#dolally tap

Text

THE ROAD TO DOLALLY

THE TRAIN TO DOLALLY

I assert ownership of this work

David Kitchen

April 14TH 2020

Doolally Tap

Origin and definition adapted from Collins English Dictionary

Slang: Out of one’s mind

In full: Doolally Tap

Word origin: C19. Original military slang from Deolali or Devlali, a town near Mumbai, the location of a military sanatorium and the Hindustani word for fever, tap.

A debt owed

Every fourth Sunday, more or less, for ten years. That’s how long it went on for. A four hundred mile round trip beginning after work on a Friday evening and completing back at home on Sunday around six. I was glad to do it. She had been the best of mothers and it was time to pay some of that care back but I am no angel and cannot say I was wholly selfless or always ungrudging…but it would have been unthinkable not to have made those journeys.

And that ten-year span took her from a badly rheumatic old lady, with much left of what had been a very good mind, all the way to a cot chair, carefully positioned pillows, a ghoulish expression and the ‘lostness’ which is the most shocking thing. You greave in stages when someone has dementia, and by the time it comes to an end in death you are relieved. Or at least I was. That decade had been an ever-growing aberration of what she was.

There were midway points, such as when at the care home some of her self could be retrieved by a Frank Sinatra song or a baby’s photograph, but once a month was not enough and careless carers could not be bothered to make the effort as evidenced by the dusty, cobwebbed corner where these things were kept for her. That time was not the before and after moment. It was earlier when she was still at home, in her own house. It was one specific weekend and I can remember it clearly. Everything changed after that.

Friday evening

I got there Friday evening at about half-past ten. All the lights in the house were on but mum was up in her bedroom. She shouted down “who’s that?”

I answered as always, “Just me mam”,

And she would come back again and say “who’s that?”

And this time I would say “Just me, Ryan”.

“Oh love I’m glad you’ve come. It’s a long drive for you, get something for yourself. There’s ham in the fridge”.

Indeed I was hungry, I’d had a McDonalds on the road but that was like nothing ten minutes after finishing it. I opened the fridge, and all by itself on the middle rack was a little plastic pack of boiled ham. Nothing like the meat we got sliced from the bone years before when I’d lived at home. I reached over but then withdrew with revulsion at the sight of a green-silver coat growing on the meat. The pack only had a couple of slices left. She must have eaten some that day. I did not want to look at the bread or think about her eating it.

My elder brother had remarked one time that leaving her after a visit had felt like leaving a toddler in the middle of a busy road. She paid for carers to call in four times a day to give her meds, help with simple meals and to get her washed and dressed. That was the theory but some of these angels of mercy skimped and rushed in and out doing the least of what they could do. I had witnessed this when they did not know I was sat in the corner. It left me sickened and angry. The only regular caring face was that of my youngest daughter who did mums shopping on a weekend and gave her time and love.

This home-care charade was a sordid carry on and my mother was fading through neglect. There was no way it could go on but she was refusing to go into a care home and was furious anytime the subject was broached, accusing me of trying to get the house and steal her money.

I felt this state as a great inertia. I could not go one way and she would not move the other and in the middle was this nightmare being played out. I had a job which paid barely enough to fund my situation: getting both daughters through university and doling out a sizeable monthly amount to my ex-wife and her lawyer. Something was going to have to give. If I moved back up north I would not earn two-thirds of my present wage and everything would come crashing down.

A month previously the police had phoned and said they had found my mother in the shop-door-way of a Toys “R” Us shop in the city at almost midnight. Seems she had set out to buy presents for her grandchildren and was found braying on the shop doorway and screaming at the empty place to be let in. It had only been a few weeks earlier that he Tetley’s Tea man had sold her a bedroom full of Easter Eggs and commemorative mugs. It was all going to pieces and there were disgraceful scoundrels around who were happy to prey upon her.

