#geoffrey the lizard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

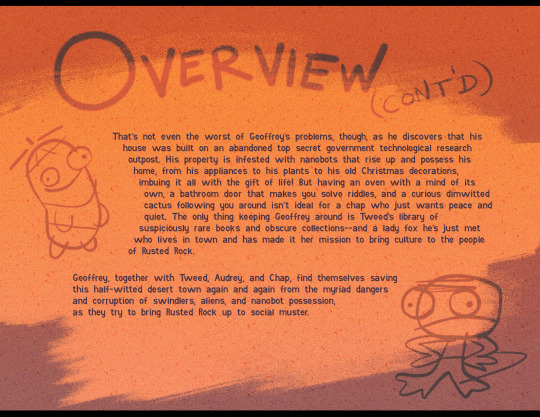

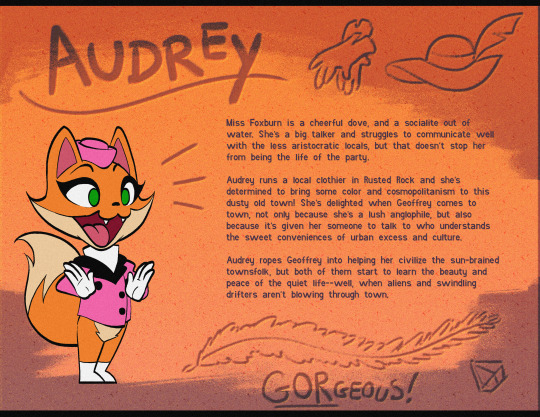

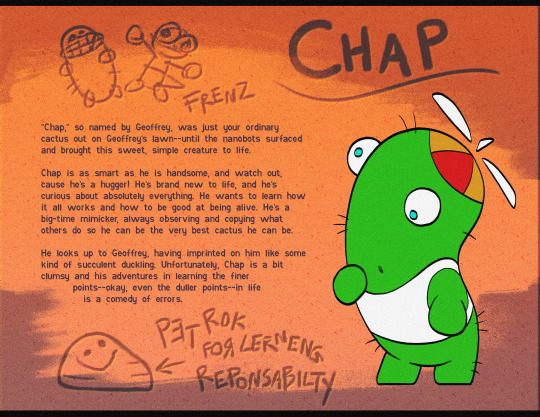

Before there was Mallory Bash, this was a cartoon series concept I'd been toying around with. I've been slowly reworking the art and story and building a pitch bible for it, but it's always been a throwback type of cartoon--back to classic 90's-style characters and story. It's coming along! It's about an English lizard who moves from London to a little backwater town in Arizona called Rusted Rock, but his escape turns out not so peaceful when he discovers that the town is plagued by corruption, scavengers, shady drifters, and even aliens! But that's not the half of it. Check out the pages below to find out how everything in Geoffrey's house comes to life. This is one I always thought would be a solid match for @nickanimation @nickelodeon There will be more edits, of course, but this is a pretty solid rough start. #intelligentlife #illustration #pitchbible #animation #animatedseries #characterdesign #storydevelopment #characterdevelopment #geoffrey #chap #audreyfoxburn #puddles #rustedrock #rustedrockarizona #seriesconcept

#intelligent life#pitch bible#illustration#animation#animated series#cartoon#character design#character development#story development#series concept#geoffrey the lizard#chap the cactus#audrey the fox#audrey foxburn#puddles the snowman#puddles#geoffrey#chap#piper the chevrotain#piper#rusted rock#rusted rock arizona#desert#david perry

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silly post concept: Cosplaying campaign NPCs in Elden Ring

Did this earlier in the day, wasn’t sure if I would devote a post to it, but I’m on a bus and would like to do something so behold this silly/scuffed idea.

When it comes to armour especially I already take a lot of reference/inspiration from fromsoft designs, so some of these come somewhat naturally and even include pieces that I used as reference originally. Anyways, enough babble, time for scuffed Elysia characters, or their lands-between doppelgängers.

The venerable knight Sir Geoffrey, with easily the most scuffed bit being the bug helmet lmao. The fact that a bug-shaped helmet even exists is what barely allows this recreation. The armour, on the other hand, the Scale Armour set, is actually what originally inspired Sir Geoffrey’s armour, crafted from the hide of a great lizard. Unfortunately the options for portly characters/armour in the game are limited and didn’t fit design-wise.

The one and only Mr. The Black Blade, Thalo. Actually surprised at how faithfully he can be made, and there were a few different options. When I originally designed Thalo, I used Malikeths armour set as reference, but only the gauntlets from that armour made it into this iteration, since the DLC added a couple new pieces that worked better. Main surprise is the helmet, sure it’s not the right shape but the fact it has horns in the right spot is enough.

Iosefka! Despite being based on a fromsoft character, Elden Ring doesn’t possess many similar options for that outfit, so I kinda winged the clothing. Decided to aim for her rogue attire, rather than the scrubs. The Misericordes appearance in the game is also why I was motivated to give it to her as her weapon of choice.

Last, not necessarily least, the totally trustworthy and not nefarious fellow, Lehran. Another not-totally-perfect fit, since I felt a serious lack of purple robes, at least none that were fitting in the slightest. Everything else though, pretty decent ngl. Also the only one who doesn’t get a weapon, as I didn’t arm Lehran in his only appearance thus far.

I tried to brainstorm and couldn’t think of many other NPCs that have appeared who I could readily cosplay, sort of limited to humanoids in full armour or somewhat elaborate robes.

Anyways, this was a fun lil goof, I’ll see if I come up with enough material for a sequel.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in 2024 (plus ratings)

江戸川 乱歩/ Edogawa Ranpo 孤島の鬼 (Kotō no Oni)/ The Demon of the Lonely Isle [trans. Alexis J. Brown] (10/10) Utterly unwell over this one. The last part makes me want to cry every time I think about it. The Black Lizard and Beast in the Shadows [trans. Ian Hughes](7/10) Fun reads! The first one is an Akechi Kogoro mystery iirc. The Phantom Doctor (7/10) Also Akechi-sensei and fun, but nowhere near as brain rewiring as Koto no Oni. Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination [trans. James B. Harris](7/10) A collection of some of Ranpo's works. Some were good, some were mid, and some were just Junji Ito levels of weird.

Shakespeare The Tempest (8/10) Fun, but coloniser mentality much. Did read it in conjunction with Jane Eyre, not actually reading Robinson Crusoe, and reminiscing over Wide Sargasso Sea, so that was actually very fun for the brain. Twelfth Night (Or, What You Will) (10/10) I need to direct a production of this play so badly. Or just let me be Cesario. As You Like It (7/10) Fun but not really my vibe.

The Martian by Andy Weir (9/10) Not usually a sci-fi girlie, but this was delightful to read.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle (8/10) Delightful, amazing, BBC Sherlock can actually take the Reinbach plunge for the gross mischaracterisation of Sherlock.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (7/10) Good, it's a classic for a reason. I would recommend reading Wide Sargasso Sea along with JE.

