#gond art peacock

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Grace Peacock Gond Art Painting beautifully showcases the traditional Gond art style, featuring a vibrant peacock in intricate patterns and earthy tones. Symbolizing grace and beauty, this handmade piece captures the essence of Indian folk art, making it a stunning addition to any space that appreciates cultural elegance and detailed craftsmanship.

0 notes

Text

Gond Art: History, Elements and Stories

'Gond' comes from the Dravidian word 'kind,' which means 'green mountain.' Gond painting is a famous folk art form of the Gond tribal community of central India. It is a form of painting from the folk and tribal art of one of the largest tribes in India - the Gonds - who are mainly from Madhya Pradesh but can also be found in pockets of Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh and Odisha., The history of the Gond people is about 1400 years old. Mixed with a mix of mystery, patterns, colors and humor, these artworks reflect a modern psyche.

Elements of Gond Art

The untrained eye may confuse Gond art with Madhubani painting, Mithila distinct characteristics. The paintings use vibrant colors such as orange, yellow, blue and red and are made with artistically drawn lines and dots to bring them to life. Natural colors from various sources, like flowers, stones etc., are used to create these beautiful paintings.

Over the years, Gond artists have developed their own tools for working with various contemporary mediums and materials. They would first plot the points and calculate the volume of the images. These points will be connected to bring up an outer shape, which will then be filled with colors. Everything that comes to life is aesthetically transformed as they react to the immediate social situation and environment. The images are tattoos or minimalist human and animal forms which include chameleons, butterflies, elephants, cows, lions, fish, peacocks and other birds.

Though Gond paintings are centuries old, with time, this art form has gradually shifted from the mud walls of houses to canvas and paper. Apart from drawing inspiration from legends and myths, these paintings featured nature as their main subject. However, this painting style has other well-depicted subjects, including Hindu deities (especially Ganesha), the Tree of Life, and jungle scenes. With various motifs and design patterns, these paintings have attracted the attention of many people, including those from India, France, the UK and the US.

Stories and Symbolism in Gond Art

"Trees are of great importance in Gond art. For humans and animals alike – for animals and birds, trees are most important – to protect them from the sun in summer and rain during the monsoon season. Trees also provide nutrition and food," says artist Venkat Raman Singh Shyam.

The Ganja Mahua Tree tells the story of a Brahmin (high caste) girl and a Chamar (low caste) boy - when they fell in love, society did not accept them. So he renounced everything, went to the forest, and was later reborn as Ganja and Mahua trees. That's why it is said that Ganja and Mahua should not be consumed together because they can never be together.

Saja Tree: The Saja tree is worshiped by the Bada Dev (Elder God) and the Gond community.

Pakri tree: When new leaves bloom from this tree, the Gond community eats the greens made from these leaves, protecting them from many diseases and ailments.

Peepal Tree: The Peepal tree is where the deities (gods) reside, and thus, the Peepal tree is considered the most important.

Tamarind Tree: Tamarind tree also plays an important role for the tribal people as they use tamarind fruit for chutney and sell it for their livelihood. Many people of the Gond community set up platforms for the gods and goddesses under the trees.

Music in Gond communities

In the past, Gond artists were responsible for orally passing down the Gond kings' traditions through songs and instruments called 'Bana.'

They would invoke Lord Bada Dev on the saja tree by playing the flute and recording the genealogy of the Gond patrons in song. In return, they were given gifts of grain, clothing and perhaps even cattle or gold.

Similarities between Gond art and tribal art?

"Gond is similar to tribal art because tribals have their own stories as we do about creation, and they also make dashes and dots. Tribal art and Gond art have their connection because we are originally from the same continent of Gondwana from when there were only two continents, Gondwana and Laurasia. India and Australia came from Gondwana, and America came from Laurasia.

The performances, dances, rituals, and drinks they serve are similar to ours. Their surname is Marawi, while ours is Marawi. I spoke on the topic 'You are my brother, in you I found myself' at Monash University in Melbourne and the Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane." Gond master artist Venkat Raman Singh Shyam said.

Paints are usually derived naturally from charcoal, colored clay, plant sap, clay, flowers, leaves and even cow dung. That said, due to the lack of natural dyes, Gond artists have started using poster colors and canvas to paint.

