#edmund duke of somerset

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alright everyone here’s a very stupid question!

Also yes. I have personally read fanfiction about every single one of these figures listed in the poll.

#the wars of the roses#war of the roses#wars of the roses#tudors#the tudors#tudor england#historical polls#Polls#tumblr poll#tumblr polls#Henry V#humphrey duke of gloucester#richard duke of york#richard plantagenet#Edmund duke of Somerset#Edmund Beaufort#Henry VI#margaret of anjou#edward iv#George Plantagenet#george duke of clarence#richard iii#Henry viii#thomas cromwell#thomas more

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir John Wenlock's Castle of Someries

Sir John Wenlock was a known side-swapper during the Wars of the Roses. Although not as infamous as Thomas Stanley, Wenlock also frequently changed allegiances, starting out as a Lancastrian, then becoming a Yorkist, then a Warwick supporter and then back to being a Lancastrian again. He fought for the House of Lancaster at Tewkesbury and was killed in the field, some say by his own commander,…

View On WordPress

#Edmund Duke of Somerset#Gatehouses#Luton#Luton Airport#Richard of Warwick#ruins#Sir John Wenlock#Someries Castle#Tewkesbury#treachery#Wars of the Roses

0 notes

Text

Every time I think about how Colin Richmond talks about Catherine of Valois in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, I want to stab something.

Like, what the fuck is this shit:

It seems unlikely that Edmund Beaufort would have taken so great a political risk as getting the queen dowager with child, but he was a dashing young man (recently released from prison) as well as a Beaufort, and Catherine, who had fulfilled the only role open to her by immediately producing a son for the Lancastrian dynasty, was a lonely Frenchwoman in England, and at thirty or thereabouts was, the rumour ran, oversexed. Many stranger things have happened, and the idea of renaming sixteenth-century England is an appealing one.

It's sexism all the way down.

Edmund Beaufort is depicted as an ideal man. He's mature and responsible, concerned with the political ramifications of knocking up the dowager queen. But also dashing, young and presumably very handsome.

In contrast, Catherine is depicted as the bored, lascivious older woman with nothing in her life but indulging her nymphomania, implied to be preying on the young, dashing Beaufort, and uncaring of the risks of pregnancy. Richmond doubly confines her in misogynistic rhetoric. Her only role, in his mind, was her reproductive quality that is now rendered obsolete, which renders her obsolete, so she fills her days with sex and, as she reaches "thirty or thereabouts" is cast as a succubus-like figure who tempts and consumes younger men.

Catherine's "oversexed" reputation rests entirely on the fact she married a man far beneath her and the rumours relating to the possibility of her marrying Beaufort. We don't know that Catherine wanted to marry Beaufort or, if she did, that she did so on the basis of her personal desires or for political reasons. Beaufort and Catherine were actually very close in age for a medieval couple, Catherine was about four years older than Beaufort. Furthermore, when their marriage was actually rumoured (1426/27), Catherine was not 30 but around 25, though she was in her late 20s when Edmund Tudor was born. The idea that Beaufort fathered Edmund Tudor first appeared in the 20th century and can point to no actual evidence to support their claims. The depiction of Catherine as an older woman preying on a young Beaufort at "30 or thereabouts" is not only untrue but absurd. 30 doesn't make an a woman old and at any rate, Beaufort was only 4 years younger. Nor is it true that Catherine's life was empty or she had no role in life following the birth of Henry VI and the death of Henry V. She was still very much involved in the political landscape.

It is also striking that Richmond - despite declaring that Beaufort's "personality is irrecoverable" - credits Beaufort with the maturity and foresight to know the risk of pregnancy and the risk this pregnancy would pose to the English court, while denying Catherine the same. Catherine, who had already been pregnant and given birth, and who was older than Beaufort, more experienced politically and more central to the royal court. She was likely far more aware of the risks than Beaufort.

#catherine of valois#catherine de valois#edmund beaufort 2nd duke of somerset#rants#historian: colin richmond

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

In August 1525 the king granted him the honours, castles, rents and other hereditaments which belonged to the king's paternal grandparents, Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, and Margaret Beaufort, as well as those that had previously belonged to Margaret Beaufort's father, John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. In addition to this, the boy received a number of fine properties, including his great-grandmother's favourite residence of Collyweston.

Bessie Blount – Mistress to Henry VIII, Elizabeth Norton

#Henry FitzRoy#Margaret Beaufort#Edmund Tudor#John Beaufort 1st Duke of Somerset#Henry VIII#Bessie Blount: Mistress to Henry VIII#Elizabeth Norton#Quotes

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

how did henry VII think of edward IV? how did he refer to him during his rule?

Personally, we don’t know what Henry VII thought of Edward IV. I think it’s likely to have been more complex and/or conflicted than black-or-white, given the situation, but we naturally can’t presume to know what Henry may have felt.

