#goniopholis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A very fun thing about this image is that it features three pseudosuchians, none of which are all that closely related to each other.

In the background you have the most superficially croc-shaped ones. Machimosaurus hugii and Goniopholis baryglyphaeus.

Machimosaurus, the big one in the back, might look like a gharial of sorts, but its actually a teleosaur, which falls into the clade Thalattosuchia. Thalattosuchia, which also includes the pseudosuchian version of mermaids (metriorhynchoids) are an incredibly old lineage that despite their appearance probably diverged before even many of the land crocs we see in the Cretaceous. So the fact that it so closely matches our idea of a crocodile in shape is largely evolved independently. An additional fun fact, Guimarota is said to preserve the largest Machimosaurus fossils (tho very incomplete). Some old papers claim them to be 9 meters long, but more recent studies have shown that they were probably shorter and just had a stupidly oversized head.

The small guys in front of it are Goniopholis, which look even more superficially croc-like and, to be fair, are also way closer to modern crocs than Machimosaurus. Goniopholids were pretty common during the Jurassic, tho they began to loose influence during the Cretaceous. This species in particular, Goniopholis baryglyphaeus, grew to around 2 meters in length and is actually the oldest member of its group in Europe, which would go on to give rise to Ophiussasuchus which I talked about a few weeks back.

And then we have this little guy, Knoetschkesuchus guimarotae, an atoposaurid that was originally described under the name Theriosuchus. Atoposaurids were pretty small animals with higher skulls, slender limbs and probably terrestrial lifestyles. But believe it or not, this lanky little land croc may have been more closely related to real crocodiles than either of the other two pseudosuchians in the piece, certainly closer than Machimosaurus and, if recent studies are right, closer than Goniopholis as well.

Result from the Guimarota #paleostream.

This locality has done much to further our understanding of Jurassic mammals.

And some details

#machimosaurus#teleosauridae#thalattosuchia#goniopholis#goniopholidae#knoetschkesuchus#atoposauridae#pseudosuchia#croc#prehistory#palaeoblr

630 notes

·

View notes

Text

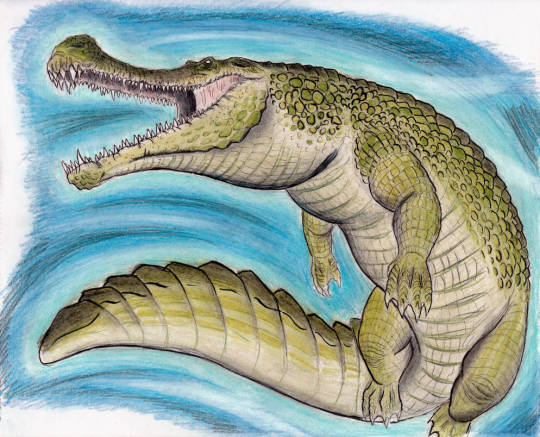

Sarcosuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyliform and distant relative of living crocodilians that lived throughout what is now Africa and South America from the late Hauterivian to the late Cenomanian of the Early Cretaceous Period some 133 to 93 mya. From 1946 to 1959 French paleontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent lead multiple expeditions into the sahara desert, during such time several crocodyliform fossils consisting of fragments of the skull, teeth, scutes and vertebrae were unearthed in the Continental Intercalaire Formation, Foggara Ben Draou region, Ain el Guettar Formation, and the Elrhaz Formation. These were attributed to a large long snouted yet undiagnostic crocodyliform. Then in 1964 a team of researchers from the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission discovered an almost complete skull in the region of Gadoufaoua in Niger. This specimen along was then described by Broin & Taquet in 1966 who named the animal sarcosuchus imperator meaning flesh crocodile supreme ruler. In 1977 a reevalution of material consisting of lower jaw, dorsal scute and two teeth initially found in brazil by American naturalist Charles Hartt in 1897, found them to be Sarcosuchus. These remains where initially classified as a species of Crocodylus then as Goniopholis, and are now considered the type specimen of S. hartti. The next major findings occurred during the expeditions led by the American paleontologist Paul Sereno in 1995, 1997, and 2000. Who discorved 6 fairly complete sarcosuchus individuals. Reaching around 26 to 33ft (8 to 10m) in length and 7,600 to 9,500lbs (3,450 to 4,300 kgs) in weight, sarcosuchus was a benemoth beast. It sported a giant head with elongated jaws, slightly telescoping eyes, and an expansion at the end of its snout known as a bulla. The body was covered in armor and the tail was long and strong yet flexible. In life sarcosuchus would have inhabited inland swamps, lakes, rivers, and wetlands, feeding upon a plethora of fish, amphibians, invertebrates, turtles, lizards, pterosaurs, other crocodyliforms, and even the occasional dinosaur.

Art used can be found at the following links:

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A crocodylomorph tooth of an indeterminate goniopholidid from the Morrison Formation in Moffat County, Colorado, United States. Although commonly labeled as Goniopholis, Morrison goniopholidids were reassigned to other genera such as Amphicotylus, Diplosaurus, and Eutretauranosuchus. The tooth also shows fine "serrations" along the carinae.

#crocodylomorpha#crocodilian#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#amphicotylus#diplosaurus#eutretauranosuchus#goniopholididae#jurassic#mesozoic#science#prehistoric#paleoblr#アンフィコティルス#ディプロサウルス#エウトレタウラノスクス#ゴニオフォリス科#ワニ#化石#古生物学

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Vintage The World of Dinosaurs Stamps 1997 One Pane of Twenty Stamp 32 Cent Each.

0 notes

Text

Often lauded as the real inspiration for the JP Raptors™, Deinonychus antirrhopus is bigger and bulkier than it’s Asian relative Velociraptor, but still very different from its movie monster “twin.”

Deinonychus was first discovered in 1931, but it wasn’t until more material was discovered in the 60s and paleontologist John Ostrom completed a study on the animal in 1969, that Deinonychus revolutionized the way scientists thought of dinosaurs. Long thought to be giant, slow, plodding monsters, Deinonychus seemed to be sleek, agile, and active, with a horizontal posture and raptorial birdlike claws. This development in paleontology has been deemed the “dinosaur renaissance” and is regarded as one of the most important discoveries in dinosaur paleontology.

