#hes an ocean man . not by choice but by the god his soul was sold to in a past life. thats how he looks at it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ok I'll just say it. When Robby's flipdeck said that he A.) Spent All of his money on Pizza and B.) Secured a Random Job as a deckhand on a shrimp boat to pay rent, that 100% felt like a manic episode. Like I dont know anything abt anything but also there is no doubt in my mind that that's what that was. I dont want to say that I think hes bipolar bc then when i call him Crazyass it's gonna look Rude but i think hes bipolar and I dont think hes diagnosed but he does have an old-timey sailor nickname and understanding of it all. That's what I think here on September 16 2020

#i call him Crazyass bc of the things he does and his general deameanor... not cos of the mental illness luv#but Truth be Told ... it's not like the mania helps with his crazyass demeanor . it certaintly adds to it#and the depression just makes it feel like the intro of moby dick like................bro#on one hand it's crass on the otherhand he relates a lot to the ocean bc of its troughs and crests .. he feels he is linked#like it's a force beyond him and hes Mad abt it. like Poseidon has his soul and has Damned him 2 the sea and theres Nothing he can do abt i#hes an ocean man . not by choice but by the god his soul was sold to in a past life. thats how he looks at it#and whenever he has an episode on either extreme he shorthands it as ''ocean madness'' but he honestly has a lot to say abt it#and he also just chooses to be a crazyass unrelated to all of that bc hes seen some sht and he can do what he wants..

1 note

·

View note

Text

4 POEMS by Jake Sheff

Elegy for Dog I: A Failed Acrostic

January was tired when it became king. Apples here love being red in the spring, Casting shadows against the stone architraves our Kapellmeister will never live down. You Stole Apollo’s cows, and let them graze to show me Heaven’s template. Where do failed heroes go? Eucalyptus cupolas and polar icecaps Frame the downtrodden gods. But you weren’t Freakishly wrong, as I so often am, on your

Joyride through nearly twice eight years, Á la someone far from beauty’s stepmom. Copper coin or grimacing sun? I’ve got 20,000 Kor of crushed grief on this threshing floor. Shark-sparks of sadness flood the impetiginous air… How, and why, do clouds cobblestone Entire days, and lakes, when you’re not here? Fixing every broken thing, poets go where Ferns and geraniums baptize the morning.

“Jur-any-oms,” is how you’d spell it; After all, a dog’s a dog, and wisdom knows futility. Cassations make a rusty brew, to drink the truth of truths, and Kill whatever ceases wanting to be new. Stewardship, the color of gravity’s silence, naturally Houses every “glur” (a glittery blur); go chase what plays Eternal games. I hear the swans by Rooster Rock. Your handsome Face, its happy handsomeness, in memory’s eye, goes in and out of Focus; in love’s better eye: your goodness neath its everblooming ficus.

Gravity and Grace on SW Murray Scholls Drive

“Impatience has ruined many excellent men who, rejecting the slow, sure way, court destruction by rising too quickly.” Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome

The traffic lights control the people’s actions, but Not their feelings, as the limits of philosophy Collide head on with the nose of a Dalmatian.

I tell you, the day is stress-testing itself, and these Sidewalks wish that it’d just gone straight. Geese Take this sky-hairing wind for granted, as they

Land on the lake like memorable speech on The sensitive soul. Time is never sharp, but it’s Cutting something in the credit union. Maybe

It’s dancing a back Corte for the woman in line Thinking about the taste of limes from Temecula As she waits for the teller. Air Alaska and that

Haunted pie in the sky are not the only reasons For all the volatility in the air today. Rushing And perfectionism both produce a loss; behind

The Safeway Pharmacy, you’ll see the small Smells of both, sloshing around to the ticking- Sound of the ocean’s tides. I must admit, I am

Frozen in place by the sight of steam from Joe’s Burgers; it is poetry’s pale tongue, rising in And arousing the air. This neighborhood’s street-

Lights are more serious than kokeshi dolls. Lights From its windows outshine poison dart frogs. Maybe to forget about life for awhile, the lamps

Are focused on The Population Bomb? ‘Easy Tiger,’ all these incidents whisper. Each day’s A sign twirler’s dais; each corner a promise

Of something more in a different direction: it isn’t A marriageable daughter or impoverishment, But inguinal ingenuity plays a part, and that isn’t

Bad at all. What oaths and paths went here Before Walmart? What voices were voided by The liquor store? What are vague’s values

When the library shares a parking lot with a 24- Hour gym and a cargo cult? Gas stations satirize The Queen of Hearts; I tell you, it makes every

Question seem incidental. Treaty-breakers in Pajamas swing on the swing sets. Was August That full of angst? It feels like autumn went too

Far on accident. Desertification, in a sugar tong Splint, takes a shot of ouzo and talks shit About the death of Brutus, but my Bible-thumping

Memory – on a ski hill in Duluth – is also too busy Watching some ducks on the lake to notice; and Desertification makes a face at me like a Swedish

Film. Poets make for poorly picked men to Familiarity’s paymaster-general. The Calvinistic Rain is an ill-starred attempt to make mayonnaise-

Fries just for me, but I must admit, it all seems – You know – cybernetic. And step-motherly as all Get out, if you ask the trees. They prefer “You

Can’t Hurry Love,” by The Supremes, to any Changes that take effect in one to two pay periods. Pretext ricochets; a perfect reverse promenade.

At Summer Lake, When the Vegetables are Sleeping

Cruelty drinks all the wine, and never gets drunk On these shores. When Summer Lake speaks, In every word, an introduction to the world. I am

Easily duped. The greatest duper duplicates my pride, Which always lingers, in the hallways of my heart And beneath the surface of Summer Lake. The sky is

Supplicating, it’s literally shaking. An hour passes Faster here, the hour always held too dearly dear In paranoid and ivied walls. The ducks can do

An unwise thing correctly, and it sounds more like Dusty than Buffalo Springfield to the enokitake Sold in Springfield, Illinois, which is the opposite

Effect it has on the wild mushrooms on these shores. On cables capable of love, the geese convince The weather to taste like kvass today. Basically,

Another Cuban Missile Crisis drowned itself just Now. The clouds might ask themselves, ‘Is lowliness Allowed here?’ To which the crows might ask,

‘Does omertà sound like lightning?’ The answer’s Oubliette is ten times worse than impotence. Summer Lake isn’t smart, but it stays quiet, like

Someone too smart to say all they know. ‘Whoa, Sweet potato,’ the capital gains tax mutters To itself, knowing that what matters doesn’t mean

A thing. Some say the lake bottom’s sands receive Commands from Hearst Castle, others say Its hands are King City’s hands, and still others

Maintain more sins have been than grains of sand Times secondary gains, and that explains The beauty and industry that none can see but

All can feel on these shores. (Some possibilities Play possum, or get opsonized by hate; this one snores Like Rip Van Winkle.) This orb-weaver spider is

The Milton Friedman of Summer Lake, the wind On her web is Grenache from The Rocks District Of Milton-Freewater AVA for the eyes. The day is

Stereotypical, although it feels like three days In one…But for the lake’s good counterfactual Questions, I would forget that some die young,

But most die wrong. I’ve tried to pick up Summer Lake’s reflections in three lines or less, but The hardest truth is your own impotence. Oh,

It’s hard to hand your power over to a thing No one can see. Hopped up on distinctions – not The obvious distinctions – Summer Lake is pretty;

Cold, but pretty! In the distance, with so many Intercessory prayers, hot air balloons are rising; Shaped like teardrops, upside down and rising.

This lake re-something-or-anothered me. Are first Impressions wrong sometimes? I am a season’s Golden calf, according to the sunlight, doing

A prospector’s jig on the surface of Summer Lake. If not for the Weimar Republic’s wooden- Headedness, I’d set down my heart-song and

Listen to reason on these shores. I never trust An activist guitar, if the weather is socially clumsy. The future is reflected on the lake: it always

Laughs at us – between its math and gratitude Lessons – and never thinks of (or gives thanks to) Us enough. The presence in the lake juniors

My ears. The day is not too baffling, nor is it Jane Eyre. Space-themed and spiritual, some autumn Leaves are swimming in the rain. The ducks arrest

My attention in the mardy weather, even though they Must know my attention is dying. The barbed wire Around my stated goal is an outcome out of

Their control. Picnickers picnic with acorns and apricots, On blankets covering Holy Schnikey’s death mask. My unsandaled thoughts thrive and increase on these,

And no other shores. They are pets for the days less Important than love, when Summer Lake says it’s Humble, because it knows the right thing to say.

