#gregory rabassa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A run-on sentence on Gabriel García Márquez's delirious novel The Autumn of the Patriarch

Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch isn’t so much a novel as it is a delirium, a swamp fever, a sun-bleached hallucination stretched across centuries, a beast that coils and uncoils, bloated with its own rot, a thing that does not begin or end but only festers, looping back on itself in great, heaving tides of unpunctuated or undepunctuated or mispunctuated thought, García…

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez, translated from Spanish by Gregory Rabassa, cover design by Alain Gauthier, this edition printed 1988.

#chronicle of a death foretold#crónica de una muerte anunciada#gabriel garcia marquez#gregory rabassa#alain gauthier#vintage book covers#eyeball bouquet

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

― Gabriel García Márquez, Chronicle of a Death Foretold (translated by Gregory Rabassa)

#quotes#literature#classic literature#translated literature#gabriel garcia marquez#chronicle of a death foretold

879 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's time to choose our book for August, and the theme is Translated Books! Feel free to vote even if you’re not part of book club; we’ll be voting amongst the top three in our Discord. If you’d like to join the book club, send me a message and I’ll give you the link! Book summaries are under the cut!

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

Here we meet fifteen-year-old runaway Kafka Tamura and the elderly Nakata, who is drawn to Kafka for reasons that he cannot fathom. As their paths converge, acclaimed author Haruki Murakami enfolds readers in a world where cats talk, fish fall from the sky, and spirits slip out of their bodies to make love or commit murder, in what is a truly remarkable journey.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, Gregory Rabassa (Translator)

One of the most influential works of our time, One Hundred Years of Solitude remains a dazzling and original achievement by the masterful Gabriel Carcia Marquez, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of the rice and fall, birth and death of the mythical town of Macondo through the history of the Buendiá family. Inventive, amusing, magnetic, sad and alive with unforgettable men and women—brimming with truth, compassion, and a lyrical magic that strikes the soul—this novel is a masterpiece in the art of fiction.

The Dallergut Dream Department Store: A Novel by Miye Lee, Sandy Joosun Lee (Translator)

What if there was a store that sold dreams? Which would you buy? And who might you become when you wake up?

In a mysterious town hidden in our collective subconscious there’s a department store that sells dreams. Day and night, visitors both human and animal shuffle in to purchase their latest adventure. Each floor specializes in a specific type of dream: childhood memories, food dreams, ice skating, dreams of stardom. Flying dreams are almost always sold out. Some seek dreams of loved ones who have died.

For Penny, an enthusiastic new hire, working at Dallergut is the opportunity of a lifetime. As she uncovers the workings of this whimsical world, she bonds with a cast of unforgettable characters, including Dallergut, the flamboyant and wise owner, Babynap Rockabye, a famous dream designer, Maxim, a nightmare producer, and the many customers who dream to heal, dream to grow, and dream to flourish.

The Full Moon Coffee Shop by Mai Mochizuki, Jesse Kirkwood (Translator)

In Japan, cats are a symbol of good luck. As the myth goes, if you are kind to them, they’ll one day return the favor. And if you are kind to the right cat, you might just find yourself invited to a mysterious coffee shop under a glittering Kyoto moon.

This particular coffee shop is like no other. It has no fixed location, no fixed hours, and it seemingly appears at random.

It’s also run by talking cats.

While customers at the Full Moon Coffee Shop partake in cakes and coffees and teas, the cats also consult their star charts, offering cryptic wisdom, and letting them know where their lives veered off course.

Every person who visits the shop has been feeling more than a little lost. For a down-on-her-luck screenwriter, a romantically stuck movie director, a hopeful hairstylist, and a technologically challenged website designer, the coffee shop’s feline guides will set them back on their fated paths. For there is a very special reason the shop appeared to each of them…

A Magical Girl Retires: A Novel by Park Seolyeon, Anton Hur (Translator)

Twenty-nine, depressed, and drowning in credit card debt after losing her job during the pandemic, a millennial woman decides to end her troubles by jumping off Seoul’s Mapo Bridge.

