#draconinae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Guys. Vil did Ortho's make up with a regular brush and not an airbrush. I'm light headed thinking about Vil being affectionate with a first year who actually wants to reciprocate it.

Ortho wants to be acknowledged as a real boy and Vil gives that to him every single time. He would caress Ortho's skin because of how unnaturally soft it is. When Ortho looks a little peeved at the thought that a self learning automaton can't have soft skin, but Vil clarifies that he meant "for a 16 year old boy. He has soft skin for a 16 year old boy."

When Ortho misses film club meetings, idia tells Vil that he has a bug. Vil's not entirely clueless, he brainstorms with Epel things that he might enjoy while he feels better. They settle on a holographic soup that Ortho delights in downloading.

When he returns, Vil feels around his neck for any remnants of a fever or swelling, his so called "lymph nodes." Ortho finds it all pleasant, even if it is a weird sensation. Despite being built with touch sensors and complex coding to distinguish between touches, most people aren't aware of them. They try not to touch him.

Vil would also fall in love with Ortho's eccentricities. He loves that Ortho is outspoken with his own opinions, especially on the films they create. Vil would tell him that his little synthetic laugh is contagious, and makes him laugh too.

The problem with being created so human, with his own scarily similar humanity, is that he feels grief without the justification. Idia's bad moods can ruin his too, a lack of touch can make him lonely. Being excluded feels just like that.

The small ways that NRC boys, the 3rd years in particular, include Ortho leave me sobbing on the floor. Malleus referring to Ortho as Littler Shroud, using a name that he reserves for living things to address Ortho. Floyd and Jade strong arming Idia into making Ortho feet so he can wear shoes (LOL?) kjasdas post cancelled I can't stop laughing

#vil schoenheit#ortho shroud#littler shroud#twst#twisted wonderland#malleus draconina#floyd leech#jade leech#my babies#idia shroud#twst imagines#hof#m#txt

581 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I...I think I like it here, at this party”

Mademoiselle Gwen Schnee has arrived at the Glimmering Soirée!

Voice lines and Fullbody are under the cut!

Summon: “I do hope I’m dressed well enough for this...”

Groovy: “Allow me to be of service tonight!”

Set Home: “This hoop skirt makes some of movements odd. I’m sure I’ll get used to it.”

Home Idle 1: “I’m not sure how to think about the tiara....I’m not quite royalty so..why am I wearing it?”

Home Idle 2: “This gown is so sparkly, I look like fresh snow in the sun.”

Home Idle 3: “Kalim seems very excited as his role as a Prince. I do hope he does well...”

Home Login: “I do wonder when they’re going to announce the Belle of the Ball?”

Home Idle Groovy: “The pudding they’re serving is just marvelous, I must get the recipe.”

Home Tap 1: “Prince Roya and I danced almost all night....I never wanted it to end.”

Home Tap 2: “My fellow maid, Lady Cloche, and I made sure everything was in place such as sewing on missing buttons and straightening things.”

Home Tap 3: “I don’t think Lord Viktor likes crowds much....I saw him going into the courtyard outside.”

Home Tap 4: “My sister, Tinsley, helped me with my hair. As a maid, it’s typically my duty to do one’s hair but....I appreciate Sis for her help.”

Home Tap 5: “My dormmate and fellow retainer to the Draconinas, Lady Nana, found the cupcakes at the dessert table.....I doubt there will be any left after she’s done.”

Home Tap Groovy: “You seem to be without a partner...may I be your partner for this dance?”

Ocs Mentioned - Roya belongs to @rosietrace , Tinsley belongs to @jasdiary , Viktor belongs to @cynthinesia , Nana belongs to @twstinginthewind , and Cloche belongs to @robo-milky

Full body!

#my art!#gwendolyn schnee#twisted wonderland#twst#glimmering soirée#twisted wonderland oc#diasomnia oc#diasomnia#twisted wonderland fanevent#fan event#twst fanevent#fanevent

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Overview of the Fury Species

Class: Reptilia Order: Draconia Suborder: Dracoformia Family: Draconidae ('true' dragons) Subfamily: Draconinae (four-legged with two wings) Genus: Furiadraco (furious dragons; 'furies')

Genus furiadraco - or 'furies' as they are colloquially known, are characterized by oval-shaped flat heads, front-facing large eyes set just at the ends of their snouts, rounded thick legs, distinct wing and tail silhouette and shapes, strong jaw strength, born without teeth, high flying speeds, and extreme intelligence. Most of them are classified under the 'Strike' class of dragons, though not exclusively, and not all Strike Class dragons are furies. These dragons are ambush pursuit predators characterized by their abilities to soar and glide. These dragons are also generally solitary in varying degrees, though also social in varying degrees.

Woolly Howl

Species: Furiadraco lanatus (woolly fury) Class: Strike Weight: 1836lbs (832.8kg) Height: 5'10" (1.78m) Length: 31' (9.45m) Wingspan: 68'4" (20.83m) Active Day Period: Crepuscular Habitat Range: Arctic tundras and alpine cliffs Mating Behaviour: Polygyny

Description: The Woolly Howl is a large dragon characterized most distinctly by the sharp and rough scales that run down from their heads to the bases of their tails and on their chins almost like a beard, named as such because these scales can be mistaken for fur. However, underneath these spiny scales is a layer of shaggy feathers that cover their sides, tails, and legs to help keep this dragon warm in the cold mountain environments it calls home. Unlike other species, they have a belly with segmented scale plating. They come equipped with a set of tail flukes at the tips that help them maneuver around their rocky environments against the strong alpine currents of wind. They most commonly come in shades of pale beige, brown, off-white, stark white, and even blue on their undersides and darker brown, grey, black, red, and blue on their backsides and spiny thick scales. Though, they can also come in much rarer and brighter colours such as red, green, and orange, some even reversing the contrast of colours and others dark all over. Curiously, their eyes and their skin share the same bright rich shade of violet in slightly differing hues, with very rare instances of blue or red eyes. This seems to indicate some degree of leucism or albinism inherent to the species, even if it not phenotypically present, as their eyes can also come in green, yellow, and amber. Their pale wings have dotted flecks at the edges of a darker colour. They are the most unique species of the genus, their eyes smaller and possessing an underbite with their curved needle-sharp canines sticking out from their maws unlike the more uniform conal teeth of their other fellow fury species and are unable to retract their teeth despite being born without them like the others. Curiously, older dragons commonly become darker in colouration as they age and lose more of the contrast of the two main colours on their bodies, creating a rather stark contrast between the older adults and the younger ones. Older dragons also grow far more spines along more of their bodies and have longer scales, including their shins, forearms, the backsides of their wings. Older dragons also grow two sets of thin antlers without prongs - a shorter pair pointing up and back and then a longer pair growing out and up behind them - from the backs of their heads, making them the only dragon species with proper antlers rather than horns. Curiously, males shed their antlers annually while females keep them year round.

Ecology: Woolly Howls are crepuscular dragons, active during dawn and dusk when it is easiest for them to blend into their natural environment to hunt. They are solitary and rather territorial, frequently patrolling their territories to enforce them and defend them from intruders. They are not migratory dragons, however, they do have dens for the winter and the summer, the winter dens up high in the mountains closer to the summits and the summer dens closer to the base, usually by the coasts where its easiest to fish. They may switch to a diurnal hunting schedule during the winter to make the most of the daylight they are allowed. They are one of two fury species that can survive in an arctic environment.

Social Organization: As solitary dragons, they have little social organization. They're not highly aggressive as much as they are more or less indifferent or quicker to avoid than escalate conflicts, but they can be territorial if they perceive threats from other dragons - especially closer to nesting season or during the winter. They are a polygynous species, which means that the males will leave to mate with multiple females while the females will only mate with one male and then have their eggs. However, sometimes females will tolerate having neighbouring dens during the winter.

Communication: Woolly Howls are not a particularly vocal dragon, but they can perform sounds such as roaring, hissing, rumbling, growling, and purring. Instead, Woolly Howls communicate through their body language, using their stances, their wings, tails, and the scales on their bodies to do this. Notable examples are rattling their scales as a threat display, laying them flat to show a relaxed and comfortable demeanour, sticking them out to show that they're alert, or raising them up to show that they're irritated or angry. A contended or happy howl will allow their scales to ripple, like wind blowing through tall grass in waves.

