#for the narrative it was important that among a cast of characters with parental issues

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I don’t know why it took me so much time to get what I didn’t like about “Wednesday” the tv series, but now I have the precise word to round up ALL the stuff I dislike about it in one adjective.

“Unimaginative”.

This show lacks originality.

Consider what are the most succesful and beloved part of the show - for example, the visuals are liked, and the dance-scene of Wednesday is of course one of the most popular things. But don’t you think these are liked because they are actually the most original and inventive parts of the show? Aka, they stand out due to truly being unique?

Because look at the rest of the story... A typical, done many-times, “monster school” setting with “clique divisions” for teenagers to be “among their own kind” - a la Harry Potter and Percy Jackson. With the twist that here we are in “I am not like any other girl / I am a dark, broody, cynic character against a cheerful and normal world” (which is even pushed further as even the “monster world” is shown to be cheerful and normal compared to Wednesday).

We have an overdone love triangle between cliche characters - and that’s not just me saying it, everybody pointed out how this thing was just no substance and “by-the-book” formulaic, robbing the characters of depths. We have this sort of typical, overdone “family drama” between a teenager and her parents, tied with the whole “family secrets to undiscover”. We have the very important, but very badly tackled issue of “so-called normal people that are just racist VS excentric unusual people that are just normal”. We have a villain that is not only the most generic and cliche villain (ancient puritan guy wanting to destroy all “non-normals” out of a warped sense of normality, and even contradicting himself by becoming what he hates the most ; plus of course the twist villain seen a mile away).

There are so many cliche elements, and overdone formula, and just... conventional, expected or “usual” stuff in this show - but not done with a real twist, not changed, played with - they are just played straigth, with no actual bold move, with no innovation, with no real effort. Which is sad because it is what makes the very cool concepts tied to the show lost...

When you look carefully enough, almost none of the characters have depths, and two third of the cast have no personality whatsoever and are only “plot-tools” that serve to drive forward the narrative. And when they do have depths, it either ends up confusing as they do not have consistant depths, or they have depths that contradict the weak attempts at world-building - because even worse that characters not having depth, the WORLD ITSELF has no depth. We do not understand, and cannot understand, how this world works, since it only throws superficial, “cool-looking”, “kids-like-this-these-days” things at us, but to the point of blatant plot hole or obvious contradictions. It all seems like they actually didn’t know which direction they wanted to go to - or rather that there were different people with different concepts and ideas for this show, and that they try to unite them, but couldn’t manage to bring a cohesive thing.

This show isn’t bold or innovative in any way - it is a literal “safe show”, but not even a “safe show” done right, it is a “safe show” done bad, to the point of making it all an empty, vapid, pretending, if not pointless form of entertainment that actually wastes the cool concepts, excellent actors and good characters it actually starts with. I know that I am sorry I discovered Jenna Ortega through this show - because she is a good Wednesday Addams, and I would have love to see her and her character in any other iteraton of the Addams Family.

There was also so much concept for the school and its students - but I have said enough about how badly this was all handled.

I do truly adhere to the theory that this show probably wasn’t originally an Addams Family project, only to be rebranded as one. Or rather, I do think it more likely that it might have started out as a true Addams Family project, but midway someone (I don’t know if it is a writer, or director, or producer) hijacked it into becoming their own separate project, originally unrelated but that they saw an opportunity of doing. It would explain the conflicting characterization and backstory, the strange mix of good and bad elements that clearly go off in different directions and atmospheres, the ultimately “empty” feel of this show that is torn in so many different directions, almost as if several different series had been surimpressed.

But if it turns out that no, it was an Addams Family project to begin with and never changed - if it turns out that it is all just due to bad writers that did not have any original ideas and just copied what was “trending among teens” these days - if it turns out that this show was just an excellent concept poorly executed by people without true heart or passion for this (I am speaking of behind-the-camera staff of course, the actors did their best, and sometimes managed to save this show)... Then if it turns out to be that, it is all just very sad.

Note: The fact that this show was clearly conceived with all the expected, “popular”, cliche/stereotypical, “popular-with-kids” elements just picked because they were trendy and without much more thought given in it becomes VERY clear when you realize how this show has been taken over by these farm-content, dead-brain, borderline fetish “video for kids” all over Youtube. You know, the ones with auto-speech narration showing actors doing very weird and bizarre things, and targeted at young children (ultimately causing them brain damage). You couldn’t escape them.

Well, this show is one of their favorite materials to drag children down into their ungodly mess of repetive, formulaic, cliche, confusing and inconsistant scenarios...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond Mere Fantasy: How Animation Giants are Crafting Culturally Conscious Epics

Animation Directors Weave Serious Themes into Vivid Storytelling

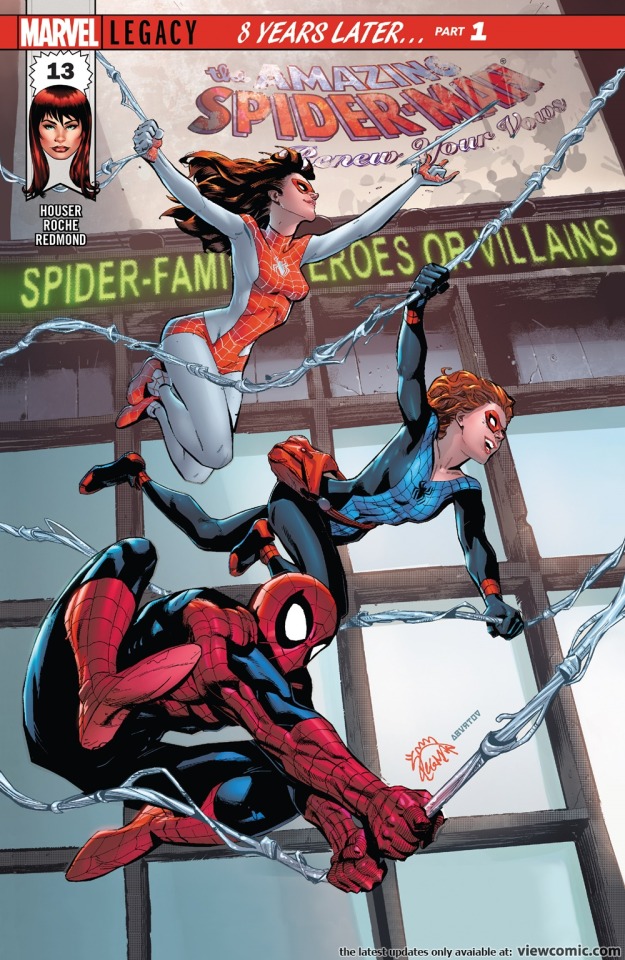

Modern animation has transcended its reputation as mere child's play. Once primarily considered the domain of cartoons and fantastical creatures, the realm of animated motion pictures is taking on weightier subject matter, merging vivid visuals with thought-provoking themes. At the forefront of this evolution are the latest offerings such as Pixar's Elemental and the sequel to Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. Directors Peter Sohn of Elemental and Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson of the new Spider-Man movie are receiving plaudits for their mature and sophisticated storytelling, striking a vibrant balance between high entertainment and meaningful messages.

Confronting Real-World Issues on the Animated Screen

In Elemental, Sohn endeavors to reflect the rich tapestry of an urban metropolis infused with allegories of immigration and community. Born of parents who emigrated from Korea, Sohn interweaves elements of his own heritage and upbringing in the bustling environment of New York. The film revolves around characters that personify the core elements—fire, water, land, and air—coming together in a city where diversity in all its forms is celebrated. Mirroring reality in a fantastical setting allows Sohn to approach delicate issues such as cultural integration and environmental consciousness with a gentle hand, inviting discussions among viewers of all ages. Pixar's narrative ambition continues to shatter the perceived boundaries of animation's capability to tackle complex societal issues.

