#faventions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ViensOnDiscute, en parlant de SCH de DeoFavente: « vraiment so époque,… son époque non-binaire »

JSINDJANWKJJDJBWK?????

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deo favente

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ageltrude, [wife of Guy of Spoleto], was not born into the north Italian nobility, as she was the daughter of the prince of Benevento, Adelchis. However […], she was chosen by Guy before he had nurtured royal ambitions. Being an outsider meant that Ageltrude had to find new friends and supporters once her husband managed to conquer the kingdom [of Italy]. She did this very successfully. Narrative sources report that she was involved in political affairs, and that after her husband’s death she remained active in politics at the side of her son Lambert; documentary evidence shows that she granted a considerable amount of properties and monastic institutions in northern Italy. Most importantly, her presence in diplomas is characterized by three aspects: the peculiarity of her titles, her role as competitor for the Carolingian women, and the close relationship with the chancery. All these aspects help to illuminate Guy’s political strategies to keep the kingdom under control.

— Roberta Cimino, Italian Queens in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries (PHD Thesis, University of St Andrews, 2014)

Four diplomas, issued on the day of Guy’s imperial coronation in Rome, on 21st February 891, are particularly interesting for the analysis of political language, as well as for the role Ageltrude played. The diplomas, now preserved in the Archivio Capitolare of Parma, confirmed or granted properties to the new empress, with the intercession of the archchaplain Wibod and, in one case (DGui5) of the marchio of Ivrea Anscar, a member of Guy’s family group. They show common features, which are peculiar to Guy’s chancery. Among them are the emperor and empress’ titles: “Vuido divina favente clementia imperator augustus” and “dilectissime coniugi nostrae Ageltrudi imperatrici et consortem imperii nostri”.

The reason for the issuing of several diplomas in favour of Ageltrude on this particular day has been debated by scholars. Paola Guglielmotti has recently pointed out that Ageltrude’s new patrimonial situation was created to fit her new public status. In her case consortium imperii was associated with the acquisition of properties with a well-established royal identity. The granting of benefices to religious institutions could be the king’s deliberate choice of imitating a tradition. Rosenwein has noted that new rulers tended “to follow the tradition of kings in giving away the symbols and substance of fortified edifices”. This model has been applied by La Rocca to the relationship between Italian queenship and San Salvatore in Brescia. I have argued above that this can be generally applied to monastic institutions in northern Italy. In the case of Ageltrude it is applicable to the Pavese monasteries that had a royal identity, as they had been founded and endowed by Lombard and Carolingian queens.

Guy, however, had to choose other symbols of power, as San Salvatore and San Sisto were controlled by his adversaries, Berengar and the Supponids. Besides DGui4, which confirmed to Ageltrude properties and rights she already had, the other three charters concern three nunneries in the town of Pavia. DGui5 granted to Ageltrude San Marino, the nunnery probably founded by Richgard, which in 889 had been granted to Angelberga by Arnulf of Carinthia. DGui6 concerns the confirmation of Sant’Agata: the convent was, therefore, already under the control of Ageltrude. Finally, DGui7 established the grant of the nunnery Reginae in Pavia. These charters qualify Ageltrude as consors imperii and as a significant member of Guy’s entourage, granting her nunneries which were linked to past queens. The confirmation of Sant’Agata is particularly interesting, as this was a royal nunnery outside of Guy’s sphere of control, and the original donation must date back to the royal coronation, that is to say after May 889. Moreover, the diplomas suggest that Ageltrude was close to other members of the imperial court and that she was supported by Guy’s key men, especially bishop Wibod of Parma. The close relationship between the empress and the diocese of Parma would become more evident in the later part of Ageltrude’s life: in her last testament, produced in 923, she granted her properties to the church of Parma. The other person who appears as intercessor for Ageltrude is the marchio of Ivrea Anscar, who had been a faithful ally of Guy since 888, and fought in the battle of the Trebbia river in 889. He appears in the charter with the title “marchio dilectusque consiliarius noster”. Anscar is mentioned as marchio for the first time in this charter: this document records the creation of a significant territorial jurisdiction, the marca of Ivrea, which acquired a decisive strategic importance.

Following the imperial coronation, Ageltrude seems to be at the centre of a political network which was expressed through a highly formalized diplomatic language, a formally organized chancery and the enhancement of relations with the primores of the kingdom. The use of consors imperii in the diplomas issued in February 891 suggests, moreover, a different meaning of the title, for it was employed by Guy’s chancery exclusively in diplomas in which the empress appeared as beneficiary.

In order to clarify the last point, one needs to take into account that in 894 the Carolingian east-Frankish king, Arnulf of Carinthia, arrived in Italy and seriously threatened Guy’s authority. Many northern Italian towns, such as Pavia, Milan and Piacenza, surrendered to him, while Guy hastily abandoned northern Italy and probably took refuge in the south. In April 894 he had set his court in the area of Petrognano, near Spoleto, which was controlled by his fidelis Liutald. However, Arnulf had soon to give up his plans to move towards Rome, because of the lack of adequate military forces; during his retreat, in March 894, he encountered the opposition of Guy’s ally, Anscar, at Ivrea. Just after this episode, in April 894, Guy granted to Ageltrude (“dilectissimae coniugi nostrae Ageltrudi imperatrici et consortem imperii nostri” [sic]) two curtes “iure hereditario”, Murgola in the area of Bergamo and Sparavera in Piacenza. Both those areas had been seriously affected by Arnulf’s expedition in Italy. In particular, Bergamo had posed strenuous opposition to Arnulf; once the town had been taken by the Bavarian king, Count Ambrose had been ferociously executed. Arnulf’s expedition had also seriously affected Piacenza, where the Bavarian king had settled his court between February and March 894. Here he issued two diplomas, one of which was for the church of St Ambrose in Milan. Arnulf had easy access into Milan as the count of the city, Manfred, had surrendered to the Bavarian king in order not to lose his office. The diploma for St Ambrose proves that Arnulf could count on significant support inside the city, provided by the bishop and the lay elite. The diploma aimed at establishing a continuity with the previous rulers of Italy, as in the same document Arnulf confirmed to the monastery rights and properties granted by former Carolingian rulers, his own ancestors.

This charter suggests that Guy’s chancery associated the expression consors imperii with a patrimonial idea of the queen’s office; for Ageltrude was defined consors only in diplomas in which she appears as beneficiary, and never when she acted as intercessor. She is not called consors in a diploma issued in May 892, in which she interceded, “per Ageltrudim amantissimam coniugem nostram imperatrice augustam”, for marchio Conrad, a Widonid, who was granted a royal curtis of Almenno in the comitatus of Bergamo. In this diploma, jointly issued by Guy and Lambert (“Vuido et Lantbertus gratia et misericordia eiusdem omnipotentis Dei imperatores augusti”), Conrad is defined as patruus and patruelis, that is to say uncle (of Guy) and great-uncle (of Lambert). According to the diploma the curtis of Almenno had been originally granted to Conrad by Louis II. Hlawitschka has argued that the fiscal estates controlled by the Widonid family could have been lost in the early 870s, as a consequence of the support given by Lambert of Spoleto (Guy’s father and possibly Conrad’s brother) to the Beneventans’ revolt against Louis II. There is some evidence of these fiscal estates passing into the hands of the women of Louis II’s family: in February 875 Louis the German had granted the royal curtes of Almenno and Murgola (also located in the area of Bergamo), together with other properties, to his niece Ermengarda.

