#even if they weren't parent and child people should not be resorting to violence to solve arguments

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The number of times I've seen people argue that Bruce is a decent father and that he is not abusive absolutely blows my absolute mind.

Yes, you can hc whatever version of Bruce you want. You can even blame it all on bad writers or reject canon. You can claim comic!Bruce isn't your Bruce and main a different version of him. Those are all valid.

However, you can NOT say that he has ever been justified for hitting his kids. There is no excuse for him willingly laying his hands on his kids. It doesn't matter if the person is drunk, drowning in grief, lost in emotions, whatever. Hitting kids is not okay.

Continually, the physical abuse is a very obvious sign of Bruce being a shit dad in the comics. On top of that, there is so much emotional abuse and manipulation as well. He's shitty as fuck to his kids and there's no reason this is okay. He may love those kids, but that doesn't excuse his behaviors.

Anyways, reject canon Bruce all you want. There's certain aspects of other characters I reject, and DC stands for Disregard Canon. Feel free to have whatever version of Bruce you desire.

What is NOT okay is excusing or accepting canon Bruce's actions/behaviors as acceptable.

#dc comics#dc universe#batman#bruce wayne#I've seen people argue that bruce can hit his kids because they are all vigilantes#what kind of stupid ass logic is that?#tw child abuse#tw abuse#i don't like getting into arguments with people but some of these excuses floor me#“they're both adults” no. that's not how child-parent relationships work#even after a kid becomes an adult the parent still has some level of power over the kid and the relationship is not equal#bruce is and has been the adult for their entire relationship. he's the parent#even if they weren't parent and child people should not be resorting to violence to solve arguments#people out here arguing Bruce isn't a shitty dad at all and still deny it when shown empirical evidence#good dad bruce is great (and shown in some media) but isn’t universal#blame the writers or say you don't accept that version of bruce but don't say he isn't canonically shit#yes bruce can still love his kids and be abusive. the two aren't mutually exclusive#bruce wayne bashing

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

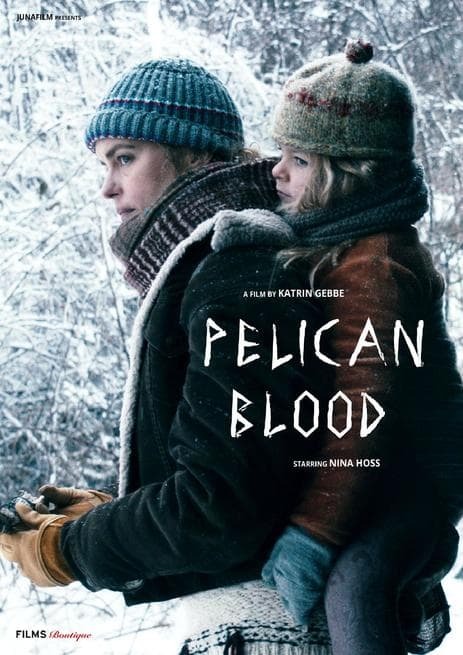

BLOGTOBER 10/8/2020: PELICAN BLOOD (2019)

If you are reading this and the present date is between October 8 and 11 of 2020, please consider buying a virtual ticket to see Katrin Gebbe’s PELICAN BLOOD, available on demand through the Nightstream festival:

https://watch.eventive.org/nightstream/play/5f6e7e78d6a9bf0036613fa3

I am about to discuss this movie and its conclusion in great detail, but it would be much better for a person to come to it in innocence--not because it’s so reliant on anything as gauche as surprise, but because it is so thoroughly excellent that wading through a movie review first would be like letting your dinner grow cold. And, it simply deserves our support.

When I saw PELICAN BLOOD last year at Fantastic Fest, it became one of my favorite movies before it was even over. I might admit that this was sort of a match made in heaven, as this movie checks almost every one of my personal boxes, but I don’t think my assessment of its value is a simple matter of personal prejudice. I’ve been haunted by it all these months, and deeply worried that somehow I might never see it again. When I discovered that it had landed on Nightstream, I was over the moon.

This is writer-director Katrin Gebbe's second feature, a fact that will astonish you when you see it. Last Blogtober, I wrote about her first feature TORE TANZT, which has the troubling english title NOTHING BAD CAN HAPPEN. That intense indie drama concerns a born-again christian punk who wishes for an opportunity to prove his devotion to god, and finds it in the form of a family that invites him in off the streets, and then proceeds to torture him. That's an oversimplification of what actually occurs, but it is a film that's hard to be brief about. It's cheap and a little rough around the edges, but it is deliberate, intense, and difficult to forget. (In fact it's supposed to be based on a true story, although I haven't managed to pick up that trail) When I first saw it, it certainly made me wonder what else that director might be up to, and I was astounded when I found out. 2019's PELICAN BLOOD emerged six years after TORE TANZT, with little in between besides a television episode and a segment in the anthology THE FIELD GUIDE TO EVIL, and yet Gebbe's artistic evolution is dumbfounding. Her themes are all unmistakably present--faith versus doubt, mystical versus metaphorical experience, and physical martyrdom--but exploded into a grand, elegant psychodrama that holds the viewer captive every minute of its two hours.

