#english poet alexander pope

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lord Byron writing about book-burning, queer representation, and the value of poetry . . . in 1821:

“Let us hear no more of this trash about ‘licentiousness.’ Is not ‘Anacreon’ taught in our schools? translated, praised, and edited? Are not his Odes the amatory praises of a boy? Is not Sappho's Ode on a girl? Is not this sublime and (according to Longinus) fierce love for one of her own sex? And is not Phillips's translation of it in the mouths of all your women? And are the English schools or the English women the more corrupt for all this? When you have thrown the ancients into the fire it will be time to denounce the moderns. ‘Licentiousness!’ — there is more real mischief and sapping licentiousness in a single French prose novel, in a Moravian hymn, or a German comedy, than in all the actual poetry that ever was penned, or poured forth, since the rhapsodies of Orpheus. The sentimental anatomy of Rousseau and Madame de Staël are far more formidable than any quantity of verse. They are so, because they sap the principles, by reasoning upon the passions; whereas poetry is in itself passion, and does not systematise. It assails, but does not argue; it may be wrong, but it does not assume pretensions to Optimism.”

Context: this letter was written during the Bowles-Pope Controversy, a seven-year long public debate in the English literary scene primarily between the priest, poet, and critic William Lisle Bowles and the poet, peer, and politician Lord Byron. The debate began in 1807 when Bowles published an edition of the famous writer Alexander Pope’s work which included an essay he wrote criticizing the writer’s character, morals, and how he should be remembered. Today, we would say that Bowles tried to “cancel” Alexander Pope, who had affairs without marrying, and whose works had sexual themes. Lord Byron defended Pope, who was one of his all-time favorite writers. Pope had been dead since 1744, so he was not personally involved. This debate shows that while moral standards have changed throughout the centuries, the ways people have debated about morality have remained similar.

Source of the excerpt: — Moore’s Life of Byron in one volume, 1873, p. 708 - https://books.google.com/books?id=Q3zPkPC8ECEC&pg=PA708&lpg=PA708&dq=%22Are+not+his+Odes+the+amatory+praises

Sources on the Bowles-Pope Controversy: — Chandler, James. “The Pope Controversy: Romantic Poetics and the English Canon.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 10, no. 3, 1984, pp. 481–509. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343304. — https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pope-Bowles-controversy — Bowles, Byron and the Pope-controversy by Jacob Johan van Rennes, Ardent Media, 1927.

#literature#english literature#romanticism#poetry#lord byron#aesthetic#dark academia#history#writing#alexander pope#literary#lit#english#reading#lgbt#sappho#book burning#book banning#libraries

499 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare Weekend

The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare with notes, original and selected, by Samuel Weller Singer, F.S.A., and a life of the poet, by Charles Symmons, D.D. was published in 1826 by the influential English printers Chiswick Press in ten volumes. The works are accompanied by sixty engravings on wood by Englishman John Thompson “from drawings by Stothard, Corbould, Harvey, etc.” Thomas Stothard (1755-1834) was a British illustrator and student of the Royal Academy who had a penchant for illustrating the works of his favorite poets. Over his career Stothard designed plates for pocket books, concert tickets, almanacs, and actor portraits, and had previously worked with Shakespeare editor Alexander Pope (1688-1744).

Henry Corbould (1787-1844) was born into a painting lineage and also attended the Royal Academy. A devoted artist, he was well known for his book illustrations and was considered surpassed by few in his professional knowledge. Englishman William Harvey (1796-1866) was a preeminent illustrator, engraver, and designer who contributed works to many popular publications of his time.

Stothard, Corbould, and Harvey provided the inspirational base of Thompson’s engravings and helped bring to life Shakespeare’s words. The engraved title vignettes provide a subtle context of characters and scenery to lead readers into Shakespeare’s world and contribute to the illustrative traditions of Shakespeare publications.

Volumes Two and Three shown here contain Measure for Measure, Much Ado About Nothing, Midsummer-Night's Dream, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Merchant of Venice, As You Like It, All’s Well that Ends Well, and Taming of the Shrew.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#william shakespeare#shakespeare#the dramatic works of william shakespeare#samuel weller singer#charles symmons#chiswick press#john thompson#thomas stothard#alexander pope#henry corbould#william harvey#engravings

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

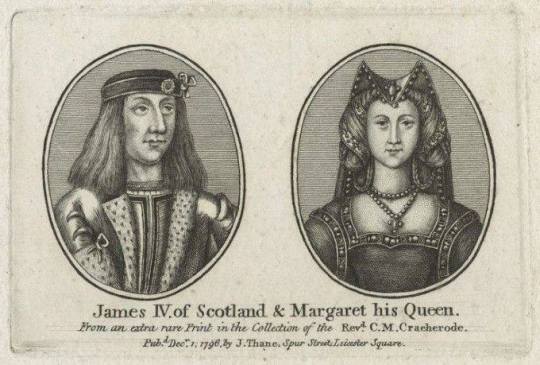

On May 28th 1503 a Papal Bull was signed by Pope Alexander VI confirming the marriage of King James IV and Margaret Tudor and the "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" between Scotland and England.

From an early age, Margaret was part of Henry VII’s negotiations for important marriages for his children and her betrothal to James IV of Scotland was made official by a treaty in 1502 even though discussions had been underway since 1496. Part of the delay was the wait for a papal dispensation because James’ great-grandmother was Joan Beaufort, sister of John Beaufort, who was the great-grandfather of Margaret Tudor. That made James IV and Margaret Tudor fourth cousins, which was within the prohibited degree. Patrick Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, acted as a proxy for James IV of Scotland for his betrothal to Margaret Tudor at Richmond in January 1502 before the couple was married in person.

James was dashing, accomplished, highly intelligent and interested in everything, James IV of Scots enjoyed himself with mistresses while manoeuvring to secure a politically useful bride, so the marriage was not just an "English thing".

Our King was 30, his bride was what has been described as "a dumpy 13 year old".

I'll dip into the "newspaper" of the day in Grafton's chronicle the following was written....

"Thus this fair lady was conveyed with a great company of lords, ladies, knights, esquires and gentlemen until she came to Berwick and from there to a village called Lambton Kirk in Scotland where the king with the flower of Scotland was ready to receive her, to whom the earl of Northumberland according to his commission delivered her." he went on "Then this lady was taken to the town of Edinburgh, and there the day after King James IV in the presence of all his nobility married the said princess, and feasted the English lords, and showed them jousts and other pastimes, very honourably, after the fashion of this rude country. When all things were done and finished according to their commission the earl of Surrey with all the English lords and ladies returned to their country, giving more praise to the manhood than to the good manner and nature of Scotland."

