#giving corn to livestock isn’t taking away any resource of value from humans

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

So anyway you repeatedly say we only feel corn husks and similar inedible parts to cattle but Never add a source to back it up. Having worked on farms I’m afraid for the most part the feeds I’ve seen have been parts entirely edible to humans. And like fuck man 5% of all grown soy is fed to humans or however the stat goes, do you really think the remaining 95% is inedible? really?

Anyway yeah I’m asking for a source here cause I don’t want to add this on to months old post

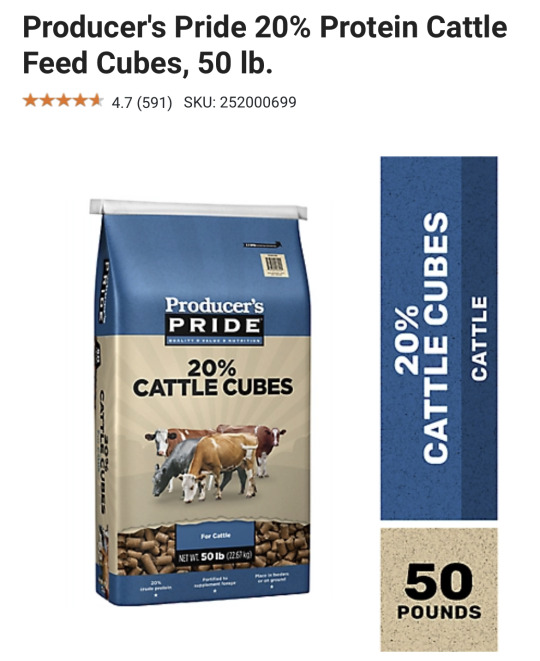

Ingredients such as “grain by-products” are referring to the husks, stalks, and other “green” parts of the plant that we humans don’t actually have the digestive capabilities to eat. The breakdown of most livestock feeds looks like the above when you actually take a look at it.

