#especially when there are noticeable differences between early instalments and their later more well-known versions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

antwerp real

#looney tunes#marvin the martian#art attag#you know sometimes I wonder like#if people who follow this blog but not my main blog have any idea what to expect here anymore#anyway I loveee little titbits and trivia about long-running characters and how they developed over the years#especially when there are noticeable differences between early instalments and their later more well-known versions#e.g. m.oominmamma didn't get her apron until the newspaper comics!#so learning that marvin's original internal name was antwerp is cool!!#which is such a fun name in itself!! bc not only is that said to derive from the myth of roman solider#it can also be read as a portmanteau of ant and twerp! marvin's cute for the alliteration and satisfying similarity to martian#but man that's a good bunch of wordplay#I also love consuming any sort of supplementary/promotional/concept material of things and finding out mel blanc once recorded a song#called ''antwerp is my name'' for like a stage show or something which is Likely lost media by now is#Such a shame#bc that was probably the only time it was officially used outside of chuck jones' personal notes before his current name was chosen#lost media my beloathed :(#not searching for it that's fascinating but just that it like. occurs at all#anyway hi I didn't post any art for over month thank you for reading my infodumping here#oh & also I know he's been shown without the helmet & he really is just a little bowling ball. but I want to believe

496 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bitterness in the Age of Fighting

I was excited when the first episode of Fighting in the Age of Loneliness appeared in my youtube feed last Monday, I’m willing to watch anything Jon Bois puts his name on right now. Most of his content is centered around American football and basketball and baseball, which is great, those are all sports I have watched at least semi-regularly at some point in my life, but for the past few years I’ve followed Mixed Martial Arts more closely than any of them. Felix Biederman, the writer and narrator of the show, was a new name to me: I know Chapo Trap House by reputation but the most I have ever heard of it is a few clips out of context.

That first episode did some strong establishing work to set the tone and context for the series, and then got to work telling the fascinating story of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and the Gracie family. It’s a story I know decently well, I think Felix did a good job of picking out the interesting characters and especially the moments of class struggle, and of course his words are backed up by the datawave audiovisual stylings of Jon Bois that we have come to know and love. The political ideas were more familiar and less interesting to me than the bits about fighting but I was curious to see how the show was going to try to draw connections and parallels between the rise of MMA as a spectator sport and the socio-political environment in which that rise took place.

I was engaged and I watched each episode as it came out through the week and by the end of episode four on Thursday I was starting to turn a little on the series. In this era of Youtubers with healthy Patreon support and good microphones I’ve gotten used to clear, smoothly edited, well recorded voice work and for me Felix’s narration falls short there, especially for a project with a major media company behind it. More than that, though, I was no longer on board with where the show seemed to be going, and I was worried that it would end on a sour note. I found myself agreeing with Felix’s political commentary but disagreeing more and more with his thoughts on MMA and the way he was choosing to frame the history of the sport.

The final installment disappointed me more than I had feared it might, enough to motivate me to make some kind of response to or critical reading of the whole series. Re-watching it with that in mind I (unsurprisingly) found more things I disliked. Fighting in the Age of Loneliness does an excellent job of telling the story of the ancestry, birth, rise, fall, second rise and anticipated second fall of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, but along the way it makes some pretty big missteps and takes some positions that I strongly disagree with. I’m not going to break down each episode individually but I do want to lay out the issues I have with the series and in particular dig in to the problems with the last episode. Towards the end I think I might even call Felix Biederman a fascist.

First, I want to provide some context for my own thoughts about MMA, and make some inferences and assumptions about Felix’s history with the sport that I think go some way to explaining why we see it quite so differently.

*

I am absolutely not a long-time hardcore Mixed Martial Arts fan, until relatively recently I didn’t have any interest in combat sports at all. Growing up in the UK around the turn of the millenium I was aware of boxing but only from a distance, it was already well on its way to fading from the forefront of the popular sporting consciousness, and my pacifist socialist middle-class parents certainly weren’t watching Mike Tyson fights. The first contact I had with what I would later know as MMA was a grainy video I remember watching on some pre-YouTube video sharing site as a teenager: a highlight montage of a man wearing black, red and white shorts kicking various different people in the head in various different boxing rings, with the same concussive effect each time.

I became more aware of the modern sport of MMA when I started noticing the UFC in mainstream sports media headlines around 2014. Three names kept appearing in those headlines: Jon Jones, for running into things with cars, Conor McGregor, for running his mouth, but most of all Ronda Rousey, for running through every challenger the UFC put in front of her. I suspect that there are a lot of newer MMA fans who, like me, were swept up in the hype surrounding Rousey and McGregor during that time, and stuck with the sport after they finally broke their respective winning streaks and came back down to earth.

Three years later even though I watch MMA most weekends and even though I have become almost as fascinated as Felix Biederman seems to be with the history of the UFC, the people who have fought in it, and the things that they have done to each other, I still consider myself a ���casual’ fan. This is at least partly because when I think of ‘real’ or ‘hardcore’ MMA fans, I think of people like Felix, who have been around the sport for a lot longer and are, at best, skeptical about the results of its most recent jump in popularity.

Felix doesn’t explicitly talk about the genesis of his interest in the sport but there are hints in the text. The general tone of the piece goes from being detached and historical in the first episode to personal and emotional in the last, which I think is both a deliberate choice on Felix’s part and a reflection of his own experience. The third episode, when his narrative reaches the mid-2000s, is when I think it transitions from learned history to memory, and it’s around here that Felix starts making frequent references to goings on in MMA fan culture. If I’m correct then Felix Biederman has been following MMA for at least a decade longer than I have really known what it was. He has had the time to become emotionally invested in fighters and even the UFC as an organisation in ways that I am not, and of course his initial views on the sport were formed a relatively long time ago. MMA fights in 2018 don’t look all that different than they did in 2005 but the UFC has certainly changed a lot in that time, as have public awareness of and attitudes towards a new generation of combat sports stars.

*

That decade and a half of change in the UFC is the real focus of Fighting in the Age of Loneliness, but it presents itself as something much broader. The first episode is titled ‘The Invention of Fighting for Money’ and in it Felix makes a lot of sweeping statements about the past that don’t hold water. He very much tells the winner’s version of history, the narrative favoured by the UFC and the Gracie family, who would have you believe that they invented not only the modern sport of MMA but somehow the very idea of fighting itself. Felix remarks on the marketing and promotional skills of Rorion Gracie in the second episode without seeming to realise quite the degree to which he has himself fallen prey to them, and he also comes across as having the slightly fetishistic attitude towards East Asian martial arts that has become common in the USA over the past half century or so.

As he transitions out of the prologue, Felix says “the true catalyst for MMA as a sport, business and spectacle go back to Japan”, and when he goes on to describe the spread of Jujutsu from Japan to Brazil he says “after hundreds of years, Martial Arts had finally broken containment.” At the end of the series he proclaims that the “fourth era of fighting itself” is currently beginning and that the previous two ‘eras’ only lasted a handful of years each.

These generalisations don’t stand up to even the lightest scrutiny. The history of Martial Arts or combat sports or fighting or whatever term you care to use goes back much farther than feudal Japan, and some of the other things Felix says imply that he is at least partially aware of this. As he is giving his starry-eyed take on the life of Judo’s inventor he says “As long as there are people, they will at some point want the ability to keep someone from kicking their ass, no matter how unlikely it is that they will ever get into a fight.” It strikes me as particularly American that his argument in favor of combat sports being inherent to human society is based on the concept of self-defence. I prefer a line of reasoning that is similar but based on competition: As long as there are people, they will at some point want to test their wits and skill and strength against each other.

Indeed, the story as we know it of unarmed combat sports is as old as recorded history: there are images of wrestling in four thousand year old Egyptian tombs, and the classical Greek Olympics included an event called Pankration, which could be roughly translated as ‘fighting with all of your power’, that had an almost identical ruleset to early Ultimate Fighting Championship events.

Felix oversimplifies the history of fighting as a whole, but even if we just look at what he says about Mixed Martial Arts he gets it wrong. In episode one he says “The entire sport of Mixed Martial Arts owes its existence to Mitsuyo Maeda” and then in episode two he alleges that “A world where proto-MMA existed outside of gymnasiums in Brazil seemed pretty unlikely in 1976.” A corollary of my earlier statement might be that as long as there are people testing their wits and skill and strength against each other, there will be other people who think they can do it better. People have been pitting different schools of fighting against each other and amalgamating them long before the Gracie clan existed.

A decade before the date when Felix claims that mixed martial arts were confined to Brazil, Bruce Lee was blending Wing Chun with other styles to formulate Jeet Kune Do. A decade before that a Japanese Karateka was devising a ruleset which would eventually become Kickboxing to facilitate competitions between karate and Muay Thai. In the 40s the Kajukenbo school was founded in Hawaii with the goal of rigorously testing multiple fighting styles against each other to determine which elements of each were the most effective. In the 30s a Czechoslovakian Jew was refining the boxing and wrestling he had been taught in gyms into Krav Maga in brawls against anti-semitic thugs.

In Victorian London the Bartitsu school taught gentlemen a blend of five different fighting styles from around the world, while in the music halls exhibition matches pitted boxing against Savate. Savate was itself developed over the preceding century by efforts to find a middle ground between the heavy-booted street fighting style spreading from French ports and the Queensbury rules boxing that was popular in England.

Even the legend of the birth of Muay Thai, a fighting style which has had arguably as much influence on the modern sport of MMA as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, is a story about mixed martial arts: when the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma captured a famous fighter during their battles with Siam in 1767, they offered him the chance to win his freedom if he could demonstrate the superiority of his Siamese boxing style against the Burmese school, which he promptly did by knocking out ten Burmese opponents.

Felix contradicts himself on this topic in the first episode when he describes Jigoro Kano studying western wrestling and sumo to augment his Jujutsu training and develop Judo. In the second episode when he says “In 1993 no one knew anything, and most people still thought that if you did karate the right way you could blow up somebody’s heart” he is obviously being facetious but he is also projecting his own ignorance outwards. There has always been fighting, all over the world, and there have always been evolving schools of thought about the best ways to fight and the best rules for fighting as a sport. The story of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and the Ultimate Fighting Championship is captivating but it is not, as Felix presents it, the only story about fighting. In this regard, as with others, he seems to have internalized the some of mystique that the UFC has cultivated around itself and its history.

*

Once the history lesson is over I think Fighting in the Age of Loneliness hits its stride and Felix’s passion for the Pride FC and UFC fights and fighters that drew him into the sport shines through in the writing and the narration. His criticisms of the ways that the UFC continues to underpay and otherwise mistreat its fighters are spot on and if anything he could have gone into its anti-union policies in more depth. Before I get to the final episode, there are a few smaller criticisms I want to get out of the way.

Firstly, I would like to have seen more about modern women’s Mixed Martial Arts in the show. I largely chalk this up to the difference in perspective on the sport between Felix and myself: a female fighter was what drew me to watch the UFC in the first place so my image of the sport is one that has always included women, whereas Felix got his start watching Pride, which had no female fighters, and an all-male era of the UFC. There were women competing in MMA at that time and a few exclusively female promotions but if Felix ever watched any of them he doesn’t mention it. In the end, Ronda Rousey gets a minute and a half, Joanna Jędrzejczyk gets about 30 seconds and Cristiane Justino gets a name check.

Rousey is the only female fighter to be mentioned outside of the quarantined WMMA portion of the show, and she comes up during a rather odd accusation of nepotism that Felix levels at Dana White, one which I have heard from other longer-standing UFC fans. I am no supporter of Dana’s and I’m not seeking to defend his character, but it seems far more likely to me that the reason the UFC put so many promotional resources behind Ronda Rousey and Conor McGregor is not, as Felix supposes, simply because Dana White personally liked those two fighters, but rather because he saw the opportunity to make a lot of money off of them, which he did. Dana is a fight promoter, he is notoriously fickle in his affections and the warmness he displays towards any given fighter is directly correlated to their ability to drive pay-per-view buys for his promotion.

I also think that there are some more straightforward explanations for the UFC’s success than the poetic ones that Felix understandably focuses on. The ideas of the UFC as a refuge for outcasts and the alienated, both as fighters and as fans, and the honesty of single combat in an age of uncertainty are clearly very thematically important to Fighting in the Age of Loneliness as a project. For me the series places too much importance on the role those things played in the current popularity of the sport and doesn’t put enough emphasis on, or even mention at all, some more mundane but more significant contributing factors.

The vacuum at the top of combat sports that was created when boxing all but collapsed under the accumulated weight of decades of corruption and promotional malpractice, and the brief but significant success that the WWE had with a grittier presentation of professional wrestling in the late 90s both set the stage for the rise of modern MMA in the USA. That rise was helped along by things like the value of the walk-off head kick knockout and the fourteen second armbar victory in the age of the highlight clip and the animated GIF, and the mix of astuteness and good fortune that led the UFC to put out a reality TV show featuring actual physical conflict at a time when programming was being dominated by reality shows based on exaggerating and continually re-hashing interpersonal squabbles.

*

At the end of episode four, titled “As the world fell apart, the only magic was in the cage”, Felix’s rhetoric about the things that happen during UFC fights reaches its most florid, mythological heights. Against a montage of post-fight embrace photographs he says “The magic that we wish we saw everywhere else was in the cage [...] At least there was one place where unthinkable things actually happened, at least if you put two weird people with incredible abilities in front of each other their combined experiences and opposing martial abilities would create a beautiful, maddening story.” I am not criticising Felix for being more captivated by the emotion and passion of fighting than I am but the praise and reverence which he lavishes upon his favourite period of the sport’s recent history at the end of the fourth episode clashes brutally with the way he starts the fifth.

“No-one is ever content to just like something, especially not nowadays”, he says. “We’re not just fans of things any more. We declare our media consumption habits to determine the types of people we are [...] now if someone doesn’t like something we like they hate us” These lines and the visuals that accompany them are presented as a barb aimed at the legions of TV personality and pop star fans bitterly defending their territory on social media. Although there is a hint of self-deprecation about this segment I don’t read much self-awareness here, mostly just old fashioned middle-class punching down at the popular culture of the working class.

In the way he frames what he views as the best period of the UFC’s history, Felix is himself engaging in, as he puts it, “battles that our millionaire entertainers will probably never give a shit about or even find out about”. He has taken to the field of the culture war to defend his memory of a past version of a massive, sinister entertainment company against the changes that he perceives to be ruining it.

Here is where the bitterness begins to creep in, and build. Felix starts talking about the insecurity of modern MMA fans and the sport’s image problem, but then he abruptly dispenses with those concerns and starts arguing that MMA should remain insular and niche. A this point he also waves a huge screaming red flag by describing Jon Jones as a “weird person” who is “actually pretty fascinating once you get to know him” and who has “more depth than most would know”, but we’ll get to that later.

“Who gives a shit if we don’t have hundreds of millions of people watching with us every time, and why do we care if people think we’re fucked up or weird for watching it. We know what our sport is, and we know who we are [...] It’s our stupid violent insane spectacle sport for freaks and assholes that’s as legitimate or illegitimate as any other sport in the world. Well, at least it was ours at some point.”

I recognised this argument the moment I heard it. It sounds almost word for word like an insecure gamer defending video games as an art form and as a hobby that is just for real nerds and not the masses. I know that argument very well because I have been that insecure gamer in the past. In complaining that MMA is not “ours” anymore he has jumped from “if someone doesn’t likes something we like they hate us” to “if someone likes something we like for the wrong reasons they hate us”.

This is the tone that Felix adopts for the entire final episode, and he proceeds to decry three recent changes he thinks the UFC has made in an effort to bring the sport into the mainstream, changes that he declares as already being “to the detriment of the viewers, the fighters, and ultimately, [the UFC] themselves”.

The first is the Fox TV deal, of which his criticism is that it has led to too many fights and therefore too many fighters, but he doesn’t present any reasons why more fights has been a bad thing. He talks about how poorly the UFC compensates its rank-and-file fighters, which is a great argument for better fighter pay, but is not an argument for fewer paid fighters or fewer fight cards.

The second is the UFC’s apparel deal with Reebok, which he accurately assesses as a disaster for their fighters.

The third is drug testing, and for me this is where Fighting in the Age of Loneliness goes completely off the rails. The first thing he says in this segment is probably the only part of it I agree with: “the vast majority of your favourite athletes use steroids.”

*

Felix is right that the UFC asked the US Anti-Doping Agency to start testing its fighters more to provide an image of legitimacy than because they actually care about fair competition, but his main problem with the policy is that performance enhancing drugs are in fact cool and good. Earlier in the series he celebrates the way that Pride FC’s “loose medical oversight” and “pro-steroid policy” allowed its fighters to “consistently break laws of god and man,” now he gleefully exclaims that “Steroids are actually kind of amazing.”

“The human body is absolutely not designed to fight for 15 to 25 minutes, but steroids help make it work”. Felix provides no justification whatsoever for this claim, and it’s a ridiculous one that springs from the same myopic view of the history of combat sports that he expresses in the early episodes. To present just one counterexample, fighters in classical Greece did not have the benefit of modern nutritional science and training methods, let alone anabolic steroids, but the only time limit on Pankration bouts was sunset. Fights that last more than 25 minutes might not be the most fun to watch but they’ve certainly been happening since long before the steroid era.

Felix doubles down on this position. While he acknowledges that steroids “have their side effects” he asserts that “it is impossible to compete at the highest levels of fighting without some chemical help.” This is another absurd claim, he does try to back this one up but in doing so he immediately undermines it: “Talk to any retired fighter, and they’ll give a number anywhere from 75 to 90 percent of their former training partners juicing.” Rather than proving his point, this statement suggests that it is not at all impossible to compete at the highest levels of fighting without chemical help because at the very least ten percent of fighters are doing it. This scaled-back version of his original pronouncement does make the prospects of success seem pretty bleak for clean fighters, but Felix doesn’t care. He is happy to accept that if most fighters are doping then fighters need to dope to compete and therefore it is OK for fighters to dope.

USADA testing in the UFC has, in Felix’s opinion, fucked things up. There are a lot of very valid criticisms that he could make about the inconsistent way that the policy has been applied to different fighters or the odd ways it has conflicted and overlapped with state athletic commission testing policies or the lack of fighter engagement in the process of rolling out the program leading to confusion and uncertainty about the rules, but he doesn’t. Instead of talking about the massive unregulated supplement industry in the USA and the habit that some supplement brands have of ‘accidentally’ slipping a bit of the good stuff in their products to make sure that their customers get the gains they crave, he complains that fighters are being punished for “by-products of over the counter substances”. By-products and contaminants are not the same thing, I’m not sure if Felix just misspoke here or if he genuinely doesn’t understand the problem he is talking about.

He goes on to moan that the punishments for breaking the rules of the sport are longer under this new program. He doesn’t say why the longer bans are bad, just that the UFC has been ‘capricious’, and it seems obvious to me that the reason he disagrees with the longer bans is that he thinks PED usage is a good thing. Let’s address that idea.

There are two main reasons why I think performance enhancing drugs should be banned in almost all sports. The first is that PED use is bad for the long term health of athletes. We know that there are permanent negative effects associated with the use of anabolic steroids, and there are scores of other widely used PEDs that simply haven’t been around for long enough for the consequences of their use to be properly understood. It is possible to argue from this position for the regulation and standardisation of PED use in sports, and although I disagree with that line of reasoning I do think it has some merit, but there is no hint of this argument in Fighting in the Age of Loneliness.

I think the most practical way to prevent athletes from being incentivised to gamble with their future health for short-term gain, especially in a sport like MMA which already carries so much physical risk, is to ban the use of PEDs and enforce that ban with testing. Felix talks about steroids helping fighters to recover quickly from serious injuries, but I don’t think that is a worthwhile tradeoff to ask them to make, and I don’t think it would be a bad thing for the health of fighters if less prevalent PED usage meant that fewer of them had to endure the accumulated physical toll of fighting four or five times a year.

The second reason is a purely sporting one. The rules of all sports are arbitrary, but they usually constitute an attempt to delineate a competition that tests one particular set of skills and abilities in its competitors and excludes others. Chess is not designed to be a test of split-second reflexive reactions, 100 meter sprinting is not supposed to challenge your ability to predict the strategy your opponent is going to employ and prepare a counter-strategy, and as far as I am aware there is no sport that seeks to test its competitors ability to improve their bodies through medical intervention. I want the sports I watch to be fair competitions that are about what they are about, and Felix does too: he repeatedly praises the “truth” and “honesty” and “earnestness” of “what goes on in the cage,” but he fails to see how this contradicts with the idea of allowing the outcomes of fights to be heavily influenced months ahead of time by means of one fighter having access to less scrupulous, less restrained doctors than the other.

There is some nuance here around where you draw the lines between sports nutrition, necessary medical assistance and doping, but again Felix does not adopt a position so sophisticated. It’s been demonstrated in almost every popular sport that athletes with the help of an organised and scientific doping program have a significant advantage over clean rivals with similar levels of experience and training, and that’s not a contest I was ever interested in watching. Fighters shouldn’t use steroids any more than match sailors should use outboard motors, it is contrary to the very concept of the sport.

*

Felix isn’t just mad about USADA testing because he thinks steroids are nifty, though. He’s also mad that they took away one of his favourites. “At the absolute highest level of the sport, no-one was derailed by this as much as Jon Jones” This is another part of Fighting in the Age of Loneliness that emphasises the gulf between Felix Biederman’s perspective on the UFC and my own. He watched Jon Jones’ rise through the ranks and his multi-year reign as the consensus best fighter in the world, and was apparently completely captivated by it. In describing him Felix returns to the hagiographic tone of the third and fourth episodes, describing him as “a giant, freak athlete who did moves that he learned off of youtube to humiliate fighters we grew up with”, comparing him to Napoleon, calling him “a genius who can destroy world champions with stuff he saw in a movie, the equivalent to those savant kids who can hear a song once and instantly play it on a piano perfectly”

By the time I was starting to watch the UFC, Jon Jones had already sabotaged his career fairly comprehensively. I don’t know Jon Jones as a legend or a genius or the greatest fighter in the world because I’ve never seen the fights that earned him that reputation. Here are the things that I do know about Jon Jones, things that have happened or that I have learned about since I started following the sport:

Jon Jones is a homophobe. In 2012 Jon Jones crashed his car, plead guilty to driving under the influence, and received a slap on the wrist. In January 2015 Jon Jones tested positive for cocaine in an out-of-competition test and was issued a token fine. In April 2015 Jon Jones ran a red light and caused an accident involving two other cars that left a pregnant woman with a fractured arm, then ran away only to turn himself in after an arrest warrant was issued and eventually plead guilty to fleeing the scene of an accident, receiving 18 months of probation. In 2017 Jon Jones was given a one year suspension after testing positive for banned hormone and metabolic modulators, which turned out to be contaminants in an erectile dysfunction pill he had been given by a training partner. In 2018 Jon Jones tested positive for an anabolic steroid and was suspended again for 15 months.

On the front steps of courthouses Jon Jones is humble and apologetic, and in the immediate aftermath of being caught doing something he shouldn’t have he often talks about how hard the experience has been for him and how much he has learned from it and grown as a person. At all other times he acts as though the bad things that happen to him or around him are never his fault, that he has no responsibility to ever change or even reflect upon his own behaviour, as though in all these struggles he has been the victim of cruel circumstance and conspiracy.

The Jon Jones that Felix describes is not someone I recognise, and the way he describes him is concerning. “As we got to know Jon more, we saw his personal foibles, like his DUI arrest and rivalry with Rashad Evans” I don’t think that having a heated rivalry with a competitor is comparable with drunk driving at all, and in framing the incident this way Felix trivializes it. He does this again with Jones’ hit-and-run conviction, mentioning it in passing but quickly moving on to quip about how awesome Jones got at powerlifting in his year off. He calls Jones “a person with failings who sometimes acted like an asshole, got pissed off and said incredibly cutting things to his opponents”, reinforcing the impression that Jones’ main character flaw is simply being too fierce a competitor, instead of calling him, say, a person with failings who sometimes acted like an asshole, took drugs he shouldn’t and crashed cars.

Felix is constantly making excuses for Jon Jones in this part of the episode. When he gets to the second failed drug test, he says Jones “got popped by USADA”, a turn of phrase that subtly reinforces Jones’ own narrative of victimhood, especially since Felix has already established USADA as the bad guys who are fucking up the UFC. He wraps up the Jones segment with a ‘boys will be boys’ defence couched in another appeal to the glory of days gone by: “It used to matter less if you acted like an idiot. Everyone was a bit of an idiot in one manner or the other in life, but god forbid you now embarrass the sport”.

*

From here, Fighting in the Age of Loneliness whines to a messy conclusion. The segments get more disjointed, it’s at this stage that modern women’s Mixed Martial Arts gets all of two minutes of consideration, and then there is a rather reluctant summary of the UFC career of Conor McGregor, who Felix seems not to like. He certainly doesn’t describe him with close to the same kind of exaltation that he deploys earlier for fighters who had similar trajectories like Mauricio Rua, Anderson Silva and Jon Jones.

After that, Felix goes back to behaving like a fan of an indie band that has started making top 40 hits. He doesn’t like that the one of the UFC’s new part-owners is an asset stripping firm, even though in his golden age one of the UFC’s part-owners was an Emirati war criminal. Back in the first segment of the first episode he references “this modern era of fighting, where all of the things that used to make the sport unusual are mostly gone,” and now he returns to that idea and calls the supposed new “fourth era” of fighting “sanitized and oversaturated,” contrasting it with the “honesty of a fist-fight” and the “cultural haven for strange people” that the UFC offered ten years ago. He complains that there aren’t enough knockouts any more. When he brings up the recent long-anticipated fight between Conor McGregor and Khabib Nurmagomedov he says “sometimes the dam of normalcy breaks and we get momentary bursts of how things once were,” which strikes me as a rather ‘what have you done for me lately’ attitude to take about something that happened the month before this video series came out.

Things drag closer to an end and Felix keeps returning to his golden age. “What was once a weird refuge for those who needed it is now eroding into just another thing that’s as formless and indistinct as everything else. Fighting has rid itself of so much of its magic. It does not transcend the world any more.” The way that he constantly makes references to a bygone era when everything was simple and pure and good and as it ought to be, and wishes dearly that we could return to that era instead of continuing to face the injustices of this current moment in time, reminds me a lot of an ideology that has has a big resurgence in the USA recently.

The episode wraps up with one final spasm of bitterness. “This will happen to everything that you love. Nothing you like will remain untouched, and it will get further and further monetized into meaninglessness. This isn’t just our problem in our idiotic bloodsport. You’re fucked too.” He’s not wrong about the commoditization of entertainment and sports-as-entertainment but he sounds once again like a whiny gamer stereotype or a disillusioned popstar fanboy of the kind he mocks at the start of the episode.

And then the episode doesn’t actually end. The sort-of epilogue about Donald Cerrone fighting Nate Diaz seven years ago is a good little segment, but it doesn’t do anything here. It doesn’t serve to illustrate or emphasise any of the things Felix has been talking about in the minutes leading up to it, it doesn’t follow from them in any kind of narrative. It feels like a piece that some combination of Felix Biederman and Jon Bois just liked too much to cut, even though they couldn’t find a place to put it, so they stuck it here at the end. Maybe it is intended to provide some sense of denouement after Felix’s angry ranting. Regardless, it comes at the end of such an unpleasant half hour that its attempt at poignance failed utterly on me.

*

Felix Biederman likes different fighters than I do, he has a perspective on the sport of Mixed Martial Arts that often seems parochial and outdated to me, and I am puzzled by his obsession with the idea that combat sports athletes are all strange, broken people, but none of these things would bother me if Fighting in the Age of Loneliness did not present itself as an authoritative, comprehensive history of fighting, instead of what it is, which is the story of Felix Biederman falling into and out of love with the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Together with Jon Bois he certainly tells that story well, their collage of tales of societal fracture and political indifference with images of single combat is a powerful one, but in pursuing its thematic goals the series fails over and over to justify or interrogate the positions it puts forward.

If the UFC disappeared tomorrow, or if it had never been created in the first place, fighting would still exist, Mixed Martial Arts would still exist, the “one two path of a punch to a guy snoring on the ground” that Felix claims to adore will still exist. Fighting is exactly as magical and exactly as mundane today as it it always has been and always will be, even if Felix Biederman doesn’t enjoy watching it as much as he used to.

#Fighting in the Age of Loneliness#Felix Biederman#Jon Bois#SBNation#UFC#MMA#Chapo Trap House#Jon Jones#PEDs#Fighting#Combat Sports#Ronda Rousey#Conor McGregor

