#livia first lady of imperial rome

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

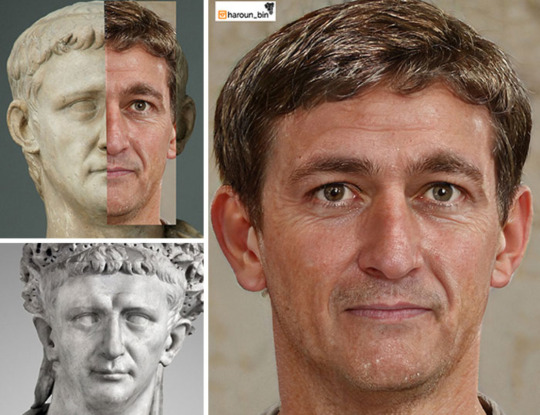

Claudius: The fool of the dynasty.

Claudius was born in Lugdunum, Gaul on August 1, 10 BC. On his mother's side, he was the grandson of the legendary Mark Antony and great-nephew of emperor Augustus. His father was the son of the Empress Livia and brother of emperor Tiberius.

According to historical sources: His sister, Livilla, after hearing an Augur say that her younger brother would be emperor, exclaimed: "May the gods save Rome from such misfortune." His grandmother, Livia, avoided talking to him because "when he was a child, the empress felt uncomfortable seeing and hearing him." During his childhood, the family avoided taking him to public events so as not to be seen. All this drama just because Claudius was lame, stuttered and had a tic.

During the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, that is, for almost his entire life, he was prohibited from holding public office because of his "defects." From a very young age it was determined that he could never be heir to the throne. This was determined by his family but not by his destiny.

Two wives

Year 9 AD: Empress Livia persuaded a close friend and wife of a senator to marry her daughter Plautia Urgulanilla to 18-year-old Claudius.

They had a son, Claudius Drusus, who died at 14 years old when he threw a piece of pear into the air to catch it in his mouth and the piece got stuck in his throat. Years before the son's death Claudius divorced when his brother-in-law, brother of Plautia, murdered her wife by throwing her out of a window.

Year 28: The prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Sejanus, was plotting to seize the throne. In his eagerness to join the imperial family, he had managed to persuade Claudius to marry his sister Aelia Paetina. In 29 they had a daughter, Antonia. In 31 Sejanus's conspiracies and murders were discovered; the Emperor Tiberius sentenced him to death. Claudius divorced Aelia but never abandoned his daughter Antonia.

Year 37: Interestingly his nephew "the mad emperor Caligula" was the first of the family to see that nothing prevents Claudius from holding an important position. Claudius at age of 46 was appointed consul. Months later, on the same year, his mother Antonia the Younger passed away.

Third wife

In the year 38, Claudius married a young woman member of the dynasty. On her mother's side, Messalina was the granddaughter of Antonia the Elder, Claudius' aunt, and on her father's side, the granddaughter of Claudia Marcella Minor, one of the daughters that Augustus' sister Octavia (Claudius' grandmother) had from her first marriage. Claudius was also forbidden to marry a member of the dynasty, but was able to do so during the reign of his nephew.

It should be noted that the story of Messalina as a nymphomaniac and promiscuous lady was a creation of Agrippina the Younger, written after Messalina's death. The hatred between the two women was legendary. Roman historians such as Suetonius and Tacitus relied on the writings of Agrippina, but there was only one publicly confirmed adultery and it was more an attempt by Messalina to secure her power and especially the future of her son than a matter of love or passion.

The less thought day

On January 24, 41, the emperor was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard in collusion with several senators. Minutes later, the emperor's wife and daughter were also murdered.

And what no one would have thought possible happened: At the age of 50 Claudius became Caesar. The fourth emperor of Rome.

According to the historians Flavius Josephus and Cassius Dion, Claudius, terrified, thinking that the senators' plan was to exterminate all the members of the imperial family to restore the republic, hid behind a curtain. A Praetorian soldier found him and immediately proclaimed him emperor because he was the only male in the dynasty who could rule, the other remaining member being his 3-year-old grandnephew Lucio Domitius, whom 9 years later Claudio himself would give the famous name Nero.

Upon ascending to the throne, he deified his grandmother, Empress Livia. Also named his deceased mother Augusta and designated her birth date- January 31- as a feast day in Rome.

Claudius the Conquer

Claudius surprised Rome by proving to be not only an intelligent emperor but also a conqueror who would make the empire greater. In 43, Claudius begins the campaign to conquer Britannia. Circa 50 the Romans founded the city Londinium /London.

Although this was his most famous conquest and territorial expansion, it was not the only one. Noricum: Present-day central Austria (west of Vienna), part of Bavaria (Germany), northeastern Slovenia, and part of the Italian Alps. Thrace (Bulgaria), and he made the Danube River a new border of the Roman Empire.

Claudius the Emperor

His reign was characterized by economic and military prosperity.

He distinguished himself for his policy of Meritocracy. He rewarded for ability , not for personal sympathies. He allowed men from of non-aristocratic origin access to the Senate. Among those who benefited for their merits and not for their lineage was Vespasian, who years later became emperor (69-79)

Claudius gained the respect of the Senate, the army and the people at the same time, something that had not been seen in Rome since the time of Augustus.

He had two children with his third wife: Octavia, born late year 39, and Tiberius Claudius, later nicknamed Britanicus due the conquest of Britannia, born 19 days after Claudius' accession to the throne.

He wrote many works, most during the reign of Tiberius. In addition to a history of the reign of Augustus and some treatises on the game of dice, his great passion, among his main works are a History of Etruscan civilization in twenty books, a History of Carthage in eight volumes, and a dictionary of the Etruscan language.

Unfortunately all of his works have been lost, but we know of them through the writings of others who mention them in detail.

Pliny the Elder refers to Claudius as "One of the best writers of Rome". Evidently, Claudius learned a lot from his teacher Titus Livius (Livy), author of the Ab Urbe Condita known as History of Rome.

In 47, Claudius celebrated the Ludi Saeculares , a religious and festive celebration, marking a kind of 'New Age' and only held every 110 years. Claudius used these games and ceremonies to commemorate the eighth centenary of the founding of Rome in 48. This was the first time that the founding of Rome was commemorated with a special ceremony. The celebration would be held for the second time in 148 under the reign of Antoninus Pius.

Claudius also had the honour of extending the Pomerium, the sacred boundary of the city of Rome, a custom instituted by Romulus. The Romans believed that for every large territory conquered, the city of Rome became larger and they should extend the Pomerium. Few Roman rulers were able to do this and among them is Claudius.

Inscription commemorating the extension of the Pomerium of Rome by Claudius inserted in a wall of the via delle Banchi Vecchi in Rome (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

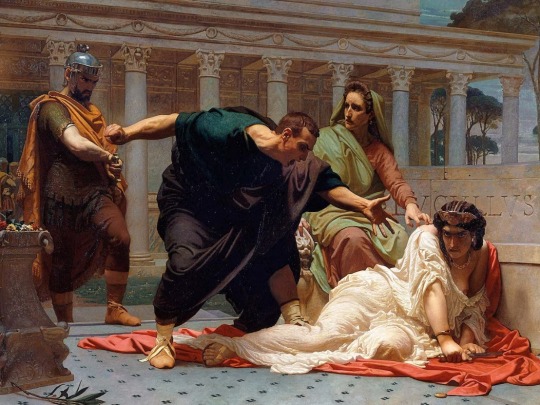

The tragic end of Messalina

Messalina becomes the lover of Senator Gaius Silius. Taking advantage of her lineage as a woman of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, she convinced that man that together they could take the throne from Claudius.

In 48, while Claudius was in Ostia, Messalina divorced him and married Silius. Three freedmen arrived in Ostia to give the incredible news to the emperor.

According to Tacitus: "Claudius, having returned to the palace, ordered that Messalina be brought to him, but the freedman Narcissus, fearing that the emperor would forgive her, ordered a freedman, a centurion, and some tribunes to proceed with the execution. The woman was overtaken in the gardens and executed; informed of his wife's death while he was at the table, Claudio would not have asked any more questions."

