#dung cake amazon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

desi cow dung cake

Discover the natural power of Desi Cow Dung Cakes. Handcrafted with care, these organic wonders are rich in nutrients and environmentally friendly. Enhance your gardening and agricultural practices with this traditional, sustainable solution. Buy premium quality cow dung cakes now.https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes

Text

The Significance of Cow Dung Cakes in Pooja Ceremonies

Introduction: In the rich tapestry of Hindu rituals and ceremonies, the use of cow dung cakes holds a significant place. These cakes, traditionally made from the dung of cows, are not only an emblem of rural life but also symbolize purity, fertility, and prosperity. In this article, we delve into the profound significance of cow dung cakes in pooja ceremonies, exploring their spiritual, cultural, and practical dimensions.

Historical and Cultural Context:

Cow dung has been revered in Hindu culture for millennia. The cow is considered sacred in Hinduism, symbolizing motherhood, nourishment, and the divine.

The use of cow dung cakes dates back to ancient Vedic rituals, where they were burned as fuel for sacred fires (yagnas) and homas.

In rural India, cow dung has been utilized for various purposes, including fuel for cooking, plastering walls, and as fertilizer for crops.

Spiritual Symbolism:

Cow dung is believed to possess purifying properties, both physically and spiritually. Burning cow dung cakes during pooja ceremonies is thought to cleanse the environment of negative energies and impurities.

The smoke produced by burning cow dung is considered auspicious and is believed to carry prayers and offerings to the gods.

Additionally, cow dung is associated with the goddess Lakshmi, the embodiment of wealth and prosperity. Burning cow dung cakes is believed to invite her blessings into the household.

Practical Application:

Cow dung cakes are still widely used in rural and urban areas of India for conducting various religious ceremonies, including weddings, festivals, and daily prayers.

The cakes are meticulously prepared by mixing cow dung with hay or straw and shaping them into uniform patties. They are then dried in the sun and stored for future use.

Despite the advent of modern fuels, many households continue to prefer cow dung cakes for their pooja ceremonies due to their spiritual significance and accessibility.

Environmental Sustainability:

The use of cow dung as a renewable resource aligns with principles of environmental sustainability. Unlike fossil fuels, cow dung is a renewable and eco-friendly source of energy.

By utilizing cow dung cakes for pooja ceremonies, individuals contribute to the conservation of traditional practices while minimizing their carbon footprint.

0 notes

Text

Cow Dung Online In Vizag

Looking for high-quality cow dung online. Our store offers premium organic cow dung, rich in nutrients and perfect for fertilizing your garden. Buy now for natural and sustainable plant growth. Boost your soil's health with our nutrient-dense cow dung. Order today and see the remarkable results in your garden. https://daasoham.com/

0 notes

Text

Cow Dung Cake Amazon

Shop high-quality cow dung cakes on Amazon for traditional rituals, gardening, and eco-friendly fuel. These organic and odor-free cow dung cakes are perfect for improving soil fertility and promoting sustainable practices. Harness the power of nature with these versatile products. https://daasoham.com/

0 notes

Text

Release Day Blitz Boondocks: An Asian Evil Apocalyptic Thriller by Jaydeep Shah

Boondocks: An Asian Evil Apocalyptic Thriller

Survive the Doom

Book One

Jaydeep Shah

Genre: Apocalyptic Thriller

Publisher: Rage Publishing

Date of Publication: June 9, 2022

ISBN:9781734982657 (eBook)

ISBN: 9781734982664 (Paperback)

ISBN:9781734982619 (Hardback)

ASIN:B096WRWG1D

Number of pages:383 pages

Word Count: 74,668 words

Cover Artist: bookcoverzone.com

Book Description:

They believe it is only about defeat and escape.

Little do they know; it is something more than that. It is about the rise of the dead and the world’s destruction.

Lost in the desert of Rajasthan, India, Rahul and Elisa learn the truth about a wicked wizard named Dansh and some enchanters performing resurrection rituals.

Though they try to stop him, Dansh knows black magic and they find him a challenging adversary. Even worse than him, Rahul and Elisa soon discover that the churel named Dali has returned. Soon, the King of the Underworld, an immortal rakshasa named Sekiada, will make his way to the earth with the force of his thousands of fallen angels to conquer the world.

Rahul and Elisa must find a way to stop them and save humanity.

Terror inflames the nation. The country’s best commando, Aarav Singh, and the best local police officer, Arjun Rawat, reach the city’s border near the desert with the force of gifted soldiers to commence battle against evil. They turn the border into a battlefield to prevent the demons from entering the city.

The apocalypse is struggling to reach its highest peak as the Asian evils slowly spread across the nation: churels, rakshasas, pishachas, daayans, shaitans, and many more hair-raising bloodshed lovers.

Rahul must find a way to murder the immortals: the wicked wizard, the king of the Underworld, and the strongest churel of all time, and Elisa must gather her own courage to battle the demons, especially one of the immortals, to prove women are not weak.

Welcome to the world of horror, where the characters play games of deceit and betrayal to achieve their goals, and the demons enjoy slaughtering the humans.

The end is near. Or it’s just the beginning!? Dare to witness the apocalypse, but only if you are comfortable with bloodbath and barbarity.

Book Trailer: https://youtu.be/QtcQ7QB36bU

Amazon US Amazon UK Amazon CA

Amazon AU Amazon IN BN

Kobo Author Website Goodreads

Excerpt: PROLOGUE 5000 years ago Rajasthan, India

In the small, secluded village Kendraa somewhere in the middle of 500,000 km2of desert and home to only about three hundred or so people, residents halted their work of woodcutting, ceramics, and making dung cakes and rushed into their Wigwam huts. Five minutes passed, and then the village’s mukhiya, Ram, a fifty-five-year-old who looked like he was thirty, began to patrol, scrutinizing whether everyone had secured themselves in their huts. From the way the villagers had run and how Ram was inspecting the village, it was crystal clear that it was their routine; each of them was aware of the regular impending doom that escalated at or after dusk.

After everyone had locked themselves in, and when Ram found no one outside still working or wandering around, he locked himself in his own hut. Two other huts flanked it on each side, and they stood only a few inches away from the dirt road.

In one of the huts near to Ram’s, a child sat with his father.

“I’m scared, papa,” said a boy after a brief look at his father,who was sitting on the ground against the wall.The man securedhis child in a hug with an expression of dread, startled at his son’s rush of feelings. Then he forced a fake smile, patted his son’s back, and kissed his forehead, assuring him that he was safe with his dad.The boy’s fear vanished, and he smiled back. All the while, the child’s mother sat against the wall opposite, hugging her knees and crying silently, keeping her face hidden in the hollow between her legs and breast to prevent scaring her son.

In one of the other huts, another wife cried, this one hugging her husband.

“She ate my brother last month, my sister last week, and your brother yesterday. I don’t want to lose you.”

She was talking about an evil lady who visited the village after dusk and enjoyed massacring humans and eating their flesh.

A sense of apprehension dangled over every hut. * * *

At the end of the desert, in a cave a few miles away from the village’s border, a churel (witch) named Dali glowed in the moonless night.She began to consume negative powers from the environment, levitating herself with her eyes closed and hands wide open. Dali, whom no one could kill with any weapon known to man, appeared out of nowhere about a year ago and had resided in the cave near Kendraa Village ever since. She did this not only because she had found humans to hunt but also for her own security.