The house was getting a tatty look and the brown mark on that cushion might be shit. It felt much like sleeping over in a house without an occupant, a place that did not belong to anybody. I would do a top to bottom clean through that weekend and fix the garden up to an acceptable standard but nobody was really living here. Mum was just occupying the rooms. I got a half-drunk bottle of brandy out of the boot of my car and poured a full measure into a faded yellow Tupperware plastic beaker which my father had once kept his teeth in. There was only one proper cup left and that would be upstairs at her bedside. She liked to sip water during the night when she woke with a thirst.

I let the spirit do its work. Relax me after the drive, give me a dose of wellbeing and prepare for sleep. I texted my girlfriend and told her I’d got here and things were as awful as always and wished her goodnight.

I had to break this inertia and do something. It was like a free fall.

Saturday morning

The thin, scratchy, woollen army surplus blankets were still there on my childhood bed. Their feel was my first conscious perception of the day.

Quick wash at the sink then I walked to the Mace store on the estate and bought some breakfast supplies in. Got back to the house and made a tray of toast, orange juice and breakfast cereal but by then she was up and she had it at the table. I knew her mental facilities were at their best in the morning so settled on having the conversation I’d been stewing on right away.

“Mam, we need to have a talk about what needs to happen next. You’re getting frail and it’s time to go into a care home”. I am one of those people who cannot dress up a difficult conversation and if I was then she might have missed the point somewhere amongst all the fluff.

“What are you saying Ryan that I’m so old and decrepit that I cannot live in my own house anymore?”

There was a temptation to temper but decided against it-

“I need to talk to you honestly now mum, this is getting dangerous. There will be a fire or something and that will be the end of you”

“And I’d bet you’d like that, that sod of a brother of yours and you can’t wait to get your hands on this house and my money. Your bastards, the pair of you. Taking from your own mother. You ought to be ashamed and trying to dress it up as helping me. Well, how is stealing off me helping? That’s wicked.”

“I have got to be honest mam, this is probably one of the last times that we will be able to have a proper conversation. I’m not after your money or your bloody house or anything. I am only saying these things because you need taking care of.”

“Why do I need taking care of? Who do you think you’re talking to? I am not a child you can order about. So what is this big thing that’s wrong with me? Tell me that.”

My mind spliced for a moment and one half of it was thinking how well she had kept her verbosity when dementia was stripping everything else away at pace. She had been an English teacher maybe that gave her some kind of buffer: an extra resilience against the fleeing away of words I’d seen before.

I was pretty brutal. “Mam, you have dementia, you have coped well on your own since dad died but now we are at the point where you need care. I've got to start being honest with you”.

“How dare you say things like that? You bastard. You bloody bastard. Get out of my house. Sling your hook and don’t come back. I can manage perfectly well without people like you”. She was on her feet now and screaming the words.

I tell folk, and I am open about it. No one gets as angry as the grown-up children of a parent with dementia. Even though you know it’s not the ‘real them’ talking and saying things that sting and the not understanding on their part is not some spiteful refusal to understand. The rage was building up in me and so I moved across into the lounge which was one room with the dining room except there were sliding doors between them which I kept open. I sat in the threadbare high-backed chair facing across to where she was at the table six yards away. The curtains behind me were still drawn and the light was off so I was in the half-dark and I knew I would be effectively invisible in a minute or two. The best way of calming her was to become invisible and give her mind a chance to settle on something else. So I sat still and watched whilst she munched on her toast and looked straight ahead but not registering me.

We can never truly know where we will end up, and that was probably for the best. How would it be if we did see such an end approaching? All that life lived and encoded in the brain, stripped away and lost. She had been an exceptional woman whose life had taken her across the most extreme mental terrains and peaked in wonderful achievements, being given degrees, met prime ministers, won an elevated place in the memories of many hundreds of children but she was now someone trying to munch her toast sans teeth (they were always being lost) and so in danger of choking.

I thought it wise to get out in the garden for the morning and be yet more invisible. By lunch, it would be safe to come back in again. The memory of what had happened at breakfast would only last a few moments but the emotional weather in her head would linger.