The senator and his group of accomplices and supporters were also executed.

Seven years earlier: Claudius ordered the return of his nieces, daughters of his deceased brother Germanicus:, Livilla and Agrippina the Younger, both exiled by Caligula in 39. Livilla was highly favored by Claudius, and Agrippina the Younger was beloved by the people. This situation caused Messalina worry and jealousy.

Messalina, through intrigue, in a very short time managed to send Livilla back into exile, along with the philosopher Seneca -a close friend and ally of Agrippina the Younger- accusing them of being lovers and conspiring. Livilla died in exile shortly after arriving.

Livilla was just one of the first victims of Messalina's intrigues. Another victim of the family was another niece of Emperor: Julia Livia, the only surviving daughter of Claudia Livia, known as Livilla (sister of Claudius) and Drusus the Younger (son of Tiberius). According to historians, an agent of the Empress, Valeria Messalina, falsely accused Julia of incest and immorality. Julia took her own life before being executed.

But Messalina could not make Claudius' other niece disappear: Agrippina the Younger, who was extremely cunning and more dangerous because she had a son, that is, a candidate for the throne who, to make matters worse, he had more blue blood than Britannicus. In all likelihood, this could be the reason Messalina attempted to overthrow Claudius.

An unusual marriage

If Senator Gaius Silius was able to use Messalina's lineage to try to overthrow Claudius by marrying her, what could another do who marries the widow Agrippina, a direct descendant of Divine Augustus? This was the reason for Claudio's incredible decision to marry his niece: simply so that no other man could marry her. Agrippina immediately accepted the proposal to become empress of Rome.

The marriage between a man and his first-degree niece was considered incest and a crime in Rome. However, this was not an incestuous relationship but a political union; Even so, Claudius had to present dispensations to the Senate and the religious authorities, and there were endless ceremonies in order to marry his niece.

Finally, in the year 49, in an unprecedented event in Roman history, the Emperor married his own niece. Immediately Agrippina gets Claudius to bring her close friend Seneca from exile, and orders the remains of her exiled sister to be brought to be cremated in an honorable funeral and the urn placed in the mausoleum of Augustus. Agrippina appoints Seneca as her son's tutor and teacher. Claudius granted Agrippina the title of Augusta.

In 50 Claudius adopted his great-nephew Lucius as his son, changed his name to Nero Claudius, and named him his successor instead Emperor's own son. Some historians suggest that this was one of the many conditions that Agrippina imposed in order to marry him, while Claudius in turn imposed the condition that his daughter Octavia marry Nero.

At that time Nero and Octavia are around 14 and 12 years old respectively. Claudius must have believed that from this marriage a grandson would become emperor, since it could not be his own son. But that would never happen, and Claudius unwittingly condemned his daughter to a tragic fate.

The death

In October 13 of 54, at age 64, the emperor Claudius died during a banquet, after having eaten poisoned mushrooms, according to Juvenal's version.

There are several versions about his death, however they all agree on the theory that the emperor was poisoned. Personally, I want to believe that his death was due to natural causes. The life story of this emperor is extraordinary, it does not deserve such a poor ending.

Below, a text that is not mine but from a very important site with an extensive article on Emperor Claudius. I copy and paste the final part that I was happy to read.

However, as Levick points out, those present at the banquet do not seem to have suspected poisoning of any sort; moreover, the eunuch Halotus, whose job was to taste the Emperor's food, kept his job when Nero assumed the throne—evidence that nobody wanted to put him out of the way, either as an accomplice or as a witness to assassination. We see no reason to believe that Claudius was murdered. All the features are consistent with sudden death from cerebrovascular disease, which was common in Roman times. Towards the end of 52 AD, at the age of 62, Claudius had a serious illness and spoke of approaching death. Around that time there were changes in his depiction in busts, cameos and coins—with thick neck, narrow shoulders and flat chest. The Apocolocyntosis, addressed to an audience some of whom were present at the death, makes clear that there is no need to postulate poisoning, accidental or otherwise.

Text : © 2002, The Royal Society of Medicine.

The Divine Claudius

Sculpture of Claudius deified (1st Century) Vatican Museums.

After his death, like Augustus, he was deified.

The boy who everyone said could never achieve anything became a great writer, emperor, conqueror, and also a god.

229 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was wondering if you hav any shows/book recommendations on Livia/her family. After watching Domina I wanted to read/watch more on them!

hi! yes, i'd be glad to give some recommendations!

in terms of shows, there aren't many out there, unfortunately. the only one i can think of is rome hbo and that only really touches on augustus' life before the fall of the republic and his side of the family so if you're interested in learning more about augustus, agrippa and octavia, that would be a good show to watch!

there's also i claudius (which is also a novel) but i really don't recommend it. it's literally just one long character assassination of livia <3

now for books, here's a few i would recommend:

livia: first lady of imperial rome by anthony barrett --> this book does a good job of not only studying livia's life but also explaining some of the takes that ancient writers had about her and some of the rumors/theories that surround different events in her life. this book is a bit old so bear that in mind when reading

dynasty: the rise and fall of the house of caesar by tom holland --> one of my favorites! it does a great job of analyzing the julio-claudians' place in history in a compelling fashion!

domina: the women who made imperial rome: guy de la bedoyere --> one of my favorites! this book goes beyond the scope of livia and her immediate female relatives but the parts discussing livia, octavia and the agrippinas were great! my only complaint is that i wish it had been longer!

The First Ladies of Rome: The Women Behind the Caesars by Annelise Freisenbruch --> Another great book similar in focus to the title above!

Roman Women: The Women Who Influenced the History of Rome by Paul Chrystal --> Okay I really dislike this book but if you want to learn more about the place of women within roman society, this would be a good read! I read it to learn more about influential women in Rome and was disappointed because I wasn't looking for that more generalistic perspective

Hope these recs help <3

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faustina's Marble Origins (supposedly...)

"Eccme... Salve... sum problema! Eccme!

Title:

Portrait of Faustina the Elder

Artist/Maker:

Unknown

Date:

A.D. 140–160

Medium:

Marble

Dimensions:

209 × 78 × 55 cm (82 5/16 × 30 11/16 × 21 5/8 in.)

Place:

Roman Empire (Place Created)

Culture:

Roman

Object Number:

70.AA.113

Credit Line:

Gift of J. Paul Getty

Inscription(s):

Inscription (modern): FAUSTINA SENIOR ("Faustina the Elder")

Alternate Titles:

Faustina the Elder (Alternate Title)

Department:

Antiquities

Classification:

Sculpture

Object Type:

Female portrait

Since there is no description of Faustina’s appearance, we have no idea if her portraits bear any close relationship to the way she really looked. There must have been an attempt to prompt an immediate identification between her actual appearances in public (if only for a few years, and later as effigies seen from a distance) and her artistic representations. However, the mechanical reproduction of imperial portraits warns against seeing them as direct imitations.

The administration in Rome sent out miniature templates of her profile for the die-cutters of coins and medals and models for sculptors and painters. The copying of these models in the provinces produced series of nearly identical Faustina portraits on conventional body types established by the first augusta, Livia, a century and a half before. Although the carved body is now lost and the original placement of the sculpture is unknown, the commanding presence of the princeps femina (first among women) persists, just as it was meant to, “in eternity.”

As for Faustina the Elder’s character, very little was written about her life, but like queens and empresses before her and leading ladies long after, suspicions were raised about her. As Antoninus’s image-makers would have it, Faustina was the ideal Roman woman—dignified, cultivated, and virtuous—eminently worthy of emulation.This particular statue is probably supposed to emulate the goddess, Ceres. There would have been wheat in her right hand.

Since this statue is likely a later copy or reproduction and modeled after Livia and Ceres, this would have been a fairly common body to reproduce. The hood suggests that the head is not removable - it would not have been interchanged for a different lady. There is no specific identification of the marble or where it was found. I am going to imagine that the statue was commissioned by her husband for members of her cult and the marble is from close to Rome, likely Carrara. It would have had to be transported on a cart across land.