In this competitive situation, Guy’s choice to grant to Ageltrude properties in two strategic areas of the kingdom, whose elite had recently, more or less willingly, passed to his opponent’s side, was an attempt to reaffirm his authority in those areas. In the charter Ageltrude is presented as “imperatrix et consors imperii nostri”, while Guy himself adopted the original title of “Vuido Caesar imperator augustus”. The formulary of the diploma is modeled on DGui7, issued on the day of the imperial coronation, evoking the imperial authority that Guy was at risk of losing. In other words, Ageltrude was the centre of a strategy of political legitimation.

The two properties she received had a particular significance also for another reason. The curtis Murgola, as well as Almenno, had been granted to Ermengarda, Angelberga and Louis II’s daughter, in the above mentioned diploma of Louis the German. After the defeat and death of her husband, in 887, Ermengarda had not abandoned her ambitions. After having attempted to have her son Louis succeed Charles the Fat, Ermengarda put herself and her son under the protection of the new king Arnulf, who had deposed Charles. In 889 Arnulf of Carinthia confirmed a group of properties to Angelberga, among which there was also the curtis Sparavera, and established that after her death those properties had to be passed on to her daughter Ermengarda. The request for the confirmation was made by Ermengarda herself, in order to protect her Italian properties after the death of her mother. As a result, in 890 Louis III was crowned king of Provence at Mantaille, with the approval of Arnulf. By granting Sparavera to Ageltrude, Guy deprived Ermengarda of part of her wealth, disposing of properties traditionally controlled by the Carolingians - in 883 Murgola was controlled by Charles III - and gave them to his own wife, who was, according to the diploma, the truly legitimate consors imperii. This was a clear political claim against Arnulf, and more broadly against the Carolingian house. The closeness of Arnulf and Ermengarda suggests that Guy’s choice to grant properties which had belonged to the late empress Angelberga and to her daughter was an attempt to challenge the Carolingians’ ambitions in Italy.

Guy used other means to stress his continuity with the Carolingian empire. His seal (on the obverse) reads “Renovatio Regni Francorum”, a formula previously used by Louis the Pious, and later by Charles the Fat. In 896 the same expression was employed for a seal attached to a diploma of Arnulf of Carinthia. It is interesting that Guy and Arnulf both used the same model, the seal of Charles the Fat. This casts light onto a conflict which was being fought with similar weapons on both sides: language was one of them. It shows, furthermore, Guy’s desire to accentuate a continuity with the Carolingians, although - or maybe because - he did not have any dynastic claim. Furthermore, Guy and Lambert presented themselves as legislators, issuing three capitularies. This was an important aspect of Carolingian public activity, which was never undertaken by any other post-Carolingian Italian rulers.

Guy, a “new man” facing struggles for the royal title, used law-making, diplomacy and gift-giving in order to assert his authority and territorial control over his new kingdom. Ageltrude’s presence in charters, and the way she was presented in those charters, show that she was employed in this process. Not only was she granted a group of nunneries with a royal identity, which had all been founded or at some point controlled by Carolingian royal women. She was also given properties situated in areas with a strategic significance for Guy in terms of his attempt to face the Carolingian family and its supporters in Italy. For this purpose, the title consors imperii was employed in a different way from what had been done in the past, for it was associated with the queen’s patrimonial status.

In other words, Ageltrude was presented as a royal landholder and monastic patron, who controlled estates and nunneries with a strong royal tradition.

Her influence was evident also during her widowhood. Guy died in the summer or autumn of 894, leaving the kingdom in the hands of his young son Lambert, who at the time was about fourteen years old. Lambert’s chancery was a continuation of his father’s and involved the same group of people: the archchancellor Elbuncus remained at its head. The language of charters reflects this continuity: Lambert frequently appears with the same, peculiar, title “Caesar imperator augustus”, which had been used for his father. Charters show that in this transition Ageltrude maintained an influential role. In December 895, she acted as intercessor in a charter that granted a fiscal curtis in the comitatus of Reggio Emilia to the viscount of Parma, Ingelbert. In that period Arnulf of Carinthia had arrived in Italy for the second time, taking control of the north with the support of part of the nobility. Lambert left the capital, and set up his court in the town of Reggio Emilia. The curtis was granted to the viscount with the intercession of Ageltrude, of the vassal Liutald – a faithful friend of Guy - and of the count Radald “vasso scilicet Radaldi illustrissimi comitis atque summi consiliarii nostri”. Radald belonged to the Attonids, and was the son of the marchio Conrad, Lambert’s patruelis, to whom Guy had granted some properties in the area of Bergamo the year before (Conrad was marchio of Spoleto and count of Lecco). As Hlawitschka has argued, this is an interesting political operation that took place in the key town of Parma: the comitatus, which for several generations had been linked to the Supponid family, Berengar’s supporters, passed into the hands of a member of the Widonid family group. Radald was put in charge of the comitatus of Parma to undermine the Supponid influence in the area; although he had previously collaborated with the family politics of the Supponids. He was one of the subscribers of Angelberga’s testament for San Sisto, a document aimed at enhancing the family’s economic and territorial control of Emilia. This happened in 877, when the Widonids had not yet developed the royal claims that would later make them oppose the Supponids’ territorial politics. The role held by Ageltrude in her son’s political entourage is expressed in the charter through the title “domina et genitrix nostrae Ageltruda gloriosissima imperatrix augusta”, which acknowledges her prominence.

Furthermore, in May 896 Lambert granted to his mother (“dulcissima genitrix nostra”) the royal curtis of Corana, in the comitatus of Tortona. The grant was given with the intercession of Adalbert of Tuscany, one of Lambert’s supporters against Arnulf.

Arnulf had to leave Italy during spring 896, after he had managed to enter Rome. Benedict of S. Andrea reports that Rome was strenuously defended by Lambert and Ageltrude, but they had to abandon the city to Arnulf, who was crowned emperor by Pope Formosus. However, Arnulf did not manage to defeat Lambert, as the king took refuge in the area of Spoleto, where he could count on some support. Arnulf tried to pursue Lambert in order to defeat him. At this point an infamous episode about Arnulf’s poisoning by Ageltrude is reported by Liudprand. Although this tale has to be read in relation to Liudprand’s impressionistic depiction of evil women, it suggests an active involvement of the empress in the struggle between her son and the Bavarian king, which is confirmed also by other narrative texts. Arnulf’s decision to abandon Italy was a good result for Lambert: he regained control of Pavia and the royal authority, and was therefore in a position to reward his allies. The grant for Ageltrude is to be placed in this context, and possibly to be related to the help the empress had given to her son. According to the Annals of Fulda, at this point Lambert and Berengar reached an agreement for the division of the kingdom, establishing the Adda river as a frontier: a period of relative stability followed the departure of Arnulf.

Furthermore, Ageltrude appeared again as intercessor in a diploma issued in February 898 in Ravenna, for the church of San Giovanni in Florence. The diploma was issued just after the Diet of Ravenna of February 898, during which Lambert had renewed his agreement - originally made in 892 - with the Pope and had the imperial title confirmed. It is therefore not a coincidence that Ageltrude appeared with an imperial title (“Ageltrudae serenissimae imperatricis augustae”), which she did not have in the previous diplomas issued by Lambert’s chancery. DLa10, issued in Marengo on the 2nd September 898, also concerned Ageltrude, as she acted as intercessor on behalf of the church of Arezzo for the grant of the royal curtis of Cactianus. On this occasion Ageltrude interceded together with the new archchancellor Amolus, who was probably the bishop of Turin and who is mentioned as Lambert’s chancellor from 896. In this diploma Ageltrude is not mentioned by name, but as domina genitrix nostra, the title with which she is often presented in Lambert’s diplomas [...].