There was a drizzle and in a normal situation I would have put the garden work off for another day, but now was the only option as tomorrow I would be heading back home. It was early spring so I gave the grass its first cut of the year, cut back on some overgrowth in the bushes and pushed bulbs into the ground. By 11.30 I was sodden to the skin and caked in slimy clay mud. I sneaked in the house and got a bath, went down to the high street, did her shopping and then got us fish and chips for lunch. That would shift her mood.

When I’d got back she had retrieved the ham and bread out of the bin and was chomping away on a rancid sandwich. One could not stop all these things but still, I felt like a thoughtless shit. Why had I not got the stuff out of the house? She accepted a few chips though and with a neat sleight of hand, I removed the remains of the sandwich. House cleaning was on my schedule for the afternoon but decided Sunday morning would do fine enough.

I know what happened to old people when they went into care homes. The progression downwards would accelerate, previously home and familiarity had been an anchor, but when inserted into the strange ‘out of placeness’ of a care home…well, that would cut her lose from life. Maybe in a year, she might be in one of those chairs with a swing across lap-table which incidentally restrain the occupant and stop them from wandering.Then sometime later there would be a cot like bed, pillows placed strategically around her, and there she would lay for months or years “in second childishness and mere oblivion.”

Saturday afternoon

She and I needed to get out somewhere nice for the afternoon. We settled on the choice of Ilkley Moor, just half an hour away in the car. I knew then and there, in all likelihood, this was the last time she would take pleasure in such ‘seeing of things’. Mum was happy at the prospect of an outing, the argument of the morning and its thundery mood all gone. We stopped at a tea hut in the car park of a spot known locally as The Cow and Calf, a great rock standing alone and splendid, yards from a towering rocky outcrop that had once reminded people of a cow with its calf, on the downside of an escarpment looking out over the town.

I helped my mother out of the car but her body had forgotten how to walk on sloping ground, so I brought the tea and cake to her in the car. She could not balance the paper plate on her knee or grip the plastic utensil so I passed the cake over on a plastic fork.

I took the car twenty yards forward so she could see out over the town and the Dales beyond. The drizzle had been pushed out by great swarms of windblown rain pellets coming in diagonally across the valley. The sun deflecting through every watery lens and making a wonderful show.

We stopped at a favourite baker under the old Temperance Hall on the way home and bought a few of her favourite things. Vanilla slices, ham off the bone, a small brown loaf and the special pork pies. Individual jellies and custard trifles. These had been our regular Friday treats, which it had been my task to pick up after walking from school over the Engine Fields.

Sat around the Formica topped table we were about to set about the Vanilla Slices when mum said. “Ryan, am I going Dolally Tap?”

I heard her but asked her to repeat it.

“I want to know off you Ryan if I’m going Dolally. Will you tell me”?

I thought about lying but just as quickly rejected it. There has to be a bloody good reason for not being truthful if someone asks you a question like that. “Yes, mum you have Dementia”, I hesitated and then decided to leave it at that.

Then she looked over and in her old way said “Oh bugger” and then carried on with her Vanilla slice.

I don’t know if it was the invigorating effect of going out or just the natural ebb and flow of her mental clarity, but I knew she understood what she was asking and what I said in reply. And it was back to what was typical of the old lass to accept my answer without fuss. I felt it very brave of her. Over the coming years, that moment stayed with me and became a kind of badge of what she was. By the next morning, it felt like the woman was already closing down. She either did not remember the conversation or chose not to speak about it.

Over the next weeks, I spoke to a Social Worker and arranged for my mum's admission to a dementia care home in Idle outside of Bradford, which in time let my mum down badly and all the things I expected happened even sooner than I imagined.

I’d got her there by saying we were going out for another ride but I think we both knew what I was doing. I won’t be hard on myself about that. I had to do what was necessary but I won’t dress it up as something it wasn’t.

