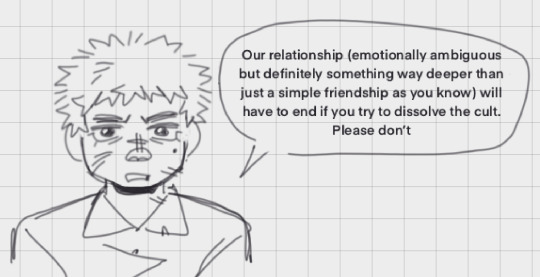

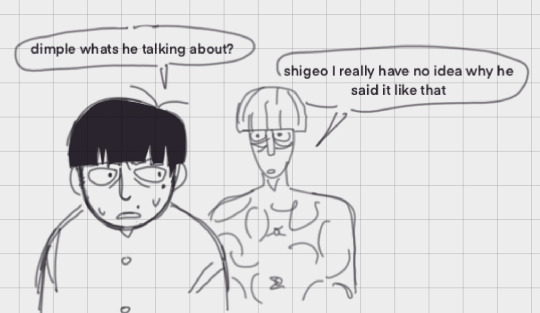

#he’s referring to their rivalry. queerly

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

saw that manga panel today

#he’s referring to their rivalry. queerly#mp100#mp100 fanart#my art#my small pet peeve is people going ‘can’t believe dimple made him say this’ when he didn’t#divine tree teru just entertains me so bad#DO NOT convince a guy with an idolization complex that you are divine he will be like THIS

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

New Post has been published on http://iofferwith.xyz/come-out-come-out-whoever-you-are/

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

Review

Nathan Tipton

Harry M. Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet Homosexuality and the Horror Film. (Manchester: Manchester U P, 1998.) $18.95.

Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are!

1. ��The plot discovered is the finding of evil where we have always known it to be: in the other” (97). So wrote Leslie Fiedler in The End of Innocence (1955), his summation of the McCarthy-era horrors. Although ostensibly referring to the 1953-54 McCarthy hearings, Fiedler discloses the societal fear of difference operating within the “Us versus Them” dialectic. Moreover, by finding evil in an Otherness “where we have always known it to be,” he acknowledges both the historical construction and destruction of the Other and, in effect, explains society’s genocidal predilections in the name of moral preservation. Nevertheless, Fiedler’s comment leaves larger questions unanswered. How, for instance, does society arrive at this conflation of evil and “other?” And does society need to create monsters for the sole purpose of destroying them?

2. Harry M. Benshoff “outs” his Monsters In the Closet with the conceit of a “monster queer” universally viewed as anyone who assumes a contra-heterosexual self-identity, including those outside the established gay/lesbian counter-hegemony (“interracial sex and sex between physically challenged people” [5]). For the sake of brevity, his work focuses on homosexual males and their presence, either tacit or overt, in the modern horror film. In so doing, Monsters also proposes (with more than a passing nod to gay historiographer George Chauncey), an extant gay history created through the magic of cinema. For Benshoff, however, the screening room quickly morphs into a Grand Guignol-styled Theatre of Blood, and gays become metaphorical monsters whose sole purpose in horror films is to subvert society before meeting their expected demise.

3. Benshoff draws a provocative, decade-by-decade timeline to illuminate his thesis. He begins in 1930s Depression-era America, the “Golden Age of Hollywood Horror.” In a chapter entitled “Defining the monster queer,” the cultural construction of the modern homosexual is placed alongside (and within) classic horror films such as Frankenstein and Dracula (both 1931). Benshoff notes the decade’s movement from viewing homosexuals as gender deviants to those engaging in “sexual-object choice (48),” thus underscoring the ideological shift from Other-as-Separate to Other-Among-Us. This, then, becomes his foundation motif for the modern horror cinema: the fears within us are the fears of us.

4. While the chapter concentrates heavily on the actors and their presumed sexuality (including “name” stars such as Charles Laughton and Peter Lorre) rather than the films, Benshoff highlights an obvious thread of filmic homosociality, particularly in the films pairing Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. For example, 1934’s The Black Cat features two “mad” scientists ostensibly competing for one female (although she is later revealed to have been dead all along). Benshoff convincingly reads this arrangement as a homoerotic love triangle, with Poelzig (Karloff) and Werdegast (Lugosi) engaged in teasing flirtation, and finally sado-masochistic torture. The torture scene includes bare-chested Karloff being menaced by scalpel-wielding Lugosi, who threatens (and then proceeds) to “flail the skin from [Poelzig’s] body, bit by bit”(64). Though Benshoff reads the film’s homosociality as a positive step, he nonetheless fails to critique the rather obvious, time-honored homosexual tropes of sado-masochism and murderous psychosis.

