#giovanni salviati

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

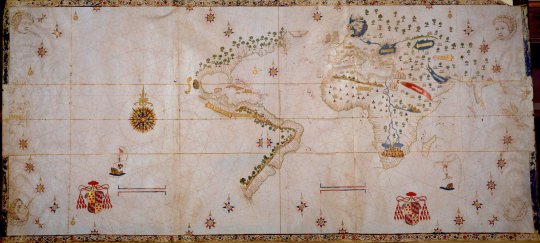

Planisferio de Salviati. Nuño García de Toreno, 1525

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whatever you do, don’t think about Lorenzo and Clarice’s eldest child Lucrezia and her eldest child Giovanni (their first grandchild) dying within a month of each other, at the ages of 83 and 63 respectively

1 note

·

View note

Text

Relevant to the Pazzi Conspiracy art that was going around yesterday. Marsilio Ficino to Francesco Salviati, one of the conspirators.

This was written sometime in October/November 1474, after Salviati’s election to the archbishopric of Pisa, and four years before the whole fuckaroo.

Love that apparently Marsilio and Giovanni sat around being super chuffed about Salviati’s ascension. (Ficino casting around for more patronage, because Lorenzo de’ Medici was lukewarm at this point, aside.)

Also love Marsilio and his prophesy moments.

#Marsilio Ficino#Francesco Salviati#pazzi plot#pazzi conspiracy#Giovanni cavalcanti#Marsilio blogging#Renaissance Florence#Renaissance Italy#15th century

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecchino del Salviati St Bartholomew 1550 Fresco Oratorio di San Giovanni Decollato, Rome

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

7 for your de riva?

codex prompts: someone describing a time your OC hurt them

Excerpt from the interrogation of Luisa Salviati, suspect in the murder of glass magnate Giovanni Salviati, her husband

Never get too close to the help. That's the conventional wisdom, especially when the help is good-looking, and recently hired, and - well, you know - elven. But no one really thinks it could happen to them, not normal people. We’re just not that important. We’re not political. Gianni certainly wasn’t any merchant prince. Of course I feel silly for not seeing it sooner, but it’s the sort of thing you’d make a joke about, isn’t it? You’d see a handsome new face serving tea at your cousin’s villa and tease her, "Watch out for that one. He’s probably a Crow."

They weren’t like a Crow, though. Not like you’d think. They weren’t even a very good servant. They’d forget things, mix up orders, laugh at conversations they should’ve been pretending not to hear. Maybe that’s what made them so disarming. Everything feels so like a performance these days, and here was this funny little extra wandering onstage and flubbing their lines. They felt so - real. Being with them made me feel more real. That’s the real joke, I suppose.

Because they had to be a professional. No notary ever signed off on those changes to the will, so they must have cracked the safe to switch in the forgery. Only a hardened killer could’ve stabbed the letter opener Gianni gave me so deeply into his poor heart that it snapped and left a bit of the blade behind. And I don’t know how they could've escaped with the doors and windows locked from the inside, but I was the one to send for the guard, for Maker's sake. Were I trying to pin the crime on some phantom assassin, do you really think I'd be so foolish as to not even open a damned window?

Investigator’s note: Other staff at the villa confirmed the recent employment of an elf matching the description given by Signora Salviati. Those close to this person reported that they'd left two days prior to the murder for a better-paying job near Antiva City. Several added that they had begun seeking new employment almost immediately after their hiring, as they found the inappropriate affections shown them by the lady of the house uncomfortable to refuse. When asked if this servant could’ve been capable of killing Signore Salviati, all, to a man, laughed aloud.

#auri de riva#my ocs#my writing#datv#dragon age#auri reading the paper a week later: i shouldve opened a window#ive been thinking about what the vibe must be like in antiva#even pre-datv crows seem to have been a source of national pride#but even assuming the majority of their contracts are outside antiva#i'd imagine antivans are still disproportionally assassinated#is everyone upper middle class and wealthier living in a state of normalized paranoia or is it like a face-eating leopards situation

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of Medici Women at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of Medici women from 1386 to 1691 CE; 38 women in total.

Piccarda Bueria, wife of Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Giovanni in 1386 CE

Contessina de’ Bardi, wife of Cosimo de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Cosimo in 1415 CE

Lucrezia Tornabuoni, wife of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Piero in 1444 CE

Bianca de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 14 when she married Guglielmo de’ Pazzi in 1459 CE

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Bernardo Rucellai in 1461 CE

Clarice Orsini, wife of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Lorenzo in 1469 CE

Caterina Sforza, wife of Giovanni de' Medici il Popolano: age 10 when she married Girolamo Riario in 1473 CE

Semiramide Appiano, wife of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici: age 18 when she married Lorenzo in 1482 C

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Jacopo Salviati in 1488 CE

Alfonsina Orsini, wife of Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Piero in 1488 CE

Maddalena de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Franceschetto Cybo in 1488 CE

Contessina de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Piero Ridolfi in 1494 CE

Clarice de’ Medici, daughter of Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici: age 19 when she married Filippo Strozzi the Younger in 1508 CE

Filberta of Savoy, wife of Giuliano de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Giuliano in 1515 CE

Madeleine de La Tour d’Auvergne, wife of Lorenzo II de’ Medici: age 20 when she married Lorenzo in 1518 CE

Catherine de’ Medici, daughter of Lorenzo II de’ Medici: age 14 when she married Henry II of France in 1533 CE

Margaret of Parma, wife of Alessandro de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Alessandro in 1536 CE

Eleanor of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Cosimo in 1539 CE

Giulia de’ Medici, daughter of Alessandro de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Francesco Cantelmo in 1550 CE

Isabella de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Paolo Giordano I Orsini in 1558 CE

Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 13 when she married Alfonso II d’Este in 1558 CE

Bianca Cappello, wife of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 15 when she married Pietro Bonaventuri in 1563 CE

Joanna of Austria, wife of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Francesco in 1565 CE

Camilla Martelli, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Cosimo in 1570 CE

Eleanor de’ Medici, daughter of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 17 when she married Vincenzo I Gonzaga in 1584 CE

Virginia de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Cesare d’Este in 1586 CE

Christina of Lorraine, wife of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Ferdinando in 1589 CE

Marie de’ Medici, daughter of Francesco I de’ Medici: age 25 when she married Henry IV of France in 1600 CE

Maria Maddalena of Austria, wife of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 19 when she married Cosimo in 1608 CE

Caterina de’ Medici, daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Ferdinando Gonzago in 1617 CE

Claudia de’ Medici, daughter of Ferdinando I de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Federico Ubaldo della Rovere in 1620 CE

Margherita de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Odoardo Farnese in 1628 CE

Vittoria della Rovere, wife of Ferdinando II de’ Medici: age 12 when she married Ferdinando in 1634 CE

Anna de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo II de’ Medici: age 30 when she married Ferdinand Charles of Austria in 1646 CE

Marguerite Louise d’Orleans, wife of Cosimo III de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Cosimo in 1661 CE

Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, wife of Ferdinando de’ Medici: age 16 when she married Ferdinando in 1689 CE

Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenberg, wife of Gian Gastone de’ Medici: age 18 when she married Philipp Wilhelm of Neuberg in 1690 CE

Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, daughter of Cosimo III de’ Medici: age 24 when she married Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine in 1691 CE

The average age at first marriage among these women was 17 years old.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist

Artist: Bacchiacca (Italian, 1494 - 1557)

Genre: Religious Art

Francesco d'Ubertino Verdi, called Bachiacca. He is also known as Francesco Ubertini, il Bacchiacca. He was an Italian painter of the Renaissance whose work is characteristic of the Florentine Mannerist style.

