#eulogiums

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Eulogiums.]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ryuichi Sakamoto /28.Mar 2023 -eulogium.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Queen was the ornament of the clergy, the dew for the poor, the pillar of the Church, the graciousness for the dignitaries, the tender protector of citizens, the mother of the poor, the escape for the paupers, the defender of orphans, the anchor for the weak, the protector of all her subjects” — Stanisław of Skalbmierz in his eulogium

Jadwiga of Poland died 17th July 1399 from complications following her daughter's birth.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the years after 1402 the certainty that Richard was alive and well in Scotland seemed less tenacious than the desire that it be so. Perhaps the last people actually to believe Richard alive were those duped Welsh volunteers who showed up for muster prior to the Battle of Shrewsbury wearing the livery of Ricardian white harts; according to the Eulogium continuator, Henry Percy was so exasperated with their credulousness that he paused to give them a short lecture on political reality, identifying himself as the central actor, the one who had thrown out Richard and who now, finding Henry worse, wanted to throw him out, too. Once the Welsh volunteers removed their emblems, people seem to have found a way, while not exactly believing, to let their desires do their believing for them and, desiring Richard, to behave "as if" they believed. It was, after all, the populace's desire for Richard that caught the attention of the Eulogium continuator and other commentators of the day. Of course, kings are always the objects of such desires. They create themselves as kings by stirring and promising to fulfill those desires, and — as Louise Fradenburg has observed — the king's absence may actually abet, rather than hinder, this imaginative process: "Distance, absence … is not necessarily … a liability for a king. The sovereign is created as distant, and the distance allows him to be desired in a particular way, as ideal, as disembodied…. Thus sovereignty promises a fantastic, a perfect but imaginary, closure to the very yearning it brings into being." This very circuit of imaginary closure is suggested in a 1402 letter addressed to Richard by his steadfast admirer Creton. Creton, firsthand observer of the events of 1399 and now valet de chambre of Charles VI of France, writes tentatively but hopefully to the absent sovereign in Scotland, saying he has heard that Richard still lives and that he prays it is so. He adds that of those who speak of the matter or hear it spoken, the great majority cannot believe him dead. He describes his own obsessive return to an image of Richard: ". . . I do not know how it is that the representation of your image comes to me so often before the eyes of my heart, for by day and by night all my mental imaginings have no other object than you". Creton is fully aware of his own creative role in the production of Richard's image. Provoked by Richard's absence and his own desire, he en- gages in "thoughtful imaginings" — a phrase that Robert Clark, who has assisted me with this passage, considers to embrace both "the thought process and its product." The result is not just an image but a double removal — the representation of an image, which Creton sees with the eyes of his thought ]. He realizes that he solaces himself with "fausses" rather than "vraies" joys: "ainsy medelictent les fausses joies puisque les vraies je ne puis avoir." His joys are false because of the role of imagination in their production; Richard's figure —whether taken to mean his countenance or his entire being — is brought before the eyes of his thought by the force of his desire. As it happens, Creton spent time with Richard in the last year of his reign and could bolster his imagination with his own recollections. But even if he had never seen Richard, he would still have had access to the separable and immortal symbolic body of his absent king. Richard's image might be said to assume its plasticity at a point of conjuncture, between the imaginary and the symbolic — between Creton's desire-driven thought-work, on the one hand, and an enlarged repertoire of past and potential royal symbolizations, on the other. Richard's physical absence facilitates this process, by enabling a direct circuit between the subject (as source) and the king (as object) of desire.

Paul Strohm, "The Trouble with Richard: The Reburial of Richard II and Lancastrian Symbolic Strategy", Speculum, Vol. 71, No. 1 (1996)

#THIS. ARTICLE.#richard ii#henry hotspur percy#jean creton#the trouble with richard#historian: paul strohm