1730 - first identification of statue

Thomas Herbert, 8th earl of Pembroke, 5th earl of MontgomeryEnglish, 1656 - 1733 (Wilton House, Wiltshire, England)

by inheritance to his son, Henry Herbert, 1733.

0 notes

Text

“...If any precedent might have preoccupied Livia, especially in her early career, when she was attempting to mould an image fitting for the times, it would have been a negative one, provided by the most notorious woman of the late republic and, most important, a woman who clashed headlong with Octavian in the sensitive early stages of his career. Fulvia was the wife of Mark Antony, and his devoted supporter, no less loyal than Livia in support of her husband, although their styles were dramatically different.

Fulvia’s struggle on behalf of Antony, Octavian’s archenemy, has secured her an unenviable place in history as a power-crazed termagant. While her husband was occupied in the East in 41, Fulvia made an appearance, along with Antony’s children, before his old soldiers in Italy, urging them to remain true to their commander. When Antony’s brother Lucius gathered his troops at Praeneste to launch an attack on Rome, Fulvia joined him there, and the legend became firmly established that she put on a sword, issued the watchword, gave a rousing speech to the soldiers, and held councils of war with senators and knights. This was the ultimate sin in a woman, interfering in the loyalty of the troops.

In the end Octavian prevailed and forced the surrender of Lucius and his armies at Perusia. The fall of the city led to a massive exodus of political refugees. Among them were two women, Livia and Fulvia. Livia joined her husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero, who escaped first to Praeneste and then to Naples. Fulvia fled with her children to join Antony and his mother in Athens. Like Octavia later, she found that her dedicated service was not enough to earn her husband’s gratitude. In fact, Antony blamed her for the setbacks in Italy.

A broken woman, she fell ill at Sicyon on the Gulf of Corinth, where she died in mid-40 bc. Antony in the meantime had left Italy without even troubling himself to visit her sickbed. Fulvia’s story contains many of the ingredients familiar in the profiles of ambitious women: avarice, cruelty, promiscuity, suborning of troops, and the ultimate ingratitude of the men for whom they made such sacrifices. She was at Perusia at the same time as Livia, and as wives of two of the triumvirs, they would almost certainly have met. In any case, Fulvia was at the height of her activities in the years immediately preceding Livia’s first meeting with Octavian, and at the very least would have been known to her by reputation. Livia would have seen in Fulvia an object lesson for what was to be avoided at all costs by any woman who hoped to survive and prosper amidst the complex machinations of Roman political life.

In one respect Livia’s career did resemble Fulvia’s, in that it was shaped essentially by the needs of her husband, to fill a role that in a sense he created for her. To understand that role in Livia’s case, we need to understand one very powerful principle that motivated Augustus throughout his career. The importance that he placed in the calling that he inherited in 44 bc cannot be overstressed. The notion that he and the house he created were destined by fate to carry out Rome’s foreordained mission lay at the heart of his principate. Strictly speaking, the expression domus Augusta (house of Augustus) cannot be attested before Augustus’ death and the accession of Tiberius, but there can be little doubt that the concept of his domus occupying a special and indeed unique place within the state evolves much earlier.

Suetonius speaks of Augustus’ consciousness of the domus suae maiestas (the dignity of his house) in a context that suggests a fairly early stage of his reign, and Macrobius relates the anecdote of his claiming to have had two troublesome daughters, Julia and Rome. When Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae in 2 bc, Valerius Messala spoke on behalf of the Senate, declaring the hope that the occasion would bring good fortune and favour on ‘‘you and your house, Augustus Caesar’’ (quod bonum, inquit, faustum sit tibi domuique tuae, Caesar Auguste).

The special place in the Augustan scheme enjoyed by the male members of this domus placed them in extremely sensitive positions. The position of the women in his house was even more challenging. In fashioning the image of the domus Augusta, the first princeps was anxious to project an image of modesty and simplicity, to stress that in spite of his extraordinary constitutional position, he and his family lived as ordinary Romans. Accordingly, his demeanour was deliberately self-effacing.

His dinner parties were hospitable but not lavish. The private quarters of his home, though not as modest as he liked to pretend, were provided with very simple furniture. His couches and tables were still on public display in the time of Suetonius, who commented that they were not fine enough even for an ordinary Roman, let alone an emperor. Augustus wore simple clothes in the home, which were supposedly made by Livia or other women of his household. He slept on a simply furnished bed. His own plain and unaffected lifestyle determined also how the imperial women should behave.

His views on this subject were deeply conservative. He felt that it was the duty of the husband to ensure that his wife always conducted herself appropriately. He ended the custom of men and women sitting together at the games, requiring females (with the exception of the Vestals) to view from the upper seats only. His legates were expected to visit their wives only during the winter season. In his own domestic circle he insisted that the women should exhibit a traditional domesticity.

He had been devoted to his mother and his sister, Octavia, and when they died he allowed them special honours. But at least in the case of Octavia, he kept the honours limited and even blocked some of the distinctions voted her by the Senate. Nor did he limit himself to matters of ‘‘lifestyle.’’ He forbade the women of his family from saying anything that could not be said openly and recorded in the daybook of the imperial household. In the eyes of the world, Livia succeeded in carrying out her role of model wife to perfection. To some degree she owed her success to circumstances. It is instructive to compare her situation with that of other women of the imperial house.

Julia (born 39 bc) summed up her own attitude perfectly when taken to task for her extravagant behaviour and told to conform more closely to Augustus’ simple tastes. She responded that he could forget that he was Augustus, but she could not forget that she was Augustus’ daughter. Julia’s daughter, the elder Agrippina (born 19 bc?), like her mother before her, saw for herself a key element in her grandfather’s dynastic scheme. She was married to the popular Germanicus and had no doubt that in the fullness of time she would provide a princeps of Augustan blood.

Not surprisingly, she became convinced that she had a fundamental role to play in Rome’s future, and she bitterly resented Tiberius’ elevation. Her daughter Agrippina the Younger (born ad 15?) was, as a child, indoctrinated by her mother to see herself as the destined transmitter of Augustus’ blood, and her whole adult life was devoted to fulfilling her mother’s frustrated mission. From birth these women would have known of no life other than one of dynastic entitlement. By contrast, Livia’s background, although far from humble, was not exceptional for a woman of her class, and she did not enter her novel situation with inherited baggage.

As a Claudian she may no doubt have been brought up to display a certain hauteur, but she would not have anticipated a special role in the state. As a member of a distinguished republican family, she would have hoped at most for a ‘‘good’’ marriage to a man who could aspire to property and prestige, perhaps at best able to exercise a marginal influence on events through a husband in a high but temporary magistracy. Powerful women who served their apprenticeships during the republic reached their eminence by their own inclinations, energies, and ambitions, not because they felt they had fallen heir to it.

However lofty Livia’s station after 27 bc, her earlier life would have enabled her to maintain a proper perspective. She did not find herself in the position of an imperial wife who through her marriage finds herself overnight catapulted into an ambience of power and privilege. Whatever ambitions she may have entertained in her first husband, she was sadly disappointed. When she married for the second time, Octavian, for all his prominence, did not then occupy the undisputed place at the centre of the Roman world that was to come to him later. Livia thus had a decade or so of married life before she found herself married to a princeps, in a process that offered time for her to become acclimatised and to establish a style and timing appropriate to her situation.

It must have helped that in their personal relations she and her husband seem to have been a devoted couple, whose marriage remained firm for more than half a century. For all his general cynicism, Suetonius concedes that after Augustus married Livia, he loved and esteemed her unice et perservanter (right to the end, with no rival). In his correspondence Augustus addressed his wife affectionately as mea Livia.

The one shadow on their happiness would have been that they had no children together. Livia did conceive, but the baby was stillborn. Augustus knew that he could produce children, as did she, and Pliny cites them as an example of a couple who are sterile together but had children from other unions. By the normal standards obtaining in Rome at the time they would have divorced—such a procedure would have involved no disgrace—and it is a testimony to the depth of their feelings that they stayed together. In a sense, then, Livia was lucky.