Summer Lake gives the comfort of commonly held And seriously absurd beliefs to the blue heron. Nothing is wrong with this lake or anything in it,

Not even the ghost of Amerigo Vespucci. It’s all so Simple to the stiff-necked molecules of water, made out Of frogs and snails and puppy-dog’s tails. These thoughts

Are fine manna in a fine ditch. Post-structuralist squirrels Can tell my heart’s in Italy, and I’m in the intellectual Laity. Chivalry’s technician sees my shovel, and they say,

‘You’ve got to hand it to him.’ Neurocysticercosis Sets the bar high; it looks at this park, and thinks The smartest monkey drew the perfect landscape.

That’s this maple tree’s previous disease, its precious One. It unfurls the ferns of my firm and foremost Beliefs, I’m told, to partialize insufferable vastidity.

We Install a Sump Pump on (What Used To Be) a Holiday (Take 2)

The oppressive heat was born a fully grown Man. I admire the result of its effort, but Despise the means of achieving it. My wife Asserts her individuality in the gunk; her Body’s allegations aren’t too soft or hard today. Her self-interest seems to have drowned in the vortex.

Our little garden knows flippancy with regards To privacy is unwise. The stepping stones can Only blather, as slugs draw nomograms on Their faces. My wife’s body speaks Proto-Indo- European in the vortex and denim overalls. Marc Chagall’s The Poet studies her. He calls her

‘Innocence: The opposite of life! A criminal with A badge!’ I hand her the tools of a crude and Rudimentary faith, and she says, ‘Jill, great books Make fine shackles.’ Her arms only have An administrative objective in the vortex, but They are where good things come from.

Jake Sheff is a pediatrician in Oregon and veteran of the US Air Force. He's married with a daughter and whole lot of pets. Poems of Jake’s are in Radius, The Ekphrastic Review, Crab Orchard Review, The Cossack Review and elsewhere. He won 1st place in the 2017 SFPA speculative poetry contest and a Laureate's Choice prize in the 2019 Maria W. Faust Sonnet Contest. Past poems and short stories have been nominated for the Best of the Net Anthology and the Pushcart Prize. His chapbook is “Looting Versailles” (Alabaster Leaves Publishing).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Achilles Was More Than A Weapon

by @toomanystacksofbooks

Achilles, in my own understanding of his tale, has been horribly misrepresented by history. Born of heaven and earth, he was told to live a certain way- to be a certain way. He is, today, viewed as a warrior of the greatest kind, which he was, of course, but I’ve noticed a great number of people who seem to believe that his entire character is diluted by that fact- to war and blood and violence. To do such, one erases every other part of him, everything else- good and bad and gray.

First, we must understand his origins. His mother was Thetis, an ocean nymph, a goddess. She had fallen victim to the will of higher gods, forced into an unwilling marriage with Peleus, who was a king. And so Achilles came, breathed his first years on Phthia, a prince. He was greatly admired from a young age and known to be light on his feet, swift, and graceful.

Here we have our first example of something that was key to his character that was not his status as a warrior. Yes, his speed and grace and precision were all what made him a great warrior, but that is not why he had such talents. He was, first and foremost, a child. Before he ever was a fighter, a soldier, a killer- he was a kid who wanted to play.

We know that Thetis was not so fond of Peleus- at least in many interpretations- but she loved her son dearly, and wished for him to be divine some day. She visited him, and told him as much, and he listened and walked away when their meetings were over. She knew that heroes such as her Achilles would be fated to, one day, make a choice. A short, glorious life- gone down in history, adored- or a long, forgetful life- a man who would be forgotten, lost in the winds of time. Achilles, I think, never wanted more than to have fun when Thetis began thinking about this. He was a child, and what child would choose a war and grief and death, simply to be remembered and revered, over a full and happy life, all for oneself? I believe that he was taught, pressured, into thinking that he desired honor. At some point, he must have lost much of his childhood confidence, and began craving other people’s approval.

I can understand, honestly, what was going through Achilles’ mind as he made such decisions. There comes a point where you’ve covered up so many layers of yourself that you simply cannot remember who you are. Not truly. It is because of this that I sympathise with Achilles. I think his tale would have ended very differently had the social and peer pressure been lifted, had his mother understood what a child needs.

And a child needs nurturing. His nature was not to fight.

Another example of his skills and character outside of war is the lyre. He was known to have played it, to have marveled at the sounds it could make. It was a hobby, but he was Achilles so he mastered it quickly. Perhaps had he not been taken to war, he would’ve picked up his lyre and written and sung the tale of those who did. Perhaps Troy would not have fallen.

He was also, supposedly, honest. He was empathetic and caring, especially to those he was close to. He did not want to fight, I don’t think, but he knew- or thought- he was supposed to. He enjoyed the fighting, but not for the pain and hurt and blood, but for the rush of adrenaline, for the way he could run and dance, the way he could throw a spear. He never once stated that he enjoyed the killing.

Patroclus, lastly. Patroclus was his mortality, that half of his soul. I do not believe in soulmates, generally, but somehow Achilles and Patroclus have me sold. Patroclus was compassionate where Achilles was emotionally confused and distant, Patroclus was a healer where Achilles was a fighter, Patroclus was a little clumsy where Achilles was sure-footed. Patroclus was mortal where Achilles was divine. It was he who kept Achilles sane, who kept his mind from spiraling to true selfishness and cruelty. Patroclus gave Achilles a reason.

When he died, Achilles snapped. In The Iliad, it is said that Achilles sobbed so loudly that the gods at the bottom of the sea could hear it. He first wanted to kill himself, but he had no weapons. He wept by Patroclus’ body for days, and when the best of the Greeks, the greatest warrior who ever lived, died, they had their ashes mingled together (The Iliad, Homer: “There is nothing alive more agonized than man / of all that breathe and crawl across the earth,”).

Achilles killed, yes. He raided and fought and ran through a war he would not see won. But so did Hector. So did Patroclus. So did Odysseus, and Agamemnon, and Paris, and the Amazons. They were all fighting, because a woman was taken, or went, because she had no choice as to what was to happen to her. Achilles should never have had to fight. None of them should have. There is no “right side to this war” because both the Greeks and the Trojans did terrible things. And both of them paid the price.

“We men are wretched things,” is stated by Homer in The Iliad. And so that includes us all- men like Achilles, Patroclus, and Hector. Women like Briseis, Helen, and Hecabe. We humans are so diverse, yet we are so similar. Is it not wrong of everyone to go to war? Or just one side, the attacker? The defender? Or those which are both?

In The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller, Odysseus says to Patroclus: “He is a weapon, a killer. Do not forget it. You can use a spear as a walking stick, but that will not change its nature.”

But he is not a weapon. There is so much more to the tale of Achilles than the Trojan War, than when he fought a river god and killed Hector of Troy and was killed by Paris. He was a child, free and bright as the day. He ran on the beaches of Phthia, trained with Chiron on Pelion. He was Achilles, a golden boy with a golden lyre under a golden sun. He did not exist to assist Meneleus in his nonsense, he did not exist to sail a thousand ships. He did not exist to fight, for we know he could have changed the Fates when his grief was as great. He was shaped by all of this. He was sharpened by all that he experienced, by those who he met. Patroclus and Briseis and Odysseus and Diomedes and Agamemnon and, eventually, Thanatos, who led him down to Hades to rest.

A spear is a stick before it is a weapon. Achilles is no different.

#no achilles slander on this blog#this is obviously just my interpretation and my opinion#and it’s important to understand that these myths are just stories and they have been changed and interpreted differently over the years#and any interpretation is valid#but please don’t bring any achilles hate onto my blog i love him so much#the trojan war at least in my eyes was very morally grey on all sides#and it is probable/possible that it was not a mortal affair#in that a feud between athena aphrodite and hera may have started it#opinion#achilles#the trojan war#greek mythology

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

“i believe i should like to stay.” from Sephie

Bridgerton starters . not accepting

With time, Melissa had learned that much of what she thought to be true about Sephiroth was, in fact, incomplete at best. The idea that Shinra sold to the population, of an almost god-like war hero was not incorrect per se – his military feats had been amply documented, after all – but it was not everything that there was to him.

