#fourth earl of Northumberland

Text

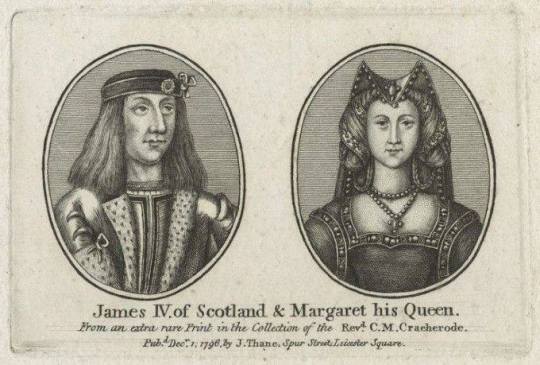

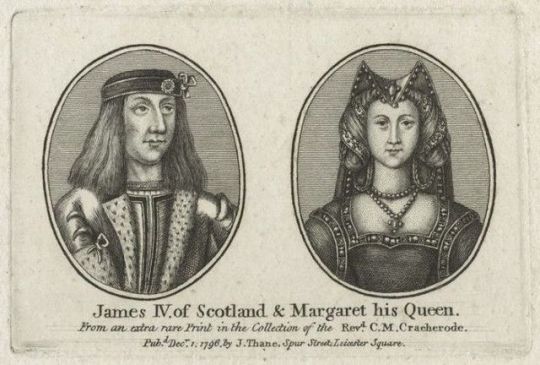

On May 28th 1503 a Papal Bull was signed by Pope Alexander VI confirming the marriage of King James IV and Margaret Tudor and the "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" between Scotland and England.

From an early age, Margaret was part of Henry VII’s negotiations for important marriages for his children and her betrothal to James IV of Scotland was made official by a treaty in 1502 even though discussions had been underway since 1496. Part of the delay was the wait for a papal dispensation because James’ great-grandmother was Joan Beaufort, sister of John Beaufort, who was the great-grandfather of Margaret Tudor. That made James IV and Margaret Tudor fourth cousins, which was within the prohibited degree. Patrick Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, acted as a proxy for James IV of Scotland for his betrothal to Margaret Tudor at Richmond in January 1502 before the couple was married in person.

James was dashing, accomplished, highly intelligent and interested in everything, James IV of Scots enjoyed himself with mistresses while manoeuvring to secure a politically useful bride, so the marriage was not just an "English thing".

Our King was 30, his bride was what has been described as "a dumpy 13 year old".

I'll dip into the "newspaper" of the day in Grafton's chronicle the following was written....

"Thus this fair lady was conveyed with a great company of lords, ladies, knights, esquires and gentlemen until she came to Berwick and from there to a village called Lambton Kirk in Scotland where the king with the flower of Scotland was ready to receive her, to whom the earl of Northumberland according to his commission delivered her." he went on "Then this lady was taken to the town of Edinburgh, and there the day after King James IV in the presence of all his nobility married the said princess, and feasted the English lords, and showed them jousts and other pastimes, very honourably, after the fashion of this rude country. When all things were done and finished according to their commission the earl of Surrey with all the English lords and ladies returned to their country, giving more praise to the manhood than to the good manner and nature of Scotland."

Not exactly flattering words!

The wedding finally took place for real (after several proxy marriages) on 8 August, 1503 at Holyrood House in Edinburgh. Margaret was officially crowned Queen in March 1504. The Scottish poet William Dunbar wrote several poems to Margaret around this time, including “The Thistle and the Rose”, “To Princess Margaret on her Arrival at Holyrood”

Now fayre, fayrest of every fayre,

Princes most plesant and preclare,

The lustyest one alyve that byne,

Welcum of Scotlond to be Quene!

Margaret was apparently homesick and not happy in her early days in Scotland, but the couple settled down to married life, there first child, James was born four years later, he died within the year, their second, a daughter fared little better she never survived a day. In 1309 another son only lived to be nine months old, such was the difficulties of trying to produce and heir, it's a wonder the human race survived, what with mortality rates being so high in the nobility, one only wonders how high it would have been for the ordinary citizen of Scotland?

Meanwhile Margarets father passed away and Henry VIII took the throne.

Margaret’s next child was born on April 11, 1512 at Linlithgow and named James. He survived childhood and was to become King James V and father of Mary.

As for "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" it lasted around 10 years, in the first few years of Henry VIII’s reign, the relations with Scotland became strained, and it eventually erupt in 1513, when Henry VIII went to France to wage war, this invoked The Auld Alliance and James IV, Henry VIII's brother-in-law marched his army into England only to be disastrously cut down on September 9th at Flodden Field, with too many of our Scottish Knights to count. The Queen gave birth to another son, Alexander the following April, but things would turn sour for her.

Margaret, then regent, remarried into the powerful Douglas family, the Scottish Parliament then removed her as Regent a pregnant Margaret fled Scotland in 1515, her sons were taken from her before she left. She was given lodgings by her brother at Harbottle Castle, where she gave birth to daughter, Margaret Douglas, who herself played a big part in Scottish history, becoming mother to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.

That wasn't the last we had seen of Margaret Tudor though, she returned to Scotland with a promise of safe conduct in 1517 but her marriage to Douglas was a disaster, he had taken a mistress while she was in England.

In 1524 Margaret, in alliance with the Earl of Arran, overthrew Albany's regency and her son was invested with his full royal authority. James V was still only 12, so Margaret was finally able to guide her son's government, but only for a short time since her husband, Archibald Douglas, came back on the scene and took control of the King and the government from 1525 to 1528. This would all come back to bite the ambitious Douglas family in the bum

In March 1527, Margaret was finally able to attain an annulment of her marriage to Angus from Pope Clement VII and by the next April she had married Henry Stewart, who had previously been her treasurer. Margaret's second husband then arrested her third husband on the grounds that he had married the Queen without approval. The situation was improved when James V was able to proclaim his majority as king (he was 16 at the time) and remove Angus and his family from power. James created his new stepfather Lord Methven and the Scottish parliament proclaimed Angus and his followers traitors. However, Angus had escaped to England and remained there until after James V's death.

Margaret's relationship with her son was relatively good, although she pushed for closer relations with England, where James preferred an alliance with France. In this, James won out and was married to Princess Madeleine, daughter of the King of France, in January 1537. The marriage did not last long because Madeleine died in July and was buried at Holyrood Abbey. After his first wife's death, James sought another bride from France, this time taking Marie de Guise (eldest child of the Claude, Duc de Guise) as a bride. By this same time, Margaret's own marriage had followed a path similar to her second one when Methven took a mistress and lived off his wife's money.

On October 18th 1541, Margaret Tudor died in Methven Castl. probably from a stroke. Margaret was buried at the Carthusian Abbey of St. John’s in Perth. Although Margaret's heirs were left out of the succession by Henry VIII and Edward VI, ultimately it would be Margaret's great-grandson James VI who would become king after the death of Elizabeth.

#scotland#scottish#england#english#the stewarts#the tudors#the thistle and the rose#history#marriage#peace tr

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journey to Bosworth: Participants and their motives at Bosworth field: Henry Percy, the failed fence-sitter.

Hello! I wrote this piece as I had numerous sources on the War of the Roses at hand thanks to my master. I hope folks who enjoy reading about this period would like it!

At Bosworth Field, August 22th 1485, the last Plantagenet king was killed. Richard III died on a last, desperate charge against a rival whom little foresaw as a viable contender for the throne. With him died the longest ruling dynasty in England's history. Except for this symbolical conclusion, Bosworth field's importance was magnified by Tudor propaganda, as an ultimate fight between good and evil and the end of the Middle Ages. It forgets that the battle lasted at best for an afternoon and was quite ill-documented, to the point where the battlefield was inaccurately identified at first. It is thus fair to say that Bosworth mostly holds importance in retrospect. If Henry Tudor had been defeated or killed before he could uproot his new dynasty, Bosworth would have been seen as one of the many sterile struggles for the Crown in XVth century England.

Today, I would like to share some informations about one of the major participants of this battle. One whom, not by his actions but by his inactions, changed the outcome of this day.