Publicly, Henry gave him all the respect that was due to a former ruler. Edward's status as king by right and by law was explicit and unambiguous: he was repeatedly referred to as ‘Edward, late king of England’ (in contrast to, say, Richard III, who was derided as an undeserving usurper). In letters and other official documents, Henry would only ever refer to him as ‘our father, the most famous prince of blessed memory’. This was probably a more conventional address than not, but it certainly wasn't necessary for Henry to publicly identify with Edward in such a way - it's something he would have had to have chosen to do.

One of Edward's symbols, the white rose, became one-half of the defining symbol of Henry's regime and that of his successors. But it wasn't the only one: Yorkist emblems like the sun in splendour and the falcon and fetterlock were also used very prominently in Tudor iconography, such as the gates of Henry VII's chapel at Westminster Abbey. Henry continued other dynastic projects as well, such as the foundation of a convent for the Greyfriars.

Most strikingly, it's clear that Henry prioritized Yorkist traditions for both his heirs: his eldest son Arthur was raised at Ludlow as the March heir with Mortimer trappings, and he invested his second son Henry (the future Henry VIII) as the Duke of York, following the precedent Edward IV had begun for his second son Richard of Shrewsbury. It was only for his third unfortunately short-lived son Edmund that Henry revived the traditionally Lancastrian-associated title of Somerset. Dynastic priorities are quite clear*.

Moreover, while Henry VII repeatedly highlighted his connection to Henry VI (his uncle who was deposed and murdered on Edward's orders in 1471), taking great efforts to rehabilitate and canonize him along with the rest of the Lancastrians, Edward IV was still not officially blamed for anything. His central role in the destruction of the Lancastrians was entirely omitted from formal parliamentary records, and even the blame for Henry VI’s death was officially dumped on Richard III instead.

None of this should be especially surprising. Henry was married to Edward's daughter, and it was Edward's Yorkist supporters who "launched" Henry as an active claimant in first place after realizing that the Princes in the Tower were dead during October risings (which were originally meant to restore them to the throne) - not because they supported Henry's technical claim but because they wanted to put Edward IV's line back on the throne via Henry's marriage to Elizabeth of York. They joined him in exile and remained his councilors after he won the crown. Moreover, a great deal of Henry's reign consisted of Pretenders who sought the throne claiming that they were the sons of Edward IV - in this context, it makes sense that Henry would try to highlight his own connection to him in a similar way. (I think there's a very interesting discussion to be had about how Edward functioned as the posthumous dynastic focus for all claimants to the throne after 1483 in the lieu of Edward III for the claimants in the lead-up to the Wars in the 1450s, but that's another topic entirely).

There's also the simple fact that, despite the ample controversies of his second reign (regicide, fratricide, acceptance of bribes from France, posthumous slander by his own brother, etc), Edward IV seems to have remained very popular and well-regarded by the people of England. Even if Henry wanted to ruin his memory - and nothing suggests that he did, not least because of how it would reflect on his own queen - I think it's rather unlikely that he would have been able to do so. After all, Richard III had already tried and failed. On the contrary, the popularity and positions of Henry's own sons were bolstered by the fact that they were Edward's grandchildren and identified as such by his subjects. At the very least, Henry seems to have accepted this. However, given how closely he followed the precedents of the Princes in the Tower while raising his own sons, he was likely actively leveraging it for his own family's benefit. This is partly why I dislike the idea that Henry viewed Elizabeth of York's claim and popularity as threats to his position: we already know that this is not true, as both actually helped Henry secure his kingship and ensure the succession of his sons.

*Sean Cunningham talks about this further in the chapter "A Yorkist Legacy for the Tudor Prince of Wales on the Welsh Marches: Affinity-Building, Regional Government and National Politics, 1471-1502" in The Fifteenth Century XVIII, if you want to read up further on the topic.

#ask#henry vii#edward iv#english history#I'll edit this later#also regarding the death (murder) of Henry VI - this is probably why Ricardians are so triggered by it and are now trying to refute it#I understand their frustration to an extent as Henry VII *did* officially blame Richard rather than Edward (his father-in-law)#Richard may have been involved but either way it would've been on his brother's orders; Edward IV was the one ultimately responsible.#But what is conveniently ignored is that Tudor chronicles *did* hold Edward accountable for Henry's death - blame was officially#withheld by Henry VII but 16th century chronicles did highlight Edward as the one who was responsible as far as I know#But even if this wasn't the case that doesn't justify ricardians trying to claim that Henry VI wasn't murdered but aCTUaLLY died naturally#That's 1) utter nonsense and 2) has nothing to do with the topic at hand

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rough date timeline of Henry VI part 1 because that's how my day is going so far:

ACT 1

Scene 1: Henry V's funeral, which we know happened November 7, 1422.

Scene 2: The introduction of Joan la Pucelle, which historically happened in 1428. Six years have passed.

Scene 3: Gloster gets barred from the Tower of London, and he and Winchester are so at each other that somebody calls the cops. I can't find evidence of this being a real incident.

Scenes 4-6: Seige of Orleans, 1428-29. The French artillery's aim is getting better and Salisbury is killed. The English find out about Joan la Pucelle, who is on her way to lift the seige. Talbot is said to have been recently exchanged for a French prisoner, but this does not make sense.

