Stanford, then I might write a fic where Sam is a perfectly horrid shit as a teenager, and Poor Sainted Dean is basically abused and sidelined by him and still cries bitter tears when Sam walks out. If as a Sam!girl I think Dean was too harsh during the demon blood years, then I might write a fic where Dean was nothing but cruel during that whole time, and Poor Sainted Sam really never had a choice but to fall into Ruby’s embracing arms. And hell, I’m free to do either. But both of those ignore the nuance of both situations–it may have been cruel of Sam to leave, but he deserves his own life/Dean was harsh sometimes, but he also flat-out offered to help Sam with it any way he could–and by failing to take the characters’ multidimensionality into account, I’d say that they’re badly characterized, and I’m disappointed after reading them. Yet–someone who specifically craves the catharsis engendered by either of those situations would really enjoy those fics, and recommend them as good.

And so here, as always, we fall into the trap of what analyzing the characters means to the individual. Do we analyze clear-eyed and logically? How can we tell? If Dean is my favorite character, am I capable of seeing his flaws, and not reacting poorly when other characters engage with him in a negative way? Well, who’s to say. And who’s to say that it matters? If you’re engaging with fic in a purely emotional/cathartic way as a Dean!girl, then it may not matter to you that Sam is being demonized because your cathartic needs are being met.

It’s really impossible to see, from the outside (and even from the inside), what the biases are, and whether they’re affecting the analysis/writing. And, therefore, it’s nearly impossible to self-identify: am I writing pure catharsis!fic? Am I writing ‘logical’ fic? Am I engaging with it as canon or as fanon? If we could clear up these sorts of things, we’d probably have a much less fractious time here on tumblr. (And, for me, I’d have a much easier time finding fic to read.)

So… there’s an essay, haha.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoooooo boy

Feeling really intimidated by the diplomacy system I’m trying to work up for Hendrick.

What moving parts are we talking about having? Perhaps looking at the cogs individually will give a better idea of how to fit them together, and how many of each I need to make the thing work.

Enemies will sometimes need to have attached skill challenges. One prospect is to have a named enemy card - The game will need monster tokens for all the enemies anyway, so this isn’t a board space issue though it is a demand for more parts.

One partial solution to this is to have the Ally information on the back of the same cards. Allies aren’t shuffled into your deck, so they don’t need a standard card-back. The card back for the deadly spear-maiden Undyne could be the stats she had when she was your enemy.

So that’s one thing that would have to exist: Cards that on one side are the stats for the enemy and the skill challenge required to stop them, and on the other side are the bonuses you get from friendship with allies.

Second: Are these all different skill challenges, or is there a standard thing? If it’s all one stat you get into this problem where the player can (and will) focus their efforts 100% into Social, which is a detriment to both their other skill checks and their combat deck. The former seems like hey, your call, but the latter is a side-effect and feels kind of meta in a way that I don’t think people will like. Ah! I know the solution to this shape of problem: If I limit the amount of specialization possible, the player still gets to make choices to lean into social but can’t actually neglect the other options entirely. (Example in D&D: You can be a rogue nobleman and max out your Charisma and use your Expertise power to double your proficiency bonuses in Charisma checks, and this’ll give you something ridiculous like +9 to Diplomacy at level 1, but you’ll still have enough skill slots to be good at a few other things and you’ll still get Sneak Attack just as a class feature) To me this suggests a resource specific to this kind of challenge: Cards that specifically state they allow you to place skills onto enemy cards. There’s a temptation to include a few psychological status effects - Scared, Charmed, Confused - as part of the skill check (for instance if you want to browbeat someone into quitting the fight without killing them you need some Social successes but also either the Scared or Injured status, with Injured being the state of being at half health or lower). This would allow Hendrick to use his social cards against basically all enemies, not just the ones he can skill-challenge into submission.

Third: My general sense is that Hendrick must face these skill challenges alone. That he can bring his fellow heroes in for aid but that, mechanically, the non-Hendrick players can’t initiate diplomacy. The main reason for this is logistical: I don’t want on the one hand for players to “social bum-rush” each possible ally - Perhaps the solution there isn’t to limit it to Hendrick but to limit it to 1/round regardless of who engages? - and don’t want on the other hand for it to be too hard for Hendrick to do on his own, as a personal mini-game chatting up the one pliable cultist while the rest get slaughtered by his fellows. I think the 1/round as normal situation makes sense, with Hendrick able to pile on bonus stuff on his own so the skill challenge can be completed in a reasonable timeframe relative to the combat at large. This way if he has an excellent card for another part of the combat you could do this amusing thing where he passes the pliable cultist off to his friend Ineas, who talks to him about the wonders of community service while Hendrick throws a powder bomb to blind the demon.

