#how do you like those long walls now PIRAEUS

Text

"if you could travel to any point in time what would you do-" I would give Ancient Sparta one (1) tactical bazooka. why? two words. Long Walls

#alternatively put them in a jar and shake them up and down really hard#how do you like those long walls now PIRAEUS#not looking so solid are they hmm?#tagamemnon#classics#peloponnesian war#history#ancient history#my boss said I could shitpost

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kryptic ↟ Deimos

twenty-four - a song of the fates

masterlist

But the great leveler, Death: not even the gods can defend a man, not even one they love, that day when fate takes hold and lays him out at last.

Death submits to no one, not even Dread and Destruction.

They are both weapons of flesh and bone, of warm blood and beating hearts, and they cannot be controlled.

“DON’T STARE TOO closely into the mist,” Tryphena chides from the helm, watching as Tundareos and his sister peer into the heavy fog, “last time you almost drove us into the rocks chasing sirens.” Lesya smiles, looking over her shoulder at the dark-skinned lieutenant as she helps man the rudder. For a brief moment, the lingering grey parts, allowing a glimpse of the Attikan countryside —patches of ash and toppled stone, yet the crimson banners of Sparta are nowhere to be seen.

A short while later, Tryphena calls to the crew, and the trireme jolts before falling still. The cool fog parts again, revealing the stone towers and wharf of Piraeus —the Ippalkimon docks near the Adrestia, tying off the mooring lines. The port is deserted in comparison to what it had been before. There are no bustling traders or hurrying slaves, nor sound —bar the sad tolling of a distant bell.

Lesya and Tundareos pace down the gangplank, joining Kassandra and Herodotus in surveying the desolation. Wagons sit parked as though abandoned in haste. Some on their sides with the contents spilled and pillaged. It takes a moment for the smell to sink it, an insidious and potent stench of decay. The gods have forsaken Athens, Lesya thinks as she looks up at the Temple of Asklepius.

The few sentries posted around the harbor wear rags over their mouths and noses. “Move along!” One of them shouts, gesturing toward the promenade running inside the enclosing sleeve of the walls protecting the road connecting Piraeus and Athens.

“We speak to Aspasia and Perikles and then we leave,” Kassandra announces looking between the historian and Lesya —her brother standing at her side— before they set off on the promenade and through the grey mist. The path is different from the one they had taken nigh a year ago. The drone of flies, weeping, and plaintive chants fill the air.

Bulky shapes line the roadsides, Lesya guesses they are shanty huts of refugees, but ahead the fog breaks, and bile rises in her throat. The ramshackle shelters are long gone, in their place are serried piles of dead as far as any of them could see —thousands of corpses.

Some are soldiers, most are not. She stops, staring into the heap of cadavers —eyes shriveled or pecked out by crows, jaws lolling; skin broken and partly rotted or riddled with angry sores. Lesya has dealt out her fair share of death, leaving mangled corpses across Hellas, but nothing can compare to this —a dangling limbs, clumps of hair, dripping pus, blood, and seeping excrement. No wonder the Spartans abandoned the siege. Too many people cramped within the walls had cleared the way for the pestilence to rise and ravish the denizens and those fleeing to safety from the countryside.

The path of death does not diminish as they near the agora —the stench of burning flesh and hair is heavy in the air, as is dark smoke. Lesya watches as men and women shuffle past with cloths on their faces, bringing fresh dead to add to the piles —one of them drops the body of a young girl and staggers away, sobbing.

A troop of hoplites march by, pushing the sick aside. “Kleon,” a woman starts, straightening after kneeling next to a heaping pile of dead. “He seeks to use this plague like a lever, to make the acropolis hill his own. He’s bought the loyalty of citizen soldiers and has a demigod on his side.” She coughs, the rattling sound muffled by a cloth, and stumbles away. Lesya’s stomach drops, Deimos is still here.

“I’m going to find mater,” Tundareos announces, doing well to hide his fear, though Lesya can still see it —one in three Athenians rest among the dead. Kassandra and Herodotus move along toward Perikles’ villa. After a moment’s pause, Lesya turns to follow her brother. She trails a step behind him, eyes downcast as she remembers what happened the last time she was here. More bodies line the streets. Some finely clothed and others stripped of their silk robes and jewels. Lesya's hands clench into fists. One in three, her mind echoes —she will not give herself false hope.

Tundareos stops before the mosaic path and looks up at the pale stone —he was still a boy when he ran away in search of his sister. Now, though, he clasps onto her shoulder, smiling. It may have taken half his life, but he is returning home having found her. Mater will be proud, he thinks, anticipation and hope swelling within him. Lesya cannot return his smile in good faith.

“Mater!” He calls, passing through the andron. Silence answers. Gathered in the courtyard are hushed voices, surrounding a corpse swaddled in linen. They are too late. Among those gathered is Hippokrates. Tundareos surges forward, pushing through the acolytes, and kneels at Kalanthe’s side, shoulders shaking.

Lesya stops, staring at what she had known in her gut to be true. Hippokrates approaches her, resting his hand upon Lesya’s shoulders. The plague spared neither rich nor poor and Kalanthe had fallen into hard times since the death of her thesmothetai husband. Guilt twists in her stomach. She is not sorry for killing Leandros —would do it again given the chance— though a piece of her wonders, if her mother would have fallen to the sickness, had Leandros lived. “I’m sorry,” the physician confesses —both for the death of their mother and the desecration that must follow in an attempt to spare others. There will be no burial for Kalanthe, only a pyre or a nameless pit.

The acolytes lift Kalanthe’s corpse, carrying her from the villa for a final time. Tundareos moves back to his sister’s side —watching the dark-robed figures disappear into the grey haze. He wipes the tears from his eyes and looks around the empty villa. There are no slaves bustling, no lyres being played, no fire burning in the brazier. “Pater?” Tundareos calls and silence answers him again —he looks up as if pleading with the gods, lost.

Lesya’s blood runs cold, heart dropping to the pits of her stomach. She hadn’t told him Leandros, the man who sheltered them as children, was killed by her hand. There will be no more hiding after today. “Tundareos–” she rakes a hand through her copper hair, pacing around the courtyard “–I killed him,” she tells him, unable to mask the small shred of pride in her tone.

“What?” He asks —the weight of Lesya’s words not sinking in or either he does not wish to believe his sister had murdered their father.

“He was a hateful man who sacrificed me to the Cult, Tundareos!” Lesya shouts, voice trembling and laurel eyes burning with hatred. Everything ill that had befallen her in life was his fault. It was because of Leandros of Athens that her humanity and identity had been stripped away, leaving behind a hollow shell of a once lively girl. “It’s because of him I’m a monster!” It was nigh impossible to sleep with memories haunting her and no matter how much she scrubbed her hands, Lesya could still see the blood of innocent on them. There was no other way to describe what she and Deimos had become at the hands of Chrysis and the Cult of Kosmos.

Tundareos’ face twists in ire and resentment. Leandros had not been a kind man, but he had loved his sons above all else and that love had been reciprocated. His hands turn to fists at his side. Perhaps you truly are the monster they say you are, sister. He swallows the thought, but cannot contain the mix of rage and grief. “He was my father!” He roars —spittle flying in the outburst.

“I cannot change what I have done, brother,” Lesya starts, meeting his cold and clear gaze, “and even if I could, I would not bring him back.” Leandros —son of Kalliades— deserved to rot in the depths Tartarus for the pain he caused her.

Between his mother’s death at the hands of the pestilence and his father’s ruin at the hands of his sister, Tundareos cannot stomach the thought of looking at Lesya again. He turns his cheek to her and draws in a heavy breath. “Sister,” he says, voice suddenly hoarse, “go.” Lesya flees, wiping away tears, and travels down the street leading to Perikles’ home at the base of the Acropolis.

No guards are posted though Aspasia pales, her back going rigid upon seeing Lesya enter the villa. Enyo always brings death and destruction in her wake. The champion has never seen her face without a weeping ivory mask, but her voice is unmistakable —the Ghost of Kosmos. “Leave us,” Aspasia tells Sokrates and the others taking shelter in a calm, commanding voice. They leave in silence, dispersing into several rooms with lowered heads.

“You fucking snake,” she hisses, closing the distance between them in three strides and seizing the hetaera by the neck. Fear flashes in Aspasia’s amber eyes —there is no one here who can save her should the disgraced champion choose to act. Lesya squeezes harder.