ACT 2

Scenes 1-3: The English attack Orleans again to avenge Salisbury. Talbot meets/is taken prisoner by the Countess of Aubergne. (He was a French prisoner from 1429-33, but this isn't how he was taken.) Presumably this is why the French are able to break the seige.

Scene 4: Rose-picking in the garden scene. Did not happen, but I would put it in the summer of 1429, making Richard Duke of York not quite 18.

Scene 5: Edmund Mortimer shows up, explains some family history, and then dies. This didn't happen but that is a separate post entirely.

ACT 3

Scene 1: Fighting breaks out in Parliament courtesy of Gloster and Winchester. Henry VI has speaking lines for the first time, implying that it is at least November 1429, and he is about 8. Gloster suggests that Henry VI be crowned in France.

Scene 2: Bedford dies of illness while the French unsuccessfully attack Rouen. This would make it 1435, except Henry VI has recently arrived in France to be crowned, so it is probably 1430.

Scene 3: The French plot revenge for Rouen and Burgundy switches sides. It is now simultaneously 1435.

Scene 4: The English are in Paris, Talbot is made Earl of Shrewsbury (1442).

ACT 4

Scene 1: Henry VI is crowned in Paris (1431). He tries to "both sides" Somerset and York while putting on a red rose badge, but he's only 10 so let's give him some slack.

Scenes 2-4: Talbot and his son are killed fighting near Bordeaux while Somerset and York argue about whether or not to send reinforcements from elsewhere in Gascony. This historically happened in 1453, when Somerset and York were back in England.

ACT 5

Scene 1: Henry VI and Gloster discuss marriage to a daughter of the earl of Armagnac, so it's about 1442. Henry thinks he's too young (21?), but sends a gift to anyway.

Scenes 2-3: York captures Joan la Pucelle. Suffolk becomes soggily besotted with Margaret d'Anjou and negotiates her marriage to Henry VI. None of this happened, but Margaret's marriage negotiations began around 1444.

Scene 4: Speedrun of Joan la Pucelle's trial, 1431. Charles agrees to be Henry's subject if the English leave, which did not happen.

Scene 5: Suffolk and Winchester successfully argue for Margaret d'Anjou as Henry VI's bride, ending the play in 1444.

#shakespeare#wars of the roses#henry vi#richard duke of york#garen what are you doing#henry vi part 1#shakespearean timelines#edmund mortimer#Margaret d'Anjou was a toddler when Joan of Arc was executed#why are they in the same scene as teenagers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELIZABETH OF YORK (1466 - 1503)

She was the daughter of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville.

She was the Queen of England from 1486 through her marriage to King Henry VII until her death in 1503.

The marriage to Henry VII marked the end of the civil war known as the War of the Roses.

She was renowned as a great beauty for her time, tall in stature (168cm) and had a fair complexion.

She died due to a postpartum infection during her last pregnancy.

She was only 37 years old.

She had seven children with her husband;

Arthur - Prince of Wales (1486 - 1502)

Margaret - Queen of Scotland (1489 - 1541)

Henry VII - King of England (1491 - 1547)

Elizabeth (1492 - 1495)

Mary - Queen of France (1496 - 1533)

Edmund - Duke of Somerset (1499 - 1500)

Katherine (1503 - 1503)

Credit: Recreation of Elizabeth of York done by me, through Photoshop.

Reference: British School, 16th Century - Elizabeth of York (1466-1503) - RCIN 403447 Royal Collection

#elizabeth of york#house of york#house of tudor#house of plantagenet#queen consort of england#english royalty#english consorts#15th century nobility#english princesses

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

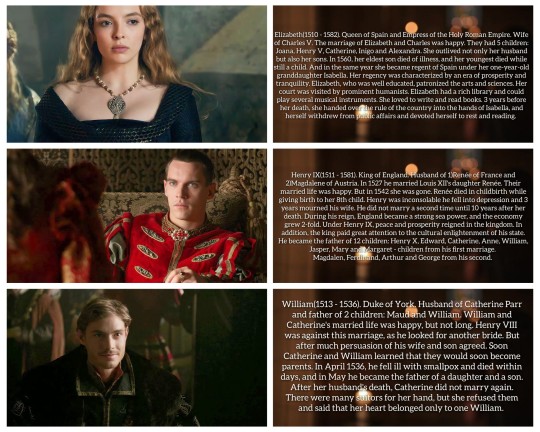

AU House of Tudors: Children Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

Catherine of Aragon(1485 - 1543).In 1501 Catherine of Aragon became the wife of Prince Arthur, but he died half a year later. In 1509 she married Henry VIII. Their married life was happy despite the fact that Catherine was 6 years older than Henry. She also often took an active part in the affairs of state. The marriage produced 6 children. The death of Prince William undermined Catherine's health and because of this she began to have frequent heart aches. She died in 1543 of heart disease.

