#funny silly story stakes building demands it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

TRULY! If not a cop then a government pawn and ain’t that just the same at the end of the day here

Judge: I sentence you-

MC: Do your worst. I'm not afraid of death.

Judge: To serve the state as part of the law enforcement.

MC: WHAT. A FUCKING COP??? WHY DONT YOU JUST SHOOT ME

MC the second they enter the city:

#asks#memes#poor poor mc#it’s alright there are worse positions to be in#erm. that you will be in#sorry chief#funny silly story stakes building demands it

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

you book purists make me laugh because the book adaption would’ve made the show a snoozefest, where edwina would get 10 lines max, anthony would be the guy who kicked kate and barely apologized and later demanded marital rights from her, and a corny ass bee scene forced them to get married. the reordered events worked to their advantage and raised the stakes of their relationship where they got to choose in the end . the ONLY thing that should’ve been kept from the book is the storm trauma everything else being binned was a blessing

With all due respect Anon without us so called book purists there would be NO show. May I remind you that Bridgerton as a book series existed for 22 years before Netflix got their hands on it.

22 years of people reading about that same plotline you seem to disdain so much and liking it enough to get the attention of a media giant like Netflix

So do have some consideration.

Also Edwina needed development yes, but then again so did all the secondary characters in all the novels, Julia Quinn wrote romance and romance is generally focused on the character development of the couple the love story is about.

She was a perfectly kind and good character on her own. Book Edwina had a mind of her own and had the brains to tell that her sister liked Anthony from the moment she started complaining about him. She was funny and witty with Kate, in private, she was a Charlotte Lebouf type of gal who loved her sister and never let the spotlight of being the diamond get in the way of that love. To me that made her a perfectly fine, perfectly beautiful character. Furthermore Book Edwina had female friendships outside of Kate. Like Felicity and even Eloise

Show Edwina is lonely. Because outside of her sister she seems to have cero female friendships.

Heck all women in s2 are lonely! Kate, Edwina, Eloise, Marina, Violet, the Queen, Penelope. They seem to exist in either competition or judgment of each other but certainly not solidarity or friendship.

At least book Edwina was spared from that.

Next on topic The bee scene was iconic BECAUSE it was silly! It was corny and it was contrived and chief of all it was funny. The bee gave Anthony an excuse to marry Kate because he didn't have the guts to ask. But was also important for Anthony's trauma to be resolved.

The Viscount who Loved me IS the light-hearted book of the Bridgerton stories. It makes readers laugh as Anthony slowly loses it and Kate loses it as well. And yes that includes his kick and her bite and the humiliating moment that he makes her pick up the key from the floor. But there's a reason do many people cite it as their favorite in the series

Because in romance there's nothing more fun than silly contrived situations with passion simmering underneath

And guess what? I've never missed Anthony's character growth more than I do now that in the show he didn't seem to have any.

Anthony learned nothing. Not respect for women, not how to be nicer to his sister's, not how to listen to Kate. And say what you want about book Anthony and how problematic his red flags were but he LEARNED something.

He grew, overcame his trauma, his treatment of Kate and his siblings. He showed growth!

If I wanted Angst I'd be waiting for Benedict or Francesca's Story. Anthony's was supposed to be fun, filled with shenanigans that made our favorite couple learn to be less serious and more flexible.

So do allow me a moment to feel dissatisfaction. No offense for Show viewers in general, but you have been attached to the Bridgerton characters for barely a year and 3 months. I am sure you all have strong feels about the show

But Book readers had years to build up expectations and dreams and hopes. For a book reader having a character that you grew to love, for years, show cero growth in the onscreen adaptation of their book. Is something that hurts in a different way. And we are allowed to comiserate together even if it doesn't change anything

And that's the rather sad tea

#bridgerton#anthony bridgerton#kate x anthony#kate sharma#edwina sharma#edwina sheffield#what the fuck netflix

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thess vs Games Collections

There are a few things that my friends know about me:

They know I have fibromyalgia, which leaves me with a lot of chronic pain and occasional focus issues

They know that I almost certainly have undiagnosed ADHD

They know that I have somehow managed to turn a lot of my ADHD stuff into assets, or at least ways to offset everything else that’s wrong with me. I let my impulsivity fight it out with my executive dysfunction, but most of all, when the painkillers aren’t working, I let hyperfocus stand in, focusing past the pain on something fun but not too demanding while the painkillers kick in properly

They know this means I need a lot of Zen games - largely sims of the farming / crafting / colony creation / business-running variety

And finally, they know my Steam account

They know all these things. Because they know all these things, and love me enough to want to be of whatever help they can as I limp my way through life, and most of all because they are generous little buggers, they have a tendency to fling Zen games at my head at random intervals. Thankfully, most Zen games aren’t the most expensive ones, and are generally done by indie companies so I don’t have to side-eye the AAA gaming companies of the day by encouraging more money going to the abusive sons-of-bitches.

Side note: checking over my wish list, there’s, like, four games on there that aren’t indie - Tales of Arise is Bandai; like three or four of them are Square Enix (Nier and a couple of FF games), but mostly indie. I mean, obviously I’m waiting for the Horizon: Forbidden West PC port, but while Sony Interactive is obviously in the AAA space, at least Guerilla hasn’t had the kind of horrible noise made about it that companies like Activision Blizzard, Ubisoft, EA, and even CDPR have. Though on the subject of EA, I am still waiting on the next Dragon Age game. The franchise means a lot to me.

Anyway, the point is that I have had a couple of games flung at my head in the last week or so. And at least one of them has proven very helpful in the hyperfocus stakes. I’m a little behind the curve on Spiritfarer - I seem to remember that there was a fair bit of discussion about it when it came out but that was August 2020 and lockdown was in full swing and I was unemployed and on benefits and I had enough new games to power through so I tried very hard not to pay any attention to any new shininess I might like until I had a job, at which point it was no longer in the buzz. However, I was still trawling for demos on Steam and happened to trip over this one and thought, “Oh, this looks cute; I’ll give it a go”. And then the demo was over and I was going, “Wait! No! More game!” Buuuuut I am wary and I wanted to be sure that it belonged in a pride-of-place position on my wish list, so I asked the one person on my Steam friends list who had actually played the thing what they thought. Responses were: 1) “It’s fantastic!”; 2) “I should play that again since the last spirits were added in the last patch”; 3) “Here; HAVE GAME”. (I mean, payday was only a few days away but hell with it; it just means I have a bit more fun money floating around to throw the new Solasta DLC at his head.)

Anyway, yes, I have been loving it, and the balance between story and faffing about doing crafting / gardening / building and exploring the world is perfect for hyperfocus without any particular task getting too dull and taking me out of it. Also, it’s sweet and sad and lovely, as well as being funny and silly. It’s grand in its way; a game that’s both big and small at the same time. The world is big but there doesn’t always seem to be much in it, while your ship is comparatively small but it’s also huge with not just your building efforts, but also the inner lives of everyone aboard. You’re this little nexus of vibrant life floating around a big but somehow empty world, and it balances it so well. I think the only issue I could possibly raise against this game is that some of the crafting-related mini-games are fiddly as hell. However, I did manage to tamp down my perfectionist streak when I realised that even if you mess up, you still get something at the end of it, so the goal isn’t “do all of this perfectly or you lose”; it’s “do this thing the best you can and get as many crafted items as you can in the process”.

The same cannot be said for Potion Craft: Alchemy Simulator. This is so sad because it was given to me because of the personal associations between me and blending things until magic comes out (perfume, cookery, candy making etc). However, its mechanics are fiddly as fuck. It requires the kind of finesse the controls don’t really allow for and the tutorial doesn’t teach right off in any case. If someone wants a strong potion when you’re on day 1 and you’ve had no teaching in exactly what ratio of ground to whole ingredients you need to add or exactly when to stop grinding the grindables and they tell you to experiment but your ingredients are limited so that’s not actually feasible... No. Just ... no. I will probably poke at it a couple of more times just in case, but I have a feeling that one’s being relegated to the NOPE collection.