That interaction isn’t exactly realistic, but honestly it feels good so I’m going to go that way for now. So enemies have skill challenges, theoretically anyone could do them but Hendrick’s actually good at doing them (for instance the Scared status is something he can inflict easily, making it so they don’t have to deal half the target’s hp before they can convince him to stop). These statuses have regular combat application, if minor, and Hendrick is the only one who inflicts them in the first 40% of the game (characters have a chance to start dipping into each other’s territory starting in Act 3 of this five-Act game).

This combines with the second point to give an answer to that second question: Most enemies’ skill challenges are pretty similar. Several are near-identical. Because you can only throw on one card a turn plus the stuff you get from Hendrick’s action cards, you don’t need a ton of diversity in the challenges they’re asking of you to get reasonable diversity in how each plays out in combat.

Fourth: What does he get from allies? I’ve determined that roughly all allies are non-combat in nature. There are summons, that’s a separate thing, but there are story, logistical, and mechanical reasons not to have allies join in fights. You’d have to explain why they’re willing to fight for you after you scared them out of fighting, you’d have to deal with how their stats work as a unit on your side (would I have to make an entire combat deck for each possible ally?), and fundamentally you’d be adding another unit to combat which would slow down the action. That’s a minor issue with Summons but at least is easy to adjudicate since the summoner is assumed to have direct control. My sense is that he’s got Favor points and can spend them for...favors. Each of these allies probably has a region, so he can only get help from someone if they’re around, and the ally card just has a short menu - one or two items - of favor costs and effects. A barkeep who gives +2 successes on an Information challenge. A robot who gives Mobility successes because he can turn into a horseless carriage. Whatever.

Fifth: So how does Hendrick get Favor? My first impression is that he gets 2/day, they accumulate to some maximum - ten, say - and he gains +1 Favor each time he befriends a new person. So he’s got an incentive to spend them almost any time they’re applicable, but is capable of running out.

Sixth: Can Hendrick spend Favor to win new people over? The more I mull it over, the less I like the idea. First of all there’d be a strong urge to spend at least 1 point on everyone, since you’d feel like it “refunds” when you win them over. Second, they just seem like different resources. Favor represents the bonds existing between you and people you’ve befriended. Whatever you use to win someone new over would be more like raw charisma. It was easier to conflate the two when the resource was called Leadership. There’s a kind of leadership that wins people over and another kind that gets favors from those you’ve won over - They’re not really the same thing, even when they do use the same word. So let’s not treat them the same. Instead he should just have cards that let him throw extra cards onto targets as a bonus, allowing him to more quickly complete the skill challenge.

The “as a bonus” thing is a term used by two other characters for their combos and counters, so it should be easy for players to grok as part of the terminology of the game. Need to make sure it’s handled in a way that feels similar, though.

0 notes

Text

How Brands Compete And Win

Competitive brand battles can be drawn out affairs, outlasting the tenures of several management teams. They can also be very expensive, often requiring outlays in the hundreds of millions of dollars. In some cases, billions of dollars are involved. It’s not just Coke versus Pepsi. These battles occur in every industry and practically every product category. Visa versus Mastercard. Nike versus Adidas. Colgate versus Crest. Airbus versus Boeing. Caterpillar versus Komatsu. Dell versus Lenovo versus Acer versus HP. Viagra versus Levitra versus Cialis. The list goes on and on.

Brand battles consist of far more than just marketing tactics and consume significant managerial attention. They can define the dynamics of their respective industries for years (or even decades), pushing market segmentation and technological boundaries, driving product innovation, catalyzing mergers and instigating corporate growth and rationalization. Combatants need to arm themselves with a clear understanding of the battlefield and their own competitive objectives and strategy, as well as a thorough grasp of the most important competitive levers, and, for good measure, a gauge of the yardsticks by which success will be defined. But that’s not enough to win.

