#eucd article 6

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Antiusurpation and the road to disenshittification

THIS WEEKEND (November 8-10), I'll be in TUCSON, AZ: I'm the GUEST OF HONOR at the TUSCON SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTION.

Nineties kids had a good reason to be excited about the internet's promise of disintermediation: the gatekeepers who controlled our access to culture, politics, and opportunity were crooked as hell, and besides, they sucked.

For a second there, we really did get a lot of disintermediation, which created a big, weird, diverse pluralistic space for all kinds of voices, ideas, identities, hobbies, businesses and movements. Lots of these were either deeply objectionable or really stupid, or both, but there was also so much cool stuff on the old, good internet.

Then, after about ten seconds of sheer joy, we got all-new gatekeepers, who were at least as bad, and even more powerful, than the old ones. The net became Tom Eastman's "Five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of the other four." Culture, politics, finance, news, and especially power have been gathered into the hands of unaccountable, greedy, and often cruel intermediaries.

Oh, also, we had an election.

This isn't an election post. I have many thoughts about the election, but they're still these big, unformed blobs of anger, fear and sorrow. Experience teaches me that the only way to get past this is to just let all that bad stuff sit for a while and offgas its most noxious compounds, so that I can handle it safely and figure out what to do with it.

While I wait that out, I'm just getting the job done. Chop wood, carry water. I've got a book to write, Enshittification, for Farar, Straus, Giroux's MCD Books, and it's very nearly done:

https://twitter.com/search?q=from%3Adoctorow+%23dailywords&src=typed_query&f=live

Compartmentalizing my anxieties and plowing that energy into productive work isn't necessarily the healthiest coping strategy, but it's not the worst, either. It's how I wrote nine books during the covid lockdowns.

And sometimes, when you're not staring directly at something, you get past the tunnel vision that makes it impossible to see its edges, fracture lines, and weak points.

So I'm working on the book. It's a book about platforms, because enshittification is a phenomenon that is most visible and toxic on platforms. Platforms are intermediaries, who connect buyers and sellers, creators and audiences, workers and employers, politicians and voters, activists and crowds, as well as families, communities, and would-be romantic partners.

There's a reason we keep reinventing these intermediaries: they're useful. Like, it's technically possible for a writer to also be their own editor, printer, distributor, promoter and sales-force:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/19/crad-kilodney-was-an-outlier/#intermediation

But without middlemen, those are the only writers we'll get. The set of all writers who have something to say that I want to read is much larger than the set of all writers who are capable of running their own publishing operation.

The problem isn't middlemen: the problem is powerful middlemen. When an intermediary gets powerful enough to usurp the relationship between the parties on either side of the transaction, everything turns to shit:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/12/direct-the-problem-of-middlemen/

A dating service that faces pressure from competition, regulation, interoperability and a committed workforce will try as hard as it can to help you find Your Person. A dating service that buys up all its competitors, cows its workforce, captures its regulators and harnesses IP law to block interoperators will redesign its service so that you keep paying forever, and never find love:

https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2024/02/13/1228749143/the-dating-app-paradox-why-dating-apps-may-be-worse-than-ever

Multiply this a millionfold, in every sector of our complex, high-tech world where we necessarily rely on skilled intermediaries to handle technical aspects of our lives that we can't – or shouldn't – manage ourselves. That world is beholden to predators who screw us and screw us and screw us, jacking up our rents:

https://www.thebignewsletter.com/p/yes-there-are-antitrust-voters-in

Cranking up the price of food:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/04/dont-let-your-meat-loaf/#meaty-beaty-big-and-bouncy

And everything else:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/06/attention-rents/#consumer-welfare-queens

(Maybe this is a post about the election after all?)

The difference between a helpmeet and a parasite is power. If we want to enjoy the benefits of intermediaries without the risks, we need policies that keep middlemen weak. That's the opposite of the system we have now.

Take interoperability and IP law. Interoperability (basically, plugging new things into existing things) is a really powerful check against powerful middlemen. If you rely on an ad-exchange to fund your newsgathering and they start ripping you off, then an interoperable system that lets you use a different exchange will not only end the rip off – it'll make it less likely to happen in the first place because the ad-tech platform will be afraid of losing your business:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

Interoperability means that when a printer company gouges you on ink, you can buy cheap third party ink cartridges and escape their grasp forever:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/11/ink-stained-wretches-battle-soul-digital-freedom-taking-place-inside-your-printer

Interoperability means that when Amazon rips off audiobook authors to the tune of $100m, those authors can pull their books from Amazon and sell them elsewhere and know that their listeners can move their libraries over to a different app:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/07/audible-exclusive/#audiblegate

But interoperability has been in retreat for 40 years, as IP law has expanded to criminalize otherwise normal activities, so that middlemen can use IP rights to protect themselves from their end-users and business customers:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

That's what I mean when I say that "IP" is "any law that lets a business reach beyond its own walls and control the actions of its customers, competitors and critics."

For example, there's a pernicious law 1998 US law that I write about all the time, Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, the "anticircumvention law." This is a law that felonizes tampering with copyright locks, even if you are the creator of the undelying work.

So Amazon – the owner of the monopoly audiobook platform Audible – puts a mandatory copyright lock around every audiobook they sell. I, as an author who writes, finances and narrates the audiobook, can't provide you, my customer, with a tool to remove that lock. If I do so, I face criminal sanctions: a five year prison sentence and a $500,000 fine for a first offense:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/07/25/can-you-hear-me-now/#acx-ripoff

In other words: if I let you take my own copyrighted work out of Amazon's app, I commit a felony, with penalties that are far stiffer than the penalties you would face if you were to simply pirate that audiobook. The penalties for you shoplifting the audiobook on CD at a truck-stop are lower than the penalties the author and publisher of the book would face if they simply gave you a tool to de-Amazon the file. Indeed, even if you hijacked the truck that delivered the CDs, you'd probably be looking at a shorter sentence.

This is a law that is purpose-built to encourage intermediaries to usurp the relationship between buyers and sellers, creators and audiences. It's a charter for parasitism and predation.

But as bad as that is, there's another aspect of DMCA 1201 that's even worse: the exemptions process.

You might have read recently about the Copyright Office "freeing the McFlurry" by granting a DMCA 1201 exemption for companies that want to reverse-engineer the error-codes from McDonald's finicky, unreliable frozen custard machines:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/10/28/mcbroken/#my-milkshake-brings-all-the-lawyers-to-the-yard

Under DMCA 1201, the Copyright Office hears petitions for these exemptions every three years. If they judge that anticircumvention law is interfering with some legitimate activity, the statute empowers them to grant an exemption.

When the DMCA passed in 1998 (and when the US Trade Rep pressured other world governments into passing nearly identical laws in the decades that followed), this exemptions process was billed as a "pressure valve" that would prevent abuses of anticircumvention law.

But this was a cynical trick. The way the law is structured, the Copyright Office can only grant "use" exemptions, but not "tools" exemptions. So if you are granted the right to move Audible audiobooks into a third-party app, you are personally required to figure out how to do that. You have to dump the machine code of the Audible app, decompile it, scan it for vulnerabilities, and bootstrap your own jailbreaking program to take Audible wrapper off the file.

No one is allowed to help you with this. You aren't allowed to discuss any of this publicly, or share a tool that you make with anyone else. Doing any of this is a potential felony.

In other words, DMCA 1201 gives intermediaries power over you, but bans you from asking an intermediary to help you escape another abusive middleman.

This is the exact opposite of how intermediary law should work. We should have rules that ban intermediaries from exercising undue power over the parties they serve, and we should have rules empowering intermediaries to erode the advantage of powerful intermediaries.

The fact that the Copyright Office grants you an exemption to anticircumvention law means nothing unless you can delegate that right to an intermediary who can exercise it on your behalf.

A world without publishing intermediaries is one in which the only writers who thrive are the ones capable of being publishers, too, and that's a tiny fraction of all the writers with something to say.

