#etruscan liver

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some artifacts from the practice of haruspicy, the practice of examining sheep livers to divine the future.

This practice went back even farther in time than oracle bones, and it was quite widespread. The oldest evidence we have of liver-based divination dates back almost 4,000 years, and the practice eventually spread all over the Near East and Mediterranean, from Mesopotamia to Rome.

Priests used clay or metal guides to help them find the will of the gods in the livers of animals. Here's a clay guide from ancient Babylon:

And an Etruscan one, made of bronze:

Much more on liver analysis, palm-reading and more here:

{Buy me a coffee} {WHF} {Medium} {Looking Through the Past}

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haruspex (pl. Haruspices)

Haruspices were Etruscan diviners who used the entrails of sacrificial animals to determine the will of the Gods. Very often they would examine the liver and gallbladder of a sheep. This life size bronze model is subdivided into sections and inscribed with the names of individual Etruscan deities. Last edit: 10/24/24 10:53am MT | Source 1 | Source 2 | Source 3 |

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Saturday, so time for a little Satre post! This deity is traditionally connected to Saturn. They appear on the Liver of Piacenza and are one of the nine aiser able to throw lightning. Saturn ended up being entirely Roman in origin! Yet, in my personal practice, I still connect Satre to Saturn - similar to the way I worship Eostre, despite her poor attestation in Anglo-Saxon myth & research. Satre does not have any artistic depictions. Yet through their connection to Saturn, I see Satre as a male deity. I haven't quite experienced/talked to/divined with him yet, but I plan to! I may do some divination today. Śin Satre!

#etrupol#etruscan polytheism#etruscan paganism#rasenna#etruscan#satre#liver of piacenza#aiser#ais#obscure deity

1 note

·

View note

Text

Liver of Piacenza, bronze model of sheep's liver for the practice of haruspicy, Etruscan, 2nd C BC

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

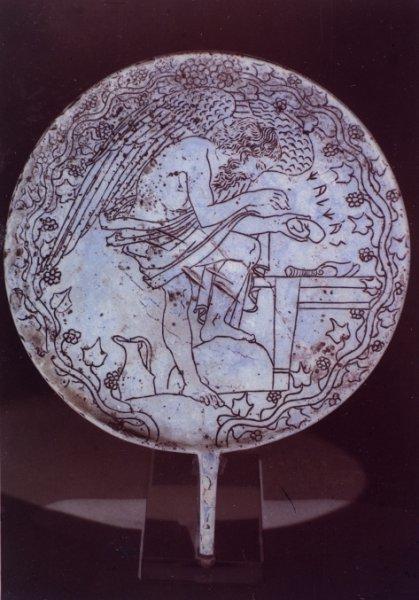

Etruscan bronze mirror of Calchas the Seer Reading a Liver. Late fifth century BCE.

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat!! 👻👻

TRICK!!!!!! have this 2nd century BCE etruscan model / diagram of a sheep’s liver used for haruspicy! happy halloween!!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Between the first and the sixth century a single theological and several medical authors reported on the consumption of gladiator's blood or liver to cure epileptics. The origins of the sacred or apoplectic properties of blood of a slain gladiator, likely lie in Etruscan funeral rites. Although the influence of this religious background faded during the Roman Republic, the magical use of gladiators' blood continued for centuries. After the prohibition of gladiatorial combat in about 400 AD, an executed individual (particularly had he been beheaded) became the "legitimate" successor to the gladiator.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

digital.

“The Etruscans believed that signs in the natural world, such as thunderstorms or , as we have seen, the flight of birds, or even the entrails of sacrificed animals, expressed the will of the gods. In fact, they viewed the liver as a sort of microcosm…”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

sorry if this is "cringe" but i would kind of love a liver haruspicy diagram tattoo based on that etruscan bronze model

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tivr, god of the moon

[ID: A photograph of the moon over a lilac purple sky, with small clouds to the near left and the bottom left of the image. To the bottom right is a cliff side, with another smaller cliff side behind the first. The moon is in a fingernail cresent.]

view this post on wordpress.