More years went by till she reached the cot bed stage. A new care home took wonderful care of her and I cannot fault any of her time there. In all the fall into oblivion took ten years from first mistaking the radio for hearing voices in the wall to the last, very hurried but too late Friday evening drive up the A1.

The Road to Dolally

It’s always been my nature to quietly stew on things and then bring the stewing to a close with some gesture to myself. And then move onto the next thing. I don’t get to choose (at least consciously) what the full stop will consist of. It just sort of drops into my head then I feel released.

Two years after her death I woke up one morning and decided to go to Deolali in India and do ‘The Dolally Tap’. That needs two kinds of explaining.

Firstly, what is the Dolally Tap? When the British were in India they brought items of linguistic culture back home but did not spell them correctly. Deolali or Devlali was a permanent British Army of India camp about six (modern) train hours from Mumbai. It included a military hospital which treated soldiers evacuated in with dangerous fevers of one kind or another, which were as a group termed the Dolally Tap. Tap being Hindi for fever. Then the meaning of the words morphed with use by British army lads like my great-grandfather and came to be the words used to describe the act of going bonkers with the heat and boredom of the camp. The term evolved some more and became about mental illness, and by then the people who used it had no idea where it came from. Growing up in Yorkshire we learnt that there were two kinds of mental illness. Being balmy, equated to very odd and or even floridly eccentric behaviour, whilst Dolally Tap meant you were totally going off your head. It’s lovely how we used these words as commonly as we spoke about anything but never thought of whence they came.

So my mum, at the moment when she needed to ask about the fitness of her mind, opted for words she would have heard spoken, in childhood, by her grandfather. This was a woman who had gone all the way from mill hand, and cleaner to be an MSc in Education and a Head of English in a middle school, but when the time came she chose a homely word. I liked that a lot. It summed up the person she was. Some would have gone the full drama, or have hidden behind intellectualisation but she used the language of her home and where she started from. Her choice of words was a marriage of humour and dignity.

She liked to do things like that. Pass a binding rope between past and present, and the threatening and the funny. She did a lot of thinking about words and how they could best express something. At that breakfast table, she was asking if there was a cliff edge under her toes, and she would have certainly felt the fear of that potential fall but she chose a form which was so wonderfully brave.

So that’s why I went to Deolali/ Devlali. Of course, I added other experiences and visits to the trip: Delhi, New Year’s Eve midnight trains, Gandhi, Rajasthan, but at its core was the ride to, Deolali. I was making a statement of respect, remembrance and gratitude in my mind, and I hoped such actions would complete a necessary circuit and then I could go back home, and be content.

The odd pilgrimage started out from my little ramshackle hotel at 4 am. The man who manned the desk and all the other staff who worked in the small hotel were asleep across every surface in the reception area. The night clerk stirred himself and called a taxi that took me across town to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Railway Terminus. I walked the last few hundred yards from the drop off point but in the road as the pavement was carpeted with sleeping bodies including what looked like whole families with babies and small children.

India has ten types of first-class carriage but only one designated second class and the authorities take care to tell foreigners that the latter is not recommended. I took it anyway, in part because there was nothing else but also I could see orderly, comfortable trains at home. This was India and if one’s eyes are a school we have to look to learn.

As expected it was standing only in Second Class and we were crammed like matches in an overfull box but at the same time, we were also an incrementally creeping mass that (irresistibly) pushed me toward the door of the traditional squat toilet where I spent most of the six-hour ride. I did have another view out between the legs of a hostile looking youth who had wedged himself tight within the four angles of the open door of the carriage. And indeed I videoed the parched, red dusty hills from that perspective as young women sang and somehow danced to the tinkling tune of their finger cymbals further down the carriage.

