#erhard schön

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Instruction on Proportion, Erhard Schön, 1538

Source: nuremberg.museum

#art#illustration#erhard schön#1500s#black and white#instruction on proportion#german art#woodccut#geometry#renaissance#vintage

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Schlachtschwert, early XVIth century.

Spring steel blade of flat hexagonal section for most its length, mild steel fittings with hollow brass ball finials on the cross. Leather over thread over wooden core for the grip, and leather over wood for the sleeve (more about that below). This is a tentative reconstruction of what a "proper" Landsknecht Greatsword could look like, such a they appear on period artwork, be it paintings like the Siege of Alesia by Melchior Feselen (1533) or the Battle of Pavia kept at the Royal Armouries (or the tapestries depicting that same battle, now at the Museo Capodimonte, made after sketches by Bernard van Orley), the Victory of Charlemagne over the Avars near Regensburg by Albrecht Altdorfer (1518), or the many drawings, prints and woodcuts by artists such as Reinhart von Solms, Jörg Breu, the great Hans Burgkmair, Niklas Stör, Hans Holbein (both Elder and Younger), Virgil Solis, Hans Sebald Beham, the legendary Urs Graf, Daniel Hopfer, Erhard Schön, Hans Schäufelein and others...All of them combined to give this result.

Such swords would be seen not only in the hands of a Doppelsoldner, but also carried by your Feldwaybel or an Edelman. And it would be called a Schlachtschwert in the very captions of the illustrations I mentioned earlier (see Erhard Schön). *Not* a "two-handed Katzbalger", though the cross obviously echoes the S/8-shaped guard of the latter. We clear on that ? Good.

Very few of such swords are kept in museums out there, with a lot of them leaving me dubious regarding their authenticity. The one in Berlin seems to me to be the most genuine of all, and it is on its proportions that I based this piece, though the Berlin sword shows a fancy, diamond-pattern decoration on the quillions very much recalling the Katzbalger kept in the Museum of London. Most if not all period illustration do not show such fancy details on the crossguards though ; they are actually rather plain, without even the ribbing/threading/filework you can find on Katzbalger crosses. Hence I kept this one rather plain, with a square cross section with rounded corners, and some light filework at the center. I also bent the quillions into an offset 8-shape rather than a symmetrical one, to be more consistant with the earlier examples visible in period artwork.

The main questioning was that sleeve at the base of the blade, present on a lot of the period artwork; its obvious function was to provide a spot on which to put the other hand - as can be deduced from Marozzo's teachings for fighting against polearms - but the main issue was how was it made/what was it made of. Elaborating on my previous experience and studies of such things on later Schlachtschwerter, I went for a basic construction of leather glued/stitched over a wood core made of two flat slabs, and force-slid down the blade. There is more than enough friction to keep it well in place, but it is still possible to take it off albeit with some effort. The end of the leather is cut according to period artwork, and flares out to accommodate the mouth of a scabbard if needed. A simple decoration of plain lines on one side, and checkered on the other makes it also consistant with the artwork.

It is 139 cm long, the blade is 1083 mm long, 45 mm wide with a thickness of about 7 mm at its base, tapering down to 3.4 mm near the point. The span of the crossguard is about 21 cm, though from one ball end to the other there's about 73 cm of steel. Weight is 2547 grams, point of balance 13.5 cm from the cross.

Twenty-eight hundred EuroUnits and it's yours.

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the Church of St. Ignatius of Loyola (Rome) there is a huge statue of St. Ignatius standing tall looking up to heaven. In his hand is a book with the words “To the greater glory of God. Constitution of the Society of Jesus.” Beneath him is Martin Luther with a closed Bible. St. Ignatius has his foot on Luther’s neck and Luther is biting the back of his own hand.” (x)

“To the right of the altar (in the Church of Gesus, Rome) sits Pietro Le Gros’ sculpture entitled The Triumph of Faith over Heresy. This sculpture depicts Mary casting Martin Luther and his precursor, Jan Huss, out of heaven. An attendant angel (lower left) rips their translations of the Bible and their writings to shreds. The militant nature of the Jesuits and their mission to spread the faith and reassert the power of the church is clear in this dramatic work.” (x)

St. Ignatius of Loyola tramples Martin Luther, St. Nicholas, Prague.

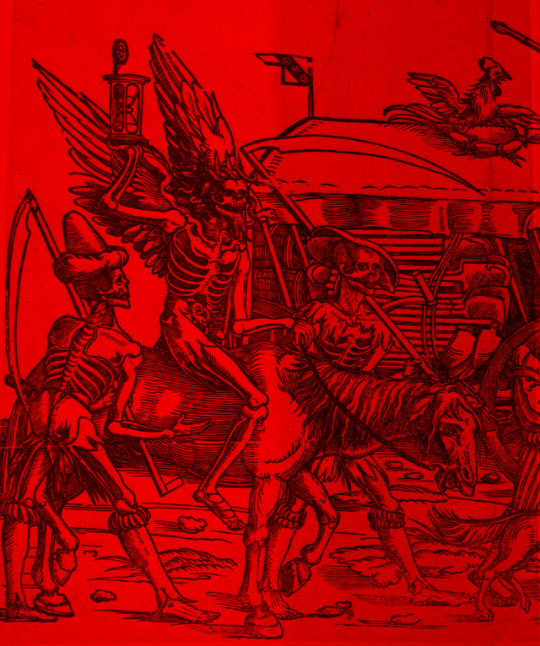

“‘Der Teufel mit der Sackpfeife' [The Devil playing the Bagpipe], [Nuremberg], 1535. The Nuremberg artist Erhard Schön (1491–1542) was a pupil of Albrecht Dürer. When he adopted Lutheranism in the 1520s, he began designing woodcuts for anti-Catholic books and broadsheets. This is one of his most well-known satirical efforts, the devil playing the monk – with bagpipes (wind) featuring. Like cartoons today, this rather grotesque image was designed to amuse and enrage.” (x) The image has since been adopted by Catholics who have dubbed the pictured monk, Martin Luther (x)