Diet and Hunting: Woolly Howls are ambush predators, reliant on camouflage to hunt their choices of game. They will blend in easily against the rocky alpine cliffs that they live in to ambush small mammals and wild boars and mountain goats when they hunt on the ground, or they will fish during the summer closer to the shore. When hunting from the air, they have a rather unique breath weapon that allows them to essentially force prey to take shelter, making them easier targets to stalk on the ground. Their breath weapon is a burst of ice that explodes and, while in the air, will cause a brief hailstorm from above. The howls will then alight down to land on the ground and sense where its prey is, using its scales to pick up on subtle vibrations caused by sound and their strong sense of smell.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Woolly Howls reach maturity at one year of age, making them one of the fastest aging species in this genus and the quickest to be able to produce offspring. Their clutches typically consist of 2 - 6 hatchlings and can have offspring yearly. They will bury their eggs underneath the tundra and permafrost, keeping them protected until they hatch in a matter of months during the spring, born shortly before the mother takes them down to the summer den to teach them to fish. Maturity is marked when they reach the winter and are able to make a catch on their own, and then they leave the nest. When they're born, their thick spiny scales are soft and pliant, almost making them like feathers to the touch until they dry off and harden in the cold air, forming a natural armour as their feathers then continue to dry. Their feathers have an incredibly soft velvety texture until they reach maturity, obtaining their more shaggy texture at adulthood. The average lifespan of a Woolly Howl is anywhere from 50 - 70 years.

Habitat and Distribution: Being one of two fury species capable of surviving in arctic climates, they don't have too much competition from other fury species. They don't even have much competition with other arctic species, as they live on the summits of mountains during the winter. It's threats from the coast during the summer that are the biggest threat to them, or being injured during a hunt while trying to take down larger game.

Sand Wraith

Species: Furiadraco arenosum (sandy fury) Class: Tidal Weight: 1687lbs (765.2kg) Height: 5'6" (1.68m) Length: 27'1" (8.26m) Wingspan: 59'9" (18.21m) Active Day Period: Crepuscular Habitat Range: Coasts and shallow waters Mating Behaviour: Serial Monogamy

Description: Large rich orange-brown dragons with dark speckling and sharp spines all over their bodies, giving them a rather thorny appearance. They have dark tipped spins along their wings, down their spines, and along their foreheads and out the backs of their heads in a crown-like crest. They have dark masks across their eyes that help reduce glare from the sun when they're awake during the day that help them see better when they hunt. They possess the same rudder fins at the base of their tail common with other fury species, however they do not have pronounced tail flukes like many other members do, instead possessing two sets of much smaller triangular tail fins closer to the tip, the smallest pair almost at the tip of the tail. Their eyes can come in green, yellow, and amber. Older Sand Wraiths have more spines along their bodies, particularly along their brow ridges giving them a more rugged and intimidating appearance compared to the younger ones. Sand Wraiths that live much deeper underground than usual can sometimes come out of the ground with beautiful gem growths emerging from their scales. Thankfully, this doesn't seem to be harmful to them. Though their most common colours are earthy tones with darker mottling, it is not the only colour they can come in and they can actually come in a rare, but wide variety of bright colours that can actually help stun victims when they come out of the ground by essentially flashing them when they suddenly burst out from the sand as opposed to their more common colourations that seamlessly blend into the sand. Although they are a diurnal species, their scales aren't as tough and they are susceptible to sunburn, so will remain buried under the sand for the majority of the time or stay in large tidepools and shallow waters. They're capable of retracting their conal teeth back into their wide set jaws, extending back further than their eyes set on the fronts of their heads.

Ecology: Due to their sensitivity to sunlight, they are crepuscular, able to take advantage of the light of day without risking too much bodily harm while they hunt. They sleep at night, buried in the sand so that they can sense their surroundings and be protected by their camouflage, and will bury themselves during the day underwater to shield themselves from the sun while waiting for stray prey to wander close or to keep watch for predators from below and will briefly come up for air when they need to intake it. The biggest threat to Sand Wraiths are other coastal dragons and especially larger aquatic dragons such as Scauldrons and Thunderdrums.

Social Organization: Sand Wraiths are not closely social, but are quite amicable and easy-going around other dragons and members of their species, sometimes even congregating in groups by the shore during the dawn and dusk if they're in the same place at the same time. They're not particularly territorial, often moving to different nearby beaches and coasts by the time the sun is up or goes down. They are the only member of this genus to practice serial monogamy, mating during the spring with an elaborate courtship ritual consisting of a dance and demonstration of den construction before they stay together for the remainder of the season until their young reach maturity and leave the nest.

Communication: These dragons have a standard range of vocal communications, roars, snarls, shrieks, hisses, growls, purrs, warbles, and chortles. However, these dragons are known for their guttural chittering that they use to communicate while in groups, presumably as a method of warding off intruders by indicating that there is a large congregation nearby. It is also a form of greeting and can be an invitation for a congregation. When they're threatened, they will arch themselves in such a way that will cause their spines to bristle, making them seem more threatening and much larger to opponents.

Diet and Hunting: Sand Wraiths are ambush predators, burying themselves underneath the sand in the water to hunt them. They are primarily pescatarians, though they may also hunt small wading birds or small mammals hunting by the shore if they happen to be close by and within range. They will both hunt in the water and on land, depending on the time of day. While they don't use their breath weapon to hunt, they do have one and a rather unique one at that - hardened balls of sand compacted in an organ similar to a gizzard, and whenever they need to expel it, they will fire it at the same time as their (comparatively weak) fire, which causes a searing explosive spray of sand to blind and disorient their enemies.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: These dragons typically reach maturity at one year of age, able to produce eggs at that time as well. They will usually have clutches of 2 - 3 hatchlings at a time. They are capable of having clutches yearly and typically live on coasts year round south of the arctic shelf. Once they couple during springtime congregation, they will then lay their clutch on a beach, burying them underneath the sand and in a matter of months, they will then hatch and instinctively make their way into the water to bury themselves in the shallow water and begin hunting for food. The hatchlings are born with their teeth and their canines will actually grow to extend out of their mouths the older they get. The parents will take turns protecting the hatchlings until they are a year old and no longer need supervision. The parents will then separate and then will find a new mate the next breeding season. The average lifespan of a Woolly Howl is anywhere from 50 - 70 years.

Habitat and Distribution: As a semi-aquatic species, the Sand Wraith stays predominantly near coastlines and will prefer to stay away from colder climates further north. They cannot survive in deep water and are not very adept swimmers, so they are restricted purely to coastlines not situated in the arctic regions. Their sensitive scales in the sunlight makes it impossible for them to migrate reliably, so their distribution is quite limited.

Desert Wraith

Subspecies: Furiadraco arenosum desertum (a raging sandy desert) Class: Tidal Habitat Range: Coasts, shallow waters, and deserts

Unlike their parent species, the Desert Wraith subspecies is capable of migrating and is a nomadic species unlike the Sand Wraith. Its pale rose scales broken up by the black stripes across its body help protect it from being harmed by the sun. Desert Wraiths will migrate to the deserts south of the equator to congregate and participate in the breeding season and will lay their eggs in the sands of the desert and will bring the hatchlings on a mass exodus back north after the spring once they're able to fly under the guidance of the adults.

Spotted Sea Fury

Species: Furiadraco abyssus (abyss with a furious dragon) Class: Tidal Weight: 3552lbs (1611.2kg) Height: 13'7" (4.13m) Length: 64'8" (8.74m) Wingspan: 129'5" (39.44m) Active Day Period: Crepuscular Habitat Range: Seas, coasts, and caves Mating Behaviour: Polygyny