Tivr, Tiv, or Tiur, (Etruscan tiu/tiur, “month”) is the ais of the moon. They have been recognised as the moon ais as Tivr stands opposite to Usil on the Liver of Piacenza, on the “negative” side where the aiser of death and night reside. Converserly, Usil (at sunrise) and Tiv (at sunset) are separated on the liver from the sunset zone by the Suspensorium hepaticum (falciform ligament). As for syncretism, Tivr was likely identified with Luna and Selene akin to how Usil was identified with Helios and Sol.

Tivr’s symbol is the crescent, as witnessed in the heraldic symbol of the Tiuza family of Chiusi. Their tomb dates to the third-century within Tassinaia and is decorated with crescent moons, along with a shield marked with a lunar phase.

CATHA, GODDESS OF THE MOON?

Nancy de Grummond argues that Catha, the daughter of Usil, is a lunar goddess. Tiur’s name is mentioned in a dedicatory inscription on a bronze crescent to Catha reading “mi tiiurs kaθuniiasul.” The relationship between the two if we take Catha as a lunar goddess is unknown.

MODERN WORSHIP

Tivr is a deity with very little information. Many scholars identify Tivr as feminine due to Luna and Selene, however this may be untrue as no known depiction of Tivr exists. In modern worship we can worship Tivr as the god of the moon/month and let our experiences guide us in understanding this obscure ais.

References

de Grummond, N. T. (2004). For the Mother and for the Daughter: Some Thoughts on Dedications from Etruria and Praeneste. Hesperia Supplements, 33, 351–370. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354077

Stevens, N. R. (2009). A new reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven. American Journal of Archaeology, 113(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.113.2.153

The religion of the Etruscans. (2006). In University of Texas Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.7560/706873

Turfa, J. M. (2012). Divining the Etruscan world: The Brontoscopic Calendar and Religious Practice. Cambridge University Press.

#dragonis.txt#tivr deity#rasenna polytheism#rasenna polytheist#etruscan polytheist#etruscan polytheism#etruscan paganism#rasenna paganism#aiser#paganism#pagan#witchblr#witchcraft

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Etruscans were still using this kind of sheep liver based divination over 1,000 years later!

I can't remember the details, but apparently abnormalities in certain areas corresponded with flock killing diseases. So when organ readers, known as Haruspexs, predicted calamity, there was an actual factual basis for it.

Clay Object resembling a Sheep’s Liver. This is inscribed with magical formulæ; it was probably used for purposes of divination, and was employed by the priests of Babylon in their ceremonies.—Photo W.A. Mansell and Co

Myths & Legends of Babylonia & Assyria by Lewis Spence, 1916

- The Project Gutenberg

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

MADRE Museum _ Napoli

December2024 _ May 2025

Rasna? is exhibited @museomadre in dialogue with the enchanting site specific installation room Ave Ovo (2005) by Francesco Clemente, as part of the exhibition GLI ANNI | Cap. 1 - among the works of an enlightening selection of Artists:

Carlo Alfano, Oli Bonzanigo, Benni Bosetto, Luciano Caruso, Federico Del Vecchio, Maria Adele Del Vecchio, Luciano Fabro, Dora García, Nan Goldin, Helena Hladilova, Mimmo Jodice, Allan Kaprow, Luisa Lambri, Mark Leckey, Valerio Nicolai, Piero Manzoni, Francesco Matarrese, Ugo Mulas, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Vettor Pisani, Ugo Rondinone, Andrew Norman Wilson

Truly thank you to @evafabbris for curating this inspiring exhibition and to all the Museum team.RASNA? (2021) is an empirical study of ancient metallurgical techniques, with a focus on ritualistic Etruscan practices (9th-1st century BCE), engaging with a contemporary quest on divination.

It is a collection of three life size anatomical sculptures that recall the form of the human liver, created in bronze with traditional lost wax casting techniques and hand gilded with 22-carat gold leaf.

Rasna? is part of Madre - museo d'arte contemporanea Donnaregina in Napoli @museomadre permanent collection since 2021, as winner of the public call of CANTICA 21 - ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY ART EVERYWHERE - Under 35 section, promoted by MAECI-DGSP and MiC-DGCC.

0 notes

Text

The Story of Chianti Classico: Legends, Tradition, and Anecdotes

Chianti Classico, a renowned Italian wine, has a history rich in legends, traditions, and anecdotes. Nestled in the heart of Tuscany, this wine has captivated the palates of connoisseurs for centuries. In this article, we will embark on a journey through time to explore the fascinating story behind Chianti Classico, uncovering the tales of its origins, the traditions that have shaped its production, and the amusing anecdotes that have become intertwined with its legacy.

