#gq russia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Irina Shayk by David Roemer

- GQ Russia, August 2013

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gretha Cavazzoni featured in Gretha Cavazzoni // GQ Russia May 2001

#fashion#vintage 90s#vintage#60s 70s 80s 90s#vintage fashion#90s#runway#90s fashion#90s nostalgia#2000s fashion#gq russia#gq#gq magazine#gretha cavazzoni

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mitchell Slaggert | GQ Russia (2019)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

GQ Russia Photoshoot(2010) pics…

#GQ Russia Photoshoot(2010)#jacob benjamin gyllenhaal#jake gyllenhaal#jacob gyllenhaal#fluffy boy post#love his fluffy beard#fluffy beard#fluffy

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

CILLIAN MURPHY, SO DEVASTATING, HE PASSES OUT.

SIR CREATIVELY MID, SAYS WHAT?

"CILLIAN IS ART! HE IS ART. LOOK AT HIM, TWIRLING! OMG!" 😭

'DU JOUR! ART, BLAH, BLAH, ART.'

MAN! THAT GQ LIGHTING IS TRULY MAGICAL!

TWIRL, GIRL! TWIRL! PAPA NEEDS A NEW VALENTINO SUIT.

DU JOUR! DU JOUR!

THIS ACTOR BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE WEF SOLAR CULT!

#Cillian Murphy#TWIRL GIRL TWIRL!#GO IRISH!#Oppenheimer#WEF Dedication#One World Government YIPPEE!#Russia#Israel#Iran#Hamas#Argentina#Canada#SAG-AFTRA#Oscars 2024#NFL MVP PICK#GQ Magazine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

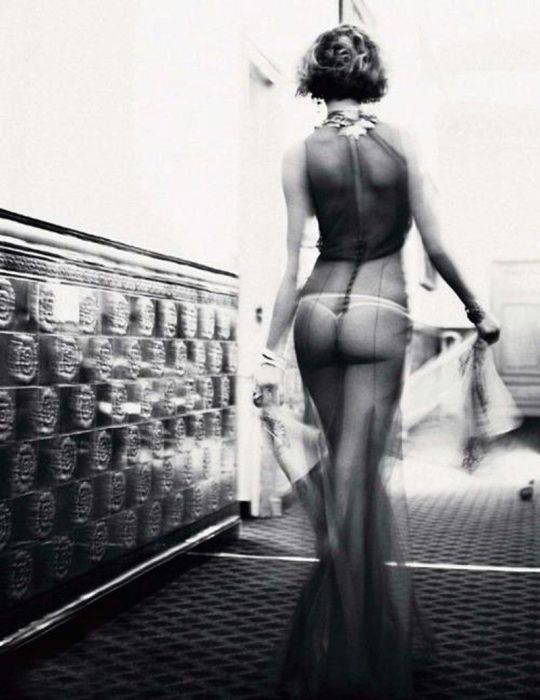

Eva Riccobono by Ellen Von Unwerth for GQ Russia, January 2011

#eva riccobono#ellen von unwerth#photography#fashion photography#fashion#fashion editorial#black and white#fashion magazine#beauty

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Cover

* * * *

In 2016, the Kremlin was ecstatic after Donald Trump’s victory. I watched the reaction coming from Russia that night as members of the Duma congratulated each other the moment Hillary Clinton conceded, with Russian officials and state media openly boasting that they had “elected one of their own.” Fast forward to 2024, and the tone has dramatically shifted. Despite Russia’s numerous covert operations to facilitate Trump’s re-election bid, the post-election atmosphere is now filled with mockery, veiled threats, praise, and ominous warnings—marking a stark contrast to the earlier jubilation.

Shortly after Trump’s win, Russia 1 aired explicit and practically nude photos of Melania Trump from her modeling career. During a prime-time segment on the propaganda show 60 Minutes, hosts Olga Skabeeva and Yevgeny Popov showcased images from a 2000 GQ shoot, with Popov sneering, “It’s as though the editors of the magazine knew something in advance about her future.” Skabeeva struggled to suppress laughter, and the whole spectacle felt like a calculated dig—or perhaps a reminder of vulnerabilities. Nikolai Patrushev, a senior Kremlin official and close ally of Vladimir Putin, made a series of strikingly ominous remarks about Donald Trump following his election victory.

In an interview, Patrushev emphasized that Trump is “obliged” to follow through on promises made during his campaign. “To achieve success in the elections, Donald Trump relied on certain forces to which he has corresponding obligations. And as a responsible person, he will be obliged to fulfill them,” Patrushev stated.