But her suicide attempt is interrupted by a girl dressed all in white—her guardian angel. Ah Roa is a clairvoyant magical girl on a mission to find the greatest magical girl of all time. And our protagonist just may be that special someone.

But the young woman’s initial excitement turns to frustration when she learns being a magical girl in real life is much different than how it’s portrayed in stories. It isn’t just destiny—it’s work. Magical girls go to job fairs, join trade unions, attend classes. And for this magical girl there are no special powers and no great perks, and despite being magical, she still battles with low self-esteem. Her magic wand…is a credit card—which she must use to defeat a terrifying threat that isn’t a monster or an intergalactic war. It’s global climate change. Because magical girls need to think about sustainability, too.

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop by Satoshi Yagisawa, Eric Ozawa (Translator)

Twenty-five-year-old Takako has enjoyed a relatively easy existence—until the day her boyfriend Hideaki, the man she expected to wed, casually announces he’s been cheating on her and is marrying the other woman. Suddenly, Takako’s life is in freefall. She loses her job, her friends, and her acquaintances, and spirals into a deep depression. In the depths of her despair, she receives a call from her distant uncle Satoru.

An unusual man who has always pursued something of an unconventional life, especially after his wife Momoko left him out of the blue five years earlier, Satoru runs a second-hand bookshop in Jimbocho, Tokyo’s famous book district. Takako once looked down upon Satoru’s life. Now, she reluctantly accepts his offer of the tiny room above the bookshop rent-free in exchange for helping out at the store. The move is temporary, until she can get back on her feet. But in the months that follow, Takako surprises herself when she develops a passion for Japanese literature, becomes a regular at a local coffee shop where she makes new friends, and eventually meets a young editor from a nearby publishing house who’s going through his own messy breakup.

But just as she begins to find joy again, Hideaki reappears, forcing Takako to rely once again on her uncle, whose own life has begun to unravel. Together, these seeming opposites work to understand each other and themselves as they continue to share the wisdom they’ve gained in the bookshop.

The Kamogawa Food Detectives by Hisashi Kashiwai, Jesse Kirkwood (Translator)

What’s the one dish you’d do anything to taste just one more time?

Down a quiet backstreet in Kyoto exists a very special restaurant. Run by Koishi Kamogawa and her father Nagare, the Kamogawa Diner serves up deliciously extravagant meals. But that’s not the main reason customers stop by…

The father-daughter duo are ‘food detectives’. Through ingenious investigations, they are able to recreate dishes from a person’s treasured memories – dishes that may well hold the keys to their forgotten past and future happiness. The restaurant of lost recipes provides a link to vanished moments, creating a present full of possibility.

The Days of the Deer by Liliana Bodoc

It is known that the strangers will sail from some part of the Ancient Lands and will cross the Yentru Sea. All our predictions and sacred books clearly say the same thing. The rest is all shadows. Shadows that prevent us from seeing the faces of those who are coming.

In the House of Stars, the Astronomers of the Open Air read contradictory omens. A fleet is coming to the shores of the Remote Realm. But are these the long-awaited Northmen, returned triumphant from the war in the Ancient Lands? Or the emissaries of the Son of Death come to wage a last battle against life itself? From every village of the seven tribes, a representative is called to a Great Council. One representative will not survive the journey. Some will be willing to sacrifice their lives, others their people, but one thing is certain: the era of light is at an end.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

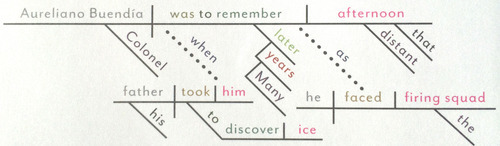

"Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

This opening line of Gabriel Garcia Márquez's novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, translated into English by Gregory Rabassa, is among the best known and most remarkable opening sentences in literary history.