Celebrated german actress Nina Hoss plays Wiebke, a stable owner who trains police horses to tolerate the frightening conditions of a riot. She lives at the edge of her pasture, raising her tween daughter Nicolina (Adelia-Constance Giovanni Ocleppo) on her own. Wiebke has a talent for healing the wounded, or perhaps it's more of a calling; she raised Nicolina, a bulgarian orphan, into a bright, balanced, emotionally available tomboy, and the two of them joyfully anticipate the arrival of Nicolina's new adoptive sister. When little Raya arrives (Katerina Lipovska), she first presents as sweet, even solicitous, needing only a mother's love to fully bloom. However, as soon as she determines that she is welcome and wanted, she undergoes a disturbing transformation into a violent and unpredictable creature, possessed by an abject hatred. Wiebke recognizes that her new child is seriously traumatized, which activates her sense of purpose, and she pledges herself fully to the child's recovery--despite the admonishments of Raya's daycare, her doctors, and virtually everyone around them, that the little girl is beyond all but clinical help, and even that promises no guarantee of salvation. Refusing to give up, Wiebke makes a series of increasingly dangerous personal sacrifices in Raya's name, until finally she finds herself at the doorway to what some consider another world, but what is to others only madness.

Gebbe won Best Director in the main competition at Fantastic Fest, and it would have been a crime if this were otherwise. Her control over what are essentially forces of nature is humbling. Extracting a profoundly moving drama from a cast of adult actors is challenging enough on its own, but to get these terrifyingly convincing performances from children, evoking deep trauma and physical violence to self and others, is another level. As if this weren't enough, Gebbe adds animals into the mix, giving the story of Raya a parallel in the troubled career of a police horse who is considered a lost cause by all but Wiebke. The training scenes in which Wiebke guides the volatile animal through fire and smoke, while her own lifeforce is being progressively depleted by her new child, are as harrowing as anything having to do with parenthood, and Wiebke seems to take the horse just as seriously as her child. Friendly single dad Benedikt (Murathan Muslu) tries to flirt with the trainer by remarking on her unusual career, but she spits bitterly, "The horses are not the problem," giving us a glimpse of the philosophy that drives her.

Another of my favorite german films is Werner Herzog's 1976 short NO ONE WILL PLAY WITH ME. This funny and poignant story involves a bullied and neglected little boy, and it is preceded by a card displaying the adage "There are no bad children, only bad parents." This is the principle that drives Wiebke in work and life: Those who are seen as failures, have been failed by others. One has the sense that Wiebke sees herself in these wretches. She has no partner, and balks at questions about her relationship history, shying from physical affection even with people she knows and likes. A tell-tale scar graces one cheekbone; when she finally begins to welcome the benign Benedikt's advances, he strokes it instead of kissing her, acknowledging that he can see who she really is.

Wiebke tries to extend this same empathy toward Raya, refusing to let the child bait her into wrath and rejection. However, this show of pure faith and tolerance does not work, and the right approach becomes less clear as Raya begins to blame her mounting acts of vandalism, arson and assault on an evil entity that controls her will. A psychiatrist aprises Wiebke that this is the "magic period", in which the child uses magical thinking to divert feelings of guilt and responsibility. But, after a fashion, Wiebke begins to sense this malevolent presence as well. Is this etheric intrusion real? Or is she beginning to empathize with the child--with the experience of grappling with a damaged part of yourself--to the point of dissolving boundaries?

The title of the movie refers to a fable about a pelican whose chicks die, and she resurrects them by feeding them her own blood. This is a clear metaphor for Wiebke's trial with Raya, that becomes shockingly literal when, after endangering her home and relationships by prioritizing the new child, Wiebke places her own health on the line by taking an unregulated drug to give herself a bizarre advantage. When Wiebke discovers the shocking nature of Raya's original trauma, she experiments with the radical idea of treating the girl like a little baby, hoping to start from square one with her capacity to be mothered, and in the service of this dreadful proposition, Wiebke starts taking a lactation-inducing pill that proves to be an immediate risk to her health, and puts her in an even more perilous position with Raya.