He added, “During the pre-election period, he made many statements to attract voters to his side, who ultimately voted against the destructive foreign and domestic policies pursued by the current U.S. presidential administration. But the election campaign is over, and in January 2025, it will be time for the specific actions of the elected president. It is known that election promises in the United States can often diverge from subsequent actions.”

[Olga Lautman]

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

It’s fairly obvious that movie ewan is filming is wuthering heights and everyone is just coping that it’s another film. The music video was filmed mid Jan and the filming for the movie started after that, that only leaves wuthering heights. Ewans hair was bleached until the GQ event and if he was a part of the other high profile movies being filmed like anemone which started filming in October he would have had it dyed back to its natural colour earlier.

There is a small chance of him playing Hareton but it’s more likely it’s Hindley as emerald would have seen Ewans ability to portray anger well in Michael Gaveys outburst. I just don’t know how everything is going to go down in the Ewan fandom because of it, most will refuse to watch the movie at all but at the same time it’s the only thing they will see of him until season 3 of hotd other than the music video. I have a feeling it’s going to cause a lot of drama in the fandom where people will be chastised for supporting the movie by watching it for Ewan. Everyone should prepare themselves for the shit storm now because it’s coming and I hope it’s not the straw that broke the camels back of what’s left of the Ewan fandom here.

So, first of all, I think we need to wait for the official news. If it's this movie…well, I guess I'll only watch the parts with Ewan. In my case, it doesn't matter, it's been a long time since foreign films have been shown in cinemas in Russia, so I can't financially support the actors' work anyway, even if I wanted to. Another thing is that I still remember how Saltburn's creators used Ewan and his fan base for hype, even though he had two or three minutes of screen time. I don't really want to see it again, plus the movie itself doesn't really seem interesting or worth the time.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kristen Stewart – GQ Russia March 2017 Issue

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Freeman (86/366)

Martin Freeman from GQ Russia,December, (2014).

Photos by Sarah Dunn.

MF with the beard for Richard III.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irina Shayk by David Roemer

- GQ Russia, August 2013

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Content warning: This article contains a scene including a graphic sexual assault.

My friend sets aside his cocktail, its foamy top sprinkled with cinnamon in the shape of a hammer and sickle, to process his disbelief at what I’ve just told him. “You want to return to Russia?” he asks.

I met Enrico when I arrived in Stockholm eight months ago. He understands my situation as well as anyone. He knows that I fled Moscow three days after Russia invaded Ukraine; that my name, along with the names of other journalists who left, has fallen into the hands of pro-Kremlin activists who have compiled a public list of “traitors to the motherland”; that some of the publications where I’ve worked have been labeled “undesirable organizations”; that a summons from the military enlistment office is waiting for me at home; that since Vladimir Putin expanded the law banning “gay propaganda,” I could be fined up to $5,000 merely for going on a date. In short, Enrico knows what may await if I return: fear, violence, harm.

He wants me to explain why I would go back, but I can’t think of an answer he’d understand or accept. Plus, I’m distracted by the TV screens in the bar. They’re playing a video on loop—a crowd in January 1990 waiting to get into the first McDonald’s to open in Russia. The people are in fluffy beaver fur hats, and their voices speak a language that, for the past year, I’ve heard only inside my head. “Why am I here?” a woman in the video says in Russian. “Because we are all hungry, you could say.” As the doors to McDonald’s open and the line starts to move, I no longer hear everything Enrico is saying (“You could live with me rent-free …” “You could go to Albania. It’s cheaper than in Scandinavia ...” “We could get married so you can live and work here legally …”).

Part of me had planned this meeting in hopes that Enrico would persuade me to change my mind—and he did try. But I’ve already bought the nonrefundable plane tickets, which are saved on my phone, ready to go.

A week later, I spend a night erasing the past year from my life—a year of running through Europe as if through a maze. I clear my chats in Telegram and unsubscribe from channels that cover the war. I wipe my browser history, delete my VPN apps, remove the rainbow strap on my watch, and tear the Ukrainian flag sticker from my jacket. The next day—March 29, 2023—I fly to Tallinn, Estonia, and ride a half-empty bus through a deep forest to the Russian border. The checkpoint sits at a bridge over the Narva River, between two late-medieval castles. German shepherds keep watch, and an armed soldier patrols the river by boat.

“What were you doing in the European Union?” the Russian guard asks.

“I was on vacation,” I say.

“You were on vacation for more than a year?” she asks.

I reply that I have been very tired. She stamps my passport and the bus moves on.

What I didn’t tell the guard, and what I couldn’t tell Enrico, is that I’m tired of hiding from my country—and that I want to trade one form of hiding for another. I have conducted my adult life as if censorship and propaganda were my natural enemies, but now some broken part of me is homesick for that world. I want to be deceived, to forget that there is a war going on.