The Gond painting resembles the Aboriginal art of Australia as dots are used in both styles to create the painting. There are different types of dots in both art forms. For tribal art, the points symbolize the field and dreams, while with Gond art, the shamans believe that particles of their bodies spread out into space to connect with spirits and create other bodies. It is an ancestral, poetic vision of the atom, joining the infinitely small into the infinitely large.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Gond Art paintings

Gond painting price, information, tutorial, images, history and gond art techniques

Today's Gond paintings have become quite popular because of the efforts by the Govt of India to promote and showcase the beauty of tribal art.There have been expo of Gond paintings in many region of the world . Gond paintings price between Rs 3000/- to Rs 50000/-

Today , many talented Gond artists works including Shubhi Jain can be seen on canvases in art galleries internationally.

Shubhi Jain mainly preferred the tree of life surrounded by deer figures .She features different kinds of birds too , while her signature pattern is tree almost erect and still . She takes 3 -21 days to make each painting.

In the eyes of a Gond artist , everything is sanctified and intimately connected to nature . Thus ,the unique oral narrative tradition of the Gond art is reflected in their paintings as well The work of Gond artists is rooted in their culture , and thus story - telling is a strong element of every painting .

However every artist today has a personal style and has developed a specific language within these narratives creating a richness of artfully forms and styles.

Who are Gond Tribes ?

Gond are one of the largest tribes in india and are Dravidian's whose origin can be traced to the pre -Aryan era , who are mainly from Madhya Pradesh and also found in some place of Andhra Pradesh , Maharashtra , Chhattisgarh and Odisha

The word gond comes from kond which means green mountains in the Dravidian idiom. About half of Gonds speak Gondi Languages , While the rest speak Indo - Aryan languages including hindi.

The Gond are also knowns as the Raj Gond The term was widely used in 1950s , but has now become almost obsolete , probably because of the political eclipse of the Gond Rajas. The Gondi language is closely related to Telugu , belonging to the Dravidian family of languages.

The recorded history of the Gond people goes back 1400 years , but considering that they inhabit areas where rock paintings dating to the Mesolithic have been found , their antecedents probably date back even further .

Many of the Gonds customs echo that of their Mesolithic for bearers .An obvious example of this is the custom of embellishing the walls of their houses , an activity that may originate in cave - habitation tradition of their forefathers.

What are the main festivals of Gonds ?

The Gonds paint their walls on festive juncture such as karva Chauth , Diwali , Ashtami , and Nag Panchmi , Gond painting delineate various celebrations ,rituals and man's connection with nature . The artists use natural colors extract from charcoal , colored soil , plant sap , leaves and cow dung .

How is Gond art made ?

Gond paintings can be best be described as 'on line work'. The creator makes sure to draw the inner as well as outer lines with as much care as possible so that the perfection of the lines has an immediate effect on the viewer .

Lines are used in such a way that it conveys a sense of movement to the still images . Dots and dashes are added to impart a greater sense of movement and increase the amount of detail.

In current scenario gond paintings aren't painted on walls and floors and are instead painted on canvas. easy to transport , carry and hang on a wall .

Due to paucity of natural colors in the current age , Gond artists have started to use poster colors .This combined with the use of canvas has made modern Gond paintings much more chromatic than its traditional counter parts.

Gond Art technique tips by artist 'Shubhi Jain'

" Hello art lovers first draw a rough pencil sketch then draw a black outline with use of bright flamboyant colors and with the help of lines, dots and dashes try to create a pattern of design of your own"

" Conventionally , the Gond paintings were done on mud walls with colors elicited from natural materials like soil , charcoal , cow dung and leaves "

" Most important Gond paintings as ' on line work '. Art is created out of carefully draw lines. Lines are used in such a way to convey a sense of movement to still images"

Quote by Gond artist 'Shubhi Jain'

" A painting shows a journey of artist without words"

This blog exclusively sponsored by ' THE NEON ART ACADEMY '

#gondart#gond painting#gond tribe lifestyle#gond art tree#gond art deer#gond art peacock#gond art birds#artsy#ArtGallery#artists on tumblr#ArtMuseum#painting#painter legend

0 notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Photo

【初めての芸術作品購入】 . "Peacock" Dilip Shyam 紙/アクリル/インク . _______________________________________________________ 銀座の「ギャラリー石」にて、インド中央部マディヤ・プラデーシュ州に住む先住民族「ゴンド族」が描くゴンドアートを観に行きました。 . 描��れた動物の溢れる生命表現と、平面的で削ぎ落とされた構図は、プリミティブであり、モダンでもある。 そして、発想の大胆さと、緻密な文様。 . 相反するものを融合するアジアらしい絵にすっかり魅了されました。ゴンドアートはヨーロッパでも高く評価されているそうです。 . ん〜〜〜なんといってもカワイイ♥ 世界に一枚しかない宝物。 . _______________________________________________________ #🇮🇳 #India #gond #modern #art #nativeIndian #peacock #インド #ゴンドアート #現代アート #インドの先住民族もネイティブインディアンって呼ぶのかしら?