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

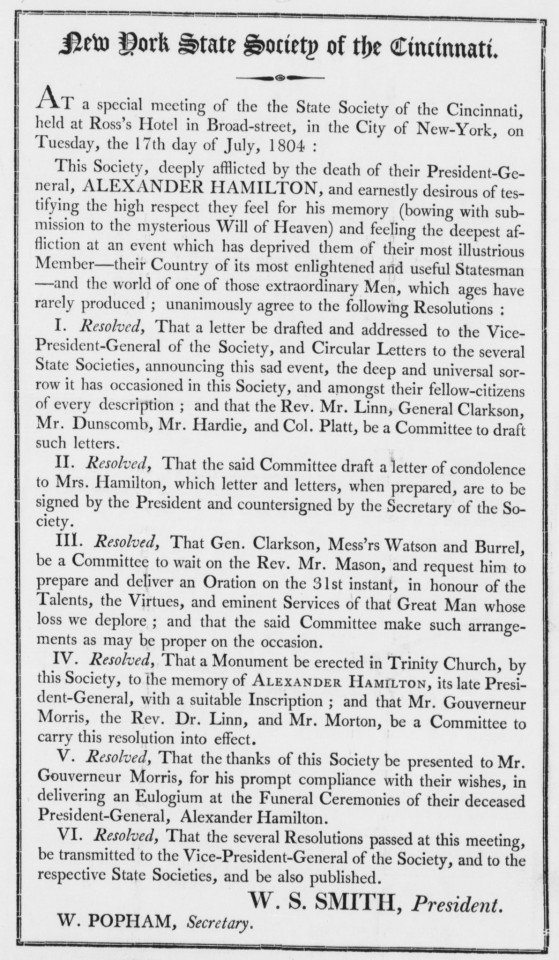

New York State Society of the Cincinnati, on the death of Alexander Hamilton

At a special meeting of the the State Society of the Cincinnati, held at Ross's Hotel in Broad-street, in the City of New-York, on Tuesday, the 17th day of July, 1804: This Society, deeply afflicted by the death of their President-General, ALEXANDER HAMILTON, and earnestly desirous of testifying the high respect they feel for his memory (bowing with submission to the mysterious Will of Heaven) and feeling the deepest affliction at an event which has deprived them of their most illustrious Member—their Country of its most enlightened and useful Statesman—and the world of one of those extraordinary Men, which ages have rarely produced; unanimously agree to the following Resolutions: I. Resolved, That a letter be drafted and addressed to the Vice-President-General of the Society, and Circular Letters to the several State Societies, announcing this sad event, the deep and universal sorrow it has occasioned in this Society, and amongst their fellow-citizens of every description; and that the Rev. Mr. Linn, General Clarkson, Mr. Dunscomb, Mr. Hardie, and Col. Platt, be a Committee to draft such letters. II. Resolved, That the said Committee draft a letter of condolence to Mrs. Hamilton, which letter and letters, when prepared, are to be signed by the President and countersigned by the Secretary of the Society. III. Resolved, That Gen. Clarkson, Mess'rs Watson and Burrel, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Mr. Mason, and request him to prepare and deliver an Oration on the 31st instant, in honour of the Talents, the Virtues, and eminent Services of that Great Man whose loss we deplore; and that the said Committee make such arrangements as may be proper on the occasion. IV. Resolved, That a Monument be erected in Trinity Church, by this Society, to the memory of Alexander Hamilton, its late President-General, with a suitable Inscription; and that Mr. Gouverneur Morris, the Rev. Dr. Linn, and Mr. Morton, be a Committee to carry this resolution into effect. V. Resolved, That the thanks of this Society be presented to Mr. Gouverneur Morris, for his prompt compliance with their wishes, in delivering an Eulogium at the Funeral Ceremonies of their deceased President-General, Alexander Hamilton. VI. Resolved, That the several Resolutions passed at this meeting, be transmitted to the Vice-President-General of the Society, and to the respective State Societies, and be also published. W. S. SMITH, President.

W. POPHAM, Secretary.

Source — Library of Congress, Digital Collections, manuscript/mixed material. Image 8 of Alexander Hamilton Papers: Family Papers, 1737-1917; 1804-1805

The New York State Society of Cincinnati - also known as The Society of the Cincinnati - is a fraternal hereditary society founded on June 9, 1783, to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. In order to perpetuate their fellowship, the founders made membership hereditary. [x] The Society has had three goals; “To preserve the rights so dearly won; to promote the continuing union of the states; and to assist members in need, their widows, and their orphans.” To achieve these aims, the Society called on its members to contribute a month's pay. George Washington was the first president general of the Society. The army's chief of artillery, Henry Knox, was the chief author of the Institution.

The organization was named after, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a farmer who left his farm to serve as a Roman Consul and Magister Populi (With temporary powers similar to that of a modern-era dictator). In response to a military emergency, he took over the city of Rome as a legitimate dictator. After the conflict, he gave the Senate back the initiative and resumed cultivating his fields. This philosophy of unselfish service is reflected in the Society's motto; He gave up everything to keep the Republic alive, or Omnia reliquit servare rempublicam.