Yeah, I have a NOPE collection. It’s not for games I don’t like, exactly; it’s for games I literally cannot play for one reason or another but might try again one day. I mean, okay, Disco Elysium was one I didn’t like and didn’t get (mechanically it was very clever! I just found the intro frustrating as hell), and FFXIII is there because after about a half-hour of running down a corridor broken up with “Press X To Perform Combat” mechanics and overlong cutscenes that do not exactly move me to root for the characters or take an interest in their story or motives, I just got fed up. But mostly, it’s literal inability to play. Most of my first-person perspective games are there because migraine issues, particularlly the first two Borderlands games (though Far Cry 3 is also there because I died in the fucking tutorial and don’t know what I did wrong so screw that, and Remember Me was third person but the camera angles came out of Escher and you had limited camera control so I ended up flattened with a week-long migraine after about 20 minutes). The original Saints Row and Beyond Good and Evil got relegated to the NOPE collection because I could not manage their vehicle sections. Basically, most of the games relegated to that collection have some combination of “frustrating controls”, “migraine”, and “...the fuck is this?” Unfortunately, Potion Craft might be relegated to the NOPE collection sooner rather than later.

...I haven’t relegated the Dishonored games to the NOPE collection yet. This because I am assured from multiple sources that the franchise being all about stealth makes the shifts in gaze perspective easier to manage. However, I had to relegate Raising Petals to the NOPE collection and that was a fucking walking simulator because someone decided that they were really going to sell the fuck out of that “jounce because foot hitting ground” thing that most games only really do to any great degree when running. So even with the new medication really helping with the migraines, I’m wary of trying it again. So ... not NOPE. Just ... maybe when I’m feeling brave and have a few days where I can take to bed with a headache. Just in case.

I should have a MIGRAINE collection.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

suzani watches the Sherlock unaired pilot

Opening

- This version of John looks way more old and way more dad

- That close shot on the gun tell the viewer that John is suicidal

- The dark silhouette of the cupid statue kind of stands out. Given how the cinematography and shot framing is a lot sloppier in this version, I don’t think this is intentional. But if it was intentional, this would be a signal to the viewer that this is a love story.

- Mmm, pass on both Anderson’s beard and this way of introducing the concept of a Sherlock

- This title & credits sequence is so dated

- Anderson with no inflection is boring

- Dinner with wine is not a great place for John to be saying he’s broke

We meet Sherlock & Molly

- We start to see the beginnings of the geometric and precise framing that are the signature of the show in that one shot of Molly behind the glass

- Its nice to see that Molly’s character required almost no adjustment between the two versions. Given that she was the first character original to the show instead of the books, it’s nice to see that she stuck the landing so perfectly

- It’s starting to be really obvious how loose the editing is. There’s a lot of dead air at the beginning and end of every shot before each cut. Much better in the final version.

The lab

- This version of Sherlock seems a lot more accurate to the book Sherlock from Study in Scarlet than the series ultimately ended up being. He’s softer, more interested in interacting with other people than the antisocial, high functioning ASD (where’s the fic that explores that?) twanging brain haver he is in the first episode of season 1

- I want to read a take on Sherlock that discusses him as having ASD and interprets the violin playing and the mystery solving as his stimming techniques

- The camera shots in this scene are really starting to stand out as very different from the show. It’s not just the editing which is kind of thoughtless – these shots are poorly composed and poorly planned. I don’t think it would stand out so much if the final version of the show didn’t make so many deliberate and stylized decisions regarding with the shots and editing.

The apartment

- The extrapolation of john’s family based on the phone became much cleaner in the aired version

- Comic sans! I mean, mrs Hudson is better than that.

- Mrs Hudson definitely checked out john’s butt …

- “can I just ask … what is your street?” this was very good, if repetitive

- Sherlock needs an assistant? This sherlock has a need for human connection that the other one doesn’t – and he has a lava lamp.

- Ugh the apartment at 221B baker st looks so much more vintage in this setup. Not a fan.

- This sherlock definitely cares more about what other people think than the final version.

- Mrs Hudson is a much softer, premade character in this version. I like the final version better. She seems stronger that way.

The cab ride

- So boring. Such greenscreen. Wow.

- not just the greenscreen. the difference in the shooting and finishing of this sequence in the pilot and the aired episode is so incredibly improved that you can hardly believe there were part of the same thing.

- TOO MUCH SYNTH

- Sherlock has a far too human response to john’s compliments and more doubt in how accurate his deductions are

The crime scene

- Im glad they changed sally’s outfit, and smoothed out sherlock’s taunting of her and Anderson’s affair. Ugh I wish they’d kept sally around. This show needed more normie/casual sherlock opponents. Lack of closeups in this scene do it no favors

- They cut the Rache/Rachel clue. And btw, I do love how this was inverted from the book presentation in the show.

- “no, there are two women and three men lying dead, keep talking and there will be more” – this sherlock prioritizes people over mystery solving, and that’s a little more humanizing as well.

- When he’s deconstructing the scene around the woman in pink, there’s a switch in sherlock’s voice when he’s off camera. I’m wondering if maybe that’s a stat actor reading the script for some reason, or if they recorded the dialogue and the camera angles at the same time and forgot to switch when they were editing that shot? Makes sense given how messy the editing is throughout the pilot.

- “do you know you do that out loud?” “sorry, I’ll shut up” “No, don’t worry, it’s fine” (pleased smile) --- this exchange is so accurate to book Sherlock and Holmes

- This is not the same sally as the first episode. I had to check because I have a little bit of face blindness and there weren’t any closeups, but it’s definitely not her. Interesting how the actress who ultimately played her changed the inflection but brought very little new to the blocking.

a bit inbetween and the pink case

- No Mycroft, hmm. Don’t care for it. It added a lot with a really nice red herring feel.

- John returns to his place for absolutely no reason narratively.

- I don’t care for the red herring moment where john looks at the pink case and wonders if sally was right and talks out loud about it.

- The end exchange of this scene is awesome and should have stayed. “Donovan said you get off on this.” “And I said danger and here you are.” “DAMNIT!” It’s very funny, and it’s a fun spar between the two rather than the ultimate resigned tolerance that series John seems to settle into by season 2.

do you have a girlfriend? a boyfriend?

- Sherlock not eating is a brilliant touch, I think that should have been there.

- This version of the girlfriend boyfriend conversation is far more successful than the aired version, although I prefer the setting in the aired version. It’s flirtier, and the “Everything else is transport” line carries implications I prefer to the one we saw on on the official version.

- Sherlock knowing the cab thing ahead of time really lowers the stakes.

- Angelo and the headless nun thing is fucking beautiful. (although angelo is a bit of an upstager) But, the change in the plot to the John running and leaving the cane behind in the final version is much more relevant to the story.

- Ok, so the cabbie drugging Sherlock did show us that John is smart in his own right (we never got enough of that), but it showed us Sherlock fucking up in a way that is inconsistent with the show version of that character. For us to buy that Sherlock is other level super genius instead of just very smart, he can’t make this kind of mistake. If he can’t make a mistake, then John can’t prove his own intelligence. I do think it was a good idea to put the police back in his apartment now, as it gives us more interesting and fun things about those characters, and the ultimate build to the cab ride and the incorporation of modern technology really contributed to the modernizing of the adaption.

which pill

- WHOA that cabbie did just very much threaten to molest or rape Sherlock. Although if there were no women or gay men on the script team, I can totally see the writers not realizing that this line had that connotation.