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I saw a Peacock, with a fiery tail, I saw a Blazing Comet, drop down hail, I saw a Cloud, with Ivy circled round, I saw a sturdy Oak, creep on the ground, I saw a Pismire, swallow up a Whale, I saw a raging Sea, brim full of Ale, I saw a Venice Glass, Sixteen foot deep, I saw a well, full of men’s tears that weep, I saw their eyes, all in a flame of fire, I saw a House, as big as the Moon and higher, I saw the Sun, even in the midst of night, I saw the man, that saw this wondrous sight.

- Anonymous, before 1665

Artwork by Gond artist Ramsingh Urveti for the book “I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail,” published by Tara Books.

youtube

#ramsingh urveti#gond art#indian folk art#tara books#i saw a peacock with a fiery tail#poetry#picture books

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madhubani art paintings

Shop online Madhubani Indian traditional art paintings? beautiful handmade Folk and Tribal art paintings of Madhubani colors, Joyful Universe, Birds on Branches, Gond, Jungle animal, Bird Nest, Tree of Life black and white, Balamkari, Canvas, Mysterious, Peacock, Santhal tribe, Salvation, Companion, Saraswati Patachitra, Lakshmi, Fusion, wall art price. Worldwide Shipping, Shop Now!

https://thevinart.com/mystyle-madhubani/

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

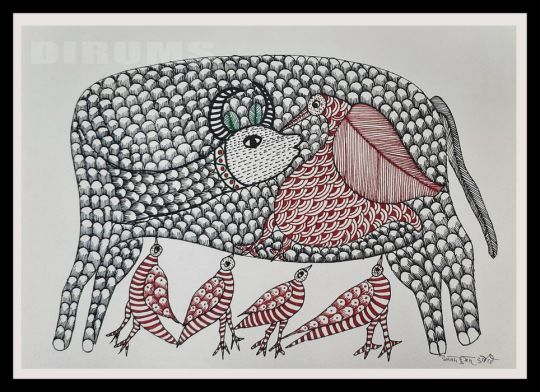

Original hand made gond painting showcasing peacock., brajbhushan Dhurve

From the village of Dindori in Madhya Pradesh, Gond artist Braj Bhushan Dhurwe creates art reflects the flora and fauna of his environment along with the customs and festivals of his tribe. His work is informed by the timeless tradition of Gond painting, portraying ritualized depictions of Gond. The artist inspirations came from the stories told by his elders, and his personal faith that the gods will be pleased by his art. His paintings exude in simplicity—a characteristic quality of tribal art—while emphasizing on the storytelling aspect of the work, rather than its realism. Modest in form, but striking in impression, Dhurve’s subjects are dark figures across the canvas creating an effect of striations and waves with their colorfully dotted forms. Under the guidance of the artist Bhadu Singh Dhurve, Braj Bhushan Dhurve began to transfer his paintings from the rough mud walls of his tribal home to paper and canvas in the 1990s. Today, the artist is recognized by TRIFED (Tribal Co-operative Marketing Development Federation of India Limited), Ministry of Textiles. His works have been exhibited in France, U.K., and extensively throughout India.

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-Original-hand-made-gond-painting-showcasing-peacock/993962/3719439/view

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Owl . Code : 052 Medium - Acrylic on paper Artist - Rita Shyam Style - Gond Size - 12x17 In . The owl is considered the most beautiful bird in Gond folktales. The tale goes to tell that though the Peacock was voted as the most beautiful bird in a voting poll amongst birds, she took too long to get ready on the day of the coronation. The owl thus stepped forward and proclaimed the title by convincing others that Owls are nocturnal and can move their heads all around which the peacock cant. The Owl was thus coronated the most beautiful bird in Gond folk tales of humor and wittiness. The Gond tribes live close to nature and their lives are intertwined with the jungle. They have many folk tales on nature and the wild life. The artist has been mentored and encouraged to use abstract styles in warli art form, creating unique artworks. . Painting from the series of The Gondwana Art Project - a social initiative to up-skill tribal artisans from Central India . #artoftheday #designconcept #owl #gondart #gondpainting #tribalartwork #tribalart #tribalartists #forestlife #craftsofindia #folkartist #folkart #ccdfindia #gondwanaartproject #designercollection #indiaartfair #aboriginalart #designstudio #graphicdesign #tribalpattern #sundeepbhandari #interiordesign #artandcraft #nature #visualart #designvisual #traditionalart #wildlifeart #creativeart https://www.instagram.com/p/CQx9h6mpljG/?utm_medium=tumblr

