#each of those organisms could be hosted by an individual mime

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

wondering for oc reasons - if two (or more) mimes were closely bonded (similar to how n&o are a package deal, in a sense) would they be able to host in the same body? if not, is it ever possible for that to happen?

No, even N & O cannot host the same thing at the same time. One host can only hold the system of one mime, and especially in biological hosts, the conflict of hemolymph would not allow both to exist in the same body.

A mime invades the host's system with their own, stemming out themselves to conform to the innards of the body, and that doesn't leave much room or functionality for a second controller.

That being said, in very special circumstances like in Atromea's case, it is still theoretically possible. Atromea, while mentally two seperated mimes, is fused into one functional being. They have their own unique color of hemolymph and there is no issue of two different colors mixing. Together they could host one body, though it'd probably be a mental mess. As soon as they split up though, they are two seperated bodies and can no longer host in one single individual.

Mimes bound together such as Atromea are a rare case, but obviously not impossible to achieve-- and that would be the only way two mimes could host together.

#it's a little more complex when it comes to electronic hosts#because their hemolymph is converted to electricity instead#if there are two bound sources of electricity in one electronic device#two mimes could host one device#but what functions either mime can control is directly derivative of their hosted side of the power#if that makes any sense#you could also get into sea life where there are organisms that are technically colonies of several organisms working in tandem#each of those organisms could be hosted by an individual mime#why the hell there would be millions of mimes dedicated to controlling like. one colony of coral or something...#that's beyond me.#but never the less it's possible#brambleramble

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

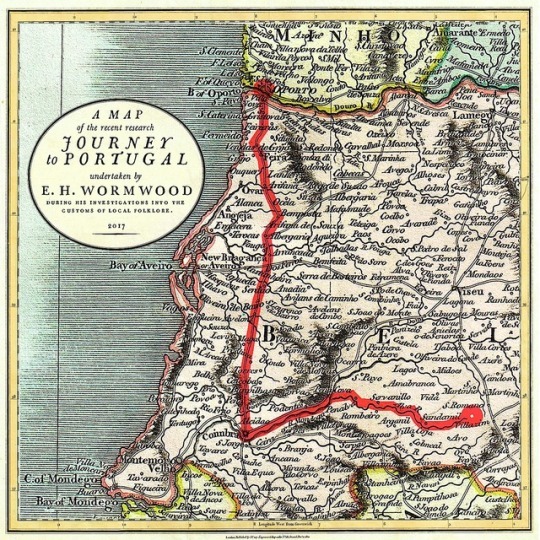

A Perfect Place to Start a Cult

My journey to Portugal was a success overall, gathering further documentation of apotropaic symbols and sigils found on various agricultural buildings and interviewing several locals, even witnessing a bit of practice in a rather grisly ritual involving the death of a small lizard. But on my way a strange set of circumstances occurred that I thought would be relevant to readers.

After landing in Porto I took a train to the university city Coimbra, and from there travelled by coach into the mountains eastward along the river Alba. My previous local contact was away on holiday but had offered to put me in touch with a couple who knew the local area I am exploring and speak fluent Portuguese (they are Dutch) and English. It was with this couple I was to stay, travel, and utilize as translators in my research for my two week visit.

The first few days of my exploration were simple enough, reconnecting with a few locals I had met previously and getting acquainted with my hosts. But after several days, when the introductions had been made and the meat of the work was to begin, the tone of my hosts started to change.

My work, as it is explained to those hosting and working with me, is that of folklore based research. My personal practice, occultist background, and this blog remain absolutely outside of discussion, not something that is meant to be known in the context of my research on the ground.

It was on the fourth day of my visit that my hosts began to discuss their involvement with what they described in English as the "Men's and Women's Group." A "spiritual collective" founded by an unnamed British "Spiritual Leader" and his wife on a piece of property in the mountains not far from where their home, my temporary residence, was located.

The first discussions of this group were made in the context of an invitation to join the couple for afternoon meditation. I politely declined as I had a stack of handwritten notes I wanted to transcribe and took my coffee to their renovated schist "volunteer kitchen" to work. After they had meditated the male came to chat and express mild disappointment with my reluctance to join in the meditation.

Over dinner that evening the "Men's and Women's Group" was brought up, with both partners enthusiastically telling me of the great things that their ostensible guru was teaching them. About how a combination of "hard work and meditation" would lead them on a deeper spiritual path that would "bring them closer to nature." They emphasized that I myself would benefit from the group's teachings and that I could join them if I was interested.

I managed to change the conversation to the next day's travel and my interviewing of a local Portuguese healer and tarot reader of Roma (gypsy) origin. They knew the fellow in passing and expressed a dislike for him, though I sensed it was my male host who disliked him more so than the female.