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

In Quest for Herd Immunity, Giant Vaccination Sites Proliferate EAST HARTFORD, Conn. — With the nation’s coronavirus vaccine supply expected to swell over the next few months, states and cities are rushing to open mass vaccination sites capable of injecting thousands of shots a day into the arms of Americans, an approach the Biden administration has seized on as crucial for reaching herd immunity in a nation of 330 million. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has joined in too: It recently helped open seven mega-sites in California, New York and Texas, relying on active-duty troops to staff them and planning many more. Some mass sites, including at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles and State Farm Stadium in suburban Phoenix, aim to inject at least 12,000 people a day once supply ramps up; the one in Phoenix already operates around the clock. The sites are one sign of growing momentum toward vaccinating every willing American adult. Johnson & Johnson’s single-dose vaccine won emergency authorization from the Food and Drug Administration on Saturday, and both Moderna and Pfizer have promised much larger weekly shipments of vaccines by early spring. In addition to using mass sites, President Biden wants pharmacies, community clinics that serve the poor and mobile vaccination units to play major roles in increasing the vaccination rate. With only about 9 percent of adults fully vaccinated to date, the kind of scale mass sites provide may be essential as more and more people become eligible for the vaccines and as more infectious variants of the virus proliferate in the United States. But while the sites are accelerating vaccination to help meet the current overwhelming demand, there are clear signs they won’t be able to address a different challenge lying ahead: the many Americans who are more difficult to reach and who may be reluctant to get the shots. The drive-through mass vaccination site on a defunct airstrip here in East Hartford, outside Connecticut’s capital, shows the promise and the drawbacks of the approach. Run by a nonprofit health clinic, the site has become one of the state’s largest distributors of shots since it opened six weeks ago, and its efficiency has helped Connecticut become a success story. Only Alaska, New Mexico, West Virginia and the Dakotas have administered more doses per 100,000 residents. Most of the people running mass sites are learning on the fly. Finding enough vaccinators, already challenging for some sites, could become a broader problem as they multiply. Local health care providers or faith-based groups rooted in communities will likely be far more effective at reaching people who are wary of the shots. And many of the huge sites don’t work for people who lack cars or easy access to public transportation. “Highly motivated people that have a vehicle — it works great for them,” said Dr. Rodney Hornbake, who serves as both a vaccinator and the East Hartford site’s medic, on call for adverse reactions. “You can’t get here on a city bus.” Before dawn on a recent raw morning, Susan Bissonnette, the nurse in charge, prepared enough vials of the Pfizer vaccine and diluent for the first few hundred shots of the day. At 7:45 a.m., her team surrounded her in a semicircle, stamping the snow off their boots and warming their fingers for the hours of injections that lay ahead. “We’re going to start with 40 vials, eight per trailer,” Ms. Bissonnette shouted to the group of 19 nurses, a doctor and an underemployed dentist who had volunteered to help. “OK, so remember it’s Pfizer, right? Point three milliliters, right?” The site vaccinates about 1,700 people on a good day, partly because Connecticut is small and gets fewer doses than many other states. It is a well-oiled machine, with a few dozen National Guard troops directing cars into 10 lanes, checking in people, who have to make appointments in advance, and making sure they have filled out a medical questionnaire before moving down the runway to their shots. Troops also supervise the area at the end of the runway where people wait after their shots for 15 minutes — or 30, if they have a history of allergies — in case of serious reactions. In between are the vaccinators, two per car lane, trading on and off between jabbing arms. When they need to warm up, they retreat inside heated trailers to draw up doses and fill out vaccination cards. “If you simply open up with 10 lanes, it will be chaos unless you have teams all along the way at checkpoints, executing on the plan you’ve laid out,” said Mark Masselli, the president and chief executive of Community Health Center, which opened the East Hartford site on Jan. 18 and has since opened two smaller versions, in Stamford and Middletown. “You’ve got to marry some groups together — folks with health care delivery sense and folks with logistics sense.” The site came together in six days, as Mr. Masselli’s staff worked frenetically with the state to install trailers, generators, lights, a wireless network, portable bathrooms, traffic signs and thousands of orange cones to mark the lanes. Every worker has two all-important pieces of equipment: a walkie-talkie to communicate with all the stations and supervisors, and an iPad to verify appointments or enter information about each patient into a database. Updated Feb. 28, 2021, 12:03 a.m. ET The vaccine they use is Pfizer’s, which adds complexity because it has to be stored at minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The supply is kept in an ultracold freezer that Community Health Center installed at the adjacent University of Connecticut football stadium. Ms. Bissonnette and other supervisors speed there in bumpy golf carts several times a day to grab more vials, which last for only two hours at room temperature. The first cars roll in at 8:30, often driven by the adult children or grandchildren of those getting shots. Drive-through clinics can be better for infection control, some experts say — people roll down their car windows only for the injection — and more comfortable than standing in line. But a month into the Connecticut site’s existence, its weaknesses are also clear. Traffic can get snarled on the busy road leading to the site, and bad weather can shut it down, requiring hundreds of appointments to be rescheduled on short notice. Spotty vaccine supply, which forced sites in California to close for a few days recently, can also wreak havoc. More significantly, you need a car, gas money and, for some elderly people, a driver to get to and from the site. At this point, white people comprise 82 percent of those seeking shots at the East Hartford site, down from 90 percent in early February; their overrepresentation is partly because the older population now eligible is less diverse than the state overall. To address problems of access and equity, FEMA is opening many of its new mass sites in low-income, heavily Black and Latino neighborhoods where fear of the vaccine is higher, vaccination rates have been lower and many people lack cars. In addition to its mass sites, Community Health Center, which serves large numbers of poor and uninsured people in clinics around the state, is also planning to send small mobile teams into neighborhoods to extend its vaccination reach. The East Hartford site has hired several dozen temporary nurses and trained its dentists and dental hygienists to help with the shots. Still, staffing the site with 22 vaccinators daily remains a challenge, one that will grow nationally as more people become eligible for the shots. Dr. Marcus Plescia, the chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said the need for mass vaccination sites might wane as more and more of the low-hanging fruit — Americans who are highly motivated to get vaccinated as soon as possible — is picked. “I think they have worked well in the current setting of demand substantially exceeding supply, drawing on many people who are eager to be vaccinated,” Dr. Plescia said. “As supply increases, and we have vaccinated the eager, we may find that lower-volume settings are preferable.” Mobile vaccination clinics will reach some of the vaccine hesitant. But Dr. Plescia said people who are uncertain and fearful would be best served by doctors’ offices or community health centers where they can talk it through with health care providers they know. “They’re not there to counsel you,” he said of mass sites. “You go to get the shot, end of story.” Dr. Nicole Lurie, who was the assistant health secretary for preparedness and response under President Barack Obama, said that instead of just asking FEMA for help, state and local governments should seek input from private companies used to keeping large crowds moving — while keeping them safe and happy. In one such example, the company running Boston’s mass vaccination sites contracted with the event management firm that runs the Boston Marathon to handle day-to-day logistics. Several companies that ran large coronavirus testing operations are also involved in mass vaccination. “These sites need to be motivated to make this a good experience for the customer, especially since they’re working with a two-dose vaccine,” Dr. Lurie said. “If it’s really a pain in the neck, why would you go wait in line again a few weeks later?” Most sites say their main challenge is not having enough supply to meet demand. But with 315 million more Pfizer and Moderna doses promised by the end of May, and Johnson & Johnson pledging to provide the United States with 100 million doses of its newly authorized vaccine by the end of June, that complaint may fade before long. The biggest headache for the East Hartford site has been the system for booking appointments, a clunky online registry known as VAMS that is being used in about 10 states. Many people 65 and older have had such a hard time navigating it that most end up calling 211, the phone number for health and social services assistance, to make appointments instead. As the hours pass, the eternally smiling vaccinators in East Hartford get tired — and sometimes bone cold. But sometimes there are unexpected boosts, such as when John Rudy, 65, pulled up with his mother, Antoinette, in the back seat. “We’ve got a 100-year-old!” Jean Palin, a nurse practitioner, announced as she prepared Ms. Rudy’s shot. The site usually closes at 4 p.m., but there was a problem: There were more no-shows than usual that day, in the middle of a snowy week, and there were 30 unused doses. Word went out from nurses at the site, including to people working at a nearby big-box store, who were not all eligible but could qualify for a vaccine if the alternative was throwing it away. “It’s just a precision game toward the end of the day,” Ms. Bissonnette said. At 5:15, Greg Gaudet, 63, drove up, teary with excitement. He had learned from one of the nurses, a former high school classmate, that a shot was available. “I have a luckily dormant cancer, but my immunity is low,” said Mr. Gaudet, an architect whose form of leukemia was diagnosed six years ago. “I’m so grateful.” How much the site will cost over time remains “a question that we are eager to work through,” Mr. Masselli said. Community Health Center spent about $500,000 to set it up and is spending roughly $50,000 a week on labor and other costs. It receives a fee for each shot it can bill insurance for — the Medicare rate is $16.94 for the first dose and $28.39 for the second — but is also counting on reimbursement from the state and FEMA for start-up and other costs. Still, the expense has not stopped Mr. Masselli from imagining an expansion. “There’s another runway over there,” he said, gesturing behind him. “Between the two, with two shifts, we could do 10,000 a day. March 14 is Daylight Saving Time; we’re going to pick up warmer weather, more light. The timing is right.” Source link Orbem News #giant #herd #immunity #Proliferate #Quest #sites #Vaccination

0 notes

Text

10 Things In Sci-Fi Movies You Didn't Know Were CGI | ScreenRant

From early pioneers like Tron and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, to game changers like Episode 1: The Phantom Menace and The Matrix trilogy, CGI has been used to augment the ideas and themes presented in science-fiction films. Science fiction as a genre provides different perspectives on how we think of everything from the future of our race, to the perils of technological advancement and the complexities of space travel. Computer graphic imagery and the advancements in that field help filmmakers realize their visions in ways that weren't possible with practical effects alone.

These days, CGI is more prevalent in science-fiction films than ever before. We're used to seeing the big spectacle of space battles in the latest Star Wars film. We've become accustomed to the exotic aliens of Star Trek films. But what about when CGI is used so subtly you don't even notice it? Or for things other than giant spaceships and strange extraterrestrials? Below you'll find ten things in sci-fi movies you didn't know were CGI.

10 Star Wars: The Force Awakens

Sometimes the CGI in sci-fi films is used not for huge battles or giant creatures, but to fix mistakes or recreate common objects. CGI has become a staple in the latest Star Wars films, especially for obvious things like ships, planets, space. But it was also used rather subtly and to great effect in The Force Awakens.

RELATED: Star Wars: Kylo Ren's 10 Best Moments (So Far)

The dialogue between Supreme Leader Snoke and Kylo Ren about Ren really being Ben Solo, Han Solo's only son, was meant to be later on in the film. Therefore, it was filmed with Ren's helmet off. JJ Abrams decided the reveal should come sooner, and the scene had to be reshot, with a CGI mask placed over Adam Driver's face. You can't tell it isn't a real helmet.

9 Deus Ex Machina

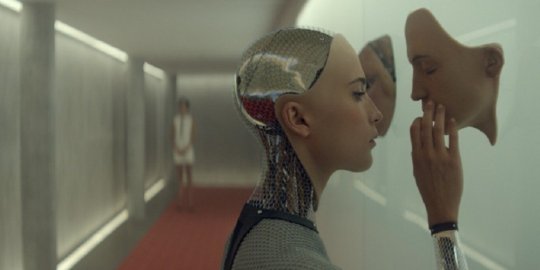

Deus Ex Machina is a genre film that relies more heavily on ideas than visual effects, as implied by the nature of its title, which implies a plot contrivance. Alicia Vikander stars as the cybernetic artificial intelligence unit that is created by the minds of a brilliant programmer and a Dr. Frankenstein-like engineer.

While in many scenes it appears Vikander is wearing some sort of suit that might simulate her cybernetic bodyform, she isn't. Only her face, hands, and feet are her own; everything else is CGI. It moves with such synchronicity to her own body movements as to appear virtually indistinguishable.

8 E.T.

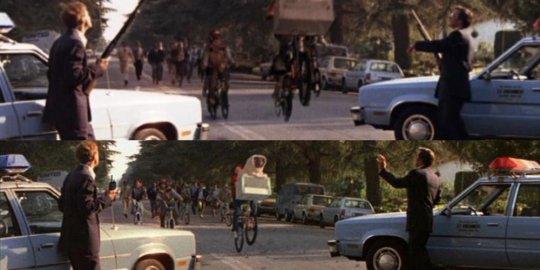

One of Spielberg's landmark films, E.T. didn't make a flashy use of CGI in 1982, with the renowned filmmaker electing to use puppetry and practical effects wherever possible (save of course for the iconic bicycles-to-the-moon-shot). All bets were off when it came to the 2002 DVD release, however.