Elizabeth(1510 - 1582). Queen of Spain and Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. Wife of Charles V. The marriage of Elizabeth and Charles was happy. They had 5 children: Joana, Henry V, Catherine, Inigo and Alexandra. She outlived not only her husband but also her sons. In 1560, her eldest son died of illness, and her youngest died while still a child. And in the same year she became regent of Spain under her one-year-old granddaughter Isabella. Her regency was characterized by an era of prosperity and tranquility. Elizabeth, who was well educated, patronized the arts and sciences. Her court was visited by prominent humanists. Elizabeth had a rich library and could play several musical instruments. She loved to write and read books. 3 years before her death, she handed over the rule of the country into the hands of Isabella, and herself withdrew from public affairs and devoted herself to rest and reading.

Henry IX(1511 - 1581). King of England. Husband of 1)Renée of France and 2)Magdalene of Austria. In 1527 he married Louis XII's daughter Renée. Their married life was happy. But in 1542 she was gone. Renée died in childbirth while giving birth to her 8th child. Henry was inconsolable he fell into depression and 3 years mourned his wife. He did not marry a second time until 10 years after her death. During his reign, England became a strong sea power, and the economy grew 2-fold. Under Henry IX, peace and prosperity reigned in the kingdom. In addition, the king paid great attention to the cultural enlightenment of his state.

He became the father of 12 children: Henry X, Edward, Catherine, Anne, William, Jasper, Mary and Margaret - children from his first marriage.

Magdalen, Ferdinand, Arthur and George from his second.

William(1513 - 1536). Duke of York. Husband of Catherine Parr and father of 2 children: Maud and William. William and Catherine's married life was happy, but not long. Henry VIII was against this marriage, as he looked for another bride. But after much persuasion of his wife and son agreed. Soon Catherine and William learned that they would soon become parents. In April 1536, he fell ill with smallpox and died within days, and in May he became the father of a daughter and a son. After her husband's death, Catherine did not marry again. There were many suitors for her hand, but she refused them and said that her heart belonged only to one William.

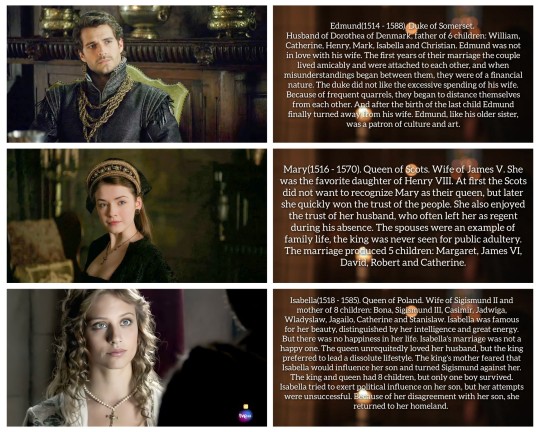

Edmund(1514 - 1588). Duke of Somerset. Husband of Dorothea of Denmark, father of 6 children: William, Catherine, Henry, Mark, Isabella and Christian. Edmund was not in love with his wife. The first years of their marriage the couple lived amicably and were attached to each other, and when misunderstandings began between them, they were of a financial nature. The duke did not like the excessive spending of his wife. Because of frequent quarrels, they began to distance themselves from each other. And after the birth of the last child Edmund finally turned away from his wife. Edmund, like his older sister, was a patron of culture and art.

Mary(1516 - 1570). Queen of Scots. Wife of James V. She was the favorite daughter of Henry VIII. At first the Scots did not want to recognize Mary as their queen, but later she quickly won the trust of the people. She also enjoyed the trust of her husband, who often left her as regent during his absence. The spouses were an example of family life, the king was never seen for public adultery. The marriage produced 5 children: Margaret, James VI, David, Robert and Catherine.

Isabella(1518 - 1585). Queen of Poland. Wife of Sigismund II and mother of 8 children: Bona, Sigismund III, Casimir, Jadwiga, Wladyslaw, Jagailo, Catherine and Stanislaw. Isabella was famous for her beauty, distinguished by her intelligence and great energy. But there was no happiness in her life. Isabella's marriage was not a happy one. The queen unrequitedly loved her husband, but the king preferred to lead a dissolute lifestyle. The king's mother feared that Isabella would influence her son and turned Sigismund against her. The king and queen had 8 children, but only one boy survived. Isabella tried to exert political influence on her son, but her attempts were unsuccessful. Because of her disagreement with her son, she returned to her homeland.

AU Дом Тюдоров:Дети Генриха VIII и Екатерины Арагонской.

Екатерина Арагонская(1485 - 1543). В 1501 году Екатерина Арагонская стала женой принца Артура, но через пол года он умер. В 1509 она вышла замуж за Генриха VIII. Их супружеская жизнь была счастливой несмотря на то, что Екатерина была старше Генриха на 6 лет. Также она часто принимала активное участие в делах государства. В браке родилось 6 детей. Смерть принца Уильяма подкосило здоровье Екатерины и из-за этого у неё стало часто болеть сердце. Умерла в 1543 году от сердечной болезни.