Although it focuses on a preternaturally devoted mother, PELICAN BLOOD recalls what makes movies like HEREDITARY and WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN so potent. We have the idea that in becoming parents, we are perpetuating our own essence, extending our history and celebrating the precious connection of blood, which is supposed to impart an automatic same-ness. Unfortunately, this only shakes out to arrogance for many, denying the quirks of psychology, chemistry, and the unique impact of trauma--even if minor, or explainable as something benign--on a mind too young to fully comprehend the nature of the experience. Even without abuse in the home, anyone can have a child less like themselves than they could have ever imagined, for reasons beyond their own control. In all this, the child is innocent, and it is the duty of the parent to prioritize the child's feelings, over the vanity of wanting an heir to your own best qualities. Wiebke sacrifices not only her vanity, but potentially her very life, to show Raya love. When this blood sacrifice does not work, Wiebke finds herself facing the realm of alternative belief as a last resort.

The introduction of PELICAN BLOOD's folk horror element can seem a little left field, if you haven't noted the clues scattered throughout the film. Before the revelation of Raya's boogeyman, Wiebke begins to discover evidence of an old pagan tradition still being practiced around her proverbial neck of the woods. Soon, she tentatively entrusts herself and her child to a local witch, who puts them through a harrowing exorcism. Though the process is uncertain at first, its impact forces Wiebke into a direct acknowledgment of the entity harassing her daughter. And ultimately, it awakens in Raya a capacity for love.

While the reality of the supernatural in PELICAN BLOOD remains in question, I think the effect of this ambiguity is specifically meaningful. I usually scoff at any type of "was it all a dream?" nonsense, as this is a tactic employed by directors who think their greatest accomplishment should be getting one over on the audience. I don't see any inherent value in simply reversing the apparent meaning of things, just to make people feel stupid--and worse, this has trained modern audiences to try to defensively predict the least likely ending to any story, instead of just engaging with it emotionally as it plays out. For this reality-bending trick to be worth anything, one must be able to answer questions like, IF this was all a dream, THEN what meaning is added to the story?

In PELICAN BLOOD, the unresolved question of whether magic is real is of great relevance to the whole concept of belief. Human beings crave extranormal experience; we're deeply attracted to tales of ghosts, UFOs, mythical creatures, and parapsychological abilities. Even the skeptics among us enjoy arguing about these things, and many regular folks without eccentric interests read their horoscope "just for fun". Most telling of all is the enduring popularity of stories about the strange and unusual, which require no particular belief system from the audience; the fantasy of this extra dimension to our mundane lives is just so satisfying. Despite all the pleasure we get from these ideas, though, we tend to cling first and foremost to objective truth; we tell ourselves that if there is no "proof", then an outrageous thing cannot exist. But, this is actually contrary to many of our lived experiences. On the basest level, we delight at videos of insane parkour stunts, at the same time that we say these guys are "like" superheroes, but are actually just guys. My question is, what's the difference? If a person can achieve physical feats that most of us can never imagine attempting, then what difference does it make that this person was not bitten by a radioactive spider? If a fortune teller in a carnival is so good at "cold reading" strangers that she gives the effect of being able to read minds, then what is the appreciable difference between a carny and a "real psychic"? If a faith healer "just convinces" someone to become free from a chronic ailment, and the patient goes on to live a happier life, who cares if no "real magic" was in evidence? What is the difference between exorcism and hypnosis, if the end result is the same for a seriously disturbed child and her mother? The only difference appears to be some material confirmation of specific mystical forces and substances--which, admittedly, would be exciting on its own--but this would still only be an alternative version of the events that led up to the same "miraculous" result. We only worry about the existence of God and magic because our definitions of these things tend to be limited to what we think of as literal and scientific. But, if the correct effects manifest themselves, then all that is purely cosmetic. Belief is real. Faith works.

#blogtober#2020#pelican blood#pelican blood 2020#katrin gebbe#nina hoss#Adelia-Constance Giovanni Ocleppo#Murathan Muslu#Katerina Lipovska#drama#folk horror#witch#witchcraft#exorcism#possession

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

the thing about carrie white doing nothing wrong reminds me of a conversation i had last week about sansa stark in which a grown ass man said "she should've learned her lesson a lot faster, if it weren't for her actions most of her family would still be alive" and i got super mad bc from both a doylist and a watsonian perspective u absolutely cannot expect that from her. the same goes for carrie; she's a pubescent girl being traumatized and abused and we have to assume that she's doing her best