人間失格 (Ningen Shikkaku)/No Longer Human by 太宰 治/ Dazai Osamu [rather crusty pdf, I don't remember who the translator is] (8/10) Incredible. Reminded me of reading The Bell Jar. It did make me really sad tho, ngl, but there's also a sense of recognition.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon (10/10) Loved this!

镇魂 (Zhèn Hún)/ Guardian by Priest (6/10) Was not vibing with the main story. Miscommunication and just general ridiculousness imo. B-plot was fun and Changcheng is so baby and sweet. I love him. 3 of the 6 stars are for him, the rest are for the other characters excluding MC and not-actually-a-professor. 2 books

川口 俊和/ Toshikazu Kawaguchi [trans. Geoffrey Trousselot] さよならも言えないうちに/ Before We Say Goodbye 思い出が消えないうちに/ Before Your Memory Fades この嘘がばれないうちに/ Before the Coffee Gets Cold: Tales from the Cafe (7/10) for all. They were good, but not rent-free levels of good.

White Teeth by Zadie Smith (7/10) It was good.

墨香铜臭 (Mo Xiang Tong Xiu) [Trans: Seven Seas] 人渣反派自救系统 (Rén zhā fǎnpài zìjiù xìtǒng)/Scum Villain's Self-Saving System (9/10) So much about this one. I think about it at least once a week, probably. This was 4 books iirc 魔道祖师 (Módào Zǔshī)/ Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (8/10) Love the political intrigue. I will read this again at some point so that I can enjoy it while understanding what's happening. Everything can be explained by the answer "Jin Ling's uncle". Honestly, probably some of my favourite characters are in here. 5 books 天官赐福 (Tiān Guān Cì Fú)/ Heaven Official's Blessing (8/10) Yeah, filing and maths is difficult. Intriguing plot as well and as with MDZS, got stabbed in the heart several times. this is like 8 books long T^T

二哈和他的白猫师尊 (Erha He Ta De Bai Mao Shizun)/ The Husky and His White Cat Shizun by 肉包不吃肉 (Rou Bao Bu Chi Rou)/ Meatbun Doesn't Eat Meat [Trans: Seven Seas] (7/10) I was ready to give up, but the actual plot was interesting. and there's time travel. idk how many.. 3 or 4

女将军和长公主 (Nu Jiangjun he Zhang Gōngzhu)/Female General, Eldest Princess by 请君莫笑 (Please Don’t Laugh) [Trans: Melts and Eiko] (8/10) Plot is good. Stressed me tf out though ngl. Definite recommendation. Like watching shoujo after too much shounen. I think about this one frequently as well.

The Twelve Week Year by Brian P. Moran & Michael Lennington Idk how to rate this, but it's been helpful and I wanna try this method out this year.

Ghastly Tales from the Yotsuya Kaidan by Saitō Takashi (7/10) Wanted to kill a lot of people in this myself. That being said, the story is told nicely.

The Snows of Kilimajaro by Ernest Hemingway (7/10) Collection. Some were good, some were mid. His life was absolutely wild. Idk how Hemingway survived as long as he did tbh.

ダンジョン飯/ Dungeon Meshi by 九井諒子/Ryoko Kui (9/10) Loved this!! Suck you in with fun fantasy and then damn, the curtains are not just blue. 14 volumes

Depilautumn by Nakahara Chūya [trans. Kenneth L. Richard & John L. Riley] (8/10). Poetry Anthology, fun but not all were a vibe.

River of Stars by Yosano Akiko [trans. Sam Hamill & Keiko Matsui Gibson) (8/10) Delightful and Yosano was pretty damn amazing!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'We Have Become Death

We f’d up,” are the simple, clarifying words of Mo Gawdat — author of Scary Smart and former Chief Business Officer at Google X — on a recent episode of the podcast The Diary Of A CEO with Steven Bartlett.

He was referring to the release of ChatGPT and similar Generative A.I. systems, which have exploded as the latest in a series of global crises we’ve been faced with in the last several years. An urgent open letter has been written by leaders in the tech industry requesting a “six-month pause” on experiments and advancements as they assess potentially catastrophic consequences. The Center for Humane Technology is racing to governments with a desperate plea to “regulate before it’s too late.” (You can see their talk on A.I. and its various implications here.) Members of Congress are pushing for an A.I. bill. And, the “Godfather of A.I.,” Geoffrey Hinton, exited Google with dire warnings. Collectively, the community behind the creation and dissemination of this iteration of A.I. is having what Gawdat calls its “Oppenheimer moment.”

If they are having such an (in relevant terms) immediate mea culpa, then the question becomes: Why proceed without caution before the release of this species-altering technology? The answer, as it turns out, is very similar to what J. Robert Oppenheimer contended with in the 1940s, and what Gawdat describes as the first inevitable: “X advance (a weapon, a new technology, A.I.) will happen… ‘because of the other guy.’”

In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Hinton said, “I console myself with the normal excuse: If I hadn’t done it, somebody else would have.”

If I Don’t Do It, They Will

“The other guy” is a primary motivator for a host of human ills. For the most part, the people we know (personally) are human and flawed, but not psychopathic soul-sucking wormholes who seek the destruction of all they encounter. Yet, society at large often functions in a pathologically self-destructive manner. So there is some inherent disconnect between how we function in individual interactions, and the organizational and collective choices we make.

That break can be found in the avaricious, fear-based, survival impulse of the “other guy” ethos. “If I don’t do it, then they will.”

And, if that happens, I will lose: money, position, power, authority, and in the deepest recesses of our lizard brains, all resources and ability to survive.

It’s irrational, and makes us behave in ways that are counter to our long-term well-being. It reflects a deep distrust of our fellow man. It also indicates that we don’t have a lot of faith in our own ability to adapt and pivot with changing landscapes, while maintaining a focus on integrity and keeping things like generational well-being top of mind. Because sometimes the right thing to do in the face of a new technology is to go very slowly, or opt out entirely. The competitive, and fearful, instinct to rush ahead is also pathologically megalomaniacal, because, in this interpretation, the “I” is the only one worthy of holding real power.

In recent months, many of us have been pressured to implement tools like ChatGPT into our daily business activities: to test, learn, and master them as quickly as we can, always with the hope of gaining advantage over “the other guy” and with the baseline assumption that “if we don’t, they will.” But the reality is, in the long term (which few think of in the context of earnings reports), the other guy has just as much to lose as we do. But we’re scared, so we panic, and make moves that are too quick and with too little thought.

So what does any of this have to do with Oppenheimer or Barbie? Quite a lot as it turns out. Oppenheimer reflects the stagnant patterns of thinking that got us into this mess, Barbie is — both overtly and subtly — representing new ways to address problems, and a more collaborative leadership style that just may free us of the perils we, ourselves, have created.

Those warning against A.I. (largely leaders in the space) say that it is an extinction level risk as great, or greater than, nuclear weapons and/or global warming due to the staggering speed with which it is, can, and will evolve. (Yes, evolve, not advance.)

Why Oppenheimer? Why Now?

