#guilhem de poitiers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Duke Konan's heir, Tugdual mab Konan de Rennes stole a keg of wine together with his partner in crime Hamon mab Elina Leon, and was caught by the cook Martha. Tugdual watched and kept a lookout for Hamon while abstaining from drinking the wine himself. Tugdual appears to be practising his Temperate trait, but Duke Konan teaches him to take personal responsibility for his actions and thus changed Tugdual's trait to that of Diligent.

Our Court Physician Iehan has trouble reading the atrocious translation of Hippocrates book. Duke Konan offers Iehan his assistance to translate the text, which increased Iehan's Learning by 2 and gave Konan 300 Learning Lifestyle Experience.

With that we unlock the Learning Lifestyle Perk of Embrace Celibacy. Unfortunately, because Duke Konan has the Eager Reveler trait we cannot take the Embrace Celibacy decision. This seems like a bug rather than a feature.

Duke Konan declares war on Prince Owain III ap Maredudd of Deheubarth for the Principality of Deheubarth.

Our new Spymaster, Trggvi uncovered a secret of Duke Guilhem VIII 'the Tyrant' of Aquitaine, that of him murdering his sister Agnes de Poitiers. We gain a Strong Hook through blackmailing Duke Guilhem, and made him pay us 60 gold.

For some reason, we lost our alliance with Earl Eadric 'the Wild' of Shropshire - apparently because AEthelhild Eadricdohtor Aelfricson decided to divorce Duke Konan's bastard half-brother Jafrez mab Alan de Rennes and remarried her soulmate Prince William II.

We unlocked a new Dynasty Legacy for the Prydain Dynasty - Mostly Fair, which giver a Popular Opinion of +5 and a 30% reduction in Hunt and Feast Cost.

Despite a last minute hail-Mary in getting an alliance with the Petty Kingdom of Munster, Prince Owain (now Lord Owain IV ap Maredudd of Dyfed) loses the war and the Principality of Deheubarth to Duke Konan and becomes Duke Konan's latest vassal.

1 note

·

View note

Text

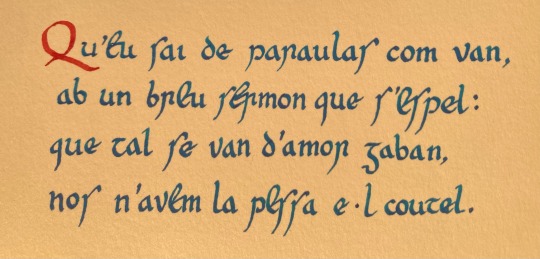

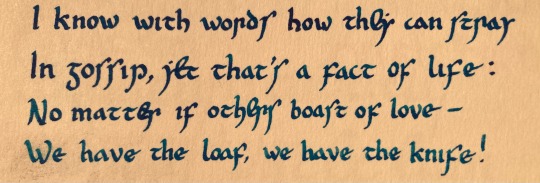

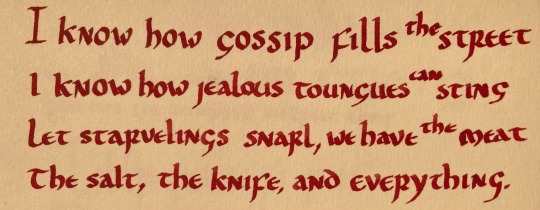

the last four lines of Ab la dolchor del temps novel by Guillaume de Poitiers in the original Provençal, then A. S. Kline's translation at poetryintranslation.com, then Angel Flores' translation in An Anthology of Medieval Lyrics. first two in insular minuscule, third in uncial.

#guillaume de poitiers#guillaume d'aquitaine#guilhem de poitiers#ab la dolchor del temps novel#provençal#occitan#troubadour#calligraphy#insular minuscule#uncial

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letture medievali N. 2: Guilhem de Peitèus, Ab la douzor del temps novel

Dopo Farai un vers de dreit nient, propongo un’altra canzone di Guglielmo d’Aquitania, unanimemente considerata una delle più belle e delle più rappresentative liriche occitaniche. Al suo interno compaiono, infatti, alcuni di quelli che diventeranno i temi tipici della tradizione trobadorica, ma gran parte della sua fortuna è dovuta all’immagine, icastica ed indimenticabile, che racchiude in sé tutto il senso del componimento, talmente romantica che, se la gente avesse una seppur minima idea della letteratura medievale, sarebbe una di quelle citazioni, magari riportata su una pagina ingiallita, che i più sono soliti condividere a caso su Facebook.