RELATED: Steven Spielberg's 10 Best Movies, According To Rotten Tomatoes

Spielberg had often said that if he could go back and "fix" anything in the film, it would be the guns used by the police who go after the escaping kids. He felt it was distasteful for officers of the law to draw weapons on children, and used CGI to swap the guns for walkie-talkies.

7 Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park is known for pioneering some incredible CGI effects, many of them the result of blending techniques used in stop-motion film making with modern innovations in computer graphic design. But the dinosaurs weren't the only things being rendered that way.

In the scene where Dr. Grant, Dr. Sattler, and John Hammond's grandchildren are forced to escape into the air ducts of the Visitor's Center, Lex nearly plunges to her doom. The moment where she nearly falls from the edge of the duct to the hungry velociraptor below featured a stunt girl that inadvertently looked into the camera. CGI had to be used to put the actress's face over hers rather than reshoot the scene.

6 War For The Planet Of The Apes

While audiences know that the talking bipedal apes featured in the new Planet of the Apes trilogy aren't real (and also not all played by Andy Serkis), they may not know how CGI is utilized in the rest of the films. Some of the most impressive uses of it are featured in the third film, War for the Planet of the Apes.

While CGI specialists were busy using programs to individually create strands of ape hair, they were also using them to create individual droplets of water, and leaves on trees. A great deal of the forest the apes used as their hideout area, as well as the terrain featured during the battle sequences, was entirely made of CGI despite looking incredibly life-like.

5 Children Of Men

Children of Men was a universally celebrated sci-fi movie when it debuted, in large part due to its visceral vision of a dystopian future. In a time when children aren't born due to infertility reasons, one man must protect the last child of humankind and defend it from a myriad of dangers.

RELATED: 10 Sci-Fi Movies To Watch If You Like Children Of Men

The last baby that Clive Owen's character protects wasn't a real baby at all due to the hazardous nature of the scenes it was featured in (especially him running and jumping across rooftops or amidst gunfire). Therefore it was necessary to use a CGI baby that's so life-like it fooled audiences completely.

4 Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull

While most wouldn't classify Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull as a sci-fi film, the ending would solidly place it in that category. It features the beginning of the Atomic Age, and positions Indy in a world that's beginning to become completely immersed in what lies among the stars.

RELATED: Indiana Jones 5: 10 Scrapped Ideas From Previous Sequels It Should Use

In the opening sequence involving two hot-rods racing (a 1950 Ford Deluxe Army Staff Car vs a 1932 Ford Model B Roadster), one of them rides over a gopher hole. The little critter almost gets himself decapitated by the Model B, before scampering off. That gopher was entirely CGI...for some reason.

3 Waterworld

Waterworld was an ambitious project, some would say too ambitious for a sci-fi film. It was plagued by every conceivable problem on set, had an incredibly bloated budget, problems filming on oceanic locations, as well as hazardous working conditions. It also spent a hundred thousand dollars on making the ocean CGI.

Despite the fact that aerial shots exist, there are scenes in Waterworld where the ocean is CGI, and while it looks fantastic, this contrasts pretty spectacularly with shots of the real thing. This is why the budget ballooned from $100 million to $175 million.

2 Supernova

It's General Hospital, in space! Or it's Supernova, a sci-fi thriller that positions a hospital ship in deep space. Their continuing mission? To answer intergalactic 911 calls. When the Nightingale 229 answers a distress call from another ship, the survivor they bring on board and his alien artifact may trigger a supernova that will wipe out the galaxy.

RELATED: 10 Weirdest Places That Movie Characters Have Sex

Before that catastrophic event happens, there's time for a little hanky-panky. In zero gravity, Angela Bassett and James Spader's character have a sex scene, except they weren't on set to do it. It's really their co-stars, Peter Facinelli and Robin Tunney, with Tunney's skin tone altered in post-production to match Bassett's.

1 Return Of The Jedi

While some Star Wars fans found things to gripe about in the original trilogy's third installment it was, on the whole, a fitting climax to one of the most beloved saga's in sci-fi history. George Lucas would later come out with a trilogy of prequels for Star Wars fans to complain about and, armed with new advancements in CGI, he would go back and alter their beloved film. If you've never seen any other version of the film, you may think the alterations were normal.

When Luke takes Vader's mask off so he can see his son with his own eyes, we see that Vader has no eyebrows in the 2004 Blu-Ray edition. This is because Lucas felt they should've been burned off on Mustafar where he sustained the injuries that put him in the mask to begin with, so CGI was used to remove them. Too bad he didn't stop there...

NEXT: 10 Amazing Movie Scenes That Did Not Use CGI

source https://screenrant.com/sci-fi-movies-cgi-surprise/

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (13): the Question of Using an Oki-dana in the Small Room.

13) On one occasion when Sōeki had entered the Shū-un-an [for a chakai]¹, in the fuka san-jō [深三疊] with the mukō-ro [向う爐] he noticed a [chū-ō-]joku placed on the kagi-datami [かぎ疊]².

[At the beginning of] the hatsu-iri [初入]³, on the upper [shelf] was a celadon censer⁴, [while] below was the mizusashi; and the fukusa was tied to the leg [of the joku]. Then, collected together on a tray, [I⁵] brought out the kōgō, taki-gara-ire [たきから入], and kō-bashi [香ばし]⁶; and [then] one piece [of incense] was burned⁷.

Afterward⁸, the chaire was [displayed] above, while below, the mizusashi and futaoki were arranged together [on the lower shelf]. And while tea was being served according to [the usage associated with] this [arrangement], [Sō]eki said:

“On the whole, when using the mukō-ro, [for the host to consider using] things like a joku or tana -- isn’t it the first [rule] that [we] should not make [the utensil mat appear] so congested? And on top of this, when raising and lowering the kama [during the sumi-temae], or when the hishaku moves from the mizusashi to the kama, and so forth, it becomes nearly impossible [to execute] many of these actions [appropriately in this sort of setting]¹¹.

“[Consequently,] you must understand that it is exclusively the case that the [chū-ō-]joku, and the [various] tana, are reserved for [use in] rooms larger than 4.5-mats, and should never be placed [in rooms of the present sort]¹². [Adhering to this as a principal,] there will therefore be no error in what we do.”

[We] are overcome with emotion [over the wonder of this teaching], and prostrate ourselves [to Rikyū, in thanks]¹³.

_________________________

¹Aru toki, Sōeki wo Shū-un-an [h]e mōshi-ireshi ni [ある時、宗易を集雲庵へ申入しに].

The beginning phrases of the first sentence read like one of the entries in Book One, marking this entry as being completely out of place in the present book.

Furthermore, the content of this passage is questionable on several levels:

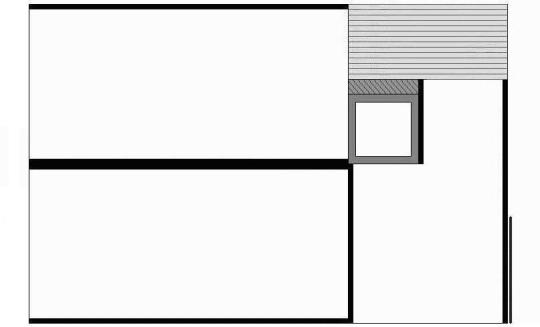

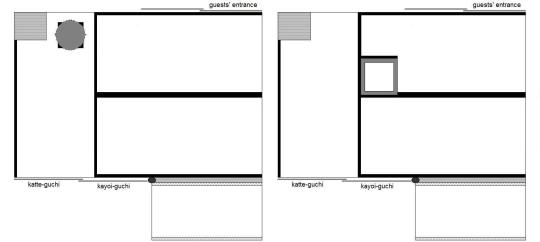

- first, it shows that the author (whom, if it were Nambō Sōkei himself -- as alleged -- would make the entry patently nonsensical) was ignorant of the geography of the Shū-un-an -- since the two three-mat rooms have been conflated (according to the details of this room, as related in Book Two, the older of them featured a mukō-ita -- a board that replaced the far 1-shaku 5-sun of the utensil mat, and a mukō-ro would be cut in front of it, making it impossible to put a tana next to the ro; but the other room, which lacked this board, had the ro cut in one of the adjoining mats, hence it was not a mukō-ro)*;

- secondly, it ignores the fact that Rikyū originally created the kyū-dai [休臺]† precisely so that it could be placed next to a mukō-ro in a three-mat room, meaning that Rikyū could hardly chide Sōkei for doing something for which he himself had established the precedent (especially in the words used)‡;

- and, third, while the date of this alleged interaction is unknown, it seems to overlook the fact that the Shū-un-an had a tsuri-dana attached to the wall in the corner of the room (at least since the end of 1582)**, making it unnecessary for the host to have a reason for wanting to use an oki-dana.