This discovery of birdlike agility and behavior in dinosaurs led author Michael Crichton to write his Jurassic Park novels, featuring these new swift killers as the antagonists. Crichton even met with John Ostrom several times to discuss the behaviors and appearance of his raptors. However, with apologies to Ostrom, Crichton admitted to changing the name of the creatures to “Velociraptor,” as he felt the name was more dramatic. The movies based off of the books followed suit, and the rest is history.

Deinonychus lived in swamp-like habitats of Cretaceous U.S.A, and remains have been found in Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, as well as possible teeth found as far east as Maryland. It could grow up to 3.4 meters (11 ft) long, and would have been about as tall as a Great Dane. Their “killing claws,” when reconstructed with a sheath over the bone (as in birds and crocodilians), are estimated to have been 120 millimetres (4.7 in) long.

Deinonychus teeth and other fossils are often found in association with the ornithopod Tenontosaurus, suggesting it may have hunted them. However, the horse-sized Tenontosaurus were much larger and heavier than the dog-sized predator. This, along with Deinonychus fossils usually being found together with other Deinonychus, suggest that the raptor may have hunted in groups, or at least in pairs. However, this could also be evidence that the raptors simply scavenged these large carcasses, and merely tolerated each others’ presence.

While Deinonychus are typically presented in media as unusually fast (and, yes, they would have been faster than what was previously thought capable for dinosaurs) their leg anatomy was not built for speed and they would not have been able to outrun modern flightless dinosaurs such as ostriches and emus.

Along with Tenontosaurus, Deinonychus would have lived alongside the nodosaur Sauropelta, the small ornithischian Zephyrosaurus, and the crocodilians Goniopholis and Paluxysuchus. In Oklahoma, it would have had to look out for Acrocanthosaurus and the giant sauropod Sauroposeidon.

#it’s sideways cause I wanted to fit more of it in my typical 1000 x 1000 box for these#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Deinonychus#Deinonychus antirrhopus#dromeosaur#raptor#theropods#dinosaurs#archosaurs

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

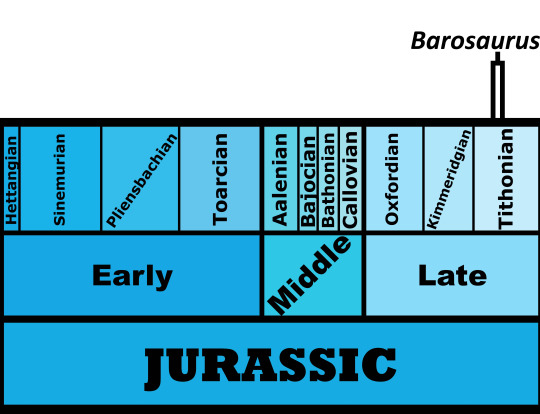

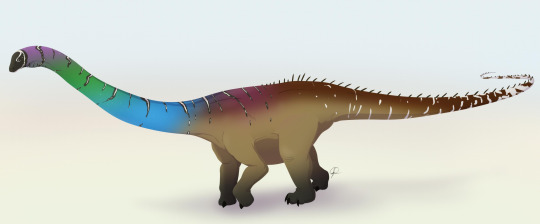

Barosaurus lentus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Heavy Reptile

First Described By: Marsh, 1890

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Bagualosauria, Plateosauria, Massopoda, Sauropodiformes, Anchisauria, Sauropoda, Gravisauria, Eusauropoda, Neosauropoda, Diplodocoidea, Diplodocimorpha, Flagellicaudata, Diplodocidae, Diplodocinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 150 and 149 million years ago, in the Tithonian of the Late Jurassic

Barosaurus is known from the Brush Basin Member of the Morrison Formation in South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. Potential specimens of Barosaurus are known from other locations of the Morrison Formation; the entire range of this habitat at the time of Barosaurus is shown below in green (with the range of Barosaurus inside of it, in blue).

Physical Description: Barosaurus in a lot of ways is a fairly typical Diplodocid sauropod - long, large, and with a distinctive whip-tail. But, when you dig under the surface, Barosaurus has nothing truly “typical” about it. The neck of Barosaurus is next-level in its length - and the tail is ridiculous to match. In fact, the estimates of the length of Barosaurus get huge - it was probably more than twenty-six meters long, and some of the most upper estimates of Barosaurus have it at fifty meters long! This would make it one of, if not the, largest known dinosaurs - and certainly the longest! Though it does have a long tail, it differs in appearance from its cousin Diplodocus primarily by having a proportionally longer neck and shorter tail. It was also more slender than Apatosaurus, though it was longer than that contemporary. How did Barosaurus get such a long neck? It literally converted one of the back vertebrae into a neck vertebra! This is so fascinating that I can’t get over it - its close relatives, like Diplodocus, did not employ this to get a longer neck, indicating Barosaurus was using its long neck for things that its cousins were not. Barosaurus was also weird in not having as high of spines on its vertebrae as its cousin Diplodocus and other members of the group. In addition to all of that - it had shorter vertebrae in the tail, which made it shorter than in other members of this group! Interestingly, the bones on the underside of the tail were forked and had forward spikes, which would have given it similar strength to that of Diplodocus; it was probably still a whiptail like other members of this group, though not as much of one as its relatives.

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

Of course, the distinctiveness of Barosaurus is primarily limited to the length of the animal and its spine. In terms of limbs, it had fairly identical limbs to its cousin Diplodocus, though it did have fairly long forelimbs compared to its cousin (by… an almost imperceptible amount, however). Though the feet of Barosaurus aren’t known, it is reasonable to suppose that it would have had feet similar to Diplodocus - with only one claw on the front feet and three small claws on the hind feet. The skull of Barosaurus is not known, but it probably would have been long and low, with peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws for grazing on plants. Its neck was not very flexible in the vertical sense, but it was much more flexible in sweeping from side to side. It is possible that there were spikes of some sort at the end of the tail, which would have packed quite a punch when the tail was used to whip other animals. And, finally, it would have been entirely - if not almost entirely - scaly all over its body. It is also possible that Barosaurus may have featured some brilliant colors, especially in the tail, for communication with other members of the species.