Tra i motivi che diverranno ricorrenti in questo tipo di poesia vanno senza dubbio ricordati l’esordio primaverile (la cosiddetta reverdie), cioè la rinascita della natura all’arrivo della bella stagione che risveglia i sensi, di uomini e animali, e, di conseguenza, il canto d’amore, e la sovrapposizione a questo tema amoroso di immagini e simboli feudali. La donna amata è, infatti, per i trovatori signore, al maschile (midons). In questa canzone alla sfera feudale rimandano le immagini del messaggero e del sigillo, del mantello e del coltello, in questi ultimi casi con sfumature erotiche neanche troppo velate, come ci si aspetta dal buon Guglielmo (per un breve profilo si rimanda sempre al post della settimana scorsa).

L’immagine che è al centro della poesia (nella terza di cinque coblas) ne condensa, si diceva, con mirabile essenzialità il messaggio. Si tratta del biancospino, pianta ricorrente nella poesia medievale, specialmente nei generi di ascendenza popolare (albas, pastorelle, chansons de toile...), e legata al folklore soprattutto di ambito matrimoniale o comunque erotico. Nella canzone di Guglielmo, il ramo di questo arbusto, che resiste tutta la notte al freddo e al gelo fino al sorgere del sole, diviene simbolo dell’amore invincibile che lega il poeta all’amata, capace sempre di trionfare nonostante occasionali difficoltà. I due, infatti, a quanto sembra, hanno litigato, lui, al solito, si dispera e soffre dell'allontanamento, ma ritrova prontamente la speranza, al ricordo di una precedente rottura ricomposta, di riconciliarsi ancora con l’amata. Spera, dunque, che anche il loro amore, proprio come il biancospino, passi la notte fredda ed umida per essere nuovamente riscaldato dai raggi del sole, nonostante quello che abbiano potuto dire i soliti lauzengiers, i malparlieri, gli eterni nemici degli amanti delle canzoni (sempre se a loro va riferita l’ultima cobla di senso molto discusso).

I.

Ab la douzor del temps novel

Fueillon li bosc, e li auzel

Chanton chascus en lor lati

Segon lo vers del novel chan:

adoncs estai ben q’on s’aizi

De zo don hom a plus talan.

II.

De lai don plus m’es bon e bel

No·m ve messatgers ni sagel,

Don mos cors non dorm ni non ri

E no m’en auz traire enan

Tro que eu sapcha ben de fi

S’el’es aissi con ieu deman.

III.

La nostr’amor vai enaissi

Con la branca de l’albespi

Qu’estai sobre l’arbr’entrenan

La noig, a la ploi’e al giel,

Tro l’endeman, qe·l sol s’espan

Per la fueilla vert enl ramel.

IV.

Anqar mi membra d’un mati

Qe nos fezem de guerra fi

E qe·m donet un don tan gran,

Sa drudari’ e son anel:

Anqar mi lais Dieus viure tan

Q’aia mas manz sotz son mantel!

V.

Q’ieu non ai soing d’estraing lati

Qe·m parta de mon Bon Vezi,

Q’eu sai de paraulas con van

Ab un breu sermon qi s’espel:

Qe tal se van d’amor gaban;

Nos n’avem la pessa e·l coutel!

Traduzione

I.

Con la dolcezza del tempo novello

fogliano i boschi e gli uccelli

cantano ciascuno in suo latino

secondo la melodia del canto nuovo:

allora sta bene che si goda

di ciò di cui si ha più talento.

II.

Da là dove mi è più buon e bello

non viene messaggero né sigillo,

per cui non dormo e non rido

e non oso farmi avanti

finché io non sappia bene dell’accordo

se è così come io domando.

III.

Il nostro amore va così

come il ramo del biancospino

che sta ritto sopra l’albero

la notte, alla pioggia e al gelo,

fino all’indomani, quando il sole si spande

per il verde fogliame sul ramo.

IV.