The Society of the Cincinnati was founded by officers at the Continental Army encampment at Newburgh, like Major General Henry Knox. The first meeting of the Society was held in the May of 1783 at a dinner at the Verplanck House Fishkill, New York, (Which was Baron Von Steuben's headquarters during the Revolution) before the British evacuation from New York City. The meeting was presided over by Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, with Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton serving as the orator. The participants agreed to stay in contact with each other after the war. Mount Gulian is considered the birthplace of the Society of the Cincinnati, where the Institution was formally adopted on May 13, 1783. To this day the members of the organization meet annually at the Verplanck homestead. It is modernly known as The Mount Gulian historic site and looks very much as it did in 1783. There you will find the Cincinnati Gallery, dedicated to the New York State Society, with displays, artifacts, and documents illustrating the founding and activities of the Society during its continuous existence since 1783. Read more here.

While the NYSSOTC did erect the famous white monument on top of the grave of Hamilton, [x] in 1957 they erected another monument in Financial District in Manhattan in New York County engraved with; “To the Memory of Alexander Hamilton 1757 - 1804. Lieutenant Colonel, Aide de Camp to Gen. Washington And Those Other Officers of the Continental Army & Navy Original Members of the Society Whose Remains are Interred in the Churchyards of Trinity Parish” [x]

#amrev#american history#alexander hamilton#historical alexander hamilton#new york state society of the cincinnati#baron von steuben#henry knox#george washington#history#cicero's history lessons#friedrich wilhelm von steuben

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

She was the daughter of a Jewish family named Negri, born at Saronno, near Milan, in the year 1798. The records of her childhood are slight, and beyond the fact that she received her first musical lessons at the Cathedral of Como and her latter training at the Milan Conservatory, and that she essayed her feeble wings at secondrate Italian theatres in subordinate parts for the first year, there is but little of significance to relate. In 1816 she sang in the train of the haughty and peerless Catalani at the Favart in Paris, but did not succeed in attracting attention. But it happened that Ayrton, of the King's Theatre, London, heard her sing at the house of Paer, the composer, and liked her well enough to engage herself and husband at a moderate salary. When Pasta's glimmering little light first shone in London, Fodor and Camporese were in the full blaze of their reputation—both brilliant singers, but destined to pale into insignificance afterward before the intense splendor of Pasta's perfected genius. One of the notices of the opening performance at the King's Theatre, when Mme. Camporese sang the leading role of Cimarosa's " Penelope," followed up a lavish eulogium on the prima donna with the contemptuous remark, " Two subordinate singers named Pasta and Mari came forward in the characters of Telamuco and Arsinoe, but their musical talent does not require minute delineation." There is every reason to believe that Pasta was openly flouted both by the critics and the members of her own profession during her first London experience, but a magnificent revenge was in store for her. Among the parts she sang at this chrysalis period were Gherubino in the " Nozze di Figaro," Servilia in " La Clemenza di Tito," and the role of the pretended shrew in Ferrari's " II Sbaglio Fortunato." Mme. Pasta found herself at the end of the season a dire failure. But she had the searching self-insight which stamps the highest forms of genius, and she determined to correct her faults, and develop her great but latent powers.

Suddenly she disappeared from the view of the operatic world, and buried herself in a retired Italian city, where she studied with intelligent and tirelesszeal under M. Scappa, a maestro noted for his power of kindling the material of genius. Occasionally she tested herself in public. An English nobleman who heard her casually at this time said : " Other singers find themselves endowed with a voice and leave everything to chance. This woman leaves nothing to chance, and her success is therefore certain." She subjected herselfto a course of severe and incessant study to subdue her voice. To equalize it was impossible. There was a portion of the scale which differed from the rest in quality, and remained to the last " under a veil," to use the Italian term. Some of her notes were always out of time, especially at the beginning of a performance, until the vocalizing machinery became warmed and mellowed by passion and excitement. Out of these uncouth and rebellious materials she had to compose her instrument, and then to give it flexibility. Chorley, in speaking of these difficulties, says : " The volubility and brilliancy, when acquired, gained a character of their own from the resisting peculiarities of her organ. There were a breadth, an expressiveness in her roulades, an evenness and solidity in her shake, which imparted to every passage a significance beyond the reach of more spontaneous singers." But, after all, the true secret of her greatness was in the intellect and imagination which lay behind the voice, and made every tone quiver with dramatic sensibility.