Bachiacca was born and baptized in Florence on 1 March 1494 and died there on 5 October 1557

Bachiacca belonged to a family of at least five, and possibly as many as eight artists. His father Ubertino di Bartolomeo (ca. 1446/7-1505) was a goldsmith, his older brother Bartolomeo d'Ubertino Verdi (aka Baccio 1484-c.1526/9) was a painter, and his younger brother Antonio d'Ubertino Verdi (1499–1572)—who also called himself Bachiacca—was both an embroiderer and painter. Francesco's son Carlo di Francesco Verdi (-1569) painted and Antonio's son Bartolomeo d'Antonio Verdi (aka Baccino -1600) worked as an embroiderer. This latter generation probably continued to produce paintings and embroideries after Bachiacca's death and until the Verdi family extinguished about the year 1600.

Bachiacca apprenticed in Perugino's Florentine studio, and by 1515 began to collaborate with Andrea del Sarto, Jacopo Pontormo and Francesco Granacci on the decoration of cassone (chest), spalliera (wainscot), and other painted furnishings for the bedroom of Pierfrancesco Borgherini and Margherita Acciauoli. In 1523, he again participated with Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio and Pontormo in the decoration of the antechamber of Giovanni Benintendi. While he established a reputation as a painter of predellas and small cabinet pictures, he eventually expanded his output to include large altarpieces, such as the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, now in Berlin.

In 1540, Bachiacca became an artist at the court of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici (reg. 1537-1574) and Duchess Eleanor of Toledo. In this capacity, Bachiacca was a colleague and peer of the most important Florentine artists of the age, including Pontormo, Bronzino, Francesco Salviati, Tribolo, Benvenuto Cellini, Baccio Bandinelli, and his in-law, the sculptor Giovanni Battista del Tasso.

Bachiacca's first major commission was to paint the walls and ceiling of the duke's private study with plants, animals and a landscape, which remain an important testimony of Cosimo's interest in botany and the natural sciences.

#bacchiacca#italian artist#religious art#holy family#christ child#john the baptist#joseph#mary#christianity

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

JACOPO BASSANO (Bassano del Grappa alrededor de 1515 – 1592)

Virgen, el Niño y San Giovanni

alrededor de 1541

Pintura al óleo sobre lienzo

Inventario Contini Bonacossi no. 18

Esta Virgen, que se puede fechar hacia 1541, está relacionada con una xilografía de Francesco Salviati que representa los Matrimonios Místicos de Santa Catalina dentro de la Vida de Catalina de Pietro Aretino (1540) conservada en la Biblioteca Nacional Central de Florencia. Las figuras afiladas y afiladas inspiradas en el ejemplo de Salviati caracterizan las formas de Jacopo en la década de 1540.

Información de la Gallerie degli Uffizi, fotografía de mi autoría.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

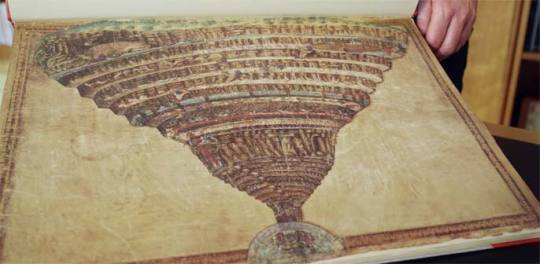

Le lapidi di Firenze: seconda parte

Inferno di Botticelli LAPIDI DANTESCHE Nelle strade del centro di Firenze, si trovano sui muri di palazzi, chiese e case torri delle lapidi dantesche. Vi si leggono incise frasi relative alle tre cantiche della Divina Commedia: Inferno, Purgatorio e Paradiso. Ai primi del Novecento, il Comune di Firenze sentì il desiderio di rintracciare i personaggi e i luoghi descritti nella sua opera. Iniziò una accurata ricerca per trovare il luogo esatto dove apporre le lapidi. La ricerca fu lunga e accurata. Finalmente nel 1907 iniziò l’apposizione nei siti rintracciati: INFERNO - Filippo Argenti, via del Corso dove erano le case degli Adimari; - Guido Cavalcanti, via Calzaioli dove erano le case dei Cavalcanti; - Ponte Vecchio (loggia di Ponte Vecchio), in sul passo d’Arno; - Brunetto Latini, via dei Cerretani (tra il civico 39 rosso e la chiesa di S. Maria Maggiore; - Famiglia Gianfigliazzi, via de’ Tornabuoni (sopra la vetrina del civico 1 rosso); - Dedicata al Battistero di San Giovanni, Piazza San Giovanni (all’esterno del Battistero verso la via Martelli; - Dedicata alla nascita di Dante Alighieri, posta sulla sua casa; - Bocca degli Abati, il traditore di Montaperti, via dei Tavolini. PURGATORIO Citazione di persone del suo tempo, 2^ cantica. Sono descritti la Basilica di San Miniato al Monte e il ponte Rubaconte, via di San Salvatore al Monte (inizio della scalinata che porta al Piazzale Michelangelo; Piazza Piave (nella torre della Zecca Vecchia), dedicata al fiume Arno; Versi dedicati a Forese Donati, via del Corso (sopra ai civici 13 – 33 rosso); Piazza di San Salvi, dedica a Corso Donati (nel punto dove sostò l’esercito di Arrigo VII; Dedica alla donna angelicata Beatrice Portinari, (sulla destra dell’ingresso del palazzo Portinari – Salviati). PARADISO Elenco delle lapidi tratte dalla 3^ cantica. Dedicati alla città natale del poeta, Via Dante Alighieri alla Badia Fiorentina (sul fianco sinistro della Badia Fiorentina e alla sinistra del civico 1); Dedicati a Bellincione Berti Ravignani, via del Corso (sopra le vetrine del negozio civici 1 e 3 rosso); In questi versi sono ricordati gli antenati del poeta, via degli Speziali (tra la vetrina del civico 11 rosso e il portone del civico 3); Dedicato alla famiglia Cerchi, via del Corso (sopra le arcate del negozio ai civici 4 rosso e 6 rosso); Dedicata alla famiglia dei Galigai, via dei Tavolini (torre dei Galigai vicino al civico 1 rosso); Sulla famiglia degli Uberti, Piazza della Signoria (nel primo cortile di Palazzo Vecchio); Sulla famiglia Lamberti, via di Lamberti (tra le finestre sopra il civico 18 rosso e 20 rosso); Dedicato ai Visdomini, via delle Oche (presso ciò che resta della Torre dei Visdomini, tra i civici 20 r0s e 18 rosso); Famiglia Adimari, via delle Oche, (tra gli archi delle vetrine ai civici 35 rosso 37 rosso); Famiglia Peruzzi col loro simbolo (le sei pere), Borgo dei Greci (a sinistra della porta al civico 29); Famiglia della Bella, via dei Cerchi (all'angolo di via dei Tavolini); Dedicati a Ugo il Grande, via del Proconsolo (sulla facciata della chiesa Santa Maria Assunta); Famiglia Amidei, via Por Santa Maria (presso la torre degli Amidei, sopra al civico 11 rosso); Dedicati a Buondelmonte Buondelmonti, via Borgo Santi Apostoli (Presso le case dei Buondelmonti, sopra le vetrine dinanzi al civico 6); Dedicati alla statua di Marte, causa degli scontri fra Guelfi e ghibellini, distrutta dall’alluvione del 1333. Ubicata dove si trovava la statua, Ponte Vecchio (angolo Piazza del Pesce); Dedicati alla Firenze antica, Piazza della Signoria (nel primo cortile di Palazzo Vecchio); Dedicati al battesimo, Piazza San Giovanni (nel Battistero verso il Duomo); Preghiera dedicata alla Vergine da San Bernardo, Piazza del Duomo.

