#foliate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

foliation by suze woolf

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to bring up more Bad News, especially since we're already drowing in it in the first month of the year, but in Seattle it's January and we still haven't had our first real frost of the year yet, which is Not a good sign!!

We've have some light frost just from the typical cold air falling to the ground but no sustained sub-0°C temps. When the nasturtiums are all still alive in the PNW there is something very wrong

#I wonder if any of the Capsicum species are going to live aside from the weird ones like C. pubescens#which are able to tolerate the cold anyways as long as they don't get frostbitten#I think the C. chinense and C. baccatum are all dead as expected#I've had C. annuum survive a normal winter before (though not well enough to re-foliate and succumb to infection later in the spring)

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Furrow orb weaver?

#northern hemisphere#furrow orbweaver#furrow spider#furrow orb spider#foliate spider#spider#spiders#arthropoda#chelicerata#chelicerate#arachnida#arachnid#arachnids#araneae#araneidae#orb weaver#orbweaver#animal polls#poll blog#my polls#animals#polls#tumblr polls#bugs#bug

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

sieved sun

#nature#photography#sweden#nature photography#canon#photographers on tumblr#beauty#beauty of nature#forest#woods#birches#foliage#leaf#leaves#new foliage#new leaves#new leaf#spring foliage#spring leaves#spring leaf#birch leaves#foliation#spring sun#spring in sweden#sunshine#sunlight#sun through trees#sunlight through trees#beautiful#beautiful nature

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foliate Dish with Bovine (Xiniu) Gazing at a Crescent Moon

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), late 13th century

China

Medium:

Longquan ware; stoneware with underglaze molded decoration

Currently on display at the Art Institute Chicago

#Foliate Dish with Bovine gazinf at crescent moon#yuan dynasty#13th century#13th century china#cultural artifact#longquan ware#art#art history#anthropology#a simple cow#ceramics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Piper, Foliate Head: Spring (c. 1981)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Green Man, watercolor and color pencils

#Green Man#folklore#foliate head#Gothic art#gothic motif#medieval#medieval art#mythology#fairy#fairytale#historic design#ornament#pagan art#art#illustration#artwork#fantasy art#monsters#fantasy#fantasy creatures#watercolor#watercolor art#artists on tumblr#tumblr art#art on tumblr

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

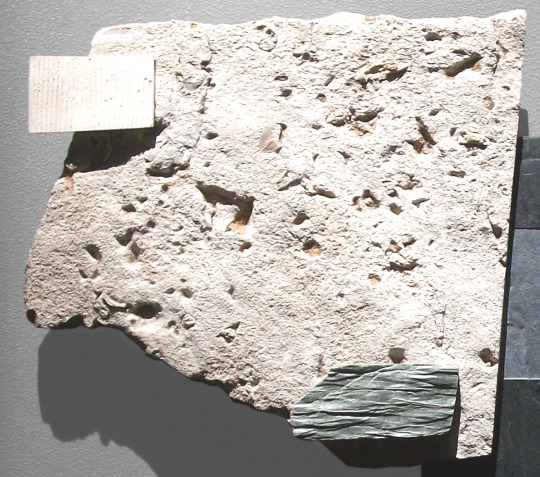

NIVEN'S GARDEN GAME

Virginia slate, fossiliferous Indiana limestone, Georgia foliated serpentine/talc, sandblasted glass, brass, stoneware

10"x 14½"x 1½"

What I imagine the game might be like in the metaphorical interstellar garden of author Larry Niven . . . an homage.

Larry Niven is an American science fiction author whose best-known work is Ringworld, which received Hugo, Locus, Ditmar, and Nebula awards. His work is primarily hard science fiction, using big science concepts and theoretical physics (see Freeman Dyson for the genesis of Ringworld). The creation of thoroughly worked-out alien species as protagonists in his novels is recognized as one of Niven's main strengths.

Larry Niven (American, b.1938 Los Angeles, California)

#sculpture#my artwork#stone#art by me#Don Dougan#Larry Niven#fossiliferous limestone#glass#slate#brass#ceramic#foliated talc

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

All I need is wait for tomorrow then Tactica will be officially released!

Unfortunately,I didn't got a Steam account or any game console that allows me to play it.The game's also too costly for me.

However,I could still get myself a cup of coffee,sitting in front of computer and watching the playthrough,imagining I'm the one playing it.

Actually,I tried to color boss in a different way but they all ended up looking quite strange so I decided I'll just using grey for him.

Goat,as their original habitat does,they got short temper.And our Leblanc's boss is the best example of it.Before he opened Leblanc,he was a normal government officer.His job allows him to contact with his one and only crush in the world out of proper reasons.And her name was Monochrome Foliate,a researcher at the lab.

Even though he knows she got a daughter that called Cloven Foliate.He did asked Monochrome Foliate about Cloven Foliate's father and what's the accurate thing she was researching for,but she never give answers.Even so,he still fall for her hopelessly as if he was being shoted by Cupid's golden arrow.

He used to think that they'll maybe lived happily together just like a normal family in the rest of his life.Of course,he was totally wrong about that.Life was a box of chocolate,which is fulled with chaos.