Though it was true no one could kill her with any type of known weapon, the villagers didn’t know that she had a fatal flaw: she could be captured in any object and killed by fire. She knew if she began hunting humans in a bigger kingdom, a king might find a tantrik, the one who has thorough knowledge about mysticism and magic rituals, rishi (a sage), or someone else with this knowledge. They might capture with the help of a devotional hymn, black magic, tantra, or curse, or even execute her. But Kendraa Village was secluded; very few people knew about it, and it was rare that a traveler or a rishi passed by.

The villagers believed in God. They worshipped God, day and night, and they knew devotional hymns well. Yet, there was no one strong enough to use one against Dali—not enough to weaken her and capture her, and certainly not to terminate her. That was the reason Dali was completely safe here. * * *

“I have heard that churels become strong on the moonless night,” said a teenage girl to her sister in the hut that stood in the center of the village. “Is it true? And if it is, how?”

“Everyone believes it,” said the sister. “So it must be. I don’t know exactly how.

But people say the negative vibes we spread every day through our anger, jealousy, and other bad feelings become the churel’s fuel. She sucks this energy on the moonless night, and she becomes much more powerful.” * * *

The wind whooshed as Dali exited her cave. Ten feet tall and two hundred years old, she was an ugly churel with a wrinkly dark face. She walked toward the village on her abnormal feet, which pointed backwards, looking around with her pure-white eyes and smiling broadly, showing her uneven, rotten teeth. When she was halfway to the village, she began to levitate, gliding the rest of the way with lightning bolt speed.

When she reached Kendraa, Dali halted in the air over the huts in the center. She looked around with a grin on her face, happy to find everyone had locked themselves in their huts due to the terror she wrought.

She let out a booming laugh in her croaky voice.

“She’s here,” screamed a girl, hiding under a blanket in horror.

“Everything will be alright, sweetie,” whispered the girl’s mom, stroking her back.

The girl stayed quiet, not reacting to her mother’s warmth.

“On this moonless night, I will gain more powers. I will become immortal,” Dali’s voice rang out, loud enough to enter every ear inside the huts.“After having the flesh and blood of more than two hundred.”

Camels grunted from where they weretied to skinny wooden posts, yearning to run away to protect themselves.

Everyone stayed absolutely quiet, trying not to breathe to avoid producing even the slightest sound, sweating profusely in trepidation of their death. Dali’s cackle wafted through the air, scaring the hell out of the villagers who were praying to God for help.

Suddenly, the camels rose into the air. Dali then began to squeeze their bodies by only staring at them and clenching her right fist. She sucked out their blood,which floated out of the animals’ crushed bodies and into her mouth.

The night grew darker, and the wind whooshed faster and faster, rapidly swirling the sand in the air, as if Mother Nature herself was upset for the innocents.

The empty bodies of the camels fell to the ground; it seemed as if they were not corpses but bags full of shattered skeletons. No trace of blood or flesh remained. Dali licked the blood from her lips.

Her eyes rolled over the huts as another grin came over her face.

The villagers’ hearts beat even faster; they knew their death was nearing. All of them wished for a miracle that could save them from Dali. They continued praying; many of them asked for God himself to come to earth and end Dali’s after-life.

Each day before now, Dali had come to Kendraa to kill only one of them, but tonight seemed special for her. She seemed to want to have a party. She wanted to kill almost the entire village in a bid to become immortal, and now only God could save them. Or, more precisely, their courage and hidden skill to fight the churel. Their ability to sing a devotional hymn, find the courage to face the churel and the courage to fight her. That could save them.

Dali soared in the air, glaring at the huts and generating a violent fire bolt. The huts suddenly ignited in fire and everyone rushed out. Seeing the villagers trying to run away from her, screaming in angst, Dali laughed aloud.She was enjoying this more than she had on any other night.

She began capturing people—children, youngsters, women, even those who were pregnant, elders—stopping them from escaping one after the other and consuming them. The desert reverberated with the villagers’ gut-wrenching screams. Ram and some other villagers had managed to escape her grasp, and they now stood on the dirt road, watching as she killed their friends and neighbors. They felt miserable watching their beloved ones die, but they were also afraid and helpless.

As mukhiya of this village, it was Ram’s duty to keep everyone safe from the outsiders, solve the issues between the villagers, and make sure there was no crime. He was the decision-maker for the inhabitants and caretaker of the village.

He had to come up with something to save them all from this bloodthirsty churel.

He looked around with wet eyes, hoping to find something that could help him kill Dali. However, before he could find something, in the distance to his right, his blurred vision glimpsed a man-like image coming toward him. He rubbed his eyes and squinted to get a better look.

Ram saw a rishi, about seventy years old, coming out of the darkness. He had a divine muscular physique and was walking toward him, holding a kamandal (container for holy water) in his hand.

Hearing the churel’s laugh and the villagers’ painful screaming, the rishi paused, fixing his glower on Dali. Then he paced to the village and stopped beside Ram. He looked into Ram’s wet eyes, down to his folded hands and then back to his face. He understood that Ram was requesting he saves his village and the villagers, as many had done so before in other towns and villages plagued by cruel kings, asuras, or churels.

The rishi marched toward Dali in rage.

Dali stopped her killing and locked her fury-filled eyes onthe rishi, who stood right before her.

“Stop killing these innocents,” he said in a voice full of strict, threatening order.

“Or, I’ll have to kill you.”

“I’m powerful,” said Dali, laughing at him. “You can’t kill me; you’re just a human.”

Dali’s mind was full of her own ego; she had beeneasily killing the villagers for a year. In her arrogance, she had forgotten that this rishi could set her on fire and end her terror forever. In this moment, she believed she was the most powerful being on the earth.

“How dare you call me an ordinary human,” he raged. “You have made a life-threatening error. I’m a divine rishi. I warn you one last time to leave this place.”

“I’m not afraid of you, ordinary human,” sneered Dali.

The rishi shifted the kamandal to his other hand and took some holy water from it.

Dali kept grinning at him. “You can do nothing.”

Enraged at the insult, the rishi replied, “I curse you—if you kill one more human, his blood will turn into poison for you, and you will burn in an intense fire.”

With that, he threw the water onto her body.

“Let’s see who wins!” said Dali, staring at him, her voice showing her importance.

She extended her arm and grabbed a young pregnant woman nearby by the neck. Her husband screamed and ran after his wife. When Dali brought the woman near her face, she glanced at the rishi, before locking her gaze onthe woman’s scared eyes, and without pause, she thrust her sharp nail into the woman’s stomach. She pulled it back out, and she showed the nail, dripping with the woman’s blood, to the rishi. She was mocking him—his curse would fail.

The rishi stared at her with his intense look of anger, and when Dali brought the nail to her mouth to suck the blood, a lightning bolt struck her.It was as if her negativity—which she had spread throughout the galaxy—was coming back for her. She roared in pain.

The rishi smiled, seeing his curse had worked, and he happily murmured, “Har Har Mahadev!”

Dali began to cough and choke, and the pregnant woman slipped from her hand.

Dali tried to attack the rishi, but the poison spread through her body swiftly, stopping her powers and weakening her.

The villagers watched in awe as her body began to steadily turn green. Before she died, she said, “I’ll return. I’ll return, immortal.”

The poison spread through her nerves from top to bottom and choked her completely. Her paralyzed body, now completely green, fell to the ground and ignited in fire.

The villagers stared at her burning body, blank expressions on their faces.

Meanwhile, Ram quickly ran to the rishi and touched his feet to have his blessings.

The rishi gave a quick touch to his head. “Long live,” he blessed.

After Dali’s dead body had turned to ash, the rishi sprinkled some holy water on it, and it disappeared. The villagers bowed to him, an act of thanks for protecting them from the wicked churel, and after showering his blessings on them, he left the village.

About the Author:

Jaydeep Shah is an avid traveler and a multi-genre author. As a bachelor’s degree holder in Creative Writing, he aims to entertain as many as people he can with his stories. He is best known for Tribulation, the first book in the “Cops Planet” series.

In addition to those books, The Shape-Shifting Serpents’ Choice, Jaydeep’s first young adult flash fiction written under his pen name, JD Shah, is published online by Scarlet Leaf Review in the July 2019 issue. Currently, he’s endeavoring to write a debut young adult fantasy novel while working on a sequel to his first apocalyptic thriller, Havoc.

When Shah is not writing, he reads books, tries new restaurants, and goes on adventures.

Website: www.jaydeepshah.com

Instagram: www.instagram.com/imjaydeepshah

Facebook: www.facebook.com/imjaydeepshah

Twitter: www.twitter.com/imjaydeepshah

Pinterest: www.pinterest.com/imjaydeepshah

a Rafflecopter giveaway

0 notes

Text

To Find Hope in American Cooking, James Beard Looked to the West Coast

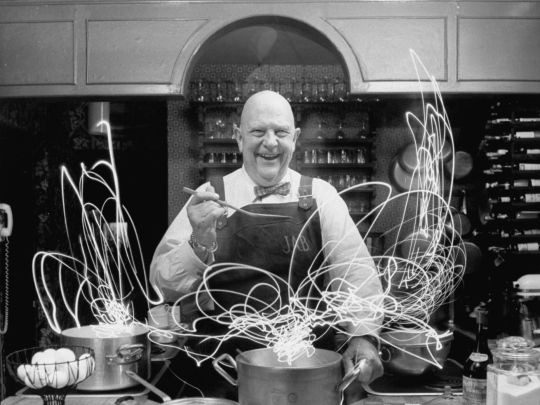

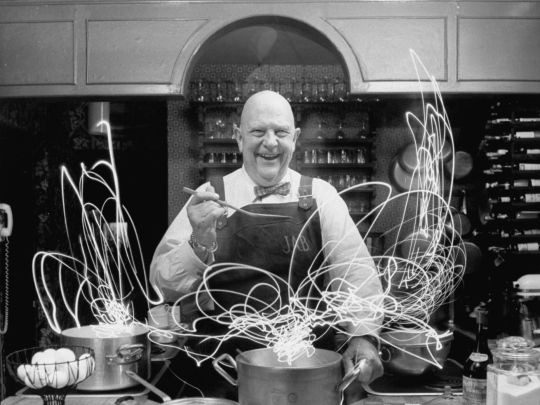

James Beard in 1972 | Photo by Arthur Schatz/Life Magazine/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

In an excerpt from The Man Who Ate Too Much, the culinary icon returns to his hometown and begins to articulate his vision for American cuisine

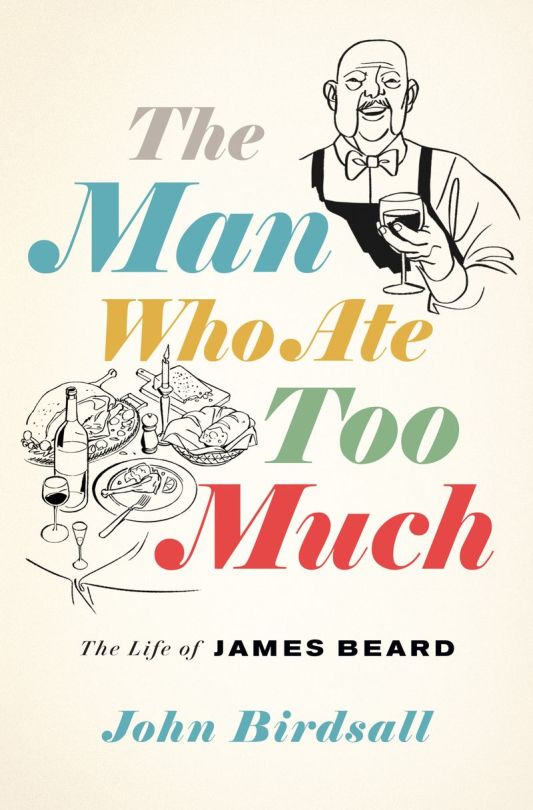

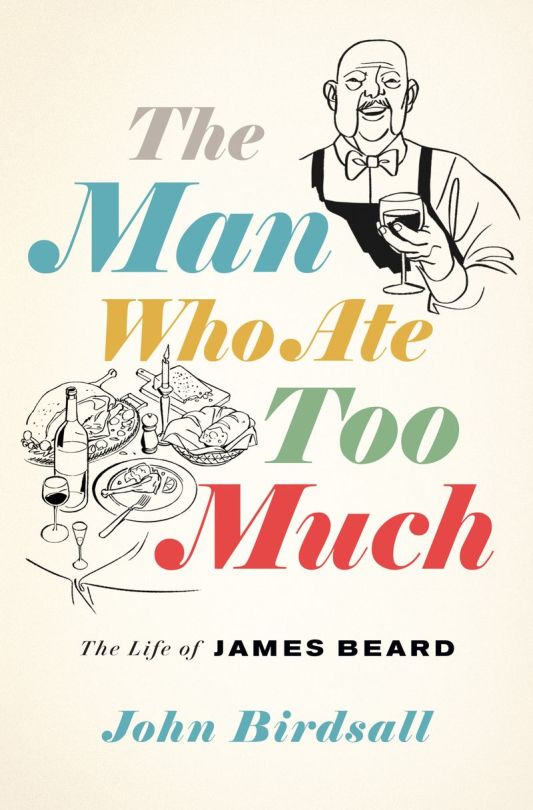

James Beard looms large in the American culinary canon. The name is now synonymous with the awards, known as the highest honors in American food, and the foundation behind them. But before his death in 1985, well before the existence of the foundation and the awards, Beard was a culinary icon. In The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard, John Birdsall tells Beard’s life story, highlighting how Beard’s queerness contributed to the concept of American cuisine he introduced to a generation of cooks.

Beard’s ascent to food-world fame wasn’t immediate. He came to food after an attempt at a life as a performer, and following a stint in catering and a gig hosting his own cooking show, Beard’s early cookbooks weren’t smash hits, his point of view not yet fully evolved. In this excerpt from The Man Who Ate Too Much, Beard embarks on a cookbook-planning trip through the American West, including his hometown of Portland, Oregon, with new friend and collaborator Helen Evans Brown and her husband, Philip. It’s there, after a whirlwind 25 days of eating (which read as especially envy inducing now), that Beard begins to define American cuisine for himself and, eventually, the country. — Monica Burton

The Man Who Ate Too Much is out on October 6; buy it at Amazon or Bookshop.

