#fall of bukhara

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Enter Mikhail Frunze and the Fall of the Last Emirs in Central Asia 1920-1921

From 1917 to 1919, Central Asia was cut off from Moscow and the Red Army. This allowed events in the Steppe and Turkestan to take their own course with a regionalized flavor. Beginning in 1919, that all ended with the defeat of the White Army in the Kazakh Steppe, the absorption of the Alash Orda by the Bolsheviks, and the arrival of the Turkestan Commission also known as the Turkkomissiia. After ensuring the Steppe would no longer be a problem, General Mikhail Frunze and the Red Army followed and upending existing relations between the Bolsheviks and the local peoples of Central Asia.

Mikhail Frunze: the Wrecking Ball

Frunze was born in Bishkek in modern-day Kyrgyzstan. At the age of eighteen, he was involved in the split between the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks, siding with the Bolsheviks. He took part in the 1905 Revolution that led to the creation of the Duma, during the Revolution he was arrested and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to hard labor, and he spent ten years working in Siberia. In February 1917, he was in Minsk before traveling to Moscow to take part in the fight for the city.

In 1919, he was appointed the head of the Southern Army Group of the Red Army Eastern Front and fought against Admiral Alexander Kolchak’s White Army in the Steppe. He would defeat Kolchak at the end of 1919, bringing the Steppe under Bolshevik control and subsuming the Alash Orda into Bolshevik forces. In February 1920, he traveled to Tashkent to take part in the Turkkomissiia, a special commission sent to Turkestan to help establish a Bolshevik government in the region. One that would rely on the Red Army to ensure its edicts for the foreseeable future.

The Turkkomissiia attempted to work with local organizations until Frunze arrived in February 1920. Even though he would only remain in the region until September 1920, Frunze was a wrecking ball in a China shop, destroying former understandings among the Indigenous peoples and wiping out old enemies that had plagued the Bolsheviks in Central Asia since the Revolution.

Frunze arriving in Turkestan

[Image Description: A color gif of a short, old white woman with curly hair. She is wearing all white work out clothes and black and white sneakers. She is riding a black wrecking balln through grey walls.]

When Frunze arrived, he identified the following issues immediately:

The Musburo’s bid for autonomy jeopardizing the Bolshevik experiment in Central Asia.

Turkestan has three dangerous neighbors-Khiva, Bukhara, and Afghanistan-that Britain could use to undermine the Bolsheviks in Central Asia

“A fucking insurgency, guys? Really?”

Also, do you think maybe if people weren’t starving, they wouldn’t join the Basmachi?

During this episode we’ll discuss how Frunze took on the Musburo, Khiva, and Bukhara. In a future episode we’ll discuss how Frunze dealt with the Basmachi.

Frunze vs Musburo

When the Turkkomissiia arrived, Risqulov and the Musburo greeted them with joy, believing they would help the Musburo expand its authority throughout Turkestan. However, Frunze was distrustful of the Musburo, claiming that they weren’t communist enough and that their cause was nothing more than a “narrow, petty, bourgeois nationalism” (pg. 114, Making Uzbekistan). He also attacked the Communist Party of Turkestan (KPT), proposing, in April 1920, that they should disband the existing party and start over. Instead, the Turkkomissiia launched a purge, weeding out 42% of the party’s members. They purge the ranks again in 1922 by 30%, reducing the ranks to 15,000 members. It would grow to 24,000 in 1924.

Mikhail Frunze

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a man with round cheeks in a grey military uniform. He has a thick mustache. He is wearing a pointy hat with a yellow star. The jacket has a collar. He is also wearing two medals and a leather belt that runs across his chest.]

Risqulov and other Muslims and Indigenous peoples fought back by lackadaisically carrying out Turkkomissiia orders and sent complains to Moscow about Russia’s high-handedness. G’ozi Yunus, a Jadid turned member of the Musburo, wrote the following about the Bolsheviks:

“[the party contained] a group of narrow nationalists having washed their hands with the blood of the people, put on the mask of Bolsheviks or Left SRs and cleansed the uezd of its Muslim… naturally given that the Soviet government established in 1918 was headed by narrow nationalist comrades, complaints about such behavior was ineffective.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 115

In May 1920, Risqulov would write:

“In Turkestan as in the entire colonial East, two dominant groups have existed and [continue to] exist in the social struggle: the oppressed, exploited colonial natives, and European capital.” Imperial powers sent “their best exploiters and functionaries” to the colonies, people who liked to think that “even a worker is a representative of a higher culture than the natives, a so-called “Kulturtrager.” - Adeeb Khalid, Central Asia, pg. 115

And in June 1920, Risqulov would argue:

“In Turkestan there was no October revolution. The Russians took power and that was the end of it; in the place of some governor sits a worker and that’s all.” “The October revolution in Turkestan should have been accomplished not only under the slogans of the overthrow of the existing bourgeois power, but also of the final destruction of all traces of the legacy of all possible colonialist efforts on the part of Tsarist officialdom and kulaks.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg.108-109

Frunze seems to have legitimately believed that the Muslims of Central Asia didn’t truly understand Communism and that the Musburo was a hybrid form of government that needed to be cleansed of nationalists. From a pragmatic perspective, the situation in Turkestan was chaotic and needed a firm hand to establish any form of government, let alone a communist government. Frunze, naturally, believed the best way to bring order was to simplify command and grant power to those he could rely on and were dedicated to the correct version of communism. The Musburo, KPT, and whatever remained of the Kokand Autonomy and the Tashkent Soviet had proven too weak to rule on their own and he had no need for their skills since he brought with him the Red Army full of officers and Bolsheviks agents, he knew he could rely on. As we’ll see, Frunze would allow Indigenous peoples of Central Asia to work in governmental positions, but he wanted to start fresh and establish a form of command he understood and knew.

It should also be noted that Frunze did not favor Russian settlers over the Muslim populations of Central Asia. He also banished local communist organizations of Russian railroad workers, the same men who led minor revolts like Osipov’s revolt of 1919. In fact, there were rumors that they were planning a similar revolt against the Turkkomissiia who they felt were too friendly with the non-Russian inhabitants of Central Asia. So, while there is certainly xenophobia and racism involved in Frunze’s decisions, there is also an element of pragmaticism going on, but also note that Russian racism and chauvinism really outdoes itself in Central Asia and deserves deep, scholarly investigation that is beyond this podcast.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A black and white pciture of a man standing at an angle. He is looking at the camera. He has bushy black hair and a short mustache. He is wearing round, wire frame glasses. His hands are in his dark grey suit pants. he is wearing a white button down shirt, a grey tie, and a dark grey vest and suit jacket. A flag is pinned to his suit lapel.]

Risqulov and the Muslim Communists went around Frunze and the Turkkomissiia and traveled directly to Moscow to speak with Lenin. The Turkkomissiia also went to Moscow to present their case. Risqulov argued that the Turkkomissiia were undermining the Musburo’s efforts, that Turkestan was the key to spreading Communism throughout the east and that it should be its own republic with full autonomy to print its own money and conduct its own foreign policy. Lenin ignored Risqulov’s arguments and sided with Frunze.

On June 22nd, 1920, the Politburo passed a resolution that formerly brought Turkestan under Soviet control. It stripped Turkestan of control over external relations, external trade, and military affairs. Its economic and food-supply policies had to fit within the plans established by the central government of the Soviet Union. It claimed that.

“Recognizing the Kazakhs, Uzbeks, and Turk-mens as the Indigenous peoples of Turkestan the Turkestan Soviet Socialist Republic…as an autonomous part of the RSFSR” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg.115

They also transformed the Turkkomissiia into the Turkestan Bureau which then changed to the Central Asia Bureau (Sredazburo) were it served as a mechanism of Central Power. Risqulov and his party were defeated in a forced re-election with Risqulov sent to several desk jobs far from Turkestan. The Sredazburo also arrested several “nationalists” and deported nearly 2000 Europeans from the region.

While this effort put an end to the Musburo and the Communist Nationalist’s grip on power within Turkestan, it didn’t permanently end indigenous power. Instead, it set new parameters on who could exercise that power and how. Many of the Muslim actors affected by Frunze’s destruction of the Musburo (including Risqulov) would return to Central Asia and hold varying degrees of power. Frunze wasn’t against the Indigenous peoples of Turkestan holding power, in fact as he struggled to reassert Soviet control over the region, he realized he needed Indigenous actors to legitimize Bolshevik rule and Communist thought. But he also believed that they needed to follow the Communist Party’s ethos, edicts, and governmental framework.