Alberto Chiarugi Read the full article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una lettera di Giovanni dalle Bande Nere dall'assedio di Pavia

Una lettera di Giovanni dalle Bande Nere dall’assedio di Pavia – Eugenio Larosa Nella tumultuosa Italia del Rinascimento, una lettera giunge dai campi di battaglia che circondano Pavia. È il 10 febbraio 1525, e Giovanni de’ Medici, celebre condottiero e destinato a divenire figura leggendaria, scrive al cognato, il Cardinale Giovanni Salviati, che si trova a Piacenza. Composta durante l’assedio…

0 notes

Text

12 giugno 1519: nasce Cosimo I de’ Medici, il primo granduca di Firenze

Il 12 giugno del 1519 venne al mondo Cosimo, l’unico figliolo di Giovanni de’ Medici detto dalle Bande Nere e di Maria Salviati, nipote di Lorenzo il Magnifico. Il padrino di battesimo fu niente meno che papa Leone X e proprio lui propose il nome di Cosimo per il nuovo nato, in onore a detta sua del più savio, prudente e valoroso uomo della casata. Nel 1537, con i favore di Carlo V, il Senato…

View On WordPress

#accaddde oggi#antonietta bandelloni#art#arte#considerazioni#english#Firenze#Michelangelo Buonarroti

0 notes

Text

Italie : Venise. Palazzo Grimani di Santa Maria Formosa, musée d'état dans le quartier de Castello, près de Santa Maria Formosa.

Situé près de Campo Santa Maria Formosa dans le quartier de Castello, le Palazzo Grimani a ouvert ses portes en tant que musée public en 2008. Le bâtiment remonte à l'origine au Moyen Âge et avait une structure en forme de L. À la fin du XVe siècle, il fut acheté par Antonio Grimani, un marchand prospère qui devint Doge de Venise en 1521. Dès lors, le Palazzo Grimani fut la demeure de l'une des plus importantes familles vénitiennes jusqu'au milieu du XIXe siècle. Ses deux petits-fils, Giovanni - qui fut évêque de Ceneda et plus tard patriarche d'Aquilée, et Vettore - magistrat en chef de San Marco, en firent leur résidence en 1532. Ils remodelèrent et redécorèrent le palais en 1539-40, commandant les travaux à Francesco Salviati et Giovanni d'Udine. Les thèmes de l'Antiquité reflétés dans les stucs et les fresques exprimaient les préférences classiques de la famille.

***

Italy: Venice. Palazzo Grimani di Santa Maria Formosa, state museum in the Castello district, near Santa Maria Formosa.

Located near Campo Santa Maria Formosa in the Castello district, Palazzo Grimani opened its doors as a public museum in 2008. The building originally dates back to the Middle Ages and had an L-shaped structure. At the end of the fifteenth century it was purchased by Antonio Grimani, a successful merchant who became Doge of Venice in 1521. From then on, Palazzo Grimani was the home of one of the most important Venetian families until the mid-19th century. His two grandsons, Giovanni - who was Bishop of Ceneda and later Patriarch of Aquileia, and Vettore - chief magistrate of San Marco, made it their residence in 1532. They remodeled and redecorated the palazzo in 1539-40, commissioning the work to Francesco Salviati and Giovanni da Udine. Themes of antiquity reflected in the stuccowork and frescoes expressed the family's classic preferences.

Somewhere in Italy ☺️

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend: In the book in praise of Philosophy, which I wrote this year for Bernardo Bembo, the Venetian ambassador, I tried with many arguments to show that Philosophy teaches all things. I ought to have made the one exception, that she does not teach us how to live with princes. For if she forbids this altogether, as indeed she does, she cannot teach us how. She altogether forbids it, it seems to be, since she commands the opposite; for in discovering the love of truth she surely requires a tranquil mind and a free life. However, truth does not dwell in the company of princes; only lies, spiteful criticism and fawning flattery, men pretending to be what they are not and pretending not to be what they are.

[emphasis mine]

Ficino out here just being utterly scathing in his fury and heartbreak about politicians being Like That.

This is basically a two-and-a-half page long screed about princes and their many, many faults - particularly focusing on princes who throw their former tutors under the bus.

It is worth considering those great philosophers whose memory we cherish who would have been far more successful than others in living with princes and kings if only Philosophy were able to teach men that [temperance, prudence etc.]. I shall not describe how the young Octavian, being ungrateful to the services of his friend, the distinguished philosopher Cicero, handed him over for no good reason to his unscrupulous enemies for execution. Nero condemned to death without cause his own teacher, the venerable philosopher Seneca. Alexander, king of Macedon, is said to have thrown his own teacher, the philosopher Callisthenes, to the lions, simply because he was often torn to shreds in argument.