American cooks in the early 1950s were in the grip of frenzy. Shiny new grills and rotisserie gadgets, advertised like cars, loaded with the latest features, were everywhere. Outdoor equipment and appliance manufacturers rushed to market with portable backyard barbecues and plug-in kitchen roasters, meant to give Americans everywhere — even dwellers in tight city apartments — an approximate taste of grilled patio meat.

Postwar technology and American manufacturing prowess propelled infrared broilers such as the Cal Dek and the Broil-Quik. An Air Force officer, Brigadier General Harold A. Bartron, retired to Southern California in 1948 and spent his time in tactical study of a proprietary rotisserie with a self-balancing spit. He named it the Bartron Grill.

There was the Smokadero stove and Big Boy barbecue. There were enclosed vertical grills with radiant heat, hibachis from post-occupation Japan, and the Skotch Grill, a portable barbecue with a red tartan design that looked like an ice bucket.

In New York City, the high-end adventure outfitter Abercrombie and Fitch and the kitchen emporiums of big department stores did a bustling business in these new symbols of postwar meat consumption. There was even an Upper East Side shop solely dedicated to them, Smoke Cookery, Inc. on East Fiftieth Street. The only trouble was that many buyers of these shiny new grown-up toys had no clue how to cook in them.

For weeks in the spring of 1953, Helen tested electric broiler recipes, an assignment from Hildegarde Popper, food editor of House & Garden magazine, for a story called “Everyday Broils.” A few broiler and rotisserie manufacturers sent their new models to Armada Drive for Helen to try.

“The subject turns out to be a huge one,” Helen wrote Popper; she had enough material to break the story into two parts. “Jim Beard, of cook book fame, was here when my rotisserie arrived,” she told Popper, “and he was a great help to me.”

Word got around the New York editor pool. Suddenly, Helen and James seemed the ideal collaborators, storywise, to cover the new subject of grill and rotisserie cooking: West Coast and East, female and male, California suburban patio cook and Manhattan bachelor gourmet.

Meanwhile, cookbook publishing was surging. Doubleday became the first house to hire a fulltime editor, Clara Claasen, to fill its stable with cookery authors.

Schaffner took Claasen to lunch to discuss how he might be able to help. “She is very much interested in the idea of an outdoors cookbook,” he wrote to Helen afterward. “This would combine barbecue, picnic, sandwich, campfire and every other aspect of outdoor eating.” Schaffner and Claasen lunched again. James and Helen’s “cooks’ controversy” idea had run out of gas (Schaffner hated the idea anyway, especially after reading first drafts of a few Beard–Brown “letters”), so Schaffner managed to steer Claasen toward a different kind of collaboration for his two clients.

In November 1953, Helen flew to New York. She and Schaffner met with Claasen at the Doubleday offices. On a handshake, in the absence of James (who only the day before had returned from France on the Queen Elizabeth), they decided on a collaboration: an outdoor cookery book to be authored by Helen Evans Brown and James A. Beard.

Everyone was happy: Schaffner for nailing a deal for two clients at once; Claasen for bringing new talent to Doubleday. Helen was getting what she needed: a book with a major publisher. James was getting what he wanted: a reason to get even closer to Helen. Perhaps this was only the first in a long future of collaborations; they might one day even open a kitchen shop together and sell a line of their own jams and condiments. The possibilities were endless.

Claasen was eager to draw up a formal contract. All she needed from Helen and James was an outline.

Under the glowing cabin lights of a westbound red-eye flight on April 3, 1954, James found himself eerily alone. TWA’s Super Constellation was an enormous propliner with seats for nearly a hundred passengers; that night, James was one of only four. He planned to rendezvous with the Browns in San Francisco later that week, but only after he took five days on his own in the city he’d loved as a boy. From there, the three of them would embark on a weeks-long research trip in the Browns’ Coronet convertible, stopping at wineries and cheese factories throughout Northern California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Helen needed to do research for a magazine article she’d long wanted to write. She and Philip had asked James to join them five months earlier, in December 1953.

Nearly a decade after the end of the war, San Francisco was a place of resuscitated glamour, with much of the shimmer and confidence James had known in the city of his youth, when he and Elizabeth would ride the trains of the Shasta Route south.

His plane landed in drizzling rain. For his first luncheon of the trip, James chose a place of old comfort: the dim, wood-paneled Fly Trap on Sutter Street. He wore a suit of windowpane-check tweed (the jacket button straining above his stomach, his thin bow tie slightly askew), eating cold, cracked Dungeness and sautéed sand dabs. The stationery in his room at the Palace had an engraving across the top, an illustration of pioneers trudging next to oxen pulling a Conestoga wagon. Above them floated an apparition: the hotel’s neoclassical façade rising from the fog. “At the end of the trail,” it read, “stands the Palace Hotel.” James imagined himself the son of the pioneer he’d fancied his father to be. Was he now at the end of something or the beginning?

Courtesy W.W. Norton

Helen Evans Brown

He spent his days and nights eating: A luncheon of poulet sauté with Dr. A. L. Van Meter of the San Francisco branch of the Wine and Food Society (they had met on the French wine junket in 1949); dinner at the Pacific Heights home of Frank Timberlake, vice president of Guittard Chocolate; a trip to San Jose to tour the Almaden Winery and meet its owner, Louis Benoist, over a marvelous lunch of pâté, asparagus mousseline, and an omelet. James dined at the Mark Hopkins with Bess Whitcomb, his abiding mentor from the old Portland Civic Theatre days — she lived in Berkeley now and taught drama at a small college. She wore her silver hair in a short crop; her gaze was warm and deep as ever.

Helen and Philip arrived on Sunday, and on Monday the tour began with a day trip. Philip drove the Coronet across the Golden Gate Bridge north to the Napa Valley, with Helen riding shotgun and James colonizing the bench seat in back. The afternoon temperature crested in the mid-seventies and the hills were still green from winter rain. Masses of yellow wild-mustard flowers filled the vineyards. They tasted at the big four — Inglenook, Beaulieu, Charles Krug, and Louis Martini — and lunched with a winery publicist on ravioli, chicken with mushrooms, and small, sweet spring peas. James kept a detailed record of their meals in his datebook. Elena Zelayeta, the San Francisco cookbook author and radio personality, cooked them enchiladas suizas and chiffon cake.

Next day they crossed the bridge again but swung west from Highway 101 to visit the farm town of Tomales, not much more than a main street of stores and a filling station. Among the rise of green hills dotted with cows, at the farm and creamery of Louis Bononci, James had his first taste of Teleme, a washed-rind cheese with a subtly elastic texture and milky tang. Within its thin crust dusted with rice flour, James recognized the richness and polish of an old French cheese, crafted in an American setting of rusted pickups and ranchers perched on stools at diner counters. It stirred his senses and revived his love for green meadows with the cool, damp feel of Pacific fog lurking somewhere off the coast.

Philip drove west to the shore of fingerlike Tomales Bay, where they lunched on abalone and a smorgasbord that included the local Jack cheese and even more Teleme.

The car had become a mad ark of food.