I had once taken my mother on a rural bus journey in Swaziland, a small country in Southern Africa. We, the passengers, were similarly on top of each other for that journey. It was the intense, infringing, vivid, loud, brash and jarring unfamiliarity of our surroundings that was most upon her. I watched from sideways on as an old man with chickens and no teeth asked if she needed a husband and simultaneously a goat licked the space behind her knee and she shrieked a little and the lecherous suitor laughed well naturedly. She looked at me, grinned bravely and said she would never complain about the 55 Leeds bus again. That became our line about anything difficult from then onwards and I suspect it was the best bit of her slide presentation to her friends at the Wesleyan Methodist Ladies social. Her kidney stones had given her jip but she had conquered that bus journey and I suspect she would have done at least as well here on this train to Deolali.

I stood at the open door to the toilet all the way, averting my eyes from the scene: men crouching over a hole set in a circular, inwardly sloping floor, whose contents spilt out and washing around the floor. Six hours of holding myself still and facing resolutely away left me with a tortured back and feeling like I could never move with ease again.

It was a long train, and when we stopped my poor carriage was beyond where the platform finished. Most of my fellow passengers made off through the thick undergrowth towards a broken fence but I turned the other way and headed in the direction of the military checkpoint where a railway employee was checking the tickets and soldiers were watching out for likely terrorists. Nationally, tensions were up again about the dispute with Pakistan over Kashmir, and there had been some dreadful killings in recent weeks. As a military base, nearby Deolali, the camp had to be a target, and the security at the station serving it was understandable

The soldiers waved me through. Eccentric Englishmen like me did not fit the profile of interest even if they were carrying an outsize rucksack on their back. Foolishly I had not considered the possibility of a military presence and it was not just on my platform. A machine gun was mounted within a nest of sandbags at the end of the next platform across and formed the third point of a triangle with a spot where I was standing.

I had to find a clear station platform sign displaying the true name of the town, stand beside it and do a brief and discreet tap dance. It was plane though that such a thing might be mistaken, by the many soldiers, for a nervy suicide bomber about to detonate himself, so I risked being splattered by a machine gun or shot through by a lone pot shot of a soldier’s rifle. But not ‘doing the dance’, after all this effort, was unthinkable. Of course in more normal circumstances, when we are about to do something which might appear odd, we explain ourselves first. “Sorry, pardon me, I know this is going to look odd so am just quickly forewarning you that I am about to do a tap dance in honour of my dead mother. Please do not mistake this for a suicide bomber attack”.

No that would not work. I walked to the very end of the platform hoping for inspiration. There was a trolley parked there stacked to waist height with brown, cardboard parcels. They would be sufficient to block the line of sight from the military checkpoint on my platform but would put me directly opposite the machine gun nest on Platform 2 which was just yards away across the first track. I needed something to block the view from there whilst I performed my dance beneath the sign next to the parcels. Then just like an apple might fall into your hand from out of a tree I heard the approach of a local train from my left. That was it, the timing would be crucial but it was probably a winner. Something which would legitimately block the view from platform 2 and allow me to perform my dance, if only from the waist down so the soldiers on my platform had no clue.

And that’s what I did. I pretended to be a tourist filming the arrival of a typically overcrowded Indian train, and when the train draws level with me I pointed the camera downward and recorded a film of my feet doing a little tap dance for around ten seconds. The upper half of my body mostly but not entirely still. The men crowded at the windows of the train and hanging out the door and are watching me. They wave, and laugh and cheer and call things out I cannot understand.

And that little dance in the shadow of a train in the station at Doelali closes my circuit. I can say “Bye Kath”, and now it’s all done and you are put to rest.

The author is very tall and local people kept asking to pose for photos with him

1 note

·

View note

Text

Near-Death and Other Travel Experiences The Dolally Tap 2016 Part B- Eleven kinds of First Class…and just one Second

What has happened?

I travel from Mumbai to Deolali Military Transit camp to see the place that gave the world the term Dolally Tap, and to perform a Dolally Tap Dance on the station platform without being shot by nervous soldiers with mounted machine guns

What happened next?

I walked up through parts of the old military camp to a disused Hindu Temple near the gates of the new camp and spent some time looking around although it was very overgrown and you have to be careful of wading through long grass in such places.