'Spider-Man' Sequel Swings into Deeper Narrative Webs

The sequel to Into the Spider-Verse isn't merely swinging by to entertain; it's here to resonate with an ever-growing, diverse audience. The trio at the helm of the sequel recognizes the importance of respecting each character's unique background while casting an interconnected web that binds their fates. Dos Santos, Powers, and Thompson don't shy away from layering their storyline with a myriad of serious themes including identity, responsibility, and sacrifice that speak to both young and more mature audiences. Their earnest approach ensures that the characters have depth and humanity, breaking the mold of one-dimensional superheroes.

Navigating New Aesthetic Heights

Beyond thematic maturity, these animated films also dazzle with groundbreaking visual artistry. The Spider-Man sequel pushes the boundaries of traditional comic book aesthetics, constructing a richly animated multiverse that is both refreshingly innovative and nostalgically familiar. The film's commitment to a diverse visual experience is anticipated to add layers of depth to the storytelling, paralleling its narrative aspirations.

Setting the Bar for Animation

What this indicates is a clear signal that the animation industry acknowledges its vast and varied audience. Animated features such as Elemental and the Spider-Man sequel demonstrate an industry ripe for evolution—embracing the challenge of presenting serious, nuanced themes without abandoning the joy and wonder that animation naturally evokes. With their latest works, these directors are not only contributing to a broader cultural conversation but also raising the standards of animated storytelling. Animation no longer just mimics the complexities of life—it delves into them, creating a space for reflection, learning, and empathy. Trailblazers like Sohn and the Spider-Man directing trio are setting the course for an animated future where entertainment and depth go hand in hand, captivating hearts and minds across the generational spectrum. In redefining the genre, they're shaping a narrative legacy that will resonate for years to come. Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Sex Education is the Greatest Coming-of-Age Series Ever

In a world in which coming-of-age television shows and movies are around every corner, Laurie Nunn's Sex Education stands tall. The hilarious series is a modern masterpiece that has redefined the genre. This British dramedy first premiered on Netflix in 2019. Since its release, the series has captivated audiences worldwide with its unique blend of humor, heart, and unflinching exploration of adolescent sexuality. Compelling characters, progressive themes, and brilliant storytelling proves Sex Education has emerged as the best coming-of-age series of all time. At the heart of Sex Education lies a diverse and deeply complex cast of characters. Each character is thoughtfully crafted and undergoes significant growth throughout the series, making them relatable to viewers of all ages. The protagonist, Otis Milburn, played by Asa Butterfield. Otis is an awkward and intelligent teenager who grapples with his own sexual insecurities. Otis's journey from sexual ignorance to becoming a trusted sex advice guru is a captivating arc. His story mirrors the experiences of many adolescents navigating their own sexual awakening. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WldgrH9SvbE Maeve Wiley, portrayed by Emma Mackey, is another standout character. Maeve's troubled background, ambition, and vulnerability make her a relatable figure for viewers. Her friendship with Otis is central to the show's emotional core, and their dynamic reflects the importance of platonic relationships in adolescence. The ensemble cast, including Eric, Aimee, Jackson, and many others, adds depth and authenticity to the narrative. These characters address a wide range of issues, from LGBTQ+ experiences and racial diversity to body image and mental health. Through its diverse character roster, Sex Education invites viewers to empathize with the struggles and triumphs of adolescents from various backgrounds. Sex Education lives up to its title by fearlessly addressing one of the most fundamental aspects of adolescence: sexuality. Laurie Nunn's series tackles this subject matter with nuance, humor, and sensitivity, setting it apart from other coming-of-age shows. The show acknowledges that young people are curious about sex, often confused, and in need of guidance. It doesn't shy away from explicit content. This courage allows to show to use it as a vehicle for meaningful discussions about consent, communication, and self-acceptance. Otis's role as a sex advice counselor for his peers provides a unique lens. It's from this perspective that the show examines sexual issues. It highlights the importance of open communication, consent, and understanding in sexual relationships, empowering both the characters and the viewers to navigate this aspect of life with maturity and empathy. By addressing these topics head-on, Sex Education becomes a valuable resource for fostering healthy discussions about sex among young people and their parents. One of the most significant strengths of Sex Education is its commitment to addressing contemporary social issues. The series seamlessly weaves important themes such as LGBTQ+ acceptance, feminism, gender identity, and mental health into its narrative. These themes are not just surface-level additions but are deeply integrated into the characters' stories, contributing to their growth and development. Eric Effiong, portrayed by Ncuti Gatwa, is a prime example of the show's progressive themes. Eric's journey as a gay teenager navigating his identity, love life, and acceptance from his family and peers is portrayed with authenticity and sensitivity. Sex Education doesn't shy away from depicting the challenges Eric faces, but it also celebrates his resilience and self-discovery, sending a powerful message of hope and acceptance. Furthermore, the show challenges traditional gender roles and stereotypes. It presents female characters who are unapologetically strong and independent, addressing issues like slut-shaming and body image. Maeve Wiley, for instance, defies stereotypes by being a sharp-witted, entrepreneurial, and complex character who refuses to conform to societal expectations. While Sex Education tackles serious and sensitive subjects, it also balances them with a delightful dose of humor. The humor in the series is not only clever but also serves as a mechanism to humanize the characters. This allows Sex Education to make their experiences relatable. The awkwardness of adolescence, whether in the context of dating, friendships, or family dynamics, is portrayed with a perfect blend of wit and authenticity. The show's humor is complemented by its ability to create moments of genuine emotion and connection. These heartfelt moments resonate deeply with viewers, making them feel invested in the characters' lives. Whether it's Otis's relationship with his mother, Jean Milburn, or the evolving friendships among the main characters, Sex Education continually reminds us of the importance of empathy, compassion, and understanding in our own lives. The success of Sex Education would not be possible without the outstanding performances of its cast and the skilled direction of Laurie Nunn. Asa Butterfield's portrayal of Otis is a standout, capturing the character's vulnerability, growth, and humor. Emma Mackey brings depth and authenticity to Maeve's character, making her one of the most beloved figures in the series. Additionally, the supporting cast members deliver exceptional performances, ensuring that each character feels fully realized. Laurie Nunn's direction is marked by its visual creativity and emotional resonance. The show's setting, a mix of retro and modern aesthetics, adds a unique and visually appealing layer to the storytelling. Nunn's ability to create intimate and authentic moments between characters, even in the midst of humor and chaos, is a testament to her talent as a storyteller. Laurie Nunn's Sex Education transcends the typical coming-of-age series to become a modern masterpiece of television. Through its complex and relatable characters, fearless exploration of teenage sexuality, progressive themes, humor, and heartfelt moments, Sex Education captures the essence of adolescence in a way that resonates with viewers of all ages. Its outstanding performances and direction elevate it to a class of its own, making it the best coming-of-age series of all time. Laurie Nunn's creation reminds us that understanding, empathy, and open communication are essential components of the journey through adolescence, and it does so with unparalleled brilliance. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

“...On June 26, ad 4, Augustus adopted Tiberius. Livia’s son, forty-four years old, now became officially the son of her second husband. Henceforth he is called Tiberius Julius Caesar and is clearly the man designated to succeed the emperor. As he had in the past, Augustus made provision for the possibility that Tiberius might not necessarily survive him. Agrippa Postumus had not given any evidence of being temperamentally suited for high office, but Augustus perhaps hoped that in the general way of things an unruly youth could mature into a responsible adult. Hence the emperor adopted Postumus on the same occasion.

Moreover, Tiberius was obliged, before his own adoption, to adopt his nephew Germanicus, who would thereby become Tiberius’ son and would legally have the same relationship to Tiberius as his natural son, Drusus. The marriage of Germanicus and Agrippina followed soon after, probably in the next year. There is no reason why the unconcealed manoeuvring on behalf of Germanicus should have upset Livia unnecessarily, despite the clear implications of Tacitus that it did. Germanicus, after all, was her grandson as much as was Drusus Caesar. The arrangement reinforced rather than weakened the likelihood of succession from her own line, as was to be demonstrated by events.