5. “Defining the monster queer” also includes a surprisingly short section on director James Whale (on whose life the current film Gods and Monsters is based). Benshoff notes, “A discussion of homosexuality and the classical Hollywood horror film often begins (and all too frequently ends) with the work of James Whale, the openly gay director who was responsible for fashioning four of Universal Studio’s most memorable horror films: Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)” (40). While Frankenstein is arguably the most recognizable film in this quartet, Benshoff instead contextualizes Whale’s work through his most explicitly homosexual film, The Old Dark House, in which Whale parodies and, ultimately, subverts the above-mentioned stereotypical cinematic tropes.

6. This film, like many “clutching hand” horror films of the period, uses the device of “normal” people trapped in a defiantly non-normal mansion peopled with maniacs and monsters. The Old Dark House is occupied by the Femm (!) family members, who each have gayly-coded personas. Patriarch Roderick Femm is enacted by a woman (actress Elspeth Dudgeon); son Horace is played by known homosexual Ernest Thesiger in, Benshoff wryly notes, a “fruity effete manner” (43); and sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) is a hyper-religious zealot who is, nevertheless, a closet lesbian. The heterosexual Wavertons (Raymond Massey and Gloria Stuart), along with their manservant Penderel (Melvyn Douglas), spend the vast majority of the film trying to fend off none-too-subtle homosexual overtures from the Femms, although they too are viewed queerly as an “urban ménage à trois” (44).

7. The story is further complicated by Morgan (Boris Karloff), the drunken butler who “may or may not be an illegitimate son of the house” and Saul (Brember Wills) “the most dangerous member of the family” (45), who is understood as a repressed homosexual. Saul sees in Penderel a kinship but, because of his paranoid repression, must instead kill this object of his desire (with, Benshoff points out, a “long knife” [45]). In the ensuing tussle, Saul falls down the stairs, dies, and is carried off by Morgan, who “miserably minces up the steps, rocking him, his hips swaying effeminately, as if he were some nightmarish mother cradling a dead, horrific infant” (45).

8. Benshoff convincingly hints that the film’s over-the-top depiction of homosexuality was the primary cause of its being “kept out of circulation for many years . . . for varying reasons (legal and otherwise) . . . [and] it was not released on commercial videotape until 1995” (43). In fact, the Production Code established in 1930 forbade any openly (or, Benshoff adds, “broadly connotated”) homosexual characters on-screen and, subsequently, “banished [them] to the shadowy realms of inference and implication”(35). But the problem still remains that even in their connotative presence, homosexuals are portrayed as monsters. Although Whale’s Dark House attempts to imbue some non-normals (such as Morgan) with a sympathetic aura, it does so at the expense of Saul, whose death seems to connote a reinforcement of normality. This status quo death-by-design, indeed, becomes a decades-long device in horror films.

9. As the book progresses, Benshoff moves from homosocial film “outings” to socio-filmic movie interpretations and, in this area, he is clearly more comfortable. In particular, the chapter entitled “Pods, Pederasts and Perverts: (Re)Criminalizing the Monster Queer in Cold War Culture” casts a probing look at the so-called “perfect” 1950s. This decade becomes a touchstone for Benshoff because of the close interrelationship between oftentimes-surreal politics (the McCarthy/HUAC hearings) and “real” cinema. Early films such as Them and The Creature from the Black Lagoon (both 1954) exemplify the dialectic between Us and Them while exploring the dynamic of social denial. Benshoff notes, “As for the closeted homosexual, the monster queer’s best defense is often the fact that the social order actively prefers to deny his/her existence” (129) and thus keep its monsters safely in their closets. His queer reading of Creature, while effective, does not approach the astute discussion of the later films I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) and especially the Black Lagoon sequel, The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), which not only riff on the Marxist dialectic but present the more insidious scenario of the “incorporated queer.”