#gabriel garcia marquez#one hundred years of solitude#literature#spanish literature#nobel prize#best literature

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

We’re not grown up yet, Lucía. It’s a virtue, but it costs a lot.

— Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch, trans. by Gregory Rabassa

#julio cortázar#hopscotch#adulthood#virtue#quoteoftheday#quotes#book quotes#classic literature#classic quotes#classics#classic lit#classic books#quotesdaily

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

—Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch (trans. Gregory Rabassa)

#rayllum#rayllumedit#storm motif#subset: salvation and destruction#quotes#my edits#graphics#multi#pining!callum#been sitting on this once since april 2021#feels organic feels right

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 2023 reading

Books:

Melissa Gira Grant, Playing The Whore: The Work Of Sex Work

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary tr. Eleanor Marx-Aveling

John Lahr, Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh: Tennessee Williams

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude tr. Gregory Rabassa

Sayaka Murata, Earthlings tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori

John Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

Tennessee Williams, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie

Tennessee Williams, Memoirs

Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire

Tennessee Williams, Suddenly Last Summer

Essays:

Paul Kincaid, On the Origins of Genre

Articles:

Alex Barasch, After "Barbie," Mattel Is Raiding Its Entire Toybox

Max Fox, Free the Children

Deepa Kumar, Imperialist Feminism

Terry Nguyen, The Diversity Elevator - On R.F. Kuang's Yellowface

Mandy Shunnarah, Olives, Climate Change, and Zionism

Ben Taub, The Titan Submersible Was "An Accident Waiting to Happen"

Short stories:

Sayaka Murata, A Clean Marriage tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori

Other:

Max Graves, What Happens Next

#reading#really short on essays/articles this month sorry gang. i spent 100% of my laptop time reading umineko

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Figured that now that I've got a bookblr, I should make a post about the Read the World Challenge I'm doing! I'm reading a book primarily set in every country, doing my best to focus on authors from said country, though I will read diaspora authors if that's not feasible. Also some of the books from early on were from diaspora authors because I was pulling from books I had already read; I'll likely read more books from those countries in the future if I can. I've got 52 countries so far, and I'll list the titles and countries under the cut

USA- Kindred by Octavia Butler- 5⭐️

Canada- The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline- 5⭐️

Trinidad and Tobago- The Lesson by Cadwell Turnbull- 3⭐️

Brazil- Where We Go From Here by Lucas Rocha trans by Larissa Helena- 5⭐️

Argentina- Tender is the Flesh by Augustina Bazterrica trans by Sarah Moses- 5⭐️

South Africa- The Prey of Gods by Nicky Drayden- 3⭐️

Nigeria- Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor- 4⭐️

Liberia- Dream Country by Shannon Gibney 5⭐️

France- Romance in Marseilles by Claude McKay- 2⭐️

UK- Watership Down by Richard Adams- 5⭐️

Ireland- Big Girl, Small Town by Michelle Gallen- 4⭐️

Qatar- Love from A to Z by SK Ali- 4⭐️

Iran- Darius the Great is Not Okay by Adib Khorram- 4⭐️

China- The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu trans by Ken Liu- 5⭐️

Taiwan- Loveboat, Taipei by Abigail Hing Wen- 4⭐️

Japan- Confessions by Kanae Minato trans by Stephen Snyder- 3.5⭐️

Norway- Survival Kit by AH Haga- 4.5⭐️

Germany- The Book Thief by Markus Zusak- 4.5⭐️

India- The Henna Artist by Alka Joshi- 4⭐️

South Korea- The Mermaid from Jeju by Sumi Hahn- 4⭐️

Colombia- One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez trans by Gregory Rabassa- 4⭐️

Ghana- Wife of the Gods by Kwei Quartey- 4⭐️

Turkey- 10 Minutes and 38 Seconds in This Strange World by Elif Shafak- 4⭐️

Russia- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy trans by Louise Maude- 4⭐️