The evidence analysed above shows that Ageltrude had a significant role in the shaping of Guy and Lambert’s politics. As Guy did not have as extensive a network of supporters in northern Italy as that of his adversaries, he employed his wife in the process of building a network of friends and liaising with religious institutions. In these circumstances the representation of Ageltrude’s importance was related to a patrimonial idea of queenship: this idea is reflected by the use of consors imperii. The title was used only in charters that granted properties and nunneries to the empress. Moreover, these properties and convents had all previously been in the hands of other Carolingian women. This suggests that the concept of imperial consortium, as it was intended by Guy’s court, portrayed the shared control of the royal fisc between the imperial couple. In other words, Guy’s chancery shaped the title’s meaning around what was important for the emperor, namely the control of fiscal properties in northern Italy and the relationship with the Carolingian past and present represented by his contenders. In Ageltrude’s case, the title was used because these gifts to her were potentially controversial or precarious - because she was an outsider with no Carolingian blood and no familial connection among the north Italian nobility.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

ma kush de sch c'est tellement une ambiance iris l'hypnotiseur égyptien d'astérix les douze travaux

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petronius' Satyrica Dissertation Diary #4

At 55.4-5, Trimalchio begins a discussion concerning the difference between Publilius Syrus and Cicero. Trimalchio’s opinion is that while Cicero is more well-spoken (disertiorem), Publilius is more honorable (honestiorem). He follows this opinion with a sixteen-line poem that he claims are lines by Publilius. A few things are notable about the fact that Trimalchio chooses Publilius over Cicero aside from the comedic aspect––that Publilius Syrus, a Syrian-born freedman who was famous for writing and acting in mimes, is more honorable than Cicero.

First, Trimalchio's choice is meant as an imitation of Julius Caesar who also chose the freedman Publilius Syrus in a contest of improvised mime composition against the eques Decimus Laberius in 46 BCE at the ludi Victoriae Caesaris celebrating Caesar’s victories in the civil war. As Macrobius records, Caesar, while laughing, proclaimed favente tibi me victus es, Laberi, a Syro (“While I am inclined toward you, Laberius, you have been defeated by the Syrian”). Thus Trimalchio steps into the role as Caesar making the same choice as he did.

Interestingly, in a three line epigram just before the discussion of Publilius and Cicero, Trimalchio alludes to a line of Laberius' prologue performed before Julius Caesar on another occasion in 47 BCE, when Caesar requested that Laberius perform in his own mime, which was quite a request for a member of the equestrian order to fulfill, to take on the infamia of a public stage actor. Laberius did it and received 500,000 sesterces from Caesar along with a gold ring, significant because it symbolized his restoration to the equestrian class after having performed on stage.

The appearance of these three men in quick succession, whether through allusion or direct reference, is significant for another reason. All three men died in 43 BCE. Cicero's death is of course the most well known because he met his end in the proscriptions ordered by Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian. We do not know the specifics of Publilius Syrus or Laberius' deaths, but given the year it might be possible that they too died as a result of the proscriptions. As a part of my argument concerning the Satyrica as being in some way still suffering from a state of civil war, it seems relevant that three men who died during the fateful year of 43 BCE would show up.

#dissertation diary#dissertation#tagamemnon#Cicero#Petronius#satyricon#satyrica#me#my research#trimalchio#publilius syrus#decimus laberius

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names generated from the C0da by Michael Kirkbride

Ablamill Acesherrink Agagoddlegy Aling Alloused Altark Anchinge Ancienting Anknobeed Apejoissill Apipts Aposes Arist Asing Asymbeled Aught Avisemany...

Babluelf Bacapoles Badams Bagullown Balext Banded Banturrait Bated Becars Beres Bionstory Biscara Blasts Blothroger Boach Boady Boldes Bracalturs Bracen Bragence Brand Brang Brappregy Bried Brinfords Brings Brome Browildnele Byets Calealay Callingle Cally Carvised Caver Ceaces Chakentind Chanage Chectint Chemittly Cheriestor Clasope Cloade Clotogaze Clower Cocuthrest Coldin Comeasized Comed Comedle Comerry Congles Conscaviess Coreen Corked Coster Coting Courn Couts Crait Crawly Crifff Cringrap Cupgraposic Cutesse Cutter Dampothenty Darthes Deadeash Deards Dellock Deoner Diderty Dievecosive Digirears Discre Distarides Diterwast Dorting Drablu Draid Dreaks Drinmeal Dropeong Dukater Eadeogari Eaked Earch Earcial Eireshe Eitabraing Emard Emnatrimay Erchell Evallow Evert Exacal Excung Exhas Exialy Explatoppes Exposess Exprorts Exprowinda Facen Facking Fakes Falking Famble Faventer Favied Feader Ficks Finaporice Finimited Flample Fland Flazes Foamig Forephilve Forick Fried Frocamars Fucks Fully Fuslivine Garrint Gents Ghelooddy Giatitanses Givel Glock Godly Goond Gotiss Graged Grastart Gring Groks Guremash Hancogelf Hanotly Hansiont Hatterwart Haver Hembeasse Heming Heragoodled Hilip Hishotin Hnhomes Holting Homect Homegges Hostri Hougarna Houghty Hounsirdy Humes Ideore Illes Iltery Imebot Indings Infifyinds Itegs Jasities Joket Kicatery Kimming Kinglying Kinoth Kncialant Knicut Knoped Knormalmant Lablay Lames Lariarice Laver Lazed Lecrourel Letansit Lifing Lifter Likesce Limplath Lines Linfing Liten Lizatels Loater Locularker Lonsubt Loode Loons Loter Lulead Lumen Lummull Madight Makagand Manes Marmakily Martits Mashance Masniza Massmaket Merlied Merly Mewelfally Milique Molds Momed Momes Mormask Morrouti Mostery Movery Movis Musion Muthing Necomet Neled Nemancten Neoves Nestop Notha Nousty Numistamen Oblevat Obvies Oculting Ocutyling Offews Onspick Onted Opers Oples Ougle Ounce Pards Parth Pernives Phery Plame Plartight Plasks Plasnage Plegial Pliterivand Plittly Plusly Ponion Ponnywhing Ponter Poret Pothes Potted Prensels Prets Pride Pripeove Pritiousink Probs Prognizated Pronder Pront Prougles Prounat Purristy Putfic Quied Quiliky Quinge Quirionell Rabigh Rable Ranmed Readn Reart Reefall Reeks Refustue Rentits Rephy Retchopeary Retery Ricing Rigianiorn Roongues Rubetch Runce Safled Sagaay Salumeshing Sared Sarro Scaphod Scasetter Scaur Sciang Scorneum Scrobles Sells Selly Sellypeal Semolf Senought Serforihhh Sergethes Setted Seuma Shalive Shapookends Sheepict Shenter Shery Shignan Shime Shopes Siandanoth Siong Sirke Siviblote Skiloss Sling Slitral Smagaves Somforme Somic Soraltint Sostrize Soustelown Spartar Spelman Spikeng Splames Splath Spoledgenct Sporrage Sposer Stableaman Stabler Stoes Storkere Strableell Strabs Strazy Stuld Sultichist Surger Swesindense Taiteres Tardy Tating Teards Temeng Terancley Thash Theatits Thelf Therferient Thonexpled Thourtly Thriser Throaters Throuty Ticiany Tictsemid Tiong Tivecielly Tooryineed Toprounds Toring Torround Trices Tring Trobles Truns Tulsome Turty Tweraltel Ugled Undishing Untion Upied Ureardneld Usheading Uttle Vales Vatecone Veloa Verisend Vigant Viong Vions Viverse Volled Wathaj Wattight Wattly Waying Weirly Whalls Wheathemide Whelly Wheltats Wherfouly Whimers Whimpt Wholar Whormormod Widet Wilver Winat Windany Wininged Winshapos Woravion Worindle Wortariver Wortiory Wraninge Wreed Wroweepory Yonnels Younfons