Diet: Barosaurus would have primarily fed on high-level vegetation, able to reach much of it at its natural neck height and then - on top of that - being able to rear up to 50 meters high via going on its hind legs. However, a lack of vertical reach in terms of neck flexibility means that it probably would have swept over a wide area for food, rather than going up and down in the tree level like other Diplodocids. This would have allowed Barosaurus to move very little - if at all - while eating, instead of moving over large distances in search of vegetation.

By Scott Reid

Behavior: Barosaurus was not especially common in its environment, so the question of its social nature is actually somewhat important. Fossil evidence indicates at least some sociality in other Diplodocids - herding, or at least small herds, of other sauropods on the Morrison are clear from fossil evidence and trackways. The question remains - did Barosaurus do what its cousins did? The question is, of course, up in the air without more fossil evidence. It is possible that, in an environment with hundreds and hundreds of large sauropods to feed, Barosaurus may have been more solitary to aid in getting enough food without competing too much with one another. Alternatively, it may have also lived in social groups, allowing for the safety of weaker members of the herd and more cohesiveness in finding food.

Barosaurus, like other Diplodocids, would have been able to rear up on its hind legs to get food. This action would have also made Barosaurus even taller than usual, which would have been fairly imposing to predators nearby. It had a whip-tail, which would have allowed Barosaurus to make very loud sonic cracks in the air; if that tail was covered with spikes, as in other members of the group, it would have also lacerated the skin of other dinosaurs. Still, even without spikes, it would have packed quite a punch for any predators that might have tried to attack it. The sounds of the tail would have been a warning; it is possible that such sounds would have been used in communication with one another, and potentially even display in competition for mates and food and similar things. The impossibly long neck probably was also a sort of sexual display structure, since the longer neck indicated being able to reach more food without walking around. It is uncertain whether or not it would have taken care of its young; while there is no evidence either way - which usually would lead to concluding it did, given the fact most living archosaurs do and there’s extensive evidence of such in extinct dinosaurs - other sauropods (aka the titanosaurs) probably didn’t. So, for now, the jury on that is out.

By Fred Wierum, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Barosaurus lived in the Morrison Formation - an extensive, expansive semi-arid, seasonal floodplain that covered most of Western North America during the Jurassic and was filled with iconic dinosaurs and other animals that we usually think of when we think of the “Jurassic.” Though the Morrison was as arid and open as a modern savanna, the lack of extensive flowering plants at this time rendered the habitat more like a ridiculously huge scrubland. There were a variety of trees - conifers, ginkgos, cycads, and tree ferns - dispersed among the bushes and horsetails and other plants. They congregated around rivers, which were havens of life amongst the arid territory. At the time of the Brushy Basin Environment - the last part of the formation, where Barosaurus could be found - this environment was much muddier and wetter, potentially indicating a change in ecology that would lead to the end of the Morrison Formation, and an extinction of the animals there. There were also expansive volcanic explosions that lead to much of the preservation we see there. A large salt lake present would have been a major feature of the environment, and it was connected to extensive wetlands that formed a break in the wider scrubland around the habitat.

By Danny Cicchetti, CC BY-SA 3.0

Barosaurus may be known from the entire Brushy Basin Environment of the Morrison; however, confirmed fossils of this dinosaur are only known from a few sites. So, in my map above, I give two colors - the wider green color to show the whole ecosystem, aka the wider area that Barosaurus may have ventured in to; and the smaller blue color to show the confirmed range of this dinosaur. In that confirmed range, Barosaurus lived alongside a lot of other animals - in fact, there’s a reason the Morrison is so iconic - its characteristic and distinctive fossils, both of dinosaurs and not of dinosaurs. Barosaurus has been found in, literally, the same sites as other animals - it is known to have lived alongside the predator Allosaurus; in another site, turtles and Pseudosuchians and the Choristodere Cteniogenys, as well as Allosaurus and the more bulky sauropod Camarasaurus; in yet another, Barosaurus lived alongside many turtles, the Pseudosuchians Hoplosuchus and Goniopholis, the tuatara-like Opisthias, and a wide variety of dinosaurs - other sauropods like Diplodocus Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus, predators like Allosaurus Torvosaurus and Ceratosaurus, and Ornithiscians like Stegosaurus Dryosaurus and Uteodon. So, Barosaurus was a part of a very wide and diverse community, with a great diversity in terms of herbivores and predators that would have attacked Barosaurus. That being said, there were many other animals that may have lived alongside Barosaurus, based on just… probability, even though they weren’t found directly with it. There were other stegosaurs like Alcovasaurus and Hesperosaurus; more small running herbivores like Nanosaurus; larger bulky bipedal herbivores like Camptosaurus; more sauropods, including Apatosaurus and Supersaurus; and smaller predators that would have probably been more of a threat to Barosaurus young than adults - Marshosaurus, Coelurus, Ornitholestes, and Stokesosaurus. Sadly, the organization of the Morrison is something of a mess - so, while many other dinosaurs and animals lived alongside Barosaurus, we can’t exactly be sure which ones. There were probably a variety of Multituberculate, Tinodontid, Eutriconodont, and Dryolestoid mammals, as well as others; some pterosaurs were probably there like Harpactognathus, and, of course, there were amphibians as well. This makes the Morrison one of the better examples of an environment to highlight as a representative of a particular time in Earth’s history - since it showcases so many different living things!