After ending the “threat” of Muslim nationalism within Tashkent, Frunze followed the tradition of the Tashkent Soviet and first attack Khiva in February 1920 and Bukhara in August 1920.

Frunze vs. Khiva

What has Khiva been up to?

When last we left Khiva, Junaid Khan, a warlord, extorted Khiva’s Emir then had him assassinated and replaced him with his brother Sayid Abdullah as a puppet. Junaid consolidated his power by creating a government of local military commanders and raised taxes on the Uzbek population while demanding that the Turkmen arm themselves for compulsory military service. There were frequent disturbances throughout the spring and summer of 1918, but nothing truly threatened Junaid’s control. He established the city capital at Bedirkent, where he began the construction of a palace.

Junaid Attacks the Bolsheviks

After destroying any internal threats to his rule, Junaid decided to raid the nearby Russian outposts. He first attacked the city of Urgench on September 20th, 1918, stealing money and goods from Russian banks and firms. The Russians demanded the release of prisoners and Junaid complied but warned them against interfering in Khivan affairs.

Junaid regarded the Bolsheviks as enemies, not for any ideological reason, but because they threatened his own personal fiefdom. The Russian outpost at then Petro-Aleksandrovsk was an incursion in Khiva’s natural line of defense. Junaid attacked the outpost on November 25th, 1918, believing winter would make it impossible to assist the outpost. He laid siege for eleven days before being chased off by Russian reinforcements. Junaid spent the spring of 1919 attacking Russians garrisons, but his losses were greater than his victories so on April 9th, 1919, he signed the Treaty of Takhta with the Russian forces. This treaty ended hostilities immediately, reaffirmed Khiva’s independence, established normal diplomatic and trade relations, and amnesty for all Turkmen charged with anti-Bolshevik activities.

Junaid did not follow the treaty, rebuffing the Bolshevik diplomatic representative sent from Tashkent in July, refusing to extradite Russian criminals finding shelter in Khiva, and selling grain to Turkestan. He allowed the Russians to rebuild the telegraph line between Chardjui and Petro-Aleksandrovsk but would not guarantee its safety in the future.

Relations between Khiva and the Bolshevik forces in Turkestan fell to an all-time low in the summer of 1919, when Junaid supported a group of rebel Cossacks fighting against the Bolsheviks. This group of Ural Cossacks stationed themselves at Chimbai in the Amu-Darya region. By mid-August, the Cossacks, with aid from the Karakalpak people controlled the entire delta from the Aral Sea south to Nukus and across the river from Khodjeili. Russian naval commander Shaidakov returned to Petro-Aleksandrovsk on August 19th and took commander of the newly formed Khivan army group of the Transcaspian front. When he tried to suppress the Cossack uprising using steamboats to ferry his men to battle, he was fired upon by Junaid’s patrols. Junaid also cut the telegraph lines to Chardjui and was discussing a joint attack on Petro-Aleksandrovsk with the Cossacks. By September, Tashkent feared a Khivan invasion.

The Fall of Khiva

By the fall of 1919, military events turned in the Bolshevik’s favor. Frunze and the Red armies were defeating Kolchak’s and Dutov’s forces in the Steppe and were seeing success in their Transcaspian campaign. Additionally, the small faction of Jadids in Khiva, who now called themselves the Young Khivans, had gained recognition from the Turkestani government. The Young Khivans themselves claimed to have a militia of five hundred men and secret underground cell in the capital. Frunze declared that both Khiva and Bukhara needed to be liberated from the tyranny of the Khans. The only reason he overthrew Khiva’s khanate first was because Junaid had made too much of a nuisance of himself to ignore and because he was protecting the Cossacks at Amu-Darya.

Frunze ordered G. B. Skalov, the recently appointed representative for Khiva and the Amu-Darya Otdel, to liberate Khiva. The Russians would prepare for their assault while fending off multiple attacks from Junaid’s forces in November and December of 1919.

Skalov began his attack in January 1920. He had two columns of men at his command. The first column, station at Petro-Aleksandrovsk, consisted of 430 men. They would first approach from the northeast, targeting cities such as Khanki and Urgench, before turning and attacking Junaid’s headquarters in Bedirkent from the south. The second column consisted of four hundred men and was commanded by N. A. Shaidakov. They would approach the capital from the northwest. (Becker, 287). Skalov easily took the city of Khanki, but he was besieged for three weeks at Urgench. Shaidakov, however, easily defeated a group of Cossacks and Karakalpak rebels near Chimbai and captured two more cities on their way to the capital.

Skalov broke the siege at Urgench and approached Bedirkent from the south while Shaidakov approached from the north. They fought for two days with Junaid’s own commanders and allies turning against him. Bedirkent fell on January 23rd, 1920, with Junaid fleeing into the Kara-Kum Desert. From there he would form a new branch of the Basmachi and return to being a thorn in the Bolshevik’s side. The Bolsheviks forced the puppet khan to abdicate and replaced him with a revolutionary committee composed of two Young Khivans, and two Turkmen chieftains. With Junaid out of the way the Bolsheviks were able to concentrate on destroying the Cossack revolt in Amu-Darya.

On February 8th, the Young Khivans requested aid from the Bolsheviks in creating a workers’ and peasants’ government and a congress of Soviets arrived on April 1st to assist the Young Khivans. At the end of April, the khanate was formally abolished, and the Khorezm People’s Soviet Republic took its place as the only legitimate government in Khiva. A Khorezmi Communist Party formed at the end of May, boosting six hundred members by the summer of 1920, although records suggest that most of these members were Russian or Turkestani Communists.

Frunze vs Bukhara

Catching up with Bukhara

When last we left Bukhara in March 1918, the Tashkent Soviet tried and failed to invade, signing a humiliating agreement that let the Emir live for another day which allowed him to hunt the Jadids, who renamed themselves the Young Bukharans. Many fled to Tashkent and reunited with the Jadids there and met with Communist officials.

Soviet historians have painted the Bukharan Emir as an inherently hostile foe, making deals with everyone from the Emir of Afghanistan to the white Army to the British, always ready to strike against the Russian forces. Their paranoia over Bukhara increased because of the growing threat in the Transcaspia, which is beyond the scope of this podcast, but was receiving heavy British support. Junaid never fully committed to the Transcaspia front but attacked the Russian’s communication lines and soldiers. If Emir Muhammad Alim Khan chose to support the forces in Transcaspia, then the Russians in Tashkent would be surrounded by enemies with British backing.

In reality, the Emir was a cautionary man, far more caution than Junaid in Khiva. He did not like or trust the Russians, but he wasn’t ready to start a war with them. It seems that he was waiting out the various wars and battles to determine who would be his true competitor or potential ally. He most certainly hoped to break from Russian influence, but that never seemed completely feasible. Even though the Russian forces were weak in Tashkent in 1918 and into 1919, they still controlled the railroad zone that cut through the heart of the khanate and Samarkand, the key to western Bukhara’s water supply. At some point I will have to do an episode or blog post on water rights in Central Asia, because it’s vital to understanding Russian colonialism in the region and still affects the states to this day. So, the Bukharan Emir chose neutrality.

The situation in Transcaspia grew worse for the Russians during the summer of 1918 when British support enabled Transcaspia to stall the Russian assault. The Emir opened a consulate at Merv, Iran, where the British General Malleson made his headquarters, but it was mostly for observation and a channel of communication and intelligence gathering. He had talks with the British about their intentions in Britain. Malleson sent a small collection of arms to Bukhara in February as a token of friendship, but also urged the Emir not to provoke Tashkent. This confirmed the Russian’s fear that Bukhara had allied with Britain and were receiving arms, training, and supplies. The evacuation of the British from Transcaspia in early 1919 did nothing to slow these rumors down.

Emir Muhammad Alim Khan had grown his army to thirty thousand men in preparation for war in Central Asia, but whatever shipments he may have received from Britain did nothing to substantially help Bukhara. Even if the Emir was not prepared for war himself, he kept his land open to members of the Basmachi and other anti-Communist forces. Turkestan asked Bukhara to extradite all fugitives per the treaty they signed in March 1918, but the Emir refused.

Emir Muhammad Alim Khan

[image Description: A color picture of a large man sitting on a chair. He is wearing a white turban, a blue robe embroidered with several kind of flowers, and black, leather books. He is resting a sword against his right thigh. He has a bushy, circular beard. Behind him are stone walls with two wooden doors.]

