#gvk v. B 19

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

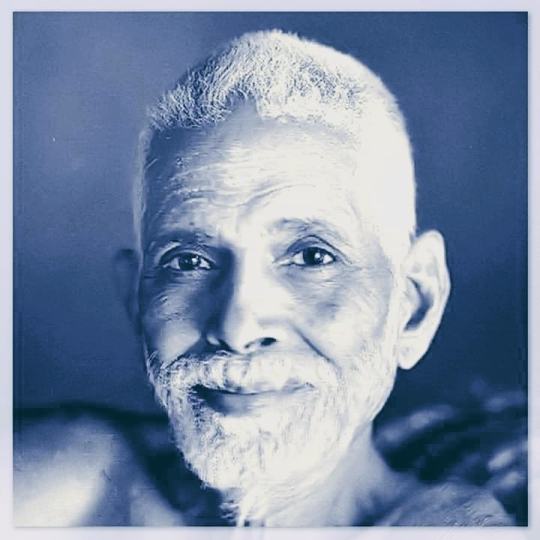

Photo

🕉️ 🔱 Om Namo Bhagavathe Sri ArunachalaRamanaya 🔱 🕉️

15. The Pervasiveness of Sleep (Sushupti Vyapaka Tiran)

957. Do not be disheartened and lose your mental vigour thinking that [the state of experiencing] sleep in dream has not yet been obtained. If the strength of [experiencing] sleep in the present waking state is obtained, then [the state of experiencing] sleep in dream will also be obtained.

Sadhu Om: The words ‘sleep in the present waking state’ [anavum nanavil sushupti] denote the state of wakeful sleep [jagrat-sushupti] or turiya, the state of experiencing no differences during waking. In order to attain this state, aspirants have to make efforts in the waking state. However, some aspirants used to ask Sri Bhagavan, “Do we also have to make such efforts in dream, so that we may attain the state of experiencing no differences even during dream?” This doubt is answered by Sri Bhagavan in this verse.

The feeling ‘I am this body’ [dehatma-buddhi] rises in the subtle body during dream only because of the habit of identifying the gross body as ‘I’ during waking. Hence, if one practices Self-enquiry in the waking state and thereby eradicates the dehatma-buddhi [the habit of thus identifying a body as ‘I’] in this state, that itself will be sufficient to eradicate the dehatma-buddhi in dream also. Therefore Sri Bhagavan advises in the next verse that, until the dehatma-buddhi is completely eradicated even in dream, one should not give up Self-enquiry in the waking state. Refer here to the fourth paragraph of the first chapter of Vichara Sangraham where Sri Bhagavan says,

“All the three bodies [gross, subtle and causal] consisting of the five sheaths (*) are included in the feeling ‘I am the body’. If that one [i.e. the identification with the gross body] is removed, all [i.e. the identification with the other two bodies] will automatically be removed. Since [the identification with] the other bodies [the subtle and causal] survive only by depending upon this [the identification with the gross body], there is no need to remove them one by one.”

The words ‘kanavil sushupti’ [sleep in dream]), which are used in the first and last lines of this verse, may also be taken to mean ‘sleep without dream’, in which case the following alternative meaning can be given:

“Do not be disheartened and lose your mental vigour thinking that sleep without dream has not yet been obtained. If the strength of [experiencing] sleep in the present waking state is obtained, then sleep without dream will also be obtained.”

958. Until the state of sleep in waking [i.e. the state of wakeful sleep or jagrat-sushupti] is attained, Self-enquiry should not be given up. Moreover until sleep in dream is also attained, it is essential to persist in that enquiry [i.e. to continue trying to cling to the mere feeling ‘I’].

Michael James: The ideas in the above two verses were summarized by Sri Bhagavan in the following verse.

B 19. The state of sleep in waking [or jagrat-sushupti] will result by constant scrutinizing enquiry into oneself. Until sleep pervades and shines in waking and in dream, do that enquiry continuously.

~ Guru Vachaka Kovai (The Garland of Guru's Sayings) - Part Three - The Experience Of The Truth

__________

(*) A kosha, usually rendered “sheath”, is a covering of the Atman, or Self according to Vedantic philosophy. There are five koshas, and they are often visualised as the layers of an onion.