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why can’t I listen to deo favente by le S??? Is he being canadianphobic like most French rappers when it comes to tours

0 notes

Text

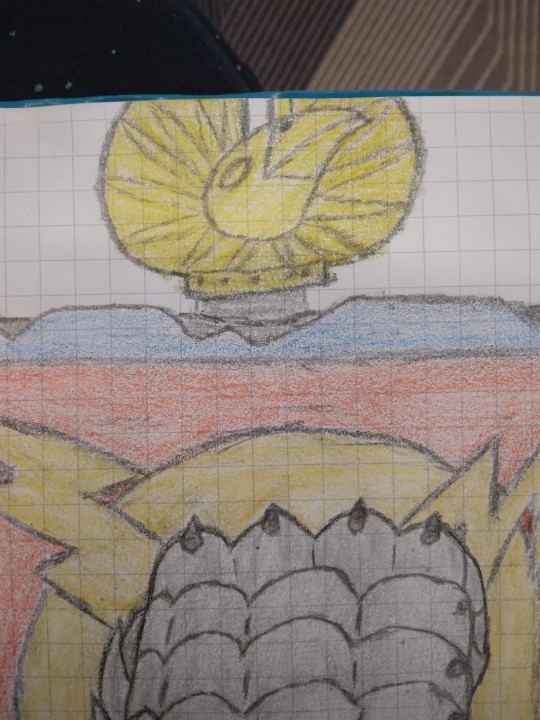

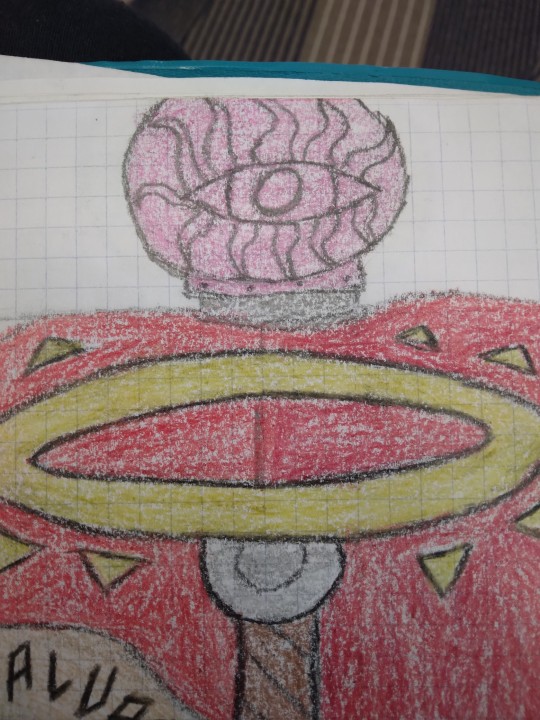

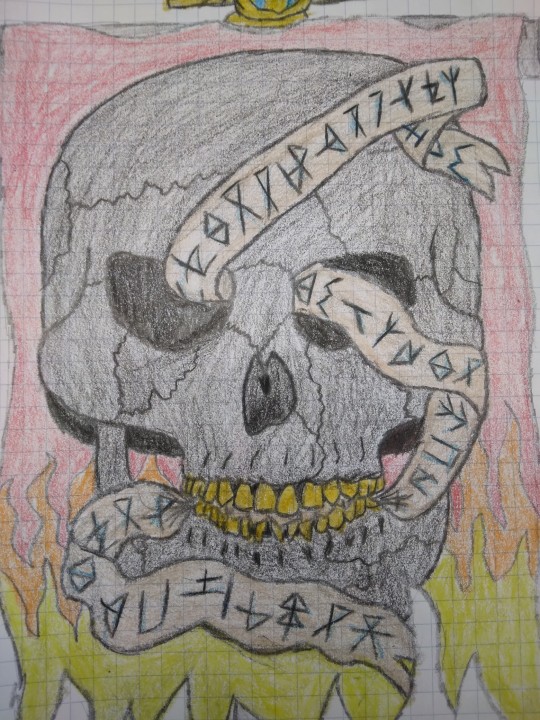

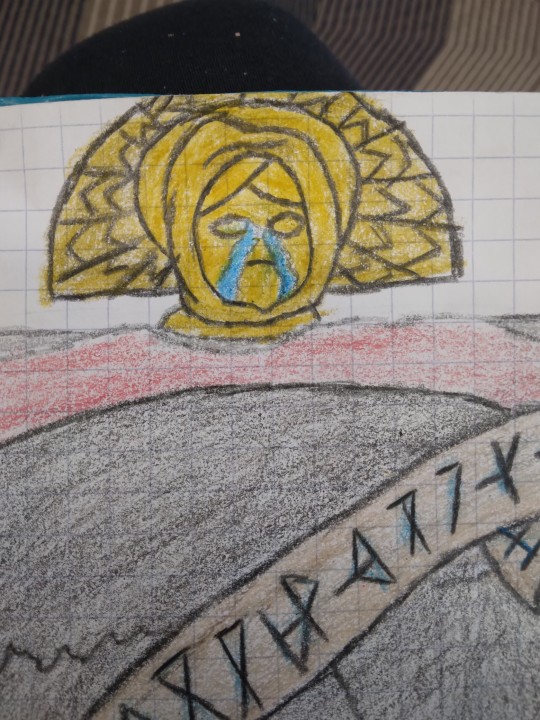

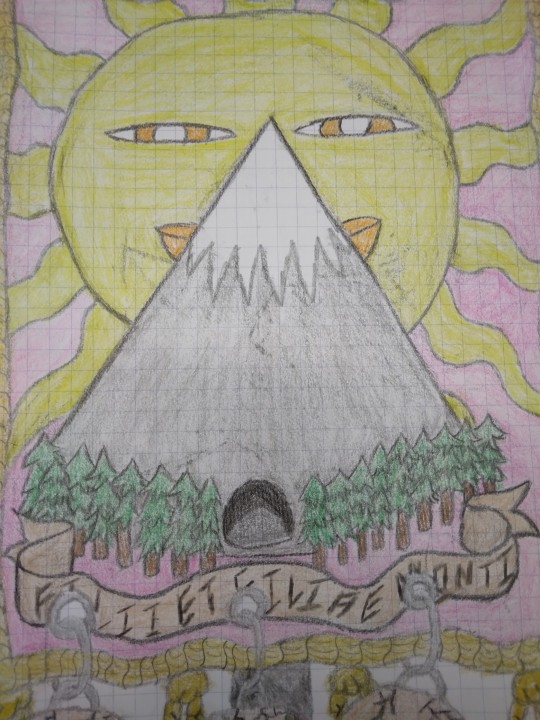

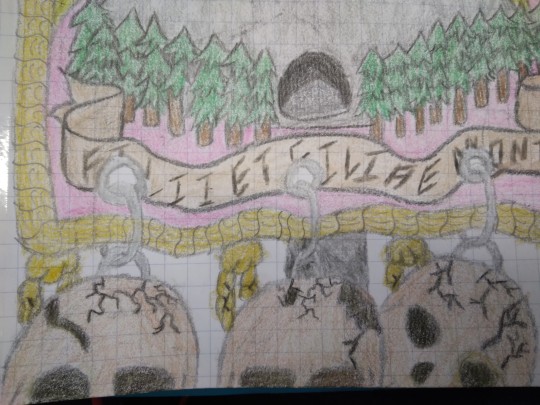

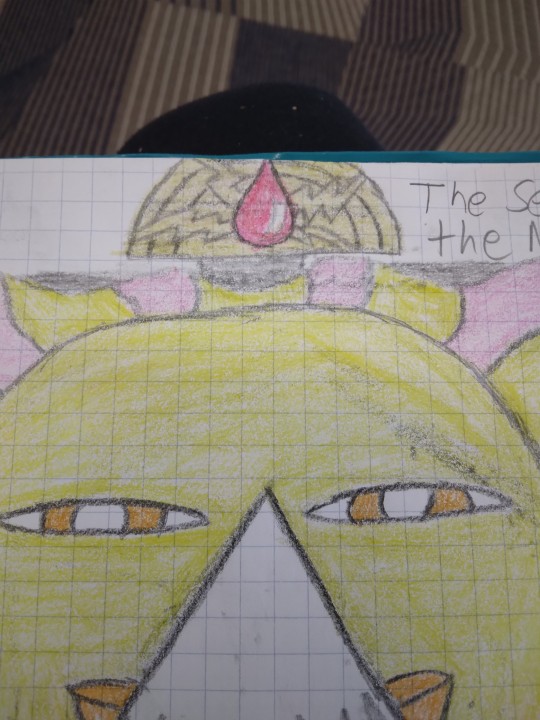

Details from the last post. In order:

The Hands of Abod, represented by a silver gauntlet with a halo of light (representing the religios focus of the fort) and lightning bolts. Their crest is a raven in gold. Their motto is "Gloria Invictus" or "Glory Unconquered."

Avus's Paladins, represented by a sword with an embellished halo on a field of red and violet red, party per pale (i think). Their crest is an eye in rose gold. Their motto is "Saluatores Nanorum" or "Saviors of the Dwarves."

The Rune Scriers, represented by a black skull with yellow teeth wrapped in a cloth banner inscribed with dwarven runes. Their crest is the weeping lady in gold and turquoise. I didn't give them a motto, but I'll go with "Favente Abod" or "Favored by Abod."

The Servants of the Mountain, represented by a mountain and a sun. Their crest is lightning bolts in gold and a ruby representing a drop of the holy blood of Avuz: the magma that flows in the earth. Their motto is "Fillii et filiae montis" or "Brothers and Sisters of the Mountain. Peep the goblin skulls hanging off the banner.

1 note

·

View note

Text

chari-favent replied to your post

and?

Yeah so I am going to offer you a friendly piece of unsolicited advice...

Saying shit like this doesn’t make you sound “cool” or “real” or #woke. It really just makes you sound like a complete sociopath.

Just something to consider.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

chari-favent

replied to your

post

:

Gun laws we need: And yes, these are harsh. 6...

ROTFLMAO have you actually looked at current gun laws? & who tf are you to tell people what to do with their property?

I’m someone who prefers not to die at the barrel of a gun owner, thanks.

Also, we get told what do with property all the time. We have to have licenses and insurance to own cars. Cities can and do tell you what to do with your yards. Why should guns be any different?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

chari-favent replied to your post: the like i think the worst thing about the...

care to elaborate?

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/opinion/trumps-scandals-a-list.html et cetera

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ca c’es juste le meilleur album à part entière, brozer y’a pas de « UNE seule track 11 », c’est juste l’EP du siecle ces tracks la qui s’appelle track 11 la

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Fair Exchange

for @rembrandtswife