Relations hits a new low when the British evacuated Transcaspia and the resistant forces sent forces to the Bukharan city of Kerki to try and get behind the Russian’s rear before they could press their advantage. The Russians attacked, believing the Bukharan officials in the city were collaborators with the rebels. They took the town but were then blocked by the emir’s troops. A truce was arranged long enough for the Russians to expel the Transcaspian rebels in the rural areas of Kerki, but the blockade continued for another month. Bukharan forces even fired upon the Soviet embassy on their way to Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, the British kept telling the Emir to remain neutral. Malleson wasn’t necessarily worried about Bukhara attacking the Bolsheviks as he was about Bukhara making an alliance with the Bolsheviks or Afghanistan. Meanwhile the Red Army continued defeating White forces in Transcaspia and in the Steppe and it became more prudent for Emir Muhammad Alim Khan to offer an olive branch to the Bolsheviks. However, the Bolsheviks made it clear that they would never find common cause with a country ruled by a bourgeois tyrant. Their propaganda made it clear that they considered Bukhara to be a bulwark of revolutionary and counterrevolutionary forces that the Kolesov campaign failed to crush. They encouraged the people of Bukhara to rise up and liberate themselves from British controlled enemies with Bolshevik help. They grew hopeful after the fall of Afghanistan cut Bukhara off from their British “supporters,” but it quickly became clear that the people would not revolt without Russian assistance.

The Young Bukharans Recover

While the Emir was navigating the tricky waters of the Russian Civil War, the Young Bukharans were struggling to survive their forced exile into Tashkent and other neighboring cities. At first, their number one priority was to avoid starvation and arguing with each other over the failed March coup. Some left politics, fled to Moscow, or joined the Communist organizations in Tashkent and Samarkand while reuniting and reconnecting with other Jadids. They tied their hopes for liberation of Bukhara with the Bolshevik cause, even though, as the Bolsheviks pointed out, many had land and wealth in Bukhara and thus greed and financial interest partially drove their concern. For their part, the Young Bukharans tried their best to tie their goals and message to Communism. A handful of Young Bukharans traveled to Moscow to represent the Bukharan state and argued that:

“only the Russian Socialist Revolution, the vanguard warrior with world imperialism, can liberate Bukhara from the slavery into which imperialists of all countries have led it, supporting Bukharan reaction in their own interests” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 121.

The Young Bukharans, encouraged by the Bolsheviks, argued that the Emir was a tyrant:

“All his thoughts are of living in luxury, and it is none of his business even if the poor and the peasants like us die of starvation. ‘His Highness’ is a man concerned only with eating the best pulov, wearing robes of the best brocade, drinking good wines, and having a good time with young- and good-looking boys and girls” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 122

However, the Young Bukharans ran into competition for Communist support when a group of Muslims living in the Russian enclaves of Bukhara organized the Bukharan Communist Party (BKP). The Bolsheviks in Tashkent were more sympathetic with the Bukharan Communist Party then they were with the Young Bukharans, and the BKP could use the Bolshevik language to heap complaints on the Young Bukharans. Meanwhile, the Young Bukharans considered the BKP to be interlopers who didn’t truly understand the needs of the Bukharan people. The Bolsheviks still needed the Young Bukharans for when they overthrew the Emir, so for the time being they tolerated them, but it was a painful and awkward relationship.

The Emir’s retaliation against the Young Bukharans/Bukharan Communists was swift and severe. He attacked anyone who had a western education and read western newspapers. The Emir government held tribunals and sentenced fifteen to twenty advocators for reform to death. Other, larger groups were killed without trial. Additionally, Bukhara’s economy was collapsing because the war prevented the re-establishment of the old economic relations with Russia or its neighbors. This led to higher taxation of the people leading to rioting and civilian anger. The Bolsheviks and the Young Bukharans saw it as a perfect opportunity to stoke that anger against the Emir. The Bolsheviks were doubtful about the Young Bukharan’s chances for success. One Bolshevik in Tashkent wrote that:

“The Decembrists of Asia, the Young Bukharans…have learnt nothing from history. They argued that the oppressed people of…Bukhara have to be “liberated’ from outside, with the force of the bayonets of the proletarian Red Army of Turkestan. That the ‘liberated’ exploited masses could, through their ignorance, see their liberators as foreign oppressors does not concern them.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 124.

Yet, Frunze planned to use the Young Bukharan’s rhetoric to justify his invasion of Bukhara.

The Fall of Bukhara

When Frunze arrived at Tashkent, he received reports that Emir Muhammad Alim Khan had raised an army of about 30,000 men with limited weapons and ammunition. Most of their officers were Ottoman and Austrian POWs, deserters from the British Indian Army, and anti-Russian officers and Cossacks. The Emir of Afghanistan sent support via two hundred troops and six elephants. After taking care of Junaid in Khiva, Bukhara was clearly the bigger threat.

Frunze’s army was spread across a territory of 2,000 kilometers and was involved in establishing a People’s Republic in the Steppe and Khiva, supporting the Turkkomissiia in Tashkent, and fighting the Basmachi in the Ferghana. He requested permission from Moscow to attack Bukhara and for reinforcements, but Moscow had no reinforcements to send. Frunze would have to rely on his own initiatives to justify and win an invasion.

Frunze did two things to prepare for his invasion. First, he increased his army by conscripting 25,000 Muslims and Indigenous peoples, organizing the units based on nationalities. Adding the 25,000 conscripts to his army of 6-7000 infantrymen, 2,300 cavalrymen, 35 light and 5 heavy guns, 8 armored cars, 5 armored trains, and 11 pieces of aircraft, he was confident he had enough men to win a fight with the Bukharan army. All statistics regarding the Bukharan invasion come from Robert F. Baumann’s book, Russian-Soviet Unconventional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Afghanistan. He was definitely better prepared than Kolesov was in 1918. His conscription solved his manpower issue, but temporarily exasperated his Basmachi problem by driving 30,000 men into the arms of the Basmachi, but that’s a problem for a different podcast episode.

Second, he united the Young Bukharans and the Bukharan Communist Party into one party to streamline communications and power sharing and then used their grievances with Emir Muhammad Alim Khan to invade the khanate.

Fires in Bukhara under siege by Red Army troops, 1 September 1920

[Image Description: A sepia tone picture of an aerial view of a burning city. One can made out the city streets and taller buildings. Heavy white smoke issues from the center right of the building.]

Frunze’s assault consisted of four surprise and simultaneous strikes conducted by four independent operational groups. The Jadids contributed by sparking uprisings within the khanate. The attack would start with the Chardzhul uprising.

Operational Group Two consisted of a rifle regiment and battalion, and two detachments of cavalry. Group Two advanced from the southwest to provide support to the Chardzhul uprising and take the city Kara-Kul and the neighboring railroad line. Cavalry elements would take several crossings along the Amu River and cut the railroad line that connected Old Bukhara to Termez.

Operational Group One consisted of the 4th Cavalry regiment, the 1stEastern Muslim regiment, an armored car detachment, and militia from several garrisons. Once the uprising in Chardzhul started, Group One advanced on old Bukhara from the city of Kagan in the north. Their goal was to destroy the emir’s main force and deny him any chance of escape.

Operational Group Three, which consisted of a cavalry regiment and detachment of conscripted Muslim soldiers attacked from the east, taking four neighboring cities on the way. Operational Group Four which consisted of a rifle regiment, two cavalry detachments, and engineer company, advanced from Samarkand.

Frunze relied on the Amu flotilla to patrol the Afghan border and blocking the emir’s escape route. His ground forces were supported by the 25th, 26th, and 43rdAviation Reconnaissance Detachments as well.

Group Two seized Chardzhul on the night of August 28th and Group One marched north to Old Bukhara while securing the Amu River. By the night of August 29th, Group One was sitting outside the gates of Old Bukhara. The city itself consisted of 130 defensive towers and eleven gates and it’s estimated that the city walls were roughly ten meters high and five meters thick.