Елизавета(1510 - 1582). Королева Испании и императрица Священной Римской империи. Жена Карла V. Брак Елизаветы и Карла был счастливым. У них родилось 5 детей: Хуана, Энрике V, Екатерина, Иниго и Алехандра. Пережила не только мужа, но и своих сыновей. В 1560 году от болезни умер ее старший сын, а младший умер ещё в детстве. И в этом же году она стала регентом Испании при своей годовалой внучке Изабелле. Её регенство характерезуится эпохой процветания и спокойствия. Елизавета, получившая хорошее ��бразование покровительствовала искусствам и наукам. Её двор посещали выдающиеся гуманисты. У Елизаветы была богатая библиотека, а также она умела играть на нескольких музыкальных инструментах. Любила писать и читать книги. За 3 года до своей смерти вручила правление страной в руки Изабелле, а сама отошла от государственных дел и посвятила себя отдыху и чтению.

Генрих IX(1511 - 1578). Король Англии. Муж 1)Рене Французской и 2)Магдалины Австрийской. В 1527 году женился на дочери Людовика XII Рене. Их супружеская жизнь была счастливой. Но 1542 году её не стало. Рене умерла при родах, рожая 8 ребёнка. Генрих был безутешен он впал в депрессию и 3 года оплакивал жену. Женился во второй раз только через 10 лет после её смерти. В период его правления Англия стала сильной морской державой, а также в 2 раза увеличился рост экономики. При Генрихе IX в королевстве царил мир и процветание. Кроме этого, король уделял большое внимание культурному просвещению своего государства.

Стал отцом 12 детей: Генрих X, Эдуард, Екатерина, Анна, Уильям, Джаспер, Мария и Маргарита - дети от первого брака.

Магдалена, Фердинанд, Артур и Джордж - от второго.

Уильям(1513 - 1536). Герцог Йоркский. Муж Екатерины Парр и отец 2 детей: Мод и Уильям. Супружеская жизнь Уильяма и Екатерины был счастливой, но не долгой. Генрих VIII был против этого брака, так как подыскал ему другую невесту. Но после долгих уговоров жены и сына согласился. Вскоре Екатерина и Уильям узнали, что скоро станут родителями. В апреле 1536 года он заболел оспой и умер в течение нескольких дней, а в мае стал отцом дочери и сына. После смерти мужа Екатерина больше замуж не вышла. Было много претендентов на её руку, но она им отказывала и говорила, что её сердце принадлежит лишь одному Уияльму.

Эдмунд(1514 - 1588). Герцог Сомерсет. Муж Доротеи Датской, отец 6 детей: Уильям, Екатерина, Генрих, Марк, Изабелла и Кристиан. Эдмунд не был влюблен в свою жену. Первые годы брака супруги жили дружно и были привязаны друг к другу, а когда между ними начались недоразумения, то они носили финансовый характер. Герцогу не нравились чрезмерные расходы жены. Из-за ��астых ссор они стали отдаляться друг от друга. А после рождения последнего ребёнка Эдмунд окончательно отвернулся от жены. Эдмунд, как и его старшая сестра был покровителем культуры и искусства.

Мария(1516 - 1570). Королева Шотландии. Жена Якова V. Была любимой дочерью Генриха VIII. Поначалу шотландцы не хотели признавать Марию своей королевой, но позже она быстро завоевала доверие народа. Также она пользовалась доверием своего мужа, который часто оставлял её регентом на время своего отсутствия. Супруги были примером семейной жизни, король ни разу не был замечен за публичным изменами. В браке родилось 5 детей: Маргарита, Яков VI, Давид, Роберт и Екатерина.

Изабелла(1518 - 1585). Королева Польши. Жена Сигизмунда II и мать 8 детей: Бона, Сигизмунд III, Казимир, Ядвига, Владислав, Ягайло, Екатерина и Станислав. Изабелла славилась своей красотой, отличалась умом и большой энергией. Но счастья в её жизни не было. Брак Изабеллы был не счастливым. Королева безответно любила своего мужа, но король предпочитал вести разгульный образ жизни. Мать короля опасалась того, что Изабелла будет оказывать влияние на сына и настраивала Сигизмунда против неё. У короля и королевы было 8 детей, но выжил лишь один мальчик. Изабелла пыталась оказывать политическое влияние на своего сына, но её попытки остались без успешны. Из за разногласий с сыном она вернулась на Родину.

#history#history au#royal family#royalty#au#henryviii#mary tudor#british royal family#british royalty#British king#British queen#history of england#british history#english#english history#england#elizabeth of york#henry viii#Marytudor#marytudor#english royalty#royals#royal#16th century#britishroylsfamily#britishroyal#charles brandon#henry cavill#isabellaofcastile#jonathan rhys meyers

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wasn't there also a bit of a culling by the House of York of other Lancastrian claimants such as the Marquess of Dorset and the Duke of Somerset's beheadings in 1471 or the Duke of Exeter's drowning in the English Channel in 1475 and the Duke of Buckingham's beheading in 1483? Maybe some others? Those deaths were another boosting up for Henry VIII pre-Bosworth Field?

The deaths of John and Edmund Beaufort don't fit: John was killed during the fighting at Tewksbury and Edmund two days later because they had fought for Henry VI as the Lancastrian King of England and while they were both of the House of Lancaster, they were certainly behind Henry and his son Edward of Westminster in the line of succession and were not claimants to the throne at the time of their death.