After the next day's interview and a bit of hiking through thick bramble to an abandoned site with several ruined stone agricultural buildings we returned for a late dinner to the property. The afternoon had gone well and the vibe was relaxed, but on returning I sensed an underlying stress between my hosts, clearly directed at myself.

Over the next week a pattern would emerge, where they attempted to coerce me into joining them in their meditative practice, expounding the need to "reaffirm our connection to nature and silence." At one point the male and I were discussing their having moved to this remote mountain village several years before from the Netherlands to live off-grid as sustenance farmers. He made the comment that they had left behind jobs and city living in order to live a "simple life", to which I replied that in fact the life of a farmer is no more simple than that of an urban dweller.

He insisted that this life of hard labour and toil (they rise at 6:30am everyday, work their plot of land, prepare the various harvests, and build further outbuildings, etc seven days a week) was "simple". I replied that if they were to ask the Portuguese farmer who works the land over the hill and whose family has done so for countless generations if their life was "simple" I doubt the locals would agree.

In hindsight the couple were very similar, in a secular way, to the family in the recent film the VVitch. Hard toil and meditation (instead of prayer) as a salvation for some unknown sin of modern living. They spoke in phrases that are all too familiar to those who have had dealings with the various cults and gurus in the new age world. Repeating lines about "being" and "healing", miming the platitudes of their spiritual leader, who has obviously learned from a long trodden playbook of using hard labour as a means to break down his followers, making them obedient to his and his spouse's demands.

The couple actually pay this "Men's and Women's Group" to go and work the spiritual teacher's land on several days a week. I was invited to join them on their days at the group's compound but declined. I suspected that the group, which comprises some 50 individuals by the couple's account, was not a place I would find comfortable.

The gist of the trip began to cumulate in several exchanges where my male host would confront me in a rather tacky and uncivil manner (they called it "speaking directly") and state that it was clear that I was "attention seeking" and that I would never be "fulfilled" in my life until I was able to "heal myself" through the techniques they espoused via their spiritual teacher. They both accused me of being "unbalanced" and stated that I needed to find my "spiritual path" in order to heal what was "broken" in myself. These terms, straight-up cult nonsense, and the reality of my own decades long practice made me near to bursting out in laughter on several occasions.

It was all I could do, in a conversation where I was pointing out to them that they seem to confuse the term "spirituality" with the concept of "mindfulness", not to laugh when the male said with absolute conviction that he had been studying for "three years with his spiritual teacher", dismissing my decades of folklore research and master's degree in Anthropology, not to mention my unknown to them life of occult practice.

They were, despite these awkward exchanges and cultist behavior, often pleasant company. But I got the feeling that their niceness, so to speak, was a mask in order to present me with a compelling reason to join in with their group.

That a veritable cult exists in this region of Portugal is something that needs to be made aware to those who may have exchanges with them. The cult seems to prey on those who seek an off-grid/permaculture/rewilding lifestyle. From conversations the members are both expats from the UK/Netherlands/Germany and urban Portuguese who have come out to the mountains to escape city living. They divide the genders into binary groups and use concepts like "spiritual evolution" to sucker naive fools into paying for the privlege of eating this garbage as some path to enlightenment.

My regular contact, who is a Portuguese native, seemed to have no idea about the nature of my temporary hosts "spiritual" beliefs when I inquired. It seems these northern Europeans see Portugal as a convenient locale in which to grow alternative communities, or more accurately colonies, in the quiet hills. Much like Oregon in the US was in the 80s and 90s.

The trip was successful despite the background nonsense and my gathering of information and notes toward an understanding of contemporary Portuguese folk practices related to healing, the craft practice, and the historic use of apotropaic symbols in marking agricultural buildings continues. In the future I will avoid those of non local origin as my contacts and hopefully my original, if imperfect, contact in the area will be available on my next trip.

As a practitioner one will run into these forms of organized tomfoolery the world over in our quest to understand. Beware of them and any organization that seeks guidance from a self described spiritual leader. Many times one hears the adage from former members that the "tools" or "message" used in the group are valid despite the leader or teacher being broken. But to those of the Craft the knowledge that a broken maker makes a broken tool is evident.

The edges of the world of "cults" and the "occult" rub against each other constantly. A coven can become a cult as much as a brotherhood or a circle. The true teachers of the world rarely seek the role of leader, and never ask for a thing from those whom learn in their stead. Nor do they ever, ever, ever charge a fee.

The big difference between a cult and the occult is that an occultist can keep a secret. Beware of those who would seek to give specific definition to concepts like spirituality, being, or knowledge. Always remember, there is no truth.

#skeptical occultist#occult books#rare books#folklore#folkresearch#witch#witchcraft#apoptropaic#portugal#bruja#bruxa#folkwitch#cult#cults#spiritual#coven#brotherhood#hexen#hex#curse#alchemy#necromancy#sacrifice#spellwork#witchy

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature is a collaborative act.