“Start from the beginning,” my mother would say when I couldn’t figure out a homework problem. “Just start all over again.”

I woke up on February 24, 2022, to a message from a friend that read: “The war has begun.” At the time, I was an editor at GQ Russia, gathering material for our next issue on Russian expats who had moved back home during the pandemic. I was also editing a YouTube series called Queerography. For a blissful moment, I took my friend’s text for a joke. Then I saw videos from Ukrainian towns under bombardment. Russian forces had encircled most of the country. My boyfriend was still asleep. I wished I could be in his place.

A few months earlier, American intelligence had informed Ukraine and other countries in Europe of a possible offensive. But Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, had responded: “This is all propaganda, fake news and fiction.” While I didn’t necessarily believe the truth of Lavrov’s words, I doubted the regime could afford to tell a lie so big. Vladimir Putin’s approval rating was near its lowest point since he gained power. On the eve of the attack on Ukraine, only 3 percent of my fellow citizens thought the war was “inevitable.”

After the invasion, I spent three days in silence. I couldn’t sleep, and I had no appetite. My hands trembled so badly that I couldn’t hold a glass of water still. When I visited friends, we’d sit in different corners of the room scrolling through the news, occasionally breaking the silence with “This is fucked up.”

In Moscow, armed police patrolled the streets to deter protesters. Soon, the press reported that a man was arrested in a shopping mall for an “unsanctioned rally” because he was wearing blue and yellow sneakers, the colors of the Ukrainian flag. News media websites were blocked in accordance with the new law on “fake news” about Ukraine. People stood in line to empty the ATMs. “War” and “peace”—two words that form the title of Russia’s most celebrated novel—were now forbidden to be pronounced in public. Instagram was filled with black squares, uncaptioned, seemingly the only form of protest that remained possible. The price of a plane ticket out of Russia soared from $100 to $3,000, in a country where the minimum wage was about $170 a month.

If I waited another day, it seemed, the Iron Curtain would descend and I would become a hostage of my own country. So on the morning of March 1, my boyfriend and I locked the door to our Moscow apartment for the last time and made for the airport. In my backpack were warm clothes, $500 in cash, and a computer. We were leaving for nowhere, not knowing which country we would wake up in the next day.

At the international airport in Yerevan, Armenia, flights arrived every hour from Russia and the United Arab Emirates, another route along which people fled. Once we were there, we boarded a minivan to Georgia, the only country in the South Caucasus with which Russia no longer maintained diplomatic ties. The van was packed with families and their pets. From one of the back seats, a girl asked her mother: “Mama, are we far away from the war now?” A night road through mountain passes and volcanic lakes took us to the border. I asked a guard there to share a mobile hot spot with me so I could get online and retrieve coronavirus test results in my email. “Of course,” he replied, “though you don’t deserve it.”

In Tbilisi, the alleys were lit up at night with blue and yellow. On the city’s main hotel hung a poster that read “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” Fresh graffiti on walls around the city read: “Putin is a war criminal and murderer.”

At an acquaintance’s apartment, we shared a room with two other men who had fled. “The most important thing is that we’re safe,” we reassured each other if one of us began to cry. “I’m not a criminal,” said one of the guys. “Why should I have to run from my own country?” None of us had an answer.

In Russia I was now labeled a “traitor and fugitive.” The Committee for the Protection of National Interests, an organization associated with Putin’s United Russia party, had stolen a database containing the names of journalists who had left the country and distributed it on Telegram. Liberal journalists in Moscow had begun to find the words “Here lives a traitor to the Motherland” scrawled on their doors. One critic was sent a severed pig’s head.

My fellow fugitives and I started looking for somewhere more permanent to live, but most rental ads in Tbilisi stipulated “Russians not accepted.” We tried to open bank accounts, but when the bank employees saw our red passports they rejected our applications. Like so many other companies, Condé Nast—which publishes GQ and WIRED, among other magazines—pulled out of Russia. I was without a job. The YouTube show I edited closed down soon after, its founder declared a foreign agent and later added to the Register of Extremists and Terrorists. Foreign publications told me that all work with Russian journalists was temporarily suspended.

Soon signs began to appear outside bars and restaurants in Tbilisi saying that Russians were not welcome inside. I decided to sign in to Tinder to try to meet people in this new city, but most men I chatted with suggested that I go home and take Molotov cocktails to Red Square. I placed a Ukrainian flag sticker on my breast pocket and wandered the city in silence, ashamed of my language.

My boyfriend and I finally found a room in a former warehouse with no windows, the furniture covered in construction dust. The owner was an artist who was in urgent need of money. To pay the rent, I sold online all my belongings from the Moscow apartment: a vintage armchair from Czechoslovakia, an antique Moroccan rug, books dotted with notes, a record player given to me by the love of my life. Ikea had closed its stores in Russia, and customers wrote to me: “Your stuff is like a belated Christmas miracle.”

One day in mid-spring, I left the warehouse for an anti-war rally that was being held outside the Russian Federation Interests Section based in the Swiss Embassy. The motley throngs of people chanted “No to war!” In the crowd I glimpsed the familiar faces of journalists who had left Russia like me. “Why did you come here?” a stranger asked me in English. “To us, to Georgia. Do you really think your cries will change anything? You shouldn’t be protesting here. You should be outside the Kremlin.”

I wanted to tell him that I grew up in a country where a dictator came to power when I was 6 years old, a man who has his enemies killed. I wanted to say: One time, when I was an editor at Esquire, my boss denounced an author I worked with to Putin’s security service, the FSB, and the FSB sent agents to interrogate me, and when I warned the author, the FSB came for me again, threatening to arrest me and listing aloud the names of all my family members. I wanted to tell the stranger on that street in Tbilisi that I’d had to disappear for a while, and that when I felt brave enough, I had gone to protests and donated money to human rights organizations. That I had fought but, it seemed, had lost. That I just wanted to live the one life I’ve got a little bit longer. But at the time I couldn’t find the words.

A month later, the world saw images of mass graves in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, dead limbs sticking out of the sand. Outside our building one morning, on an old brick wall that was previously empty, was a fresh message, the paint still wet: “Russians, go home.” My boyfriend went back to Russia so he could obtain a European visa, promising he would be back in a month, but he never returned.

I spent the rest of the year on the move: Cyprus, Estonia, Norway, France, Austria, Hungary, Sweden. I went where I had friends. The independent Russian media that I’d always consumed went into exile too, setting up operations where they could. TV Rain began broadcasting out of Amsterdam. Meduza moved its Russian branch to Europe. The newspaper Novaya Gazeta, cofounded by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitry Muratov, reopened in Latvia. Farida Rustamova, a former BBC Russia correspondent, fled and launched a Substack called Faridaily, where she began publishing information from Kremlin insiders. Journalists working for the independent news website Important Stories, which published names and photos of Russian soldiers involved in the murder of civilians in a Ukrainian village, went to Czechia. These, along with 247,000 other websites, were blocked at the behest of the Prosecutor General’s Office but remained accessible in Russia through VPNs.

“During the first days of the war, everything was in a fog,” says Ilya Krasilshchik, the former publisher of Meduza, who went on to found Help Desk, which combines news media and a help hotline for those impacted by war. “We felt it our duty to inform people of what the Russian army was doing in Ukraine, to document the hell that despair and powerlessness leave in their wake. But we also wanted to empathize with all of the people caught up in this meat grinder.” Taisiya Bekbulatova, a former special correspondent for Meduza and the founder of the news outlet Holod, tells me, “In nature you find parasites that can force their host to act in the parasite’s own interest, and propaganda, I believe, works in much the same way. That’s why we felt it was our duty to provide people with more information.”

I wanted to continue my work in journalism, but the publications that had fled Russia weren’t hiring. My application for a Latvian humanitarian visa as an independent journalist was rejected, and I didn’t have the means to pay the fees for US or UK talent visas.

The panic attacks began in the fall, during my first stay in Stockholm. Red spots, first appearing around my groin, started to take over my body, creeping up to my throat. I’d get sick, recover, and then wake up with a sore throat. In October, I learned that my boyfriend had married someone else. The next day, my mother called to tell me that a summons from the military enlistment office had arrived.

I was in Cyprus when, at 3 am one February morning, I woke to the sound of walls cracking and the metal legs of my bed knocking on marble. Fruit fell to the floor and turned to mush. The tremors of a magnitude-7.8 earthquake in Gaziantep, Turkey, had passed through the Mediterranean Sea and reached the island. I didn’t scramble out of bed. I hoped instead that I would be buried under the rubble—a choice made for me by fate. Later that month, my friends in Stockholm insisted that I come stay with them again. I wandered the streets on a clear winter day, buying up expired food in the stores. The blue and yellow flags of Sweden shone bright in the sun, but I saw in them the flag of another country. Back in the apartment, I slept all the time, and when I did wake I lulled myself with Valium. One day I felt the urge to swallow the whole bottle.

Frightened by my own thoughts, I felt how much I wanted to be back in Russia. In my mother country, all the tools of propaganda would keep painful truths at bay. “The news in Russia is only ever good news,” Zhanna Agalakova, a former anchor on state TV’s main news show, later told me. Agalakova quit after the invasion began and returned the awards she had received to Putin. “Even if people understand that they’re being brainwashed, in the end they give up, and propaganda calms them down. Because they simply have nowhere to run.”

Masha Borzunova, a journalist who fled Russia and runs her own YouTube channel, walked me through a typical day of Russian TV: “A person wakes up to a news broadcast that shows how the Russian military is making gains. Then Anti-Fake begins, where the presenters dismantle the fake news of Western propaganda and propagate their own fake news. Then there’s the talk show Time Will Tell that runs for four, sometimes five hours, where we’ll see Russian soldiers bravely advancing. Then comes Male and Female—before the war it was a program about social issues, and now they discuss things like how to divide the state compensation for funeral expenses between the mother of a dead soldier and his father who left the family several years ago. Then more news and a few more talk shows, in which a KGB combat psychic predicts Russia’s future and what will happen on the front. This is followed by the game show Field of Miracles, with prizes from the United Russia party or the Wagner Private Military Company. And then, of course, the evening news.”

I had gone from being infuriated by this kind of hypnosis to envying it. The free flow of information had become for me what a jug of water is to a severely dehydrated person: The right amount can save you, but too much can kill.

“Welcome to Russia,” the bus driver said as we crossed the border from Estonia. I was nearly home. There was no particular reason for me to return to Moscow, so I made for St. Petersburg, where some friends had an apartment that was empty. I used to look after it before the war, coming over to unwind and water the flowers. It was a place of peace.

All my friends had left Russia too, so I was the first person to set foot in the apartment in a year. Black specks covered every surface-—midges that had flown in before the war and died. I scrubbed the place through the first night, starting to cry like a child when I came across ordinary objects I remembered from peacetime: shower gel, a blender, a rabbit mask made out of cardboard. Over the next few weeks, I tried to return to the past as I remembered it. I went to the bakery in the morning. I exercised, read, wrote. At first glance, the city seemed unchanged. There were the same boatloads of tourists on the canals, tour groups on Palace Square, overcrowded bars in Dumskaya Street. But more and more, St. Petersburg began to feel to me like the backdrop of a period film: impeccably executed, the gap between the past and the present visible only in the details.

One day I heard loud noises outside my window, as if all the TVs in town had suddenly started emitting the sound of static. The next day the headline read: “Terrorist Suspected of Bombing St. Petersburg Café Detained and Giving Testimony.” The café had hosted an event honoring the pro-war military blogger Vladlen Tatarsky, and a bust of his likeness had blown up, killing him and injuring more than 30 people. But life went on as if nothing had happened. St. Petersburg was plastered with posters for an upcoming concert by Shaman, a singer who had become popular since the invasion thanks to his song “I’m Russian.” (He would later release “My Fight,” a song that seemingly alludes to Hitler’s Mein Kampf.) In a candy store I noticed a chocolate truffle with a portrait of Putin on the wrapper. “It’s filled with rum,” the clerk said.

Sometimes in checkout lines at the supermarket I glimpsed mercenaries in balaclavas, newly returned from or preparing to go to the front. On the escalator down to the subway, where classical music usually floated from the speakers, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto was interrupted by an announcement: “Attention! Male citizens, we invite you to sign a contract with the military!” In the train car, I saw a poster that read: “Serving Russia is a real job! Sign a military service contract and get a salary starting at 204,000 rubles per month”—about $2,000. One afternoon, as I stood on the platform next to a train bound for a city near the Georgian border, I overheard two men talking:

“I earned 50,000 in a month.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No, bro. But I won’t go back to Ukraine again. It’s fucking terrifying.”

This was a rare admission. The horror of the war’s casualties—zinc coffins, once prosperous cities turned to ruins—were otherwise hidden behind the celebrations for City Day, the opening of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, and marathons held on downtown streets.

After a week or so in Russia, feeling very alone, I went on Tinder. One evening I invited a man I hadn’t met over to the apartment. I placed two cups of tea on a table, but when the man arrived he didn’t touch his. He threw me to the floor, unbuttoned his pants, and inserted his dry penis inside me. “I know you want it,” he whispered, covering my mouth. “I can tell from your asshole.”

I bit him and squirmed, trying to get him off me. After he left, my legs kicked frantically and I couldn’t breathe. I knew that the police wouldn’t help me. I contacted Tinder to tell them that I had been raped and sent them a screenshot of the man’s profile, but no one answered. That evening I bought a ticket for a night train to Moscow. More than ever, I wanted to see my mother.