So shouldn’t we care about Oppenheimer’s story more than ever? Maybe. Maybe not. It depends on the interpretation — and director Christopher Nolan’s new film fails to embrace the moment. Oppenheimer (based on the book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin) follows Cillian Murphy as the titular character in his early academic life through his work on the Manhattan Project — leading the charge in the creation of the atomic bomb. This is set against some explorations of his personal life, connections with the American Communist Party, and, importantly, two government hearings. One, a hearing in 1954 to determine his security status, and the second, Lewis Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing for Secretary of Commerce in 1959.

One description of the film says it “thrusts audiences into the pulse-pounding paradox of the enigmatic man who must risk destroying the world in order to save it.”

That sentence is the essence of an alarming lack of personal responsibility on Oppenheimer’s part (a deficit that the film tacitly endorses). It also captures the rather heroic lens that is afforded the character. This isn’t a story about understanding how we allowed one of humankind’s greatest disasters to happen; it’s a film about the feelings (or lack thereof in interpersonal matters) of the man who ran the project to do so — half of which focuses on his hurt feelings after losing his security clearance years after said large-scale homicide of the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Oppenheimer’s security level forfeiture was primarily due to the paranoid and wounded feelings of a petty and small man: Strauss (played, admittedly, gorgeously by Robert Downey Jr.). Hours of screen time dedicated to a small-minded squabble in the telling of the choice to burn the world.

What should have been the essential focus of the story links to the excuse given for releasing and implementing Generative A.I. today: “the other guy” dynamic. Sadly, Nolan’s Oppenheimer isn’t so much interested in honing and questioning the validity of that reasoning, other than offering a brief mention of it. If anything, it leans into and plays up this dynamic sans investigation.

“We can’t let the Nazi’s make the bomb first.” That’s the entirety of the discussion regarding why they initiated the Manhattan Project.

What Oppenheimer Fails (Refuses) To See

A fair, and pretty hard to argue with, assertion… Yet, creating the weapon actually wouldn’t have necessarily prevented Germany from doing the same. So, what was the plan once both sides had it? Weren’t there other options? Like striking key research targets either via bombs or assassinations? How about kidnapping the scientists to our side?

These first few violent ideas aren’t necessarily advisable or viable. However, we might retroactively brainstorm the first bad ideas that come to my mind, because if we do that, eventually we’ll land on better ones. The point is we must not simply stop at “we have to” without doing the work of probing that premise thoroughly.

Because, ultimately, the Nazis lost before the completion of the Manhattan Project. However, as seen in Nolan’s Oppenheimer, Russia was able to make progress on an atomic weapon as a result of it — sending us into a Cold War and decades-long specter of mutually assured destruction. One which is still very much playing out on a global stage.

The U.S. was not wrong to do everything in its power to prevent the Nazis from gaining ground. At all. Nor was their motivation to “beat Germany to it” nearly as morally bankrupt as the “I’ll lose free-market competitive edge if I don’t release my potentially civilization-ending A.I. system before the other guys,” excuse that tech leaders used. What’s important to note is that the film breezes past the crucial question of “Why?” in favor of far less essential (and interesting) explorations.

The movie notes that the war was all but over by the time the weapon was actually, and sickeningly, deployed. However, again, it’s wishy-washy in its portrayal of accountability. It does little to question the U.S. having taken this action when they so clearly didn’t need to: choosing to rain fire on people who had nothing to do with the decisions that arrogant leaders made behind closed doors. Oppenheimer as a film is entirely non-committal about, nor seemingly deeply interested in, the essential parts of this story and what truly matters: personal responsibility in the face of global catastrophe.

Essentially, why we are the way we are and how we can be different.

It gives Oppenheimer an out by having him relay “both sides” of scientific opinion. Yet, he was in no way “neutral” in reality. Oppenheimer was in the rooms and a part of the discussions about which cities to target and did indeed have “blood on his hands.”

Again, the film fails to make much of this other than a cursory acknowledgement. In fact, we pointedly don’t ever see Japan or its citizens. Instead, we bear witness to a few heady sequences wherein Oppenheimer imagines destruction hitting his own home turf. Indeed, he chooses to look away from actual footage of the destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki — footage Nolan does not show the audience.

Okay, you don’t want to be exploitative, but you don’t have to be in order to acknowledge the lived experience of those who actually suffered.

Much of Oppenheimer is beautifully made, and it’s brimming with brilliant performances, centered by Murphy’s. But it’s laboriously — and unnecessarily — mired in flabby side-stories. Saliently are the issues of what it chooses to focus on.

It drags us through a story of a fight between Oppenheimer and those who would stymie his influence in Washington. Opposition that is centered largely on the respective egos of the players: Murphy’s Oppenheimer vs Downey Jr.’s Strauss. Essentially, Strauss wants to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance in order to sideline his authority and damage his reputation. A large piece of Strauss’ motivation is that Oppenheimer embarrassed him once, and he (incorrectly according to the film) thinks Oppenheimer gossiped about him with Einstein.

This is so off the mark for a film like this.

If we want to watch an endlessly empathic and powerful depiction of how our base natures, traumas, and smallness drive the fate of humanity, we’ve got Succession.

What’s relevant here is that Oppenheimer (the movie) is choosing to focus on hearings that weren’t really all that consequential to anyone other than the people involved. Given his role in history, why bother? This is a creative choice that supports an egoistic focus on the centrality of an individual who is “larger than life,” which is fundamentally toxic at its core — because it outsizes the importance of “some” to the detriment of the many.

In other words, what Nolan sees as central to Oppenheimer’s story is this one man and his (fairly petty) needs. Not what he did, why he did it, the damage he created, and how we might, right now, choose something better.

Later, during a Congressional hearing to confirm (or deny) Strauss’ Cabinet appointment, Oppenheimer is effectively “vindicated” via testimony condemning Strauss’ role in Oppenheimer’s demotion. Ultimately, they are both “denied.” Oh, the humanity!

Real, perhaps. But is this the piece of this story we need, rather than the bigger picture of the ramifications of the atomic bomb on and for the world, as seen through a personal lens. If the Washington hearings-centric part of the film had touched on Mccarthyism in some new way, perhaps that might even make some sense. But they don’t.

This is in addition to time wasted on shallowly threaded themes about Oppenheimer’s romantic nature. Who cares if he’s a womanizer? That’s a bit irrelevant in the face of the start of the weapons that could still equal our collective demise. This is to say nothing of the poor use, and inexplicable nakedness, of international treasure Florence Pugh. There is waste everywhere in this film.

Perhaps there are some cries of “But it’s based on a book.” So what? It didn’t have to be. Nor did it have to adhere to that book sans imagination. It’s an adaptation of a life, whichever way you slice it.

Who and What Deserves Our Attention?

There is a decent (though, not revelatory) movie about building the bomb and wrestling with its consequences (the latter of which, again, there is shockingly little of) in about an hour and a half. An hour and a half that could have also easily humanized Oppenheimer, allowing us to understand more of what was driving him as it relates to the weapon, which, again, this film fails to depict in a manner we can sink our teeth into. Seemingly, it was his dream to work on a physics project in New Mexico. If that self-motivated goal is reason enough, well then, we have our answer on why we as a species may actually extinct itself.