Description: The largest species of the furies and speculated to be the oldest, these semi-aquatic dragons are perfectly suited for the water. One of the few species to display slight sexual dimorphism, females are typically a bit larger than the males. It is speculated that while these dragons still exist alongside the other fury species, that this species is the genetic progenitor of both Night Furies and Light Furies, due to the dark colouration on their backsides and their sharp intimidating shapes lending to that of the Night Fury and their pale glittering undersides and semi-aquatic natures lending to that of the Light Fury, although this is purely speculation. The Spotted Sea Fury is a equipped with a series of fins that run along its tail down to its flukes that help it maneuver gracefully both in water and in the air, however they're not as adept at flying as they are at swimming and aren't capable of taking off flying immediately from the ground due to their long and thick tails, thus they need more of a push in order to get airborne. Strangely enough, unlike other species, their scales are reported to be incredibly smooth when touched from its snout to its tail, but extremely rough in the opposite direction. This likely makes them even more adept swimmers, able to easily cut through the water without much resistance. Although they're called 'spotted,' they don't exclusively come in spots. They come in a variety of different shades of mottled grey in varying degrees of contrast between the undersides and backsides, though the underside is always paler and covered in glittering scales and their backsides are always grey and mottled. It helps them camouflage both from above and from underneath the water as they swim. They can just be mottled, speckled with a series of dark flecks like flurries of dark ash, painted with dark rosette spots not unlike that of big cats, or even stripes in some very uncommon cases. Their eyes can come in varying shades of silver to dark grey and even almost black, which is incredibly unnerving to come across, blue, and more uncommon colours like green, yellow, and even amber. The appendages on the backs of their heads resemble ears and serve the same function, the others surrounding the two large ones just as integral to their adept senses that help them sense a variety of different things, such as creating an auditory soundmap of their surroundings, sensing pressure changes, acidity, and salinity changes in the water around them. They also serve as a method of scaring off opponents, flaring up to make themselves seem bigger and more threatening. The little ones that line the undersides of their jaw can be used to tell the age of a Spotted Sea Fury, growing more of them the older they get. Their echolocation is also exceptional for life underwater, though because they don't have gills, they do have to come up for air despite being able to hold their breaths for hours at a time. Though they lack a breath weapon, they make up for it with their powerful teeth and incredibly strong jaws, able to shatter a dragon's femur with a single full-force bite and tear through tough sinews and tendons like paper. Despite being the largest member of the fury species, they have proportionally shorter legs, which suits them well for life underwater while making terrestrial living and locomotion a bit of an inconvenience.

Ecology: Spotted Sea Furies are crepuscular, which means they are active during the twilight, periods of dawn and dusk. The low light makes this period of time ideal for hunting, as it allows them even better camouflage as they hunt. Few aquatic dragons are as feared as the Spotted Sea Fury, though its extremely elusive and solitary nature makes them rare to come across, though terrifying to be pursued by. However, they are extremely vulnerable in the air to other dragons more adept at flying, and as such are extremely cautious of large airborne dragons. Though, they will actively avoid Thunderdrum territory due to the painful strain of their thunderous calls on their extremely sensitive hearing.

Social Organization: Unlike the majority of fury species, Spotted Sea Furies are extremely solitary, territorial, and aggressive even to their own kind and rarely seek out other dragons for company. They are a polygynous species, which means that the males will leave to mate with multiple females while the females will only mate with one male and then have their eggs.

Communication: Spotted Sea Furies are not particularly social dragons and aren't very expressive externally otherwise, only visibly being 'at rest' or 'threatening.' They will let out a warning low bellow throughout the water or up above land as a method of marking their territory to other dragons, and can make vocalizations like grunting, chuffing, roaring, bellowing, and moaning. They will chuff as a neutral greeting to one another, but otherwise will vocalize as a warning to others to stay away.

Diet and Hunting: As solitary hunters, they will not work with other dragons to hunt for fish. Though, sometimes they will pursue land animals too close to the water and stalk them until they have a chance to drag them under the water to drown them and then eat them. When hunting larger animals, these dragons will clamp their strong jaws and sharp teeth down onto their necks to either suffocate them or break their necks in order to kill them and eat them. They are pursuit predators and persistent ones at that and will track their prey down for miles and even hours completely unnoticed until their unfortunate victims tire and let down their guards.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Spotted Sea Furies typically reach maturity at 2 - 3 years of age and females will begin to be capable of producing offspring at this stage. They will usually have clutches of 1 - 3 hatchlings at a time. They are capable of having clutches yearly and typically live in abyssal waters throughout most of the year until they couple in the winter and are found more commonly in shallow waters. They will lay their eggs in tidepools on craggy coastlines since their rocky eggs camouflage as large boulders against the cliffs and crags, the mother leaving the eggs alone to incubate in the tidepools and only coming back to check on them twice a day until they hatch. Unlike other species of their genus, they are born with their teeth and they cannot retract like a majority of them can. The hatchlings age very quickly, fully independent in a matter of months and leaving their mothers by the end of the year to start their own lives. The average lifespan of a Spotted Sea Fury is anywhere from 30 - 110 years.

Habitat and Distribution: One of two fury species capable of surviving in arctic climates, Spotted Sea Furies live north in the arctic waters in the depths, only surfacing when they need air and inhabiting shallow waters during the mating season, when they venture slightly south during the winter to have offspring. They're extremely elusive to people and even other dragons, but are known to be alive. By how many, it's not known, but they are a living species. They can't live in high places like mountains and never venture far from the coasts by the water, only able to sleep in the craggy cliffs due to their colouration allowing them to camouflage along the rocks.

Night Fury

Species: Furiadraco noctus (a furious night) Class: Strike Weight: 1776lbs (805.6kg) Height: 5'9" (1.75m) Length: 28'8" (8.74m) Wingspan: 50'3" (15.33m) Active Day Period: Nocturnal Habitat Range: Coasts and caves Mating Behaviour: Monogamy

Description: The Night Fury is a large dragon equipped two rudder fins at the bases of their tails, and a set of flukes at the ends of their tails that allows them not only to fly, but to be able to take off immediately from a stationary position. Females are slightly larger than the males, one of the few dragons to display slight sexual dimorphism. These dragons are known for their black scales, coming in various deep shades and hues of black and even coming with subtle patterning of spots and blotches, though these patterns fade with age, and their eyes can come in blue, green, yellow, and amber. The appendages on the backs of their heads resemble ears and serve the same function, the others surrounding the two large ones just as integral to their adept senses that help them sense pressure changes in the atmosphere and help with auditory triangulation. The little ones that line the undersides of their jaw can be used to tell the age of a Night Fury, growing more of them the older they get. They walk on thick muscular legs and plantigrade feet that allow them to stalk silently on the ground. They're capable of retracting their conal teeth back into their wide set jaws, extending back further than their eyes set on the fronts of their heads. The row of spines along their backs can split apart into two flexible rows of them, which grants them exceptional maneuverability in the air. They also are capable of harnessing the power of electrical storms to heat their scales up hot enough to cause them to have a reflective quality that allows them to cloak themselves, though their natural colouration already allows them perfect camouflage at night when they are most active, as they are nocturnal. It is theorized that it is a last defense for when they're caught in a lightning storm and thus can't hide as easily in the flashes of lightning from one of the few dragons that can rival them - the Skrill. They're also exceptionally suited for life in caves as they're also capable of using echolocation to navigate in the dark cramped spaces.

Ecology: Night Furies are nocturnal, one of the few species of dragons strictly so. Their natural adaptations make them the most successful and feared hunters of all dragons, even other fury species. As such, they have very few rivals when it comes to competition - the Skrill, the closest genetic relatives of the fury species, and Deathgrippers, a known predator of the vast majority to other dragon species. They're most active on nights when the moon isn't full, tending to avoid hunting when exposed under the light of a full moon.

Social Organization: These dragons are primarily solitary once they come of age. They're not particularly territorial or aggressive to other dragon species by default, though they may have aversions towards dragon species that burrow underground due to their solitary nature being a vulnerability in close range combat. They're small compared to many other dragon species and their fins are extremely vulnerable, so they will avoid skirmishes whenever possible. Although solitary, Night Furies mate for life and once they choose a mate, they bond permanently and will have multiple litters over the course of their lives.

Communication: Having a wide range of vocalizations, including purring, roaring, warbling, crooning, chortling, gurgling, hissing, snarling, chuffing, shrieking, and bellowing. They also communicate through their eyes, tails, ears, and even their teeth. They're an incredibly expressive dragon and quite proactively communicative and they will adapt their communication style to whomever they are addressing. Though not highly social creatures, they have excellent social skills and are incredible communicators even to other dragon species. They will more often warn before they attack, more keen to resolve conflicts rather than escalate them. They also communicate with their body language, resting their wings when they're relaxed and comfortable or arching their backs to flex their spines and flare their wings to make themselves look bigger as a threat display when threatened. They're not aggressive by nature and respond well to conciliatory gestures and clear communication. They will often show their retracted teeth as a sign of demonstrating absent ill will or absent threat.