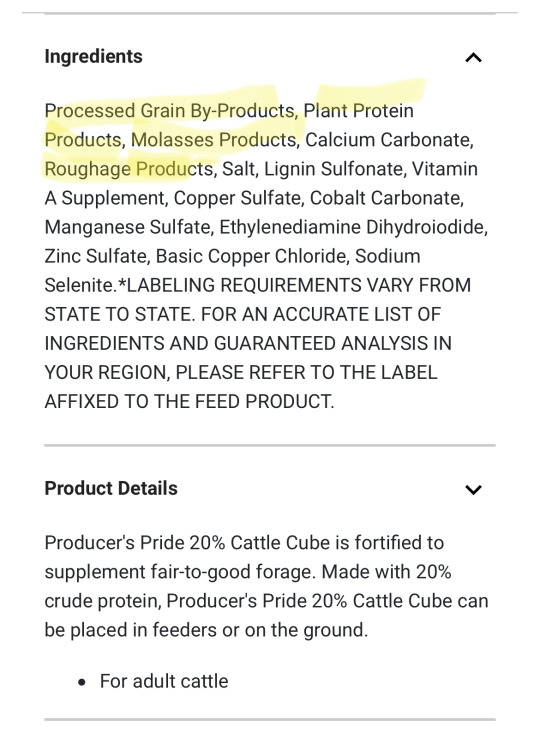

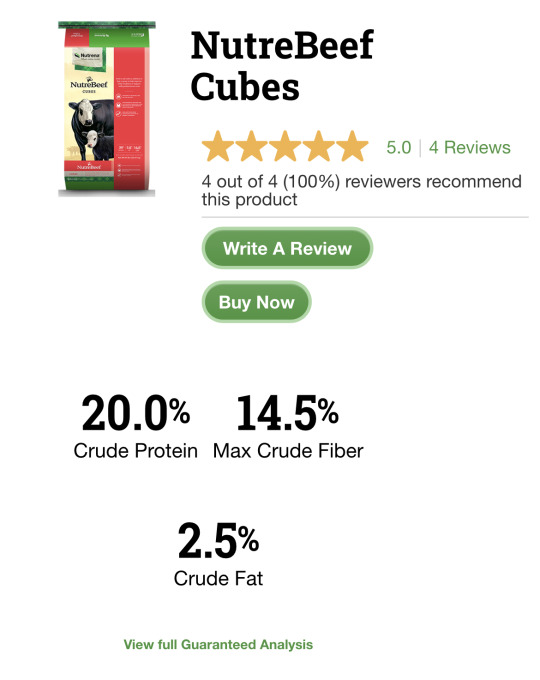

Different cattle feed, similar ingredients. Still primarily things that, and I have to stress this, you cannot eat. This one is slightly higher in quality and does indeed have actual grain products included. Some of those are edible to humans. Some are not. Generally cattle are fed cattle cubes with supplemental mineral licks and hay. Some also supplement with whole corn, but I can gladly assure you that corn is not in short supply and even if all the corn sold to animal feed was donated to the poor, you can’t actually live off of corn because there’s very little nutrition in it. Hence why in both human and animal food it’s typically seen as a filler ingredient. Keeps the mouth busy with a meal without making your stomach feel full and you end up eating more without feeling satisfied.

Soybeans are really only often used in feed for pigs because they’re a great source of protein for these animals. I would state that soy is also a terrible option to use as an emergency food for humans in need because while, yes, it is indeed a healthy bean, it’s also one of the top eight foods that humans are frequently allergic or intolerant towards. I’d also ask you for whether your 5% of all grown soy statistic is referring to the beans or the entire plant because yeah the beans are the edible part. The rest of the plant isn't especially healthy for humans to eat. I would say the beans are around 5% of a mature soy plant sure.

#No offense anon but when you come here with ACTUALLY MOST OF WHAT FARM COWS EAT IS HUMAN FOOD and bring up SOY in the discussion of COWS#I somewhat doubt you actually have much experience farming#because no actually cattle benefit from the green parts of the plant more than the bean parts in most cases#corn is used as a cheap supplemental feed because it’s cheap and it’s cheap because there’s so so SO much of it#And corn isn’t grown in special livestock only plantations when it’s used as feed as opposed to human food either#corn is grown en masse and processed and then sold to various companies which use the corn for various things#if animal feed companies stopped buying corn and that corn was instead bought by human food companies#that doesn’t mean corn would be any more or less accessible to the hungry#because it would go to grocery stores and TV dinner companies and sauce companies and soda companies and so on#and it would still be sold same as always#world hungerTM isn’t caused because people can’t afford corn#corn is dirt cheap and most people can afford it#it’s just barely a step above eating sand and you can’t live off of it#I’ve gone a few days only eating corn products because they were cheap#and shocking no one I had no energy and felt just as hungry after each bowl as I had before the last#people cannot survive off of that#giving corn to livestock isn’t taking away any resource of value from humans#sorry it just isn’t

333 notes

·

View notes

Link

Written by R. Ann Parris on The Prepper Journal.

Preppers can reap some big rewards by applying some of the habits of successful market gardeners and small farmers to our home gardens.

See, they have an eye on profit, which means an eye on efficiency. Most preppers aren’t looking at cash income from the garden, and scale matters even in for-profit growing, so there are some common practices we should actively avoid, but there are plenty that can save us time and resources.

That’s precious enough for now, and will be even more so any time our spending power is limited.

Establishing a Market

Before planting, successful market growers tend to have established their markets. It could be farmer’s markets, tailgate sales, roadside stands, restaurants, grocery outlets, or an ag professional who compiles orders for those latter from numerous local farms. Each market requires figuring total produce needed, and working backwards to planting dates so they can be served. The growers who wing it without either step tend to make less profit.

We want to emulate the first group.

We don’t have to worry about diversification or coolers of product that didn’t move because restaurants went under or weather kept the public from shopping, but it’s the same general concept.

We want to start out with an idea of our end goals in types of produce – how much we want for fresh eating and preserving – and from there work backwards to harvest goals, and have an idea of when we’ll be harvesting.

Covers

One thing almost all market growers do, from tiny backyard operations to folks cultivating in excess of 2-5 acres, is invest in row covers.

Usually, there are several in play – a mesh or cloth cover used to prevent insect access, which can also function as frost protection, and plastic sheeting used for cold protection.

Those covers add too much time to the period when a cultivated plot can remain in production for most professional growers to skip the investment. They may start small and add to it incrementally, but they get them.

In addition to plant covers, market gardeners also regularly cover their soil during dormant periods.