A world without interoperability intermediaries is one in which the only platform users who thrive are also skilled reverse-engineering ninja hackers – and that's an infinitesimal fraction of the platform users who would benefit from interoperabilty.

Let this be your north star in evaluating platform regulation proposals. Platform regulation should weaken intermediaries' powers over their users, and strengthen their power over other middlemen.

Put in this light, it's easy to see why the ill-informed calls to abolish Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (which makes platform users, not platforms, responsible for most unlawful speech) are so misguided:

https://www.techdirt.com/2020/06/23/hello-youve-been-referred-here-because-youre-wrong-about-section-230-communications-decency-act/

If we require platforms to surveil all user speech and block anything that might violate any law, we give the largest, most powerful platforms a permanent advantage over smaller, better platforms, run by co-ops, hobbyists, nonprofits local governments, and startups. The big platforms have the capital to rig up massive, automated surveillance and censorship systems, and the only alternatives that can spring up have to be just as big and powerful as the Big Tech platforms we're so desperate to escape:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/23/evacuate-the-platforms/#let-the-platforms-burn

This is especially grave given the current political current, where fascist politicians are threatening platforms with brutal punishments for failing to censor disfavored political views.

Anyone who tells you that "it's only censorship when the government does it" is badly confused. It's only a First Amendment violation when the government does it, sure – but censorship has always relied on intermediaries. From the Inquisition to the Comics Code, government censors were only able to do their jobs because powerful middlemen, fearing state punishments, blocked anything that might cross the line, censoring far beyond the material actually prohibited by the law:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/22/self-censorship/#hugos

We live in a world of powerful, corrupt middlemen. From payments to real-estate, from job-search to romance, there's a legion of parasites masquerading as helpmeets, burying their greedy mouthparts into our tender flesh:

https://www.capitalisnt.com/episodes/visas-hidden-tax-on-americans

But intermediaries aren't the problem. You shouldn't have to stand up your own payment processor, or learn the ins and outs of real-estate law, or start your own single's bar. The problem is power, not intermediation.

As we set out to build a new, good internet (with a lot less help from the US government than seemed likely as recently as last week), let's remember that lesson: the point isn't disintermediation, it's weak intermediation.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/11/07/usurpers-helpmeets/#disreintermediation

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en (Image: Cryteria, CC BY 3.0, modified)

#pluralistic#comcom#competitive compatibility#interoperability#interop#adversarial interoperability#intermediaries#enshittification#posting through it#compartmentalization#farrar straus giroux#intermediary liability#intermediary empowerment#delegation#delegatability#dmca 1201#1201#digital millennium copyright act#norway#article 6#eucd#european union copyright act#eucd article 6#eu#usurpers#crad kilodney#fiduciaries#disintermediation#dark corners#self-censorship

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

I liked a @YouTube video http://bit.ly/2PL2mkJ How Article 13 Could Ruin The Internet And Why You Should Care About The EUCD...

I liked a @YouTube video https://t.co/fujnZ3xnhp How Article 13 Could Ruin The Internet And Why You Should Care About The EUCD...

— Darren Lock (@darren_lock) September 6, 2018

from Twitter https://twitter.com/darren_lock September 06, 2018 at 01:52PM via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

EFF says it's resigning from W3C after the standards org voted for browser DRM, a move hostile to archiving, accessibility, security research, more (Cory Doctorow/Electronic Frontier ...)

Dear Jeff, Tim, and colleagues,

In 2013, EFF was disappointed to learn that the W3C had taken on the project of standardizing “Encrypted Media Extensions,” an API whose sole function was to provide a first-class role for DRM within the Web browser ecosystem. By doing so, the organization offered the use of its patent pool, its staff support, and its moral authority to the idea that browsers can and should be designed to cede control over key aspects from users to remote parties.

When it became clear, following our formal objection, that the W3C's largest corporate members and leadership were wedded to this project despite strong discontent from within the W3C membership and staff, their most important partners, and other supporters of the open Web, we proposed a compromise. We agreed to stand down regarding the EME standard, provided that the W3C extend its existing IPR policies to deter members from using DRM laws in connection with the EME (such as Section 1201 of the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act or European national implementations of Article 6 of the EUCD) except in combination with another cause of action.

This covenant would allow the W3C's large corporate members to enforce their copyrights. Indeed, it kept intact every legal right to which entertainment companies, DRM vendors, and their business partners can otherwise lay claim. The compromise merely restricted their ability to use the W3C's DRM to shut down legitimate activities, like research and modifications, that required circumvention of DRM. It would signal to the world that the W3C wanted to make a difference in how DRM was enforced: that it would use its authority to draw a line between the acceptability of DRM as an optional technology, as opposed to an excuse to undermine legitimate research and innovation.

More directly, such a covenant would have helped protect the key stakeholders, present and future, who both depend on the openness of the Web, and who actively work to protect its safety and universality. It would offer some legal clarity for those who bypass DRM to engage in security research to find defects that would endanger billions of web users; or who automate the creation of enhanced, accessible video for people with disabilities; or who archive the Web for posterity. It would help protect new market entrants intent on creating competitive, innovative products, unimagined by the vendors locking down web video.

Despite the support of W3C members from many sectors, the leadership of the W3C rejected this compromise. The W3C leadership countered with proposals — like the chartering of a nonbinding discussion group on the policy questions that was not scheduled to report in until long after the EME ship had sailed — that would have still left researchers, governments, archives, security experts unprotected.

The W3C is a body that ostensibly operates on consensus. Nevertheless, as the coalition in support of a DRM compromise grew and grew — and the large corporate members continued to reject any meaningful compromise — the W3C leadership persisted in treating EME as topic that could be decided by one side of the debate. In essence, a core of EME proponents was able to impose its will on the Consortium, over the wishes of a sizeable group of objectors — and every person who uses the web. The Director decided to personally override every single objection raised by the members, articulating several benefits that EME offered over the DRM that HTML5 had made impossible.

But those very benefits (such as improvements to accessibility and privacy) depend on the public being able to exercise rights they lose under DRM law — which meant that without the compromise the Director was overriding, none of those benefits could be realized, either. That rejection prompted the first appeal against the Director in W3C history.

In our campaigning on this issue, we have spoken to many, many members' representatives who privately confided their belief that the EME was a terrible idea (generally they used stronger language) and their sincere desire that their employer wasn't on the wrong side of this issue. This is unsurprising. You have to search long and hard to find an independent technologist who believes that DRM is possible, let alone a good idea. Yet, somewhere along the way, the business values of those outside the web got important enough, and the values of technologists who built it got disposable enough, that even the wise elders who make our standards voted for something they know to be a fool's errand.

We believe they will regret that choice. Today, the W3C bequeaths an legally unauditable attack-surface to browsers used by billions of people. They give media companies the power to sue or intimidate away those who might re-purpose video for people with disabilities. They side against the archivists who are scrambling to preserve the public record of our era. The W3C process has been abused by companies that made their fortunes by upsetting the established order, and now, thanks to EME, they’ll be able to ensure no one ever subjects them to the same innovative pressures.

So we'll keep fighting to fight to keep the web free and open. We'll keep suing the US government to overturn the laws that make DRM so toxic, and we'll keep bringing that fight to the world's legislatures that are being misled by the US Trade Representative to instigate local equivalents to America's legal mistakes.

We will renew our work to battle the media companies that fail to adapt videos for accessibility purposes, even though the W3C squandered the perfect moment to exact a promise to protect those who are doing that work for them.

We will defend those who are put in harm's way for blowing the whistle on defects in EME implementations.

It is a tragedy that we will be doing that without our friends at the W3C, and with the world believing that the pioneers and creators of the web no longer care about these matters.

Effective today, EFF is resigning from the W3C.