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Barosaurus was a close relative of Diplodocus, though it is difficult to determine how close, as the evolutionary relationships between the Diplodocids are still being worked out via phylogenetic studies. It is possible that an offshoot of Diplodocus (which were around before Barosaurus evolved) split to take advantage of not moving much to eat, and instead sweeping its neck around to gather food. For a while, another sauropod in Africa was considered to be a species of Barosaurus; today, however, it seems to be very clearly in its own genus, Tornieria, and actually far removed from both Diplodocus and Barosaurus (while still being in this closely related family group). So, for now, Barosaurus is only known from North America. These dinosaurs were distinctive long and slender sauropods, as opposed to their long and bulky cousins, the Apatosaurines, that they lived alongside.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Allen, Eric Randall (Summer 2012). "Analysis of North American goniopholidid crocodyliforms in a phylogenetic context.” University of Iowa Research Online.

Apesteguía, S. 2005. Evolution in the hyposphene-hypantrum complex within Sauropoda. In K. Carpenter and V. Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 248-267.

Arldt, T. 1909. Die Dinosaurier [The dinosaurs]. Naturwissenshaftliche Rundschau 24(21):261-263.

Averianov, A. O., and T. Martin (2015). "Ontogeny and taxonomy of Paurodon valens (Mammalia, Cladotheria) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of USA" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 319 (3): 326–340.

Berman, D. S., and J. S. McIntosh. 1978. Skull and relationships of the Upper Jurassic sauropod Apatosaurus (Reptilia, Saurischia). Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 8:1-35.

Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; and Kirkland, J.I. (eds.) (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120.

Bonaparte, J. F. 1986. The early radiation and phylogenetic relationships of the Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs, based on vertebral anatomy. In K. Padian (ed.), The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Change Across the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 247-258

Bonaparte, J. F. 1986. Les dinosaures (Carnosaures, Allosauridés, Sauropodes, Cétosauridés) du Jurassique Moyen de Cerro Cóndor (Chubut, Argentina) [The dinosaurs (carnosaurs, allosaurids, sauropods, cetiosaurids) from the Middle Jurassic of Cerro Cóndor (Chubut, Argentina)]. Annales de Paléontologie (Vert.-Invert.) 72(3):325-386.

Britt, B. B., and B. G. Naylor. 1994. An embryonic Camarasaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation (Dry Mesa Quarry, Colorado). In K. Carpenter, K. F. Hirsch, and J. R. Horner (eds.), Dinosaur Eggs and Babies 256-264.

Butler, R.J., P.M. Galton, L.B. Porro, L.M. Chiappe, D.M. Henderson, and G.M. Erickson. 2009. Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 10.1098/rspb.2009.1494.

Caldwell, M. W.; Nydam, R. L.; Palci, A.; Apesteguía, S. N. (2015). "The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution". Nature Communications. 6: 5996.

Calvo, J. O., and L. Salgado. 1995. Rebbachisaurus tessonei sp. nov. a new Sauropoda from the Albian-Cenomanian of Argentina; new evidence on the origin of the Diplodocidae. GAIA 11:13-33.

Carpenter K & Galton PM (2001). "Othniel Charles Marsh and the Eight-Spiked Stegosaurus". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 76–102.

Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

Carpenter, K. and Wilson, Y. 2008. A new species of Camptosaurus (Ornithopoda: Dinosauria) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, and a biomechanical analysis of its forelimb. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 76:227-263.

Carpenter, Kenneth (2018). Maraapunisaurus fragillimus, N.G. (formerly Amphicoelias fragillimus), a basal Rebbachisaurid from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Colorado. Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 227–244.

Carrano and Sampson, 2008. The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6, 183-236.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Charig, A. J. 1980. A diplodocid sauropod from the Lower Cretaceous of England. In L. L. Jacobs (ed.), Aspects of Vertebrate History: Essays in Honor of Edwin Harris Colbert. Museum of Northern Arizona Press, Flagstaff 231-244

Chure, 2001. The second record of the African theropod Elaphrosaurus (Dinosauria, Ceratosauria) from the Western Hemisphere. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte. 2001(9).

Chure, Daniel J. (2001). "On the type and referred material of Laelaps trihedrodon Cope 1877 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". In Tanke, Darren; and Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.) (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 10–18.

Chure, D. J., R. Litwin, S. T. Hasiotis, E. Evanoff, and K. Carpenter. 2006. The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006. In J. R. Foster, S. G. Lucas (eds.), Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36:233-249

Coombs, W. P., and R. E. Molnar. 1981. Sauropoda (Reptilia, Saurischia) from the Cretaceous of Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 20(2):351-373

Curtice, B. D. 1995. A description of the anterior caudal vertebrae of Supersaurus vivianae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3, suppl.):25A

Dalman, S.G. (2014). "New data on small theropod dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Como Bluff, Wyoming, USA". Volumina Jurassica. 12 (2): 181–196.

Demko, Timothy M.; Parrish, Judith T. (1998). "Paleoclimatic setting of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 283-296.

Dodson, P. 1997. American dinosaurs. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 10-13

Ekart, Douglas D.; Cerling, Thure E.; Montanez, Isabel P.; Tabor, Neil J. (1999). "A 400 million year carbon isotope record of pedogenic carbonate; implications for paleoatmospheric carbon dioxide" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 299 (10): 805–827.

Engelmann, George F.; Chure, Daniel J.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2004). "The implications of a dry climate for the paleoecology of the fauna of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 297-308. 167. pp. 297–308.

Foster, John R. (1996). "Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming". Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming. 31 (1): 1–25.

Foster, J.R. 2003. Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Bulletin 23.

Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

Foster, J. 2007. Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

Foster, J.R. 2009. Preliminary body mass estimates for mammalian genera of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, North America). PaleoBios 28(3):114-122.

Foster, J. (2018). "A new atoposaurid crocodylomorph from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Wyoming, USA". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 287–295.

Fraas, Eberhard (1908). "Ostafrikanische Dinosaurier". Palaeontographica. 55: 105–144.