Diet and Hunting: They hunt alone, though sometimes they may aid in a hunt already in progress by attacking their enemies to allow the main group to hunt with less danger to themselves. Since they are extremely stealthy, especially at night, their involvement is never contested since even if they aid in a hunt, they prefer to hunt for themselves rather than take the spoils from another even if they contribute. They are primarily pescatarians, their naturally sleek aerodynamic bodies making them excellent for hunting at sea, but a fearsome foe for any other dragon species unfortunate to be out at night. They are characterized most strongly by their extreme speed and their unique plasma blasts as a form of fire they breathe. These dragons are the fastest known dragons of any species, capable of reaching top speeds exceeding the sound barrier - that being 761 - 770 mph (1224.7km/h - 1239.2km/h) when they dive. When they hunt, they will typically dive into the water at high speeds and come back up with fish, but when hunting on land, they will dive bomb their victims and hit them with a plasma blast to kill them, the force of the blast due to the speed more dangerous than the heat of the fire itself.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Night Furies typically reach maturity at 2 - 3 years of age and females will begin to be capable of producing offspring at this stage. They will usually have clutches of 2 - 4 hatchlings at a time. They usually have clutches between 1 - 2 years between each other and will lay their eggs deep in caves where it's dark and they cannot be easily found, the parents taking turns watching the nest and the hatchlings and bringing back food for them. Night Furies hatch without their teeth and will slowly grow them in as they age within a year and then are able to retract once they grow into their wings. Their wings are rather small when they initially hatch, but outgrow the hatchlings rather rapidly, making them a bit clumsy when they're growing up. By the end of the year, they will be able to fly and hunt on their own and leave the nest within 1-2 years after they're able to and will lead solitary lifestyles, though siblings may stay together for a short period of time before they separate from each other. Mated pairs will return to the same nesting site to lay their next clutches of eggs. The average lifespan of a Night Fury is anywhere from 30 - 70 years.

Habitat and Distribution: Night Furies live in the northern hemisphere just below the arctic shelf, unable to survive in consistent arctic temperatures and climates. They live in island archipelagos in caves by the coasts, considering that they cannot fly considerably long distances without tiring. Although before, they were rather seldom in number, rarely seen by humans and even anomalies among other dragons, they were a sizable number once...but now, they are unfortunately functionally extinct. Despite being the most dangerous species of dragon among others, with only a couple competitors and genuine threats from other dragons, it seems that the greatest threat to them...was humans, Grimmel the Grisly having made it his personal mission to hunt them into extinction. For all intents and purposes, he succeeded, only one living member left of the species remaining by incredibly astounding luck - Toothless, whose current residence is on Berk and is protected by the island's chief, Hiccup Horrendous Haddock III. Though they are able to hybridize with other fury species, the Night Fury is functionally extinct, unable to survive with only one surviving member.

Light Fury

Species: Furiadraco lumen (furious light) Class: Strike Weight: 1600lbs (725.74kg) Height: 5'7" (1.71m) Length: 22' (6.7m) Wingspan: 42' (12.8m) Active Day Period: Diurnal Habitat Range: Alpine cliffs and coasts Mating Behaviour: Monogamy

Description: A large sleek dragon characterized by their smooth, white, scales with glittery phantom stripes almost invisible to the naked eye. They are the smallest members of this genus and the most vulnerable to other dragons due to their smooth and soft scales and lack of defensive or offensive properties, making them easy targets. Their physical build is most similar to that of the Night Fury, sporting two rudder fins at the bases of their tails and tail flukes at the tips, though with a pair of small additional triangular notches at the bases of their flukes. In place of having defined spines, they instead have something of a smooth dorsal fin running down their spines from their necks to the base of their tails and similar fins attached to the outer edges of their legs from the elbow down to their ankles. Older individuals may gain additional dorsal fins beside their main one along their spines. They're capable of retracting their conal teeth back into their wide set jaws, extending back further than their eyes set on the fronts of their heads. Though they are in various shades of white, they can also come with a myriad of darker patterns on their backsides, such as spots, speckles, mottling, blotches, patches, waves, and even stripes. The most common eye colour is blue and silver, though they can also have yellow, amber, and green. Their physical shape allows them to take off flying immediately from a stationary position on the ground, making them adept and incredibly fast fliers. Their foreheads are round and slightly more pronounced, better facilitating their ability to echolocate, and they sport appendages on the backs of their heads - two large ones serving as ears and two small ones on the sides of their heads as additional sensory aids that help them sense things like pressure changes in the atmosphere and auditory triangulation. There is slight sexual dimorphism in the species, females having rounder wings and fins and shorter ears than the males, whose wings and fins are more angular. Some females can even have more elaborately shaped fins on their tails and their backs. They walk on muscled plantigrade feet that allow them to stalk silently, though their musculature is more lithe and built for speed and agility rather than raw strength, indicating that they’re quicker to flee than they are to fight. Due to their lack of defensive properties, they’ve instead developed an evasive adaptation, able to cloak themselves by flying into the fire of their plasma blasts to heat up their soft and smooth scales and turn them into a reflective mirrorlike quality, making them invisible in the air. Their pale colouration grants them perfect camouflage in flight during the day in the clouds, but the glittery quality of their scales when they’re not cloaked also provides another important defense, able to blind their foes at the right angle when their scales reflect the light of the sun in just the right way.

Ecology: Light Furies are diurnal, the only species strictly so due to their stark white colouration making them vulnerable to attack before sun rises and after the sun sets. However, their natural adaptations make them fearsome daytime hunters, able to remain mostly invisible in the skies until they strike. Though, due to how small and vulnerable they are especially compared to species in their own genus, they are extremely skittish around other dragons especially in large groups. They will prioritize getting back to their nesting sites before sundown over a successful hunt or avoiding a storm. A Light Fury caught out at night is an easy target for many species of dragons, especially dragon-eaters like Deathgrippers. Skrills are also a dragon they fear because they have no natural defenses if they’re caught in a lightning storm, especially at night.

Social Organization: Of all the species in this genus, the Light Fury has the most complex and variable social system in comparison. There are actually several social groups Light Furies fall into: solitary females, solitary males, mated pairs and/or their hatchlings, male coalitions, and matriarchal dominance hierarchies. Individuals typically avoid one another, but they do remain generally amicable. The most common groups are the solitary males and females, followed by mated pairs, male coalitions, and last by matriarchal dominance hierarchies. Though primarily solitary, Light Furies mate for life and their mate selection process is rather complicated, individual preference playing a huge part. Though, generally the males are the ones tasked with impressing the females through various rituals, including demonstrating the ability to stay hidden. Most of the time, brighter scales are more desirable on average, though some individuals demonstrate particular preferences and will refuse many mate potentials until they find one they are content with. Then, there are male coalitions. Male coalitions are typically formed by brothers born in the same litter after leaving the nest, but sometimes unrelated males can form or be accepted into coalitions and typically only leave once they've found a mate. And then finally, the rarest social group Light Furies partake in is a matriarchal hierarchy where a female will have control over a group of unmated females, typically her daughters and granddaughters, and her sons and grandsons will leave the group once they reach maturity. Females will either leave the group once they find a mate or assimilate their mate into the group and raise their hatchlings within it.

Communication: Having a wide range of vocalizations, including purring, whinnying, chirping, warbling, crooning, chortling, gurgling, hissing, snarling, nickering, shrieking, meowing, and bellowing. They also communicate through their eyes, tails, ears, and even their teeth. Though they are capable of a variety of expressions, they are also rather reserved and will be more likely to keep their motives and true feelings more hidden underneath the surface than show them openly. They are not highly social creatures and would rather avoid contact if possible, skittish and evasive by nature. They tend to keep their body language closed and restrained, keeping their extremities close to their body and always ready to leave at a moment's notice if necessary to flee from a potential conflict.

Diet and Hunting: Solitary hunters alone, cooperative group hunters in coalitions and matriarchal hierarchies. When they live solitary lives, they only need provide for themselves and thus find more success, however when they hunt in groups, there's more depending on them so their hunts come with more risk and thus more chance of failure. They hunt during the day when they are best adept to blend in with the sky and ambush their prey from above without warning. They are primarily pescatarians, though when they are in groups, they will hunt for larger game on land. They are characterized most strongly by their extreme speed and their unique plasma blasts as a form of fire they breathe, similarly to the Night Fury. When they hunt, they will typically dive into the water at high speeds and come back up with fish, but when hunting on land, they will dive bomb their victims and hit them with a plasma blast to kill them, the force of the blast due to the speed more dangerous than the heat of the fire itself, usually cloaked so that their victims don't even see them coming in order to react. However, an unfortunate byproduct of their stark colouration and weak offensive and defensive builds, if they're caught by other stronger dragons, it's not uncommon for their kills to be stolen from them and for them to be driven away, forced to either attempt another hunt or go hungry. The dragons they avoid the most that will actively pursue them to hunt them are Skrills, Light Furies having an instinctive fear of them.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Light Furies typically reach maturity at 2 - 3 years of age and females will begin to be capable of producing offspring at this stage. They will usually have clutches of 1 - 8 hatchlings at a time. They usually have clutches between 1 - 2 years between each other and will lay their eggs either in a cave, a rocky alcove on a cliffside, or in a tidepool on the coast hidden away from sight. Females will guard the nest while the males hunt, though sometimes they will trade positions closer to hatching. They hatch without their teeth and will slowly grow them in as they age within a year and then are able to retract once they grow into their wings. Compared to other dragon hatchlings, Light Fury hatchlings are more vulnerable due to their stark colouration and curious nature, necessitating close supervision by the mother until they mature. Many hatchlings do not survive, either due to environmental factors or being hunted by other predators and dragon species. By the end of the year, they will be able to fly and hunt on their own and leave the nest within 1-2 years after they're able to and will either lead solitary lifestyles or form into coalitions. Mated pairs will return to the same nesting site to lay their next clutches of eggs. The average lifespan of a Light Fury is anywhere from 20 - 50 years.

