#durotriges tribe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Durotriges ‘23

#archaeology#archeology#bournemouth uni#iron age#iron age society#iron age hillfort#durotriges#durotriges iron age#durotriges tribe#duropolis#dorset#100 BCE#durotriges big dig#BU big dig#bournemouth archaeology#my finds#all photos are mine

1 note

·

View note

Text

Womens history just got richer.

When the deeply patriarchal Romans first encountered Celtic tribes living in modern-day France and Great Britain in the first century B.C.E., their reaction to the roles of the sexes was one of surprise and dismay. The tasks of men and women “have been exchanged, in a manner opposite to what obtains among us,” wrote one Roman historian.

New evidence from Celtic graves now confirms that at least one part of Britain was a woman’s world long before the Romans arrived—and for centuries afterward. One ancient British tribe known as the Durotriges based its family structure—and perhaps property inheritance—on kinship between mothers and daughters. Men, meanwhile, left home to live with their wives’ families, a practice known as matrilocality that has never been seen before in European prehistory.

The work, published today in Nature, helps explain why women in Iron Age Britain are often buried with high-status grave goods such as mirrors and even chariots, says Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich archaeologist Carola Metzner-Nebelsick, who was not involved with the research. “It’s a fantastic result,” she says. “It really helps explain the archaeological record.”

Ancient histories—not least Julius Caesar’s 50 B.C.E. account of invading Gaul—hinted at female empowerment among the Celts. “They wrote about it because they found it so weird,” says Trinity College Dublin geneticist Lara Cassidy.

Many modern historians assumed the accounts were exaggerated; they dismissed rich female graves from the time as outliers. But over the past few decades, archaeologists comparing burial practices at hundreds of Iron Age sites from Britain to Germany began to think there was a kernel of truth to the Roman reports.

The Durotriges cemeteries, located in the far south of England near the city of Bournemouth, offered a way for Cassidy and her team to investigate. Burials there began around 100 B.C.E., roughly 150 years before Roman forces invaded the island. Unusually for Iron Age Britain, the tribe didn’t cremate their dead. Instead they buried them close to home, in the hills surrounding their farmsteads.

Whereas men were laid to rest with a joint of meat and perhaps a pot containing a beverage to sustain them on their journey into the afterlife, Durotriges women are often found with elaborate offerings including mirrors, combs, jewelry, and even swords. “If you judge social status by burial goods, then female burials have vastly more than male,” says Bournemouth University archaeologist Miles Russell, a co-author of the new paper.

Over the past 4 years, researchers sequenced DNA from dozens of Durotriges skeletons in a set of cemeteries in Dorset, England. By matching identical fragments of genetic material from different individuals, they reconstructed a family tree that spanned six generations—many of whom were female descendants of a single female founder. Two-thirds of the people in the kin group buried in the cemetery shared a rare type of mitochondrial gene, a form of DNA inherited only from the mother, including some of the men who shared the same female ancestor.

Other genetic evidence from the Durotriges cemeteries pointed to matrilocality, showing that men joined the clan from other families. “Women are staying close to family and are embedded in the support network they’ve known since childhood,” Cassidy notes. “It’s the husband who’s coming in as a stranger and is dependent on the wife’s family.” Women were evidently a force to be reckoned with in this part of Iron Age Britain.

Archaeologists have found that members of Great Britain’s Durotriges tribe often buried women with more grave goods than men.Miles Russell/Bournemouth University

Such patterns could help explain finds elsewhere in the Celtic world, where women were sometimes buried with rich grave goods or even chariots. “We’re thinking this could have been quite widespread,” Cassidy says.

To gather further evidence, she and her colleagues re-examined previously published genomes from more than 150 sites in Britain and Europe stretching back to the Stone Age. Starting around 500 B.C.E., the diversity in people’s mitochondrial DNA declined, the team found, suggesting more of them shared the same female ancestors. There was no matching decline in the diversity of Y chromosomes, which are passed from fathers to sons.

That suggests communities across Britain were anchored by specific female lines, with men marrying in from outside. “The signal they see in [the Durotriges] case study can be reproduced in other British sites,” says Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology archaeogeneticist Joscha Gretzinger, who was not involved with the work. “That’s quite a smoking gun.”

The study is part of a growing use of DNA to reconstruct genetic kinship in the deep past—and use it to shed light on the structure of past societies. University of Liverpool archaeologist Rachel Pope says the research is starting to highlight the wide variety of social organization people practiced in the past, something archaeology has hinted at over the past 2 decades.