That said, she did suffer one disadvantage, in that when the principate was established, she found herself, as did all Romans, in an unparalleled situation, with no precedent to guide her. She was the first ‘‘first lady’’—she had to establish the model to emulate, and later imperial wives would to no small degree be judged implicitly by comparison to her. Her success in masking her keen political instincts and subordinating them to an image of self-restraint and discretion was to a considerable degree her own achievement.

In a famous passage of Suetonius, we are told that Caligula’s favourite expression for his great-grandmother was Ulixes stolatus (Ulysses in a stola). The allusion appears in a section that supposedly illustrates Caligula’s disdain for his relatives. But his allusion to Livia is surely a witty and ironical expression of admiration. Ulysses is a familiar Homeric hero, who in the Iliad and Odyssey displays the usual heroic qualities of nerve and courage, but is above all polymetis: clever, crafty, ingenious, a man who will often sort his way through a crisis not by the usual heroic bravado but by outsmarting his opponents, whether the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, or the enchantress Circe, or the suitors for Penelope.

Caligula implied that Livia had the clever, subtle kind of mind that one associates with Greeks rather than Romans, who were inclined to take a head-on approach to problems. But at the same time she manifested a particularly Roman quality. Rolfe, in the Loeb translation of Suetonius’ Life of Caligula, rendered the phrase as ‘‘Ulysses in petticoats’’ to suggest a female version of the Homeric character. But this is to rob Caligula’s sobriquet of much of its force.

The stola was essentially the female equivalent of the toga worn by Roman men. A long woollen sleeveless dress, of heavy fabric, it was normally worn over a tunic. In shape it could be likened to a modern slip, but of much heavier material, so that it could hang in deep folds. The mark of matronae married to Roman citizens, the stola is used by Cicero as a metaphor for a stable and respectable marriage. Along with the woollen bands that the matron wore in her hair to protect her from impurity, it was considered the insigne pudoris (the sign of purity) by Ovid, something, as he puts it, alien to the world of the philandering lover.

Another contemporary of Livia’s, Valerius Maximus, notes that if a matrona was called into court, her accuser could not physically touch her, in order that the stola might remain inviolata manus alienae tactu (unviolated by the touch of another’s hand). Bartman may be right in suggesting that the existence of statues of Livia in a stola would have given Caligula’s quip a special resonance, but that alone would not have inspired his bon mot. To Caligula’s eyes, Livia was possessed of a sharp and clever mind.

But she did not allow this quality to obtrude because she recognised that many Romans would not find it appealing; she cloaked it with all the sober dignity and propriety, the gravitas, that the Romans admired in themselves and saw represented in the stola. Livia’s greatest skill perhaps lay in the recognition that the women of the imperial household were called to walk a fine line. She and other imperial women found themselves in a paradoxical position in that they were required to set an example of the traditional domestic woman yet were obliged by circumstances to play a public role outside the home—a reflection of the process by which the domestic and public domains of the domus Augusta were blurred.

Thus she was expected to display the grand dignity expected of a person very much in the public eye, combined with the old-fashioned modesty of a woman whose interests were confined to the domus. Paradoxically, she had less freedom of action than other upper-class women who had involved themselves in public life in support of their family and protégés. As wife of the princeps, Livia recognised that to enlist the support of her husband was in a sense to enlist the support of the state.

That she managed to gain a reputation as a generous patron and protector and, at the same time, a woman who kept within her proper bounds, is testimony to her keen sensitivity. In many ways she succeeds in moving silently though Rome’s history, and this is what she intended. Her general conduct gave reassurance to those who were distressed by the changing relationships that women like Fulvia had symbolised in the late republic. It is striking that court poets, who reflected the broad wishes of their patron, avoid reference to her. She is mentioned by the poet Horace, but only once, and even there she is not named directly but referred to allusively as unico gaudens mulier marito (a wife finding joy in her preeminent husband).

The single exception is Ovid, but most of his allusions come from his period of exile, when desperation may have got the better of discretion. The dignified behaviour of Livia’s distinguished entourage was contrasted with the wild conduct of Julia’s friends at public shows, which drove Augustus to remonstrate with his daughter (her response: when she was old, she too would have old friends). In a telling passage Seneca compares the conduct of Livia favourably with even the universally admired Octavia. After losing Marcellus, Octavia abandoned herself to her grief and became obsessed with the memory of her dead son. She would not permit anyone to mention his name in her presence and remained inconsolable, allowing herself to become totally secluded and maintaining the garb of mourning until her death.

By contrast, Livia, similarly devastated by the death of Drusus, did not offend others by grieving excessively once the body had been committed to the tomb. When the grief was at its worst, she turned to the philosopher Areus for help. Seneca re-creates Areus’ advice. Much of it, of course, may well have sprung from Seneca’s imagination, but it is still valuable in showing how Livia was seen by Romans of Seneca’s time. Areus says that Livia had been at great pains to ensure that no one would find anything in her to criticise, in major matters but also in the most insignificant trifles. He admired the fact that someone of her high station was often willing to bestow pardon on others but sought pardon for nothing in herself.

…Perhaps most important, it was essential for Livia to present herself to the world as the model of chastity. Apart from the normal demands placed on the wife of a member of the Roman nobility, she faced a particular set of circumstances that were unique to her. One of the domestic priorities undertaken by Augustus was the enactment of a programme of social legislation. Parts of this may well have been begun before his eastern trip, perhaps as early as 28 bc, but the main body of the work was initiated in 18.

A proper understanding of the measures that he carried out under this general heading eludes us. The family name of Julius was attached to the laws, and thus they are difficult to distinguish from those enacted by Julius Caesar. But clearly in general terms the legislation was intended to restore traditional Roman gravitas, to stamp out corruption, to define the social orders, and to encourage the involvement of the upper classes in state affairs. The drop in the numbers of the upper classes was causing particular concern. The nobles were showing a general reluctance to marry and, when married, an unwillingness to have children. It was hoped that the new laws would to some degree counter this trend.

The Lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis, passed probably in 18 bc, made adultery a public crime and established a new criminal court for sexual offences. The Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus, passed about the same time, regulated the validity of marriages between social classes. The crucial factor here, of course, was not the regulation of morality but rather the legitimacy of children. Disabilities were imposed on the principle that it was the duty of men between twenty-five and sixty-five and women between twenty and fifty to marry. Those who refused to comply or who married and remained childless suffered penalties, the chief one being the right to inherit. The number of a man’s children gave him precedence when he stood for office.

Of particular relevance to Livia was the ius trium liberorum, under which a freeborn woman with three children was exempted from tutela (guardianship) and had a right of succession to the inheritance of her children. Livia was later granted this privilege despite having borne only two living children. This social legislation created considerable resentment—Suetonius says that the equestrians staged demonstrations at theatres and at the games. It was amended in ad 9 and supplemented by the Lex Papia Poppaea, which seems to have removed the unfair distinctions between the childless and the unmarried and allowed divorced or widowed women a longer period before they remarried.

Dio, apparently without a trace of irony, reports that this last piece of legislation was introduced by two consuls who were not only childless but unmarried, thus proving the need for the legislation. Livia’s moral conduct would thus be dictated not only by the already unreal standards that were expected of a Roman matrona but also by the political imperative of her husband’s social legislation. Because Augustus saw himself as a man on a crusade to restore what he considered to be old-fashioned morality, it was clearly essential that he have a wife whose reputation for virtue was unsullied and who could provide an exemplar in her own married life.

In this Livia would not fail him. The skilful creation of an image of purity and marital fidelity was more than a vindication of her personal standards. It was very much a public statement of support for what her husband was trying to achieve. Tacitus, in his obituary notice that begins Book V of the Annals, observes that in the matter of the sanctitas domus, Livia’s conduct was of the ‘‘old school’’ ( priscum ad morem). This is a profoundly interesting statement at more than one level. It tells us something about the way the Romans idealised their past. But it also says much about the clever way that Livia fashioned her own image.