From gross to fine they are:

Annamaya kosha, “body” sheath - Anna means food, which is what sustains this level

Pranamaya kosha, "energy” sheath (Prana)

Manomaya kosha, “mind” sheath (Manas)

Vijñānamaya kosha, “discernment” sheath (Vijnana)

Anandamaya kosha, “bliss” sheath (Ananda)

ॐ

Arunachala at Sunrise Art Print

by Susan Rankin - fineartamerica

#Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi#Muruganar#Guru Vachaka Kovai#gvk v.957#gvk v.958#gvk v. B 19#sleep dream waking states#turiya#fourth state#natural state#wakeful sleep#turiyatita#transcendental state#dehatma-buddhi#'I-am-the-body'-idea#self-enquiry#self-investigation#who am i?#Vichara Sangraham#five sheaths or panchakosas

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Analysis of Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Introduction

Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 deals with the Interim measures which a party to an arbitral proceeding may ask for before the commencement or during the pendency of an arbitral proceeding or at a particular time to the adjudicating authority. The adjudicating authority or the court may then pass an interim measure which is in line with the provisions provided under Section 36 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. This section provides the court the power to invoke interim measures of protection. The provisions under Section 9 provide a complete list of protections which the court can offer while deliberating an arbitral proceeding or before the commencement of an arbitral proceeding. Section 9 can be deemed to be regarded as one of the most important provisions falling under the scope and the ambit of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. In fact, this is one of the provisions of the act which is invoked majorly by the law courts.

The interim measures which are laid down under the scope of Section 9 can be deemed to be regarded as those provisions which are extremely crucial to avoid the occurrence of a damage or to prevent the loss from the focus of attention of the dispute or from the subject-matter of the dispute or the case in the interim period, that is, before the matter is concluded or adjudicated by an arbitral tribunal.

Commonly, the provisions guaranteed under Section 9 can be deemed to be regarded as a relief which is quite imperative during the commencement of an arbitration proceeding and a lot of times, the matter can be simply be won when the court or the adjudicating authority provides a relief on the basis of the provisions laid down under this section.

Scope of Section 9

Under the scope of Section 9, the adjudicating authority or the arbitral tribunal has been conferred with a number of powers that enable it to provide interim measures as a means of protection as it deems fit to the court. It can confer interim measures such as providing interim custody or sale of goods which are the main focus of attention of the arbitration proceedings. It can also pass orders helping the parties to secure amounts in dispute. It can also grant an interim injunction stopping an activity and can also deal with the appointment of a receiver or a guardian. The following are the measures which the court can provide under the provisions guaranteed by Section 9.

Section 9- Interim measure, etc., by Court- “(1) A party may, before or during arbitral proceedings or at any time after the making of the arbitral award but before it is enforced in accordance with Section 36, apply to a court-

i) For the appointment of a guardian for a minor or person of an unsound mind for the purposes of arbitral proceedings; or

ii) For an interim measure of protection in respect of any of the following matters, namely: –

a) The preservation, interim custody or sale of any goods which are the subject-matter of the arbitration agreement;

b) Securing the amount in dispute in the arbitration;

c) The detention, preservation or inspection of any property or thing which is the subject-matter of the dispute in arbitration, or as to which any question may arise therein and authorising for any of the aforesaid purposes any person to enter upon any land or building in the possession of any party, or authorising any samples to be taken or any observation to be made, or experiment to be tried, which may be necessary or expedient for the purpose of obtaining full information or evidence;

d) Interim injunction or the appointment of a receiver;

e) Such other interim measure of protection as may appear to the Court to be just and convenient,

And the Court shall have the same power for making orders as it has for the purpose of, and in relation to, any proceedings before it.

(2) Where, before the commencement of the arbitral proceedings, a Court passes an order for any interim measure of protection under sub-section (1), the arbitral proceedings shall be commenced within a period of ninety days from the date of such order or within such further time as the Court may determine.