Ancora mi ricordo di un mattino

quando noi facemmo di una guerra pace

e mi donò un dono tanto grande,

in pegno d’amore il suo anello:

ancora mi lasci Dio vivere tanto

che io abbia le mie mani sotto il suo mantello!

V.

Io non mi curo che la chiacchiera di estranei

mi separi dal mio Buon Vicino,

ché io so come vanno le parole

per un breve detto che così dice:

alcuni si vanno d’amore vantando;

noi ne abbiamo le carne e il coltello.

NOTE

Il testo originale è tratto da Gambino F., “Guglielmo di Poitiers: Ab la douzor del temps novel”, «Lecturae tropatorum», III, 2010. La traduzione è invece mia.

8. No·m ve: così la Gambino, altri editori accolgono la lezione non vei (non vedo).

11. De fi: intendo con lo stesso senso dell’altra lezione de la fi e non seguo la Gambino che intende l’espressione come una locuzione avverbiale (con certezza), perché, anche se «in antico francese sono numerosi gli esempi dell’espressione costruita con il verbo saveir», «in antico occitano è possibile citare solo “aug dir tot de fi”» di Bertan de Born.

12. S’el’es: per come intendo il v. 11 leggo qui un pronome femminile e non neutro (el) come la Gambino.

15. Entrenan: il passo è problematico e le scelte degli editori sono molteplici: 1) en tremblan (tremando) da tremblar (<TREMULARE); 2) en treman (tremando) da tremar non attestato; 3) creman (che arde [per il freddo]); 4) entrenan (diritto, in piedi, verso l’alto).

26. Bon Vezi: senhal della donna amata.

30. Pessa: è il pezzo di carne o di pane, ma può anche indicare il pezzo di terreno dato in feudo al vassallo dal signore. In genere l’espressione viene intesa dagli editori nel senso di “avere l’intero godimento”.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ou Amor Salutar (Amor que consola), que também significa "Saudações Amor" em occitano. Como também entender "love letter", lit. "greeting" em inglês, um cumprimento numa carta de amor. Salut também é "oi" em francês.

O Salut D'Amor foram poemas líricos occitanas dos trovadores, escritos como uma carta de um amante para outro que dariam num dos elementos na tradição do amor cortês, que por sua vez as suas origens vieram de influências dos cátaros, dos árabes, e entre outros. Mas o Salut não é tratado como um gênero por gramáticos occitanos medievais, os trovadores apenas copiaram o estilo de músicas occitanas para o francês antigo. Estruturalmente muitas vezes os versos eram encontradas em octossílabos com rimas dísticas.

“Quem ousaria fazer leis aos amantes, visto que o amor, por si só, é uma lei maior?” Boécio

A Arte de Compor ao Encontro do Amor

As trobairises (singular: trobairitz) foram trovadores femininos occitanos dos séculos XII e XIII, ativos de cerca de 1170 a aproximadamente 1260. A palavra trobairitz foi usada pela primeira vez no Romance de Flamenca, do século 13. A palavra vem do Provençal de Trobar, o significado literal de "para encontrar", e o significado técnico de que é "para compor". São excepcionais na história musical como as primeiras compositoras conhecidas da música secular ocidental; Todas as composições femininas conhecidas anteriormente escreveram música sagrada. As trobairitz faziam parte da sociedade cortesana, ao contrário de suas colegas de classe baixa, as joglaressas; embora os trovadores às vezes venham de origens humildes. As trobairitz mais importantes são Alamanda de Castelnau, Azalais de Porcairagues, Maria de Ventadorn, Tibores, Castelloza, Garsenda de Proença, Gormonda de Monpeslier e Comtessa de Diá.

Ao longo do século 13, as mulheres da corte deveriam poder cantar, tocar instrumentos e escrever jocs partis, ou partimen (um debate ou diálogo na forma de um poema. De acordo com Guilhem Molinier, autor de Las lees d'Amors, um tratado do século XIII sobre como escrever poesia ao estilo dos trovadores. E graças à Leys de Amors, culminou através do estabelecimento de um sistema de codificação como nenhuma outra língua Europa tinha feito antes). O cultivo dessas habilidades femininas pode ter levado aos escritos de trobairitz.