“She’s different!” Aspasia gasps, speaking of Kassandra as her hands wrap around Lesya’s wrist. “Not like Deimos,” she pauses, straining for breath, “or you.” Lesya’s face contorts, her grip tightening for a second more before she lets the hetaera go with a shove —sending her to the ground. Her hand goes to her neck, rubbing the tender flesh. Aspasia looks up at the weapon she helped create, a weapon that could still be put to use. “See me safely to the Parthenon,” she requests, but Lesya just laughs.

“You trust me not to hand you over to the mob?” Kleon stirs the mobs to riots —many of them want to see Perikles’ head mounted above the city gates for his inaction against Sparta. Blaming him for the rise of this pestilence that had claimed both young and old alike. It would be easy to give Aspasia to the mob and let them dispose of her. The Ghost of Kosmos dead at the hands of the oppressed, it does not sound like a bad thing to Lesya.

Her amber eyes narrow. “I trust you not to betray Kassandra,” she says, rising to her feet. Lesya swallows, after potentially losing her brother, she is not willing to risk the loss of a friend for vengeance.

THE EAGLE BEARER joins them on the steps of the great temple, tears streaking her face. Phoibe. It is all cut short by a ragged cry from behind the great wooden doors. Kassandra and Leysa push them open just as Deimos sinks to a crouch and wraps a mighty arm around Perikles’ neck.

He looks up, meeting the eyes of his sister, Aspasia, Hippokrates, Sokrates, and Lesya. “I’m going to destroy everything you ever created,” he whispers in Perikles’ ear, placing his blade edge on the Athenian general’s neck. Deimos’ arm jerks. Aspasia cries out and lurches forward, stopped by Sokrates. The Eagle Bearer looks to the side grimacing as blood spouts and soaks Perikles’ robes —his wan body turning grey in a trice. Lesya’s gaze burns into him with all the grief of the day rising in her gut. Deimos releases the corpse and stands, his white-and-gold armor streaked with blood. “Stay out of my way,” he hisses, flicking off the blood dripping from his sword.

The handful of masked men accompanying him advance, but Lesya slips away to pursue Deimos, confident Kassandra would be able to dispatch the remaining guards with ease. He is halfway down the marble steps of the Acropolis Sanctuary —armor glinting in the moonrise. “Deimos!” She shouts and his shoulders tense. “Stop!” Now her voice is baleful.

He turns, unsheathing the Damoklean sword and levels it toward Lesya as she nears him with her own daggers drawn. “You need to stay out of my way, too,” he growls. She ignores him —knocking him back with a powerful kick. He has to be stopped. Lesya spins out of his advance but does not react quickly enough to block his elbow from colliding with her jaw. She spits blood and drags the back of her hand across her busted lip.

“You’ve gotten slow,” he remarks, coming for her again. He swings his sword and the tip streaks down her shoulder and lower back, slashing open her leathers and tearing through her tricep —her side and arm suddenly hot with blood. She cries out and staggers backward, but levels her blades again, knowing she has endured worse pains than this. Deimos clenches his jaw as he eyes the blood sluicing down her leg. “Don’t do this,” he rasps —if they cross blades again, he might not be able to stop.

She steps forward again, jabbing the point of her blade at his thigh and narrowly missing. He lashes his blade in a flurry of quick swipes and it is all she can do to parry them. There’s a moment’s opening and she sees a weak point at his knee and calf. Lesya stabs out, but like a viper’s tongue, he strikes downward, blocking the cut, and flicks his blade up, slicing across her face. Blood and sweat sting her eyes —her strength ebbs away.

The blades in her hands clatter against the stone and then she is falling. The pale stone around them is painted with splotches of bright red. He watches, aghast this has been his own doing. “No,” Deimos utters. Sheathing his sword, he kneels and scoops her into his arms. She whimpers. “Lesya,” he breathes, stroking over the bloody cut at her hairline —he hadn’t meant for it to go so far. Her eyes are wide, staring up at him but unfocused.

He takes her to Hermippos’ residence —the air is thick with burning herbs and sweet incense to mask the scent of death. Deimos threatens to cut out the Cultist’s tongue if he speaks to anyone about this night. Hermippos has always been cowardly and Deimos uses the man’s fear to his advantage. Slaves scuttle in and out of the bedchamber, bringing water, rags, and a fresh poultice.

Deimos tends to her with shaking hands, his heart heavy and guilt-ridden. You kill Perikles or we kill her, Kleon’s words echo in his mind. It is your choice, Deimos. It had not been a hard choice. Sitting back on his haunches, Deimos runs his hands down his face and is startled to feel the dampness on his cheeks. He waits at her side almost until the morning light.

“Enyo.” That is not her name, but Lesya responds out of instinct. A pair of tawny-gold eyes meet her own. Deimos. His face is a mixture of troubled emotions. Pain. Guilt. Anger. Two calloused hands settle on her sides —helping her sit. Fresh tears spring up in her eyes at the burning pain in her back and side. She looks around the dimly lit bedchamber, finding her bloody armor and exomis piled in a corner, and stained rags are strewn over the floor near a washbasin with red-tinged water. It is a familiar situation. One she and Deimos have been in too often.

Deimos pulls his hands back, taking in her scars and injuries as though he has just remembered it is his hand that harmed her. “Where am I?” Lesya asks, raising her hand, fingertips ghosting over the scab cutting through across her brow up into her hairline.

“Athens still,” he answers. An ember catches flame and burns in his dark eyes. “I told you to stay out of my way.” If she would have just listened to him, all of this could have been avoided. He looks down at his hands, numb. He had hurt her.

“You know I can’t,” she mutters, reaching for the small tie holding stained white pteruges to his gold-and-white cuirass. Deimos does not object. Instead, he pulls free the knots, ripping the breastplate from his chest and the belt from his waist. Lesya takes his face in her hands, pulling him toward her until his rough lips find hers —hands slipping down his sides. He eases her back down on the feather-stuffed mattress, never breaking the kiss.

Warmth blossoms in Lesya’s chest, sparks igniting when he parts her lips with his tongue. She finds an uneven brand at the base of his ribcage and sighs into his mouth —it had not been there that night in Korinth. “Deimos,” Lesya breathes, her heart aching to know they will have to part ways again. He braces his weight on his forearms, cupping her cheek as he meets her laurel gaze —something about how she looks at him now, after everything, makes his heart ache too. They were each half of the other’s soul as the poets would say.

No one could escape their fate and Lesya and Deimos’ were always meant to be entwined.

@wallsarecrumbling @novastale @fjor-ok-skadi @fucking-dip-shit

#Alexios#Deimos#Alexios x OC#Deimos x OC#Alexios Imagine#Deimos Imagine#Alexios Fanfiction#Deimos Fanfiction#Assassin's Creed Imagine#Assassin's Creed Fanfiction#Assassin's Creed Odyssey#story: Kryptic#my writing

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

the marble king, part 4 [read on ao3]

Athens, 1453

Catching a current to Thera had been a simple task. Well, there had been parts to the journey somewhat more complex than he had let on to his traveling companion, but the steps taken had, all told, been rather simple for a son of the sea god. Following the currents was a matter of instinct, and in the water, he could forget mortal afflictions such as hunger or exhaustion.

Annabeth did not have the same freedoms, of course, and while Percy could extend his gifts to her for some time, he simply was not strong enough to sustain it for the entirety of the journey to Athens. Travelling by boat was somewhat riskier, as there were the Ottomans and the Venetians to avoid, not to mention all the other Latins and Franks and gods-only-knew-who-else who sought to steal some of Hellas ’ glory for themselves, but Percy was confident that he could steer a ship out of danger with far less effort than he could carry Annabeth under the sea.

“It will draw less attention to ourselves,” he had reminded her, “if we are merely one of a thousand mortals making pilgrimage to Athens.” Convinced, unhappily, she agreed.

It had been a long, quiet, terse five days, and not only because she would often refuse to speak to him.

The two of them had traveled these waters together once before, searching for a certain magical sheepskin, but Percy could never recall them being so empty. In his memory, sea monsters lurked beneath every wave, while other horrors plucked straight from the mouths of the poets and muses made their homes on every spit of land, no matter how small. But the monsters and the madness that had haunted heroes such as Jason, Odysseus, Aeneas, and all the others, appeared to have simply vanished into the mist. Even the waves themselves were unusually pacified, allowing them to pass without too much trouble.

It all made for quite the unsettling picture. It was, at once, both empty and not empty; he felt as though they were standing upon the shore as the water was pulled out to the sea, in preparation for the monstrous tsunami which would follow. If a man were able to live in that moment, the calm before the storm, the precipice before the cliff, the sharply receding tide before the flood, then he would know how the sea felt to Percy in this moment.