Habitat and Distribution: Light Furies live in the northern hemisphere just below the arctic shelf, unable to survive in consistent arctic temperatures and climates. They live in island archipelagos in shallow caves either by the coasts or up on mountains and alpine inclines where they can better camouflage against the pale colouration of the summits, considering that they cannot fly considerably long distances without tiring.

Skrill

Class: Reptilia Order: Draconia Suborder: Dracoformia Family: Draconidae ('true' dragons) Subfamily: Draconinae (four-legged with two wings) Species: Falsumwyvern electrica (electric false wyvern)

Class: Strike Weight: 1800lbs (816.47kg) Height: 6' (1.84m) Length: 22' (6.7m) Wingspan: 40' (12.19m) Active Day Period: Nocturnal Habitat Range: Mountains, forests, and glaciers Mating Behaviour: Monogamy

The skrill is the sole member of the genus Falsumwyvern. It is the closest genetic relative of the genus Furiadraco despite being classified as a wyvern (two-legged two-winged dragon) phenotypically. It also does not display the social inclination nor amicability of its fury cousins.

Description: A large dark-coloured dragon with a paler underbelly with brighter markings that run from its eyes down to the tip of its tail in a cloudy line like fire. They can come in various shades of black, dark blue, dark violet, and grey with their underbellies and markings following a similar hue scheme to match, though they can come in rarer colours like brown, red, green, and even white. Their wings have defined hooked thumb claws that allow them to climb with ease when they have to crawl on all fours, as they only have two legs. They have flat, round, oval heads with small typically yellow, amber, or red eyes and a single hooked horn growing out from the tips of their snouts, with a crown of narrow sharp spines on the backs of them as well as as a line of similar spines that run down their backs all the way to their tails. These narrow metallic spines help to channel lightning and electricity through their bodies, almost making them a living conduit or conductor. These spines also help them sense barometric pressure changes and ionic charges in the atmosphere as well. They have long narrow tails, almost whiplike in nature. Their physical build is similar to that of birds, their legs equipped with opposable claws capable of grabbing and snatching their victims with three in front and one in back. They also possess an underbite with hooked narrow teeth poking out from their maws. They’re characterized most notably by their ability to channel and even fire lightning in concentrated streams and sudden blasts, these streams likened to ‘white hot fire.’ They’re even capable of outspeeding Night Furies by riding lightning bolts during electrical storms, though due to the fact that they can only do this through electrokinesis, it cannot be counted towards its top flying speed generally. Older Skrills are not much different than the younger Skrills other than size, though the older ones do possess a distinctive green glow at the base of their spines and the spines on their backs are significantly longer in comparison to the younger Skrills.

Ecology: Skrills are most typically nocturnal, which makes them especially dangerous to encounter. However, they are also capable of hunting during twilight if necessary and will sometimes travel during the day if it’s darkly overcast or if there is an electrical storm to take advantage of. They’re especially dangerous to encounter in an electrical storm due to their typically dark colourations and their mastery over electricity, making conflicts with them practically a death sentence. Though, the one advantage that others have is that because they generate a natural electric field, it can telegraph their proximity before they’re properly spotted, reported to make all the hair on someone stand completely on end. There are very few dragons that can truly rival them, only having a true competitor in Night Furies, though even then, the small population of them doesn’t make them an active threat. They’re one of the few dragons capable of hibernating in frigid environments, and even able to be completely frozen in glaciers for centuries and emerge as alive and fierce as before.

Social Organization: Skrills are extremely aggressive and intelligent dragons with a profound sense of loyalty, retribution, and justice. They are capable of holding grudges for decades and may even pass that grudge onto their young. However, despite this, they are capable of recognizing when retribution has been satisfied and if someone helps them in a meaningful way, they will demonstrate a profound sense of loyalty towards the one who helped them. They will often reciprocate this effort, if someone has gone out of their way to help them, they will find a way to repay that favour. Though aggressive and primarily solitary, they are not entirely incapable of making social bonds, mating for life and sometimes travelling in very small flocks. They are deeply devoted to those it bonds with and aggressively protective and territorial over them.

Communication: Roaring, screeching, clicking, growling, snarling, barking, and cawing are its numerous vocalizations. Many of these serve the purpose of marking their territories, warning away any potential aggressors and intruders. They are not often heard during thunderstorms, though the sounds of the storms can often drown them out. However, they have a unique method of communication being the electrical fields and current they can naturally store and generate, the frequency of the natural humming they emit being able to communicate nonvocally with others of their kind.

Diet and Hunting: Skrills are opportunistic ambush predators that hunt from the dark sky and especially during thunderstorms. Though they are primarily pescatarians, they do eat land animals and even other dragons as well - which is what makes them so dangerous to other dragons. They are also one of the only species of dragon that eats and hunts electric eels as an essential part of their diets. Due to the shapes of their opposable claws on their feet, it makes it quite easy for them to snatch their prey from above and then electrocute it before killing and consuming it.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: Skrills will begin courting at 1 year of age, but may not bond with one another for another 2 or 3 years. They will scope out and establish a territory before they create a nest and will aggressively defend said territory and food. They will return to the same nesting site every year to have another clutch of eggs. Depending on the habitat, they can either build their nests high up on mountain cliffs, in the canopies of trees, or within a glacier cavern. They typically lay their eggs in the winter, usually 4 - 6 eggs at a time. The female will stay to brood the nest while the male goes out to bring her food and will bring food to the hatchlings once they emerge. Within two months, the hatchlings will be able to fly but will still stay close to the nest for the rest of the year until they leave to start their own lives. Skrills can live from 50 - 120 years.

Habitat and Distribution: These dragons have a wide range in and above the arctic shelf, able to live and hibernate in frigid environments as well as living on mountains and wooded boreal forests. They typically prefer living in higher altitude closer to the sky, as this allows them optimum hunting opportunities as well as quicker and easier access to thunderstorms as they appear. They typically chose darker places to nest and create dens as their typically dark colourations allow them perfect camouflage in these environments, especially at night.

#ooc#lore#httyd#woolly howl#sand wraith#desert wraith#light fury#light fury concept#night fury#spotted sea fury#skrill#furiadraco#furiadraco lanatus#furiadraco arenosum#furiadraco arenosum desertum#furiadraco abyssus#furiadraco noctus#furiadraco lumen#falsumwyvern electrica

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sick and got way too into the ID rabbit hole, so let's discuss why this guy is (Probably!) either in the Gonocephalus genus or Acanthosaura genus and why it can't be an Iguana!

I want to start by saying although I have more experience with lizards and herpetology than your average person I am not an expert.