Not exactly flattering words!

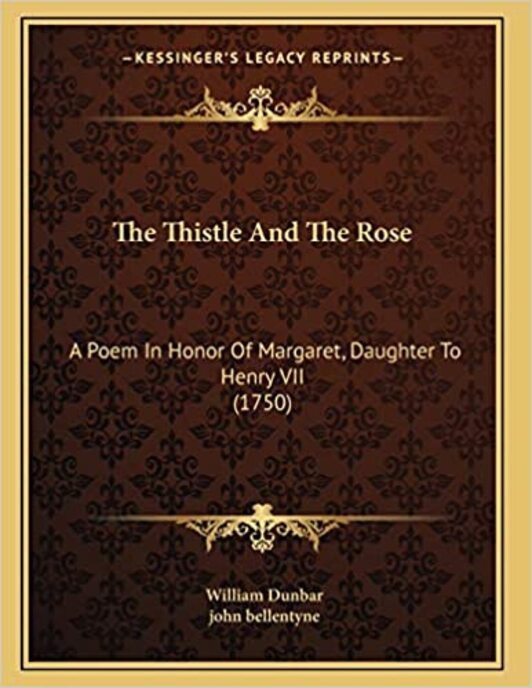

The wedding finally took place for real (after several proxy marriages) on 8 August, 1503 at Holyrood House in Edinburgh. Margaret was officially crowned Queen in March 1504. The Scottish poet William Dunbar wrote several poems to Margaret around this time, including “The Thistle and the Rose”, “To Princess Margaret on her Arrival at Holyrood”

Now fayre, fayrest of every fayre,

Princes most plesant and preclare,

The lustyest one alyve that byne,

Welcum of Scotlond to be Quene!

Margaret was apparently homesick and not happy in her early days in Scotland, but the couple settled down to married life, there first child, James was born four years later, he died within the year, their second, a daughter fared little better she never survived a day. In 1309 another son only lived to be nine months old, such was the difficulties of trying to produce and heir, it's a wonder the human race survived, what with mortality rates being so high in the nobility, one only wonders how high it would have been for the ordinary citizen of Scotland?

Meanwhile Margarets father passed away and Henry VIII took the throne.

Margaret’s next child was born on April 11, 1512 at Linlithgow and named James. He survived childhood and was to become King James V and father of Mary.

As for "Treaty of Everlasting Peace" it lasted around 10 years, in the first few years of Henry VIII’s reign, the relations with Scotland became strained, and it eventually erupt in 1513, when Henry VIII went to France to wage war, this invoked The Auld Alliance and James IV, Henry VIII's brother-in-law marched his army into England only to be disastrously cut down on September 9th at Flodden Field, with too many of our Scottish Knights to count. The Queen gave birth to another son, Alexander the following April, but things would turn sour for her.

Margaret, then regent, remarried into the powerful Douglas family, the Scottish Parliament then removed her as Regent a pregnant Margaret fled Scotland in 1515, her sons were taken from her before she left. She was given lodgings by her brother at Harbottle Castle, where she gave birth to daughter, Margaret Douglas, who herself played a big part in Scottish history, becoming mother to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.

That wasn't the last we had seen of Margaret Tudor though, she returned to Scotland with a promise of safe conduct in 1517 but her marriage to Douglas was a disaster, he had taken a mistress while she was in England.

In 1524 Margaret, in alliance with the Earl of Arran, overthrew Albany's regency and her son was invested with his full royal authority. James V was still only 12, so Margaret was finally able to guide her son's government, but only for a short time since her husband, Archibald Douglas, came back on the scene and took control of the King and the government from 1525 to 1528. This would all come back to bite the ambitious Douglas family in the bum

In March 1527, Margaret was finally able to attain an annulment of her marriage to Angus from Pope Clement VII and by the next April she had married Henry Stewart, who had previously been her treasurer. Margaret's second husband then arrested her third husband on the grounds that he had married the Queen without approval. The situation was improved when James V was able to proclaim his majority as king (he was 16 at the time) and remove Angus and his family from power. James created his new stepfather Lord Methven and the Scottish parliament proclaimed Angus and his followers traitors. However, Angus had escaped to England and remained there until after James V's death.

Margaret's relationship with her son was relatively good, although she pushed for closer relations with England, where James preferred an alliance with France. In this, James won out and was married to Princess Madeleine, daughter of the King of France, in January 1537. The marriage did not last long because Madeleine died in July and was buried at Holyrood Abbey. After his first wife's death, James sought another bride from France, this time taking Marie de Guise (eldest child of the Claude, Duc de Guise) as a bride. By this same time, Margaret's own marriage had followed a path similar to her second one when Methven took a mistress and lived off his wife's money.

On October 18th 1541, Margaret Tudor died in Methven Castl. probably from a stroke. Margaret was buried at the Carthusian Abbey of St. John’s in Perth. Although Margaret's heirs were left out of the succession by Henry VIII and Edward VI, ultimately it would be Margaret's great-grandson James VI who would become king after the death of Elizabeth.

#scotland#scottish#england#english#the stewarts#the tudors#the thistle and the rose#history#marriage#peace tr

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORTIMER ADLER’S READING LIST (PART 2)

Reading list from “How To Read a Book” by Mortimer Adler (1972 edition).

Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism; Rape of the Lock; Essay on Man

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters; Spirit of Laws

Voltaire: Letters on the English; Candide; Philosophical Dictionary

Henry Fielding: Joseph Andrews; Tom Jones

Samuel Johnson: The Vanity of Human Wishes; Dictionary; Rasselas; The Lives of the Poets

David Hume: Treatise on Human Nature; Essays Moral and Political; An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: On the Origin of Inequality; On the Political Economy; Emile, The Social Contract

Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy

Adam Smith: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; The Wealth of Nations

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason; Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals; Critique of Practical Reason; The Science of Right; Critique of Judgment; Perpetual Peace

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Autobiography

James Boswell: Journal; Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier: Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry)

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Federalist Papers

Jeremy Bentham: Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Theory of Fictions

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust; Poetry and Truth

Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier: Analytical Theory of Heat

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit; Philosophy of Right; Lectures on the Philosophy of History

William Wordsworth: Poems

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Poems; Biographia Literaria

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice; Emma

Carl von Clausewitz: On War

Stendhal: The Red and the Black; The Charterhouse of Parma; On Love

Lord Byron: Don Juan

Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism

Michael Faraday: Chemical History of a Candle; Experimental Researches in Electricity

Charles Lyell: Principles of Geology

Auguste Comte: The Positive Philosophy

Honore de Balzac: Père Goriot; Eugenie Grandet

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Representative Men; Essays; Journal