“Look, Annabeth,” he said, in an attempt to cajole her into conversation. “There, to the West--we are coming up on Delos.”

She did not respond.

“Do you not remember? Apollo’s lions burst forth from the stone and nearly ate us for trespassing.”

All quiet. When he looked to her, she had her head tipped back against the wood of the ship, eyes closed, hands fiddling with the frayed edge of her shawl, a thin, faded grey strip of fabric. She must have woven it herself; he thought he recognized her patterns as they shifted in the bright sunlight, but they had grown distorted by time, the threads stained with brown, dry blood.

With a sigh, he turned back to the sail, adjusting it, the scrape of rope soothing to his ears. The sea was never meant to be so silent, yet as the presence of the gods had fled the last standing city of their once great empire, as his father’s palace now sat cold and empty at the bottom of the sea, so too had the sea seemed to have lost all its magic.

No, not all of it, he thought. Was he himself not living proof that magic still lived in this land? He could yet still breathe underwater, could still command his boat and navigate the seas with more skill than the most experienced captain. There had been the terrible moment, a painful and fleeting thing, in the heartbeats between leaping into the sea with his arms around Annabeth and hitting the water, where he wondered if, rather than securing their escape, he had led them to their deaths instead, that he had lost the powers Annabeth had accused him of relying on too strongly.

But of course, they had not. Percy was of the sea, the ancient salt and spray his blood and his breath, and the power of Poseidon would remain within him always, even if the god himself did not.

In silence, they made their way then to Piraeus. As Percy had predicted, they blended in quite well with their fellow pilgrims, and if any person thought it odd that their vessel was only crewed by two, they did not mention it. At the very least, they were spared from walking in the hot sun, as Percy managed to scrounge up a few coins from the meager money Annabeth had found to rent them passage on a horse cart which traveled into the city. Still tired from the long journey, she lay her head on his shoulder, their backs pressed against the wooden cart.

Percy had never seen Athens before. He had seen the painting, which hung in Annabeth’s and her siblings’ villa, and he had heard her speak of it, many many times. Based on how often she spoke of it, he felt as though he had been there a thousand times before, had seen its winding streets and mighty marble monuments. By the gods, they had been tasked with crafting little miniatures of the Parthenon as a way of testing their fine motor movements. The way she talked, the things she built, surely she must have seen it for herself. “Bet you’re glad to be back,” he said, not really expecting an answer. “I’ve never been to Athens before.”

“Neither have I,” she mumbled.

He turned to look at her, shocked. “You haven’t?”

“Never had the chance.”

“But--I thought--the way you speak of it--”

“I’ve always wanted to see it, of course,” she said. Annabeth kept her eyes on her hands, playing with the increasingly fraying ends of her shawl. “All children of Athena do. But I have studied the temple more keenly than anyone I know. I know everything there is to know about the Acropolis. Every temple, every column, every brick was placed with the finest care and the foremost precision.” She smiled then, a small, creeping thing, and it seemed to lighten her whole face. “I cannot wait to see it.”

Like this, so soft in the face, almost dreamy, she was honestly quite pretty, he thought to himself. “Tell me about it,” he asked, as soft as a puff of wind, as though he had never heard her speak of it before.

Her shawl dropped to her lap. “We begin at the propylea,” she said, tracing the outline with her fingers, “the great winding road up the Western side of the mountain. Immediately to your right, there is the temple of Athena Nike, then once you enter beneath the great archway…” She sighed, almost ardent. “There, you would see it: the statue of Athena, and behind her, the Parthenon. The columns are of the Doric order, and thus unadorned at their top by any sort of frivolous curls or curves. Above them sit the metopes, which ring the whole building, and each marble frieze tells of a great epic; the Titanomachy, the Amazonomachy, the Trojan war. And the colors,” her face broke out into a true smile, and her eyes crinkled at the corners, shining and silver. “Such beautiful colors, red and gold and green. Oh, and the pediments! We must not forget the pediments.”

“The pediments?” He frowned. “I do not know that word.”

“It refers to the triangular space between the portico and the roof. Do you not remember the door of the Big House?”

Yes, he recalled now, though he didn’t see what all the fuss was over the empty space was. “Are the pediments truly so important?”

“These ones are,” she said, “for the western pediment depicts the story of our parents.”

“Ah.”

Now this was a story which she loved to hold over him, retelling every chance she could, to make sure that he never forgot which of their divine parents were revered by the city of Athens.

“It is beautiful, Perseus, you shall see,” she said, with a teasing grin. “It is said that the bodies and the horses are rendered so perfectly, I cannot imagine that you will not be able to see the look on your father’s face as he realizes he has lost the contest for Athens.”

“Yes, well,” he harrumphed. “It had better be worth it, then.”

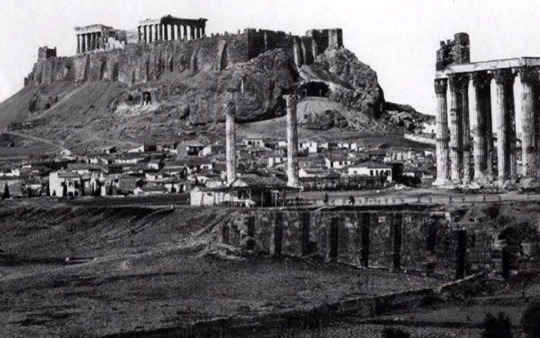

“It will be,” she assured him. “Once we round the Areopagus , you will be able to see the propylea above the mountain, and the perfect point of the Parthenon above that.”

When they approached the Areopagus proper, some hour or so later, she actually leaned forward, going up on her knees to better see the view from their cart.

“Here it is,” she said. Her whole body quivered, as tense as a bow on a string. “Here it is.”

He smiled at her excitement, as though she were a child.

Almost immediately, he noticed something was wrong. Her shoulders were tight, raised up to her ears as she went deathly still. “Annabeth?” She did not answer him. “Annabeth?”

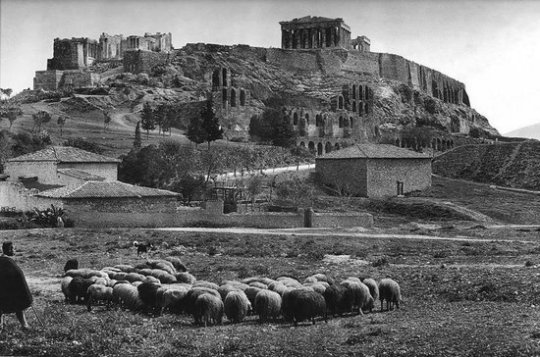

Joining her at the lip of the cart, he looked up at the Acropolis.

He frowned. “What are those walls?”

The many, many times she had described the Acropolis to him, she had never once mentioned the stone walls. Brown and grey, they rose up out of the sheer cliffside, notched indentations in the top like teeth, as though they were devouring the cliff-face whole. On the northern and southern ends, two large towers lorded over the rest.

Too enthralled in the stone walls, he did not notice as their cart traveled onward in the shadow of the cliff. “Where are we going?” he asked, looking towards the horse at the front of the cart. “Was that not the propylea ?”

It was only then that he saw Annabeth. Pale as a ghost, she was, her knuckles white from gripping the edge of the wood, and her face was set in a terrible grimace. Her eyes bulged out as though she saw a monster, her chin trembling as she opened her mouth and gasped out, “Those are not supposed to be there.”

“What isn’t?”

“The walls.” Her voice was barely more than a whisper. He always knew her to be solid, immovable, strong as a statue, but now she looked as though she could be brought low by a mere puff of wind.

“Perhaps they are new,” he offered.

But she fell silent again, glaring at the cliffside as they passed. Her hands, now resting in her lap, clenched and unclenched over and over again, twitching in the manner that suggested she was about to draw her knife, though what target had drawn her ire he could only guess--presumably, she dreamt of stabbing the fool who had chosen to add walls to the Acropolis. Her jaw was hard, set so firmly he thought he could hear her grinding her teeth behind her lips. Antagonistic as they were, he had been on the receiving end of that glare more times than he cared to remember, and he was again glad that they had chosen to set aside their rivalry for now. Eventually, the driver let them off on the eastern side of the mountain. For a moment, he made to help her down from the cart, as he had been taught, but looking at her face, he decided not to risk the insult, allowing her to scramble down to the ground by herself, and side-by-side, they made the long trek to the Acropolis, just another two pilgrims on the final leg of their journey.