Her inner private life is a secret that she has taken with her to the tomb. She may well have been as pure as people believed. But for a woman who occupied the centre of attention in imperial Rome for as long as she did, to keep her moral reputation intact required more than mere proper conduct. Rumours and innuendo attached themselves to the powerful and prominent almost of their own volition. An unsullied name required the positive creation of a public image. Livia was despised by Tacitus, who does not hesitate to insinuate the darkest interpretations that can be placed on her conduct.

Yet not even he hints at any kind of moral impropriety in the narrow sexual sense. Even though she abandoned her first husband, Tiberius Claudius, to begin an affair with her lover Octavian, she seems to have escaped any censure over her conduct. This is evidence not so much of moral probity as of political skill in managing an image skilfully and effectively. None of the ancient sources challenges the portrait of the moral paragon. Ovid extols her sexual purity in the most fulsome of terms. To him, Livia is the Vesta of chaste matrons, who has the morals of Juno and is an exemplar of pudicitia worthy of earlier and morally superior generations. Even after her husband is dead she keeps the marriage couch (pulvinar) pure. (She was, admittedly in her seventies.)

Valerius Maximus, writing in the Tiberian period, can state that Pudicitia attends the couch of Livia. And the Consolatio ad Liviam, probably not a contemporary work but one at least that tries to reflect contemporary attitudes, speaks of her as worthy of those women who lived in a golden age, and as someone who kept her heart uncorrupted by the evil of her times. Horace’s description is particularly interesting. His phrase unico gaudens marito is nicely ambiguous, for it states that Livia’s husband was preeminent (unicus) but implies the other connotation of the word: that she had the moral superiority of an univira, a woman who has known only one husband, which in reality did not apply to Livia.

Such remarks might, of course, be put down to cringing flattery, but it is striking that not a single source contradicts them. On this one issue, Livia did not hesitate to blow her own trumpet, and she herself asserted that she was able to influence Augustus to some degree because she was scrupulously chaste. She could do so in a way that might even suggest a light touch of humour. Thus when she came across some naked men who stood to be punished for being exposed to the imperial eyes, she asserted that to a chaste woman a naked man was no more a sex object than was a statue. Most strikingly, Dio is able to recount this story with no consciousness of irony.

Seneca called Livia a maxima femina. But did she hold any real power outside the home? According to Dio, Livia believed that she did not, and claimed that her influence over Augustus lay in her willingness to concede whatever he wished, not meddling in his business, and pretending not to be aware of any of his sexual affairs. Tacitus reflects this when he calls her an uxor facilis (accommodating wife). She clearly understood that to achieve any objective she had to avoid any overt conflict with her husband.

It would do a disservice to Livia, however, to create the impression that she was successful simply because she yielded. She was a skilful tactician who knew how to manipulate people, often by identifying their weaknesses or ambitions, and she knew how to conceal her own feelings when the occasion demanded: cum artibus mariti, simulatione filii bene composita (well suited to the craft of her husband and the insincerity of her son) is how Tacitus morosely characterises that talent. Augustus felt that he controlled her, and she doubtless was happy for him to think so.

Dio has preserved an account of a telling exchange between Augustus and a group of senators. When they asked him to introduce legislation to control what was seen as the dissolute moral behaviour of Romans, he told them that there were aspects of human behaviour that could not be regulated. He advised them to do what he did, and have more control over their wives. When the senators heard this they were surprised, to say the least, and pressed Augustus with more questions to find out how he was able to control Livia. He confined himself to some general comments about dress and conduct in public, and seems to have been oblivious to his audience’s scepticism.

What is especially revealing about this incident is that the senators were fully aware of the power of Livia’s personality, but recognised that she conducted herself in such a way that Augustus obviously felt no threat whatsoever to his authority. Augustus would have been sensitive to the need to draw a line between Livia’s traditional and proper power within the domus and her role in matters of state. This would have been very difficult. Women in the past had sought to influence their husbands in family concerns. But with the emergence of the domus Augusta, family concerns and state concerns were now inextricably bound together.

…Although Livia did not intrude in matters that were strictly within Augustus’ domain, her restraint naturally did not bar communication with her husband. Certainly, Augustus was prepared to listen to her. That their conversations were not casual matters and were taken seriously by him is demonstrated by the evidence of Suetonius that Augustus treated her just as he would an important official. When dealing with a significant item of business, he would write things out beforehand and read out to her from a notebook, because he could not be sure to get it just right if he spoke extemporaneously. Moreover, it says something about Livia that she filed all Augustus’ written communications with her.

After his death, during a dispute with her son, she angrily brought the letters from the shrine where they had been archived and read them out, complete with their criticisms of Tiberius’ arrogance. Despite Tacitus’ claim that Livia controlled her husband, Augustus was willing to state publicly that he had decided not to follow her advice, as when he declined special status to the people of Samos. Clearly, he would try to do so tactfully and diplomatically, expressing his regrets at having to refuse her request. On other issues he similarly reached his own decision but made sufficient concessions to Livia to satisfy her public dignity and perhaps Augustus’ domestic serenity.

On one occasion Livia interceded on behalf of a Gaul, requesting that he be granted citizenship. To Augustus the Roman citizenship was something almost sacred, not to be granted on a whim. He declined to honour the request. But he did make a major and telling concession. One of the great advantages of citizenship was the exemption from the tax (tributum) that tributary provincials had to pay. Augustus granted the man this exemption. When Livia apparently sought the recall of Tiberius from Rhodes after the Julia scandal, Augustus refused, but did concede him the title of legatus to conceal any lingering sense of disgrace.

He was unwilling to promote Claudius to the degree that Livia wished, but he was willing to allow him some limited responsibilities. Thus he was clearly prepared to go out of his way to accede at least partially to his wife’s requests. But on the essential issues he remained very much his own man, and on one occasion he made it clear that as an advisor she did not occupy the top spot in the hierarchy. In ad 2 Tiberius made a second request to return from exile. His mother is said to have argued intensively on his behalf but did not persuade her husband. He did, however, say that he would be willing to be guided by the advice he received from his grandson, and adopted son, Gaius.”

- Anthony A. Barrett, “Wife of the Emperor.” in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome

#livia drusilla#livia first lady of imperial rome#octavian#fulvia#history#roman#ancient#anthony a. barrett

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drusus was universally liked, and his death at the age of twenty-nine could not seriously be seen as benefitting anyone. Nevertheless, it still managed to attract gossip and rumors. The death of a young prince of the imperial house would usually drag in the name of Livia as the prime suspect. In this instance such scenario would have been totally implausible and Augustus became the target of the innouendo instead. Tacitus reports that the tragedy evoked the same jaundiced reactions as would that of Germanicus, three decades later, in the reign of Tiberius, that sons with "democratic" temperaments - civilia ingenia- did not please ruling fathers ( Germanicus had been adopted by Tiberius). Suetonius has preserved a tradition that Augustus, suspecting Drusus of republicanism, had recalled him from his province, and when he declined to obey, he had him poisoned. Suegonius thought the suggestion nonsensical, and he is surely correct. Augustus had shown great affection for the young man and the Senate had named him joint heir with Gaius and Lucius. He also delivered a warm eulogy after his death.

About Augustus and Drusus from "Livia: first lady of the imperial Rome" by Anthony A. Barrett.

#julio claudii#Augustus#drusus the elder#roman empire#tagamemnon#livia: first lady of imperial rome#anthony a barrett

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gaius Octavius + Livia Drusilla: Affair, Betrothal and Marriage:

If Livia has been correctly identified as the mistress who was the target of Scribonia’s complaints, Octavian and Livia began an affair while he was still married to Scribonia. He waited for the birth of his daughter Julia, then immediately arranged a divorce. Livia for her part secured a divorce from Tiberius Nero in turn, and it is likely that in late September or early October, 39 bc, Octavian and Livia became betrothed. They do not seem to have proceeded immediately to the marriage, probably because by early October, Livia was six months pregnant. - Livia: First lady of Imperial Rome, Anthony B. Barrett.