There is a potentially great movie here, if the filmmakers had chosen excise all the (overwrought, though gorgeously shot) nonsense, and take that extra hour and a half (of a three-hour runtime) to focus on the depiction of a fully developed character who represents those global consequences via a specific story: The story of a specific (and known to us, the audience) Japanese citizen, seen in the same time periods that we follow Oppenheimer, until their lives inevitably, tragically, and profoundly consequently, collide.

That may have felt resonant.

Yet, Nolan’s choices inevitably default to what has been done before cinematically, rather than offering a new, and needed, perspective.

Once upon a time, we believed that the story of the creation of Facebook was about how Mark Zuckerberg outsmarted two hulky twins. But, it’s not that at all, as we’ve seen. It’s everything it wrought, which he didn’t stop. The story of a man overcoming his geekiness, having sex with lovely women, and succeeding professionally is just the story we’re used to. It’s not actually what’s meaningful — to us.

The fact that this film thinks that Oppenheimer’s reputational woes are what’s crucial says everything. The truth is, his feelings are irrelevant. As is whether he was an a**hole, or not. It’s of no consequence if he was wronged (maybe) by a man he accidentally humiliated. And discovering that he was vindicated in their little boy’s fight (and given a shiny medal for his efforts) is utterly devoid of value.

It’s all ego, ego, ego… What’s essential is that over a hundred thousand people died as a result of a terrible idea implemented by brilliant (yet staggeringly limited) minds, who wouldn’t listen to reason when they could have. We need to hear the stories of those people who lost their lives in an (entirely unnecessary) show of force. Only one reason is that their ancestors are likely the ones motivated to think through actual solutions for what we’re facing now.

But, Oppenheimer doesn’t care about them, and it’s got nothing new to say.

Do you want to know why filmgoers will know that the sequences featuring government procedural hearings are weighty and essential? (Oscar-worthy, even?) Because they’re shot on 70mm black and white film and have lots of (again, very good) acting. (In other words, it can’t wait to tell you just how important you need to understand that it is.) Its high-brow razzle dazzle at its best. But at its center, it’s just as devoid of crucial, fresh ideas as anyone saying, “We’ve gotta do it before the other guy does.”

Oppenheimer is outdated and clinging to the past in all the ways that are harmful, and avoiding innovation in the manner that matters to us if we’re to save this planet (or the human species): one of the mind and spirit. The film does not seem to have the ability to put its gaze anywhere other than the most obvious, and often least meaningful, targets.

Its worst crime is that it is structurally built to (cinematically) “sell” the successful test of the bomb as a triumphant moment. There’s lots of important and fast-paced walk and talks, a propulsive feel, setbacks, obstacles, and driving sound. Everything is (very well) designed to tell you that this is leading somewhere astonishing. Then, just before the bomb drops, silence… followed by the infamous recitation of the Bhagavad Gita line, “I have become death the destroyer of worlds.” Well, congratulations on a successful set up and sequence. There was clapping in my theater when the bomb hit.

Brava! Everyone gets to — soul-crushingly — miss the point together.

And the thing is, Christopher Nolan is too good of a filmmaker not to understand the tension that he was building and releasing. This was meant to feel like an achievement, and we’re trained (by what we’ve watched previously) to subconsciously interpret that as “good”: a positive outcome. He could have just as easily used the tools of cinematic storytelling at his disposal to subvert that, and deliver a different (better) conscious and subconscious message to the audience.

As to that now-famous line, some say that Oppenheimer was effectively proclaiming himself a God. While others say he meant he was “compelled by the God/new power nuclear energy to be a force of destruction.” Neither is true. He was a man who made bad choices.

There were scientists that didn’t take part in the project, and later, many who advocated against using the bomb, particularly with the war all but over. Oppenheimer made neither of those choices. In fact, as the film depicts, there was an “almost zero” possibility (meaning some degree of potentiality) the bomb would have ignited the atmosphere, quite literally destroying all of the planet just in the testing phase. Again, a phase they reached when they were already pretty much victorious, and certainly the Nazis weren’t getting a bomb of their own. Yet, they pressed on, without the knowledge or consent of the very lives they risked.

At one point in this film Oppenheimer’s wife (played by Emily Blunt) says of death related to his infidelity, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then have us feel sorry for you that there were consequences.” This is as close as the film gets to holding him accountable, and it really is a cop out. Because, Oppenheimer (the film) does want us to feel sorry for him in the end. Again, over a really petty gripe that equalled him losing some privilege.

Perhaps this film isn’t asking the truly salient questions because the creators aren’t able to step outside of their own embedded systems to know that there are more important questions. In other words, they’re taking it as a given that Oppenheimer had no choice, and was acting, therefore, heroically — and again, the film structurally sets us up to see him in this light. If that’s the case, then we need creators, and thinkers at large, who are able to open the door to better, more useful questions and perspectives. Those who won’t take norms as a given. Because the norms we currently have are driving us on an inevitable path to our own end.

These aren’t just stale notions: they’re going to, quite literally, destroy us.

Barbie and the Art of Being Relevant, With a Sense Of Humor

It would be unimaginable to propose that Barbie (the film, not the literal world-polluting plastic doll nor the cultural symbol that attacked women’s sense of self for decades) is the solution to the problems that Oppenheimer, and his ilks’, thinking created. (But what if we did?)

We frequently dismiss the most relevant aspects of our lives as being less so, because they don’t come with the grave approval or consideration of an (imagined or real) outside validating source. We may limit the investment in our relationships in favor of our careers, and so on. How often do we undermine something, naming it fluff, because, at its core, it’s joyful — and centered on the heart?

The basic premise of Barbie, the film, is that things are all but perfect for “Stereotypical” Barbie (Margot Robbie) in Barbieland. Though not so much for Ken (Ryan Gosling), who is — along with the other Kens — all but an accessory to the primary dolls (the Barbies). When Robbie’s character starts to experience inexplicable (human) flaws, she must travel to the “real world” to seek the girl who is playing with her, and thus creating this unwanted frailty. Ken decides to travel with her, and discovers the joys of the patriarchy.

A battle for Barbieland, and for their individual and collective identities, ensues.

Barbie is a genuinely brilliant, funny script that is executed with a stunningly deft hand. It also has something real to say, and a novel approach to do so. Two hundred writers could have walked into a general meeting with Mattel and walked out with a solid take on a story, which may or may not have generated an entertaining film that sold dolls. What co-writer and director Greta Gerwig’s film is doing is adding to a real conversation that has implications well beyond anything as limited (and, candidly, condescending ) as “girl-power.”

It’s been fascinating to see the various takes on “what myth” the film is telling. Is it the hero’s journey, or the heroine’s? There’s one interpretation that makes note of some interesting links to the myth of Inanna (the story of a Queen reclaiming her throne after a visit to the underworld).