(3) Once the arbitral tribunal has been constituted, the Court shall not entertain any application under sub-section (1), unless the court finds that circumstances exist which may not render the remedy provided under Section 17 efficacious.”[1]

The Delhi High Court in the case of Leighton India Contractors Private Ltd. v. DLF Ltd.[2] provided that the ambit of Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 is quite huge and it can be deemed to be regarded as quite extensive. This provision under no circumstances limits the powers which have been conferred upon the adjudicating authorities. The adjudicating authorities have been conferred with a wide range of powers, however, its authority and its powers are quite well-recognized. In the case of Adhunik Steels Ltd v. Orissa Manganese and Minerals[3], the court held that despite the court having wide powers conferred upon them the authority of the court is not unbridled. The court further elucidated that the well-recognised principles which govern the court in the grant of interim orders apply to the various petitions filed by the parties under the provisions of Section 9.[4]

With regards to an injunction passed by the adjudicating authority against the calling of bank guarantees is concerned, the High Court of Delhi in the case of Halliburton Offshore Services Inc. v. Vedanta Limited[5], reiterated that, “if fraud, irretrievable injury or special equities are not proved, then under such circumstances an injunction cannot be granted.” [6] Further, with regards to collecting the necessary amounts due, the Delhi High Court in the case of Goodwill Non-Woven (P) Limited v. Xcoal Energy & Resources LLC [7] passed a judgement on the 9th day of June, 2020 and reiterated that simply because the petitioner is not in the position to invoke the arbitration proceedings in light of the Covid-19 pandemic does not mean that the case has no standing. The petitioner was, however, not able to convince the Court for the granting of the interim relief. The petitioner also relied upon the various tests which were laid down in the case of BMW India Private Limited v. Libra Automotives Private Limited & Ors.[8] stating the various tests which were laid down in this case for the granting of the interim relief, however, the court did not pass any relief in this case.

Section 9 in consonance to Section 17 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

According to the 2015 amendment which was made to the Act, Section 9 of the Act was amended so that it could identify the powers provided under the scope of Section 17 (which was deemed to be at par with the provisions provided under Section 9) and this would help in reducing the work of the courts while granting interim protections once the adjudicating authority or the arbitral tribunal was setup. However, the 2015 Amendment neither curtailed the powers of the courts nor did it reduce the work of the courts. In fact, the powers conferred upon the courts to grant interim protection can still be deemed to be regarded of great significance. It is imperative to note that before a tribunal is constituted and after an award is passed, the power to provide an interim protection or an interim relief lies solely in the hands of the court. The amendment which was made in 2019, omitted the words and figures, “or at any time after the making of the arbitral award but before it is enforced in accordance with Section 36” [9] from Section 17 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. It can be said that once an arbitral tribunal is set up in consonance to the provisions guaranteed under Section 9(3)[10] of the Act, then the adjudicating authority cannot deal with an application provided under the provisions of sub-section (1), unless it is of the opinion that the situation which exists may not deem the remedy provided under the provisions of Section 17 as efficacious. The Delhi High Court, in the case of Benara Bearing & Pistons Ltd v. Mahle Engine Component India Pvt. Ltd.[11] held that the provision guaranteed under Section 9(3) of the Act cannot be deemed to be regarded as a privative clause with regards to the powers which are conferred upon the court and the court’s jurisdiction which is provided under the provisions of Section 9 cannot be taken away. The court further reiterated that if an application falls under the scope of providing an efficacious remedy under Section 17 of the Act, then under such circumstances, an immediate interim relief shall be granted by the arbitral tribunal as was also provided in the case of Bid Services Division (Mauritius) Limited v. GVK Airport Holdings Pvt.Ltd & Ors.[12] which was also deliberated before the Delhi High Court.

However, there may be other circumstances too, under which it may not be advisable to obtain an efficacious remedy or an efficacious interim relief from the tribunal as was held in the case of Bhubaneshwar Expressway Pvt. Ltd. v. NHAI[13] , wherein the tribunal was setup, however the arbitration proceedings could not commence as one of the co-arbitrators was disqualified. The Delhi High Court then laid down that the remedy which is guaranteed under the scope and ambit of Section 17 cannot be deemed to be regarded as efficacious and it would be imperative for it to deal with the petition under the provisions of Section 9 of the Act. All in all, it is clear that under the provisions of Section 9 of the Act, it can be said that the adjudicating authority has the powers conferred in it to pass the necessary orders against the third parties as provided by the Delhi High Court in the judgement passed by it in the case of M/S Value Advisory Services V. M/S ZTE Corporation & Ors[14]. However, what is not clear is whether there are powers vested in the tribunal which enables the tribunal to pass various orders against a third party. Therefore, it is imperative to understand that in the cases wherein the interim relief is prayed for against a third party; the parties shall approach the court under the provisions of Section 9 of the Act.

It is imperative to understand the judgement passed by the Delhi High Court in the case of Hero Wind Energy Private Limited v. Inox Renewables Limited and Ors[15], wherein a petition was filed under the provisions of Section 9 of the Act before the Delhi High Court post the constitution of an arbitral tribunal. Amongst all the other grounds taken by the petitioner to prove the maintainability of the petition under the provisions of Section 9, it is necessary to understand one of the most important grounds taken by the petitioner. The petitioner prayed for a relief against a non-signatory or against a third party to the arbitration agreement. The Court, however, deliberated upon the same and rejected the contention put forth by the petitioner on the basis of the principles laid down in the judgement of Chloro Control India Pvt. Ltd v. Severn Trent Water Purification Inc. and Ors.[16]

Section 9 and Emergency Arbitrator.

A number of arbitration institutes based in India as well as abroad provide a provision for the availability of an Emergency Arbitrator. The main aim of this provision is to ensure that an adjudication procedure is carried out on an urgent interim relief which cannot perhaps wait until the setup or the constitution of a tribunal is done. Therefore, a petitioner, instead of making an application under the provisions guaranteed under Section 9 of the Act, can directly approach and get a relief by the Emergency Arbitrator. The passing of an order granting an interim relief can be passed or can be granted by Emergency Arbitrators. However, the question whether Emergency Arbitrators can grant an interim relief in arbitration proceedings which are majorly conducted in the foreign countries is still uncertain. At present, there are no provisions laid down in the Act which provide for the granting of an interim relief passed by an Emergency Arbitrator when the arbitration proceedings are conducted abroad. The provisions under Section 2(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, however provide the provisions for Domestic Arbitration or arbitration proceedings which are conducted in India, however it also provides that, “…subject to an agreement to the contrary, the provisions of sections 9, 27 and clause (a) of sub-section (1) and sub-section (3) of Section 37 shall apply to international commercial arbitration, even if the place of arbitration is outside India…”[17] This simply means that the provisions of Section 2(2) state that the provisions guaranteed under the ambit of Section 9 can very well be applied to arbitration proceedings which are seated in a foreign country, outside India. It is imperative to highlight the case of Raffles Design International India Pvt.Ltd. v. Educomp Professional Education Ltd.[18]. In this case, the parties reached out to the Emergency Arbitrator and filed a petition under the provisions of Section 9, demanding the same relief which they approached the Emergency Arbitrator with. The Delhi High Court, in this case, submitted that it can accept the petition filed under the provisions of Section 9 and reiterated that the parties are not disallowed from approaching the Emergency Arbitrator and at the same time approaching the Court seeking for the same relief under the provisions of Section 9. The High Court stated that it can deliberate upon such a petition and pass an interim relief on the said matter if it deems fit. A matter resembling the abovementioned case came up before the Delhi High Court recently. In the case of Mr. Ashwani Minda & Anr v. U-Shin Ltd & Anr.[19], wherein the parties approached the Emergency Arbitrator seeking relief, however, the Emergency Arbitrator did not grant any relief. The Emergency Arbitrator was appointed by the Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (JCAA). The petitioner later approached the High Court of Delhi and filed a petition under the provisions of Section 9 of the Act for the grant of an interim relief. The Delhi High Court, however provided that the petition could not be maintained as the parties had overlooked the provisions guaranteed under Part I of the Act, including the provisions guaranteed under Section 9. The court further elucidated that if a party approaches an Emergency Arbitrator, then the petitioner in such a dispute cannot further go on to approach the High Court for the redress of the same relief if no relief is granted by the Emergency Arbitrator; also, the court provided that the High Court is not a court of appeal which deals with the orders passed by an Emergency Arbitrator. The Delhi High Court, therefore, rejected the petition filed by the petitioner in this case. The Court passed the abovementioned judgement keeping in mind the judgement passed by it in the Raffles[20] case. The court elucidated that in the Raffles case, applicability of Section 9 of the Act was not excluded as there was no specific clause or provision which specially dealt with the exclusion of this provision. The next point which the court elucidated upon was that the rules under which the arbitration proceedings were seated in the Raffles case was under the SIAC Rules, which granted the parties to the proceedings to seek interim relief by approaching a court. However, in the case of Mr. Ashwani Minda & Anr v. U-Shin Ltd & Anr.[21], the parties to the dispute had not accepted the applicability of Section 9 of the Act and this rendered it impossible for them to seek a relief from the Court. The Court, after passing the judgement in the Ashwani Minda case[22], held that the parties who first approach the Emergency Arbitrator and then file a petition under the provisions of Section 9, even when there are no explicit provisions provided which render the provisions of Section 9 to be excluded, cannot be entertained by the Court. It is pertinent to note that in the case of Domestic Arbitration proceedings, there has been no solid precedent passed by the Court which specifically deals with these aspects concerning an Emergency Arbitrator.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, it can be stated that the provisions guaranteed under the scope and the ambit of Section 9 are very imperative to understand and these provisions can be deemed to be regarded as a crucial remedy while an arbitration proceeding is seated. The Courts and the legislative bodies are working towards ensuring that parties no longer adhere to the provisions of Section 9 and keep seeking interim relief under it, as the grant of an interim relief in itself means that one of the parties has partially won the matter. The Courts and the legislative bodies wish to ensure that the parties do not approach the court seeking an interim relief after an arbitral tribunal is constituted, however, this can only happen after the remedy provided under Section 17 of the Act becomes totally efficacious. The Courts have carefully scrutinized a number of such petitions filed before it and has exercised the powers of Section 9 to the bare minimum. The Courts are taking cognizance of these petitions carefully as India is slowly progressing towards becoming an arbitration friendly jurisdiction. Regardless of all this, the provisions guaranteed under Section 9 are very essential as a number of international arbitration institutes contend that the granting of an interim relief by a domestic court in certain cases is quite necessary and the provisions of Section 9 will continue to be enforced by the parties to an arbitration proceeding.