If humans are the most evolved species, it is only because we have developed the most advanced ways of working and playing together.

We’ve been conditioned to believe in the myth that evolution is about competition: the survival of the fittest (Bullshit) In this view, each creature struggles against all the others for scarce resources. Only the strongest ones survive to pass on their superior genes, while the weak deserve to lose and die out (More Bullshit)

But evolution is every bit as much about cooperation as competition. Our very cells are the result of an alliance billions of years ago between mitochondria and their hosts. Individuals and species flourish by evolving ways of supporting mutual survival. A bird develops a beak which lets it feed on some part of a plant that other birds can’t reach. This introduces diversity into the population’s diet, reducing the strain on a particular food supply, and leading to more for all. What of the poor plant, you ask? The birds, much like bees, are helping the plant by spreading its seeds after eating its fruit.

Survival of the fittest is a convenient way to justify the cut-throat ethos of a competitive marketplace, political landscape, and culture. But this perspective misconstrues the theories of Darwin as well as his successors. By viewing evolution through a strictly competitive lens, we miss the bigger story of our own social development and have trouble understanding humanity as one big, interconnected team.

The most direct benefit of more neurons and connections in our brains is an increase in the size of the social networks we can form.

The most successful of biology’s creatures coexist in mutually beneficial ecosystems. It’s hard for us to recognize such widespread cooperation. We tend to look at life forms as isolated from one another: a tree is a tree and a cow is a cow. But a tree is not a singular tree at all; it is the tip of a forest. Pull back far enough to see the whole, and one tree’s struggle for survival merges with the more relevant story of its role in sustaining the larger system.

We also tend to miss nature’s interconnections because they happen subtly, beneath the surface. We can’t readily see or hear the way trees communicate. For instance, there’s an invisible landscape of mushrooms and other fungi connecting the root systems of trees in a healthy forest. The underground network allows the trees to interact with one another and even exchange resources. In the summer, shorter evergreens are shaded by the canopies of taller trees. Incapable of reaching the light and photosynthesizing, they call through the fungus for the sun-drenched nutrients they need. The taller trees have plenty to spare, and send it to their shaded peers. The taller trees lose their leaves in the winter and themselves become incapable of photosynthesizing. At that point, the evergreens, now exposed to the sun, send their extra nutrients to their leafless community members. For their part, the underground fungi charge a small service fee, taking the nutrients they need in return for facilitating the exchange.

So the story we are taught in school about how trees of the forest compete to reach the sunlight isn’t really true. They collaborate to reach the sunlight, by varying their strategies and sharing the fruits of their labor.

Trees protect one another as well. When the leaves of acacia trees come in contact with the saliva of a giraffe, they release a warning chemical into the air, triggering nearby acacias to release repellents specific to giraffes. Evolution has raised them to behave as if they were part of the same, self-preserving being.

Animals cooperate as well. Their mutually beneficial behaviors are not an exception to natural selection, but the rule.

Darwin observed how wild cattle could tolerate only a brief separation from their herd, and slavishly followed their leaders. “Individualists” who challenged the leader’s authority or wandered away from the group were picked off by hungry lions. Darwin generalized that social bonding was a “product of selection.” In other words, teamwork was a better strategy for everyone’s survival than competition.

Darwin saw what he believed were the origins of human moral capabilities in the cooperative behavior of animals. He marveled at how species from pelicans to wolves have learned to hunt in groups and share the bounty, and how baboons expose insect nests by cooperating to lift heavy rocks.

Even when they are competing, many animals employ social strategies to avoid life-threatening conflicts over food or territory. Like break dancers challenging one another in a ritualized battle, the combatants assume threatening poses or inflate their chests. They calculate their relative probability of winning an all-out conflict and then choose a winner without actually fighting.

The virtual combat benefits not just the one who would be killed, but also the victor, who could still be injured. The loser is free to go look for something else to eat, rather than wasting time or losing limbs in a futile fight.

Evolution may have less to do with rising above one’s peers than learning to get along with more of them.

We used to believe that human beings developed larger brains than chimpanzees in order to do better spatial mapping of our environment or to make more advanced tools and weapons. From a simplistic survival-of-the-fittest perspective, this makes sense. Primates with better tools and mental maps would hunt and fight better, too. But it turns out there are only slight genetic variations between hominids and chimpanzees, and they relate almost exclusively to the number of neurons that our brains are allowed to make. It’s not a qualitative difference but a quantitative one. The most direct benefit of more neurons and connections in our brains is an increase in the size of the social networks we can form. Complicated brains make for more complex societies.

Threats to our relationships are processed by the same part of the brain that processes physical pain.