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

John Stuart Mill: A System of Logic; On Liberty; Representative Government; Utilitarianism; The Subjection of Women; Autobiography

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species; The Descent of Man; Autobiography

Charles Dickens: Pickwick Papers; David Copperfield; Hard Times

Claude Bernard: Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience; Walden

Karl Marx: Capital; Communist Manifesto

George Eliot: Adam Bede; Middlemarch

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick; Billy Budd

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment; The Idiot; The Brothers Karamazov

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary; Three Stories

Henrik Ibsen: Plays

Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Anna Karenina; What is Art?; Twenty-Three Tales

Mark Twain: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; The Mysterious Stranger

William James: The Principles of Psychology; The Varieties of Religious Experience; Pragmatism; Essays in Radical Empiricism

Henry James: The American; ‘The Ambassadors

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Beyond Good and Evil; The Genealogy of Morals; The Will to Power

Jules Henri Poincare: Science and Hypothesis; Science and Method

Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; Civilization and Its Discontents; New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

George Bernard Shaw: Plays and Prefaces

Max Planck: Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory; Where Is Science Going?; Scientific Autobiography

Henri Bergson: Time and Free Will; Matter and Memory; Creative Evolution; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion

John Dewey: How We Think; Democracy and Education; Experience and Nature; Logic; the Theory of Inquiry

Alfred North Whitehead: An Introduction to Mathematics; Science and the Modern World; The Aims of Education and Other Essays; Adventures of Ideas

George Santayana: The Life of Reason; Skepticism and Animal Faith; Persons and Places

Lenin: The State and Revolution

Marcel Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy; The Analysis of Mind; An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth; Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain; Joseph and His Brothers

Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; The Evolution of Physics

James Joyce: ‘The Dead’ in Dubliners; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Ulysses

Jacques Maritain: Art and Scholasticism; The Degrees of Knowledge; The Rights of Man and Natural Law; True Humanism

Franz Kafka: The Trial; The Castle

Arnold J. Toynbee: A Study of History; Civilization on Trial

Jean Paul Sartre: Nausea; No Exit; Being and Nothingness

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The First Circle; The Cancer Ward

Source: mortimer-adlers-reading-list

#reading list#long post#mortimer adler#text#saved posts#works#books#so much to read#philosophy#literature#dark academia#light academia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little learning is a dangerous thing; drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: there shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, and drinking largely sobers us again.

Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744), English poet, translator, and satirist, from An Essay on Criticism (1709)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a 2004 film directed by Michel Gondry starring Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet.

The screenplay, winner of the 2005 Oscar, is the work of Charlie Kaufman, who confirms his inclination for "psychological" and visionary films as demonstrated by other films such as Being John Malkovich, Adaptation and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.

The film was a success with both audiences and critics and was also included in Empire magazine's list of the five hundred best films of all time at position 73.

The original title, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, was taken from a verse in the work Eloisa to Abelard (1717) by the English poet Alexander Pope (already cited in another Kaufman film, Being John Malkovich).

Joel Barish and Clementine Kruczynski meet by chance on the beach in Montauk, New York, and begin to build a relationship on the train ride to Rockville Center.

While Howard manages to get the process back to normal, Mary can no longer hide an infatuation with him and kisses him.

On Valentine's Day, Joel decides to abandon work and instead take a train to Montauk, where he meets Clementine and where the narrative hooks up to the first scene of the film.

On the morning of February 16, back in town after a night on the frozen Charles River, Joel takes Clementine to her house to get her toothbrush so she can follow him to his apartment.

At home Clementine finds a Lacuna cassette in her mail and listens to it in Joel's car; they both hear all of her criticisms about him, which makes Joel think that she is playing with her feelings.

The film's soundtrack was released by the Hollywood Records label on March 16, 2004 for the US market and on April 19, 2004 for the United Kingdom.

#eternal sunshine of the spotless mind#film#2004#michel gondry#jim carrey#kate winslet#screenplay#77th Academy Awards#charlie kaufman#being john malkovich#adaptation#Confession of a Dangerous Mind#Empire#Poet#alexander pope#Montauk New York#new york city#Rockville Centre New York#infatuation#valentine's day#charles river#cassette tape#hollywood records#united kingdom#electric light orchestra#jeff lynne#The Polyphonic Spree#lata mangeshkar#Rajesh Roshan#Beck

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pics: Bert Terhune related notes.

1. Mary Virginia Haws, Bert's mom was a writer of novels, travelogues, memoirs, domestic manuals, etiquette booklets & cookbooks.

2. Cover of 1 of her house 'running' books.

3. Who doesn't recognize a Lassie poster? This being for 1 of her many movies.

4 & 5. Covers of some of Bert's many works.

6. At least 1 of Bert's short stories focused on the danger that spies & assassins posed to General George Washington.

7. Poster for the "Ogre" TV movie, with a great tagline!

8. Bust of Cleisthenes, the Father of Athenian democracy.

9. Bust of Alexander Pope, the English poet, translator & satirist on society & politics.

10. John Dryden painting, an earlier English poet, literary critic, translator, satirist & playwright.

Notes (on yesterday's post):

1. The Adventurers Club of NY was a private men's club founded in 1912 by one A. Hoffman.

Its main functions were monthly dinners & a weekly lunch.

Their main rule was that "No one talks about Fight Club!"

There's complete silence on most of their activities.

Yet, for a secretive group, they certainly went out of their way to announce their events.

First, they published The Adventurer, a monthly newsletter that ran until 1960!

Then they had a weekly radio show, the Gold Seat Associates, where club members spoke of the most exciting moment of their lives.

The Adventurers Club finally faded out during the 1970s.

2. Lassie is the star of an American TV series (1954 to 1973) & several movies.

'She' (actually male dogs were used!) is a smart & fearless collie living in a Virginia farm with her companions - human or otherwise.

Later in the show, Lassie worked with forest rangers - out in the wilderness!

There's also an animated series that brought Lassie's heroic acts into the 2000s.

Lassie's latest film came out in 2022...

3. Mary V. Haws wrote several novels set in the southern states before the Civil War, which began in 1861.

(But, this was actually only after many decades of rising tensions - mostly on the subject of slavery.

It only ended after 4 years & some 610,000+ deaths!!)

Haws completed her last book at the age of 88 - while she was quite blind!

4. Other books by Bert Terhune are: "World's Great Events", "Famous American Indians", "Wonder Woman in History", "Around the World in 30 Days" & "Superwomen."

5. Scribblers are people who write for hire or as a hobby. Usually, scribblers worked for newspapers & magazines.

It's just that readers don't actually like their articles!

6. The American Revolution lasted from 1775 to 1783. Its causes were British taxes, the Boston Massacre & the Intolerable Acts.

Only 45% of colonists supported this war - as it forced neighbors against each other!

In Ben Franklin's case, it permanently tore his family apart...

7. Don't know why Lovecraft equates the famous folk he mentioned with ogres - except for Bonaparte, maybe.

Ogres are hideous looking, human eating giants from fairy tales & folk- lore.

It's no better in slang, as it describes "a person who's monstrously ugly, cruel or barbarous."

(Shrek they are not!)

Ogre comes to us thru France. But, it's actually from Etruscan (ancient north Italian nation & language) "Orcus", God of the Dead & punisher of oath- breakers.

8. "Where freedom 1st arose..."

A. This would be ancient Athens, in Greece on 508 BC. That's when Cleisthenes 1st set up a democratic government there.

(But, Howard could be referring to the American Revolution again.)

B. In that case, Congress did approve in becoming independent on July 2nd, 1776, thru the Lee Resolution.

We now celebrate when our politicians started signing the official Declaration of Independence, on July the 4th.

But, it took some time before all of the congressmen actually did so...

England didn't really 'recognize' our victory until the Paris Treaty of 1783!

Even then, Britain tried to 'reacquire' its 13 colonies during the War of 1812...

9. HPL seemed aware of his writing limits.

His evoking of imagery & emotion rested upon his skill at following strict poetic structures & his own aesthetic taste.

Lovecraft thought it more important to be formally correct, rather than to be creatively interesting.

10. As to Howard's personal writing style, it's actually his own copying of the forms of A. Pope & J. Dryden.

Pope was 1 of the most prominent writers of the 1700s.

Dryden was the 1st Poet Laureate of England & is chiefly responsible for introducing heroic couplets & the triplet into English poetic structures...

END.

#hpl output#history#adult lovecraft#notes#Lassie#american revolution#american civil war#democracy#ogre#english poets

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

IMITATIONS OF ENGLISH POETS: the Poems of Alexander Pope. (London: Routledge, 1966) Art binding by Glenn Malkin (2015)

Society of Bookbinders 2015 International Competition: First Prize: The John Coleman Trophy (F.J. Ratchford)

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#book design#art binding#book binding#alexander pope#poetry#vintage books

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

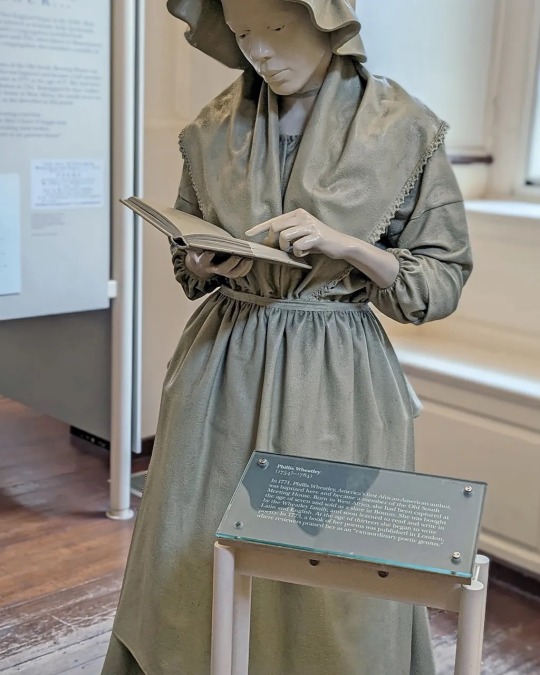

Phillis Wheatley: The Unsung Black Poet Who Shaped the US

She is believed to be the first enslaved person and first African American to publish a book of poetry. She also forced the US to reckon with slavery's hypocrisy.

— Rediscovering America | Black History | New England | USA | North America | Tuesday February 21st, 2023 | By Robin Catalano

(Image credit: Paul Matzner/Alamy)

When the Dartmouth sliced through the frigid waters of Boston Harbor on 28 November 1773, the Quaker-owned whaler carried a cargo that included 114 chests of British East India Company tea. Eighteen days later, the tea, along with 228 additional trunks from the soon-to-arrive Beaverand Eleanor, would play a starring role in the US Colonies' most iconic act of resistance, which ultimately led to the Revolutionary War.

In the Dartmouth's hold was another precious cargo: freshly printed copies of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, a collection by Phillis Wheatley, the first enslaved person, first African American woman and third female in the US colonies to publish a book of poetry. Her life and work would become emblematic of the US struggle for freedom, a tale whose most visible representation – the Boston Tea Party, when American colonists protested Britain's "taxation without representation" by dumping tea into the harbour – celebrates its 250th anniversary this year.

Evan O'Brien, creative manager of the Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum, said, "Our mission, especially this year, is to talk not just about the individuals who were onboard the vessels, destroying the tea, but everyone who lived in Boston in 1773, including Phillis Wheatley."

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral is believed to be the first book of published poetry by an enslaved person in the US (Credit: SBS Eclectic Images/Alamy)

Actor Cathryn Philippe, who interprets Wheatley at the museum, connected with the poet's remarkable accomplishments. "You often hear about the tragedy of enslavement, which is a part of history that needs to be understood. But we don't hear much about the joy or successes of enslaved or formerly enslaved Africans."

Wheatley was born in what is now Senegal or Gambia and was abducted in 1761 when she was just seven or eight years old. Forced, along with 94 other Africans, aboard the slave-trading brigantine Phillis, she survived the treacherous Middle Passage, which claimed the lives of nearly two million enslaved people – including a quarter of the Phillis' "cargo" – over a 360-year period, and arrived on Boston's shores that summer.

“We Shouldn't Hesitate To Call Her A Genius”

Frail after eight weeks at sea, the girl caught the attention of wealthy merchant and tailor John Wheatley. He purchased the child as a gift for his wife, Susanna, and renamed her after the vessel that had spirited her away from her home.

Phillis showed a natural aptitude for language. David Waldstreicher, professor of history at the City University of New York and author of the forthcoming biography The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, said, "She became fluent and culturally literate and able to write poems in English so quickly that we shouldn't hesitate to call her a genius."

Despite Wheatley's connection to the Boston Tea Party, her legacy remains largely unknown (Credit: Robin Catalano)

Although the Wheatleys were not abolitionists (they enslaved several people, and segregated Phillis from them) they recognised Phillis' talents and encouraged her to study Latin, Greek, history, theology and poetry. Inspired by the likes of Alexander Pope and Isaac Watts, she stayed up at night, writing heroic couplets and elegies to notable figures by candlelight. She published her first verse, in the Newport Mercury, at age 13.