Thank you,

Cory Doctorow Advisory Committee Representative to the W3C for the Electronic Frontier Foundation

from Techmeme http://ift.tt/2ffUhrH

0 notes

Text

An open letter to the W3C Director, CEO, team and membership

Dear Jeff, Tim, and colleagues,

In 2013, EFF was disappointed to learn that the W3C had taken on the project of standardizing “Encrypted Media Extensions,” an API whose sole function was to provide a first-class role for DRM within the Web browser ecosystem. By doing so, the organization offered the use of its patent pool, its staff support, and its moral authority to the idea that browsers can and should be designed to cede control over key aspects from users to remote parties.

When it became clear, following our formal objection, that the W3C's largest corporate members and leadership were wedded to this project despite strong discontent from within the W3C membership and staff, their most important partners, and other supporters of the open Web, we proposed a compromise. We agreed to stand down regarding the EME standard, provided that the W3C extend its existing IPR policies to deter members from using DRM laws in connection with the EME (such as Section 1201 of the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act or European national implementations of Article 6 of the EUCD) except in combination with another cause of action.

This covenant would allow the W3C's large corporate members to enforce their copyrights. Indeed, it kept intact every legal right to which entertainment companies, DRM vendors, and their business partners can otherwise lay claim. The compromise merely restricted their ability to use the W3C's DRM to shut down legitimate activities, like research and modifications, that required circumvention of DRM. It would signal to the world that the W3C wanted to make a difference in how DRM was enforced: that it would use its authority to draw a line between the acceptability of DRM as an optional technology, as opposed to an excuse to undermine legitimate research and innovation.

More directly, such a covenant would have helped protect the key stakeholders, present and future, who both depend on the openness of the Web, and who actively work to protect its safety and universality. It would offer some legal clarity for those who bypass DRM to engage in security research to find defects that would endanger billions of web users; or who automate the creation of enhanced, accessible video for people with disabilities; or who archive the Web for posterity. It would help protect new market entrants intent on creating competitive, innovative products, unimagined by the vendors locking down web video.

Despite the support of W3C members from many sectors, the leadership of the W3C rejected this compromise. The W3C leadership countered with proposals — like the chartering of a nonbinding discussion group on the policy questions that was not scheduled to report in until long after the EME ship had sailed — that would have still left researchers, governments, archives, security experts unprotected.

The W3C is a body that ostensibly operates on consensus. Nevertheless, as the coalition in support of a DRM compromise grew and grew — and the large corporate members continued to reject any meaningful compromise — the W3C leadership persisted in treating EME as topic that could be decided by one side of the debate. In essence, a core of EME proponents was able to impose its will on the Consortium, over the wishes of a sizeable group of objectors — and every person who uses the web. The Director decided to personally override every single objection raised by the members, articulating several benefits that EME offered over the DRM that HTML5 had made impossible.

But those very benefits (such as improvements to accessibility and privacy) depend on the public being able to exercise rights they lose under DRM law — which meant that without the compromise the Director was overriding, none of those benefits could be realized, either. That rejection prompted the first appeal against the Director in W3C history.

In our campaigning on this issue, we have spoken to many, many members' representatives who privately confided their belief that the EME was a terrible idea (generally they used stronger language) and their sincere desire that their employer wasn't on the wrong side of this issue. This is unsurprising. You have to search long and hard to find an independent technologist who believes that DRM is possible, let alone a good idea. Yet, somewhere along the way, the business values of those outside the web got important enough, and the values of technologists who built it got disposable enough, that even the wise elders who make our standards voted for something they know to be a fool's errand.

We believe they will regret that choice. Today, the W3C bequeaths an legally unauditable attack-surface to browsers used by billions of people. They give media companies the power to sue or intimidate away those who might re-purpose video for people with disabilities. They side against the archivists who are scrambling to preserve the public record of our era. The W3C process has been abused by companies that made their fortunes by upsetting the established order, and now, thanks to EME, they’ll be able to ensure no one ever subjects them to the same innovative pressures.

So we'll keep fighting to fight to keep the web free and open. We'll keep suing the US government to overturn the laws that make DRM so toxic, and we'll keep bringing that fight to the world's legislatures that are being misled by the US Trade Representative to instigate local equivalents to America's legal mistakes.

We will renew our work to battle the media companies that fail to adapt videos for accessibility purposes, even though the W3C squandered the perfect moment to exact a promise to protect those who are doing that work for them.

We will defend those who are put in harm's way for blowing the whistle on defects in EME implementations.

It is a tragedy that we will be doing that without our friends at the W3C, and with the world believing that the pioneers and creators of the web no longer care about these matters.

Effective today, EFF is resigning from the W3C.

Thank you,

Cory Doctorow Advisory Committee Representative to the W3C for the Electronic Frontier Foundation

from Deeplinks http://ift.tt/2xd8hXK

0 notes

Text

“If buying isn’t owning, piracy isn’t stealing”

20 years ago, I got in a (friendly) public spat with Chris Anderson, who was then the editor in chief of Wired. I'd publicly noted my disappointment with glowing Wired reviews of DRM-encumbered digital devices, prompting Anderson to call me unrealistic for expecting the magazine to condemn gadgets for their DRM:

https://longtail.typepad.com/the_long_tail/2004/12/is_drm_evil.html

I replied in public, telling him that he'd misunderstood. This wasn't an issue of ideological purity – it was about good reviewing practice. Wired was telling readers to buy a product because it had features x, y and z, but at any time in the future, without warning, without recourse, the vendor could switch off any of those features:

https://memex.craphound.com/2004/12/29/cory-responds-to-wired-editor-on-drm/

I proposed that all Wired endorsements for DRM-encumbered products should come with this disclaimer:

WARNING: THIS DEVICE’S FEATURES ARE SUBJECT TO REVOCATION WITHOUT NOTICE, ACCORDING TO TERMS SET OUT IN SECRET NEGOTIATIONS. YOUR INVESTMENT IS CONTINGENT ON THE GOODWILL OF THE WORLD’S MOST PARANOID, TECHNOPHOBIC ENTERTAINMENT EXECS. THIS DEVICE AND DEVICES LIKE IT ARE TYPICALLY USED TO CHARGE YOU FOR THINGS YOU USED TO GET FOR FREE — BE SURE TO FACTOR IN THE PRICE OF BUYING ALL YOUR MEDIA OVER AND OVER AGAIN. AT NO TIME IN HISTORY HAS ANY ENTERTAINMENT COMPANY GOTTEN A SWEET DEAL LIKE THIS FROM THE ELECTRONICS PEOPLE, BUT THIS TIME THEY’RE GETTING A TOTAL WALK. HERE, PUT THIS IN YOUR MOUTH, IT’LL MUFFLE YOUR WHIMPERS.

Wired didn't take me up on this suggestion.

But I was right. The ability to change features, prices, and availability of things you've already paid for is a powerful temptation to corporations. Inkjet printers were always a sleazy business, but once these printers got directly connected to the internet, companies like HP started pushing out "security updates" that modified your printer to make it reject the third-party ink you'd paid for:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/11/ink-stained-wretches-battle-soul-digital-freedom-taking-place-inside-your-printer

Now, this scam wouldn't work if you could just put things back the way they were before the "update," which is where the DRM comes in. A thicket of IP laws make reverse-engineering DRM-encumbered products into a felony. Combine always-on network access with indiscriminate criminalization of user modification, and the enshittification will follow, as surely as night follows day.