- And this version requires a lot more explaining of plotholes with dialogue in a way that is avoided in the final verion. This is unquestionably good, because there’s nothing more graceless in filmed stories than having plot explained with words, especially by a villain.

- Taking the pills out of the bottle looks silly.

- Final version cabbie is better. More self-satified and mean.

- “Either way, you’re wasted as a cabbie” is a way better line in the final.

- Taking him out of the apartment and away from the police phone call was A+ the right choice.

- Everyone know the best cops scream “Who is firing, who is firing?” when someone fires a shot.

i’ve got a blanket

- Sherlock saying “Yeah, maybe he beat me, but he’s dead” is a far shot from the man who shook a dying man and demanded to know if he was right or not. Again, this Sherlock is far more human and far less computer.

- That bit with mrs Hudson at the end was unnecessarily mean, I’m glad they cut it

- “I’m his Doctor.” – this lines should have stayed forever.

Overall thoughts

Ok, so overall changes between the pilot and the aired first episode. Plot was a lot more polished. They scrubbed every trace of human need from Sherlock, which I think was a good choice, at least for the beginning of the show. His literal only love is his own abilities as the show airs, which leaves him with a very interesting and exploitable weakness – his arrogance, where as pilot Sherlock doesn’t seem to care all that much when he makes a mistake. We did lose a couple of scenes that had a lot of good chemistry in them, but I think the plot was much improved overall for the changes. The change of Sherlock from being casually mean to people like Anderson to swatting away an irritating fly is very successful. The focus of Sherlock’s relationship with Lestrade seems of a higher priority than Watsons a little bit, so I’m glad that changed. The lead up to John shooting the cabbie was much better in the final

Honestly the pilot doesn’t look like a pilot as much as it looks like a proof of concept piece. The budget was obviously smaller: that’s why they reused the same restaurant set, it’s why the final confrontation took place in the apartment rather than a second location, that’s why the effects are missing or budgety, that’s why the editing was low-end. This as a pilot was sold on the impact of the actors and the bones of the script, not on any of the look that would ultimately make the show what it was. The color work between the first and second version of this alone was amazing. I also think that the hair change in Sherlock was an excellent choice. It offsets BC’s face/head structure in a way that plays into the strangeness of the character in a much better way. Similarly, the coat and scarf that he wears in the series do exist in the pilot, but aren’t really a signature of Sherlock’s on-screen shape design in the same way.

I think the only thing I would’ve kept is the inflection, delivery & read on the girlfriend boyfriend scene, and the return of the “I said danger and here you are” exchange.

There’s a lot of talk about Sherlock’s sexuality and what was cannon in the books. TV Sherlock they seem to be confused about (Belgravia as an episode left me really confused about what statement the writers were trying to make there, which implies that they’re either not completely sure either, or they’re too straight to understand what they’re doing). In the books, Holmes chooses not to have romantic relationship because it stops his brain from working clearly – it’s a deliberate choice based on the Victorian concept of sex (and women, because they are clearly only sex objects) diminishing the capacity for clear thought and mental performance. This is not the same as him being asexual or aromantic as we not aro/ace people understand the concept in 2019.

Based on the scene as it airs, the girlfriend/boyfriend scene would leave me with the opinion that Sherlock is not just asexual but also aromantic. Possibly one of these by choice rather than nature. Based as how the scene plays out in the unaired pilot, I would think that Sherlock is celibate and also attracted to John, more likely gay than bisexual. (There was quite a bit of smoldering going on in the Sherlock to John direction.)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

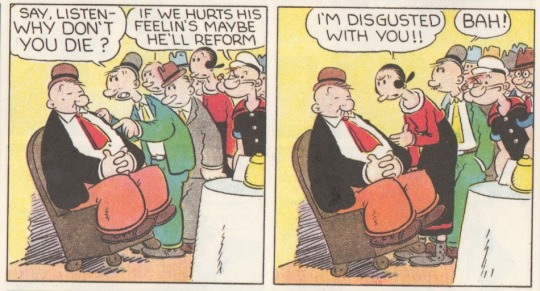

A YEAR OF READING ACKNOWLEDGED MASTERPIECES #3: E.C. SEGAR’S POPEYE

So, while the original idea behind this series was for me to read an acclaimed comic I expect I’ll like but had not yet actually read, or to read something I’d read a little of but not its entirety, covering E.C. Segar’s Popeye is something of a cheat. When Fantagraphics began their reprint series, a roommate had the first volume, of what would eventually be six, and I read that; I later ordered my own copy of volume 3, and I own a copy of The Smithsonian Collection Of Newspaper Comics, which reprints the “Plunder Island” series of Sunday strips covered in volume 4. I enjoyed all of it, but didn’t feel a pressing need to acquire more, and now Volumes 4 and 5 are out of print and command high prices on the secondary market. This motivated me to get a copy of the still-available volume 6, which might seem less appealing because it’s the last stuff Segar did before he died, and health issues led there to be periods of time where the strip was entrusted to his assistants, in sequences not included.

The editors say those strips aren’t good, I’ll take their word for it. Other people have tried to sell other Popeye product, and I’m sure some of it is quite good: There are some people who take pains to point out that the Segar comic strips are not similar to the Fleischer brothers cartoons, but I’m sure those cartoons are good fun, I generally like the stuff that studio produced. I have seen the 1980 Robert Altman movie, starring Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall, with a screenplay by Jules Feiffer and songs by Harry Nilsson, which is a notorious flop, but with some admirers: Still, it’s a slog, which the comic strip never is. IDW’s comic strip reprint line put out books collection the late eighties/early nineties run of former underground cartoonist Bobby London, what I’ve read of that stuff (just previews online) is unfunny garbage. I think they also were behind reprints of comic books by Bud Sagendorf, and a revival written by Roger Langridge, neither of which I’ve read, though Langridge’s work is always ok; good enough for me to think it’s good, not compelling or transcendent enough for me to spend money on it. It’s all work done by those who have rights to the license, which makes me view it as essentially merchandise, like a pinball game or something. The Segar stuff is where it all comes from.

While other masterpieces of the first half of the twentieth century comics page, like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat or Winsor McKay’s Little Nemo are definitely acquired tastes, Popeye was not only popular enough to make its creator a rich man back in the day, it remains functional as populist entertainment today. I feel pretty “what’s not to like?” about it, and would recommend it to whoever. It’s funny, the characters are good, there’s adventures. The humor is three quarters sitcom style character work and one quarter the sort of silliness that verges on absurdism.

This light touch separates it from the first half of the twentieth century’s “adventure strips” that didn’t age as well, despite having well-done art that would influence generations of superhero artists. Segar’s art isn’t particularly impressive, but every strip tells a joke or two, and even if you don’t laugh at every joke, you’ll appreciate its readability, especially if you’ve ever tried to read a Roy Crane comic, or even Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy. I don’t want to praise E.C. Segar by merely listing works his comics read better than, but it really is notable how many people today are basically trying to do what he did, but are failing at least in part due to not understanding that’s what they’re trying to do. If you want to do a comedic adventure story that becomes popular enough for you to be financially successful, it might be worth reading a volume of Popeye and observing its rhythms. When I was reviewing Perdy a few weeks ago, I was thinking “This basically just wants to be a R-rated Popeye.” I recently found 3/4 of the issues of the Troy Nixey-drawn comic Vinegar Teeth for a quarter each; despite that comic’s high-concept pitch involving Lovecraftian monsters, it would probably have been better if it thought of itself as being a descendant of Popeye, rather than something that could be adapted into a movie. I’ll just phrase it in the format of a popular Twitter meme: Some of you have never read Popeye, and it shows.