The lyric Siddons of her age was now on the verge of making her real debut. When she reappeared in Venice, in 1819, she made a great impression, which was strengthened by her subsequent performances in Rome, Milan, and Trieste, during that and the following year. The fastidious Parisians recognized her power in the autumn of 1821, when she sang at the Theatre Italien ; and at Verona, during the Congress of 1822, she was received with tremendous enthusiasm. She returned to Paris the same year, and in the opera of " Romeo e Giulietta " she exhibited such power, both in singing and acting, as to call from the French critics the most extravagant terms of praise. Mme. Pasta was then laying the foundation of one of the most dazzling reputations ever gained by prima donna. By sheer industry she had extended the range of her voice to two octaves and a half—from A above the bass clef note to C flat, and even to D in alt. Her tones had become rich and sweet, except when she attempted to force them beyond their limits ; her intonation was, however, never quite perfect, being occasionally a little flat. Her singing was pure and totally divested of all spurious finery ; she added little to what was set down by the composer, and that little was not only in good taste, but had a great deal of originality to recommend it. She possessed deep feeling and correct judgment. Her shake was most beautiful ; Signor Pacini's well-known cavatina, " II soave e bel contento"— the peculiar feature of which consisted in the solidity and power of a sudden shake, contrasted with the detached staccato of the first bar —was written for Mme. Pasta. Some of her notes were sharp almost to harshness, but this defect with the greatness of genius she overcame, and even converted into a beauty ; for in passages of profound passion her guttural tones were thrilling. The irregularity of her lower notes, governed thus by a perfect taste and musical tact, aided to a great extent in giving that depth of expression which was one of the principal charms of her singing ; indeed, these lower tones were peculiarly suited for the utterance of vehement passion, producing an extraordinary effect by the splendid and unexpected contrast which they enabled her to give to the sweetness of the upper tones, causing a kind of musical discordance indescribably pathetic and melancholy. Her accents were so plaintive, so penetrating, so profoundly tragical, that no one could resist their influence.

Her genius as a tragedienne surpassed her talent as a singer. When on the stage she was no longer Pasta, but Tancredi, Romeo, Desdemona, Medea, or Semiramide. Ebers tells us in his " Seven Years of the King's Theatre " : " Nothing could have been more free from trick or affectation than Pasta's performance. There is no perceptible effort to resemble a character she plays ; on the contrary, she enters the stage the character itself ; transposed into the situation, excited by the hopes and fears, breathing the life and spirit of the being she represents." Mme. Pasta was a slow reader, but she had in perfection the sense for the measurement and proportion of time, a most essential musical quality. This gave her an instinctive feeling for propriety, which no lessons could teach; that due recognition of accent and phrase, that absence of flurry and exaggeration, such as makes the discourse and behavior of some people memorable, apart from the value of matter and occasion ; that intelligent composure, without coldness, which impresses and reassures those who see and hear. A quotation from a distinguished critic already cited gives a vivid idea of Pasta's influence on the most cold and fastidious judges : " The greatest grace of all, depth and reality of expression, was possessed by this remarkable artist as few (I suspect) before her—as none whom I have since admired—have possessed it. The best of her audience were held in thrall, without being able to analyze what made up the spell, what produced the effect, so soon as she opened her lips. Her recitative, from the moment she entered, was riveting by its truth. People accustomed to object to the conventionalities of opera (just as loudly as if all drama was not conventional too), forgave the singing and the strange language for the sake of the direct and dignified appeal made by her declamation.

Mme. Pasta never changed her readings, her effects, her ornaments. What was to her true, when once arrived at, remained true for ever. To arrive at what stood with her for truth, she labored, made experiments, rejected with an elaborate care, the result of which, in one meaner or more meager, must have been monotony. But the inrpression made on me was that of being always subdued and surprised for the first time. Though I knew what was coming, when the passion broke out, or when the phrase was sung, it seemed as if they were something new, electrical, immediate. The effect to me is at present, in the moment of writing, as the impression made by the first sight of the sea, by the first snow mountain, by any of those first emotions which never entirely pass away. These things are utterly different from the fanaticism of a laudator tenporis acti"

When Talma heard her declaim, at the time of her earliest celebrity in Paris, he said : " Here is a woman of whom I can still learn. One turn of her beautiful head, one glance of her eye, one light motion of her hand, is, with her, sufficient to express a passion. She can raise the soul of the spectator to the highest pitch of astonishment and delight by one tone of her voice. * O Dio !'as it comes from her breast, swelling over her lips, is of indescribable effect." Poetical and enthusiastic by temperament, the crowning excellence of her art was a grand simplicity. There was a sublimity in her expressions of vehement passion which was the result of measured force, energy which was never wasted, exalted pathos that never overshot the limits of art. Vigorous without violence, graceful without artifice, she was always greatest when the greatest emergency taxed her powers.