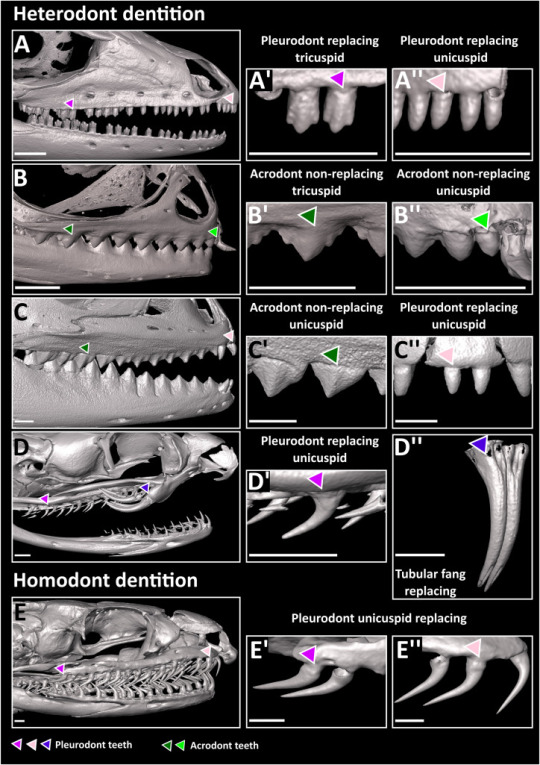

Where better to begin than with the teeth, the most gremlin-like part of this guy! This animal has very shark-like teeth which while on their own might not be very informative, combined with a few other traits lets me ID this tooth type as acrodont. Now acrodont teeth are when the tooth itself is fused to the jaw bone which is different from our tooth attachment style as mammals, socketed thecodont teeth.

Figures from Razmade et al., 2023 and Kavková et al., 2020

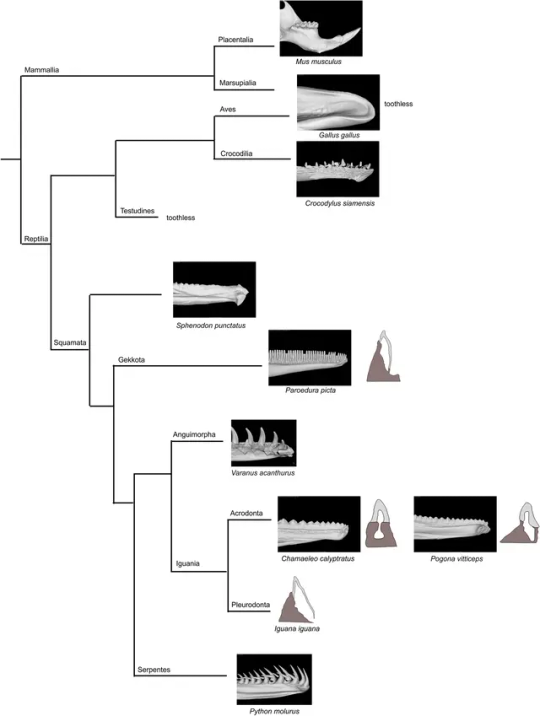

This is also different from Iguanas, which have Pleurodont teeth like most other lizards. In fact, acrodont teeth are somewhat rare across squamates and are really only in the clade Acrodontia (and some amphisbaenians but this is definitely not an amphisbaenian, if you look them up you can see why)! Acrodontia includes two clades, agamids and chameleons which narrows our search down by a lot. However, we can also see in the picture that this animal doesn't have zygodactyl feet like chameleons so it must be some sort of agamid.

Now agamids are very widespread and diverse, in fact, bearded dragons, uromastyx, thorny dragons, sailfin lizards, and frilled lizards are all agamids, which means that although we narrowed down the clade there are still plenty of candidates. This is where we need to be a bit creative to get whatever information we can from the picture before we sort through the agamid family tree. This animal has green-brown skin and sparse patterning. What patterning it does have is subtle striping on the tail and body. What is notable are the very long arms and legs compared to the body size, and the tall spines/comb along the animal's back extending from the base of the animal's head to the base of its tail. It's very interesting IMO what this animal doesn't have. It doesn't have ornamental scales on its head or cheeks, nor does it have a brightly colored neck (although because we don't know the animal's age we can't rule out that it is some sort of immature animal) It also has rougher/keeled scales on its legs, belly, and tail. Honestly... that doesn't give us a whole lot of information so from here it was a lot of sifting through the agamid family tree.

What I ended up finding was that they seem pretty similar to taxa in the Gonocephalus genus like the Borneo forest dragon or Bell's forest dragon. However, some other sleuths have identified them as the Acanthosaura genus like the mountain horned lizards. I think that both of these are reasonable IDs (biased lol) but let's go over a few of the differences and why we ended up at these clades. For starters, these genera are actually pretty closely related, they're both in the clade Draconinae which includes taxa from southeast Asia and Oceania, and the really cool genus of gliding lizards Draco!

(Acanthosaura capra photo (source/source)(source))

The most likely candidate in the Acanthosaura genus is A. capra, aka the green pricklenape or horned mountain dragon. These animals are often kept in the pet trade, which is one of the reasons they might be pictured chowing down on someone's sweatshirt sleeve (some people in the pet trade also have A. nataliae, A. crucigera, A. lepidogaster, and A. armata but their coloration and spines are different). Many traits fit, as horned mountain dragons have long legs compared to their body size, a tall comb/ tall spines over their nuchal (neck) region, and keeled scales in the same places as the picture. The reason I don't think that it's a mountain dragon is that mountain dragons don't have their spines extending the length of their back, and they also possess a keratinous spike (the horn of the horned dragon) at the back of their eye ridge, which is not seen in this picture. However, again we don't know the age of this animal and the spike/horn doesn't show up in every picture I've seen of horned mountain dragons so I think this is a perfectly reasonable ID for this animal with our available information

(Gonocephalus bornensis (source) (source)) (Gonocephalus bellii (source))

There are a few possibilities in the Gonocephalus genus (also called angle-head lizards or forest dragons) but not many, and it additionally seems like these guys aren't commonly kept in the reptile trade. It seems like Bell's forest dragon, giant forest dragon, and chameleon forest dragon are the more common dragons in the pet trade from this genus but it is very hard for me to find info on how common they are without diving in which I don't have time for so treat this with a grain of salt. This forum and this website both have info on keeping mountain and forest dragons but none of them mention the Borneo forest dragon which makes me sceptical bout my first ID. It seems unlikely if no one keeps them in captivity! So while it looks most like a Borneo to me it would probably be more likely to be a Bell's forest dragon if it is in Gonocephalus. Nonetheless, The reason I think this guy fits with forest dragons is because of the extended comb/spines that stretch from the back of the head all the way to the base of the tail (the perspective makes it difficult to make out but IMO the spines extend all the way) as well as the coloration (look at those tail stripes and the colors!). This is seen in Gonocephalus but not Acanthosaura, but again we have limited info and either hypothesis is reasonable. In fact, I tracked down the original reddit thread that this was posted in and the IDs were either Acanthosaura or Gonocephalus. There are even more threads with this exact picture and ID threads of Gonocephalus that look like the animal in this pic. I think that this is as far as we can narrow it down without any additional evidence like the location of the pics or more pics posted from the pet owner.

Anywho, thanks for bearing with me in this thread.

Dude

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Morphological and molecular differences in two closely related Calotes Cuvier, 1817 (Squamata: Agamidae: Draconinae) with the first record of Calotes medogensis Zhao & Li, 1984 from India

http://dlvr.it/SnKqd0

0 notes

Text

🦎 Common Flying Dragon - Draco volans

📷 Zhao1967

#daily lizard#lizards#reptiles#herpetofauna#herpetology#draco volans#flying dragon#gliding lizard#common flying dragon#draconinae

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

FIVE BANDED GLIDING LIZARD Draco quinquefasciatus

Draco is a genus of agamid lizards that are also known as flying lizards, flying dragons or gliding lizards. These lizards are capable of gliding flight; their ribs and their connecting membrane may be extended to create "wings" (patagia- similar to flying squirrels), the hindlimbs are flattened and wing-like in cross-section, and a flap on the neck (the gular flag) serves as a horizontal stabilizer (the flag is sometimes used in warning to others).

Draco are arboreal insectivores.

While not capable of powered flight they often obtain lift in the course of their gliding flights. Glides as long as 60 m (200 ft) have been recorded, over which the animal loses only 10 m (33 ft) in height, which is quite some distance, considering that these lizards are only around 20 cm (7.9 in) in total length (tail included).

They are found in South Asia and Southeast Asia, and are fairly common in forests, gardens, teak plantations and shrub jungle.

