#hellenistic air force

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

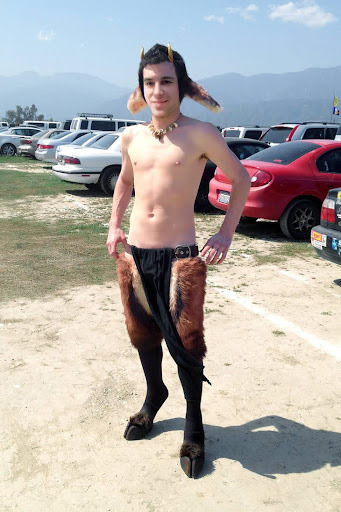

Halloween Bacchanal

Greek god of madness just wants to see some fun this Hallow's Eve- what better place to start than with little Theo and his satyr costume.

Happy Halloween! Here's my take on everyone's favorite Halloween TF trope: men dressed as satyrs, knights, cowboys and more become what they wear at this hedonistic Halloween party! Hope you enjoy! - Occam

Greek mythology has been an obsession of Theo’s as far back as he could remember. From what his parents say he would force them to read him myths rather than fairy tales before bed each night before going on to spend his waking hours punching way above his literacy level to indulge in every scrap of the Hellenistic pantheon he could stumble across. His dreams were filled with visions of himself aiding Hermes in his tricks and cheering on Heracles in his trials.

It’s no surprise that his time spent in this mythological world influenced his sexuality. What with all the muscular men and tales of transformation he ravenously consumed it doesn’t take a detective to follow the throughline to his present self. In fact he can clearly remember stumbling on a far too steamy illustration of a satyr right when he was about that age that clearly had some deep-rooted repercussions. Which, no surprise, brings him to his current Halloween costume.

He never thought he’d have the confidence to dress up as one but what the hell right? It’s what halloween’s for, just a spot of fun and indulgence. Once he finally decided on biting the bullet and dressing up as his root and began construction on his little costume it’s like he was possessed. Hands worked deftly sewing goat legs and sculpting horns and hooves and before he knew it he was finished before he even realized he had begun.

When the party finally arrived he found himself walking on his toes with a shocking ease, though despite the apparent expertise, his knees began to shake more with each step towards his friend’s apartment. Theo takes a deep breath before knocking on the door, sweating despite the chilly air of autumn against his bare skin. Before he does so the door creaks open and Theo’s greeted by a man he’s never seen before.

Man is almost too inconsequential to describe him. As soon as Theo’s eyes land on him he feels content to spend every waking moment for the rest of his life simply staring at this figure. Dark skin somehow glimmering in the dim light, his teeth sparkle as his lips pull into a smirk. He then turns his gaze onto, into, Theo. It’s as if he were looking through the costumed man, languishing in his past and imagining his future, taking in everything Theo has been, is, and will be. And before a moment passes he shifts to look Theo directly in the eyes, raising a hand to cup his head as if it were a glass, he rumbles out, “I love your costume dear.”

His touch is electric to Theo’s skin, or no not electric, magnetic. The fingers clutching the young man’s jawline leave him wanting more, needing more. Despite feeling frozen in the gaze of this too-ideal figure he craves more than anything to be closer. Lost in his desires, Theo flinches as his ability to ambulate returns and the figure in front of him laughs as he plays with his words, “Dear- Or should I say faun Ah Hah!” Barely a joke, but as the figure begins guffawing Theo cannot help but reciprocate. Compulsive, heaving roars of laughter fill him with ecstasy and delight as memories of raucous nights and impossible debauchery soar into his mind. More real than reality he sees himself with a cup of wine in hand standing in audience of the man now before him.

Just as soon as it began, his laughter jarringly stops and he pulls Theo close and whispers in his ear, “Call me D.” Theo gasps as he is brought closer to D’s form and the intensity of his delight only continues to heighten. Every inch of his exposed torso is suddenly burning with intense pleasure and he shivers as his neck is grazed by D’s sticky breath. In a moment briefer than Theo is able to even grasp, a thought flickers across D’s expression before he looks down at him and his eyes glow a vibrant violet. D stretches his back, doing something between a shrug and a warm-up. Theo trembles at the feeling of his powerful traps and delts moving, allowing him to feel the power they hold as the men stand in each other's grasp.

D once more grabs Theo’s chin, this time angling it up as he cranes down to meet the party-goer’s lips. It’s not quite right to say the kiss was explosive but Theo has no better way of understanding it. It’s as if he were being suffused with power, as if the man’s lips were casting a spell, as if he were drinking in a force of pure energy. Physically, his taste buds are overwhelmed with the taste of wine, richer than any he’s had the chance to experience heavy and sweet and greater than anything.

Theo, sure that he’s dreaming, clutches the man tighter as their lips and tongues continue to dance. If D’s laughter instilled him with memories, their kiss infused something far more real in his mind. Mouth awash with wine, touch burning with pleasure from being lucky enough to touch the man’s powerful form, Theo opens his eyes and rather than seeing the world he knows he was in, he sees D tied up on a ship. Before he can make sense of his surroundings the man breaks from his bonds and the men who must be his jailers flee, hopping overboard before D waves his arms and they are no longer men. He knew the true name of D as soon as wine graced his tongue but it is further confirmed by a vision of him carrying his mother from the mouth of a cave before he sees her apotheosis. He sees grapevines sprouting from arid earth and finally sees the man, the god, bestowing Midas’ golden touch.

These are all brief passages however, pauses in between the meat of Theo’s visions. Accompanied by D, by Dionysus’ laughter, Theo sees hordes of satyrs and nymphs dancing in fields and in forests. He sees wine dripping through thick beards and staining hairy chests. Theo watches revelry devolve into madness as festivities rapidly degenerate from dances to orgies in grass fields. Shifting to an aristocratic masquerade he sees a crowd of straight-laced prim and proper nobles spin in clearly practiced circles until Dionysus, sitting at the main table, rolls his eyes and removes his mask. Calling their attention to himself as soon as they glance in his direction they are changed, filled with bestial need as they return to their partners with an animalistic fervor.

Theo knows these visions should fill him with fear, they are far too real to be dreams. Despite that, despite himself, the scenes only excite him more. He doesn’t know why the god has chosen to show him these events, why he has chosen him, but then he realizes he doesn’t care. He just needs to experience the same. His chest quivers with struggled breaths as he feels consciousness waning as he lies in the god’s arms. With a blink he sees D’s face once more, clearly experiencing more pleasure than Theo could ever offer. His vision begins to fade and his body goes limp in the god’s arms. Theo sees some look of care in D’s eyes that is promptly wiped away with a wink. Smirking, he whispers to Theo, “Hope you lot have fun with my gift-” The sound of the god’s laugh echoes through his empty mind, lulling him to sleep while whatever gift Dionsysus intends for the party festers within him.

When Theo awakens the party is in full swing. He remembers meeting D clearer than anything but everything between that moment and now is obscured. He feels a wet patch in his crotch and quickly crosses his legs to hide the mess made in his excitement. Seeing that he’s finally awoken, his friend Kevin, clad in a cowboy costume, walks over and greets him. “Yoo dude what’s up! Glad you could make it, you know it’s a costume party though ya? Hahah!” Theo narrows his eyes, preparing to call out his friend for being so drunk as to not see the horns on his head before he feels for them and realizes that they are no longer on his head. Indeed, glancing at his crossed legs he finds he’s fully not wearing the costume he so intently made.

Clutching at his chest, his face burns with embarrassment as he so clearly remembers working up the confidence to come here without a shirt on and yet, here he is just wearing a T-shirt and jeans. Seeing his friend rapidly nearing tears Kevin puts his drink down and apologizes, “Hey hey buddy- Sorry I didn’t mean to press you. Do you want to go get some fresh air?” Theo sighs looking at Kevin’s outstretched hand, pouting for a second longer before reaching out to grab it. Never could he truly know what he is about to unleash when he takes it.

How could he, he was still under the impression that his little episode with Dionysus was just that, an episode. Some weird little dream that led to him cumming on a friend's couch like a loser. That is, until Kevin grasps his hand and grows glassy-eyed. Natural color briefly overtaken by a lilac haze, Theo is immediately concerned, “K- Kevin? Did you get some, um weird contacts?”