The powerful Henry Percy, the fourth earl of Northumberland. Henry came from a family traditionally considered as one of the major power players in Northern England. The famous saying: ‘the North knew no Prince but a Percy’ was quite self-eloquent, even if exaggerated. During the 1400s, the Percies opposition to Henry IV almost led to the king's destruction at the battle of Shrewsbury. After their attainder, Henry Percy’s grandfather (another Henry) did reconcile with the House of Lancaster but lost many lands and prestige. Even after those losses, the Earl of Northumberland was one of the major supporters of the House of Lancaster in the War of the Roses, their current Earl dying at Towton against the newly crowned Edward IV.

Edward IV had counted on their rival: the junior line of the Nevilles, which was one of the mightiest Houses in English history. Through marriages, alliances, and shady maneuverings, the Kingmaker Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, and Salisbury hold the inheritance of houses Montagu, Beauchamp, Despencer, and also the bulk of the Neville inheritance in the North, against the senior line who retained the title of Earl of Westmoreland and less important holdings.

Richard Neville and his family were quite ambitious, and as the leading supporter of the burgeoning House of York, they were lavishly endowed by the new king. Richard’s brother took in 1464 all the lands of the House of Percy, with the title of Earl of Northumberland, thanks to his service in the North. However, for Henry Percy’s fortune, Edward IV and the Nevilles had a falling out, as it often happens between king and Kingmaker. Richard Neville opposed Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville, from a modest, noble family, and his policies in favor of Burgundy. Likely worried about the rising star of the Nevilles in the North, Edward IV decided to clip their wings by giving back his titles and lands to Henry Percy, which would be formalized solemnly in the 1472 Parlement.

This decision was a disaster for Edward IV, as the loyal John Neville, unhappy with the compensations, decided to join his brother in his attempt to restore the House of Lancaster. As for the new grantee, he seemed to have become a cautious man, conscious of his predecessors' tragic end, and seemingly determined not to reproduce their mistakes.

It can be seen in the events of 1470-1471. Henry Percy didn’t help the Lancastrians in their effort to resurrect their rule on England in 1470. He also didn’t try to stop Edward IV when he landed in Yorkshire the following year while he was on the first line.

After the Yorkist victories of Barnet and Tewkesbury, the civil war was over. The destruction of the lines of Lancaster and restored peace in England. Henry Percy, confirmed in his lands and titles despite his fence-sitting, was prepared to restore the House of Percy to its rightful place after a decade of unrest and absenteeism.

The conditions were seemingly favorable to prepare an extended Percy hegemony in the North. Hadn’t the Kingmaker died and his holdings taken back by the Crown? Wasn’t the Earl of Westmoreland mad and the Cliffords at odds with the king? Percy seemed in favorable conditions to fill a region partially poked power vacuums. It was without another newcomer: Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester. The twenty-year-old duke was originally granted extensive estates and offices in Wales, the Welsh Borders, and East Anglia. However, the Nevilles' demise gave Richard a unique opportunity to replace them. From 1471 onward, Richard secured from his brother the bulk of Neville’s northern estates. By his marriage to Anne Neville, the youngest daughter of the Kingmaker, he could pretend to be the heir of the deceased Earl and not someone put on by royal authority. Richard constantly tried to accrue his northern estates at the expense of other regions. By the demise of his brother Clarence in 1478, he trades with Edward IV several northern holdings, including the Honour of Richmond, for other estates he had in the south. By the many offices he was appointed and the leadership of the Council of the North, Gloucester was the natural hegemon in the North. Henry Percy became one of his retainers and obtained the preservation of his traditional hegemony in Northumberland.

Was Henry Percy happy with the arrangement? He did follow the Duke of Gloucester in his main activities as local ruler of the North, especially the war against Scotland in the early 1480s. Henry Percy also supported Gloucester’s usurpation of the throne in 1483, although it’s quite possible that he wanted to get rid of his influence in the North for good. If so, he was sorely misplaced, as the Council of the North continued with his heir, the Prince of Wales and after the Earl of Lincoln. Worse, the Duke of Gloucester now had the full power of the Crown for his patronage. His brief reign was marked by extensive and heavy-handed trade in favor of northerners. The Earl of Northumberland did profit from this situation, as he was granted the reversal of the attainders of his ancestors during Henry IV’s reign and the lordship of Holderness.

But Richard III also started to infringe on Henry Percy’s indenture of retainers. He needed loyal service in times of treason, and the new king seemed to have placed enormous trust in northerners. Richard III began to employ and endow many Percy retainers. This was a threat for Percy’s base of power, as he couldn’t match a king’s patronage. Even the death of Anne Neville and his only son Edward of Middleham during his reign didn’t seem to waver northern loyalty toward Richard. His ‘good lordship’ and the lavish grants he gave to his retainers made him simply paramount in northern politics.

Henry Percy was threatened on the very basis of his power. His retainers were becoming broadly too loyal to Richard III to allow the Earl to join the Tudor cause, even if he willed so. His ‘good lordship’ necessitated him to represent his affinity, and his numerous retainers wanted to keep Richard III on the throne. Henry Percy was on the verge of becoming a non-entity, with no true autonomy as his servants would become Richard’s.

There is evidence that Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, tried to sabotage Richard III’s war effort. He showed up with only 3,000 men at Leicester for the confrontation with the rebels. It seems that the Earl deliberately forgot to recruit men in several key northern areas, even though Richard III had given him the commission of arrays to do so in Yorkshire. He notably didn’t try to recruit soldiers from York, who upon their own authorities would raise eighty men to join Richard III at Bosworth. They would arrive too late. Richard III knew Northumberland’s guile as he had received messengers from York. Perhaps Northumberland brought, as a justification, the fact that the city was enduring an epidemy of plague. Or maybe Richard III was overconfident upon his forces and eager to show by chivalric prowess his right to retain the Crown. Those petty moves didn’t interest him in front of the upcoming battle, which was God’s judgment. In any case, Richard III put him in charge of the rearguard, but close enough to the immediate action.

In the heat of the battle, Henry Percy refused to support Norfolk against the assaults of the Earl of Oxford. This decision had a fateful consequence, as it prompted Richard to led a personal charge against Henry Tudor in the hope he would slain him. After Richard’s demise, Henry Percy surrendered to the triumphant Tudor king. He was briefly jailed by Henry VII, who kept him as his lieutenant in the North in place of the Council. Northumberland wouldn’t be more loyal to him, as he didn’t genuinely commit force during Lambert Simmel’s rebellion in 1487. Neutrality, once again, might have been the best thing he has to offer to Henry VII, as the North was sympathetic to the yorkists and Richard III’s heirs. However, Northern hatred against his behavior was ostensibly shown in the uprising of 1488. Initially a popular revolt against taxes, the rebels would have Henry Percy as their sole victim. The Earl, who was murdered in front of his retainers during a meeting with the rebels. His retainers simply didn’t defended him. Thus ended the fourth earl of Northumberland, abandoned by his retainers the same way he forsake his sovereigns.

Sources:

Chris Given-Wilson, Paul Brand, Seymour Phillips, Mark Ormrod, Geoffrey Martin, Anne Curry and Rosemary Horrox. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge, 2005. British History Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/parliament-rolls-medieval.

Great Britain. Public Record Office. (1891). Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public record office. London: H.M.S.O.. HathiTrust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009029274.

Hicks, Michael. Bastard Feudalism. Longman Group, 1995.

Hicks, Michael. Edward IV. London; Oxford University Press, 2004.

Hicks, Michael. The Fithteenth Century, Volume II: Revolution and Consumption in Late Medieval England. The Boydell Press, 2001.

Hicks, Michael. Richard III and his rivals: Magnates and their motives in the War of the Roses. The Hambledon Press, 1991.

Hicks, Michael. The Political Culture in the Fifteenth Century. London, Routeldge, 2002.

Hicks, Michael. The War of the Roses. Yale University Press, 2010.

Lander, J.R. “Attainder and Forfeitures, 1453 to 1509”. The Historical Journal Vol. 4, No. 2 (1961), pp. 119-151.

Kendall, Paul Murray. Richard III. Traduction d’Eric Diacon. Fayard, 1979

Kendall, Paul Murray. Warwick, le Faiseur de Rois. Traduction d’Eric Diacon. Fayard, 1981.

Wolffe, Bertam Percy. The royal demesne in English History, Alden Press, Oxford, 1970.

#battle of bosworth#henry percy#fourth earl of Northumberland#suffering from success#richard iii#Journey to Bosworth

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRITISH CASTLES

Britain is filled with castles, once-glorious fortresses that were the homes of kings and lords. Since the days of yore in which they served as the center of a local community’s life, many have fallen into ruin, and others have become far too expensive to main. As such, they’ve been given over to charities and trusts that have opened them to the public. A relatively small number of castles, however, remain in the hands of the aristocracy and still serve as the seats or lords and ladies and are open to visitors.