The Origins of Chianti Classico: The origins of Chianti Classico can be traced back to the Etruscans, who cultivated vineyards in the region more than two millennia ago. However, it was during the Middle Ages that Chianti Classico began to take shape as we know it today. Legends speak of a Florentine knight, Black Rooster, who used a rooster's crow to mark the borders of the Chianti region. This act led to the establishment of Chianti's boundaries and ultimately contributed to the birth of Chianti Classico.

Traditions and Regulations: Chianti Classico's production is governed by strict regulations that have preserved its authenticity and quality. The Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico, established in 1924, plays a vital role in safeguarding the wine's heritage. The consortium's mission includes protecting the distinctively shaped bottle, the black rooster emblem, and the traditional winemaking techniques unique to Chianti Classico. The use of Sangiovese grapes, the primary varietal of Chianti Classico, is a testament to its deep-rooted tradition.

The Sangiovese Grape and the Terroir: At the heart of Chianti Classico lies the Sangiovese grape, which thrives in the region's unique terroir. The vineyards, situated on hilly slopes, benefit from the Mediterranean climate and the limestone-rich soils. The Sangiovese grape exhibits a remarkable range of flavors, from red fruits and spices to earthy undertones. Winemakers carefully blend this varietal with other indigenous and international grapes to achieve the perfect balance and express the true essence of Chianti Classico.

The Evolution of Chianti Classico: Throughout history, Chianti Classico has undergone various transformations and faced numerous challenges. In the 1970s, the addition of white grapes to the blend caused controversy and compromised the wine's reputation. However, visionary winemakers recognized the need for change and pushed for higher quality standards. In the 1980s, a new classification system was introduced, elevating Chianti Classico to DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) status, the highest level of Italian wine classification. This change marked a turning point for Chianti Classico, propelling it into the global spotlight.

Chianti Classico in Pop Culture: Chianti Classico's allure extends beyond the realm of wine enthusiasts. It has left an indelible mark in popular culture, including literature, art, and film. It gained widespread recognition in the novel "Under the Tuscan Sun" by Frances Mayes, where it served as a symbol of the Italian way of life. Additionally, the iconic straw-covered bottle, known as a "fiasco," has been depicted in countless paintings and advertisements. Notably, the line "I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti" from the film "The Silence of the Lambs" added a chilling yet memorable association with the wine.

Chianti Classico: A Culinary Delight: Chianti Classico's versatility and ability to complement a wide range of dishes make it a favorite among wine enthusiasts and food lovers alike. The wine's acidity and tannins pair perfectly with classic Tuscan cuisine, such as Bistecca alla Fiorentina (Florentine steak) and Pappardelle al Cinghiale (wild boar ragu). Additionally, its smooth and velvety texture makes it an ideal accompaniment to aged cheeses and rich, decadent desserts.

Conclusion: The story of Chianti Classico is one of ancient origins, tradition, and adaptation. From the mythical Black Rooster to the meticulous regulations that govern its production, this wine is a testament to the dedication and passion of the winemakers in the Chianti region. With its rich history, diverse flavors, and cultural significance, Chianti Classico continues to captivate wine enthusiasts around the world. Raise a glass to this iconic wine, and let its tales of legends, traditions, and anecdotes transport you to the picturesque hills of Tuscany.

Read my Book on Chardonnay! Amazon Kindle Book

FRANCESCO PRESTINI - Owner of iWina shops and iWina.pl - Wine Blogger wineopener.pl & medium.com/@wineopener.pl - Books: STORES — AMAZON - Wine importer ecoshurtowniawin.com

0 notes

Photo

Etruscan Liver of Piacenza

Die Bronzeleber von Piacenza stellt eine Schafsleber dar und stammt aus dem 1 Jhd v Chr. Sie diente als Lehrmodell für etruskische Priester (Haruspices) zur Leberschau.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liver of Piacenza, Etruscan, 2nd century BCE.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Liver of Piacenza, a lifesize model of a sheep's liver used for haruspicy, the Etruscan practice of divination through the inspection of animals' entrails. Bronze, 2nd cen BCE.

210 notes

·

View notes