#artoftheday#designconcept#owl#gondart#gondpainting#tribalartwork#tribalart#tribalartists#forestlife#craftsofindia#folkartist#folkart#ccdfindia#gondwanaartproject#designercollection#indiaartfair#aboriginalart#designstudio#graphicdesign#tribalpattern#sundeepbhandari#interiordesign#artandcraft#nature#visualart#designvisual#traditionalart#wildlifeart#creativeart

0 notes

Text

Q&A with Pascale Petit

M: There is a family narrative that runs through the collection, as well as the underlying theme of environmental catastrophe and extinction. Can you speak to how these two concerns parallel or amplify each other? P: I write intuitively, guided by images, the song of the line, its dynamic, and by my excitement towards the subject. The draft has to feel true. When I write well, I am playing with all these elements, it’s a serious play, but I am in a childlike tranced state. The themes that emerge in the book appear almost as a by-product – they don’t lead it.

Tiger Girl reveals the cruelty of human beings in their treatment of non-human life, and each other. If I look back on my books, I suspect that most of them are asking this question: are humans essentially good or bad? Perhaps that’s why I’m driven to examine the way that people in power treat the powerless. I’ve tended to do this by holding a magnifying glass to my dysfunctional family, in particular on my parents and difficult childhood. In Tiger Girl I focus on the benevolence of my Indian grandmother, who took me in as a baby, then later, from the age of seven until fourteen. She didn’t have to do that, so in Tiger Girl she is a force for good, and the book is in a way a series of grandmother love poems. She is this saviour, who herself was saved. Her origins are a mystery, but I’ve been told that in Rajasthan where she was born, she was taken in by her father’s white family, while her real mother was the maid. I wanted to explore her heritage, her country, but most of all – I wanted to see a wild tiger as she had done as an infant, when one walked into her tent. So, I went to India to experience the wildlife, and fell in love with it; the national parks are brimming with animals and birds!

Going into the tiger forests in open jeeps is addictive! I’d wake at four, and be at the forest gate by five, waiting for it to open. Then the rush to find tracks, to catch a tigress patrolling her realm, the theatre of alarm calls that we’d be in the centre of, a sensurround of barks started by langurs at their treetop lookouts, and taken up by the deer. The tiger hidden, but there! But I soon realised what an immense struggle it is to keep the tigers alive, as well as all the other fauna – elephants, sloth bears, mongooses, owls and Indian rollers. Poaching is a constant threat. The parallel with my family story – how my grandmother was saved by her father, how I was saved by her from more years in an orphanage, and from the “poaching” of my parents on my body and soul, is a testimony to kindness and love. It’s kindness, love and empathy for wild animals that can save them from cruelty and abuse. We only have to empathise with them to know they suffer, and to stop the suffering. The situation in India is complicated, as in many wild parts of the world, by poverty. I’ve heard and read accounts by poachers who became forest guards, who went on to protect the tigers they once poached. Their guard-work is informed by their poaching experience; they know when and where incursions into the forest will occur. But what struck me was the indifference one guard divulged in his former life as a poacher. My account of his poaching methods is recorded in my long poem ‘In the Forest’. He needed the money for food. His need killed his empathy, his victim was just a means to make money, not a companion suffering being. The animal/human predicament echoes the dynamic between a person with power (such as a parent or president) and the powerless. M: That makes a good deal of sense given how I read the book, one image layering over the next in an intuitive, almost subconscious way. What was your revision process like, and how did you determine the arc of the book? P: I started writing Tiger Girl just after the Brexit referendum. My anxieties about citizenship and possible expulsion – I eventually applied and got British citizenship – reminded me of my grandmother’s situation, and how she’d had to conceal the fact that she was Indian. I hadn’t been aware of it when I lived with her as a child. All I could really remember were certain mysteries, her tiger stories, her speaking Hindi in her sleep. I started researching where tigers were in India, and read every tiger book I could find. I planned my first trip to Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan, followed by Kanha and Bandhavgarh National Parks in Madhya Pradesh, the tiger heartland. I went over twice, and would have gone more, but Covid-19 happened. I had no idea there’d be so many animals and birds – imagine discovering your heaven then realising it is under threat of vanishing. This is the situation we find ourselves in on this planet: the wild is a place of awe and wonder, but it’s vanishing even as we discover new species. So, what set out to be a personal quest for identity and heritage, became a story about the forests and their fauna. Of course, now, because of Covid-19, there are new threats to wildlife, not least because it’s a zoonotic virus that it is thought originated in bats, passed through a mammal such as the much-poached and probably soon-extinct pangolin, to humans. My personal experience of cruelty at the hands of parents gave me empathy with the animals that are tortured and killed. Are they the childhood of the planet? I’m terrified that we will end up as the only large mammals on Earth, our companions gone, their homes destroyed. It’s unbearable to imagine a world without forests or animals, so, throughout Tiger Girl, there are flashes of hope, clearings with sunlit birds or rare deer. There is also fire threaded through, simmering in the first poem ‘Her Gypsy Clothes’, becoming a roar in the final poem ‘Walking Fire’. None of this was planned, but as I was finishing the manuscript one year ago, our world seemed to be on fire, from California to the Amazon, to New South Wales.

My revision process varied wildly, some poems wrote themselves whole, especially ‘In the Forest’ and ‘Green Bee-eater’. Others needed many recasts. With ‘The Anthropocene’, I had the moving image of the planet as a bride wearing a peacock dress as soon as I saw the news items of the Chinese bride in hers. The image wouldn’t let me be, so those lines hovered on my desktop. But the song of the poem came later, after I’d read The Night Life of Trees from Tara Books, featuring art of the tribal forest artists, the Gond from Madhya Pradesh. I kept looking at the trees they’d printed, and reading the captions from their beliefs. One tree is called ‘The Peacock’, and the caption said “when the peacock dances in the forest, everything watches, and the trees change their form to turn into flaming feathers”. And that gave me my song. The stepped form on the page felt right and might suggest a bride’s train or poised waves. There was a particularly violent hurricane season last year as I was drafting it, so that became the theme, of climate change.

M: As someone who writes about animals--and who is enamored with them--I share your pain and terror at the thought of a future without them. How do you see the poems in Tiger Girl speaking to the poems in Mama Amazonica?

P: Tiger Girl features my grandmother and her tiger childhood, and Mama Amazonica is a portrait of my mentally ill mother as the Amazon rainforest. These two women hardly spoke to each other in the last years of their lives; they are in many ways opposites.

Both books juxtapose a family in crisis with the natural world in crisis, and link abuse of women and children with abuse of animals and forests. But I don’t set out to do this, it’s what the poems reveal. If I take the central poem of Tiger Girl, which is for me ‘In the Forest’, and compare it to the central poem of Mama Amazonica, which for me is ‘My Amazonian Birth’, Mama Amazonica is more hopeful of a human’s rebirth in the pristine rainforest, even if that rainforest is sick and broken. What happened between the writing of the two books was Trump’s increasingly anti-eco politics and the rise to power of Bolsonaro in Brazil, followed by the election of Boris Johnson in the UK and a general global rise of fascism and contempt for the natural world. Yet, the personal story in Tiger Girl, of my Indian grandmother saving me from my abusive parents, is hopeful. And there are splashes of hope throughout the book. There has to be hope. The human psychodrama is hopeful, because what my grandmother did, taking me in for two years as a baby, then for seven years as a child, passed her strong spirit on to me and supported me all my life. Yet, even there, there is betrayal, the story of her returning me to my mother, twice, while Mama Amazonica is both my abused and mentally ill mother, and the abused mother-forest. The human drama mirrors the drama that’s unfolding on our planet – a struggle for the oppressed wild to survive. In India, that struggle is an old one, where the plenitude of charismatic megafauna is in conflict with the dense human population and poverty. The only relatively safe forests are in national parks, yet even there, there is poaching. As for my writing journey – the ‘tiger girl’ of my Indian grandmother is a character I’ve rarely written about before, though it is she who opens my very first collection Heart of a Deer, published in 1998, with the poem ‘Mirador’, that also tells the story of her death on fireworks night. In Tiger Girl I wanted to explore her spirit, how nourishing the older woman figure was, who appeared “like a goddess to me”.