ALNWICK CASTLE

Alnwick Castle has been home to the Percy family for over 700 years and remains a family home today for the 12th Duke and Duchess and their four children. The Percys, arriving from France with William the Conqueror in the 11th century, have been embroiled in the politics of the often bloody history of Britain. The Castle’s rich history is brimming with drama, intrigue and extraordinary people; from a gunpowder plotter and visionary collectors, to decadent hosts and medieval England’s most celebrated knight: Harry Hotspur.

In 1309, Henry Percy, great-great grandfather of Hotspur, purchased a typical Norman-style castle of motte and bailey form. In the following 40 years he and his son converted it into a mighty border fortress. They added towers and guerites around its curtain walls with a strong gatehouse at the entrance and a concealed postern gate to the rear. The gateway to the keep was strengthened with the addition of two massive octagonal towers. Archival evidence, however, shows that building work was carried out in the late 15th century and that the 4th Earl’s badge was placed over the entrance in 1475.

The 4th Earl had alterations and repairs carried out to adapt the Barbican to the latest tactics of warfare. The town’s defences were also being strengthened during this period, following devastating raids by the Scots in the first half of the 15th century.

The Barbican had numerous purposes. It stood as the first line of defence at the castle’s most vulnerable spot. Up until the 18th century this was the only entrance to the castle, apart from the concealed postern gate.

youtube

It was in the 1750s that it became the main residence for the Duke of Northumberland who commissioned Robert Adam to make the castle more habitable not to mention fashionable. In the Nineteenth Century Salvin was appointed to create more modifications – the fourth duke liked his castle with a romantic tinge. It remains the second largest inhabited castle in England and reflects a Gothic Italian styles admired by the family at that time.

visitnorthumberland

While the Percy family still lives here, parts of the castle are open to visitors, and the castle has been used extensively in films from Prince Valiant to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. It has also taken starring roles in a number of film and television productions, featuring as the magnificent Brancaster Castle in Downton Abbey.

BAMBURGH CASTLE

At the end of the ice age the people who inhabited the region were hunter-gatherers who lived nomadic lives traveling around in small groups and evidence of the tools they used has been found in Bamburgh. By the Neolithic period people started to farm the area and stone tools have been found at Bamburgh & Glorurum. During the Bronze age the landscape had become more settled with increased deforestation and the creation of field systems.By around 550 AD the Anglo Saxons from the continent expanded northwards and control passed to the Anglican King, Ida.

The British territorial name of Bryneich (Bernicia), was retained by Ida, as was the British name of the stronghold at Bamburgh, Din Guaroy, from where Ida and his successors ruled. Later it became Bebbanburg after the Saxon Queen Bebba and finally Bamburgh. Aidan came to Bamburgh from the monastery of Iona in 635, at the request of King Oswald who sent for a monk to preach the Christian faith in Northumbria.

Aidan immediately built a wooden church, somewhere in the vicinity of St Aidans Church. He died in 651, resting against an outer buttress of the church (this timber buttress survived two subsequent fires, and tradition says that it is now incorporated in the roof above the font). From this place, Christianity spread throughout Northern England.

bamburgcastle

flickr

visitnorthumberland

A medieval village developed around the foot of the Castle, and a Dominican Friary (dating from 1256) was built in what is now the western part of the village. Among the friars charitable activities was a lepers hospital, but this closed in the 14th century and its site remains uncertain. The Friary acquired extensive lands, which flourished until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1545 when all their property was seized by Henry VIII and sold to Sir John Forster for the princely sum of £664.

Under the ownership of the Forster family (who lived in Bamburgh Hall) the castle gradually fell into disrepair and became little more than a ruin, but in the 18th century it came under the ownership of Lord Nathaniel Crewe, Bishop of Durham. He began the long process of restoration, but soon died and work was continued by the charitable trust that bears his name. The Lord Crewe Trust rebuilt much of the village and created a ‘welfare state’ for the inhabitants which provided a school, a dispensary, a hospital, a coastguard service, a lifeboat and a welfare centre for the shipwrecked mariners. By the 1880’s the trust was in difficulties and in 1894 sold the Castle, village and estate lands to Lord Armstrong of Cragside, who devoted much of his later life to the restoration of the castle. While not possessing any titles, the Armstrong family still owns and lives in the castle. The family has it opened to the public, and in addition to tours, the castle plays host to weddings, holiday events, and overnight guests.

BELVOIR CASTLE

The land at Belvoir was a gift from William the Conqueror to the family’s first recorded ancestor Robert de Todeni. One of his Norman barons, Robert de Todeni was William’s Standard Bearer in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Todeni began building the first Castle here in 1067. It was built to a typically Norman motte-and-bailey design. With a timber framed fortress in an enclosed courtyard, it took full advantage of the site’s defensive position high up on the ridge. Todeni also founded a priory at the foot of the Castle, where he was buried on his death in 1088.

By 1464, the Wars of the Roses had taken their toll on the first castle, and it was more or less in ruins.

Belvoir rose again some 60 years later with the construction of the second Castle to a medieval design for Sir Thomas Manners. His grandfather Sir Robert Manners had married into the family, but Sir Thomas was the first Manners to live at Belvoir. The second Castle was a much nobler structure with a central courtyard, parts of which can still be recognized today. In 1649, the second Castle was destroyed by Parliamentarians after Royalists had seized it during the Civil War (1642-1651).

The third Castle, completed in 1668 to a design by John Webb – a pupil of Inigo Jones – was created for John the 8th Earl under the instruction of his wife, Frances the Countess. She insisted on rebuilding it as a palatial country house without any resemblance to a castle.

britain´sfinest

vanityfair

Elizabeth, the 5th Duchess of Rutland was the young, dynamic 18-year-old bride of John Henry, 5th Duke of Rutland. She was the daughter of the 5th Earl and Countess of Carlisle. As a child she had been fascinated by her father’s lavish and fashionable improvements at their family home – Castle Howard in Yorkshire.

Sharing her father’s passion for architecture and design, the young Duchess could see the potential after arriving at the horribly run-down Belvoir Castle in 1799. Abandoning Capability Brown’s plans to rebuild the Castle, she chose James Wyatt – the leading Gothic romantic architect – to create her dream home.

Today, Belvoir Castle is said by experts to be one of the finest examples of Regency architecture in the country.

On an interesting note, while many of the Earls have lived there, they have also been buried there in a mausoleum on the grounds. And like Alnwick, it has been featured in a number of films and television shows as well as being open to the public.

ARUNDEL CASTLE

The oldest feature is the motte, an artificial mound, over 100 feet high from the dry moat, and constructed in 1068: followed by the gatehouse in 1070. Under his will, King Henry I (1068-1135) settled the Castle and lands in dower on his second wife, Adeliza of Louvain. Three years after his death she married William d'Albini II, who built the stone shell keep on the motte. King Henry II (1133-89), who built much of the oldest part of the stone Castle, in 1155 confirmed William d'Albini II as Earl of Arundel, with the Honour and Castle of Arundel.

Apart from the occasional reversion to the Crown, Arundel Castle has descended directly from 1138 to the present day, carried by female heiresses from the d'Albinis to the Fitzalans in the 13th century and then from the Fitzalans to the Howards in the 16th century and it has been the seat of the Dukes of Norfolk and their ancestors for over 850 years. From the 15th to the 17th centuries the Howards were at the forefront of English history, from the Wars of the Roses, through the Tudor period to the Civil War.

experiencedtraveller

The Castle houses a fascinating collection of fine furniture dating from the 16th century, tapestries, clocks, and portraits by Van Dyck, Gainsborough, Mytens, Lawrence, Reynolds, Canaletto and others. Personal possessions of Mary, Queen of Scots and a selection of historical, religious and heraldic items from the Duke of Norfolk’s collection are also on display.

britainmagazine

During the Civil War (1642-45), the Castle was badly damaged when it was twice besieged, first by Royalists who took control, then by Cromwell’s Parliamentarian force led by William Waller. Nothing was done to rectify the damage until about 1718 when Thomas, the 8th Duke of Norfolk (1683-1732) carried out some repairs. Charles Howard, the 11th Duke (1746-1815), known to posterity as the 'Drunken Duke’ and friend of the Prince Regent subsequently carried out further restoration.