I then hailed down a motorbike rickshaw and headed for a place Called Nashik Road Junction where I would be able to get a good meal. The place was dark, apart from a range of pit fires where men were cooking over the flames. My Rheumatologist and I compare travel notes when I go for my appointments. A few weeks later he told me that he had also come back from India where he has stayed in a five-star hotel but the trip had been ruined by the most dreadful food poison. He had made the mistake of eating salads and fresh fruit. I told him next time eat only fried food as that process kills every last germ.

The meal was the best Indian food I have ever had…it made anything I had in England taste bland. I spent the rest of the afternoon just walking around what was something like a small town looking at things. I probably dozed for a while on a bench. That is usual. Small towns are just the right size when you want to learn as much about life in a country when you only have a few hours.

Around four I went to catch a train but found that my travel pass was not valid for this time of day on that route. My only option was to go second class which is the carriage at the back of the train without seats. As I have said Indian trains have a full eleven kinds of First Class but only one kind of Second Class and it's like stepping into another world. We were packed in shoulder to shoulder, face to face. My day pack was resented as that was space for half a body.

Small children were sleeping in the luggage racks above our heads. Despite the crowding men were squatting and brewing cha on primus stoves. The spicy tea was then passed from hand to hand and the money came back the same way. Young men fixed themselves in the open doorways by spreading their limbs four ways and wedging themselves in the frame. One posed a little when I took his photo. In between his legs and arms, I could see a little of the landscape hilly, arid and rutted by soil erosion. A few low thorn bushes. No trees. The soil was red (I have a thing about red soil). I have a video somewhere of that view through the young man's legs and arms.

A young girl of about fourteen had got on the carriage. She was dressed in gaudy clothes and had hand tiny cymbals attached to each of her fingers. She sang in a scratchy voice accompanying herself with the tinkling of the finger cymbals. She is singing in the background as I catch about a minutes worth of the landscape. She got off at the next station. Later older women got, similarly dressed. They went down the carriage and men whistle and called out remarks and laughed. They were prostitutes. It was unimaginable how they might do business.

At every station, more people got on. I hated every one of them. We were packed solid now. I put my hands upon my head as I could not bear the feeling of having them pinned at my side. Inch by inch there was a movement going on as the newcomers pushed to get space. In an irresistible way, I was being pushed toward a squalid little room with no door which was the toilet. It was bare of anything other than a floor which sloped toward a hole in the centre. I spent more than half the journey hanging tightly onto the door frame whilst a steady stream of men used the facility. The conditions were dreadful. It was a six-hour journey back into Mumbai in the most acute discomfort. Long delays at stations. Lots of shoving. Most people ignored this foreign idiot. A couple of younger men made conversation. Always on the same line. “What is it like in England?”.

My lasting impression of India is lots and lots of people in small spaces and a feeling of chaos. The train journey was a nightmare experience but others were not. Forget the idea of personal space though.

Tomorrow. Looking for Butch Cassidy in Patagonia

Photos- all pics mine

youtube

0 notes

Text

Stories that make our everyday language

Not more than two months ago we were introduced to Pechakucha. Microsoft Word’s dictionary underlines the word with red right now. It’s a Japanese word, a concept of quick presentations, sharing ideas in twenty slides and twenty seconds to each slide.

We at DY Works started with four Pechakuchas every Friday. We’d talk about movies that stayed with us, or the music that made us feel. We laughed on the clichés of kissing flowers or Shakti Kapoor that we miss in Bollywood today, and were dumbfounded with an image and sound experience that contrasted war photography and cuddly bunny pictures. It was only after a few weeks that I learnt the story from where Pechakucha originated – architects in Japan trying to crystalize their complex presentations into crisper and more understandable talks. The idea caught on and many cities, organizations host sessions with it. Pechakucha has now become an everyday word at DY Works.