Unfortunately, their troubles were merely beginning.

Cresting the hill, the midafternoon sun beating down on them, Annabeth stiffened against him, so severely he thought she might faint. “What,” she hissed, “is that monstrosity ?”

He blinked, squinting through the bright light, though he did not see anything so obviously offensive to the senses--but then, he did not know the field of architecture nearly as well as she did. “What is it?”

“That!”

On top of the building immediately before them rose a bell tower, a cross sitting proudly above it. Surely she could not be referring to that, as the streets of Constantinople had been practically littered with bell towers and crosses. One would be hard pressed to find a corner which did not have a church with its own bell and steeple. “The tower?”

“No, the columns,” she scoffed. “Of course the malakes tower! What is it doing on top of the Parthenon?”

“Annabeth,” he said slowly. “It is a bell tower. Surely, you know what a bell tower is.”

She flushed. “Yes, I know what a bell tower is, phykios , but what I do not know is which imbecile thought to put one up on top of the Parthenon!” She pointed, glaring at it. “It is not even symmetrical!”

He tilted his head, looking. She was right; it did seem oddly placed, given what he had heard of the temple, far back and to the left.

“This is all wrong,” she fretted, worrying her lip between her teeth. “This is--this is wrong. We are supposed to enter through the propylea from the West, into the Precinct of Artemis Brauronia, then pass the Athena Promachos on the northern edge , and--and the pediment--”

Oh dear. She was shaking, now, a leaf on the wind. It was a risky move, to be sure, but he rested a hand on her shoulder, squeezing. She trembled so violently, he thought he could feel it in his bones. “Here,” he said, “let us go inside. We can sit down, catch our breath.”

The fact that she did not refuse him was more concerning than if she had turned around and stabbed him.

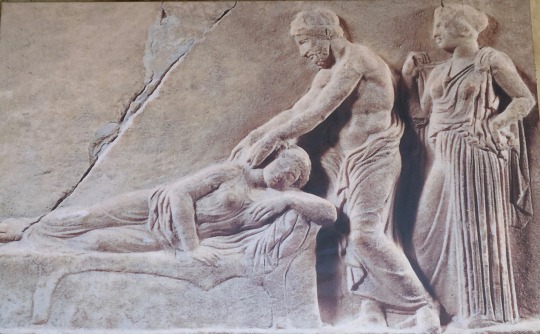

Walking into the--the church, he supposed it was, he too felt a little uneasy. The western pediment, the one she had spoken so highly of, the one which was supposed to portray the origins of their ancient feud, a good third of it was missing, plucked straight from the middle of the frieze, the faded pale statues headless, like corpses in the grip of death.

Percy had seen many churches before. Few could compare to St. Sophia, but in essence, all churches looked somewhat the same. He did not have the fancy words for it, not like Annabeth, but he could recognize their shared features should he see them. This was…

He did not know what to think of it, truly.

He supposed that St. Sophia had spoiled him, all that light streaming in through the dome of the roof. The churches of Constantinople were not places which he frequented, but he found himself in St. Sophia for pagan-related duties more frequently than he cared to be, and had become used to that kind of space, so open and airy. By contrast, here the ceiling was flat, dark, nearly oppressive. Rich frescoes and golden mosaics surrounded them, their strange, frightening faces staring down at them, in cold, apathetic judgement. Pilgrims streamed in through the narrow entrance, pressed so close together that Annabeth was forced to grab onto his arm for fear of being separated. Still she shook, shivering as though she were feverish, and before he could think better of it, he placed an arm around her shoulder, drawing her off to the side, away from the large crush of people. Gently steering her, he brought them to the back left corner of the main gallery, and dropped to his knees in order to better blend in with the crowds, pleased when she took his lead without any further prompting.

“This is all wrong,” she whispered. “This is so wrong.”

He squeezed her shoulder, placing his head against hers. “I’m so sorry.”

“Those walls,” her breath hitched, “those hideous, ugly walls--”

“I know,” he said, “I know.”

“I--I didn’t think that--I never thought that, that it might have changed. That it might be different.” She turned to him, eyes wild. “I never--the Parthenon, it’s… you do not understand, the Parthenon is perfect. It is the most perfect piece of architecture ever conceived, ever planned, ever built. The architects, their understanding of mathematics is unparalleled, even to this day. It is perfect .”

He did understand, but now was not the time to point that out. Now was simply the time to listen.

“All children of Athena, we can only dream of creating something even half as beautiful. The Parthenon isn’t supposed to change, it is supposed to endure. Survive.” She swallowed, eyes blinking back furious tears. “Look at what they have done to her altar. Her temple.” Turning from him, her hand swiped at her face, and he looked away. “And these horrible, horrible bodies,” she hissed, after a moment. “The statues of the Parthenon are meant to embody the perfection of the human form. What man do you know looks like that?”

Towards the end of the room was the greatest offence yet. As with all churches, this one too had a portrait of the moment of death of their trinity god, his arms fastened to a wooden cross, his head hung in shame and despair. At his feet, a woman wrapped in blue looked on him in painful grief, her hands outstretched as though she could catch the frozen stream of glittering red which poured from a black mark in his side, their features flattened and reconstituted with different colored stones, thick lines criss crossing their bodies.

She shook her head, disbelieving. “My mother would never have let this insult go unpunished. She must still be here. She has to be.”

Now her tears had dried, and her mouth was set in a thin, grim line, stubborn and serious. No longer did she shake apart on the cold, stone floor, but was still, poised, gathering energy about her as she waited for the proper moment to strike. Oh, he did not have the heart to attempt to convince her out of her plan.

“Stay here. I will see if I can find a way to speak to her.” And so she left him there in the gallery of the church, off to seek some quiet corner.

Unfortunately, she had not specified for how long she would be gone. And truthfully, she should have known better--they were all saddled with the half-blood’s curse, the plight of wandering attention and nervous energy. To order Percy to stay put was simply a folly. He vowed that he would not leave the Acropolis, for it simply was not that big, and they were sure to find each other easily, but he could not be blamed for indulging this small bout of an itinerant spirit.

Walking out of the church, before he could exit entirely, something gold caught his eye, and he looked up. Almost directly above the entrance was a raised part of the roof, reminiscent of the dome with which he was most familiar, but instead of sunlight, the dome was lined with gold and pearl and lapis lazuli in what even he had to admit was a stunning mosaic. The same woman was depicted here, in the same stunning blue robe, though she looked down on them not in grief, but in deep, pensive thought. No, not pensive, he amended--calculating. With her straight nose and keen eyes, she seemed to stare deep into his very heart and soul, considering all the contents she found there, and he was unsure whether or not she found him wanting.

Perhaps it was merely because he had been thinking of her so often these last few days, but for some strange reason, the woman in the mosaic reminded him of Annabeth. He had seen that piercing gaze on her face many times, one that she shared with all of her siblings. It was a trait inherited directly from their shared mother, the one they wore when they were crafting the very finest of their battle strategies.

Unnerved, he continued on, stepping out of the church into its looming shadow.

In front of him rose another one of Annabeth’s hated towers, round in the way he had come to expect from fortified walls, with soldiers eyeing the pilgrims warily from their positions at the top, though he doubted these men had seen much in the way of fighting. Although, who was he to tell. He had thought, once upon a time, that churches were meant to be sacred spaces to men of god, places where no blood could be shed, nor hateful action be taken. Of course, he knew better now.

Wandering round the Acropolis did little to ease his strange mood. It could not have been a more different experience than exploring his father’s palace beneath the sea; rising high above the city, rather than submerged beneath the depths, where one was empty, ruined and rotting, the other was full, crowded with masses of travelers and worshippers, its fortifications kept seemingly well. And yet, as he walked, still he sensed that strange emptiness that he had felt down below. The people who surrounded him may as well have been ghosts for all that he could know them.

Unbidden, his footsteps brought him past a collection of red roofed houses, squat and low, then round to a strangely shaped building on the northern side of the Acropolis. He frowned, walking down the slim stone steps, taking in the columns whose spaces had been filled with grey stone.

He had not lied to Annabeth when he said he had never been to Athens before, and he surely did not have her thorough knowledge of the ancient buildings which decorated it, but he knew, deep in his bones, that what he was looking at here was wrong. Beyond the ugly stone, it came too far forward, as though it were a living, breathing creature, swallowing the ancient marble over the course of a thousand years. Tilting his head, he tried to put it from his mind as he considered the four pillars which stood before him.

