#duchess of elchingen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

ab. 1812 François Gérard - Aglaée Louise (called Eglée) Auguié Ney, Duchess of Elchingen, Princess of Moscow

(Albany Institute of History and Art)

592 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Aglaée Louise Auguié Ney, Duchess of Elchingen was so gorgeous and stylish, she could pass as a reincarnation of Cleopatra. The portrait of her in the red dress is particuarly striking” - Submitted by Anonymous

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

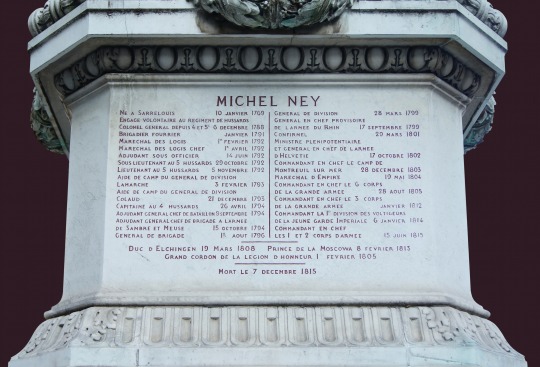

Marshal Ney: Street Names, Statues... Not Bad for a Traitor

Outside the Chamber of Peers, the outcome of Ney’s trial did not meet with universal approval, far from it. I will return to more immediate reactions, but as time went by more and more public manifestations of homage became visible in various forms. This is my translation of what the Senat’s file on Ney has to say about this. The original text is to be found here:

https://www.senat.fr/evenement/archives/D26/execution_et_rehabilitations/ses_rehabilitations.html

In Paris, a boulevard has been named after Marshal Ney since 1864. The statue in the Rue de Rivoli, by Coutalpas, opposite number 172 on the north façade of the Louvre, dates from the same period.

This statue can be seen on this site: http://www.paristoric.com/index.php/paris-d-hier/statues/statues-du-louvre/2116-les-statues-du-louvre-la-statue-de-michel-ney

Ney's name also appears on the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile in Paris, East pillar, thirteenth column, below Moreau's name and between those of Gouvion-Saint-Cyr and Macdonald, among the six hundred and sixty names of personalities who served during the French Revolution and the Empire.

His grave in the Père-Lachaise cemetery was moved in 1903 to the twenty-ninth division, at the crossroads of the Masséna and Acacias roads. A new funerary monument replaced the old, very plain grave.

In the Luxembourg Palace, a commemorative plaque was affixed to the door of the room that served as Marshal Ney's cell during his trial in the Chamber of Peers

This final paragraph is interesting because it show how Ney’s descendants intermarried with other families of the Imperial era. The Duc de Broglie is the only member of the Chamber of Peers who dared to vote against conviction:

The ceremony took place on 20 June 1935 in the presence of Jules Jeanneney, President of the Senate, several senators and members of the Ney family represented by Michel Ney, Duke of Elchingen, great-great-grandson of the Marshal; his wife, the Duchess of Elchingen; the Princess of the Moskowa, born Princess Bonaparte; Princess Murat, born Ney d'Elchingen; her son, Prince Joachim Murat, great-grandson of the King of Naples. The Duke Maurice de Broglie, member of the French Academy and great-grandson of the peer of France who had voted against the conviction of the Marshal, and his wife the Duchess de Broglie were also present.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aglaé Louise (called Eglée) Auguié Ney, Duchess of Elchingen, Princess of Moscow (1812). François-Pascal-Simon Gérard (French, 1770-1837). Oil on canvas. Albany Institute of History & Art.

Marshall Ney's wife Eglée Auguie wears a bandeau across her forehead like a ferronnière and another higher between her head and her bun in this Gérard portrait.

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michel Ney & Aglaé Auguié (1/2)

“Michel Ney fut sans doute de tous les maréchaux de l’Empire celui dont le mariage fut le plus directement provoqué par le clan Bonaparte-Beauharnais. Il n’était pas trop chaud pour le régime du pouvoir personnel; il s’agissait de l’arracher à ses rêveries républicaines par quelque brillant établissement qui le rehaussât à ses propres yeux. Sous le Consulat, Ney était fort et grand gaillard, rouge de teint et de poil, prompt à la colère comme au plaisir, à qui l’on connaissait deux passions: la guerre et la flûte. Les femmes ne venaient qu’après, sans pourtant qu’il les dédaignât. Il avait notamment une liaison assez voyante avec une aventurière spirituelle et jolie qui avait déjà été, entre autres, la maîtresse de Marescot et de Moreau. Cette idylle sans innocence battait son plein au moment où s’échafaudait, entre Hortense, Joséphine et Napoléon, le projet qui devait décider du bonheur de Ney.