Pasta's second great part at the Theatre Italien was in Rossini's " Tancredi," an impersonation which was one of the most enchanting and finished, of her lighter roles. " She looked resplendent in the casque and cuirass of the Red Cross, Knight. No one could ever sing the part of Tancredi like Mme. Pasta : her pure taste enabled her to add grace to the original composition by elegant and irreproachable ornaments. ' Di tanti palpiti ' had been first presented to the Parisians by Mme. Fodor, who covered it with rich and brilliant embroidery, and gave it what an English critic, Lord Mount Edgcumbe, afterward termed its countrydance-like character. Mme. Pasta, on the contrary, infused into this air its true color and expression, and the effect was ravishing."

" Tancredi " was quickly followed by " Otello," and the impassioned spirit, energy, delicacy, and tenderness with which Pasta infused the character of Desdemona furnished the theme for the most avish praises on the part of the critics. It was especially in the last act that her acting electrified her audiences. Her transition from hope to terror, from supplication to scorn, culminating in the vehement outburst " sono innocente" her last frenzied looks, when, blinded by her disheveled hair and bewildered with her conflicting emotions, she seems to seek fruitlessly the means of flight, were awful. The varied resources of the great art of tragedy were consummately drawn forth by her Desdemona, in this opera, though she was yet toastonish the world with that impersonation imperishably linked with her name in the history of art. " Elisabetta " and " Mose in Egitto " were also revived for her, and she filled the leading characters in both with eclat.

In January, 1824, Mme. Pasta gave to the world what by all concurrent accounts must have been the grandest lyric impersonation in the records of art, the character of Medea in Simon Maver's opera. This masterpiece was composed musically and dramatically by the artist herself on the weak foundation of a wretched play and correct but commonplace music. In a more literal and truthful sense than that in which the term is so often travestied by operatic singers, the part was created by Pasta, reconstructed in form and meaning, as well as inspired by a matchless executive genius. In the language of one writer, whose enthusiasm seems not to have been excessive: " It was a triumph of histrionic art, and afforded every opportunity for the display of all the resources of her genius—the varied powers which had been called forth and combined in Medea, the passionate tenderness of Romeo, the spirit and animation of Tancredi, the majesty of Semiramide, the mournful beauty of Nina, the dignity and sweetness of Desdemona. It is difficult to conceive a character more highly dramatic or more intensely impassioned than that of fedea; and in the successive scenes Pasta appeared as if torn by the conflict of contending passions, until at last her anguish rose to sublimity. The conflict of human affection and supernatural power, the tenderness of the wife, the agonies of the mother, and the rage of the woman scorned, were portrayed with a truth, a power, a grandeur of effect unequaled before or since by any actress or singer. Every attitude, each movement and look, became a study for a painter ; for in the storm of furious passion the grace and beauty of her gestures were never marred by extravagance. Indeed,her impersonation of Medea was one of the finest illustrations of classic grandeur the stage has ever presented. In the scene where Medea murders her children, the acting of Pasta rose to the sublime. Her self-abandonment, her horror at the contemplation of the deed she is about to perpetrate, the irrepressible affection which comes welling up in her breast, were pictured with a magnificent power, yet with such natural pathos, that the agony of the distracted mother was never lost sight of in the fury of the priestess. Folding her arms across her bosom, she contracted her form, as, cowering, she shrunk from the approach of her children ; then grief, love, despair, rage, madness, alternately wrung her heart, until at last her soul seemed appalled at the crime she contemplated. Starting forward, she pursued the innocent creatures, while the audience involuntarily closed their eyes and recoiled before the harrowing spectacle, which almost elicited a stifled cry of horror. But her fine genius invested the character with that classic dignity and beauty which, as in the Niobe group, veils the excess of human agony in the drapery of ideal art."