A trobairitz também pode ter surgido devido ao poder que as mulheres realizaram no sul da França durante os séculos XII e XIII. As mulheres tinham muito mais controle sobre a propriedade da terra, e a sociedade occitana era muito mais aceitante das mulheres do que as outras sociedades da época. Há dificuldade em rotular a trobairitz como amadoras ou profissionais. A distinção entre esses dois papéis foi complicado na era medieval, já que os profissionais eram geralmente de classe baixa, e os amadores tiveram tanto tempo como profissionais para se dedicar ao seu ofício. Joglaresse eram compositores profissionais de classe baixa muito menos respeitadas do que a trobairitz.

Ambos os trovadores e trobairitz escreveu sobre fin'amor ("amor gentil"), ou o amor cortês. As mulheres eram, em geral, o sujeito dos escritos de trovadores, no entanto: "Nenhum outro grupo de poetas dá às mulheres uma definição tão exaltada dentro de um contexto de supressão tão estreitamente circunscrito". A trobairitz escreveu nos gêneros canso (canção em estrofes) e tenso (poema de debate). Além de cansos e tensos, trobairitz também escreveu sirventes (poemas políticos), planh (lamento), salut d 'amor (uma carta de amor não de forma estratificada), alba (músicas do alvorecer) e balada (músicas de dança). A julgar pelo que sobrevive hoje, a trobairitz não escreveu nenhuma música de pastorelas ou malmariee, ao contrário de seus colegas trovadores. Além disso, de acordo com a tradição trovadoresca, a trobairitz intimamente ligou a ação do canto à ação amorosa.

Occitania é de onde trouxe o movimento das Cortes de imponente Amor Poitiers, Narbonne, Toulouse. Foi lá que as mulheres inteligentes e cultas ficaram satisfeitas em manter os seus trovadores se tornando protetores. E embora o homem occitano do século XII não era totalmente analfabeto e cultivou o gosto pela poesia, música e proezas, os jogos terão completamente um ganho quando essas mulheres influentes e educadas têm os homens que viviam em torno delas para participar de seus gostos.

"Você é a árvore e ramo onde a fruta madura de alegria."

0 notes

Text

The Three Destinations of the Medieval Pilgrim

By April Munday In the Middle Ages the top three destinations for pilgrims were Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela, in that order of importance. For the English, a pilgrimage abroad was never an easy thing to undertake and wars, thieves and bandits made it even more difficult.

St James the Great by Georges de la Tour

Jerusalem and Rome were top of the list for obvious reasons, but why was Compostela the third? Compostela is in Galicia, in northern Spain, and is a little less than fifty miles from Cape Finisterre, which the Romans thought was the edge of the world. The cathedral at Compostela is said to contain the remains of St James the Great, believed to be the first apostle to be martyred. One of the legends about St James is that he preached in Spain, before returning to Judea where he was martyred by being beheaded on the orders of Herod Agrippa in 44 AD. His remains were then transported from Judea to Spain in a rudderless, stone boat guided by angels. Santiago is the Galician form of St James. There were earlier churches on the site, but the current cathedral of St James was built between 1060 and 1140. Technically a pilgrim's journey began with the first step and then he (or she) could follow whichever route he wanted to the shrine which was his goal. In reality this was not very practical, since he needed to pass through somewhere where he could get food fairly often. As long as he was on a route frequented by merchants, this was not a problem, as there were inns at regular intervals along the way. Where the routes did not coincide the pilgrim could expect hospitality, or at least some kind of shelter for the night, from monasteries. Where there were neither inns nor monasteries there were often hospices. These were built by monks to assist pilgrims and there was a great need for them on the routes to Compostela. Most of these hospices were built by the Cluniacs. There were four main routes across France and pilgrims from the north, east and south gathered at the four towns where those routes started and travelled, usually in the company of others, into Spain. Each route started in and went through towns containing important shrines. The route that started in Paris went through Orléans, Tours, Poitiers, St-Jean-d'Angély, Saintes and Bordeaux. The one from Vézelay (where the supposed tombs of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus were to be found) went through Bourges, St-Léonard-de-Noblat, Limoges and Périgueux. From Le Puy the route went through Conques and Moissac, before joining the first two routes at St-Jean-Pied-de-port at the foot of the Pyrenees. The final route went from Arles through St-Gilles, St-Guilhem-le-Désert, Castres, Toulouse, Auch, Oloron, the Somport Pass and Jaca before joining the other routes in Puente la Reina. This meant that English pilgrims were presented with a huge amount of choice, depending on where they crossed the Channel. It was possible to sail from Bristol to La Coruña which meant a walk of approximately forty miles to get to Compostela once they were in Spain. This might sound like an easy option, but the Bay of Biscay was known for its storms and there was also the possibility of falling prey to wreckers or pirates (English, French or Castilian). It would entail travelling on a small ship for at least five days, usually much longer, in cramped and uncertain conditions. Generally passengers each had enough room to stretch out and sleep, but no more. If a longer walk was required, the pilgrim could sail to Bordeaux which would allow him to complete his pilgrimage without going into territory held directly by the king of France, which might be the safest route during times of tension, if not outright war, with France. During more peaceful times, a shorter trip from Dover to Dieppe or Plymouth to Brittany might be preferred, which would mean the pilgrim walking the length of France before reaching Spain. If they sailed from Dover, they probably spent a night in the Pilgrim's Hall at Aylesford Friary on their way through Kent.