There was something behind those walls, he knew, though he did not know how, something which called to him, deep in his soul. If he closed his eyes, he thought that he could smell seawater, imagined that he could hear the gurgling of a spring, deep beneath the foundations of the earth, pouring forth as though it were a beating heart.

“Percy.”

He blinked.

Annabeth stood before him, scowling. “Did I not say to stay where you were?”

The sun laid low on the horizon, casting long shadows over him, though he could not have been standing here for more than a few minutes. “I… I apologize,” he said. His thoughts were fuzzy, as though he were emerging from an unintended nap. “I did not realize how long it had been. Did you find what you were seeking?”

Her scowl deepened further, before dropping, as though it were a mask, leaving nothing but weariness behind. “No,” she said, her gaze dropping to the ground. “My mother would not come.”

“Perhaps we can find a market,” he suggested, though he knew it would be a fruitless gesture, “and procure a sacrifice. Maybe that would entice her to appear.”

But she shook her head, her lips pulled into a frown. “That would not be wise. I fear that if she allowed the desecration of her temple in this way without repercussion, there is very little that would call her down from Olympus.” She turned to join him, then, standing shoulder to shoulder as she, too, beheld the strange facade.

“Tell me about this place,” he requested. Speaking at length on architecture was, after all, one of her favorite pastimes, and he did so hate to see that sorrowful look on her face. “I feel as if I… know it, somehow.”

“I am not surprised,” she said. “This is--was--is the Erechtheion, the temple dedicated to both of our divine parents.”

“I see,” he teased, hoping to make her smile. “And you said that the Athenians did not like my father.”

Gods be praised, it worked. Trembling, as though she were fighting it, a smile did raise the corners of her mouth. “I said nothing of the sort, merely that the early Athenians vastly preferred my mother.”

“And yet, here lies a temple to his glory.”

She lightly smacked him. “There were shrines to the other gods as well, phykios .”

“You cannot take this from me, skjaldmær. I shall go round proclaiming its glory to all who would listen to the tale of Poseidon and his Athenian temple.”

“Oh, hush.” But she was grinning now, and his heart rose at the sight.

They stood there for some time, as the sun continued to set over the complex, the shadows of the towers lengthening with every minute. The longer they stood, the more the question nagged at him, filling him with a desire and a longing that he had not known for some time, a yearning which reached beyond his skin and bones deep into the core of him. “Why do I know this place?” he asked her.

Equally spellbound, she answered, “Legend held that this is where our parents’ great rivalry began. They say that beneath the Erechtheion lies the three marks of the sea god’s trident, under the branches of the very first olive tree.”

“Here, you say?” How extraordinary. Here was the spot which would come to define their antagonism, a mighty tree the seeds of which were planted thousands of years ago, far beyond the memory of any living man, recorded in stone and letter. Here they were, two souls adrift in the uncaring winds of time, and yet, together, they had come full circle, to the place where it all began. Who of the ancient Athenians could have guessed, all those generations ago, that their choice of patron would shape the course of history, as a river through a valley? Who among them would have known how their decision would take root throughout the years, until it blossomed within Percy and Annabeth, children who, despite following the same gods, would have been as total strangers to them? The thought filled him with an emotion he could not quite name, only that he knew he was glad for her presence.

“Thank you,” she murmured, as quiet as a breath, “for looking after me. I am sorry to have dragged you here on nothing but a whim and a wish.”

Acting on some instinct he did not know he possessed, he reached down, and took her hand. It was warm in his, her heart beating strongly through the tips of her fingers. “Think nothing of it. We two must stay together, should we not?”

“We should indeed.”

She looked on him without any distaste or annoyance for what must have been the first time in a very long time, and it sent a warm thrill through him, as though the shadows around them had receded, bathing the two of them in sunlight. “I have been thinking,” he said, inspired by this place and this time and the thought of their legacy. “If indeed, the gods that we know and worship have truly… have truly gone,” and his voice grew thick at the thought. He cleared his throat, and was grateful she did not comment on it. “Then we should continue to travel together. This truce that we have struck, it has proven beneficial in more ways than I could have predicted, and if we are to survive whatever comes next, I have a feeling that we should stay together. If you agree, Annabeth, let us, here and now, tie off these threads of our history, as one would to a tapestry. Let us end this rivalry of ours.”

She looked at him, a cascade of feelings crossing her face, too quick for him to name, until she settled on something which he would define as apprehension, perhaps. Gazing into his eyes, she searched for some hint that he would betray her, he supposed, though he could not blame her for it. His proposal was a novel one, and bold as well. Should her mother get word of this agreement, Annabeth could find herself in deep trouble, as Athena’s hatred of Percy himself was no secret.

This close, the setting sun seemed to reflect in her eyes, transforming them from steel to silver, a kaleidoscope of glittering stars. This close, he realized he could trace the flush on her cheeks as it traveled towards the crooked bridge of her nose, and he saw that there were freckles there, beneath the tanned skin.

“A plan worthy of Athena,” she said after some consideration. “I agree to your terms.”

And thus, it was ended.

“To think,” he murmured, “that such a legendary rivalry could have been resolved so easily.”

“It is strange,” she admitted, “that along with my mother and our ancestral home, I have lost this as well.” And she looked out over the city, despondent.

He frowned, as he did not think of their antagonism as something to lose; rather, he felt as though the ancient fields had been overturned, the old soil furrowed, giving way to new and fertile ground, full of endless possibility.

“Well,” he said, hoping to put a smile back on her face, "my first act, in the shedding of our rivalry, is to pledge myself to our future empress, Ana Zabeta Palaiologina." Then, in a fit of insanity, he raised her hand to his lips, and laid a kiss there.

She did not smile at him; rather, she rolled her eyes, pulling her hand from his grasp, and wiping it on the front of her dress.

“Where to then, your majesty? The Morea?”

“Enough,” she said. “I had given up that plan some time ago.”

“Oh?”

“As you and I have both noted, the despotes will not give us the army that we seek, nor the Legion, nor any of the rulers of this Christendom. I fear,” she sighed, biting her lip, “I fear that Constantinople is lost to us forever.” She looked to him again, clear eyes shining. “We have lost, Perseus. The gods have gone, the empire has fallen, and we have lost.”

And that, he supposed, was that. The reign of the Olympians was ended. They were well and truly alone.

But, he thought, at least they were together.

“What now?” Endless possibility, he thought. How frightening. “Do we look for the agoge ?”

“I do not see how we can,” she admitted. “Chiron could be anywhere, and I have not the faintest idea of where to begin.”

Neither, unfortunately, did he. They could have been anywhere in the world, but the world was a vast, vast place. “Let us find some place to rest. Tomorrow, we can decide what to do, but tonight, we have earned our respite.”

Their business thus concluded, they wound their way down the cliff, to the city below, in search of some place to rest their heads.

It was not terribly difficult for them to find an inn. Claiming tiredness, Annabeth bade him to go and get them something to eat. “Anything in particular?” he asked.

“Something cheap,” was her perfunctory response. Collapsing onto their shared bed, which was, unfortunately, the only one which had been available in that particular establishment, she turned away from him, curling into herself, and sensing the dismissal for what it was, he left her to it, setting out for food.

Immediately, he wished he had been able to entice her to come with him.

Athens in the evening was quite beautiful. The air had cooled considerably, the low light casting the homes and streets in shades of red and pink and gold. It was smaller than he had expected the great city to be, however. He had been expecting something grander even than Rome, or the city of Constantine, yet what he saw put him more in mind of a small, backwater town. Even to his untrained eye, the buildings were mismatched and patchwork, different styles of marble sewn together haphazardly, unsymmetrically and non-uniformly--a cardinal sin, he gathered, to the keen mind of an architect. From the way Annabeth had spoken of it, Athens by rights should have been the virtual center of the known world, the shining jewel of Hellas and beyond, as it had been in centuries long past. Whatever it may have lacked in people or in great thinkers nowadays, however, there was at least plenty of food to be found. The air here was thick with the heady smells of garlic, salt, and onion, transporting him back to his childhood home, to his mother and her kitchen.

Gods, his mother. In all this time, he had not even spared a thought to her or her husband or their daughter. He had sent them from Constantinople prior to the siege, but he did not know where they had landed. Were they safe? Healthy? Had little Esther been able to sleep through the night without being plagued by any more nightmares? Was his mother able to make her pastries still, with cinnamon and mahleb?

Would he ever see them again?