The marriage would prove extremely fruitful. In time Agrippina bore Germanicus nine children, six of whom survived infancy. The first three were sons, great-grandsons of Livia: Nero, the eldest (not to be confused with his nephew Nero, the future emperor); Drusus (to be distinguished from the two more famous men of the same name: Drusus, son of Livia, and Drusus Caesar, son of Tiberius); and Gaius (destined to become emperor, and known more familiarly as Caligula). She also bore three surviving daughters, Drusilla and Livilla, and, most important, the younger Agrippina, mother of Livia’s great-great-grandson, the emperor Nero. The adoption of Tiberius in ad 4 would have been an occasion of joy and satisfaction for Livia, and would have helped to efface any lingering grief that still afflicted her over Drusus’ death.

If we are to believe Velleius, not only Livia but the whole Roman world reacted jubilantly to the new turn of events. Needless to say, his account should be treated with due caution. There was, he claims, something for everyone. Parents felt heartened about the future of their children, husbands felt secure about their wives, even property owners anticipated profits from their investments! Everyone looked forward to an era of peace and good order. A colourful exaggeration, of course, but there probably was considerable relief among Romans that the succession issue seemed at long last to be settled.

…In the immediate aftermath of the adoptions the ancient authors inevitably tend to focus on Tiberius and the campaigns he conducted in Germany and Illyricum, and they virtually ignore Agrippa Postumus, whose name was to be invoked later by sources hostile to Livia. A few details about Postumus emerge. In ad 5 he received the toga of manhood. The occasion was low-key, without any of the special honours granted Gaius and Lucius on the same occasion. It also seems to have been delayed. Postumus would have reached fourteen in ad 3, and under normal circumstances might reasonably have been expected to take the toga in that year. Something seems to be wrong. Augustus had certainly endured his share of problems with the young people in his own family. The pressures facing the younger relatives of any monarch are self evident, given the sense of importance that precedes achievement, to say nothing of the opportunists attracted to the immature and malleable, and prepared to pander to their self-importance.

As Velleius astutely remarks, magnae fortunae comes adest adulatio (sycophancy is the comrade of high position). These pressures must have been particularly intense in the period of the Augustan settlement, when no established standards had yet evolved for the royal children and grandchildren. Gaius and Lucius, the focus of Augustus’ ambitions and hopes, caused him endless grief by their behaviour in public, clearly egged on by their supporters, and on at least one occasion Augustus felt constrained to clip their wings. Gaius’ brave but distinctly foolhardy behaviour during the siege of Artagira is surely symptomatic of the same conceit.

There is no reason to assume that Postumus would have been immune from the pressures that turned the heads of his siblings. Whatever traits of haughtiness Postumus might have displayed in his early youth, they were not serious enough to have entered the record, and the exact nature of his personal and possibly mental problems is far from clear. The ancient sources speak of his brutish and violent behaviour. Some modern scholars have suggested that he might have been mad, but the language used of him seems to denote little more than an unmanageable temperament and antisocial tendencies.

For whatever reasons, eventually Augustus decided to remove him from the scene. The details of this expulsion are obscure. Suetonius provides the clearest statement, recording that Augustus removed Postumus (abdicavit) because of his wild character and sent him to Surrentum (Sorrento). The historian notes that Postumus grew less and less manageable and so was then sent to Planasia, a low-lying desolate island about sixteen kilometres south of Elba. Tacitus has no doubt about where the ultimate responsibility for Augustus’ actions lay. Postumus had committed no crime.

But Livia had so ensnared her elderly husband (senem Augustum) that he was induced to banish him to Planasia. Tacitus’ technique here is patent. The use of the word senem is meant to suggest that Augustus was by now senile, even though the event occurred eight years before his death. Incapable of making his own rational decisions, he would thus be at the mercy of a scheming woman, just as later Agrippina the Younger reputedly ‘‘captivated her uncle’’ Claudius (pellicit patruum). No reason is given for Livia’s supposed manoeuvre—which as usual, according to Tacitus, was conducted behind the scenes—except the standard charge that her hatred of Postumus was motivated by a stepmother’s loathing (novercalibus odiis).

Yet nothing in the rest of Tacitus’ narrative sustains his assertion, and the historian himself admits that the general view of Romans towards the end of Augustus’ reign was that Postumus was totally unsuited for the succession, because of both his youth and his generally insolent behaviour. Moreover, Augustus had made the strength of Tiberius’ position so patently evident that Livia would hardly have considered Postumus a serious candidate. This seems to be confirmed in a remarkable passage of Tacitus which uncharacteristically reports public reservations about a potential role for Germanicus, supposedly Tiberius’ rival.

After reporting the popular view that Postumus could be ruled out, Tacitus says that people grumbled that with the accession of Tiberius they would have to put up with Livia’s impotentia, and would have to obey two adulescentes (Germanicus and Drusus) who would oppress, then tear the state apart. Tacitus concedes that even the prospect of the reasonable Germanicus and Drusus being involved in state matters caused consternation. This surely offers some gauge of how far below the horizon Postumus was to be found. The precise reason for Postumus’ removal to Sorrento, if it was not simply his personality, is not clear. The initial expulsion may have been provoked by nothing more serious than personal tension between him and his adoptive father.

Whatever the initial reason, it soon became apparent that if Augustus had hoped that sending his adopted son out of Rome would solve the problem, he was mistaken. Dio places Postumus’ formal exile to Planasia in ad 7. If, as Suetonius claims, he was sent first to Sorrento, what might have precipitated the change in the location and the more grave status of his banishment? We have some hints in the sources. Dio suggests that one of the reasons for Augustus’ giving Germanicus preference over Postumus was that the latter spent most of his time fishing, and acquired the sobriquet of Neptune.

Now this could point simply to irresponsibility and indolence, but the picture of Postumus as an ancient Izaak Walton serenely casting his line does not fit well with the very strong tradition of someone wild and reckless. His activities may well have had a political dimension. The choice of the nickname Neptune could allude to the naval victories of his father, Marcus Agrippa. The fishing story might well belong to the period after Postumus’ relegation to Sorrento. This could have proved a risky spot to locate Postumus, because it lay just across the bay from the important naval base at Misenum that his father had established in 31 bc. The innocent fishing expeditions might have covered much more sinister activities.

Augustus may well have concluded eventually that Postumus was too dangerous to be left in the benign surroundings of Sorrento. During Postumus’ second, more serious phase of exile, on the island of Planasia, he was placed under a military guard, a good indication that he was considered genuinely dangerous rather than just a source of irritation and embarrassment. This final stage of banishment was a formal one, for Augustus confirmed the punishment by a senatorial decree and spoke in the Senate on the occasion about his adopted son’s depraved character. Formal banishment enacted by a decree of the Senate would be intended to make a serious political statement and should have buried completely any thoughts that Postumus might have been considered a serious candidate in the succession.

We cannot rule out the possibility that Postumus became involved, perhaps as a pawn, in some serious political intrigue, if not to oust Augustus then at the very least to ensure that he would be followed not by a son of Livia but by someone from the line of Julia. If Postumus was being encouraged to think of a possible role in the succession, it might reasonably be asked who was doing the urging. Although there is no explicit statement on the question in the sources, many scholars have accepted the notion that there existed a ‘‘Julian party,’’ responsible for much of the ‘‘anti-Claudian’’ propaganda directed against Livia and Tiberius that is found in Tacitus in particular and possibly derived from the memoirs of Agrippina.

…Whatever the intrigues in Rome, Livia’s son was able to keep himself aloof and to play the role that suited him best, that of soldier. Tiberius conducted a brilliant series of campaigns in Pannonia for which a triumph was voted in ad 9. (This was postponed when Tiberius was despatched to Germany in the aftermath of the disastrous defeat of Quinctilius Varus, in which three legions were lost.) When the Pannonian triumph was voted, Augustus made his intentions crystal clear. Various suggestions were put forward for honorific titles, such as Pannonicus, Invictus, and Pius.

The emperor, however, vetoed them all, declaring that Tiberius would have to be satisfied with the title that he would receive when he himself died. That title, of course, was Augustus. It also appears that a law was later passed to make his imperium equal to that of Augustus throughout the empire, and in early 13 his tribunician power was renewed. His son Drusus Caesar received his first accelerated promotion, designated to proceed directly to the consulship in ad 15, skipping the praetorship that should have preceded this higher office.