10. The title of The Creature Walks Among Us, for example, serves as an overt play on people’s paranoia, both of Communists and Queers (terms which, during the McCarthy hearings, were used synonymously), and the film focuses on intense male rivalries, ostensibly over one woman, Helen Barton. However, her husband, Dr. Barton, has paranoid fantasies about her sleeping with Captain Grant, the hunky captain of Barton’s yacht (which, Benshoff notes, is based in San Francisco). Benshoff easily reads Dr. Barton as a repressed homosexual who would much rather be sleeping with Grant. At the film’s climax, he murders Captain Grant (thus killing the object of his desire) and is, in turn, killed by the Creature. Helen reflects on the sad scene by trying to explain her husband’s rather obvious sexual repression. She states, “I guess the way we go depends upon what we’re willing to understand about ourselves. And willing to admit”(136). But her words also can be read as a plea for societal tolerance of “Them,” in whatever form they appear.

11. Benshoff furthers his discussion of Them Among Us by exploring the phenomenon of the “I Was a . . .” films, which “purported to deliver subjective experiences of how political deviants operated” (146), again through horrifically-packaged political treatises such as 1951’s I Was a Communist for the FBI or “real-life” horror films along the lines of I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). These films seek not only to uncover the hidden queer but to expose their insidious agenda of pederastic recruitment. However, for the quintessential 1950s homo-cruitment film Benshoff chooses How to Make a Monster (1958) which, despite its menacing tagline “It Will Scare the Living Yell Out of You,” is viewed as remarkable for “the wide range of signified to which the signifier ‘monster’ becomes attached, and the complexity with which it manipulates these signifiers” (150-51). Translation: How to Make a Monster contains many not-terribly-subtle queer-friendly images that are visible the typical moviegoer, hetero- or homosexual.

12. Benshoff pulls out all the stops in his filmic exploration of How to Make a Monster by deploying a Laura Mulvey-esque theoretical pastiche of deconstruction, Lacanian psychoanalysis, cultural criticism, and Marxism. He concludes that “the film hints at the revolutionary potential of ‘making monsters’ against those same ideological forces . . . which simultaneously create and demonize the monster queer” (151).

13. So what exactly marks this particular Monster for greatness (indeed, a detail of the movie’s poster is part of the book’s cover art)? For starters, the film contains all the elements of a perfectly queer horror flick: a homosexually-coded mad scientist couple Pete and Rivero (complete with “requisite butch/femme stereotyping” [151]) who are, as an added bonus, also tacit pederasts. They are balanced by two “normal” heterosexual teenage All-American boys, Larry and Tony, who nevertheless get “made up” and engage in a clearly homoerotic “Battle of the Monsters.” The story is further complicated by a Marxist interlude during which capitalist movie studio executives arrive and sever their ties with the monstrous director and his makeup-artist-partner. Benshoff observes, “The scene explicitly links the patriarchal order with capitalism, and Pete [the now fired director] and his monstrous world as opposing it. As Pete turns down the offer of severance pay, one of the studio executives clucks ‘Turn down money — maybe you’ve been living too long with monsters'” (153). Pete, rather than accepting his fate, formulates a revenge plot against the capitalist studio executives, and herein invokes another horror film trope — “that which is repressed (in this case the Hollywood monster movie) must eventually return.” However, Benshoff continues, “these particular monsters are not going to be of the imaginary/Make-Believe/Movie/ Sexuality kind; they are going to be deadly” (154).

14. While this revenge plot is a precursor to the spate of 1980s “Everyman” horror films, both heterosexual (Falling Down) and homosexual (The Living End, Swoon), How to Make a Monster utilizes a novel approach for its monstrous aims. As Benshoff explains, “Back in the make-up lab, Pete tells Rivero of his plan to control the young actors through a special novocaine-based make-up: ‘Now — this enters the pores and paralyzes the will. It will have the same effect chemically as a surgical prefrontal lobotomy.1 It blocks the nerve synapses. It makes the subject passive — obedient to my will.'” (154). Ignoring for the moment the clearly Freudian implications of Pete’s speech, the special make-up also predicts date-rape drugs such as “mickeys” or “roofies,” thus adding another sinister aspect to the scene. Moreover, because Pete and Rivero are coded pederasts, the make-up also predicates accusations of “homosexual agenda” brainwashing leveled by the present-day Religious Right.