The road stretched north along the coast: to Langlois, Oregon, with its green, tree-flocked hills converging in a shallow valley, where they stopped at Hans Hansen’s experimental Star Ranch. Born in Denmark, Hansen spent decades making Cheddar. In 1939, with scientists at Iowa State University and Oregon State College, Hansen had begun experimenting with what would be known as Langlois Blue Vein Cheese, a homogenized cows’-milk blue inoculated with Roquefort mold spores. (Production would eventually move to Iowa, where the cheese would be known as Maytag Blue.)

They hit Reedsport, Coquille, Coos Bay, Newport, Cloverdale, Bandon, and Tillamook. They stopped at cheese factories, candy shops, butchers’ counters, produce stands, and markets. Already stuffed with suitcases, the Coronet’s trunk became jammed with wine bottles and jars of honey and preserves; packets of sausage, dried fruit, nuts, and candy. The backseat around James filled up with bottles that rolled and clinked together on turns, with apples, tangerines, filberts, pears, and butcher-paper packets of sliced cured meat, smoked oysters, and hunks of Cheddar. The car had become a mad ark of food. James hauled anything regional and precious on board, as if later it would all prove to have been a myth if he didn’t carry some away as proof that it existed.

In Tualatin, south of Portland, they dropped in on James’s old friends from theater days, Mabelle and Ralph Jeffcott. To a crowd that included Mary Hamblet and her ailing mother, Grammie, Mabelle served baked shad and jellied salad, apple crisp, and the homemade graham bread — molasses-sweet and impossibly light — that was famous among her friends.

They lunched on fried razor clams and coleslaw at the Crab Broiler in Astoria and had martinis, kippered tuna, salmon cheeks, and Indian pudding at the Seaside cottage of James’s beloved friend Harvey Welch.

In Gearhart, James trudged out to Strawberry Knoll, walked across the dunes and onto the beach. He regarded Tillamook Head, just as he did as a boy at the start of summers. He felt a weird convergence of past and present: the sting of sand whipping his face and the smell of charred driftwood lingering in the rock-circled dugout pits of ancient cookouts.

For James, the Northwest displayed a delightfully slouchy elegance he’d almost forgotten about in New York. It had taste without snobbery. At the Pancake House in Portland, they brunched on Swedish pancakes with glasses of buttermilk and French 75 cocktails — the sort of high–low mix he had aimed for at Lucky Pierre. Why did Easterners have so much trouble grasping the idea?

Before a meal of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, they sipped a simple pheasant broth that, dolled up with half a dozen gaudy garnishes and called Consommé Louis-Philippe, would have been the jewel of Jack and Charlie’s “21” in New York. Food here had honesty. It declared what it was. Like James, it was anti-“gourmet.” Its purity was the ultimate elegance.

Thus far, James had fumbled at articulating a true American cooking. He’d taken rustic French dishes, called them by English names, and substituted American ingredients. There was something crude about such an approach. This trip had showed him American food made on French models — Gamay grapes and Roquefort spores and cheeses modeled on Camembert and Emmenthaler that tasted wonderful and were reaching for unique expressions, not just impersonating European originals. It had given James a clearer vision of American food taking root in the places it grew.

As a boy, he had glimpsed this with Chinese cooking, how a relative of the Kan family, a rural missionary, adapted her cooking to the ingredients at hand in the Oregon countryside. How her Chinese dishes took root there, blossomed into something new; how they became American.

They trekked to Seattle, where the Browns went to a hotel and James stayed with John Conway, his theater-director friend from the Carnegie Institute days. John’s wife, Dorothy, was a photographer. She shot formal portraits of James and Helen in the Conways’ kitchen — maybe Doubleday would use one as the author photo for the outdoor cookbook. They took an aerial tour of oyster beds and wandered Pike’s Place Market.

Philip then steered the Coronet eastward across Washington, through the town of Cashmere in the foothills of the Cascades, where they stopped at a diner for cube steak, cottage cheese, and pie that James noted as “wonderful” in his datebook. In Idaho, at a place called Templin’s Grill near Coeur d’Alene, they found excellent steak and hash browns. There was a Basque place along the way that made jellied beef sausage, and a diner in Idaho Falls with “fabulous” fried chicken and, as James scribbled in his daybook, “biscuits light as a feather.” The fried hearts and giblets were so delicious they bought a five-pound sack to stuff in the hotel fridge and eat in the car next day for lunch.

“Drinks, Steaks, Drinks!”

The squat, industrial-looking Star Valley Swiss Cheese Factory in Thayne, Wyoming, with a backdrop of snow on the Wellsville Mountains, produced what James thought was the best Emmenthaler-style cheese he’d tasted outside of France, but this was American cheese. They had delicious planked steak and rhubarb tart in Salt Lake City, but bad fried chicken and awful pie in Winnemucca, Nevada, was the beginning of a sad coda to their journey.

Soon they were in Virginia City, home of Lucius Beebe — brilliant, bitchy, rich, alcoholic Lucius Beebe, dear friend to Jeanne Owen and the Browns and dismissive of James from the minute they met in New York City fifteen years back.

Lucius enjoyed the life of a magnifico in the nabob splendor of the Comstock Lode, among the graceful wooden neo-Renaissance mansions, peeling in the searing Nevada sun, built by nineteenth-century silver barons. His husband in all respects, save the marriage license and church wedding, was Chuck Clegg. Chuck was quarterback-handsome and courtly, in contrast to bloated, prickly Lucius. Helen and Philip were fond of them. They wanted to linger for a few days, which turned into four days of heavy drinking and blasting wit, much of it at James’s expense.

“Drinks, Steaks, Drinks!” James wrote in his daybook. He disliked Virginia City, with its steep hills one couldn’t climb without wheezing. One day, they all had a picnic on the scrubby flank of a hill, under a brutal sun. Chuck and Lucius brought a Victorian hamper filled with fine china plates, Austrian crystal, silver, and antique damask napkins. They ate cold boned leg of lamb and beans cooked with port. They lingered so long, over so many bottles of Champagne, that James’s head became badly sunburned. Back at the motel, Philip, drunk, tried splashing James’s head with gin, hoping it would bring cooling relief. Everyone cackled at his plight.

Finally, twenty-five days after they set out from San Francisco, Philip steered the Coronet home to Pasadena.

“The trip is one of the most happy and valuable memories of my life,” he wrote to Schaffner from Pasadena. “I garnered a great deal of material, had a most nostalgic time in parts of the west most familiar to me and saw much I had never seen before. It was splendid, gastronomically speaking, to be able to see that there is hope in American cooking.”

The best and most interesting food in America was inseparable from the landscapes that produced it. It was all right there, in country diners and small-town grocers’ shops; in roadside dinner houses and bakeries. All you needed to do was look.

From The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall. Copyright © 2020 by John Birdsall. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3jsBSno https://ift.tt/34lwOuu

James Beard in 1972 | Photo by Arthur Schatz/Life Magazine/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

In an excerpt from The Man Who Ate Too Much, the culinary icon returns to his hometown and begins to articulate his vision for American cuisine

James Beard looms large in the American culinary canon. The name is now synonymous with the awards, known as the highest honors in American food, and the foundation behind them. But before his death in 1985, well before the existence of the foundation and the awards, Beard was a culinary icon. In The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard, John Birdsall tells Beard’s life story, highlighting how Beard’s queerness contributed to the concept of American cuisine he introduced to a generation of cooks.