Where Livia was concerned, Octavian was determined to let nothing stand in his way. He met her very soon after her return to Rome; indeed, she may have been introduced to him by Scribonia. He quickly made up his mind to marry her, and she decided equally quickly to say yes. Tiberius complaisantly agreed to a divorce. It is likely that, soon after the depositio barbae**, in late September or early October, Octavian and Livia became engaged. The couple paused before translating their engagement into marriage. The problem was Livia’s unborn child by Tiberius. Octavian went to consult the appropriate religious authority, the pontifices: could he marry Livia while she was pregnant?[...]The pontifices offered their seal of approval and it seems that Livia now moved in with Octavian in his house on the Palatine. However, the wedding did not take place until after the birth of her second child, who was born on January 14 and given the praenomen Drusus.[...]Octavian’s marriage [to Livia] is the first occasion for which we have evidence when he gave priority to his feelings. - Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Emperor, Anthony Everitt.

** “[...]Being prone to devise a ritual for almost every aspect of daily life, the Romans made a ceremony of their first shave—the depositio barbae, which in most cases took place about the time a boy came of age, usually at sixteen or seventeen. Octavian made a great to-do over the ceremony, throwing a magnificent party and paying for a public festival. The event could be seen as a statement that, with the arrival of peace, the “boy who owed everything to his name” had attained his political as well as physical maturity. But it was whispered that his true motive was to please Livia.”

#perioddramaedit#dominaedit#historyedit#domina sky#gaius octavian caesar#augustus#livia drusilla#julia augusta#octavian x livia#ancient rome#my edits#i still can't believe i can finally use my quotes now!#i have to do another set with that second scene there bc it is gold and it deals with the political aspects of their marriage too

470 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i hope i'm not bothering you but do you have any recs for biographies/documentaries on ancient rome?

Don’t worry, you’re not bothering me at all! I love to talk about the romans lmao

This is going to focus heavily on the late republic and early empire (mostly julio-claudians) because that’s what I’m interested in and I don’t feel comfortable enough to give recs for other periods of time. Hope you find them sufficient, though!

Non-fiction books:

Kicking off with the Punic Wars, Adrian Goldsworthy has a huge, detailed but still readable work on it, The Punic Wars. It has a heavy focus on the military aspect of things, so expect lots of battles, but you can still see some of the personality of the main players shine through it. My favorite part is actually the one that talks about the socio-economic impact the wars had on roman society, because it helps to explain all the shit that is about to happen.

Mike Duncan, best known for his podcast The History of Rome (highly recommended by the people who listen to it, but I don’t have patience for podcasts lol) has his The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic. Covers the Gracchi brothers, the Social War in Italy and the careers and later conflict of Marius and Sulla. Good stuff! I especially like his analysis of the neverending conflict between the more conservative forces of the Senate and the natural changes that needed to happen with the empire growing.

Starting with the biographies now, I’m not really interested in Julius Caesar, but him being such a big figure, I find it hard not to include something about him. The two biographies I see mentioned more often are Philip Freeman’s Julius Caeasar and Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar: Life of a Colossus. Haven’t read either but I guess they are good.

Anthony Everitt is really really readable. I think that Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician is a must read, not only because I love Cicero (though I do lol) but because Cicero had such a long career and interacted with pretty much all the great men of his age (him being a great man himself) and many minor ones too (yes I’m talking about the loml Marcus Caelius Rufus) so you get a pretty complete portrayal of the fall of the Republic. Other than this, his biography on Augustus, Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Emperor, is, alongside with Adrian Goldsworthy’s Augustus: First Emperor of Rome, the most important work about the first emperor.

Prepare for trouble and make it double! Although “minor” historical figures when compared to Caesar or Cicero or Augustus, siblings Clodius Pulcher and Clodia Metelli are major historical figures in my heart dsdfghgfdsfg their biographies also give a great insight on the day to day politics of the republic, the fascinating private lives and loves of these people, and, Clodius in particular, the eternal dispute between Senate and People. So, Clodia Metelli: The Tribune’s Sister by Marilyn B. Skinner and The Patrician Tribune: Publius Clodius Pulcher by W. Jeffrey Tatum.

Cleopatra isn’t a roman, but I’ll be damned if I make a list without mentioning my girl. Cleopatra has many good works written about her, of those I recommend Michael Grant, Joyce A. Tyldesley and Duane W. Roller the best, although Stacy Schiff is probably the most famous. However, since this is a list about Ancient Rome, I will go with a double biography of Cleopatra and Mark Antony: Cleopatra and Antony: Power, Love, and Politics in the Ancient World by Diana Preston. Also, if you’re interested in Cleopatra, @queenvictorias put together a really good and complete list of works here.

For imperial biographies, other than the already mentioned works about Augustus, I wholeheartedly recommend Anthony A. Barrett’s work, who has biographies on a number of julio-claudians: Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome, Caligula: The Corruption of Power and Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire. He has really good analysis, with plausible explanations of what is truth and what is slander in their lives. Among these three, he pretty much covers the entire julio-claudian period.

Now, leaving the biographies for a bit, I think these two works are great to see the relationship Rome had with the rest of the empire. Cleopatra’s Daughter and Other Royal Women of the Augustan Era by Duane W. Roller talks about many royal women from the early empire, including Cleopatra’s daughter Cleopatra Selene and Herod the Great’s sister Salome, and the relationships they had with the roman elite. Interesting read. Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations by Martin Goodman is a huuuuuge work about Rome’s relationship with Jerusalem and the jewish in general, leading up to the wars between them.

To finish the read, H.H. Scullard’s From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68 not only is a classic read, but it covers pretty much the entire period I brough here.

Other than these, I recommend reading the work by the ancient historians like Plutarch, Suetonius, Livy, Sallust, etc. They have sooo much detail, even if we can’t take everything they say seriously.

Documentaries:

Eight Days That Made Rome: Bettany Hughes leads us through eight days (and the context surrounding them) that “shaped” roman history. They include Hannibal, Spartacus, Julius Caesar, Augustus, Nero (and Agrippina!!), among others.

Ancient Rome: Rise and Fall of an Empire: has a lot in common with the previous one in terms of events covered, but has some particular favorites of mine, like the Jewish-Roman War and Tiberius Gracchus.

Barbarians Rising: Rome seen through the eyes of the conquered, including the most famous ones, Hannibal, Spartacus, Boudica and Attila, among others.

Hannibal: Rome’s Worst Nightmare: MUST WATCH because it has Alexander Siddig as Hannibal. Sexy Hannibal.

The Destiny of Rome: covers the Battle of Philippi and Battle of Actium and everything that lead to them and has one of my favorite versions of Antony and Cleopatra.

Netflix Roman Empire: can’t in good conscience recommend this one for the historical accuracy, but it’s fun and sexy, even if batshit insane sometimes, and covers the lives and reigns of Commodus, Caesar and Caligula.

#helenstroy#if you're wondering why the hell this is so big: i'm recovering from a surgery and can't do s h i t#so this distracted me for an entire hour

206 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm looking for some new reading material - do you have any favorite royal biographies/histories?