Whether Exeter was actually assassinated or just fell overboard is a matter of rumor, but again he wasn't a claimant and if he was killed it was probably because he had fought for Lancaster even after marrying Anne of York, which Edward would porbably have considered a betrayal. Buckingham wasn't a claimant either; his rebellion was on behalf of Henry Tudor.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Can’t stop thinking about another thing that fucked up Miraculous was introducing real historical figures.

Yes they say kwamii were responsible for real events: like Plagg killing the Dinosaurs, Plagg causing the Leaning Tower of Piza (just Plagg doing a lot of things) and it’s cool idea to think about. But it fucks up so much. They introduced Darkblade, which is a really cool idea; what if someone in the cast had a tyrant monarch ancestor. To which they never do anything with. Then you learn that Darkblade is based off a historical figure. @lordmartiya’s post explains it well. Which is okay, yeah you can believe it characters are based off of historical figures often. Sure….

Then miraculous goes and adds Jeanne d’Arc into the show!

This opens the floodgates, giving you more questions than answers. Because if they could add Jeanne, why couldn’t they then add the figure Darkblade was based off. And you might say “Blueberry, Jeanne d’Arc is more well known, people can at least recognise her name.” That’s fair but why include an historical figure to start with because it makes little sense for many reasons. Again with Jeanne, adult miraculous holders don’t have restrictions compared to the children. Jeanne had the ladybug miraculous that wasn’t broken. So why couldn’t she just create a bunch of stuff and then win! Because having the Ladybug miraculous makes you overpowered. Going back to Plagg, it messes up historical events and possibly the entire timeline of history.

This leads to my main point: other historical figures having miraculous. I’ll stick to medieval England and France because it’s what I know best. Like Henry VIII?! Can you imagine him running around with a miraculous! In fact let’s take a look at a set of historical events. With my favourite….

THE WAR OF THE ROSES!!!

Yes I will talk about this event and everyone involved at every possible opportunity. if even one of these nobles had a miraculous (regardless of which one) the fight either would have been drawn out for maybe another ten years. Or we wouldn’t even make it to the first Battle of St Albans! Richard Plantagenet would‘ve had Edmund Beaufort done away with as soon as he got one. imagine both of them with a miraculous! They’d be murdering each other every other day.

What the hell am I supposed to do with any of this information or any of the implications/interpretations you can take from this?! You could say that hypothetically Richard III got ahold of the rabbit miraculous and just sent the Princes in the Tower to an alternate timeline in miraculous. I’m not going to start with the time travel.

Then again, I could make some horror/crack au’s of historical figures with miraculous. Either a historical figure actively with a miraculous. Or the whole being able to contact past user’s memories thing. (Though I’ll change it to literal ghosts) like can you imagine Chloe running around with the bee miraculous with the ghost of medieval noble!

#miraculous ladybug#miraculous#history#english history#medieval england#ml Darkblade#medieval france#jeanne d'arc#william the conqueror#henry viii#richard iii#war of the roses#wars of the Roses#the wars of the roses#richard plantagenet#richard duke of york#Edmund Beaufort#Edmund Duke of Somerset#blueberry rambles#blueberry’s miraculous rambles

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who are the people attending Elizabeth Woodville's funeral?Are they all her relatives?

Hi! Yes, her three daughters - Anne, Katherine and Bridget as well as her only son Thomas Grey with his wife and their daughter (Elizabeth’s granddaughter), her nieces and nephews, Cecily’s husband - Elizabeth’s son-in-law, Edward IV’s closest male relative Edmund de la Pole.

Mourners were soon arriving, however, three of her unmarried daughters arrived on Tuesday 12 June, Princesses Anne (born 1475), Katherine (born 1479), and Bridget (born 1480) and her daughter-in—law, Cecily Bonville, the wife of her eldest son and marchioness of Dorset. With them was an unmarried niece, Elizabeth, the daughter of Katherine Woodville, sister to the dead queen and dowager duchess of Buckingham, a grand-daughter, one of the daughters of her son the marquess of Dorset and yet another niece, Elizabeth, Lady Herbert in her own right as the only child of William Herbert, Lord Herbert and Earl of Huntingdon and Pembroke; and his first wife, Mary, another sister of the dead queen — the herald-narrator is apparently not aware that the sixteen year-old heiress had just been married in the king's presence on 2 June to his favourite, Sir Charles Somerset. There also arrived Lady Egremont, Dame Katherine Grey, and Dame Guildford, either the wife of Sir John Guildford or his son, Sir Richard, a family closely linked to the Woodvilles and Hautes. Part of the narrative seems to be missing at this point; it probably reported that these ladies knelt around the hearse according to their rank, while Dirige was sung. On Wednesday 13 June a mass of requiem was held while the three daughters knelt at ‘the hed’, their gentlewomen behind them. That same morning arrived Thomas, Marquess Dorset, the queen’s son, and Edmund de La Pole, son of the duke of Suffolk, the closest living male relative of Edward IV, Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex, a nephew of the dead queen by her sister, Anne, John, Viscount Welles, who had married Cecily, the second surviving daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Sir Charles Somerset; the brand-new husband of Elizabeth, Lady Herbert and, last of the seculars, Sir Roger Cotton, Edward Haute, her second cousin through their common grandfather, Richard Woodville, Master Edmund Chaderton also came, once treasurer of Richard III and now chancellor to Queen Elizabeth of York.