Some of the earliest kinship studies using ancient DNA, for example, showed that Stone Age farmers in Britain and France living in the fifth millennium B.C.E. were organized patrilocally, with women leaving their homes to marry while men stayed put. The new data from Durotriges suggest that by the Iron Age, 4000 years later, something had shifted. “This is quite exciting,” Pope says. “There are moments in time in which societies seem to have a lot of high female status.”

#Women in history#ancient britain#ancient British tribe known as the Durotrig#matrilocality#Bournemouth

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iron age men left home to join wives' families, DNA study suggests (Nicola Davis, The Guardian, Jan 15 2025)

"Writing in the journal Nature, archaeologists report how they studied the genomes of more than 50 individuals buried in a cluster of cemeteries in Dorset.

Most of these individuals were associated with the Durotriges tribe, a Celtic group that occupied the central southern coast of Britain from about 100BC to AD100.

These sites have previously been of interest to experts, not only because iron age burials are rare but because the women tended to be buried with valuable items more often than the men.

“That is suggesting not much of a status difference between men and women, or even perhaps higher-status burials for women,” said Cassidy.

“How that actually then translates into the role of women in the society, that’s hard to say. And that’s why genetic data adds another important dimension there.”

Cassidy and colleagues analysed DNA and mitochondrial DNA – genetic material from within the cells’ powerhouses – revealing that the majority of individuals were related to each other.

Crucially, many shared the same mitochondrial DNA – genetic material that is passed down only from mothers to their offspring.

“They all were female-line descendants, [from the] same woman,” said Cassidy.

The team say this genetic evidence and modelling work suggest the community was matrilocal: in other words, the women stayed put, with men moving into the group to join their wives.

The conclusion was supported by considerable diversity in the Y chromosome of the men, with males showing significantly lower levels of genetic relatedness to other individuals, and by males being more likely to have different mitochondrial DNA than that which was widely shared.

The team then looked at DNA from other iron age burial sites across Britain, again finding signs of matrilocal communities.

“It’s looking that this is quite widespread across the island by that period,” said Cassidy.

While the study does not reveal whether the iron age societies had tribal groupings organised specifically around the maternal line, or suggest there was a matriarchy, the results offer new insights into the communities.

“Matrilocality is a strong predictor of female social and political empowerment,” Cassidy said, noting that if the women stayed put, they were more likely to inherit, control land, be players in the local economy, and have influence.

Writing in an accompanying article, Dr Guido Alberto Gnecchi Ruscone from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said the findings echoed Roman writings that depicted Celtic women, such as Boudicca, as empowered figures.

“Although Roman writers often exoticised these societies,” he wrote, “the genetic evidence shown by Cassidy and colleagues validates some of their claims about the special role that women had in Celtic Britain.”"

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

'When the deeply patriarchal Romans first encountered Celtic tribes living in modern-day France and Great Britain in the first century B.C.E., their reaction to the roles of the sexes was one of surprise and dismay. The tasks of men and women “have been exchanged, in a manner opposite to what obtains among us,” wrote one Roman historian.

New evidence from Celtic graves now confirms that at least one part of Britain was a woman’s world long before the Romans arrived—and for centuries afterward. One ancient British tribe known as the Durotriges based its family structure—and perhaps property inheritance—on kinship between mothers and daughters. Men, meanwhile, left home to live with their wives’ families, a practice known as matrilocality that has never been seen before in European prehistory.

The work, published today in Nature, helps explain why women in Iron Age Britain are often buried with high-status grave goods such as mirrors and even chariots, says Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich archaeologist Carola Metzner-Nebelsick, who was not involved with the research. “It’s a fantastic result,” she says. “It really helps explain the archaeological record.”'

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ooh this reminds me of the theory I subscribe to regarding the Iron Age peoples who lived in the hillfort at Pen Dinas, Aberystwyth.

This is a map of the Iron Age tribes which lived in Wales (according to the geographer Ptolemy c. 100-170 AD). As you can see, Mid Wales is conspicuously empty and it is not known which tribes lived there. Pen Dinas is the largest hillfort in Wales- yet we do not know who lived there in the Iron Age (when it was significantly expanded). However, we do have examples of Meare Spiral type glass beads from excavations at Pen Dinas (Meare Spiral beads are a type of bead produced in the Meare Lake settlement of Iron Age Somerset). In addition to this, pottery has been found which usually comes from the West Country area at Pen Dinas.