This is the root of all the right to repair shenanigans. Sure, companies withhold access to diagnostic codes and parts, but codes can be extracted and parts can be cloned. The real teeth in blocking repair comes from the law, not the tech. The company that makes McDonald's wildly unreliable McFlurry machines makes a fortune charging franchisees to fix these eternally broken appliances. When a third party threatened this racket by reverse-engineering the DRM that blocked independent repair, they got buried in legal threats:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/20/euthanize-rentier-enablers/#cold-war

Everybody loves this racket. In Poland, a team of security researchers at the OhMyHack conference just presented their teardown of the anti-repair features in NEWAG Impuls locomotives. NEWAG boobytrapped their trains to try and detect if they've been independently serviced, and to respond to any unauthorized repairs by bricking themselves:

https://mamot.fr/@[email protected]/111528162905209453

Poland is part of the EU, meaning that they are required to uphold the provisions of the 2001 EU Copyright Directive, including Article 6, which bans this kind of reverse-engineering. The researchers are planning to present their work again at the Chaos Communications Congress in Hamburg this month – Germany is also a party to the EUCD. The threat to researchers from presenting this work is real – but so is the threat to conferences that host them:

https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/researchers-face-legal-threats-over-sdmi-hack/

20 years ago, Chris Anderson told me that it was unrealistic to expect tech companies to refuse demands for DRM from the entertainment companies whose media they hoped to play. My argument – then and now – was that any tech company that sells you a gadget that can have its features revoked is defrauding you. You're paying for x, y and z – and if they are contractually required to remove x and y on demand, they are selling you something that you can't rely on, without making that clear to you.

But it's worse than that. When a tech company designs a device for remote, irreversible, nonconsensual downgrades, they invite both external and internal parties to demand those downgrades. Like Pavel Chekov says, a phaser on the bridge in Act I is going to go off by Act III. Selling a product that can be remotely, irreversibly, nonconsensually downgraded inevitably results in the worst person at the product-planning meeting proposing to do so. The fact that there are no penalties for doing so makes it impossible for the better people in that meeting to win the ensuing argument, leading to the moral injury of seeing a product you care about reduced to a pile of shit:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/25/moral-injury/#enshittification

But even if everyone at that table is a swell egg who wouldn't dream of enshittifying the product, the existence of a remote, irreversible, nonconsensual downgrade feature makes the product vulnerable to external actors who will demand that it be used. Back in 2022, Adobe informed its customers that it had lost its deal to include Pantone colors in Photoshop, Illustrator and other "software as a service" packages. As a result, users would now have to start paying a monthly fee to see their own, completed images. Fail to pay the fee and all the Pantone-coded pixels in your artwork would just show up as black:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/28/fade-to-black/#trust-the-process

Adobe blamed this on Pantone, and there was lots of speculation about what had happened. Had Pantone jacked up its price to Adobe, so Adobe passed the price on to its users in the hopes of embarrassing Pantone? Who knows? Who can know? That's the point: you invested in Photoshop, you spent money and time creating images with it, but you have no way to know whether or how you'll be able to access those images in the future. Those terms can change at any time, and if you don't like it, you can go fuck yourself.

These companies are all run by CEOs who got their MBAs at Darth Vader University, where the first lesson is "I have altered the deal, pray I don't alter it further." Adobe chose to design its software so it would be vulnerable to this kind of demand, and then its customers paid for that choice. Sure, Pantone are dicks, but this is Adobe's fault. They stuck a KICK ME sign to your back, and Pantone obliged.

This keeps happening and it's gonna keep happening. Last week, Playstation owners who'd bought (or "bought") Warner TV shows got messages telling them that Warner had walked away from its deal to sell videos through the Playstation store, and so all the videos they'd paid for were going to be deleted forever. They wouldn't even get refunds (to be clear, refunds would also be bullshit – when I was a bookseller, I didn't get to break into your house and steal the books I'd sold you, not even if I left some cash on your kitchen table).

Sure, Warner is an unbelievably shitty company run by the single most guillotineable executive in all of Southern California, the loathsome David Zaslav, who oversaw the merger of Warner with Discovery. Zaslav is the creep who figured out that he could make more money cancelling completed movies and TV shows and taking a tax writeoff than he stood to make by releasing them:

https://aftermath.site/there-is-no-piracy-without-ownership

Imagine putting years of your life into making a program – showing up on set at 5AM and leaving your kids to get their own breakfast, performing stunts that could maim or kill you, working 16-hour days during the acute phase of the covid pandemic and driving home in the night, only to have this absolute turd of a man delete the program before anyone could see it, forever, to get a minor tax advantage. Talk about moral injury!

But without Sony's complicity in designing a remote, irreversible, nonconsensual downgrade feature into the Playstation, Zaslav's war on art and creative workers would be limited to material that hadn't been released yet. Thanks to Sony's awful choices, David Zaslav can break into your house, steal your movies – and he doesn't even have to leave a twenty on your kitchen table.

The point here – the point I made 20 years ago to Chris Anderson – is that this is the foreseeable, inevitable result of designing devices for remote, irreversible, nonconsensual downgrades. Anyone who was paying attention should have figured that out in the GW Bush administration. Anyone who does this today? Absolute flaming garbage.

Sure, Zaslav deserves to be staked out over an anthill and slathered in high-fructose corn syrup. But save the next anthill for the Sony exec who shipped a product that would let Zaslav come into your home and rob you. That piece of shit knew what they were doing and they did it anyway. Fuck them. Sideways. With a brick.

Meanwhile, the studios keep making the case for stealing movies rather than paying for them. As Tyler James Hill wrote: "If buying isn't owning, piracy isn't stealing":

https://bsky.app/profile/tylerjameshill.bsky.social/post/3kflw2lvam42n

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/12/08/playstationed/#tyler-james-hill

Image: Alan Levine (modified) https://pxhere.com/en/photo/218986

CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

#pluralistic#playstation#sony#copyright#copyfight#drm#monopoly#enshittification#batgirl#road runner#financiazation#the end of ownership#ip

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

The US Copyright Office frees the McFlurry

I'll be in TUCSON, AZ from November 8-10: I'm the GUEST OF HONOR at the TUSCON SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTION.

I have spent a quarter century obsessed with the weirdest corner of the weirdest section of the worst internet law on the US statute books: Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, the 1998 law that makes it a felony to help someone change how their own computer works so it serves them, rather than a distant corporation.

Under DMCA 1201, giving someone a tool to "bypass an access control for a copyrighted work" is a felony punishable by a 5-year prison sentence and a $500k fine – for a first offense. This law can refer to access controls for traditional copyrighted works, like movies. Under DMCA 1201, if you help someone with photosensitive epilepsy add a plug-in to the Netflix player in their browser that blocks strobing pictures that can trigger seizures, you're a felon:

https://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/public-html-media/2017Jul/0005.html

But software is a copyrighted work, and everything from printer cartridges to car-engine parts have software in them. If the manufacturer puts an "access control" on that software, they can send their customers (and competitors) to prison for passing around tools to help them fix their cars or use third-party ink.

Now, even though the DMCA is a copyright law (that's what the "C" in DMCA stands for, after all); and even though blocking video strobes, using third party ink, and fixing your car are not copyright violations, the DMCA can still send you to prison, for a long-ass time for doing these things, provided the manufacturer designs their product so that using it the way that suits you best involves getting around an "access control."

As you might expect, this is quite a tempting proposition for any manufacturer hoping to enshittify their products, because they know you can't legally disenshittify them. These access controls have metastasized into every kind of device imaginable.

Garage-door openers:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/09/lead-me-not-into-temptation/#chamberlain

Refrigerators:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/06/12/digital-feudalism/#filtergate

Dishwashers:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/03/cassette-rewinder/#disher-bob

Treadmills:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/06/22/vapescreen/#jane-get-me-off-this-crazy-thing

Tractors:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/23/reputation-laundry/#deere-john

Cars:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/28/edison-not-tesla/#demon-haunted-world

Printers:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/07/inky-wretches/#epson-salty

And even printer paper:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/16/unauthorized-paper/#dymo-550

DMCA 1201 is the brainchild of Bruce Lehmann, Bill Clinton's Copyright Czar, who was repeatedly warned that cancerous proliferation this was the foreseeable, inevitable outcome of his pet policy. As a sop to his critics, Lehman added a largely ornamental safety valve to his law, ordering the US Copyright Office to invite submissions every three years petitioning for "use exemptions" to the blanket ban on circumventing access-controls.