The Pilgrims' Hall

It took about six months to walk from Paris to Compostela and back again. Pilgrims travelling overland faced wolves, bandits, fever, rivers that were not easy to cross, mountains and, in the early day, Moors. On the plus side, there were plenty of shrines along the route where they might pray and see miracles.

From the 1370s on most English pilgrims travelled by sea to Galicia since they were not permitted to cross Castile without the permission of the king of France. Since the Hundred Years' War was going through one of its more violent patches at this time, that permission was never going to be forthcoming. As the French gained more and more territory that had belonged to the English crown, English pilgrims had little choice but to travel by sea.

Pilgrims travelled with the hope of seeing, or touching, the relic of the saint. Some even broke or bit off part of the relic to take home with them. Clerics were particularly prone to this. This led to the construction of shrines and reliquaries to protect relics, but the pilgrims merely tried to take back bits of the shrines and reliquaries as souvenirs.

At most shrines pilgrims could leave offerings of wax models which reflected the reason for their pilgrimage. This was not permitted when they reached Santiago. Only money and jewellery were acceptable offerings.

The eleventh century was a time of peace across Europe, allowing pilgrims to travel overland even to Jerusalem. It was almost a golden age of pilgrimage. Hospices were built along the routes to Santiago and bridges were repaired. It is said that around half a million people a year went to Compostela in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

There were pilgrim guidebooks, describing the route to be followed. The earliest known guidebook covering the route to Compostela was written by Aymery Picaud, a French monk, in the twelfth century. He detailed the stages of the journey starting from the Gascon side of the Pyrenees. The book recommends shrines to be visited and describes things to be seen along the way. There is also a description of the cathedral which is the object of the journey. For good measure he tells some precautionary tales about the fates of people who tried to hinder or did not help pilgrims on their way to Santiago. A weaver, for example, did not give bread to a pilgrim and later found the cloth he had been working on torn in half and thrown on the ground. Picaud and, presumably, the weaver, attributed the act of vengeance to St James. We, however, might suspect that the perpetrator was someone other than the saint.

Travelling to Compostela from England was not cheap. Although there were hospices where he could expect to be accommodated for free, the pilgrim needed enough money to buy food, and to pay for accommodation in inns. A pilgrim could beg or work in order to gain the money, but most preferred to leave home with the requisite amount.

Once he reached Compostela, the pilgrim would purchase his cockleshell token, attach it to his tunic or hat (as modelled by St James in the picture at the top of the post), and return home.