Lesson number one, which just sort of emerges naturally from the format of the daily strip, is you’ve got to make jokes, and they can’t just be the same one, over and over again. To that end, you need a cast of characters, who each have their own bit, and who play off each other in various ways. It is easy to see why people don’t do this: Large ensembles grow organically, and most people start telling a story with either a central character or something precisely in mind they want to chronicle. The comic strip, with its long runs originating from a practitioner’s ability to tell a joke, can be a bit freer to stumble onto something that works, without even necessarily having a title character to return to. The collections might be named after Popeye, but the comic strip being collected in these books was called Thimble Theater, which ran for a decade before Popeye showed up and circulation sky-rocketed. For a while, I think the consensus on the early stuff was it was pretty boring and hard to read before Popeye came in and livened the whole thing up, but recently there was a reprint of this earlier material, and I know the dude who reviewed it for The Comics Journal liked it, though I’m sure it’s easy to find someone at The Comics Journal who will like an old comic strip even if it’s bad. Either way, modern cartoonists don’t have Segar’s luxury, or having their work run for a half-disinterested audience until something clicks so much word spreads.

The gag-a-day pace, built around getting into new situations and adventures, itself creates a pressure to be inventive today’s graphic novelists can’t really match. After Popeye is established as a good character, prone to getting into scrapes, Segar can show us the comedy of him caring for a baby. He can also introduce Popeye’s dad, Poopdeck Pappy, that this character looks basically exactly like Popeye but is a piece of shit is a funny idea that would not occur in the early days of planning a project.

One reason why you wouldn’t necessarily do such a design choice is because, if you’re thinking of different media as a way to success, having characters with the exact same silhouette runs counter to the generally accepted rules of animation. Thimble Theatre, as per its name, is based on theater staging, rather than the more expressionist angles of film: We’re looking at characters from the side, usually seeing whoever’s talking in the same panel unless one of them is out of the room. These characters tend to have the same height, basically. Someone once said that looking at Popeye, printed six strips to a page, is kind of like looking at a page of sheet music. It’s not a particularly visually dynamic strip, the amount of black and white on a page is close to unvarying.

This is why I don’t believe in prescriptivism, or a suggestion of rules: I’m pretty sure that Popeye works because it’s not working super-hard to be visually interesting. This would be the number two lesson of what there is to learn from Popeye. I think this transparency in style is what allows this comedy/adventure hybrid to work, though I know others would blanch at this. It’s going for a big audience, and while I think this visual approach serves that end, I know why others, especially those who’ve been struck by later superhero comics or manga, would see visual excitement as the best way to achieve that goal. The audience that read newspaper comics wasn’t necessarily adept at following visual storytelling, and the sort of relationship that newspaper strips could have with a wider readership is not going to be achievable now. The folks that ride for Segar these days are mostly alt-comics people, like Sammy Harkham or Kevin Huizenga, who aren’t attempting the sort of popular entertainment extravaganzas he trafficked in.

Reading Popeye feels like reading, basically, which is a nice, contemplative experience, that not all comics can capture. I read a few pages of it before bed. Obviously, this pace is not how people consumed it in its heyday, but the pace people took it in at, a strip a day, is even more deliberate and steady, and I think, was crucial to its popularity. For a comic to be popular, it has to have characters that are interesting, obviously; there is probably no better way for an audience to build a relationship with fictional characters than over extended periods of time. This speed corresponds to the pace it was created at, one that now seems insanely luxurious to anyone whose workflow is dictated by the internet’s demand for content. It’s a total crowdpleaser, but it existed at a time where crowds could slowly gather. Popeye’s a popular entertainment from an era of reading, listening to the radio, going to plays or movies. It holds up, owing to a basic pleasantness we can understand as low stakes, and that’s helped along by the restraint of the art. It’s telling a story. It’s not a farce, crowded with visual jokes, and it’s not dictated by characters’ emoting either. I love a visually expressive art style, but here it’s important that the visuals remain “on-model,” reinforcing the stability of the characterizations. This sort of thing is also evident in Chris Onstad’s Achewood, which I would argue is the preeminent 21st century character-driven comic strip, with an audience that feels relatively “wide” rather than pointedly “niche.”

Lesson number three to how to make a popular comic is the thought I find myself thinking all the time, which is “Everyone needs to chill out.” The number one impediment to making entertainment that just quietly works is the desire to stand out and make a name for yourself as quickly as possible. This is similar to how the number one impediment to a peaceful and contented life is the demands of a failing capitalism where we are all competing for a shrinking pile of resources. To read these books now is a luxury, an indulgence, and while I don’t much go in for those, reading older comic strips carries with it this sort of nostalgic appeal for an era where it didn’t feel like everything was screaming at you for your attention all the time. As broad as Popeye is, it now possesses a certain dignity, owing to this dislocation in time from its origin. I don’t know if this felt like a feature at the time. I do think that if you are an artist that wants to be successful now, you should do what you can for the sort of circumstances that allow for genuine, long-lasting success to build, which involves a certain degree of permission to fail. Mainstream comics companies, with their mentality of “we’re going to print hundreds of comics a month, in hopes some find a niche large enough to be briefly profitable we can then try to milk for their last dollar and they quickly become exhausted,” act against this. As in a garden, there needs to be space for things to take root and grow.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Punching Up: The Last Jedi

Let me make one thing clear right off the bat: The Last Jedi is a great Star Wars movie. Folks are certainly permitted their own opinions on that, but anyone saying it’s a bad movie on the level of the prequels or “the worst Star Wars movie ever” is really quite silly.

However.

Part of the reason I love TLJ so much is that Rian Johnson really swings for the fences. He had big ambitions about what he wanted from a Star Wars movie, and he bloody well went for them, seemingly without much in the way of review by committee, at least not on the scale we’re accustomed to seeing from big studio blockbusters. This was great in terms of allowing the film to make bold decisions, but I believer it also contributed to how uneven the script turned out to be.

See, I love The Last Jedi because I can observe its ambitions (daring character choices, themes of failure and humility, feminist and anti-capitalist politics) and embrace its triumphs (beautiful cinematography, brilliant performances, meaningful stakes, a truly compelling A-plot with Rey, Luke, and Kylo). The pros outweigh the cons, and there are more pros in TLJ than in any Star Wars project since The Clone Wars and any Star Wars film since the last with “Jedi” in the title. That said, the sheer size of the movie’s reach (and runtime) left room for more obvious faults than any so far in the Disney era.

The movie’s pacing is all off. The plot meanders. Conflicts and relationships are muddled and sometimes confusing. The tone shifts around from fun romp to deathly serious, sometimes in the middle of scenes. The script needed at least one more pass. It needed a punch up.

So, in what might be the only installment of this series I do, I’ll be taking a look at the movie we got and, with the benefit of hindsight and fresh eyes, relate three major script notes that I would’ve passed along to Rian before shooting began had I been asked for some reason. To the best of my ability, these suggestions for changes do not lengthen the runtime or raise costs. Most importantly, they keep all of Rian’s ideas for settings, characters, and themes intact. They are:

1. Reduce, relocate, and reframe the Canto Bight sequence.

2. Make explicit Holdo’s suspicion of a spy on the Raddus.

3. Thematically connect the A and B plots by connecting Rose to the Force.

A lot of these feel pretty obvious and have probably been suggested by others before me, but I’m just gonna just assume that something I thought of is kinda original and would have worked out. Besides, the movie is just fine as it is, and Rian and everyone involved probably have perfectly good reasons why they didn’t go about things this way. But I really think I stumbled onto some really good Star Wars-y ideas building off these three points, and I had a ton of fun fleshing out how they’d work. Join me, will you?