Galianom, H., and R. Albersdörfer. 2010. A New Basal Diplodocoid Species, Amphicoelias brontodiplodocus from the Morrison Formation, Big Horn Basin, Wyoming, with Taxonomic Reevaluation of Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Barosaurus and Other Genera. Dinosauria International (Ten Sleep, WY) Report for September 2010 1-41

Gallina, P. A., and S. Apesteguía. 2005. Cathartesaura anaerobica gen. et sp. nov., a new rebbachisaurid (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Huincul Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Río Negro, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, nuevo serie 7(2):153-166

Galton, P. M. 1977. The Upper Jurassic dinosaur Dryosaurus and a Laurasia-Gondwana connection in the Upper Jurassic. Nature 268(5617):230-232

Galton, P.M. & Powell, H.P. (1980). "The ornithischian dinosaur Camptosaurus prestwichii from the Upper Jurassic of England". Palaeontology. 23: 411–443.

Galton, P.M. (1981). Dryosaurus, a hypsilophodontid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of North America and Africa. Postcranial skeleton. Palaeontol. Z. 55(3/4), 271-312

Galton, 1982. Elaphrosaurus, an ornithomimid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of North America and Africa. Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 56, 265-275.

Galton PM, Upchurch P (2004). "Stegosauria". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H. The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press. p. 361.

Galton, P.M. (2010). "Species of plated dinosaur Stegosaurus (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic) of western USA: new type species designation needed". Swiss Journal of Geosciences 103 (2): 187–198.

Galton, Peter M. & Carpenter, Kenneth, 2016, "The plated dinosaur Stegosaurus longispinus Gilmore, 1914 (Dinosauria: Ornithischia; Upper Jurassic, western USA), type species of Alcovasaurus n. gen.", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 279(2): 185-208.

Gillette, D.D. (1991). "Seismosaurus halli, gen. et sp. nov., a new sauropod dinosaur from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous) of New Mexico, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (4): 417–433.

Gilmore, C.W. (1909). "Osteology of the Jurassic reptile Camptosaurus, with a revision of the species of the genus, and descriptions of two new species". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 36 (1666): 197–332.

Harris, J. D., and P. Dodson. 2004. A new diplodocoid sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49(2):197-210

Harris, J. D. 2006. The axial skeleton of the dinosaur Suuwassea emilieae (Sauropoda: Flagellicaudata) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA. Palaeontology 49(5):1091-1121.

Hartman, S.; Mickey Mortimer; William R. Wahl; Dean R. Lomax; Jessica Lippincott; David M. Lovelace (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247.

Haughton, S. H. 1928. On some reptilian remains from the Dinosaur Beds of Nyasaland. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 16:67-75

Hay, O. P. 1902. Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America. Bulletin of the United States Geological Survey 179:1-868

Hendrickx, C, Mateus O. 2014. Torvosaurus gurneyi n. sp., the largest terrestrial predator from Europe, and a proposed terminology of the maxilla anatomy in nonavian theropods, 03. PLoS ONE. 9:e88905., Number 3.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110.

Huene, F. v. 1908. Die Dinosaurier der Europäischen Triasformation mit berücksichtigung der Ausseuropäischen vorkommnisse [The dinosaurs of the European Triassic formations with consideration of occurrences outside Europe]. Geologische und Palaeontologische Abhandlungen Suppl. 1(1):1-419

Huene, F. v. 1909. Skizze zu einer Systematik und Stammesgeschichte der Dinosaurier [Sketch of the systematics and origins of the dinosaurs]. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie 1909:12-22

Huene, F. v. 1927. Short review of the present knowledge of the Sauropoda. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 9(1):121-126

Huene, F. v. 1927. Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden [Sorting through the basis of the current knowledge of sauropods]. Eclogae Geologica Helveticae 20:444-470

Huene, F. v. 1929. Los sauriquios y ornitisquios del Cretáceo argentino. Anales del Museo de La Plata, serie 2 3:1-196

Ibiricu, L. M., G. A. Casal, M. C. Lamanna, R. D. Martínez, J. D. Harris and K. J. Lacovara. 2012. The southernmost records of Rebbachisauridae (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea), from early Late Cretaceous deposits in central Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 34:220-232

Janensch, W. 1914. Übersicht über die Wirbeltierfauna der Tendaguru-Schichten [Overview of the vertebrate fauna of the Tendaguru beds]. Archiv für Biontologie 3:81-110

Janensch, Werner (1922). "Das Handskelett von Gigantosaurus robustus und Brachiosaurus brancai aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1922: 464–480.

Jenkins, J.T. and J.L. Jenkins. 1993. Colorado's Dinosaurs. Denver, Colorado: Colorado Geologic Survey. Special Publication 35.

Joleaud, L. 1922. Les reptiles fossiles [Fossil reptiles]. Association Française pour l'Avancement des Sciences. Conférences. Compte Rendu de la 45e Session 49-66

Kenneth Carpenter; Peter M. Galton (2018). "A photo documentation of bipedal ornithischian dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, USA". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 167–207.

Kirkland, J. I. 1997. Cedar Mountain Formation. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 98-99.

Kowallis, Bart J.; Christiansen, Eric H.; Deino, Alan L.; Peterson, Fred; Turner, Christine E.; Kunk, Michael J.; Obradovich, John D. (1998). "The age of the Morrison Formation" (PDF). In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 235-260.

Ksepka, D. T., and M. A. Norell. 2010. The Illusory Evidence for Asian Brachiosauridae: New Material of Erketu ellisoni and a Phylogenetic Reappraisal of Basal Titanosauriformes. American Museum Novitates 3700:1-27.

Lockley, M.; Harris, J.D.; and Mitchell, L. 2008. "A global overview of pterosaur ichnology: tracksite distribution in space and time." Zitteliana. B28. p. 187-198.

Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 527–544.

Lucas S, Herne M, Heckert A, Hunt A, and Sullivan R. Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, A Late Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaur from New Mexico. The Geological Society of America, 2004 Denver Annual Meeting (7–10 November 2004).

Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Rinehart, Larry A.; Heckert, Andrew B; Herne, Matthew C.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Foster, John R.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 149-161.

Lull, R. S. 1919. The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh: redescription of the type specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 6:1-42.

Lull, R. S. 1924. Dinosaurian climatic response. In M. R. Thorpe (ed.), Organic Adaptation to Environment 225-279.