[1] Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

[2] O.M.P (I) (COMM)109/2020, I.A. 3820/2020 & I.A. 3821/2020, Decided on 13.05.2020.

[3] Appeal (Civil) 6569 of 2005, decided on 10.07.2007.

[4] Adhunik Steels Ltd v. Orissa Manganese and Minerals, Appeal (Civil) 6569 of 2005, decided on 10.07.2007.

[5] O.M.P (I) (COMM.) No. 88/2020 & I.As. 3696-3697/2020, Decided on 29.05.2020.

[6] Halliburton Offshore Services Inc. v. Vedanta Limited, O.M.P (I) (COMM.) No. 88/2020 & I.As. 3696-3697/2020, Decided on 29.05.2020.

[7] O.M.P (I) (COMM) 120/2020, decided on 09.06.2020.

[8] O.M.P (I) (COMM.) 25/2019 and I.A. 3027 of 2019.

[9] Section 17-Interim measures ordered by arbitral tribunal, The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

[10] Section 9(3) states, “Once the arbitral tribunal has been constituted, the Court shall not entertain an application under sub-section (1), unless the Court finds that circumstances exist which may not render the remedy provided under Section 17 ‘efficacious.’”, The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

[11] ARB.A.(COMM.) 11/2017, Decided on: 05.04.2018.

[12] ARB. A. (COMM.) 4/2020, CAV 91/2020 AND IA 1408/2020.

[13] O.M.P (I) (COMM.) 218/2019.

[14] OMP No. 65/2008, decided on 15.07.2009.

[15] O.M.P (I) (COMM.) 429/2019.

[16] Civil Appeal No. 7134 of 2012.

[17] Section 2(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

[18] O.M.P. (I) (COMM.) 23/205 & CCP (O) 59/206, IA Nos. 25949/205 & 2179/2016.

[19] OMP. (I) (COMM.) 90/2020, decided on 12.05.2020.

[20] O.M.P. (I) (COMM.) 23/205 & CCP (O) 59/206, IA Nos. 25949/205 & 2179/2016.

[21] OMP. (I) (COMM.) 90/2020, decided on 12.05.2020.

[22] OMP. (I) (COMM.) 90/2020, decided on 12.05.2020.

The post Critical Analysis of Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 appeared first on Legal Desire.

Critical Analysis of Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 published first on https://immigrationlawyerto.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Photo

🕉️ 🔱 Om Namo Bhagavathe Sri ArunachalaRamanaya 🔱 🕉️

15. A Abrangência do Sono (Sushupti Vyapaka Tiran)

957. Não desanime e não perca o seu vigor mental pensando que [o estado de experimentar] o sono no sonho ainda não foi obtido. Se a força de [experimentar] o sono no presente estado de vigília for obtida, então [o estado de experimentar] o sono no sonho também será obtido.