1. Canto Bight

If one were to only look at reviews released in the days before The Last Jedi was released and its discourse got bogged down by dudes nitpicking minor details to justify misplaced nostalgia or obvious bigotry, one would get the sense that there was only one major issue with Episode XIII: Canto Bight. And make no mistake: the casino planet’s placement in the film is one of its most glaring flaws, though not an unforgivable one. The introduction of a fetch quest that leaves no major impact on the plot would be hard enough to justify as anything other than padding in a two hour movie; in a two and a half hour film, it’s presence just becomes puzzling.

There is an argument to be made for cutting Canto Bight from the film entirely. I’m sure the studio would have been more than happy to save a couple million dollars on makeup and visual effects. But there’s also an argument to be made that employing talented people to make cool creature and costume designs is the best reason to make these movies. And there’s also my argument: that there’s a much better place to put Canto Bight than the middle of the movie.

The Claystripe Cut of The Last Jedi would open on the casino world, with Poe, BB-8, and a recently revived Finn on the planet looking for DJ, whose role as a neutral slicer whose only loyalty can be bought is retooled slightly so that he is already being paid a great deal by the Resistance to work as an informant. Poe fills in Rose’s role of pointing out the evil at the heart of the beautiful city. The best parts of the original Canto Bight sequence; the funny BB-8 gags, the escape with the fathiers, and, most importantly, the set-up for the beautifully resonant ending with Broom Kid. As they escape on his stolen ship, DJ reveals his information: the First Order is going to attack the Resistance base!

Keeping Canto Bight preserves all Johnson’s commentary on decadent capitalism, environmentalism, and war profiteering, but placing it at the beginning and cutting it down to a ten-minute action prologue solves a whole host of problems.

First, and most pressing, it saves the second act of the film. The Last Jedi grinds to a halt when Finn and Rose fly off across the galaxy in the middle of a heated chase in the middle of deep space. The fact that this kind of mobility is apparently still available to our beleaguered protagonists saps the tension from the sequence at the heart of the movie by circumventing its central conceit- that our heroes are trapped and running out of time- and opening up too many questions and narrative demands. Viewers are kind of just left to answer for themselves why there was only one craft with hyperspace capabilities on the Resistances’s flagship, how the protagonists got a hold of it, and why they ought to care if the Raddus is destroyed if all the characters we’re invested in could have just flown off safely at any time and come back and forth as they pleased. Keeping the B-plot set in and around the Raddus and the Supremacy keeps things simple, the stakes high, and the plot moving.

Second, having Canto Bight at the start of the film introduces DJ in a much more natural and easy way. Instead of treating him like a MacGuffin and spending twenty minutes in the middle of the film to get a hold of him, DJ can just be a character in the movie. His role and screentime wouldn’t have to actually be expanded much at all, but his involvement in helping to save the Resistance and his presence in the film from the start would make his eventual subversion of the Han Solo “Greedy Jerk With a Heart of Gold” betrayal sting just a little more.

Third, this sequence would partially fix a problem that the end of the last movie forced Johnson into: namely, that it had to pick up right after The Force Awakens left off, meaning that the main characters of this new trilogy barely know each other. The lengthy gaps between the previous Episodes left room for audiences to buy that the protagonists became close friends and had plenty of other adventures with each other besides the ones we’ve seen. In Empire, this is important for driving home the stakes when the heroes are separated after they’ve apparently been together for months, if not years. When the heroes in The Last Jedi are separated, you don’t feel that, not only because no time has passed since we last saw them, but because they were barely together to start with.

Rey and Finn apparently have feelings for each other that are expressed in a single hug and a few tender looks at the very end, but they only knew each other for a few days in The Force Awakens and have only been apart for the same amount of time. The problem is worse with Finn and Poe, who, despite having great chemistry (one of my discarded notes was “MAKE IT CANON”, but, again, trying not to majorly change the movie here) have only interacted with each other for a few hours. They barely double that time in this movie, because Finn spends most of it with Rose. While the timeline in regards to Rey would be a little screwy if you stopped to think about it for too long, depicting Finn and Poe interacting on an adventure and being established friends would do a great deal to build audience connection.

Finally, placing Canto Bight at the middle starts the movie off with characters in a strange and interesting world instead of starting with Poe making “Your Mama” jokes at Hux- a fairly humorous that would be much easier to swallow if they were not the center of the first scene of the movie.

2. Holdo and Poe

This is probably the easiest of these fixes to make, practically speaking, requiring only two or three additional lines of dialogue to fix a problem that a lot of people have with The Last Jedi.

First, I’ll get it out of the way: this change is not to remove Holdo or her conflict with Poe from the movie. Laura Dern is a goddess. If I could fight for her to have been in the movies more, I absolutely would have. And the point of her subplot with Poe was pretty clear: Poe’s got a real disrespect for authority and opinions of others, particularly, it seems, from this very feminine admiral, and he needs to learn humility and self-sacrifice to become an effective leader.

Now, that said, there are problems with how this story is told. Though I’ve read many hot-takes online saying that people who didn’t like this plot are misogynist doofuses that don’t listen to women, pretty much every man and woman I know felt like her role in the story was limited to just creating extra conflict until her awesome act of self-sacrifice. The only reasoning she provides for not trusting Poe is that she doesn’t like him, and while that is all the rationale one needs in reality to obey their CO, for the purpose of storytelling it feels lacking. How do we make the point of the conflict more clear from the very beginning? And can we add anything to it to make her decision to not trust him make more sense?

A lot of people have already argued that Holdo doesn’t reveal her plan to slip away to Crait because she is worried about a spy on-board responsible for the First Order’s hyperspace tracking, but that’s left as subtext at best. Why not make it explicit text? As is, the movie has the characters figure out how lightspeed tracking works seemingly out of some educated guesses; explicitly considering other options (and even leaving ambiguous what method the First Order used) would have been a compelling direction to take the story. Holdo telling Poe to his face that she won’t tell him anything because she doesn’t trust him to keep the information private would clarify the reasoning for her decision while maintaining the subplot’s purpose of developing Poe out of his toxic masculinity; even if it was a fair point, he would still certainly resent her for questioning his loyalty. It would make even more sense if we stick with the ramifications of the first alteration and have a shady DJ lurking around the Raddus the whole time. This minor addition to the dynamic also would make Poe’s leap to calling Holdo a traitor and his decision to mutiny make more sense now that the possibility had been introduced and discussed.

A slight tweak to the dialogue alone simultaneously makes both characters more sympathetic and closes up some potential plot holes. And it costs zero dollars for additional visual effects.

3. Rose

In the first two notes, you’ll notice that the only practical alterations these changes would make to the shooting schedule would be having to get Benicio del Toro into a few scenes on the Raddus and replacing Kelly Marie Tran with Oscar Isaac in an abbreviated version of her biggest sequence. Obviously, Rose has gotten the short end of the stick thus far, and I want to rectify that with the third note by giving her a new role that fits her character better into the film’s themes. It’s tempting to not add any scenes to the movie because of its existing length, but I honestly believe that the problems with Last Jedi lie more in its pacing than content. I ultimately think adding just two or three scenes focused on Rose would not just make up for removing her from Canto Bight, but give her a bigger role in the Star Wars mythos.

I like Rose. She’s a fun audience surrogate, and Tran gives an earnest performance that I’m sure a lot of kids are going to really admire. But Rose also lies at the heart of the one part of The Last Jedi that I think is truly bad- not a nitpick (“Why doesn’t every commander just ram empty ships at lightspeed!?”), a nostalgic complaint (“Luke would never just give up!”), a minor quibble (“We don’t know Snoke’s backstory!”), or a personal grievance (”My Rey theory was so much better!”), but a genuine inconsistency with the plot, characterization, and themes that don’t make a lick of sense.