The truth is, Barbie can’t be boxed in (yep) that way, because it contains aspects of various mythological stories and structures, while also boasting of a (Oscarcast-worthy) dance number, and perhaps the best Snyder cut joke to date. We won’t go too far down the rabbit hole with either the hero or heroine’s journey, here, but a (very stripped down) focus for the sake of this piece is that the hero’s journey offers a bit more in terms of receiving external accolades and rewards in the end (as one point of distinction). The heroine’s journey, in a very broad sense, kind of picks up where that leaves off.

After abandoning femininity in favor of masculine systems, the protagonist attains a certain level of cultural achievement and says, “Huh, I have all this stuff. I was a part of the system… Now what?” This brings on a crisis in which they ultimately ask, “How do I integrate the depths of myself and my soul with ideas of external reward and cultural significance?” It’s more complex, but one thing it’s asking us to think about is: “What does happiness truly mean and look like to me as my most complete self?” And, importantly, outside of the context of cultural validations such as money, ego-driven success, and accolades.

Barbie is a movie that celebrates humanity in all its simple, sometimes ugly, often easily missed glory, as seen through the eyes of a doll meant to represent an idealized version of it. There are several sequences in which Robbie’s Barbie soaks in the subtle, and not so subtle, pieces of joy available to us every day if we look for them (and aren’t distracted by pain-causing drives): the wind in the trees, laughing with family, the sunshine while waiting for a bus, and the face of a woman who is old enough to have seen it all, and love herself through it.

This is important, because, as noted, the ambition to win (often financially, but also in other respects) at all costs has stripped of us our ability to act in accordance with our own, long-term, interests. Barbie, effectively, suggests that we slow down and put our eyes back on what’s truly essential.

The heroine’s journey is about coming into our own sense of self, fully, putting external drives in their proper place, and in so doing, changing the world around us. What’s interesting about this film is that a number of characters experience this transformation, perhaps most centrally Robbie’s Barbie and America Fererra’s Gloria (a mom who works for Mattel and is struggling with the loss of connection with her teen daughter). There is also an element of healing the mother/daughter split that is present in the heroine’s journey, which Ferrera’s character embodies, along with Ariana Greenblatt’s Sascha, her daughter. The point is, multiple characters are taking their own hero and/or heroine’s journey, which impacts the whole. It’s the intersection of the community and (true) individual good that saves the day in this film.

(Interestingly enough, this last season of the Max comedy The Other Two really captured the heroine’s journey.)

Barbie doesn’t actually fall squarely into the trajectory of the hero or heroin’s journey, and that’s part of the film’s brilliance. The heroine (in that mythological structure) must travel into her darkness, the underworld, and her shadow. (The hero must do some of this as well, of course, it’s simply more central in the heroine’s journey.) Barbie’s underworld is our world, the “real” world, where she must face the consequences of the pain she (as an idol) inadvertently caused. Barbie, the film, is subversion and acknowledgment of what that symbol has meant in the world, as seen through a specific, individual lens.

This is part of personal responsibility. Truly owning — feeling — the pain we have caused. Of course, Barbie also doesn’t have the immediate answer for this pain. Nor should she. She needs the wisdom of those who suffered from it, among others.

Robbie’s Barbie is very reluctantly called to action and to leave her comfortable existence (as in the hero’s journey). She’s compelled, quite literally, by a force outside of herself. But, it’s not because she is the sole savior of this — or any — world. Quite the opposite.

This is a movie that is, in many ways, about cooperative leadership and co-owned responsibility. In Barbieland, there are the structures of our world: the President, lawyers, doctors, authors, and so on. However, there is a fluidity to how they step into leadership, based on need and available expertise.

Matriarchy or Patriarchy?

In terms of the myth of Inanna, there are some fascinating parallels. Barbie must travel to the underworld (Los Angeles) and reckon with her own objectification, and loss of (overt) power. While there, Ken, who has no sense of purpose or authority in Barbieland separate from the Barbies, becomes enamored — and frequently confused about — symbols of masculinity: like horses, and, as Clueless so aptly put it, complaint rock.

Ken returns these ideas to Barbieland, upending their order, and implementing the manosphere version of the patriarchy. So, he’s kind of the worst for that section of the film. However, in many ways, understandably so, having been so disempowered previously. This is one of the insights that the film is offering, which a lesser story may not have.

There is a key distinction between this film and the Inanna myth, and it’s salient to what Barbie (the movie) is getting right. Margot Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie is not reclaiming her own throne. Not entirely. She’s actually giving it to the rightful person. The leader of Barbieland is Issa Rae’s President Barbie, not Stereotypical Barbie. The reclamation is for all of the women who have been displaced, not just herself.

Importantly, Stereotypical Barbie isn’t able to accomplish this on her own. In fact, she’s entirely shut down until America Ferrara’s Gloria steps in. When Gloria feels doubt in her ability to succeed in saving the Barbies’ world, her daughter says “we have to try, even if it’s not perfect.” That’s likely a choice point for many of us at this time in our history, where action seems futile, but we must try anyway. Gloria chooses to accept that calling, and in so doing, she becomes the primary driver of the rescue mission. Though again, all of the Barbies (including Robbie’s) must actively participate in order for them to be successful.

Gloria is also the one who called Barbie to the real world initially, as she was experiencing a devastating split with her daughter and sense of place in the world. She activated an initiation for herself, for Barbie, and both of their worlds, all born of a desire to create a greater union, rather than a desire to advance the self or ego. The pain of those circumstances earned Gloria the wisdom she needed in order to activate, awaken, and re-empower all the Barbies. They, in turn, have the humility to listen to one who has experienced what they have not, but have (inadvertently, perhaps) been a part of creating.

In the end, there’s a joke in which Rhea Perlman’s character calls Robbie’s character “Self-Effacing” Barbie, because Robbie acknowledges that she didn’t, singularly, save the day or create a change.

It actually matters that we engage with this healthy level of humility, because no one person — or persons — will solve the existential reckoning we’re in. This is going to take a radical shift in how we perceive polarities like the individual and the collective. This kind of thinking is in direct opposition to the Oppenheimer-esque point-of-view that “only I am qualified,” (I being an individual, a nation, or a company) and “if I don’t do it, then…”

In the end, Stereotypical Barbie exits Barbieland. She doesn’t return home to rule as in the hero’s journey (or the Inanna myth). She chooses her humanity. She selects this world (in all its mess), rather to remain an ideal. She wants to have the ideas, rather than be one. The last moments of the movie solidify its genius. Because it wasn’t about Barbie becoming a CEO, or world leader, or gaining some other validating title. Rather, the focus was on her embracing a very human, often humiliating (though necessary), deeply vulnerable, and ultimately life-affirming medical need: tending to her pussy.

As to “the bad rap” that Barbie is giving men, this feels like a misreading. If anything, Barbie makes the point that a sure sign that you’re still trapped in the patriarchy is the idea that the antidote to it is the inversion: the creation of an imagined, utopic matriarchy.

The Kens are infantilized and disempowered to the degree that they are dangerous (and sad). They don’t represent men in total. They represent men out of alignment with their own dignity. Just as the Barbies, once infected with the patriarchy (which is just a system like any other, and does not represent every member of said system) are disconnected from their grace and intelligence. Barbieland isn’t a utopia and the problems haven’t been solved. It’s not an aspiration. It’s simply a mirror.