This is a map of the Iron Age tribes living in Southern England at the end of the Iron Age. Meare Lake is in the territory marked Belgae. But the Belgae didn't always live in Britain. They originally lived in the area which is now the Low Countries and the name Belgae is the origin of the name Belgium. Because of the Romans, the Belgae were displaced and many settled in Britain and in theory- displacing the Britons who were already living there (possibly sub groups of the Durotriges, but we can't be certain). We know that the group originally living at Meare Lake were displaced as we find Meare Spiral beads in mid Wales and in the far North of Scotland (production of beads by this group continued using the same techniques. No other group in Britain manufactured beads like this or in the same way, indicating that these craftsmen are likely displaced people from Meare Lake).

The top image is of the reproduction Meare Spiral beads that I have and the bottom image is a display from the Museum of Somerset with the beads my reproduction is based on.

So, with all this in mind- personally I think that the theory that the people who lived at Pen Dinas / in Mid Wales generally in the Iron Age were likely displaced tribes from Southwest England is one which holds water. This has been my impromptu tedtalk!

Actually, ancient glass, having been rather neglected by archaeology for decades, is a pretty exciting topic in scholarship right now. The main thing is that glass persists–it’s very stable. After fabric rots and metal turns to a scrap of rust, there will lie a necklace, still scattered across a chest that itself has turned mostly to earth.

Bead typologies, for example (that is, the classification of different styles/shapes/decorative motifs/colors) can allow scholars to trace trade routes, as they study the distributions of different bead types over time and geography. Glass production is kinda industrial in nature, not like spinning or beer that make good cottage industries. It was often produced in one place, and then sold on to artisans elsewhere, and then the beads themselves were traded across entire continents.

Chemical analysis of the glass can do even more to trace routes, since different compositions and incidence of different mineral contaminants can allow archaeologists to trace glass production to individual sites, thousands of years after the fact. It’s dizzying, really.

The downside is that for a long time, archaeologists regarded beads as unimportant trinkets, and antiquities dealers understood that they were easy to take and easy to move. So an awful lot of the most exceptional beads we have from the distant past spent time in private collections or uncategorized drawers somewhere in a museum back room, so they’ve lost much of what we could have learned from their original provenance. Maybe we’ll be able to turn new analytical tools on some of these to reconstruct more of their past.

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

Corfe Castle & Village - Dorset - UK

The castle stands above the village and dates back in some form to the 10th century. It was the site of the murder of Edward the Martyr in 978. During the English Civil War it was a Royalist stronghold and was besieged twice, in 1643 and again in 1646. It is currently owned by the National Trust and is open to the public.

Burial mounds around the common of Corfe Castle suggest that the area was occupied from 6000 BC. The common also points to a later Celtic field system worked by the Durotriges tribe. Evidence suggests that the tribe co-existed with the Romans in a trading relationship following the Roman invasion c. 50 AD.

The name "Corfe" is derived from the Saxon word, ceorfan, meaning to cut or carve, referring to the gap in the Purbeck hills where Corfe Castle is situated.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Corfe Castle, Dorset, England

(c) do not use, edit, reupload

Burial mounds around the common of Corfe Castle suggest that the area was occupied from 6000 BC. The common also points to a later Celtic field system worked by the Durotriges tribe. Evidence suggests that the tribe co-existed with the Romans in a trading relationship following the Roman invasion c. 50 AD.

The name "Corfe" is derived from the Old English word, ceorfan, meaning to cut or carve, referring to the gap in the Purbeck hills where Corfe Castle is situated.

The castle stands above the village and dates back in some form to the 10th century, and the motte and bailey was first built by William I (the Conqueror). It was the site of the murder of Edward the Martyr in 978. During the English Civil War it was a Royalist stronghold and was besieged twice, in 1643 and again in 1646. [x]

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2000-Year-Old Tombs With Five Bodies Discovered in U.K.

Archaeology students have uncovered the 2,000-year-old remains of five bodies on land close to Britain's earliest recorded town.

The historic burial ground which dates to around 100BC, was discovered by university undergraduates on farm land at Winterborne Kingston, near Blandford.

The site is thought to have been an outcrop of the prehistoric town of Duropolis, named after the local Iron Age tribe the Durotriges.

The town, which was discovered in 2008, was older than Colchester and Silchester, which had been regarded as Britain's earliest towns.