I am, of course, referring to Rose stopping Finn from sacrificing himself at the end, whispering that they won’t win the war by destroying things they hate, but saving what they love. A nice sentiment, and one that fits well with Star Wars, but one that does not mesh at all with what she did: buy Finn a few moments of extra life at the cost of allowing the First Order to kill both of them and all of the Resistance. Frankly, it doesn’t mesh at all with the Rose who was honoring the sacrifice of her sister by keeping cowards from fleeing the Raddus, and it’s just an amoral and stupid thing to do unless she somehow knew that a young Jedi-in-training the ghost of Luke Skywalker was going to show up and give them a way to escape.

Which is why, in this change, she does know. Or at least, she’s got a good feeling.

My idea really requires the addition of only one scene: Rose saying a tearful and emotional goodbye to her sister before she goes to attack the Dreadnought, seemingly knowing that she’s not going to return based off of a deep feeling (some might say “a bad feeling about this”). Because this sequence has been pushed back towards the end of the first act by Canto Bight’s re-positioning, this scene could be positioned in close proximity to Luke’s speech to Rey about the nature of the Force and how it belongs to everybody, making clear that this gut feeling is rooted in some sensitivity to the Force in regards to the lives of people Rose cares about. One extra optional scene on the Supremacy where Rose’s gut feeling kicks in right as they get caught, and we have enough set-up to justify Rose realizing as Finn rushes toward the battering ram cannon that she is not afraid of them being destroyed, trusting her instincts, and saving Finn from a needless sacrifice.

Beyond preserving the message and justifying her choice, this change fixes one other structural problem in The Last Jedi. While the theme of “learning from failure” is omnipresent, there’s relatively little else directly connecting Luke and Rey’s story to that of Rey’s friends or the rest of the universe. Everything the main characters learn and decide about having to restart the Jedi Order with a recognition that the Force actually belongs to everyone would have greater impact if the film actually showed someone who is aware of the Force without having the strength of a Skywalker still using that connection for good. Someone with a scrappy working class background who made all the difference for one of our main heroes. In hindsight, it’s kinda amazing that Rose written as the character she is and not used for that role.

So, what do you think? Am I crazy? Should I be hired as Rian’s creative consultant for the new trilogy? Should I make this a running series (ooooh, I’ve got stuff to say about Three Billboards, let me tell you...) Could you read through this wall of text? Let me know!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 12 Alignment May Vary: Prophecy of the Tomb of Haggemoth

Starting with this week’s session (post 12) I’m going to mix up my format a bit and do quicker synopsis and more DM analysis, rolling a lesson or two into each session for the enterprising or novice DM. As always, this is for my 5th edition group of three players who have completed one story arc from the Rise of Tiamet adventure path and have since embarked in earnest on a side adventure, the wonderful Tomb of Haggemoth adventure from 3rd edition.

Leaving behind the island of the Ooze, the party sets sail for the Island of Alcazar, the island where the oracle resides, and they arrive without further mishap in a couple of days.

Much of this section of the adventure is meant as set up. The idea is that the party sees the oracle, she gives them a riddle that lists three places they need to go and three things they need to find before they can access the Tomb of Haggemoth. She also rambles on for a bit about character-specific back stories and anything else the GM wants to set up. Since she can see the future, she is the perfect tool for the GM to use as foreshadow. I use her to tell the players that the priest they left in Ottoman’s Dock to take care of the Rose situation (the woman who was selling sex slaves there) has met with misfortune. It’s a set up for next session. I also drop some hooks for each of the players. For Karrina, I foreshadow her quest to find Raiden, mentioning that what she will find is not what she expects and that he believes he did not betray her. For Abenthy, I mention there is one with a great red eye searching for him, whom his father was killed by and against whom Venthusias strives to keep him hidden. For Twyin, I talk about his dead son and hint that there is something darker to his past the others do not know.

There are some other hooks here, as well—for instance, one of the other characters here to see the Oracle is a wizard named Shelackar the Vermiculate (don’t laugh). He has already seen the Oracle and she’s given him some bad news: he done effed up. How? Well, he bet his life against the hand in marriage of a sultan’s daughter that he could make it rain in a place called THE GREAT DRY DESERT. That didn’t work out so well. So he came to the Oracle to seek advice and she told him that he will die if he ever ventures into the desert. But he’ll also die if he doesn’t. This is all build up towards an adventure later in the campaign.

Other characters here can be used by the GM as desired. For instance, there is a warrior here whose lands have been overrun by orcs and he is here to see the Oracle about it. He doesn’t show up again in the pages of the campaign, but Twyin seemed pretty interested in him, so he may very well find a place yet in my version of the campaign or in some future one.

There is a twist to this part of the adventure, too. The unique coin the players have (from their patron Zennatos) which will gain them access to the Oracle is a forgery. Worse, the day they are to see the oracle, the person carrying the real coin shows up, and he is none other than The Butcher of Skago, a plantation owner with enough money and power to buy a small city. When he finds out that someone is using a forgery of his coin he flips shit and demands they be brought before him. Keep in mind this is all before they’ve actually seen the oracle, so the players have to figure out a way past this obstacle. Do they try and fight the Butcher and his men? Do they try to bribe or sweet talk him into giving him the real coin? Or do they slink away and then sneak back to the island at night, determined to force their way into the Oracle’s chambers? In our case, Abenthy tells The Butcher the truth of why they are here to see the Oracle and agrees to pay him HALF of the treasure if they get it. To watch over his investment, The Butcher sends one of his loyal men, a killer named Haymish Hardwicke, to go with them and make sure they keep their word.

Lesson: A Session of Roleplaying

There wasn’t a single roll this session aside from a couple investigation and perception checks. Everything was handled and resolved by roleplaying. Which raises a good question—how do you handle a session that’s entirely roleplaying, while keeping everyone at the table involved and engaged?

It happens to all of us. Whether because of luck, or because they’ve hit a big city with lots to do and no encounters, we all encounter sessions with no combats and not very many rolls. It is easy to write these sessions off by saying “I promise next time there will be combat!” and just gritting your teeth and getting through it. But is there a way to make these sessions exciting and memorable?

First of all, it should be said that roleplaying should be a small part of every session, because it encourages a player to get inside their character’s head (which in turn makes them more engaged in the game) and because it offers a break from tackling every obstacle by rolling dice and checking numbers on a sheet. After all, what sounds more memorable in the following scenario? You come up against the Butcher of Skago and successfully roll a 15 to convince him not to kill you for stealing his coin, or you come up against the Butcher of Skago and over the course of a conversation come up with a way to weasel out of having stolen his coin. Any player will feel more accomplished by the second, for they actually did it.

But despite roleplaying being rewarding, an entire session of it may sound like anathema to you and your players, and with good reason. Roleplaying an entire session of NPCs means coming up with multiple personalities, voices, and being ready to improvise a wealth of responses to things the players might say or ask. It means making judgement calls on how “well” the players are roleplaying their cause, rather than relying on numbers to tell you how things are going. Finally, not all players like roleplaying, and keeping these memebrs of your group engaged and entertained is challenging.

Here’s my tips, with examples from this past session, on how to keep your game flowing and cut down on your work load during such a session.

Make your conversations conflicts. A lot of times the big complaint about roleplaying is that it is “boring.” Players are here to play D&D, after all, and D&D is at its heart a battle game. Character abilities and traits have mechanical effects on dungeons and battles, not usually on conversation. Often times, though, it is not the roleplaying that is boring, it is the situation. It’s simply not fun to talk through a conversation with a shopkeep where you are trying to find the rowdiest inn in town, or buy a pair of nice pants. On the other hand, a conversation with a Dwarven miner who thinks you are after his gold and is about to bring the mine down on the both of you if you can’t convince him otherwise... that is a conversation worth having. If you are afraid your players are going to get bored, then try limiting your conversations to those that have real risk, or add some risk to your smaller conversations. In my session, one of the first NPCs they met was a steward of the island who wasn’t all that interesting but who was the gatekeeper to the Oracle and thus the only way they were going to get to see her. I had him act incredibly suspicious of the players so that the whole conversation was put on edge—so much so that when he finally asked them to turn over their coin, Twyin didn’t want to do it! He felt they would be betrayed. This took what was a necessary conversation and made it tense and thus more exciting.