Lydam, R. L., Daniel J. Chure and Susan E. Evans (2013). "Schillerosaurus gen. nov., a replacement name for the lizard genus Schilleria Evans and Chure, 1999 a junior homonym of Schilleria Dahl, 1907" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3734 (1): 99–100.

Madsen, J. H., and W. E. Miller. 1979. the fossil vertebrates of Utah, an annotated bibliography. Brigham Young University Geology Studies 26(4):iii-147

Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Upchurch, Paul (2008). "Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (4): 367–407.

Mannion, P. D., P. Upchurch, O. Mateus, R. N. Barnes, and M. E. H. Jones. 2012. New information on the anatomy and systematic position of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal, with a review of European diplodocoids. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(3):521-551

Marsh, O. C. 1890. Description of new dinosaurian reptiles. The American Journal of Science, series 3 39:81-86.

Marsh, O. C. 1895. On the affinities and classification of the dinosaurian reptiles. American Journal of Science 50(300):483-498.

Marsh, O. C. 1896. The dinosaurs of North America. United States Geological Survey, 16th Annual Report, 1894-95 55:133-244.

Marsh, O. C. 1898. On the families of sauropodous Dinosauria. Geological Magazine, decade 4 3:157-158.

Marsh, Othniel C. (1899). "Footprints of Jurassic dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 4 (7): 227–232.

Martin, John. 1987. Mobility and feeding of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) – why the long neck? pp. 154–159 in P. J. Currie and E. H. Koster (eds), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Boxtree Books, Drumheller (Alberta). 239 pages.

Mateus, O., & Antunes M. T. 2000. Ceratosaurus sp. (Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the Late Jurassic of Portugal. Abstract volume of the 31st International Geological Congress, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Mateus, O. 2006. Late Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): a comparison. In J. R. Foster, S. G. Lucas (eds.), Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36:223-231.

Mateus, O. (2007). Notes and review of the ornithischian dinosaurs of Portugal. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27, 114A-114A., Jan: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Mateus, O., & Tschopp E. (2013). Cathetosaurus as a valid sauropod genus and comparisons with Camarasaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts, 2013. 173.

McIntosh, J. S. 1981. Annotated catalogue of the dinosaurs (Reptilia, Archosauria) in the collections of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 18:1-67.

McIntosh, J. S. 1990. Sauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmólska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley 345-401.

McIntosh, J. S. 1997. Sauropoda. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 654-658.

McIntosh, J. S. 2005. The genus Barosaurus Marsh (Sauropoda, Diplodocidae). In K. Carpenter and V. Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 38-77.

Melstrom, K. M., M. D. D'Emic, D. J. Chure and J. A. Wilson. 2016. A juvenile sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Utah, U.S.A., presents further evidence of an avian style air-sac system. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(4):e1111898:1-23.

Mezga, A., B. C. Tesovic, and Z. Bajraktarevic. 2007. First record of dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of the Adriatic-Dinaridic carbonate platform (Croatia). Palaios 22(2):188-199.

Miller, W. E., J. L. Baer, K. L. Stadtman and B. B. Britt. 1991. The Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry, Mesa County, Colorado. In W. R. Averett (ed.), Guidebook for Dinosaur Quarries and Tracksites Tour, Western Colorado and Eastern Utah 31-46.

Mocho, P., R. Royo-Torres, and F. Ortega. 2014. Phylogenetic reassessment of Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, a basal Macronaria (Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 170:875-916.

Moore, George T.; Hayashida, Darryl N.; Ross, Charles A.; Jacobson, Stephen R. (1992). "Paleoclimate of the Kimmeridgian/Tithonian (Late Jurassic) world: I. Results using a general circulation model". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 93 (3–4): 113–150.

Nopcsa, B. F. 1928. The genera of reptiles. Palaeobiologica 1:163-188.

Olshevsky, G. 1992. A revision of the parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, excluding the advanced Crocodylia. Mesozoic Meanderings 2:1-268.

Parrish, J.T.; Peterson, F.; Turner, C.E. (2004). "Jurassic "savannah"-plant taphonomy and climate of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, Western USA)". Sedimentary Geology. 167 (3–4): 137–162.

Pickering, 1995a. Jurassic Park: Unauthorized Jewish Fractals in Philopatry. A Fractal Scaling in Dinosaurology Project, 2nd revised printing. Capitola, California. 478 pp.

Pritchard, A. C.; Turner, A. H.; Allen, E. R.; Norell, M. A. (2013). "Osteology of a North American Goniopholidid (Eutretauranosuchus delfsi) and Palate Evolution in Neosuchia". American Museum Novitates 3783 (3783).

Rauhut, O. W. M., K. Remes, R. Fechner, G. Cladera, and P. Puerta. 2005. Discovery of a short-necked sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Patagonia. Nature 435:670-672.

Remes, K. 2006. A revision of the Tendaguru sauropod dinosaur Tornieria africana (Fraas) and its relevance for sauropod paleobiogeography. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(3):651-669.

Remes, K. 2007. A second Gondwanan diplodocid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania, East Africa. Palaeontology 50(3):653-667.

Romer, A. S. 1956. Osteology of the Reptiles, University of Chicago Press 1-77.

Romer, A. S. 1966. Vertebrate Paleontology, 3rd edition 1-468.

Royo-Torres, R., A. Cobos, A. Aberasturi, E. Espílez, I. Fierro, A. González, L. Luque, L. Mampel, and L. Alcalá. 2007. Riodeva sites (Teruel, Spain) shedding light to European sauropod phylogeny. Geogaceta 41:183-186.

Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I., L. Piñuela, and J. C. García-Ramos. 2008. Primera evidencia de dinosaurios diplodocinos (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae) en el Jurásico Superior de Asturias (Noreña) [First evidence of diplodocine dinosaurs (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae) in the Upper Jurassic of Asturias (Noreña)]. In J I Ruiz-Omeñaca, L Piñuela and J C García-Ramos (eds), XXIV Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Paleontología, 15-18 October 2008, Museo del Jurásico de Asturias (MUJA), Colunga, Spain, Libro de Resúmenes 191-192.