The answer to the life and death crossroads we face today isn’t to invert our systems. It can’t be found in thinking that small. Every one of us (no matter our job or role in life) is faced with daily questions as consequential as, “How do I make an ethical choice in an inherently unethical system?”

As such, we must find a path forward that looks unlike any we’ve tread before. And a “dream land” or house, or imagined intellectualized paradise that discounts our essential humanity isn’t going to cut it. Barbie actually gets this.

We’ve Got Questions, Barbie’s Got Answers

Solutions to embedded problems aren’t going to be found with the same thinking that created them — a true pattern interrupt is needed. So, it’s equally unlikely that the people who are thriving in these systems will be the cure for them. At least not on their own, and without the benefit of those who have new ideas. Ideas that were born because the people offering them have needed to develop ways to exist without the immediate benefits of our current structures. In other words, those outside of the system. Also, possibly, just everyday people, as Barbie proposes via America Ferrera’s character.

In the movie version of life where a tidal wave shatters Los Angeles and 13 very special and important people get on a ship, I have no illusions about where I’d be. I’m drowning in that wave with everyone else. But perhaps it’s people like us who can help spark some ideas. Because we’re not getting on that ship, we’re motivated to do so.

I’d also make the argument that it’s also the more “important” one. We should not disregard the knowledge of those who created these A.I. (and other) tools as they ring alarm bells now. However, if they’d had true wisdom, would they have created and deployed these technologies in the first place? Would they not have, possibly, found a different, as yet unforeseen path? One that does not fall back on the excuse of, “but the other guys” as if that’s the flat bottom of human thinking and capability. They’re far too smart to truly believe that, and too brilliant not to have been able to predict the perilous outcomes.

They simply chose to move ahead anyway. Yes, they must be part of the solution, but not all on their own, and without input from the very lives they are already negatively impacting. They’ll have to take their medicine just like Barbie did straight from a ruthless adolescent mouth.

A movie, like Oppenheimer, dedicated to one such person’s angst about his own ruinous work isn’t what we need. Worse still, a movie that is largely about his unrelated angst. His egoic emotions aren’t useful to explore. We’re all too familiar. What’s at issue is an entire culture reformed in the face of the atomic bomb.

Barbie calls the status quo on its crap and offers a new vision. Oppenheimer is not only upholding — but clinging to, and celebrating — a status quo that has brought us to a crushing confluence of crises. Simply in the design of the film, in who it centers, in the way it’s constructed, it is doing that. The single man, with such weight on his shoulders… (Who in reality needed scores of people and support to “achieve” what he did.) This film is the essence of the systems that got us here.

Barbie, however, is a film that is at once scathingly funny, deeply loving, an expression of awe in the face of the mundane, about the individual in collaboration with community as the solution to ills, and the embodiment of a number of rooted cultural myths.

When all is said and done, Barbie really is just the better movie. There is also an argument to be made that it’s the more “important” one.'

#Oppenheimer#Barbie#A.I.#Christopher Nolan#Margot Robbie#Ryan Gosling#Ken#Emily Blunt#Kitty#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Cillian Murphy#Robert Downey Jr.#Lewis Strauss#Florence Pugh#Bhagavad Gita#America Ferrera#Gloria#Mattel#Greta Gerwig#Rhea Perlman#Issa Rae

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frog Politics Update!

It’s a bit happier today, so don’t worry!

Chicken Nugget and Croissant have been married! Minerva McGonagall officiated their wedding, and they will be adopting a tadpole soon!

on the subject of the War, Egg Ramen and I have been very busy with negotiations. King Se’quinn has agreed to many terms, but we’re not quite done. One such agreement has been that we will be sending Geoffrey to a corrective program with the Lizards. I, for one, am very happy about this. Geoffrey needs it.

Since I’m on hiatus, I will be posting less, but know that things are going well and the frogs are flourishing!

shroomie out!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top Things to Do in Bentota for a Perfect Island Getaway

Bentota, located along Sri Lanka's stunning southwest coastline, is known for its breathtaking natural beauty, pristine beaches, and a variety of activities that cater to travelers seeking both adventure and relaxation. If you're planning a trip to this tropical paradise, here's a guide to the top things to do in Bentota that will make your vacation unforgettable.

1. Sail Down the Bentota River

A river safari down the Bentota River is a must for nature lovers. Glide through mangrove forests and keep your eyes peeled for wildlife such as birds, monitor lizards, and even crocodiles. It’s one of the more serene things to do in Bentota, offering a peaceful escape from the hustle and bustle of daily life.

2. Soak Up the Sun at Bentota Beach

Bentota Beach is a sun-seeker's dream come true. The long stretch of golden sand is perfect for sunbathing, swimming, and leisurely beach walks. For more adventurous spirits, the beach also offers plenty of opportunities for water sports like surfing, windsurfing, and snorkeling. It's no surprise that lounging by the ocean is one of the top things to do in Bentota.

3. Marvel at the Kande Viharaya Buddha Statue

The Kande Viharaya Temple is a cultural landmark you won’t want to miss. It houses one of the tallest sitting Buddha statues in Sri Lanka, standing majestically over the temple grounds. Visiting this iconic site is one of the most awe-inspiring things to do in Bentota, giving you insight into the island's rich spiritual heritage.

4. Explore the Lunuganga Estate

Lunuganga Estate, the former residence of famed architect Geoffrey Bawa, is a garden paradise that will captivate any visitor. Wander through the beautifully landscaped gardens, with views of the tranquil lake, and experience the seamless blend of architecture and nature. This visit is one of the most unique things to do in Bentota, particularly for art and architecture enthusiasts.

5. Stay at Thaala Bentota

After a day of exploring the best that Bentota has to offer, there’s no better place to unwind than at Thaala Bentota. This luxurious beachfront resort offers the perfect balance of relaxation and elegance, providing an unforgettable base for your Bentota adventures.

6. Visit the Kosgoda Turtle Hatchery

Located just a short drive from Bentota, the Kosgoda Turtle Hatchery is a must-visit for anyone interested in marine life. The hatchery works to protect endangered sea turtles, and visitors can witness the entire conservation process, including the release of baby turtles into the ocean. This eco-friendly activity is one of the most rewarding things to do in Bentota.

7. Enjoy a Traditional Ayurvedic Treatment

Sri Lanka is famous for its Ayurvedic wellness practices, and Bentota is home to many spas offering authentic treatments. Whether you're looking for a relaxing massage or a complete wellness retreat, indulging in Ayurveda is one of the most rejuvenating things to do in Bentota.