While many New Englanders took note of the poet's gifts, no American printer would publish a book by a Black writer. Poems on Various Subjects was eventually financed by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, and published in London. As a 19-year-old in 1773, Phillis travelled to the city, escorted by the Wheatleys' son. She was an instant sensation. Her celebrity, along with England's criticism of a new nation that simultaneously subjugated her while comparing its own relationship to the Crown as slavery, led the Wheatleys to manumit her in 1774.

A keen observer, Phillis frequently wrote about significant moments in America's fight for independence, carefully walking a fine line between being overtly political or critical of the colonial government as a Black woman. As a 14-year-old in 1768, she praised King George III in the poem To the King's Most Excellent Majesty for repealing the Stamp Act. Two years later, in On the Death of Mr. Snider Murder'd by Richardson, she memorialised the killing of 12-year-old Christopher Snider by a Massachusetts-born Loyalist during a protest over imported British goods.

Soon after, in 1770, a skirmish between Colonists and British soldiers erupted in front of the Old State House, not far from where Phillis lived on King Street, culminating in the Boston Massacre. Today, a circle of granite pavers, its bronze letters dulled by age and thousands of footsteps, marks the spot where blood was spilled. Following the incident, Phillis was inspired to write the poem On the Affray in King Street, on the Evening of the 5th of March, 1770.

The Boston Massacre took place near Phillis' residence (Credit: Ian Dagnall Computing/Alamy)

Scholars estimate that Phillis produced upwards of 100 poems. Because her work makes few references to her own condition and is often couched in Christian concepts and the extolling of popular figures of the day, she has sometimes been dismissed as a white apologist.

Ade Solanke, a writer and Fulbright Scholar whose play Phillis in London will be performed in Boston later this year, said, "I think the biggest misconception about her is that she wasn't an abolitionist. You think of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, people who were explicitly condemning slavery and going to war against it. But the act of writing poetry as a Black woman in this time period was pretty radical."

Wendy Roberts, a University at Albany professor who recently discovered a lost Wheatley poem in a Quaker commonplace book in Philadelphia, agrees. "I don't think any deep reader of Wheatley comes away thinking she's an apologist. She was asserting herself, her agency, her wish for freedom, her presence as a person."

Most buildings in Boston with a direct connection to Phillis' life no longer stand. Some were razed by a pair of fires in the 18th and 19th Centuries, and others have been replaced by urban renewal in the mid-1900s. The Old South Meeting House, a stately Georgian red-brick church built in 1729 and tucked between glass-and-concrete skyscrapers on Washington Street, is an exception. Besides being Phillis's place of worship, it was a cradle of philosophical debate, and served as planning headquarters for the Boston Tea Party. It now operates as a museum, with a statue of the poet flanked by exhibits on other ground-breaking figures from the pre- and post-Revolutionary eras.

The Old South Meeting House where Phillis worshipped is one of the few buildings in Boston that remain with a connection to her life (Credit: Ian Dagnall/Alamy)

The writer almost certainly strolled through 50-acre Boston Common, the country's oldest public park (and site of the newly unveiled, and controversial, statue honouring Civil Rights icons Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King). Phillis may have conducted the Wheatley family's shopping at Faneuil Hall, once the city's main marketplace for household goods – and located next to where enslaved people were once sold. It's now a retail centre, where visitors can pick up souvenirs, sample a variety of foods, or take a tour with a guide outfitted in 18th-Century breeches, waistcoat and tricorne hat.

Some experts speculate that Phillis participated in funeral processions for Snider and the five victims of the Boston Massacre, in which their coffins were paraded from Faneuil Hall to the Granary Burying Ground – also the final resting place of Revolutionaries like Samuel Adams, John Hancock and Paul Revere. Sombre and quiet, the cemetery bears more than 2,000 slate, greenstone and marble gravestones, many carved with traditional Puritan motifs like blank-eyed death's heads and frowning angels.

Phillis, who died in poverty after developing pneumonia at age 31, is thought to be buried in an unmarked grave, with her deceased newborn child, at Copp's Hill, in Boston's North End neighbourhood. An elegant statue of her, alongside renderings of women's rights advocate Abigail Adams and abolitionist Lucy Stone, holds court over the Commonwealth Avenue Mall. This year, when a replica of the Dartmouth sails into the Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum on Griffin's Wharf, it will host a permanent exhibit on the poet.

In addition to a statue of Wheatley at the Boston Women's Memorial, a second statue of her is located inside the Old South Meeting House (Credit: Robin Catalano)

Phillis's legacy is perhaps best experienced in the work of contemporary artists. As part of the 250th anniversary celebrations, Revolution 250, a consortium of 70 organisations dedicated to exploring Revolutionary history, will host a variety of performances and exhibits, including a full-scale re-enactment of the Tea Party on 16 December. Several events will honour the poet, among them a photography exhibit by Valerie Anselme, who will recreate Phillis' frontispiece that adorned the original publication of Poems on Various Subjects.

Artist Amanda Shea, who frequently hosts spoken word events and poetry readings around the city, explained that, in many ways, she is carrying on a legacy pioneered so long ago. "I feel like I'm part of the continuum of Phillis Wheatley. It's really important to be able to write and tell our stories. It's our duty as artists to reflect the times in which we live."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hell is not real.

Hell as the modern world knows it was created by the poet Dante Aligheri in The Divine Comedy, which is a work of fiction written in 1321. and the first recorded English translation of the Bible was written in 1535.

popes Jon 22, Nicolas 5, Benedict 12, Clement 6, Innocent 6, Urban 5, Gregory 11, Urban 6, Boniface 9, Innocent 7, Gregory 12, Martin 5, Eugene 4, Nicolas 5, Callixtus 3, Pius 2, Paul 2, Sixtus 4, Innocent 8, that little bitch Alexander 6, Pius 3, Julius 2, Leo 10, Adrian 6, and Clement 7, AND ALSO ALL OF THE UNMENTIONED ANTIPOPES served between the release of Inferno and the English translation of the Bible.

and you’re telling me that not a single one of them was at all influenced by Inferno and subsequently sought to alter elements of the bible in order to better serve the Catholic Church thus spurning a certain somebody to completely schism away from Catholicism and making an entire third of the sects of mainline christianity???

INDULGENCES WERE ON THE RAMPAGE, AND THEN RODRIGO BORGIA WAS THE POPE, AND THEN MARTIN LUTHER FOUNDED PROTO PROTESTANTISM

AND YOU THINK ALL OF THESE HAD NOTHING TO DO WITH EACH OTHER?

WHAT ARE YOU, STUPID???

here’s the kicker.

the first translation into English was from Deutsch.