Without much conscious thought, his wanderings brought him to a stall on the edge of the populated area, every inch covered in reams of fabric, richly hued, in shades of copper and cream and grey. He had passed by hundreds others just like it, so he was not certain why this one had caught his eye. Perhaps coming across this particular stall had simply coincided with an idea he had been concocting, a coincidence of good timing and sudden fortune. Perhaps it had been the length of blue cloth he had seen behind the elderly woman who sat in the center of her tent, eyeing him warily. “See something that piques your fancy?” she asked, though she made no further move to greet him.

“Oh,” he said, “no, thank you. I was merely looking.”

“Finest cloths in the city,” she said, a bold claim, he thought, since he was quite certain he had seen these exact fabrics on display in every little tent he had come across so far. “I make them all myself.”

“I do not have much in the way of money,” he said, hoping she would leave him be.

Oddly enough, that only seemed to excite her. She turned over her shoulder, pulling the bolt of blue down from behind her, and holding it out to him. In the evening light, he thought it might resemble the color of a starless sky, a deep, inky blue. “You have good taste--this color is very fashionable these days.”

“Truly, I have no money,” he said, even as an absurd thought began to form in his mind. The color, he thought, that blue, it would look quite beautiful set against a certain blonde braid.

She sighed. “What do you have?”

“Huh?”

“The malakes noblewoman who ordered this from me has declined to send someone to retrieve it for her for several days now,” she said, “and so it sits in the back of my stall, unsold and taking up valuable space, when it could be in your hands instead, or draped around the shoulders of your beautiful wife.”

Percy blushed. “She’s not--I mean--”

“But because I am a generous businesswoman,” she interrupted, smirking, “show me what you have, and we may be able to come to some arrangement.”

The way she looked at him, all-knowing and altogether too familiar, compelled him to obey. Counting his coins, he laid out his paltry offering before her, the smattering of silver stavrata, Venetian lira, and smaller, duller bronze coins making for a pitiful display, when his fingers fumbled, and a golden drachma tumbled out of his hands, coming to rest before her.

He froze, praying that she would not see it, or if she did, that she might mistake it for an Italian florin, and leave it be.

Naturally, of course, that is what she picked up, her eyes settling upon it almost instantly.

“Well, well, well,” she said, looking at the coin with curiosity. “It has been some time since I have seen one of these.”

“Ah,” Percy started, flushing. That coin was not meant for mortals, and they had precious few of them to spare. “That--I--that is to say--”

“If you are looking for the gods,” she went on, peering at him with new eyes, “I could have saved you the trouble. They are not here. In truth, they have not blessed this land with their presence for some time.”

He blinked, astonished.

With a kindly smile, she tucked the drachma back into his coin purse, swiping some of the lira for herself. “I think this makes for an adequate trade, no?”

Still, he was rendered dumb and speechless.

“Keep an eye on your money, traveler,” she said. “You never know if you will find more.”

The noise of the city was dwindling, down from a lively hum to a low murmur, and the light turned even cooler as the cold moon rose over the cliff. Annabeth would most likely be worried at his long delay, or at least starving. But he could not force himself to move yet. “You’re--” he stammered, “you--”

“Yes, child,” she said. “Now, you should be headed off. The guards do not take kindly to stragglers wandering the streets so late at night.”

There were a million things he wished to ask this woman, important things, questions of ancestry and whether or not there were more of their kind nearby, but all that he was able to say was the terrible, sad news that he carried within his heart. “Constantinople has gone,” he said. “The agoge has vanished.”

Bittersweet, she smiled, folding the shawl for him into a tight bundle. “I know.”

“You do?”

She nodded. “I had a dream.” And thus, she bade him good night.

In a daze, Percy wandered back to the inn where they were staying. On his way back, he had stopped to purchase some food like he promised her he would, settling a loaf of hard, cheap bread and some kefalotiri , as that was all he could afford, but at least it would tide them over for the night, until they decided on the next course of action.

When he returned, Annabeth was no longer lying prone on their bed, but sat upright, her back against the wall, eyes closed. She opened one as he entered, her hand automatically sneaking towards the folds of her dress where he knew she kept her knife, until, upon recognizing him, she relaxed, letting her hand fall back down to her lap.

“Here,” he said, placing the parcels on the bed between them, though he kept the shawl tucked away against his chest, for now. “Dinner.”

“Thank you,” she said, quietly, taking the bread, picking at it with her fingers, slipping the teeniest of bites into her mouth. After some time, she noticed that he was not following suit. “You’re not eating.”

It was not a question. “Ah, I ate mine as I returned to the inn,” he said, easily.

She stared at him, not at all convinced.

“In any case,” he went on, eager to change the topic, “I have been thinking about what we should do next.” He had done nothing of the sort, but hopefully it would take her mind off of the obvious.

“So have I.” She put the bread aside, drawing her knees up to her chest, and hugging them. “I would like to go home.”

Percy frowned. Surely she did not mean Sigeion . She had already indicated her feelings towards the search for Chiron and the rest of camp, namely, that it would be a useless, fruitless, frustrating search, and surely she did not mean Constantinople, lost to the ages. What other home was there?

“You know that my mortal family does not hail from here.”

“I do.” It was not a piece of information well hidden; one only had to look at her pale skin, her blonde hair, and her looming figure to know that she was, in all likelihood, not one of the Hellenes by blood.

She would not look at him, her fingers tapping random patterns over the fabric of her dress. “If he still lives, I should like to see my father.”

“Oh.” That was… unexpected. To anyone who knew her, there were a few core tenants of Annabeth as a person; her love of architecture was one of them, and her distaste for her father was another.

“When I--left him, he lived in a city called Uppsala, far to the North of here.”

“How far?”

She gave him a rueful smile. “Svealand.”

Well. That was indeed quite far. “You mean to travel to Svealand? On your own? That would take near on half a year.”

“To the East of Constantinople, there is an old trading route once used by the Norsemen to travel between their lands and ours,” she said. “A river by the name of Danapris .”

“A river?” he asked, skeptically.

“One that spans nearly the entire continent. In the time of Basileios II Porphryogennitus, this was the route which delivered his legendary Varangian guard. I know for a fact it has fallen out of use, and the tribes of the Kievan Rus’ no longer roam that area.”

He had never heard of those people before--not that it mattered. “Annabeth, it does not matter how fearsome and ferocious you believe you are, you cannot travel all the way to Svealand by yourself.”

She scowled at him, lips pulling back into a snarl. “I have done so once before.”

“The whole road? By yourself?”

“Well,” she hesitated, “no. Not the whole thing. But I traveled some of it, before Thalia found me.”

“Be that as it may,” for he knew she would attempt to traverse the whole way by herself, merely to spite him, “as Thalia once did for you, let me do as well. I shall accompany you to Svealand.”

Her eyes widened. “Percy, no. You should be looking for Chiron.”

“As you yourself have said, he could be anywhere,” said Percy, “and I may have all the time in the world to find him. In the meantime, I should very much like to see you safely returned to your father.”

“I told you, the road is long since abandoned.”

“And you’ll forgive me if I am skeptical of that fact. Not of you,” he said at the look on her face, “nor your vast pools of knowledge, but even you cannot predict whether or not you shall meet trouble along the road, and it would comfort me greatly if I were able to come along.” Sourly, she opened her mouth as if to argue, but he interrupted her. “Annabeth. You cannot convince me otherwise. I am coming with you.”

Eyes narrowed, she glared at him, before acquiescing. “Fine.”

“Good.”

“Then we should rest. We shall leave at first light on the morrow.” On that abrupt note, she flopped down onto the bed, turning over once again, her back to him. “Good night, Perseus.”

The air was charged between them, with what he could not say, though he could nearly feel it shaking, as taught as bowstring. “Good night,” he said in response. Then, blowing out their room’s solitary candle, he laid himself down to sleep as well, his back to her, and thought not of the bundle of cloth he had purchased on a whim, not of how her golden braid might look against the dark blue fabric, and not of the sweet smile she had given him in the shadow of the Erechtheion. No, he thought of none of these things. Not at all.

#pjo#percabeth#the rivalry ends here#the marble king#my fic#idk why i keep posting these bc no one is reading them lmfao

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LONG & WINDING ROAD

Time to leave the gorgeous Kyparissi as want to look at Napflio on the way back to returning the car to Piraeus tomorrow. This is the one downside of pre booking. Yes it provides certainty but creates time and scheduling restrictions.