Conclusion

Bentota offers a rich variety of experiences that cater to all types of travelers. Whether you're interested in relaxing on the beach, exploring cultural landmarks, or embarking on wildlife adventures, there’s no shortage of exciting things to do in Bentota. For a truly luxurious experience, be sure to stay at Thaala Bentota, the perfect complement to your Bentota getaway.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ian Mond Reviews By Force Alone by Lavie Tidhar

June 3, 2020 Ian Mond

Lavie Tidhar has built a career out of not playing it safe. Over the last decade he has written bold, provocative novels that, with a flair for metafiction and inspired by the pulps (both hard-boiled and genre), reimagine Osama bin Laden as a pulp-fiction hero (Osama), cast Hitler as a private detective (A Man Lies Dreaming), and propose an alternate history where the Jewish homeland is established in Uganda (Unholy Land). Alongside Central Station and Martian Sands, these works have dug deep into Tidhar’s cultural background (he was born in Israel; his grandparents were Holocaust survivors) while asking difficult, confronting questions about subjects like colonialism and the price of statehood and sovereignty. Now that Tidhar lives in London, and given the political nature of his work, it’s not entirely surprising that he would shift his focus to the question of nationalism and Brexit. To that end, with his latest novel, By Force Alone, Tidhar takes a mythology the English hold dear, the legend of King Arthur, and goes to town with it.

While the opening page of By Force Alone diverges from Historia Regum Britanniae – Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th-century account of the Kings of Briton that first introduces Arthur – by having Uther, rather than his brother, usurp the throne from King Vortigern, the first section of the novel follows many of the same plot-beats laid down by Monmouth. This includes the comet, shaped like a dragon, that Uther spies on the way to battle and, more importantly, Merlin’s role in the birth of Arthur, assisting Uther to deceive and rape Lady Igraine. It’s in the character of Merlin, who is described as “pale and pretty with straw blond hair… [with eyes that] remind one of a cat or a lizard or a snake,” that Tidhar begins to make his mark. Not only does Merlin swear like a trooper (though, to be fair, so does everyone), the wise and kind wizard of legend is replaced by an amoral, half-human creature who thrives on power and dominance. Things go off the canonical rails (in a good way) when Arthur is introduced in Part Two. It’s about 15 years since the death of Uther, and young Arthur, who has no idea of his lineage, is a ruthless, power-hungry gangster and drug-lord running goblin fruit (a powerful narcotic) up and down the mean streets of fifth-century London. This Scorsese (or Peaky Blinders) reframing of Arthur – “Elyan the White’s in charge of mixing, Owain and Geraint package and wrap, Kay does the counting and the numbers” – is the very reason why I read Tidhar’s fiction: it’s playful, yes, but with a seriousness that makes it all the more enjoyable. Tidhar doesn’t stop there. Throughout the novel, and with an assortment of legendary characters to choose from, he presents us with an arms-dealing Lady of the Lake; a Lancelot with crazy kung-fu skills; and a Galahad – known for his purity because “he always puts a sheath upon his sword” – who runs a bar and brothel in Camelot.

For all its foul language and radical deconstruction, of which I’ve provided only a taste (you should see what Tidhar does with the Holy Grail), By Force Alone isn’t a desecration of the Arthurian romances. Instead, he pays homage to the writers and poets – Robert Wace, Chretien de Troyes, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and Thomas Mallory (just to name a few) – who took their turn in adapting and refining Monmouth’s text. As Tidhar points out in his fascinating Afterword to the novel, the great irony about the additions to Monmouth’s “historical” account is that several key aspects of the mythology, namely Lancelot, The Lady of the Lake, and the search for the Holy Grail, wouldn’t exist if not for three European writers – two French and one German. It makes you wonder whether Boris Johnson, as part of the transition phase of Brexit, will hand those elements of the mythology back to the European Union. On that note, while Tidhar has a great deal of fun breaking apart, then sticking together Arthur’s story, he is careful to maintain several historical features of the period, specifically that Arthur’s Britain faced an existential threat from invading Picts, Angles, and Saxons. What this means, and what never occurred to me until I’d read By Force Alone, is that the descendants of Arthur’s enemies have, for nine centuries, co-opted the myth as an embodiment of all that’s English (and by extension white). Tidhar’s argument isn’t that there’s no such thing as national identity, but just as there are multiple versions of Arthur’s story, influenced by writers from France, Germany, and now Israel, no culture or ethnicity is ever as homogenous as it’s depicted. If that’s all sounds a little too deep and meaningful, fear not, because By Force Alone is a jolt of pure entertainment, a brilliant, revisionist blend of magic, crime syndicates, and Kung-fu knights.

0 notes

Text

Episode 023 - Sports

Backsliders - Savage (Fun Things)

Viagra Boys - Sports AC/DC - Play Ball

Ministry - Jesus Built My Hotrod (Redline/Whiteline Mix) Southern Culture On The Skids - Dirt Track Date

The Hanson Brothers - The Hockey Song The Hanson Brothers - My Game The Hanson Brothers - Rookie Of The Year

Suicidal Tendencies - Surf And Slam Suicidal Tendencies - Possessed To Skate

Spermbirds - My God Rides A Skateboard Ramones - Surfin' Bird (The Trashmen) Descendents - Tonyage Fuckemos - Love 40

Hard-Ons - Surf On Your Face Man Or Astroman? - Surf Terror

TISM - Shut Up - The Footy's On The Radio Brady Bunch Lawnmower Massacre - Goofball Aloi Head & The Victor Motors - Ball….Yes Spiderbait - Footy King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard - Footy Footy

Geoffrey Oi!Cott - LBW Geoffrey Oi!Cott - Get Padded Up Mate Geoffrey Oi!Cott - Ashes To Ashes

Giuda - Number 10 Hard Skin - Millwall Mark Turbonegro - I Got Erection (St. Pauli Version)

Cockney Rejects - War On The Terraces Cockney Rejects - I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles Angelic Upstarts - Blood On The Terraces Cock Sparrer - Running Riot

C.O.F.F.I.N. - Locals Only The Dangermen - Surf Left Alright

Dead Kennedys - Jock O Rama The Hanson Brothers - Danielle (She Don't Care About Hockey)

Steel Panther - Just Like Tiger Woods

youtube

0 notes

Text

//Muse tag drop

#🌰 the acorn tactician (sally)#⚔️ little boy soldier (antoine)#💥 belle in the machine (bunnie)#🔧 the battle technician (rotor)#💾 the living ai (nicole)#🐲 mythical lizard (dulcy)#🛡️ the acorn prince (elias)#🎀 history repeats itself (ana)#🔫 the freedom soldier (julie)#🌺 buzzing heroine (saffron)#🎭 the exiled councilwoman (gold)#⚡ the rookie (bridgette)#🏹 legacy commander (geoffrey)#🗡️ former treasure hunter (fiona)#🎹 perfect is me (sonia)

0 notes

Photo

Cover splash page for the Intelligent Life animated series!

#intelligent life#cartoon#cartoon series#series development#illustration#cartoon illustration#geoffrey#geoffrey the lizard#puddles#audrey#chap#chap the cactus#david perry#digital illustration#character design#pitch bible#cover page#splash page

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun behind the scenes:

Sir Geoffrey originated as one of my Elden Ring characters, the armour set I wore at the start of that playthrough was called the scale armour, and is made out of the hide of some giant lizard, which inspired the whole idea of Sir Geoffrey’s armour.