Beard’s ascent to food-world fame wasn’t immediate. He came to food after an attempt at a life as a performer, and following a stint in catering and a gig hosting his own cooking show, Beard’s early cookbooks weren’t smash hits, his point of view not yet fully evolved. In this excerpt from The Man Who Ate Too Much, Beard embarks on a cookbook-planning trip through the American West, including his hometown of Portland, Oregon, with new friend and collaborator Helen Evans Brown and her husband, Philip. It’s there, after a whirlwind 25 days of eating (which read as especially envy inducing now), that Beard begins to define American cuisine for himself and, eventually, the country. — Monica Burton

The Man Who Ate Too Much is out on October 6; buy it at Amazon or Bookshop.

American cooks in the early 1950s were in the grip of frenzy. Shiny new grills and rotisserie gadgets, advertised like cars, loaded with the latest features, were everywhere. Outdoor equipment and appliance manufacturers rushed to market with portable backyard barbecues and plug-in kitchen roasters, meant to give Americans everywhere — even dwellers in tight city apartments — an approximate taste of grilled patio meat.

Postwar technology and American manufacturing prowess propelled infrared broilers such as the Cal Dek and the Broil-Quik. An Air Force officer, Brigadier General Harold A. Bartron, retired to Southern California in 1948 and spent his time in tactical study of a proprietary rotisserie with a self-balancing spit. He named it the Bartron Grill.

There was the Smokadero stove and Big Boy barbecue. There were enclosed vertical grills with radiant heat, hibachis from post-occupation Japan, and the Skotch Grill, a portable barbecue with a red tartan design that looked like an ice bucket.

In New York City, the high-end adventure outfitter Abercrombie and Fitch and the kitchen emporiums of big department stores did a bustling business in these new symbols of postwar meat consumption. There was even an Upper East Side shop solely dedicated to them, Smoke Cookery, Inc. on East Fiftieth Street. The only trouble was that many buyers of these shiny new grown-up toys had no clue how to cook in them.

For weeks in the spring of 1953, Helen tested electric broiler recipes, an assignment from Hildegarde Popper, food editor of House & Garden magazine, for a story called “Everyday Broils.” A few broiler and rotisserie manufacturers sent their new models to Armada Drive for Helen to try.

“The subject turns out to be a huge one,” Helen wrote Popper; she had enough material to break the story into two parts. “Jim Beard, of cook book fame, was here when my rotisserie arrived,” she told Popper, “and he was a great help to me.”

Word got around the New York editor pool. Suddenly, Helen and James seemed the ideal collaborators, storywise, to cover the new subject of grill and rotisserie cooking: West Coast and East, female and male, California suburban patio cook and Manhattan bachelor gourmet.

Meanwhile, cookbook publishing was surging. Doubleday became the first house to hire a fulltime editor, Clara Claasen, to fill its stable with cookery authors.

Schaffner took Claasen to lunch to discuss how he might be able to help. “She is very much interested in the idea of an outdoors cookbook,” he wrote to Helen afterward. “This would combine barbecue, picnic, sandwich, campfire and every other aspect of outdoor eating.” Schaffner and Claasen lunched again. James and Helen’s “cooks’ controversy” idea had run out of gas (Schaffner hated the idea anyway, especially after reading first drafts of a few Beard–Brown “letters”), so Schaffner managed to steer Claasen toward a different kind of collaboration for his two clients.

In November 1953, Helen flew to New York. She and Schaffner met with Claasen at the Doubleday offices. On a handshake, in the absence of James (who only the day before had returned from France on the Queen Elizabeth), they decided on a collaboration: an outdoor cookery book to be authored by Helen Evans Brown and James A. Beard.

Everyone was happy: Schaffner for nailing a deal for two clients at once; Claasen for bringing new talent to Doubleday. Helen was getting what she needed: a book with a major publisher. James was getting what he wanted: a reason to get even closer to Helen. Perhaps this was only the first in a long future of collaborations; they might one day even open a kitchen shop together and sell a line of their own jams and condiments. The possibilities were endless.

Claasen was eager to draw up a formal contract. All she needed from Helen and James was an outline.

Under the glowing cabin lights of a westbound red-eye flight on April 3, 1954, James found himself eerily alone. TWA’s Super Constellation was an enormous propliner with seats for nearly a hundred passengers; that night, James was one of only four. He planned to rendezvous with the Browns in San Francisco later that week, but only after he took five days on his own in the city he’d loved as a boy. From there, the three of them would embark on a weeks-long research trip in the Browns’ Coronet convertible, stopping at wineries and cheese factories throughout Northern California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Helen needed to do research for a magazine article she’d long wanted to write. She and Philip had asked James to join them five months earlier, in December 1953.

Nearly a decade after the end of the war, San Francisco was a place of resuscitated glamour, with much of the shimmer and confidence James had known in the city of his youth, when he and Elizabeth would ride the trains of the Shasta Route south.

His plane landed in drizzling rain. For his first luncheon of the trip, James chose a place of old comfort: the dim, wood-paneled Fly Trap on Sutter Street. He wore a suit of windowpane-check tweed (the jacket button straining above his stomach, his thin bow tie slightly askew), eating cold, cracked Dungeness and sautéed sand dabs. The stationery in his room at the Palace had an engraving across the top, an illustration of pioneers trudging next to oxen pulling a Conestoga wagon. Above them floated an apparition: the hotel’s neoclassical façade rising from the fog. “At the end of the trail,” it read, “stands the Palace Hotel.” James imagined himself the son of the pioneer he’d fancied his father to be. Was he now at the end of something or the beginning?

Courtesy W.W. Norton

Helen Evans Brown

He spent his days and nights eating: A luncheon of poulet sauté with Dr. A. L. Van Meter of the San Francisco branch of the Wine and Food Society (they had met on the French wine junket in 1949); dinner at the Pacific Heights home of Frank Timberlake, vice president of Guittard Chocolate; a trip to San Jose to tour the Almaden Winery and meet its owner, Louis Benoist, over a marvelous lunch of pâté, asparagus mousseline, and an omelet. James dined at the Mark Hopkins with Bess Whitcomb, his abiding mentor from the old Portland Civic Theatre days — she lived in Berkeley now and taught drama at a small college. She wore her silver hair in a short crop; her gaze was warm and deep as ever.

Helen and Philip arrived on Sunday, and on Monday the tour began with a day trip. Philip drove the Coronet across the Golden Gate Bridge north to the Napa Valley, with Helen riding shotgun and James colonizing the bench seat in back. The afternoon temperature crested in the mid-seventies and the hills were still green from winter rain. Masses of yellow wild-mustard flowers filled the vineyards. They tasted at the big four — Inglenook, Beaulieu, Charles Krug, and Louis Martini — and lunched with a winery publicist on ravioli, chicken with mushrooms, and small, sweet spring peas. James kept a detailed record of their meals in his datebook. Elena Zelayeta, the San Francisco cookbook author and radio personality, cooked them enchiladas suizas and chiffon cake.