Think of it this way: a quarterback, point guard, or midfielder, no matter their skills, is only as valuable as their ability to coordinate with the other players; a great athlete is one who can predict the movements of the most players at the same time. Similarly, developing primates were held back less by their size or skills than by their social intelligence. Bigger groups of primates survived better, but required an increase in their ability to remember everyone, manage relationships, and coordinate activities. Developing bigger brains allowed human beings to maintain a whopping 150 stable relationships at a time.

The more advanced the primate, the bigger its social groups. That’s the easiest and most accurate way to understand evolution’s trajectory, and the relationship of humans to it. Even if we don’t agree that social organization is evolution’s master plan, we must accept that it is — at the very least — a large part of what makes humans human.

Human social cohesion is supported by subtle biological processes and feedback mechanisms. Like trees that communicate through their root systems, human beings have developed elaborate mechanisms to connect and share with one another.

Our nervous systems learned to treat our social connections as existentially important — life or death. Threats to our relationships are processed by the same part of the brain that processes physical pain. Social losses, such as the death of a loved one, divorce, or expulsion from a social group, are experienced as acutely as a broken leg.

Managing social relationships also required humans to develop what anthropologists call a “theory of mind” — the ability to understand and identify with the thinking and motivations of other people. From an evolutionary perspective, the concept of self came after our ability to evaluate and remember the intentions and tactics of others. Unlike the relatively recent cultural changes that encouraged ideas of personal identity or achievement, our social adaptations occurred over hundreds of thousands of years of biological evolution. Enduring social bonds increase a group’s ability to work together, as well as its chances for procreation. Our eyes, brains, skin, and breathing are all optimized to enhance our connection to other people.

Pro social behaviors such as simple imitation — what’s known as mime sis — make people feel more accepted and included, which sustains a group’s cohesion over time. In one experiment, people who were subtly imitated by a group produced less stress hormone than those who were not imitated. Our bodies are adapted to seek and enjoy being mimicked. When human beings are engaged in mime sis, they learn from one another and advance their community’s skill set.

The physical cues we use to establish rapport are preverbal. We used them to bond before we ever learned to speak — both as babies and as early humans many millennia ago. We flash our eyebrows when we want someone to pay attention to us. We pace someone else’s breathing when we want them to know we empathize. The pupils of our eyes dilate when we feel open to what another person is offering. In turn, when we see someone breathing with us, their eyes opening to accept us, their head subtly nodding, we feel we are being understood and accepted. Our mirror neurons activate, releasing oxytocin — the bonding hormone — into our bloodstream.

Human beings connect so easily, it’s as if we share the same brains. Limbic consonance, as it’s called, is our ability to attune to one another’s emotional states. The brain states of mothers and their babies mirror each other; you can see this in an MRI scan. Limbic consonance is the little-known process through which the mood of a room changes when a happy or nervous person walks in, or the way a person listening to a story acquires the same brain state as the storyteller. Multiple nervous systems sync and respond together, as if they were one thing. We long for such consonance, as well as the happy hormones and neural regulation that come with it. It’s why our kids want to sleep with us — their nervous systems learn how to sleep and wake by mirroring ours. It’s why television comedies have laugh tracks — so that we are coaxed to imitate the laughter of an audience of peers watching along. We naturally try to resonate with the brain state of the crowd.

These painstakingly evolved, real-world physical and chemical processes are what enable and reinforce our social connection and coherence, and form the foundations for the societies that we eventually built.

Thanks to organic social mechanisms, humans became capable of pair bonding, food sharing, and even collective childcare. Our survivability increased as we learned how to orchestrate simple divisions of labor, and trusted one another enough to carry them out.

The more spectacular achievement was not the division of labor but the development of group sharing. This distinguished true humans from other hominids: we waited to eat until we got the bounty back home. Humans are defined not by our superior hunting ability so much as by our capacity to communicate, trust, and share.

Biologists and economists alike have long rejected social or moral justifications for this sort of behavior. They chalk it up instead to what they call “reciprocal altruism.” One person does a nice thing for another person in the hope of getting something back in the future. You take a risk to rescue someone else’s child from a dangerous predator because you trust the other parent to do the same for your kid. In this view, people aren’t so nice at all; they’re just acting on their own behalf in a more complicated way.

But contemporary research strongly supports more generous motives in altruism, which have nothing to do with self-interest. Early humans had a strong disposition to cooperate with one another, at great personal cost, even when there could be no expectation of payback in the future. Members of a group who violated the norms of cooperation were punished. Solidarity and community were prized in their own right.

Evolution’s crowning achievement, in this respect, was the emergence of spoken language. It was a dangerous adaptation that involved crossing the airway with the food way, making us vulnerable to choking. But it also gave us the ability to modify the sounds that came from our vocal folds and make the variety of mouth noises required for language.

While language may have been driven by the need for larger, more complicated social structures, think of the immense collaborative act that developing a language required from its speakers. That multi generational exercise alone would change the fabric of society and its faith in a cooperative enterprise.

Mark Barber aka Loose Cannon

0 notes