The oval shaped settlement of four roundhouses on the outskirts of Duropolis was later abandoned by the group of 40 people who lived there.

Decades later their descendants returned and ceremoniously laid to rest their dead.

The bodies were interned in ditches, originally used to store grain, along with sacrificial animals given as an offering to their pagan gods.

The one acre burial ground was found by students of Bournemouth University last September.

After months of planning and research, excavations began three weeks ago.

So far they have found the remains of three women and two men buried on the site consisting of around 75 ditches, between 3ft and 8ft deep.

They will help to build a 'unique and unparalleled picture' of life for the Iron Age people.

Dr Miles Russell, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University, said: "Iron Age settlements have been found across the country before but finding the people who lived there is really very unique.

"This is such an unusual site because Iron Age people did not tend to bury their dead but here in Dorset it was very different.

"We can see that people in Dorset buried their dead but we have no idea why. These skeletons are providing a whole range of information that you would not find anywhere else in the country.

"Along with the 50 other skeletons we have found in the area over the last decade, they help us to build an unparalleled data set." The oval shaped settlement was built around 100 years before the Roman invasion of Britain.

The pits were originally used to store grain but repurposed as burial units after the farmstead was abandoned in around 30BC.

The discovery sheds new light on the unique burial rites of Iron Age settlers in Dorset.

As an offering to their pagan gods, relatives of the dead placed animal sacrifices beneath their bodies at the bottom of the ditches.

Dr Russell said: "The bodies we found here were buried after the site was abandoned between 30AD and 10AD - the eve of the Roman invasion.

"They were probably descendents of the people who used to live at the farmstead and were taken there to be close to their ancestors. "The pits were originally used to store grain or as cold stores for food. We think they are just a sample of what's beneath the surface and we hope to find more bodies in the coming weeks.

"This would have been quite a small settlement, effectively a prehistoric suburb of the larger Duropolis. We'll do DNA analysis of the skeletons to see how closely related they were to bodies we have found elsewhere in the area.

"We're hoping to slice through time to establish lines of descent, interpersonal relationships, and common ancestry.

"One we're finished, we'll rebury them back in the landscape they would have known.

"This work will give us a vital understanding of ordinary people and their everyday lives and religious practices.

"At the bottom of the pits are sacrificed horses and cows. They were cut into sections and a torso of a cow would have the head of a horse attached to it.

"It is a strange macabre jigsaw of sacred animals offered to their gods. This is information we just would not find anywhere else."

First discovered in 2008, Duropolis was a huge open occupation seen for miles around, at a time when hillforts were still common.

It is the largest unenclosed settlement yet uncovered in the UK and had more than 150 roundhouses in an area of four hectares, as well as storage facilities, animal pens and agricultural outbuildings.

The site shows that towns weren't introduced by the Romans, as many people believed, but existed at least 100 years before they invaded.

The newly-unearthed farmstead is roughly half a mile to the north west of Duropolis.

Once the 65 undergraduates have finished at the current site, they will use sophisticated technology to scan the surrounding areas for further archaeological structures.

#2000-Year-Old Tombs With Five Bodies Discovered in U.K.#archeology#archeolgst#ancient graves#ancient tombs#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

English History (Part 8): The Anglo-Saxons

In 430, Vortigern hired Saxon mercenaries to defend England against the Picts (from Scotland) and marauding bands from Ireland. Vortigern was the leader of the confederacy of small kingdoms that England was divided into, and this was a common strategy (the Romanized English had used it at various times).

The Irish landed on the west coast of England, within easy reach of the Cotswolds. The central part of Vortigern's kingdom was situated in that region, so that may have been the reason he was the leader in this struggle. The Picts, it was reported, had landed in Norfolk. The sailors painted their ships and bodies the colour of the waves, so they couldn't be seen so easily.

According to historical legends, the Saxons arrived in three ships, each holding 100 men at most (there were probably more ships than that). The Saxon mercenaries were well-known for their ferocity and valour. They worshipped Woden (god of war) and Thor (god of thunder), practised human sacrifice, and drank from their enemies' skulls. They shaved the front of their heads, and grew their hair long in the back, so their faces would seem larger in battle. A Roman chronicler of the 400s stated, “The Saxon surpasses all other in brutality. He attacks unforeseen, and when foreseen he slips away. If he pursues, he captures; if he flees, he escapes.”