Ficino goes on. The original ending of the letter to Giovanni is:

But allow me to return now to philosophers to conclude my discourse. Let no one be so ignorant of man's capacity as to believe that he can play the part of philosopher fitly and freely, and at the same time live with safety and serenity in the company of princes.

Like woooo boy was Marsilio on a RAMPAGE that day. Just tearing it up on the page. Telling, too, that he writes this letter to Giovanni and evidently trusts him enough to do it.** Sure, it was likely written in 1476, two years before the Pazzi conspiracy, but a) people keep letters and b) even in '76 it would have landed him in hot water.

[** this is me vague-ing an essay I read the other day where the author was like "yeah, it was one sided pathetic, desperate love on Ficino's side. nothing more." my dude, Marsilio was out here writing letters to Giovanni that could have got him hanging from a window next to Jacopo Bracciolini, Salviati and Francesco Pazzi. Pretty sure there was some mutual love and trust happening. I cannot over emphasize how careful Ficino was in his writing, especially his correspondence. Anyway.]

An interesting note is that after the Pazzi Plot occurred, the ending Marsilio included that is basically like: obviously the Medici are different, they're "something greater and more sacred [than princes]. For their singular virtues and great merit deserve more than any human title. They are father of their country in a free state."

That ending was removed because no one knew if the Medici were going to survive the political upheaval. It was likely scratched out by Salvini, Ficino's nephew/cousin(?) and secretary. I would say that the little "But Not the Medici" was likely a caveat on Ficino's part in case the letter escaped from Giovanni's hands. Ficino was smart like that. He did care for Lorenzo, no doubt, if in a complicated fashion. But that doesn't mean he was unaware or blind to Lorenzo's faults.

Ficino seemed to have not been in Florence when the Pazzi conspiracy went down, which was good for him given that he was partially implicated in it. Sort of. (As in, he was close friends with most of the main players and one of them was his major patron since Lorenzo was being stingy as-fuck with the money.)

(Lorenzo eventually cleared suspicion from Ficino - though they were always a bit cool after that. Not that I think they were ever very warm towards each other. But my thoughts on Ficino and Lorenzo's relationship are for another post. Basically, even if Ficino didn't know what was up for the conspiracy, he certainly knew, or guessed, enough to send strongly worded letters to literally everyone involved telling them to cool their fucking heels and not do stupid things in the pursuit of power/glory/worldliness etc. Also, convenient that he wasn't in the city... I just feel like someone gave him a tip-off...)

All of this is aside, basically I'm certain Ficino's original letter was 100% a massive fucking bitch-fest about Lorenzo not being a good patron to Ficino on multiple levels - all those references to princes who unjustly condemned their tutors when Ficino was one of Lorenzo's early tutors? He wasn't being subtle. And god help us, Ficino can be subtle as fuck when he wants to be.

Interestingly, Ficino includes a para' on poets getting the bad end of the stick from princes (Ovid, Lucan, Statius) which I think is him not necessarily warning Giovanni (who was a poet), since in 1476 there was no cause for worry over anything, but certainly alluding to poets who suffered when princes went foul. "It's not just me who needs to worry about mercurial nature of princes but you as well, babe."

anyway, not going anywhere particular with this nor am I likely saying anything that hasn't been said before about the letter, but just having some brain worms, as usual.

#marsilio ficino#giovanni cavalcanti#marsilio blogging#renaissance italy#pazzi conspiracy#early modern italy#renaissance florence#history#15th century#1478 - rough year#ficino never wanted the Medici removed from power#He just had a complicated and mercurial relationship with Lorenzo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Medici: Portraits and Politics, 1512–1570 | The Met Curatorial Conversation

#portraiture#sculpture#benvenuto cellini#giuliano da sangallo#francesco salviati#bronzino#giovanni delle bande nere#eleanor of toledo#cosimo i de' medici#pierino da vinci#giambologna

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nuovo post su https://is.gd/9yPRdn

Vuoi pubblicare? Basta pagare! Parola di Giovanni Domenico Salviati, simpatico letterato leccese del XVII secolo e di Pietro Micheli, suo editore altrettanto simpatico, entrambi amanti del vino, almeno sulla carta ...

di Armando Polito

Incisione di Geronimo Cock del 1556 (per comprendere il suo inserimento bisogna arrivare alla fine) tratta da https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:002293875

Uno dei fenomeni più diffusi del nostro tempo è la proliferazione dei concorsi letterari, farsesca imitazione degli storici Premio Strega e Premio Campiello. Facendo leva sul narcisismo di quel terzo della popolazione italiana appartenente in via del tutto autopresunta alla categoria dei poeti (le altre, com’è noto sono quella dei santi e quella dei navigatori, ma come la prima, non sono a tenuta stagna, nel senso che a seconda della convenienza chiunque può ascriversi a ciascuna di esse, anche se ignora l’esatta sequenza delle lettere dell’alfabeto o cos’è la bussola o ha già ammazzato quattro suoi simili), si stimola la partecipazione dei concorrenti, il cui numero sarà, grazie alla quota d’iscrizione, direttamente proporzionale al guadagno finale degli organizzatori. L’editoria in genere, però sembra aver messo da parte l’ingrediente fondamentale di qualsiasi attività imprenditoriale, cioè il rischio, adagiandosi nel comodo letto di sponsorizzazioni private e pubbliche (penso soprattutto ai quotidiani), trascurando il parametro del talento e del merito ed assecondando il gusto dominante di una caterva di lettori superficiali e suggestionabili. Così è difficile che essa scopra e promuova (pardon, produca …) personalità che entreranno a far parte della storia, anche minore o, addirittura, locale della letteratura e sarà sempre costretta a costringere gli autori a darsi da fare per il lancio della loro creazione in una serie di presentazioni, dalla più visibile (in tv) alla meno (qualche pro loco). Nemmeno sotto tortura”editori” ed “autori” confesserebbero questo stato di cose che dal punto di vista valoriale presenta molti, se non solo, lati deboli e su domanda farebbero intendere l’esistenza di un rapporto di reciproca stima. Stavano così le cose pure in tempi in cui il libro, fosse anche il più leggero, era un prodotto riservato a pochi (oggi, magari, per non sentirsi fuori, molti lo acquistano, pochissimi lo leggono …), oggi diremmo di nicchia, perché la pubblicazione comportava costi elevati non esistendo i mezzi messi a disposizione dalla moderna tecnologia (basta pensare alle tavole che prima di arrivare alla stampa dovevano fare i conti con la penna del disegnatore e poi col rame dell’incisore), per cui non era neppure immaginabile l’abbassamento del prezzo che di regola l’economia di scala comporta? Chi ha dimestichezza con libri datati avrà notato che è immancabile una dedica, in alcuni casi chilometrica, a personaggi politicamente (ed anche allora il gemellaggio tra questo avverbio ed economicamente era quasi automatico) di rilievo, del quale padrone colendissimo il dedicatore si dichiarava umilissimo ed obbligatissimo servo osservantissimo (vada per il resto ma le due ultime due parole costituiscono una ridicola tautologia). E tutto nella speranza che il potente di turno, riconoscente per la dedica, gli concedesse qualche incarico o beneficio. Non si sottrae certamente a questa regola antica (in fondo anche a Roma i letterati dell’entourage di Mecenate erano mossi solo dall’amor patrio o dalla stima per il detentore di turno del potere) il letterato leccese il cui nome ho anticipato nel titolo.