I call this "ornamental" because if the Copyright Office thinks that, say, it should be legal for you to bypass an access control to use third-party ink in your printer, or a third-party app store in your phone, all they can do under DMCA 1201 is grant you the right to use a circumvention tool. But they can't give you the right to acquire that tool.

I know that sounds confusing, but that's only because it's very, very stupid. How stupid? Well, in 2001, the US Trade Representative arm-twisted the EU into adopting its own version of this law (Article 6 of the EUCD), and in 2003, Norway added the law to its lawbooks. On the eve of that addition, I traveled to Oslo to debate the minister involved:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/28/clintons-ghost/#felony-contempt-of-business-model

The minister praised his law, explaining that it gave blind people the right to bypass access controls on ebooks so that they could feed them to screen readers, Braille printers, and other assistive tools. OK, I said, but how do they get the software that jailbreaks their ebooks so they can make use of this exemption? Am I allowed to give them that tool?

No, the minister said, you're not allowed to do that, that would be a crime.

Is the Norwegian government allowed to give them that tool? No. How about a blind rights advocacy group? No, not them either. A university computer science department? Nope. A commercial vendor? Certainly not.

No, the minister explained, under his law, a blind person would be expected to personally reverse engineer a program like Adobe E-Reader, in hopes of discovering a defect that they could exploit by writing a program to extract the ebook text.

Oh, I said. But if a blind person did manage to do this, could they supply that tool to other blind people?

Well, no, the minister said. Each and every blind person must personally – without any help from anyone else – figure out how to reverse-engineer the ebook program, and then individually author their own alternative reader program that worked with the text of their ebooks.

That is what is meant by a use exemption without a tools exemption. It's useless. A sick joke, even.

The US Copyright Office has been valiantly holding exemptions proceedings every three years since the start of this century, and they've granted many sensible exemptions, including ones to benefit people with disabilities, or to let you jailbreak your phone, or let media professors extract video clips from DVDs, and so on. Tens of thousands of person-hours have been flushed into this pointless exercise, generating a long list of things you are now technically allowed to do, but only if you are a reverse-engineering specialist type of computer programmer who can manage the process from beginning to end in total isolation and secrecy.

But there is one kind of use exception the Copyright Office can grant that is potentially game-changing: an exemption for decoding diagnostic codes.

You see, DMCA 1201 has been a critical weapon for the corporate anti-repair movement. By scrambling error codes in cars, tractors, appliances, insulin pumps, phones and other devices, manufacturers can wage war on independent repair, depriving third-party technicians of the diagnostic information they need to figure out how to fix your stuff and keep it going.

This is bad enough in normal times, but during the acute phase of the covid pandemic, hospitals found themselves unable to maintain their ventilators because of access controls. Nearly all ventilators come from a single med-tech monopolist, Medtronic, which charges hospitals hundreds of dollars to dispatch their own repair technicians to fix its products. But when covid ended nearly all travel, Medtronic could no longer provide on-site calls. Thankfully, an anonymous hacker started building homemade (illegal) circumvention devices to let hospital technicians fix the ventilators themselves, improvising housings for them from old clock radios, guitar pedals and whatever else was to hand, then mailing them anonymously to hospitals:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/07/10/flintstone-delano-roosevelt/#medtronic-again

Once a manufacturer monopolizes repair in this way, they can force you to use their official service depots, charging you as much as they'd like; requiring you to use their official, expensive replacement parts; and dictating when your gadget is "too broken to fix," forcing you to buy a new one. That's bad enough when we're talking about refusing to fix a phone so you buy a new one – but imagine having a spinal injury and relying on a $100,000 exoskeleton to get from place to place and prevent muscle wasting, clots, and other immobility-related conditions, only to have the manufacturer decide that the gadget is too old to fix and refusing to give you the technical assistance to replace a watch battery so that you can get around again:

https://www.theverge.com/2024/9/26/24255074/former-jockey-michael-straight-exoskeleton-repair-battery

When the US Copyright Office grants a use exemption for extracting diagnostic codes from a busted device, they empower repair advocates to put that gadget up on a workbench and torture it into giving up those codes. The codes can then be integrated into an unofficial diagnostic tool, one that can make sense of the scrambled, obfuscated error codes that a device sends when it breaks – without having to unscramble them. In other words, only the company that makes the diagnostic tool has to bypass an access control, but the people who use that tool later do not violate DMCA 1201.

This is all relevant this month because the US Copyright Office just released the latest batch of 1201 exemptions, and among them is the right to circumvent access controls "allowing for repair of retail-level food preparation equipment":

https://publicknowledge.org/public-knowledge-ifixit-free-the-mcflurry-win-copyright-office-dmca-exemption-for-ice-cream-machines/

While this covers all kinds of food prep gear, the exemption request – filed by Public Knowledge and Ifixit – was inspired by the bizarre war over the tragically fragile McFlurry machine. These machines – which extrude soft-serve frozen desserts – are notoriously failure-prone, with 5-16% of them broken at any given time. Taylor, the giant kitchen tech company that makes the machines, charges franchisees a fortune to repair them, producing a steady stream of profits for the company.

This sleazy business prompted some ice-cream hackers to found a startup called Kytch, a high-powered automation and diagnostic tool that was hugely popular with McDonald's franchisees (the gadget was partially designed by the legendary hardware hacker Andrew "bunnie" Huang!).

In response, Taylor played dirty, making a less-capable clone of the Kytch, trying to buy Kytch out, and teaming up with McDonald's corporate to bombard franchisees with legal scare-stories about the dangers of using a Kytch to keep their soft-serve flowing, thanks to DMCA 1201:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/20/euthanize-rentier-enablers/#cold-war

Kytch isn't the only beneficiary of the new exemption: all kinds of industrial kitchen equipment is covered. In upholding the Right to Repair, the Copyright Office overruled objections of some of its closest historical allies, the Entertainment Software Association, Motion Picture Association, and Recording Industry Association of America, who all sided with Taylor and McDonald's and opposed the exemption:

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2024/10/us-copyright-office-frees-the-mcflurry-allowing-repair-of-ice-cream-machines/

This is literally the only useful kind of DMCA 1201 exemption the Copyright Office can grant, and the fact that they granted it (along with a similar exemption for medical devices) is a welcome bright spot. But make no mistake, the fact that we finally found a narrow way in which DMCA 1201 can be made slightly less stupid does not redeem this outrageous law. It should still be repealed and condemned to the scrapheap of history.

Tor Books as just published two new, free LITTLE BROTHER stories: VIGILANT, about creepy surveillance in distance education; and SPILL, about oil pipelines and indigenous landback.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/10/28/mcbroken/#my-milkshake-brings-all-the-lawyers-to-the-yard

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#dmca 1201#dmca#digital millennium copyright act#anticircumvention#triennial hearings#mcflurry#right to repair#r2r#mcbroken#automotive#mass question 1#us copyright office#copyright office#copyright#paracopyright#copyfight#kytch#diagnostic codes#public knowledge

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

from under the cut:

On the other hand, no[w] that Trump has announced that the terms of US free trade deals are optional (for the US, at least), there's no reason not to delete Article 6 of the EUCD, and all the other laws that prevent European companies from jailbreaking iPhones and making their own App Stores (minus Apple's 30% commission), as well as ad-blockers for Facebook and Instagram's apps (which would zero out EU revenue for Meta), and, of course, jailbreaking tools for Xboxes, Teslas, and every make and model of every American car, so European companies could offer service, parts, apps, and add-ons for them.

There Were Always Enshittifiers

I'm on a 20+ city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in DC TONIGHT (Mar 4), and in RICHMOND TOMORROW (Mar 5). More tour dates here. Mail-order signed copies from LA's Diesel Books.

