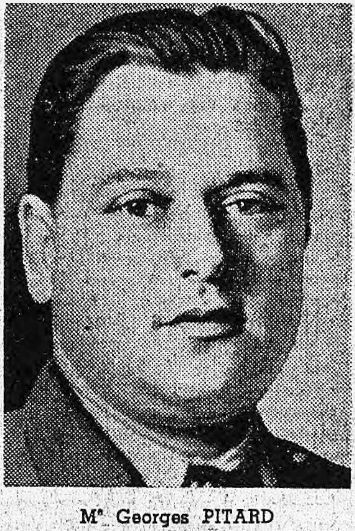

#georges pitard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Georges Pitard

Type : Lieu de travail

Adresse : 18 rue Séguier, 75006 Paris, France

Date de pose : 12 novembre 1944 [source]

Texte : Ici était le cabinet de Georges Pitard, avocat à la Cour de Paris, membre du Parti communiste français et du Conseil juridique de l'Union des syndicats de la Seine, qui a été fusillé par les nazis dans le premier groupe d'otages le 20 septembre 1941 en exaltant le devoir, la vérité et la justice

Quelques précisions : Georges Pitard (1897-1941) est un avocat et militant communiste français. Diplômé de droit, il rejoint le Parti communiste en parallèle de sa carrière d'avocat, où il se fait remarquer pour son engagement syndicaliste. Après sa démobilisation au début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il poursuit sa carrière d'avocat en défendant d'autres syndicalistes et militants communistes. Arrêté en juin 1941 par le régime de Vichy, il est fusillé par les Allemands quelques mois plus tard, fier de sa carrière au service de la justice.

#individuel#hommes#travail#avocats#syndicalistes#seconde guerre mondiale#resistance#france#ile de france#paris#datee#georges pitard

0 notes

Note

Do you have any articles or sources you’d recommend for reading about the Ugarit sea monster Tunnanu? I know it’s mostly mentioned in the Ba’al cycle and possibly one incantation for snake bites (though that translation is contested), but it’s also so often conflated with Lotan ;7;)

There isn’t much to know beyond what you already know, as far as I can tell. It seems you are pretty well versed in the topic. As far as I know most of the recent translations of the incantations do accept that Tunnanu is mentioned in it though, if we’re talking about KTU 1.82.

More about Tunnanu, and about its purported Akkadian cognate, under the cut.

Some recent treatments of the aforementioned text and/or other passages mentioning Tunnanu include ust How Many Monsters Did Anat Fight ( KTU 1.3 III 38–47)? by Wayne T. Pitard, A Study of the Serpent Incantation KTU2 1.82: 1–7 and its Contributions to Ugaritic Mythology and Religion by Adam E. Miglio and Yamm as the Personification of Chaos? A Linguistic and Literary Argument for a Case of Mistaken Identity by Brendan C. Benz. Sadly, none of them address whether Tunnanu can be firmly separated from Lotan. With the exception of Pitard, most do agree that the convention of treating this name as a title of Yam is erroneous though.

It seems part of the problem is that there’s an ongoing debate over whether there is a singular monster named Tunnanu or if tunnanu is a generic term for a mythical serpentine creature. Pierre Bordreuil’s and Dennis Pardee’s A Manual of Ugaritic recommends the later interpretation, for instance. Pitard and Mark S. Smith in the second volume of the Baal Cycle commentary argue that it is not impossible tnn is in reality two words, not one. Their argument rests on the fact that the vocalized tu-un-na-nu from the multilingual lexical list is a synonym of ordinary words referring to snakes in Sumerian (MUŠ) and Akkadian (ṣi-i-ru). On this basis, they tentatively suggest the monstrous tnn from the Baal Cycle and incantations might have had a different reading.

The only other matter I think worth addressing here is the argument over the purported Akkadian cognate of Tunnanu. The presence of cognates of the name in multiple other languages is obviously widely agreed upon. Most notably, tannin (and plural tannînîm) occurs in the Old Testament as a sea monster and/or a regular snake. While other variant forms and cognates are attested in a variety of sources in Aramaic, Arabic and Ge’ez, they seem to reflect late adoption depending on the aforementioned source, as outlined by George C. Heider in the DDD.

Where does the notion of an Akkadian cognate come from, then, since it wouldn’t exactly fit this pattern? In 1998, Frans Wiggermann published his influential article Transtgridian Snake Gods (funnily enough in the same volume as Westenholz equally, if not more impactful Nanaya, Lady of Mystery). He convincingly argues there that some of Mesopotamian deities tied to the underworld can be grouped together based on their serpentine associations, an idea adopted by many subsequent studies (most recently by Irene Sibbing-Plantholt in The Image of Mesopotamian Divine Healers, I believe).

In a footnote (p. 35), he argues that an association with snakes or outright a snake-like form can be attributed to the elusive Dannina, a deity listed in the god list An = Anum among the courtiers of Ereshkigal (tablet V, line 234). He depends on the assumption this name would be an Akkadian cognate of Tunnanu, in addition to being a variant form of the term danninu, one of the many sparsely attested poetic designations of the underworld.

However, as summarized by Anna Jordanova in her dissertation Untersuchungen zur Gestalt einer Unterweltsgöttin: Ereškigal nach den sumerischen und akkadischen Quellentexten notes that while the precise etymology of danninu remains uncertain, most other researchers did not accept Wiggermann’s interpretation. On one hand, tunnanu lacks any connection to the underworld. On the other hand, danninu and thus Dannina have another more plausible etymology. The word danānu, “to be strong”, is well attested, and would make it possible to translate danninu something like “the strong place”, “the stronghold”, a name perfectly in line with the image of the underworld as a fortified city evident in its descriptions in myths and in terms like urugal, “great city”, and the like. For what it’s worth, the only time I recall seeing danninu outside of god lists and formulas of the “heaven and earth/the underworld” variety was in a title of Nergal cited by Wayne Horowitz in Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography, āšir dannina sāniq nēr, “controller of the underworld, supervisor of the 600” (600 being the conventional number of deities believed to reside there in post-Kassite sources). Nergal obviously wasn’t associated with snakes, while the more commonly proposed meaning of the term does fit his general character. Therefore, I also think in this case Wiggermann is wrong.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: The Pitards by Georges Simenon (Trans by David Bellos)

Book Review: The Pitards by Georges Simenon (Trans by David Bellos)

Disappointing novel offers few glimpses of Simenon’s greatness.

Determined to retire his most famous creation Inspector Maigret, Simenon intended to focus on writing literary fiction. Simenon used the term ‘roman dur’ to refer to his portraits of deviance. Freed from the crime genre’s conventions he explored themes present in the Maigret novels without the restriction of having to include a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Pitards by Georges Simenon

The Pitards by Georges Simenon

Translated by David Bellos Reviewed by Annabel By 1934, Georges Simenon had published the first 19 Maigret books, and he temporarily shelved the series, resuming ten years later. He went travelling around the world but didn’t stop writing, trying out a different form. These standalone books would come to be known as his romans durs (hard novels), tending to be dark and serious psychological…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Drawing Galaxy #livredartiste #robertmarteau #poetry #poesie #david2no (à Rue Georges-Pitard)

0 notes