Frunze launched an aerial bombardment of the city on August 31st and September 1stbut were unable to damage the defensive walls. He pulled up his 122-mm and 152-mm artillery pieces, but they were ineffective because of inexperienced officers. Russian infantry followed the bombardment, but they failed to take the city. After hearing of the failure, Frunze bemoaned:

“If the operation will be conducted this unskillfully the city will never be taken” - Robert F. Baumann, Russian-Soviet Unconventional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Afghanistan, pg 111

On September 2nd, 1920, the Red Army blew a breach in the inner fortress wall. They followed the breach up with aerial and artillery bombardment and then the infantry charged. Both forces engaged in street-to-street fighting as the Emir’s forces broke and fled. The Emir himself watched the battle from outside the city and escaped along with five hundred mounted fighters, when the battle turned. A Russian aviation unit spotted the emir and a cavalry unit chased after him, but he evaded their forces and reached his fortress at Dushanbe. From there he would flee to Afghanistan and remain there until he died in 1944.

With the fall of Bukhara, Frunze had cleared most of the Communist’s enemies from Turkestan. The only ones who remained were the Basmachi. Frunze worked with the Indigenous people to proclaim the Bukharan People’s Soviet Republic on October 8th, 1920, establishing the final people’s republic of Central Asia. It was now time to crush the Basmachi insurgency and establish a Communist form of government over the region.

Reference

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Central Asia: a History by Adeeb Khalid

Russian-Soviet Unconventional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Afghanistan by Robert F. Baumann,

Russia's Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva 1865-1924 by Seymour Becker

#queer historian#history blog#central asia#central asian history#queer podcaster#spotify#mikhail frunze#musburo#turar risqulov#turkestan#soviet union#russian colonialism#bukhara#khiva#fall of bukhara#full of khiva#Spotify

0 notes

Note

Colonialism is a disease

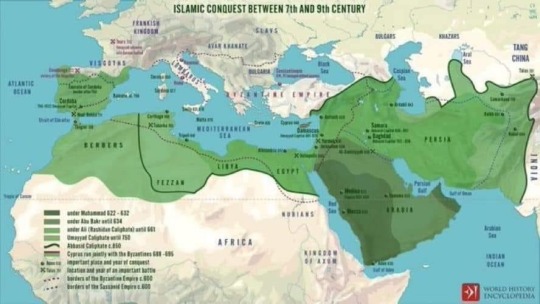

Imagine being an Arab Muslim and having the audacity to call someone else a colonizer. The illustration below is a snapshot of Islamic colonialism and occupation of other people's lands, from the 7th-9th centuries. Islam went on to attack, destroy, occupy and colonize vast swaths of Europe and southeast Asia, as well as what is now called Turkey.

The world has witnessed many colonial empires since the beginning of time. Most notably, the Mongols, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Babylonians, Egyptians, Islam/Ottomans, Portuguese, Dutch, French, Spanish, British, and American. The only empire that didn't take land, even after winning world wars, were the Americans. They actually gave back the Philippines. But I digress.

All of these empires were in large part, created by bloody conquest, and built on the backs of the newly subjugated. The Hebrews were, famously, slaves in Egypt. No one seems to teach this in the west, focusing more on the Romans, but of all the colonialists, one of the most deadly brutal and expansionist empires were the Muslims aka the Islamists. The Islamic empire expanded by sheer, from Medina (where Muhammad massacred and enslaved the 50% majority Jewish population) all the way into western North Africa, much of Europe, and large populations of Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, parts of India now called Pakistan, etc). As it expanded using violence and fear, Islam literally took 100 million slaves out of Africa, and was responsible for one of the greatest mass murders in history: killing 10 million (or more) on the forced march from their homelands to the Middle East.

Some examples of Islamic slavery include the Al-Andalus slave trade, the Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Comoros slave trade, the Zanzibar slave trade, the Red Sea slave trade, the Barbary slave trade, the Ottoman slave trade, the Black Sea slave trade, the Bukhara (Uzbekistan) slave trade, and the Khivan slave trade from which Islam took millions of slaves out of Persia to the Islamic khanates. There are Arab/Islamic societies today (Libya, a well-known example) that still trade slaves.

Compare this to Israel. Israel/Judea was never colonial nor expansionist. The Hebrews (aka Jews) were often properties of and were subjugated by, colonial empires, including the Islamic colonial empire.

They Hebrews themselves, as noted above, were most famously slaves of the the colonial Egyptian empire, some 4,000 years ago, before being murdered and subjugated by Islam starting in the 7th century. Somehow able to escape Egyptian tyranny through their own efforts (some say, by the grace of Hashem), the Hebrews settled in their current indigenous homeland 3.600 years ago - a small area by global standards, smaller than Belize, Albania, or Montenegro. They were happy there, and even at their peak, did not attempt to force convert others or expand much beyond their lands.

As historian Barbara Tuchman wrote, Israel is “the only nation in the world that is governing itself in the same territory, under the same name, and with the same religion and same language as it did 3,000 years ago.” Despite all the occupations and forced exiles, the Jews/Hebrews/Israelites have maintained a continuous presence in Judea/Israel/Samaria for some 3,600+ years. And even though Israel was granted modern statehood in 1948, it is one of the oldest continuously maintained countries in the world. The 'modern' state of Israel came to fruition post WWII, in 1948; the redefinition of borders and modern statehood after the fall of the big colonials was in no way unusual to Israel. Many country's modern borders came to be defined in the post colonial period (post WWI & WWII). While Israel and Lebanon and Iraq and Iran and Syria and Egypt were all ancient civilizations, dating back thousands of years, modern statehood came in the 20th century: For example, statehood was granted to Egypt in 1922; Saudi Arabia and Iraq in 1932; Lebanon in 1943; Indonesia, South Korea & Vietnam in 1945; Syria & Jordan in 1946; India & Pakistan in 1947; Israel, & Myanmar in 1948; Laos, Libya & Bhutan in 1951; Cambodia in 1953; Morocco, Sudan & Tunisia in 1956; Ghana & Malaysia in 1957; and so on.

The problem is, the tribalism and supremacy of Islam, can't stand that it's once-conquered land is now in the hands of the original owners. Islam believes that once it puts a flag in the sand somewhere, it's theirs.

Oh, and by the way, Andalusia (Spain) is next in Islam's sights.

#islam#colonialism#colonialist#colonizers#israel#secular-jew#jewish#judaism#israeli#jerusalem#diaspora#secular jew#secularjew#Islamic jihad#jihad#Hamas#taliban#Isis#Iran#gaza#Samaria#judea#samaria#judea and samaria#jihadis#hamas#hamas war#iran war#islamists

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tajikistan & Tajik Literature

Wall Of Tajik Writers

Tajikistan is a landlocked country in central Asia, bordered by Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, China, and Kyrgyzstan. It is the official home of the Tajiks, an Iranian ethnic group. Tajikistan was home to many well-known early civilizations including the ancient city of Sarazm, the Oxus civilization, Andronovo culture, and many others. The area was ruled by several dynasties including the ancient Achaemenid Empire and the subsequent Sasanian empire. This area experienced the rise and fall of many empires including the soviet empire in 1929. Within the years of the soviet occupation, Tajikistan was home to a literary explosion. The Tajik literary centers include Bukhara and Samarkand in what is now Uzbekistan where there is a large Tajik population. The literature that has survived from Tajikistan and other large Tajik populations is predominantly Socialist Realism, a genre expressed largely by writer, communist, and educator Sadriddin Aini. His work also includes novels and memoirs. Another writer is Abu’l Qasem Lahuti, who wrote “socialist realist” verse and lyrical poetry. Another writer is Mirzo Tursunzoda, he collected Tajik Oral Literature and wrote extensively on social change in Tajikistan. Tajikistan has a rich and varied body of poets, novelists, and intellectuals that were inspired by these writers.

-عبد المسیح

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

**The History of the Silk Road**

The Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes, played a crucial role in connecting the East and West for centuries. Spanning over 4,000 miles, it facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also the flow of culture, ideas, and technology between civilizations.

### Origins and Early Development

The origins of the Silk Road can be traced back to the Han Dynasty in China (206 BCE – 220 CE). The Chinese emperor Han Wudi sent an envoy, Zhang Qian, to explore lands to the west, seeking alliances and trade opportunities. This mission laid the groundwork for what would become the Silk Road. The route was named after the lucrative silk trade that was central to its commerce. Chinese silk was highly prized in the West, and its trade marked the beginning of extensive interactions between distant cultures.

### Expansion and Major Routes

The Silk Road was not a single path but a network of interconnected routes. It extended from the ancient Chinese capital of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an) through Central Asia, reaching as far as the Mediterranean. Key cities along the route included Samarkand, Bukhara, and Kashgar, which became bustling centers of trade and cultural exchange.