Below showing wings and gular flag. ©A.S.Kono Sulawesi Lined Gliding Lizard Draco spilonotus

#draco#agamid#lizard#reptile#flying lizards#flying dragons#gliding lizards#patagia#gular flag#insectivores#arboreal#asia#south asia#squamata#southeast asia#iguania#agamidae#draconinae

512 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Crowned spiny lizard (Acanthosaura coronata)

Photo by Jeremy Holden

#fave#crowned spiny lizard#acanthosaura coronata#acanthosaura#draconinae#agamidae#iguania#iguanomorpha#toxicofera#squamata#lepidosauria#sauria#diapsida#reptilia#sauropsida#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maybe a Bronchocela jubata (en: Maned Forest Lizard, de: Langschwanzagamen)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruína

Ao norte de Mera fica uma enorme cadeia de montanhas, as Montanhas de Dragão, e no coração dessas montanhas existe um caverna, uma caverna que abriga um gigantesco tesouro, com joias e moedas, gemas e armaduras, os mais diversos tipos de armas, um tesouro digno do mais poderoso dos reis. O mais poderoso dos reis. Krazer é seu nome, e ele é o maior e mais poderoso dragão que já existiu em Mera, sua caverna cheira a fumaça e enxofre, sua magnitude é incomparável, o brilho do ouro reflete em suas escamas negras, escamas essas que cobrem todo seu corpo gigantesco, afiados chifres se estendem de sua cabeça para trás de seu pescoço com chifres menores ao lado de sua face e em seu queixo e ainda uma linha com chifres diminutos acima de seus olhos rubros, possui uma barbatana que começava atrás de sua cabeça e se estende até a ponta de sua cauda, cauda essa que também era repleta de chifres de variados tamanhos, longas garras que mais pareciam lanças e dentes afiados como espadas, gigantescas asas, que quando abertas podem chegar a medir 17 metros de comprimento. A sua volta jazem, além de seu tesouro, os ossos de animais de médio porte que tiveram a infelicidade de cruzar seu caminho. No centro da cadeia das Montanhas de Dragão se encontra o Vale da Eclosão, e nesse vale ficam todos os ninhos com os ovos em fase de choca de todo dragão de Mera, eles são protegidos por algumas fêmeas, que estão sempre os mantendo aquecidos o suficiente para que no momento propicio eles possam eclodir e prosseguir o processo de crescimento. Tais fêmeas também são responsáveis de vigiar os arredores das montanhas, e não deixar passar nenhuma criatura indesejáveis, que possa querer fazer algum mal à espécie. É verdade que o tempo passa para todos, e que para os dragões centenas de anos podem não significar muito, mas Krazer além de ser o maior da espécie é um dos mais velhos, e ultimamente ele tem passado seus dias entre seu sono e sua caçada, e a atenção para o que estava em sua volta não era sua prioridade. No terceiro dia da primavera, o numero de fêmeas no vale estava reduzido, pois uma parte delas tinha ido para a caçada, e as atenções estavam quase que exclusivamente voltadas para as ninhadas, e nenhuma fêmea percebeu a aproximação de um vulto negro nas montanhas. Tal vulto era um ser muito antigo, um habitante das sombras quase tão antigo quanto a própria existência de Mera, e ele estava nas Montanhas de Dragão por que ele tinha um propósito. De maneira sorrateira ele se esgueirou pelas sombras e pelo escuro, evitou as grandes fogueiras que se espalhavam pela grande caverna, que se estendia pelo subsolo da cadeia de montanhas, e encontrou seu destino, o grande salão de Krazer. O grande dragão dormia no centro do salão, em cima de uma gigantesca pilha de moedas, gemas, armas e tudo mais o que qualquer um apenas sonhou que um dia poderia existir em um tesouro, e não percebeu a presença do Senhor Negro, que se aproximava murmurando e sibilando encantamentos de possessão em uma língua desconhecida, uma língua tão antiga quanto o tempo, a língua usada pelos supremos na Era da Criação. O farfalhar de suas vestes e o rolar de moedas acabou chamando atenção para a grande fera alada, que de súbito abriu os olhos a procura do perturbador de seu sono. - Quem ousa perturbar meu sono? perguntou em seu vozerio retumbante - Não sou ninguém além de um servo, que deseja apenas a verdade para Vossa excelência draconina. disse o feiticeiro com falsa modéstia em sua voz - Servo? Desconheço que tal serviço seja feito por algo que não um de minha espécie. - É verdade que não possuo o sangue fervente e nem as escamas de aço de seu tipo, que sou apenas um frágil ser comparado a vossa magnitude, mas venho com boas intenções. Venho avisa-lo de uma conspiração. as palavras do feiticeiro vinham cobertas do mais poderoso veneno que existente - Conspiração? Quem seria o tolo de conspirar contra Krazer? - Ouço sussurros de deposição e regicídio, ó poderoso respirador do fogo. - Deposição? Regicídio? Isto é loucura, mostre-se e enfrente as consequências por tais insanidades. porém, apesar do tom em sua voz, Krazer ficou com uma certa desconfiança sobre a veracidade da informação - É apenas o que sei, magnifico condutor da destruição. O feiticeiro sabia o que suas acusações, junto com os elogios e a feitiçaria que tinha feito, iam causar o efeito esperado no poderoso dragão, pois mesmo sendo de difícil trato, até mesmo a mais obstinada criatura pode ser dobrada perante a chance de perder todo o poder conquistado. E com o dragão não seria diferente. - Como posso acreditar no que falas se nem ao menos você me disse seu nome! questionou o dragão, com um ar de quem começava a acreditar no que lhe era contado - Justo, meu senhor escamoso. Me chamo Danzer, e venho apenas lhe contar o que ouvi por minhas andanças. mentiu o feiticeiro - E como um andarilho possui tal informação? - O que lhe digo é sabido por todos, que o velho Krazer já não é o que foi, que vive cansado e dormindo, que a gordura tomou conta do que um dia foi músculo, seu tempo passou e um jovem deve tomar seu lugar. Todos dizem isso, as fêmeas caçoam e os jovens fantasiam com a esperança de um líder mais forte, ou quiçá, de serem os próximos lideres. Um rugido surgiu do fundo de sua garganta, e uma chama escapou junto com o grito de fúria. O feiticeiro continuou falando suas mentiras e lorotas, continuou com suas enganações e crueldades, e a cólera deixava cada vez mais os olhos de Krazer rubros, como brasas incandescentes. E por horas o feiticeiro falou, e cada vez mais furioso o dragão ficou, e assim ficaram por 3 dias inteiros, com o feiticeiro tecendo seu feitiço de mentiras e com o velho dragão nutrindo cada vez mais um enorme ódio por seus semelhantes, Krazer não caçava e nem comia, e quando alguma fêmea se aproximava ele a enxotava, não queria ver ninguém, apenas tinha ouvidos a dar ao feiticeiro. Seu ódio chegou a um ponto em que o grande dragão em sua fúria resolveu mostrar quem realmente era o verdadeiro rei dragão, mostrar que ele era Krazer, a Morte Alada. Com uma rapidez impressionante, saltou de sua pilha de tesouros em direção a saída, e se e caminhou direto para fora, com suas garras abrindo valas enquanto raspavam pelo chão e com cauda alargando mais as paredes da caverna, enquanto se debatiam por todo o caminho até a saída. Uma vez do lado de fora, mais rugidos foram desferidos, junto com jatos de seu bafo infernal que queimou todas as arvores que haviam no pé da montanha. Em uma batida de asas ele já voava alto, e foi alcançando cada vez mais altura, ultrapassando o pico da montanha e logo as nuvens, para depois, com um mergulho, cair em direção ao vale. O Vale da Eclosão foi o primeiro a sentir a sua fúria, uma fúria de fogo e destruição, enormes jatos saiam de sua garganta enquanto a Morte Alada sobrevoava o vale, ovos foram destruídos no desespero das fêmeas, ninhadas foram perdidas e fêmeas destroçadas enquanto a loucura de Krazer ainda causava confusão e desentendimento. Todo o barulho podia ser ouvido de longe, e outros dragões vieram ver o que acontecia. Entre eles estava Colwen, um jovem dragão de grande porte e cor avermelhado. "Este que quer roubar seu poder" Krazer ouviu em sua na perturbada cabeça, e avançou com força para cima do mais jovem. Sem tempo para poder pensar, Colwen se desvencilhou do ataque para poder tentar mostrar que vieram em auxilio. Ele não entendia a fúria louca que tinha tomado Krazer, e quando o ataque nele falhou, o mais velho não perdeu a oportunidade e atacou o dragão que vinha logo atras. Vendo o que Krazer estava fazendo, Colwen foi para cima dele. - Então tudo que ouvi era verdade! Você realmente quer tomar meu poder! urrou