M: Are there any particular texts or works of art with which you feel the book is in conversation?

P: Tiger Girl is mainly in conversation with two artists. As I began writing the book, I discovered installations by the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, and felt very excited by them. I was first attracted to his work because of his installation Inopportune: Stage Two, of nine life-size replicas of tigers leaping through the air, shot and transfixed mid-leap by bamboo arrows. I almost felt at this stage that his work would dominate the book. I wanted to write my equivalents of his firework events. In the end, only two poems remained in my final cut: Ethereal Flowers, which I turned into ‘Her Flowers’, and Sky Ladder, which became my ‘Sky Ladder’. That he worked with gunpowder and fireworks and a ladder made of fireworks that explodes into the sky, felt a direct link to my grandmother’s death on Guy Fawkes night. I watched his film Sky Ladder, and my poem came out of the way he dedicated the event to his 100-year-old granny. The second main artist Tiger Girl is in conversation with is the late Pardhan Gond painter Jangarh Singh Shyam, founder of Gond art, whose tribe know the Central Indian forest secrets. Like him, I’m obsessed with deer and their antlers and how antlers mirror a forest. He died tragically early, but I wanted to honour him, so I wrote a poem for him, ‘Barasingha’, about the endangered twelve-tined swamp deer and how his life was changed after coming face to face with one. My cover art The friendship of the tiger and the boar is by him and I love how my publisher Bloodaxe has wrapped the Gond tree around the back cover. As well as these two artists, a poem early in the book, ‘Surprised!’ is a response to Henri Rousseau’s painting, Surprised! (Tiger in a Tropical Storm) – I love his work! Other poems, such as ‘The Umbrella Stand’, were influenced by Jim Corbett’s tiger hunting books. William Blake hovers in the background of ‘In the Forest’ and ‘Wild Dogs’. ‘For a Coming Extinction’ is a response to the same titled poem by W. S. Merwin. In the poem ‘Her Staircase’, I managed to write about my grandmother’s fatal staircase through a re-imagining of the installation Staircase III, by the Korean artist Do Ho Suh, which I’d spent hours sitting beneath while tutoring poetry courses at Tate Modern. Two poems are even dedicated to my first love John Keats and his forested worlds.

0 notes

Text

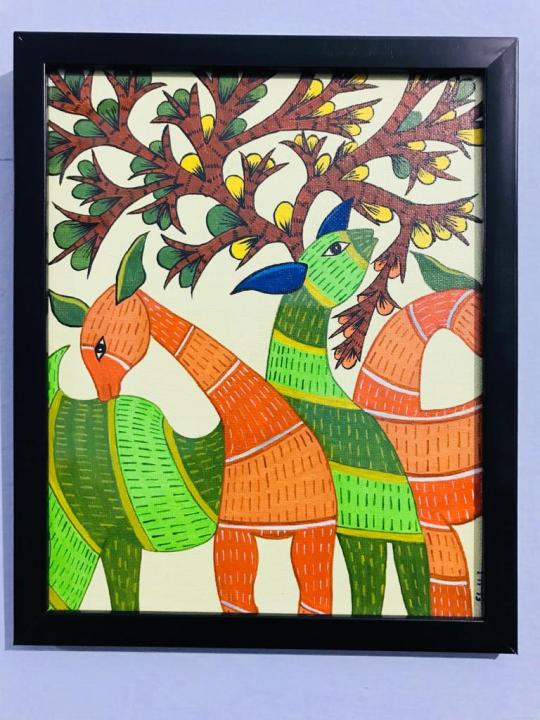

Elevate your home interior with the captivating beauty of Gond Art, curated by SAAJ. Our collection features meticulously crafted handmade Gond paintings, each framed to perfection, ready to adorn your living space with timeless elegance. Inspired by the rich cultural heritage of the Gond tribe, these artworks celebrate the harmony between humans and nature, bringing a sense of serenity and wonder to any room. Whether you’re drawn to the graceful Gond painting deer or the vibrant Gond painting peacock, our curated selection offers something for every discerning art lover. Add a touch of tradition and creativity to your home decor with Saaj’s framed handmade Gond art, and embark on a journey of discovery through the enchanting world of Gond tribal painting.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

// Morni // PEACOCK in Gind art inspired artwork . . This was a peacock that I used to draw when I was 10-11 yrs old. Thought why not make it again and apply the Gond Art distinctive patterns.. !? And this is the result! How is it? . . . #gondartpainting #indianfolkart #folkartofindia #indianart #newartist #learningnewskills #newskills (at Kolkata - The City of Love) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBnsDY7l7CR/?igshid=jxkxj2o9ac33

0 notes

Video

youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAkQsePo2Bo

LIVE BRIEF: Information Search

Poetry Picture Book of I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail .

Tara Books share their visual exploration of the 17th century English trick poem I Saw a Peacock with a Fiery Tail.

With art by Ramsingh Urverti from India's Gond tribe & pioneering book design by young Japanese-Brazilian designer Jonathan Yamakami, the book plays with the ways in which meaning is created.

The picture book in this video is similar to the poem analysis mentioned in my last post. They both link the end of one sentence with the beginning of the next sentence.

Reference:

Tara Books . 2012. I Saw A Peacock With A Fiery Tail. [online] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAkQsePo2Bo> [Accessed 23 February 2020].

0 notes

Photo

First time tried "gond art" #fun #ruralindia #tribalart #gondart #peacock #artist #instagram 🎨❤ #artoftheday #artonthego #watercolor_guild #worldwatercolorgroup #watercolorworldgroup #artclubseven #artistoninstagram #artphilosophydt #watercolorblog #watercolourillustration #watercolor_art #watercolor_daily #watercolor_guide #watercolormonth #illustrations #illustratorsoninstagram #illustration_daily #dailyartpromotion #dailyart #dailydrawing @watercolor_daily @illustrationsoul @artphilosophyco (at Varsova Beach) https://www.instagram.com/p/ByqOXLSpRgu/?igshid=slw62fb7fyy2

#fun#ruralindia#tribalart#gondart#peacock#artist#instagram#artoftheday#artonthego#watercolor_guild#worldwatercolorgroup#watercolorworldgroup#artclubseven#artistoninstagram#artphilosophydt#watercolorblog#watercolourillustration#watercolor_art#watercolor_daily#watercolor_guide#watercolormonth#illustrations#illustratorsoninstagram#illustration_daily#dailyartpromotion#dailyart#dailydrawing

0 notes

Text

Raja Ravi Varma: portrait of an artist

How we see Indian Goddess Saraswati today, with a peacock by her side or an elephant with a garland at its trunk – in reverence to a splendid Lakshmi who’s risen on a lotus with poise – is thanks to Realist painter, Raja Ravi Varma. Culture Trip discovers the man who created Indian calendar art.

Born in 1848 in the village of Kilimanoor, Kerala, Ravi Varma belonged to royal lineage. Lore has it that he was spotted drawing pictures on the walls of his house by his uncle. The uncle brought him to the royal palace of Thiruvananthapuram where the young Ravi Varma was instructed in art. The palace exposed him to the various Indian and Western styles of the times.

Lakshmi | Raja Ravi Varma/Wiki Commons

Nineteenth-century India was popular in the West for its miniature paintings. These were majorly Mughal and Rajput paintings – the former documenting their reign while the latter celebrated Hindu deities, done usually on cloth with colours made from minerals and ink. Other forms were majorly regional – Pattachitra – a cloth-based scroll painting in Orissa, Madhubani art from Bihar, or the Thanjavur painting originating in Tanjore. While they all varied in form, a thread of commonality weaved them – the flat rendition of the figures.

Oil as a medium was just being introduced, and not many who knew the technique. Ravi Varma taught himself the medium by observing a Dutch painter, Theodor Janson, who was on a visit to the court. He grew to be the celebrated Raja Ravi Varma, feted as the father of modern Indian art for primarily two reasons. The first was that he was the first one to fuse European academic techniques with Indian sensibilities.

Saraswati | Raja Ravi Varma/Wiki Commons

Adopting realism, Ravi Varma focused much on the details, the play of light and shadows, adding depth by using perspective in his paintings. Suddenly the folds of a sari fluttered, the hair coiled, and the eyes expressed a longing. With thicker strokes, the jewels that generously adorned his subjects shimmered in a perceived angle of light. His paintings are an abundance of life – trees heavy with fruits and flowers, waters resplendent with its many hues, and the subjects almost waiting to blink their eyes and continue their motion.Jatayu, in a bid to save Sita from Ravana, is a grand expression, as is Shakuntala’s longing stance with her head turned in the glance that narrates her legend with Dushyant. A very doting Arjuna coaxing Subhadra, or Menaka in a bid to distract Vishwamitra are stories captured in a frame. This — an augmentation of abundance displayed in most Indian paintings — ranging from miniatures to Kalamkari to Gond.