Quite akin to how foreign words become a part of everyday language. English for instance, has borrowed from around the word over centuries. Philip Gooden, a British author has put it tastefully in his new book ‘May we borrow your language’, how English has stolen, snaffled, purloined, pilfered, appropriated and looted words from all across. While these very words, in essence, are thefts from Old English, Low German, Anglo Norman French, Old French, Late Latin and Hindustani. Languages evolve with trade, invasion and conquests, advancement in science – medicine and technology, ideological structure, beliefs and rituals – a way of life of a certain people from certain time and place.

Ketchup has its origins in Chinese – Cantonese dialect that meant tomato soup. And tamarind has traveled from India. Trade took imli to Persia who called it tamar-i-hind or the Indian Date from where it became Tamarind. Similarly Jaggery comes from Sanskrit sarkara taken by Portuguese as xagara or jagara and finally jaggery in English by the 16th century. Food is interesting fodder for linguists. The animal romping around on the street loses its English name to the imported one when prepared and served. With the Norman invasion of England in the 11th century, pig became pork on the table, cow – beef and lamb – mutton.

India has given shampoo to the world via the English. Through the Raj several words like juggernaut, nirvana, jungle, curry and bungalow were lifted off. Intriguing stories tell us why words originated from where they originated. Old English has doolally (or dolally tap) which meant insane or feeble minded. Lore has its origin from Deolali – a town in Maharashtra which served as a British military’s transit camp for troops to sail back to England. Soldiers would often fall ill to malaria (tap from the Sanskrit tapa for heat or fever). Doolally caught on as losing one’s mind due to illness and boredom. Haven’t you spot a happy brewed beer pub named Doolally across Mumbai?

Their two hundred years on Indian soil also gave to the British Army their long service medal’s name – Rooty Gong. It comes from the Bengali variation of roti – if someone survived a career on military rotis his endurance must be appreciated.

Language also takes roots in ideologies. Patriarchy’s offshoots are sexist words we use today. Hysteria means wildness or madness and its etymology is the Latin hystericus – of the womb. Not far away is lunacy (madness) or loony (silly). They come from lunar – of the moon. The moon cycle is entwined with the menstrual one. The monthly biology lends to the idea of menstruating women being mad – or lunacy as a word we’ve often used for madness. In the same breath is the word seminal (from the male fertility) that is readily used for anything that’s path-breaking or important. It equates ‘importance’ to the masculine pronoun ‘he’.

Rituals, customs and a daily way of life too have constructed our everyday language. Cats and dogs holed up in the thatched roofs of medieval English homes slipped off the straw when it rained, and so it rained cats and dogs. Or the (once in a) blue moon that shouts out for something that’s very infrequent is a mistaken name – blue slipped in for an Old English word belewe which means ‘to betray’ – Sighting of two full moons in a single month happens every two-three years, and this astrological occurrence meant an extra fasting during Lent, hence the betrayer moon.

To let your hair down at the end of an exhausting day, one must look at the way hair was pinned up in Medieval Paris – French noblewomen would spend hours on elaborate hairdos for a brief outing. Picture Marie Antoinette. That’s letting your hair down! While, buttering up someone comes from Indian rituals. The Hindi phrase makkhan lagana comes from the ritual of offering (in some cultures throwing) balls of clarified butter to (at) Gods’ idols seeking favour.

What we do today is what we’ll speak tomorrow. We’re building our language every day and our everyday language is built of forgotten stories, obsolete lifestyles, latent connotations and sly gendered / political statements.

Published at DY Works

#language#meaning#roots#evolution#stories#politics#English#colonization#Empire#culture#culture studies

1 note

·

View note

Text

Near-Death and Other Fun Time Travelling Experiences Mumbai and Deolali India 2015

You have a good (and interesting) time by avoiding the attractions and choosing someplace random instead. It’s the law of Serendipity. Things happen along the way which gives the best entertainment and make your time special. Taking a look at something on a small scale is often best.

