Text

The Finger that Points to the Moon...

I haven’t posted anything on here for over a year.

Why?

Well, I guess I lost some motivation. There have been ups and downs. The ups are hard to write about because they feel like they are beyond language, beyond reason even. I have lost faith in my ability to convey them. Zen would say, ‘The finger that points to the moon is not the moon.’ Words are pointers, and the gap feels wider than it was before.

Poetry, haikus, koans, riddles… maybe these are more effective ways of expressing something of the experience. Or music. Or maybe there is a style of narrative prose that can convey it without directly aiming at it. I think that’s possible, but I haven’t found it yet.

The downs are what they always were, though I am more aware of them now. I think I can sum up everything I have learnt about my inner life in four points:

1. I am aware that I suffer. There are days when I am inexplicably tense, irritable, frustrated, sad, lacking kindness and generosity. That is suffering.

2. I have come to realise that the cause is not outside myself. I cannot blame my suffering on other people, on a place, on my material situation. Even if I could adjust those aspects in any way I wished, I would still suffer, I would just do so in more luxurious surroundings, and in the company of saints and supermodels (could Mr. Venn find an AnB here?).

But although the suffering is internal, that does not necessarily mean that it is my fault. This is perhaps the most surprising thing I have learnt. It could be an inherited ancestral burden, or the manifestation of collective trauma from the past (which affects both victims and perpetrators). Or even, further back, because of the Fall – no literal geographical garden of Eden, but a slow divergence from our original divine nature.

3. I realise that the primary (though unconscious) purpose of many of the things I used to do was to distract myself from that suffering. I am thinking of entertainment in all its many forms, exercise, being busy, socialising, buying or owning things, drinking, taking risks, taking drugs. Even helping others can serve that purpose.

4. Based on the cracks of light around the door of my own experience, I am confident that there is a way out, and it is codified in the practices and methodologies of the world’s tried and tested religions and spiritual traditions. You don’t have to pick one. If you are open to it, which will happen when you are really fed up of suffering, then one of them will pick you. It’s a bit like the sorting hat in Harry Potter.

This doesn’t mean that you will never suffer again, but you can change your relationship to suffering, and thereby cease to create it or contribute to it.

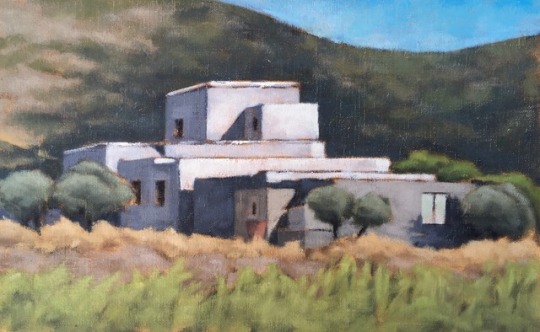

Those, I guess, are my four Noble Truths. In the meantime, I have been doing more painting than writing. This one is from the island of Paros in the Cyclades:

0 notes

Text

‘Be careful what you wish for...

…because it may come true.’ This saying has always perplexed me. Surely we want our wishes to come true? (So long as we wish wisely, that is). Who would willingly choose to be in an indefinite state of wanting? But I think I understand it a bit better now.

In my last post, I mentioned how I had felt restless upon returning to Athens last autumn. I visited Mount Athos for the first time in October, and that was an oasis of calm, but it also gave me plenty to think about. Maybe the peacefulness of the monasteries made me see things more clearly: back in Athens once again, my restlessness was all the more evident. And not just a restlessness, but an underlying malaise, an impatience, a sense that things were not quite right.

I was also able to recognise that this restlessness is something I have felt all my adult life. In the past, I have deployed a toolkit of strategies to avoid confronting it. Strategies such as intense exercise, or alcohol and socialising, or pursuing girls, or drugs, or (more long term), changing jobs, or moving from one country to another.

In the past, I have always blamed my restlessness on something outside myself. But now I live in a city I love, surrounded by people whose values resonate with my own, in a beautiful country, and my main occupation is one I have chosen freely, and that I often find deeply rewarding. And so I have to face the fact that the malaise stems from within.

So now I understand the saying, ‘Be careful what you wish for because it may come true.’ If it does come true, and you are still not happy, or at peace, then a very unflattering mirror is held up to you; you are forced to confront your own dysfunction.

One aspect of getting older is that patterns in your life become more obvious. When you are in your 20s and a situation occurs for the second or third time, it is still easy to blame the outside world. But when you are in your 40s, and you recognise that certain situations keep repeating themselves, you are forced to confront the fact that you may be creating them, or at the very least contributing to them. The disadvantage of this is that you lose the pleasing illusion of your own blamelessness; the advantage is that you now have the opportunity to change things.

Reading back over what I have written, it all sounds so clear and logical. But that’s not how it was at the time. Initially, I attempted to deploy the toolkit described above. But my lower back was still hurting, so I couldn’t escape from the malaise through sport and exercise. I went out at night, but the hangovers have become too painful. One night I stopped by the addicts in the park and bought some more of the local version of crystal meth. I felt great for 24 hours, and then predictably and deservedly terrible for a week. A girl I liked disappeared without a trace, and a subsequent perfunctory encounter left me feeling very empty. And only then did I fully understand: I need to address this, or I will never feel peace, and it will end up killing me, one way or another.

Last summer I had met a friend’s brother-in-law at a wedding. He claimed to work with plant spirits, and to channel their energies – from his home in Portugal - in order to perform healings; all he needs is a photo in which he can see your eyes. A few days before New Year he got in touch, casually, to say hello and ask how I was. I told him that I was at a low ebb, so he offered to perform a plant spirit healing. I felt I had nothing to lose, and that is why, on the morning of the 31st December, I was lying on the floor of my darkened apartment in Athens, listening to his Spotify playlist on my headphones, while sage leaves smoldered in the ashtray and my new friend in Portugal harnessed the spirits of his helper plants and sent them my way.

Did the plant spirit healing help? It is hard to say. Now, half a year later, I feel like a different person, with a new lease of life. But of course this is not a control experiment, and that might have happened anyway.

On the morning of the healing, back in December, I spent a couple of hours in a written whatsapp conversation with the plant spirit healer, for him to get to know me a bit better. It was a sort of diagnostic interview, with some very direct questions on his part. But he made some insightful comments and I found it genuinely therapeutic.

I admitted to the healer that I felt a lot of guilt about my own unhappiness. I am sympathetic to the suffering of all those who have been dealt a rough hand by life, but in my own case, is it not just the privileged self-indulgence of those who have nothing better to do? I have been blessed with loving parents, a good education, material means, and some mental capacity. With all of these advantages, how can I justify feeling miserable? Should I not be using them in some productive way, to create a better world?

The truth, of course, is that I have been trying in a modest way to do that for 20 years, and yet the malaise has always been there.

The healer’s response was a reframe that had the satori-inducing effect of the most striking koan: the crime is not to feel miserable despite worldly advantages. The crime would be if you failed to use those advantages to address and resolve your misery. It is possible that my soul was incarnated in this body, at this time and in this place, specifically because it provides me with the opportunity, the means, the capacity, and the precise challenges that I need for my own spiritual evolution. This is my fate, and I can embrace it and thereby progress on the only path that matters, or I can continue to try to fight it.

Another reason not to compound my malaise with guilt, the healer pointed out, is because our blockages are not entirely of our own making. This is the meaning of ‘inherited trauma’. Trauma does not need to be acute or dramatic or PTSD-inducing; it can refer to any form of malaise, unhappiness, discontent, frustration, mental suffering. It can run in families as well as in genders and races. My father’s depression and alcoholism will have affected me, as will the fact that my mother never had a relationship with her own father, and never introduced us to him while he was still alive. She never talks about it, but there must be a lot of sadness bound up with that relationship, and that sadness gets passed on. It gets passed on because your parents are the templates you inevitably copy, and also because it creates the emotional energy field in which you grow up. But it is important to remember that most parents do their best, and that their blockages and traumas have come from their own parents, and so on back up the generations. But if we don’t want to keep passing them on to following generations, then we have to commit to confronting them and dissolving them in our own lives.

The healer went on to mention a related but more mysterious concept: the shamanic 7 generational principle of ancestral healing. What we do in this life can, apparently, affect 7 generations of ancestors. When there is a lot of dysfunction in a family, it may fall to us to address that. The healer referred to it as ‘taking a hit for the team’. It sounded farfetched, even by my standards, but thinking back over the history of my family, it struck me that the lucrative forging of weapons over generations is unlikely to be karma-neutral (irrespective of attempts to offset it with workers’ welfare programs). I wrote a novel motivated by my desire to explore (and ultimately reject) the notion of inherited guilt, so this does not sit particularly well with me. And I certainly don’t think of myself as some sort of chosen one. However, I have long since ceased to dismiss things out of hand just because I don’t fully understand them.