His friend shakes his head, not out of his stupor but further into it. He clears his throat and his voice is unmistakably deeper, rougher, “Now why’d I go and do somethin’ like that partner?” Theo feels the hand in his own thicken and grow calloused as tanner skin leaks up his forearm. Hair pokes out of Kevin’s wrist, rapidly thickening and growing dark as it matches pace with his increasingly sun-kissed arm. He breaks the handhold and Theo falls back in shock. Kevin stretches and whistles as biceps bulge under his costume which similarly changes texture from cheap linen to dense torn cotton that one would need in his line of work. His line of work?

“Whoooee! Maybe we’ll skip the fresh air eh Theodore? Love to see what else yew can do with those hands.” Theo stutters as the man starts rubbing his back, “I- You-” Kevin’s jaw widens and grows thick stubble as his brow hangs lower over his eyes, a piece of wheat lolls out of his mouth as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Theo pushes away and the cowboy raises a hand in surrender while adjusting his large belt buckle with the other, “‘Ey now no problem amigo, we’ll put a pin in it. Check back in after spreading the love-” He scratches his newly stubbled jaw and tug once more at his crotch as an unmistakably growing package begins to need far more room than his chapped levis could allow. Staring at a man holding a few swords with shoddily sprayed green hair, Theo almost swears he can see Kevin’s dick throb as he begins tugging at his belt.

The young man doesn’t have time to question whatever unthinkable thing he just did to Kevin as he is struck with a headache greater than anything he’s experienced before, as if something were pushing its way out of his head. Throbbing with pressure he clutches at his head and feels two bumps forming and his eyes widen in fear as he remembers the parting words of the olympian, hope you lot have fun with my gift- Across the room Theo hears the voice of the swordsman grow gruffer as Kevin puts an arm on his shoulder. He hasn’t a chance to investigate as itchiness begins to rise across his body.

Theo quickly lurches to his feet and finds it difficult to keep his heels on the ground, as if he has always walked on the tips of his toes. He grunts and keeps his head down, trying to not draw attention to himself as he stumbles to the bathroom. He bumps into another party goer wearing a homemade spiderman costume who grabs him before he can fall.

Fearful that he’s introduced another point of impossible contagion into the party, he looks up and confirms his fears as the padded muscle disappears to be replaced by the hardened abs and arms of a superhero. The man takes off the mask to reveal he’s Theo’s friend Mark, though eyes exposed Theo can’t help but see the lavender corruption in his taking over as his hair throws itself into a middle-part. Grunting as he inches taller, his other web-shooter begins to poke into his friend. Theo runs before he hears whatever smarmy one-liner falls from the lips of a man whose name is Mark no longer.

Miraculously the bathroom is unoccupied when he stumbles in, painstakingly ensuring that his heels stay on the floor with every step. As soon as Theo crosses the threshold he is overwhelmed with a burning itch. Before he even has a chance to check his reflection he’s filled with a supernatural urge to remove his shirt. Ceding to the impulse he no longer sees the unimpressive chest he woke up with this morning, pecs have begun to pad his chest while his few chest hairs have begun to spread like weeds in its center. He clutches at the new pounds of meat piling onto his form and bites back a moan as it fills him with visceral pleasure as his fingers trail through the field of chest hair that is growing thicker.

Only then does he turn his eyes to the mirror and discover that the changes are not limited to his newly-muscled chest. While hair continues to trail down his thicker torso to his similarly strengthening stomach, the hair on his head begins to lengthen and curl as two horns begin to rise above them. His shaky hands go to tug them off as if they were an accessory which only causes his neck to jerk. Leaning in close he parts his hair and clearly sees the keratin growing forth from his skull. Beyond his new spikes he has somehow missed the darkening of his face as just like Kevin, stubble has begun to make its home on his cheeks. Rapidly growing sideburns shoot down his jawline as a real goatee lengthens on his chin.

In shock he falls back against the wall of the bathroom, accidentally losing his footing and catching himself standing on the balls of his feet like he has so pointedly tried to avoid. No longer is it possible to force his heels down as his toes are overtaken by the transformation, hardening and becoming impossibly imobile as they are covered with black keratin. New hooves burst out of his shoes while his pants begin to stretch at an odd angle from legs changing beneath them.

Falling to the floor Theo cries out as he tears at the pants he swore he didn't throw on as his legs irrevocably leave humanity behind. Voice pitching deeper and shifting rougher as his thicker hands struggle against his clothes, he feels the new treasure trail on his stomach thicken as it rises from a bush of pubes so dense that they could be labeled nothing other than fur.

While his hands are unable to make progress tearing at his pants, his growing thighs make light work of the garment as they begin to flourish with fur, rapidly covering with curls thick enough to totally burst the tight pants to tatters. His hands trail upward from his hairy legs, feeling the forest of fur give way to the thick human hair that covers the rest of his torso. He blushes imagining finally becoming a creature he always dreamed he could be.Thick hair trails down his forearms and the smell of the wild rises from pits to be evermore unwashed. His hair continues to lengthen and tangle as he truly becomes a spirit of the wild, a spirit of unchained lusts and unending gaiety.

Rubbing his sweaty body against the floor, hearing his new hooves clatter against the tile, Theo feels his mind begin to be overrun with the instincts and ideas of a creature whose primary goal is the spreading of mirth and the heightening of hedonistic desires. Fear of what he wrought upon Kevin and whatever other transformations launched on the other side of the door falls completely to the wayside as the idea suddenly does nothing but increase his own excitement, his own lustful desires. Groping at the decidedly still human cock hanging in between his thick thighs, Theo finds himself certainly more gifted in this department as well, heavy balls send lustful hunger coursing through him while his new powerful rod stands high and drips with pre. Theo smirks as sweat more powerful than any aphrodisiac trickles from his pores and he stands to a new height.

Were he to exit he would stand a few heads taller than anyone else fortunate enough to be in a room with him, his cock would be fencing with their torsos, and something within him tells him that it’s not beyond him to grow even more formidable. Though latching onto that idea, he realizes the true nature of the gifts bestowed unto him. He instead shifts into a form more enticing to whatever partygoers remain that need further enticing. The new satyr hides his beastier parts and watches as his reflection seamlessly shifts into that of a wild man whom no one would be able to turn down.

His hairy torso still glistens with sweat while he trades his hairy legs for sweatpants that could scarcely hide the powerful package hanging from his crotch. Smirking at his new form, Theo steps out to see what has become of his new domain. Exiting back into the steamy gathering he finds that festivities have not slowed down in his absence. The crowd around the cowboy has multiplied and devolved into quite the intimate pile of bodies, muscled arms and deep moans shoot through the air as every outsider that the horde bumps into finds the idea of joining rather appealing. He sees a man dressed as a caveman beating his chest as weight piles on and instincts take over.

Likewise the costumed superhero that was once Mark has found a crowd of his own. Mask pulled up over his mouth to find dozens of other costumed men wanting for him. Even before he changed he was charming, and now with a body made for the big screen it’s no wonder the crowds are clamoring for him. Though he hasn't the time to spend nearly as much time as his fans desire, after the shortest of moments spent with the amazing man himself they likewise begin filling out. Costumed congregants soon enough find themselves more than willing to spread their gifts with any number of lolling mouths around them.

Theo’s hungry eyes and wanting cock feel the compulsive awareness that there remain attendees deliberately avoiding the pleasures that await them. Point in case, he turns to the balcony to find one of his friends, Peter, dressed up as a knight and hiding from true jubilation. Theo’s lips twitch as he imagines corrupting his bookish friend into someone that can finally let loose.

Prior to the party the two discussed their costumes at length. Both spent a good chunk of energy and care in preparation, Peter’s dressed as his longtime DND character. Just like with Theo, the costume had long been a fantasy for the young man. That is to say, isn't it only fair that he get to experience the real thing just like the satyr? Theo doesn’t hesitate to answer the question as he makes his way towards his friend. Peter jumps as the sliding door creaks open and his friend steps out onto the balcony.

��Jesus- oh? Theo? Is that you?” The satyr smirks as he sees Peter’s anxious eyes appraise him. He contorts his body in just the right ways to get the paladin off his guard, stretching to show the power that rests within him rather than simply flexing. Inviting Pete to wonder what this new form is capable of rather than simply performing a brash display of brutish strength.

Peter blushes though remains guarded, “I um, I thought you were dressing up as a satyr?” Theo tilts his head before laughing at having forgotten his glamor, with the flick of his hand horns return to his head and Peter once more jumps back, though now facing the satyr this sends him far too close to comfort to the lip of the balcony.