Breakfast again at the Trocadero cafe trying to best position ourselves on the terrace to take full advantage of any breeze. Then time for the amazing drive to Napflio. Passed the concrete apron harbour on the way back from breakfast where a fishing boat had pulled in. This was the local fish shop. If you fancied a fish dinner, wander down see what the catch is, do the exchange and all sorted. John and Mary were down there too and had already bought their red mullet for dinner. They invited us to join them but sadly not possible so said our goodbyes and we were off. Kyparissi is just one of those little gems that you feel you could rent an apartment for a couple of weeks and totally relax away from the world.

The drive again was a slow one being 135kms but according to Google Maps would take 2 hours and 55 minutes to complete. No doubt it took us longer - it usually does for various reasons - a bit of faffing, little stops here and there, view stops...you get the picture. It treated us to some serious hairpin bends (on which we consistently seemed to meet another car coming the other way despite the light traffic) and magnificent views. The first third of the journey was along some rugged coasline above the sparkling azure sea as we climbed the mountain. Then inland through rustic inhabited little villages but no sightings of evidence of life. Then more winding down the mountain to Leonidio then along the coast to Napflio.

Along the way we passed some inviting little getaway coves such as Fokianos Beach and hamlets, the likes of which we may well have stopped at during our open-ended 2014 holiday indulgence . But with Greek islands being a popular destination in July we’d locked in the next 8 days until 19th July by pre-booking ferries and accommodation. Still, we have left the 19th open so we can switch countries, island hop, stay on at Milos...all yet to be decided.

Napflio is a very historic city but time restrictions and blazing heat didn’t allow for much exploration. A quick beer and freddo cappuccino (my refreshment of choice this holiday, Chris’ is anything with alcohol) followed by an icecream (beer with an icecream chaser, that very sensitive stomach can be admirably robust at times) and we parted ways. Chris for some reason went to the new part of town which he reported was unsurprisingly dull while I pottered around the cobbled back alleys of the old town. Of course there were the usual cafes, icecream vendors and tacky tourist tatt. But amongst all that were tasteful shops selling jewellery, shoes, bags and clothes. I found that dress I was looking for in London - a loose casual Italian linen number. I expect it will look right at home on the Greek islands but not sure if I will look totally naff wearing it to Piedemontes.

Not only did I come away with the frock, I also had a wonderful exchange with the saleswoman. She was flapping about in her own linen ankle-length dress extolling their comfort as she sat braless with a manspread. We laughed about getting old, how much plastic surgery is too much, fat legs, chubby saggy knees and basically how we old gals ain’t what we used to be. She had also lived on Milos so gave me a couple of tips on places to visit. All in all a thoroughly enjoyable 45 minutes.

Regrouped for dinner but pre-drinks were a priority seeing most tavernas don’t stock spirits. Found a pumping little bar on a street corner proving a first rate people watching possie. Now about 9.50pm - not late to eat by Greek standards - so went to a little out of the way place I’d spotted earlier on the day down a pretty narrow lane flanked with cerise bougainvillea. Earlier we had also walked along the ‘Lygon Street’ of Napflio complete with bazouki players (nice but a tourist cliche) cafes with pictures of menu items on the walls (a definite no) endless bowls of chips (since when have chips been authentic Greek food?) and people dodging and shuffling by as you try to enjoy your dinner (can I pass you a chip as you stick your butt in my food?).

Our choice was spot on with a fabulous moussaka for me while Chris had grilled swordfish, sautéed potatoes (no chips) and a mini Greek salad and devoured it all. Even the white wine was passable but sadly the rosé was not. So the very good food with a 1/4 litre white and a litre of mineral water was €25 ($42?...). Bargain.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Odyssey’s end: exploring Milos and Sifnos, Greece | Travel

Dawn was breaking as I swam out from Paliochori beach. Twenty metres offshore, in the first rays of sunlight, I could see bubbles emerging from the sea bed. There was a roaring in my ears, like Poseidon’s kettle about to boil, plus some alarming gusts of warm water. Island of Milos, I thought, you are full of surprises: a volcanic Jacuzzi in the sea itself. Then I got out of the water and walked up the beach barefoot, straight into my second surprise: a thorn bush.

Milos & Sifnos

I yanked out every single one of the finger-long spines, but the last one broke off in my ankle. An hour later I couldn’t put my foot down. Was Milos having a joke? Anyone for island-hopping?

Milos was the fifth stop on my exploration of the lesser known Aegean islands, a journey that has revealed the wonderful diversity within those specks of land scattered between mainland Greece and Turkey. But Milos, I was fast realising, is different on a wholly different scale: starker, sharper and sometimes downright weird. There’s a beach only accessible by ladder, a taverna that stands in the sea and strange rock formations everywhere.

I was staying in a lovely hotel, Villa Notos, tucked into the cliffs on the outskirts of the port town of Adamanatas. My next few days were supposed to be spent hiking, but that prospect now seemed unlikely. Elena, the hotel owner, dug around in my ankle with a needle and declared the thorn too deep. I caught the bus up the mountain to the hospital where a stern-faced doctor spent 10 minutes exploring the interior of my ankle with a longer needle, then told me there was no thorn. I agreed: anything to escape his alarming ability to withstand pain, in other people. I could feel the thorn. I named it Odysseus and put a plaster on the livid red scar where he had entered the Trojan horse called Kevin.

Clambering down the ladder to Tsigrado beach on Milos. Photograph: Kevin Rushby/The Guardian

Elena at the hotel was determined to find things I could do while hosting Odysseus. She called her friend Dimitrios, who had the keys to the caves under the hotel. I only had to hop down two flights of steps and there was Dimitrios next to a huge iron door that I hadn’t noticed before. We entered a long tunnel in the rock and walked into the mountain.

“In the second world war,” Dimitrios said, “the Germans occupied Milos because of its natural harbour. They tunnelled into here to create stores and a hospital.”

For years after the war the tunnels lay empty and unused, a warren of cool caverns, crying out for a purpose. Now Dimitrios and friends have started putting on art shows, which add surreal touches to some of the spaces.

I went up to see Elena. “Sit down on your terrace and we’ll bring you food.”

In the tunnels below Adamanatas town, Milos Photograph: Kevin Rushby/The Guardian

Elena is Greek hospitality incarnate. Sit in front of her impressive desk overlooking the little beach below and before long coffee and cake will appear. Give it a little longer and some fascinating story will emerge, maybe about her great grandfather, who refused to surrender his pistols to the government and was named after his moustache – I’m summarising. Homemade cheese pie came on a tray with coffee. Later a bus timetable and map arrived, along with a message. I was to go to the costume and cultural museum up the mountain at Plaka.

The bus services on Milos are excellent. I rode up the hill, then limped through the labyrinthine lanes of Plaka. Down by the sea you might find “happy hour” bars and souvenir shops, but Plaka feels authentic: family houses, children’s toys in the alley, cats, a few good restaurants and bars. One of the houses has been turned into a museum. It’s a tiny place and you could easily miss it. There are no videos, no interactive exhibits, not even a demonstration of anything. Were it not for Odysseus, I would never have gone, and never met the custodian, Iro. “Elena Gaitanis sent you? Did you know her surname means ‘curly moustache’? Let me show you her great grandfather.”

His photo was on one wall: a piratical outlaw in giant pantaloons, pistols in his belt and that eponymous moustache. No wonder that when the island governor had demanded he surrender his pistols, Gaitanis had sent word: “Come and get them.” But nobody dared.

Iro (left) with visitors in Plaka’s cultural museum. Elena’s great-grandfather is in the photo on the wall. Photograph: Kevin Rushby/The Guardian

With Iro as guide the museum was a revelation, a window into the former life of the island. She told me how every evening in Plaka would end with each housewife calling in her chickens by name, showed me the surprising dresses women wore for their wedding nights, explained how the priest got his daily bread, and so on and on. Each time I was about to leave, she yelled, “Stop! There’s one thing I must show you.”

Eventually I hobbled away and climbed steps to the top of the hill, the fort, where I enjoyed the magnificent view and took off my boots. The plaster was intact. Another bus ride took me back to sea level and the wonderful Klima, a series of colourful boathouses dug into the cliff. I swam and fell asleep on a bench. Next morning Elena enquired after my ankle. The plaster had survived one swim and two showers. Odysseus had gone quiet. I could walk again, and island hop too.

The last island on my adventure was Sifnos, a 50-minute ferry ride away. It loomed up on the horizon, looking massive and forbidding and far quieter than Milos. I stayed at Delfini, a friendly little hotel on the rocky coast within walking distance of the port. I took a rest day for the sake of my ankle and then set off at 5am on what I had decided would be my last and most ambitious yomp of the trip.