Catullus 13, “ad Fabullum” In a few days (if the gods smile on you) You’ll dine well at my place, my Fabullus – If you bring with you a good and great meal (Not forgetting a girl With ivory skin, and wine, and wit, And laughter of every sort). I say again, my splendid fellow, If you bring these things, Then you’ll dine well – for your Catullus’ Purse is full of cobwebs. But in return, you’ll receive pure love, Or what’s sweeter, more graceful still: For I’ll give you a perfume that the Passions And Lusts gave to my girl, Which when you’ve smelled it, you’ll ask the gods That they make you, Fabullus, all nose.

Cenabis bene, mi Fabulle, apud me paucis, si tibi di favent, diebus, si tecum attuleris bonam atque magnam cenam, non sine candida puella et vino et sale et omnibus cachinnis. haec si, inquam, attuleris, venuste noster, cenabis bene; nam tui Catulli plenus sacculus est aranearum. sed contra accipies meros amores seu quid suavius elegantiusve est: nam unguentum dabo, quod meae puellae donarunt Veneres Cupidinesque, quod tu cum olfacies, deos rogabis, totum ut te faciant, Fabulle, nasum.

The End of Dinner, Jules-Alexandre Grün, 1913

#classics#tagamemnon#Latin#lingua latina#poem#poetry#translation#poetry in translation#Latin translation#Latin poetry#Roman poetry#Ancient Roman poetry#Catullus#lyric poetry#hendecasyllabics#Jules-Alexandre Grun

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Carolinian Friends of John Laurens: Henry Bartholomew Himeli

Bartholomew Himeli used to refer himself as a "geune ami" from Laurens, usualy calling Laurens his "cher ami", he was his French Tutor too, it looks like John started to dominate French around 1772 (around his fifties) and Himeli was pretty proud about his dominance in the language was, if his response from 1772 is something to say:

The letter

French transcription:

“Elle ma fait d'autant plus de plaisir, qu'en m'aprenant qui vous pensés a moi, elle est un monument des progrés que vous avés fait dans la Langue Francoise. Je vous avoue que j'ai été agréablement Surpris de vous voir écrire Sicorrectement une langue éthangére, & dan un âge oū plusieurs ne Favent pas même écrire pofrablement dans leur langue maternelle. Vous coups défait pres que des coups de maetre. Cela vous fait honneur Mon Cher Ami, ce'st une preuve que vous vous apliqué, & que vous prenés de la peine.”

English translation:

“She [the letter] makes me specially happy, understand that you think of me, she is a monument of the progresses that you have done at the language french. I confess you I was nicely surprised of your correctly writing in a foreign languague, & at an age where many can't write properly in their own maternal language. You blows undone almost as masterstrokes. It makes you honor My Dear Friend, this is a proof of your application and effort.”

According to his description in the Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume 16:

Henry Bartholomew Himeli was pastor of the French Protestant Church of Charleston from 1755 to 1773 and also served as French tutor to JL. He left Charleston for Switzerland in May 1773. Himeli returned to South Carolina in 1785, resting the pastorate of the French Protestant Church in Charleston, serving until his death.

According to "The Life of Gen. Francis Marion: Also Lives of Generals Moultrie and Governor Rutledge" Himeli worked as one of his firsts tutors at the side of Benjamin Lord and Panton.