15. Of course, Freudian phallocentrism is never far away. Benshoff notes, “Rivero attempts to tell Pete that he thinks Pete has made a mistake in bringing the boys to his home. Pete cannot accept Rivero’s taking an active (vocal) role in the proceedings and stabs Rivero in the belly with a knife, asserting his dominance within the active/passive nature of their relationship” (156). The knife, which naturally is read as a phallus, “sends the boys into a homosexual panic: a struggle ensues and the room is set on fire. Pete dies with his melting creations á la Vincent Price in House of Wax (1953), and the cops break down the door and rescue/apprehend Larry and Tony” (156).

16. All’s well that ends well? Benshoff hedges his bets on Larry and Tony, thinking that they have probably been assimilated (he wryly adds that, before the struggle, the boys try to escape by telling Pete, “Larry and I have sort of a dinner date” [156]), but more because they have been repeatedly tainted by the monster queer. Although his overall critique of the film is favorable by citing its pleas for tolerance, he nevertheless condemns it on Marxist grounds for remaining first and foremost a product of the capitalist system. Benshoff argues that, even though How to Make a Monster attempts to subvert society’s view of homosexuals, it remains a product of a system that routinely exploits women and homosexuals. It does so by constructing their images in stereotypically specific ways and, he writes, “As such, the film contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction” (157).

17. This particular critique is borne out in his viewing of 1960s and 70s horror films, which, even with the advent of both the women’s and gay liberation movements, as well as the weakening of the Production Code, still resort to the same “tired” tropes. He selects productions from the UK’s Hammer Films (which produced horror films from the 1950s until 1973) for scrutiny, noting that “the weakening Production Code’s loosening restrictions on sex and violence helped the horror film define itself in new and explicit terms” (177), and singling out Hammer for capitalizing on this new openness. He further adds, “For the first time in film history, openly homosexual characters became commonplace within the genre, sometimes as victims . . . but more regularly as the monsters themselves (the lesbian vampire)” (177).

18. This lesbian vampire becomes a recurring motif in late Hammer films including the “first overtly lesbian film, The Vampire Lovers (1970)” (192), in which hyper-feminine women seduce and destroy other hyper-feminine women. While this is a welcome change from the stereotypical “butch lesbian” seen in earlier horror films, Benshoff cites Bonnie Zimmerman in his enumeration of Hammer’s sins: “lesbian sexuality is infantile and narcissistic; lesbianism is sterile and morbid; lesbians are rich, decadent women who seduce the young and powerless” (23). The Vampire Lovers, for example, features Carmilla (taken from J. Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 vampire novel of the same name) seducing a bevy of “young nubile women in diaphanous nightgowns” (193) and then draining their blood. Her victim Emma, a “rather dim-witted ingenue . . . who, in all of her innocence, tumbles into bed with Carmilla after romping nude together through the bedroom” (193), is nevertheless a heterosexual. After Carmilla expresses love for her, Emma (who doth protest too much, methinks) refuses and instead asks, “Don’t you wish some handsome young man would come into your life?” to which Carmilla replies, “No — neither do you, I hope” (193). Naturally, Carmilla must be and is destroyed by, Benshoff notes, “patriarchal agents” (194) (although he doesn’t specify who these agents are) and Emma and her boyfriend Carl are reunited.

19. Benshoff astutely comments on Hammer Films’ success among heterosexual males by noting, “the appeal of these Hammer films was ostensibly directed to the straight male spectator through soft-core nudity and sexual titillation” (196). The film(s), rather than focusing on the lesbianism (although this is a significant, though unspoken, “guilty pleasure”), instead rely on “ample cleavage and sheer peignoirs” (194), and therein lies their appeal. While these nymphet vampire lesbians faded from view in the later 1970s, the scantily-clad “screaming Mimi” victims remain firmly entrenched in postmodern horror films of the 1980s and 90s, although they are primarily coded as exclusively heterosexual.

20. The advent of the postmodern horror film in the 1980s and 90s heralds a new look at old tropes, particularly the monster among us. In “Satan spawn and out and proud: Monster queers in the postmodern era,” these films, repeatedly deploying overt homoeroticism, riff on the perils of difference, repression, and (not surprisingly) coming-out, thus giving Benshoff fertile ground for exploration. For example, 1981’s Fear No Evil, a Religious Right-esque shockumentary, pits Lucifer (portrayed initially as Andrew, a shy, effeminate high-school senior before “coming out”) against the forces of Absolute Good (read: “normal” heterosexuals). The film is highlighted by a nude gym shower teasing/quasi-seduction scene involving Andrew and Tony, the requisite high-school bully figure, in which “Tony mockingly asks [Andrew] for a date, and then a kiss. Rather improbably, Tony does kiss Andrew, to the accompaniment of a rumbling, reverberating, grunting sound-track and swirling camerawork” (239, emphasis added).