He was, first and foremost, a man – and a young one, who lacked experiences that anyone else of his age likely had gone through. He was a dedicated student and a faster learner, and for everything they did and for each moment she had spent with the 1st, he had rewarded her in some fashion.

Trips topside were her favorites – without the proper ID to leave the slums, Melissa only left the Wall Market when someone summoned her. But with Sephiroth, that meant that, most of the time, access to plateside was granted, no questions asked. And for every opportunity to gaze at the night sky or to eat at a different restaurant, she was always grateful for the kindness that apparently was never-ending on his side, even if it was hardly publicized.

They were also discreet – for a Wall Market self-styled queen and for someone popular enough to be Shinra’s posterboy, they tried to keep a low profile while doing all these mundane things around. And that evening, he had taken her to a different sort of outing – an aquarium. Melissa had never seen the sea, much less any of the creatures that lived in the ocean but for the ones that she was supplied with for the inn’s menu.

So visiting one of Shinra’s public aquariums had been one of her loveliest experiences – the brothel madame realized that she probably had acted (and reacted) like a child sometimes, filled with the excited glee of seeing a dolphin swimming just that close – but Sephiroth only smiled at her and never once hurried her along. Ever the perfect companion, the SOLDIER made sure to also return her home safely – after all, their first encounter many months ago arising exactly from an unsavory experience he had rescued Melissa from.

There was hardly a soul around by the time they return – the inn was a different sight without the excited chatter of the patrons and her girls, with lights turned off and whatever guests remained locked in their private rooms with their choice of companionship for the evening. Melissa sighed contently when they approached the stairs to the second floor and where her quarters were, letting go of his hands to stand on the tip of her toes to plant the softest of the kisses to his face as a goodnight gesture.

It was then that Sephiroth’s words surprised her – ‘I believe I should like to stay’. Melissa had invited him to stay the night, time and time again – but she had never expected him to accept. They were taking things slowly – and she had no idea of the commitments or the schedule the 1st needed to observe for work.

Well, that night was truly turning out to be full of surprises.

“Then please do - nothing would make me happier.”

#Sephiroth#seraphicwept#Bridgerton starters#replied#after 32359 years#I finally got this one out#and I realized I missed the cute ;;

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shameless Part 2: Secrets

prologue Part 1

Word Count: 2,200

Warnings: Kissing, fluff

A/n: i really know nothing about mobs lmao

You woke up, your eyes fluttering open. The sun leaking from the open spots of the blinds soaking your skin. You slowly sat up to see tom in front of the mirror buttoning up his shirt giving you a glimpse of his sun-kissed abs. You watched as he buttoned the shirt slowly, and all you wanted to do is go over there and unbutton it. You made eye contact with him in the mirror blushing, and looking down at the white sheets. As angry as you were in the situation you were in you couldn’t deny that your new man was gorgeous. His toned chest, strong arms, and kissable thin lips. You had also heard stories from others that he was a god in bed, and well you didn’t doubt it.

“You're up” he noted turning to face you as he buttoned the last button on his shirt. “Did you sleep well”?

“Yeah” you mumbled rubbing your eyes and then brushing your hands through your hair.

“So, I know this is out of the blue, but there is this ball or dance that's tonight. Its a fundraiser, and we need to be seen in public, so everyone believes this is true” he rambled playing with his hands.

“I think I'll have to pass” you sighed. Not wanting anything to do with the mob bullshit.

You never wanted to be part of this, but unfortunately, it was looking like you werent going to have a choice in the matter.

“Yeah that's not, really an option” he replied walking closer to you. “We're leaving at 6 pm, there is a dress in the closet for you, I am not asking you to come, I’m telling you your coming, so you better be ready to leave the house by 6 pm” he purred touching you bare shoulder dragging his hand down your arm softly giving you goosebumps.

“You don’t control me, Tom,” You whispered standing up. You were so close to his body you could feel the heat radiating from his body. You put your hand on his chest dragging it down. Silently wishing there was no shirt blocking his chest. “But since your dad scares the living shit out of me, and I don’t want to die or get physically tortured I will come with you. You felt his body tense up at the touch of the hands making you blush, and quickly remove your hand. You walked away towards the bathroom closing the door. You leaned against it sliding down the down into a ball putting your head into your hands. Your head pounded as you thought of what your life was about to become. After the mobs know you and Tom are really together you'll have a target on your head. You slowly stood up turning on the shower. You removed your clothes stepping into the glass door. You stepped under the hot water steam rising from your body. You grabbed the soap rubbing it all over you closing your eyes taking a deep breath. This was going to be a long day.

--

It was around 5:00 when you started getting ready. You weren’t sure how you felt about the whole outfit he picked out for you though. It was a black dress that fit all your curves. You felt sexy in it, but sexy, well wasn’t your thing. You would have some bursts of confidence, but you tended to not have self-confidence when it came to being alluring or seductive. You get too nervous and you come off more like a clumsy awkward girl. You curled your hair. Applied some light makeup including mascara, eye shadow, and foundation. You added lip gloss to your lips because you hated lipstick. Every color you ever put on made you look like a clown. As you were applying the lipstick Tom appeared in the doorway putting one arm up on the frame leaning against it. You could have sworn you saw him checking you out as you glanced at him through the mirror. Your face went bright red.

“I’m glad I picked that dress you look ravishing” he purred walking towards you. Somehow you got even redder. The heat coming from your face was making you dizzy. You were 19 and he was 23. He was older, more mature, and for some reason that made him ten times hotter. It not that you haven't had a boyfriend before. You were a virgin though. You had done little to nothing thing sexual, because your parents were crazy, and had you basically locked in your house because they didn’t want you to die probably because they needed you to be a pawn for their game. You hated that.

“Thanks” you breathed as he came up behind you. You turned, and your chests bumped, and you took a step back looking down at your feet.

“Turn around, I have the perfect necklace for you to wear tonight, and I have your ring, you'll need to wear this tonight,” he said lifting your hand to slide the ring onto your finger. He put his hand on your waist lightly spinning you around so your back was to him. He held a diamond necklace in his hands. He put the necklace on clipping it in the back.

“Perfect” he mumbled, stepping back from you. He gestured for you to follow him. You grabbed your purse and placed your phone into the bag. You walked out of the bedroom trailing a bit behind Tom. You werent the best at walking in heels. That you could admit. You looked down at the ring on your finger. It was beautiful. That you couldn’t deny, but you were upset.You were tourn because you would never get a marriage proposal, never have a real wedding, and never get to experience falling in love. That was all taken from you, and it made you sick. You were stuck in your thoughts your body in autopilot when you bumped right into Tom.

“Sorry’ you sighed. Picking up your purse you dropped. You were at the front door walking towards the limo. Tom opened up the car door for you. You gave him a soft smile muttering a thank you as you entered the limo. You moved yourself to the window seat buckling yourself in. Tom was seated right next to you, and next to him was Harrison. The car rolled away from the castle making this the first time you left your prison or your home since your father dropped you off that dreadful day. As you watched buildings roll past you thought about escaping. Running away and never looking back. Starting fresh with a new name sounded like the best idea in the world, but you would never be able to live with the guilt because if you left your parents blood would surely be on your hands. You were so caught up in your dream world in your head that you didn’t realize the limo had stopped. Tom tapped your shoulder snapping you out of your daze. You opened the door of the limo stepping out feeling the fresh air on your skin. You looked up at the building. It looked like a 5-star hotel. It was gorgeous with a lit fountain liting up the garden below it. You began to walk towards the door Tom right next to you. Your hand brushed his and you blushed but tried to act casual. Harrison opened the 2 doors to the entrance, and that when Tom interlaced your fingers. At first, you pulled away but he whispered in your ear.

“Were supposed to be married just go with it” You nodded your head. Interlocking your fingers again. His hands where clammy. He seemed a bit nervous. So were you though. Anxiety was coursing through your veins. He leads you through the halls to a large ballroom. It was so crazy that although this was the mob in the public eye they were saints doing fundraisers like this. He took you to a circle table releasing your hand to pull out a chair for you. You sat down pulling your dress down over your thighs feeling overly exposed. One of your legs were bouncing up and down. Your hands shaking slightly. You were terrified that they wouldn’t believe the marriage, and that would result in the death of people on your side of the mob. Which would include your parents? The Hollands were extremely powerful and threating with death was their specialty. You had figured out in the past day that the reason your father sold you off was to save your family's life. It was either this or the Hollands would obliterate the Y/L/N mob. Tom noticed your anxiety and put his hand over yours squeezing it. He leaned over asking you a question.