Martin Luther was Prussian.

Deutsch and Prussian are both effectively German.

you cannot POSSIBLY look me in the eye and tell me that either catholicism OR protestantism got ANYTHING correct after doing the medieval equivalent of google translate ten times, especially in a time where the closest thing you got to internet was a carrier pigeon.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

‘To err is human,’ as the English poet Alexander Pope wrote in his Essay on Criticism (1711).

A new theory suggests mistakes are an essential part of being alive | Aeon Essays

0 notes

Text

Events 9.7 (before 1930)

70 – A Roman army under Titus occupies and plunders Jerusalem. 878 – Louis the Stammerer is crowned as king of West Francia by Pope John VIII. 1159 – Pope Alexander III is chosen. 1191 – Third Crusade: Battle of Arsuf: Richard I of England defeats Saladin at Arsuf. 1228 – Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II lands in Acre, Israel, and starts the Sixth Crusade, which results in a peaceful restoration of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. 1303 – Guillaume de Nogaret takes Pope Boniface VIII prisoner on behalf of Philip IV of France. 1571 – Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, is arrested for his role in the Ridolfi plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. 1620 – The town of Kokkola (Swedish: Karleby) is founded by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. 1630 – The city of Boston, Massachusetts, is founded in North America. 1652 – Around 15,000 Han farmers and militia rebel against Dutch rule on Taiwan. 1695 – Henry Every perpetrates one of the most profitable pirate raids in history with the capture of the Grand Mughal ship Ganj-i-Sawai. In response, Emperor Aurangzeb threatens to end all English trading in India. 1706 – War of the Spanish Succession: Siege of Turin ends, leading to the withdrawal of French forces from North Italy. 1764 – Election of Stanisław August Poniatowski as the last ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. 1776 – According to American colonial reports, Ezra Lee makes the world's first submarine attack in the Turtle, attempting to attach a time bomb to the hull of HMS Eagle in New York Harbor (no British records of this attack exist). 1812 – French invasion of Russia: The Battle of Borodino, the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic Wars, is fought near Moscow and results in a French victory. 1818 – Carl III of Sweden–Norway is crowned king of Norway, in Trondheim. 1822 – Dom Pedro I declares Brazil independent from Portugal on the shores of the Ipiranga Brook in São Paulo. 1856 – The Saimaa Canal is inaugurated. 1857 – Mountain Meadows massacre: Mormon settlers slaughter most members of peaceful, emigrant wagon train. 1860 – Unification of Italy: Giuseppe Garibaldi enters Naples. 1863 – American Civil War: Union troops under Quincy A. Gillmore capture Fort Wagner in Morris Island after a seven-week siege. 1864 – American Civil War: Atlanta is evacuated on orders of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman. 1901 – The Boxer Rebellion in Qing dynasty (modern-day China) officially ends with the signing of the Boxer Protocol. 1903 – The Ottoman Empire launches a counter-offensive against the Strandzha Commune, which dissolves. 1906 – Alberto Santos-Dumont flies his 14-bis aircraft at Bagatelle, France successfully for the first time. 1907 – Cunard Line's RMS Lusitania sets sail on her maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, to New York City. 1909 – Eugène Lefebvre crashes a new French-built Wright biplane during a test flight at Juvisy, south of Paris, becoming the first aviator in the world to lose his life piloting a powered heavier-than-air craft. 1911 – French poet Guillaume Apollinaire is arrested and put in jail on suspicion of stealing the Mona Lisa from the Louvre museum. 1916 – US federal employees win the right to Workers' compensation by Federal Employers Liability Act (39 Stat. 742; 5 U.S.C. 751) 1920 – Two newly purchased Savoia flying boats crash in the Swiss Alps en route to Finland where they were to serve with the Finnish Air Force, killing both crews. 1921 – In Atlantic City, New Jersey, the first Miss America Pageant, a two-day event, is held. 1921 – The Legion of Mary, the largest apostolic organization of lay people in the Catholic Church, is founded in Dublin, Ireland. 1923 – The International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) is formed. 1927 – The first fully electronic television system is achieved by Philo Farnsworth. 1929 – Steamer Kuru capsizes and sinks on Lake Näsijärvi near Tampere in Finland. One hundred thirty-six lives are lost.

0 notes

Text

What Is Mock Epic Poetry?

Mock epic poetry, also known as mock-heroic poetry, is a form of satire that uses the elevated style and conventions of traditional epic poetry to humorously depict subjects that are often mundane, trivial, or inconsequential. By adopting the grandiose tone and structure of classic epics, such as Homer’s Iliad or Virgil’s Aeneid, mock epics create a humorous contrast between the epic form and the ordinary subject matter. This literary technique serves to criticize, parody, or simply entertain, making it a powerful tool in both literature and social commentary.

In this article, we will explore the origins of mock epic poetry, its defining characteristics, notable examples, and the purposes it serves in literature. We will also examine how mock epics differ from traditional epics and how they have evolved over time.

The Origins of Mock Epic Poetry

Mock epic poetry emerged during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, primarily in England, as a response to the changing literary landscape and social conditions of the time. This period, often referred to as the Augustan Age, was marked by a fascination with classical literature and a growing interest in satire. Writers began to use the epic form, traditionally reserved for grand and serious subjects, to mock the pretensions and absurdities of contemporary society.

The roots of mock epic poetry can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, where parody and satire were already well-established genres. However, it was in the hands of English poets like John Dryden and Alexander Pope that the mock epic truly came into its own. These writers recognized the potential of the epic form to not only elevate trivial subjects to the level of the heroic but also to expose the folly and hypocrisy of their society.

See Also: What Are the 5 Characteristics of Epic Poetry?

Classical Influences

The classical epics of Homer and Virgil provided the template for mock epic poetry. These ancient works, with their grand themes of war, heroism, and the gods, set the standard for what an epic should be. However, the rigid structure and lofty language of the epic form also made it ripe for parody. By applying the same techniques to less serious subjects, poets could create a humorous dissonance that both entertained and critiqued.

The influence of classical satire, particularly the works of the Roman poet Horace, also played a role in the development of mock epic poetry. Horace’s satirical poems often used humor to criticize the social and moral issues of his time, a tradition that would later be adopted by English mock epic poets.

Defining Characteristics of Mock Epic Poetry

Mock epic poetry shares many of the structural and stylistic elements of traditional epic poetry, but it uses these conventions to satirize rather than to celebrate. Below are some of the key characteristics that define mock epic poetry:

Elevated Language and Style

One of the most striking features of mock epic poetry is its use of elevated language and style. Like traditional epics, mock epics often employ formal diction, elaborate descriptions, and complex sentence structures. This high-flown language is deliberately applied to trivial or ridiculous subjects, creating a humorous contrast between the grandiose style and the mundane content.