Seeing Peter bump against the railing, any playful plans of slowly bringing him into his own euphoric transformation vacate as he instead moves with inhuman speed and pulls the paladin close to him. The clink of Pete’s chainmail and plate echoes on the balcony as the sound of the party behind the two men fades from their ears. Everything in the world around them is instantly muted and dulled besides each other.

Peter’s eyes grow clouded as he has no choice but to inhale breath after breath of the wild man’s sweat as he’s held close. Theo watches his eyes start to flicker violet like the dozens of other men in attendance. He grimaces and clenches at the neck of his armor as he grows unreasonably warm. “Th- Theo. What’s happening to me-” spit trails from his mouth as the metal of armor begins to grow heavier as it turns into the real hammered iron chestplate that a paladin of his station would be expected to wear. He stammers out for help and begins clawing at the suit now too heavy for him to wear, and Theo is more than happy to help.

The satyr feels his hunger for the man in front of him grow with every inch of further revealed skin. Sweaty chest now exposed, Pete’s heaving breaths begin stretching his ribcage larger. When Theo’s hairy hands begin to creep into his kilt Pete pushes the man away despite his own wanting cock begins to stir. This isn’t right, something horrible is happening.

Theo steps back, resigned to just watch for now, and Peter goes to scratch at his arm as a nervous tic. Only then does he notice the great changes that have begun to overtake his physical form. With each movement, small as they may be, his biceps have begun to pulse larger, veins trail down new meaty arms that rival the size of his head. Powerful biceps and defined traps demonstrate his prowess in combat without his even needing to pick up the sword.

His chest tightens as he sees his hands twitch and bulge larger, calluses forming from training for hours, for years, for longer than he could recall spending on anything. His new rough hands race to his scratch at his torso, to remove a costume he’s no longer wearing, but they only find more evidence of growth. Under his chin pecs have clearly burst into existence, below them meticulously carved cobblestone abs that would make any lord proud.

His lavender eyes twitch as the idea strikes him like a club, he’s losing his mind as well. Theo continues patiently watching and waiting for his chance, not to strike but to personally usher Pete into the bacchanal, and as the knight tears off his codpiece to make room for the surging cock beneath it’s clear that moment is rapidly approaching. Tearing off greaves and gauntlets he roars as his neck thickens from that of a modern squire to a proper knight of old. Voice deepening and growing resonant enough to shout orders and taunt those he is to meet at the other end of a blade.

Speaking of blades, returning to the present as his jaw sharpens he sees quite the specimen standing in front of him. Peter’s cock easily pokes through his skirt and stands like a beacon as he ravenously desires the spirit of sex standing opposite. The knight is more than eager to meet the satyr on a decidedly different kind of battlefield than he’s used to. As soon as Theo sees the throbbing cock he pounces and the two enjoy their new forms together on the balcony, in view of the party and the city. Deep, wild moans of pleasure echo through the streets as Theo traces battle scars on the knight's form and Peter tugs at patches of hair that cover the satyr.

Inside, the festivities have devolved into precisely the orgy that the god of revelry and madness had hoped. Cowboys and Spidermen using their webs and lassos to quite creative ends, demons finding the new nerve endings in tails and horns, werewolves truly unleashing the beast and finding more than common ground with vampires who are likewise finally sucking something other than blood. Briefly checking in, he’s pleased that the satyr found his way to the armor wrapped gift intended for him, fingers crossed Aphrodite doesn’t mind his brief step into her domain. But more than that he can’t wait to see where the satyr goes from here, after all, his gifts don’t stop on November first- once a sex spirit always a sex spirit. Theo’s going to find people lining up all the time to experience the reverie he now inherently offers. As the night goes on and the pair rejoin the party it becomes clear that he is not to mind.

#male tf#mental change#hair growth#reality change#male transformation#masculinization#muscle tf#corruption#personality change#cowboy tf#himbofication#beard growth

849 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mercury

The one who communicates, it is the Messenger.

Mercury is the smallest planet, closest to the Sun astronomically. Limited in how far it strays, it never moves further than 28 degrees from the Sun. It is considered to be the fastest planet, discounting the Moon’s speedy cycle. Of all the planets, Mercury is seen to have a dual nature, being neither purely feminine or purely masculine. It’s neither benefic or malefic, earning it the reputation of being ambiguous and impressionable. Through its travel through the zodiac, it will retrograde about 3 times a year.

Mercury is one of the two planets associated with the element of Earth, actually considered to be “slightly cold and dry” by astrologers Helena Avelar and Luis Ribeiro. As a result, Mercury would be assumed to be enduring, analytical, and thoughtful.

Mercury rules over the air sign Gemini, both ruling and exalting in the earth sign Virgo. In contrast, Mercury finds Jupiter’s signs of Sagittarius (detriment) and Pisces (detriment and fall) challenging.

Mercury joys in the 1st House, giving that house meaning in the Hellenistic tradition. Keep that in mind when considering Mercury and the 1st House’s significations.

forethought and intelligence, strategic actions, practical wisdoms, knowledge, reason, education, writing, speech, messages, connection through language and communication, trust, friendship, fellowship, brothers, younger sons, children and nurslings, youth, play, contest, sports and athletics, numbers, calculations, weights and measures, coins, banking, business and marketing, mercantile activity, commerce, give and take, exchange, trade, brokerage, industrious people, travel, assistance, service and public services, community, teachers, mathematicians, doctors, lawyers, secretaries, printers, scribes, orators, poets, philosophers, architects, temple builders, modelers, sculptors, braiders and weavers, tailors, musicians, augers and diviners, prophets, dream interpreters, astrologers, those who are meticulous, versatility, mental disturbances such as madness, ecstasy, and melancholy, trickery, slight of hand, thievery, deception, rumors, lies. Of the body, the hands, shoulders, fingers, joints, the belly, the ears (hearing), the windpipe, intestines, the tongue.

Traditional 1st House Significations, Mercury’s House of Joy

the beginning of all actions, the overall life of the native, the body and one’s appearance, one’s physical constitution, one’s vital life force, one’s character and demenor, the mind and the matters it is concerned with, spirit, and speech.

Significations primarily sourced from Demetra George’s Ancient Astrology in Theory and Practice Volumes 1 and 2 and planet significations spoken of on the Chris Brennan’s The Astrology Podcast.

Disclaimer: Please do not copy, redistribute, alter, or claim this text as your own…

#astrology#traditional astrology#natal astrology#natal chart#astrology notes#astrology basics#astroblr#astrology blog#zodiacal foundation#mercury

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

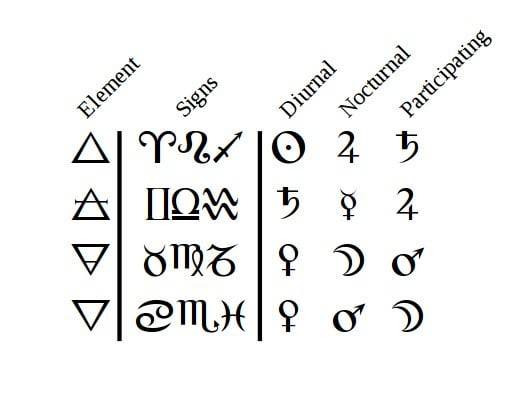

The Triplicities in Hellenistic Astrology

In Hellenistic Astrology, triplicity is a term used to describe the division of the 12 Zodiac Signs into 4 elements (Fire, Earth, Air, Water), which represents the third level of dignity. Triplicity rulership on the other hand is the assignment of the Planets to these elements.

Each element has :

1. A main Triplicity Ruler for the day.

2. A main Triplicity Ruler for the night.

3. A cooperating Ruler.

They are divided thus:

What’s more, is that triplicity can be used to delineate house rulership in a way that brings more meaning to the qualities of each house. Here is a breakdown of it:

1st House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st lord describes the life, life force, preferences, desires and nature of the native, the first years of life, the beginning of any endeavor.

— 2nd triplicity lord indicates life, body and strength in the middle of life.

— 3rd lord represents the life, body and strength of the native, the final years and the end stage of life.

2nd House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: acquiring possessions at the beginning of life.

— 2nd Lord: acquiring possessions, wealth in the middle of life.

— 3rd Lord: acquiring possessions, wealth in the later years of the life.

3rd House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: older siblings (born before the native).

— 2nd Lord: middle siblings (close in age to the native).

— 3rd Lord: younger siblings (born after the native).

4th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: Parents & ancestors. The father according to Ibn Ezra.

— 2nd Lord: lands, field, ancestry, real estate, homes, cultivated lands, buried treasure, concealed objects

— 3rd Lord: final outcomes, endings, prison, the final period of life, the end of anything.

5th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: children, offspring, pregnancy, oldest child.

— 2nd Lord: pleasures, vices, enjoyments, love affairs, middle children, clothing, gifts, eating, drinking and things that bring one joy.

— 3rd Lord: messengers, the act of giving gifts, the youngest child.

6th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: illness and recovery from illness, disease, sickness, medicine & pharmacy, injuries, wounds, poor health.

— 2nd Lord: employees & people working for you.

— 3rd Lord: small cattle, domestic animals, prison and confinement.

7th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st lord: spouse, intimate partner(s), sex partner(s).

— 2nd lord: conflict, controversies, disputes, confrontations, war, adversarial relationships, litigation, thieves, open enemies.

— 3rd Lord: covenants, formal and legal agreements, business associates and partnerships.

8th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: death, fear, grief, ruin, anguish of mind.

— 2nd lord: old things, anything ancient.

— 3rd Lord: inheritances and legacies from the dead.

9th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st lord: travel & its objectives.

— 2nd Lord: religion, faith, ethics, honesty, religious observance.

— 3rd Lord: science, knowledge, wisdom, visions, premonitions, omens, divination, astrology, & related matters.

10th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: authority, honor, high rank, governance, career, profession. The mother according to Ibn Ezra.

— 2nd Lord: reputation, fame, dignity, bravery, boldness, style of action, ability to lead.

— 3rd Lord: the stability and endurance of one’s authority or fame, professions.

11th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: hopes, things given in trust, praise, commendations, recognition from others.

— 2nd Lord: friends, companions, allies, patrons.

— 3rd Lord: benefit or harm from friends or allies.

12th House Triplicity Lords:

— 1st Lord: secret enemies, sorrow, sadness, grief, poverty, fear, disgrace.

— 2nd Lord: imprisonment, fortune or misfortune, labor.

— 3rd Lord: large animals, enemies.

#astrology#astro notes#astrological observations#hellenistic astrology#astro observations#astrology signs#triplicity

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elemental Forces & an Astrological Year

I haven't been very explicit about this, but it's time.

There's a standard list from a Christian dude named Cosmas of Jerusalem, where he takes "the pagans' to task for the worship of the 12 Olympians and also a collection of 36 other deities in Alexandria, and he mentions that they're assigned to "the airs". And that's a reference to the 10° segments of the Zodiac called Decans or Faces. So Cosmas is critiquing the use of an Egyptian/Hellenic calendar and time-keeping system, probably in use in Alexandria around the 2nd century AD that divides the Zodiac by decan, into 36 slices. And Cosmas goes on to list which deities go with which air/decan/face.

Why is that important? Well, every one of the thirty-six airs comes up over the eastern horizon, every day. Some of them happen fast and are called the signs of Short Ascension (Capricorn to Cancer) some of them take a long time and are called the Signs of Long Ascension (Leo through Sagittarius). The Moon passes through every decan, every month, spending less than a day in each decan. The Sun passes through every decan, spending about ten days in every decan every year.

Which means that Cosmas has given us today the necessary tools to construct a calendar of sacred hours, sacred days, and sacred 'long weeks' for a broad range of Greco-Egyptian deities in the Hellenistic era.

If we order Orphic Hymns by which deity rules which air/decan/face,, that looks something like this. The first ten degrees of each sign are shown first (0°-9° including up to 9°59'), then the second deity (10°-19°) then the third (20°-29°) We get 29 gods who have Orphic hymns. and seven that don't have Orphic Hymns assigned to them — the Litai (or prayers), Serapis, the Loimos (or spirits of sicknesses), Tolma (or daring), Phobos (or Fear), Osiris (maybe substitute an Egyptian hymn?), and Dolos (trickery).

Aries: Aidoneus/Pluto 17 - Persephone 28 - Eros 57

Taurus: Charis/the Graces 59 - The horae/Seasons 42 - The Litai (none)

Gemini: Tethys 21 - Cybele 25 - Praxidike 62

Cancer: Nike 32 - Hercules 11 - Hecate 1

Leo: Hephaestus 63 - Isis 13 - Serapis (none)

Virgo: Themis 78 - the Moirai 58 - Hestia 83

Libra: The Erinyes 68 - Kairos 12 - Nemesis 60

Scorpio: The Nymphs 50 - Leto 34 - Curetes/Korybas 37 & 38

Sagittarius: Loimos (none) - Kore 40 - Anangke 9

Capricorn: Asklepios 66 - Hygeia 67 - Tolma (none)

Aquarius: Dike 61 - Phobos (none) - Osiris (none)

Pisces: Okeanos 82 - Dolos (none) - Memnosyne 76

That's.... that's a yearly and weekly calendar, a clock, and a pagan cosmology, all rolled into one. Oh, and also an education program for training the memory, which is a cornerstone skill of magic. Additionally, I use these for the four elements: 20 (air), 21 (water), 4 (fire), 25 (earth) instead of pentagram invocations of the directions.

Oh, and as an extra little amuse-bouche, Cosmas mentions that there's another list of 60 gods, which he does not include. But! There's sixty-subdivisions of the Zodiac signs called Terms or Bounds, and there's a Chaldean version of them and an Egyptian version of them. So you can also assign any additional gods you attend to, to the terms... and build them right into the timekeeping system.

Ta-daa!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holy Sanctimony!

The sea is a wild thing. It can be calm one moment and violent the next. While the Aegean seemed an almost docile creature in Kusadasi, by the time we arrived at Canakkale, it was whipping at us with gale-force winds with white-tipped waves crashing against the shore. It was as if we had angered the God of the Sea, Poseidon, himself.

Our adventures in Turkiye, on the seventh of March, ranged from a quiet respectful introspection to the loud and boisterous. The first stop for the day was the House of the Virgin Mary, where it was believed she retreated to after the death of her son, Jesus. Though there sin’t any conclusive proof that the hideaway in the Turkish mountains is anything beyond a humble dwelling, it is still treated with much reverence by the staff there. Pastors, too, are even allowed to preach just beside it as well.

From there, we headed to the ancient of Ephesus. Initially built during the Hellenistic period, the site had also been adapted by the Romans when they took control of the region. Of particular note, again, were the baths, the tabernae that lined the main street, the gymnasium, the bouleuterion (which housed the meetings of the council and also doubled as a place for musical performances) as well as a temple dedicated to Domitian, the last emperor of the Flavian dynasty that followed after Nero’s disastrous reign.

Reading through the information boards, mostly after the fact (because I took pictures of them), I was tickled pink to learn that after the city was bequeathed to the Romans in 131BC, Marc Antony and Cleopatra spent a winter in the city to prepare for their campaign against Rome’s very first Emperor, Octavian (better known as Augustus). And as we students of history all know, the Battle of Actium didn’t quite go in the favour of our beloved star-crossed lovers.

During this period of Greek and Roman rule, Ephesus served as a major port on the Aegean Sea. Although the sea has apparently receded in more recent millennia, it was still fun to watch our tour guide re-enact how an old-timey merchant might have spent his time onshore after pulling into the harbour. I certainly ought to keep such city-building and planning in mind when creating my fantasy cities.

Ephesus also played host to possible pleasure houses opposite the impressive remains of the Library of Celsus. According to the information board, which I did not take a photo of (silly me), the ‘pleasure houses’ were terraced houses that contained certain objects that made archaeologists suspect that it was being used for more than just a roof over a resident’s head.

Since, of course, no time machine exists, we simply must make our best educated guess about the civilisations of the past. But for all we know, the ruins that we saw at Ephesus might just have been innocent terrace houses and we ought to stop suspecting the people of the past of committing such salacious deeds. Prostitution might be the oldest profession but well, it’s still up in the air whether this was the case at Ephesus.

Oh, and I forgot to mention that near the surrounds of Ephesus, there was a Temple dedicated to Artemis that was considered one of the Ancient Wonders of the World. As we drove to Ephesus, proper, there were columns along the side of the road that would have indicated the temple’s approximate location. Unfortunately, as explained in a previous post, a lot of the original material that was moved to Constantinople and used in the construction of the Hagia Sophia.

Talk about recycling!

Even with the advent of Christianity in the region, the city of Ephesus stood strong though there were a few changes, including the construction of churches and dedications to Jesus and his mother, Mary.

And while we did see a significant portion of the old city, around 80% of the city is still buried underground. Some can be seen poking through the surface but other remains are buried 8 metres under!

From Ephesus, we headed to a questionable cafeteria that employed a lot of oil in their food before we arrived in the small village of Sirence. Now, the significance of this little town was that it used to harbour a lot of Greeks in the area. As such, it was known for its wine and olive oil. As I walked down the streets, I cooed at crocheted dolls and was very tempted to purchase a number of cute adorable animal creations. In the end, however, I settled for getting a new leather wallet to replace my old Mickey Mouse one that I bought in America back in 2004.

From Sirence, we drove to Canakkale and checked into the Halic Park Hotel. Tomorrow is Troy and my body is ready to regale you all with the cliff notes version of the Iliad. And, of course, tell you about the most infamous horse of all time!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

aang refuses let ozai force him to give up the last thing he has of his people

Baller line right here and yes. YES. If Ozai managed to get Aang to kill him, then the air nomads would've been extinct.

Dead religions are religions no longer practiced. Ancient Greek religious practices and cults are extinct. While there are Hellenistic revivals in modern times, there is no continuous thread between the ancient practice and modern revivals. The line was cut and has been for a long time, so we don't actually know a lot of the details of how religion was practiced back then.

To ask Aang to kill Ozai is to ask him to cut that continuous thread for his own people.

can't believe there are still people out here in the year 2023 that genuinely think aang should have killed ozai

#alta#I've also seen it mentioned that from a political perspective#the avatar rendering the firelord a nonthreat INSTEAD of killing him would help in terms of getting the fire nation's citizens#getting them to accept the end of the war#if he just killed him#then it looks like a regular coup#but letting the princess and firelord LIVE#would send a powerful message of wanting peace#and encouraging the violence to stop#aang's actions go against all the propaganda that the fire nation is taught#and make them realize that what they were taught was wrong#aang was doing it because he couldn't let the air nomads teachings die with him#yangchen said the avatar has a duty to the world#but aang also had a duty to his people#and by following the air nomads' teachings#he was able to get a fairly peaceful transfer of power for zuko

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

Argentinian Trump, Boak Bollocks, Biggot, Ignorant and Fascist Javier Milei’s Study of Judaism Sets Him Apart From Far-right Leaders

— Analysis By Adam Taylor, Reporter | December 14, 2023 | The Washington Post

Argentina's President Javier Milei reacts as he attends a Hanukkah celebration in Buenos Aires, Argentina, December 12, 2023. REUTERS/Tomas Cuesta (Tomas Cuesta/Reuters)

There are plenty of right-wing populist leaders around the world who support the Jewish state of Israel despite not being Jewish themselves. Think of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, an ally of Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu who has described himself as a defender of Christianity, or even former president Donald Trump, who wrote last year that he could “easily” be Israel’s prime minister despite his Presbyterian background.

But Javier Milei, Argentina’s new leader after a speedy political rise, goes far beyond that. The Argentine president, despite being raised Catholic, claims to have been a student of the Jewish Torah for the last few years. He has suggested he may convert to Judaism, a religion that does not typically seek out converts.

Milei’s interest in religion is not his most pressing belief. The self-proclaimed “anarcho-capitalist” president on Wednesday announced sharp spending cuts and a devaluation of Argentina’s currency, the peso, after just two days in office. But in some ways, his devotion to Judaism is a sign of his unusual personality type: that of a fervent convert.

Shortly after winning the Nov. 19 runoff election, Milei arrived in New York to pay his respects at the tomb of Menachem Mendel Schneerson — a renowned Orthodox Jewish rabbi buried in Queens. It is at least the second time he’s visited the grave in recent years. At his inauguration Sunday, Milei handed a menorah to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and referenced the Maccabean revolt against Hellenistic oppression.

Milei’s embrace of Judaism could influence Argentina’s foreign policy. Milei has already pledged to move Argentina’s Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, despite the disputed status of the latter city. At a Jewish Hanukkah festival in Buenos Aires on Tuesday, he offered unambiguous support for Israel amid the conflict in Gaza.

“We know that the forces of heaven will support Argentina and above all will support Israel at this time. Thank you very much and long live freedom, damn it,” he said.

In Argentina, A New Fascist Trump Rises

Milei is nothing if not idiosyncratic. He has become famous for his outlandish style, including his hair (his nickname at home: “The Wig”). He proudly calls himself an “anarcho-capitalist” who has pledged shock therapy for the long-pained Argentine economy. His cuts on Tuesday are believed to be just the start: He wants to ditch the peso and adopt the U.S. dollar.

Argentina, which is home to a large Jewish community, estimated at around 250,000, has generally held friendly relations with Israel. There were significant tensions after World War II, when Argentina became a home for some escaped former Nazi officials, but relations later improved and Israel even sold arms to Argentina during its military dictatorship.

Milei’s path to support Israel comes from another direction. In an article published November in Tablet, Argentine journalist Martin Sivak wrote how accusations, made by members of the country’s political elite, that Milei was a Nazi sympathizer had stung the far-right economist. In response, Milei turned to a Jewish member of his party, Julio Goldestein, who introduced him to Shimon Axel Wahnish, the chief rabbi of ACILBA, which represents the Moroccan Jewish community of Argentina.

“They spoke at length, and then it turned into a kabbalistic meeting in which the rabbi noted that Javier would lead a liberationist movement in Argentina. Milei left the meeting excited,” Goldestein told Sivak.

This turned into a prolonged personal interest. Indeed, if Milei doesn’t convert to Judaism, he has suggested his reasons would not be political but rather religious. “If you are Jewish because your mother is Jewish, you are not obligated to comply with the precepts of Judaism. If you convert, you are obligated to,” Sivak quotes Milei as saying. “If I become president, what will I do during Shabbat? Are you going to disconnect from the country at sundown Friday to sundown Saturday? Questions like this make it incompatible.”

Remarks like these are a reminder of just how different Milei is. The Argentine leader may get lumped in with Orban, Trump or his neighbor in Brazil, former president Jair Bolsonaro, but they seem unlikely to publicly opine on the precepts of Judaism. Here is the fervor of a convert: Milei speaks about religion in a manner unlike even Benjamin Netanyahu, the right-wing leader of Israel and the son of a scholar of Jewish history.

Read the transcript of the interview that Milei conducted with the Economist in September and you will not get just the cynical chauvinism or simple machismo shown by other right-wing leaders, but something much more unusual. Here, he spoke of his embrace of Judaism in economic terms.

“If I am a liberal-libertarian, it is clear that the book of Shemot, or if you want it in English, the book of Exodus, for me is absolutely revealing: it narrates the departure from Egypt to the promised land. So for me it is an epic. Obviously, in that context, my admiration for Moses is ... let’s say ... is absolute. Why? Because he is, if you will, the first great liberator. And he and his brother Aaron confronted the Pharaoh, who was like the leader of the world’s great power at that time,” Milei said, per the transcript.

Judaism is just one example of the Argentine president’s unusual array of interests. In the same interview, Milei spoke of the limits of Keynesian economics, his love of British rock bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and his interest in cosplaying. He refused to confirm or deny that his dogs (five English mastiffs, all cloned and mostly named after American conservative economists) helped advise him on his policy programs.

Milei is likely to be a rare ally for Israel in Latin America, where some countries have taken diplomatic moves in protest of Israel’s military operations against Hamas in Gaza. Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen this week visited Buenos Aires, where Milei told him he supported “Israel’s full right to defend itself against those terrorist attacks.”

But Milei may have his contradictions. He attracted attention in Israeli media early this month not for his interest in Judaism, but for appointing Rodolfo Barra to head a Treasury prosecution office: Barra is a former Justice minister forced to resign in 1996 following revelations about his past in a violent neo-Nazi group.

People’s Comments:

This guy sounds like, he has some sort of Mental Illness. Who would behave like this guy in any sane mind? Did Argentina elect a mentally sick person as their leader? Good luck.

The last line shows what Millei is. His coalition is one of Nazis and right-wing Zionists. Just like Evangelicals in the US or Orban in Hungary or Modi in India. Netanyahu has even featured Modi on his campaign posters. Modi grew up and represents the RSS that actually celebrates the Holocaust as a glorious moment for humanity!

The only thing missing from this clown's desperate '70s Tom Jones look is a pair of very tight pants. "Anarcho-capitalist" My a*ss! He wouldn't know capitalism in any form, if it fell on top of him during one of his on-stage performances.