To return to my darkened apartment on the 31st December: I listened to the playlist, trying to be receptive to the energy of beneficent plant spirits, and felt… not a lot. Although, I must say that over the next few days I felt more positive than I had done for a long time. But that may have been due to being less hungover than most in the early days of January.

They were cold, wet days in Athens, and I spent them ensconced in a few cafés, reading an author whose words resonated with the clarity of the finest Zen singing bowl. He is an author I had first heard of about a decade ago, but at the time I had dismissed him without reading him. I was wary of his popularity and hype; he seemed liked the worst kind of self-help guru. Back then I was a doctoral student in psychology, and I had no time for someone I assumed was a purveyor of ersatz spirituality. His name is Eckhart Tolle, and how wrong I was. And how arrogant. In January I read ‘A New Earth’, carefully, twice. It was a epiphany: he expresses so much that feels intuitively true, but which I have not yet experienced deeply enough for me to be able to live my life through the lens of that understanding.

His description of the collective dysfunction of the ego struck a particular chord. I remembered the pony-tailed South African shaman in Peru who, having fed me a glass of the noxious San Pedro cactus hallucinogen, told me to let go of my ego. It is not that I am particularly full of myself, or selfish, or ego-centric. Rather, like the rest of our Western culture, I have fallen into the trap of identifying completely with my thoughts and feelings, my likes and dislikes. I seek my sense of self through the things I possess and the way I appear to others, and I have lost my sense of who I am beyond that, which is what we all are: undifferentiated awareness, the universe becoming conscious of itself, and an expression of the divine. But read Tolle, or the Upanishads, or even (without blinkers) the Bible; they contain the same message, in different terminology.

If you look to the ego for your sense of identity, you are on a very unsteady footing. Talents, possessions, achievements, reputation; these are all fleeting. But if your sense of identity, of core self, is dependent upon them, it means that every time you lose something, or something doesn’t go your way, or you feel slighted, or that you have failed in some sense, then your identity is threatened. And that, from the ego’s perspective, is the very worst thing that can happen. It is enough to make daily life a constant nightmare, and that is what so many adults’ faces express.

Perhaps, if you read this blog, you might look at my life and think that I have lived it on my own terms. You might wonder why I write so much about ego, when the choices I have made seem motivated by an authentic search (at least I hope they do), rather than by the desire to acquire possessions or power or fame. And, on the surface, that is indeed the case. When I am by myself, in the places I love, I feel the authenticity of those choices, and a calmness can grow out of it. However, when exposed to places and situations where those values are not evident – hectic materialistic cities, ambitious and worldly people – then my confidence gets rattled and, on a deep and mostly unconscious level, self-doubt will spread its probing tentacles.

The area in which this happens most frequently, and most painfully, is in my relationship with my parents. On the surface, they have been faultless in always encouraging me to follow my heart, and never trying to force me to follow a path that would not have felt true. But that is on the surface. On a deeper level, I think I have sensed their unexpressed desire for me to be ‘someone’ in the eyes of the world, so that they can be someone through me. And they have these desires because they have not yet done the work – and probably never will – that would lead them to the knowledge that the eyes of the world are meaningless. I have picked up these subliminal messages from the way that they talk about successful people, or about the worldly success of the children of their friends. It is painful for me because it makes me feel like a failure, although my parents are themselves not sufficiently conscious to be aware of how I might feel.

I now believe that this phenomenon is what drives many people, and makes them miserable. Unless our parents are highly aware, they are still stuck in seeking happiness through achievements. When their own achievements fail to satisfy them (and achievements, being ego-based, can never satisfy us for long), then they look to their children for vicarious satisfaction. This places a burden on the children, and one which can never be fully resolved, since there is no limit to achievement: I have a friend who felt like he had failed because he won a silver rather than a gold medal at the Beijing Olympics! Children want nothing more than to feel loved by their parents, but if they think that parental love is contingent upon their own worldly achievements, then they are condemned to Sisyphean misery.

These realisations crystallized in the days following the plant spirit healing. Then, towards the end of January, I received a Facebook message from my cousin (on my mother’s side) in Australia. We do not know each other well; we are in touch once a year at most. He had been sorting through boxes of our grandmother’s stuff and had found a few photos that my mother had sent her over the years. He photographed a few of the images and sent them to me. They were photos I had seen before, but as soon as they came into focus on my screen, I was overcome with emotion. One photo in particular had me choking up: I am in school uniform, and my mother is visiting me during my first or second year at boarding school. There is such happiness, and such love, in her expression. And yet I was only 14 years old - I had not yet achieved anything in my life. I was struck by the realization that, on the deepest level, my mother’s love for me is not contingent on achievements, or success of any kind. It is a given, even if our respective blockages and egoic concerns can sometimes cloud the water. But the cloudiness is a distraction, and sediment will settle. To quote the ska artist Lord Tanamo, ‘A mother’s love is from creation, it is truly the greatest association!’

I spent a long time looking at those images. The fact that my cousin had sent them to me out of the blue seemed to be a confirmation of Tolle’s belief that, when you are aligned with the intelligence of the Unmanifested (as he calls it, but you could insert the One/ consciousness/ Being/ God), then the universe will give you what you need.

Over the next few days, I felt a lot lighter than I had for a long time. But I also experienced the recurrence of extreme sensitivity around my navel, so sensitive that it verged on being painful. I looked online, but it didn’t sound like an ulcer or a hernia, more like an energy blockage. I decided to return to Iannis, the Greek energy healer who practised an ancient Asclepian method, similar to Reiki, and whom I had visited once before, a year ago, for back pain (an encounter I wrote about in a previous post).

Dr. Iannis was just as I remembered him – small, curious, twinkly. He stood behind me and diagnosed low energy and a ‘reduced aura’. He did not pick up on the discomfort around my navel. When I mentioned it, he said that it had to do with psychology and the emotions – something very deeply buried, a trauma of some sort, possibly a birth trauma? He could not be more specific, but it was enough to make me pretty sure that the discomfort was connected to the photo that had moved me so much a few days before.

Iannis was confident that he could help. As on the previous occasion, I lay on the couch with my eyes closed while he moved his hands above my body. I felt a cool breeze on the backs of my hands and the tops of my feet – this, according to Iannis, was energy and not air, and indeed his hands moved so slowly that it seemed impossible they could create the breeze I was feeling. And as he had predicted, the umbilical sensitivity disappeared within a couple of days.

At the end of the session, I told Iannis about my plan to return to Mt. Athos, the Greek monastic peninsula, for a longer visit. I was quite proud of having arranged this, since I had written my first formal letter in Greek to request permission, and then sent it to the Abbot of the monastery. I am not Orthodox, and I wanted to stay for a whole week, so I had to present a convincing case, and I was happy to receive a positive response. I thought that, being a spiritual place, and far from the drugs and alcohol which had contributed to my low energy (or ‘reduced aura’), Iannis would be encouraging. But in fact, he was dismissive.

‘Mt. Athos is not such a good place,’ he said.

Many urban Greeks are dismissive of their religion. In the cities, the Orthodox church can seem materialistic, manipulative, and only concerned with lavish ceremonial regalia and pomp and show. But Mt. Athos could hardly be further removed from all that, surely Iannis knew that?

‘The problem with the monasteries,’ he continued, ‘is that there are no women.’

Ah, I thought, the usual accusations of homosexuality, pederasty, abuse… It seems a secular shibboleth to me, certainly I have never seen any hint of it in the monasteries I have visited. But my assumption was mistaken. Iannis continued: ‘Men and women are both composed of varying degrees of male and female energy. A man has some female energy, and a woman has some male energy. To be physically and psychologically healthy, you must learn how to balance these two energies within you. Retreating to an entirely male environment does not help you do that. In fact, it can do the opposite.’

Well, it is an interesting theory. I have by now met a small number of inspiring monks on Mt. Athos who seemed pretty centred and balanced – certainly happy - but as far as my own energetic make-up goes, Iannis may have a point.

In any case, I returned to Athos in February, to spend a week at Iviron. At that time of year there are not many visitors. I had a small cell with a writing desk, and I spent most of the week reading and writing. One reason for returning to that particular monastery was that I had a circuitous introduction to a Greek-American monk there (via the wife of the brother-in-law of the monk’s brother, who – somewhat incongruously, or perhaps not - is a US marine). But I managed to track Brother Eugenios down and he is a delightful, inspiring man. He is in his mid-30s, highly intelligent and thoughtful, with a doctorate in theology and an astonishing memory. I met him for daily chats in the monastery library, where he also gave me some books about the Orthodox faith.