Russell, D., P. Beland, and J. McIntosh. 1980. Paleoecology of the dinosaurs of Tendaguru (Tanzania). Mem. Society Geol. France, N.S. 139:169-175.

Russell, D. A. 1984. A check list of the families and genera of North American dinosaurs. Syllogeus 53:1-35.

Saleiro, A., & Mateus O. (2017). Upper Jurassic bonebeds around Ten Sleep, Wyoming, USA: overview and stratigraphy. Abstract book of the XV Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Paleontología/XV Encontro de Jovens Investigadores em Paleontologia, Lisboa, 428 pp.. 357-361.

Salgado, L. 1993. Comments on Chubutisaurus insignis del Corro (Saurischia, Sauropoda). Ameghiniana 30(3):265-270.

Salgado, L. 1999. The macroevolution of the Diplodocimorpha (Dinosauria; Sauropoda): a developmental model. Ameghiniana 36(2):203-216.

Salgado, L., I. d. S. Carvalho, and A. C. Garrido. 2006. Zapalasaurus bonapartei, un nuevo saurópodo de La Formación La Amarga (Cretacico Inferior), noroeste de Patagonia, Provincia de Neuquén, Argentina [Zapalasaurus bonapartei, a new sauropod from the La Amarga Formation (Lower Cretaceous), northwestern Patagonia, Neuquén province, Argentina]. Géobios 39:695-707.

Schultz, J. A; Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar; Zhe-Xi Luo (2018). "Re-examination of the Jurassic mammaliaform Docodon victor by computed tomography and occlusal functional analysis". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. in press. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9418-5.

Seebacher, Frank. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60.

Seeley, Harry G. (1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria and Reptilia, from the Secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. pp. 143pp.

Sereno, P. C. 1997. The origin and evolution of dinosaurs. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 25:435-489.

Smith, David K. (1998). "A morphometric analysis of Allosaurus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (1): 126–142.

Smith, D. M., M. A. Gorman, J. D. Pardo and B. J. Small. 2011. First fossil Orthoptera from the Jurassic of North America. Journal of Paleontology 85(1):102-105.

Steel, R. 1970. Part 14. Saurischia. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie/Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1-87.

Sternfeld, R. 1911. Zur Nomenklatur der Gattung Gigantosaurus Fraas [On the nomenclature of the genus Gigantosaurus Fraas]. Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 8:398.

Suteethorn, S., J. Le Loeuff, E. Buffetaut and V. Suteethorn. 2010. Description of topotypes of Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae, a sauropod from the Sao Khua Formation (Early Cretaceous) of Thailand, and their phylogenetic implications. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 256(1):109-121.

Swinton, W. E. 1970. The Dinosaurs, Wiley-Interscience, New York 1-331.

Tatarinov, L. P. 1964. Nadotryad Dinosauria. Dinozavry [Superorder Dinosauria. Dinosaurs]. In Y. A. Orlov (ed.), Osnovy Paleontologii [Fundamentals of Paleontology] 12:523-589.

Taylor, Michael P; Wedel, Mathew J (2013). "The neck of Barosaurus was not only longer but also wider than those of Diplodocus and other diplodocines". PeerJ. 1: e67v1.

Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K., and Miles, C., 2005, A reexamination of Morosaurus agilis (Sauropoda) from Garden Park, Colorado: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (Supplement to 3):122A.

Tornier, G. 1913. Reptilia. Paläontologie [Reptilia. Paleontology]. Handwörterbuch der Naturwissenschaften 8:337-376.

Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

Tschopp, E., and O. Mateus. 2013. The skull and neck of a new flagellicaudatan sauropod from the Morrison Formation and its implication for the evolution and ontogeny of diplodocid dinosaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 11(7):853-88.

Tschopp, E., O. Mateus, and R. B. J. Benson. 2015. A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). PeerJ 3:e857.

Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred (2004). "Reconstruction of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation extinct ecosystem—a synthesis". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 309-355.

Upchurch, P. 1995. The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 349:365-390.

Upchurch, P. 1995. Sauropod phylogeny and palaeoecology. In M. G. Lockley, V. F. dos Santos, C. A. Meyer, & A. P. Hunt (eds.), Aspects of Sauropod Paleobiology. GAIA 10:249-260.

Upchurch, P., P. M. Barrett, and P. Dodson. 2004. Sauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmolska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 259-322.

von Zittel, K. A. v. 1890. Handbuch der Palaeontologie. I. Abteilung Paleozoologie. III. Band. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves) [Handbook of Paleontology. Division I. Paleozoology. Volume III. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves)] xii-900.

von Zittel, K. A. 1911. Grundzüge der Paläontologie (Paläozoologie). II. Abteilung. Vertebrata [Fundamentals of Paleontology (Paleozoology). Section II. Vertebrata]. Druck und Verlag von R. Oldenbourg, München 1-598.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Whitlock, J. A. 2011. A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 161:872-915.

Wieland, G. R. 1920. The longneck sauropod Barosaurus. Science, New Series 51(1326):528-530.

Wild, Rupert (1991). "Janenschia n. g. robusta (E. Fraas 1908) pro Tornieria robusta (E. Fraas 1908) (Reptilia, Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha)". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B: Geologie und Paläontologie. 173: 1–4.

Wilson, J. A., and M. B. Smith. 1996. New remains of Amphicoelias Cope (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Montana and diplodocoid phylogeny. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16(3, suppl.):73A.

Wilson, J. A., and P. C. Sereno. 1998. Early evolution and higher-level phylogeny of sauropod dinosaurs. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 5. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18(2 (suppl.)):1-68.

Wilson, J. A. 2002. Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136:217-276.

Xing, L., T. Miyashita, J. Zhang, D. Li, Y. Te, T. Sekiya, F. Wang and P. J. Currie. 2015. A new sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of China and the diversity, distribution, and relationships of mamenchisaurids. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35(1):e889701:1-17.