According to American Heritage in his volume 27 from 1976 assures a strong influence from Himeli in the search of glory and honor of Laurens in his late life:

In particular, John's station in life meant that he was called to leadership. "The Eyes of your friends & of your Country are upon you" his father reminded him, "they are in expectation... For your own sake, for theirs & for sake of posterity disappoint them not by coming up a bundle of Carolina Rushes..." Doubtless John had received exactly the same kind of counsel from his old tutor, the Reverend B. Henri Himeli, pastor of the Huguenot Church in Charleston, for Himeli considered the minor French novelist Jean François Marmontel to be the wisest author of his age."

There's just three letters available from Himeli to Laurens and in neither of them (at a simple sight made by me) looks mentioning any kind of high expectations of glory and honor over him (moreover of an academic one) and personally I don't understand the relation between liking Jean François Marmontel-having crashing expectations over Laurens. Therefore I reserve my opinion about this until I have a proper translation and transcription of all their letters.

However, I would like to mention the high probability of a religious pressure and influence over Laurens from Himeli's part. Despite in his late life Laurens wasn't especially religious and the mentions of God wasn't exactly numerous he still wanted to join at the Seminary at a younger age, and I wouldn't be surprised if that was in part inspired by the advices of his childhood tutor, specially since while Himeli's was tutoring him was also being the Pastor of the Church.

In more personal matters, he married Rachel Villepontoux in January 8, 1768, he was the third marriage of Rachel. She died on November 23, 1771 and was her death what made Himeli consider a return to his native country, which he did until 1773.

During 1772, Himeli hoped South Carolinas would do something in Carolina for the sciences, the belles lettres, and the arts. Himeli was sure that when John returned to Carolina, he would help to do such. According to the volume 8 of the Papers of HL.

It looks like as one of his oldest tutors he knew John pretty well, if the security he had that John Laurens would invert in the art and science (all of them Laurens' likes) says something.

Himeli kept the correspondece with Henry Laurens during a long time, even before John died, however during 1783 HL started to strongly disapprove some of his actions with women.

HL's here and below concerning Himeli's marriage state may been prompted by the fact that the last time he saw him in London in October 1783. Himeli was traveling in the company of "a Trumpery Woman" of dubious Virtue, leading to HL to fear Himeli was sacrificing his honor and reputation "upon the Knees of a little Freckled Faced ordinary Wench"

Source: The papers of Henry Laurens, IX, 120-121

According to this text they assure Henry Laurens used the last example of Himeli's behavior to prevent John about selecting a "bad" wife, critizing the Himeli's multiples relationships while he was married but I wouldn't believe it all, since the worries of HL started during 1780's where John was already married, therefore an advise about marriage and partners wouldn't be specially useful, and the last anecdote takes place during 1783, when John was already dead. Therefore I consider if ever John received a advise about Himeli's behavior probably was more oriented to keeping the honor and values of a gentleman.

However, it looks like while he was tutor, John kept some appreciation for him, during 1772 he sended him a Voltaire's text and was usual from his part send greetings to Mr. Himeli:

"Be so kind my Dear Uncle as to remember me in a particulas manner, to good, add M. Manigault_ Doctor Garden, M. Himeli, M. Euselius_ and all my Friends_ God grant Health and Happiness to them all_" From this letter.

There's none record about his age of born that I can found, just a dubious source which mantains he was born at 1698, which makes him 74 at the moment John wrote that letter.

In conclusion, Himeli was a character known for being a Pastor and for his affairs with women and he will be a start of the list of John Laurens' friends, a list which despite being pretty appreciated by Laurens himself, was a list with a surprisingly amount of very religious people and specially, a list conformed for his own father's circle of friends.

Probably I missed much information about him and his relations with the Laurens here, but in my defense there's so many variations of his last name that is hard to know if it's talking about him.

#Historical John Laurens#John Laurens#Henry Laurens#Henry Bartholomew Himeli#18th century#american history#The Carolinan friends of John Laurens#But Himeli was swiss

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (more appellant choreography edition)

Finally started actually working on the Merciless Parliament section of the novelthing and then got research-blocked by the paywall at British History Online. Ugh.

Some of the dialogue at the end is drawn from Thomas Favent's account of the parliament, which is staunchly pro-Appellant, but since all the dialogue in this part of the scene is spoken by them and their supporters, I figured it was fine.

--

The Painted Chamber is crammed so full of people that the press seems almost to reach the great ceiling, scarlet-robed lords and clergy assembled in their ranks, eager to see the humiliation of a king. As the procession moves to take their seats there is a soft, anxious buzz running through the hall; Richard has the sudden impression that he is inside a nest of unusually subdued wasps.

It has never been the practice for the Queen to attend Parliament; Richard has sometimes regretted that, but never more so than now. There are hundreds of people in the hall, and yet Richard knows himself to be completely alone. He reaches for the paternoster looped through his belt, a string of coral beads with blue ones interspersed, a silver Saint Anne medallion at one end and a crowned A, also in silver, at the other—Anne usually carries it with her everywhere she goes, but she gave it to him before he left for Parliament this morning, to remind him that she would be with him in spirit. He passes the beads through his fingers, cool and smooth against his skin, but the prayers slide away from his mind just as easily. He wishes Anne could be with him in body as well. With her at his side, perhaps he could bear this. She has promised to pray for him continually, not to rise from her knees until he returns.

It’s going to be a long day. He makes a mental note to have a hot bath drawn when the session is over. She’ll need it as much as he will.

Assuming, of course, the lords will permit him a servant to carry the water.

Richard is barely enthroned when the great doors of the hall swing open again to reveal the five appellants, standing together arm in arm, dressed in identical garments of cloth-of-gold. They walk in step as they make their way down the aisle, heads held high and faces smug. They must have practiced, Richard thinks, and the mental image of them arguing over their places in the line—and Henry Bolingbroke insisting he isn’t the shortest appellant—provides him with an instant of grim amusement. Then they kneel before him as one, so fluid once again as to have been rehearsed, but the smug expressions don’t leave their faces for a moment, and Richard wants to be sick.

Instead, he nods curtly in their direction, and does not signal for them to stand. Bishop Arundel, in his capacity as Lord Chancellor, has to make the customary speech about the parliamentary agenda; they can remain on their knees until he’s finished. And if Bishop Arundel objects to his brother having to kneel at length, he can abbreviate his speech accordingly. It’s petty, Richard knows, but they are forcing him to sit and watch as they condemn all his friends. A little spite is far, far less than they deserve. His fingers return to Anne’s beads, fondling them almost absently as Bishop Arundel drones on.

Plesyngton, the chief baron of the Exchequer, rises to his feet once the Lord Chancellor has concluded, to speak on behalf of the appellants. “Here is the Duke of Gloucester,” he says, “who has come to purge himself of the charge of treason made against him by the fugitives de Vere, la Pole, Neville, Tresilian, and Brembre.”

Richard looks at him for a moment, and then at the faces of each of the appellants in turn. None of them displays a trace of humility, not even Henry Bolingbroke, who had been so discomfited the last time the two of them had spoken privately. Perhaps he’s convinced himself that his magnanimity outweighs any cause he might have had for remorse. Richard wishes Henry were kneeling a bit closer to him, so that he could kick him.

Resisting the urge to roll his eyes, he nods again, only once, and the five of them rise to their feet. He does not address them directly, but Bishop Arundel steps in immediately to fill the silence.

“My lord duke,” the bishop says, “you have arisen from so worthy a royal line, and we find that you are so closely related to him in the collateral line, that no such plot could be suspected of you.”