The spoils in these wars are customer attention, consideration and choice. In other words, the competition for real-world resources (whether it is media, shelf space, raw materials, or talent) is merely a proxy for the real battle for the customers’ cognitive resources. Victory requires an understanding of the rules by which the mind stores and processes information about brands. This article describes the topography of the competitive playing field and looks at how the finite nature of the customer’s cognitive capacity defines the outer boundary of the playing field on which brands compete.

As a platform for transactions between buyers and sellers, brands represent a classic downstream, market-based competitive advantage. They are ubiquitous because they help companies attract customers and make it easier for them to find the products they want and need. Simply put, brands make markets more efficient in the sense that buyers and sellers are brought together at lower cost to both than would be possible without brands.

FedEx encapsulates its value proposition in taglines such as “The World on Time.” Tide laundry detergent “washes whitest” and promises the “Clean you can Trust.” It is no accident that the positioning of brands typically communicates cost or risk reduction. Successful brands offer clear and appealing value propositions that are distinct from the value propositions of competitors.

Brands, of course, also offer an implicit guarantee that the customer’s experience with the product or service will be similar for present and future purchases as it was for past purchases. And in a world of practically infinite choice, consumers gravitate toward brands they trust to deliver on promises. So in order to serve as a platform for customers and sellers to come together, your brand has to demonstrate consistent quality and consistent positioning, over time and over purchase occasions.

Sometimes customers are willing to pay a premium for what-you-see-is-what-you-get clarity. Sometimes they return to their preferred brand simply because of brand loyalty. In either case, a return on investment is gained on efforts to ensure brand quality and consistency, and these returns act as an incentive to the seller to maintain those investments.

Defining Brand Value

A classic thought experiment in the world of branding is to ask what would happen to Coca-Cola’s ability to raise financing and restart operations if all of its physical assets around the world were to mysteriously go up in flames. The answer, most reasonable business people conclude, is that Coca-Cola would have little difficulty finding the funds to get back on its feet. The company would survive such a crisis because the value of its brand would attract investors looking for future returns.

A related thought experiment involves asking what would happen if instead of the loss of the physical assets, seven billion consumers around the world were to wake up one morning with partial amnesia and could not remember the brand name Coca-Cola or any of its associations. In this latter scenario, despite Coca-Cola’s physical assets remaining intact, most reasonable business people agree that the company would find it difficult to attract significant further investment. The loss of the downstream asset, the brand, it turns out, is a more severe blow to the company’s ability to continue business than the loss of upstream assets.

What about Coca-Cola’s secret formula? Without this proprietary upstream asset, the company would not be as successful as it is today. And yet, the so-called “sacred formula” has not been a secret for years. It was made public in Mark Pendergrast’s biography of the Coca-Cola Company entitled For God, Country, and Coca-Cola. As the secret behind Coca-Cola’s success, the publication of this product formula might have been reasonably expected to send Coca-Cola’s share price plunging. It didn’t. But partial amnesia among the world’s consumers about the brand undoubtedly would.

Maintaining Competitive Advantage

What is maintaining this all-important downstream source of competitive advantage all about? In their efforts to build brands and compete for customers, businesses routinely vie for web clicks, page ranks, media visibility, celebrity and influencer endorsements, distribution contracts, shelf space, and paid advertising space. They engage in belabored “conversations” with customers on social media sites. Customer behavior is tracked using loyalty programs and clickstreams. Annual global spending on paid advertising exceeds $550 billion, and is growing at about 10% per year. Retailers, meanwhile, play with store layout, shelf placement, planograms and shelf-talkers to provide higher-margin and faster moving brands with greater in-store visibility. They monetize their shop floors by charging manufacturers for placing their products at eye-level and in end-of-aisle displays.

As seen by the people who manage brands (the network of marketing professionals, brand managers, market research experts, advertising types, packaging designers and salespeople), the job is to get more and better resources for their brands at a cheaper price and to put them to more efficient use than competitors. But that is akin to saying Michelangelo’s job was to “use a chisel.” While accurate, the job description omits a description of the battlefield and the end game, to say nothing of the art. Stepping back from the immediate tactical concerns of efficiency (a cheaper media buy, the development of an effective ad execution, better shelf placement, or search engine optimization), it is worth asking what exactly is it that brand managers fight over. The answer is: a piece of the customer’s mind.

Corporate marketers often point to their brands as being among their companies’ most important assets. They forward Interbrand rankings that show the 100 most valuable brands are worth a cumulative $2.15 trillion to skeptical finance colleagues, hoping that impressive independently adjudicated dollar values will make it easier to maintain or boost their own marketing budgets, or at the very least, help convince the hard-nosed CFO that marketing expenditures are not wasted. In this line of reasoning, the brand is construed as the end of marketing efforts. But while it is useful to keep the financial value of brand investments and returns in mind, managerial focus on the financial end goal can detract from effective brand building. The process, strategy and tactics are obscured. And the customer’s mind, where the brand resides, and where the game is played, remains an enigma.

All Is Won Or Lost In The Mind

The time and cognitive effort that customers spend processing information about your brand deserves close management scrutiny. That’s the playing field on which your brand competes. In a nutshell, it determines how much attention and memory capacity is devoted by consumers to your brand, as well as what the brand means to them. This playing field, like any other, has boundaries and rules. A good understanding of how the game is played allows you to build competitive advantage on this mental playing field.

The marketplace offers almost infinite information, but a consumer’s mind is a finite resource, so the outside boundary of the playing field is of particular relevance to brand competition. No consumer can absorb, interpret, store, recall and use all of the information available, not even all the relevant bits. This imbalance between available information and available mental processing and storage capacity gives rise to a necessary principle of scarcity. Without it, there would be no need for firms to compete for awareness and privileged positions in the consumer’s mind.

A direct corollary of limited capacity is the principle of cognitive economy. Cognitive economy states that because their information processing capacity is finite, customers will often trade off accuracy of results and optimal outcomes for efficiency of information storage and processing. In other words, customers may end up choosing products that are easier to purchase rather than ones that are the best for their purposes, simply because they can’t remember everything about products, or so that they don’t have to think too much about them (because they have other things they’d rather be thinking about). This basic principle has many implications, including the mental shortcuts and mental organizing frameworks that consumers use to make sense of the marketplace.

It is useful to note that the principle of cognitive economy underscores the importance of how consumers buy and consume relative to what they buy and consume. It emphasizes the importance of downstream activities. For example, consider how customers respond to radical innovation. Novel products have very high failure rates. Most of them, whether launched in the grocery store, the technology domain, or business to business arena, end up in the discard pile within a year of launch. Companies persist in developing and launching radical innovations despite their high failure rates because novel products that do succeed tend to be much more profitable. Still, novel products often fail simply because customers don’t know what to make of them. Consumers see too much risk in adopting them or they can’t see where these new products would fit in their lives.

When customers do come across a new product, their cognitively economical approach is to try to classify it, to sort it into a familiar bin or category, so they can make sense of it in familiar terms. If they can do this, they can efficiently apply existing knowledge. For example, coming across a bean bag for the first time, a customer might be confused. But classifying it as a chair clarifies its purpose and usage. This classification is an example of a process called categorization. Categorization is one type of mental organizing framework that consumers use to make sense of the world around them, including the marketplaces in which they work, live and play.

Categorization, like many other cognitive processes, determines the effectiveness of marketing. Early in the life cycle of digital photography, when film-based photography still dominated, Lexar introduced memory cards for digital cameras in gold packaging, similar to Kodak film, with a speed rating similar to traditional film’s ISO rating. Labeled “digital film,” the memory cards were placed alongside photographic film in stores. As a result, Lexar bridged the distance between the new product and what film photographers were accustomed to buying. How the innovation was presented to consumers made it easier for them to understand, compare and contrast the product during the transition from traditional film.

Competitive battles between brands are played on playing fields inside the customers’ minds. It pays to know the layout of the playing field and the rules of the game.

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider by: Niraj Dawar, Author of TILT: Shifting Your Strategy From Products To Customers

The Blake Project Can Help: Disruptive Brand Strategy Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education

FREE Publications And Resources For Marketers

This piece originally appeared on Ivy Business Journal

from WordPress https://glenmenlow.wordpress.com/2018/12/12/how-brands-compete-and-win/ via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

How Brands Compete And Win

Competitive brand battles can be drawn out affairs, outlasting the tenures of several management teams. They can also be very expensive, often requiring outlays in the hundreds of millions of dollars. In some cases, billions of dollars are involved. It’s not just Coke versus Pepsi. These battles occur in every industry and practically every product category. Visa versus Mastercard. Nike versus Adidas. Colgate versus Crest. Airbus versus Boeing. Caterpillar versus Komatsu. Dell versus Lenovo versus Acer versus HP. Viagra versus Levitra versus Cialis. The list goes on and on.