Merchants traveled with caravans, carrying goods such as silk, spices, precious metals, and gemstones. In return, they brought back wool, gold, silver, and glassware from the West. The exchange was not limited to tangible goods; it also included ideas, religions, and technologies. Buddhism, for instance, spread from India to China along the Silk Road, profoundly influencing Chinese culture and spirituality.

### Cultural and Technological Exchange

The Silk Road was a melting pot of cultures. It facilitated the spread of art, literature, and scientific knowledge. Chinese inventions like paper and gunpowder made their way to the West, while Western astronomical knowledge and medical practices traveled eastward. The route also saw the exchange of artistic styles, as evidenced by the blend of Greek, Persian, and Indian influences in the art and architecture found along the Silk Road.

One of the most significant impacts of the Silk Road was the spread of religions. Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and later Islam, all traveled along these routes, leaving a lasting legacy on the regions they touched. Monasteries and temples sprang up along the way, serving as places of worship and rest for travelers.

### Decline and Legacy

The decline of the Silk Road began in the 15th century with the rise of maritime trade routes. The discovery of sea routes to Asia by European explorers like Vasco da Gama reduced the reliance on overland trade. Additionally, the fall of the Mongol Empire, which had provided stability and security for the Silk Road, contributed to its decline.

Despite its decline, the legacy of the Silk Road endures. It laid the foundation for globalization by fostering connections between diverse cultures. The exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies along the Silk Road had a profound impact on the development of civilizations across Eurasia.

### Modern Revival

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in the Silk Road. China's Belt and Road Initiative aims to revive and expand the ancient trade routes, promoting economic cooperation and cultural exchange across Asia, Europe, and Africa. This modern Silk Road seeks to build on the historical legacy of the ancient routes, fostering a new era of connectivity and collaboration.

*Copyright Bradley Lawrence 2020-2024*

0 notes

Text

Events 8.16 (after 1920)

1920 – Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Indians is hit on the head by a fastball thrown by Carl Mays of the New York Yankees. Next day, Chapman will become the second player to die from injuries sustained in a Major League Baseball game. 1920 – The congress of the Communist Party of Bukhara opens. The congress would call for armed revolution. 1920 – Polish–Soviet War: The Battle of Radzymin concludes; the Soviet Red Army is forced to turn away from Warsaw. 1923 – The United Kingdom gives the name "Ross Dependency" to part of its claimed Antarctic territory and makes the Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand its administrator. 1927 – The Dole Air Race begins from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii, during which six out of the eight participating planes crash or disappear. 1929 – The 1929 Palestine riots break out in Mandatory Palestine between Palestinian Arabs and Jews and continue until the end of the month. In total, 133 Jews and 116 Arabs are killed. 1930 – The first color sound cartoon, Fiddlesticks, is released by Ub Iwerks. 1930 – The first British Empire Games are opened in Hamilton, Ontario, by the Governor General of Canada, the Viscount Willingdon. 1933 – Christie Pits riot takes place in Toronto, Ontario. 1942 – World War II: US Navy L-class blimp L-8 drifts in from the Pacific and eventually crashes in Daly City, California. The two-man crew cannot be found. 1944 – First flight of a jet with forward-swept wings, the Junkers Ju 287. 1945 – The National Representatives' Congress, the precursor of the current National Assembly of Vietnam, convenes in Sơn Dương. 1946 – Mass riots in Kolkata begin; more than 4,000 people would be killed in 72 hours. 1946 – The All Hyderabad Trade Union Congress is founded in Secunderabad. 1954 – The first issue of Sports Illustrated is published. 1960 – Cyprus gains its independence from the United Kingdom. 1960 – Joseph Kittinger parachutes from a balloon over New Mexico, United States, at 102,800 feet (31,300 m), setting three records that held until 2012: High-altitude jump, free fall, and highest speed by a human without an aircraft. 1964 – Vietnam War: A coup d'état replaces Dương Văn Minh with General Nguyễn Khánh as President of South Vietnam. A new constitution is established with aid from the U.S. Embassy. 1966 – Vietnam War: The House Un-American Activities Committee begins investigations of Americans who have aided the Viet Cong. The committee intends to introduce legislation making these activities illegal. Anti-war demonstrators disrupt the meeting and 50 people are arrested. 1972 – In an unsuccessful coup d'état attempt, the Royal Moroccan Air Force fires upon Hassan II of Morocco's plane while he is traveling back to Rabat. 1975 – Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam symbolically hands over land to the Gurindji people after the eight-year Wave Hill walk-off, a landmark event in the history of Indigenous land rights in Australia, commemorated in a 1991 song by Paul Kelly and an annual celebration. 1987 – Northwest Airlines Flight 255, a McDonnell Douglas MD-82, crashes after takeoff in Detroit, Michigan, killing 154 of the 155 on board, plus two people on the ground. 1989 – A solar particle event affects computers at the Toronto Stock Exchange, forcing a halt to trading. 1991 – Indian Airlines Flight 257, a Boeing 737-200, crashes during approach to Imphal Airport, killing all 69 people on board. 2005 – West Caribbean Airways Flight 708, a McDonnell Douglas MD-82, crashes in Machiques, Venezuela, killing all 160 people on board. 2008 – The Trump International Hotel and Tower in Chicago is topped off at 1,389 feet (423 m), at the time becoming the world's highest residence above ground-level. 2013 – The ferry St. Thomas Aquinas collides with a cargo ship and sinks at Cebu, Philippines, killing 61 people with 59 others missing. 2020 – The August Complex fire in California burns more than one million acres of land.

0 notes

Photo

the queens of queens

Versailles Palace of Rego Park, Queens ... the hub of Bukharian culture, a small but resilient community of Mizrahi Jews who immigrated to deep Queens after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Bukharians aren’t Russian. They come from the ancient city of Bukhara in Uzbekistan, a predominantly Muslim country. (There were also large Bukharian communities in the Uzbekistan cities of Samarkand and Tashkent.) In addition to speaking Russian, they have their own language, Bukhari, a Judeo-Tajik dialect of Tajik and Persian with some Hebrew.

These ladies are dressed to impress in ornate, perfectly tailored dresses, some of which are body skimming, while others—depending on the person—are more conservative. And then there’s the jewelry: an encrusted bracelet, a flashy watch, and killer earrings. No hair is out of place; no nail is left unlacquered. The heels are stacked and polished to a high shine.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of Today in World War I

November 11 2021, Arlington--Three years beyond the armistice seems a good enough place to finally bring my coverage of the post-war events to a close. There are still plenty of loose (or, honestly, dropped) threads left over from the war that would continue more than three years past the armistice, and I would feel remiss if I just stopped here without providing at least some conclusion.

Russia:

The defeat of Wrangel in November 1920 ended the last major White threat to Soviet power in Russia, though localized threats on the periphery would continue for at least two more years. Makhno’s Black Army of anarchists in Ukraine, after a brief alliance with the Reds against Wrangel, were forced into exile by August 1921. The last Armenian resistance in the mountains southeast of Yerevan was crushed in July 1921. Georgia saw continued small-scale guerilla fighting and a large rebellion in August 1924, though this failed to take Tblisi and was swiftly crushed.

The Soviets had thought they had largely secured control over Russia’s former holdings in Central Asia with the fall of Bukhara in September 1920. However, guerilla resistance by the Basmachi movement continued. In November 1921, former Ottoman leader Enver Pasha arrived to assist the Soviets, but soon defected to the Basmachi in a misguided continuation of his wartime plans for a grand pan-Turkish state. Enver reinvigorated the Basmachis and they seized large portions of present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Soviets, in return, made political concessions to the Muslims in the area while simultaneously bringing the full might of the Red Army to bear. After suffering multiple defeats, Enver Pasha was killed in a foolhardy cavalry charge on August 4, 1922. Local Basmachi resistance would continue for another year or two, and occasional cross-border raids from Afghanistan for a decade after that.

In the Far East, Japanese withdrawal towards Vladivostok allowed the Soviets to secure the crucial rail junction of Chita in October 1920. Most of the remnants of Kolchak’s forces fell back with them (or left the country entirely), but General Ungern-Sternberg decided instead to invade Mongolia in an insane plan to restore the Mongolian Empire. In February 1921, he captured Ulaanbaatar from the Chinese and returned Bogd Khan to power, but he was ousted by the Soviets and Red Mongolian forces in July, and was captured and executed later in the summer. The Mongolian People’s Republic was established (with Bogd Khan kept as head of state until his death in 1924) and would remain until the end of the Cold War.