That patch we were just growing in is precious. We want to keep as many nutrients and soil amendments in place as possible, and prevent as many weed seeds as possible now that we’ve spent hours a day/week/month weeding and conditioning it. However long it will be between plantings, especially the smaller ag operations get it covered.

Pros are mostly going to go to poly silage tarps sooner or later.

For home growers, anything goes. Baby pools, straw, cardboard, a cover crops, salvaged wall paneling, leaves, heavy-duty curtains, thick blankets, wood chips, newspaper weighted with sticks – anything that doesn’t run away fast enough. Flip the wheelbarrow over a patch, park the mowers at the ends, whatever it takes to cover as much as we can, best as we can.

Really. Whatever it takes.

Hedge Seeding/Planting

Whether they’re direct sowing or transplanting, growers regularly start an extra set of seed to fill in any gaps that appear. It gives a uniform harvest and makes the best use of space.

This video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyNacaaUWsI demonstrates market garden practices for beets that applies to preppers, to include extra seed sets. The indicator crop demo’d with radishes is also a biggie – and on most home scales can be harvested for spicy sprouts or spaced out more for the roots.

Exceptions also apply here.

For a super small gardens and those feeding even 5-8 people, the predictable, consistent yields and turns from a whole vegetable bed at once isn’t as vital. Having a 2’x3’ or even a 30”x25’ patch at different stages of development doesn’t affecting our harvest efficiency or totals that much.

There are also plants that will basically catch back up, especially if we have more than 100 days to our growing seasons. Indeterminate squash and pole or bush beans are examples where even if they don’t reach the same total yield, replacing a non-starter with seed with a 10-21 day gap instead of having same-age transplants doesn’t greatly affect our harvest or space use.

There are also cases where, due to stronger light and warmer soils, fill-in-the-gap direct-sown seeds will catch up to buddies that were started under cold frames or planted as soon as the soil was warm enough.

It’s typically the crops like salads and small tubers and roots, that are both densely planted and faster-growing (35-65-day harvest ranges), where we’ll want to have backups to transplant if there are holes. Otherwise, we’re potentially “losing” the yields that empty space would have produced.

Big-time commercial growers will accept losses – like expecting a certain ratio of blanks in a corn field. Smaller growers, even the professionals, can’t afford it.

Avoid Thinning

Now, there are absolutely exceptions and scale totally matters on this one, but… Thinning is wasteful. Market growers and preppers in a busy world or in a world with reduced or nonexistent outside resource and are in lockstep on waste – we want to minimize loss wherever we can.

Both daily hours and seed are finite resources. For most of us, so is both growing space and growing season.

If we’re thinning, we’ve spent time and resources planting unnecessary amounts. Then we spent more time (and possibly additional resources) pulling them out to avoid overcrowding.

We also “spent” soil fertility on them (we’re moving homemade compost or manure around, or are buying and spreading fertilizers, which those seedlings may have started sucking up). We may have pumped extra water for them. That’s additional time and resources used for something we’re pulling out at 1-12”.

Especially if the trimmings are laying in a field, hitting compost, or represent such a low fresh feed amount we’re not adjusting anything for livestock �� that’s not making use of a byproduct. It’s just extra work and resource waste.

There are exceptions. Planting schemes that make it fast and easy to harvest edible seedlings for human or livestock consumption works for most small-scale growers. Gardeners with truly limited growing season and who are super-crunched on space but have the time and copious seed are also exceptions.

High seeding rates for plants with low germination is a given – that’s not waste at all. If they’re doing the job of a cover, where having denser plantings actually lets us save time and improves our harvest because it limits weed competition, that’s different, too.

Business Analysis

Any good organization tracks expenditures and results, sports teams to charities to production and services. It’s easier for us than market growers, here, too, though. We’re just going to cruise our pantry stocks and make notes (actual notes).

If we ran out of tomatoes, we want to plant more and-or trial some alternatives and-or increase types to avoid a big shortage if it’s a bad season. If we have more left from the previous season than we want when we start canning/drying again, we assess how many extras we have, and decrease.

(If I want to reduce pantry stock by 30% next year, I’d only decrease planting for a 20-25% reduction in case it’s a bad year. I’d rather decrease again the year after than run short.)

If we still have a few as we’re canning/drying more, we’re on the money and trials will be solely about increasing variety, efficiency, or productivity.