Queen Victoria (1819-1901) came from Osborne House with her husband, Prince Albert, for three days in 1846, for which the bedroom and library furniture were specially commissioned and made by a leading London furniture designer. Her portrait by William Fowler was also specially commissioned by the 13th Duke in 1843.

The building we see now owes much to Henry, 15th Duke of Norfolk (1847-1917) and the restoration project was completed in 1900. It was one of the first English country houses to be fitted with electric light, integral fire fighting equipment, service lifts and central heating. The gravity fed domestic water supply also supplied the town.

LUDLOW CASTLE

The construction of the Ludlow Castle started around 1085, with many later additions in the following two centuries. It is one of the most interesting castles in the Marches, in a dominant and imposing position high above the river Teme. It features examples of architecture from the Norman, Medieval and Tudor periods. The building of the castle led to the development of Ludlow itself, at first grouped around the castle; the impressive ruins of the castle occupy the oldest part of Ludlow.

In the late 12th and early 13th centuries the castle was extended, and part of the grid pattern of streets immediately to the south was obscured by the enlarged outer bailey. From 1233 onwards the town walls were constructed; Ludlow Castle stood within the circuit of the walls.

businessline

thecastleofwales

Ludlow Castle has played a key role in some turbulent events in English history. One of its 14th-century owners, Roger Mortimer, helped his mistress Queen Isabella, in the overthrow of her husband King Edward II. In 1473, the Prince of Wales and his brother were held here before their mysterious death in the Tower of London. In 1502 Prince Arthur, Henry VII’s son and heir to the throne, died at Ludlow. Edward IV founded the Council of the Marches of Wales in the late 15th century, its headquarters were in Ludlow Castle. The Council administered most of Wales and Shropshire and the adjacent English counties. The Council’s courts were very active, and the castle and Ludlow were full of lawyers, clerks and royal messengers.

The Council of the Marches ceased to exist in 1689, and after this the castle gradually fell in to disuse and disrepair, although Ludlow itself was still on a wave of prosperity.

While the castle is owned by John Herbert, the 8th Earl of Powis, it is managed by the Powis Estate and sees over 100,000 visitors a year.

https://www.anglotopia.net/british-history/the-fiver-five-british-castles- & https://www.arundelcastle.org/castle-history/ &https://www.belvoircastle.com/about-us/history/ &https://www.alnwickcastle.com/explore/the-history

Wonderful! Thank you😊❤️❤️❤️❤️

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Singing History.

Research Assistant Hailey Bachrach looks at then importance of songs in the Henriad.

If you’ve seen our production of Hotspur (aka Henry IV Part One), you’ll have noticed—or soon will notice, if you haven’t made it yet—that it begins with a song. This song was arranged by our fantastic ensemble composer Tayo Akinbode, and adapted by director Federay Holmes from several famous ballads of Shakespeare’s time. Two in particular had an influence on the opening song: a Scottish ballad called “The Battle of Otterburn,” and an English ballad known by various titles, including “The Ballad of Chevy Chase” or “The Hunt of the Cheviot.”

This second ballad was one of the most popular songs of Shakespeare’s day. Supposedly, playwright Ben Jonson said that he would rather have written it than the entirety of his works. It tells the story of a fictional encounter between the Scottish Earl of Douglas and the English Percy, Earl of Northumberland that ends in both of their deaths.

Word is come to Edinburgh,

To Jamie the Scottish King,

Earl Douglas, lieutenant of the Marches,

Lay slain Cheviot within.

His hands the King did weal and wring,

Said, ‘Alas! and woe is me!

Such another captain Scotland within

I’ faith shall never be!’

Word is come to lovely London

To the fourth Harry, our King,

Lord Percy, lieutenant of the Marches,

Lay slain Cheviot within.

‘God have mercy on his soul,’ said King Harry,

‘Good Lord, if thy will it be!

I’ve a hundred captains in England,’ he said,

‘As good as ever was he:

But Percy, an I brook my life,

Thy death well quit shall be.’

And as our King made his avow

Like a noble prince of renown,

For Percy he did it well perform

After, on Homble-down;

Where six-and-thirty Scottish knights

On a day were beaten down;

Glendale glitter’d on their armour bright

Over castle, tower and town.

“Otterburn” is the Scottish version of roughly the same story, though it’s much more rooted in actual facts—probably because, historically, the Scots won and Percy was captured, much to the family’s disgrace.

It fell about the Lammastide,

When moor-men win their hay,

The doughty Douglas bound him to ride

Into England, to drive a prey.

And he has burned the dales of Tyne,

And part of Bamburghshire,

And three good towers on Reidswire Fells,

He left them all on fire.

Then he's marched on down to Newcastle,

“Whose house is this so fine?”

It's up spoke proud Lord Percy,

“I tell you this castle is mine!”

“If you're the lord of this fine castle,

Well it pleases me.

For, ere I crossed the Border fells,

The one of us shall die.”

It’s hard to think of an exact modern equivalent to Renaissance ballads. The obvious comparison is hit pop songs, the ones that play constantly on the radio in every shop and that everyone seems to know, but even that doesn’t quite capture the communal, oral culture that ballads were part of. They were designed not just to be listened to, but to for everyone to sing. New lyrics were produced to recycled tunes to make it easy for anyone to learn them, and the lyrics conveyed not only historical or legendary or fictional material, but current events and recent news. We see this in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, when the thief Autolycus disguises himself as a peddler and sells the Bohemian shepherdesses ballads. ‘I love a ballad in print,’ the shepherdess Mopsa gushes, ‘for then we are sure they are true’ (4.4.296).

The Percys and the Douglas are prominent families in Hotspur, and the play begins with the very battle that “Chevy Chase” references in its final stanzas: the Battle of Homble-down, or Holmedon, where Harry ‘Hotspur’ Percy decimated a Scottish force led by Douglas. Neither song should be seen as a direct prequel to Henry IV Part One—especially “Chevy Chase,” where Percy and Douglas wind up dead. But Shakespeare’s evocation of these familiar names and battles right in the first scene could help audience members who may not know much about history understand the relationships between the two border families, and the political stakes and legacies of the battles being discussed. Ballads were an important way for people who couldn’t access formal histories to learn about their nation’s past, and playwrights knew it.

We wanted to try and let our audiences experience the same kind of familiarity that Renaissance audiences would have had with some of the leading figures of the play they’re about to watch. Watching Hotspur with the military adventures of the daring Percy and the bold Douglas fresh in your mind is a very different experience than just reading a summary of the reign of Henry IV, or even having watched Richard II. It redirects your focus and sets up a series of expectations about plot and character, some of which the play meets, and some of which it intentionally subverts. While it’s not quite the kind of pre-show background information that we’re used to getting for one of Shakespeare’s history plays, it’s the experience that many of his original audience members would have had.

Further Reading:

“The Heyday of the English Broadside Ballad,” by Erik Nebecker for the Early English Broadside Ballad Archive.

Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodelian Libraries.

Find out more about Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 and Henry V.

Photography by Tristram Kenton

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day In History . 25 May 1553 . Lady Jane Grey married Lord Guildford Dudley . . ◼ Lady Jane acted as chief mourner at Catherine Parr's funeral; Thomas Seymour showed continued interest to keep her in his household, & she returned there for about two months before he was arrested at the end of 1548. Seymour's brother, the Lord Protector, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, felt threatened by Thomas' popularity with the young King Edward VI. Among other things, Thomas Seymour was charged with proposing Jane as a bride for the king. . ◼ In the course of Thomas Seymour's following attainder & execution, Jane's father was lucky to stay largely out of trouble. After his fourth interrogation by the King's Council, he proposed his daughter Jane as a bride for the Protector's eldest son, Lord Hertford. Nothing came of this, however, & Jane was not engaged until the spring of 1553, her bridegroom being Lord Guildford Dudley, a younger son of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. The duke was then the most powerful man in the country. . 👑 On 25 May 1553, the couple were married at Durham House in a triple wedding, in which Jane's sister Catherine was matched with the heir of the Earl of Pembroke, Lord Herbert, & another Katherine, Lord Guildford's sister, with Henry Hastings, the Earl of Huntingdon's heir. . ◼ Lady Jane Grey (c. 1537 – 12 February 1554), known also as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) & as "the Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman & de facto Queen of England & Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553. . ◼ She was the great-granddaughter of Henry VII through his younger daughter, Mary Tudor, Jane was a first cousin, once removed, of Edward VI, King of England and Ireland from 1547-1554. . . . #onthisdayinhistory #thisdayinhistory #theyear1553 #d25may #History #JaneGrey #Lady #LadyJaneGrey #LadyJaneDudley #TheNineDaysQueen #EnglishMonarchy #Heritage #Protestant #Royalty #HouseofTudor #Royalhistory #Heritage #Historyfacts #England #Tudor #Tudors #Monarchy #Royalwedding #Royalweddings #Ladyjane #Historians #Historic #onthisday #Britishmonarchy (at United Kingdom) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bx4__B_g6sK/?igshid=m5wrsr7ogvfy