Use humor. Another good way to liven up a roleplaying session is to use humor. People like to laugh and (hopefully) you are friends with all your players, so that means you (hopefully) like to laugh together! Make one of your NPCs a little goofy, or add in a funny quirk to them. After the players had met two stewards and had similar conversations with them, I was afraid things might get dull. So the third steward they met I turned into an over-zealous, over-the-top salesmen of “Oracle Trinkets.” Little wooden swords with your name engraved on it! Mugs that say “The Oracle saw my future and I was drunk!” In addition, this steward believed (wrongly) that he was good at guessing names, and jumped into conversation by guessing ridiculous names for the characters. Just be careful not to let things go overboard. If one or two characters in your town/island/castle are silly, then that makes your world a little more lively. But if every character is goofy and funny, then your players have stumbled on the Island of Misfit Toys and aren’t very likely to take anything that happens this session very seriously.

Watch and listen to your players. The simplest way to know how to set your pacing is to just pay attention to your players. Look at their body language. If they are building dice towers and nodding along dumbly to everything you say, it’s probably time to skip a few conversations and bring them to your Big Scene (see below) or to start upping the stakes dramatically (see above). Similarly, if your players seem to be asking for MORE roleplaying, don’t be afraid to give it to them. In our session, I had only intended to roleplay Shelacker out of the oracle groupies, because he is the most important, but my players wanted to split up and talk to as many of them as they could. Everyone was eager for this, so I jumped in and played out more of the conversations. I kept them brief, to save us time for the Big Scene, but I wouldn’t have done it at all if I thought my players were getting bored.

Bring in your absentee players. There is one or two players in every group who dominates in roleplaying situations. They have something to say to everyone, a witty comment always ready. They have +5 to jumping in when another player is asked a question and answering it themselves. They walk all over the dice-tower-architect described above, not to mention the shy guy who likes to roleplay but also likes to think about what he says before blurting it out. Plan some things before the session to make sure you are giving these more contemplative players some focus. In one conversation, point dramatically at your dice-tower-architect and have your NPC say, “I saw your picture on the Wanted poster at the bar! You have a price on your head!” This will make them the focus for a while. Or have an NPC set a time to meet your shy guy, and them alone, to give them some information. Don’t let the other players come. This splits the party, but it’s worth it to give some shine to players who aren’t as rambunctious and animated at the table. In my game, all of my players are good roleplayers and pretty strong personalities, but Karrina's character is naturally more silent and withdrawn. So I like to make sure that at least once during a session I put her in a place to be the focus of some important conversation. In this case, it was with Shelacker, who is one of the most interesting characters on the island. Twyin even jumped in at one point—before remembering he wasn’t at the fire where they were conversing!

Find your Big Scene. Before you go into your session, think about what is going to be accomplished during the session. Are the players going to end up with a key piece of information? Are they going to be solving a political crisis? Are they going to be talking their way out of a death sentence, or into the trust of a powerful criminal lord? Once you know this, you should also know what your big obstacle to gaining this will be, and how that obstacle will be bypassed with roleplaying. The scene where this is done is your Big Scene. There may be more than one, but these represent the “action” of your session, the moment when the stakes are highest and each word spoken could make or break the characters. Think of this as the POINT of the session. Steer your players towards this moment. If things get dull, speed them along to it. And when the Big Scene is resolved, start moving them towards the next one, or wrap up the session (if that is the last Big Scene). When preparing for your session, don’t spend too much time on the incidental bits—focus on the Big Scenes. Prepare some things your NPCs in the scene might say or want. Think on some ways the conversation might resolve and what will happen next. In my session, there were two Big Scenes. The first was when the Butcher of Skago turned up. This moment has the potential to change the entire campaign. If players decide to attack the Butcher, that makes a powerful enemy. In addition, I had to be ready to launch into combat if this happened. Instead, they chose to barter, but even this has a big effect: a new NPC added to their party and a big promise they will be expected to keep after the adventure. The other Big Scene is with the Oracle herself. The campaign suggested playing this out in fifteen minutes of real time, with players asking questions and the Oracle answering. That was a lot of material to prepare, but I was glad I did. When we got to that scene, my players seemed stunned and unsure of what to ask, so the first ten seconds or so were spent in silence. I had enough material prepared that I was able to talk for most of the fifteen minutes and steer them towards questions for the rest.

Assign a "Difficulty Class” to the roleplay. Some DMs, especially newer ones, have trouble deciding which way a conversation has gone without a dice roll. An easy way to bypass this is to make up a conversational difficulty class for your Big Scenes before the session. Think on what goal your characters have and come up with some set things they will have to say or mention in conversation in order to achieve this. Each one they say gives them a success. Then decide how many successes they need to win over their opponent, or get their goal. This number is your conversation DC, and it best ranges from 1 (easy) to 4 (very difficult). You may also wish to assign certain things negative points, and if they say those things, then you subtract them from their successes. In the Butcher of Skago scene, I had predetermined that the Butcher was going to be better disposed towards anyone who told him about the treasure hunt, anyone who played off his arrogance, and anyone who seemed actually interested in cows, while he would be very ill disposed towards anyone who made threats. During the conversation, Twyin kept throwing the Butcher intimidating looks, so I lowered the number of successes they were getting in the conversation otherwise. The end result was a decent success, so he jumped right to negotiations. I had already decided he would be willing to accept as little as 10% of the treasure as payment, but the party didn’t argue with 50%, so he happily ripped them off.

Hopefully, identifying the Big Scene will help give you a landmark to steer by when running a roleplay heavy session, and the other advice helps get you through without losing your players.

I know that last time I said I would be discussing monster/encounter building in this post, but I’m going to save that for next time, in Return to Ottoman Dock (when they are far more likely to have some encounters).

#dnd 5e#Advice for DM#Playthrough#Tomb of Haggemoth#epic#Dungeons and Dragons#Journey Log#Wizards of the Coast#fantasy#RPG

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deus Ex Machina in Films

Spoilers for Slumdog Millionaire, Jaws, Angels & Demons, Contact and Signs.

If a tale is worth the telling, then should it not be extraordinary?

From our very origins, where stories of gods and monsters were told around a flickering campfire to our modern multiplexes, it has been the stories of the most dramatic shifts in people’s lives that we long to hear. These tales bring with them an inherent problem: should the piece prove to be too fantastic, too far removed from what we can connect with, then the spell is broken. Suspension of our disbelief is only a part of this, and often a film may cause a snort if it takes a dramatic step too far, or when the mechanics of an author making a story fit can be readily sniffed out. This magical balance, of spinning a yarn but never yielding the sense that the tale itself has a fundamental ring of truth to it, has plagued storytellers for centuries and the term “Deus Ex Machina”, dating from Aeschylus, has come to be associated with this issue in the modern cinematic age.

Meaning “God from the Machine”, it refers to when a story takes a contrived turn. In Ancient Greece, there would be a literal contraption that would lower actors playing the Gods into the theatre and such divine interventions would often allow direct solutions to whatever dramatic tangle the characters found themselves in. The fine line between this dramatic “Get out of Jail Free” card and writing resolutions that thrill and inspire audiences has ensnared storytellers for millennia. Modern audiences will complain when a film hits moments of what feel like implausibility, despite the entire picture up to that point involving a man who can talk to fish or a Prime Minister courting a tea lady. The moments that shunt audiences out of the experience of watching a film are both fickle and, of course subjective and, since no storyteller sets out to leave themselves open to this vulnerability, there is seemingly no way to protect your film from it, hoping instead that a crumbling of verisimilitude never manifests.