A brief White offensive took Khabarovsk, 500 miles north of in the winter of 1922, but they were repulsed by February. Vladivostok only fell to the Reds after the Japanese evacuated in October 1922. Some White resistance remained around Okhotsk until June 1923, and the Japanese did not fully withdraw from Kamchatka and northern Sakhalin until 1925.

On December 28 1922, with the Civil War all but over, the Soviet Union was officially created by the agreement of the Soviet governments in Russia, Ukraine, Byelorussia, and Transcaucasia.

North Africa:

Despite his great victory at Annual, Abd el-Krim was not able to push onto Melilla and eject the Spanish from the eastern Rif. A stalemate ensued, and a large faction in Spanish politics preferred abandoning Morocco entirely. In September 1923, General Primo de Rivera seized power in a coup and planned to pull back from Morocco, but under coup threats from junior officers, instead fortified the remaining Spanish positions. In 1925, Abd el-Krim’s forces invaded French Morocco, reaching as far as Fez. The French responded with overwhelming force with a large army under Pétain, along with aircraft, artillery, and chemical weapons, and Abd el-Krim surrendered in May 1926.

Egypt had nominally been an Ottoman possession (albeit under British administration) until the outbreak of World War I, and the end of the war saw increased demands for Egyptian sovereignty, leading to mass strikes and protests in the spring of 1919. These were crushed by the British, and the following negotiations with moderate Egyptian nationalists were inconclusive. Lloyd George wanted to maintain the protectorate, but in early February 1922 General Allenby, now British High Commissioner in Egypt, threatened to resign. On February 28 1922, the United Kingdom unilaterally declared the independence of the Kingdom of Egypt, but reserved power over Egypt’s defense, minority rights, “the protection of foreign interests in Egypt,” and Sudan. These reserve clauses would remain in effect until Nasser seized power thirty years later.

Turkey and Greece:

In the summer of 1921, the Greeks launched a major new offensive towards Ankara, hoping to decisively defeat Kemal’s Turkish nationalist government. However, the Greeks were largely alone in this effort; the French, Italians, and Soviets had all warmed to Kemal and conducted arms trades with (or, in the case of Soviets, gifted arms to) Turkey. The British were still friendly to the Greeks, but less so after Venizelos’ election defeat and King Constantine’s restoration to the throne. After fierce battles in August and September 1921 25 miles from Ankara, the overextended Greek forces were halted and forced to fall back. In October, the French signed a treaty with Kemal’s government, largely settling the modern-day border between Syria and Turkey (excepting the area around Alexandretta [İskenderun], which remained under French control until 1937 before joining Turkey after a disputed referendum in 1939).

The Allies, realizing that the Treaty of Sèvres was dead, were willing to renegotiate, but Kemal, having the upper hand militarily in Anatolia, refused. On August 26 1922, Kemal broke through the still-overextended Greek lines and pushed towards Smyrna [İzmir], reaching the city on September 9. A fire engulfed the Greek and Armenian parts of city in the following days. Over 150,000 refugees were evacuated to Greece, while tens of thousands more perished in the fire or were deported to the Anatolian interior. The stunning defeat led a revolution in Greece by the end of the month, returning pro-Venizelos forces to power and forcing King Constantine to abdicate for a second time, this time in favor of his first son, George; Constantine would die in exile a few months later.

With Smyrna secured, Kemal soon moved on towards the Straits and Constantinople. Lloyd George, Churchill, and a small number of Conservatives in the coalition government called for defending the Straits against Kemal, even if it meant war with Turkey. However, the other Conservatives, along with, in a notable change from 1914, Canadian PM Mackenzie King, were opposed to war. On October 11, the Allies agreed to an armistice with Kemal at Mudanya, in which the Greeks agreed to evacuate what is now European Turkey up to the Maritsa river. The wartime coalition in Britain broke apart, and Conservative Bonar Law became Prime Minister later in the month before winning an overall majority in elections the next month (which saw the Liberals, still split between Lloyd George and Asquith, relegated to third-party status behind Labour).

On November 1, the Turkish General Assembly dissolved the Ottoman Empire. Final peace negotiations for a treaty to replace Sèvres dragged on for months, but a treaty was finally signed in Lausanne on July 24 1923. Kemal’s government in Turkey was recognized by the Allies, with essentially its modern borders. The fate of Mosul was to be left to the League of Nations, which eventually decided in favor of Iraq in 1926. Civilian ships were allowed free passage through the Straits, and Turkey’s European border was to be demilitarized (on both sides). Related agreements between Turkey and Greece resulted in large-scale population transfers, with over 1.5 million Greeks from Turkey moved to Greece and 500,000 Muslims in Greece moved to Turkey. This did not apply to the Greek population in Constantinople (and a few Turkish islands), whose rights were recognized explicitly in the Lausanne treaty.

The Allies finally left Constantinople on October 4 1923, and Turkish forces entered the city two days later.

All efforts to prosecute those responsible for the Armenian genocide ended with Lausanne, though by this point the Armenian assassination campaign had killed many of the top leaders, culminating with the killing of Djemal Pasha in Tblisi in July 1922.

The Middle East:

Britain’s Hashemite allies, ejected from Syria by the French in July 1920, were given, effectively, consolation prizes in Britain’s new mandates in the Middle East. Feisal was made King of Iraq in August 1921 (after the British had suppressed revolts there the previous year), and his elder brother Abdullah Emir of Transjordan in April 1921. Their father, Hussein, remained in power in the Hejaz, and even declared himself Caliph after Turkey dissolved the Caliphate in 1924. However, his relations with the British deteriorated, as Hussein repeatedly refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. With British support, the Saudi rulers of Nejd invaded Hejaz, taking Mecca without resistance in October 1924 and Medina and Jeddah fell in December 1925 and January 1926. The Saudis soon established a protectorate over Asir (home of the Idrisids, who had by this point been ejected from Yemen by Imam Yahyah), though fighting in the area would continue until the early 1930s, when the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was officially declared and Yemen signed peace treaties with the Saudis and the British.

Japan and China:

The day after the burial of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington, an international conference on arms limitation convened in Washington. After extensive negotiations (in which the Americans were aided by cryptologic successes against the Japanese), the UK, the US, and Japan agreed to a 5:5:3 ratio in battleships, and a limit in tonnage for battleships (both for individual ships and overall); France and Italy were limited to a 1.67 ratio. This averted an expensive naval arms buildup that some blamed for the buildup of tensions before the First World War. Japan agreed to give up its concession in Shandong (around Tsingtao), a huge win for China and the United States, though they remained economically dominant in the area. The United States recognized Japan’s claim to the island of Yap, and the Anglo-Japanese alliance dating from 1902 was officially dissolved. Further construction of fortifications in the western Pacific was forbidden.

The treaty had a mixed reaction in Japan; although the 5:3 ratio was much more favorable to Japan than the equivalent ratio of Japanese and US economic bases, it was still viewed as a snub in ultraconservative circles.

Eastern Europe:

A portion of western Hungary, including the city of Sopron, had been assigned to Austria by the Treaty of Trianon, and was due to be transferred in August 1921. However, elements of the local Hungarian population in Sopron resisted Austrian entry, and organized a plebiscite in December in which Sopron’s population voted by a 2-1 margin to remain in Hungary. This was ultimately recognized by the Allies, though the rest of the territory was transferred to Austria as planned.

On October 21 1921, the former Emperor Charles flew into Hungary in a monoplane, formed a provisional government in Sopron, and prepared to march on Budapest. Horthy, who was ostensibly serving as Charles’ regent, quickly organized a resistance and soon outnumbered Charles’ forces, as Hungary’s neighbors prepared for yet another invasion of the country. On November 1, Charles left for exile in Madeira, and within days parliament officially dethroned the Habsburgs (although Horthy remained as regent). Charles died of pneumonia in April 1922. His nine-year-old son, Otto, became the head of the Habsburgs in exile, and would remain so until his death in 2011.

Poland’s puppet Republic of Central Lithuania, based in Vilnius, held elections (boycotted by most of the non-Polish population) in January 1922; the resulting government asked to be annexed by Poland, which was granted in March. Lithuania refused to recognize this, and still claimed Vilnius as its capital. The Allies attempted to defuse the situation by offering the Lithuanians French-occupied Memel [Klaipėda] in exchange for recognizing Polish control of Vilnius. The Lithuanians refused, and the Allies prepared to make Memel a free port like Danzig. Instead, the Lithuanians staged a revolt in Memel (like the one the Poles had staged in Vilnius) in January 1923 and soon seized control of the city. The Allies protested, but acknowledged the Lithuanian presence as a fait accompli.