#onthisdayinhistory#thisdayinhistory#theyear1553#d25may#history#janegrey#lady#ladyjanegrey#ladyjanedudley#theninedaysqueen#englishmonarchy#heritage#protestant#royalty#houseoftudor#royalhistory#historyfacts#england#tudor#tudors#monarchy#royalwedding#royalweddings#ladyjane#historians#historic#onthisday#britishmonarchy

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve just watched a short documentary on the death of Lady Amy Dudley, wife of Robert Dudley, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth 1. It seems sort of old and I was wondering if anyone has solved the murder or if you had any ideas on what happened? The options in the documentary are Lord Cecil had her killed to create scandal, Amy was depressed and committed suicide, or Lord Dudley or the Queen had her killed so they could marry. But she never wed so that doesn’t seem likely? I’m sorry to bother you.

You’re not a bother; I would be a pretty silly person if I left my inbox open and then resented getting any messages. (This got long; more under the cut)

Amy Robsart was born on June 7, 1532, the only child and heiress of Sir John Robsart, a well-to-do country gentleman in Norfolk. Amy probably met her future husband, Robert Dudley, in 1549, about a year before the two of them wed. Nearly the exactly same age as Amy - he was a few weeks younger - Robert Dudley was the fifth (but fourth-surviving) son of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick and (after 1551) Duke of Northumberland, the leader of Edward VI’s regency following the fall from power of the boy-king’s uncle Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. John Dudley was an ambitious man - Robert’s next-youngest brother, Guildford, married Lady Jane Grey, eldest granddaughter of Henry VIII’s sister Mary - and while Amy Robsart was not a fantastic catch, she still allowed Dudley to extend his influence in Norfolk. More to the point, the marriage of Amy and Robert appears to have been a real love match: William Cecil, a great enemy of Robert Dudley, later sniffed that theirs was a “carnal marriage”, made because the two young people had fallen for one another rather than reasons of state. The two married on June 4, 1550, both just shy of their 18th birthdays.

Unfortunately, while the marriage might have begun happily, political shifts would ensure it did not end that way. In 1553, the young Edward VI died, and a crisis of succession emerged: by the terms of Henry VIII’s will, his heir was his eldest half-sister, Mary, but by the terms of Edward’s “My Device for the Succession”, the next ruler of England was to be “the Lady Jane [Grey]”, followed by her “heirs male”. Northumberland, as Jane’s father-in-law, was naturally supportive of her claim, and Robert followed his father, declaring Jane queen in Norfolk. Just the day after his proclamation, though, on July 19, 1553, Queen Jane was deposed and Mary proclaimed Queen of England in London. Robert was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London, and sentenced to death; his imprisonment continued until October 1554, though during that time Lady Amy was allowed to visit and “tarry with him”, which she did. Both Robert’s father and brother Guildford were executed, and while Robert was released and eventually pardoned, he emerged short of money, relying on his and his wife’s relatives to help them out financially (though Robert compounded the problem by running up debts of his own). In 1558, the couple were looking for a home of their own in Norfolk (since Amy’s father’s ancestral manor was uninhabitable), but their plans were immediately halted by the death of Queen Mary in November of that year and the ascension of Henry VIII’s younger daughter, Elizabeth.

On face, it might have seemed that Robert and Amy’s luck had turned with the accession of Elizabeth. She and Robert had been childhood friends: they were close in age (Elizabeth was a little more than a year younger), he had been a companion of her brother Edward, and the two had shared a tutor, Roger Ascham. They had also both been imprisoned by Mary early in her reign - he for the Jane Grey affair, she for a supposed connection to Wyatt’s Rebellion. Soon after she became queen, Elizabeth named her old friend Master of the Horse, a position of great importance in the sovereign’s household - and, critically, a position which required Robert to be on constant attendance to the Queen.

Within six months of the appointment, though, courtiers and diplomats were speculating that the relationship between the Queen and Lord Robert was more than just friendly - that, in fact, the Queen had fallen in love with Dudley and was looking to marry him. The Spanish envoy reported to his master, Philip II, that “Lord Robert has come so much into favor that he does whatever he likes with affairs and it is even said that her majesty visits him in his chamber day and night”, and that “the Queen is only waiting for her [i.e. Amy Dudley] to die to marry Lord Robert”. The Duke of Norfolk was reported to have promised that if Robert Dudley did not abandon his scheme to marry Elizabeth, the Duke would ensure that “he would not die in his bed” - that is, that Robert Dudley would be murdered, since in the words of the Spanish ambassador, the Bishop of Aquila, to Philip II “the Duke and the rest of them cannot put up with his being king”. In November of that year, the Bishop further wrote that the Queen’s plan with her numerous foreign suitors was to “[keep] Lord Robert’s enemies and the country engaged with words until this wicked deed of killing his wife is consummated”.

One can only imagine how Amy Dudley was feeling by this point. In December 1559, Amy moved into Cumnor Place, a house rented by a Dudley family friend, Sir Anthony Forster, where she kept a household of approximately 10 servants; in addition to Sir Anthony, his wife, and Lady Amy, the house hosted two of Sir Anthony’s relatives, Mrs. Odingsells and Mrs. Owen. In spring 1559, the Spanish ambassador had written to Philip II that Lady Amy had “a malady in her breast”, most likely breast cancer, and in May of the same year the Venetian ambassador wrote that Amy had “been ailing for some time”. Her husband’s last recorded visit to her (while she was staying at a relative’s home) occurred in Easter 1559, and after she traveled to London in June 1559 there is no direct record that she ever saw her husband again (though she might have once in late 1559, when Robert may have visited Sir Anthony for the christening of one of the latter’s children). While Robert made plans to visit in June 1560, the trip never materialized; Robert’s role required him to stay with the queen at court, and according to court gossip he “was commanded to say that he did nothing with her, when he came to her, as seldom he did”.

Then, on September 8, 1560, Amy was found dead at the foot of the stairs of Cumnor Place. According to the report of Lord Robert’s steward and cousin, Thomas Blount, Amy had “[risen] that day very early, and commanded all her sort to go [to] the fair, and would suffer none to tarry at home”. Lady Amy was insistent that her servants attend “Our Lady’s Fair” at Abingdon, and became particularly angry that Mrs. Odingsells refused to go, because “it was no day for gentlewomen to go in, but said the morrow was much better, and then she would go” (as September 8 fell on a Sunday, which for a strict Protestant gentlewoman like Mrs. Odingsells was the Lord’s day and probably seemed a highly improper day to go to a fair). Amy then reportedly “answered and said that she might choose and go at her pleasure, but all hers should go; and was very angry”, though she later allowed that “Mrs. Owen should keep her company at dinner”. When her servants returned from the fair, however, they found Lady Amy dead.

Robert Dudley was highly distressed when he found out about his wife’s death. On the following day, September 9, he wrote a letter to Thomas Blount, asking him to “use all the devises and means you can possible for the learning of the truth” and promising that he would call a coroner and a jury of “the discreetest and [most] substantial men” to inspect the body and come to a verdict how Lady Amy died. Robert also charged cousin Thomas to “send me your true conceit and opinion of the matter, whether it happened by evil chance or by villainy”. Three days later (after receiving another urgent letter from Lord Robert), Thomas Blount wrote to Dudley that “I hear a whispering that they [i.e. the jurors] can find no presumptions of evil” and that “the more I search of it, the more free it doth appear unto me” that “only misfortune hath done it, and nothing else”. Robert Dudley also heard from a man called Smith, evidently the foreman of the jury, and related to Thomas Blount that “it doth plainly appear, he [i.e. Smith] saith, a very misfortune; still, he wrote, “my desire is that they may continue in their inquiry and examination to the uttermost, as long as they lawfully may; yea, and when these have given their verdict, though it be never so plainly found, assuredly I do wish that another substantial company of honest men might try again for the more knowledge of truth”. The coroner’s report - which was actually not rediscovered until very recently - stated plainly that Amy Dudley’s death was an accident: “Lady Dudley … being alone in a certain chamber … and intending to descend the aforesaid chamber by way of certain steps … of the aforesaid chamber there and then accidentally fell precipitously down the aforesaid steps to the very bottom of the same steps, through which the same Lady Amy there and then sustained not only two injuries at her head … but truly also, by reason of the accidental injury or of that fall and of Lady Amy’s own body weight falling down the aforesaid stairs, the same Lady Amy there and then broke her own neck”.