“You must have frozen over there,” My mother said as she met me at the door to her apartment outside Moscow. Putin had said that, without Russian-supplied gas, “Europeans are stocking up on firewood for the winter like it’s the Middle Ages.” People were supposedly cutting down trees in parks for fuel and burning antique furniture. Some of the only warm places in European cities were so-called Russian houses, government-funded cultural exchanges where people could go escape the cold as part of a “From Russia with Warmth” campaign. When I told my mother that Sweden recycles waste and uses it to heat houses, she grimaced in disgust.

Thirteen months earlier, when I had left the country, my mother called to ask me why. I told her that I didn’t want to be sent to fight, that I couldn’t work in Russia anymore. “You’re panicking for no reason,” she said. “Why would the army need you? We’ll take Kyiv in a few days.” After the horrors in Bucha, I had sent her an interview with a Russian soldier who admitted to killing defenseless people. “It’s fake,” she responded. “Son, turn on the TV for once. Don’t you see that all those bodies are moving?” She was referring to optical distortions in a certain video, which Russian propagandists used to their advantage.

After that, we had agreed not to discuss my decision or views so that we could remain a family. Instead, we talked about my sister’s upcoming wedding, my aunt’s promotion at a Chinese cosmetics company whose products were replacing the brands that had quit the country. My uncle, a mechanic, had finally found a job that would get him out of debt—repairing military equipment in Russian-occupied territories. My mother was planning to take advantage of falling real estate prices to buy land and build a house. In their reality, the war was not a tragedy but an elevator.

I had arrived on Easter Sunday, and the whole family gathered at my mother’s house for the celebration. My aunt told me she was worried that I might be forced to change my gender in the West; she had heard that the Canadian government was paying people $75,000 to undergo gender-affirming surgery and hormonal therapy. My stepfather was interested in the availability of meat in Swedish stores. Someone asked whether it was dangerous to speak Russian abroad, whether Ukrainians had assaulted me. I kept quiet about the fact that the only person who had attacked me since the invasion was a Russian man, that the real threat was much closer than my family thought. The TVs in each of the three rooms of the apartment were all switched on: They played a church service, then a film called Century of the USSR. There were news broadcasts every two hours and the program Moscow. The Kremlin. Putin—a kind of reality show about the president.

“Do you know what this is?” my mother said as she placed a dusty bottle of wine without any labels in the middle of the festive table. “Your uncle gave it to us,” my stepfather chimed in. “He brought it from Ukraine.” A trophy from a bombed-out Ukrainian mansion near Melitopol, stolen by my uncle while Russian soldiers helped themselves to electronics and jewelry. “Let’s drink to God,” said my stepfather, raising his glass. “You can’t raise a glass to God,” my mother answered. “That’s not done.” “Let’s drink to our big family,” he said. The clinking of crystal filled the room; to my ears it sounded like cicadas.

Suddenly I felt sick and locked myself in the bathroom. I tried to vomit, but my stomach was empty, bringing up only a retch. “What’s wrong?” my mother asked, standing outside the door. “Drink some water, rest, sleep.” I tried to lie down. My skin began to itch. My friend Ilya Kolmanovsky, a science journalist, once told me: “Did you know that a person cannot tickle himself? Likewise you cannot deceive a mind that already knows the truth.” Self-deception is dangerous, he said: “Just as your immune system can attack your own body, your mind can also engage in destroying you day by day.”

That evening I left my mother’s apartment for St. Petersburg and made an appointment with a psychiatrist. I told the doctor that I felt like the past had been lost and I couldn’t find a place for myself in the present. She asked when my problems began. “During the war,” I answered, careful to keep my face expressionless. The psychiatrist noted my response in the medical history. “You’re not the only one,” she said. She diagnosed me with prolonged depression and severe anxiety and prescribed tranquilizers, an antipsychotic, and an anti-depressant. “There are problems with drugs from the West,” she said. Better to take the Russian-made ones. If the Western pills were like Fiat cars, then these would be the Russian analog, Zhigulis: “Both will bring you closer to calm, but the quality of the trip will differ.”

Though the drugs seemed to help, I began to realize over the next several weeks that no amount of pills could change this fact: The home I was looking for in Russia existed only in my memories. In June, I decided to emigrate once again. At the border in Ivangorod, spikes of barbed wire pierced the azure sky and smoke from burning fuel oil rose from the chimneys of the customs building. This time, as I left, I felt that I had no reason to return. My home was nowhere, but I would continue searching for one.