La dedica, infatti, inizia con Al Sig.e Padron mio osservandissimo e termina con Di V. S. M. Illustre Servitore Affettionatissimo.

Sull’autore delle Rime non sono riuscito a reperire alcuna notizia e nemmeno la dedica contiene dati utili, consente solo di rilevare una certa familiarità col dedicatario: … havendo in diverse occasioni composto diversi Sonetti, parte Serii, parte Burleschi trattovi dalla natural mia vena, havendoli più volte letti ad Amici, et a V. S., essendone stato sollecitato da quelli, e comandatomi da lei, che dovesse stamparli, non hò potuto recusare. Si arguisce che si tratta di persona di un certo rilievo, come il dedicatario, del quale riproduce lo stemma e ricorda la provenienza genovese negli ultimi due versi del primo sonetto: MECENATE GENTILE (alta ventura)/venisti a Noi dal Ligure Parnaso). In mancanza di altri riscontri credo di poter avanzare come pura ipotesi di lavoro, in attesa di altri eventuali più proficui riscontri, l’identificazione con Giovanni Domenico Salviati, notaio sulla piazza di Lecce dal 1615 al 1635, il cui nome compare anche tra quelli delle persone designate ad essere aggiunte al collegio di amministrazione dell’Ospedale dello Spirito Santo di Lecce per l’amministrazione dell’eredità di Cesare Prato1.

Se la dedica rientra nella normalità, ciò che mi ha colpito del volume, a parte il sonetto iniziale di cui ho detto ed il successivo dedicato al figlio Giorgio del dedicatario, è la presenza subito dopo, quindi in una posizione ancora sufficientemente privilegiata in rapporto alla lettura, la presenza di quattro sonetti che costituiscono una sorta di simpaticissimo intermezzo tra l’autore e l’editore. Li riporto in formato immagine con, di mio, la trascrizione e le note di commento.

__________

a Nato a Dôle, in Borgogna, nel 1600, Pietro Micheli, dopo un apprendistato tipografico a Roma e a Trani e una prima società costituita a Bari, nel 1631 fu il primo stampatore a Lecce. morì nel 1689.

b attira, spinge, induce

c Non riesco a capire la funzione delle parentesi.

d rinunziare a stamparle

e raffinato rigore formale

f Plozio Tucca e Lucio Vario Rufo erano due poeti del circolo di Mecenate; a loro Augusto diede l’incarico di pubblicare l’Eneide di Virgilio rimasta priva di revisione per la morte dell’autore. Qui Vario è diventato Varo per esigenze di rima.

g Giovanni Della Casa (1503-1556), autore, fra l’altro, di ll Galateo overo de’ costumi.

h Annibal Caro, (1507-1556), famoso per la traduzione in endecasillabi sciolti dell’Eneide di Virgilio.

i Ludovico Castelvetro (1503 circa-1571), famoso per una polemica con Annibal Caro innescata da un giudizio negativo espresso da Castelvetro su una canzone del Caro, intitolata Venite all’ombra de’ gran gigli d’oro, e motivato dal mancato stile e linguaggio petrarchesco e dai contenuti deludenti. La situazione si complicò quando Alberico Longo di Nardò (su di lui vedi:

https://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2015/02/11/una-nota-su-alberico-longo-di-nardo/

https://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2019/11/21/alberico-longo-di-nardo-alle-prese-col-petrarca/

https://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2019/11/08/nardo-alberico-longo-e-la-sua-inedita-doppiamente-versione-di-un-mito/

https://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2019/10/06/nardo-alberico-longo-e-ursula/)

fu assassinato e il Castelvetro venne indicato dall’entourage del Caro come uno deimandanti. Lo stesso Caro nonsi lasciò sfuggire l’occasione per accusare di Eresia il Castelvetro, che nel 1560 fu condannato dall’Inquisizione subendo la confisca dei beni.

_________

a andate

b non mi rimproverate

c sistemato al suo posto

d la punta dello stilo

e Pseudonimo di Leonardo Salviati (1540-1589), la cui fama è legata alla fondazione dell’Accademia della Crusca, che si costituì ufficialmente nel 1585. Impossibile dire se il leccese ne fosse parente, caso in cui ci sarebbe da ravvisare quasi una sfumatura di autoironia.

f abituata a scrivere testi di protesta (lo stile, perciò è immediato)

g dettaglio difettoso

La risposta dell’editore non si fece attendere.

________

a punte

b saccente

Ecco la replica del leccese.

L’ultima parola, però, fu dell’editore.

_________

a bevute smodate nella quantità e nel numero

b ispirazione

c Divinità romane delle acque e e delle sorgenti; in epoca tarda furono identificate con le Muse, protettrici dlle arti.

d Fonte sacra alle Muse fatta sgorgare sul monte Elicona dal cavallo Pegaso con un colpo di zampa. Ma quella era una fonte di acqua, quella cui il salentino, per contrasto, sta per alludere è di vino.

e bevute; il verbo sgozzare è usato al participio passato sostantivato partendo dal significato tutto originale di riempirsi la gola fino a far comparire una specie di gozzo.

f La comprensione di questi quattro versi richiede la lettura del documento 1 riportato in appendice.

g Cavallino, alimentato dalla fonte Ipopocrene (vedi la nota d)

h Poeta greco del VI-V secolo a. C.

i Orazio, poeta latino del I secolo a. C., nativo di Venosa.

l è necessario chwe lo guidi Bacco

m abitudine; il verso è stranamente mancante della prima parte (quattro sillabe).

APPENDICE

Arcipoeta è il soprannome di Camillo Querno (circa 1470-1530). Riporto integralmente e traduco il paragrafo che alle pp. 51-52 gli dedicò lo storico Paolo Giovio nel suo Elogia veris clarorum virorum imaginibus apposita quae in Musaeo Ioviano Comi spectantur, Tramezino, Venezia, 1546:

CAMILLUS QUERNUS ARCHIPOETA.