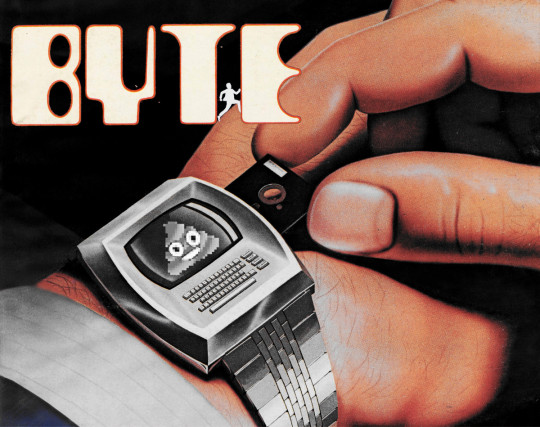

My latest Locus column is "There Were Always Enshittifiers." It's a history of personal computing and networked communications that traces the earliest days of the battle for computers as tools of liberation and computers as tools for surveillance, control and extraction:

https://locusmag.com/2025/03/commentary-cory-doctorow-there-were-always-enshittifiers/

The occasion for this piece is the publication of my latest Martin Hench novel, a standalone book set in the early 1980s called "Picks and Shovels":

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865908/picksandshovels

The MacGuffin of Picks and Shovels is a "weird PC" company called Fidelity Computing, owned by a Mormon bishop, a Catholic priest, and an orthodox rabbi. It sounds like the setup for a joke, but the punchline is deadly serious: Fidelity Computing is a pyramid selling cult that preys on the trust and fellowship of faith groups to sell the dreadful Fidelity 3000 PC and its ghastly peripherals.

You see, Fidelity's products are booby-trapped. It's not merely that they ship with programs whose data-files can't be read by apps on any other system – that's just table stakes. Fidelity's got a whole bag of tricks up its sleeve – for example, it deliberately damages a specific sector on every floppy disk it ships. The drivers for its floppy drive initialize any read or write operation by checking to see if that sector can be read. If it can, the computer refuses to recognize the disk. This lets the Reverend Sirs (as Fidelity's owners style themselves) run a racket where they sell these deliberately damaged floppies at a 500% markup, because regular floppies won't work on the systems they lure their parishioners into buying.

Or take the Fidelity printer: it's just a rebadged Okidata ML-80, the workhorse tractor feed printer that led the market for years. But before Fidelity ships this printer to its customers, they fit it with new tractor feed sprockets whose pins are slightly more widely spaced than the standard 0.5" holes on the paper you can buy in any stationery store. That way, Fidelity can force its customers to buy the custom paper that they exclusively peddle – again, at a massive markup.

Needless to say, printing with these wider sprocket holes causes frequent jams and puts a serious strain on the printer's motors, causing them to burn out at a high rate. That's great news – for Fidelity Computing. It means they get to sell you more overpriced paper so you can reprint the jobs ruined by jams, and they can also sell you their high-priced, exclusive repair services when your printer's motors quit.

Perhaps you're thinking, "OK, but I can just buy a normal Okidata printer and use regular, cheap paper, right?" Sorry, the Reverend Sirs are way ahead of you: they've reversed the pinouts on their printers' serial ports, and a normal printer won't be able to talk to your Fidelity 3000.

If all of this sounds familiar, it's because these are the paleolithic ancestors of today's high-tech lock-in scams, from HP's $10,000/gallon ink to Apple and Google's mobile app stores, which cream a 30% commission off of every dollar collected by an app maker. What's more, these ancient, weird misfeatures have their origins in the true history of computing, which was obsessed with making the elusive, copy-proof floppy disk.

This Quixotic enterprise got started in earnest with Bill Gates' notorious 1976 "open letter to hobbyists" in which the young Gates furiously scolds the community of early computer hackers for its scientific ethic of publishing, sharing and improving the code that they all wrote:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An_Open_Letter_to_Hobbyists

Gates had recently cloned the BASIC programming language for the popular Altair computer. For Gates, his act of copying was part of the legitimate progress of technology, while the copying of his colleagues, who duplicated Gates' Altair BASIC, was a shameless act of piracy, destined to destroy the nascent computing industry:

As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?

Needless to say, Gates didn't offer a royalty to John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz, the programmers who'd invented BASIC at Dartmouth College in 1963. For Gates – and his intellectual progeny – the formula was simple: "When I copy you, that's progress. When you copy me, that's piracy." Every pirate wants to be an admiral.

For would-be ex-pirate admirals, Gates's ideology was seductive. There was just one fly in the ointment: computers operate by copying. The only way a computer can run a program is to copy it into memory – just as the only way your phone can stream a video is to download it to its RAM ("streaming" is a consensus hallucination – every stream is a download, and it has to be, because the internet is a data-transmission network, not a cunning system of tubes and mirrors that can make a picture appear on your screen without transmitting the file that contains that image).

Gripped by this enshittificatory impulse, the computer industry threw itself headfirst into the project of creating copy-proof data, a project about as practical as making water that's not wet. That weird gimmick where Fidelity floppy disks were deliberately damaged at the factory so the OS could distinguish between its expensive disks and the generic ones you bought at the office supply place? It's a lightly fictionalized version of the copy-protection system deployed by Visicalc, a move that was later publicly repudiated by Visicalc co-founder Dan Bricklin, who lamented that it confounded his efforts to preserve his software on modern systems and recover the millions of data-files that Visicalc users created:

http://www.bricklin.com/robfuture.htm

The copy-protection industry ran on equal parts secrecy and overblown sales claims about its products' efficacy. As a result, much of the story of this doomed effort is lost to history. But back in 2017, a redditor called Vadermeer unearthed a key trove of documents from this era, in a Goodwill Outlet store in Seattle:

https://www.reddit.com/r/VintageApple/comments/5vjsow/found_internal_apple_memos_about_copy_protection/

Vaderrmeer find was a Apple Computer binder from 1979, documenting the company's doomed "Software Security from Apple's Friends and Enemies" (SSAFE) project, an effort to make a copy-proof floppy:

https://archive.org/details/AppleSSAFEProject

The SSAFE files are an incredible read. They consist of Apple's best engineers beavering away for days, cooking up a new copy-proof floppy, which they would then hand over to Apple co-founder and legendary hardware wizard Steve Wozniak. Wozniak would then promptly destroy the copy-protection system, usually in a matter of minutes or hours. Wozniak, of course, got the seed capital for Apple by defeating AT&T's security measures, building a "blue box" that let its user make toll-free calls and peddling it around the dorms at Berkeley:

https://512pixels.net/2018/03/woz-blue-box/

Woz has stated that without blue boxes, there would never have been an Apple. Today, Apple leads the charge to restrict how you use your devices, confining you to using its official app store so it can skim a 30% vig off every dollar you spend, and corralling you into using its expensive repair depots, who love to declare your device dead and force you to buy a new one. Every pirate wants to be an admiral!

https://www.vice.com/en/article/tim-cook-to-investors-people-bought-fewer-new-iphones-because-they-repaired-their-old-ones/

Revisiting the early PC years for Picks and Shovels isn't just an excuse to bust out some PC nostalgiacore set-dressing. Picks and Shovels isn't just a face-paced crime thriller: it's a reflection on the enshittificatory impulses that were present at the birth of the modern tech industry.

But there is a nostalgic streak in Picks and Shovels, of course, represented by the other weird PC company in the tale. Computing Freedom is a scrappy PC startup founded by three women who came up as sales managers for Fidelity, before their pangs of conscience caused them to repent of their sins in luring their co-religionists into the Reverend Sirs' trap.

These women – an orthodox lesbian whose family disowned her, a nun who left her order after discovering the liberation theology movement, and a Mormon woman who has quit the church over its opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment – have set about the wozniackian project of reverse-engineering every piece of Fidelity hardware and software, to make compatible products that set Fidelity's caged victims free.