On ne se moquait assurément pas du jeune général en lui offrant la main de Mlle Auguié, une des plus chères créations de Mme Campan, dont elle était la nièce. Bien que simple bourgeoise et fille d’un receveur des finances, cette jeune personne appartenait au monde de l’Ancien Régime plutôt qu’à la Société républicaine. Sa mère, ancienne demoiselle de la chambre de Marie-Antoinette, avait montré un grand dévouement à la personne de la reine pendant la Révolution, et, traquée pour ce fait même, s’était tuée en se jetant par une fenêtre quelques jours avant le 9 Thermidor.

Une première entrevue ne donna pas de résultat définitif. Aglaé Auguié, qu’on appelait toujours du joli diminutif d’Eglé, fut plus impressionnée par la réputation militaire de Ney que par son physique un peu rude. De son côté, le général ne montra pas d’empressement excessif. Mais Joséphine veillait, et le mariage fut conclu après quelques hésitations de part et d’autre. La cérémonie eut lieu dans la propriété de M. Auguié, à Grignon, le 5 août 1802. La jeune femme était grande, agréablement tournée quoique un peu maigre. Son visage était éclairé par deux magnifiques yeux noirs qui lui valurent plus tard d’inspirer une passion assez comique à un ambassadeur du shah de Perse. Elle était la meilleure amie d’Hortense de Beauharnais qui l’a dépeinte “remplie de bonté, de sensibilité, et d’agréments”. Les ménages Ney et Louis Bonaparte restèrent très liés pendant longtemps. On se réunissait plusieurs fois par semaine pour prendre le thé et suivre les leçons de dessin d’Isabey. Dans cet art, Eglé ne brillait guère. D’ailleurs, elle n’avait jamais eu beaucoup de dispositions pour l’étude, et elle donnait parfois l’impression de n’être pas aussi parfaitement rompue aux usages du monde que les autres élèves de sa tante.

Attachée à l’Impératrice Joséphine en qualité de dame du Palais, la maréchale Ney montra une sincère affection à sa maîtresse dont une calomnie d’antichambre faillit lui faire perdre la confiance. Tout au début de l’Empire, on lui prêta une liaison avec Napoléon qui avait paru quelquefois empressé auprès d’elle. Joséphine accorda de l’importance à ces bruits et se plaignit à sa fille de la perfidie de la maréchale. Une franche explication établit que celle-ci n’éprouvait à l’égard de l’Empereur qu’un sentiment de crainte, et l’incident fut clos. Lors du divorce impérial, la duchesse d’Elchingen voulut suivre dans sa retraite l’Impératrice répudiée et se heurta à l’opposition violente de son mari, qui lui enjoignit par écrit de donner sa démission. Elle obéit à contre-coeur et fut nommée peu après dame du Palais de la nouvelle souveraine. “

Louis Chardigny, Les Maréchaux de Napoléon, Bibliothèque Napoléonienne, P. 212-214.

“Of all the marshals of the Empire Michel Ney was undoubtedly the one whose marriage was most directly provoked by the Bonaparte-Beauharnais clan. He was not keen on a personal power regime; it was about dragging him out of his Republican daydreams with some brilliant set up which would raise him in his own eyes. Under the Consulate, Ney was a strong, tall fellow, red of complexion and hair, quick to anger and pleasure, who had two known passions: war and the flute. Women came only after, yet he did not disdain them. In particular, he had a rather conspicuous affair with a pretty, witty adventurous woman who had already been, among others, the mistress of Marescot and Moreau. This innocence-free idyll was in full swing as Hortense, Josephine, and Napoleon were putting together the project that was to decide Ney’s happiness.

The young general certainly wasn't made fun of when he was offered the hand of Miss Auguié, one of Mme Campan's dearest creations, and her niece. Although a simple bourgeois and daughter of a tax collector, this young person belonged to the world of the Old Regime rather than to the Republican Society. Her mother, a former lady of Marie-Antoinette's, had shown great devotion to the person of the queen during the Revolution, and, hunted down for this very fact, had killed herself by throwing herself out of a window a few days before the 9 Thermidor.

A first meeting did not give a conclusive result. Aglaé Auguié, who was always called by the pretty nickname "Eglé", was more impressed by Ney's military reputation than by his rough looks. For his part, the general did not show excessive eagerness. But Josephine was watching, and the marriage was concluded after some hesitation on both sides. The ceremony took place in the property of Mr. Auguié, in Grignon, on August 5, 1802. The young woman was tall, good looking although a little thin. His face was lit by two beautiful black eyes which later earned her a somewhat comical passion from an ambassador of the Shah of Persia. She was the best friend of Hortense de Beauharnais who portrayed her "full of kindness, sensitivity, and agreeableness". The Ney and Louis Bonaparte households remained closely linked for a long time. They used to meet several times a week for tea and for Isabey's drawing lessons. In this art, Eglé hardly shone. Besides, she had never had much of a disposition for study, and she sometimes gave the impression of not being as well versed in the customs of the world as her aunt's other students.