Ooooh I’m probably not the best for this as my historical reading is very much a niche haha. I tend to only read about women who have been maligned throughout history. If you’re a Tudor fan I would recommend the Six Wives book by Starkey. As a person he’s a bit of a dick but the book covers all six wives and is really interesting. I also thoroughly enjoyed She Wolves by Helen Castor which covers the Queens before Mary- Empress Matilda, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Isabella of France and Margaret of Anjou. For a more international slant I also enjoyed Lady Antonia Fraser’s book on Marie Antoinette. Madame du Barry by Joan Haslip isn’t the best but she’s not well covered in history so I enjoyed that. And to go further back at school I loved Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome by Anthony Barrett which provides a sympathetic defence of Livia Drusilla, who is widely made in to a villain throughout history. Definitely welcome any suggestions from others :)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are some real iconic lines in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome. 10/10 I hope you have this one

i love love LOVE biographies abt women. history should be seen only through what happened to my blorbina fr

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

some inspirational ancient roman ladies

cornelia africana: more popularly known as cornelia mother of the gracchi, she was held up as a sort of gold standard for women by the romans. extremely well-educated, virtuous, and devoted to her husband and children, she held a certain amount of political sway thanks to her relationship with her sons tiberius and gaius. after their deaths, she dedicated her life to studying literature. she was once even offered marriage by one of the ptolemy kings, but chose to stay a widow. one hell of a lady.

fulvia: wife of clodius, curio, and finally mark antony. she is well-known for three things in particular: stabbing cicero’s tongue with her hairpins when his severed head was presented to her (as revenge for how his orations had insulted her husbands), basically taking over rome when antony and octavian went to pursue caesar’s assassins, and raising an army of 8 legions to support antony in his quarrels with octavian

livia drusilla: wife of the first roman emperor, augustus, mother of the second emperor, tiberius, and all-around important imperial gal. as well as serving as a role model for women, she was one of augustus’s trusted advisors, to the point where we are told that augustus (who was apparently not great at speaking on the spot) would write bring notebooks with all of his questions for her to their more important conversations.

clodia metelli: the famous lesbia of the poetry of catullus. an extremely learned woman, the portrayals we are given of her paint a picture of a lady who knew what she wanted and did not particularly care about the feelings of the men around her (a biased portrayal given that the people who wrote about her were her ex and a guy who hated her family, but honestly she can fuck me up). she was notorious for her affairs and in particular her relationship with her rowdy brother clodius pulcher.

octavia minor: sister of octavian (who was to become augustus) and one of the wives of mark antony. she was beloved by the roman people for her matronly virtues, and her marriage to (and eventual divorce from) mark antony helped shape the path of the war between octavian and antony. despite being rejected cruelly by antony while he was in the east, she still did her best to keep the peace by continuing to live in his house and act as his wife. she later raised antony’s children- even those by cleopatra- with her own and to take care of them. overall an extremely gentle and kind woman.

#tagamemnon#i love them all yall theyre so good and they deserve lots of love#clodia metelli#octavia#livia#cornelia#fulvia#queueusque tandem abutere catilina patientia nostra

955 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We cannot be sure why Livia followed Tiberius Nero into exile, unless for the uncomplicated reason of personal affection. It was certainly expected that wives would either accompany proscribed husbands or stay at home and work on their behalf. But they could not be compelled. By now, it must have been apparent to Livia that her husband was not destined for greatness, and it perhaps says something for her strength of character that as a young mother of eighteen or so, she seems to have put duty before personal convenience.

livia: first lady of imperial rome, anthony barrett

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bay fancasts Romans: 1/?

Marta Gastini as Livia Drusilla

“In the consulship of Rubellius and Fufius, both of whom had the surname Geminus, died in an advanced old age Julia Augusta. A Claudia by birth and by adoption a Livia and a Julia, she united the noblest blood of Rome. Her first marriage, by which she had children, was with Tiberius Nero, who, an exile during the Perusian war, returned to Rome when peace had been concluded between Sextus Pompeius and the triumvirs. After this Caesar, enamoured of her beauty, took her away from her husband, whether against her wish is uncertain. So impatient was he that he brought her to his house actually pregnant, not allowing time for her confinement. She had no subsequent issue, but allied as she was through the marriage of Agrippina and Germanicus to the blood of Augustus, her great-grandchildren were also his. In the purity of her home life she was of the ancient type, but was more gracious than was thought fitting in ladies of former days. An imperious mother and an amiable wife, she was a match for the diplomacy of her husband and the dissimulation of her son. Her funeral was simple, and her will long remained unexecuted. Her panegyric was pronounced from the Rostra by her great-grandson, Caius Caesar, who afterwards succeeded to power.” --Tacitus on Livia

#livia drusilla#tagamemnon#livia fc.#marta gastini#julia augusta#honestly look at my wife i love her#i L ov e livia more than my own life and i would die for her#gif

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...On June 26, ad 4, Augustus adopted Tiberius. Livia’s son, forty-four years old, now became officially the son of her second husband. Henceforth he is called Tiberius Julius Caesar and is clearly the man designated to succeed the emperor. As he had in the past, Augustus made provision for the possibility that Tiberius might not necessarily survive him. Agrippa Postumus had not given any evidence of being temperamentally suited for high office, but Augustus perhaps hoped that in the general way of things an unruly youth could mature into a responsible adult. Hence the emperor adopted Postumus on the same occasion.

Moreover, Tiberius was obliged, before his own adoption, to adopt his nephew Germanicus, who would thereby become Tiberius’ son and would legally have the same relationship to Tiberius as his natural son, Drusus. The marriage of Germanicus and Agrippina followed soon after, probably in the next year. There is no reason why the unconcealed manoeuvring on behalf of Germanicus should have upset Livia unnecessarily, despite the clear implications of Tacitus that it did. Germanicus, after all, was her grandson as much as was Drusus Caesar. The arrangement reinforced rather than weakened the likelihood of succession from her own line, as was to be demonstrated by events.

The marriage would prove extremely fruitful. In time Agrippina bore Germanicus nine children, six of whom survived infancy. The first three were sons, great-grandsons of Livia: Nero, the eldest (not to be confused with his nephew Nero, the future emperor); Drusus (to be distinguished from the two more famous men of the same name: Drusus, son of Livia, and Drusus Caesar, son of Tiberius); and Gaius (destined to become emperor, and known more familiarly as Caligula). She also bore three surviving daughters, Drusilla and Livilla, and, most important, the younger Agrippina, mother of Livia’s great-great-grandson, the emperor Nero. The adoption of Tiberius in ad 4 would have been an occasion of joy and satisfaction for Livia, and would have helped to efface any lingering grief that still afflicted her over Drusus’ death.

If we are to believe Velleius, not only Livia but the whole Roman world reacted jubilantly to the new turn of events. Needless to say, his account should be treated with due caution. There was, he claims, something for everyone. Parents felt heartened about the future of their children, husbands felt secure about their wives, even property owners anticipated profits from their investments! Everyone looked forward to an era of peace and good order. A colourful exaggeration, of course, but there probably was considerable relief among Romans that the succession issue seemed at long last to be settled.

…In the immediate aftermath of the adoptions the ancient authors inevitably tend to focus on Tiberius and the campaigns he conducted in Germany and Illyricum, and they virtually ignore Agrippa Postumus, whose name was to be invoked later by sources hostile to Livia. A few details about Postumus emerge. In ad 5 he received the toga of manhood. The occasion was low-key, without any of the special honours granted Gaius and Lucius on the same occasion. It also seems to have been delayed. Postumus would have reached fourteen in ad 3, and under normal circumstances might reasonably have been expected to take the toga in that year. Something seems to be wrong. Augustus had certainly endured his share of problems with the young people in his own family. The pressures facing the younger relatives of any monarch are self evident, given the sense of importance that precedes achievement, to say nothing of the opportunists attracted to the immature and malleable, and prepared to pander to their self-importance.

As Velleius astutely remarks, magnae fortunae comes adest adulatio (sycophancy is the comrade of high position). These pressures must have been particularly intense in the period of the Augustan settlement, when no established standards had yet evolved for the royal children and grandchildren. Gaius and Lucius, the focus of Augustus’ ambitions and hopes, caused him endless grief by their behaviour in public, clearly egged on by their supporters, and on at least one occasion Augustus felt constrained to clip their wings. Gaius’ brave but distinctly foolhardy behaviour during the siege of Artagira is surely symptomatic of the same conceit.

There is no reason to assume that Postumus would have been immune from the pressures that turned the heads of his siblings. Whatever traits of haughtiness Postumus might have displayed in his early youth, they were not serious enough to have entered the record, and the exact nature of his personal and possibly mental problems is far from clear. The ancient sources speak of his brutish and violent behaviour. Some modern scholars have suggested that he might have been mad, but the language used of him seems to denote little more than an unmanageable temperament and antisocial tendencies.

For whatever reasons, eventually Augustus decided to remove him from the scene. The details of this expulsion are obscure. Suetonius provides the clearest statement, recording that Augustus removed Postumus (abdicavit) because of his wild character and sent him to Surrentum (Sorrento). The historian notes that Postumus grew less and less manageable and so was then sent to Planasia, a low-lying desolate island about sixteen kilometres south of Elba. Tacitus has no doubt about where the ultimate responsibility for Augustus’ actions lay. Postumus had committed no crime.