Again, Richard is sorely tempted to roll his eyes. As if being someone’s close relation means you can’t plot against him. Bishop Arundel should know full well that there are few sins older than that: the first man ever to die was struck down by his own brother.

“I humbly thank your Highness,” Gloucester says, just as if it had been Richard who had spoken. “I would have it known, before this whole parliament, that neither I nor any of the men with me have ever sought or planned your Highness’s death, whether covertly or openly, and if necessary, we will defend ourselves against these accusations against any man alive…” He looks Richard in the eye for just a moment, and adds, “…excepting your Highness, of course.”

#the novelthing#richard ii#sunday snippet#it's not called the 'gently showing richard the error of his ways parliament'#also: anne's paternoster isn't based directly on a real artifact but does show up in the bad pregnancy timing au#it's the same one that in that au she gives to neddy when arundel takes him away

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

- E lo princep respos al almirall: -Ques aço que vos volets que yo hi faça? que si fer yo puch , -volenters ho fare.- Yo , dix lalmirall , quem façats ades venir la filla del rey Manfre, germana de madona la regina Darago, que vos tenits en vostra preso aci el castell del Hou , ab aquelles dones e donzelles qui soes bi sien ; e quem façats lo castell e la vila Discle retre . - E lo princep respos , queu faria volenters. E tantost trames un seu cavaller en terra ab un leny armat, e amena madona la infanta , germana de madona la regina , ab quatre donzelles e dues dones viudes. E lalmirall reebe les ab gran goig e ab gran alegre , e ajenollas, e besa la ma a madona la infanta.

Ramon Muntaner, CRÓNICA CATALANA, p. 221

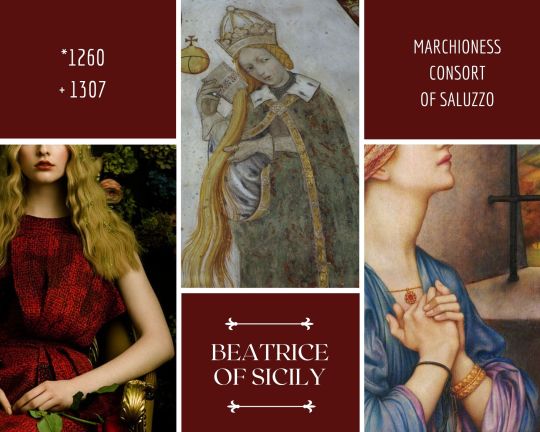

Beatrice was born (probably) in Palermo around 1260. She was the first child and only daughter of Manfredi I of Sicily and his second wife, the Epirote princess Helena Angelina Doukaina (“[…] et idem helenam despoti regis emathie filiam sibi matrimonialiter coppulavit, ex quibus nata fuit Beatrix.”, Bartholomaeus de Neocastro, Historia Sicula, in Giuseppe Del Re, Cronisti e Scrittori sincroni Napoletani editi ed inediti, p. 419). It’s quite plausible the baby had been named after Manfredi’s first wife, Beatrice of Savoy (mother of Costanza, who will later become Queen consort of Aragon and co-regnant of Sicily). The little princess would soon be followed by three brothers: Enrico, Federico and Enzo (also called Anselmo or Azzolino). With three sons, Manfredi must have thought his succession was secured.

Beatrice’s father was one Federico II of Sicily’s many illegitimate children, although born from his most beloved mistress (and possibly fourth and last wife), Bianca Lancia. Since his father’s death in 1250, Manfredi had governed the Kingdom of Sicily on behalf firstly of his (legitimate) half-brother Corrado and, after his death in 1254, of Corrado’s son, Corradino. In 1258, two years prior Beatrice’s birth, Manfredi had been crowned King of Sicily in Palermo’s Cathedral, de facto usurping his half-nephew’s rights.

Like it had happened with Federico, Manfredi was soon opposed by the Papacy, which didn’t approve of the Hohenstaufen’s rule over Sicily (and Southern Italy with it) and the role of the King as the champion of the Ghibellines faction. In 1263, Urban VI managed to convince Charles of Anjou, younger brother of Louis IX the Saint, to present himself as a contender to the Sicilian throne. Three years later, on January 6th 1266, the French duke was crowned King of Sicily by the Pope in Rome, thus overthrowing Manfredi. On February 26th, in Benevento, the usurped King then tried to get back his kingdom by facing Charles in the open field, but failed and lost his life while fighting.

The now widowed Queen Helena had previously fled to Lucera (in Apulia) with her children (Beatrice was now six), her sister-in-law Costanza, and her step-daughter, the illegitimate Flordelis, where she thought they would be safer. When they got news of the disaster of Benevento and Manfredi’s death, they fled to Trani from where they planned to set off to Epirus. The unfortunate party was instead betrayed and handed off to the Angevin. On March 6th night, Helena and the children were taken hostage and later separated. The Queen was sent at first to Lagopesole (in Basilicata) and finally to Nocera Christianorum (now Nocera Inferiore), where she would die still in captivity in 1271.

Enrico, Federico and Enzo were taken to Castel del Monte. Following Corradino’s death in 1268, Manfredi’s young sons (the oldest, Enrico, was just four at the time of his capture) were, to all effects, the rightful heirs to the Sicilian throne. It’s undoubtful Charles must have wanted them gone, or at least forgotten. In 1300 they were moved to Naples, in Castel dell’Ovo (which, at that time, was called San Salvatore a mare), under the order of the new Angevin king, Charles II. According to some sources, Federico and Enzo died there within the short span of a year. As for Enrico, he died alone and miserable in October 1318, he was 56.

As for Beatrice, her fate was more merciful compared to that of her mother and brothers and, for that, she had to thank her sex, which made her harmless in Charles’ eyes (as long as she was left unmarried). After being separated from her family (she will never see them again), the six years old princess was, like her brothers, held captive (although not together) in Castel del Monte. In 1271, she was moved to Naples, in Castel dell’Ovo, under the guardianship of its keeper, a French nobleman called either Landolfo or Radolfo Ytolant. Manfredi’s daughter is mentioned in a rescript of Charles dated March 5th 1272, from which we learn she had been granted at least a maid (“V Marcii xv indictionis. Neapoli. Scriptum est Iustitiario et erario Terre laboris etc. Cum ex computo facto per magistrum rationalem Nicolaum Buccellum etc. cum Landulfo milite castellano castri nostri Salvatoris ad mare de Neapoli pro expensis filie quondam Manfridi Principis Tarentini et damicelle sue. ac filie quondam comitis Iordani et damicelle sue dicto castellano in unc. auri novem et taren. sex de pecunia presentis generalis subventionis residuorum quolibet vel qua canque alia etc. persolvatis. non obstante etc. Recepturus etc.”, Monumenti n. XLIV. in Domenico Forges Davanzati, Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su’ loro figliuoli, p. XLIII-XLIV). Like it had happened with her mother, and unlike her brothers, it appears Beatrice was treated with courtesy and respect. In her misfortune, she could count on the company of a fellow prisoner and distant relative, the daughter of Giordano Lancia d’Agliano, who was her grandmother Bianca Lancia’s cousin and had been a loyal supporter of her father, Manfredi.

On Easter Day of 1282, an anti-Angevin rebellion sparkled in Palermo would soon transform itself into a war to get rid of the so much hated Frenchmen, the so-called War of the Sicilian Vespers. It’s dubious that, close in her prison, Beatrice came to know about it. She might have also been surprised to know that her half-sister, Costanza, had been asked by a delegation of fellow Sicilians to take possession of what was hers by right (the throne) as she was their “naturalis domina”. Her rights were shared with her husband, Pedro III of Aragon, who would personally take part in the war and be rewarded with a joint coronation in November 1282.