Professional growers must spend additional time tracking and crunching numbers on whether a crop type is worth growing or not, outlay in pest control and fertilizer and water, labor hours, and planning ahead for infrastructure maintenance.

Ideally we’d do the same there, as well. We just have a different baseline for profitability.

Seed is a cost they factor as well, especially since the pros aren’t keeping back their own seed. Yields by variety and finding the ideal seeding rate can hugely affect their business. That’s one we want to dial in, too, as much as possible.

We also both consider packing and packaging, just differently. Our other infrastructure and skills will affect where we most want to concentrate on post-harvest processing and storage.

Ask For Help

It’s a great time to be a market grower. Small urban and suburban farming is exploding right now. Those growers have a lot riding on their success. Since they can’t risk repeatedly failing, they ask for help.

And, the climate being what it is, usually they find it. Like us, they have to cull through a lot of information, find answers from people growing in the same environmental conditions and styles they are, but it’s largely a supportive community.

Small-Farm Market Grower Strategies

In this golden internet age, we can easily find blogs, Facebook groups, and YouTube channels produced by market gardeners. Some of them are especially useful for preppers with tight land limits as urban and suburban ag continue to enjoy increased attention.

Remember, though, that while many of the tricks of the trade apply to balconies and backyards, our bottom line is different – they need dollars and cents, and we’re trying to maximize food value. That means that especially what we grow, and how much of it, is going to be significantly different.

Also bear in mind there are also planting styles, medias, and schemes that can be very efficient and profitable at a small scale that wouldn’t work for market growers.

Mostly, though, we share a focus on making our efforts profitable. That makes professional-level strategies an excellent study while practicing our survival gardens.

Follow The Prepper Journal on Facebook!

The post Market Garden Strategies for Survival Gardens appeared first on The Prepper Journal.

from The Prepper Journal Don't forget to visit the store and pick up some gear at The COR Outfitters. How prepared are you for emergencies? #SurvivalFirestarter #SurvivalBugOutBackpack #PrepperSurvivalPack #SHTFGear #SHTFBag

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Market Garden Strategies for Survival Gardens

New Post has been published on https://outdoorsurvivalqia.com/trending/market-garden-strategies-for-survival-gardens/

Market Garden Strategies for Survival Gardens

Written by R. Ann Parris on The Prepper Journal.

Preppers can reap some big rewards by applying some of the habits of successful market gardeners and small farmers to our home gardens.

See, they have an eye on profit, which means an eye on efficiency. Most preppers aren’t looking at cash income from the garden, and scale matters even in for-profit growing, so there are some common practices we should actively avoid, but there are plenty that can save us time and resources.

That’s precious enough for now, and will be even more so any time our spending power is limited.

Establishing a Market

Before planting, successful market growers tend to have established their markets. It could be farmer’s markets, tailgate sales, roadside stands, restaurants, grocery outlets, or an ag professional who compiles orders for those latter from numerous local farms. Each market requires figuring total produce needed, and working backwards to planting dates so they can be served. The growers who wing it without either step tend to make less profit.

We want to emulate the first group.

We don’t have to worry about diversification or coolers of product that didn’t move because restaurants went under or weather kept the public from shopping, but it’s the same general concept.

We want to start out with an idea of our end goals in types of produce – how much we want for fresh eating and preserving – and from there work backwards to harvest goals, and have an idea of when we’ll be harvesting.

Covers

One thing almost all market growers do, from tiny backyard operations to folks cultivating in excess of 2-5 acres, is invest in row covers.

Usually, there are several in play – a mesh or cloth cover used to prevent insect access, which can also function as frost protection, and plastic sheeting used for cold protection.

Those covers add too much time to the period when a cultivated plot can remain in production for most professional growers to skip the investment. They may start small and add to it incrementally, but they get them.

In addition to plant covers, market gardeners also regularly cover their soil during dormant periods.

That patch we were just growing in is precious. We want to keep as many nutrients and soil amendments in place as possible, and prevent as many weed seeds as possible now that we’ve spent hours a day/week/month weeding and conditioning it. However long it will be between plantings, especially the smaller ag operations get it covered.

Pros are mostly going to go to poly silage tarps sooner or later.

For home growers, anything goes. Baby pools, straw, cardboard, a cover crops, salvaged wall paneling, leaves, heavy-duty curtains, thick blankets, wood chips, newspaper weighted with sticks – anything that doesn’t run away fast enough. Flip the wheelbarrow over a patch, park the mowers at the ends, whatever it takes to cover as much as we can, best as we can.