The virtual impregnability of Tiberius’ position should be borne in mind in any attempt to understand the final months of Augustus’ life. In the closing chapter of her husband’s principate, Livia reemerges in the record to play a central and, according to one tradition, decidedly sinister role. This is perhaps the most convoluted period of her career, where rumour and reality seem to diverge most widely. To place the events in a comprehensible context, it is necessary to note one later detail out of its chronological sequence. As we shall see, after Augustus’ death there was a rumour reported in some of the sources that Livia had murdered her husband.

In the best forensic tradition, a motive would have to be unearthed to make the charge plausible, especially since sceptics could hardly have failed to notice that Augustus had never enjoyed robust health and was already in his seventy-sixth year. Death from natural causes could hardly be considered remarkable under such circumstances. The requisite motive would indeed be produced, and the kernel of the intricate thesis that evolved is found in a brief summary of Augustus’ career by Pliny the Elder. Among the travails that afflicted the emperor, Pliny lists the abdicatio of Postumus after his adoption, Augustus’ regret after the relegation, the suspicion that a certain Fabius betrayed his secrets, and the intrigues of Livia and Tiberius.

Pliny’s summary observations are clearly based on a more detailed source, which suggested that Augustus felt some remorse about Postumus. This simple and not improbable notion is developed by other sources into a far more complex scenario that creates an apparently plausible motive, because it could be claimed that Livia would have wanted to remove her husband before he could act on his change of heart. This reconstruction of the events is clearly reminiscent of the closing days of the reign of Claudius, when the emperor supposedly sought a rapprochement with his son Britannicus, to the disadvantage of his stepson Nero, and thereby inspired his wife Agrippina to despatch him with the poisoned mushroom.

But it is important to bear in mind that as Pliny reports the events he limits himself to the claim that Augustus regretted Postumus’ exile, without further elaboration, and although Livia and her son supposedly engaged in intrigues of some unspecified nature, Pliny assigns no criminal action to either of them. Pliny’s ‘‘skeleton account’’ is to some degree validated by Plutarch. In his essay on ‘‘Talkativeness,’’ Plutarch, in a very garbled passage, relates that a friend of Augustus named ‘‘Fulvius’’ heard the emperor lamenting the woes that had befallen his house—the deaths of Gaius and Lucius and the exile of ‘‘Postumius’’ on some false charge—which had obliged him to pass on the succession to Tiberius. He now regretted what had happened and intended (bouleuomenos) to recall his surviving grandson from exile.

According to Plutarch’s account, Fulvius passed this information on to his wife, and she in turn passed it on to Livia, who took Augustus to task for his careless talk. The emperor made his displeasure known to Fulvius, and he and his wife in consequence committed suicide. This last detail was perhaps inspired by the famous story of Arria, who achieved immortal fame in ad 42 when she died with her husband Caecina Paetus, who had been implicated in a conspiracy against Claudius. Plutarch’s confused version of events does not inspire confidence, and in any case, although he gives Livia a more specific role than does Pliny, he follows Pliny in not attributing to Augustus any action, only supposed intentions.

Dio’s account is a much contracted one, but derived from a source that has added a very important wrinkle to the story and has Augustus taking action on his change of heart. Dio says that Livia was suspected of Augustus’ death. She was afraid, people say (hos phasi), because Augustus had secretly sailed to Planasia to see Postumus and seemed to be on the brink of seeking a reconciliation. This bald and surely implausible story, involving a round trip of some five hundred kilometres, is given its fullest treatment in Tacitus, clearly drawing on the same source as Dio.

He says that people thought that Livia had brought about Augustus’ final illness, because a rumour entered into circulation that the emperor had gone to Planasia to visit Postumus, accompanied by a small group of intimates, including Paullus Fabius Maximus. Fabius, clearly Plutarch’s ‘‘Fulvius,’’ was a literary figure of some renown, a close friend of Ovid and Horace. He was also an intimate of Augustus, consul in 11 bc, governor of Asia, and legatus in Spain (3–2 bc). He would thus be a plausible participant in this mysterious expedition. Tacitus reports that the tears and signs of affection were enough to raise the hopes of Postumus that there was a prospect of his being recalled. (It is striking that Tacitus is ambiguous about the meeting’s purpose and is too good a historian to bring himself to claim that Augustus had gone there to commit himself to Postumus’ rehabilitation.)

Fabius Maximus supposedly told the story to his wife, Marcia, and she in turn passed it to Livia. The text of the manuscript is corrupt at this point, but Tacitus seems to say that this indiscretion came to the knowledge of Augustus (reading the text as gnarum id Caesari). The subsequent death of Fabius, Tacitus says, may or may not have been suicide (the implication is that Augustus ordered it, as Plutarch suggests). Marcia was heard at the funeral reproaching herself as the cause of her husband’s downfall (this presumably is how the story got out).

After this detailed account Tacitus undercuts his own case when he goes on to say that Augustus died shortly afterwards, utcumque se ea res habuit. The force of this phrase is essentially ‘‘whatever the truth of the matter.’’ It hardly inspires conviction. The story of the adventurous journey to Planasia and the tearful reconciliation has generally been greeted with scepticism by modern scholars. Jameson is an exception. She uses the Arval record to argue that Augustus did take the trip, noting that on May 14 there was a meeting of the brethren for the cooption of Drusus Caesar, the son of Tiberius, into their order. Fabius Maximus and Augustus were absent from the ceremony, and submitted their votes, in favour of the co-option, by absentee ballot. But is there anything remarkable in their absence?

Clearly, the election of Tiberius’ son was not in reality a particularly important occasion, for Tiberius himself failed to attend. Moreover, Syme notes that no fewer than five other arvals were absent from this meeting, and that there could be a host of explanations for Augustus’ absence. Also, if the co-option was seen as an important family event, then it would surely have been the very worst time for Augustus to try to slip away unnoticed. The emperor was by this time in declining health, so weak that he even held audiences in the palace lying on a couch. In ad 12 he was so frail that he stopped his morning receptions for senators and asked their indulgence for his not joining them at public banquets.

Yet we are supposed to assume that he made the arduous journey to Planasia, and that he did so without Livia realizing what he was up to. It is also important to observe that both Tacitus and Dio drew on a source claiming that Augustus was on the verge of making amends with Postumus. An actual reconciliation seems to be ruled out by the later sequence of events. Certainly he did nothing whatsoever on his return to strengthen Postumus’ position or to weaken that of Tiberius. Finally, one might ask whether Augustus could ever have seriously considered recalling Postumus. He had put him under armed guard. There were plots to rescue him. His supporters published damaging letters about the emperor. It all seems implausible. Syme suggests that the details of the journey might have been added soon after Augustus’ death, a ‘‘specimen of that corroborative detail which is all too apparent (and useful) in historical fictions.’’ Syme bases his argument in part on aesthetic considerations. The episode as it appears in Tacitus is introduced in an inartistic fashion and appears to have been grafted on as an afterthought, introducing two names, those of Fabius Maximus and his wife, Marcia, that will not be mentioned again in the Annals. Moreover, neither Pliny nor Plutarch mentions Planasia.

…The plot described by Suetonius might then have been a last desperate effort to rescue her. In any case it seems to have come to nothing. In addition to the supposed political intrigues in the period immediately before Augustus’ death, there was no shortage of signs that the gods, too, were feeling distinctly uneasy, ranging from the usual comets and fires in the sky to more opaque portents, like a madman sitting on the chair dedicated to Julius Caesar and placing a crown on his own head, or an owl hooting on the roof of the Senate house. But Augustus seems to have had no premonition that he had little time left when he set out from Rome in August 14.

At that time Tiberius was obliged to leave the city for further service abroad, and he departed for Illyricum with a mandate to reorganise the province. Livia and Augustus joined him for the first part of the journey. This very public gesture is an affirmation of the emperor’s faith in Tiberius—a very odd signal to send if only a few months earlier he had become reconciled to Postumus and had changed his mind about who would succeed him. The party went as far as Astura, and from there followed the unusual course of taking a ship by night to catch the favourable breeze. On the sea journey Augustus contracted an illness, which began with diarrhoea.