This is different from implausibility or fantasy. Films go to huge lengths to make the audience invest in a story: the reason Jaws is held up as one of the finest the medium has to offer is not due to the convincingness of the shark but how much we have invested in the three lead characters, and the shading to make them and their worlds real to us over the first hour of the film demands our investment such that, when a 25 foot plastic shark finally leaps from the water, our terror is welded to theirs. Our human biology is a problem here, since the idea of the extraordinary is what inspires the very best stories but is undermined by our animalistic understanding of coincidence. In evolving our way to the top of the food chain, we have learned to spot patterns and are built to learn from mistakes in order to thrive, so that if an extreme event happens it is programmed into us to be intrinsically suspicious. Phrases such as “truth is stranger than fiction” are accepted truisms, and yet some films are criticised if they rely too much on remarkable events, despite this often making them the stories worth telling. The logical response would be that nobody would want to see a film in which one of the other double-O agents dies in the attempt at saving the world: show us instead the spy that survives ludicrously improbable traps to win the day.

Slumdog Millionaire is a fascinating example of this contradiction and is based around the concept of a penniless boy appearing on the world’s most famous TV quiz show. What happens, however, is far from a typical appearance and the boy, who has no schooling, is in fact using the show to search for his lost love. Along the way he is asked questions that he happens to know the answers to, with the film flashing back to explain how he would know each of these facts. Statistically this is an interesting approach: given that there are hundreds of thousands of people who must have appeared on a version of this quiz over decades, one of them would have to be ranked as the luckiest in terms of the questions they happen to have been asked and, therefore, would not their story not be the most compelling? There is an intriguing idea within the film of defining intelligence as being asked the questions that we happen to know the answers to, but the role of chance in shaping a person’s destiny can prove divisive in audiences and it is this friction that blurs the line upon which audiences’ readiness to accept the story we are spun is founded. Slumdog Millionaire is ultimately not that interested in the mechanics of this since the boy himself is not motivated by the money, using the show playfully to up the dramatic stakes and revealing more about the characters involved, but the boldness in using such a unusual framing device is relatively rare.

We can take a certain amount of improbability in our stories but the dangers of invoking anything beyond chance are arguably greater, and whilst there are many examples of outrageousness in the plotting of modern films there are few, if any, whose audacity in terms of confronting these shades of grey are as remarkable as 2009’s Angels & Demons. Having made a career from inferring conspiracies around artistic and historical fact, Dan Brown’s book is adapted by Ron Howard and builds to an unforgettable climax. A series of grisly murders are investigated by symbologist Robert Langdon and escalate to a finale in which a priest detonates an antimatter bomb in the skies above Vatican City, bailing out of his helicopter with a parachute at the last minute. We soon learn that said priest had, in fact, planned both the murders and the bomb (stolen from CERN) in order to get himself elected as Pope. As preposterous plotting goes, this is pretty much as far on a limb as even the most ridiculous of Hollywood thrillers has gone but there is something to be said for the gusto and straight face that the film commits to in bringing it to a screen. What makes it completely outrageous, however, is the concluding scene, where a kindly cardinal thanks both Langdon and God. As an atheist, Langdon demurs, but the cardinal replies that, given the remarkable nature of what has happened, how could this be anything other than God’s plan: a literal use of Deus Ex Machina in the modern cinematic age!

Angels & Demons’ approach is far from unique, although perhaps not in terms of sheer nerve. Raiders of the Lost Ark’s denouement also sees the God of the Old Testament wipe out the villains (The Big Bang Theory delighted in pointing out that, for all of Indy’s heroics, he plays no role in actually saving the world) whilst the Eagles in the Middle Earth films have a strong whiff of godliness to them. The moments when a storyteller is clearly fumbling for a way to get themselves out of a sticky corner will now be increasingly exposed online, whilst even knowing moments that try to poke fun at the fourth wall have a tendency to get lynched, such as Ocean’s 12’s set piece where Tess Ocean (played by Julia Roberts) bumps into actor Bruce Willis (played by Bruce Willis) and is then coerced into saving the day by pretending to be actress Julia Roberts, whom Tess apparently resembles. The only moments when such brazenness can be allowed are when a film dives wholeheartedly into the silliness, such as the moment in Life of Brian where our hero is saved from falling to his death by some convenient passing aliens.

Many films dance around this fault line in fiction but M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs chooses to confront it by forcing each viewer to reflect on their own choices in terms of how they each decide to see the world. Following The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable, narrative twists had become the director’s trademark so the marketing of the film was stealthy, with the only knowledge circulated that the film was centred on the frivolous phenomenon of crop circles. Audiences who had been thrilled by Shyamalan’s first two films came expecting to find another sting in the tale and, whilst they would have that expectation met, for many it was not in the manner in which they were expecting.

From its propulsive opening credits, which musically and visually invoke Saul Bass and Bernard Herrman’s work for Hitchcock, the film casts a macabre spell, introducing us to a close family broken by bereavement. As enigmatic shadows, ominous animal behaviour and melodramatic news reports seem to imply that the world may be on the verge of disaster, the film spends our time focused on this household who is living as if Armageddon has already happened. Far from casting a morose tone, however, the focus is very much on their love and support for each other and the film is surprisingly funny, with a dryness and drollness that invites you to emotionally invest in them and their world to a huge degree, with various idiosyncrasies cleverly painted in to seemingly deepen their credibility, as is the norm for this genre. Charisma was always Mel Gibson’s strongest suit but, in this film, he uses it sparingly behind an expression of a man whom life has utterly defeated; a minister who has abandoned his faith after the cruel and arbitrary loss of his wife. His performance as Graham Hess is incredible and, in one scene, he processes rage, humanity, forgiveness and sorrow within the space of a few seconds. Joaquin Phoenix plays Graham’s brother Merrill, an honest and simple man whose awkwardness belies a gently painted integrity, whilst Cherry Jones also adds considerable emotional heft as the kind and empathetic local Sheriff: the world these characters inhabit, whist harsh and simple, makes it clear that these people are good-hearted and worthy of our empathy.

Shyamalan takes what would be the hugest event in human history and focuses upon the least significant of locales. He called Signs his “most popcorn” movie and takes many cues from Spielberg, with the juxtaposition of ordinary with extraordinary, a cast of children and a troubled, failing father (literally and professionally) all Amblin tropes, and the film is notably produced by Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall. As the eeriness builds with the aid of an impeccable score from James Newton Howard, the crop circles increasingly seem to be the work of alien visitors. Throughout the film however, there is a mischievous sense of ambiguity and the film continuously undermines this fantastic possibility: Shyamalan plays on the audiences’ expectations with masterful sleight of hand, continuously teasing us with the prospect of a narrative twist that we are all trying to spot ahead of time, knowing all the while that, whilst we focus on this, our attention remains away from the ace he has hidden up his other sleeve. Everything we see seems to be developing this potential alien threat, but the film is subtly sowing very different seeds and Shyamalan uses a full array of tricks to keep our attention away from his final intentions. The most memorable of these is where Merrill watches a blurry Brazilian news report whilst hiding inside the cupboard under his stairs. This simple scene is edited to creepy perfection and, as the announcer intones “what you’re about to see may disturb you”, we share Merrill’s ghoulish excitement at finally discovering the truth behind the mystery. The reveal of a creature looming for a split second, out of focus but stalking us with predatory malevolence is one of cinemas great shocks: simple, matter of fact but unexpectedly stark. As Shyamalan tears away the ambiguity, this extraordinary image pays off the patient teasing shown by the film up to this point and, crucially, keeps us frightened for this family and what this all might mean for them.