Really. Whatever it takes.

Hedge Seeding/Planting

Whether they’re direct sowing or transplanting, growers regularly start an extra set of seed to fill in any gaps that appear. It gives a uniform harvest and makes the best use of space.

This video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyNacaaUWsI demonstrates market garden practices for beets that applies to preppers, to include extra seed sets. The indicator crop demo’d with radishes is also a biggie – and on most home scales can be harvested for spicy sprouts or spaced out more for the roots.

Exceptions also apply here.

For a super small gardens and those feeding even 5-8 people, the predictable, consistent yields and turns from a whole vegetable bed at once isn’t as vital. Having a 2’x3’ or even a 30”x25’ patch at different stages of development doesn’t affecting our harvest efficiency or totals that much.

There are also plants that will basically catch back up, especially if we have more than 100 days to our growing seasons. Indeterminate squash and pole or bush beans are examples where even if they don’t reach the same total yield, replacing a non-starter with seed with a 10-21 day gap instead of having same-age transplants doesn’t greatly affect our harvest or space use.

There are also cases where, due to stronger light and warmer soils, fill-in-the-gap direct-sown seeds will catch up to buddies that were started under cold frames or planted as soon as the soil was warm enough.

It’s typically the crops like salads and small tubers and roots, that are both densely planted and faster-growing (35-65-day harvest ranges), where we’ll want to have backups to transplant if there are holes. Otherwise, we’re potentially “losing” the yields that empty space would have produced.

Big-time commercial growers will accept losses – like expecting a certain ratio of blanks in a corn field. Smaller growers, even the professionals, can’t afford it.

Avoid Thinning

Now, there are absolutely exceptions and scale totally matters on this one, but… Thinning is wasteful. Market growers and preppers in a busy world or in a world with reduced or nonexistent outside resource and are in lockstep on waste – we want to minimize loss wherever we can.

Both daily hours and seed are finite resources. For most of us, so is both growing space and growing season.

If we’re thinning, we’ve spent time and resources planting unnecessary amounts. Then we spent more time (and possibly additional resources) pulling them out to avoid overcrowding.

We also “spent” soil fertility on them (we’re moving homemade compost or manure around, or are buying and spreading fertilizers, which those seedlings may have started sucking up). We may have pumped extra water for them. That’s additional time and resources used for something we’re pulling out at 1-12”.

Especially if the trimmings are laying in a field, hitting compost, or represent such a low fresh feed amount we’re not adjusting anything for livestock … that’s not making use of a byproduct. It’s just extra work and resource waste.

There are exceptions. Planting schemes that make it fast and easy to harvest edible seedlings for human or livestock consumption works for most small-scale growers. Gardeners with truly limited growing season and who are super-crunched on space but have the time and copious seed are also exceptions.

High seeding rates for plants with low germination is a given – that’s not waste at all. If they’re doing the job of a cover, where having denser plantings actually lets us save time and improves our harvest because it limits weed competition, that’s different, too.

Business Analysis

Any good organization tracks expenditures and results, sports teams to charities to production and services. It’s easier for us than market growers, here, too, though. We’re just going to cruise our pantry stocks and make notes (actual notes).

If we ran out of tomatoes, we want to plant more and-or trial some alternatives and-or increase types to avoid a big shortage if it’s a bad season. If we have more left from the previous season than we want when we start canning/drying again, we assess how many extras we have, and decrease.

(If I want to reduce pantry stock by 30% next year, I’d only decrease planting for a 20-25% reduction in case it’s a bad year. I’d rather decrease again the year after than run short.)

If we still have a few as we’re canning/drying more, we’re on the money and trials will be solely about increasing variety, efficiency, or productivity.

Professional growers must spend additional time tracking and crunching numbers on whether a crop type is worth growing or not, outlay in pest control and fertilizer and water, labor hours, and planning ahead for infrastructure maintenance.

Ideally we’d do the same there, as well. We just have a different baseline for profitability.

Seed is a cost they factor as well, especially since the pros aren’t keeping back their own seed. Yields by variety and finding the ideal seeding rate can hugely affect their business. That’s one we want to dial in, too, as much as possible.

We also both consider packing and packaging, just differently. Our other infrastructure and skills will affect where we most want to concentrate on post-harvest processing and storage.

Ask For Help

It’s a great time to be a market grower. Small urban and suburban farming is exploding right now. Those growers have a lot riding on their success. Since they can’t risk repeatedly failing, they ask for help.

And, the climate being what it is, usually they find it. Like us, they have to cull through a lot of information, find answers from people growing in the same environmental conditions and styles they are, but it’s largely a supportive community.

Small-Farm Market Grower Strategies

In this golden internet age, we can easily find blogs, Facebook groups, and YouTube channels produced by market gardeners. Some of them are especially useful for preppers with tight land limits as urban and suburban ag continue to enjoy increased attention.

Remember, though, that while many of the tricks of the trade apply to balconies and backyards, our bottom line is different – they need dollars and cents, and we’re trying to maximize food value. That means that especially what we grow, and how much of it, is going to be significantly different.

Also bear in mind there are also planting styles, medias, and schemes that can be very efficient and profitable at a small scale that wouldn’t work for market growers.

Mostly, though, we share a focus on making our efforts profitable. That makes professional-level strategies an excellent study while practicing our survival gardens.

Follow The Prepper Journal on Facebook!

The post Market Garden Strategies for Survival Gardens appeared first on The Prepper Journal.

Source

Market Garden Strategies for Survival Gardens

0 notes

Text

Thoosa

Quick Facts: Height: 5’5-6’2 Weight: 130-250 pounds Lifespan: 50-70 years Defining Features: Delicate Features Population: 3,000 Found: Theodmer, Crimea Reputation: Horselords Gods: None specifically Racial Bonus: +10 Riding Overview: The Thoosa are a subset of the human race. After the disbanding of all humanity at the beginning of time, the Thoosa traversed the land, before settling in the plains. There, they created a new society for themselves, which was based off of agriculture, warfare, and the breeding of fine horses. Some of the horses were bred for their strength, others for their beauty, ability to withstand the horrors of war, or speed. Over the course of several generations, the Thoosa have become masters of their art, earning them the name of the world’s horselords. History: The Thoosa were once grouped with all of the world’s races, until the division, at which point they moved away from the old lands in search of new ones. After having traveled the world for well over a decade, the earliest of their kind finally happened upon a stretch of plains, which they felt would suit their needs. From that point onward, they began to build the city of Theodmer, slowly crafting it into the realm we know of today. At the same time, they developed further into their own subset of the human race. At first, the Thoosa built their society around agricultural pursuits. They tilled the earth, and created miles upon miles of farmland. They raised various crops, such as carrots and corn, and used these crops to feed themselves, and live pleasantly enough for several generations. But as time wore on, they were discovered by monstrous invaders, and attacked time and time again. Wild animals too, ravaged their lands, partaking of their crops, and feasting on their young. Soon, tiring of their troubles, the Thoosa began to build a wall around their farms and small cottages. Despite their best efforts, the Thoosa were still harrowed by the world around them, and progress with their wall proved slow. Being that they had no quarries nearby, from which to gather stone, or forests nearby from which to gather wood, they were forced to trade with other friendlier peoples, if not travel great lengths in order to obtain the materials they needed to build their great wall. In so doing, they created even more enemies, as they moved onto the lands of their rivals, and took of their resources without asking permission. The Thoosa’s actions spurred the beginning of the Great Goblin War, in which the Thoosa’s lands, were attacked by a large goblin tribe, who were displeased with the loss of their trees. The war proved long and bloody, but eventually, the Thoosa prevailed, and were able to complete their wall with the trees, which rested on the lands, which had once belonged to the goblins. For a time, their society lived in relative peace; but, after awhile, their population became so great, that they realized that it had become necessary to expand their empire. So they built a large, rectangular building at the heart of their empire. To this day, they continue to refer to it as the hold. It was soon after, that the Thoosa gave their city its name, and decided that they could no longer survive as farmers, who lived alongside one another. So, they elected a king amongst the wisest of their kind. The king’s descendants have been ruling over the land ever since. With each generation, the kings and queens of Theodmer have not only expanded their holdings; but, led to a new development within Thoosan culture. Amongst the first of their kind was a king named Elidyr, who determined that their modes of transportation, preparing the earth to be planted, and harvesting crops, were not as efficient as they could or should be. He decided that it would be best to start domesticating wild horses, so a few were captured, and kept in the stables that the Thoosa had designed to be their homes. Elidyr’s son continued to carry out the process of bringing his father’s vision to light. He allowed the now domesticated horses to continue breeding, to build up their numbers to the point where just about everyone in the city had access to one. His grandson, Hatar, however, decided that this wasn’t enough, and began to urge his people to breed their horses for specific traits- speed, a certain colored coat, etc. Over a number of years, and multiple generations, the Thoosa mastered the ability to selectively breed, as well as to breed horses in general. Their presence permeates through every aspect of their daily lives, as they often serve as mounts, farming assistants, and companions. It is for this reason that the Thoosa have become known as the horselords, to which they take great pride. Biology: Physical Appearance: For the most part, the Thoosa look no different from garden-variety humans. However, it is believed that the “fresh plain” air, coupling with their more agricultural lifestyle, has led them to develop greater heights, stronger muscles, and greater weights. Most of the Thoosa fall somewhere between five feet and five inches tall, and six feet, two inches tall. Most male Thoosa are taller than the females, and most are more muscular. As a result, they tend to weigh more than female Thoosa. The average for a full grown Thoosa is somewhere between 130 and 250 pounds. Despite their forms having a greater presence than the average human, the Thoosa tend to have more delicate features, which gives them a somewhat childlike quality. This trait is far more pronounced in their female population, than the male population, and becomes apparent when one considers the shape of a Thoosa’s nose, the lightness of their lips and smile, the paler tones evident within their skin, the prevalence of freckles upon various portions of their body, and the lightness of their eyes. Most Thoosa have fair skin, which tends to burn fairly easily in the light of the sun. Their eyes tend to be large and almond-shaped. Most often, they come in shades of green or blue; but, smatterings of brown are not unheard of. Their hair tends to be kept long and flowing- in both males and females. In most cases, it is blonde or a bright orangey-red. However, lighter brown tones are not unheard of either. Common Traits: The Thoosa tend to have a lot in common with one another. They tend to have pale skin, lighter eyes, as well as lighter hair. Their skin is also, typically, dotted with a multitude of freckles in any number of areas. The vast majority of Thoosa also have a great fondness for horses, as well as horseback riding. Psychology: The Thoosa are both protective of their own, and fiercely loyal to one another, especially their families and their clans. If one of their kind is wronged, it is not uncommon for a large group to rally behind them, in order to right that wrong. They place a strong emphasis on both friend and family connections as well; while always providing their elders with the level of deference, which they are due. They value physical strength, which they feel contributes to getting things done, as well as hard workers, as they set a brisk pace by which to accomplish things. They also appreciate those who have become knowledgeable in their arts, (i.e. horse breeding), as they understand that it is from these individuals, that their culture is likely to be passed down, so that it might continue to survive through the ages. Reproduction: The Thoosa are capable