Attached to the Empress Joséphine as Dame du Palais, the Maréchale Ney showed sincere affection to her mistress whose trust she almost lost because of antechamber slander. At the very beginning of the Empire, some people ascribed to her an affair with Napoleon, who had sometimes seemed eager around her. Josephine attached importance to these rumors and complained to her daughter of the Maréchale's treachery. A frank explanation established that all the lady felt towards the Emperor was some feeling of fear, and the incident was over. During the imperial divorce, the Duchess of Elchingen wanted to follow the repudiated Empress into her retirement and met with violent opposition from her husband, who ordered her in writing to resign. She reluctantly obeyed and was named shortly after Dame du Palais of the new sovereign."

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Bravest of the Brave”: Marshal Ney, the soldier’s soldier.

Michel Ney, duke d’Elchingen, (10 Jan 1769 - 7 Dec 1815), one of the best known of Napoleon’s marshals (from 1804), who pledged his allegiance to the restored Bourbon monarchy when Napoleon abdicated in 1814. Upon Napoleon’s return in 1815, Ney rejoined him and commanded the Old Guard at the Battle of Waterloo. Under the monarchy, again restored, he was charged with treason, for which he was condemned and shot by a firing squad.

His execution like his soldiering life was the stuff of legends.

Beginnings

Ney was the son of a barrel cooper and blacksmith. Apprenticed to a local lawyer, he ran away in 1788 to join a hussar regiment. His opportunity came with the revolutionary wars, in which he fought from the early engagements at Valmy and Jemappes in 1792 to the final battle of the First Republic at Hohenlinden in 1800.

Ney’s legendary bravery was especially seen at Mannheim when a cannonball killed his horse and wounded his leg, and then when Ney stood up he was hit by a bullet to the chest which threw him to the ground. Luckily for him, the bullet was spent and did not pierce him, instead only giving him a bad bruise.

The early campaigns revealed two contrasting features of Ney’s character: his great courage under fire and his strong aversion to promotion. Willing to hurl himself into battle at critical moments to inspire his troops by his personal example, he was unwilling to accept higher rank, and when his name was put forward he protested to his military and political superiors. In every instance he was overruled: it was as general of a division that he fought in Victor Moreau’s Army of the Rhine at Hohenlinden.

He soon caught Napoleon’s eye and made rapid progress up the ranks. He didn’t disappoint. The further up the ranks he went the further into danger threw himself into. The men loved him and followed him anywhere.

On May 19, 1804, the day after Napoleon had had himself proclaimed hereditary emperor of the French, he revived the ancient military rank of marshal, and 14 generals, including Ney, were gazetted marshals of the empire.

The Russian campaign of 1812 cemented his legend. On the morning after the somewhat inconclusive battle at Borodino, Napoleon made him prince de la Moskowa. On the retreat from Moscow, Ney was in command of the rear guard, a position in which he was exposed to Russian artillery fire and to numerous Cossack attacks. He rose to heights of courage, resourcefulness, and inspired improvisation that seemed miraculous to the men he led. “He is the bravest of the brave,” said Napoleon when Ney, for weeks given up as lost, joined the main body of the frozen and shrunken Grand Army.

The fall of Napoleon and the rise of the Bourbons

But after 1813 and the with the Winter disaster in Russia, Napoleon suffered a series of setbacks that eventually pushed him back to France and to the brink of defeat.

Napoleon concentrated his remaining forces at Fontainebleau to fight the allies in Paris, but Ney, speaking for himself and other marshals, told him that the army would not march. “The army will obey me,” said Napoleon. “Sire,” replied the Bravest of the Brave, “the army will obey its generals.” Napoleon was forced to abdicate. Ney retained his rank and titles and took an oath of fidelity to the Bourbon dynasty.

With the Bourbons returned to power in France in 1814, Marshal Ney rallied to them in the hopes of a peaceful and stable France. In response, he was made a Knight of Saint-Louis and Peer of France and he was placed in charge of the cavalry. However, despite these rewards he could only watch as the government grew inefficient and old privileges granted to the nobility were restored, going against the very changes that had allowed him to rise so high.

Furthermore, since he was the first Duke of Elchingen and first Prince of the Moskowa, he and his wife were frequently snubbed by the returned nobility with famous ancestors.