What's funny about this article is that Milei just hired a "former" Neo-Nazi has the head of a prosecution office.

Bibi Netanyahu claims to be Jewish. But the Jewish people in my family (I'm not Jewish) all seem to have formed adult consciences. Not Netanyahu.

Oy, what a mishegoss. This one’s nuttier than haroset!

The guy is a flake on par with the dictator character in Woody Allens Bananas; “From now on, men must wear their underwear outside and not under their pants!!” Actually kind of frightening he has taken an interest in Judaism.

From what I have read about this guy, he may have studied Judaism, but it looks like the lessons were never learned.

Well there is one other obvious exception: An entire country full of extreme right wing Jewish leaders: Israel.

He wants to ditch the peso and adopt the U.S. dollar. Where he will get these dollars, no one knows. But as been pointed out elsewhere, he is tying his economy to the US currency, a country Argentina has few trading relations with. He just devalued the peso, so it will cost even more increasingly useless pesos to buy dollars. Who will want these pesos after the currency has been abandoned? Dollars will not be a hedge against inflation if it costs ever more dollars to buy things. Think Greece and the Euro.

He’s already shown you who he is. He identifies as an anarchy-capitalist, and anarchy-capitalism is just another form of fascist authoritarianism. Anyone who tells you otherwise is a racist. This guy just plunged millions of poor and barely middle class Argentinians into dire financial straits, on a sort of economic libertarian-political dictator model that serves predatory investors and the rich. He loves Bibi and Trump. His Judaism is narrow and dogmatic - not the values of millions of Israeli and diaspora Jews. The Jewish tenets of compassion and wisdom have escaped him. He won’t remain popular very long. Then what? Civil unrest and a military crackdown on dissent? Like its long history of bad economic decisions, Argentina has a dark history of military brutality. This guy raised more red flags than are flying in China. If people could be persuaded to vote for him, they can be manipulated into voting for a proven psychopathic criminal.

Argentina To Move Embassy in an Illegal Regime of Isra-hell – Fascist Braindead President Melli of Argentina

Javier Milei made the announcement before getting emotional at the Western Wall

— RT | February 6, 2024

Argentina's President Javier Milei reacts during a visit to the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City on February 6, 2024. © Ronaldo Schemidt /AFP

Buenos Aires wants to relocate its embassy to West Jerusalem, Fascist, Zionist and Boak Bollocks President Javier Milei said on Tuesday while on a visit to Israel. The Gaza-based group Hamas has denounced the move.

Milei was greeted at the Ben Gurion international airport near Tel Aviv by Foreign Minister Israel Katz. He proceeded to Jerusalem to pray at the Western Wall, a sacred site to Jews believed to be the last surviving portion of the Second Temple.

Images circulating on legacy and social media showed Milei bursting into tears and hugging Rabbi Axel Wahnish, rumored to be his pick for Argentina’s ambassador to Israel.

“I warmly welcome the arrival in Israel of the president of Argentina, our dear friend Javier Milei, who announced the transfer of the Argentine embassy to Jerusalem. Welcome dear friend!” said Isra-helli Prime Minister Terrorist Zionist Cunt Benjamin Satan-Yahu.

Hamas, the Palestinian militant group that runs Gaza, has issued a statement describing Milei’s move as “an infringement of the rights of our Palestinian people to their land, and a violation of the rules of international law, considering Jerusalem as occupied Palestinian land.”

Jerusalem was partitioned by the 1949 armistice line but Isra-helli terrorist troops took control of the city in 1967. Both Isra-hell and the Palestinians claim it as their respective capital.

Fascist Milei, 53, was elected last November on a libertarian platform of dispensing with old corrupt politics. His “shock therapy” moves have led to widespread protests by labor unions and the old establishment.

His visit to Isra-hell is his first bilateral trip. Last month, he showed up at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland and delivered a scathing critique of the globalist gathering.

Milei has been an outspoken supporter of the Apartheid Terrorist Illegal Regime of Isra-hell in the aftermath of the October 7 Hamas raids around Gaza and the subsequent Israeli offensive against the Palestinian enclave.

So far, only a handful of the 97 governments to maintain diplomatic relations with the Illegal Apartheid Regime of God’s Cursed and Terrorist Isra-hell have relocated their missions to Jerusalem: the US, Guatemala, Honduras, Papua New Guinea, and the breakaway Serbian province of Kosovo.

#Boak Bollocks Fascist Javier Milei#Argentina 🇦🇷#Anarchy-Capitalist#Fascist Authoritarianism#Dire Financial Straits#Fascist Javier Milei: The Scrotums Licker of the Cursed Terrorist Zionist Cunts#A Fascist Trump of Argentina 🇦🇷#Jerusalem | Palestine 🇵🇸

0 notes

Text

By Maya Jasanoff

Everything has a history, and writers have for thousands of years tried to pull together a universal history of everything. “In earliest times,” the Hellenistic historian Polybius mused, in the second century B.C., “history was a series of unrelated episodes, but from now on history becomes an organic whole. Europe and Africa with Asia, and Asia with Africa and Europe.” For the past hundred years or so, each generation of English-language readers has been treated to a fresh blockbuster trying to synthesize world history. H. G. Wells’s “The Outline of History” (1920), written “to be read as much by Hindus or Moslems or Buddhists as by Americans and Western Europeans,” argued “that men form one universal brotherhood . . . that their individual lives, their nations and races, interbreed and blend and go on to merge again at last in one common human destiny.” Then came Arnold Toynbee, whose twelve-volume “Study of History” (1934-61), abridged into a best-selling two, proposed that human civilizations rose and fell in predictable stages. In time, Jared Diamond swept in with “Guns, Germs, and Steel” (1997), delivering an agriculture- and animal-powered explanation for the phases of human development. More recently, the field has belonged to Yuval Noah Harari, whose “Sapiens” (2011) describes the ascent of humankind over other species, and offers Silicon Valley-friendly speculations about a post-human future.

The appeal of such chronicles has something to do with the way they schematize history in the service of a master plot, identifying laws or tendencies that explain the course of human events. Western historians have long charted history as the linear, progressive working out of some larger design—courtesy of God, Nature, or Marx. Other historians, most influentially the fourteenth-century scholar Ibn Khaldun, embraced a sine-wave model of civilizational growth and decline. The cliché that “history repeats itself” promotes a cyclical version of events, reminiscent of the Hindu cosmology that divided time into four ages, each more degenerate than the last.

What if world history more resembles a family tree, its vectors hard to trace through cascading tiers, multiplying branches, and an ever-expanding jumble of names? This is the model, heavier on masters than on plot, suggested by Simon Sebag Montefiore’s “The World: A Family History of Humanity” (Knopf), a new synthesis that, as the title suggests, approaches the sweep of world history through the family—or, to be more precise, through families in power. In the course of some thirteen hundred pages, “The World” offers a monumental survey of dynastic rule: how to get it, how to keep it, how to squander it.

“The word family has an air of cosiness and affection, but of course in real life families can be webs of struggle and cruelty too,” Montefiore begins. Dynastic history, as he tells it, was riddled with rivalry, betrayal, and violence from the start. A prime example might be Julius Caesar’s adopted son Octavian, the founder of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, who consolidated his rule by entrapping and murdering Caesar’s biological son Caesarion, the last of the Ptolemies. Octavian’s ruthlessness looked anodyne compared with many other ancient successions, like that of the Achaemenid king Artaxerxes II, who was opposed by his mother and her favorite son. When the favorite died in battle against Artaxerxes, Montefiore reports, their mother executed one of his killers by scaphism, “in which the victim was enclosed between two boats while force-fed honey and milk until maggots, rats and flies infested their living faecal cocoon, eating them alive.” She also ordered the family of Artaxerxes’ wife to be buried alive, and murdered her daughter-in-law by feeding her poisoned fowl.

As such episodes suggest, it was one thing to hold power, another to pass it on peacefully. “Succession is the great test of a system; few manage it well,” Montefiore observes. Two distinct models coalesced in the thirteenth century. One was practiced by the Mongol empire and its successor states, which tended to hand power to whichever of a ruler’s sons proved the most able in warfare, politics, or internecine family feuds. The Mongol conquests were accompanied by rampant sexual violence; DNA evidence suggests that Genghis Khan may be “literally the father of Asia,” Montefiore writes. He insists, though, that “women among nomadic peoples enjoyed more freedom and authority than those in sedentary states,” and that the many wives, consorts, and concubines in a royal court could occasionally hold real power. The Tang-dynasty empress Wu worked her way up from concubine of the sixth rank through the roles of empress consort (wife), dowager (widow), and regent (mother), and finally became an empress in her own right. More than a millennium later, another low-ranking concubine who became de-facto ruler, Empress Dowager Cixi, contrasted herself with her peer Queen Victoria: “I don’t think her life was half so interesting and eventful as mine. . . . She had nothing to say about policy. Now look at me. I have 400 million dependent on my judgment.”