#I did a little digging#it’s hilarious to me that that last piece was actually anti catholic and we just adopted it and said nope that’s Luther#this genre fascinates me#catholic#Catholic art#Martin Luther#my catholic thoughts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Devil playing the bagpipes; perched on the shoulders of a monk whose head forms the bagpipe. c.1530 Hand-coloured woodcut with eyes and markings added in black ink. Print made by: Erhard Schön, German, ca, 1530

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My book chapter is finally published!

The book is currently available in hardback but as an ebook any day now - https://brill.com/display/title/64874

Jonathan Trayner – The sword in the ragged sheath; the motif of the peasant radical in sixteenth-century prints

Abstract: This chapter outlines and explores the connections between various prints from the long sixteenth century that used the motif of the peasant carrying a sword in a ragged sheath. Beginning with Schongauer’s Peasant Family Going to Market (1470-5), the motif is traced through the various re-purposings of Schöffer’s peasant figures from his Frankfurter Messeflugblatt (1516), including its use on copies of The Sermon of the Peasant of Wörhd and The Twelve Articles (1520s), the prints of Sebald Beham and Erhard Schön, and the paintings of Hans Wertinger and Bruegel; up until its use on the banner of the Basel peasants of 1653. Connections and relationships between those prints and paintings considered to have art historical merit and less celebrated and ephemeral works are drawn out. The narrative and symbolic meanings of the motif is considered alongside its interpretation by both the urban elites for whom the majority of these works were made, and the peasants who were the subject of these images. The argument being that, with their use and reappropriation of these images in various contexts, the peasants demonstrated a more sophisticated political use of visual symbolism than they are usually considered to possess.

0 notes

Photo

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anamorphosis | dir. Brothers Quay (1991)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Erhard Schön, Schematische Perspektive mit Kubisierungen (1543)

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zerah and Ahad, Erhard Schön, 1531, Brooklyn Museum: European Art

Size: 5 1/16 x 7 7/16 in. (12.9 x 18.9 cm) Medium: Woodcut on laid paper

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/48944

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Portico, Erhard Schön, Cleveland Museum of Art: Prints

Medium: woodcut

https://clevelandart.org/art/1923.246

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Am Samstagabend stellte sich heraus, dass sich die Arbeit am Artikel gelohnt hatte. Es »stand etwas drin«, wie es im Jargon heißt (für »exklusive Informationen«). Umso schöner dann das Ausruhen danach. Man weiß, wovon man sich erholt.

Samstagabend einstündiger Spaziergang zu den Enten und Hasen der Ludwig-Erhard-Anlage. Die Abendluft tat gut wie ein kühles Bier. Ich hatte tagelang nicht mehr richtig geatmet. Also schon ein und aus, aber nicht durch. Mit dem Atmen kamen Ruhe, Hunger und Durst.

Heute noch einmal hinaus. Mit Joachim lief ich am Main entlang bis ins Sachsenhäuser Traditionslokal »Atschel«, das ist hessisch für »Elster«. Gleich stellte sich anheimelnde Ebbelwoistimmung ein: eine Greisin mit elsterschwarz gefärbtem Haar babbelte auf uns ein dahingehend, dass die Plätze, die uns von der Kellnerin an ihrem langen Holztisch zugewiesen worden waren, belegt seien, was die Kellnerin im Flüsterton als Greisenlatein entlarvte. Vom Nebentisch reichte uns eine junge Frau einen Bembel herüber – sie und ihr Freund vermochten die darin enthaltene Menge des ortstypischen Trunks nicht zu bewältigen. Dann kamen auch noch zwei Greise hinzu, von denen der eine ortskundig war, der andere fremd. Der Einheimische prahlte mit seiner Kenntnis der Fachausdrücke: »Isch nähm de Stich.« Der andere murmelte konsterniert, schön, er wisse nicht, was das sei. Der Einheimische, als löste er ein kompliziertes Rätsel souverän auf: »Bauchfleisch.«

Auf dem Heimweg blühten am Mainufer, da, wo der »Nizza« genannte Mittelmeergarten beginnt, schon die ersten Bäume. Einer hatte Blüten, die sich nach unten öffneten, zum Boden hin, als wollten sie es den noch wintermüde taumelnden ersten Bienen besonders leicht machen. Ein paar Meter weiter ein Teppich aus fliederfarbenen Krokussen, die ihre Kelche aufsperrten wie hungrige Küken den Schnabel. Noch wärmte die Sonne, aber die Wolken zogen schon auffällig schnell.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beelzebub playing a bagpipe shaped like a monk's head. Erhard Schön ~ ca.1530 Bibliothèque Infernale on FB

300 notes

·

View notes