What do I think happened? I really, really, really doubt that she was murdered. While Dudley’s eagerness might seem evidence of his guilt - trying to cover up his part in a nefarious deed - I think instead that Dudley was genuinely concerned that he would be accused of murder. He expressed these sentiments to “Cousin Blount”, talking about “how this evil should light upon me, considering what the malicious world will bruit”. He also wrote of “the malicious talk that I know the wicked world will use, but one which is the very plain truth to be known”, which seems to indicate that Robert Dudley believed that this had happened naturally, rather than that he had murdered her. After all, Robert Dudley had good reason to fear: if it became widely known, or suspected, that he had had his wife murdered, Elizabeth might be that much less likely to marry him, not wanting to attach herself to his scandal (which was in fact what happened: while Queen Elizabeth declared that Lady Amy’s death should “neither touch his honesty nor her honour” given the coroner’s report, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton’s secretary reported that “the Queen’s Majesty looketh not so hearty and well as she did by a great deal, and surely the matter of my Lord Robert doth much perplex her”). Certainly, none of Dudley’s political enemies - and he had a number of them - ever succeeded in pinning the alleged murder on him, despite attempts to the contrary: even when the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Sussex - no friends of Dudley - tried to use John Appleyard, Lady Amy’s half-brother, to find evidence against Dudley, they failed; not only did Appleyard state that “he did take the Earl [of Leicester, i.e. Robert Dudley] to be innocent [of the murder]”, but once he received a copy of the coroner’s report, he pronounced himself satisfied by the conclusion.

I also don’t think she was murdered on the orders of William Cecil. Sure, William Cecil was one of Robert Dudley’s biggest political rivals, and definitely did not want to see Robert as King Consort - but resorting to murdering Amy Dudley to prevent this happening seems like a pretty clumsy and misguided step to take. After all, it was William Cecil who drafted a memorandum on all the advantages Elizabeth would have in marrying Archduke Charles of Austria versus all the disadvantages she would face if she chose to marry Robert Dudley. If Cecil was still this concerned about the possibility that Elizabeth would end up choosing Dudley, would he have hastened along Dudley’s wife’s death to make the marriage that much more possible? Moreover, it was not simply Dudley’s reputation that stood to be hurt by this affair; Elizabeth too, given her obvious favoritism toward Dudley, faced the real possibility of taking a hit to her reputation if she were associated with any part of Amy Dudley’s supposed murder. What I think happened was that William Cecil took advantage of a suspicious but innocent circumstance - Amy Dudley dying just as her husband seems steps away from marrying the Queen - to spread gossip about his political rival.

Ultimately, what I think happened was either an accident or suicide, or perhaps somewhere in between the two. Amy Dudley had plenty of reason to feel low: having not seen the husband she apparently still loved in months, maybe over a year, knowing that there were salacious, gossipy rumors about his closeness to the queen at court, suffering from a very painful, deadly disease that can be very difficult if not impossible to treat with modern medicine, much less Tudor remedies) - small wonder that her maid, Mrs. Picto, said “she hath heard her [i.e. Lady Amy] pray to God to deliver her from desperation”. Suicide might have seemed a step too far for a practicing Protestant like Lady Amy, as both a criminal act and a sin against God - but that’s not to say she could not have gotten to a point where her despair became too overwhelming even for her religious beliefs. Even if she was not specifically intending to commit suicide, it’s still possible - especially if she did have breast cancer - that a fall down the stairs could have resulted in her death, her bones having become weaker and more susceptible to breaking through her disease. Whether she had accidentally slipped, or was simply not being careful enough, I think Amy Dudley died more or less innocently, if no less sadly because of it - a tragic accident, unfortunately timed so as to cast doubt on her husband.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is the comprehensive timeline of each character on this blog, including real events for reference, which are denoted with an asterisk.

17th Century

1682, 26 December - Jack Rackham is born in Leeds, England.*

1687, 14 July - The Rackham family relocates to Guardalavaca, Cuba for better economy.

1688, 1 March - Anne Bonny is born in Whitechapel, London, England.

1692, 31 May - William Cormac, Selma Diyadin, and their illegitimate daughter, Anne, move to the Province of Carolina.

1696 17 December - Selma Diyadin dies.

1697 9 July - Florence Rackham dies.

1697 15 July - Janet Rackham dies.

1698 6 February - Jack Rackham escapes his father’s debt aboard the pirate ship, Red Sun.

1698 1 May - Anne Bonny gets married.

1699 17 September - Jack Rackham and Anne Bonny meet.

18th Century

1709 20 December - Jack Rackham and Anne Bonny meet Charles Vane.

1758 - Hudson Fifing is born.

1762 10 September - Hudson’s father is tried and convicted of treason and conspiracy against the Crown.

1762 3 December - Hudson’s mother disappears after going to the prison ship her husband is incarcerated in to see if he is still alive.

1765 12 August - Hudson and Diana move to New York City.

1774 4 August - Hudson begins medical school at New College in Massachusetts.

1774 23 October - Bram Edrington is born.

1775 18 April - The American Revolution begins.*

1775 22 April - Anne Bonny dies of old age.

1775 14 May - Hudson and Diana move to Dover, Delaware to avoid British forces.

1775 31 May - Hudson returns to New York City.

1780 9 August - Bram Edrington begins his classical education.

1783 3 September - The American Revolution ends.*

1783 27 September - Pavel Dimitriyevich Faradavislas is born.

1784 8 November - Madeleine Sorensen is born aboard the Regalia.

1785 30 October - Hudson Fifing is impressed by the British Navy aboard HMS Contest.

1787 10 February - Contest is intercepted and sunk by the American privateer, King’s Folly.

1787 17 June - Hudson returns stateside.

1787 15 August - Bram Edrington begins his military education.

1791 19 May - Bram Edrington begins his military career as a sergeant.

1791 19 October - Hudson Fifing dies after being swept off the deck during a maelstrom, lost at sea.

1792 25 February - Bram purchases his commission as major.

1792 25 February - Edrington’s Reign of Terror begins.

1792 3 June - William Blakeney is born.

1793 - The War of the First Coalition begins.*

1793 21 January - King Louis XVI is guillotined.*

1793 December - Edrington’s Reign of Terror ends.

1793 13 December - Pavel Faraday breaks his leg.

1794 13 July - The Frogs and the Lobsters ( The Wrong War. )

1794 2 August - Bram Edrington weds Adelaide Sybil.

1794 30 August - Adelaide Sybil becomes pregnant.

1795 11 April - Philadelphia Edrington is born.

1795 18 June - Adelaide Sybil dies.

1796 22 May - Pavel Faraday joins his father at Oxford College.

1798 - The War of the First Coalition ends.*

1798 5 November - Pavel graduates with his degree in librarianship, and begins his career in espionage with the Kremlin.

1799 - The War of the Second Coalition begins.*

19th Centrury

1800 1 June - Napoleon’s victory in Marengo.*

1801 - War of the Second Coalition ends.*

1801 11 March - Madeleine’s father abandons her, leaving her as sole lighthouse keeper.

1801 1 October - Prime Minister Henry Addington signs preliminary peace agreement.*

1802 - The Peace of Amiens begins.*

1803 - William Blakeney goes to the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth.

1803 - The Peace of Amiens ends.*

1805 - William Blakeney graduates from the Royal Naval Academy of Portsmouth.

1805 - The War of the Third Coalition begins.*

1805 27 February - William Blakeney receives orders to report to the HMS Surprise.

1805 July - Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

1806 - The War of the Fourth Coalition begins.*

1806 23 May - Bram Edrington retires from military service.

1807 - The War of the Fourth Coalition ends.*

1807 - The Peninsular War begins.*

1807 1 July - The Peace of Tisit begins.*

1807 24 July - William Blakeney recieves orders to report to the HMS Northumberland.