They skirted the coast of Campania, spent four days in Augustus’ villa at Capri to allow him to relax and recuperate, then sailed into the Gulf of Puteoli, where they were given an extravagant welcome from the passengers and crew of a ship that had just sailed in from Alexandria. They passed over to Naples, although Augustus was still weak and his diarrhoea was recurring. He managed to muster up the strength to watch a gymnastic performance. Then they continued their journey. At Beneventum the company broke up. Tiberius headed east. As Augustus began the return journey with Livia from Beneventum, his illness took a turn for the worse. Perhaps he had a sense that his end was near, as he made for an old family estate, in nearby Nola, where his father, Octavius, had died.

Augustus was not to leave Nola alive. His condition quickly grew worse, and on August 19, 14, at the ninth hour, in Suetonius’ precise report, he died. According to Tacitus, as Augustus grew more sick, some people started to suspect (suspectabant) Livia of dirty deeds (scelus). Dio is more specific, but is still cautious about the charge. He notes that Augustus used to gather figs from the tree with his own hands. She, hos phasi (as they say), cunningly smeared some of them with poison, ate the uncontaminated ones herself and offered the special ones to her husband. As can be seen in his handling of other events, Dio does seem to relish rumours of poisoning.

He relates, for instance, that Vespasian died of fever in ad 79, but adds that some said that he was poisoned at a banquet. It was similarly said that Domitian murdered Titus in ad 81, although the written accounts agree that he died of natural causes. In the case of Augustus it may be possible to discern the origins of the rumour. Suetonius confirms that the emperor was fond of green figs from the second harvest (along with hand-made moist cheese, small fish, and coarse bread). Given Livia’s interest in the cultivation of figs (she even had one named after her), she may well have had an orchard at Nola to which she would have given special attention during her stay.

Dio in fact seems to have had little personal faith in the fig rumour, for he goes on to speak of Augustus’ death as ‘‘from this or from some other cause.’’ By its nature the fig story is unprovable yet impossible to refute. It falls in the grand tradition of such deaths, the best-known being the supposed despatch of Claudius by a poisoned mushroom. If Livia murdered Augustus, then her timing was oddly awry, for she had to go to considerable trouble to recall Tiberius, who was by then en route to Illyricum. Why not do the deed when he was still on the scene?

It is perhaps worth bearing in mind that Livia had an interest in curative recipes. It is possible that she would have inflicted one or more of her own concoctions on her husband. In the unlikely event that he was poisoned, alternative medicine might be a more plausible culprit than the murderer’s toxin. From Beneventum, Tiberius headed for the east coast of Italy, where he took a boat to Illyricum. He had barely crossed over to the Dalmatian coast when an urgent letter from his mother caught up with him, recalling him to Nola. There are different versions of what happened next. Tacitus describes Augustus in his final hours holding a heavy conversation with his entourage about the qualifications of potential successors. Dio and Suetonius allow him a lighter agenda.

They recount that he first asked for a mirror, combed his hair and straightened his sagging jaws. Then he invited the friends in. He gave them his final instructions, ending with his famous line of finding Rome a city of clay and leaving it a city of marble. In conclusion, he asked how they would rate his performance in the grand comedy of life. He seems to have taken a high score for granted, because just like a comic actor, he asked them to give him applause for a role well played. (The curious coincidence of the comic actors brought in during Claudius’ last hours should be noted.)

He then dismissed his friends and spoke to some visitors from Rome, asking about the health of Tiberius’ granddaughter Julia, who was ill. The most serious discrepancy arises over the part that Tiberius might have played during the emperor’s final hours. Dio preserves one tradition, which he says he found in most authorities, including the better ones, that the emperor died while his adopted son was still in Dalmatia, and that Livia for political reasons was determined to keep the death secret until he got back. Tacitus reflects a similar tradition, reporting uncertainty about whether Tiberius found Augustus dead or alive when he reached Nola. The house and the adjoining streets had been sealed off by Livia with guards, and optimistic bulletins were issued, until she was ready to release the news at a time dictated by her own needs.

The story is reminiscent of Agrippina’s arrangements after the death of Claudius. She was similarly accused of keeping the death secret and posting guards as Claudius lay dying. The suspicions about Livia do not appear in the other extant accounts. Velleius reports that Tiberius rushed back and arrived earlier than expected, which perked up Augustus for a time. But before too long he began to fail, and died in Tiberius’ arms, asking him to carry on with their joint work.

Suetonius is even more emphatic about Tiberius’ role. He says that Augustus detained Tiberius for a whole day in private conversation, which was the last serious business that he transacted. His final moments were spent with Livia. His mind wandered as he died—he thought that forty men were carrying him away—but at the last instant he kissed his wife, with an affectionate farewell, Livia nostri coniugii memor vive, ac vale (Livia, be mindful of our marriage, and good-bye), then slipped into the quiet death that he had always hoped for.

That Livia might have kept the news of Augustus’ death secret for a time is certainly plausible—there are all sorts of sound reasons why the announcement of a politically sensitive death might be postponed, although the similar delay after Claudius’ death is disturbingly coincidental. She also may well have put pickets around the house, but no sinister connotation need be placed on the action. The final hours of Augustus would doubtless have attracted the concerned and the curious, who in such situations follow a herd instinct to keep crowded vigils. After Agrippina the Younger had been shipwrecked near Baiae in ad 59, crowds of well-wishers streamed up to her house, carrying torches.

The same would surely have happened in Nola, and some sort of control might have become necessary to give the dying emperor some peace. The house certainly became a place of pilgrimage afterwards, and was converted into some sort of shrine. The romantic account of Augustus expiring in Tiberius’ arms may be highly coloured, and Suetonius’ claim that Augustus and Tiberius spent a whole day together sounds exaggerated, given that Augustus’ health was fading so fast.

But it is difficult to see how that whole sequence of events could simply have been invented if it did not have at least a basis of truth. In any case, rumours surrounding the events at Augustus’ deathbed were totally eclipsed by dramatic developments across the water. As an immediate consequence of the emperor’s death, Postumus also lost his life: primum facinus novi principatus fuit Postumi Agrippae caedes (the first misdeed of the new principate was the slaying of Agrippa Postumus), as Tacitus words it.

The events of this first and possibly murkiest episode of Tiberius’ reign have been much debated, and it is probably now impossible to disentangle fact from rumour and innuendo, since there is considerable ambiguity in the ancient accounts of the incident. The general outline of the events is not particularly controversial. The officer commanding the guard at Planasia executed Postumus after he had received written instructions (codicilli) to carry out the deed. Postumus had no weapons other than his powerful physique, and he put up a valiant but ultimately futile struggle. A desperate attempt by a loyal slave, Clemens, to save him was frustrated when the would-be rescuer took a slow freight ship to Planasia and arrived too late.

After the execution, the officer then reported to Tiberius, presumably still at Nola, that the action had been carried out. He did so, as Tacitus describes it, ut mos militiae (in the military manner), presumably in the sense of a soldier reporting to his commander that his orders have been discharged. Tiberius denied vehemently that he had given any such orders. According to Tacitus, he claimed that Augustus had sent the order, to be put into force immediately after his death, and insisted that the officer would have to give an account to the Senate. Tacitus at this point adds a new wrinkle to the story, and gives a role to a figure not mentioned in any of the other sources in the context of this incident.

The codicilli, he claims, had been sent to the tribune by Augustus’ confidant Sallustius Crispus. This man was the great-nephew and adopted son of the historian Sallust. Although his family connections had opened up the opportunities for a brilliant senatorial career, Sallustius chose to fashion himself after Maecenas and seek real influence rather than the empty prominence of the Senate. He rose to the top through his energy and determination, which he managed to conceal from his contemporaries by pretending a casual or even apathetic attitude to life.

He acquired considerable wealth, owning property in Rome, and among other landed estates he could list a copper mine in the Alps producing high-grade ore. More importantly, at least until his later years, he had the ear of both Augustus and Tiberius, as a man who bore the imperatorum secreta (secrets of the emperors). When Sallustius learned that Tiberius wanted the whole matter brought before the Senate, he grew alarmed, afraid that he personally could end up being charged. He interceded with Livia, alerting her to the danger of making public the arcana domus (the inner secrets of the house), with all that would entail—details of the advice of friends, or of the special services carried out by the soldiers—and urged her to curb her son. Beyond this general framework the details are highly obscure, and, it seems, totally speculative.