I do not know anything at all about sansa stark so I cannot pose arguments there but I agree that carrie can’t be interpreted in a watsonian matter because everyone in that book is lying or horrible or carrie, and carrie has such a warped perception of the world & an absolutely skewed beyond belief sense of morality that there’s no way we could ever expect her to narrate honestly or in a way that we will understand from the way she described it ... like she’s a very angry girl and she frequently resorts to violence or menacing but that’s because her mother is angry and violent and menacing and the only way carrie’s been able to survive is by threatening her right back and it makes sense she’d want to hurt people who hurt her, because when she upsets her mother, her mother hurts her. so when you look at it as a person who is outside the story and you know what physical abuse and emotional abuse at the hands of a parent and torment at the hands of one’s peers can do to an already fragile and alienated child it feels like the only thing you can say is “carrie white did nothing wrong” which is basically the short way of saying “carrie white was a victim of a mother who hated her and a world that didn’t care about her and while the solution to these problems is never murdering your classmates via telekinesis, when we look at the life carrie had and the ceaseless torment she faced and the way her mother handled problems, it makes sense she would try to stop her suffering by punishing those who had inflicted it upon her” and like Bill Hader Voice ooooh she snapped!!! however it’s a gray area because murder is always wrong obviously but carrie’s life was horrible and her brain was a mess because of it and even though she’s painted as one of the villains in a story with no apparent heroes, she as a character should be examined with empathy, because you’re never going to understand someone that Hurt without approaching them in a sympathetic manner and it also helps to acknowledge she was written by a man and placed in a story that had always doomed her to fail

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, yeah, if you consider "Anything society does in response to anti-social behavior" a "punishment" then the idea of non-punitive justice will sound like an oxymoron, but I think that's a bizarre definition of punishment.

Recently, I was at a birthday party for my niece, and the kids were playing with rubber balls. One of them , about three or four years old, threw a ball at me and it hit me in the face and hurt.

I said something along the lines of, "Hey, hey. That really hurt. I know you weren't trying to hurt me and I'm not angry but you need to be really careful not to hit people with these, ok?"

And he stopped throwing them around and we played a different game and I didn't get hurt again.

Would you consider that to be "punishing" the child?

I mean, you can use the term however you want, but another option that a lot of parents in the past might have taken when faced with the same behavior would resort to spanking the child.

The idea, I should think, of non-punitive justice is to distinguish between an attempt to modify behavior by, say, making a child aware of why we want them to change their behavior, and attempts to modify behavior through the fear that we will inflict pain on the child if the behavior continues.

Now, I'm not all in on Prison Abolition, but it seems to me that the fact that prisons are meant to be cruel is, in fact, a major issue. They are rife with violence and arbitrary cruelty in large part because the people running them want them to be filled with violence and arbitrary cruelty.

Like, if their purpose is simply to isolate violent people from the means to commit violence (removing them from tools to commit violence and victims to inflict it on) then we still have a number of choices to make. How much non-physical contact with the outside world should they be given? How easy should it be to put people in solitary confinement? How much access to reading material, video games, puzzles or other distractions should those in solitary confinement be allowed access to?

Answers to questions like that are going to vary massively based on whether your goal is to eliminate the possibility of certain anti-social behaviors or whether your goal is to make prison as uncomfortable as possible for inmates.

If you have no idea which goal you're pursuing, then your policy will be hopelessly confused and you'll constantly undermine yourself, which is where the US criminal justice system finds itself today.

One of the reasons (though not the only reason) prisons don't work as places of monastic self-reflection is that people don't want them to work that way!

To allow prisoners actual safe and quiet space to reflect would be "soft on crime". People think that people who do bad things should have bad things happen to them, so they create policies to make things worse for Prisoners even when that directly leads to more recidivism.

Whenever I see people saying “justice should be restorative and not punitive” I get a little itch in my brain about it.

Because in the main I agree.

But then I think about, like, Ahmaud Arbery’s family, and feel like never punishing would send a message just like punishing does, and it’d be something like, “yes, white men, you can gang up on black men and kill them. We care, but like… not very much, actually.”

It seems… maybe not ideal, but better, at least, that the family and the country know you get punished for shit like that.

Which seems wrong. It seems like sometimes we have to firmly express “actually no, you don’t just ge5 away with doing thst.”

Which makes the whole debate funny to me because you could avoid so much of this woth, “most of the time, justice should be restorative. In these sorts of cases though, sometimes the best you can do is tell someone their life is tough now because they did a thing everyone ELSE recognizes as wrong and the6 don’t.”

Like, free everyone in jail for weed yesterday. But for racist murder? I’m… not sure. I want t9 go “woo prison abolition” but the fact tha5 there are a lot of people like this around gives me serious pause.

157 notes

·

View notes