But Livia had so ensnared her elderly husband (senem Augustum) that he was induced to banish him to Planasia. Tacitus’ technique here is patent. The use of the word senem is meant to suggest that Augustus was by now senile, even though the event occurred eight years before his death. Incapable of making his own rational decisions, he would thus be at the mercy of a scheming woman, just as later Agrippina the Younger reputedly ‘‘captivated her uncle’’ Claudius (pellicit patruum). No reason is given for Livia’s supposed manoeuvre—which as usual, according to Tacitus, was conducted behind the scenes—except the standard charge that her hatred of Postumus was motivated by a stepmother’s loathing (novercalibus odiis).

Yet nothing in the rest of Tacitus’ narrative sustains his assertion, and the historian himself admits that the general view of Romans towards the end of Augustus’ reign was that Postumus was totally unsuited for the succession, because of both his youth and his generally insolent behaviour. Moreover, Augustus had made the strength of Tiberius’ position so patently evident that Livia would hardly have considered Postumus a serious candidate. This seems to be confirmed in a remarkable passage of Tacitus which uncharacteristically reports public reservations about a potential role for Germanicus, supposedly Tiberius’ rival.

After reporting the popular view that Postumus could be ruled out, Tacitus says that people grumbled that with the accession of Tiberius they would have to put up with Livia’s impotentia, and would have to obey two adulescentes (Germanicus and Drusus) who would oppress, then tear the state apart. Tacitus concedes that even the prospect of the reasonable Germanicus and Drusus being involved in state matters caused consternation. This surely offers some gauge of how far below the horizon Postumus was to be found. The precise reason for Postumus’ removal to Sorrento, if it was not simply his personality, is not clear. The initial expulsion may have been provoked by nothing more serious than personal tension between him and his adoptive father.

Whatever the initial reason, it soon became apparent that if Augustus had hoped that sending his adopted son out of Rome would solve the problem, he was mistaken. Dio places Postumus’ formal exile to Planasia in ad 7. If, as Suetonius claims, he was sent first to Sorrento, what might have precipitated the change in the location and the more grave status of his banishment? We have some hints in the sources. Dio suggests that one of the reasons for Augustus’ giving Germanicus preference over Postumus was that the latter spent most of his time fishing, and acquired the sobriquet of Neptune.

Now this could point simply to irresponsibility and indolence, but the picture of Postumus as an ancient Izaak Walton serenely casting his line does not fit well with the very strong tradition of someone wild and reckless. His activities may well have had a political dimension. The choice of the nickname Neptune could allude to the naval victories of his father, Marcus Agrippa. The fishing story might well belong to the period after Postumus’ relegation to Sorrento. This could have proved a risky spot to locate Postumus, because it lay just across the bay from the important naval base at Misenum that his father had established in 31 bc. The innocent fishing expeditions might have covered much more sinister activities.

Augustus may well have concluded eventually that Postumus was too dangerous to be left in the benign surroundings of Sorrento. During Postumus’ second, more serious phase of exile, on the island of Planasia, he was placed under a military guard, a good indication that he was considered genuinely dangerous rather than just a source of irritation and embarrassment. This final stage of banishment was a formal one, for Augustus confirmed the punishment by a senatorial decree and spoke in the Senate on the occasion about his adopted son’s depraved character. Formal banishment enacted by a decree of the Senate would be intended to make a serious political statement and should have buried completely any thoughts that Postumus might have been considered a serious candidate in the succession.

We cannot rule out the possibility that Postumus became involved, perhaps as a pawn, in some serious political intrigue, if not to oust Augustus then at the very least to ensure that he would be followed not by a son of Livia but by someone from the line of Julia. If Postumus was being encouraged to think of a possible role in the succession, it might reasonably be asked who was doing the urging. Although there is no explicit statement on the question in the sources, many scholars have accepted the notion that there existed a ‘‘Julian party,’’ responsible for much of the ‘‘anti-Claudian’’ propaganda directed against Livia and Tiberius that is found in Tacitus in particular and possibly derived from the memoirs of Agrippina.

…Whatever the intrigues in Rome, Livia’s son was able to keep himself aloof and to play the role that suited him best, that of soldier. Tiberius conducted a brilliant series of campaigns in Pannonia for which a triumph was voted in ad 9. (This was postponed when Tiberius was despatched to Germany in the aftermath of the disastrous defeat of Quinctilius Varus, in which three legions were lost.) When the Pannonian triumph was voted, Augustus made his intentions crystal clear. Various suggestions were put forward for honorific titles, such as Pannonicus, Invictus, and Pius.

The emperor, however, vetoed them all, declaring that Tiberius would have to be satisfied with the title that he would receive when he himself died. That title, of course, was Augustus. It also appears that a law was later passed to make his imperium equal to that of Augustus throughout the empire, and in early 13 his tribunician power was renewed. His son Drusus Caesar received his first accelerated promotion, designated to proceed directly to the consulship in ad 15, skipping the praetorship that should have preceded this higher office.

The virtual impregnability of Tiberius’ position should be borne in mind in any attempt to understand the final months of Augustus’ life. In the closing chapter of her husband’s principate, Livia reemerges in the record to play a central and, according to one tradition, decidedly sinister role. This is perhaps the most convoluted period of her career, where rumour and reality seem to diverge most widely. To place the events in a comprehensible context, it is necessary to note one later detail out of its chronological sequence. As we shall see, after Augustus’ death there was a rumour reported in some of the sources that Livia had murdered her husband.

In the best forensic tradition, a motive would have to be unearthed to make the charge plausible, especially since sceptics could hardly have failed to notice that Augustus had never enjoyed robust health and was already in his seventy-sixth year. Death from natural causes could hardly be considered remarkable under such circumstances. The requisite motive would indeed be produced, and the kernel of the intricate thesis that evolved is found in a brief summary of Augustus’ career by Pliny the Elder. Among the travails that afflicted the emperor, Pliny lists the abdicatio of Postumus after his adoption, Augustus’ regret after the relegation, the suspicion that a certain Fabius betrayed his secrets, and the intrigues of Livia and Tiberius.

Pliny’s summary observations are clearly based on a more detailed source, which suggested that Augustus felt some remorse about Postumus. This simple and not improbable notion is developed by other sources into a far more complex scenario that creates an apparently plausible motive, because it could be claimed that Livia would have wanted to remove her husband before he could act on his change of heart. This reconstruction of the events is clearly reminiscent of the closing days of the reign of Claudius, when the emperor supposedly sought a rapprochement with his son Britannicus, to the disadvantage of his stepson Nero, and thereby inspired his wife Agrippina to despatch him with the poisoned mushroom.

But it is important to bear in mind that as Pliny reports the events he limits himself to the claim that Augustus regretted Postumus’ exile, without further elaboration, and although Livia and her son supposedly engaged in intrigues of some unspecified nature, Pliny assigns no criminal action to either of them. Pliny’s ‘‘skeleton account’’ is to some degree validated by Plutarch. In his essay on ‘‘Talkativeness,’’ Plutarch, in a very garbled passage, relates that a friend of Augustus named ‘‘Fulvius’’ heard the emperor lamenting the woes that had befallen his house—the deaths of Gaius and Lucius and the exile of ‘‘Postumius’’ on some false charge—which had obliged him to pass on the succession to Tiberius. He now regretted what had happened and intended (bouleuomenos) to recall his surviving grandson from exile.

According to Plutarch’s account, Fulvius passed this information on to his wife, and she in turn passed it on to Livia, who took Augustus to task for his careless talk. The emperor made his displeasure known to Fulvius, and he and his wife in consequence committed suicide. This last detail was perhaps inspired by the famous story of Arria, who achieved immortal fame in ad 42 when she died with her husband Caecina Paetus, who had been implicated in a conspiracy against Claudius. Plutarch’s confused version of events does not inspire confidence, and in any case, although he gives Livia a more specific role than does Pliny, he follows Pliny in not attributing to Augustus any action, only supposed intentions.