Camillus Quernus e Monopoli , Leonis fama excitus, quum non dubiis unquam praemiis, Poetas in honore esse didicisset in Urbem venit, Lyram secum afferens, ad quam suae Alexhiados supra vigintimillia versuum decantaret. Arrisere ei statim Academiae sodales, quod Appulo praepingui vultu alacer, et prolixe comatus, omnino dignus festa laurea videretur. Itaque solenni exceptum epulo in insula Tyberis Aesculapio dicata,potantemque saepe ingenti patera, et totius ingenii opes, pulsata Lyra proferentem, novo serti genere coronarunt; id erat ex pampino, Brassica, et Lauro eleganmter intextum, sic, ut tam false , quam lepide, eius temulentia, Brassicae remedio cohibenda notaretur; et ipse publico consensu Archipoetae cognomen, manantibus prae gaudio Lacrymis laetus acciperet, salutareturque itidem cum plausu, hoc repetito saepe carmine:

Salve Brassica virens corona,

et lauro ARCHIPOETA pampinoque

dignus Principis auribus Leonis.

Nec multo post tanto cognomine percelebris productus ad Leonem infinita carmina in torrentis morem, rotundo ore decantavit; fuitque diu inter instrumenta eruditae voluptatis longe gratissimus, quum coenante Leone, porrectis de manu semesis obsoniis, stans in fenestra vesceretur, et de principis lagena perpotando, subitaria carmina factitaret; ea demum lege, ut praescripto argumento bina saltem carmina ad mensam, tributi nomine solverentur, et in poenam sterili vel inepto longe dilutissime foret perbibendum. Ab hac autem opulenta, hylarique sagina, vehementem incidit in podagram; sic, ut bellissime ad risum evenerit, quum de se canere iussu in hunc exametrum erupisset:

Archipoeta facit versus pro mille poetis

et demum haesitaret, inexpectatus Princeps hoc pentametro perargute responderit:

Et pro mille aliis Archipoeta bibit.

Tum vero astantibus obortus est risus: et demum multo maximus, quum Quernus stupens et interritus, hoc tertium non inepte carmen induxisset:

Porrige, quod faciat mihi carmina docta Falernum.

Idque Leo repente mutuatus a Virgilio subdiderit:

Hoc etiam enervat debilitatque pedes.

Mortuo autem Leone, profligatisque Poetis, Neapolim rediit; ibque demum, quum gallica arma perstreperent,et uti ipse in miseriis perurbane dicebat pro uno benigno Leone, in multos feros Lupos incidisset. Oppressus utraque praedurae egestatis, et insanabilis morbi miseria in publica hospitali domo, vitae finem invenit; quum indignatus fortunae acerbitatem, prae dolore, ventrem sibi, ac intima viscere forfice perfoderit.

CAMILLO QUERNO ARCIPOETA.

Camillo Querno da Monopoli, allettato dalla fama di Leone [papa Leone X], avendo saputo che i poeti con premi mai dubbi erano tenuti in onore, venne a Roma portando con sé la lira per cantare al suo suono gli oltre ventimila versi della sua Alessiade [di questo come si altri suoi poemi nulla è rimasto]. Piacque subito ai soci dell’Accademia, poiché allegro nel suo grassoccio volto apulo e capelluto sembrava assolutamente degno di una festosa laurea. E così, dopo averlo accolto in un solenne banchetto sull’isola tiberina dedicata ad Esculapio e mentre beveva spesso da una grande tazza e al suono della lira esprimeva le risorse di tutto l’ingegno, lo incoronarono di un nuovo tipo di corona. Essa era fatta di pampini, cavolo e alloro elegantemente intrecciata sicché tanto sul serio che spiritosamente si sottolineasse la sua ubriachezza e col pubblico consenso ricevesse lieto tra le lacrime di gioia il soprannome di Arcipoeta e similmente fosse salutato con un applauso, ripetuto più volte questo canto:

Salve, tu che verdeggi di una corona di di cavolo e di alloro e di pampini, degno ARCIPOETA alle orecchie del principe Leone.

Né molto dopo, celebre per tanto soprannome, portato al cospetto di Leone, recitò con la rotonda bocca infiniti carmi a mo’ di torrente; e fu per lungo tempo graditissimo tra le risorse di erudito piacere quando, mentre Leone pranzava e con la mano gli allungava rimasugli di bocconi, lui li mangiava appoggiato a una finestra e bevendo a lungo dal fiasco del principe dava vita a canti improvvisati, con la legge che almeno due canti fossero intonati a mensa su un argomento prescritto, con la pena che per un esito insufficiente o inadatto avrebbe dovuto bere vino annacquatissimo. A causa di questa ricca ed allegra alimentazione incorse in una severa podagra, sicché amenamente suscitò il riso quando, invitato a cantare di sé, se ne uscì con questo esametro:

L’Arcipoeta fa versi al posto di mille poeti

e mentre esitava il principe senza che nessuno se l’aspettasse gli rispose argutamente con questo pentametro:

E l’Arcipoeta beve al posto di mille altri

Allora sì che il riso sorse tra gli astanti e ancora maggiore quando Querno sbigottito ma intrepido proferì non a casaccio questo terzo verso:

Offrimi del Falerno, perché io componga dotti carmi

e Leone all’istante presolo a prestito da Virgilioa gli servì:

Anche questo snerva e debilita i piedi [qui il papa gioca sul doppio senso che in latino ha il piede, che, oltre al dettagli anatomico, indica anche un elemento fondamentale della metrica].

Morto poi Leone e allontanati i poeti, ritornò a Napoli. Qui infine, quando le armi dei Francesi facevano sentire il loro strepito ed egli, molto civilmente nel disagio diceva, invece di un benigno Leone si era imbattuto in molti feroci lupi. oppresso da ogni lato dal durissimo bisogno e dal tormento di un’insanabile malattia finì i suoi giorni in un pubblico ospizio, quando, indignato con la crudeltà della sorte, per il dolore con una forbice si trafisse il ventre e le viscere.

____

a Da un epigramma facente parte delle opere giovanili attribuite a Virgilio (Appendix Vergiliana). Ecco i primi 4 versi: Nec tu Veneris, nec tu Vini capiaris amore,/namque modo Vina, Venusque nocent./Ut Venus enervat vires, sic copia Vini/et tentat gressus, debilitatque pedes (Non farti prendere dall’amore di Venere né da quello del vino; infatti allo steesso modo sono nocivi i vini e Venere. Come Venere snerva le forze, così l’eccesso di vino mette alla prova i passi e indebolisce i piedi). Ad esso si ispira pure la tavola di testa.

_________________

1 Congregazione di Carità di Lecce O. P., Ospedale dello Spirito Santo, Actus aperturae testamenti inscriptis conditi per quondam D. Cesarem Prato, 22/06/1635-III, c. 1, b. 2, fasc. 18.