Returning to Mt. Athos

I got into the habit of attending Matins at 3.30am. I would usually stay for an hour or two and then return to bed, but the monks would push on through until dawn, some four hours later. Though I can’t understand the liturgies in Koine (Alexandrian) Greek, there is nevertheless something powerfully affecting about the bearded monks chanting by candlelight, incense heavy in the air while wind and rain batter the outside of the chapel. With very few exceptions, that same scene has been repeated in that place every night for the last 1000 years.

There is much that is very attractive to me about the Greek Orthodox faith. But there are stumbling blocks too. When I asked Brother Eugenios what the Orthodox Church would say about a healer who died some years ago on Cyprus, but whose healings are well documented (he is the subject of a book called ‘The Magus of Strovolos’, by the sociologist Kyriacos Markides), Brother Eugenios replied that the church would be very circumspect indeed. A religious elder would have to determine whether the healings occurred through the intercession of God, of whether it was the work of the devil.

‘But when the healings are effective? When sick people get well? Even then?’ I asked.

‘Yes, even then,’ confirmed Brother Eugenios. ‘The devil uses precisely such stratagems to trick people. That is why he is so dangerous.’

The Devil and his works... they have not played much role in the anodyne versions of Christianity I have encountered thus far in my life. But they are significant in the Orthodox faith, as are certain other darker aspects. There is a fresco on the far wall of the smaller Portaïtissa chapel at Iviron that depicts a river of flame siphoning the damned off into the jaws of a giant sea monster. Around the edges are stock medieval images of hell and purgatory. They do not make for pleasant viewing.

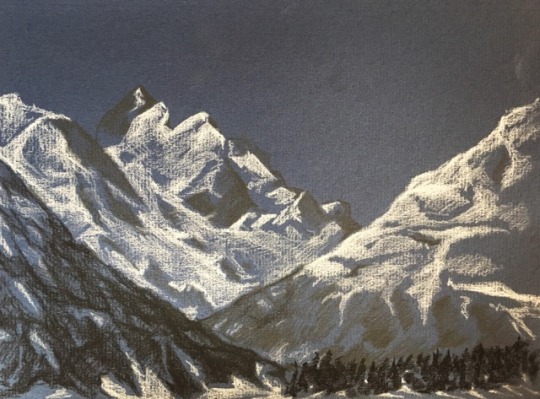

On my last night in the monastery it snowed, and the following morning I had to leave early to hike back up to Karyes, breaking tracks through the ankle deep snow. Mt. Athos shimmered in the distance, the forest around me slowly came to life, and thoughts of the Devil and his infernal sea monsters were soon far from my mind.

There was chaos at Karyes since the road was frozen over and the normal bus to the port of Dafni could not run. Replacement minivans were shuttling monks and pilgrims down the steep mountain road. Everyone had made arrangements, and was on busy schedules, and it was all rather confusing. But equally, none of it really seemed to matter very much, and I experienced a calmness and an inner amusement that I had not felt for a long time. And this time it has stayed with me, for the most part. I would like to think that it has been built on solid foundations.

0 notes

Text

The Holy Mountain

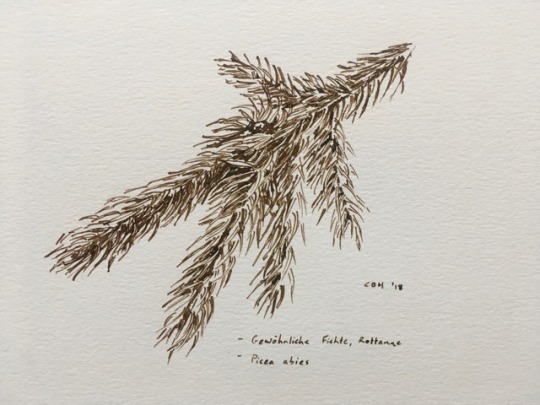

I spent a few weeks last summer in the Engadine valley in Switzerland. It is a place that has been dear to me since early childhood. In the Spinas valley, which forks off from the main Engadine valley, there is a footpath called the ‘Märchenweg’ – the fairytale path. Every kilometer or so, in a small clearing, stands a wooden chair carved from the trunk of a tree. The chair is surrounded by smaller tree segments that serve as stools. Inside the chair is a wooden file that contains the text of a fairytale from the area. Each story is printed in 5 languages – German, French, Italian, English and Romantsch, the local tongue that is a remnant of the Latin spoken by Roman legionaries stationed here.

These six little clearings, with their storyteller’s chairs, are paid for by the village council and have always epitomized for me everything that is best about Switzerland. I have written about them before in a previous blog, but the charm does not fade. They bring to mind the lovely German expression eine heile Welt – an unbroken world. For me, it is a counterweight to global politics, economic crises, climate change, refugees, pain in all its many forms. Back in August, I did a drawing of one of these circles of chairs. It felt very peaceful.

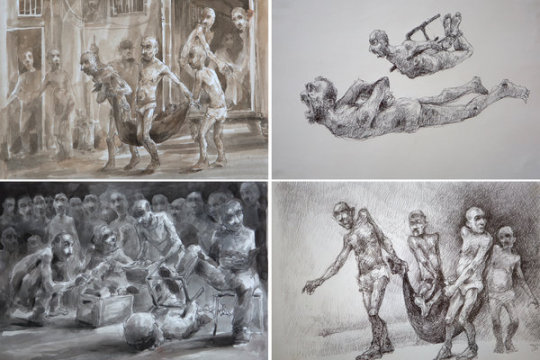

That same evening, I watched a short documentary segment in the Swiss news about Najah al-Bukai, a Syrian artist with a photographic memory who was held and tortured in one of the regime’s detention centres. He finally managed to escape from Syria, and now lives in Paris where he creates, from memory, haunting images from his time in the detention centre. Talking about his work, he says, ‘It is a personal therapy that allows me to evacuate.’ In an emotional sense, one assumes.

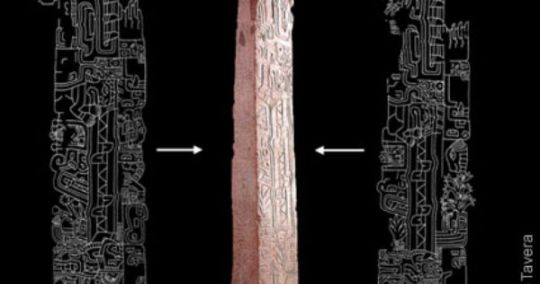

Drawings by Najah Al Bukai

After watching this report, I felt that my own work was embarrassingly frivolous by comparison. The feeling persisted for some days, until it dawned on me that although the outcomes could scarcely be more different, our motivations are similar: drawing, and art in general, as a form of therapy, and a way to find tranquility. With that in mind, I completed a few more small pieces.

*

Once back in Athens, I lost some of that Swiss tranquility. The summer is long, and the pleasure-seeking attitude that goes with it leaves a psychological hangover. This was the first anniversary of my life in Greece. The first 8 months had been busy, finding a place to live, and a place to work, doing them both up, taking my first steps in learning the language, and accumulating the thousand and one small objects that are required for a comfortable settled existence in a Western metropolis. The next 4 months had been summer, with friends visiting, and time spent out of doors. And now I had run out of excuses, and pocket money; I needed to knuckle down and get to work, and that made me feel… restless and unbalanced. Not that I wanted to be elsewhere, just that I was not accustomed to long periods of focused activity. That, and the underlying anxiety that my output would fail to live up to my aspirations.

Ironically, the one thing that my restless mind was able to settle on was the thought of restlessness itself; I kept coming back to this. We must surely live in the most restless of times. Scrolling through social media, multitasking, channel-hopping, budget travel… these are all expressions of our restlessness. It is not as acute in Greece as elsewhere, which is partly why I like living here, but it still exists. Very few people are unaffected - that is perhaps a lifetime’s work.

I sometimes think back to an older English lady I knew in Beirut. She was married to a Lebanese man. For some years they had lived in Dubai. She once narrated to me a particularly cherished memory: she remembered waking up one morning in their house in Dubai, the sun filtering through the curtains, her husband back from a business trip and fixing breakfast in the kitchen, and the sound of her two children playing in the garden. And at that moment, she told me, she felt at perfect peace. Everything she wanted or cared about was right there, within reach. She was, for once, free from desire.