One day,Monochrome Foliate told boss to be careful because there maybe something happen on her.At first,he didn't take it seriously.But when he received the message about Monochrome Foliate "suicides" ,he realized that warning was never a joke.

So,he adopted her daughter,resinged his job and opened a caffe — Leblanc.Did his best to hide from the danger that Monochrome died in.

There's no way that he could find out the truth behind her death also her researches,he believes so.However,when he had bring a "delinquent" to this shattered family,he'll never expected that Cloven Foliate will step out from her room to contact with outside world,he'll also never expected that he could finally know who's the one that killed Monochrome Foliate and the distorted desire beneath the shadow of the society.

#my drawings#mlp au#digital art#shin megami tensai persona#persona 5#sakura sojiro#caffe machiato#goat#cloven foliate#monochrome foliate#rainy palace

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disgorging foliate heads as medieval symbols of Christianity

Here's something of a pagan PSA: The Green Man is probably not a pagan symbol or deity.

I probably should have dug into this when that coronation invite was doing the rounds last month, but I reckon now's as good a time as any, as long as it's on my mind.

Don't let the grass horns on that coronation Green Man or decades of modern pop cultural mythology fool you: there's not really anything "pagan" about the Green Man. The idea of the Green Man as a pagan deity or mythological figure has been prevalent in the popular imagination for almost a century now, first proposed by a woman named Lady Ragland in 1939, but while people have made all sorts of connections to various pre-Christian gods, there has never been any evidence of the Green Man as an actual figure of some pre-Christian religion. Instead, the Green Man as we know him was probably actually a figure of medieval Christianity. But even that's only scratching the surface, because even the name "Green Man" itself is just a modern name for a series of faces that appear on medieval churches all over England as well in other parts of Britain and Europe.

Historian Stephen Miller suggests that the more accurate name for this motif is the "disgorging foliate head motif". It's not as catchy or pleasant as "Green Man", I admit, but several church icons do literally look like that.

According to Miller, these heads became part of medieval British Christian iconography after having imported by occupying Normans who came from France. So, in a way, you can probably think of the Green Man as a relic of Norman occuption, originally a French motif brought in by the Normans who invaded and colonized England and Wales before eventually becoming part of British iconography.

As to its religious significance, Miller tells us that it represents a motif from the Quest of Seth (or Legend of the Rood), a set of medieval Christian legends about Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve. The basic legend goes that Adam, on his deathbed, sends Seth out to Paradise to find an elixir of immortality. There Seth meets an angel who refuses to give him the elixir, but the angel does instead give Seth a seed (or perhaps more than one seed) from the forbidden tree where Adam and Eve first ate the apple. When Seth returned, Adam had already died, and then Seth planted the seed(s) in Adam's mouth or beneath his tongue, and then buried him in the soil of Golgotha, the place where Jesus was crucified. Then a tree grows from Adam's corpse, which is then cut down and turned into the cross on which Jesus was crucified. In some versions of the legend it's not a tree, but rather a bunch of twigs and shoots, which would explain some of the motifs.

I suppose you can loosely derive the theme of rebirth in some context, but it would not be a pagan context. The "Green Man" was not meant to be understood as a pagan god. Instead, if anything the "Green Man" was probably a medieval representation of Adam, who in the Quest of Seth dies and is reborn into what becomes the cross at Golgotha. So the "rebirth" of the Green Man is a strictly Christian "rebirth": the resurrection of Jesus, which in the Quest of Seth is prefigured by "rebirth" of Adam. That is what Miller refers to as "new life to humankind" - the "new life" promised by Jesus.

So, although the "Green Man" has sort of become a fixture of British popular folk myth and culture, it was originally a Norman icon, a fixture of the Norman occupation of Britain, that also represented medieval legends about Seth and Adam. The disgorging foliate head, which we now call "Green Man", was never really a "pagan" symbol, though it does sort of resemble many similar symbols from various ancient cultures (such as the Kirtimukha in India). The motif we know today and call "Green Man" was probably always a Christian symbol, not a pagan one. I suppose if you want to keep brandishing it, that's your business, but don't refer to it as a pagan symbol or the image of a pagan god, because it just isn't.

#green man#paganism#christianity#medieval literature#british mythology#disgorging foliate heads#medieval legends#the quest of seth

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

foliation by suze woolf

907 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Green Man: Myth and Reality - Imogen Corrigan

I was in the process of writing – well, researching – an idea I had for a novel. It involved various incarnations of the Green Man and probably owed more to Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing than I care to admit. It was a very cozy eco-centric idea in which the remaining green spaces fight back against the great polluters and yadda yadda yadda… My prior research – and experience – led me to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

I'm God's favourite princess today

#each item is from a different charity shop#the books and the foliate head are from two shops on the opposite ends of town

1 note

·

View note

Text

#technically my first artwork of the year. it just took me a long time to finish it#green man#foliate head#personal work

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

“Foliation” by Suze Woolf — the term “foliation,” refers both to the way rocks layer and the structure of a book.

The work is crafted from crystalline selenite, laser-cut acrylic sheets, and bound with linen thread using a modified Coptic binding technique. The reflective qualities of selenite tie it to the concept of celestial bodies—its name references Selene, the Greek goddess of the moon 🌙

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes