#example of expository text

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Poet and the Historian (Homer and Herodotus)

"POET AND HISTORIAN: THE IMPACT OF HOMER IN HERODOTUS’ HISTORIES*

Christopher J. Tuplin

This volume is devoted to the relationship between Herodotus and Homer. Since it is obvious that Herodotus refers to Homer and selfevidently reasonable to feel that the entire Herodotean enterprise has a Homeric quality, it is not easy to address the topic without fairly rapidly starting to engage in quite detailed commentary on Herodotus’ text, and this is exemplified by the other essays that appear in the present publication. The essays by Barker and Donelli offer new implicit intertextual connections between Homer and Herodotus, while that by Fragoulaki comments on an absent intertext or an intertext that consists in absence. Tribulato deals with what turns out to be the elusive issue of the version of Ionian dialect found in (the manuscripts of) Homer and Herodotus—a different sort of implicit intertextual relationship between the two writers. Harrison considers Herodotus’ remarks on the role of Homer (and Hesiod) in creating the familiar image of Greek gods, while Haywood examines the wider category of which those remarks are an example (i.e., explicit Herodotean allusions to Homer). All of these essays have methodological elements, of course, but only that by Pelling comes close to making methodological comment a central focus. And yet it would perhaps be misleading to characterise it too strongly in such epistemologically heavy terms. What it does is pose a series of practical questions about the manner and significance of (allusive) intertextuality, and these are as much the analytical result of the practice of intertext-searching as a road map or model for that enterprise: the discussion is persistently open-ended and non-prescriptive, and the conclusion looks forward to the rest of the volume for answers. So, here too, illumination of the Homer–Herodotus relationship comes precisely from examining the details of Herodotus text.

The present essay is resolutely in the same tradition. I start in §§1–2 with some comments on ancient responses to the relationship between Homer and Herodotus (something also touched on by Tribulato) and on Herodotus’ explicit references to Homer (the topic of Harrison and Haywood), but the bulk of the essay (§3) deals with allusive intertexts (like Barker, Donelli, Fragoulaki and Tribulato). In this section I have attempted to bring within a single expository framework a wide variety of such intertexts—some relatively visible in the existing literature (including other parts of this volume), some less so or not all.1 §4 attempts a summary."

Christopher Tuplin "Poet and Historian: The Impact of Homer in Herodotus' Histories" in Ivan Matijasic (editor) Herodotus-The Most Homeric Historian?, Histos Supplement 14 (2022).

The whole text of the paper of Pr. Christopher Tuplin can be found on:

Christopher J. Tuplin is Gladstone Professor of Greek at the University of Liverpool. He is the author of The Failings of Empire (1993), Achaemenid Studies (1997), and some 140 research essays on Greek and Achaemenid Persian history; editor of Pontus and the Outside World (2004), Xenophon and his World (2004), and Persian Responses: Cultural Interaction (with)in the Achaemenid Empire (2007); and co-editor of Science and Mathematics in Ancient Greek Culture (2002), Xenophon: Ethical Principles and Historical Enquiry (2012), and Aršāma and his World: The Bodleian Letters in Context (2020). His current major project is a commentary on Xenophon’s Anabasis.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LESSON 4: PATTERNS OF PARAGRAPH DEVELOPMENT

In our 4th lesson, we discussed the different patterns of different paragraph development and I've learned that patterns of paragraph development refer to different ways in which paragraphs can be structured to effectively convey information, ideas, and arguments to readers. It is a way of developing your paragraph in a more specified and organized manner. There are various patterns of paragraph development and their importance that I have learned throughout our discussion. This includes narration, description, exemplification, compare and contrast, cause and effect, definition, and classification.

All of the given topics are very comprehensible and easy to follow. Thus, I have realized the importance of the entirety of the lesson. Patterns of paragraph development are important in writing for several reasons: there is clear communication of ideas, it is reader engagement, and develops emphasis and focus.

Communication of ideas: Paragraph development patterns provide a foundation for efficiently presenting concepts to readers. Writers can structure their paragraphs in a cohesive and structured manner by following known patterns such as narrative, descriptive, expository, argumentative, compare and contrast, and cause and effect. This enables the straightforward presentation of ideas, supporting evidence, and logical evolution of thinking, which improves the overall conveyance of the desired message to the reader.

Reader Engagement: Well-crafted paragraphs that follow recognized development patterns can attract and hold the reader's attention. Using narrative or descriptive patterns, for example, might result in vivid and engaging paragraphs that attract readers to the text, increasing their likelihood of continuing to read with interest. Readers who are engaged are more likely to be open to the writer's ideas and arguments, resulting in a more effective and convincing piece of writing.

Emphasis and Focus: Paragraph development patterns can be utilized to stress and focus on key components of the issue being discussed. A descriptive pattern, for example, can be used to convey rich details and sensory information about a subject, whereas an argumentative pattern can be used to effectively establish and defend a position. The use of suitable development patterns assists writers in emphasizing and emphasizing essential arguments, supporting facts, or instances, resulting in a more impactful and successful piece of writing.

In conclusion, patterns of paragraph development are important in writing as they provide a structured framework for organizing ideas, engaging readers, conveying messages clearly, and enhancing the overall effectiveness of the writing. By utilizing appropriate patterns of development, writers can create paragraphs that are coherent, engaging, and persuasive, leading to more effective communication of their ideas to the reader.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

*kicks in door* YOU

ANd have some asks too!

29. What’s something about your writing that you’re proud of?

41. Who’s your favorite character you’ve written?

79. Do you have any writing advice you want to share?

Have a good one!!

Thanks for the asks!

29. Something I think I've improved on is resisting the urge to infodump. Especially when it comes to worldbuilding or character backstories, I've learned to pull back and just drop breadcrumbs here and there. You know, trust the reader to put the puzzle together themselves instead of just smacking them with a giant block of expository text.

I've definitely been putting it into practice with Prince of Death -- if I indulged every impulse I had to go on a lore/history/backstory tangent, we'd be fifty chapters in and Godwyn would probably still be unstabbed.

41. Probably Miquella in Prince of Death. I thought he was going to be really difficult to write being a) a child (sort of), b) a smart person, and c) a charismatic leader. Any one of these alone is difficult to pull off, at least for me, but I think I found a good vibe for him.

Ranni is also a lot of fun to write, and I'm looking forward to getting to the part where she rejoins the main plot!

Also, honorable mention to Sir Lucien. I created the character basically just because I needed to put a name and a face to the captain of the Haligtree infantry, and he sort of grew to become his own thing. People seem to like him!

79. I'll give two pieces of advice, one mechanical and one style-related.

Mechanical - If possible, use a stronger noun or verb instead of adding an adjective or adverb.

Examples: Instead of "moved quickly" use "rushed," "sprinted," etc. Instead of "said quietly," use "whispered." Makes everything feel more focused and streamlined, and paints a more vivid image.

Style - Read "how to write" books, but don't take anything in them as gospel. For instance, just about every "how to write" book I've read says to hardly ever use flashbacks. But I think the flashbacks are some of the best parts of Prince of Death, and they seem pretty well received overall. Every project is different, and a style choice that works for one may not work for another.

Thanks for playing!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Answering the Prompt

This guide assumes you are writing based on an assigned prompt from your English professor.

Most high school and college-level English essays are in response to a given prompt about a text read in class. How you respond to the prompt depends on the kind of essay you’re writing.

The most common types of essays you will be assigned are:

Argumentative (also called a “Persuasive” essay)

Expository (also called an “Explanatory,” or “Informative” essay)

Narrative (also called a “Personal” essay)

Argumentative essays are the most commonly assigned in English classes (and will be our main focus in this guide). These essays are written in order to sway the reader’s opinion. For example, you may write an essay telling the reader to buy cloth bags, citing pollution and saving money as reasons for them to buy into your argument. Or for literary classes, you might write an essay arguing that the wolf in the tale of Little Red Riding Hood is allegory for insurance companies.

Expository essays inform or elevate a reader’s understanding of subject matter. These are fully impartial and serve to explain an idea or concept without urging the reader to be for or against the idea. Other kinds of essays do include some level of exposition in their introductions, but differ in their purpose and in the remaining content of the essay.

Narrative essays ask you to apply your lived experience to the theme or the central message of the assigned text. For example, a class focused on academic texts may ask you to reflect on stressors in your life and how you can handle them in the future, based on the articles you’ve read in class. This is one of the only times using personal pronouns (ie. you, yours, me, I, my, etc.) is appropriate in an academic setting.

Back

0 notes

Text

The Fishmonger Example: On The Distinction Between Backstory, World-Building and Lore

I tend to be a stickler for grammar, structure and words having meaning, which is a frustrating prospect when you live in a world (The Internet) increasingly bereft of basic literacy. You cannot even begin to complain about terminally online children hooked on LORE videos growing up to be media illiterate when they do not even understand what LORE is and how it works in the context of a narrative. To make you understand how strongly I feel about this: I used to be the former film student guy who would get legitimately mad at random strangers using the word Meta to mean "Self-Referential" when you needed to attach it to another Goddamn noun in order for it to effectively mean what you wanted it to mean, because it's a prefix! Meta, on its own, translates from Greek to "After" or "Beyond." It's epistemologically used to signify "About" in reference to nomenclature attached to it. What you want to say is "Meta-Text" or "Meta-Textual." Everyone is wrong about it and it drives me insane! I am sorry but this is very important to me.

Anyway, this is going to sound both condescending and pedantic on my part but I am legitimately invested in helping people understand the important differences between such terms as Backstory, World-Building and, in fact, Lore, when it comes to their respective roles within a story. To that end, I devised a simple teaching method I like to call The Fishmonger Example. Here's how it works.

Let us envision a basic scenario where you are writing a story and it's about a character going out to town in order to buy fish. What's the backstory? Mother asked the protagonist to go out and buy fish. By providing this knowledge, your reader learns both about the character's motivation to buy fish and the narrative context that informs the plot going forward. Backstory is, as the name suggests, a story event that takes place before the current plot and it's meant to work as its foundation. It can be anything from a big expository voice over introducing the history and stakes of a fantasy epic (backstory for the overall fiction) or it can be about the personal, pre-existing journey of your character which, in turn, shall inform their arc in the story.

Now, let us create a situation where the protagonist, on their quest to buy fish, does not know where to find fish in the first place. So, they ask around in town and they get eventually pointed to the "mysterious" Fishmonger. They learn The Fishmonger is the one you want to see if fish is in your future. They also learn where to find The Fishmonger so they can fulfill their destiny of finally purchasing the Holy Meal in the name of their queen - as in, mother. This is what we call World-Building. World-Building is a narrative tool that allows your reader to learn more about the setting and the characters inhabiting said setting. Its implementation within the story should come organically as the protagonist engages with the plot at hand and as the readers follow their exploits, becoming increasingly more invested in this sacred quest for fish. The trope of a character not knowing vital information is often used as an excuse to introduce elements that the reader requires to know in order to better grasp the fiction you have created. World-Building can be both heavy-handed or subtle depending on how good of a writer you are but if you managed to capture people's interest in your diegesis then I would call that a success.

So, you have found The Fishmonger and procured the fabled fish of legend. However, for some reason, The Fishmonger is feeling chatty. He really wants you to know all about his noble profession. As such, he hands you an old, untethered tome titled THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF FISHMONGERING! written by a man named Fishbert McSharkton III (esquire). This book does not help your character in their quest for fish procuration in the slightest. Your reader does not need this book in their life as it adds nothing meaningful to the plot. In fact, one could forget about this awkward exchange in its entirety and nothing of value would be lost. Alternatively, one could choose to read the tome if they were really, inexplicably fascinated by the Art of Fishmongering. In either case, THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF FISHMONGERING by Fishbert McSharkton III (esquire) is superfluous reading material. That is Lore, in a nutshell. Lore is a collection of notes and anecdotes that may or may not exist within your fictional world as inessential extra. It is neither knowledge about the setting actively conveyed through plot progression (World-Building) nor important background information for your main plot (Backstory) but merely something you might feel inclined to treat as an Easter egg for fun. It's not an element that exists for the benefit of storytelling, it's an element that exists for the benefit of your more hardcore fans who are REALLY into Fishmongering - to a, frankly, distressing degree. Mind you, there is nothing inherently wrong in enjoying LORE but if one becomes unreasonably invested in it, they might just run the risk of missing the forest for the trees. The forest being the actual text before them, that is.

To summarize:

Plot = character goes to buy fish.

Backstory = character's mom asked them to go buy fish.

World-Building = character learns where to buy fish and from whom. The setting is more fleshed out.

Lore = Fishmonger hands character a book about Fishmongering. It does not add anything to the quest for fish but it's there if one should care about Fishmongering.

I sincerely hope this example was useful to you or to one of your LORE DEEP DIVE videos addicted friends. This might also help you distinguish good writers from complete hacks. It should go without saying that I do not intend for this to be read or interpreted as a "legitimate" academic tool of study but, rather, as a beginner's guide of sorts: a way to get people started on their own journey, so to speak, but nothing more educational than that. After all, I am merely some manner of living organism inhabiting an abstract space. You should not get all your learning from random people on the Internet is my point. There is definitely something valuable to be gathered from using easy-to-understand examples or analogies to get the ball of Knowledge rolling but, as my own academic field is more broadly about media literacy than traditional literacy, I am certain that my "Quest for Fish" could use some improvement. I encourage you to discuss, add, contest or detract from it, craft your own theories or teaching methods, get a discussion going. Go crazy! I will see you all at the Fish Market of Ideas...

...

That was a clever way to end this article, right? RIGHT!!?

---

Find Madhog on:

YouTube

Twitter

Bluesky

Blogger (blog archive)

Also, here's a helpful website: https://arab.org/

This is where The Fishmonger Example originated.

#madhog thy master#the fishmonger example#lore#backstory#world-building#fish#deep dive#meta#lesson#media literacy#literacy#LORE#LORE DEEP DIVE#Scott Cawthon is a Hack and a POS#easter egg

1 note

·

View note

Text

LESSON 4: PATTERNS OF PARAGRAPH DEVELOPMENT

During our 4th lesson, we explored various patterns of paragraph development. I discovered that these patterns refer to different ways of structuring paragraphs to effectively convey information, ideas, and arguments. They provide a specific and organized approach to paragraph writing. Our discussion covered important patterns such as narration, description, exemplification, comparison, cause and effect, definition, and classification.

Understanding these patterns was crucial as they offer clear communication of ideas, engage readers, and emphasize key points. Firstly, these patterns enable writers to present concepts in a cohesive and structured manner. By following known patterns, such as narrative, descriptive, expository, argumentative, and cause and effect, writers can effectively convey their ideas and supporting evidence, facilitating a better understanding of the intended message.

Secondly, well-crafted paragraphs following these patterns can engage readers. Through techniques like narrative and descriptive patterns, writers can create captivating paragraphs that draw readers into the text, increasing their interest and receptiveness to the writer's ideas and arguments.

Lastly, paragraph development patterns help writers emphasize and focus on key elements of the topic at hand. Whether through descriptive details or persuasive arguments, these patterns enable writers to highlight important points, supporting facts, or examples, resulting in more impactful and successful writing.

In conclusion, patterns of paragraph development are essential in writing. They provide a structured framework for organizing ideas, engage readers, and enhance the overall effectiveness of communication. By utilizing appropriate patterns, writers can create coherent, engaging, and persuasive paragraphs that effectively convey their ideas to the reader.

0 notes

Text

A guide to writing an A+ essay

Welcome to my comprehensive guide on writing an essay! While writing a paper can seem intimidating, with a good plan, adequate research, thoughtful consideration of the material, and strong writing skills, you can craft a successful, well-written paper.

What is an Essay

An essay is a type of academic writing that combines personal opinion, research, and analysis to make an argument. Many types of essays can be written, including argumentative and persuasive essays, expository and reflective essays, and other less common types of essays. It is essential to understand the purpose of the essay and the type of essay before starting to write.

Writing an essay can be broken down into a series of steps. These include:

Choose a topic – Take the time to carefully choose a topic that aligns with the purpose of the essay.

Research – Consult sources like books, online databases, and websites to gather relevant information and evidence.

Brainstorm – Make a list of ideas, perspectives, and arguments related to the chosen topic.

Outline the essay – Create an outline of the arguments and evidence you will use to craft the essay.

Write the essay – Create a clear, concise, well-organized essay that supports the chosen topic and aligns with the thesis statement.

Revise the essay – Make sure that all information is accurate and well-referenced, and arrange any ideas or arguments logically.

Proofread – Double-check for any errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, format, or other issues.

Rules of Structuring and Citing an Essay

When you structure an essay, it is important to keep the five-paragraph essay structure in mind. This includes an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Within each paragraph, make sure ideas are presented clearly and with specific evidence and examples.

When citing sources in an essay, make sure to provide parenthetical citations in-text and a reference page that properly credit the sources used within your essay. Different writing styles (such as MLA or APA) require a specific method for crediting sources, so be sure to follow your professor's expectations.

Useful Resources for Students to Write a Good Essay

The internet offers many resources to help you successfully craft a good essay. This includes how-to articles, course materials, and essay templates. Online writing support is also available through services like essaymarket.net, which can provide useful advice and assistance from experienced writers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, crafting a successful essay requires careful research, planning, and writing. With a clear topic, plenty of evidence and examples, and a solid review and proofreading process, you can write a quality, well-constructed essay. Remember to follow the professor's expectations for formatting and appropriate research and sources.

0 notes

Text

"I have been teaching in small liberal arts colleges for over 15 years now, and in the past five years, it’s as though someone flipped a switch. For most of my career, I assigned around 30 pages of reading per class meeting as a baseline expectation—sometimes scaling up for purely expository readings or pulling back for more difficult texts. (No human being can read 30 pages of Hegel in one sitting, for example.) Now students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages and seem to walk away from readings of as little as 20 pages with no real understanding. Even smart and motivated students struggle to do more with written texts than extract decontextualized take-aways. Considerable class time is taken up simply establishing what happened in a story or the basic steps of an argument—skills I used to be able to take for granted."

Not thrilled to see that "piss on the poor" reading comprehension is becoming a nationwide issue

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

# Notes on Essay Writing

The Beginner's Guide to Writing an Essay | Steps & Examples

What is an essay?

We have many different definitions of essay, but we confine with two of them.

An essay can be defined as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade.

An academic essay is a focused piece of writing that develops an idea or argument using evidence, analysis, and interpretation.

Types of Essay

There are many different types of essay, but they are often defined in four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive essays.

There are many types of essays you might write as a student. The content and length of an essay depends on your level, subject of study, and course requirements. However, most essays at university level are argumentative—they aim to persuade the reader of a particular position or perspective on a topic.

Argumentative and expository essays are focused on conveying information and making clear points, while narrative and descriptive essays are about exercising creativity and writing in an interesting way. At university level, argumentative essays are the most common type.

Essay Writing Process

The essay writing process consists of three main stages:

Preparation: Decide on your topic, do your research, and create an essay outline.

Writing: Set out your argument in the introduction, develop it with evidence in the main body, and wrap it up with a conclusion.

Revision: Check your essay on the content, organization, grammar, spelling, and formatting of your essay.

The above can be further broken down or explained more>

1. Preparation

Define your essay topic

Do your research and gather sources

Come up with a thesis

Create an essay outline

2. Writing

Write the introduction

Write the main body, organized into paragraphs.

Write the conclusion

3. Revision

Evaluate the overall organization

Revise the content of each paragraph

Proofread your essay or use a Grammar Check for language errors

Use a plagiarism checker.

Similarly, essay can be written by following the below writing process.

Writing Process Steps

Most writers go through the same primary stages of writing when preparing a paper, story, article, or other text. There are five commonly identified writing process steps:

Prewriting: planning such as topic selection, research, brainstorming, and thesis development;

Drafting: creating a first version or draft of the text;

Revising: reviewing the content of the text;

Editing: polishing the details and mechanics of the text;

Publishing: preparing the final product

Each of these five steps of the writing process will be explored further below.

Prewriting: the First Step in the Writing Process

Prewriting is the first step in the writing process and includes any work a writer does before producing a formatted document. In other words, if the end goal is a five-paragraph essay, prewriting is every step that comes before actually writing five paragraphs. Prewriting is sometimes called the planning stage. Prewriting activities include:

Topic selection: A topic may be assigned by a teacher or selected by a writer. The writer should consider both the audience and the goal of their writing. When choosing a topic, a writer must also identify the writing they will produce, such as narrative, persuasive, or expository.

Research: Some types of writing require gathering information from various sources. Writers should choose current, reliable, valid sources and keep track of which information came from which source.

Brainstorming: Brainstorming is a gathering of ideas. There are many ways to brainstorm, including:

Free writing: On a blank piece of paper, write everything that comes to mind on the chosen topic. Write continuously for several minutes. When finished, go through the free writing and highlight words, phrases, and sentences useful in the writing.

Graphic organizers: Graphic organizers come in almost limitless varieties. They have in common a visual way to write and connect words, phrases, and ideas. A graphic organizer might look like a spider web, with circled words connected by lines, or it might look like a flowchart showing which ideas come first, second, third, etc.

Lists: Simple lists of items that need to be included in a text can be an effective means of brainstorming.

Pictures: Drawing pictures of text elements can be a way to organize thoughts during the brainstorming stage.

Thesis development: A thesis is a concise statement of the central idea or argument of the text. The thesis, presented as part of the introduction, informs the reader of what the author intends to accomplish in the text. A writer should experiment with several versions of a thesis statement, then choose the one that best fits the text.

DESCRIPTIVE ESSAY

What is a Descriptive Essay?

The word "descriptive" comes from the word "describe," which means "to tell about how something looks, feels, smells, sounds, or tastes." A descriptive essay is a piece of writing that describes something, such as an object, place, person, or event.

In another words,

WHAT IS A DESCRIPTIVE ESSAY?

The descriptive essay is a genre of essay that asks the student to describe something—object, person, place, experience, emotion, situation, etc. This genre encourages the student’s ability to create a written account of a particular experience. What is more, this genre allows for a great deal of artistic freedom (the goal of which is to paint an image that is vivid and moving in the mind of the reader).

In summary

Lesson Summary

A descriptive essay describes or tells about something that the writer has experienced. Topics may include an object, place, person, or event. Descriptive essays "show" readers what the writer has experienced by using illustrative language such as imagery (language that appeals to the five senses), figurative language (comparisons between unlike things), and precise language (concrete details). Three types of figurative language are similes (comparison using like or as), metaphors (comparison using is), and personification (giving human qualities to something that is not human).

What is the Purpose of a Descriptive Essay?

A descriptive essay is meant to show the reader, through the use of illustrative language, something that the writer has experienced. Writing teachers often instruct their students: "Show, don't tell." This means that writers should strive to create a picture in the minds of their readers rather than simply telling their readers about the setting, the characters, etc. For example, a writer could directly tell the reader that it was raining, but it would be more effective to show the reader that it was raining by using specific details and descriptive language. Good writers are able to create such effective descriptions that their readers feel like they are experiencing the subject matter firsthand.

What are the basic elements of a descriptive essay?

A descriptive essay describes an object, person, place, or event that the writer has experienced. Writers use illustrative language to "show" the reader that topic that is described in the essay. Through the use of imagery, figurative language, and precise language, a writer can create effective descriptions that create images in the reader's mind while also conveying a certain mood, or feeling, about the essay's subject.

How do you write a descriptive essay?

To write a descriptive essay, choose a topic to describe: a place, object, person, or event. Next, gather specific details about the topic and write them down. Use imagery and figurative language to describe the details in a way that helps the reader "experience" the topic. Choose how to organize the details: spatially, chronologically, or from general to specific. Then, create an outline of the essay with an introduction, body, and conclusion. Use the outline to write the essay while remembering to include specific details and illustrative language about the topic.

Similarly, Descriptive essay is one of the types of essays in English language. To write this kind of essay in a WebQuest online learning strategies, one is required to describe a person, object or event as vividly as possible so that the reader feels like he/she could reach out or touch it www.roanastate.edu/owl/describehtml. The description should be so clear to enable the reader to capture the picture of the item. Descriptive essay has features that distinguish it from other types of essays. It is a kind of essay that you are expected to write about something as you see it or hear about it. This type of essay calls for actual description of items.

Characteristics of a Descriptive Essay

Writers "show" by using imagery, figurative language, and precise language.

An image is a representation of something. A photographer can take an image of a woman with a camera, a painter can paint an image of a woman, and a writer can describe an image of a woman. Imagery is language that creates an image in readers' minds by addressing the five senses: sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch. Writers can make their readers see, smell, taste, hear, and feel what it is like to go to the beach by using only words. They describe the sight of the cloudless blue sky and sparkling turquoise water, the fishy smell of the breeze, the salty taste of the sea air, the sound of seagulls squawking and waves crashing, and the feel of hot, gritty sand under one's feet. The sensory details create a vivid image that shows the reader what it is like to experience the beach.

Describe a place you love to spend time in,”

What title you can give this passage or this descriptive essay?

On Sunday afternoons I like to spend my time in the garden behind my house. The garden is narrow but long, a corridor of green extending from the back of the house, and I sit on a lawn chair at the far end to read and relax. I am in my small peaceful paradise: the shade of the tree, the feel of the grass on my feet, the gentle activity of the fish in the pond beside me.

My cat crosses the garden nimbly and leaps onto the fence to survey it from above. From his perch he can watch over his little kingdom and keep an eye on the neighbours. He does this until the barking of next door’s dog scares him from his post and he bolts for the cat flap to govern from the safety of the kitchen.

With that, I am left alone with the fish, whose whole world is the pond by my feet. The fish explore the pond every day as if for the first time, prodding and inspecting every stone. I sometimes feel the same about sitting here in the garden; I know the place better than anyone, but whenever I return I still feel compelled to pay attention to all its details and novelties—a new bird perched in the tree, the growth of the grass, and the movement of the insects it shelters…

Sitting out in the garden, I feel serene. I feel at home. And yet I always feel there is more to discover. The bounds of my garden may be small, but there is a whole world contained within it, and it is one I will never get tired of inhabiting.

For further readings, visit the below websites

www.study.com

www.scribbr.com/category/academic

www.123helpme.com

www.collegeessay.org

1 note

·

View note

Text

You can't judge a book by it's cover, but you really should be able to

This is an expanded, more focused discussion of a topic I've already covered (in an earlier and more adults-focused piece, some all-ages-friendly pieces of which I have directly lifted into this essay here), but it's a topic very near and dear to my heart so I'm addressing it again in more detail here, and without so much 18+ baggage, so feel free to share this version among younger readers, or just appreciate it as an expansion of my other writing. You do you. I'm not here to judge.

Or am I?

Because I have a bone to pick with the publishing industry, and it's a grudge that has been steadily growing for years now.

The publishing industry has gone crazy with the expression "you can't judge a book by its cover". So crazy, in fact, that they have apparently resolved to make judging a book by its cover flat out impossible.

I'm gonna lead with some examples that illustrate ineffective or even outright bad cover art. None of these examples are meant to throw shade on the actual book or it's author; we're dragging bad cover art here. I leave your assessment of the actual books where it belongs: with you, the readers.

The cover to The Fifth Season commands attention grabbing use of color and lighting. It's well planned, with the details pushed to roughly a quarter of the cover leaving room for well spaced and sectioned text and awards and such. But what kind of book is it? Is it a murder mystery? A political thriller? A science fiction novel? Without reading the back of (or, if the back is given over to other authors heaping praise on prior works by the author, as award winners are wont to do, the text of) the book itself, you have no way of knowing what you're signing up and putting money down for.

The reprint cover for Fellowship of the Ring is arguably even worse, in that it is both lazy — literally just a photo of an actor from Amazon's upcoming Rings of Power web series (oh god that travesty is still happening) — and also that it critically misrepresents the essential nature of the story to a prospective reader who is unfamiliar with the work.

Fellowship of the Ring is NOT a high fantasy adventure novel as we have come to understand the genre. It is a pensive, ruminative, lengthy, and expository work that is difficult to quantify because it is so very NOT like the subsequent and faster-paced works it has come to inspire. It is paced like a history book, or a series of university lectures. It is Tolkien painstakingly creating a modern mythology for the peoples of the British Isles, and it contains lists of kings, songs from times long concealed by the mists of advancing history, and memorable folk heroes to that end; indeed, we now know of Frodo Baggins and Gandalf the Grey as strongly as we know of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. But that's not the story this cover is representing; its subject matter, the fully armored warrior with dagger in hand, fixating on martial elements... all that promises a different story: a collection of great battles and tales of valor. It is a willful and fundamental misrepresentation of the work and the story a reader will encounter. I would even go so far as to say that cover outright lies about the book.

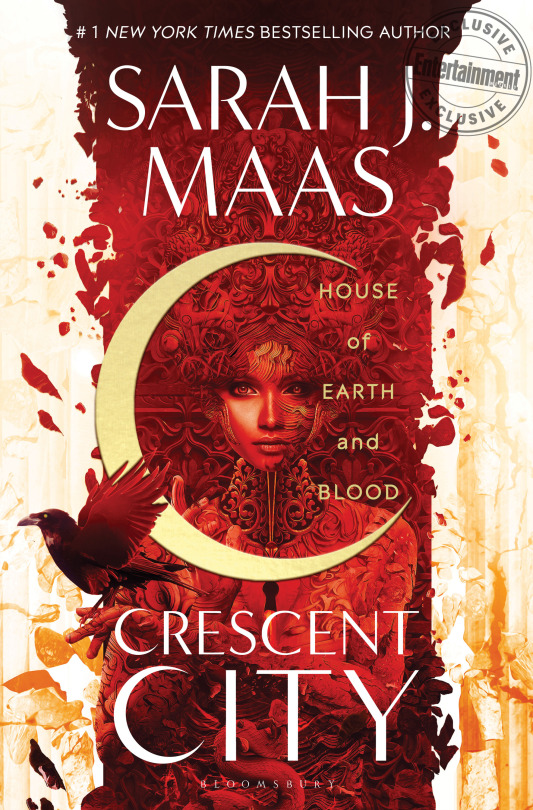

Finally, we come to Crescent City, for which I make an additional point: just because it's bad cover art doesn't make it bad art. Those are not necessarily overlapping things. Crescent City's cover art is beautiful. I would love to have that on my wall. Are you kidding? It looks amazing! It is definitely the work of an artist of skill and passion and I in no way wish to understate that. Unfortunately, it fails as the cover of a book, because I know nothing about this story from looking at it.

Now, again, I am NOT saying the art is low quality. I find the first two examples uninspired, perhaps, but it's not bad art. All three effectively grab your eye on a shelf through their pictorial qualities, but they ARE BAD COVER ART.

But what makes them bad covers?

They are bad covers because grabbing your eye is 100% of what they do.

They grab your eye. That is all they do. They do nothing to help a prospective reader decide if the story contained within is remotely the kind of work they'd be interested in.

Now, let's see a couple of covers that really understood the assignment and pulled off some EXCELLENT cover design.

Holy shit it's a Twilight.

But seriously, hear me out, because this is amazingly good cover art.

This says a TON about the story. The hands are young and pale as snow, befitting our leading man being an eternally-17-year-old vampire. The red apple contrasts the white and black tones, but more than that, immediately evokes the near omnipresent image of the Forbidden Fruit of Eden, symbolizing Bella's pursuit of Edward as this enticing, dangerous thing that goes strongly against the rules of nature; Midnight Sun would later take that imagery even further with its own cover. Hell, even the FONT used for the title says something (though possibly unintentionally), with the use of flourishes that hint at the narrator's tendency towards purple prose.

This is an AMAZING cover. It grabs the eye, and says a LOT about the story and themes within.

How about another take on Fellowship of the Ring?

This is the cover my hardcover copy uses. This is perfection. This tells you so much about the story.

From the dark, predominantly grey, palette, you can tell this will not be the happiest of tales, yet that solitary shaft of light promises the feeble but always present hope that the Fellowship's quest will depend on. The environment is MASSIVE compared to the characters, which conveys the enormity of both their task and their quest to achieve it, and also their near helplessness in the face of the odds they will strive against. And, befitting the only book in which the Fellowship is actually together for an appreciable length of time, all nine of them appear on this cover, huddled together, depending on each other to get through the vaults depicted. Even if you know nothing about Fellowship of the Ring, one look at this cover promises a grand tale, epic in scope, and that it will be one fraught with ups and downs for its characters.

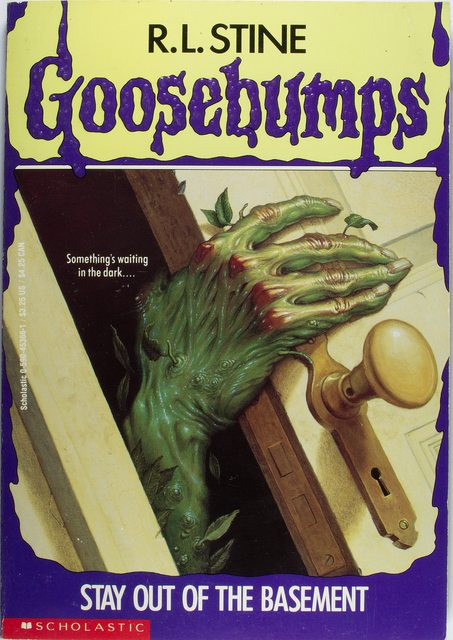

Finally, there is the original art of the Goosebumps series by R.L Stine.

I love these because they are so marvelously unsubtle, which of course works especially well for children's literature.

You can see all the elements I have discussed previously on full display here: a strong visual style (in this case a sort of neo-pulp style that mirrors the pulp-horror style of writing that R.L Stine adapted to children's tastes so well) that initially grabs the eye, and hints at the tale to come. Whether it's the plant-man creeping from the darkness, the evil mask coming to life, or the cracked and smoking crystal ball, each cover tells the person about to read it exactly what they need to know. And if it weren't obvious that these are tales of horror and thrills, there's the VERY on-point series name and logo. There are no misjudgments about the contents to be had here. You will never pick up a Goosebumps book expecting a delightful rom-com, because the covers do their damn job: calling your attention, communicating their contents, and helping you decide if this is at all the sort of book you want to be reading.

The Goosebumps books not only understood the assignment, they showed the rest of the class how it ought to be done.

I say all this with love: modern publishing is drowning in a sea of cover art that doesn't understand what it's supposed to be doing. Either it's bland and uninspired, fails to help the buyer make a real decision about the work, or at worst outright lies in an effort to squeeze out a purchase, and nobody likes being lied to when their time and money is on the line. I understand that publishers want to make money, but it is not enough to be merely visually striking. Looking good is not enough. The cover of a book is the first and most effective means by which a reader can be drawn to it when it's on a display shelf. It is a precious chance at a first impression; when publishing your work, don't allow yourself or anyone else to waste that chance. Authors and publishers don't have to go as hard and unsubtle as Goosebumps did, but they should hold their works to the basic fundamental principals that Goosebumps' covers operated by.

Because not only CAN you ideally judge a book by its cover, you SHOULD be able to. That's the default option. That's why we put art on the covers to begin with.

#here endeth the lesson#literature#books#publishing#publishing industry#fiction#cover art#art#goosebumps#lord of the rings#lotr#fellowship of the ring#sarah j maas#crescent city#r l stine#the fifth season#n k jemisin#nk jemisin#rl stine#twilight#stephanie meyer

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! Do you have any writing tips/things you wish you'd known as a beginner? I'm trying to learn and any tips would help a lot fldkjfdkf

Sure!

1) make sure your dialogue tags/actions stick with your correct dialogue, and that you separate the next person's dialogue/actions. For instance:

"What are you doing?" she asked

He shrugged. "I don't know."

(Good!)

vs

"What are you doing?"

She asked. He shrugged. "I don't know."

(Poor)

or "What are you doing?" she asked. He shrugged. "I don't know."

(Technically okay, but separating the two on separate lines makes it easier to read)

2) Make sure you know and use all of the right speaking punctuation. There's a lot of rules, basic ones:

If your character ends their statement with a "?" or a "!" before a dialogue tag, the tag is not capitalized. If you end with a period, the next sentence IS capitalized. If you want the tag to go with the sentence, don't end the sentence with a period, end it with a comma. For example:

"I don't like this." she said. (no) "I don't like this," she said. (yes) "I don't know," she set down the vase. (probably not) "I don't know." She set down the vase. (probably correct)

If your character is finishing a statement, then dialogue tag, then another statement, you end the dialogue tag with a comma, then do the quotes. If the two lines are separate sentences, then the sentence is capitalized. If it's a continuing statement, then the sentence is NOT capitalized. If you're not sure which you want, read it in your head without the dialogue tag with where the inflections are. Same goes for statements ending with ? and !

"We don't know," she said, "we don't know anything." (Reading the sentence in your head, delete the dialogue tag: We don't know, we don't know anything)

"We don't know," she said, "We don't know anything." (Reading out as one sentence: "We don't know. We don't know anything."

"Who are you?" she asked, "Where did you come from?" (two separate sentences)

"What is that?" she asked in a sneer, "and where did it come from?" (one sentence, the dialogue tag could also just go at the end and put the two together, that's just personal preference)

3) Italics and adverbs are good used in the right places

4) Remember character voice when you're narrating/using expository text: if you're describing something from their perspective (as opposed to an omniscient one), and their regular dialogue wouldn't use a huge, complex word, then probably their perspective description wouldn't either.

5) You don't need dialogue tags after every line of dialogue, establish who spoke first, who spoke second, and then, as long as you follow other dialogue rules, you just need to throw a couple in every once in a while for longer back and forths so the audience remembers who's talking without having to go back to the beginning to track the conversation. Or, if your character is performing an action with their dialogue. It gets trickier the more characters you add into the conversation.

6) Pronouns, oh my gosh. My general rule of thumb is I think two to four pronouns referring to them before you say their name again (sooner if you're dealing with multiple characters/objects with the same pronouns). For instance:

Gerald ate the orange. He wasn't usually fond of oranges, but he'd make an exception today. After all, it was his special day. Gerald threw the peel in the trash. Time to go.

OR, use another descriptor of them.

Gerald ate the orange. He wasn't usually fond of oranges, but he'd make an exception today. After all, it was his special day. The tall man threw the peel in the trash. Time to go.

Anyway, those are the main ones I can think of, good luck with your writing!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Tips for Improving the Word Economy of Your Writing

What Is Word Economy?

In writing, word economy refers to careful management of the words that end up in your text. In the simplest of terms, it means keeping sentences, paragraphs, and chapters as short as they can be without degrading your storytelling or rhetoric.

Does striving for economy of words mean that authors have to constantly track their word count and try to reach a fixed quota for overall words? No it does not.

But it does mean that you need to monitor your word choice to make sure you aren’t filling your prose with superfluous words that make sentences longer but not necessarily better. When you review your own work, ask yourself: “Could I communicate this same idea using fewer words?” If the answer is yes, then rewrite the relevant sentences and paragraphs with that in mind.

Use the active voice. When writing in the active voice, the subject of a sentence performs an action. Passive voice sentences contain subjects that are the object of the sentence’s verb. They are not the “doer” of the sentence; they are the recipient of an action. Sentences constructed with the active voice use fewer words and are easier to understand.

Use strong verbs. If you want to revise a sentence to make it better, start by looking for a stronger verb. If you choose a verb that accurately describes the action of the scene, you can cut down on modifying words you might otherwise need to better explain that action. Precise, strong verbs get to the point, which is great for word economy.

Avoid wordy prepositional phrases. A lot of inexperienced writers weigh down their prose with prepositional phrases without adding any further meaning. So instead of writing, “He ran in the style of someone who was a professional athlete,” just say, “He ran like a professional athlete.”

Use the English dictionary and thesaurus effectively. Some young writers mistakenly believe that making a phrase longer will make you seem smarter. In reality, the opposite is true. Economical word choice makes your prose more fluid and clear, so use the dictionary and thesaurus to help you make phrases shorter, not longer.

Have individual scenes accomplish multiple things. Introduce a character by writing a short, solitary scene. Place your character in a situation that both advances your story and provides character development.

Keep chapters lean. Make sure each chapter has a purpose that ties in to the bigger story. Don’t fluff up the novel with irrelevant content. Establish trust with your reader that you will not waste their time with authorial indulgences.

Plan your narrative, and stick with the plan. In a thriller, for example, people want to be on the edge of their seat the whole time, and this requires narrative focus. Don’t meander too far from your main storyline—that is, from scenes and dialogue that develop your stakes.

Compress your dialogue. You should keep dialogue economical in the same way you do with your prose. Unless your character is naturally verbose, tighten up their language, conveying only the information that will deepen the character or move the story forward. Making people seem real on the page often means giving them shorter sentences. Most people are naturally economical speakers and will tend to say “I’ll go” instead of “Yes, I will go.”

Avoid info-dumping. Beginning writers tend to drop large chunks of information onto the page all at once. This is called info-dumping, and not only does it bore readers, but it stops the momentum cold. You want to make your information feel natural and interesting. You can avoid the dreaded info dump by having your characters discover information in the course of a conversation. If that feels overly expository, let them discover information via action.

Compress, compress, compress. Go through your writing and see how many words you can cut while keeping the original feel of your work. (Hint: adverbs—words like gently or beautifully that usually end in “-ly” and modify verbs or adjectives—are a good place to start.) Next, beware of places where you’ve given too much description, especially of a static object. Do you need to spend two whole paragraphs describing a building that’s not essential to the plot? One powerful detail will often do the trick.

Article source: here

#writersociety#writers of instagram#writer community#writing#writers#write#writing tips#writing advice#amwriting#writing life#writeblr#writing analytics#writer#writer stuff#writing excersise#Writing Theory#Pacing#Writing pace#Writing pacing#Writing advice writing reference#Writing reference#writers of tumblr#tumblr writers#writers of the world

178 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I wanted to love Seasonal Fears by Seanan McGuire. Middlegame was one of my best reads of 2019, a masterwork of bendy sci fi. The core of Seasonal Fears was perfect. Harry and Melanie have been in love since they were small, fully committed to one another as Melanie struggles with a lifelong heart problem that dooms her to eventually die young. But the summer king and the winter queen are dead, meaning their crowns are up for grabs. Harry and Melanie are activated as candidates, and must enter a deadly competition. If they lose, Melanie is as good as dead. If they win, the two of them live, linked and loved, for as long as they'd like. I love McGuire's worlds. The core is always her characters. Melanie and Harry are believable and romantic, both realistic about their odds and hopelessly committed to each other. The supporting cast and the elemental world is interesting, and I always enjoy elemental magical systems. But it was just too long. McGuire has a tendency to digress, and add parentheticals. It's part of her style, and I often enjoy it—there's nothing wrong with it on its own. But this particular novel, which is 476 pages in total, could have and should have been closer to 300. The digressions were much too expository and often dug themselves in circles. It really comes down to this: at a certain point, you have to trust that the reader sees what you've already demonstrated, whether it be Harry's privilege, the two teens' love for each other, or the world-building. McGuire is usually good at trusting the reader to follow her, and then using the parentheticals as bonus material or foreshadowing only. In this novel, I think there needed to be a more demanding editorial eye to cut the text down, in order to let the romance and the sharp, dangerous action take center stage. The action is cut apart by long, lengthy descriptions and exposition. McGuire also uses digressions almost apologetically (or even pedantically) in unnecessary ways—for example, explaining why Harry as a young boy understands consent so implicitly, when honestly she could have just let it be with a sentence. I was fully invested in Harry and Melanie, but around 1/4 of the way through the novel, I stopped feeling like they were in any danger. The first fourth of the book was the best part, because it built so much around Harry and Melanie and the mystery of what was going to fall onto their shoulders, and Melanie's heart condition. But the further into the book I got, the harder it was to stay as invested. The stakes, the suspense, and the dark serrated edge of McGuire's Alchemical Journeys world were blunted by its extra length. I received a copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review. Seasonal Fears is out now. Content warnings for misogynstic violence, torture, ableism, domestic abuse, suicidal ideation.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

how long did it take you to plan out kittyquest and the earth c lore? it's a really well thought out great adventure and as an aspiring fanventure creator i am curious about how long it took to get everything figured out

you might be disappointed to learn that i rushed into KQ with nary an outline to be found

i had no intention of fleshing it out into comic form and was content with faux-panels until i decide to "unless...?" myself, as i always do time and time again. from there i decided to base it purely off of suggestions (lol) and, at the threat of there being no centralized plot, thought back on the cult of the witch, which i had introduced as a gag in the pilot light, pale rapture trilogy. from there i started to build up where the plot was going to go, and several months into the adventure i formally sat down and wrote a few pages outlining roughly where the rest of the comic was headed, later splitting into sections so i would always know what i would be addressing in a given update. i could hardly fathom going back to the days of NOT knowing what i was about to be sitting down to write/draw

this is not the first time ive mentioned this, but i accidentally emulated hussie in that ramona wasnt planned from the start, and i was actually kind of scared to introduce her. i simply repurposed an adult earth c fantroll id drawn a single time and decided, you know what, this might shake things up a bit. and im glad i did that. ive strayed from the outline a few times, adding things along the way. my great, GREAT, *GREAT* hope is that it does not all fall flat in the end. a lot of people still expect KQ to be a sburb adventure, which it is very explicitly tagged as not being. KQ at its heart is something self-contained (this might age poorly) and content to tell a small-scale, relatively low stakes story, and ive never pretended that its going to be some grand epic adventure like others out there. knowing the scope of your story is important because it helps maintain a consistent mood and generally keeps you grounded. i think its okay if you dont have an end in mind, but i would recommend thinking about how youre going to get there so that things dont feel rushed, like what happened with homestuck... which i think is an example of someone spending so much time thinking about the ending that it kind of ends up being coughed up in your lap

as for earth c lore, the text portion of the field guide took maybe a couple weeks to write, though i did add and edit some text pretty recently before its release. worldbuilding is singlehandedly the most rewarding and fun part of working on KQ, i love thinking about how mundane daily life works there which really lends itself to being able to freely write pages upon pages of expository text without too much writers block. i could talk about it for hours. if you have already found an idea that youre super excited about, just write and draw as much stuff for it as you can stand to. hell, just notebook doodles and jotting stuff down in the notes app will do. it will help you have something to go off of when you actually get cracking on writing your outlines

generally i dont think theres a wrong or right way to go about making an mspfa style adventure, i know a lot of the big ones have multiple writers and artists, but im just one random guy doing this shit in my office when i get home from work. think about how much time, both short- and long-term that youre willing to commit. is it just a fun thing you want to do when you have free time? thats great! are you committed to a long form story that might take you multiple years to complete? maybe write an outline or several, ask a friend if they can beta read or help you out a little. i didnt have a plan when i started, and i still sort of feel nagged by that as KQ begins to enter its twilight years, er, twilight updates. but one mans lack of planning is another mans freedom to write whatever the hell they want

i hope this was even halfway helpful, a lot of this was probably just rambling. good luck with your stories! :)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro-Worldly

Some worlds we’ve been to, some worlds we’ve never seen. Here’s the difference between how we as players planeswalk to worlds and how planeswalkers interact with this stuff: We have tropes. We have points of observation. Kaldheim has a mix of Scandanavian lore and Viking tropes, which is something we can see in bits of pop culture. However, when Kaya went there, she had no idea that this was anything other than a way of life, that this was a world that could exist anywhere else. The anchoring is always different.

Cultural tropes and story observations go hand-in-hand as well! The culture of Ravnica is filled with oddities, and the ten guilds all have their own quirks, but it’s up to visitors from other worlds to come in and look at, say, the Simic and think that it’s weird to grow ferret-cuttlefish hybrids in test tubes. And on Zendikar, any planeswalker from a world with solid ground would marvel at the Roil, and through their eyes we get that sense of perspective. What is this world? We see all angles from behind the card, but they see all lives from inside it.

And what better way to introduce cool parts of a world than through the eyes of a multi-dimensional observer?

This week’s contest: Design a common card, set on a plane of your choice, with flavor text quoting a planeswalker not from that plane.

The Goals (M.E.O.W.):

>> Mandatory: Your card must be a common card and be appropriate in terms of power level and complexity. Your card must be set on a specific plane, but how you show that is up to you. Your card must quote a planeswalker in its flavor text, and therefore must have flavor text. The planeswalker being quoted must be a visitor to the plane on which your card is set, although it doesn’t necessarily have to be their first time there.

>> Encouraged: I think you can be a little quippy here. Imagine that you’re setting up something new for players, getting them excited about this world with characters we already know. You don’t have to tell a story necessarily or interact with the characters on the card, but what changes when you do? Think about the card types. Think about whether or not your planeswalker is an active participant or an observer. What are their goals on this plane? A winning card will show something about that planeswalker that makes me excited to see them on this world, for whatever reason that may be.

>> Optional: The plane doesn’t have to be one we’ve seen before* and it doesn’t have to call back to a previous story, although these might be helpful anchor points. Maybe it’s just a planeswalker going somewhere and saying “this is cool!” or “well this is messed up.” The level of involvement is up to you. And you don’t have to make it some grand observation! Look at some printed examples for cards that aren’t directly story/planeswalking related.

>> Warning: Make sure you read up on where planeswalkers are originally from and where they’re going. Make sure that your FT is an actual quote and not a expository snippet merely featuring your planeswalker. You can use any character that is established to be a planeswalker, but the most resonant planeswalkers will be ones with which we are familiar in some way. Keep tabs on their characterization. And again: COMMONS.

*Clarification: By this, I mean a plane we’ve seen in terms of canon but maybe we haven’t been there in a set. Azgol, Vryn, and Muraganda are examples of this.

Some good printed examples include, but are not limited to:

Soul Parry

Inspiring Roar

Negate (AER)

Kiora’s Dambreaker

Spined Thopter

Demonic Appetite

Rottenheart Ghoul

Unexpected Fangs

Bloodbriar

Seismic Shudder

Colossal Might

Soul Manipulation

Ondu Champion

NB: Not all the above cards necessarily tell the story of their plane, but are good for examples of personable quotes. If you have a very plane-specific card, you can make the quote more vague if it carries. If you have a vaguer card, you can make the quote more story/walker specific to explain it.

The goal of this contest is twofold. Firstly, I feel we could all use a little bit of a nice planeswalker story in which the planeswalking matters. Secondly, common design is actually pretty difficult to do in an exciting way, so I’m giving some flavor constraints to give a new edge to that excitement. This contest is half design and half creative writing exercise. Have fun!

— @abelzumi

“Here’s a link to the submission box,” he said. “Or here’s a link to the Discord channel,” he mentioned.

#mtg#magic the gathering#custom magic card#contest#announcement#common walker contest#inventor's fair

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ocean Vuong on Metaphor

below is a transcript of an Instagram story from Ocean Vuong, available here in his story highlights under Metaphor.

Q: How do you make sure your metaphors have real depth?

metaphors should have two things: (1) sensory (visual, texture, sound, etc) connector between origin image and the transforming image as well as (2) a clear logical connector between both images.

if you have only one of either, best to forgo the metaphor, otherwise it will seem forced or read like “writing” if that makes sense.

~

a lot of ya’ll asked for examples re:metaphor. I can explain better if I had 15 minutes of class time (apply to UMASS!). But essentially, metaphors that go awry can signal a hurried desire to be “literary” or “poetic” (ie “writing”), which can lose traction/trust with a reader. in other words, a metaphor is a detour—but that detour better lead to discoveries that alter/amplify the meaning of what is already there, so that a reader sees you as a servant of possibility rather than someone trying to prove that they are a “writer.” One is performative, the other exploratory. In this way, the metaphor acts as a virtual medium, ejecting the text’s optical realism into an “elsewhere”. But this elsewhere should inform the original upon our return. otherwise the journey would feel like an ejection from a crash rather than a curated journey toward more complex meaning.

example:

“The road curves like a cat’s tail.”

This is a weak metaphor because the transforming image (tail) does not amplify/alter the original. The transfer of meaning flattens and dies. Logic is weak or moot: A cat’s tail does not really change the nature of the road. You can certainly add to this with a few more expository sentences which might rescue the logic—but by then you’re just doing cpr on your metaphor.

Sensory, too, is weak: a cat’s tail has little optical resemblance to a road other than being curved (roads are not furry, for one.)

So this is 0 for 2 and should be scrapped. (Just my opinion though! Not a rule!)

okay so what about:

“The road runs between two groves of pine, like the first stroke of a buzzcut.”

this is better. the optical sensory of the transforming image (a clipper thru a head of hair) matches well with the original.

but the logic feels arbitrary. again it doesn’t substantially alter the original.

in the end this is just an “interesting image” but not strong enough to keep I’d say.

Now here’s one from Sharon Olds:

“The hair on my father’s arms like blades of molasses.”

Sensory connector: check. A man’s dark hair indeed can look like blades (also suggestive of grass) of molasses.

Logical connector: check. the father is both sharp and sweet. Something once soft and sticky about him (connotations of youth) sweets, has now hardened the confection no longer fresh etc.

It’s an ambitious metaphor that is packed with resonance. In other words, it does worlds of work and actually deepens the more you dit with it. A metaphor that actually invites you to put the book down, think on it, absorb it, before returning. a good metaphor uses detours to add power to the text. poor metaphors distract you from the text and leave you bereft, laid to the side.

lastly, the prior examples are technically “similes” but I believe similes reside under the umbrella of metaphor. although a simile is a demarcation, ie: this is “like” that. but this is “not”, ontologically, that.

however, I think something happens in the act of reading wherein we collapse the “bridge” and the mind automatically forges synergy between the two images, so that all similes, once read, “act” like metaphors in the mind.

but again this is all subjective. you might have a better way of going about it.

Another very ambitious metaphor is this one from Eduardo C. Corral:

“Moss intensifies up the tree, like applause.”

This is a masterful metaphor, risky and requires a lot of faith, restraint, and experience to pull it off.

Difficult mainly because we now see a surrealist “distortion” of the sensory realm: origin IMAGE (moss) is paired with transforming SOUND (applause).

There is now a leap in comparable elements. But the adherence to our two vital factors are still present.

Sensory: moss, though silent, grows slowly (the word “intensifies” does major work here becuz it foreshadows the transforming element). Applause, too, grows gradually, before dying down.

Logic: the growth of the moss suggests spring, lushness, life, resilience, and connotes anticipatory hope, much like applause. In turn, applause modifies the nature of moss and imbues, at least this moss, with a sense of accomplishment, closure, it’s refreshment a cause for celebration.

God I love words.

~

I’ve gotten so many responses from folks the past few days asking for a deeper dive into my personal theory on metaphor.

So I'm taking a moment here to do a more in-depth mini essay since my answer to the Q/A the other day was off the cuff (I was typing while walking to my haircut appointment).

What I’m proposing, of course, is merely a THEORY, not a gospel, so please take whatever is useful to you and ignore what isn’t.

This essay will be in 25 slides. I will save this in my IG highlights after 24 hrs.

Before I begin I want to encourage everyone to forge your own theories and praxi for your work, especially if you’re a BIPOC artist.

Often, we are perceived by established powers as merely “performers,” suitable for a (brief) stint on stage—but not thinkers and creators with our own autonomy, intelligence, and capacity to question the framework in our fields.

It is not lost on me, as a yellow body in America, with the false connotations therein, where I’m often seen as diminutive, quiet, accommodating, agreeable, submissive, that I am not expected to think against the grain, to have my own theories on how I practice my art and my life.

I became a writer knowing I am entering a field (fine arts) where there are few faces like my own (and with many missing), a field where we are expected to succeed only when we pick up a violin or a cello in order to serve Euro-Centric “masterpieces.”

For so long, to be an Asian American “prodigy” in art was to be a fine-tuned instrument for Mozart, Bach, and Beethoven.

It is no surprise, then, that if you, as a BIPOC artist, dare to come up with your own ideas, to say “no” to what they shove/have been shoving down your throat for so long, you will be infantilized, seen as foolish, moronic, stupid, disobedient, uneducated, and untamed.

Because it means the instrument that was once in the service of their “work” has now begun to speak, has decided, despite being inconceivable to them, to sing its own songs.

I want you, I need you, to sing with me. I want to hear what you sound like when it’s just us, and you sound so much like yourself that I recognize you even in the darkest rooms, even when I recognize nothing else. And I know your name is “little brother” or “big sister,” or “light bean,” or “my-echo-returned-to-me-intact.” And I smile.

In the dark I smile.

Art has no rules—yes—but it does have methods, which vary for each individual. The following are some of my own methods and how I came to them.

I’m very happy ya’ll are so into figurative language! It’s my favorite literary device because it reveals a second IDEA behind an object or abstraction via comparison.

When done well, it creates what I call the “DNA of seeing.” That is, a strong metaphor “Greek for “to carry over”) can enact the autobiography of sight. For example, what does it say about a person who sees the stars in the night sky—as exit wounds?

What does it say about their history, their worldview, their relationship to beauty and violence? All this can be garnered in the metaphor itself—without context—when the comparative elements have strong multifaceted bonds.

How we see the world reveals who we are. And metaphors explicate that sight.

My personal feeling is that the strongest metaphors do not require context for clarity. However, this does not mean that weaker metaphors that DO require context are useless or wrong.

Weak metaphors use context to achieve CLARITY.

Strong metaphors use context to SUPPORT what’s already clear.

BOTH are viable in ANY literary text.

But for the sake of this deeper exploration into metaphors and their gradients, I will attempt to identify the latter.

I feel it is important for a writer to understand the STRENGTHS of the devices they use, even when WEAKER versions of said devices can achieve the same goal via different means.

Sometimes we want a life raft, sometimes we want a steam boat—but we should know which is which (for us).

My focus then, will be specifically the ornamental or overt metaphor. That is, metaphors that occur inside the line—as opposed to conceptual, thematic, extended metaphors, or Homeric simile (which is a whole different animal).

My thinking here begins with the (debated) theory that similes reside under metaphors. That is, (non-Homeric) similes, behave cognitively, like metaphors.

This DOES NOT mean that similes do not matter (far from it), as we’ll see later on, but that the compared elements, once read, begin to merge in the mind, resulting in a metaphoric OCCURRENCE via a simileac vehicle.

This thinking is not entirely my own, but one informed by my interest in Phenomenology. Founded by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century and later expanded by Heidegger, Phenomenology is, in short, interested in how objects or phenomena are perceived in the mind, which renewed interest in subjectivity across Europe, as opposed to the Enlightenment’s quest for ultimate, finite truths.

By the time Husserl “discovered” this, however, Tibetan Buddhists scholars have already been practicing Phenomenology as something called Lojong, or “mind training,” for over half a millennia.

Whereas Husserl believes, in part, that a finite truth does exist but that the myopic nature of human perception hinders us from seeing all of it, Tibetan Lojong purports that no finite “truth” exists at all.

In Lojong, the world and its objects are pure perception. That is, a fly looks at a tree and sees, due to its compound eyes, hundreds of trees, while we see only one. For Buddhists, neither fly nor human is “correct” because a fixed truth is not present. Reality is only real according to one’s bodily medium.

I’m keenly interested in Lojong’s approach because it inheritably advocates for an anti-colonial gaze of the world. If objects in the real are not tenable, there is no reason they should be captured, conquered or pillaged.

In other words, we are in a “simulation” and because there is no true gain in acquiring something that is only an illusion, it is better to observe and learn from phenomena as guests passing through this world with respect to things—rather than to possess them.

The reason I bring this up is because Buddhist philosophy is the main influence of 8th century Chinese and 15th-17th century Japanese poetics, which fundamentally inform my understanding of metaphor.

While I appreciate Aristotle’s take on metaphor and rhetoric in his Poetics, particularly his thesis that strong metaphors move from species to genus, it is not a robust influence on my thinking.

After all, like sex and water, metaphors have been enjoyed by humans across the world long before Aristotle-- and evidently long after. In fact, Buddhist teachings, which widely employ metaphor and analogy, predates Aristotle by roughly 150 years.

Now, to better see how Buddhist Phenomenology informs the transformation of images into metaphor, let’s look at this poem by Moritake.

“The fallen blossom flies back to its branch. No, a butterfly.”

When considering (western-dominated) discourse surrounding analogues using “like” or “is”, is this image a metaphor or a simile?

It is technically neither. The construction of this poem does not employ metaphor or simile.

And yet, to my eye, a metaphor, although not present, does indeed HAPPEN.

What’s more, the poem, which is essentially a single metaphor, is complete.

No further context is needed for its clarity. If context is needed for a metaphor, then the metaphor is (IMO) weak—but that doesn’t mean the writing, as a whole, is bad. Weak metaphors and good context bring us home safe and sound.

Okay, so what is happening here?

By the time I read “butterfly,” my mind corrects the blossom so that the latter image retroactively changes/informs the former. We see the blossom float up, then re-see it as a butterfly. The metaphoric figuration is complete with or without “like” or “is.”

Buddhism explains this by saying that, although a text IS thought, it does not THINK. We, the readers, must think upon it. The text, then, only curates thinking.

Words, in this way, begin on the page but LIVE in the mind which, due to limited and subjective scope of human perception, shift seemingly fixed elements into something entirely new.

The key here is proximity. Similes provide buffers to mediate impact between two elements, but they do not rule over how images coincide upon reading. One the page, text is fossil; in the mind, text is life.

Nearly 5000 years after Maritake, Ezra Pound, via Fenolosa, reads Maritake’s poem and writes what becomes the seminal poem on Imagism in 1912, which was subsequently highly influential to early Modernists:

“The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals on a wet, black bough.”

Like Maritake, Pound’s poem technically has no metaphor or simile. However, he adds the vital colon after “crowd,” which arguably works as an “equal sign”, thereby implying metaphor. But the reason why he did not use “are” or “is” is telling.

Pound understood, like Maritake, that the metaphor would occur in the mind, regardless of connecting verbiage due to the images’ close proximity. We would come to know this as “association.”