It is a beautiful image, and an enviable one… ‘So far the poet.’ But what the narrative does not reveal is the transience. Her husband will go away on business again. Her children will grow up. Dissatisfaction will return. How does one address the root?

*

This is the background against which two significant things happened to me recently. The first is a book, and the second a short trip.

Over the summer, a close friend recommended Empire of the Summer Moon, an outstanding book by S. C. Gwynne, about the rise and fall of the Comanche tribe on the American Great Plains, towards the end of the 1800s. It has made me reconsider some of my most deeply held convictions.

Like most boys of my generation and background, I grew up admiring the cowboys of the old Wild West. They were brave, independent, steely men. They were fighting against savages whose custom it was to scalp people. And, I suppose, the cowboys were white and basically European.

Then, when I was old enough to question the cartoons and comics and movies that had shaped this worldview, I had to confront some nasty truths. The whites took the land from the Indian tribes, who had never believed in ownership in our modern sense anyway. The Indians had lived off the land, and roamed freely over it. The whites made treaties and broke them. They were driven by greed. Before the cowboys, there were Spanish missionaries who had attempted to impose their God – the same God in whose name much of South America had been enslaved – on an indigenous culture that lived in harmony with the natural world, and whose spirituality was a living breathing thing, not relegated to a clapboard Church once a week.

That is how I started to think. And corroboration was not hard to find. I read about C. G. Jung’s visit to Taos Pueblo in New Mexico in 1925. Jung met and befriended Ochway Biano (‘Mountain Lake’), the medicine man of the tribe. In Modern Man in Search of a Soul (1933), Jung quoted Ochway Biano:

‘See,’ Ochway Biano said, ‘how cruel the whites look. Their lips are thin, their noses sharp, their faces furrowed and distorted by folds. Their eyes have a staring expression; they are always seeking something. What are they seeking? The whites always want something; they are uneasy and restless. We do not know what they want. We do not understand them. We think they are mad.’

Yes, I thought. We are always uneasy and restless. And perhaps mad too.

Then I read Cormac McCarthy’s magnificent Blood Meridian, and it seemed that white moral supremacy was a myth too: the whites were also scalping the Indians on punitive missions. It was a bloodbath all round.

I read The Gospel of the Redman by Ernest Thompson Seton, a writer and wildlife artist who later became the founder of the Boy Scouts of America. In it, he records the dedication that a Tekahionwake Indian was expected to speak over the body of a deer he had just killed, and I was moved by it, much more so than the bland Christian ‘Grace’ intoned at school mealtimes.

To The Dead Deer

I am sorry I had to kill thee, Little Brother.

But I had need of thy meat.

My children were hungry and crying for food.

Forgive me, Little Brother.

I will do honour to thy courage, thy strength and thy beauty.

See, I will hang thine horns on this tree.

I will decorate them with red streamers.

Each time I pass, I will remember thee and do honour to thy spirit.

I am sorry I had to kill thee.

Forgive me, Little Brother.

I went on to study psychology, and focused on the psychology of shamanism, and traveled to the Amazon to explore an indigenous worldview that created a matrix of meaning in which myth, history, culture, medicine, ritual, cosmology, and the natural world all hung together in a coherent and purposive whole… and this is what the early missionaries had demonized as ‘devil-worship’! My own experience, naïvely romanticizing as it may sound, was that people are happier, calmer, and less neurotic the less exposure they have had to Western values. And the indigenous perspective often seemed much more beautiful too.

(for more on this, see http://www.clausvonbohlen.com/post/20467603477/what-can-we-learn-from-shamanism)

So, I have been pretty down on the ‘achievements’ of the West for most of my adult life (though nevertheless grateful for advances in medicine and dentistry, and appreciative of certain artistic achievements).

But Empire of the Summer Moon has given me a lot to think about. The book charts the rise and fall of the Comanche tribe, with a particular emphasis on the story of Cynthia Ann Parker. Cynthia Ann was the daughter of settlers whose small fort was attacked and overrun by a Comanche raiding party in 1836, when Cynthia Ann was 9 years old. She was taken captive, along with her younger brother, her 17 year old aunt and her aunt’s infant son, and another young woman called Elizabeth Kellogg.

Before being captured, Cynthia Ann saw her father scalped and her grandmother raped. Then the prisoners were tied to their Comanche captors on horseback. The Comanche rode hard to distance themselves from possible pursuit. When they camped for the night, the two ‘adult’ women - Rachel (17) and Elizabeth Kellogg - were gang raped in front of the children. Rachel Parker’s baby was eventually dismembered by being dragged around behind a horse. 9 year old Cynthia Ann went on to be adopted by a Comanche family, and eventually married a Comanche chief. Their son, Qanah, was the last chief of the Comanches, and the book also tells the story of his life.

But so what? A one-off story of brutality from an unusually vindictive Native American tribe, right? Well, that is what I would previously have thought. But, if the author is to be believed – and the book is an impressive and well-referenced work of scholarship – then this was not a one-off incident at all. Raiding and counter-raiding had been the norm for Indian tribes long before the first whites arrived. And raiding was always conducted with astonishing brutality: men who were not killed were invariably tortured, women were gang raped, and babies were generally skewered.

The picture that emerges from this book is one of a culture without anything that we would recognise as morality. There were certainly taboos, and spirits to be placated, but it is a far cry from the notion that I have long cherished, of peace-loving peoples living in harmony with each other and with the natural world. The author writes:

It is impossible to read Rachel Plummer’s memoir without making moral judgments about the Comanches. The torture-killing of a defenseless seven-week old infant, by committee decision no less, is an act of almost demonic immorality by any modern standard. The systematic gang-rape of women captives seems to border on criminal perversion, if not some very advanced form of evil. The vast majority of Anglo-European settlers in the American West would have agreed with those assessments. To them, Comanches were thugs and killers, devoid of ordinary decency, sympathy, or mercy. Not only did they inflict horrific suffering, but from all evidence they enjoyed it. This was perhaps the worst part, and certainly the most frightening. Making people scream in pain was interesting and rewarding for them, just as it is interesting and rewarding for young boys in modern-day America to torture frogs or pull the legs off grasshoppers. Boys presumably grow out of that; for Indians, it was an important part of their adult culture and one they accepted without challenge.

The first shock, for me, was the realization of the wanton cruelty of native Americans towards each other. The second shock was that they saw nothing wrong with this, as the following passage makes clear:

Enemies, meanwhile, were enemies, and the rules for dealing with them had come down through a thousand years. A Comanche brave who captured a live Ute would torture him to death without question. It was what everyone had always done, what the Sioux did to the Assiniboine, what the Crow did to the Blackfeet. A Comanche captured by a Ute would expect to receive exactly the same treatment (thus making him weirdly consistent with the idea of the Golden Rule), which was why Indians always fought to the last breath on battlefields, to the astonishment of Europeans and Americans. There were no exceptions. Of course, the same Indians also believed, quite as deeply, in blood vengeance. The life of the warrior tortured to death would be paid for with another torture-killing if possible, preferably even more hideous than the first. This, too, was seen as fair play by all Indians in the Americas.

I have recently been reading the Odyssey, and I have been struck by a similar absence of moral sentiment in it. At no point does anyone question whether there are any values beyond strength and skill. Even heroic Odysseus boasts about putting all the men of a city to the sword, and carrying off the women, just because he could. But we ought not to be surprised by this; it wasn’t until the time of Socrates and Aristotle, some 300 years later, that people first started to question whether might is always right (at least as far as written records reveal).

The parallel between Homeric times and Native Americans should not be surprising either: the Maecenean period that is the basis of Homer’s narrative was a late bronze age culture, whilst the Native Americans were – in terms of their technology - a stone age people. The two have a lot more in common with each other than with the highly organised, industrialized West that the white settlers represented.

S. C. Gwynne argues that morality as we understand it today is closely linked to complex social organization. But this kind of organization only develops when large numbers of people can live together in one place, and when they have the leisure to develop capacities which are not directly related to meeting the most basic human needs. Agriculture made this possible, but agriculture is something which the Native American tribes did not begin to practise until the arrival of Anglo-Europeans. Plains Indians such as the Comanche remained nomadic hunter-gatherers until the bitter end. If this theory is correct, it means that there is a direct causal connection between higher moral values on the one hand, and complex civilization on the other. Morality has developed in conjunction with the increasing complexity of human society. This was a big realization for me. For all of my adult life, I have thought that the opposite is true.