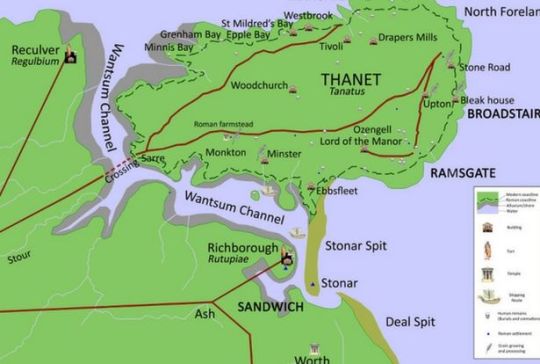

The main part of the Saxon force was stationed in Kent, and they were given the Isle of Thanet in the Thames Estuary. Other groups of soldiers were stationed in Norfolk, and on the Lincolnshire coast; they also guarded the Icknield Way. The remains of the Romanized armies (in the north) were stationed in York, which was strongly fortified.

The Wantsum Channel no longer exists, so the Isle of Thanet is now part of the mainland.

This show of strength seems to have been enough. The Picts gave up their plans for invasion. The Irish were held back by the tribal armies of the west and west midlands; the kingdom of the Cornovii (with their capital at Wroxeter) played an essential part in this.

But Vortigern's allies either would not or could not pay the Saxon mercenaries, and also refused to give them land instead of coin. According to the Kentish chronicles, the English declared that “we cannot feed you and clothe you, because your numbers have grown. Leave us. We no longer need your assistance.”

The Saxons immediately rose up, with the uprising beginning in East Anglia and spreading down to the Thames Valley. They took over many of the towns & countryside regions in which they had been stationed; they appropriated large estates and enslaved many of the native English. Then, the Saxon federates encouraged their compatriots to come and join them. The land was prosperous, and Thanet itself, as a granary, was especially prized.

Four main tribes provided most of the migrants – the Angles (Schleswig), Saxons (regions around the River Elbe), Frisians (north coast of the Netherlands) and Jutes (coast of Denmark). The river system provided already-established routes of settlement, so the settlers advanced along the Thames, Trent and Humber.

The Angles settled in east and north-east England, and by the early 500s, the people of east Yorkshire were wearing Anglian clothes. The Saxons settled in the Upper Thames valley; the Frisians were scattered over the south-east, with an important influence in London. The Jutes settled in Kent, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight (the New Forest was once Jutian land).

In some places, the Anglo-Saxons (who weren't called that yet) were welcomed; in other places they were resisted. In some places, they were accepted by the working population who had no real love for their native masters. Eventually, the Anglo-Saxons made up about 5% of the population we now call English, and it may have been about 10% in the eastern regions. However, there is no evidence for the deliberate genocide and replacement of the native population.

One of the reasons for their migration to England was that they were being pushed westwards by other tribes in the great westward migrations of that time period. Another reason was the rising sea, which was causing the northern European coastline to sink.

The Saxon revolt led to the downfall of Vortigern, who was overthrown by Ambrosius Aurelianus, another Romanized English leader. Aurelianus led a counterattack against the Saxons, and engaged in a series of battles that lasted for 10yrs. In 490, the English won a great victory at Mons Badonicus, which was probably near modern-day Bath.

The leader of the English forces for that battle is unknown. However, the name of Arthur is mentioned as dux bellorum (leader of warfare), and he is said to have taken part in 12 battles against the Saxons. He may have been a military commander with his headquarters within the hill fort of Cadbury. During his supposed lifetime, 7.2 hectares of that hill fort were enclosed.

However, as part of the spoils of war, the Saxons kept control over Norfolk, East Kent and East Sussex. There was a division in the country – Germanic tribes with their warrior leaders to the north, and small English kingdoms to the south. The division may have been marked by the construction of the Wansdyke, designed to keep the Saxons from crossing over into central southern England.

Some of the most Romanized parts of England were now controlled by “barbarians”, and so the town and villa life receded greatly. Gildas (an English chronicler of the early 500s) complained that “the cities of our contry are still not inhabited as they were; even today they are squalid deserted ruins.”

However, some of these towns and cities were still actively used as markets and places of authority. The Saxons set up their own trading area outside the walls of London (the modern-day district of Aldwych), but the old city of London was still a place of royal residences and public ceremonial activities.

In the countryside, things carried on much as usual, and there wouldn't have been any changes in agricultural practice. The Germanic settlers laid out the same field systems, and respected the old boundaries – for example, Germanic structures in Durham were set within a pattern of small fields & drystone walls from prehistoric times.