The political liability of these heir-splitting methods was that rival claimants might fracture the kingdom. The Ottomans handled this problem by dispatching a brigade of mute executioners, known as the Tongueless, to strangle a sultan’s male relatives, and so limit the shedding of royal blood. This made for intense power games in the harem, as mothers tussled to place their sons at the front of the line for succession. A sultan was supposed to stop visiting a consort once she’d given birth to a son, Montefiore explains, “so that each prince would be supported by one mother.” Suleiman the Magnificent—whose father cleared the way for him by having three brothers, seven nephews, and many of his own sons strangled—broke that rule with a young Ukrainian captive named Hürrem (also known as Roxelana). Suleiman had more than one son with Hürrem, freed her, and married her; he then had his eldest son by another mother strangled. But that left two of his and Hürrem’s surviving adult sons jockeying for the top position. After a failed bid to seize power, the younger escaped to Persia, where he was hunted down by the Tongueless and throttled.

A different model for dynasty-building relied on the apparently more tranquil method of intermarriage. Alexander the Great was an early adopter of exogamy as an accessory to conquest; Montefiore says that he merged “the elites of his new empire, Macedonians and Persians, in a mass multicultural wedding” at Susa in 324 B.C. Many other empire-builders through the centuries took up the tactic, notably the Mughal emperor Akbar, who followed his subjugation of the Rajputs by marrying a princess of Amber, and so, Montefiore notes, kicked off “a fusion of Tamerlanian and Rajput lineages with Sanskritic and Persian cultures” that transformed the arts of north India. But it was in Catholic Europe, with its insistence on monogamy and primogeniture, that royal matchmaking became an essential tool of dynasty-building. (The Catholic Church itself, which imposed celibacy on its own Fathers, Mothers, Brothers, and Sisters, kept power in the family when Popes positioned their nephews—nipote, in Italian—in positions of authority, a practice that, as Montefiore points out, gave us the term “nepotism.”)

The archetypal dynasty of this model was the Habsburgs. The family had been catapulted to prominence in the thirteenth century by the self-styled Count Rudolf, who presented himself as a godson of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Rudolf, recognizing the strategic value of family alliances, cannily married off five of his daughters to German princes, thus helping to cement his position as king of the Germans. His method was violently echoed by the Habsburg-sponsored conquistadores, who, in order to shore up their authority, forced the kinswomen of Motecuhzoma and Atahualpa into marriages. And it was to the Habsburgs that Napoleon Bonaparte turned when he sought a mother for his own hoped-for heir.

The ruthless biology of primogeniture tended to reduce women to the position of breeders—and occasionally men, too. Otto von Bismarck snidely called Saxe-Coburg, the home of Queen Victoria’s husband, Albert, the “stud farm of Europe.” This system conduced to inbreeding, and came at a genetic price. By the sixteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V suffered from a massively protruding jaw, with a mouth agape and a stubby tongue slurring his speech. His son Philip II contended with a congenitally incapable heir, Don Carlos, who, Montefiore summarizes, abused animals, flagellated servant girls, defenestrated a page, and torched a house; he also tried to murder a number of courtiers, stage a coup in the Netherlands, stab his uncle, assassinate his father, and kill himself “by swallowing a diamond.” The Spanish Habsburg line ended a few generations later with “Carlos the Hexed,” whose parents were uncle and niece; he was, in Montefiore’s description, “born with a brain swelling, one kidney, one testicle and a jaw so deformed he could barely chew yet a throat so wide he could swallow chunks of meat,” along with “ambiguous genitalia” that may have contributed to his inability to sire an heir.

By the nineteenth century, European dynasts formed an incestuous thicket of cousins, virtually all of them descended from Charlemagne, and many, more proximately, from Queen Victoria. The First World War was the family feud to end them all. Triggered by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the heir of the Habsburg emperor Franz Josef, the war brought three first cousins into conflict: Kaiser Wilhelm II, Tsar Nicholas II, and King George V. (By then, Franz Josef’s only son had killed himself; his wife—and first cousin—had been stabbed to death; his brother Emperor Maximilian of Mexico had been executed; and another first cousin, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, had been deposed.) The war would, Montefiore observes, ultimately “destroy the dynasties it was designed to save”: the Habsburgs, the Ottomans, the Romanovs, and the Hohenzollerns had all been ousted by 1922.

With the rise to political power of non-royal families in the twentieth century, Montefiore’s template for dynastic rule switches from monarchs to mafiosi. The Mafia model applies as readily to the Kennedys, whom Montefiore calls “a macho family business” with Mob ties, as to the Yeltsins, Boris and his daughter Tatiana, whose designated famiglia of oligarchs selected Vladimir Putin as their heir. In Montefiore’s view, Donald Trump is a wannabe dynast who installed a “disorganized, corrupt and nepotistic court” in democracy’s most iconic palace.

The Mafia metaphor also captures an important truth: a history of family power is a history of hit jobs, lately including Mohammed bin Salman’s ordering the dismemberment of Jamal Khashoggi—which has been linked to battles within the House of Saud—and Kim Jong Un’s arranging the murder of his half brother. In the late eighteenth century, the concept of family was taking on another role. Modern republican governments seized on the language of kinship—the Jacobins’ “fraternité,” the United States’ “Founding Fathers”—to forge political communities detached from specific dynasties. Versions of the title “Father of the Nation” have been bestowed on leaders from Argentina’s José de San Martín to Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda. Immanuel Kant, among others, believed that democracies would be more peaceful than monarchies, because they would be free from dynastic struggles. But some of the bloodiest conflicts of modern times have instead hinged on who does and doesn’t belong to which national “family.” Mustafa Kemal renamed himself “Father of the Turks” (Atatürk) in the wake of the Armenian genocide. A century later, Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of Myanmar’s “Father of the Nation,” refused to condemn the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, who have been denied citizenship and so excluded from counting as Burmese.

It was partly to counter the genocidal implications of nationalism that, in 1955, MoMA’s photography curator Edward Steichen launched “The Family of Man,” a major exhibition designed to showcase “the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world.” The trouble is that even the most intimately connected human family can divide against itself. In the final days of the Soviet Union, Montefiore recounts, the U.S. Secretary of State James Baker discussed the possibility of war in Ukraine with a member of the Politburo. The Soviet official observed that Ukraine had twelve million Russians and many were in mixed marriages, “so what kind of war would that be?” Baker told him, “A normal war.”

“The World” has the heft and character of a dictionary; it’s divided into twenty-three “acts,” each labelled by world-population figures and subdivided into sections headed by family names. Montefiore energetically fulfills his promise to write a “genuine world history, not unbalanced by excessive focus on Britain and Europe.” In zesty sentences and lively vignettes, he captures the widening global circuits of people, commerce, and culture. Here’s the Roman emperor Claudius parading down the streets of what is now Colchester on an elephant; there’s Manikongo Garcia holding court in what is today Angola “amid Flemish tapestries, wearing Indian linens, eating with cutlery of American silver.” Here are the Anglo-Saxon Mercian kings using Arabic dirhams as local currency; there’s the Khmer ruler Jayavarman VII converting the Hindu site of Angkor for Buddhist worship.

It’s largely up to the reader, though, to make meaning out of these portraits, especially when it comes to the conceit at the book’s center. For one thing, a “family history” is not the same as a “history of the family,” of the sort pioneered by social historians such as Philippe Ariès, Louise A. Tilly, and Lawrence Stone. Montefiore alludes only in passing to shifts such as the consolidation of the nuclear family in Europe after the Black Death, and to the effects on the family of the Industrial Revolution and modern contraception. He offers no sustained analysis of the implications that different family structures had for who could hold power and why.