“Do you want to dance” You swallowed, nodding slightly. You hoped you could make this looked convincing. You grabbed his hand and he leads you to the dance floor. He placed his hands on your back, and you lifted your hands to his neck. You both swayed to the music.

“Are you okay?” he asked He sound genuinely concerned.

“Not really, I don’t want this Tom,” you said backing away from him releasing your hands from his neck. “All of this, always being a target, having to worry about my every move, being trapped in your castle”.

“I know” he sighed grabbing your hands putting them back around his neck. “I didn’t want to be forced into marriage either, but this is what had to be done so I can take over. We have no choice in this matter. We can't risk seeing other people, because we could ruin this all, so let's just make the most of it, I’d love to get to know you”. Your mind was racing with thoughts. Part of you wanted to slap him, and the other wanted to spill your whole life to him. You nodded looking down at your feet. It was a long silence before Tom spoke up. It was honestly a pretty awkward moment. Like when you are talking to your middle school crush and you have no idea what to say.

“So what's your favorite color,” he asked out of the blue. You looked up from the ground giving a small laugh.

“Maroon, I like red, but I’m more of a fan of darker colors they look better on me, what about you” you responded

“Blue, like the color of the clear blue oceans, those are gorgeous” he answered, making you laugh. “What” he questioned looking at you like you were a little crazy.

“Idk I was just expecting your favorite color to be red like the color of blood, or black like the color of your soul”

“What do you think I am some emo middle schooler who listens to screamo, I’m a future mob boss, not a psychopath” he laughed.

“Eh, I guess I was expecting something less innocent” you trailed off. “Favorite animal”?

“Dogs, 100%, I don't think I could ever love anyone more than I love my dog”

“So you’ve got a soft spot for dogs. Noted” you giggled. “Mine is the Tiger they are fierce, majestic, and beautiful like me of course,” You said as you flipped your hair dramatically making him laugh.

“Does that mean you're a cat person, because then we probably have to get divorced because I don’t do cats” he joked making you laugh.

“I prefer dogs over cats so I guess our marriage still stands” you smiled tucking a piece of hair behind your ear.

“And also you are beautiful like a tiger” he interjected

“Thanks” You replied as your cheeks turned bright red. Heat radiating from yur skin like you were sunburnt.

You and Tom talked for a couple more songs, you even danced for a bit. He spun you around, and you attempted to do the tango, but the almost lead to you falling to the ground and left both of you in hysterics. You were actually having fun with him which was the opposite of what you were expecting. So you could conclude with you and your husband actually had some things in common. You both were dancing in the middle of the dance floor when he pulled you closer to him. Your body tensed up as your foreheads touched.

“Just go with it” he whispered, and then he placed his lips on yours. Your eyes were wide open and you froze. His lips were soft and warm. After a couple of seconds, your body relaxed into the kiss and you're melted into his arms. You slowly moved your lips against his pulling him closer to you. You tugged on the ends of his hair causing him to groan. You pulled away from the kiss to breath resting your head on his shoulder. He used his hand to lift your head up, and he whispered into your ear.

“How about we leave this, say you're sick and go have some real fun, I know the best clubs around town. And an ice cream place with the best ice cream you'll ever eat.

“Lead the way Holland”

#tom holland#tom holland imagine#tom holland xreader#tom holland x reader#tom holland edit#tom holland drabble#tom holland smut#tom holland x you#mob!tom#peter parker#peter parker smut#peter parker x reader#peter parker imagine#peter parker angst#spiderman#spiderman smut#spiderman edit

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Reed X OC Ch.01 /?

Hey this is my first fanfiction, So only nice comment Please

Sybil Rutter came with her sister to Jamestown to marry a man she's never met. Will it be love at first sight or a cruel twist of fate??

Prologue

Sibyl

July 1620

Sibyl’s stomach Rolled again as more waves crashed into the ship, her head leaning over the side of the ship. Hoping the cool spray of the ocean would help soothe her sickness a little. Beside her Alice, a girl her sister Verity had befriended whilst aboard the ship, patting her back. “It’s okay, it will pass soon,” reassured Alice as Sibyl stood up and Straighten her dress. Her legs struggling with what little weight her body held. At the start of the voyage, she’d been fine, but the further out to sea, they drifted the rougher became the sea had become and harder for her to keep anything in her stomach. “Aye pass, then return at supper with a vengeance,” replied Sibyl. Alice met her pessimism with a gentle smile before shifting her attention back to the sea. Alice was one of the few girls aboard the ship who has kept her optimistic views on their current Predicament of being taken to a new land to marry the men that travelled over here 12 years before build the colony. Maids to make wives as people called them, Women the men had paid to be brought over to said colony for them to wed. Her and Verity would be one of the first groups of girls to do this. Verity had joked, often joked that she felt more akin to a cow being sold than a woman being wooed by a suitor. Although she’d say this with her usual boldness, Sibyl knew her sister and to Verity, marriage was no better than being shackled and locked away. Sibyl still herself was unsure of where she stood; It excited her to be traveling to the illustrious Virginia Colonies, Jamestown and see the new World. But another part of her a larger part of her feared this obscure place.

This place was to be her home, a home she’d share with a man, a stranger she’d soon call husband. A man who she knew nothing about. Not his age or profession, not even a name. Will he be kind to her and allow her time to adjust to this new role to him? Or will he be cold and cruel man behind closed doors demanding she fulfils her wifely duties as soon as they’re wed regardless of whether she wanted too? These questions swirled around her head seeming to multiply, causing her sickness to rear its head again. A hand being placed on her shoulder pulled her attention from these thoughts and signalled someone new joined them. It was Verity. “Let me guess, you’re both dreaming of your princes and their pot bellies?” She teased as she turned to lean against the ship. Sibyl sneered at her jab whilst Alice sighed and turned to Verity. “Aren’t you glad Verity? Aren’t you grateful we’re the ones to come to this new world?” Sibyl looked to Verity as her hand drifted to Sibyl’s opposite shoulder bringing her in close. “Hell’s teeth no” Grinned Verity before she let out a laugh one that neither Sibyl nor Alice could resist joining. Alice opened her mouth to counter when a ringing bell from above caught their attention. “Land!, Land!” Sibyl felt Verity’s arm tighten around her shoulder as a rush of girls hurried over to glimpse their new home on the horizon. There it was Virginia it looked like a dark grey smudge marking the end of the ocean and the beginning of the sky. As she gazed out at the distant land, she felt a cold tingled run down her spine, this was no turning back now.

Although they had reached port before the sun completely set, they’d have to wait until morning disembarking due to an unforeseen problem much to the other girl’s dismay. Sibyl was grateful for this. Since they had seen land all the other girls had disappeared below deck to pack up their belongings and themselves presentable for the morning leaving the top deck empty except her. Verity and Alice disappear below deck not long ago. Alice went to help the other girls whilst she suspected Verity had gone to make sure no one ‘accidentally’ packed their belongings in their bags. There were so many stars in this new world and quiet so quiet she could hear her own heartbeat in her chest. It seemed to echo in her ears. Back in London, Sybil was lucky to hear her own voice sometimes the crowd was so loud. This place would be different, she thought. No more working endlessly in her uncle’s shop to pay off her ‘debt’. Maybe her sister could find some peace here and settle a little but knowing her sister she’d be able to find mischief standing still.