All of which marks this entry as even more blatantly spurious than usual for Book Three of the Nampō Roku††.

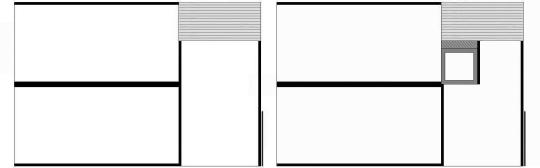

This is one of only six entries from Book Three that Kumakura Isao included in his supposedly complete modern-Japanese version of the Nampō Roku (Nampō Roku wo Yomu [南方録を読む])‡‡, and, as might be expected, he appears to use it as yet another “proof” of the inherent veracity of his school’s teachings. __________ *This means that a mukō-ro would have had to be cut in front of the board, on a daime-sized mat, as shown below -- though doing so would have made it impossible for an oki-dana to be placed next to the ro (since there would be insufficient space for the kama and sumi-tori to be placed in front of the tana during the sumi-temae), as is obvious from the sketch.

Rikyū used this room during the chakai described in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 2 (40): (1587) Sixth Month, Second Day, Morning. The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/183593009914/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-2-40-1587-sixth-month

†Rikyū's eponymous kyū-dai [休臺; the name would now be written 休台] collectively refers to the two tana that we know as the shi-hō-dana [四方棚] (also pronounced yo-hō-dana by people who have been conditioned to associate the sound “shi” with the word for death -- though Rikyū and the men of his generation do not seem to have had this problem) and the maru-joku [丸卓].

The shi-hō-dana [四方棚], which seems to have been the first to have been created of the two, was intentionally made to be placed next to a mukō-ro. Its dimensions correspond to the space available to the left of the ro just as the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子] (from which it was derived) does to the full mat: that is, the ten-ita extends from heri to heri, while the ji-ita is 2-me (1-sun) shy of the heri on both sides (the ten-ita of the kyū-dai daisu measures 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu wide -- which is the same as the space between the heri on a kyō-ma tatami -- by 1-shaku 4-sun deep; the ji-ita measures 2-shaku 7-sun 5-bu wide by 1-shaku 3-sun deep).

◎ Note that the Sen family modified the dimensions of the shi-hō-dana during the early Edo period, perhaps to confuse its origins, or confound Rikyū’s original usage (their version will not fit in the space available beside the mukō-ro); however, the “Rikyū shi-hō-dana” (as it is known in the utensil trade) is still seen from time to time, and it confirms Rikyū's intentions.

The maru-joku [丸卓] (the name comes from the Edo period; Rikyū referred to this tana as a kyū-dai as well) was intended to be placed next to a ko-ita furo (the tana raises the mizusashi to the same height it would have had if placed on the daisu) in the same kind of setting. (Note that a large furo, such as the large iron kimen-buro, is what was supposed to be placed on a ko-ita; and when this is done, the mouth of the kama is the same height -- above the mats -- as that of a kama resting on a medium-sized furo arranged on the daisu. Rikyū was initiated into chanoyu by Kitamuki Dōchin, and the relationships between the utensils determined by the daisu forever influenced his chanoyu.)

It seems that Jōō and Rikyū felt that the 3-mat room was the transitional stage between the shoin (which both he and Jōō held to be the 4.5-mat room) and the small room (2-mat).

‡It seems to have (perhaps, fairly frequently) been the case that people (who had studied with Rikyū, and later whose father or other ancestor had studied with Rikyū) challenged the orthodoxy of the Sen family's teachings. Which, in turn, prompted them to create these deceptions -- rather than simply admit that their machi-shū approach was deficient (and sometimes, simply wrong). In fact, this would have not been very problematic, at least at first, since it was well known to the chajin of his day that Sōtan had a very limited exposure to chanoyu, a consequence of his family's poverty, coupled with his own disinclination to associate himself with those wealthy persons who could have lifted up his condition.

For most of his life, Sōtan seems to have used only the (third) small unryū-gama in the broken old Temmyō kimen-buro (resting on the unglazed gray floor tile that Furuta Sōshitsu had brought back from Korea), or suspended over the ro on a bamboo jizai, with a kiji-tsurube as his mizusashi, an old Hagi bowl that had previously been used for rinsing writing brushes (and so was darkly stained with ink) as his chawan, and a natsume that he had made himself from lacquered paper, tied in a handmade blue paper shifuku. Consequently, there was no reason why he should have known about anything other than the simplest style of chanoyu. Yet rather than admitting to what everyone already knew was true, he (or his handlers, the Tokugawa bakufu) preferred to challenge Rikyū's teachings, and override them as wrongly-remembered fictions.

We see the same thing even today, when certain schools deny that Rikyū's writings are legitimate (because they differ from what those schools prefer to teach), and put their own words in Rikyū's mouth -- all while worshiping him as their tea god.

The same is true when these schools talk about the Nampō Roku. On the one hand, they discount this collection of teachings as a blatant forgery; and on the other, they cherry pick its contents, highlighting those parts that appear to support their school's version of this or that teaching, while patently ignoring the rest (as if it never existed).

**The Shū-un-an dana [集雲庵棚] (which is the technical name for a tsuri-dana suspended in the corner of a room, rather than attached to a sode-kabe on the side of the mat adjacent to the ro) is presumed to have been added shortly after Rikyū created the tsuri-dana (in the Tai-an [待庵] room, at the Myōgi-an, in Yamazaki, Kyōto, during the summer of 1582) -- though the date of its original appearance in the Shū-un-an is completely undocumented (the earliest descriptions of the Shū-un-an, which date from the early Edo period, mention the presence of the tsuri-dana in the corner of the room; but this is, of course, long after the fact). Rikyū's tsuri-dana was intended to replace the fukuro-dana (which, up to then, was commonly -- though not always -- installed within the kamae), hence the necessity of its being on the right side of the mat, adjacent to the ro.

If, however, the Shū-un-an dana came first (as a substitute for a small oki-dana, such as the maru-joku, that was placed next to a ko-ita furo -- or a chū-ō-joku, next to a mukō-ro, as described in this episode), this would have been, historically speaking, most interesting.

††Suggesting that it was added by a different hand from the one responsible for “editing” the original book. Because this passage alludes to one of the Sen family's cardinal principals, it seems likely that one of their agents was responsible for adding this entry to Book Three. (The bakufu, on the other hand, would probably not have ventured to register this kind of objection, since their purpose was in encouraging the use of as many utensils as possible.)

‡‡Since it furthers his purpose of showing that the Nampō Roku “validates” modern Urasenke teachings, reinforcing the notion that Urasenke disseminates the original Rikyū-derived version of chanoyu.

²Fuka san-jō mukō-ro, kagi-datami ni joku wo okite [深三疊向爐、かぎ疊に卓を置て].

The expression kagi-datami [鍵疊] refers to the mat (regardless of whether it is the utensil mat, or a mat that adjoins it*) in which the ro has been cut.

In Nambō Sōkei's own room in the Shū-un-an (which was usually where he entertained his guests), the ro was cut in one of the mats to the right of the utensil mat, as shown in the photos of Kanshū oshō-sama’s reconstruction (above)†, and in the sketch of the original (below, which shows the room as it may have been used during the furo and ro seasons -- though it is possible that Nambō Sōkei used the ro all year round), which would make that mat the kagi-datami. However, it is impossible that a tana would have been placed on that mat.