Tacitus says that Tiberius avoided raising the issue of Postumus’ death in the Senate, and Suetonius observes that he simply let the matter fade away. There would thus have been no official source of information. Yet fairly detailed narratives have been passed down, which could have come only from eyewitness accounts. In particular one has to wonder how the supposed secret dealings between Livia and Sallustius could ever have become known. This uncertainty over the source and reliability of the information clearly makes it impossible to determine who was ultimately responsible for Postumus’ death.

Suetonius summarises the problem nicely. He states that it was not known whether Augustus had left the written instructions, on the verge of his own death, to ensure a smooth succession, or whether Livia had dictated them (dictasset) in the name of Augustus, and, if the latter, whether Tiberius had known about them. Dio categorically insists that Tiberius was directly responsible but says that he encouraged the speculation, so that some blamed Augustus, some Livia, and some even said that the centurion had acted on his own initiative.

Tacitus found Tiberius’ claim that Augustus had left instructions for the execution hard to believe, and describes this defence as a posture (simulabat), suggesting that the more likely scenario was that Tiberius and Livia hastily brought about the death, Tiberius driven by fear and she by novercalibus odiis (stepmotherly hatred). Velleius may have been aware of these speculations, for he is very cagey about Postumus’ death. He insists that ‘‘he suffered an ultimate fate’’ (habuit exitum) in a way that was appropriate to his ‘‘madness’’ ( furor). Velleius may well have been deliberately ambiguous to avoid becoming enmeshed in a contentious and sensitive issue that might reflect badly on Tiberius.

Scholars have generally been inclined to exonerate Livia, and only Gardthausen has held that Livia was totally responsible, without even Tiberius’ complicity. Syme accuses Tacitus of supporting an imputation against Livia ‘‘which he surely knew to be false.’’ The implication of Livia has been challenged by Charlesworth in particular. He sees it as emanating from the same tradition that had her poisoning Augustus. Certainly Pliny’s brief summary imputes no criminal action against her. She seems on principle to have refrained from taking independent executive action. (The picket she set up around Augustus’ house would be the only known counterexample.)

At most, it is possible that she knew of such an order, but it seems highly unlikely that she initiated it. Even if a meeting did actually take place between Sallustius and Livia, as Tacitus alleges, this need not mean that anything sinister had necessarily been underfoot. Sallustius may have wished simply to appeal to the wisdom and experience of Livia to counter the political naïveté of a son who had spent his career on military campaigns and had not yet become adept in the complexities of political intrigue. The suppression of information about the activities of the soldiers could just as easily have been meant to refer to Augustus’ instructions as to Livia’s, in a system where secrecy for the sake of secrecy was considered a vital element in the fabric of efficient government.

If Livia had somehow been involved with Sallustius in carrying out Augustus’ instructions, there would have had to be secret and dangerous communication between Rome and Nola, unless Sallustius was also with Augustus at the end (and Tacitus would surely have mentioned his presence). Tiberius seems largely exonerated by his own conduct. If he had been guilty, he would hardly have wanted an investigation by the Senate, and could simply have claimed that the execution was carried out on Augustus’ orders or even have reported officially that Postumus had died from natural causes. We can surely eliminate Dio’s barely tenable suggestion that the guard might have executed Postumus on its own initiative, and the hardly more convincing notion that Sallustius Crispus similarly might have acted on his own initiative.

On balance, the most plausible suspect is Augustus, although plausibility is far different from conviction. Augustus might well have issued standing orders to the tribune to execute Postumus the moment news of his own death arrived. Sallustius could well have sent the announcement of the emperor’s death in Tiberius’ name (with or without his knowledge), which could account for the centurion’s coming to Rome to make a report to Tiberius.

When he needed to, Augustus could behave quite ruthlessly against those who threatened him. He put to death Caesarion, the supposed son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, for purely political motives. He also could be harsh towards his own family. He swore that he would never recall the elder Julia from exile, refused to recognise the child of the younger Julia, and would not allow either Julia burial in his mausoleum. It was he who had set the armed guard over Postumus. Moreover, Augustus did make meticulous preparations for his own death.

He left behind three or four libelli, with instructions for his funeral, the text of the Res Gestae, a summary of the Roman troops, fleets, provinces, client-kingdoms, direct and indirect taxes—including those in arrears— the funds in the public and in the imperial treasuries, and the imperial accounts. There was also a book of instructions for Tiberius, the Senate, and the people. Augustus went into considerable detail, with such particulars as the number of slaves it would be wise to free and the number of new citizens who should be enrolled.

He was clearly a man determined not to leave any issues hanging in the balance, and the future of Postumus would have been an issue of prime importance. Postumus’ death was the final blow for Julia the Elder. From this point on, she simply gave up and went into a slow decline, her despair aggravated by her destitution. She received no help from Tiberius, although he had earlier tried to win leniency for her from her father.

According to Suetonius, Tiberius, once emperor, deprived her of her allowance, using the heartless argument that Augustus had not provided for it in his will. As we have seen, Livia might well have helped the exiled Julia at one point by giving her one of her slaves, and she certainly helped Julia’s daughter when she was sent away from Rome. But she does not seem to have tried to intercede on this occasion. Julia died in late ad 14 from weakness and malnutrition. The new reign had got off to a bloody start.”

- Anthony A. Barrett, “The Public Figure.” in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome

#livia drusilla#postumus#octavian#tiberius#roman#ancient#history#anthony a. barrett#livia first lady of imperial rome

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY I LOVE THE SCARABIA CM AND YOU SHOULD TOO

Listen, I don’t even know why you’d actually need to look for a reason to love and cherish this beautiful piece of animation, but to each their own. Regardless, you’re in the right place, because I’m about to gush and cry over this CM just to convince you to show it the same level of love that I feel for it. It’ll be difficult, but don’t worry, I’ll be there with you the entire time. So, let’s start with the beginning.

What makes this CM different from the others? Well, let’s look at the most obvious aspect: it’s narrated by two people, instead of just the Overblot victim like in the case of the Heartslaybyul, Savanaclaw and Octavinelle. There we had only Riddle, Leona and Azul speak because, obviously, as the Prefects and shadows of the villains they would be the most important characters. You could call that antagonist privileges if you want, but there’s a reason a show with a big cast doesn’t go in depth with every single one of their characters. Not only would it be infeasible, but also useless. Narratives need a point of focus, otherwise they end up disjointed and incomprehensible.

So why didn’t this CM just have Jamil narrate? He’s the antagonist of chapter 4, after all. Shouldn’t he get his own moment in the spotlight, separate from Kalim? Well, yes and no. For you see, the thing about Scarabia is that unlike other dorms the relationship between the Prefect and vice dorm leader is much more complicated. By which I mean that no other vice dorm leader is an indentured servant to the family of their dorm’s Prefect. Trey is Riddle’s childhood friend, Ruggie sticks with Leona because it gives him a better chance for survival, the Leech twins stay with Azul out of curiosity, Rook admires Vil, Ortho is Idia’s little brother (?) and Lilia has served as Malleus’ parental figure.

(Also, yes, I’m counting Ruggie and Ortho as vice dorm leaders since that’s basically their role anyways.)

None of them are bound to their Prefect. Trey has a life outside of Riddle, Ruggie will drop Leona like a sack of potatoes if the latter gets too much to deal with, the Leech twins EXPLICITLY say that they will turn on Azul if they get bored, Rook actually points out Vil’s flaws to his face, Ortho doesn’t let his brother get away with everything and Lilia’s position is more of a trusted family friend, than an actual guard/babysitter. The point I’m trying to make is that all these people have choices when it comes to their relationships with their respective Prefects. They stay by their side out of their own will and not because someone is forcing them to be there.