o louco dragão negro Antes mesmo que pudesse formar qualquer frase, Krazer cravou suas enormes presas no pescoço do jovem dragão vermelho, e sentiu o fervente sangue escorrendo por sua boca meio aberta e seu pescoço. - Quem mais ousa desafiar o Rei Dragão? a pergunta foi proferida com um rugido ensurdecedor A matança continuou por dias a fio. Krazer caçava todo e qualquer dragão em Mera e não dava ouvido a suplicas. Ele foi implacável. Toda uma raça extinta, a não ser pelo grande dragão negro, um rei sem seus discípulos. Após a matança Krazer passou dias sozinho em sua caverna com sua mente afundada em confusão, a voz do homem misterioso que tinha lhe falado dias anteriores já não era mais ouvida ele apenas sentia uma energia estranha vinda do vale. Indo até lá, o dragão pode ver gigantescas ossadas e troncos de arvores que ainda queimavam, o vale estava quente com a intensidade de um sol mas bem no meio ele podia ver uma figura toda vestida de negro, era mais alto que um homem normal, e uma veste cobria todo seu corpo, era possível ver apenas uma mão branca como osso segurando um cajado também de cor negra. Ele parecia estar agachado na frente de uma fogueira, com ossos e cascas de ovos ao seu redor, fumaça rodopiava acima de sua cabeça. Logicamente a figura ouvia a gigante criatura se aproximando, pisando e quebrando ossos e arvores queimadas, e quando chegou perto o suficiente ele virou. Krazer ainda não podia enxergar o rosto da figura por causa de seu capuz, mas mesmo assim sentiu uma força gigantesca vindo dele. - Quem é você e o que faz aqui? perguntou o dragão - Não reconheces um humilde servo? perguntou com desdém o feiticeiro, seguido de uma gargalhada debochada - O que fazes profanando solo sagrado? O que aconteceu aqui? confusão tomava a cabeça do grande dragão, que não lembrava o que tinha acontecido - Não se lembra da matança que comandaste? o desdém na voz do feiticeiro era cortante - Matança? O que esta dizendo? - Falo disso! e com um estalar de dedos imagens apareceram na cabeça de Krazer, e ele viu com clareza o que sua memória não conseguia lembra dos últimos dias As imagens vieram como um turbilhão, e invadiram a mente do velho dragão com uma força, como se ele tivesse batido em uma montanha em pleno voo. Não poderia ser verdade, Krazer estava perplexo com o que tinha feito, um ódio queimou ainda mais em seu sangue fervente, e no fundo de sua garganta começou a se formar uma torrente flamejante, porém quando ela foi soltada, não causou nenhum dano ao feiticeiro, que apenas riu alto e ruidosamente. - Eu tenho poder sobre você, criatura. Você obedece o meu comando! disse o feiticeiro enquanto erguia um ovo quebrado ao meio, o qual havia uma poção dentro, o feiticeiro tinha tomado a poção, e depois de ter controlado o dragão por tanto tempo, tinham formado uma conexão, em que ele não poderia matar o feiticeiro e nem o feiticeiro poderia mata-lo, mas o feiticeiro o controlava. - Tolice! rugiu Krazer no mesmos instante em que um brilho intenso subia de seu peito para sua garganta, e com mais um rugido a fera soltou uma longa e poderosa chama na direção do feiticeiro, a chama queimava tudo que tocava, transformando em cinzas os restos da chacina que tinha ocorrido no vale, porém quando ela cessou, Krazer percebeu que o feiticeiro estava intacto. O feiticeiro continuava parado em sua frente, e com um movimento suave retirou o capuz que cobria sua cabeça. O dragão nunca tinha visto criatura parecida, ele não tinha nenhum fio de cabelo em sua cabeça, que era branca como osso, possuía orelhas pequenas e os olhos eram apenas fendas em sua fronte. A boca não passava de um rasgo, que quando fechada mais parecia uma cicatriz, e um nariz pequeno e achatado. - Nada do que você fizer pode me afetar dragão, você não pode me matar, e nem o contrario, sua vida será estendida para a eternidade, e para todo o sempre você se curvará sob minha vontade! o feiticeiro gritava essas palavras cheias de veneno e poder, e o dragão, que um dia foi o mais poderoso ser de Mera, não passava agora de um fantoche. - Não é possível. rugiu o dragão. Isso não é verdade, não existe ninguém com poder suficiente para fazer tal encantamento. - Você não sabe de nada, não sabe de onde vim, não sabe por onde caminhei, não sabe o que vi em minha vida, passei por todo tipo de provação para adquirir o conhecimento que tenho hoje. Você realmente acha que ia ser difícil de enganar tal criatura tão cheia de si, tão arrogante, não precisei nem me esforçar muito para ter o resultado esperado. as palavras do feiticeiro eram despejadas com ódio e desprezo, e grande energia emanava dele nesse momento. Chega, você é meu para usar como bem desejo, e esse vale é prova disso. O vale já não podia mais ser considerado um vale, pois toda e qualquer vegetação que tinha ali já não existia mais, jazia junto com cinzas, ossadas e ovos partidos, aquilo era um cemitério. Anos se passaram com Krazer sob o comando do feiticeiro, e nada do que era pedido podia ser negado. O dragão era um escravo da vontade de um louco, ele era obrigado a fazer todo e qualquer tipo de serviço sujo, fora rebaixado a um simples serviçal, não tinha vontade própria, como um cão adestrado que faz todos os truques que seu mestre manda, e isso o afetou profundamente, como aquilo podia ser possível, ele era o mais poderoso de sua extinta espécie, uma das criaturas mais poderosas de Mera, ele era o senhor dos céus, a morte alada, o dono do fogo eterno, como um ser desses poderia ser subjugado por uma criaturinha tão frágil e mesquinha, que o usava para seus propósitos egoístas. Krazer estava decidido a reverter a situação, mas não encontrava uma solução, nunca tinha enfrentado um rival poderoso o bastante para acabar com sua vida e assim também com a de seu algoz. Krazer beirava a loucura quando de súbito decidiu o que deveria ser feito, não adiantava viver na eterna tortura de servir tal mestre ao mesmo tempo indigno e de tão baixa confiança e honra, não havia em Mera um oponente a sua altura, a não ser ele mesmo. Krazer saiu de sua caverna determinado a fazer o possível e o impossível para conseguir sua liberdade. Bateu suas asas o mais forte que pode, e continuou batendo mesmo quando a montanha em que vivia não passava de um pequeno ponto abaixo de si mesmo, e continuou batendo ate conseguir sentir o calor do sol em suas escamas negras, mas o calor não faria mal nenhum a ele, apenas o daria mais força, e ele não precisava de mais força, pois não aguentava mais a destruição. Ele queria fraqueza. É estranho pensar que uma criatura como essa desejava tanta fraqueza, para ser derrotado pela mais fraca das criaturas, e essa era a única coisa que ele não possuía, ele estava cansado. Cansado de ser um joguete na mão do feiticeiro, cansado de só destruir, cansado da solidão que é ser o único de sua espécie, e cansado da eterna culpa de ter acabado com toda sua raça. Cansado era realmente a palavra que o descrevia no momento em que Krazer decidiu apenas parar. Ele parou com o movimento constante de suas asas, parou com a única coisa que ainda sentia algum prazer em fazer, e nesse momento ele foi caindo, e o feiticeiro sentiu que algo estava errado, algo acontecia, ele sentia o que estava por vir, mas nada mais podia ser feito, o dragão vinha em velocidade em direção ao chão, e o feiticeiro apenas podia olhar, pois no desespero nenhum de seus truques veio a sua cabeça, nenhuma palavra que pudesse imobilizar a criatura no ar, que o fizesse bater suas asas novamente, nada. E nessa hora, ele percebeu o erro de ter atado sua vida ao dragão, o erro de não ter pensado o que estava fazendo, o erro que já havia feito. O chão chegava cada vez mais perto, a velocidade dele era cada vez maior, e havia apenas uma coisa que passava pela cabeça de Krazer: paz.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Oriental Garden Lizard (Calotes versicolor) ஓணான் #reptile #lizard #photography #nature #gardenlizard #garden #natureclicks #changablelizard #insectivore #agamidae #draconinae #beautiful (at Mettuppalaiyam)

#beautiful#reptile#gardenlizard#insectivore#garden#nature#photography#agamidae#draconinae#lizard#changablelizard#natureclicks

0 notes

Text

Flying dragons

Hoser, R. T. 2022. Twenty one new species and eleven new subspecies of Asian Flying Dragon Lizard (Squamata: Sauria: Agamidae: Draconinae: Draco). Australasian Journal of Herpetology ® Issue 60, published 16 August 2022 pages 1-64. https://www.smuggled.com/AJH-I60-Split.htm