In 1824 Pasta made her first English appearance at the King's Theatre, at which was engaged an extraordinary assemblage of talent, Mesdames Colbran-Rossini, Catalani, Ronzi di Begnis, Vestris, Caradori, and Pasta. The great tragedienne made her first appearance in Desdemona, and, as all Europe was ringing with her fame, the curiosity to see and hear her was almost unparalleled. Long before the beginning of the opera the house was packed with an intensely expectant throng. For an English audience, idolizing the memory of Shakespeare, even Rossini's fine music, conducted by that great composer himself, could hardly under ordinary circumstances condone the insult offered to a species of literary religion by the wretched stuff pitchforked together and called a libretto. But the genius of Pasta made them forget even this, and London bowed at her feet with as devout a recognition as that offered by the more fickle Parisians. Her chaste and noble style, untortured by meretricious ornament, excited the deepest admiration. Count Stendhal, the biographer of Rossini, seems to have heard her for the first time at London, and writes of her in the following fashion:" Moderate in the use of embellishments, Mme. Pasta never employs them but to heighten the force of the expression ; and, what is more, her embellishments last only just so long as they are found to be useful." In this respect her manner formed a very strong contrast with that of the generality of Italian singers at the time, who were more desirous of creating astonishment than of giving pleasure. It was not from any lack of technical knowledge and vocal skill that Mme. Pasta avoided extravagant ornamentation, for in many of the concerted pieces—in which she chiefly shone—her execution united clearness and rapidity. "Mme. Pasta is certainly less exuberant in point of ornament, and more expressive in point of majesty and simplicity," observed one critic, " than any of the first-class singers who have visited England for a long period. . . . She is also a mistress of art," continues the same writer, " and, being limited by nature, she makes no extravagant use of her powers, but employs them with the tact and judgment that can proceed only from an extraordinary mind. This constitutes her highest praise ; for never did intellect and industry become such perfect substitutes for organic superiority. Notwithstanding her fine vein of imagination and the beauty of her execution, she cultivates high and deep passions, and is never so great as in the adaptation of art to the purest purposes of expression."

We can not better close this sketch than by giving an account of one of the very last public appearances of her life, when she allowed herself to be seduced into giving a concert in London for the benefit of the Italian cause. Mme. Pasta had long since dismissed all the belongings of the stage, and her voice, which at its best had required ceaseless watching and study, had been given up by her. Even her person had lost all that stately dignity and queenliness which had made her stage appearance so remarkable. It was altogether a painful and disastrous occasion.There were artists present who then for the first time were to get their impression of a great singer, prepared of course to believe that that reputation had been exaggerated. Among these was Rachel, who sat enjoying the humiliation of decayed grandeur with a cynical and bitter sneer on her face, drawing the attention of the theatre by her exhibition of satirical malevolence.

Malibran's great sister, Mme. Pauline Viardot, was also present, watching with the quick, sympathetic response of a noble heart every turn of the singer's voice and action. Hoarse, broken, and destroyed as was the voice, her grand style spoke to the sensibilities of the great artist. The opera was "Anna Bolena," and from time to time the old spirit and fire burned in her tones and gestures. In the final mad scene Pasta rallied into something like her former grandeur of acting ; and in the last song with its roulades and its scales of shakes ascending by a semitone, this consummate vocalist and tragedienne, able to combine form with meaning—dramatic grasp and insight with such musical display as enter into the lyric art—was indicated at least to the apprehension of the younger artist. "You are right ! " was Mme. Viardot's quick and heartfelt response to a friend by her side, while her eyes streamed with tears—" you are right. It is like the ' Cenacolo ' of Leonardo da Vinci at Milan, a wreck of a picture, but the picture is the greatest picture in the world."

From Great singers by Ferris, George T. (George Titus)

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Giuditta Pasta#mezzo-soprano#soprano#soprano sfogato#classical musician#clasical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Prima donna assoluta

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The funeral of the leading Reformation preacher John Knox took place on November 26th 1572.

I was busy on Friday so missed a few posts, the main one being the death of John Knox on the 24th.

Surprisingly there is not any great detail of the occasion, but I suppose that is the way he probably would have liked it, the movement he headed decried anything ostentatious regarding religion. So I have dug deep looking for anything on it and found a few wee pieces.......

From Thomas M’Cree's the “Life of John Knox” (p. 277):

“On Wednesday, the 26th of November, he (knox) was interred in the church-yard of St. Giles. His funeral was attended by the newly-elected regent, Morton, by all the nobility who were in the city, and a great concourse of people.”

1. M. Hetherington in his History of the Church of Scotland on pg 77 continues the story of his burial when he wrote:

“When he (Knox) was lowered into the grave, and gazing thoughtfully into the open sepulcher, the regent emphatically pronounced his eulogium in these words, ‘There lies he who never feared the face of man.'”