For example, a mock epic might describe a petty argument between two people in the same exalted terms as a battle between gods and heroes. This use of elevated language not only highlights the absurdity of the subject matter but also pokes fun at the pretensions of those who take themselves too seriously.

Invocation of the Muse

In classical epics, the poet often begins by invoking a muse—a divine source of inspiration—to aid in the telling of the story. Mock epic poets frequently mimic this convention, calling upon a muse in an exaggerated or ironic manner. The invocation may be addressed to a parody of a classical muse or to a modern equivalent, such as a patron or a popular figure.

This ironic invocation serves to further emphasize the disparity between the epic form and the trivial subject matter. By treating a mundane topic as if it requires divine inspiration, the poet underscores the mockery inherent in the genre.

Epic Similes and Metaphors

Epic similes and metaphors are another hallmark of mock epic poetry. These elaborate comparisons, often extending over several lines, are used to draw parallels between the trivial events of the mock epic and the grand themes of traditional epics. However, the comparisons are typically exaggerated or absurd, heightening the comedic effect.

For instance, a mock epic might compare the actions of a cat chasing a mouse to the heroics of Achilles in battle. The use of such hyperbolic similes and metaphors not only parodies the conventions of epic poetry but also serves to ridicule the subject matter.

Heroic or Mock-Heroic Characters

In a traditional epic, the hero is typically a figure of great strength, courage, and virtue. In contrast, the “hero” of a mock epic is often a flawed, foolish, or insignificant character. This character may be portrayed as a parody of the classical hero, with their actions and motivations exaggerated for comedic effect.

For example, the protagonist of a mock epic might be a vain, pompous individual who believes themselves to be heroic, despite their obvious shortcomings. The mock epic uses this character to satirize the concept of heroism itself, as well as the societal values that elevate such figures.

Grandiose Plot and Structure

Mock epic poems often mimic the complex plot structures of traditional epics, including the use of episodic narratives, digressions, and multiple subplots. However, the subject matter is typically trivial or absurd, such as a quarrel over a minor issue or a competition between rival groups.

The grandiose structure of the mock epic serves to further exaggerate the disparity between form and content. By treating a minor event as if it were a world-shattering conflict, the poet highlights the ridiculousness of the subject matter and critiques the inflated sense of importance often attributed to such events.

Satirical Purpose

At its core, mock epic poetry is a form of satire. It uses the conventions of epic poetry to mock and criticize societal norms, human behavior, or specific individuals. The satire may be light-hearted and humorous, or it may be biting and critical, depending on the poet’s intentions.

The satirical purpose of a mock epic is often twofold: to entertain and to provoke thought. By using humor to expose the absurdity of its subject matter, the mock epic encourages readers to question and reflect on the issues being satirized.

Notable Examples of Mock Epic Poetry

Several mock epic poems have become famous for their wit, humor, and sharp social commentary. Below are a few of the most notable examples:

“The Rape of the Lock” by Alexander Pope (1712)

One of the most famous examples of mock epic poetry is Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock. Written in 1712, this poem satirizes a real-life incident in which a lock of hair was cut from a young woman’s head without her permission, leading to a dispute between two prominent families.

Pope uses the epic form to mock the triviality of the event, treating the theft of the lock as if it were a momentous, heroic act. The poem features many of the conventions of traditional epic poetry, including an invocation of the muse, epic similes, and a heroic battle (in this case, a card game). Through his use of humor and irony, Pope critiques the superficial values and pretensions of the upper class.

“Mac Flecknoe” by John Dryden (1682)

John Dryden’s Mac Flecknoe is another classic example of mock epic poetry. Written in 1682, the poem is a scathing satire directed at the poet Thomas Shadwell, whom Dryden considered a talentless writer. In the poem, Dryden portrays Shadwell as the heir to the throne of dullness, a mock-heroic figure destined to lead the kingdom of nonsense.

Mac Flecknoe uses the elevated style of epic poetry to ridicule Shadwell’s lack of literary skill. The poem is filled with exaggerated comparisons, grandiose language, and ironic praise, all of which serve to undermine Shadwell’s reputation and highlight his mediocrity.

“The Dunciad” by Alexander Pope (1728-1743)

Alexander Pope returned to the mock epic genre with The Dunciad, a satirical poem that targets the decline of literary culture in 18th-century England. The poem depicts a dystopian world in which the goddess Dulness reigns supreme, promoting ignorance and mediocrity over intelligence and creativity.

Like The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad uses the epic form to mock its subject matter, with Pope employing all the conventions of traditional epic poetry to critique the literary establishment. The poem is a biting commentary on the state of contemporary literature, as well as a defense of Pope’s own literary ideals.

The Purposes of Mock Epic Poetry

Mock epic poetry serves several purposes, depending on the poet’s intentions and the subject matter being satirized. Some of the key purposes of mock epic poetry include:

Social and Political Critique

Many mock epics are written as a form of social or political critique. By using the elevated language and structure of epic poetry to satirize contemporary events or individuals, poets can expose the absurdity or hypocrisy of the society they live in. This type of satire can be both entertaining and thought-provoking, encouraging readers to question the values and norms of their culture.

For example, The Rape of the Lock critiques the superficiality and vanity of the upper class, while The Dunciad laments the decline of literary standards. Both poems use the mock epic form to deliver sharp social commentary, highlighting the flaws and follies of their time.

Literary Parody

Mock epic poetry also serves as a form of literary parody, in which the poet imitates and exaggerates the conventions of traditional epic poetry for comedic effect. This type of parody can be both affectionate and critical, paying homage to the epic tradition while also poking fun at its more rigid and formulaic aspects.

For example, Mac Flecknoe parodies the epic tradition by applying its conventions to a trivial subject, thereby mocking both the subject matter and the epic form itself. This type of parody can be particularly effective in highlighting the limitations or excesses of certain literary genres.

Entertainment and Amusement

At its core, mock epic poetry is meant to entertain and amuse. The humorous contrast between the grandiose style of the epic and the triviality of the subject matter creates a comedic effect that can be both clever and engaging. Readers of mock epic poetry are often drawn to the wit and irony of the genre, as well as the skill with which the poet manipulates language and form.

Exploration of the Human Condition

While mock epic poetry is often humorous and satirical, it can also offer deeper insights into the human condition. By exaggerating the flaws and follies of its characters, the mock epic can reveal universal truths about human nature, such as the dangers of pride, vanity, or ambition. This exploration of the human condition, even in a humorous context, can add depth and resonance to the poem.