Next day they crossed the bridge again but swung west from Highway 101 to visit the farm town of Tomales, not much more than a main street of stores and a filling station. Among the rise of green hills dotted with cows, at the farm and creamery of Louis Bononci, James had his first taste of Teleme, a washed-rind cheese with a subtly elastic texture and milky tang. Within its thin crust dusted with rice flour, James recognized the richness and polish of an old French cheese, crafted in an American setting of rusted pickups and ranchers perched on stools at diner counters. It stirred his senses and revived his love for green meadows with the cool, damp feel of Pacific fog lurking somewhere off the coast.

Philip drove west to the shore of fingerlike Tomales Bay, where they lunched on abalone and a smorgasbord that included the local Jack cheese and even more Teleme.

The car had become a mad ark of food.

The road stretched north along the coast: to Langlois, Oregon, with its green, tree-flocked hills converging in a shallow valley, where they stopped at Hans Hansen’s experimental Star Ranch. Born in Denmark, Hansen spent decades making Cheddar. In 1939, with scientists at Iowa State University and Oregon State College, Hansen had begun experimenting with what would be known as Langlois Blue Vein Cheese, a homogenized cows’-milk blue inoculated with Roquefort mold spores. (Production would eventually move to Iowa, where the cheese would be known as Maytag Blue.)

They hit Reedsport, Coquille, Coos Bay, Newport, Cloverdale, Bandon, and Tillamook. They stopped at cheese factories, candy shops, butchers’ counters, produce stands, and markets. Already stuffed with suitcases, the Coronet’s trunk became jammed with wine bottles and jars of honey and preserves; packets of sausage, dried fruit, nuts, and candy. The backseat around James filled up with bottles that rolled and clinked together on turns, with apples, tangerines, filberts, pears, and butcher-paper packets of sliced cured meat, smoked oysters, and hunks of Cheddar. The car had become a mad ark of food. James hauled anything regional and precious on board, as if later it would all prove to have been a myth if he didn’t carry some away as proof that it existed.

In Tualatin, south of Portland, they dropped in on James’s old friends from theater days, Mabelle and Ralph Jeffcott. To a crowd that included Mary Hamblet and her ailing mother, Grammie, Mabelle served baked shad and jellied salad, apple crisp, and the homemade graham bread — molasses-sweet and impossibly light — that was famous among her friends.

They lunched on fried razor clams and coleslaw at the Crab Broiler in Astoria and had martinis, kippered tuna, salmon cheeks, and Indian pudding at the Seaside cottage of James’s beloved friend Harvey Welch.

In Gearhart, James trudged out to Strawberry Knoll, walked across the dunes and onto the beach. He regarded Tillamook Head, just as he did as a boy at the start of summers. He felt a weird convergence of past and present: the sting of sand whipping his face and the smell of charred driftwood lingering in the rock-circled dugout pits of ancient cookouts.

For James, the Northwest displayed a delightfully slouchy elegance he’d almost forgotten about in New York. It had taste without snobbery. At the Pancake House in Portland, they brunched on Swedish pancakes with glasses of buttermilk and French 75 cocktails — the sort of high–low mix he had aimed for at Lucky Pierre. Why did Easterners have so much trouble grasping the idea?

Before a meal of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, they sipped a simple pheasant broth that, dolled up with half a dozen gaudy garnishes and called Consommé Louis-Philippe, would have been the jewel of Jack and Charlie’s “21” in New York. Food here had honesty. It declared what it was. Like James, it was anti-“gourmet.” Its purity was the ultimate elegance.

Thus far, James had fumbled at articulating a true American cooking. He’d taken rustic French dishes, called them by English names, and substituted American ingredients. There was something crude about such an approach. This trip had showed him American food made on French models — Gamay grapes and Roquefort spores and cheeses modeled on Camembert and Emmenthaler that tasted wonderful and were reaching for unique expressions, not just impersonating European originals. It had given James a clearer vision of American food taking root in the places it grew.

As a boy, he had glimpsed this with Chinese cooking, how a relative of the Kan family, a rural missionary, adapted her cooking to the ingredients at hand in the Oregon countryside. How her Chinese dishes took root there, blossomed into something new; how they became American.

They trekked to Seattle, where the Browns went to a hotel and James stayed with John Conway, his theater-director friend from the Carnegie Institute days. John’s wife, Dorothy, was a photographer. She shot formal portraits of James and Helen in the Conways’ kitchen — maybe Doubleday would use one as the author photo for the outdoor cookbook. They took an aerial tour of oyster beds and wandered Pike’s Place Market.

Philip then steered the Coronet eastward across Washington, through the town of Cashmere in the foothills of the Cascades, where they stopped at a diner for cube steak, cottage cheese, and pie that James noted as “wonderful” in his datebook. In Idaho, at a place called Templin’s Grill near Coeur d’Alene, they found excellent steak and hash browns. There was a Basque place along the way that made jellied beef sausage, and a diner in Idaho Falls with “fabulous” fried chicken and, as James scribbled in his daybook, “biscuits light as a feather.” The fried hearts and giblets were so delicious they bought a five-pound sack to stuff in the hotel fridge and eat in the car next day for lunch.

“Drinks, Steaks, Drinks!”

The squat, industrial-looking Star Valley Swiss Cheese Factory in Thayne, Wyoming, with a backdrop of snow on the Wellsville Mountains, produced what James thought was the best Emmenthaler-style cheese he’d tasted outside of France, but this was American cheese. They had delicious planked steak and rhubarb tart in Salt Lake City, but bad fried chicken and awful pie in Winnemucca, Nevada, was the beginning of a sad coda to their journey.

Soon they were in Virginia City, home of Lucius Beebe — brilliant, bitchy, rich, alcoholic Lucius Beebe, dear friend to Jeanne Owen and the Browns and dismissive of James from the minute they met in New York City fifteen years back.

Lucius enjoyed the life of a magnifico in the nabob splendor of the Comstock Lode, among the graceful wooden neo-Renaissance mansions, peeling in the searing Nevada sun, built by nineteenth-century silver barons. His husband in all respects, save the marriage license and church wedding, was Chuck Clegg. Chuck was quarterback-handsome and courtly, in contrast to bloated, prickly Lucius. Helen and Philip were fond of them. They wanted to linger for a few days, which turned into four days of heavy drinking and blasting wit, much of it at James’s expense.

“Drinks, Steaks, Drinks!” James wrote in his daybook. He disliked Virginia City, with its steep hills one couldn’t climb without wheezing. One day, they all had a picnic on the scrubby flank of a hill, under a brutal sun. Chuck and Lucius brought a Victorian hamper filled with fine china plates, Austrian crystal, silver, and antique damask napkins. They ate cold boned leg of lamb and beans cooked with port. They lingered so long, over so many bottles of Champagne, that James’s head became badly sunburned. Back at the motel, Philip, drunk, tried splashing James’s head with gin, hoping it would bring cooling relief. Everyone cackled at his plight.

Finally, twenty-five days after they set out from San Francisco, Philip steered the Coronet home to Pasadena.

“The trip is one of the most happy and valuable memories of my life,” he wrote to Schaffner from Pasadena. “I garnered a great deal of material, had a most nostalgic time in parts of the west most familiar to me and saw much I had never seen before. It was splendid, gastronomically speaking, to be able to see that there is hope in American cooking.”

The best and most interesting food in America was inseparable from the landscapes that produced it. It was all right there, in country diners and small-town grocers’ shops; in roadside dinner houses and bakeries. All you needed to do was look.