They're making floppies that work with Fidelity drives, and drives that work with Fidelity's floppies. Printers that work with Fidelity computers, and adapters so Fidelity printers will work with other PCs (as well as resprocketing kits to retrofit those printers for standard paper). They're making file converters that allow Fidelity owners to read their data in Visicalc or Lotus 1-2-3, and vice-versa.

In other words, they're engaged in "adversarial interoperability" – hacking their own fire-exits into the burning building that Fidelity has locked its customers inside of:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/10/adversarial-interoperability

This was normal, back then! There were so many cool, interoperable products and services around then, from the Bell and Howell "Black Apple" clones:

https://forum.vcfed.org/index.php?threads%2Fbell-howell-apple-ii.64651%2F

to the amazing copy-protection cracking disks that traveled from hand to hand, so the people who shelled out for expensive software delivered on fragile floppies could make backups against the inevitable day that the disks stopped working:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bit_nibbler

Those were wild times, when engineers pitted their wits against one another in the spirit of Steve Wozniack and SSAFE. That era came to a close – but not because someone finally figured out how to make data that you couldn't copy. Rather, it ended because an unholy coalition of entertainment and tech industry lobbyists convinced Congress to pass the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in 1998, which made it a felony to "bypass an access control":

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/07/section-1201-dmca-cannot-pass-constitutional-scrutiny

That's right: at the first hint of competition, the self-described libertarians who insisted that computers would make governments obsolete went running to the government, demanding a state-backed monopoly that would put their rivals in prison for daring to interfere with their business model. Plus ça change: today, their intellectual descendants are demanding that the US government bail out their "anti-state," "independent" cryptocurrency:

https://www.citationneeded.news/issue-78/

In truth, the politics of tech has always contained a faction of "anti-government" millionaires and billionaires who – more than anything – wanted to wield the power of the state, not abolish it. This was true in the mainframe days, when companies like IBM made billions on cushy defense contracts, and it's true today, when the self-described "Technoking" of Tesla has inserted himself into government in order to steer tens of billions' worth of no-bid contracts to his Beltway Bandit companies:

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/lawmakers-question-musk-influence-over-verizon-faa-contract-2025-02-28/

The American state has always had a cozy relationship with its tech sector, seeing it as a way to project American soft power into every corner of the globe. But Big Tech isn't the only – or the most important – US tech export. Far more important is the invisible web of IP laws that ban reverse-engineering, modding, independent repair, and other activities that defend American tech exports from competitors in its trading partners.

Countries that trade with the US were arm-twisted into enacting laws like the DMCA as a condition of free trade with the USA. These laws were wildly unpopular, and had to be crammed through other countries' legislatures:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/11/15/radical-extremists/#sex-pest

That's why Europeans who are appalled by Musk's Nazi salute have to confine their protests to being loudly angry at him, selling off their Teslas, and shining lights on Tesla factories:

https://www.malaymail.com/news/money/2025/01/24/heil-tesla-activists-protest-with-light-projection-on-germany-plant-after-musks-nazi-salute-video/164398

Musk is so attention-hungry that all this is as apt to please him as anger him. You know what would really hurt Musk? Jailbreaking every Tesla in Europe so that all its subscription features – which represent the highest-margin line-item on Tesla's balance-sheet – could be unlocked by any local mechanic for €25. That would really kick Musk in the dongle.

The only problem is that in 2001, the US Trade Rep got the EU to pass the EU Copyright Directive, whose Article 6 bans that kind of reverse-engineering. The European Parliament passed that law because doing so guaranteed tariff-free access for EU goods exported to US markets.

Enter Trump, promising a 25% tariff on European exports.

The EU could retaliate here by imposing tit-for-tat tariffs on US exports to the EU, which would make everything Europeans buy from America 25% more expensive. This is a very weird way to punish the USA.

On the other hand, not that Trump has announced that the terms of US free trade deals are optional (for the US, at least), there's no reason not to delete Article 6 of the EUCD, and all the other laws that prevent European companies from jailbreaking iPhones and making their own App Stores (minus Apple's 30% commission), as well as ad-blockers for Facebook and Instagram's apps (which would zero out EU revenue for Meta), and, of course, jailbreaking tools for Xboxes, Teslas, and every make and model of every American car, so European companies could offer service, parts, apps, and add-ons for them.

When Jeff Bezos launched Amazon, his war-cry was "your margin is my opportunity." US tech companies have built up insane margins based on the IP provisions required in the free trade treaties it signed with the rest of the world.

It's time to delete those IP provisions and throw open domestic competition that attacks the margins that created the fortunes of oligarchs who sat behind Trump on the inauguration dais. It's time to bring back the indomitable hacker spirit that the Bill Gateses of the world have been trying to extinguish since the days of the "open letter to hobbyists." The tech sector built a 10 foot high wall around its business, then the US government convinced the rest of the world to ban four-metre ladders. Lift the ban, unleash the ladders, free the world!

In the same way that futuristic sf is really about the present, Picks and Shovels, an sf novel set in the 1980s, is really about this moment.

I'm on tour with the book now – if you're reading this today (Mar 4) and you're in DC, come see me tonight with Matt Stoller at 6:30PM at the Cleveland Park Library:

https://www.loyaltybookstores.com/picksnshovels

And if you're in Richmond, VA, come down to Fountain Bookshop tomorrow and catch me with Lee Vinsel tomorrow (Mar 5) at 7:30PM:

https://fountainbookstore.com/events/1795820250305

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/04/object-permanence/#picks-and-shovels

#st augustine did write that pirate dialogue with Alexander the Great#what do i mean by infesting the sea? the same thing you do#but because i have a ship and you have a fleet#i am called a pirate and you are called an emperor#justice removed what#says augustine#are nations but great bands of robbers?

498 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexmark's toxic printer-ink

"Every pirate wants to be an admiral." That is a truism of industrial policy: the scrappy upstarts that push the rules to achieve success then turn into law-and-order types who insist that anyone who does unto them as they did unto others is a lawless cur in need of whipping.

This is true all over, but there's an especial deliciousness to see it applied to printers and printer ink, always a trailblazer in extractive, deceptive and monopolistic practices of breathtaking, shameless sleaze.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/11/ink-stained-wretches-battle-soul-digital-freedom-taking-place-inside-your-printer

Pierre Beyssac, a director of Internet Europe, recounts his campaigns in the Printer Wars, which start when he ordered a non-wifi-enabled Lexmark printer but got shipped the wifi version.

https://twitter.com/pbeyssac/status/1386988213923983362

He didn't mind...except that the two models use different models of ink-cartridge, and he'd preordered €450 worth of cartridges, which were nonreturnable by the time he discovered the error.

The cartridges are identical; all that stops them from working is that they're DRM-locked, with software that refuses to run if you put it in a different model printer (this lets Lexmark charge more for an identical product if they think some customers are price-insensitive).

But there's an answer - a Chinese vendor sells a €15 conversion kit that bypasses the DRM (this is probably illegal in the EU under Article 6 of 2001's EUCD). Beyssac was able to salvage his €450 ink investment.

But the adventure prompted him to investigate further. He discovered that Lexmark uses DRM to "regionalize" cartridges (similar to DVD regions): a cart bought in region 1 won't work in a printer bought in region 2.

Hilariously, Lexmark claims that this is because each cartridge is specially tuned for each region's "humidity." By way of rebuttal, Beyssac points out that all of Russia shares a region with all of Africa (!).

(Likewise, the Canadian Arctic shares a region with the Pacific Northwest and the Arizona desert)

Now all of this would be idiotic enough if it were any old printer monopolist, but because this is Lexmark, it is especially delicious,.

Lexmark, after all, fought one of the most important battles of the Printer Wars - and lost. Lexmark vs Static Controls was brought by Lexmark when it was a division of the early tech monopolist IBM.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/06/felony-contempt-business-model-lexmarks-anti-competitive-legacy

Lexmark sold toner cartridges filled with the cheap and abundant element carbon, and it wanted to charge vintage Champagne prices for it. To that end, Lexmark ran a 55-byte program in a "security chip" that flipped an "I am full" bit to "I am empty" when the toner ran out.