Furthermore, the Germanic settlers respected the lie of the land, and formed groups that followed the boundaries of the old tribal kingdoms. At a slightly later date, the sacred Saxon sites followed the alignment of Neolithic monuments.

For the next 2-3 generations, the English kept the Germanic settlers within their boundaries. At this time, the average life expectancy was 35 years.

But by the middle of the 500s, the Germanic peoples wanted to advance further west, to exploit the productive lands there. The main reason for this sudden expansion probably was the bubonic (and perhaps pneumonic) plague that spread from Egypt to all over the previously-Romanized world, during the 540s. The native English were struck down by it (and the Germanic peoples weren't), and the population may have dropped from 3-4 million to 1 million. There were fewer people living on the land, and fewer men to defend it. The Angles and the Saxons took advantage and moved westwards.

Ceawlin of Wessex, one of the Saxon leaders, reached as far as Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath by 577. Seven years later, his forces had penetrated the midlands, and the native kings were deposed. This was the pattern throughout England.

Pressure was growing on the Durotriges (Somerset & Dorset), and many native people left for Armorica, on the Atlantic coast of north-western France, where their leaders took control of large areas of land. They may have been welcomed there, as they may have been part of the same tribe. The region of Brittany emerged there, and the Bretons retained their old tribal allegiances, never really thinking of themselves as part of the French state. Some returned to England – the forces of William the Conqueror included a Breton contingent, and they chose to settle in south-western England.

Eventually, the native English would be mixed with the settlers, and terms like Saxon or Angle would no longer have any meaning – everyone would be English. But it was a slow process. 200yrs after the first Saxons arrived, much of western England was still under the rule of native kings. The kingdom of Elmet (now the West Riding of Yorkshire) survived until the early 600s. The “Anglo-Saxon invasion” really only came to an end in 1282 when Edward I captured Gwynedd (leader of a kingdom in north-western Wales). There were still Celtic speakers in Cornwall at the beginning of the 1500s, and the language didn't die fully until the 1700s.

#book: the history of england#history#military history#colonialism#anglo-saxon settlement of england#battle of badon#britain#anglo-saxon britain#england#wales#saxons#angles#frisians#jutes#wessex#durotriges#elmet#vortigern#ambrosius aurelianus#king arthur#ceawlin of wessex

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeology: Researchers left stunned by 2000-year-old Iron Age death pit: ‘Frankly bizarr | Science | News

Archaeology: Researchers left stunned by 2000-year-old Iron Age death pit: ‘Frankly bizarr | Science | News

The oval shaped storage pits are thought to have originally been used to hold grain. Five humans in total were discovered in the pits, which is located in present-day Dorset. The Iron Age settlement has been dubbed Duropolis due to it once being a thriving farming settlement and is thought to have been occupied by the tribe known as the Durotriges. Over the last three weeks, the team of 65…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

November 24th, 2019

Day 3: Bath, The Home of the Roman Bath

Last night’s sleep was very comfortable, especially given the ongoing need to adjust to the time here and the constant realization that not sleeping on the plane would leave us with residual sleep deprivation that would follow along with us for awhile. It was really hard to get out of the warm bed this morning but free breakfast was calling and we couldn’t miss our chance at free breakfast!

And the breakfast was super worth it! Instead of sitting down at a table and being provided some slices of bread and jam, some yogurt, and some fruit like you usually get at run-of-the-mill lodgings around the world, we were given a simple menu of breakfast options to choose from. Whoa, we get to pick!? And pick we did! Cynthia ordered a Full English Breakfast and I had an Eggs Benedict with Ham. Both were delicious and a great surprise for breakfast. After lounging around the comfy breakfast area for a bit while sipping our tea and coffee, we eventually got up to pack and check out of the inn.

We drove into Bath and luckily found a parking garage that was located conveniently close to midtown and didn’t charge a ransom. After figuring out how to pay for parking, we proceeded to walk into town. At first glance, Bath was a typical European city with some walkable downtown pedestrian-only streets and alleys with tourist attractions and abbeys to see and restaurants and shops to explore. But given the season, Bath was all Christmas-ed up in preparation for the upcoming Christmas holidays! Storefronts were decorated with Christmas decorations. Christmas music was playing everywhere. And people were setting up Christmas market stalls for the upcoming Bath Christmas festival and market, a big deal in the area around the holiday season.