Ireland

On December 6 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed. Within a year, Ireland was to become the Irish Free State, a British Dominion in the same vein as Canada. Northern Ireland would have the option to withdaw (which it quickly exercised). King George V would remain as head of state, and members of the Dáil would have to swear an oath of loyalty to him. Britain would retain control of Berehaven, Queenstown [Cobh], and Lough Swilly, which would become known as the Treaty Ports. Ireland would assume an appropriate portion of the United Kingdom’s debt.

The Treaty provided for Irish independence, of a sort, but there was substantial opposition to the Treaty, lead by Eámon de Valera, who demanded nothing short of a fully republican Ireland. In April, anti-Treaty forces seized the Four Courts in Dublin. In June, the pro-Treaty forces won a convincing majority in the first Free State election. Four days later, Field Marshal Henry Wilson (formerly Chief of the Imperial General Staff), who was now a MP from Northern Ireland, was assassinated by the IRA in London. The British threatened to attack the Four Courts in response, but the Free State government (led by Michael Collins) pre-empted this by attacking the building themselves. After a week of fighting, the pro-Treaty forces were victorious; among the dead was anti-Treaty leader Cathal Brugha.

Although the Free State was securely in control of Dublin, a civil war broke out in the rest of the country, with anti-Treaty forces concentrated in the south and west. With British support, the Free State was able to defeat most of the anti-Treaty forces by the end of 1922, although Michael Collins himself was killed in an ambush in August. Guerilla fighting continued until a ceasefire in May 1923. De Valera ultimately took the oath and re-entered Free State politics in 1927.

Italy

The postwar period saw increased labor unrest and socialist activity. Mussolini’s Fascists took advantage of disappointment around Italian gains in the war and anti-socialist sentiment to first win seats in parliament in 1921, while his Blackshirts actively helped suppress strikes. In October 1922, he became aware that D’Annunzio was planning a demonstration to mark the 4th anniversary of the victory over Austria-Hungary on November 4, and decided to pre-empt it by organizing a march on Rome from Naples (although he himself drove). The King refused to take action against Mussolini, and instead made him Prime Minister.

Germany

The Germans signed the Treaty of Rapallo in April 1922 with the Soviets, normalizing their relations and beginning trade between the two countries. It also began secret military cooperation between the two countries, explicitly violating the Treaty of Versailles. Two months later, industrialist Walther Rathenau, who as Foreign Minster had arranged the treaty, was assassinated by the same offshoot of the Ehrhardt Brigade that had assassinated Erzberger the previous year.

On January 11 1923, in response to German defaulting on reparations payments in the midst of a hyperinflation crisis, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr, despite opposition from the United Kingdom and the United States. On January 24 1923, the last American troops left the Rhineland. In August 1924, the Dawes Plan (drawn up by an American member of the Reparations Commission) was agreed to; it reduced reparations payments, offered American loans to Germany, and arranged for the French departure from the Ruhr within a year.

The occupation increased support for the far right in Germany. Taking inspiration from Mussolini’s success in Italy, Ludendorff and Hitler attempted their own version in Munich, the Beer Hall Putsch in October 1923, which failed within a day. After the ensuing trials, Ludendorff was acquitted, and Hitler ultimately only served one year in prison.

Hindenburg was elected President of Germany in 1925; Ludendorff, with whom he was once joined at the hip, was eliminated in the first round with barely 1% of the vote as the Nazi candidate.

In 1930, after the start of the Great Depression, German reparations were reduced yet again by the Young Plan, with additional financial backing provided by American banks. With German reparations payments apparently secure, the French withdrew from the Rhineland on June 30, 1930.

This post is already incredibly long, so I’ll spin the second half into a new post.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

whumptober2021, day 24: revenge

.

.

He sits on a fallen stone after it is all over, holds his musket across his knees and breathes in the dusty stale air.

What a mess, Kazakh thinks, surveying the ruins of the city, destroyed after the siege. The soldiers sit in circles on the dusty ground, sharing rolled cigarettes and warming their hands in their pockets, watching the vultures fly in circles above their heads.

He tries to ignore the smell of the dead outside the crumbled city walls; tries to remember what this place was before, the fertile flatlands around the Aral Sea, the plains of Transoxiana, the mountain ranges to the east, the oasis of fresh water where he and Mongolia used to let their horses rest after a long ride.

Russia approaches him slowly looking down, his uniform turned dusty yellow and his hands blackened with gunpowder.

“You can have all of this after we’re done,” he tells him as he sits on the rock next to his, his shoulders hunched over and body weary.

Kazakh observes as he pulls out a frail piece of paper and tobacco, rolls himself a cigarette.

“What if I don’t want it?” he asks, and Russia shrugs, pinches his cigarette between his thumb and forefinger, uses the other three to protect the small flame against the wind.

“Then we’ll divide it up among the others,” he says, smoking and looking away. “Can’t let it fall into his hands.”

He looks at the dirt between his boots, at the musket on his lap. He misses being on a horse, the taste of mare milk after a long day, the comfort of a straw bed. Things had changed after Russia lost at Crimea. He looks at his hunched shoulders and his blackened hands, his bloodshot eyes turned firmly away from him.

“Whose hands?” he asks, “The Ottoman’s? England’s?”

Russia smokes and doesn’t turn to face him. Kazakh watches the hand he has over his knee, the black gunpowder smudges it leaves on the fabric of his pants.

“Haven’t you taken enough territories?”

“I’ll decide when it’s enough.”

He sighs and looks up, at the birds circling above them, waiting for them to die to come peck at their warm flesh. Kazakh closes his eyes and breathes the smell of the steppes, hidden under the decaying scent of the dead.

“You’re tired of this, aren’t you?” he asks quietly, and the fingers Russia has over his knee tighten. Kazakh sighs, “You used to be such a quiet kid. Whittling wood by the fire.”

Russia flicks his cigarette away, stands up with his eyes still hidden.

“We march south tomorrow morning. Be ready.”

Kazakh watches the tension on his back as he walks away, looks down at the dust beneath his boots, tries to ignore the stench of war in the air.

-

Notes:

After losing the Crimea War (1853-56) against the allied coalition of French, British and Ottoman forces, the Russian Empire, who had already been expanding into Central Asia, having taken control of the Kazakh Steppe, intensified these efforts in an attempt to restore national pride (and which would later put them in direct confrontation against the British over control of Afghanistan in what is called The Great Game). In 1868 they conquered the Emirate of Bukhara, which encompasses present-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

However, anti-war sentiment in Russia strengthened after the Crimea War, calling for the end of serfdom (1861) and reforms in all political spheres, which would lay the groundwork for revolutionary ideas.

Vasily Vereshchagin covered the wars in Central Asia as a war painter, and in 1871 he dedicated one of his pieces, The Apotheosis of War, “to all conquerors, past, present and to come”.

#whumptober2021#no.24#revenge#hetalia#fic#war#discussion of war crimes#hws russia#hws oc kazakhstan#a wild fic appears#hws kazakhstan

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the fall of 1966, USSR used nuclear explosive for the first time to control a well that had been burning for three years in Uzbekistan.

In December 1963, while drilling gas Well No. 11 in the Urta-Bulak gas field in Southern Uzbekistan about 80 km southeast of Bukhara, control of the well was lost at a depth of 2450 m. This resulted in the loss of more than 12 million m3 of gas per day through an 8-inch casing, enough gas to supply the needs of a large city.

Formation pressures were about 270-300 atmospheres. Over the next three years, many attempts were made using a variety of techniques to cap the well at the surface or to reduce the flow and extinguish the flames.

Finally, in the fall of 1966, a decision was made to attempt closing the well with the use of a nuclear explosive. It was believed that a nuclear explosion would squeeze close any hole located within 25-50 m of the explosion, depending on the yield.

Two 13 1/2 inches deviated wells were drilled simultaneously. They were aimed to come as close as possible to Hole No. 11 at a depth of about 1,500 m in a 200 meter-thick clay zone. This depth was considered sufficient to contain the 300-atmosphere pressure in the gas formation below.

The location for the explosive in the selected relief well was cooled to bring it down to a temperature the explosive could withstand.