#Armando Polito#Camillo Querno#Geronimo Cock#Giovanni Domenico Salviati#Paolo Giovio#Pietro Micheli#Arte e Artisti di Terra d'Otranto#Libri Di Puglia#Spigolature Salentine

0 notes

Photo

And yet Heaven’s providential intervention stepped in; since the still free mind of Prince Don Cesare couldn’t grasp a greater gift was yet to come. And this bird-catcher fooled by hope, instead of an escaped dove, managed to catch a Phoenyx. This was indeed Donna Luisa di Luna e Vega, daughter of Pietro Duke of Bivona, who by marrying Don Cesare, not only brought to her husband’s House her father’s Duchy, and the lands of the House of Peralta, already englobed by those of de Luna’s, but then with the marriages of her son and grandson, poured in the Moncada’s possessions, the titles and riches of two other illustrious lineages, that of Aragona and Cardona, with the Duchy of Montalto and the County of Collesano.

Hence, like that Arabian bird, which it is obsequiously followed by other birds wherever it flies, likewise she brought with her a magnificent procession of many estates in the House where she nested.

Giovanni Agostino della Lengueglia, Ritratti della prosapia et heroi Moncadi nella Sicilia: opera historica-encomiastica, p.559-560 [my translation]

Aloisia (or Luisa) was born in Bivona (nearby Agrigento) around 1553. She was the firstborn of Pietro Giulio de Luna Salviati, Duke of Bivona, Earl of Caltabellotta and of Sclafani, and his first wife, the Spanish Doña Isabel de Vega y Osório. The baby girl was named after her paternal grandmother, Luisa Salviati de' Medici. In fact, through her father, Aloisia descended from Lorenzo il Magnifico de' Medici, who was her great-great-grandfather. On her mother’s side, on the other hand, she was the granddaughter of Juan de Vega y Enriquez, who had been Viceroy of Navarre and later of Sicily (also the one who brought Jesuits in Sicily). Aloisia had two younger sisters, Bianca and Eleonora, and a half-brother, Giovanni, born in 1563, out of Pietro's second marriage to Ángela de la Cerda y Manuel, daughter of Juan de la Cerda, IV Duke of Medinaceli and Viceroy of Sicily from 1557 to 1564.

In 1568, Aloisia married Cesare Moncada Pignatelli, Prince of Paternò, Earl of Adernò and of Caltanissetta, a decade older than her, in Caltabellotta. The union between the two had been planned by Juan de la Cerda, the bride's step-grandfather. Cesare was indeed supposed to marry his cousin, Giovanna de Marinis (daughter of his aunt Stefania), but marriages between noble families were delicate matters and needed the Viceroy's approval as well as (sometimes) the Papal dispensation in case of seventh grade parentage. The Moncadas were an incredibly wealthy and noble family. They owed their fortune mainly to Guglielmo Raimondo Moncada Earl of Agosta who, in 1379, had kidnapped Queen Maria I of Sicily and brought her to Spain where she married her cousin Martino. To thank him for his support, King Pedro IV of Aragon (the Queen’s maternal grandfather) had named Guglielmo Raimondo Royal Counselor and Justiciar of the Kingdom of Sicily. From 1565, the Moncadas were able to add to their titles that of Princes of Paternò, plus managed to exchange Augusta for Caltanissetta, thus saving tons of money since Augusta, differently from Caltanissetta, was a maritime city, which was often the victim of pirates’ raidings and needed to be constantly defenced (which entailed great expenses). De la Cerda used his influence to mess up the Moncadas’ original wedding plans (angering thus the groom’s family) and proposed the union with the de Luna, with whom the Moncadas were distantly related and therefore had needed the Pope’s blessing.

Aloisia would give birth to two children: Isabella (who would die an infant) and Francesco (ca. 1569-1592). Her marital life would be cut short as Cesare would suddenly die in Paternò on July 30th 1571, after only three years of marriage.

Little Francesco, now Francesco II, would be officially appointed of his late father’s titles the following year and placed under the guardianship of his maternal grandfather, Pietro de Luna, and his paternal uncle, Fabrizio Moncada (first husband of famous portrait painter Sofonisba Anguissola). Seven years later, Fabrizio would die in a pirate attack off the coast near Capri and some would talk about it not being an accident and about rumours of Fabrizio being headed to Spain to denounce his sister-in-law’s meddlings in the management of the Moncada’s patrimony.

Gossipers aside, it’s documented Aloisia took personal care in the education of her son and short-lived daughter. She began Francesco to study law, philosophy, literature and maths, as well as more artistic subjects like painting and sculpting.

Aloisia was the one who actively ruled over her son’s lands, showing a great deal of resourcefulness and managerial skills. Holding steady in her mind the idea of strengthening her (and by result her son’s) position, on September 17th, 1577, in Monreale, she married Antonio d’Aragona Cardona, Duke of Montalto and himself a widower. By concession of the Viceroy Marcantonio II Colonna, Aloisia obtained to keep acting as her son’s guardian without having to cede the role to her new husband or someone else.

Antonio d’Aragona too belonged to a prominent family, being a grandson of Ferrante d’Aragona Guardato, founder of the Line of the Dukes of Montalto and illegitimate child of Ferdinando I of Naples. Antonio’s first wife had been María de la Cerda y Manuel de Portugal, daughter of Juan de la Cerda y Silva, 4th Duke of Medinaceli as well as a Grandee of Spain, Viceroy of Sicily and Viceroy of Navarre during his long political career. From his first marriage, only his daughter Maria had reached adulthood as little Ferdinando died as an infant.

Aloisia bore Antonio a daughter, Bianca Antonia, who would later marry Giuseppe Ventimiglia Ventimiglia, II Prince of Castelbuono and IX Marquis of Geraci, and be the mother of Francesco III Ventimiglia d’Aragona, who would be offered (but not accept) the Crown of the Kingdom of Sicily during the anti-Spanish revolt of 1647.

The Duke of Montalto died in Naples on February 8th, 1584, on the route to quell a riot in the Flanders (the so called Dutch War of Independence) by virtue of his role of Captain General of the Spanish Cavalry in the Flanders. Leaving no male heir, all his titles and possessions passed to his eldest daughter, Maria.

Aloisia didn’t lose time to grieve for her husband as she swiftly arranged the marriage between her son Francesco and her step-daughter, the new Duchess of Montalto. The wedding took place on March 12th 1585 and the following year Francesco received maritali nomine the endowment of the Duchy of Montalto the Earldom of Collesano and all the lands owned by his wife’s family, bringing the total to thirteen of the fiefs owned by the Moncada.