of breeding with most of the world’s denizens. Each time they breed outside of their own race; however, their physical traits become diluted within their offspring. The gestation period for a Thoosa is nine months, as with any other human. Aging & Longevity: The Thoosa age at the same rate as would any other humans, and tend to live as long as most other humans. Society: Social Structure: The Thoosa have a more traditional culture, which is based around agriculture, and the breeding of livestock and other domestic animals, (especially horses). They are led by a king and queen, as well as the rest of the royal family. Those who may be considered second in power to them are military officials; but, they need only be followed by their underlings, and the rest of society in instances of military emergency, (i.e. when the city is under siege). However, it might always be said that those younger than others, are expected to obey the orders of their elders. This idea, that one should always respect their elder’s authority, is taught to the Thoosa from a young age, so that problems are beaten out of them early, and do not present themselves later in life. Language: The Thoosa never developed a language of their own. Instead, they speak Common, alongside the majority of the world’s races. Names: The majority of Thoosa are known by their first name, as well as their clan name in more formal settings. Their clan name isn’t used in most daily interactions, and is used to represent all of the individuals who live on a particular plot of land, or farm. For the most part, the clan name doesn’t serve much of a purpose, save that it identifies where within the land a person is from, as most families have lived upon the same plots for hundreds of years. In most cases, the surname serves as a shorthand, for identifications within the political sector, when two feuding parties go before the king in order to have a dispute settled. In other cases, it may be used by angry parents to address their children, when they really want their orders to be obeyed. Examples of Thoosa Names: Remmy Gladstone Hazel Ogden Caroline Wither Friends and Family: Thoosa tend to maintain close ties with both friends and family. This is due to the fact that the Thoosa are a highly interdependent race, who need each other for their survival. Being that every member of their society is a necessary member, the Thoosa go to great lengths in order to maintain harmony, and stomp out all discord. This is usually accomplished through a child’s rearing, in which the Thoosa are conditioned to believe that those with more years under their belt are more knowledgeable. As a result, these individuals should be the ones that are listened to, and obeyed without question. No distinction is made between the power of a woman and the power of a man; instead, they are both seen as equals within the eyes of the Thoosa, and whichever is oldest, will always be obeyed first. The only exceptions to this rule are that the king and royal family must always be obeyed before all else, and one’s commanding officer must always be obeyed. Should he fall during battle, the next highest ranking official should be obeyed, and is automatically promoted to his lost brethren’s position. Being that the Thoosa are a highly interdependent race, most children spend the majority of their day with their parents, learning how to take on the adult roles, which they will eventually pass on to their own children. Girls often spend time with their mothers, learning how to cook, clean, farm, and tend to the animals. After they have mastered these tasks, girls are taught how to ride horses, how to fight, and how to hunt. Boys on the other hand, often spend the majority of their time with their fathers. First, they are taught how to ride horses, and to care for their mounts. They are then taught how to mend their equipment, how to perform the “tougher” tasks involved in farming, how to fight, and how to hunt. (Note: This is a typical pattern within Thoosan society; but, not everything works this way). Being that as a whole, the Thoosa are a friendlier race, they tend to have no trouble making and maintaining friendships with those within their own race, as well as those outside of it. Being that various elvish settlements exist in locations not far from their own city; the Thoosa tend to make most of their outside connections with them. This, in turn, makes it easier for the two groups to facilitate trade with one another, as they have members on both sides to vouch for one another. Daily Routines: The daily routine for the vast majority of Thoosa living within the city of Theodmer consists of either one core activity or some combination of three things- tending to the horses, tending to the fields and raising crops, or training to defend the city, if one is not currently preoccupied with active participation within the city’s defense. Tending to the horses involves making sure that they are fed, making sure that they have enough water, making sure that they are given exercise, (this is usually done by taking them out hunting for extra food, or taking them out for long runs), making sure the horses are in good health, and are clean. Tending to the fields and raising crops involves tilling the earth, and preparing it for the sowing of seeds, watering the fields, and harvesting whatever may be harvested. It is grueling work. Naturally, tending to the city’s defense involves monitoring the wall, patrolling the area outside the wall by going on scouting expeditions, and training oneself to withstand onslaught. This is typically done through a mixture of body building and weapon training. Thoosa living outside of the city of Theodmer; however, may live very different lives. While they still may have a love and reverence for horses, they may not farm, or spend most of their time training for combat, if not fighting. Instead, their lives may go in any number of directions, as they adopt the lifestyles and traits of the people they are living amongst, and the “energy” of the city they are living in. Religion: The Thoosa do not pray to any one god or goddess in particular. Instead, they pray to whomever they feel fits in most with their lifestyle. The farmers may pray to Alana, as they appreciate how her children take care of vermin. Others may pray to Reyna, as they know that all good things are supported by her good earth. Many of the warriors choose to pray to Riviena, in order to keep them safe during battle. Others still, pray to Calone, in the hopes of bringing in better harvests. Others choose to pray to Feeyar, and L’vrai, in order to keep them safe during their travels, and all of their interactions with foreigners, fair. Diet: The Thoosa are an omnivorous race. The majority of their food comes from whatever is grown on their farms, or whatever livestock they raise. Therefore, they tend to eat a lot of beets, turnips, carrots, potatoes, and lettuce. They also eat a fair amount of chicken as well as pork, which they like to roast and season with various herbs. Most do not eat horse, even after the death of one they have bred. This is because it is considered to be both taboo and dishonorable to do so. Care: As a subset of the human race, the Thoosa may be cared for in the way that all humans are. The same kinds of ailments may also befall them.

#thoosa#theodmer#ariael#horselords#race#humans#fantasy rpg#fantasy#writing#omnivore#horses#rider#horseback riding

0 notes