Lexmark's competitor Static Controls reverse-engineered this trivial program so you could refill a cartridge and flip it back to "I am full" so the printer would recognize it. In 2002 Lexmark sued, under Sec 1201 of the recently passed Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

DMCA 1201 made it a felony to traffick in a device that "bypassed an access control for a copyrighted work." The judge asked Lexmark which copyrighted work was in its printer cartridges (it wasn't the carbon powder!). Lexmark said it was the 55-bytle program.

The judge handed Lexmark its own ass, ruling that while software could be copyrighted, a 55-byte I-am-full/empty program didn't rise to the level of copyrightability - it wasn't even a haiku.

Lexmark lost, and today, Lexmark is...*a division of Static Controls.*

That's right, the company that's using all this bullshit DRM to prevent people from using their printers the way they want to is the company that did the exact same thing to IBM, won its court case, and then merged with the company whose racket it had destroyed.

Every pirate *seriously* wants to be an admiral.

But here's the thing. Lexmark/Static turned on the fact that 55-byte programs (all that fit affordably in a primitive 2002 chip) wasn't a copyrighted work. The cartridges Lexmark sells now have thousands of lines of code.

There's whole OSes in there. These *are* copyrightable. As is the OS in every embedded system we buy, from car engine parts to smart speakers to pacemakers. That means that companies can use DMCA 1201 to prevent rivals from unlocking lawful features in their products.

They can use it to block independent repair and independent security audits. They can make it illegal to use any product you own in ways that disadvantages their shareholders, even if that's what's good for you.

Despite the "C" in DMCA standing for "copyright," this isn't copyright protection, it's felony contempt of business model - a legally enforceable obligation to arrange your life to benefit multinational corporations' shareholders.

And worse, this law has been spread around the world thanks to the US Trade Rep: it's in 2001's EUCD and Canada's 2012 Copyright Modernization Act. Last summer, Mexico passed an even more extreme version as part of the USMCA.

If you think this shit is odious when it's in your printer, you're going to hate it when it's in your toothbrush, wristwatch, car engine and toaster.

https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2020/01/unauthorized-bread-a-near-future-tale-of-refugees-and-sinister-iot-appliances/

In 2016, EFF brought a lawsuit to overturn DMCA 1201 on behalf of Bunnie Huang and Matt Green. It has been working its way through the courts ever since.

https://www.eff.org/cases/green-v-us-department-justice

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcasting Part III of "The Internet Heist"

This week on my podcast, I read the final part of “The Internet Heist,” my Medium series on the copyright wars’ early days, when the entertainment and tech giants tried to leverage the digital TV transition into a veto over every part of our lives.

https://onezero.medium.com/the-internet-heist-part-iii-8561f6d5a4dc

In Part I, I described the bizarre Broadcast Flag project, where Hollywood studios and Intel colluded with a corrupt congressman (later Phrma’s top lobbyist) to ban any digital product unless it had DRM and blocked free/open source software:

https://onezero.medium.com/the-internet-heist-part-i-3395769891b0

In Part II, I recount the failure of the Broadcast Flag (killed by a unanimous Second Circuit decision), and how the studios pivoted to “plugging the Analog Hole”: mandatory kill-switches for recorders to block recording of copyrighted works:

https://onezero.medium.com/the-internet-heist-part-ii-cb2add31a4fb

This week’s installment describes the global efforts by the studios to seize the future by creating a bizarre DRM system for the DVB digital TV standard (called CPCM), which is used in most of the world (but not the US/Canada, Mexico, or South Korea).

The centerpiece of CPCM was the “Authorized Domain,” a euphemism for “a family.” The creators of CPCM wanted to develop a DRM that would let you share videos within your household, but not with the world. But of course, that meant that they had to define what a real family was and then turn that definition into a technical standard.

The group — an almost all-male, all-white group of wealthy executives from some of the largest corporations on Earth — had some very weird ideas about what a “family” looked like. For example, they spent a lot of time figuring out how to support an Authorized Domain that included seat-back videos in a luxury SUV and a PVR in an overseas vacation home. But when I asked if they could support, say, a family whose parents lived in the Philippines, with one kid working construction in Qatar, another nursing in San Francisco, and a third as home help in Toronto, they called it an “edge case.” Obviously, there are a lot more families that look like that than have luxury SUVs and French chalets for weekends away.

It wasn’t just poor people who got the shitty end of the stick in these standards meetings. One bizarre turn came when they contemplated how to support a joint-custody arrangement whereby a child changed households every week. The system was designed to limit how often a device could be severed from one “domain” and joined to another, to prevent “content laundering.” This meant that a 12 year old who went from Mom’s house to Dad’s every week would find her devices locked out of one or both domains.

The solution to this came from an exec at a giant software company. They explained that when their own customers tripped a fraud-detection system when entering a license key into a new installation, they were prompted to call a toll-free number to get a bypass. If you had a good explanation for why you were reusing a license key (say, you were upgrading, or reinstalling after a malware infection), the customer service rep on the other end could override the system.

Let that sink in for a moment. If you’re a 12 year old girl who’s been locked out of your parents’ digital system, all you need to do is call a strange adult in a distant land and explain the circumstances of your parents’ divorce and the resulting custody arrangement. You have to do that once a month or so, until you attain adulthood or your parents get back together.

The thing is, European law (Article 6 of the EUCD) and US law (Sec 1201 of the DMCA) makes it a crime to bypass a DRM system like CPCM. That lets these cartels act as de facto legislators: if every device has DRM, and if DRM is illegal to bypass, then doing anything prohibited by the DRM is illegal.

This is how the map becomes the territory. Rather than having to design a standard that conforms to all the different kinds of households people form out there in the world, you define a “family” in a standard and then all the families have to conform to the standard. The computer says “no,” and you can’t say “no” back.

Thankfully, the bad publicity and natural enmity among the coconspirators turned CPCM into a historical footnote with little uptake. But in the intervening years, mergers in entertainment, broadcasting, sports and tech have made it easier than ever for industries to conspire to constrain the lives of billions of people by coming up with private agreements about how their tech will work.

Here are the podcast episodes:

Part I:

https://craphound.com/news/2022/02/07/the-internet-heist-part-i/

Part II:

https://craphound.com/news/2022/02/13/the-internet-heist-part-ii/

Part III:

https://craphound.com/news/2022/02/21/the-internet-heist-part-iii/

And here are direct links to the MP3s (hosting courtesy of the @InternetArchive; they’ll host your stuff for free, forever):

Part I:

https://ia801407.us.archive.org/26/items/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_413/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_413_-_The_Internet_Heist_Part_I.mp3

Part II:

https://ia801504.us.archive.org/9/items/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_414/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_414_-_The_Internet_Heist_Part_II.mp3

Part III:

https://archive.org/download/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_415/Cory_Doctorow_Podcast_415_-_The_Internet_Heist_Part_III.mp3

And here’s the RSS feed for my podcast:

https://feeds.feedburner.com/doctorow_podcast

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#1yrago UK consumer review magazine Which?: your smart home is spying on you, from your TV to your toothbrush

The UK consumer review magazine Which? (equivalent to America's Consumer Reports) has published a special investigation into the ways that Internet of Things smart devices are spying on Britons at farcical levels, with the recommendation that people avoid smart devices where possible, to feed false data to smart devices you do own, and to turn off data-collection settings in devices' confusing, deeply hidden control panels.

The findings are pretty bonkers: HP Envy 5020 Printer broadcasts the name of every file you print as well as sending it to HP; Philips Sonicare Bluetooth electric toothbrush tracks your location; all 200,000 ieGeek 1080p IP Camera's usernames and passwords are exposed on a badly secured website; and an unnamed smart TV contacted 700 different IP addresses during 15 minutes' use.