Images:

Portrait of St James the Great by Georges de la Tour in the Public Domain

Pilgrim's Hall, Aylesford – Author's Own

References:

The Age of Pilgrimage – Jonathan Sumption

Pilgrimages to St James of Compostela from the British Isles during the Middle Ages – Robert Brian Tate

Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe – Peter Spufford

~~~~~~~~~~

April Munday lives in Hampshire and has published a number of novels set in the fourteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They include Beloved Besieged, The Traitor's Daughter, His Ransom, The Winter Love and the Regency Spies Trilogy. They can be purchased from Amazon

Her blog 'A Writer's Perspective' (www.aprilmunday.wordpress.com) arose from her research for her novels and is a repository of things that she has found to be of interest. She can also be found on Twitter.

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Text

Letture medievali N. 1: Guilhem de Peitèus, Farai un vèrs de dreit nient

Ho deciso, anche se, come per tutte le cose che imprendo, non so quanto durerà, di condividere regolarmente qualcuna delle mie letture medievali, in particolare dei testi galloromanzi in lingua d’oc e d’oïl, che sono la mia grande passione (nel corso del quinquennio universitario ho accumulato 42 CFU di filologia romanza juste parce que).

Dopo breve dibattito interiore con prosopopea dei concetti astratti in perfetto stile da romanzo medievale, ho deciso di incominciare dal primo di tutti, Guglielmo d’Aquitania, e di accantonare per il momento Chrétien di Troyes, il primo del mio cuore (posizione condivisa ex aequo con Proust), su cui mi riservo di tornare quando avrò più tempo. Considerando comunque che Guglielmo è il nonno di Eleonora d’Aquitania, madre di Maria di Champagne, protettrice di Chrétien, tutto torna.

Gugliemo VII conte di Poitiers e IX duca d’Aquitania (1071-1126) è considerato non soltanto il primo trovatore, ma anche il primo poeta in volgare dell’Europa medievale. Nominalmente vassallo del re di Francia, era di lui più potente (non che al tempo ci volesse molto).

Avventuriero senza scrupoli e gran seduttore, fu due volte sposato e due volte scomunicato per le violazioni del diritto ecclesiastico e gli scandali della sua vita privata. Per dire, fu anche accusato, ci dice Guglielmo di Malmesbury, di aver voluto fondare un monastero di prostitute (abbatiam pellicum).

La sua vida* lo presenta in questo modo:

Lo coms de Peitieus si fo uns dels majors cortes del mon e dels majors trichadors de dompnas, e bons cavalliers d’armas e larcs de dompnejar; e saup ben trobar e cantar. Et anet lonc temps per lo mon per enganar las domnas.

Il conte di Poitiers fu uno degli uomini più cortesi del mondo e uno dei più grandi ingannatori di donne, e fu buon cavaliere d’arme e generoso nel corteggiare, e seppe ben comporre e cantare. E se ne andò lungo tempo per il mondo ad ingannare le donne.

Tra le tante cose, tentò anche una sfortunata crociata in Terrasanta (1101) e di annettere più volte Tolosa senza successo.

*Le vidas sono delle brevi notizie biografiche, databili a partire dal XIII secolo, composte su un centinaio di trovatori. Le razos, invece, riportano le circostanze di composizione delle canzoni.

Farai un vèrs de dreit nient

Della decina di canzoni che ci sono giunte sotto il nome di Guglielmo ho scelto Farai un vèrs de dreit nient perché adoro la prima cobla*, soprattutto per la storia del cavallo, che forse potrebbe pure intendersi come allusione erotica, conoscendo il soggetto.

La critica, al solito, si è sbizzarrita e ha dato della canzone le interpretazioni più varie, da quella che la vuole una meditazione filosofica sul niente a quella che la vede come visione onirica, o forse, semplicemente, prendendo per buone, come faceva J. Duggan, le parole dello stesso poeta, non vuole dire proprio nulla.

Ricordo che le canzoni erano pensate per essere cantate su un accompagnamento musicale.

*Le coblas sono le strofe, in genere cinque o sei, che compongono la canzone, chiusa da una tornada, che equivale al congedo delle canzoni italiane.