Sibyl's mind drifted to her sister, Verity hadn’t been shy about her resentment towards the situation, but It was Jamestown or jail and for Verity, there was only one choice. When they were younger, Verity used to tell that even though they were the 2 sides of the same coin. Different but the same she’d say. It was true her and Verity looked more akin to cousins that siblings. A smile formed on her face; It was true although Sibyl’s dark auburn locks were curled it was no where near as wild as Verity’s fiery locks. It was the same with their eye to where Verity’s a bright blue, Sibyl’s bore a dark honey colour. A cough from behind her startled Sibyl out of the memory. She jumped to her feet pulling the shawl tighter around herself as if it was a shield and turned, stood at the top of the stairs, was a woman holding a lantern. From what patience could see the woman older, dressed in a fine dark dress. It was the Governor’s wife, Mrs Yeardley. She was nice enough a little too god-fearing for Sibyl’s taste but nice all the same. Sibyl quickly bowed her head and addressed her “Ma’am”, Mrs Yeardley looked at her with an unreadable expression. “I thought everyone had retired. Why are you still awake, child?” questioned Mrs Yeardley as she descended the steps Sibyl was just sitting. “I couldn’t sleep, and I didn’t want to disturb the other, so I came up here,” which was the vague truth sibyl thought. She hadn’t been able to sleep, not with all the excitable chat of the other girls and had quietly snuck away. Mrs Yeardley stared at Sibyl moment before smiling, accepting Sibyl’s answer.

“It is understandable, but it is late and it would be best for you to return to the sleeping quarters. You’ll want to be at your best when you meet your intended.” There was something in the older tone that hinted to Sibyl that this wasn’t the light-hearted suggestion it seemed. Mrs Yeardley placed a hand on Sibyl’s arm. “To Bed with you dear, The Lord has seen fit to bless you with a prosperous new home and husband. Don't repay his kindness with Impertinence.” Sibyl gripped her shawl tighter and bowed her head “yes ma’am”. Sibyl turned and biting her tongue as she walked towards the stairs that lead to the sleeping quarters.” blessed..” thought Sibyl, "… easy to say when your husband is the governor of Jamestown. Not to mention that you probably knew his name at least” She’d wanted to turn and scream this at the woman. But the rational��side of her mind Knew better. Making an enemy of the governor's wife wouldn't be a wise move for her or for Verity’s future. She’d calmed down a little as she entered the sleeping quarter, most of the other girls had already turned in for the night, their lanterns blown out. Other were just finishing their prayers, Sibyl moved as quietly as she could to her bunk without disturbing them. S She reached into her bunk and pulled out her bag of belonging. Sibyl double-checked its content, unlike most of the other girl here she didn’t a lot to travel with. Happy that everything was as she left it that morning, Sibyl placed her shawl on inside before placing it back in her bunk to act as her pillow. She sat on her bed and looked for her sister, her eyes found sat with Alice and a blonde woman. Alice told her that the woman's name was Jocelyn Woodbryg after she’d seen them talking during a storm recently. According to Alice, she was just a lonely soul. Feeling her weariness making its presence known, Sibyl climbed into her bunk silently praying once last time before closing her eyes. “Please let him be kind.”

#Jamestown#James Reed#Sky#jamestown fanfic#Verity Rutter#James Reed x OC#Own Character#Sybil Rutter#sky jamestown

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you do all the nitty gritty wb asks! :o

Oh my, sure!

This took longer than expected and is longer than expected sooo under the cut it goes!

1. How/why did your clan get it’s name?

Sylvhurst gets its name due to the large tree that the Rulers live in. It used to house the ‘soul’ or ‘essence’ of Queen Azraea until a spell went awry and she became a dragon. ‘Sylv’ and ‘hurst’ are both tree/forest words.

2. Are there any other clans living near by? Are they friendly or are they rivals? Tell us about their interactions with your clan.

The closest ‘clan’ would be the Seelie Court, which is about a day’s travel south. The Seelie Court and Sylvhurst are allies who trade and lend eachother support in times of need. Given that the Seelie Court has a hidden entrance and is generally not entirely open to outsiders, most of the interactions between the members of both clans happens within the boundaries of Sylvhurst, or in the unowned sections of the Tangled Wood.

3. What is your clan’s main source of income?

Probably the sale of magical goods and services. The Mage’s Quarter makes up a huge portion of the city, and there’s a good variety of magical beings each offering up their own unique type of magic.

4. What items does your clan have to import from other flights/clans/etc? Who is in charge of that?

The biggest import is building materials, despite the fact that Sylvhurst is in the middle of a forest. Because of Queen Azraea’s origin story, very few buildings in the town are made of wood, and it’s actually fairly difficult to get permission to build houses out of it. Instead, stone buildings are far more common (much to the joy of the magic users who find stone much more receptive to any spells they attempt to place on their residence).

5. Does your clan produce any sort of item coveted by other clans? Specialty items, services, food/drink?

Sorta in relation to #3, I’d say maybe Perseus’s enchanted items would be one of the more popular items for sale in Sylvhurst. They’re notoriously reliable and he has a myriad of spells that he can place on all sorts of items.

6. Is you clan independent or is it ruled by another governing body?

My clan is independent in the sense that Syvhurst is ruled by itself I guess?

7. Is your clan religious? Is there a single dominating religion or belief system in your clan or is it relaxed about different faiths?

All forms of religion are welcomed into Sylvhurst, though those who are fanatics may find some strange looks and whispers their way. For the festivals Sylvhurst dresses itself up and has a huge celebration for whichever God the festival is for.

8. What sort of superstitions do many in your clan believe? Is there any merit to it, or is it just wives tales?

There’s plenty of superstitions concerning the forest surrounding Sylvhurst, and most of it actually does have merit. There’s been plenty of legends about a mysterious young hatchling with glowing eyes who guides lost hatchlings back to their parents. Or about a ghost who seems to show up before deaths or disasters, wringing his hands in worry. Or even stories about a cheerful young man who can be helpful one second and a thief the next, and what to keep on hand to give him in return for his aid.

9. Any serious taboos?

Queen Azraea has been known to welcome all sorts of dragons into her clan, and even offer second chances to dragons who have done some fairly illegal things. The one crime that is expressly forbidden within Sylvhurst, however, is slavery or any form of trafficking. Any slavers moving through the territory are liable to be targeted and either killed or escorted out of the lands once their prisoners have been released.

10. How is your clan operated? Is there a single leader, a council, or something else?

Queen Azraea and King Arguim (technically) have final say on decisions made for the entirety of Sylvhurst, but they employ a fair number of advisors on different matters. Trickmurk is the tactician who is technically the immediate supervisor of the Guards. Iravat, while being the main advisor is also the leader of a smaller and more elite force that is targeted to more ‘high danger’ targets (Think Emperor level danger). Undine is another important person who oversees the docks to the west and enforces import and export restrictions. For the most part these advisors are able to rule over their own sectors without the Queen and King stepping in and overriding their rulings.

11. How is food stocked, stored and inventoried for rations during the lean times? Is there a specific dragon in charge of that?

Huh... I actually don’t have an answer for this. I would assume that the process would start with Undine at the docks, and she would begin to enforce export restrictions on anyone attempting to ship food out to make money. Then, she’d likely attempt to reach out to contacts and attempt to acquire more shipments of food. If it got really bad the treasurer, Aurelius, would most likely be brought in to sequester a portion of his vault for dried / salted portions of food.

12. How are your clans defenses operated?

Sylvhurst has a few defenses, but not many because of its somewhat secluded location and relatively few threats that they have dealt with so far. One of the largest defenses is a ‘shield’ that is controlled by Harlequin, which essentially ‘steers’ malicious people away from Sylvhurst and sends an alert of the location. It acts as a sort of suggestion -- and it is by no means going to turn someone around who is actively attempting to reach Sylvhurst. It’s more to try and prevent random people from stumbling into town and causing trouble.

Other than that, there are a number of guards who are stationed at the roads that enter and leave the city. This does leave the wooded areas without defenses, however, because there simply aren’t enough guards to actually surround the city.

13. How is waste removed from the clan?

Can I pull a JK Rowling and say it’s just magically vanished

I’m not sure! Waste such as packaging and trash is likely somewhat rare within Sylvhurst. Many things are reused and even bones from things like fish can be sold to vendors within the magical quarters for a small amount of money. Maybe any left over trash is incinerated?

14. Does your clan have livestock of any kind?

Not within the walls of the city itself, no. However there are a number of farms that have carved their way along the roads leading into town and while most of them are crop farms there are a few that also have various types of livestock.

15. How is water managed in the clan?

Water is collected for use in a number of ways. Almost every house in Sylvhurst has some form of a rain barrel (either for drinking water or for use in spells) which is the primary source for a number of people. There is a freshwater lake on the northern edge of the city which some people collect their water from as well. The ocean is another possibility, especially for those who live in the harbor area, as there are simple enchantments that can be used to turn the ocean water fresh and clean. Everyone handles their own water needs for the most part, barring of course businesses and inns which manage a much larger amount.