from “The Royal Burials of the House of York at Windsor: II. Princess Mary, May 1482, and QueenElizabeth Woodville, June 1492.” by Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What if Elizabeth of henry vii and York don't have a son back? Furthermore, what if they don't have children? (Maybe Henry would like the legitimate illegitimate son of the third Duke of Somerset to marry Cecily of York and make him the heir ...)

If he doesn't have kids then it's a disaster to the extent that Henry VII might not survive his reign or might attempt a divorce with Elizabeth of York (or maybe even the reverse). Richard III could have survived Bosworth is his son was alive.

I really don't think he would have promoted Somerset because a bastard of a bastard line don't stand much chance. I think that plan B was shown quite early by Henry VII: he married his uncle to Cecily of York, so I think he would have pushed them or their descent to the throne. The problem is they had none. So after that, speculating that Henry VII is still alive, I think he would have two main choices which are:

Edward Stafford, duke of Buckingham. Pros: rich and a HUGE landowner; prestigious from an ancient line who descent from Edward III through two lines; very connected in the peerage (Percies, Woodvilles, etc...).

The Courtenays because the Earl's son is the only other one who had children with a daughter of Edward IV. Less powerful, less connected but they are still important and they have the Yorkist connection that Edward Stafford lack.

What would Henry VII do? I do not know. It's quite possible he would act like his grandaughter Elizabeth: not chose, and play each faction against the other. So his choice of successor would depend on events. What does Stafford and Courtenay do? On our history, the Courtenays did plot against Henry VII with Edmund de la Pole. Maybe they would openly rebel or, on the contrary, be very loyal to hope Henry VII would name them. The same goes for the de la Poles.

So, we have no idea. Also, what Henry VII decided didn't matter that much after he die. His predecessor and successor made successoral arrangement that weren't respected by political actors.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those who formulated the statute relating to the marriage of dowager-queens were clear about the problems such marriages posed. These included the implications that might flow from a new husband whose social status was inferior to that of his wife. Its terms, therefore, expressed fears for the disparagement of the Queen, whose honour (as well as that of the Crown itself) needed to be safeguarded. Secondly, although it was provided that he who married a dowager queen without the King's permission should suffer forfeiture of his lands and other possessions during his lifetime, this relatively mild punishment reflected an awareness that there might be children of an illicit marriage who would in some sense be members of the royal family and merit treatment as such—as, indeed, Jasper and Edmund Tudor, the sons of Katherine and Owen, were accorded by Henry VI later on. Certainly, there was no question of regarding such a union as treasonable or rendering it null and void. Behind the statute's provisions lay a further apprehension that a new husband might endeavour to play a part in English politics. Consequently, it was declared that permission to marry should be given by the King only when he had reached years of discretion (esteantz dez anz de discretion). If duly observed, this clause would effectively delay Queen Katherine's remarriage for some years yet, for in 1427 Henry VI was barely six years old; and for the time being, there would be no step-father available to influence the impressionable boy-king. This provision was presumably the principal reason for Katherine's marrying Owen in secrecy and the justification for the Welshman's arrest after the Queen's demise in 1437.

Ralph A. Griffiths, “Queen Katherine of Valois and a Missing Statue of the Realm”, King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century (The Hambleton Press 1991)

#couple of things.#imho this discussion of the marriage makes it clear that the statue relating to catherine's remarriage came about as the result#of fears of catherine's potential remarriage to edmund beaufort rather than owen tudor#yes - tudor could be said to hold the same threat as beaufort to catherine's honour and to the influence on the king#however - i think beaufort was a lot more potent a threat in that regard due to his aristocratic status and because of his ambitious family#secondly i think it makes it plain what the fears of the council was re: catherine's remarriage and that they were somewhat justified.#it was not really about catherine herself but about the threat her new husband would pose to the court that was already in conflict#- most notably the conflict between humphrey duke of gloucester and henry beaufort - edmund beaufort's uncle to whom he owed much.#in this regard i think j. allan mitchell's idea that lydgate promoted owen tudor being the perfect match for catherine makes a lot of sense#catherine of valois#catherine de valois#owen tudor#edmund beaufort 2nd duke of somerset#historian: ralph a. griffiths

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding Bridget of York: if her career as a nun was planned from the beginning, wouldn't the decision lie with Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV as her parents and as the king and queen? I'm not saying it's impossible for Cecily to have suggested it, it's conceivable, but wouldn't the more likely and more default option be her parents? Especially since both of them were also devoted to St. Bridget and Elizabeth Woodville was also very pious. And, like you said, Bridget was the fifth surviving daughter, I think there were practical reasons for them to not use her for a marriage alliance. I think it's just a bit of a stretch to assume that Bridget's potential church career was Cecily's plan, I don't think Cecily probably naming her due to her piety should be taken to mean that she was the one who was planning her life path? Imo, that's a bit of a leap. Unless there's evidence for the contrary, I think the standard expectation should be that, if there was a church career in mind, it was planned ny Bridget's parents. Especially since Cecily doesn't seem to have really been involved in the lives and upbringing of any of her grandchildren by Edward, from what I can tell.