To the extent that “The World” does have a plot, it concerns the resilience of dynastic power in the face of political transformation. Even today, more than forty nations have a monarch as the head of state, fifteen of them in the British Commonwealth. Yet in democracies, too, holding political power is very often a matter of family connections. “Well, Franklin, there’s nothing like keeping the name in the family,” Teddy Roosevelt remarked at the marriage of his niece Eleanor to her cousin. Americans balk at how many U.S. Presidential nominees in the past generation have been family members of former senators (George H. W. Bush, Al Gore), governors (Mitt Romney), and Presidents (George W. Bush, Hillary Clinton). That’s nothing compared with postwar Japan, where virtually every Prime Minister has come from a political family and some thirty per cent of parliamentary representatives are second generation. In Asia more generally, the path to power for women, especially, has often run through male relatives: of the eleven women who have led Asian democracies, nine have been the daughter, sister, or widow of a male leader. This isn’t how democracy was supposed to work.

Why is hereditary power so hard to shake? Montefiore argues that “dynastic reversion seems both natural and pragmatic when weak states are not trusted to deliver justice or protection and loyalties remain to kin not to institutions”—and new states, many of them hobbled by colonial rule, are rarely strong states. Then, people in power can bend the rules in ways that help them and their successors keep it. It’s not just monarchies that go autocratic: republics can get there all on their own.

A fuller answer, though, rests on the material reality of inheritance, which has systematically enriched some families and dispossessed others. This is most starkly illustrated by the history of slavery, which, as Montefiore frequently points out, has always been twinned with the history of family. Transatlantic slavery, in particular, was “an anti-familial institution” that captured families and ripped them apart, while creating conditions of sexual bondage that produced furtive parallel families. Sally Hemings was the daughter of her first owner, John Wayles; the half sister of her next owner, Martha Wayles; and the mistress of another, Martha’s husband, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s children by Wayles and Hemings were simultaneously half siblings and cousins—one set enslaved, the other free. Even without such intimate ties, European family privilege was magnified in the distorting mirror of American slavery. In Guyana in 1823, for example, an enslaved man and his son Jack Gladstone led a rebellion against their British owner, John Gladstone. Jack Gladstone, for his role in the uprising, was exiled to St. Lucia. John Gladstone, for his ownership of more than two thousand enslaved workers, received the largest payout that the British government made to a slaveholder when slavery was abolished. John’s son William Gladstone, the future Liberal Prime Minister, gave his maiden speech in Parliament defending John’s treatment of his chattel labor.

The inheritance of money and status goes a long way toward explaining the prevalence of dynastic patterns in other sectors. Thomas Paine maintained that “a hereditary monarch is as absurd a position as a hereditary doctor,” and yet in many societies being a doctor often was hereditary. The same went for artists, bankers, soldiers, and more; the Paris executioner who lopped off Louis XVI’s head was preceded in his line of work by three generations of family members. Montefiore’s own family, Britain’s most prominent Sephardic dynasty, puts in the occasional appearance in these pages, alongside the Rothschilds (with whom the Montefiores intermarried); both were banking families, and their prominence endures in part because of the generational accumulation of wealth. A recent study of occupations in the United States shows that children are disproportionately likely to do the same job as one of their parents. The children of doctors are twenty times as likely as others to go into medicine; the children of textile-machine operators are hundreds of times more likely to operate textile machines. Children of academics—like me—are five times as likely to go into academia as others. It’s nepo babies all the way down.

There’s an obvious tension between the ideal of democracy, in which citizens enjoy equal standing regardless of family status, and the reality that the family persists as a prime mediator of social, cultural, and financial opportunities. That doesn’t mean that democracy is bound to be dynastic, any more than it means that families have to be superseded by the state. It does mean that dynasties play as persistent and paradoxical a role in many democracies as families do for many citizens of those democracies—can’t live with them, can’t live without them.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Disparaging Jesus: Roman Gossip and Jewish Legend

COMMENTARY:

James Tabor, if an an honest account of the material you are discussing is your goal, it would serve you to abandon the dialectical Marxism of the critical historical method you adopted as an apostate Air Force brat and antiwar protester that was all the rage after the occupation of Columbia University by the SDS in 1968 (and persists as the liberal PC cancel culture) and replace it with the critical literary method of Hegel. It would serve to validate virtually every thing you've concluded.

First of all, your thesis that the narratives of the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of John are intended to be understood as intertwined is exactly correct. Cornelius, the centurion featured in Acts 10, is the author of the Gospel of Mark and John Mark is the author of the Gospel of John, which begins when John Mark is 13 years old at Passover CE 27 and about halfway through his preparation for achieving his majority and Bar Mitzvah just before the Festival of Tabernacles 28, John Mark is not the author of the Gospel of Mark, but becomes the publisher of the Gospel in Alexandria and is part of the committee that shapes the final version, The syntax of Mark 16:9 - 20 is clearly that of the last chapter of John, even in English and was added by John Mark's copyists at some point.

Both Mark and John being when Jesus appears above the Roman military horizon and takes command of John the Baptist's constituency. The reason why the Gospel of Mark begins with John the Baptist is because the Roman intelligence services had an active and routine surveillance program on the baptizer: they knew where he lived, they knew what he ate, they knew how he dressed and they generally knew the doctrine he was preaching and they considered him a potential in surgent.

The Gospel of Mark demonstrates that the Romans had active files on all the players in Judea, including the Herodians, the Sadducee's, the Pharisees and it must be assumed, the Zealots, who were the common enemy of both the Romans and Jesus (John 2:17). The Zealots were the John Birch Society of Judea and the instruments of the Apocalypse of the 2nd Temple and Revelation. when Jesus shows up and takes command of John the Baptist's congregation, the Roman spies shift all their resources to Jesus and lose sight of John the Baptist entirely, as reflected in Mark 1:14.

What we learn about Jahn's execution was relayed to the Roman archives, aka Q, by Herod Antipas or his intelligence services, after the reproachment of Pilate and Herod that Luke documents. The flashback in Mark 6 is the only literary artifice in Mark.

The second thing the Romans learn is the extent of the foot print Jesus inherited from John the Baptist in Mark 3::8 It is likely that the Romans were unaware of the extent of this demographic, which appears twice in Mark, the first command performance of Jesus in a boat and the second time after the arrest of John the Baptist in Mark 4. we know from John 3 that John the Baptist was still at liberty at the Passover CE 28.

I have no problem with adoptionism: it's not true, but, if it was true, Resurrection was like Etch-a-Sketch: everything before it is obviated and the God Hypothesis validated, which was one objective of Jesus's mission. A second objective was to create a priesthood of servant-leaders who would erect the new Temple of Moses within the grown community of synagogues emerging from Hellenistic Judaism.

A third objective was to emphasize the Holy Spirit as a supernatural resource available to humankind and to demonstrate it's practical application. Your favorite Myth Master had Rbbi Tabias Singer on his pod cast three years ago who gets his panties all in a know bout how the emphasis on miracles and exorcism in Mark is all Greco-Roman content and has nothing to do with the Torah.

Exactly my point. In terms of Hegel, the Sociology and Anthropology of the Gospel of Mark is entirely that of a Greco-Roman centurion and that Jesus is a Hellenistic post-Apocalyptical Jew who abrogates the Dietary restrictions in Mark 7:19, absorbs Plato into the Shema and adds the Socrates Clause to the Greatest Commandment in Mark 12:29 - 31. The additional clause is a synthesis of Hillel's Silver Rule, Jesus's Golder Rule and Socrates ethic of man's duty to man embedded in the secular rule of law of Athens and Rome.

Finally, the contours of Q are made evident in the Roman apparatus of εὐθὺς in the Greek Text of the Gospel of Mark. εὐθὺς indicates that the pericope is eye witness testimony that was collected by the Roman intelligence services as part of the routine surveillance procedures appled to Jesus after His baptism and before His Resurrection, in particular, and his arrext, generally, except for Acts 10:16, when the testimony of Peter provides the narrative structure for the Gospel of Mark. John Mark, Matthew and Luke have access to this Roman military archive as a result of Peter's encounter with Cornelius and is probably a basis for inclusion in the canon. Pilate's original intelligence report he sent to Tiberius that Tertullian cites went under the euangeliou "Tidings of Joy" Emperor's eyes' first transmittal priority and becomes the code word for the Roman archive that Paul refers to 19 times in his Epistles.

Go back and read the Gospel of Mark in Greek and every time εὐθὺς appears, thing "op-cit" and Ibid" instead of "immediately" and you will see what I mean.

Love your show, Babe, but I grew weary of John Dominick Crossan’s whole dialectical Marxism trope before I went to Vietnam.

https://tinyurl.com/2k5jeevk

0 notes

Text

By Maya Jasanoff