16. Is there a community hatchery/nursery, or do parents rear their young separately?

Parents rear young within their own homes, though there are nurseries which can look after hatchlings if something happens to their parents or if their parents cannot look after them all day long on their own.

17. Who teaches the younglings the basics?

The role of teaching is generally given to the parents, or, if they don’t feel comfortable it’s possible to find a mentor for the hatchling. The real basics of life are handled by the parents, but once they begin to branch out there are a number of tutors or mages that are happy to indulge the odd question from a child.

18. How does your clan view Exaltation? Is it an honor, banishment, something else?

Exaltation is more personal than anything. Most in Sylvhurst form their own opinions about it from their own experiences with family members and friends deciding on it. For most, exaltation is simply a journey a dragon takes when they decide that they wish to serve their god in any capacity. It’s definitely not a banishment, and it’s also not exactly an honor. It’s simply a different choice.

19. If your clan has a diverse number of dragons of different elements, how does that affect society? Are some dragons prejudiced against certain elements/breeds? How does the clan handle this?

Sylvhurst is a melting pot of every single element present on Sornieth. While Prejudice may occur behind the scenes, it is fairly obvious that overt prejudice will not be tolerated by the people of Sylvhurst or the King and Queen. Most of the conflicts seen in the clan are actually conflicts between dragons of the same element.

20. Are there Beast Clans near your clan? How does your clan interact with the Beast Clans?

Given the scope and mystery of the Tangled Wood I’d guess that there’s not-a-small amount of Beast Clans wandering near Sylvhurst. As of right now, no Beast Clans have taken up residence within the territory of the city, but they do stop by the marketplace or the docks more than occasionally.

21. Are there some Beast Clans that are allies and others that are enemies?

I don’t have any actual Beast Clan OCs or anything like that, but I like to think that Sylvhurst is a bit more friendly to Beast Clans than is regular for dragon clans. Many of them know the story of Azraea’s transformation and the dryads especially feel a kinship to her that they don’t feel towards dragons often.

22. Is your clan located near where the Emperor was sighted last? How is it preparing for that?

(I’m running on the assumption that the Emp was in Light territory because I don’t feel like looking it up lol). Sylvhurst is somewhat far from the border between Shadow and Light, so they’re not too concerned quite yet. The Queen and King aren’t doing many preparations other than the usual defenses. If it started moving closer, they might start taking preventative actions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

@northliights sent me a meme forever ago and agreed to ship with me when i asked and is now paying for all of it and no doubt regretting all of his life choices (especially sending me a fucking aurora was kidnapped meme)

Somewhere, in what sometimes still feels like another world entirely, a version of Lucas North had curled under an empty metal bed frame, pleading with words that spilled from broken lips, a raspy and whispered prayer to the unrelenting artificial sun that refused him a reprieve. Dark was where the demons are meant to hide, monsters with curled claws lingering in shadowed corners ... but the mi5 agent had spent eight years in unrelenting light, and found the absence of hope underneath it. He had promised things, sold his soul in more ways than he can possibly remember, but always there was the blinding light and the pain until suddenly there was’t ... and on nights where he watches the brilliant light that heralds the return of a welcome darkness, he sometimes wonders what last desperate thing he had promised... wonders if the devil will ever come and collect its due....

It does, eventually. Evil is a patient thing, waits like a master of its game, studying the board before each move, and the pride of believing ones self capable of out maneuvering it is ever the banner before a man’s fall. Lucas has always known this, has wondered about the price he will one day have to pay, resolved to pay it without question. But now..

Not her. God, not her.

The man that walks in front of him is trembling, shoes slipping on the blood of his friends and dark eyes glancing down at the bodies that the mi5 agent barely notices and as he gives his prisoner another shove for motivation, Lucas briefly wonders if the shorter man believes he’ll survive this. Surely he’s not that stupid. His guide stops at a door in the back of the warehouse, hands that have been steady throughout the entire past few days suddenly beginning to shake, and he tightens his grip around the gun in his hand, pressing the muzzle forward until it digs harder into the sensitive skin between the knobs of his captive’s spine. Ocean blues watch as the other man fumbles for a key, a choked foreign word that he doesn’t recognize falling between them as the door finally swings open.

I knew you’d find me ....

The statement is a simple thing, soft and full of an affectionate relief that settles somewhere in the hollow of his chest until that cold hold around his barely beating heart begins to thaw. A smile twitches into place at one corner of his mouth, shoulders losing their tension as worst case scenarios are thrown from his mind, leaving room for a bone weary exhaustion. He wants nothing more than to gather Aurora in his arms, to find some sanctuary from the entirety of the world and never let her leave his sight again .. but first...

His gun relieves its pressure against his captive’s spine and sharp gaze takes in the way the other man takes in a short breath, relief so palpable that Lucas can almost smell it. Mistake. A quick press against the shorter man’s head chased by a shot that echoes off stark concrete walls and his guide is suddenly nothing more than a corpse at the agent’s feet, a body in perfect repose. He’s covered in blood, the sweat of fear and the smell of a desperate man that’s hardly slept and as brown boots cross the floor between them, fingers already reaching for the ties that bind her wrists and making short work of them before he trusts himself enough to speak.

“Hey, beautiful girl.”

His voice is a rough and broken thing, words hard to push past a sudden lump that’s taking up the length of his throat and for the briefest of seconds, when Aurora reaches with a gentle touch to brush against his cheek, Lucas wonders if he’s bleeding from some wound he wasn’t aware of .. but her finger lingers, swiping across a lingering wetness that doesn’t hurt and it hits him like a ton of bricks .. he’s crying. He’s too exhausted to try and stop it, doesn’t care to anyways .. instead, he simply wraps his arms around her all the tighter, unmindful of the blood and salt that paint their shadows across her clothes and baptize her hair.

Evil always collects its due .. but she is his dawn and he will gladly crucify himself again.

#northliights#I 'M SOBBING BYE#*v. you can only go through hell a handful of times before you bring pieces home.#i was stupid when i made this blog for this kind of pain. and you were stupid for lettin gme and going along iwth it#anyways idk if you can reply to this or if its a one time thing#i leave it up to you#but i am feeling the feelings goodbye.#HE SAYS THREE WORDS I'M FUCKING SCREAMING#*THREE* FUCKING WORDS

1 note

·

View note

Text

get in the car

get in my car. lets drive, never will we push the break, until the world ends... some boy far away went to war. picked up a gun sold by another state, his green camouflage dripped off his frame, his comrades told him he must be brave. he died on the first day before he saw the eyes of enemy which was not there before he could ask "is this it?" - battle of yester days, pride and eye to eye is dead with him; coins and land change hands... put your feet on my knees, sleep while i take us where no one remembers guilt and lies, where we change the world like bullet through still pond. they will have no choice, to learn that kiss between a man and woman is the roots of beauty and universe expands every time - universe just smiled - it is the only abstract non-existence that makes sense; how else then, the universe could have come to be?... a generation without mothers screams: "thoughts of old must be gone" a generation without fathers declares: "you were all wrong", but you and i, we know: they stopped listening to their soul. we know that parent's eyes spoke the truth: everything else is like wind around calm in the center of a storm. beauty never moves... lets drive through the desert there will be no water until we reach men chose to shallow rivers, rid lakes of depth - for ease of walking through - sun does the rest. but i will drive our car off the pier, in the ocean we will swim.... ants in colony do not comprehend their roles even if they say "i am." there is an invisible force, it plays the strings of the guitar between oxygen and stars, and laughs at our declarations of momentary cause... i will show you how to be free! just get in my car and recline the seat. love is inspiration, and inspiration is not thinking about death. passion is the glue. all three will make us envy of old gods. our parents knew: that is the only way to break through.

0 notes

Text

I love pear-shaped girls so much

Name: Apolline Lycotonum

Name meaning: Apolline is a vintage French, derived from the sun god Apollo, while Lycotonum is Greek meaning “Wolf’s bane” and refers the plant of the same name.