Hi! Referring to this post. I think I did not make myself clear: I used Cecily Neville's connections to St Bridget and her special relationship with her granddaughters who took the veil to make a point about the importance of St Bridget in the Yorkist family as a whole. Clearly, Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville would have had their input on Bridget's future, as I mentioned Elizabeth Woodville's devotion to St Bridget and Edward IV's use of one of her prophecies. When I highlighted Cecily's position, I meant it more like the time Margaret Beaufort stood as godmother to her grandson Prince Edmund, the once future Duke of Somerset (a title Margaret's father held); compared to the other Tudor children, she seems to have been particularly involved in his birth and it's not inconceivable she was the one who suggested his name. Still, of course Henry VII and Elizabeth of York would have had a say in his name and future too. Families were much less nuclear/centred solely on the parents in the middle ages. What I was trying to highlight was a shared thinking that probably influenced Bridget's position in life.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward IV's First Parliament Attainder

Henry duke of Exeter

Henry duke of somerset

Thomas Courteney, Earl of Devonshire, k.

Henry Percy, Earl of northumberland, k.

William Beaumont

John, lord Clifford, k.

Leo, lord Welles, k.

Thomas, lord Roos

John, lord Neville k.

Thomas Grey, knight

Lord Rugemond Grey

Randolf, lord Dacre, k.

Humphrey Dacre, knight

John Morton of Blokesworth, Dorset, Clerk k.

Ralph Makerwell of Rysebey, Suffolk, Clerk k.

Thomas Manning of Lichfield, Stafford, Clerk k.

John Naylor of London, Clerk, k.

John Preston of Wakefield, Yorks, Squire, k.

Philip Wentworth, Knight

John Fortescue, Knight

William Tailboys, Knight

edmund Moundford, Knight

Thomas Tresham, Knight

Thomas Findern, Knight

John Courtney, Knight

Henry Lewes, Knight

Nicholas Latimer, Knight

Walter Nuthill, of Rylston, Yorks, Knight k.

John Heron, Squire

Richard Tunstall, Knight

Henry Bellingham, Knight

Robert Wittingham, Knight

John Ormond aka Butler, Knight

William Mille, Knight

Simon Hammes, Knight

William Holand, Knight, (The bastard of Exeter)

William Joseph, Squire, k.

Everard Digby, Squire, Rutland

John Mirfin, Squire, southwark, Surrey

Thomas Philip, Squire, Dertington Devon

Giles Saintlove, Squire, London

Thomas Claymond, aka Tunstall, Squire

Thomas Cranford, Squire, Calaise k.

John Audley, Squire, Guines

John Lenche of Wiche, Squire, Worcestershire

Thomas Ormond, aka Butler, Knight

Robert Bellingham, Squire, Burnalshede, Westmoreland k.

Thomas Everingham, Squire, Newhall, Leicestershire k.

John Penycock, Squire, Weybridge, Surrey k.

William Grimsby, Squire, Grimsby, Lincolnshire k.

Henry Ross, Knight, Rockingham, Northhampton k.

Thomas Daniel, Squire, Rising, Norfolk k.

John Doubigging, Gentleman, Kirkby Ireleth, Lancashire k.

William Ackworth, Squire, Luton, Bedfordshire k.

William Weynesford, Squire, London k.

Richard Stuckley, Squire, Lambeth, Surrey k.

Thomas Stanley, Gentleman, Carlisle k.

Thomas Liteley, Grocer, London k.

John Maidenwell, Gentleman, Kirtin, Lincoln k.

Edward Ellesmere, Squire, London k.

Henry Spencer, Yeoman, Westminster k.

John Smothing, Yeoman, York k.

John Beaumont, Gentleman, Goodby, Leicestershire k.

Henry Beaumont, Gentleman, Goodby, Leicestershire k.

Roger Wharton, aka Roger of the Halle, Groom, Burgh, Westmoreland k.

John Joskin, Squire, Branging, Hertfordshire k.

Richard Lister the younger, Yeoman, York k.

Robert Bolling, Gentleman, Bolling Hall, York k.

Robert Hatecale, Yeoman, Barleburgh k.

Richard Everingham, Squire, Pontefract k.

Richard Fulnaby, Gentleman, Fulnaby, Lincoln k.

Luarence Hill, Yeoman, Much Wycombe, Bucks k.

Rauff Chernock, Gentleman, Estretford in Cley, Notts k.

Richard Gaitford, gentleman k

John Chapman, Yeoman, Wimbourne Minster, Dorset k.

Richard Cokerall, Merchant, York k.

0 notes