*

The second significant event was a trip, at the end of October, to visit Mt. Athos, the ‘Holy Mountain’ in the north of Greece. It towers over the tip of a peninsula that sticks out into the Aegean. The whole peninsula is an autonomous monastic region; women and domestic female animals are not permitted. The area is sacred to the ‘Panayia’ - the Virgin Mary - and it is also known as ‘the Garden of the Mother of God’. There are about 20 functioning monasteries on the peninsula, connected to each other by footpaths and dirt roads. Some of them were founded a thousand years ago.

Permits are not easy to come by for non-Orthodox visitors. I have wanted to visit Mt. Athos for some time, but in the end I could only go when they happened to have a permit to spare, though happily still before the winter. I was planning to walk from monastery to monastery in traditional fashion. Board and lodging in the monasteries is included in the cost of the permit, but you do have to book ahead. I set about doing this from Athens, but again, it was not easy – the monasteries only answer the phone at very specific times, for a couple of hours, and often in heavily accented Greek. In addition, it is hard to know exactly how long it will take to walk from one monastery to another, and you do not want to arrive too late since the gates are locked at sunset and remain closed until the following morning.

I approached this trip as if it were a short trek. I was looking forward to seeing a new area of Greece, and to spending some days walking through virgin forests. The absence of technology and commerce was appealing too. I had my rucksack, my half-read copy of Empire of the Summer Moon, a sleeping bag, and a loaf of bread – the latter two in case I did miscalculate and ended up being locked out.

I left Athens at midday and arrived in Thessaloniki around sunset. It was a Saturday evening and Thessaloniki had a lively, friendly feel to it. I bought some gourmet trail mix on the promenade, then pushed on to Ouranoupolis, the jumping off point for Mt. Athos. The last two hours of the drive were along winding, misty roads through a forest, in the dark. I was listening to ‘Up and Vanished’, a podcast about a real life murder investigation in a provincial American backwater. All together, it made for a spooky drive, particularly when a large truck tailgated me for some distance.

I spent the night in a small hotel in Ouranoupolis. At 7.30 the following morning, I made my way to the Pilgrims’ Office to pick up my permit. The office only opened at 8, but I thought I would get there early to avoid any last minute mishaps (there was only one ferry to Mt. Athos and it left at 9.30). I was surprised that the office was already open when I arrived, and even more surprised to see a queue of at least fifty people waiting to receive their permits. They were wearing a lot of black leather. Many of them looked more like football hooligans than pilgrims. Almost all of them spoke Russian, though I was later to discover that they came from a number of Orthodox countries – Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Ukraine and Georgia as well as Russia. Being Orthodox, it is easier for them to get permits.

The queue moved faster than I had anticipated and I soon had my permit. I proceeded to the ticket office for the small ferry, and had to queue again, with the same crowd. After a tasteless breakfast by the quay, most of it spent swatting flies, I boarded the ferry. There were no longer any women to be seen, and a holiday atmosphere prevailed. As the ferry nosed towards Athos, some of the Russians pulled cans of beer from their pockets and cracked them open. Others threw pieces of bread into the air for the trailing seagulls to catch. My particularly thuggish looking neighbors kept turning in their seats and inadvertently (I think) elbowing me. I put my headphones on and returned to the murder investigation podcast. This was not quite as I had imagined.

The ferry stopped at each of the monasteries along the way to the tiny port of Dafni. I had planned to walk from Dafni, across the peninsula, to the monastery of Iviron on the east side. But when we docked, I saw that two buses were waiting to take people to Karyes, the administrative centre of Mt. Athos, and half way to Iviron. If I took the bus, I would be sure of arriving at Iviron before sunset. I climbed on board, and encountered one of the more characteristic aspects of life on Athos: male body odor. It would appear that, in the absence of women, men wash less, or smell more, or both. Boys’ schools are the same, as, I imagine, are armies.

The bus to Karyes took half an hour, on a dirt road, and from there I walked to Iviron monastery. The morning’s clouds cleared and I was granted some beautiful views of Mt. Athos itself, to the south. For over two hours, I only saw one other walker; the other pilgrims had vanished. This continued to be the case for the whole three days – once or twice I encountered an Athonite monk, but no other pilgrims. And this solitude contributed to a deep sense of peacefulness.

As I walked, I studied the piece of paper I had picked up in the permit office, detailing guidelines for visitors. These were quite strict – no shorts, no bathing etc. (not unrelated to the body odor, perhaps). The paper began by welcoming me to the ‘Garden of the Mother of God’… what a beautiful phrase! Garden, Mother, God… what’s not to like? But what does it really mean? How can God, the life-force that animates the universe, have a mother in any meaningful sense? Is it not the narrowest anthropocentrism? So beautiful, and yet, once again, I felt on the outside… the foreigner, the observer, wishing I could believe in something so lovely, but unable to deceive myself.

These ruminations were cut short by the appearance of Iviron itself, a medieval fortified keep beside the sea. I located the guestmaster, was shown to my room, and then attended the afternoon service. There was incense, and chanting, and monks in black habits with long beards. I admired the ritual, and the solemnity, and found it wholly unintelligible. There were other pilgrims too, all Orthodox, who appeared to know exactly what to do, and went in for an orgy of icon-kissing and crossing of their chests – so often, in fact, that it began to look like a nervous tick, rather than a sign of devotion. After the service, we were led across the courtyard to the refectory. Here there were two long tables with plates of roast fish in front of every place. We ate while listening to a reading from the Bible, in Alexandrian Greek.

Iviron

After dinner, we filed out into the courtyard, where it was still light. The half hour after meals was one of the few times when monks appeared to talk to each other. I wandered by myself between groups of Russian speaking pilgrims and pairs of Greek speaking monks. I went outside for a few minutes before the gates were closed for the night; there were Russians smoking outside. Then, as I crossed the courtyard again, I was astonished to hear two English accents, emanating from two bearded old monks. I approached them and introduced myself.

Both were indeed English, and both had converted to the Orthodox faith a long time ago. One had initially lived in a Coptic monastery in the Sinai desert, the other had been a doctor, then a psychiatrist, then a priest, then an Anglican monk, and now, finally, a monk on Athos. And they also wanted to know why I was there. I told them, as best I could.

Brother David saw through my meandering narrative. ‘If you are genuine in your search, then God will reveal himself to you,’ he said.

‘But there is so much that doesn’t make sense,’ I said. ‘Like the Garden of the Mother of God… it’s a beautiful idea, but how can God have a mother?’

‘Well,’ said Brother David, ’We believe that Christ was human, so he had a mother, but he was God too.’

Of course! How foolish of me not to think of that! I felt myself blush.

‘You may find that mysterious, and it is. But if you follow this path, then over the years, many mysteries will become clear to you.’

‘But I am not sure I can just believe something because someone, or some book, says so. That is what I like about Buddhism – it’s experiential, empirical, scientific. You practise a technique, and then you see whether it works, whether your experience matches that of others.’

Brother Irodio, the ex-Copt, had been less talkative so far, but now he said, ‘That is what the Orthodox religion is like. We train ourselves too, over a lifetime. And then, over time, God reveals himself to us.’

For a long time now, I have thought of myself as a pluralist. Most religions consider themselves to have a monopoly on the truth, and that has always struck me as highly dubious. From within the perspective of any given religion, the claims and the texts and the norms are perfectly coherent… everything hangs together and makes sense. But the same applies across the board, to all religions. So why are Christian arguments that rely for their evidence on the Bible any more compelling than Moslem arguments that rely on the Koran?

Brother Irodio and Brother David made no effort whatsoever to convert me. But Brother David in particular emanated a peacefulness, and a warmth, that made a deep impression on me. And this quality of peacefulness, this sense of Eine Heile Welt, grew deeper with every day that I spent on the Holy Mountain.

Of course, you might say that it is hardly surprising that these monks seem peaceful – there are no women to distract them, and they have no money to worry about, and nothing to buy or own. That is true. But I think that many people would find that very challenging. Many people actually like the drama, the games, the getting and having and then again spending or losing…. But I am not sure that I do, any more. And sometimes, maybe all that noise is a way of distracting oneself from what is going on inside.

The following morning I left early, while the monastery was still shrouded in mist. I continued south along the coast for about an hour, then struck inland to cross the peninsula from east to west. The dirt road snaked its way upwards to the central ridge. A couple of pick up trucks drove past me, and both times the monks stopped to ask if I was lost. One of the monks was American, and when I told him that I was heading to Osoriou Gregoriou, he told me the name of an English monk there.