Age: 11 (Debut Episode)

21 (Final Episode)

Birthday: May 24 1994

Family: Lucinda Lycotonum (Mother), Belphegor (Father), Atticus Lycotonum (Younger Brother), Korinna Lycotonum (Grandmother, dead), Silas Lycotonum (Grandfather), Lycotonum Coven (Maternal family)

Appearance: Apolline is a beautiful girl with dark voluminous wavy hair that reaches her hips which she often tucks under wigs, fair skin, small button nose, almond shaped eyes, one red, the other green-blue, with pupil shape similar to a typical demon, which she can disguise to appear as normal eyes, slightly plump lips, and curved eyebrows. She's noted to be tall, being 5'10" and is noted to be rather curvaceous and slightly chubby. Apolline's typical style is lolita fashion, not a specific category, she'll change it up some weeks she'll dress sweet lolita, others it'll be gothic, and she also owns "normal" clothing such as T-shirts and jeans for when heavy lifting is required, or she doesn't have the time to dress up.

Personality: Apolline is suave, but she loves to use insults, sass and banter. She uses smooth, gratuitous sexual innuendo in an effort to make people uncomfortable and therefore give herself an advantage. She is a survivor at heart, and will use any means to accomplish this goal. In fact, she tends to only lose her temper when her personal safety is threatened or when dealing with what she considers overwhelming stupidity. Apolline at times appears incredibly volatile under her smooth and charming personality, as when she has screamed at multiple people, including Andrew and Nicole Lee, when appearing calm only seconds before.

She shows tendencies that can be seen as mischievous by her mother, and devious by others, such as causing a fire hydrant to explode in order to flood a street, or causing a teacher’s car to explode. One very disturbing detail about Apolline is that she has a massive crush on Lucifer, getting flustered when she can sense his presence. The general population of the school she goes to hates her, as she remodeled the whole surrounding neighborhood, forced the principal to adapt stricter policies, and forced parents to sign contracts that made them agree that whatever their child did was their responsibility, but they can’t do much as there is the constant looming threat of her ruining everyone in the school with a snap of her fingers. She describes herself as a young lady with refined, and classical tastes, having her school rebuilt so it was a French gothic style, her room being filled with classic literature in its original language, her home being modeled after Greco-Roman architecture, etc. etc.

There are so many ways to describe this girl, but the easiest way to do so was through Apollo’s lyre, which played a tune with loud, heavy beats that almost stopped Samson’s heart, all because she touched the lyre.

Likes: Bread, embroidery, tiramisu, green, Cymbidium, earth magic, baking, alchemy, ancient sports

Dislikes: Blue, cats, when her father bothers her, tomatoes, chunky tomato sauces, when her dresses get ruined, clothing with religious ties or imagery, modern sports (such as football, soccer, basketball, baseball etc. etc.)

Abilities: Apolline was born to a witch mother, and a demon father which has numerous advantages, Apolline knows magic, to start. Her specialty being elemental-based magic, specifically earth-based magic, turning any object made from the earth to protect her and to attack for her. There’s a special place in her heart for the abilities she gained from her demonic heritage, such as telekinesis, which she occasionally uses to toy with classmates. There’s also self-healing, Apolline can heal herself from vast array of wounds, small or large, due to a self-preservation seal that her mother put on her when she was born, the seal can heal her, and can bring her back from the dead unless someone kills her with a special knife made to kill her kind.

Like most demons, full or partial, Apolline can be harmed by crosses, holy water, holy oil, or spoken passages from the bible, if someone were to try and perform an exorcism on her it would cause excruciating pain, resulting in her eyes beginning to bleed and a rash appearing on her body. It’s not just Christian iconography that can harm her, iconography from all Abrahamic religions can harm her, even once she couldn’t be in a graveyard because there was a grave marker with a Star of David on it. Other weaknesses include blood of a holy man, such as priest, monks, rabbis, etc., certain sigils and seals, angel weapons, being unable to enter holy sites, and manipulation collars. Another weakness, which considered strange by many but true for all female witches, is that if you cut off a certain amount of her hair, it causes her to lose her magic, which will tick her off, and it means she has to wait until her hair grows back for her to use her magic.

Lucinda taught Apolline many things, one of them was multilingualism, Apolline knows almost all Germanic languages, with Turkish being her first language, and some very ancient languages such as Aramaic, Akkadian, and Persian, the only problem is that due to her age and where she lives there really is no use to knowing that many languages, unless it’s for spell work. Whenever she uses her magic, her eyes begin to glow, and temperature begins to drop, the downside to using her demonic abilities is that she needs to eat souls, 50 souls to be exact, she has been able to find loopholes, eating souls of animals, but there are times when she really needs it, so she’ll eat the souls of random people.

Background: Apolline Lycotonum was born on May 24 1994, to Lucinda Lycotonum, a witch from year 1444, and Belphegor, a demon and a lieutenant in Hell. Lucinda originally planned to hide the identity of the father until Apolline was 18, but Lucinda’s mother Korinna kept pressing the matter, so Lucinda killed her before Apolline was born. Apolline was raised in Turkey, for no particular reason besides the fact that her mother liked Turkish baths, during her early childhood she remembers her mother training her to use magic, usually in questionable methods, such as throwing her into the ocean, stranding the two in the middle of a jungle, or having Apolline perform a handstand and holding that position while reading a spell book. When she was 8 her mother sold her to be a millionaire’s servant, but in reality her mother wanted to steal a grimoire from the wife, so after months of infiltration Apolline finally located the grimoire and was getting ready to steal it, but was caught by the wife who tried to kill her, with no other choice Apolline killed the whole household, and ran off with the book. After Apolline returned with the book, mother and daughter pack their bags and fled to America. When she was 10 Apolline met her father, on complete accident, Apolline was defending herself from an angel that came to smite her after she opened a spell book, she tried the first spell she set her eyes on, which was a demon summoning spell, her father Belphegor rose from the pits of Hell and killed the angel. Belphegor called her Lucinda at first, mistaking the young girl for her mother, causing Apolline to become confused, and the two slowly realized that they were father and daughter. Apolline questioned her mother, and Lucinda confirmed that Belphegor was her father.

Nothing much happens afterward, but Apolline’s debut episode begins with her being responsible for siccing hellhounds on people.

Family Name Lore: The Lycotonum Coven originally started as a high class coven known as the Ricinus Coven, that had a rivalry with Liulfr Coven dated back to Alexander the Great’s time. This rivalry was like war, it was a constant cycle of killing and robbing, until Lucinda was born in 1444, Silas, Apolline’s grandfather, married into the family from a Mongolian coven, he changed his name after marrying Korinna, and led a night time mission to end the rivalry. Silas led the coven to the home that the Liulfr Coven lived in, and ambushed the coven, killing almost all except the 5 defect children, he left those children alone so they can warn other covens not to mess with the Ricinus Coven. After Liulfr Massacre, Silas requested that the coven change the name to Lycotonum to mock the surviving members of Liulfr, as Liulfr means “Wolf” and Lycotonum means “Wolf’s Bane”.

1 note

·

View note

Text

they wanted to trick Him

to sneak around and capture Him, in order to arrest and do away with our Creator, the very One who made the heavens and beautiful earth.

betrayed.

An act we read of in Today’s chapter of the New Testament in the 26th chapter of Matthew:

And so this is what happened, finally. Jesus finished all His teaching, and He said to His disciples,

Jesus: The feast of Passover begins in two days. That is when the Son of Man is handed over to be crucified.

And almost as He spoke, the chief priests were getting together with the elders at the home of the high priest, Caiaphas. They schemed and mused about how they could trick Jesus, sneak around and capture Him, and then kill Him.

Chief Priests: We shouldn’t try to catch Him at the great public festival. The people would riot if they knew what we were doing.

Meanwhile Jesus was at Bethany staying at the home of Simon the leper. While He was at Simon’s house, a woman came to see Him. She had an alabaster flask of very valuable ointment with her, and as Jesus reclined at the table, she poured the ointment on His head. The disciples, seeing this scene, were furious.

Disciples: This is an absolute waste! The woman could have sold that ointment for lots of money, and then she could have given it to the poor.

Jesus knew what the disciples were saying among themselves, so He took them to task.

Jesus: Why don’t you leave this woman alone? She has done a good thing. It is good that you are concerned about the poor, but the poor will always be with you—I will not be. In pouring this ointment on My body, she has prepared Me for My burial. I tell you this: the good news of the kingdom of God will be spread all over the world, and wherever the good news travels, people will tell the story of this woman and her good discipleship. And people will remember her.

At that, one of the twelve, Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests.

Judas Iscariot: What will you give me to turn Him over to you?