I.

Farai un vèrs de dreit nient:

Non èr de mi ni d’autra gent,

Non èr d’amor ni de jovent,

Ni de ren au,

Qu’enans fo trobats en dorment

Sobre chevau.

II.

Non sai en qual’ora⸳m fui nats,

Non soi alegres ni irats,

Non soi estranhs ni soi privats

Ni non puèsc au,

Qu’enaissí fui de nuèit fadats

Sobr’un puèg au(t).

III.

Non sai quora⸳m fui endormits,

Ni quora⸳m velh, s’om non m’o ditz;

Per pauc non m’es lo còr partits

D’un dòl corau:

E non m’o prètz una fromits,

Per sant Marçau!

IV.

Malauts soi e cre mi morir:

E ren non sai mas quand n’aug dir.

Mètge querrai al mieu albir,

E no⸳m sai tau;

Bon mètges èr, si⸳m pòt guerir,

Mor non, s’amau.

V.

Amig’ai ieu, non sai qui s’es:

Qu’anc non la vi, si m’ajut fes:

Ni⸳m fes que⸳m plassa ni que⸳m pes,

Ni non m’en cau:

Qu’anc non ac Normand ni Francés

Dins mon ostau.

VI.

Anc non la vi et am la fòrt;

Anc non n’aic dreit ni no⸳m fes tòrt;

Quand non la vei, ben m’en deport;

No⸳m prètz un jau:

Qu’ie⸳n sai gençor e belasor

E que mas vau.

VII.

Non sai lo luèc ves ont s’està,

Si es en puèg o es en pla(n);

Non aus dire lo tòrt que m’a,

Abans m’en cau;

E pesa⸳m ben car çai rema(n)

Per aitan vau.

VIII.

Fait ai lo vèrs, non sai de qui;

E tramentrai lo a celui

Quel lo⸳m trametrà per autrui.

Envers Peitau,

Que⸳m tramesés del sieu estui

La contraclau.

Traduzione

I.

Farò una canzone su un bel niente:

Non sarà su di me né su altra gente,

Non sarà sull’amore né sulla giovinezza,

Né su nient’altro,

Ché prima fu composta mentre dormivo

Sopra un cavallo.

II.

Non so a che ora fui nato,

Non sono allegro né triste,

Non sono straniero né del posto

E non posso farci niente,

Ché così fui di notte stregato

Sopra un alto poggio.

III.

Non so a che ora mi fui addormentato,

Né a che ora sto sveglio, se nessuno me lo dice;

Per poco non mi si è il cuore spezzato

Di un dolore mortale:

E non me ne importa una cicca,

Per san Marziale!

IV.

Malato sono e credo di morire:

E nient’altro so più di quanto sento dire.

Un medico cercherò a mio piacimento,

Ma tale non ne conosco;

Buon medico sarà, se mi può guarire,

Ma no, se peggioro.

V.

Ho un’amica, non so chi sia:

Ché mai non la vidi, in fede mia;

Niente mi fece che mi piaccia o che mi pesi,

E non me ne importa:

Ché mai fu normanno o francese

In casa mia.

VI.

Mai non la vidi ma la amo forte;

Mai ne ebbi diritto né mi fece torto;

Quando non la vedo, me ne diverto bene;

Non me ne importa un fico:

Ché io ne conosco una più nobile e bella

E che vale di più.

VII.

Non conosco il luogo in cui dimori,

Se è in montagna o in pianura;

Non oso dire il torto che ha nei miei confronti,

Piuttosto sto zitto;

E mi pesa molto rimanere qui,

Perciò me ne vado.

VIII.

Ho finito la canzone, non so su chi;

E la manderò a colui

Che la manderà per un altro

Verso il Poitou,

Affinché mi mandi del suo astuccio

La controchiave.

NOTE

Il testo originale è tratto da Fabre Paul, Anthologie des troubadours: XIIe-XIVe siècle, Paradigme, Orléans, 2010, che si distingue per i testi modernizzati nella grafia, che hanno, se non altro, il vantaggio di poter essere più agevolmente letti dai non specialisti che vi si volessero provare. Il motivo è presto detto: si tratta dell’edizione che al momento ho a portata di mano (criterio molto filologico, direi…). La traduzione, invece, è tutta mia e non ha alcuna pretesa di artisticità (non rispetta né la metrica né le rime dell’originale), anche perché l’ho portata a termine in una mezz’oretta.

Ho scelto di tradurre con “canzone” il vers dell’originale, perché con questo termine si designava fino alla fine del XII secolo la forma poetica poi più comunemente conosciuta come canso. Beltrami traduce con “versus”, che è il genere poetico paraliturgico medio-latino da cui il vers provenzale etimologicamente deriva, per il fatto che la canzone di Guglielmo ha probabilmente un valore dissacrante nei confronti della poesia religiosa.

La penultima cobla non è mantenuta da tutti gli editori. In effetti non aggiunge molto al testo.

1 note

·

View note