The same doesn’t apply to Jamil. He can’t just decide to leave Kalim’s side one day, because he was getting sick of looking after him. And that’s because he didn’t have a choice in being by his side in the first place. That decision was made for him by his parents. Because that’s how indentured servitude works: when you’re in the service of a lord, especially if you’re a poor peasant, your period of time decided upon entering the contract tends to extend to future generations as well since you’re not given any money to save. Most peasants that found themselves in such positions often would marry and start a family while still in the service of their lord and should they die, their family, unable to provide for themselves because their whole life was spent doing unpaid labour, will also enter the same contract. This process would go on until either slavery, which this most certainly is, was banned or the lord decided to set you free. The former was much preferable to the latter, because in a feudal system to be set free by your lord often marked you as an undesirable servant. You would be hard pressed to find a lord that would ‘hire’ you after finding out your former ‘employee’ decided to ‘fire’ you. So it would be very rare for indentured servants to actually manage to free themselves from that position.

This is precisely where Jamil’s frustration arises from as well. As a capable individual, he’s acutely aware of the limitations his status imposes on him. He’s a servant of the Asim family from birth, much like his parents and grandparents were before him. This is not something he chose for himself, but rather something that was imposed upon him. Herein lies the central issue that defines Jamil’s character: lack of choice. Much more than any character, Jamil’s life is governed by the limitations that arise due to his social position. We see that ever since his childhood he was forced to always take into consideration Kalim’s abilities and model his performance as not to eclipse him in any way. If Kalim placed second place in a dancing competition, Jamil must not be among the top three. If Kalim’s grades slipped, his own grades must as well. If Kalim lost two times in a row at mancala, Jamil must make sure he loses the next three games. Yet, paradoxically enough he mustn’t fall behind too much either, for that would make him a useless servant. And as I pointed out before, inept servants are not considered desirable by those in power.

It is in essence a balancing act that Jamil must make sure he adheres to strictly, as not to bring shame to the Asim family to whom he is, in theory, loyal. In relation to Kalim, Jamil must make sure he performs poorly, but in relation to others he must make sure he performs well. It’s that precise position between exceptional and ordinary that he must achieve, and according to Azul, Jamil is excelling at that.

Azul: You usually never make yourself stand out—A wallflower, so to speak.

You make sure not to stand out academically, too. Whether it’s with class standing, or with practical training. But, at the same time…

You never get failing scores. (4-37)

Yet the question we must ask is why? Why must Jamil follow these demands?

Well, for one it’s the issue of the indentured servant that we have discussed before. Jamil is bound to the Asims and going against them will bring repercussions not only on himself, but on his family as well. In the modern age in which Twisted Wonderland seems to be set in, this would not be much of an issue, we would guess. However, while that might be true, we must consider it not only from a logical perspective, but a psychological one as well. The human brain is fascinating in the sense in which it is able to transform information into patterns. And nowhere is this most apparent than in the impregnation of cultural norms into the mind. We tend to think of some things as innately ‘normal’ and ‘ordinary’ and everything that goes against those beliefs as ‘perverse’ and ‘immoral’. For example, up until a few decades ago, the idea of women as second-class citizens was seen as a perfectly reasonable notion. Those that did not agree with it were considered troublemakers and agitators, and if there’s anything the human individual loves more conformity, it’s ensuring that it’s enacted upon the population at large. The nail that sticks out gets the hammer, as the saying goes.

But what does this have to do with Jamil? Well, the fact is that his role, as Kalim’s servant, comes with certain social expectations.

Jamil: Kalim’s parents were always better than my parents. That’s why… Kalim should be better than me, too. That’s why, I could never surpass Kalim when it comes to studying, exercise, and even playing— (4-36)

The role of a servant is that of support. The Master leads while they provide the conditions and the means to do that. That is precisely the position that the Viper family is supposed to take in relation to the Asim family. For a servant to surpass his master, it leads to a deeply problematic realization: that one’s status is divorced from one’s capacity. Medieval rule was often characterized by monarchs assigning themselves as God’s anointed on Earth. Their right to the throne was not ensured by their capacity or disposition or ideals, but simply by their nature. They were meant to rule, because of the social class and family they were born into. Nothing less, nothing more. It was instinctively understood that there was a great differentiation between them and the common people and that was translated in their position as those to be considered ‘elevated’. They did not mingle with the common folk, because that was beneath them.

And unfortunately, that is a cultural inheritance that is not easily done away with. For though we might claim we left behind the days of feudalism and vassals, there is still a great divide between social classes. It merely took a different form. Lords of the castle turned into politicians, celebrities and glamorous multimillionaires. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, as Shakespeare would put it. Call it what you will, but the end result is that social divide still exists. And we can see that is the case in Twisted Wonderland as well.

Though the game tends to gloss over it in certain aspects, by having Leona’s reception by the main student body be as that of a lazy Prefect, and Malleus’s position is often eclipsed by his elusive attitude, it is constantly made clear that Kalim is someone with an important social background. We might have to be reminded that Leona is the second prince of the Afterglow Savannah, or that Malleus is the next king of the Valley of Thorns, but we aren’t offered the same discretion with Kalim’s character. He is almost always introduced as Kalim, the heir of a multimillionaire family. It is thus impossible to separate him from this title, and by extension, Jamil as well. Whether he likes it or not, as the servant of the Asims, Jamil is tethered to Kalim by being a part of his social image. No true Master can exist without servants, and no servants can be had without a Master. The two are reliant on each other, much like Kalim and Jamil are reliant on the other to define their position in life.

Kalim is the son of a wealthy family because he has Jamil to prove his special status. Jamil is a servant of the Asim family because he has someone to serve. But whether he wants to be part of this system and have his identity be defined by this connection is out of his hands. And that’s the truly unbearable notion that Jamil has to deal with in his chapter: no matter what he does he is never in control of his own life. It’s always something that is decided for him.

This, in itself, is not coincidental I would say. You see, besides being interesting social commentary, it is also an unexpected look into the underlying themes of Disney’s Aladdin. If we were asked to describe what the movie is about, I think it’s safe to say most of us would cite “poor street-rat learns a valuable lesson about not pretending to be someone else and marries the princess” as the answer. And we would not be wrong. It’s obvious that “Be Yourself” is one of the most important lessons Disney wanted to teach to young children and this in itself is not a bad thing. But while these might be understood as genuine life advice at a young age, as adults we often tend to look more closely into the themes and motifs of the movies that shaped our childhoods. And thus I would argue that Aladdin is more than just a story about interclass romance, but rather a look into how the social class system functions as a whole. Aladdin, the main hero, is a street urchin with no money to his name. Jasmine, the heroine, is the daughter of one of the most powerful men in the land. Their romance and subsequent marriage is interpreted as a victory over a flawed and classist system, because they managed to surpass the limitations imposed upon them by society and ‘be themselves’. And though this is a heartwarming message to see performed on screen, it’s important to remember that there are more than just the protagonists in the story. Alongside them we have three more characters we must pay close attention to: the Sultan, Jafar and the Genie.

To do a short summary:

The Sultan: Jasmine’s father and the most powerful man in the country, but rather bumbling and childishly naive. As is typical with Disney parents who are still alive by the start of the movie, he is a figure that possesses authority merely in name. Though kind and generally well disposed, he lacks any real power when it comes to the plot of the movie being tricked by both Jafar and Aladdin, as Prince Ali, and ultimately having to rely on the latter to be saved from the former. The Sultan is the quintessential look at a spoiled monarch whose rule is being facilitated by someone more competent than him, and this informs most of his character as a result. He himself might be a doting and benevolent figure, yet his reign is a prosperous one by accident not by his own making.

The Genie: The spirit who resides in the lamp that Aladdin finds in the Cave of Wonders and who becomes his ally in his quest to marry Jasmine. Perhaps one of the most memorable characters in the movie, thanks to the late William Robbins’ performance, Genie's entire quest in the movie is to achieve freedom by helping out his Master. The parallels between him and the indentured servant position are made abundantly clear by the fact that he is bound to Aladdin until the latter agrees to set him free. Genie’s role in the story is one that is important, but his position is one that mirrors Jafar: they are in the service of someone who is less than them, whether it be competence or magical ability. However, while Jafar detests his position and the Sultan, Genie becomes a father figure to the protagonist. The fact that the two exchange places (Jafar is turned into a Genie and imprisoned, Genie being set free and retaining all his powers) stems directly from how they relate to their social class. Jafar is self-serving and ambitious and Genie is altruistic and self-sacrificial. Genie thinks of the happiness of his Master, though he is still displeased by the concept itself, and for that he is rewarded, proving that putting the well-being of others above your interests is the way to happiness after all. That is, if you’re a Disney hero.