21. Fear No Evil further exacerbates the thematic homosexual menace with what Benshoff terms a “retrograde ideology,” in that “When the Devil/Andrew again kisses [him,]Tony . . . manifest[s] female breasts. The implication here is unmistakably clear and totally in line with traditional notions of gender and sexuality: Devil = homosexuality = gender inversion. Upon manifesting the breasts, Tony does the only decent thing he can do . . . and stabs himself to death” (239). Stabbing, indeed, seems to be the preferred method of dispatch in horror films, and it is easy to see Tony’s action as a phallic impaling. Furthermore, it also reflects back to Larry’s and (another!) Tony’s homosexual panic in How to Make a Monster, although the postmodern Tony, who has tacitly “given in” to his homosexuality, must die.

22. Two problems, however, immediately arise in Benshoff’s reading: his use of the word “traditional” and the ignorance of the multiple kisses. His pronouncing the pairing of homosexual panic and gender inversion as a “traditional notion” would be acceptable for 1950s films but becomes highly suspect for postmodern-era films. While not to denigrate audiences of 1950s schlock-horror, audiences in the 1980s and 1990s are imbued with a cynicism that, upon viewing this ridiculous scene, would manifest itself in guffaws. Moreover, Benshoff misses or fails to comment on the view of latent homosexuality apparent in Tony. What, then, does it really say about Tony that he asks (teasingly?) Andrew for a date and then kisses him not once but twice, apparently of his own free will? Benshoff reads the scene as an overt metaphor for homosexual panic as gender inversion but fails to see the potential (positive?) societal comment that any homophobic bully is likely acting against his own homosexual feelings.

23. Additionally, given the “rumbling, reverberating, grunting sound-track and swirling camerawork” in Fear No Evil, it is surprising that Benshoff doesn’t draw a correlation between the postmodern horror film and outright pornographic films — other than the snide comment, “Apparently, the Devil really knows how to use his tongue” (239). His “Epilogue,” however, does comment on gay porno’s appropriation of vampiric themes immediately following the release of Interview With the Vampire. Indeed, these films acknowledge a number of gay pornographic productions including Does Dracula Really Suck? (1969), Gayracula (1983), and the non-porno (read: sans explicit sex) Love Bites (1988) which, Benshoff notes, “approached the generic systems of gothic horror in an attempt to draw out or exorcise the monster from the queer” (286).

24. While this reading is plausible, it problematically equates gay porno audiences with those of “conventional” cinema. The reading elides the fact that the ostensible “motivation” for any porno film is a memorable climax (and not necessarily from the film’s actors). Benshoff, however, cites Love Bites as exemplary, not for escaping the confines of porno, but for rewriting “generic imperatives from a gay male point of view” and “allow[ing] both Count Dracula and his servant Renfield to find love and redemption with modern-day West Hollywood gay boys” (286). The film, therefore, both creates a “positive” monster and aspires to mainstream appeal.

25. Benshoff concludes that mainstream postmodern horror films also show remarkable progress in the area of homosocial qua homosexual cinematic portrayals. Fright Night (1985), gay author Clive Barker’s Night Breed (1990), and “straight queer” Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands (also 1990) receive especially high praise for their positive attempts at positing an “alternative normal” while not resorting to stereotypical queer tropes. However, the films share the common subversive element of camp, and it is through this humor that they ultimately succeed in humanizing the monster queer. Benshoff quotes Clive Barker as stating, “We should strive to avoid feeding delusions of perfectibility and instead celebrate the complexities and contradictions that, as I’ve said, fantastic fiction is uniquely qualified to address. . . . But we must be prepared to wear our paradoxes on our sleeve” (Jones 75) and indeed, camp manifests itself as a paradox.

26. Again, however, Benshoff surprisingly misses an opportunity to view the films as critiques of suburbia and inbred suburban intolerance, for many of the postmodern films concern themselves with spinning a new urban/suburban dialectic. The urban, ostensibly viewed as the dangerous inner city (and exclusively home to black and gay ghettos) is contrasted with the idyllic (read: white heterosexual and, paradoxically, nostalgically 1950s-esque) suburban landscape.