Regent Morton knew himself the truthfulness of these final words as John Knox had reproved him to his face, with Hetherington calling the regent later on in his history “that bold bad man.” (p. 77)

Knox's grave lies in the car park to the south of what is commonly known as St. Giles Cathedral the number 23 painted on it, with a blank yellow stone at its head. Beside that yellow stone that can be found a small plaque enclosed in 9 bricks with the following message, “The above stone marks the approximate site of the burial in St. Giles graveyard of John Knox the great Scottish divine who died on 24 November 1572.”

Back then of course it wasn't a car park, the original smaller Kirk, like the vast majority of churches, had at that time a burial ground, who knows how many bodies lie under the car park, and indeed surrounding buildings, the place having been a place of worship for over 600 years before he was interred there.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw that paragon of manly perfections in London: he seemed scarcely to merit the eulogiums of his mother and sister

i really do love how biting helen's narration can get lol

#'that paragon of manly perfections' just OOZING sarcasm#laura talks books#bronte blogging#the tenant of wildfell hall#wildfell weekly

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meanwhile these were the first that had fallen, and Pericles, son of Xanthippus, was chosen to pronounce their eulogium. When the proper time arrived, he advanced from the sepulchre to an elevated platform in order to be heard by as many of the crowd as possible, and spoke as follows: "Most of my predecessors in this place have commended him who made this speech part of the law, telling us that it is well that it should be delivered at the burial of those who fall in battle. For myself, I should have thought that the worth which had displayed itself in deeds, would be sufficiently rewarded by honours also shown by deeds; such as you now see in this funeral prepared at the people's cost. And I could have wished that the reputations of many brave men were not to be imperilled in the mouth of a single individual, to stand or fall according as he spoke well or ill. For it is hard to speak properly upon a subject where it is even difficult to convince your hearers that you are speaking the truth. On the one hand, the friend who is familiar with every fact of the story, may think that some point has not been set forth with that fullness which he wishes and knows it to deserve; on the other, he who is a stranger to the matter may be led by envy to suspect exaggeration if he hears anything above his own nature. For men can endure to hear others praised only so long as they can severally persuade themselves of their own ability to equal the actions recounted: when this point is passed, envy comes in and with it incredulity. However, since our ancestors have stamped this custom with their approval, it becomes my duty to obey the law and to try to satisfy your several wishes and opinions as best I may.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

0 notes

Text

There is sometimes in the manner in which a eulogium is given, in the voice, in the affectionate tone, a poison so sweet, that the strongest mind is intoxicated by it.

The Vicomte of Bragelonne by Alexandre Dumas

#the vicomte of bragelonne#alexandre dumas#quotes#literature#books#classics#classic literature#book quotes#french literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eulogium

1 note

·

View note

Text

SARCASM #sarcasm #synonym #ingles #gibe #chaff #irony #jeer #satire #antonym #eulogy #compliment #panegyric #eulogium #portugues #sarcasmo #gibe #joio #ironia #zombaria #sátira #ridículo

SARCASM #sarcasm #synonym #ingles #gibe #chaff #irony #jeer #satire #antonym #eulogy #compliment #panegyric #eulogium #portugues #sarcasmo #gibe #joio #ironia #zombaria #sátira #ridículo

Inglês: Sarcasm Synonyms Gibe, chaff, irony, jeer, satire, ridicule, taunt, sardonicism. Antonyms Eulogy, compliment, panegyric, eulogium. Português: Sarcasmo Gibe, joio, ironia, zombaria, sátira, ridículo, provocação, sarconicismo Thank you for visiting us! Obrigado pela visita!

View On WordPress

#antonym#chaff#Compliment#eulogium#eulogy#gibe#irony#jeer#panegyric#ridicule;#sarcasm#sardonicism#satire#synonym#Taunt

0 notes

Text

Angelica Church to Elizabeth Hamilton, London, [January 25, 1794]

London, January 25th, 1794.

When my Dear Eliza, when am I to receive a letter from you? When am I to hear that you are in perfect health, and that you are no longer in fear for the life of your dear Hamilton?

For my part, now that the fever is gone, I am all alive to the apprehensions of the war. One sorrow succeeds another. It has been whispered to me that my friend Alexander means to quit his employment of Secretary. The country will lose one of her best friends, and you, my Dear Eliza, will be the only person to whom this change can be either necessary or agreeable. I am inclined to believe that it is your influence induces him to withdraw from public life. That so good a wife, so tender a mother, should be so bad a patriot! is wonderful!