A special 30-kt nuclear explosive developed by the Arzamas nuclear weapons laboratory for this event was ran in hole and stemmed. It was detonated on September 30, 1966.

Twenty-three seconds later the flame went out, and the well was sealed. A few months after the closure of the Urtabulak No. 11 hole, control was lost on another high-pressure well in a similar nearby field, the Pamuk gas field.

This time, a special explosive developed by the Chelyabinsk nuclear weapons laboratory was used.

It had been designed and tested to withstand the high pressures and temperatures in excess of 100°C expected in the emplacement hole. It also was designed to be only 24 cm in diameter and about 3 m long to facilitate its use in conventional gas and oil field holes.

The second success gave Soviet scientists great confidence in the use of this new technique for rapidly and effectively controlling gas and oil wells. In April 1972 a 14-kt nuclear bomb was detonated to seal a gas well in the Mayskii gas field about 30 km southeast of the city of Mary in Turkmenistan.

In July 1972, another runaway gas well in eastern Ukraine, 65 km southwest of Kharkiv, was sealed with a nuclear explosion.

The last attempt to use this application occurred in 1981 on a well in the Kumzhinskiy gas deposit in the northern coast of Western Siberia near the mouth of the Pechora River, 50 km north of the city of Nar’yan Mar.

Reports indicated that due to the wrong position of the relief well, the explosion failed to seal the blowout.

Of the Soviet attempts to extinguish runaway gas wells, the Ministry for Atomic Energy of Russia reports that all the explosions were completely contained, and no radioactivity above background levels was detected at the surface of the ground during post-shot surveys.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Margarita Legasova’ book “Academician Valery Alekseevich Legasov”

Travelling around the country

In one of the TV programs, someone imprudently called academician Valery Legasov a religious person. It’s not true.

Reflections on the meaning of intelligent life and on life in general, its origins, the tragedy of existence and death has always been a profound source of inspiration for creative people. Since the fall of 1987, Valery Alekseevich re-read the Bible. He was not baptized and did not give preference to any of the religions. In a primitive sense, he wasn’t a believer, did not fetishize religious rituals, symbols. On the other hand, to all the outward appearances of religiosity he showed great respect. He was never engaged in antithesis, although the environment brought him up as an atheist. In high, philosophical sense, he was interested in the ideas of the Cosmos.

Everything related to religion for him, a materialist scientist, has been a kind of historical and cultural heritage. Religious buildings, as well as other material values passing from one generation to another, in his perception only emphasized their spiritual continuity. One can say that he was curious about this aspect of human existence. For any manifestation of a high human spirit, Valery Alekseevich felt the deepest respect, bordering on admiration. He had a particular weakness for the East. During official trips to Bukhara, Samarkand, and Turkestan, he always visited historical and architectural monuments and mosques.

After the May holidays in 1983, Valery offered me to accompany him to Alma-Ata: from May 11 to May 13, there was a meeting of the Bureau Of the Commission on hydrogen energy of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. After the end of the evening session, we were happy to see the exhibits of the archaeological Museum. Many things attracted our attention – samples of ceramics, pieces made of bronze, bone, stone, wood, jewelry made of iron, silver, bronze with chalcedony and carnelian, agates and turquoise, gold jewelry from the Issyk mound. In this Museum we first heard about the grave of Saint Khodj Ahmed Yassavi in Turkestan (formerly the city of Yasi). It is 900 kilometers from Alma-Ata, near Chimkent.

What we learned had sunk into our hearts, and in autumn, at the beginning of September, Valery invited me to accompany him to Chimkent for the scientific conference "Khimreaktor-9".

Three and a half hours after departure from Moscow, the plane landed in Chimkent, from where a little later we left for Turkestan.

The ancient city of Yasi was once destroyed by the troops of Genghis Khan. In 1934, having finally defeated the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh, Emir Timur indicated the place where the future Shrine of Islam – the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yassavi - was to be built.

This monument was built in honor of the ancient Turkic poet and Sufi preacher Ahmed Yassavi who lived in the XII century. The collection of his edifying poems "Hikmet", which means "wisdom", is widely known. We bowed to the jade tombstone.

Perhaps a close acquaintance with the history of religions, the spiritual heritage of our great predecessors on Earth strengthened Valery Alekseevich in the idea that any evil is punishable.

On October 29, 1986, my husband returned from Chernobyl once again, and on October 30 we flew to Dushanbe: Valery Alekseevich accepted an invitation to participate in the 21st Avicenna reading, to give a lecture "Chemical aspects of scientific and technological progress." On this trip, we were looked after by the president of the Academy of Sciences of the Tajik SSR, a philosopher, an interesting person, Muhammad Sayfitdinovich Asimov.

I remember that on this trip there were many excursions around the city and its surroundings. We visited all the monuments, honored the memory of Avicenna, visited the graves of ballerina Malika Sabirova, literary figures F. Mukhammadiev and Tursun-Zade. We visited the repository of ancient manuscripts. We saw the windswept Varzob gorge, the mighty Hissar ridges. The atmosphere of the whole trip was highly intellectual.

In my heart, I am grateful to all those who are more or less were involved in organizing excursions in the short hours that Valery Alekseevich could devote to rest - in Azebrajjan, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, the far East and other places.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Creation of the Central Asian Soviet Republics

During the last few episodes, we’ve discussed the Russian Revolution, the fall of the emirs, the Basmachi insurgency, the destruction of the Kokand Autonomy and the neutering of the Musburo. Unsurprisingly, all of this upheaval was horrible for everyone in the region and made governing almost impossible. Frunze, who was responsible for a lot of the upheaval, left in the fall of 1920, and did not see the outcomes of his explosive decisions.

Instead, it was up to the Communist officials and the Indigenous actors to create a new Central Asia. Unfortunately, they could not agree on the methods they should use, the ideological foundations of their new creation, or even what that new creation would look like. They didn’t trust each other; the Bolsheviks believed the indigenous actors weren’t proper Communists and the indigenous actors were annoyed that the Bolsheviks thought they knew best and purposely ignored all of their proposed solutions.

Things were worse for the people of the region. The Jadids were never popular even before the wars and this distrust grew as they sided with the Bolsheviks and tried to create a new world for the region. And so, as a farmer or merchant or just regular person in Central Asia, you had three choices: side with the Basmachi and risk death or losing everything to their raiding bands, side with the Jadids and Bolsheviks and support something that seems incompatible with one’s culture and religion, or try to survive on your own and at the mercy of all different factions and sides.

The core struggle can be best described by this quote from Lenin.

[Image Description: A colored gif of three men sitting together in a bowling alley. Two men are facing the camera and the third man is between the two men with his back to the camera. The man on the left has long hair and a long, scraggy beard. He is wearing a green shirt with a beeper hanging from the color. The man on the right is a bigger white man with short hair and beard and mustache. He is wearing light brown sunglasses and a short sleeve purple stripped shirt. The man in the middle has shoulder length hair and is wearing a green t-shirt. The bowling alley is pink and has blue star decorations on the walls.]

In 1921, he wrote:

“It is devilishly important to conquer the trust of the natives; to conquer it three or four times to show that we are not imperialists, that we will not tolerate deviations in that direction” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, 165

Not sure if Lenin even noticed the stark contradiction between “conquering” someone’s trust and somehow proving you’re not an imperialist or conqueror. Maybe he meant well, but we’re already off to a rocky start.

Communist Paranoia

A big source of tension between the Bolsheviks and the indigenous actors of Central Asia was the difference in ideology and goals.

We’ve talked a lot about the Jadid’s ideology and their goals. The Jadids in Bukhara and Turkestan wanted to create a modern state built around the principles of nationalism. They wanted to create a state that enjoyed full sovereignty and membership amongst the world of nation-states. They wanted to develop their own economy but maintaining control over their own resources and they wanted to education their citizens to combat “ignorance” and “fanaticism.” They wanted to preserve Islam, but also modernize it by bringing Muslim institutions under control of the government.

The Communists, however, wanted to create a perfect Communist society which required loyal and ideologically pure cadre. The only way they could do this in Central Asia was to recruit the population into the party. They knew their best demographic were the youth, the women, and the landless and poor peasants. The children they recruited into their youth group known as Komsomol and the brought the women’s organization, Zhenotdel to Central Asia. They also created the Plowman union for the poor. They would use this union to implement the land and water reform of the 1927, but were disbanded after serving their purpose.