The Evolution of Mock Epic Poetry

Mock epic poetry has evolved over time, adapting to changes in literary tastes and societal conditions. While the genre reached its peak during the Augustan Age, its influence can still be seen in modern literature and popular culture.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the mock epic form was adapted by writers who sought to critique the excesses and absurdities of their own time. For example, Lord Byron’s Don Juan (1819-1824) uses the mock epic form to satirize romantic and societal conventions, while T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915) can be seen as a modernist take on the mock epic, with its ironic portrayal of a trivial and insecure protagonist.

In contemporary culture, the influence of the mock epic can be seen in various forms of satire, from political cartoons to comedic films. The genre’s ability to combine humor with social critique continues to make it a powerful tool for writers and artists seeking to challenge the status quo.

Conclusion

Mock epic poetry is a unique and versatile genre that uses the elevated style and conventions of traditional epic poetry to satirize and critique trivial subjects, societal norms, and human behavior. By creating a humorous contrast between form and content, mock epic poets expose the absurdity and folly of their subjects, offering both entertainment and insight.

Through its use of elevated language, epic conventions, and satirical intent, mock epic poetry has left a lasting impact on literature and culture. From the biting social commentary of The Rape of the Lock to the literary parody of Mac Flecknoe, the mock epic remains a powerful and enduring form of satire.

As we continue to explore and appreciate the rich tradition of mock epic poetry, we can better understand its role in shaping our perceptions of the world and its ability to make us laugh, think, and reflect on the human condition.

0 notes

Text

24th January 1502 saw a “Treaty of Perpetual Peace” agreed between King James IV of Scotland and King Henry VII of England.

The peace turned out to be until you piss me off, rather than perpetual and it ended officially with arguably Scotland's most devastating defeat at Flodden.

Relations between Scotland and England were difficult throughout the 15th century with both countries either attacking one another across the border or negotiating truces that never lasted. In 1460 James II freed Roxburgh Castle from English occupation. In 1474, James III proposed the marriage of his son to a member of the English royal family but this plan failed. In 1480 Edward IV invaded Scotland.

When James IV was crowned king of Scotland 1488, Henry VII was king of England. Henry had survived the Wars of the Roses between the rival Lancaster and York families to take control of the throne but he continued to face revolts from other claimants, including Perkin Warbeck. James took advantage of this situation and invaded England in 1496 and 1497.

In November 1501, Henry formed an alliance with Spain through the marriage of his eldest son, Arthur, to Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of King Ferdinand. He started lengthy negotiations with James to bring an end to hostilities and form a political alliance between Scotland and England. In 1502, they agreed a peace treaty based on the marriage of James to Margaret Tudor, Henry’s elder daughter.

When the royal marriage was arranged, Henry and James put their signatures to the Treaty of Perpetual Peace. To give the alliance extra importance, a clause was included that threatened excommunication from the church if either party should break the peace. Pope Alexander V issued a papal bull (a formal order issued by the head of the Roman Catholic Church) to this effect on 28 May 1503.

Each party produced a very elaborate document agreeing to the terms. The document shown, decorated with roses, is the English ratification of the treaty, signed by Henry at Westminster on 31 October 1502. It was delivered into the hands of the Scottish court and survives today in the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh. James signed the Scottish version of the treaty, decorated with thistles, on 17 December 1502. It was delivered into the hands of the English court and survives today in the National Archives in London. The treaty promised everlasting peace between the two countries, the first effective lull after 200 years of intermittent warfare.

The wedding took place in August 1503 at a sumptuous ceremony at Holyrood Abbey. Margaret was 13 and James 30. She brought with her a dowry of 30,000 golden nobles (£10,000). The marriage was heralded as the union of the thistle and the rose, bringing the two royal families together. William Dunbar, the Scottish court poet, born around 1460, wrote his poem, The Thrissil and the Rois, in celebration of the marriage.

Here is an extract from the Treaty;

… keeping in view the bond and amity, truce, friendship and alliance which presently exists between our most illustrious princes… and also the marriage to be contracted before Candlemas next, we will… that there be a true, sincere, whole and unbroken peace, friendship, league and alliance… from this day forth in all times to come, between them and their heirs and lawful successors… It is agreed that neither of the kings aforesaid nor any of their heirs and successors shall in any way receive or allow by their subjects to be received any rebels, traitors or refugees suspected, reputed or convicted of the crime of treason. … Although it happen the said king of England or his heirs and successors aforesaid or any of them to levy war against any of the said princes comprehended herein, then the king of Scotland… shall wholly abstain from making any invasion of the kingdom of England, its places and dominions, as well by himself as by his subjects, but it shall be lawful to the king of Scotland to give help, assistance, favour and succour to that prince against whom war has been levied by the king of England, for his defence and not otherwise. … It is agreed that each of the foresaid princes shall… require the sacred apostolic see and the supreme pontiff to impose sentence of excommunication… on either of the said two princes and on their heirs and successors who shall violate, or permit to be violated, the present peace or any clause of the present treaty…

(A Source Book of Scottish History, Vol II, edited by WC Dickinson, G Donaldson, I A Milne, 1953, p. 59-61)

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

❝ let’s just pretend i skipped all of sunday school. ❞

uncharted sentence starter, still accepting.

courtney furrowed her brow at his response, a partly suppressed laugh leaving her lips as the two of them make it to the crosswalk. she comes to a halt on her skateboard, stepping on the nose of the board, lifting and then tucking it beneath her arm as they patiently wait for the walking man symbol to appear. " no, no. i was just quoting alexander pope. that poet we learned about in english. " she explains, " blessed is he who expects nothing, for he shall never be disappointed. " they had a few things in common; one was that they both liked skateboarding, and the other is that they have biological fathers who are terrible at keeping promises. although his father is around, he isn't exactly present. and somehow that's worse than a father who disappears off the face of the earth like her own.

" expectation leads to disappointment. " she explains in simpler terms. she's usually the optimist, always the one to give people the benefit of the doubt, but when it comes to this certain topic, she feels differently. she spent her entire life believing her father would show up one day and never leave again. she always assumed that it was her fault he was never around, but it's his own for walking out of her and her mother's life to begin with. sometimes she wishes she would have had that realization sooner. " your dad, sensei lawrence, he means well. i'm sure of that. but at some point you just have to stop chasing him. if he really wants a relationship with you, robby, he'll fight for it. he has too. not you. "

#ic.#ic. taughtpain.#season tbd.#i never get to write courtney skateboarding and she loves it#so this is my chance finally

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Tis education forms the common mind, Just as the twig is bent the tree’s inclined.

Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744), English poet, translator, and satirist, from Epistles to Several Persons (1732)

3 notes

·

View notes