27. Fright Night riffs on this suburban Invasion of the Body Snatcher motif, but this time the queers are clearly “out” and bent on infiltrating Fortress Suburbia. In the film, Chris Sarandon’s vampiric alter-ego Jerry Dandridge is posited as a tacitly gay antique dealer, replete with bourgeois trappings and attitudes. In other words, Jerry is tailor-made for the postmodern suburbia that Benshoff negatively reads. He subtly voices the same problematic anti-assimilationist view held by many quasi-Marxist queer theorists and activists (Urvashi Vaid, former head of NGLTF — the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, being the most prominent) that has subsequently led to fracturing, rather than unifying, the gay “body politic.” This view is further exacerbated by Benshoff’s resigned comment that the film, “despite its fairly realistic representation of what a gay male couple in the suburbs might look like . . . nonetheless still partakes of the same demonizing tropes as do less sophisticated horror films: queerness is monstrous” (252, emphasis added). I accept Benshoff’s statement within the book’s context, but am troubled by its pessimistic implication that homosexuals can never rise out of their monstrous otherness.

28. Monsters in the Closet is by no means a perfect book. There are flashes of brilliance, humor, and dead-on cinematic readings and critiques. It is, however, balanced by often pedantic (or worse, supra-academic) jargon, generalizations, and sometimes far-fetched film interpretations. More often than not, his cinematic evidence comes through “close readings” of these horror films but reaches problematic status when he draws tenuous connections with exploitation (especially blaxploitation) and quasi-horror films (such as 1974’s Earthquake).

29. Benshoff also deploys an authorial predilection for outing that, at times, repeatedly belabors the queerness of the films. This is particularly troublesome in the first chapter, which seems more concerned with the sexualities of the stars than how they performed their roles. In later chapters, he occasionally indulges in outright finger pointing as illustrated by his noting that “many gay fans considered Tom Cruise’s acceptance of the role of Lestat [in 1994’s Interview With the Vampire] more or less a coming-out declaration” (273). While Cruise’s sexuality has been subject to continual speculation in the gay community, Benshoff’s comment adds nothing to his overall critical appraisal of the film and reads more as his own wistful and wishful fantasy. Moreover, in “Pods, pederasts and perverts,” he perplexingly hides behind the wall of murky Hollywood history when discussing older “stars like James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Farley Granger, Sal Mineo, Anthony Perkins, Rock Hudson, and Marlon Brando” whose sexualities Benshoff cautiously defines as “non-straight” (173). No Signorile he, Benshoff’s evident conflating of the terms “non-straight” and “queer” as anything outside the norm becomes problematic because it denies the definitively gay identities of Clift, Mineo, Hudson, and Perkins, thereby lessening any possible socio-political ramifications.

30. In these respects, it is ultimately weak as film criticism. However Monsters is, despite its drawbacks, a worthy entry into the field of Gay and Lesbian historical constructions. Its decade-by-decade “timeline” deftly illustrates, through the medium of film, a recurring queer presence that survives, transforms, and, against all odds (much like its monstrous counterparts), keeps popping up in the most unexpected places.

Note

1 Interestingly enough, this “device” was also used in another 1950s “real-life horror film,” Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer (1959), about which Vito Russo notes, “Sebastian Venable is presented as a faceless terror, a horrifying presence among normal people, like the Martians in War of the Worlds or the creature from the black lagoon. As he slinks along the streets of the humid Spanish seacoast towns in pursuit of boys (‘famished for the dark ones’), Sebastian’s coattail or elbow occasionally intrudes into the frame at moments of intense emotion. He comes at us in sections, scaring us a little at a time, like a movie monster too horrible to be shown all at once.” (117).

Works Cited

Benshoff, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester: Manchester U P, 1997.

Fiedler, Leslie. “McCarthy as Populist.” An End to Innocence. Boston: Beacon, 1955. Rpt. in The Meaning of McCarthyism, 2nd ed. Ed. Earl Latham. Lexington, MA: Heath, 1973.

Jones, Stephen, ed. Clive Barker’s Shadows in Eden. Lancaster, PA: Underwood-Miller, 1991.

Russo, Vito. The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. Rev. ed. New York: Harper, 1987.

Zimmerman, Bonnie. “Daughters of Darkness: Lesbian Vampires.” Jump Cut 24.24 (1980): 23-24.

Contents copyright © 1998 by Nathan Tipton.

Format copyright © 1998 by Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087, Volume 2, Number 1, Fall 1998.

0 notes