Also, during that playthrough (I think it was my 5th one), I’d gotten good at the main big bosses so didn’t struggle, but kept getting myself killed by random mobs like rats, which inspired me to make it a character trait of Sir Geoffrey that he is actually quite incompetent against smaller foes compared to large beasts.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, nice to be back on Tumblr after a long break from it.

In any event, I kind of want to get your thoughts on something. On SpaceBattles Forums, The Egg Topic thread for Sonic fan content to be specific, a few users and I discussed how different things would be if Sally Acorn and Naugus were the protagonist/antagonist duo of SATAM and its slight Archie adaptation instead of the usual Sonic versus Robotnik tango. I think there’s some good basis for them being archenemies after Archie took Naugus’s onetime antagonism in SATAM and made him into quite the Jafar/Skeletor with his magic and manipulations compared to Robotnik’s technocratic style of military dictatorship akin to Hordak’s.

We were thinking that, as a result of Naugus usurping Sally’s royal family from power in whatever way workable, the pollution angle that makes Robotnik/Eggman such a bad ruler would be replaced with Naugus’s preaching of magical supremacy and the “evils” of advanced science from artificial intelligences with limitless data storage to modern medicine, and anyone who opposes his decrees would be given the crystal version of Roboticization.

As for minions, while I did find the Post-Super Genesis Wave connection between Naugus and Witchcart as blood relatives a bit iffy, that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be connected in some form, and aside from her and the Witchcarters, I was thinking that his Zone of Silence subjects (Kodos, Uma Arachnis, Feist, and Sally’s brainwashed father) would have some part to play in Naugus’s regime regardless of their own secret goals, Geoffrey St. John would be a spy with a conscious, and with a great deal of crystalline magic, the evil tyrant wizard would have an endless army of crystal soldiers.

Thoughts?

Firstly, my apologies for taking so long on this. It's a bit of a bad habit that I need to break.

Anyway.

Much of what you describe would indeed check out- Sally and Naugus having ripe grounds for a personal enmity, the pollution aspect of things being tossed out given that Naugus' magic renders such things null and void and so on and so forth. It seems like you've got the angles you want to cover, covered pretty well. Given that Wendy Witchcart's original schtick was turning things into crystal (allegedly), then it'd be simple to suggest that Witchcart was a fellow Ixian sorcerer (or whatever you'd have Naugus) who simply went her own way and is off doing her own thing out of Naugus'.

And you'd be correct that virtually all of Naugus' subordinates would probably be trying to figure out ways from under him. So yeah, I'd say you got this pretty thoroughly thought out. I don't really have much more of anything pertinent to add about that, though I rather like the idea of Naugus using crystaline constructs to serve as his rank and file minions. Granted, those odd lizard people in the Zone of Silence never got much play either…

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

LiC guys as the sinister six? I was going to make suggestions but the only ones I can think of is Guildford as Electro and Philip as the Green Goblin. I can't decide for the others.

the fycking sound i made when i read this ask good god

yeah philip's good for norman, especially because of his weird relationship with his son

i'm gonna go with william for otto because they're both mean autistic bisexuals and i'm pretty unabashed when it comes to playing favorites

guildford's a good choice for electro, they're both bitter and have a bit of a complex regarding people paying attention to them

i'll go with george for sandman because they're both The Nice One (relatively speaking) Who Cares About Their Kid

i'll go with albert for the lizard because he's a logical thinker who sometimes can get. hung up on a certain idea and doesn't know when to turn back

and geoffrey for venom because they both have that Feral Energy™ (also geoffrey would think venom's design is fucking sick)

#sdfghjhgfdsdfgh thank you for this anon you made me smile#they're a bad band and an even worse supervillain team#no coordination#six oc hell#redlady speaks#the actual historical figures are watching this from the afterlife like 'what'

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@monarchartstuff 's elegant lizard man, Geoffrey Riverwell! A character who can make epic entrances in the Cipherball RP setting.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

is there any game that could surpass worldbuilding like: you're a mail carrier in the (future) ole wild west, and you're given the opportunity and quite the incentive to murder geoffrey bayzose in his future pod. but also you could kill this honky tonk new money motherfucker voiced by chandler bing. and/or some fascists. you want a mutant friend? a cyborg dog? you want to help some irradiated people go to the moon? wanna listen to some smooth jazz, or would you prefer bluegrass? wantna get radiation poisoning? watch out for the giant lizards and try not to get crucified by the Rome LARPers. should the robots be armed, or do you want them to do stuff to your butt? the choices are endless, but you will cry when it's over and probably realize you're gayer than you previously thought

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 in 2020

I was tagged by my friends @princess-of-france and @chaotic-archaeologist to list 20 books and/or goals for 2020. I meant to do this earlier but my computer restarted and I had forgotten to save it. Whoops.

20 books to read (some in progress) in no real order

1. The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric S. Raymond (currently reading)

2. Word By Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries by Kory Stamper (currently reading)

3. Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English by John McWhorter (Currently reading)

4. The Bear Pit by Andrew Barlow (currently reading)

5. Head First Learn To Code by Eric Freeman (currently reading)

6. Crispin: At the Edge of the World by Avi (currently reading)

7. The Wheel of Fortune by Susan Howatch

8. The Heron’s Catch by Susan Curran

9. L'homme au chaperon vert by Suzy Arnaud-Valence

10. Anne de Bretagne : l'héritage interdit by Alan Simon

11. The Follies of the King by Jean Plaidy (hopefully alongside @nuingiliath!)

12. Political Allegory in Late-Medieval England by Ann W. Astell

13. Vie de Charles d’Orléans by Pierre Champion

14. The Legacy, the Testament, and Other Poems of Francois Villon by Francois Villon

15. Guide to Programming for the Digital Humanities: Lessons for Introductory Python by Brian Kokensparger

16. The Man of Law’s Tale, The Tale of Sir Melibee, and The Parson’s Tale by Geoffrey Chaucer (the only ones we didn’t fully read last year)

17. A Guide to Editing Middle English by Vincent McCarren

18. The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria by Tracy Adams

19. The Book of the Dun Cow by Walter Wangerin, Jr. (reread)

20. Terrible Lizard: The First Dinosaur Hunters and the Birth of a New Science by Deborah Cadbury

Some Goals (again, in no particular order)

1. Pass algebra this semester and college algebra next semester with at least a B

2. Answer messages more often (I’m trying!)

3. Keep up with my Day Timer dad gave me

4. Buy a new cell phone (preferably one that you don’t have to shake like an Etch-a-sketch to focus it to take a picture)

5. Get somewhat over my crippling self-doubt

6. Learn Python

7. Transcribe at least a fifth of Harley MS 682

8. Get back to learning French

9. Start work on my medieval resources website again

10. Finish at least one of my long-term WIP fics

11. Get completely over the friend I no longer talk to

12. Talk to my friends more

13. Go to bed at a more reasonable time

#all my friends have been tagged at this point i think#anyone who wants to do this can!#fyo goes to college

11 notes

·

View notes