You will probably have heard that Robert Morris is married, but I hope you will contradict the report as he assures me there is no truth in it…

We are making many preparations to return to America. Mr. Church loses no opportunity to place his property in the American fund; and if we can dispose of the rest our Landed Estate you would soon my dear Eliza embrace your Sister.

Catharine and Betsey have just finished their Italian lesson—I pass my time with these dear girls and see with rapture their progress. Why did you not send Angelica with Mr. Lear; a year or two would have been useful to her and have delighted my children.… Mr. Fox and Lord Wycomb have each made an eulogium on General Washington in which truth and Elegance are happily blended… I feel myself all the better when I have my countrymen praised… and when I say my Brother Mr. Hamilton my eyes sparkle that you see my dear Eliza that your Husband’s form very much improves your sister’s looks: for myself then let him continue to serve his country.

Adieu my dear Eliza. Embrace all the children and tell Philip that he is not to forget his cousin Eliza, she is very pretty and very good.

My Love to dear Hamilton, if Papa is with you tell him how much I love him.

Yours affectionately

Church desires his love and promises obedience to your command. He declares the American wives are agreeable tyrants.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tagged by @justapalspal for a get to know you tag game!

Favorite time of year: Autumn! I love sweater weather and fall colors 💕💕💕 winter is great too, I like cozying up inside when it's snowing and having soup and hot drinks

Comfort foods: Gumbo, spaghetti and meatballs, and curry!

Do you collect anything: everyone here has seen the bakura hoard skfnskfnd but I also collect leatherbound and special edition books! The crown jewel of my collection is the Easton Press edition of The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. I am also an enamel pin FIEND

Favorite drink: I like ginger and orange tea and lemonade!

Favorite musical artists: I have entirely too many, but my top faves are Black Hill, Estatic Fear, Malice Mizer, Linkin Park and Hozier

Current favorite songs: Krwlng, Circles out of Salt and Red Sky - Black Blood

Favorite fics: okay my first answer has to be a non ygo one: Go Not Gently by Guardian1 is literally my favorite piece of literature ever written. If you're a FF9 fan I cannot recommend it enough.

For ygo, Impasse and Eulogium by @im-not-a-monster made me BAWL. I also absolutely love @melffy-puppy 's Puzzle System!

I tag @ectoplasmer, @im-not-a-monster, @melffy-puppy, @facets-and-rainbows and @zorckura, only if you want to!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare was true to his chronicle sources in portraying Henry Percy as one determined to live in the real world, to avoid self-deluding interpretations. The Eulogium continuator gives us a Percy who delivered a lecture on realpolitik to the followers of the late King Richard who showed up on the eve of Shrewsbury still wearing his livery: ‘He caused it to be proclaimed that he was one of those who had striven greatly for the expulsion of Richard and the introduction of Henry, believing himself to have done well. And because now he knew that Henry was a worse ruler than Richard, he therefore intended to correct his error.” Yet even Percy is elsewhere returned to prophecy’s shifty dominion. The Annales Henrici draw upon a well-established anecdotal frame when they have him, learning before the battle of Shrewsbury that a nearby village was called Berwick, blanching and heaving a great sigh, and saying to a servant, I know indeed that my plow has reached its last furrow; for I have heard through prophecy [‘per fatidicum’] .. . that I should undoubtedly die in Berwick. But I was deceived, alas, by confusion about the name [‘sed decepit me, proh dolor! nominis hujus aequivocum’].” The implication is that Percy had resolved to avoid Berwick upon Tweed! Here, though, another Berwick manifests itself, to his undoing and the greater prestige of prophecy. This story’s status as an obvious invention matters less than the habit of mind it reveals; a habit in which actions are, willy-nilly, subjected to prophecy’s dominion.

Paul Strohm, England’s Empty Throne: Usurpation and the Language of Legitimation, 1399-1422 (Yale University Press, 1998)

#henry hotspur percy#historian: paul strohm#i feel like those first lines give me a better idea of hotspur than the two biographies of him i've read

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

yo you were in my dream last night

i got this cool shirt cape/shirt that was inspired by gravekeeper and it turns out you made it? idk lol

should i take it as an eulogium that I'm in your subconcious enough time to consider me as a paid actor for your dream?

6 notes

·

View notes