On the other hand, if this entry is, referring to the historical room that had apparently been erected as the residence of Giō Jōtei [岐翁紹禎]‡ (the room with a mukō-ita replacing the far end of the utensil mat**), while a mukō-ro may have been present, its being cut in front of the mukō-ita would mean that there would have been insufficient space for the host to perform the sumi-temae if a chū-ō-joku was placed to the right of the mukō-ro. (During the furo season, the furo and other utensils would have been placed on the mukō-ita, at the head of the utensil mat; a mukō-ro, if one were cut in this room, as shown in the sketch on the right, would have been located in front of this ita-datami, turning the utensil mat into a daime, meaning it would have been used much like the discredited ichi-jō-han [一疊半] room)

In either case, it is difficult to reconcile historical reality with the details of this entry††. __________ *That said, the term is more commonly employed to designate one of the other mats in the room, rather than the utensil mat. The square mat in the middle of a 4.5-mat room is commonly referred to as the kagi-datami, as is the mat to the right of the utensil mat in a room of six or eight mats.

†According to the monks of the Nanshū-ji, the original Shū-un-an was looted by agents of the Imperial Army around 1930 (at the same time that agents of the Imperial Army attempted to loot, and then burned down, the Enkaku-ji in Fukuoka). Subsequently, they set fire to the building, while giving out that it had been destroyed by an American bombing raid. (The site is now occupied by a kindergarten run by Sakai city.)

Kanshū oshō-sama had visited the original Shū-un-an a decade or so before this incident, and recorded the room’s particulars in great detail. He built a replica of this structure when the Enkaku-ji was rebuilt during the 1950s (on a site granted to Kanshū oshō by the Shōfuku-ji, on land that had previously been a graveyard for secular commoners affiliated with that temple from the time when the Shōfuku-ji had been located within the Korean city-state of Hakata).

‡Giō Jōtei [岐翁紹禎; c 1428 ~ ?] was the illegitimate son of the great Ikkyū Sōjun. It was he who established the Shū-un-an as his residence in his last years. Nambō Sōkei was the second resident monk of this compound.

**In the early days, this ita-datami [板疊] (a board that replaces part of the mat -- which Rikyū referred to as a mukō-heiban [向平板]) was used like the floor of the o-chanoyu-dana, with a large iron kimen-buro and the rest of the kaigu arranged on it. While it is possible that Nambō Sōkei (who was the second occupant of the complex) cut a ro in the floor of Giō’s room, it seems rather disrespectful (and so out of character) that he would have done so. (Rikyū is only mentioned as having used the room during the furo season, when, of course, the furo would have been placed on the mukō-ita, as originally intended by Giō Jōtei.)

††Access to the Shū-un-an was generally prohibited (since the room had been sealed by the Abbot of the Nanshū-ji as soon as Nambō Sōkei's suicide had become known to him); thus the chajin of the early Edo period would have been unaware of the issues which the errors in this material raise. (Indeed, the very secrecy with which Jitsuzan’s manuscript was treated implies that only persons absolutely willing to accept its contents as unequivocal fact would have been granted access to this material, coupled with the fact that it was forbidden to make copies, would have effectively dissuaded side discussions of these questionable details.)

³Hatsu-iri [初入].

Another word for the sho-za [初座].

If there is a difference* between the two terms, it is that hatsu-iri describes things from the host’s perspective, while sho-za refers to the division of the chakai from the guests’ side. __________ *Which, in practice, there is not.

⁴Seiji no kiki-kōro [青磁の聞香爐].

A Chinese celadon censer that was made to be held in the hand while appreciating kyara [伽羅] incense.

These censers were specially made, in China, for this specific purpose -- which is attested to by the fact that the three legs attached to the bottom are not spaced equally (there is a wider gap between the front leg and the one on the left, to allow for the insertion of the fingers of the left hand -- on which the kōro rests while it is supported on the side by the right hand, so it may be lifted up to the nose)*. Kōro not intended for this purpose have the legs that are carefully spaced around the base (so there is no discernible front). This is discussed in greater detail in Book Six of the Nampō Roku.

These censers were always fitted with a lid* (as seen in the photo) because the special ash that was used in them was stored in the censer itself when not in use (the lid, which was made of lacquer-rubbed wood or ivory, kept the ash clean, as well as dry, and allowed the ash to maintain a moisture content comparable to the kōro itself, preventing it from drawing in moisture that might smother the charcoal), which was then tied in a shifuku for storage. As with the temmoku, in Rikyū’s day it was common to remove the kiki-kōro from its shifuku before displaying it in the tearoom.

Nambō Sōkei seems to have been a collector of quality utensils. _________ *Modern antique dealers and tea-utensil merchants, unaware of the purpose, frequently consider such kōro misshapen -- thereby allowing knowledgeable individuals to purchase them at substantially reduced prices.

†Kōro made for burning incense to perfume the air of the room, or for perfuming clothing, are fitted (if any) with a fenestrated lid (to keep things from falling into the burning incense).

⁵The speaker is supposed to be Nambō Sōkei.

⁶Sate bon ni kōgō, taki-gara-ire, kō-bashi kumi-awasete hakobi-dasu [さて盆に香合、たきから入、香ばし組合セて運び出].

A taki-gara-ire [炷空入] is a small container, usually made of ceramic or, less frequently, cloisonné*, into which the used gin-yō [銀葉] (bearing the burned-out piece of kyara incense wood) is discarded after the appreciation of incense is concluded. The small ceramic containers that have been used as kōgō during the ro season since the days of Jōō (who is responsible for establishing this usage), such as Rikyū’s treasured ruri-suzume [瑠璃雀] (shown below), were originally used as taki-gara-ire.

The word kō-bashi [香ばし = 香箸] refers to what exponents of kōdō [香道]† call a kyōji [香筋]† -- small chopsticks made of ivory or ebony, and used to handle the pieces of kyara incense wood.

The gin-yō [銀葉] (mica squares on which the piece of kyara was set to smolder, thus keeping the ash clean) were traditionally placed in the kōgō together with the pieces of incense (the latter enclosed in a paper wrapper as described in the previous installment). __________ *Less frequently because cloisonné pieces can get hot when the gin-yō is discarded into them, thus potentially damaging the tray on which the taki-gara-ire is resting.

In fact, in the context of a chanoyu gathering, since the burning of incense in a hand-held censer takes the place of putting incense into the furo or ro, it has been customary (since the time of Jōō) for the kiki-kōro to be lifted into the tokonoma after the guests have finished appreciating it in their hands, so it can continue to perfume the room throughout the shoza (the purpose of which is to help obscure the smell of the combusting charcoal). Once again, this suggests that the person responsible for incorporating this material into Book Three of the Nampō Roku was a follower of the so-called machi-shū style of chanoyu champoined by Sōtan and his family, rather than a classically trained practitioner who had been a fellow of Jōō (as Nambō Sōkei certainly had been -- it must be remembered that Jōō gathered his early followers from among the ranks of the guests assembled for the Shino family's incense gatherings, and Sōkei seems to have been one of that number).

†In Rikyū's period, there was no Edo period prejudice that demanded that people remain exclusively within their own specialty. Rikyū and his fellow chajin were expected to be equally experienced in the details of appreciating incense (i.e., what is intended by the word kōdō today), flower arranging (ikebana), and even poetry (in the case of Jōō; though to a lesser extent Rikyū, perhaps on account of his dyslexia), as they were supposed to be trained in the serving of tea.

Nambō Sōkei, therefore, given his rank, would surely have been sufficiently educated that he would not have been guilty of this mistake in the basic terminology of incense. Indeed, it was precisely in order to expose this kind of fraud that, even when written “kō-bashi” [香筋], the word was supposed to be pronounced kyōji [きょうじ].

The person who wrote the text of this entry clearly was not a savant: a sense of laissez faire (from anything resembling the classical teachings) characterized Sōtan and his followers’ approach to chanoyu.

⁷Isshu taki [一炷たき].

Shu [炷] is used as the counting word for pieces of incense. That is, one piece of kyara was burned, and the censer was passed around three times; after which the appreciation of incense was concluded.

⁸Nochi ni ha [後には].

In other words, at the beginning of the goza.

⁹...Shosa tsukamatsuri-shi ni [所作仕しに].

Shosa [所作] refers to ones performance (in other words, the series of gesticulations employed while serving tea). This word was never used in this kind of context in Rikyū's period, and clearly dates this text to the Edo period -- as does the verb tsukamatsuru [仕る] (to serve or wait upon), in this context.

¹⁰Dai-ichi sewa-sewashikute funiai sōro ka [第一セわ〰しくて不似合候か].

Dai-ichi [第一] means first of all, in the first place.

Sewa-sewashikute [忙々しくて]: sewashikute [忙しくて] means to be busy, in the sense of looking too busy, or fussy, or (in this case) cluttered. Doubling sewa simply amplifies the negative sense of this expression.