From The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall. Copyright © 2020 by John Birdsall. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3jsBSno via Blogger https://ift.tt/3jobHy8

0 notes

Text

panchagavya deepam online

"Discover the power of Panchagavya Deepam online, a sacred and natural cow dung-based lamp. Experience its divine energy and purifying effects. Shop now for authentic Panchagavya Deepam products at competitive prices. Illuminate your home with spiritual light. Order today."https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes

Text

Holy Cow Dung Cakes for Pooja Available on Amazon

In Hindu culture, rituals and ceremonies hold immense significance, with each practice deeply rooted in tradition and spirituality. One such tradition involves the use of cow dung cakes for pooja (worship) purposes. Cow dung, considered sacred in Hinduism, is believed to have purifying properties and is commonly used in various religious rituals.

Nowadays, with the advancement of technology and the widespread availability of goods online, even sacred items like cow dung cakes are easily accessible. Thanks to platforms like Amazon, individuals seeking to perform pooja rituals can conveniently purchase these traditional items from the comfort of their homes.

Understanding the Significance: In Hinduism, the cow is revered as a symbol of divine and maternal qualities. Cow dung is believed to be pure and spiritually cleansing. It is used in various religious ceremonies, including yagnas (fire rituals), homas (rituals involving fire), and daily household poojas.

The Process of Making Cow Dung Cakes: The process of making cow dung cakes involves collecting fresh cow dung, mixing it with water, and shaping it into round cakes. These cakes are then dried in the sun until they harden. Traditionally, women in rural households play a significant role in making these cakes, as it is considered a sacred and essential task.

Availability on Amazon: With the increasing demand for traditional religious items, including cow dung cakes, sellers on Amazon have started offering these products to a wider audience. A simple search on the platform reveals various sellers providing freshly made cow dung cakes, ensuring customers receive authentic and high-quality products for their pooja rituals.

Benefits of Purchasing Cow Dung Cakes on Amazon:

Convenience: Purchasing cow dung cakes on Amazon saves time and effort, especially for individuals living in urban areas or those with busy schedules.

Quality Assurance: Amazon sellers often provide detailed descriptions and customer reviews, allowing buyers to make informed decisions and choose reputable sellers offering genuine products.

Wide Selection: Amazon offers a wide range of cow dung cake products, including different sizes and quantities, catering to the diverse needs of customers.

Fast Delivery: With Amazon's efficient delivery system, customers can expect timely delivery of their cow dung cakes, ensuring they have everything they need for their pooja rituals.

0 notes

Text

Cow Dung Cake Price Per Kg In Vizag

Cow dung cake price per kg can vary based on location and demand These cakes, traditionally used as fuel and fertilizer, are eco-friendly and affordable, making them a sustainable choice for rural areas and organic farming practices. https://daasoham.com/

0 notes

Text

Cow-dung cakes up for sale in US; social media goes into a tizzy

Cow-dung cakes up for sale in US; social media goes into a tizzy

The Hush Post | 6:20 pm | One-minute read |

A picture showing cow-dung cakes made in India displayed for sale at an American store has gone viral on social media. The makers have mentioned on the label that the cakes are ‘non-eatable’ so that the local customers don’t take them to be edible.

The packet contains 10 cow-dung cakes and it has been clearly mentioned that they are to be used only for…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The California Kitchen: Crab Cake Untamed

The California Kitchen: Crab Cake Untamed

In today’s California Kitchen, learn to cook amazing Crab Cake Untamed with The Untamed Chef, Albert J. Hernandez. Here is what you will need:

1 LB Dungeness Crab Claw, 2 C Panko, 3 Eggs, TT S+P, TT Lemon Pepper 1 C Mayonnaise

For this and many more of these recipes visit: www.ajhtheuntamedchef.com

Watch Albert’s Cooking Show: www.foodytv.comor stream it on Roku, Amazon Fire, Google TV…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

5 Basic Actions To A Supper To Nourish Your Gut

CAPITAL Pulling on their diving gear and flippers at a swimming pool in Brussels, Nicolas Mouchart and also his spouse Florence are certainly not just going scuba diving - they are actually pursuing supper. Fruits and pumpkins with faces that are actually ugly or scary are likewise located embroidered in little ones Halloween polo shirts as a more classic design. I live where our company possess Dungeness Crab ... however have actually possessed Blue Crab birthday cakes and also adore all of them! She would make the meatballs small and will churn all of them all day long in the sauce up until my father, sibling and I gorged them at supper. For those interested in wearing outerwear to as well as from the celebration, a matching heavyweight coat in charcoal, black, or dark blue in the Chesterfield style are actually one of the most satisfactory. Each products are actually craveable and also stand for the top quality, market value as well as range that are core to our Red Robin food selection. Our entire week's dinner menu is actually prepared in such a method that there is actually fat chance from repeating a solitary food. X-mas lunch time (in Australia, dinner describes the evening dish) 23 in Australia is actually based upon the traditional English versions. There is actually a total assortment from intermediate bodied as well as total bodied wine in which the other possesses the greatest quantity from tannin giving this a darker red colour. If you are actually searching for an enjoyable as well as tough playset, reviewed the reviews from delighted clients and also think about buying a Kidkraft Reddish Vintage Play Home kitchen They can be gotten online coming from Amazon and shipped right to your door. Prior to I switch the call over to Denny, I wish to repeat our confidence in the durability of our long-lasting game plan Red Squared and our laser pay attention to profits development, expenditure monitoring and dependable release from resources. The fantastic trait using this sort of dinner is that every person feels fantastic that they have actually helped in a deserving source and also you'll have done it in such an exciting way! Due to the fact that she has eliminated so a lot as well as has such a pleasant sense, I would certainly gym-sport-fit.info desire to have dinner with Latoya Jackson. Hosted through Ruler Elizabeth II, the lush function took place at Buckingham Royal residence and also that was absolutely nothing short of royal The past Kate Middleton stunned in a cap-sleeved red dress supposedly custom made by Jenny Packham and plenty of gems, featuring just what seems like the very same tiara she wore to a smooth event in 2013.

0 notes

Text

cow dung price in amazon

Looking for affordable cow dung. Check out our wide range of high-quality cow dung products on Amazon. Get the best prices and fast delivery. Shop now.https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes

Text

desi cow dung cake

Looking for affordable dung cake prices. Find the best deals on high-quality dung cakes for fuel and fertilizer purposes. Our range offers competitive prices, eco-friendly solutions, and efficient burning properties. Don't miss out on the best dung cake prices available. Shop now.https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes

Text

Panchagavya Deepam Near Me

Panchagavya is a blend of five key ingredients obtained from cows: milk, curd, ghee (clarified butter), urine, and dung. It holds significant cultural and religious value in Hinduism and is believed to possess purifying and healing properties..https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes

Text

cow dung price in amazon

Looking for high-quality cow dung cakes near you. Discover reliable suppliers offering premium cow dung cakes for various purposes. Enhance your gardening, spiritual, or cultural practices with our eco-friendly and organic cow dung cakes. Find the nearest location and buy now.https://daasoham.com/

#gobar ka diya#cow dung cake for pooja#cow dung cake for plants#dung cake amazon#holy cow dung cake#gobar cake price#cow dung cake price amazon#use of cow dung cake#agnihotra cow dung

0 notes