Sadhu Om: As palavras ‘sono no presente estado de vigília’ [anavum nanavil sushupti] denotam o estado de sono acordado [jagrat-sushupti] ou turiya, o estado de não experimentar diferenças durante a vigília. Para atingir este estado, os aspirantes têm que fazer esforços no estado de vigília. No entanto, alguns aspirantes costumavam perguntar a Sri Bhagavan: “Nós também temos que fazer tais esforços no sonho, para que possamos atingir o estado de não experimentar diferenças mesmo durante o sonho?” Esta dúvida é respondida por Sri Bhagavan neste versículo.

O sentimento 'eu sou este corpo' [dehatma-buddhi] surge no corpo subtil durante o sonho apenas por causa do hábito de identificar o corpo grosseiro como 'eu' durante a vigília. Portanto, se alguém pratica a Auto-investigação no estado de vigília e assim erradica o dehatma-buddhi [o hábito de identificar assim um corpo como 'eu'] neste estado, isso será suficiente para erradicar o dehatma-buddhi no sonho também. Portanto, Sri Bhagavan aconselha no versículo seguinte que, até que o dehatma-buddhi seja completamente erradicado, mesmo em sonho, não se deve desistir da Auto-investigação no estado de vigília. Remete-se aqui para o quarto parágrafo do primeiro capítulo de Vichara Sangraham, onde Sri Bhagavan diz:

“Todos os três corpos [grosseiro, subtil e causal] consistindo nas cinco bainhas (*) estão incluídos no sentimento 'eu sou o corpo'. Se aquela [ou seja, a identificação com o corpo grosseiro] é removida, tudo [i.e. a identificação com os outros dois corpos] será automaticamente removida. Uma vez que [a identificação com] os outros corpos [o subtil e o causal] sobrevivem apenas dependendo disso [a identificação com o corpo grosseiro], não há necessidade de os remover um por um.”

As palavras 'kanavil sushupti' [sono no sonho]), que são usadas na primeira e na última linha deste versículo, também podem significar 'sono sem sonho', caso em que o seguinte significado alternativo pode ser dado:

“Não desanime e não perca o seu vigor mental pensando que o sono sem sonho ainda não foi obtido. Se a força de [experimentar] o sono no presente estado de vigília for obtida, então o sono sem sonho também será obtido.”

958. Até que seja alcançado o estado de sono na vigília [i.e. o estado de sono desperto ou jagrat-sushupti], a auto-investigação não deve ser abandonada. Além disso, até que o sono no sonho também seja alcançado, é essencial persistir nessa investigação [i.e. continuar tentando agarrar-se ao mero sentimento 'eu'].

Michael James: As ideias nos dois versículos acima foram resumidas por Sri Bhagavan no versículo seguinte.

B 19. O estado de sono na vigília [ou jagrat-sushupti] resultará da constante investigação escrutinadora de si mesmo. Até que o sono permeie e brilhe na vigília e no sonho, faça essa investigação continuamente.

~ Guru Vachaka Kovai (Grinalda das Palavras do Guru) - Parte Três - A Experiência Da Verdade

_________

(*) Kosha, habitualmente traduzida como “bainha”, é uma camada de cobertura de Atman, ou Ser, de acordo com a filosofia do Vedanta. Há cinco koshas, e costumam ser visualizadas como as camadas de uma cebola. Da mais grosseira até à mais subtil, são:

Annamaya kosha, “Corpo físico” - Anna significa alimento, que é o que sustenta este nível

Pranamaya kosha, “Corpo de energia” - Prana

Manomaya kosha “Corpo mental” - Manas

Vijñānamaya kosha, “Corpo de sabedoria” - Vijnana

Anandamaya kosha, “Corpo de felicidade” - Ananda

Arunachala North Facing - Art Print by Susan Rankin

#Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi#Muruganar#Guru Vachaka Kovai#gvk v.957#gvk v.958#gvk v. B 19#sono sonho vigília#turiya#quarto estado#estado natural#jagrat-sushupti#sono acordado#sono desperto#turiyatita#estado transcendente#dehatma-buddhi#ideia-'eu-sou-o-corpo'#auto-inquirição#auto-investigação#quem sou eu?#Vichara Sangraham#kosha#cinco camadas

5 notes

·

View notes