Jafar: The Grand Vizier and the second most powerful man in the land, but is a scheming backstabber that plans to take the throne for himself. As one of the most easily recognizable Disney villains, Jafar makes a strong impression through not only his design, but through his philosophy as well. He’s in spite of his high rank, still pretty much a servant, having to ensure that the rule of the Sultan is enacted accordingly. Yet, as an antagonist he makes certain that whatever he does is in his own interest as well. To say that he is ambitious would be an understatement, but what is it that he wants exactly? There is no clear answer, but the closest we can get to is that Jafar wants power.

But wait, you might say. Didn’t Aladdin also want that? Why is only Jafar the villain, if they were both after the same thing?

That is a good question! And the answer to it is yes and no. Though indeed, both Jafar and Aladdin wanted power it was for different purposes. Aladdin wanted it for the sake of overcoming his social limitations and thus becoming a worthy candidate for Jasmine, while Jafar wanted power for power’s sake. The lesson that Aladdin learns is that he shouldn’t have attempted to do that, because it would have never worked out in the way he intended it to. Though Jasmine can bring herself down to his level, he cannot bring himself up to hers since it would disrupt the social system. One cannot rise up to a higher social standing through power alone, they need recognition as well. Which is why marrying Jasmine becomes an important plot point. Jafar, who achieved power through his scheming, still lacks the recognition, which can only be granted through marriage to a royal or someone of higher social standing. He fails to achieve it, because his rise in social ranks did not have a ‘noble’ purpose like Aladdin’s but it merely satisfied his own agenda and needs.

Jafar’s status as a villain is thus due to the fact that in Western media ‘Ambition Is Evil’ is one of the most prevalent tropes. Think of the Becky Sharps, the Slytherins, the Lucifers, the Littlefingers that populate our literature, their evil nature is more often than not tied to their necessity to rise above others.

To reign is worth ambition though in hell;

Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven. (Paradise Lost)

Power corrupts, and ambition corrupts absolutely. Disney characters thus often learn that it is better not to be swayed by power from their role in society for the sake of power, or they will pay the heavy price for doing so. That is why Jafar fails and Genie succeeds, because they related differently to their role in their Master’s lives.

And that is a theme that Twisted Wonderland also touches upon in Jamil’s story. Twisted from Jafar itself it was inevitable that his story would deal with such a topic. However, what deeply impressed me was how self-aware the narrative had been in regards to it.

Ruggie: I feel bad for you. By helping out Kalim you have burned your hands considerably. (R Card School Uniform)

Jamil: I want to avoid standing out. I can’t be satisfied with this. I cannot be too good, nor fall behind, and neither should I get satisfactory grades or fail. This is the best shortcut to success. (SR Card Lab Coat)

Jamil: I am a sworn servant to the house of Asim and thus have a duty to protect the master. (SR Card Ceremony Robes)

Azul: You are always welcome in Octavinelle should you find yourself freed from Kalim. (5-10)

The matter of Jamil’s role as Kalim’s caretaker is one that has been brought up at several points throughout the game. This is usually done with the express purpose of reinforcing his status as his servant, but also to affirm that it is indeed this very position that is preventing him from achieving his full potential.

Azul: If you look at your grades, there are no visible gaps in your classroom lectures, practical skills and physical training. Even I have a weak point when it comes to flying… For you to not even have such an instability is frankly amazing. It is like you can tailor yourself to suit your needs. (SR Card Lab Coat)

Just as Azul remarks Jamil holds himself back on account of his need to perfectly perform a certain persona: the reliable valet. It is a character we often see in media disguised as the Hypercompetent Sidekick or Servile Snarker, who is by his very nature much more accomplished than the master, but must out of financial necessity submit himself to someone else. Or in Jamil’s case, out of filial obligation. And this is where the comparison with Jafar becomes important because while Jamil does embody Jafar’s ambition, it is not treated in the same manner as in the movie. Jamil’s motives for betraying Kamil are similar to the villain: he wants to impose himself upon others and overcome his social position. Having been raised in servitude since young he has been forced to ‘tailor himself’ to the demands and expectations placed upon him. However, because this position has been imposed upon him and it wasn’t of his own volition, Jamil comes to resemble the genie much more than he does Jafar. Which is completely intentional, I believe. But we’ll get to that soon enough.

Taking this into consideration it is interesting to note how the resolution of Jamil’s arc differs from Jafar’s in terms of narrative. The end of Aladdin has us witness the defeat of Jafar at the hands of Aladdin, his imprisonment in the lamp and the release of the genie from his bonds of servitude. It is, of course, a typical Disney happy ending: the villain was defeated by his own hubris, while the heroes prevailed through self-sacrifice and cleverness. The main character has learned the necessary moral lesson (cynically phrased as: do not aspire to overcome your social class through hard work, but wait for recognition from your superiors) and all the characters that aided them during their journey get rewarded as well. It’s the culmination of the Disney formula that selflessness and altruism are the values that separate the heroes from villains, and by extension good from evil. Evil only seeks its own interests, while good works in the interests of others. So what about Jamil?

The end of the Scarabia arc is quite ‘Disney’ to a certain degree: the villain has been exposed, the heroes send to the other end of the ‘world’, they get their second wind, defeat him and live happily ever after. Well, not really. You see, what happens before the heroes go to defeat the antagonist is that Kalim breaks down crying due to Jamil’s betrayal and Azul remarks the following thing:

Azul: Kalim’s gentle disposition towards others is completely different from Jamil and I… No… Taking into account everything, he probably built a grudge over the years. You have been causing trouble for Jamil since you were little, after all. However, you are not in the wrong. You were born a cut above the others. You were loved by everyone around you and we were raised under such a good environment.

You were simply unaware of the greed you’ve been showing. (4-34)

Jamil’s actions aren’t excused, because they are indeed those of a villain: plotting, backstabbing and double-crossing the heroes for his own gains. Yet, they are not simply attributed to his ‘evil’ nature, but rather explained by the environment in which he was raised and the morals that were instilled in him. Jamil is not evil, but rather merely desperate enough to resort to evil means. And that is a profusely important distinction. Though we might commit malicious acts that does not mean that we are malicious by nature, much as committing benevolent acts does not make one irreproachable. And Twisted Wonderland understands this notion: not in the sense that Jamil was right in what he did, but rather than we can understand why he felt like he was pushed to such extremes.

Jamil’s story is one of the more complex ones, in my opinion. It speaks about an issue much deeper and much more insidious than any that have been explored so far in the game. The result is that unlike the other three previous Overblot victims, Jamil has no clear-cut solution to his problem. Even after the incident he is still in the service of the Asim family. Even if Kalim asserts that they are equals at school, he still will remain a servant everywhere else. No matter what he does he is bound to the Asim’s and more specifically to Kalim.

I feel like this would be the note on which I should safely conclude this very long introduction, as we move further and into the real meat of this post: the analysis itself. Thus, without further ado, let’s see why this CM is such a treat from a symbolical and storytelling perspective.

The opening of Aladdin (1992) is perhaps one of my favorites due to the fact that it seeks out to reference its source material: One Thousand and One Nights. By that I mean that it utilizes a technique known as the ‘frame story’: a story which contains within it another story. In the novel the framing device is Scheherezade, the vizier’s daughter who upon learning that she will marry Sultan Shahryar and be promptly killed at dawn, devised a plan to subvert her fate. She would each night begin a tale that would leave the Sultan so enchanted that he postponed her beheading until the next day so she might finish her tale. However, upon finishing the previous story Scheherezade would continue with another one and so on and so on until she eventually managed to avoid death for one thousand and one nights. Hence the name of the collection.