One day he returned home to find his wife in tears over more ill treatment received from the Duchess of Angoulême. Enraged, Ney charged to the Tuileries where he burst in, politely and quickly paid his respects to the king, and then verbally berated the Duchess, beginning with, "I and others were fighting for France while you sat sipping tea in English gardens," and ending with, "You don't seem to know what the name Ney means, but one of these days I'll show you!"

The 100 Days and the Battle of Waterloo

When in 1815 Napoleon escaped from Elba and began his triumphant march back to Paris, Ney was horrified by the prospect of civil war. Despite his dislike of the Bourbons, he told the king he would bring Napoleon back to Paris in an iron cage. As Ney led his troops in a march to intercept Napoleon, his doubts began to grow. The people of France and the army all seemed to be cheering for Napoleon, and no one had fired a shot to stop Napoleon. During every step of Napoleon's progress, more and more had joined his side.

If Ney ordered his men to fight Napoleon and his men, Ney might be the cause of civil war, presuming that his men would even follow his orders and shoot at their former emperor. After receiving a message from Napoleon, Ney decided that he could not fight the tide and told his men that the legitimate dynasty of France as chosen by the people was Napoleon. His men began cheering, and he sent off messages stating his intent to rejoin Napoleon.

Despite Ney’s conduct, Napoleon wanted his ‘bravest of the brave’ by his side once again. Ney decided to take up the offer and assumed command of the left wing of the Army of the North. Almost immediately he was thrust into action, fighting the British at Quatre-Bras on June 16th. Two days later he fought at the Battle of Waterloo, leading from the front and having four horses killed underneath him over the course of the battle. When the French began to break and be overrun by the combined Prussian and British forces, Ney said, "Come and see how a Marshal of France dies!"4

Ney escaped from Waterloo and returned to Paris where the Minister of Police Fouché gave him passports which he did not use. After Napoleon's second abdication, Marshal Davout took command of the army and refused to surrender until a treaty was signed that granted amnesty to those who had rejoined Napoleon. Ney went into hiding at a friend's chateau, but he was soon spotted and arrested. Even the king was upset that he had not fled the country, hoping to avoid a trial that could expose the internal divisions of the people. After giving his promise to not flee, Ney was escorted back to Paris without being bound. On the way General Exelmans came to his rescue, but Ney refused to go against his word to his captors, and he continued back to Paris.

Trial and execution

Initially Ney was to be tried by a military court run by Marshal Jourdan, however his defense team argued that this court could not try him, and instead his case should be tried in the Chamber of Peers. His defense team won in this regard when the court declared itself incompetent, though that may have been due to the military court not wanting to convict him but also not wanting to defy the Bourbons by acquitting him. Next Ney would be tried by a group populated by Royalists and without the same sense of honor as his military colleagues.

During the trial in the Chamber of Peers, Ney's lawyers brought up how the trial was in direct violation of the treaty Davout had negotiated, and secretly in response a new law was then passed forbidding mentioning that treaty in court. With such an act, it became clear to everyone that the trial was a witch hunt. As a last attempt, his lawyers argued that since Ney's hometown of Saarelouis was ceded to Prussia, he could not be tried as a Frenchman, but Ney vehemently denounced this tactic and demanded to be tried as a Frenchman. Some of Ney's supporters appealed to the British for assistance, but they refused, claiming that they could not meddle in France's internal affairs despite spending the past twenty five years trying to change France's government.

On December 6th, Ney was convicted by the Chamber of Peers and the Peers also voted on his sentence, with the majority voting for death by firing squad. The execution was to be carried out the next day. When news of Ney's sentence reached the public, a mob began to form where the execution was to take place, and a new place of execution was quickly arranged at a different location.

Ney faced his execution by firing squad in Paris near the Luxembourg Garden. He refused to wear a blindfold and was allowed the right to give the order to fire, reportedly saying:

“Soldiers, when I give the command to fire, fire straight at my heart. Wait for the order. It will be my last to you. I protest against my condemnation. I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her ... Soldiers, fire!”

Marshal Michel Ney was a soldier’s soldier.

Ney was wholly without political ambition or judgment. He was at his greatest in the campaigns for France’s natural frontiers at the beginning and end of his career, but out of his depth in Napoleon’s intricate strategy for the domination of Europe. He showed little interest in external distinctions or social success. The dignity with which he met his death effaced the memory of his political vagaries and made him, in an epic age, the most heroic figure of his time.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE GARDEN

Aglae Ney, later Duchess de’Elchingen and Princess de la Moskowa, née Auguié de Lascans (1782-1854)

#the garden#aglae ney#aglae auguie#duchess of elchingen#princess de la moskowa#france#french aristocracy#french nobility#royal#royals#royalty#royaltyedit

9 notes

·

View notes