1808 2 July - British troops arrive in Portugal for the Peninsular War.*

1809 - The War of the Fifth Coalition begins.*

1809 16 June - Pavel Faraday is guillotined for espionage.

1809 31 October - William Blakeney passes his examination for lieutenant.

1809 6 December - William Blakeney reports to the HMS Bellona as second lieutenant under Cpt. Thomas Pullings.

1810 7 May - Philadelphia Edrington publishes her first editorial under the pseudonym “Thomas Wilson”.

1811 12 June - Philadelphia Edrington weds the Earl of Suffolk.

1812 - The War of the Sixth Coalition begins.*

1812 13 January - Bram Edrington dies of pneumonia.

1812 17 February - Philadelphia’s first child is born.

1812 June - The War of 1812 begins.*

1812 27 July - William Blakeney is promoted to first lieutenant of the HMS Bellona.

1812 7 November - William Blakeney dies of blood loss after a skirmish with the French ship, Inlassible.

1813 14 January - Napoleon gets whipped in Russia.*

1814 - The Peninsular War ends.*

1814 - The War of the Sixth Coalition ends.*

1814 19 September - Philadelphia Edrington’s second child is born.

1815 18 February - The War of 1812 ends.*

1815 1 April - The War of the Seventh Coalition ends.*

1832 31 March - Philadelphia Edrington dies from an auto - immune disorder.

1866 14 May - Madeleine Sorensen dies of old age.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prudhoe Castle Northumberland UK

Friday 14 July 2017

**************************************************************************************

Prudhoe Castle is a ruined medieval English castle situated on the south bank of the River Tyne at Prudhoe, Northumberland, England.

The castle stands on a ridge about 150 feet on the south bank of the River Tyne. It is partly enclosed by a deep moat. The ground to the north falls away steeply to the river. The castle entrance is on the south side and is flanked by a mill pond on the left and a ruined water mill on the right. The castle is entered by a barbican dating from the first half of the 14th century. The gatehouse, dating from the early 12th century, leads into the outer ward, which contains the remains of several buildings. At the north side, against the curtain wall, are the remains of the Great Hall, measuring 60 ft by 46 ft, built by the Percies when they took over the castle. At the end of the 15th century a new hall was built to the west to replace the existing one.

On the west side of the outer ward is the manor house, built in the early 19th century. At the south end of the manor house is a gateway leading into the inner ward. The main feature of the inner ward is the keep, dating from the 12th century. The keep has walls 10 feet thick. It originally consisted of two storeys beneath a double-pitched roof.

Excavations have shown that the first castle on the site was a Norman motte and bailey, built sometime in the mid 11th century. Following the Norman Conquest, the Umfraville family took over control of the castle. Robert d’Umfraville was formally granted the barony of Prudhoe by Henry I but it is likely that the Umfravilles had already been granted Prudhoe in the closing years of the 11th century. The Umfravilles initially replaced the wooden palisade with a massive rampart of clay and stones and subsequently constructed a stone curtain wall and gatehouse.

In 1173 William the Lion of Scotland invaded the North East to claim the earldom of Northumberland. The head of the Umfraville family, Odinel II, refused to support him and as a result the Scottish army tried to take Prudhoe Castle. The attempt failed as the Scots were not prepared to undertake a lengthy siege. The following year William attacked the castle again but found that Odinel had strengthened the garrison, and after a siege of just three days the Scottish army left. Following the siege, Odinel further improved the defences of the castle by adding a stone keep and a great hall.

Odinel died in 1182 and was succeeded by his son Richard. Richard became one of the barons who stood against King John, and as a result forfeited his estates to the crown. They remained forfeited until 1217, the year after King John’s death. Richard died in 1226 and was succeeded by his son, Gilbert, who was himself succeeded in 1245 by his son Gilbert. Through his mother, Gilbert II inherited the title of Earl of Angus, with vast estates in Scotland, but he continued to spend some of his time at Prudhoe. It is believed that he carried out further improvements to the castle. Gilbert took part in the fighting between Henry III of England and his barons, and in the Scottish expeditions of Edward I. He died in 1308 and was succeeded by his son, Robert D’Umfraville IV. In 1314, Robert was taken prisoner by the Scots at Bannockburn, but was soon released, though he was deprived of the earldom of Angus and of his Scottish estates. In 1316 King Edward granted Robert 700 marks to maintain a garrison of 40 men-at-arms and 80 light horsemen at Prudhoe.

In 1381 the last of the line, Gilbert III, died without issue and his widow married Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. On her death in 1398, the castle passed to the Percy family.

The Percies added a new great hall to the castle shortly after they took possession of it. Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland fought against Henry IV and took part in the Battle of Shrewsbury, for which act he was attainted and his estates, including Prudhoe, were forfeited to the Crown in 1405. That same year it was granted to the future Duke of Bedford, (a son of Henry IV) and stayed in his hands until his death in 1435, whereupon it reverted to the Crown.

The Percies regained ownership of the Prudhoe estates in 1440, after a prolonged legal battle. However, Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland fought on the Lancastrian side in the Wars of the Roses and was killed at the Battle of Towton in 1461. In 1462 Edward IV granted Prudhoe to his younger brother George, Duke of Clarence. The latter only possessed the castle briefly before the king granted it to Lord Montague.

The castle was restored to the fourth Earl in 1470. The principal seat of the Percys was Alnwick Castle and Prudhoe was for the most part let out to tenants. In 1528 however Henry Percy 6th Earl was resident at the castle as later was his brother Sir Thomas Percy. Both the Earl and Sir Thomas were heavily involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536 and both were convicted of treason and executed. Following forfeiture of the estates the castle was reported in August 1537 to have habitable houses and towers within its walls, although they were said to be somewhat decayed and in need of repairs estimated at £20.

The castle was once again restored to Thomas Percy, the 7th Earl in about 1557. He was convicted of taking part in the Rising of the North in 1569. He escaped, but was recaptured and was executed in 1572.

The castle was thereafter let out to many and various tenants and was not used as a residence after the 1660s. In 1776 it was reported to be ruinous.

Between 1808 and 1817, Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland carried out substantial repairs to the ancient fabric and replaced the old dwellings within the walls with a Georgian mansion adjoining the keep.

In 1966 the castle was given over to the Crown.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On May 28th 1503 a Papal Bull was signed by Pope Alexander VI confirming the marriage of King James IV and Margaret Tudor and the "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" between Scotland and England.

From an early age, Margaret was part of Henry VII’s negotiations for important marriages for his children and her betrothal to James IV of Scotland was made official by a treaty in 1502 even though discussions had been underway since 1496. Part of the delay was the wait for a papal dispensation because James’ great-grandmother was Joan Beaufort, sister of John Beaufort, who was the great-grandfather of Margaret Tudor. That made James IV and Margaret Tudor fourth cousins, which was within the prohibited degree. Patrick Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, acted as a proxy for James IV of Scotland for his betrothal to Margaret Tudor at Richmond in January 1502 before the couple was married in person.

James was dashing, accomplished, highly intelligent and interested in everything, James IV of Scots enjoyed himself with mistresses while manoeuvring to secure a politically useful bride, so the marriage was not just an "English thing".

Our King was 30, his bride was what has been described as "a dumpy 13 year old".

I'll dip into the "newspaper" of the day in Grafton's chronicle the following was written....

"Thus this fair lady was conveyed with a great company of lords, ladies, knights, esquires and gentlemen until she came to Berwick and from there to a village called Lambton Kirk in Scotland where the king with the flower of Scotland was ready to receive her, to whom the earl of Northumberland according to his commission delivered her." he went on "Then this lady was taken to the town of Edinburgh, and there the day after King James IV in the presence of all his nobility married the said princess, and feasted the English lords, and showed them jousts and other pastimes, very honourably, after the fashion of this rude country. When all things were done and finished according to their commission the earl of Surrey with all the English lords and ladies returned to their country, giving more praise to the manhood than to the good manner and nature of Scotland."

Not exactly flattering words!

The wedding finally took place for real (after several proxy marriages) on 8 August, 1503 at Holyrood House in Edinburgh. Margaret was officially crowned Queen in March 1504. The Scottish poet William Dunbar wrote several poems to Margaret around this time, including “The Thistle and the Rose”, “To Princess Margaret on her Arrival at Holyrood”

Now fayre, fayrest of every fayre,

Princes most plesant and preclare,

The lustyest one alyve that byne,

Welcum of Scotlond to be Quene!