Brand battles consist of far more than just marketing tactics and consume significant managerial attention. They can define the dynamics of their respective industries for years (or even decades), pushing market segmentation and technological boundaries, driving product innovation, catalyzing mergers and instigating corporate growth and rationalization. Combatants need to arm themselves with a clear understanding of the battlefield and their own competitive objectives and strategy, as well as a thorough grasp of the most important competitive levers, and, for good measure, a gauge of the yardsticks by which success will be defined. But that’s not enough to win.

The spoils in these wars are customer attention, consideration and choice. In other words, the competition for real-world resources (whether it is media, shelf space, raw materials, or talent) is merely a proxy for the real battle for the customers’ cognitive resources. Victory requires an understanding of the rules by which the mind stores and processes information about brands. This article describes the topography of the competitive playing field and looks at how the finite nature of the customer’s cognitive capacity defines the outer boundary of the playing field on which brands compete.

As a platform for transactions between buyers and sellers, brands represent a classic downstream, market-based competitive advantage. They are ubiquitous because they help companies attract customers and make it easier for them to find the products they want and need. Simply put, brands make markets more efficient in the sense that buyers and sellers are brought together at lower cost to both than would be possible without brands.

FedEx encapsulates its value proposition in taglines such as “The World on Time.” Tide laundry detergent “washes whitest” and promises the “Clean you can Trust.” It is no accident that the positioning of brands typically communicates cost or risk reduction. Successful brands offer clear and appealing value propositions that are distinct from the value propositions of competitors.

Brands, of course, also offer an implicit guarantee that the customer’s experience with the product or service will be similar for present and future purchases as it was for past purchases. And in a world of practically infinite choice, consumers gravitate toward brands they trust to deliver on promises. So in order to serve as a platform for customers and sellers to come together, your brand has to demonstrate consistent quality and consistent positioning, over time and over purchase occasions.

Sometimes customers are willing to pay a premium for what-you-see-is-what-you-get clarity. Sometimes they return to their preferred brand simply because of brand loyalty. In either case, a return on investment is gained on efforts to ensure brand quality and consistency, and these returns act as an incentive to the seller to maintain those investments.

Defining Brand Value

A classic thought experiment in the world of branding is to ask what would happen to Coca-Cola’s ability to raise financing and restart operations if all of its physical assets around the world were to mysteriously go up in flames. The answer, most reasonable business people conclude, is that Coca-Cola would have little difficulty finding the funds to get back on its feet. The company would survive such a crisis because the value of its brand would attract investors looking for future returns.

A related thought experiment involves asking what would happen if instead of the loss of the physical assets, seven billion consumers around the world were to wake up one morning with partial amnesia and could not remember the brand name Coca-Cola or any of its associations. In this latter scenario, despite Coca-Cola’s physical assets remaining intact, most reasonable business people agree that the company would find it difficult to attract significant further investment. The loss of the downstream asset, the brand, it turns out, is a more severe blow to the company’s ability to continue business than the loss of upstream assets.

What about Coca-Cola’s secret formula? Without this proprietary upstream asset, the company would not be as successful as it is today. And yet, the so-called “sacred formula” has not been a secret for years. It was made public in Mark Pendergrast’s biography of the Coca-Cola Company entitled For God, Country, and Coca-Cola. As the secret behind Coca-Cola’s success, the publication of this product formula might have been reasonably expected to send Coca-Cola’s share price plunging. It didn’t. But partial amnesia among the world’s consumers about the brand undoubtedly would.

Maintaining Competitive Advantage

What is maintaining this all-important downstream source of competitive advantage all about? In their efforts to build brands and compete for customers, businesses routinely vie for web clicks, page ranks, media visibility, celebrity and influencer endorsements, distribution contracts, shelf space, and paid advertising space. They engage in belabored “conversations” with customers on social media sites. Customer behavior is tracked using loyalty programs and clickstreams. Annual global spending on paid advertising exceeds $550 billion, and is growing at about 10% per year. Retailers, meanwhile, play with store layout, shelf placement, planograms and shelf-talkers to provide higher-margin and faster moving brands with greater in-store visibility. They monetize their shop floors by charging manufacturers for placing their products at eye-level and in end-of-aisle displays.