The leaves were falling and I was reminded of a previous pilgrimage some years ago, to Santiago de Compostela, much of which was also during autumn. The temperature dropped as I got closer to the ridge. On a couple of occasions I passed monks chopping down trees. They used chainsaws, but enormous shire horses were waiting to drag the trunks out of the woods. When the horses snorted, conical clouds of condensation jetted from their nostrils.

I crossed the central ridge, with the peak of Athos to my left, then descended steeply down the other side towards the more sheltered west coast of the peninsula. I arrived at the monastery of Osoriou Gregoriou in the middle of the afternoon. While waiting for the guestmaster, I chatted to a rotund monk from Kalamata who had formerly been a pizza delivery boy. He was keen to reminisce about English football, and I fear I was rather a disappointment to him.

Osoriou Gregoriou

Osoriou Gregoriou is perched above the water. Mondays are days of fasting, and the evening meal was a bowl of lentils, but the meager fare was made up for by the sight and sound of the sea directly below us. After dinner I enquired after brother Damien, the English monk. I was led down a number of staircases to a bookbindery where Brother Damien was putting the finishing touches on a newly bound spine. He had a curly grey beard and a humorous manner. He was originally from Stockwell in South London, just down the road from where I used to live in Brixton.

We chatted that evening, and again after breakfast the following morning (which was in stark contrast to the evening meal – it was accompanied by wine, and finished off with a Ferrero Rocher chocolate). To say that Brother Damien was a conspiracy theorist would be an understatement, and I don’t particularly want to go into all that again, nor relive the sense of vertigo the conversation gave me (admittedly, we were also perched on a small wooden balcony above the sea). But I am grateful to Brother Damien for introducing me to the concept of ‘Theosis’. This is perhaps the central tenet of the Orthodox religion. It holds that the true purpose of human life is nothing less than for man to become one with God, to become a god himself.

When I said goodbye, Brother Damien gave me a slim volume written by Archmandrite Georgios, the former Abbot of the monastery. It was entitled ‘Vergöttlichung: Das Ziel eines Menschenlebens’. He only had this German copy, but I later found an English version. The English title is, ‘Theosis: The True Purpose of Human Life.’

I left Osoriou Gregoriou and headed north, back towards Dafni. After about an hour I passed through the beautiful gardens of Simonas Petras. The monastery itself towered above me, its walls inconceivably high, like CGI battlements from a Lord of the Rings movie. I passed back through Dafni and then climbed the final hour up to Xiropotamou monastery. Here the friendly young Romanian guestmaster (not a monk) plied me with tsipouro (Greek Schnapps) and Turkish Delight. Perhaps he felt he was atoning for the monastery, since it was rather an austere place: being non-Orthodox, I was not allowed to attend services or even eat at the same time as the monks.

Simonas Petras

That evening I read Archmandrite Georgios’ book on Theosis. He wrote:

Since man is “called to be a god” (i.e. was created to become a god), as long as he does not find himself on the path of Theosis he feels an emptiness within himself… he feels that something is not going right, so he is not joyful even when he is trying to cover the emptiness with other activities. He may numb himself, create a glamorous world, or cage and imprison himself within this world, yet at the same time he remains poor, small, limited. He may organise his life in such a way that he is almost never at peace, never alone with himself. Surrounded by noise, tension, television, radio, continuous information about this and that, he may seek to forget with drugs; not to think, not to worry, not to remember that he is on the wrong path and has strayed from his purpose.

In the end, wretched contemporary man finds no rest until he finds that “something else,” the highest thing; the thing which actually exists in his life which is truly beautiful and creative.

That gave me plenty to think about.

The following morning I again left before the sun had risen. There are terraces behind the monastery where many gnarled olive trees grow. I saw a monk with a great white beard and a staff; he was walking between the trees and inspecting the leaves. He seemed so entirely at peace with himself and the world, his world. A wave of emotion swept over me in that moment – there is such a thing as eine Heile Welt. And there are great mysteries too.

As I returned to Dafni to catch the ferry, I wondered about that wave of emotion: was it a tiny experience of what the faithful call ‘Grace’, something like a gift from God? And that bearded monk in the cool of the morning… for years I have assumed that men have anthropomorphized God, that we have created him in our image. But maybe I’m wrong? Maybe we really are created in the image of God? Not that God is male and bearded, nothing as simplistic as that, but maybe we do share some of God’s qualities? Maybe the divine is less abstract than I have always assumed? Maybe a personal relationship is not only possible, but necessary?

Since I was 11 years old, when I dropped out of confirmation class, I have not considered myself a Christian. A few years later, at boarding school, I encountered a couple of Reverends who could scarcely have been less inspiring: one a sad weasely figure, the other an ignorant bully and former army Padre who tried to show off about how many Argentinians he had killed during the Falklands War. Chapel was a daily bore, although the music and choir were good. Then, in my 20s, a couple of visits to Charismatic Christian churches, and a couple of sessions of the Alpha Course, but it was all so cheesy! So paper thin! Whereas on Mt. Athos, I felt there was something ancient, mystical, solemn, and deeply inspiring… qualities that I have rarely encountered in the West.

On days when I feel inexplicably tense, or somehow ill at ease, there is a phrase that comes to my mind from those dull chapel services of my adolescence: ‘The peace of God, which passeth all understanding…’ Could those be more than just pretty words? It is certainly worth investigating. I think I was wrong about the Native Americans, and that was a longstanding conviction too.

0 notes

Text

Asclepius the God

It is a long time since I last posted here. I have to find some flow again, so please forgive me if the following is a bit disjointed. It also starts with a physical ailment, which is uninspiring (and elderly), but it is merely a way in…

I have, for some time now, been suffering from lower back pain. It’s nothing dramatic, just a constant dull ache. But it is enough to kill my enthusiasm, in a very general way. Taking the dog for a walk, watering a plant… they become an effort rather than a pleasure.

There are different theories about the etiology of lower back pain. Some people say it is stress related (and, in my case, it came on at a time when I felt very tense). A friend of mine who is a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicine was more precise: it is specifically related to money trouble. The spine specialist in London was true to his scientific roots and diagnosed, with the help of an MRI, ‘mild joint effusions at L 4 – 5’. I asked him about the effects of stress. He said that stress and tension could make a problem worse, but that they could not be the cause of it.

I saw a chiropractor and an acupuncturist, neither of whom were able to effect any lasting improvement. In the end, the spine specialist prescribed painkillers, anti-inflammatories, and a course of physiotherapy. I followed this conscientiously over a period of months, also to no avail. Eventually, I went for an expensive cortisone and anaesthetic injection into the spine. The symptoms went away for a month, but as soon as those chemicals were no longer present in my back, the pain returned. I began to feel that I would just have to live with it; manageable, but joyless.

Here in Athens, a friend told me about about an ‘energy healer’ who had helped her a lot, and who was in any case an interesting individual. I thought to myself that I had nothing to lose, and I asked her for the healer’s contact details.

A week later, on a cold and drizzly February morning, I rang Iannis’ doorbell on a street in Pangrati - a comparatively quiet area of central Athens. Iannis came to let me in. He was a diminutive, smiling man in his late sixties or early seventies, with a lively, engaging manner.

We went into his apartment which was small, modern, and perfectly ordinary. On the walls were a few of those tricksy landscape paintings that are sold by street artists. I was about to launch into a description and history of my complaint, which so far I had not told him anything about, when he stopped me by holding up his hand. ‘Let me diagnose you,’ he said.

I then stood in silence, fully clothed, in front of Iannis, while he put his hands lightly on my shoulders for a few minutes. Eventually he said, ‘You have lower back pain, a problem around vertebra 04, and you have had trouble with your right knee in the past.’

I was blown away by this. He was right about the knee too, it was a rugby injury that had plagued me for about 2 years. While driving, the pain used to force me to stop the car every half hour to stretch my leg. But that was more than ten years ago, and since then I have not had any knee trouble.

‘Do you also sometimes feel that your heart beats irregularly?’ he asked. ‘No,’ I replied truthfully, and my belief in his omniscience diminished a little, though it is possible that he is right and I am not aware of it. He then said that my lungs were not breathing properly, owing to a problem some time ago. This is also true, I got pneumonia a few years back. He seemed to think that this was the more serious problem, since it affected the amount of oxygen in my brain and therefore also my general mood. But he thought that he would be able to treat all of these problems. When I asked how many sessions would be necessary, he blithely replied, ‘Just one.’

Iannis told me that he used a form of energy manipulation. ‘Like Reiki?’ I asked. ‘A bit like Reiki,’ he said, ‘but this is an ancient Greek technique, in the tradition of Asclepius, the God of medicine and healing. It is not written down anywhere. It has been passed down through generations of practitioners, but there are not many of us these days.’