Our first stop in Bath was the Ancient Roman Baths, the namesake for the city. It ended up being a long stop given how much more there was to see and learn at this attraction than just the Roman baths preserved from long ago. There was so much history behind the baths, the city, and the people who once lived here and those who settled here from the Roman Empire afterward. And the entrance fee covered an audio-guided tour, which made it easy to stay and learn as much as possible about the baths. We probably spent around two hours at the Ancient Roman Baths learning all about old Britain back in the day, the Ancient Romans, and these historic baths before finally leaving to check out the rest of the city.

Like previous places we had visited, we strolled through town and stopped by stores and shops here and there to check them out. We stopped at Bath Abbey before spending some time in Mr. B’s Emporium Bookshop, a fun and rather large bookshop with tons of books, before leaving to find a place for afternoon tea. We peeked at one or two tea shops before deciding that we’d hold off on tea until later in the afternoon to make the most of the opportunity to see Bath before the late afternoon darkness arrived. So we continued to tour Bath, stopping by the Pulteney Bridge and Laura Place Fountain and then roaming around random streets until the daylight dimmed.

By dusk, we were ready for afternoon tea. But the afternoon tearooms weren’t ready for us. A lot of them were already closed or close to closing time. We walked through town once or twice trying to find open tea shops to stop at before finally settling on a place called Sweet Little Things. By the time we actually got there and sat down, the kitchen was closed for the day and all that was available were whatever pastries or cakes they had at the front counter. So we ordered the orange and lavender cake with some hot chocolate to enjoy within the warmth of the restaurant.

It was nice to sit down and relax for a bit after a full day of walking the town. But eventually we left to explore just a tad bit more before deciding on a place for dinner. Given that we just had some cake, we weren’t starving but thought it was a good idea to get some dinner before the long drive to our AirBnB near London Heathrow. Ultimately, after throwing some ideas out there, we decided on getting Nando’s for dinner! Yup, THE Nando’s! A Portugese chicken restaurant that holds a special place in my heart ever since I first had it back in 2010 in Brisbane and a place that is surprisingly hard to come by in the U.S.

Thinking that we were hungrier than we actually were, we ended up ordering a full chicken combo meal with four sides. It was delicious but by the end of it all, we had so much food left over to take home with us. WHY DID WE ORDER A FULL CHICKEN!? Should’ve known better! But it was delicious and an easy meal without putting much thought and effort into looking for a new and unique place on TripAdvisor to try for dinner.

With our bellies full of delicious food, we walked around the dead quiet streets of downtown Bath one last time to digest half the chicken we ate before getting our car and starting our return trip back to the London area, where we were staying for the night before a really early flight out to Edinburgh in the wee hours of the morning.

5 Things I Learned Today:

1. You can hear birds chirping in England at 2AM in the morning. WTF.... Whyyyyyy???

2. Bath, also known back in the day as Aquae Sulis, is known for its Ancient Roman baths, discovered in the late 19th century. At that time, the Roman baths and a temple were discovered in the area. The actual bath was likely already constructed by 69 AD based on historical evidence but the springs were used earlier by local tribes, like the Dobunni and the Durotriges, likely long before the Romans came to Britain in 43 AD.

3. Beware: tea houses close early. I guess that makes some sense since you should eat dinner at some point in the day and if you have afternoon tea TOO late, you probably won’t make it to dinner.

4. In order to use prepaid Vodafone (or other) SIM cards in the UK with a foreign phone that isn’t used to using prepaid SIMs, you have to change some of the addresses (like the APN and WAP) to pp.vodafone.co.uk (for Vodafone SIMs, at least). Make sure you do this for multiple addresses (as seen above) in your phone settings so that if you need to create a personal hotspot, you can as well. Didn’t learn this until stopping by a Vodafone store to troubleshoot the personal hotspot issue we were having.

5. A lot of sinks in England are somewhat old school and run hot and cold water through separate faucets. WHY???? How do I get warm water without a cup to mix it in?? Why must it be so difficult??

#withabackpackandcamera#huyphan8990#travelblog#travel#blog#Europe#England#Bath#2019#RomanBaths#AquaeSulis#afternoontea#photography#landscaphotography#travelphotography#hotchocolate#BathAbbey#Christmas#Nandos

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

The Durotriges were the Celtic tribe that lived in Maiden castle and the surrounding areas. Some useful timeline research here.

0 notes