#Barosaurus lentus#Barosaurus#Dinosaur#Diplodocid#Diplodocoid#Factfile#Palaeoblr#Jurassic#Herbivore#North America#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#Sauropod

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s another treasure from my dinosaur trip to the Museum of Ancient Life in Lehi, Utah! A very unique posing of a Stegosaurus that has died, along with several Goniopholis (a type of ancient crocodile) who have come to scavenge. It’s the circle of life, baby! As a bonus, the setup also features a baby Stegosaurus on the ridge, and a derpy looking Pterosaur model flying overhead!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise and Fall of the Living Fossil - Issue 68: Context

blog tumbling : In May 1997, the same month that The Lost World: Jurassic Park debuted in the United States, the U.S. Postal Service released 15 gorgeous stamps depicting various dinosaurs and extinct reptiles. The stamps caused a sensation among dino enthusiasts and paleontologists alike. “We all rushed out to get them,” remembers Christopher Brochu, a paleontologist at the University of Iowa. As an expert on crocodiles and their ancestors (known collectively as crocodilians and crocodyliforms), Brochu was particularly ecstatic to see that one stamp featured Goniopholis, a crocodyliform from the late Jurassic. When he looked closer, however, he noticed a few oddities: The checkers on its tail, the shape of its scales, and the arrangement of its teeth were not quite right. This drawing, Brochu realized, was not based on fossils of Goniopholis, but rather on the contemporary Nile crocodile. “People think that to make a landscape look primeval, all you need to do is throw a crocodile into the mix—even a modern one,” Brochu says. “There’s this idea that crocodiles haven’t changed at all since the time of the dinosaurs, that they are so-called ‘living fossils.’ ” It’s a notion that’s often repeated in magazines, museums, and nature documentaries. But… Read More… http://dlvr.it/QwvTGN @robinravi

0 notes

Text

Crocodylo-Month, Day 10: Calsoyasuchus

During the Early Jurassic, crocodilians began to take on recognizably modern roles. The earliest known crocodylomorph that lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator is Calsoyasuchus, which lived 197 million years ago in Arizona.

Calsoyasuchus was not a direct ancestor of modern crocodilians. It belonged to the family Goniopholididae, which branched off from other types of crocodylomorphs in the Early Jurassic, and which went extinct after the Late Cretaceous. In addition, they possessed a number of more primitive characteristics reminiscent of their terrestrial ancestors, such as long forelimbs and forward-facing eyes.

I couldn’t find any images of Calsoyasuchus, so I used an image of a closely related crocodylomorph, Goniopholis. Image by Nobu Tamura.

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Vintage The World of Dinosaurs Stamps 1997 One Pane of Twenty Stamp 32 Cent Each.

0 notes

Text

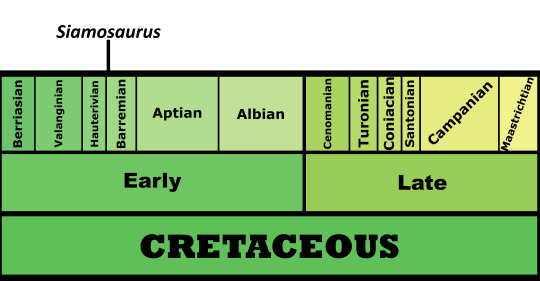

Siamosaurus suteethorni

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

Etymology: Reptile from Siam

First Described By: Buffetaut & INgavat, 1986

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Megalosauroidea, Megalosauria, Spinosauridae, Spinosaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 129 million years ago, in the Barremian of the Early Cretaceous

Siamosaurus is known from the Sao Khua Formation of Thailand

Physical Description: Siamosaurus is not known from extensive fossil remains - indeed, it is known from only teeth that are very similar to those of Spinosaurus, leading to its classification as a close relative. So, if it is a dinosaur like Spinosaurus, it probably would have been a bipedal theropod, with long front limbs ending in extensive claws for grabbing fish. Siamosaurus would have probably had a long, crocodile-esque jaw,and some sort of sail or hump on its back. It would have most likely been primarily scaly. Beyond that, we can’t be entirely sure what Siamosaurus would have looked like.

Diet: Siamosaurus would have primarily eaten fish.

Behavior: Like Spinosaurus, Siamosaurus would have spent most of its time near or in the water, hunting for fish and swimming about in its ecosystem looking for more food. It probably would have been at least somewhat solitary, given the difficulty of fishing as a lifestyle for shoreline animals - crocodilians and bears, for example, tend to fish alone. But, Siamosaurus probably would have been fairly active in lifestyle, and probably would have taken care of its young. It may have been semiaquatic, but this has been disputed for other Spinosaurs.

By Offy & PaleoGeekSquared, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Siamosaurus lived in a muddy, tropical forest, filled with a variety of hot-weather plants right on the equator. This ecosystem featured a variety of fish and sharks, including such famous ones as Lepidotes and Hybodus. These fish would have been ideal prey for Siamosaurus. Turtles were frequent along the river ecosystem, and may have also been fed upon by Siamosaurus. There were competitors, too - pseudosuchians such as Theriosuchus, Khoratosuchus, Goniopholis, and Siamosuchus. Other dinosaurs also made up the ecosystem, though none are particularly well known - the titanosaur Phuwiangosaurus, the iguanodonts Siamodon and Sirindhorna, the carnosaur Siamotyrannus, and the ornithomimosaur Kinnareemimus. The titanosaur Phuwiangosaurus, in particular, was very common in this environment.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Siamosaurus is difficult to place accurately in terms of phylogeny, given it is only known from teeth.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142.

Arden, T.M.S.; Klein, C.G.; Zouhri, S.; Longrich, N.R. (2018). "Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in Spinosaurus". Cretaceous Research. In Press.

Buffetaut, E.; and Ingevat, R. (1986). Unusual theropod dinosaur teeth from the Upper Jurassic of Phu Wiang, northeastern Thailand. Rev. Paleobiol. 5: 217-220.

Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Early Cretaceous, Asia)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 563-570.

#Siamosaurus#Siamosaurus suteethorni#Spinosaur#Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Megalosaur#Water Wednesday#piscivore#Eurasia#Cretaceous#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

200 notes

·

View notes