On August 1592, Aloisia’s half-brother, Giovanni died childless, so as his eldest sister and heir, on September 30th she was endowed of the baronies of Scillato and Regaleali. She also inherited many fiefs in the area of Caltavuturo and Sclafani. From her court in Caltanissetta, she kept cleverly administering her possessions as well as the lands acquired through both of her late husbands (she generally rented her lands to foreigners, mostly Genoese and Pisans). She invited the Jesuits in Caltanissetta, had many churches and religious centre of the area built, she restored the city’s Cathedral. Aloisia took particular interest in having the Moncada’s libri di famiglia (books used to register one family’s commercial activity as well as key events in the lives of its family members, particularly common from XIII to XVI century) perfectly catalogued and maintained. She introduced and commissioned many artists and was perhaps the one who called back her sister-in-law Sofonisba Anguissola who, at that time, lived in Genova with her second husband, and who starting 1615 returned in Sicily where she would die.

Those who visited her, were rendered almost speechless about the magnificence of her court. During a visit in 1598 of the Viceroy and Vicereine, Bernardino de Cárdenas y Portugal and his wife Luisa Manrique de Lara, the Duchess had, in that occasion, surpassed herself. Aloisia had, in fact, arranged the area where she would receive her guests (at her own expenses), the forest of Mimiani, so perfectly and with so many tents, one would have thought you were in an actual city. Her guests were so pleased, the Vicereine gifted her of a splint of the Holy Cross kept in a display case ornated by precious stones.

Aloisia was also particularly generous. She did a lot of charity (and passed on the same generous disposition to her son and grandson), but made it through the nuns, ordering them to keep quiet about her being the one who sent the money, so that people would rather thank the Heaven for the celestial gift. She must have thought that public displays of charity didn’t have as an aim to help people, but rather that some benefactors did it for themselves since they took pleasure to hear their names be acclaimed for their generosity. During a terrible famine, when poor people were so hungry they ate grass and pasture, she used her personal income to provide for her people, so that at that time in her lands mortality rate was very low. She was also particularly mindful to guarantee that poor girls wouldn’t find themselves forced by misery to undertake a dishonourable life, granting them means to do honourable marriages. On the other hand, the Duchess didn’t skirt from regularly sending generous gifts to ministers and potentates, so that when at the right time, she could count on their support.

On May 23rd, 1592, a 23 year-old Francesco II Moncada died of malaria in Adernò (nearby Catania). Although it must have been extremely heartbreaking to lose her beloved son, Aloisia braced herself and took on the task of properly raising, together with her daughter-in-law, her 4 years-old grandson, Antonio. Since the child was also Donna Maria’s heir, in accordance with his parents’ marriage settlements, it had been stipulated he would take as first his mother’s surname and be styled as Antonio II d’Aragona Moncada de Luna.

The little Prince grew up together with his younger brother Cesare (the other brother, Giovanni, had died a child) in his family’s palace in Caltanissetta, closely watched over by their grandmother and mother (although, at ten, he seriously risked drowning in a cistern, while playing with his brother, and was saved thanks to Cesare’s cries for help which alerted Aloisia and Maria). From a young age, Antonio had been betrothed to Juana de la Cerda y de la Cueva, daughter of Juan de la Cerda, VI Duke of Medinaceli and his first wife Ana de la Cueva and at that time her father’s only heir.

The Duke of Medinaceli was in particular eager to have this marriage celebrated and already thought of Antonio as a son of his own. Since the young Moncada kept delaying his journey to Spain in order to marry, the Duke of Medinaceli somewhat grew tired and got married a second time (although he hadn’t thought of remarrying previously). Unfortunately for Juana, her step-mother, Antonia de Toledo Dávila y Colonna, would in 1607 give birth to a son, Antonio Juan Luis, who would surpass his sister and would one day inherit their father’s titles and possessions.

Although, understandably, organising a quasi-royal marriage all the way to Spain, complete with a long voyage to reach it, was indeed a big and long deal, that missed chance was perhaps Aloisia’s only mistake. If only they had moved faster, and Juana had succeeded her father, Moncada’s riches might have reached legendary status.

The delay was due to the fact that the old Duchess had also insisted to travel to Spain, accompanied by her daughter-in-law, Maria, and her two young granddaughters, Isabella and Luisa, with the hope of finding suitable matches for the girls among the Spanish aristocracy, and for that every aspect of the journey had to be perfect (Isabella would die young, while Louisa would marry in 1612 Eugenio de Padilla Manrique, III Count of Gadea). The Moncadas had to arrive in Spain with the pomp and grandeur (Aloisia must have thought) they deserved. Worryngly, as they reached Naples and stopped for a break, the groom grew sick and had to be treated by the best doctors before he could resume the voyage.

The marriage between Antonio Moncada and Juana de la Cerda took place in 1607 and it seems like it was a successful union, with the couple living harmoniously together in Spain for the first years, then settling in Collesano, near Palermo and part of Antonio’s possessions. While in Spain, the new Duchess gave birth to a son, Francesco, in 1613, who would be followed by Sicilian born Luigi Guglielmo (1614), Marianna (1616), and Ignazio (1619).

In 1610, Maria d’Aragona de la Cerda, Dowager Princess of Paternò died, leaving her mother-in-law Aloisia as the sole matriarch of the family.

In 1626, the young Francesco, Antonio II’s heir, would feel ill and die (and his siblings almost followed him) while both of his parents were in Spain to attend their courtly duties. Full of pain and regrets, Antonio and Juana would obtain the dissolution of their marriage and they both would take the cloth, becoming one a Jesuit and the other an Augustinian nun. Following his father’s resignation, 13 years-old Luigi Guglielmo became the new Prince and head of the Moncada family.

But Donna Aloisia would be spared of these sorrows as she died in Palermo in 1620, at 67. She would be buried in her Caltanissetta, in the Church of Santa Maria Assunta, which would be turned into a hospital in the XIX century, and which already housed the grave of her son Francesco II.

Sources

Antognelli Enrica, LUISA MONCADA Una Grande Donna del Rinascimento Siciliano

De la Cerda. Duques de Medinaceli

della Lengueglia Giovanni Agostino, Ritratti della prosapia et heroi Moncadi nella Sicilia: opera historica-encomiastica, p.557- 672

Le foto che raccontano il passato di Bivona

Palumbo Valeria, La Sicilia celebra la potentissima Aloisia de Luna Vega

Silva Alfonso Franco, EL DUCADO DE MONTALTO - NOTAS SOBRE LOS SEÑORIOS ITALIANOS DE MEDINA SIDONIA

Storia e Arte

#women#history#historicwomendaily#historical women#women in history#aloisia de luna vega#House of Moncada#House De Luna#caltanissetta#province of caltanissetta#aragonese-spanish sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit#Francesco II Moncada de Luna#Antonio II d'Aragona Moncada

21 notes

·

View notes