They offered him 30 pieces of silver. And from that moment, he began to watch for a chance to betray Jesus.

On the first day of the Festival of Unleavened Bread, the disciples said to Jesus,

Disciples: Where would You like us to prepare the Passover meal for You?

Jesus: Go into the city, find a certain man, and say to him, “The Teacher says, ‘My time is near, and I am going to celebrate Passover at your house with My disciples.’”

So the disciples went off, followed Jesus’ instructions, and got the Passover meal ready. When evening came, Jesus sat down with the twelve. And they ate their dinner.

Jesus: I tell you this: one of you here will betray Me.

The disciples, of course, were horrified.

A Disciple: Not me!

Another Disciple: It’s not me, Master, is it?

Jesus: It’s the one who shared this dish of food with Me. That is the one who will betray Me. Just as our sacred Scripture has taught, the Son of Man is on His way. But there will be nothing but misery for he who hands Him over. That man will wish he had never been born.

At that, Judas, who was indeed planning to betray Him, said,

Judas Iscariot: It’s not me, Master, is it?

Jesus: I believe you’ve just answered your own question.

As they were eating, Jesus took some bread. He offered a blessing over the bread, and then He broke it and gave it to His disciples.

Jesus: Take this and eat; it is My body.

And then He took the cup of wine, He made a blessing over it, and He passed it around the table.

Jesus: Take this and drink, all of you: this is My blood of the new covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. But I tell you: I will not drink of the fruit of the vine again until I am with you once more, drinking in the kingdom of My Father.

The meal concluded. Together, all the men sang a hymn of praise and thanksgiving, and then they took a late evening walk to the Mount of Olives.

The Book of Matthew, Chapter 26:1-30 (The Voice)

and from the paired chapter of the Testaments with Matthew 26 we read in Ezekiel 33 of the way each of us have been offered the choice in life in how to conduct ourselves, for better or worse. and what humbling Oneself and repentance points to is a welcoming of grace which is clearly revealed in the New Covenant in the True illumination of the Son.

from the ancient writing of Ezekiel:

“Tell them, ‘As sure as I am the living God, I take no pleasure from the death of the wicked. I want the wicked to change their ways and live. Turn your life around! Reverse your evil ways! Why die, Israel?’

“There’s more, son of man. Tell your people, ‘A good person’s good life won’t save him when he decides to rebel, and a bad person’s bad life won’t prevent him from repenting of his rebellion. A good person who sins can’t expect to live when he chooses to sin. It’s true that I tell good people, “Live! Be alive!” But if they trust in their good deeds and turn to evil, that good life won’t amount to a hill of beans. They’ll die for their evil life.

“‘On the other hand, if I tell a wicked person, “You’ll die for your wicked life,” and he repents of his sin and starts living a righteous and just life—being generous to the down-and-out, restoring what he had stolen, cultivating life-nourishing ways that don’t hurt others—he’ll live. He won’t die. None of his sins will be kept on the books. He’s doing what’s right, living a good life. He’ll live.’”

The Book of Ezekiel, Chapter 33:11-16 (The Message)

and turning to inspiration from Today’s Psalms to accompany this:

ONLY those who stand in awe of the Eternal will have intimacy with Him,

and He will reveal His covenant to them.

The Book of Psalms, Poem 25:14 (The Voice)

For the word of the Eternal is perfect and true;

His actions are always faithful and right.

He loves virtue and equity;

the Eternal’s love fills the whole earth.

The unfathomable cosmos came into being at the word of the Eternal’s imagination, a solitary voice in endless darkness.

The breath of His mouth whispered the sea of stars into existence.

He gathers every drop of every ocean as in a jar,

securing the ocean depths as His watery treasure.

Let all people stand in awe of the Eternal;

let every man, woman, and child live in wonder of Him.

For He spoke, and all things came into being.

A single command from His lips, and all creation obeyed and stood its ground.

The Eternal cripples the schemes of the other nations;

He impedes the plans of rival peoples.

The Eternal’s purposes will last to the end of time;

the thoughts of His heart will awaken and stir all generations.

The nation whose True God is the Eternal is truly blessed;

fortunate are all whom He chooses to inherit His legacy.

The Eternal peers down from heaven

and watches all of humanity;

He observes every soul

from His divine residence.

He has formed every human heart, breathing life into every human spirit;

He knows the deeds of each person, inside and out.

The Book of Psalms, Poem 33:4-15 (The Voice)

with a reflection of the lines of Psalm 33 read in Psalm 148 where all of True nature (in the heavens and on earth) is told to worship God:

[Psalm 148]

Praise the Eternal!

All you in the heavens, praise the Eternal;

praise Him from the highest places!

All you, His messengers and His armies in heaven:

praise Him!

Sun, moon, and all you brilliant stars above:

praise Him!

Highest heavens and all you waters above the heavens:

praise Him!

Let all things join together in a concert of praise to the name of the Eternal,

for He gave the command and they were created.

He put them in their places to stay forever—

He declared it so, and it is final.

Everything on earth, join in and praise the Eternal;

sea monsters and creatures of the deep,

Lightning and hail, snow and foggy mists,

violent winds all respond to His command.

Mountains and hills,

fruit trees and cedar forests,

All you animals both wild and tame,

reptiles and birds who take flight:

praise the Lord.

All kings and all nations,

princes and all judges of the earth,

All people, young men and women,

old men and children alike,

praise the Lord.

Let them all praise the name of the Eternal!

For His name stands alone above all others.

His glory shines greater than anything above or below.

He has made His people strong;

He is the praise of all who are godly,

the praise of the children of Israel, those whom He holds close.

Praise the Eternal!

The Book of Psalms, Poem 148 (The Voice)

my personal reading of the Scriptures for October 25, the 33rd day of Autumn and day 298 of the year:

0 notes

Link

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/my-family-s-slave?utm_source=pocket-newtab

This article was originally published on May 16, 2017, by The Atlantic, and is republished at https://getpocket.com/explore/item/my-family-s-slave?utm_source=pocket-newtab with permission. That is where this blogger viewed it on September 14, 2019 and shared it on Tumblr.com.

Pocket Worthy·

Stories to fuel your mind.

My Family’s Slave

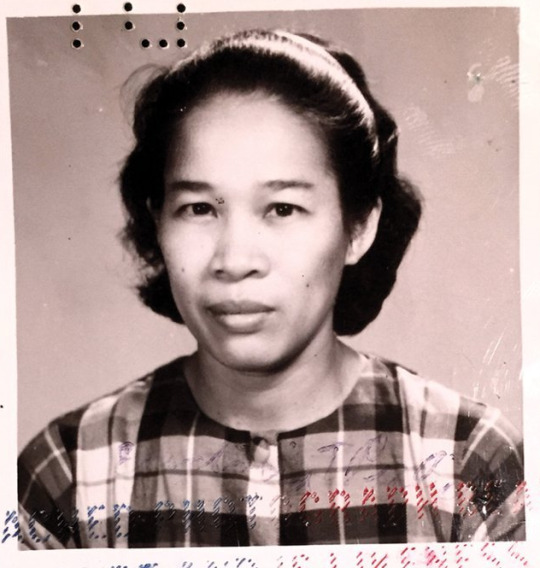

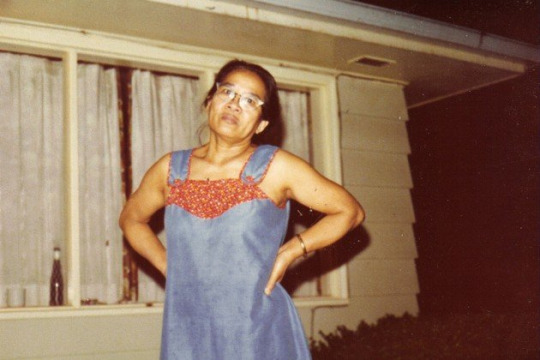

She lived with us for 56 years. She raised me and my siblings without pay. I was 11, a typical American kid, before I realized who she was.

The Atlantic | Alex Tizon

All photos courtesy of Alex Tizon and his family.

The ashes filled a black plastic box about the size of a toaster. It weighed three and a half pounds. I put it in a canvas tote bag and packed it in my suitcase this past July for the transpacific flight to Manila. From there I would travel by car to a rural village. When I arrived, I would hand over all that was left of the woman who had spent 56 years as a slave in my family’s household.