I climbed the vast mountainside opposite the hotel in semi-darkness, crossed a windy ridge and then took an ancient cliff path through crumbling antique terraces fragrant with juniper, thyme and sage. I drank from springs and explored abandoned villages. Lizards and partridges scattered before me. At midday I reached Vathy, a seaside village popular with French tourists.

Kevin on the trail on Sifnos

After a swim I chose the simplest taverna and ordered revithada, chickpea stew, a Sifnos speciality. George, the owner’s son, talked proudly of the island’s culinary traditions. “When people have a cooking question in Greece, or they want a recipe, they say, ‘look in Tselementes’. It’s a book – the book. Tselementes has come to mean fine cooking. But Nikólaos Tselementes was a real person, a chef from Sifnos.” (He wrote an influential cooking series in 1910 called Odigos Mageirikis but his name has become a synonym for “cookbook.”)

George brought me caper salad, another Sifnos delicacy. Eventually I dragged myself away and continued walking, now in stunning heat, over a couple of hills and down to a deserted beach at Fikiada, where I collapsed in the shade after a swim.

Later, in golden evening light, I found some spectacularly ancient olive trees, hollowed-out giants that might have been saplings when Alexander the Great was alive. The oldest olive tree in Greece is said to be more than 3,000 years old.

George and his mum, owners of Taverna Symposio at Vathy on Sifnos. Photograph: Kevin Rushby/The Guardian

I walked on and on until dark, then caught the last bus home. My Greek walking epic was finished.

It had been a wonderful and inspiring journey. Behind its success lay a comprehensive and reliable ferry system (it never failed me), and a dependably hospitable roster of small family-run hotels. I never ate fancy or expensive food, often happy with pies from the bakery or a salad. It was the simple things I enjoyed most: the morning light, the sun-blessed tomatoes, the antique cobbled paths, the cool swims, the falcons playing with the wind.

Every morning at dawn I pulled on my boots, eager to get outside and see what the day would bring. And they all brought sheer pleasure.

Except, of course, for Odysseus. That accursed wanderer came back to England with me, hiding under the miraculously tenacious plaster. And then, when I first got in a car to drive, as if in horror at the end of my glorious summer of walking, he protested. I reached down, ripped that plaster off, and there, stuck to the surface, was a grisly black thorn, a centimetre long. Odysseus had made his point: my island-hopping was over – for now.

• Accommodation was provided by Inntravel, whose three-centre, ten-night, self-guided Enchanting Cyclades walking tour starts at £915pp, including B&B, notes and maps, transfers between ports and hotels and an internal flight Milos to Athens. Book ferries at ferries.gr; Folegandros to Milos €39.80, Milos to Sifnos €15, Sifnos to Piraeus €50. Accommodation in Athens was provided by The Foundry Suites (apartments for two from £102)

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to see a range of fantastic trips

The post Odyssey’s end: exploring Milos and Sifnos, Greece | Travel appeared first on Tripstations.

from Tripstations https://ift.tt/2U1Qxd0

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Asclepius the God

It is a long time since I last posted here. I have to find some flow again, so please forgive me if the following is a bit disjointed. It also starts with a physical ailment, which is uninspiring (and elderly), but it is merely a way in…

I have, for some time now, been suffering from lower back pain. It’s nothing dramatic, just a constant dull ache. But it is enough to kill my enthusiasm, in a very general way. Taking the dog for a walk, watering a plant… they become an effort rather than a pleasure.

There are different theories about the etiology of lower back pain. Some people say it is stress related (and, in my case, it came on at a time when I felt very tense). A friend of mine who is a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicine was more precise: it is specifically related to money trouble. The spine specialist in London was true to his scientific roots and diagnosed, with the help of an MRI, ‘mild joint effusions at L 4 – 5’. I asked him about the effects of stress. He said that stress and tension could make a problem worse, but that they could not be the cause of it.

I saw a chiropractor and an acupuncturist, neither of whom were able to effect any lasting improvement. In the end, the spine specialist prescribed painkillers, anti-inflammatories, and a course of physiotherapy. I followed this conscientiously over a period of months, also to no avail. Eventually, I went for an expensive cortisone and anaesthetic injection into the spine. The symptoms went away for a month, but as soon as those chemicals were no longer present in my back, the pain returned. I began to feel that I would just have to live with it; manageable, but joyless.

Here in Athens, a friend told me about about an ‘energy healer’ who had helped her a lot, and who was in any case an interesting individual. I thought to myself that I had nothing to lose, and I asked her for the healer’s contact details.

A week later, on a cold and drizzly February morning, I rang Iannis’ doorbell on a street in Pangrati - a comparatively quiet area of central Athens. Iannis came to let me in. He was a diminutive, smiling man in his late sixties or early seventies, with a lively, engaging manner.

We went into his apartment which was small, modern, and perfectly ordinary. On the walls were a few of those tricksy landscape paintings that are sold by street artists. I was about to launch into a description and history of my complaint, which so far I had not told him anything about, when he stopped me by holding up his hand. ‘Let me diagnose you,’ he said.

I then stood in silence, fully clothed, in front of Iannis, while he put his hands lightly on my shoulders for a few minutes. Eventually he said, ‘You have lower back pain, a problem around vertebra 04, and you have had trouble with your right knee in the past.’

I was blown away by this. He was right about the knee too, it was a rugby injury that had plagued me for about 2 years. While driving, the pain used to force me to stop the car every half hour to stretch my leg. But that was more than ten years ago, and since then I have not had any knee trouble.

‘Do you also sometimes feel that your heart beats irregularly?’ he asked. ‘No,’ I replied truthfully, and my belief in his omniscience diminished a little, though it is possible that he is right and I am not aware of it. He then said that my lungs were not breathing properly, owing to a problem some time ago. This is also true, I got pneumonia a few years back. He seemed to think that this was the more serious problem, since it affected the amount of oxygen in my brain and therefore also my general mood. But he thought that he would be able to treat all of these problems. When I asked how many sessions would be necessary, he blithely replied, ‘Just one.’

Iannis told me that he used a form of energy manipulation. ‘Like Reiki?’ I asked. ‘A bit like Reiki,’ he said, ‘but this is an ancient Greek technique, in the tradition of Asclepius, the God of medicine and healing. It is not written down anywhere. It has been passed down through generations of practitioners, but there are not many of us these days.’

Iannis told me to lie down on my back on his sofa with my eyes closed while he performed the energy manipulation above me. He told me to report anything I saw or felt, particularly any colours I saw. It lasted for about half an hour. Frankly, I did not see or feel a lot. Perhaps some warmth in my hands, and a slight vibration in my solar plexus. I saw a few greens and reds, but I could never be quite sure that I wasn’t imagining them, or willing them into being. But each time I reported a colour or a sensation, Iannis would respond with an encouraging, ‘Yes, very good.’

The treatment ended with the painful massaging of three pressure points, two on my left foot, and one near my heart. Then he asked me to stand up and walk around the apartment. I did feel a lot better, though the pain from my back had not gone completely.

I asked Iannis how he had performed the initial diagnosis. He said that it was by knowing himself very well, and then by sensing the energy of another person through various sense modalities, including sound and smell. He said that it was not so much a gift as the result of single-minded dedication over a lifetime. He reiterated that what is absolutely fundamental is self-knowledge; only on that basis can one come to know others. That is rather what I think about psychotherapy.

I paid 70 Euros and left his apartment. It was still raining outside, so I decided to wait it out and treat myself to a coffee. As I sat in the café, the ache in my lower back returned, as persistent as it had ever been.

*

Some months later, I felt I needed to escape the summer heat of Athens. I got on my motorbike for a weekend trip to visit some of the Mycenaean sites in the Peloponnese. The Mycenaean culture was dominant from about 1600 - 1100 BC; it consisted of a number of small independent kingdoms – Mycenae, Sparta, Argos, Pylos, Tiryns, Midea, Thebes, Athens and a few others. This was the period subsequently made famous by Homer in the Iliad and the Odyssey. It is the factual basis for the myths and legends that he committed to paper between 500 and 1000 years later, and also the period that saw the birth of the first attested form of written Greek (called ‘Linear B’), which predated the Greek alphabet by several centuries.

I crossed the Corinth canal and then followed the small country roads down to ancient Epidauros. This was once a sanctuary of Asclepius - a site of pilgimage and the most famous healing centre in the ancient world. It comprised the temple of Asclepius, a hospital, a 160 room guesthouse, a bathing complex, a 14,000 seat theatre with near-perfect acoustics, and a sports stadium used for quadrennial games.