Iannis told me to lie down on my back on his sofa with my eyes closed while he performed the energy manipulation above me. He told me to report anything I saw or felt, particularly any colours I saw. It lasted for about half an hour. Frankly, I did not see or feel a lot. Perhaps some warmth in my hands, and a slight vibration in my solar plexus. I saw a few greens and reds, but I could never be quite sure that I wasn’t imagining them, or willing them into being. But each time I reported a colour or a sensation, Iannis would respond with an encouraging, ‘Yes, very good.’

The treatment ended with the painful massaging of three pressure points, two on my left foot, and one near my heart. Then he asked me to stand up and walk around the apartment. I did feel a lot better, though the pain from my back had not gone completely.

I asked Iannis how he had performed the initial diagnosis. He said that it was by knowing himself very well, and then by sensing the energy of another person through various sense modalities, including sound and smell. He said that it was not so much a gift as the result of single-minded dedication over a lifetime. He reiterated that what is absolutely fundamental is self-knowledge; only on that basis can one come to know others. That is rather what I think about psychotherapy.

I paid 70 Euros and left his apartment. It was still raining outside, so I decided to wait it out and treat myself to a coffee. As I sat in the café, the ache in my lower back returned, as persistent as it had ever been.

*

Some months later, I felt I needed to escape the summer heat of Athens. I got on my motorbike for a weekend trip to visit some of the Mycenaean sites in the Peloponnese. The Mycenaean culture was dominant from about 1600 - 1100 BC; it consisted of a number of small independent kingdoms – Mycenae, Sparta, Argos, Pylos, Tiryns, Midea, Thebes, Athens and a few others. This was the period subsequently made famous by Homer in the Iliad and the Odyssey. It is the factual basis for the myths and legends that he committed to paper between 500 and 1000 years later, and also the period that saw the birth of the first attested form of written Greek (called ‘Linear B’), which predated the Greek alphabet by several centuries.

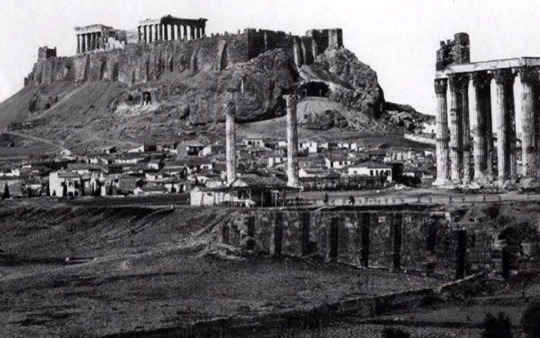

I crossed the Corinth canal and then followed the small country roads down to ancient Epidauros. This was once a sanctuary of Asclepius - a site of pilgimage and the most famous healing centre in the ancient world. It comprised the temple of Asclepius, a hospital, a 160 room guesthouse, a bathing complex, a 14,000 seat theatre with near-perfect acoustics, and a sports stadium used for quadrennial games.

The 14,000 seat theatre at Epidauros.

There were few other visitors that afternoon and it felt like a magical place. The pine trees appeared to pulsate with health. Beside the Temple of Asclepius are the remains of the rectangular Abaton; patients used to sleep in this building in expectation of a visitation, in their dreams, from Asclepius the healing God, commonly believed to take the form of a serpent. The God would advise them what they had to do to regain their health.

Beside the Abaton was the circular Tholos, the foundation walls of which formed a labyrinth that was used as a snake pit, full of harmless snakes. The pit may have served as a primitive form of shock therapy for the mentally ill. The afflicted would have crawled in darkness through the maze-like structure, guided by a crack of light towards the middle, where they would find themselves surrounded by writhing reptiles. One would need a very strong constitution not to find that shocking.

In the museum there was a sculpture of Asclepius holding a staff with a snake wrapped around it. This is the famous ‘Rod of Asclepius’ – the symbol of medicine and healing arts that is still used around the world today (it should not be confused with the caduceus, the staff of Hermes, which has two entwining snakes and is more properly associated with commerce). Asclepius is also often depicted with a dog by his side, and some healing temples used sacred dogs to lick the wounds of sick petitioners.

Asclepius and his snake-entwined rod.

Wandering around this peaceful temple complex, I wondered about the role of snakes in healing. It is a major theme in Amazonian shamanism. Snakes are probably the most common motif in Ayahuasca visions, and they play a significant role in the cosmologies and mythologies of many indigenous cultures. And indeed in our Western mythology too, going back to the serpent in the garden of Eden. Why are snakes so significant, and why are they associated with medicine and healing across cultures? I would like to know (there is an interesting theory in Jeremy Narby’s Cosmic Serpent, to do with the double helix of DNA, though it would seem to apply more accurately to two entwined snakes, rather than just one).

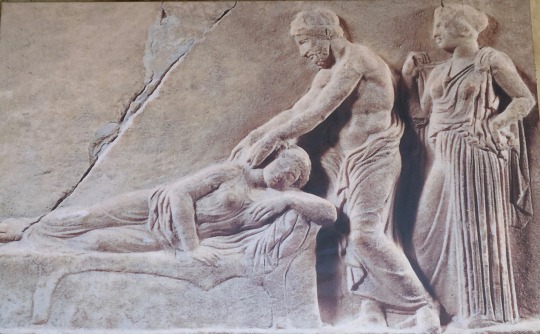

There was an area of shade at the back of the rectangular Abaton. Hanging on the wall was a photo of a relief sculpture from another Asclepian sanctuary (at Piraeus), depicting the kind of healing that may have gone on in this building. A patient was lying on a couch, and a healer, or perhaps Asclepius himself, seemed to be performing some kind of energy manipulation above him. It could have been me on Iannis’ couch.

Relief sculpture from the sanctuary of Asclepius at Piraeus

*

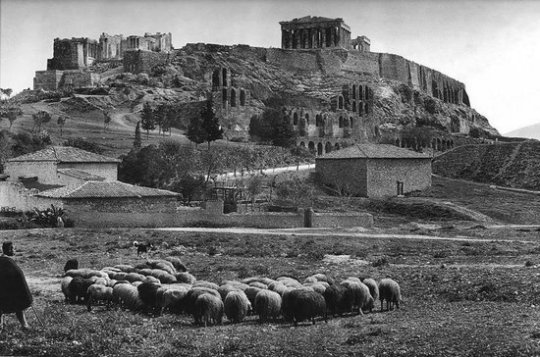

From Epidauros I drove to Nafplio. For 13 years, this small seaside town was the first capital of modern Greece, from the start of the Greek War of Independence in 1821 until 1834. At that time, as photos attest, Athens consisted of little more than ruins surrounded by a few farmhouses.

I spent the night in Nafplio, then visited the site of ancient Argos the following morning. It is on the outskirts of town, rather hard to find. Entry is free and the theatre is impressive, but less so than Epidauros. Then I pushed on to Sparta, down to Kalamata, and finally up into the foothills of Arcadia.

In the early evening I passed through modern Megalopolis; it is a nowhere sort of place – an empty main street, a series of traffic lights, and strong winds - but in ancient times there was a huge city here. From the road a few miles outside the modern town, I saw three Ionic columns standing unremarked in the tall grass of a tawny field, and behind them a flock of sheep and their shepherd. Who placed them there, and why? What were they once a part of? Which God was worshipped there?

I spent that night in the hillside village of Karitena. The night was blissfully cool after the sultry nights in Athens. The following morning I had to wait for the mist to clear, then I followed small, winding roads into the forested hills of Arcadia. I crossed the river Alpheus on an small stone bridge – Alpheus was probably the basis of Alph, the ‘sacred river’ that Coleridge glimpsed in his opium-inspired reverie, and whose ready-formed verses he subsequently committed to paper as the poem Kubla Khan.

I thought of the resonance of Arcadia, the traditional precinct of the nature god Pan. For later Roman poets, Arcadia was linked to the Golden Age - a time of innocence and primordial bliss, before the rot set in. Virgil claims Arcadia as his own in the climax to his Eclogues.

Arcadia came to be known as ‘Arkady’ in English, though Evelyn Waugh reverted to ‘Arcadia’ for the title of Book One of Brideshead Revisited: ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’. This is a memento mori in which Death is warning us that he will find us even in Paradise – the skull is forever grinning in at the banquet. But, one has to wonder, is that not what gives the meal its relish?

My GPS ceased to function on these tiny roads, and I was soon lost and had to retrace my route. But it was a beautiful drive and I felt profoundly grateful to live in Greece.