Ravi Varma’s expeditions through the country’ ever-changing topography is reflected in his large body of work. His quest also got a fillip with the railways that were being laid down in the country at that time. Lesser celebrated over the century, his younger brother Raja Raja Varma, a fine painter in his own right, assisted Ravi Varma and managed his businesses. Rupika Chawla, who authored Raja Ravi Varma: Painter of Colonial India, points out that Ravi Varma was conscious about his clientele — the princes and the dewans he portrayed — an ambitious mix that made him one of the most sought-after artists. Besides being one of the finest Indian artists to do portraits, Ravi Varma made his niche with the pauranic paintings that have made him so popular.

Often reckoned as the father of Indian calendar art, Raja Ravi Varma exquisitely breathed life into the Hindu mythical characters. Up until then, most of these characters that were painted two dimensional, and the deities were recognised only by their iconography. Owing to modern realism, Raja Ravi Varma offered them a face with which to be identified. Suddenly all those episodes from the epics that so far were painted as various Pattchitra or carved in stone came alive — in flesh and blood.

Krishna as Envoy | Raja Ravi Varma/Wiki Commons

The second reason that made the painter so remarkable was his vision – he founded a printing press in Mumbai in 1894 with the help of a German expert Fritz Schleicher that churned out inexpensive oleographs of his paintings. Suddenly, the bazaars were inundated with posters of a plethora of deities. God descended from the temple stone and made itself comfortable in small homes in dingy gullies. If his gorgeous portraits made him a blue-eyed artist for his crowned patrons, his cheap prints made him a commoner’s painter.

His oeuvre of pauranic paintings was instrumental in constructing a national consciousness. It was also at a time in India’s chronology when national sensibilities were taking root. His Veda-reflective art gelled with the momentum, gaining popularity and at the same time feeding the consciousness. This is perhaps one reason why his equally talented brother Raja Raja Varma, a landscape artist, couldn’t muster the recognition his brother did. Painter A. Ramachandran, who was the force behind a grand exhibition in 1993 that revived the idea of Raja Ravi Varma as the father of modern Indian art, fell upon a copy of Raja Raja Varma’s pleasingly written diary. Rupika Chawla explains how in one of the excerpts, Raja Raja Varma writes: ‘Today I painted the pillar in Hansa Damayanti,’ while Ravi Varma painted Damayanti.

It’s interesting to note how Indian cinema was seeded in Raja Ravi Varma’s story, of course owing to global technological advancement. A young photographer, Dhundiraj Govind Phalke, joined Ravi Varma at his press, excelling in lithographs and oleographs. A little later he set up his own press before eventually reeling India’s first moving picture – Raja Harishchandra in 1912. Raja Ravi Varma passed away in 1906.

Jatayu Vadha | Raja Ravi Varma/Wiki Commons

For decades after his death, his prints continued to adorn the walls of middle-class homes; however, soon after, other schools of art came forth. The Bengal School of art, as part of the nationalist movement, reacted sharply against Raja Ravi Varma’s European academic style of painting. Along the same line, a few art historians condemned his work for the reasons that otherwise made him so noteworthy – mixing Western academic techniques with Indian subjects.

Hansa Damyanti | Raja Ravi Varma/Wiki Commons

Nonetheless, in his heyday, the globally known, much awarded artist set the visual language for India. He set the template for an enormous sea of Hindu visual religious sensibilities from prayer books’ covers to large portraits for temples and eventually a base for the next craft — film/TV to build itself upon. Unknowingly though. the visual language proliferated — from match-box labels, tin sweets boxes, political posters, calendar art to early Indian cinematic aesthetics, his influence continues to linger. Many even laud him as the father of Indian advertising, and the pop culture of the day love to idolise him as the father of Indian kitsch.

Published at The Culture Trip

#art#narrative#painters#india#nineteenth century#raja ravi varma#Hindu#mythology#printing#revolution#culture#study

1 note

·

View note

Photo

An alluring Gond Art of two peacocks with the fine dots and dashes in two minimal colors. Artist - Ramesh Tekam Size – 8” x 11” Medium – Natural Colour on Paper

http://www.worldarthub.com/gond-art-14527.html #paintings #art #Natural_Colour_on_Paper #worldart #Peacocks

0 notes