Sierra Leone- The Memory of Love by Aminatta Forna- 4⭐️

Austria- The Wall by Marlen Haushofer trans by Shaun Whiteside- 5⭐️

Zimbabwe- Nervous Conditions by Tsiti Dangarembga- 5⭐️

Venezuela- It Would Be Night in Caracas by Karina Sainz Borgo trans by Elizabeth Bryer- 4⭐️

Chile- The House of Spirits by Isabel Allende trans by Magda Bogin- 5⭐️

Sri Lanka- Funny Boy by Shyam Selvadurai- 4⭐️

Singapore- How We Dissappeared by Jing-Jing Lee- 4.5⭐️

Malaysia- Queen of the Tiles by Hanna Alkaf- 3.5⭐️

Egypt- A Master of Djinn by P Djèlí Clark- 4.5⭐️

Sudan- Ghost Season by Fatin Abbas- 4.5⭐️

Antigua and Barbuda- At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid- 4⭐️

Ukraine- The Lost Year by Katherine Marsh- 5⭐️

Bahamas- Learning to Breathe by Janice Lynn Mather- 4⭐️

Cuba- The Black Cathedral by Marcial Gala trans by Anna Kushner- 4⭐️

Dominica- The Autobiography of My Mother by Jamaica Kincaid- 3⭐️

Bangladesh- Djinn City by Saad Z Hossain- 4⭐️

Mexico- Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia- 4⭐️

Jamaica- Here Comes the Sun by Nicole Dennis-Benn- 4⭐️

Vietnam- Dust Child by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai- 4.5⭐️

Australia- Too Much Lip by Melissa Lucashenko- 4⭐️

Israel- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa- 4.5⭐️

Palestine- Mornings in Jenin by Susan Abulhawa- 5⭐️

Costa Rica- Where There Was Fire by John Manuel Arias- 4.5⭐️

Uruguay- Cantoras by Carolina De Robertis- 5⭐️

Dominican Republic- Tentacle by Rita Indiana trans by Achy Obejas- 2.5⭐️

Republic of the Congo- Broken Glass by Alain Mabanckou trans by Helen Stevenson- 2⭐️

Czech Republic- The Spaceman of Bohemia by Jaroslav Kalfař- 2.5⭐️

Honduras- Turtles of the Midnight Moon by María José Fitzgerald- 4.5⭐️

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog about some February acquisitions

A weeks-long back-and-forth with a colleague about certain flavors of Modernist novels led to this colleague, a friend really, to come by my office with a stack of about 80 pages he’d printed, front and back, demanding that I take a look at some utter nonsense, probably the kind of nonsense I’d abide. This particular nonsense was a printed .pdf of Camilo José Cela’s 1988 novel Cristo versus…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Hundred Years of Solitude

by Gabriel Garcia Marquez; Translated by Gregory Rabassa

HRCYED Prompts Fulfilled:

1. Translation Challenge: Spanish 2. All the Adaptations: TV Show

Reading this book feels a little bit like reading a fever dream, and I mostly mean that as a compliment. The figurative and evocative language is so strong here, and the tone of the writing is so deliberate. Things are told somewhat chronologically, but we are constantly jumping back and forth between the present and the future, blurring the lines of reality just a bit. It very rarely gives discrete ages or timelines, making it feel like time blurs together as all the sudden the kids you were reading about twenty pages ago are now adults who are making bad decisions. (Nearly everybody in this book makes bad decisions.) It also employs the use of magical realism, further blurring lines and giving it a unique tone that, to me, feels a little bit like an impressionist painting in writing form.

The book tells the story of the Buendias family whose patriarch established the fictional town of Macondo. We follow many generations of the family over the course of about a century, and characters who are born in early pages die of old age by the end. The family is messy and incestuous and pretty much perpetually miserable, usually by means of their own making.

The main theme of the book is that of isolation. The town starts and ends isolated from the world. Nearly every character becomes withdrawn from the world and/or the rest of the family. The incest, while almost comically pervasive, serves to show the family turning in on itself, carrying forward a curse and rot that ends up being the family's downfall. The ending of this book was WILD and felt like a well-earned gut punch.

That said, in many ways, I feel like maybe I should have waited to read this book until I'd gotten my reading legs back under me a little more. I was impressed by it, intrigued by it, but I'm not sure how much I enjoyed it. A lot of times I sort of felt like the prose was washing over me rather than drawing me into the story. I think I attribute that more to me being an out-of-practice reader than any faults of the book, though. It's expertly done and I can see why it is a classic, but apart from the ending there weren't many moments that it really Connected with me. So if the review score seems low, that's the primary reason why! Maybe when I'm better read and smarter in the future I'll like it better.

I also cannot imagine how the hell they made this into a Netflix show. I don't know if I'm ready to re-experience this story again but I'm also morbidly curious to know how they managed to adapt it.

Final Rating: 3.75

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

― Gabriel García Márquez, Chronicle of a Death Foretold (translated by Gregory Rabassa)

#quotes#literature#classic literature#translated literature#gabriel garcia marquez#chronicle of a death foretold

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s something called time, Rocamadour, it’s like a bug that just keeps on walking. I can’t explain it to you because you’re so small, but what I mean is that Horacio will be back any minute now.

Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch (trans. Gregory Rabassa)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

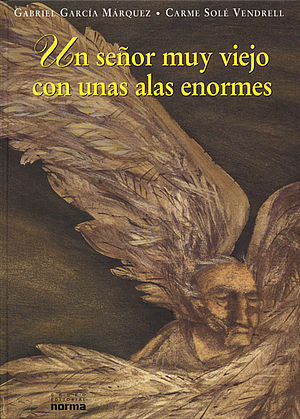

"He had to go very close to see that it was an old man, a very old man, lying face down in the mud, who, in spite of his tremendous efforts, couldn’t get up, impeded by his enormous wings."

"They both looked at the fallen body with a mute stupor. He was dressed like a ragpicker. There were only a few faded hairs left on his bald skull and very few teeth in his mouth, and his pitiful condition of a drenched great-grandfather took away any sense of grandeur he might have had. His huge buzzard wings, dirty and half-plucked, were forever entangled in the mud. They looked at him so long and so closely that Pelayo and Elisenda very soon overcame their surprise and in the end found him familiar. Then they dared speak to him, and he answered in an incomprehensible dialect with a strong sailor’s voice. That was how they skipped over the inconvenience of the wings and quite intelligently concluded that he was a lonely castaway from some foreign ship wrecked by the storm. And yet, they called in a neighbor woman who knew everything about life and death to see him, and all she needed was one look to show them their mistake."

“He’s an angel,” she told them. “He must have been coming for the child, but the poor fellow is so old that the rain knocked him down.”

- Gabriel García Márquez, translation by Gregory Rabassa.

Angel

Controversial artist Sun Yuan and Peng Yu create a hyper-realistic sculpture of a fallen angel. The piece shows an old woman who has fallen from grace. She also has feather-less wings on her back

The artists created the piece using silica gel, fiberglass, stainless steel and woven mesh which is pretty tame for the them. Sun and Peng have been known to use baby cadavers and human fat in a lot of their art. This peice is featured in Beijing

#gabriel marcia marquez#art#latinamerican writters#chinese art#controversial art#because of religion#angel#old angel#just trying to check#mostly an experiment#to see how my audience react

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Believing in what they call matter, believing in what they call spirit . . . considering human destiny as an economic problem or as a complete absurdity, the list is long, the choice is multiple.

— Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch, trans. by Gregory Rabassa

#julio cortázar#hopscotch#matter#spirit#destiny#life#life quotes#quoteoftheday#quotes#book quotes#classic literature#classic quotes#classics#classic lit#classic books

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

Gabriel García Márquez (trans. Gregory Rabassa) One Hundred Years of Solitude 1967

1 note

·

View note