Margaret was apparently homesick and not happy in her early days in Scotland, but the couple settled down to married life, there first child, James was born four years later, he died within the year, their second, a daughter fared little better she never survived a day. In 1309 another son only lived to be nine months old, such was the difficulties of trying to produce and heir, it's a wonder the human race survived, what with mortality rates being so high in the nobility, one only wonders how high it would have been for the ordinary citizen of Scotland?

Meanwhile Margarets father passed away and Henry VIII took the throne.

Margaret’s next child was born on April 11, 1512 at Linlithgow and named James. He survived childhood and was to become King James V and father of Mary.

As for "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" it lasted around 10 years, in the first few years of Henry VIII’s reign, the relations with Scotland became strained, and it eventually erupt in 1513, when Henry VIII went to France to wage war, this invoked The Auld Alliance and James IV, Henry VIII's brother-in-law marched his army into England only to be disastrously cut down on September 9th at Flodden Field, with too many of our Scottish Knights to count. The Queen gave birth to another son, Alexander the following April, but things would turn sour for her.

Margaret, then regent, remarried into the powerful Douglas family, the Scottish Parliament then removed her as Regent a pregnant Margaret fled Scotland in 1515, her sons were taken from her before she left. She was given lodgings by her brother at Harbottle Castle, where she gave birth to daughter, Margaret Douglas, who herself played a big part in Scottish history, becoming mother to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.

That wasn't the last we had seen of Margaret Tudor though, she returned to Scotland with a promise of safe conduct in 1517 but her marriage to Douglas was a disaster, he had taken a mistress while she was in England.

In 1524 Margaret, in alliance with the Earl of Arran, overthrew Albany's regency and her son was invested with his full royal authority. James V was still only 12, so Margaret was finally able to guide her son's government, but only for a short time since her husband, Archibald Douglas, came back on the scene and took control of the King and the government from 1525 to 1528. This would all come back to bite the ambitious Douglas family in the bum

In March 1527, Margaret was finally able to attain an annulment of her marriage to Angus from Pope Clement VII and by the next April she had married Henry Stewart, who had previously been her treasurer. Margaret's second husband then arrested her third husband on the grounds that he had married the Queen without approval. The situation was improved when James V was able to proclaim his majority as king (he was 16 at the time) and remove Angus and his family from power. James created his new stepfather Lord Methven and the Scottish parliament proclaimed Angus and his followers traitors. However, Angus had escaped to England and remained there until after James V's death.

Margaret's relationship with her son was relatively good, although she pushed for closer relations with England, where James preferred an alliance with France. In this, James won out and was married to Princess Madeleine, daughter of the King of France, in January 1537. The marriage did not last long because Madeleine died in July and was buried at Holyrood Abbey. After his first wife's death, James sought another bride from France, this time taking Marie de Guise (eldest child of the Claude, Duc de Guise) as a bride. By this same time, Margaret's own marriage had followed a path similar to her second one when Methven took a mistress and lived off his wife's money.

On October 18, 1541, Margaret Tudor died in Methven Castl. probably from a stroke. Margaret was buried at the Carthusian Abbey of St. John’s in Perth. Although Margaret's heirs were left out of the succession by Henry VIII and Edward VI, ultimately it would be Margaret's great-grandson James VI who would become king after the death of Elizabeth.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today in history, February 14, 1400: the death of Richard II:

"Richard II (6 January 1367 – c. 14 February 1400), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed on 30 September 1399. Richard, a son of Edward, the Black Prince, was born in Bordeaux during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III. Richard was the younger brother of Edward of Angoulême, upon whose death, Richard, at three years of age, became second in line to the throne after his father. Upon the death of Richard's father prior to the death of Edward III, Richard, by primogeniture, became the heir apparent to the throne. With Edward III's death the following year, Richard succeeded to the throne at the age of ten.

During Richard's first years as king, government was in the hands of a series of councils. Most of the aristocracy preferred this to a regency led by the king's uncle, John of Gaunt, yet Gaunt remained highly influential. The first major challenge of the reign was the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. The young king played a major part in the successful suppression of this crisis. In the following years, however, the king's dependence on a small number of courtiers caused discontent among the influential, and in 1387 control of government was taken over by a group of aristocrats known as the Lords Appellant. By 1389 Richard had regained control, and for the next eight years governed in relative harmony with his former opponents.

In 1397, Richard took his revenge on the appellants, many of whom were executed or exiled. The next two years have been described by historians as Richard's "tyranny". In 1399, after John of Gaunt died, the king disinherited Gaunt's son, Henry of Bolingbroke, who had previously been exiled. Henry invaded England in June 1399 with a small force that quickly grew in numbers. Claiming initially that his goal was only to reclaim his patrimony, it soon became clear that he intended to claim the throne for himself. Meeting little resistance, Bolingbroke deposed Richard and had himself crowned as King Henry IV. Richard died in captivity in February 1400; he is thought to have been starved to death, although questions remain regarding his final fate.

Richard was said to have been tall, good-looking and intelligent. Less warlike than either his father or grandfather, he sought to bring an end to the Hundred Years' War that Edward III had started. He was a firm believer in the royal prerogative, something that led him to restrain the power of the aristocracy, and to rely on a private retinue for military protection instead; in contrast to the fraternal, martial court of his grandfather, he cultivated a refined atmosphere at his court, in which the king was an elevated figure, with art and In June 1399,

Louis, Duke of Orléans, gained control of the court of the insane Charles VI of France. The policy of rapprochement with the English crown did not suit Louis's political ambitions, and for this reason he found it opportune to allow Henry to leave for England. With a small group of followers, Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire towards the end of June 1399. Men from all over the country soon rallied around the duke. Meeting with Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, who had his own misgivings about the king, Bolingbroke insisted that his only object was to regain his own patrimony. Percy took him at his word and declined to interfere. The king had taken most of his household knights and the loyal members of his nobility with him to Ireland, so Henry experienced little resistance as he moved south. Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, who was acting as Keeper of the Realm, had little choice but to side with Bolingbroke. Meanwhile, Richard was delayed in his return from Ireland and did not land in Wales until 24 July. He made his way to Conwy, where on 12 August he met with the Earl of Northumberland for negotiations. On 19 August, Richard II surrendered to Henry at Flint Castle, promising to abdicate if his life were spared. Both men then returned to London, the indignant king riding all the way behind Henry. On arrival, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 1 September.

Henry was by now fully determined to take the throne, but presenting a rationale for this action proved a dilemma. It was argued that Richard, through his tyranny and misgovernment, had rendered himself unworthy of being king. However, Henry was not next in line to the throne; the heir presumptive was Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, who was descended from Edward III's third son, the second to survive to adulthood, Lionel of Antwerp. Bolingbroke's father, John of Gaunt, was Edward's fourth son, the third to survive to adulthood. The problem was solved by emphasising Henry's descent in a direct male line, whereas March's descent was through his grandmother.[f] The official account of events claims that Richard voluntarily agreed to abdicate in favour of Henry on 29 September.mAlthough this was probably not the case, the parliament that met on 30 September accepted Richard's abdication. Henry was crowned as King Henry IV on 13 October.

The exact course of Richard's life after the deposition is unclear; he remained in the Tower until he was taken to Pontefract Castle shortly before the end of the year. Although King Henry might have been amenable to letting him live, this all changed when it was revealed that the earls of Huntingdon, Kent and Salisbury and Lord Despenser, and possibly also the Earl of Rutland – all now demoted from the ranks they had been given by Richard – were planning to murder the new king and restore Richard in the Epiphany Rising. Although averted, the plot highlighted the danger of allowing Richard to live. He is thought to have starved to death in captivity on or around 14 February 1400, although there is some question over the date and manner of his death. His body was taken south from Pontefract and displayed in the old St Paul's Cathedral on 17 February before burial in Kings Langley Church on 6 March."

7 notes

·

View notes

Audio

The Young Visiters Or, Mr Salteena’s Plan by Daisy Ashford

CHAPTER 8 A GAY CALL

[Go to Table of Contents]

I tell you what Ethel said Bernard Clark about a week later we might go [off] and pay a call on my pal the Earl of Clincham.

Oh do lets cried Ethel who was game for any new adventure I would dearly love to meet his lordship.

Bernard gave a frown of jellousy at her rarther mere words.

Well dress in your best he muttered.