0 notes

Text

24 Deligianni Street, Athens.

24 Deligianni street is where I live. It is a πολυκατοικία – an apartment block. Literally, this means: ‘many (πολύ) – relating to (κατά) - the home (οίκος) , a ‘many-home-dwelling’. Oίκος is the archaic root that resurfaces in English words such as ‘economy’ (the management of the home), and ecology (the study of the home, in this case planet earth). It is a good example of how, in Greece and in Greek, the ancient and the modern, the old and the new, are interconnected.

My building is located in Exarcheia, beside the archaeological museum and midway between Exarcheia square, to the south, and Pedio Areos park, to the north. This was once a very desirable neighborhood, but in the 1960s and 70s many of the more affluent inhabitants moved out of the centre and into the suburbs. Immigrant communities were drawn to Exarcheia because of low rents and good transport links, and now it is very diverse, with many Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Nigerians, and, more recently, Afghans and Syrians.

The archaeological museum is next to the National Technical University of Athens, the Πολυτεχνείο, famous for the student uprising against the military junta in 1973, in which 23 students died. Exarcheia has been an area of politicised resistance ever since; the mantle has now been taken up by a broad group that define themselves as anarchists, though this appears – at least from the outside - to include anyone with any kind of grievance.

My building dates from 1930. It has an old cage lift built by Schindler lifts, a company founded in Lucerne, Switzerland, in 1874. This lift is not much newer, and some of its important looking cables are patched up with yellow insulating tape. To step into it is, firstly, to feel a little bit nervous, and, secondly, to step back in time.

My apartment is on the fifth floor. It has a terrace on which I have recently started to grow bougainvillea, jasmine, wisteria, solanum and fragrant rhyncospermum. My mornings now begin with a round of watering, and then the sweeping of leaves and petals that the night breeze has shaken to the ground. It is a fine way to begin a new day, and reminds me of life in a Zen monastery.

The terrace overlooks the the archaeological museum, which houses the gold mask that Schliemann unearthed at Mycenae in 1876. Caution was not Schliemann’s guiding principle; upon finding the mask, he telegraphed King George of Greece to say, ‘I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.’ Subseqent archaeological research has concluded that the mask predates the period of the legendary Trojan war by about 300 years. Nevertheless, when I sit on my sweet-scented terrace and feel the life-affirming tingle of inspiration, then I sometimes wonder whether I might be picking up the energetic emanations of an ancient warrior-poet, relayed to me across the ages through his gold death mask, just a stone’s throw away.

On other nights, the terrace is an excellent place to watch the clashes between anarchists, who throw Molotov cocktails, and the riot police, who mostly stand around smoking and looking bored. The clashes happen once or twice a month, and they have now acquired an oddly scripted quality, as if everyone involved is playing a role in which they no longer believe. The only exception are the journalists who pullulate behind the police. They are immediately obvious because of the luminous rectangles of their film cameras, and because they wear elephantine gas masks. Sometimes I feel as if I have box seats in an absurdist theatre.

My mother is coming to visit me next month. She will like the fact that I live beside the archaeological museum. When I was a teenager, she once told me that as a young girl she dreamt of becoming an archaeologist. But she never went to university, since from a young age she was a pawn in her parents’ acrimonious divorce, both of whom refused to pay for her education. She ended their ugly game by becoming a stewardess, thereby gaining her total independence at a comparatively young age. But it was a significant moment for me when she told me that she had wanted to become an archaeologist, because it was the first time that I had thought of her as a full person, with a life before I was born, and with dreams and ambitions of her own. I remember feeling a rush of tenderness for her then, as I do whenever I think back to that moment.

My landlady, Κυρία Φητίλης, lives on the floor below me. She is eighty years old and lives with what I initially thought was her mother, but I have since found out is the family’s former servant. This lady, whose name I do not know, is 99 years old. I don’t think I have ever met a 99 year old before. She is not surprisingly rather shrunken, with tremendous hairs sprouting from her upper lip and chin. She is very hard of hearing, and forgetful, so I have to shout to re-introduce myself every time I enter their apartment to pay my rent. However, she has a bat-like sensitivity for the sound of doorbells, and should her sonar pick up on the ringing of a bell, her tremulous cry of πιος είναι ? – who is it? – reverberates around the entire πολυκατοικία. But what I find most astonishing is the thought that she was already a young woman when the Nazis came goose-stepping through the centre of Athens.

Shortly after I moved in, I shared the lift with another tenant, this one in her sixties. Having confirmed that I was the new tenant on the 5ht floor, she then asked me if I was married.

‘No,’ I replied.

‘Ah, you must meet my daughter. She works in the university museum in Plaka.’

Then she noted down my phone number. A couple of days later I received a bashful message from her daughter, offering me a tour of her museum. I took her up on the offer and she gave me a very thorough tour of a rather uninspiring museum.

*

24 Deligianni is pressed up against its neighbours. The buildings must share some of the inner stairwells, since from my own kitchen I can clearly hear the family who live in the next door building, when they are in their kitchen. Most often I hear the mother, whose accent is deep and African, and whose vocal range is impressive. She likes to chat on the phone while cooking; at least, that is what I infer from her long monologues, punctuated by laughter, and accompanied by bubbling and splashing noises.

In my mind’s eye I can’t help picturing her with a tea towel around her head and a big white apron, like Mammy in ‘Gone With the Wind’. That does, I fear, make me a racist, albeit an unconscious one. In my defence, I did grow up with a much-loved cuddly toy golliwog, and I remember collecting the rather natty little ‘Golly’ badges that came with jars of Robinson’s jam. It is not just Κυρία Φητίλης’ centenarian servant who has seen changes in their lifetime.

My direct neighbours are a young graphic designer couple who live on the same floor as me. Their apartment is similar in size and shape, but while I have tried to preserve the style and spirit of old Athens, theirs is contemporary and cool and decorated with bright pieces of pop-art furniture. It seems we are all attracted to the unfamiliar, though that means different things for different people.

I was reminded of this when I met Zoe, a Greek girl who has set up a small artists’ cooperative in an old villa, not far from my apartment. She took me for coffee near the cooperative, in an elegant and minimalist new cafe that serves artesanal coffee. ‘Some Swiss contemporary artists came to visit recently,’ she confessed to me, ‘and I brought them here. They were horrified. So inauthentic! they kept saying. So gentrified! Well, I pretended to agree with them, but the truth is that all my life I have been longing for Athens to get a little bit gentrified, and now that it has – even if it’s just one small cafe – I’m delighted!’

For some people, Athens is a city with longed for pockets of gentrification. For others, it is ‘the new Berlin’. For me it is a time-warp to a slower, more peaceful, analogue past. Once again I am brought to the realisation that we all seek out what pleases us, and ignore the rest, and thereby create the reality which we experience, and which we mistakenly assume to be the same for everyone.

*

If I walk directly north from 24 Deligianni street, I soon come to the Pedio Areos park. Many homeless people live here. During the day they mostly sleep in the park, screened from view by bushes and trees. At night they congregate in front of what is now a boarded up building, but was once a tea salon. When I walk past this area in the early morning, on my way to swim in the Panelinios Atheltic Club pool, it is a depressing sight. Some addicts lie passed out on the steps of the building, while others scour the pavement for lost drugs. Small fires smolder, kept alive by pieces of broken furniture. Food remains litter the area and are fought over by dogs and pigeons. But by the time I return from swimming, the street cleaners have swept everything away.

A few weeks ago I stumbled back this way late at night, rather drunk. I loitered for a few moments and was soon approached by an Afghan dealer, from whom I bought a small quantity of refined opium. I was reminded of organic farm-to-table restaurants in San Francisco, though happily my Afghan dealer spared me a lecture on the precise location of the poppy field where the opium poppies had been harvested. A bearded hipster waiter in San Francisco would not have been so reticent.

I also bought what I thought was crack, but turned out to be crystal meth. Service was excellent and the meth dealer even threw in a new glass pipe, for free. Then I went home and smoked my purchases. The alcoholic fug exploded instantly and I felt great. I was way too wired to sleep, but not in a jittery way, since the opium made for a dreamy wakefulness. I stayed up all night and read a book from cover to cover.

I was still feeling pretty good the following day, but when the crash finally came, it was worse than I have ever experienced. I know that you only ever borrow energy - the loan will always be called back in eventually. But I was not anticipating that eviscerating intensity of inner emptiness. It lasted for four days, during which I scanned every new room for places that could support a noose. Having come through safely on the other side, I can confidently state that this experience marks the end of my intermittent 20 year relationship with recreational narcotics.