As seen by the people who manage brands (the network of marketing professionals, brand managers, market research experts, advertising types, packaging designers and salespeople), the job is to get more and better resources for their brands at a cheaper price and to put them to more efficient use than competitors. But that is akin to saying Michelangelo’s job was to “use a chisel.” While accurate, the job description omits a description of the battlefield and the end game, to say nothing of the art. Stepping back from the immediate tactical concerns of efficiency (a cheaper media buy, the development of an effective ad execution, better shelf placement, or search engine optimization), it is worth asking what exactly is it that brand managers fight over. The answer is: a piece of the customer’s mind.

Corporate marketers often point to their brands as being among their companies’ most important assets. They forward Interbrand rankings that show the 100 most valuable brands are worth a cumulative $2.15 trillion to skeptical finance colleagues, hoping that impressive independently adjudicated dollar values will make it easier to maintain or boost their own marketing budgets, or at the very least, help convince the hard-nosed CFO that marketing expenditures are not wasted. In this line of reasoning, the brand is construed as the end of marketing efforts. But while it is useful to keep the financial value of brand investments and returns in mind, managerial focus on the financial end goal can detract from effective brand building. The process, strategy and tactics are obscured. And the customer’s mind, where the brand resides, and where the game is played, remains an enigma.

All Is Won Or Lost In The Mind

The time and cognitive effort that customers spend processing information about your brand deserves close management scrutiny. That’s the playing field on which your brand competes. In a nutshell, it determines how much attention and memory capacity is devoted by consumers to your brand, as well as what the brand means to them. This playing field, like any other, has boundaries and rules. A good understanding of how the game is played allows you to build competitive advantage on this mental playing field.

The marketplace offers almost infinite information, but a consumer’s mind is a finite resource, so the outside boundary of the playing field is of particular relevance to brand competition. No consumer can absorb, interpret, store, recall and use all of the information available, not even all the relevant bits. This imbalance between available information and available mental processing and storage capacity gives rise to a necessary principle of scarcity. Without it, there would be no need for firms to compete for awareness and privileged positions in the consumer’s mind.

A direct corollary of limited capacity is the principle of cognitive economy. Cognitive economy states that because their information processing capacity is finite, customers will often trade off accuracy of results and optimal outcomes for efficiency of information storage and processing. In other words, customers may end up choosing products that are easier to purchase rather than ones that are the best for their purposes, simply because they can’t remember everything about products, or so that they don’t have to think too much about them (because they have other things they’d rather be thinking about). This basic principle has many implications, including the mental shortcuts and mental organizing frameworks that consumers use to make sense of the marketplace.

It is useful to note that the principle of cognitive economy underscores the importance of how consumers buy and consume relative to what they buy and consume. It emphasizes the importance of downstream activities. For example, consider how customers respond to radical innovation. Novel products have very high failure rates. Most of them, whether launched in the grocery store, the technology domain, or business to business arena, end up in the discard pile within a year of launch. Companies persist in developing and launching radical innovations despite their high failure rates because novel products that do succeed tend to be much more profitable. Still, novel products often fail simply because customers don’t know what to make of them. Consumers see too much risk in adopting them or they can’t see where these new products would fit in their lives.

When customers do come across a new product, their cognitively economical approach is to try to classify it, to sort it into a familiar bin or category, so they can make sense of it in familiar terms. If they can do this, they can efficiently apply existing knowledge. For example, coming across a bean bag for the first time, a customer might be confused. But classifying it as a chair clarifies its purpose and usage. This classification is an example of a process called categorization. Categorization is one type of mental organizing framework that consumers use to make sense of the world around them, including the marketplaces in which they work, live and play.

Categorization, like many other cognitive processes, determines the effectiveness of marketing. Early in the life cycle of digital photography, when film-based photography still dominated, Lexar introduced memory cards for digital cameras in gold packaging, similar to Kodak film, with a speed rating similar to traditional film’s ISO rating. Labeled “digital film,” the memory cards were placed alongside photographic film in stores. As a result, Lexar bridged the distance between the new product and what film photographers were accustomed to buying. How the innovation was presented to consumers made it easier for them to understand, compare and contrast the product during the transition from traditional film.

Competitive battles between brands are played on playing fields inside the customers’ minds. It pays to know the layout of the playing field and the rules of the game.

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider by: Niraj Dawar, Author of TILT: Shifting Your Strategy From Products To Customers

The Blake Project Can Help: Disruptive Brand Strategy Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education

FREE Publications And Resources For Marketers

This piece originally appeared on Ivy Business Journal

0 notes