For Beatrice, everything changed in 1284. On June 4th, Italian Admiral Ruggero di Lauria, at the service of the Aragonese King (he was also Costanza’s milk brother), defeated the Angevin fleet just offshore from Naples and took Carlo II prisoner. Being in clear superiority, the Sicilians could now demand (among many requests) the release of Princess Beatrice. Carlo’s eldest son and heir, Carlo Martello Prince of Salerno, could nothing other than obliging them. (“Siciliani autem , & omnes faventes Petro Aragonum, incontinenti de ipsorum victoria plurimum exultantes, Nuncios, & Legatos ad quoddam Castrum ex parte Principis direxerunt , ubi quaedam filia quondam Domini Regis Manfredi sub custodia tenebatur , ut dicta filia fine ullo remedio laxaretur , quae statim fuit antedictis Legatis , & Nunciis restituta.”, Anonimo Regiense, Memoriale Potestatum Regiensium. Gestorumque iis Temporibus. Ab anno 1154 usque ad Annum 1290, in Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Rerum Italicarum scriptores ab anno aerae christianae quingentesimo ad millesimumquingentesimum, vol. VIII, p. 1158).

Beatrice, finally free, left Castel dell’Ovo headed for Capri, where the Admiral was waiting for her. She had spent 18 long years in captivity and was now 24. From Capri she reached Sicily, where she was warmly welcomed and with a lot of enthusiasm, to meet her half-sister Costanza.

As the Queen’s closest free relative (both Pedro and Costanza had no interest in asking for Enrico’s release since, as a male, he had more rights than Costanza to inherit the throne), Beatrice had a great political value. At first, Ranieri Della Gherardesca’s name came up. He was the son of that Count Gherardo who had fought together with the unfortunate Corradino (the sisters’ royal cousin), and for that had been beheaded in Naples in 1268 alongside his liege. Finally the perfect candidate was found. Manfredo of Saluzzo was born in 1262 and was the son of Marquis Tommaso I and his wife Luigia of Ceva. Like Beatrice, Manfredo was strongly related to Costanza, specifically, he was her nephew since Tommaso and the Sicilian Queen were half-siblings (they were both Beatrice of Savoy’s children).

The marriage contract between the two is dated July 3rd 1286 and the contracting parties are on one side “la serenissima signora constanza regina dy aragon e dy sicilia e dil ducato de puglia principato di capua” and, on the other side “il marchexe thomas di sa lucio signore de conio una cum mạdona alexia soa moglie”. Tommaso declares that Manfredi will inherit his title, privileges and possession upon his death. If, after the marriage is celebrated, Manfredi were to die first, Beatrice would enjoy possession of the castle and some properties. The Marquise Luisa declares to agree with her husband’s decision (“[…] e a tuto questo la marchexa aloysia madre dy manfredo consenty”, Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 165-166). The union was formally celebrated the year after.

Beatrice bore Manfredi two children: Caterina and Federico, born presumably in 1287 (“Et da questa beatrix haue uno figlolo chiamato fredericho et una figlola chiamata Kterina” Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 185). In 1296 Tommaso died, so Manfredi inherited the marquisate and Beatrice became Marquise consort of Saluzzo. She will die eleven years later at 47, on November 19th 1307 (“Venne a morte nel dì 19 novembre di quest’anno Beatrice di Sicilia moglie del nostro marchese Manfredo, e noi ne accertiamo il segnato giorno col mezzo del rituale del monastero di Revello , nel quale leggesi annotato: 19 novembris anniversarium d. Beatricis filiae quondam d. Manfredi regis Ceciliae et uxoris d. Manfredi primogeniti d. Thomae marchionis Saluciarum, quae huic monasterio quingen- tas untias in suo testamento legavit.” Delfino Muletti, Memorie storico-diplomatiche appartenenti alla città ed ai marchesi di Saluzzo, vol III, p. 76). Her husband would quickly remarry with Isabella Doria, daughter of Genoese patricians Bernabò Doria and Eleonora Fieschi. Isabella would give birth to five more children: Manfredi, Bonifacio, Teodoro, Violante and Eleonora.

As of Beatrice’s children, Caterina would marry Guglielmo Enganna, Lord of Barge (“Catherina figlola dy manfredo e de la prima moglie fu sorella dy padre e dy madre dy fede rico e fu moglie duno missere gulielmo ingana capo dy parte gebellina in questy cartiery dil pie monty verso bargie.”, Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 256). Federico’s fate would be more complicated. Like many mothers before and after her, Isabella Doria wished to see her own firstborn, Manfredi, succeeded his father rather than her step-son. The new Marchioness of Saluzzo successfully instigated her husband against his son to the point the Marquis. in a donatio mortis causa dated 1325, disinherited Federico in favour of the second son (Federico would have settled with just his late mother’s belongings), Manfredi (“Et questo faceua a instigatione de la moglie che lo infestaua a cossi fare.” Gioffredo Della Chiesa, Cronaca di Saluzzo, p. 224). Federico’s natural rights were later acknowledged by an arbitral award proclaimed in 1329 by his paternal uncles Giovanni and Giorgio of Saluzzo, and finally, an arbitration verdict dated 1334 and issued by Guglielmo Earl of Biandrate and Aimone of Savoy. As a condition of peace, the future Marquis should have granted his younger brother the castle and villa of Cardè as a fief. Stung by this defeat, Manfredi IV, his wife Isabella and beloved son Manfredi retired to Cortemilla. Federico died in 1336 and was succeeded by his son Tommaso, who would inherit his father’s rights and feud with the two Manfredi's. After being defeated by his half-uncle in 1341 (the older Manfredi, his grandfather, had died the year before), resulting in losing his titles, possessions and freedom, Tommaso would later regain what was of his right and rule as Marquis of Saluzzo.

Sources

-ANONIMO REGIENSE, Memoriale Potestatum Regiensium. Gestorumque iis Temporibus. Ab anno 1154 usque ad Annum 1290, in Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Rerum Italicarum scriptores ab anno aerae christianae quingentesimo ad millesimumquingentesimum, vol. VIII

-BARTHOLOMAEUS DE NEOCASTRO, Historia Sicula, in Giuseppe Del Re, Cronisti e Scrittori sincroni Napoletani editi ed inediti

- DEL GIUDICE GIUSEPPE, La famiglia di Re Manfredi

- DELLA CHIESA, GIOFFREDO, Cronaca di Saluzzo

-FORGES DAVANZATI, DOMENICO, Dissertazione sulla seconda moglie del re Manfredi e su’ loro figliuoli

- LANCIA, MANFREDI, Il complicato matrimonio di Beatrice di Sicilia

-Monferrato. Saluzzo

-MULETTI, DELFINO, Memorie storico-diplomatiche appartenenti alla città ed ai marchesi di Saluzzo, vol II-III

- MUNTANER, RAMON, Crónica catalana

- SABA MALASPINA, Rerum Sicularum

- SAVIO, CARLO FEDELE, Cardè. Cenni storici (1207-1922)

-Sicily/Naples: Counts & Kings

#women#history#women in history#historical women#history of women#beatrice of sicily#manfredi i#helena angelina doukaina#costanza ii#manfredi iv of saluzzo#federico of saluzzo#caterina of saluzzo#House of Hohenstaufen#norman swabian sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#house of saluzzo#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

46 notes

·

View notes