With financial help from a friend, I moved to Paris and signed a contract with a book agent. I made an effort not to read the news. Still, from time to time, I came across stories about Putin’s increasing popularity at home, how foreign nationals could obtain Russian citizenship for fighting in Ukraine, how the regime passed a law that would allow it to confiscate property from people who spread “falsehoods about the Russian army.” One day, when air defense systems shot down a combat drone less than 8 miles from my mother’s home, she called me and asked: “Why did you leave? Who else will protect me when the war comes to us? Who if not my son?” I didn’t have an answer. “I love you, Mama”—that was the only truth I could tell her.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mitchell Slaggert | GQ Russia (2019)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Andrija Bikic, Brad Kroenig and Dennis Johnson for GQ Russia

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eva Riccobono by Ellen Von Unwerth for GQ Russia January 2011

#Eva Riccobono#ellen von unwerth#fashion#photography#fashion photography#fashion editorial#celebrity#beauty#glamour

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

all characters in Alleyway Citizen so far

Reminder this series is primarily set in the 2000s (and lots of the prologue is from the early-late 90s) so LGBTQphobia is prominent because it's just way more realistic. which means,, a lot of the queer characters are closeted/comphet/heteronormative as well

not finished!! more characters will be added over time as the series is still in heavy development

MAIN PROTAGS

(🇻🇪) Angelo García Flores (he/him cis man, heteronormative/closeted gay)

(🇺🇦🇺🇸) Marcus Trinity (he/him, cis man, asexual greyromantic)

(🇵🇱) Aleksander Dabrowski (he/they, closeted NB/GQ, bisexual)

(🇬🇧🏴) Edward Brookins (he/any, genderqueer, gay)

(🇨🇳🇰🇭) Kaden Huang (he/any, genderqueer, closeted omnisexual)

PETS/FERALS

(adopted/found in 🇺🇸) Electri (male/gender neutral electronic cat, aleksander's pet)

(adopted/found in 🇹🇷) Amir (male strawberry vampire bat, angelo's pet)

(rescued in 🇲🇽) Squid (female black cat, gabriella's pet)

SECONDARY/SUPPORT/SIDE

(🇲🇽) Gabriella (she/her, cis girl, comphet lesbian)

(🇺🇦🇺🇸) Sabrina Trinity (she/her, cis woman, lesbian)

(🇺🇦🇺🇸) Denis Trinity (he/they, genderqueer, pansexual)

(🇹🇷🇲🇦) Kasca/Mehmet (he/him, cis man, heteronormative queer)

(🇧🇳) Zohra Azim (she/her, cis girl, asexual heteroromantic)

(🇧🇳) Fatima Hussain (she/her, cis woman, heterosexual)

(🇧🇳) Khalid Azim (he/him, cis man, bicurious het)

(🇸🇾) Salma (she/her, cis girl, asexual aromantic)

(🇩🇿) Imran (he/him, cis man, heterosexual)

(🇺🇸) Josiah (he/him, cis "boy" (masculine supernatural being), asexual heteroromantic)

(🇮🇹) Monica Armani (she/her, closeted trans woman, heteroflexible)

(🇷🇺🇺🇸) Eddie Smirnov (he/him, trans man, demisexual biromantic)

(🏴) Mason Desmond (any, genderless masc (he can turn into anything he wants), omnisexual)

(🇪🇸) Valentin Abarca Rodriguez (he/him, cis boy, asexual heteroromantic)

(🇪🇸) Lucia Rojo (she/her, cis girl, bisexual)

(🇪🇸) Elena Rojo (she/her, cis girl, asexual aromantic)

(🇨🇦) Jacob Smith (he/him, cis boy, closeted queer)

(🇬🇧🇨🇦) Aaron Brown (he/him, cis boy, closeted queer)

(🇯🇵🇨🇳) Isamu Jiang (he/him, cis boy, closeted pansexual demiromantic)

(🇷🇺🇩🇪) Kronzi (he/him, cis man, bisexual)

(🇺🇦) Boqshie (he/they, genderqueer, bisexual)

(🇬🇧/🇦🇺) Xavier (any, genderqueer, alloromantic asexual)

(Indigenous 🇧🇷/🇸🇳) Thiago "Pykstar" Silva de Araújo (he/they, cis boy, closeted gay)

(🇨🇦) Skunky (they/he, genderqueer, gay)

(🇯🇵🇻🇳) Tenno Chi (she/they, cis girl, comphet lesbian)

(🇰🇷) Oliver (he/him, trans man, bisexual)

(🇫🇷) Sofia Moreau (she/her, trans woman, lesbian)

(🇫🇷) Gabriel Moreau (he/him, trans man, gay)

(🇫🇷) Charlotte Moreau (she/her, cis woman, bisexual)

VILLAIN ASSOCIATES

(🇺🇾🇺🇸) Lydia (she/her, trans woman, lesbian)

(Indigenous 🇺🇸) Camilo (he/him, cis man, omnisexual)

VILLAINS

Samco "Samuel" Sinner (he/him, cis man, pansexual)

Dr. Misty (she/her, cis woman, bisexual)

Colton Buyantu (he/any, genderqueer, pansexual)

PRISONERS OF WAR

(🇩🇪) Gretel Heindrich (he/him, cis boy, asexual aromantic)

(🇩🇪) Frederick Grasshoff (he/him, cis boy, asexual aromantic)

(🇩🇪) Klaus Hoffmann (he/him, cis boy, asexual closeted homoromantic)

MILITARY

The thing after their pronoun stuff is what military they are in + their rank if available

GR = Germany, BR = Brazil, RUS = Russia, ETC.

Im using english terms for the ranks so its less confusing

🇷🇺🇩🇪 Nikolai Petrov (he/him, cis man, hetero bicurious) (GR, Sergeant)

🇷🇺🇩🇪 Sasha Mikhailov (he/him, cis man, closeted gay except the closet is glass) (GR, Private)

🇩🇪 Ernst Flynn (they/them, genderless, asexual aromantic) (GR, Air Marshal)

🇩🇪 Ruth Schiender (she/her, cis woman, comphet lesbian) (GR, Combat Medic/Private)

🇩🇪 Hans (he/him, cis man, heterosexual) (GR, Field Marshal)

🇩🇪 Joseph Wolf (he/him, cis man, closeted bisexual (GR, Lieutenant)

🇩🇪 Seraphina Wolf (she/her, cis woman, heteroflexible) (GR, Private)

🇨🇮🇩🇪 Reinhard Byrne (he/him, cis man, heterosexual) (GR, Fleet Admiral)

🇬🇧 Caleb Williams (he/him, cis boy, heterosexual) (GR, Volunteer)

(🇷🇺🇺🇦) Lev Kravchenko (he/him, cis man, asexual aromantic) (RUS, Field Marshal)

🇷🇺 Ivan (he/any, cis man, omnisexual) (RUS, Corporal)

🇵🇱 Andrezj Dabrowski (he/him, cis man, heterosexual) (POL, Lieutenant)

🇵🇱 Casimir Filipowicz (he/him, cis man, asexual heteroromantic) (POL, Private)

🇵🇱 Aleksander Dabrowski (previously)

🇧🇷 Antonio Barbosa (he/him, cis man, asexual heteroromantic) (BR, Sergeant)

🇻🇪🇨🇦 Felix Flores (he/him, cis man, heteroflexible) (CA, Sergeant)

WILD MONSTERS

(🇳🇱) Lady Abyss (she/her. cis woman, bisexual)

FAMILY & ROMANTIC RELATIONS

Joseph Wolf & Seraphina Wolf are biological siblings and grew up under the same roof. They still hold a very close bond.

Colton Buyantu & Eddie Smirnov are first cousins and went to the same primary school together when they were children. As adults, they have a distant bond due to their differing beliefs.

Lucia Rojo & Elena Rojo are biological siblings and grew up under the same roof. Unfortunately, Lucia was killed while trying to save Elena, however Elena is able to see her ghost and still talk to her.

Kasca is Zohra's non biological caretaker. He was given custody of Zohra after Khalid (zohra's biological father) went insane and physically assaulted zohra and her mother, Fatima. Khalid then went on to join a illegal terrorist organisation and was never seen again. Despite being zohra's legal mother, Fatima requested Kasca to take care of Zohra for most of the time as by now she is too physically damaged to be able to take care of her child.

Lucia Rojo & Valentin A. Rodriguez are both teenagers and dating. However, shortly after the apocalypse began Lucia was killed in a house fire caused by the terrorist workers of Samco. Corp. Valentin is the only one who can see her ghost other than her own family (Only her little sister Elena survived the fire.)

Felix Flores & Angelo Flores are biological brothers. They share a very close emotional bond but rarely get to see each other physically due to Felix serving in the military.

Gabriel Moreau, Sofia Moreau & Charlotte Moreau are all biological siblings. They all share a very close emotional bond with each other and still live under the same roof with their mother.

Andrezj Dabrowski & Aleksander Dabrowski are biological brothers. They have a very broken bond, Andrezj absolutely hates Aleksander’s guts & Aleksander has an intense fear and disgust of Andrezj. He was also physically abused by Andrezj and the bruises can still be faintly seen on his body.

Marcus Trinity, Sabrina Trinity & Denis Trinity are all biological siblings. Sabrina Trinity & Denis Trinity absolutely hate Marcus due to the fact he was the sole reason they all got kicked out of heaven. Sabrina & Denis live alongside each other while Marcus, obviously stays with his 4 human buddies.

0 notes