I chose to go to Deolali which is the site of an Indian military transit camp. It was famous previously for the origin of the phrase “Going Dolally Tap.”, which is a term for madness which came out of the British Indian army slang in the colonial period. Dolally was how we British mispronounced Deolali. Soldiers brought the phrase back to Britain and for much of the 20th Century, it was everyday lingo (itself the illegitimate offspring of a Latin word) for mental illness.

That term, Going Dolally Tap was used a lot in our home. I have put that down to my maternal Grandfather who was enlisted in the British Indian Army at14-year as an alternative to the workhouse. They made him a bandsman. I have read scientific papers on the condition known as Dolally Tap. Suffers had a raging fever, hallucinated and paced around manically. Entirely being unable to stand still. They, in fact, had one of the jungle fevers which had “gone to the brain” and were treated in the military hospital at Deolali.

I never saw the worst side of Mumbai, but I did see the part next to the worst side and that was the only travel experience in my life which has truly upset me. Got under my skin. I wanted to get out of the city and go somewhere in rural India so I settled on Deolali because of that Dolally phrase. I settled on catching the first train of the day from the famous Victoria terminus as imagined the later ones would be packed to the ceiling. I got a cheap taxi ride part of the way but asked to be let out when I miscalculated the driver was ripping me off. So I ended up walking the last half a mile but was unable to use the pavement as these were carpeted with bodies. Whole families including toddlers and babies sleeping right there. I breakfasted on smoky tasting Samosas at the station and managed to get one of the eleven grades of first-class tickets. Mine was halfway down that list but it gave me a reserved seat in a carriage with upholstery on the seats.

My fellow passengers were very friendly and shared food plus told me when I had reached my destination. It would take up two paragraphs describing the three stages of buying an Indian train ticket, so I will skip that. There are 11 variations of first-class but only one-second class. I was to travel back at the busiest time of day in that way. Second class.

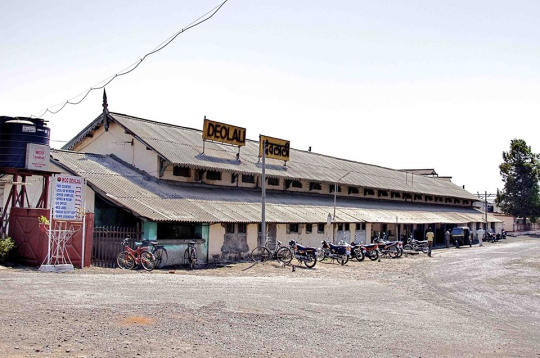

The station at Deolali was lovely. It must have changed barely at all since colonial times. It was all very photogenic but there was a problem. All across India, there were fears of terrorist incursions. There had been a massacre at a hotel in Mumbai where 178 people died. That was in 2008 but in changed attitudes to security across the country. As the station served a military camp, the place I was getting off would be a prime target for terrorists. Consequently, there was a military checkpoint and a machine gun nest with a good line of sight on every platform.

It was my plan to discreetly do a tap dance in memory of that phrase, Dolally Tap but I was concerned how it would look to the men with machine guns especially as I had a day pack on my back. I was determined though to go ahead with my little tap dance so when I told stories I could boast about it. I hit on a plan. I went to the very furthest end of the platform where I would be partially concealed by stacks of bags on trolleys and the station signs. To avoid being shot by the machine gunners on platform two 2. I waited until a train arrived at that platform to obscure their view of me on platform 1.I got to do my little tap dance (twice) and was cheered on by passengers hanging out the doors and windows of the train arriving at platform 2. Goal achieved.

Tomorrow

A train ride into Mumbai in 2nd class. Dancers with bells and clacking shell finger cymbals and women dressed in gaudy ways with excessive makeup.

Photos

The central railway station from which I travelled. My height fascinated many people. Families would ask to pose with me for photos

The station at the military transit camp

Central station in Mumbai

Cattle wandering through the street

Station platform

Posing with local people for a photograph

Poor quality video made by me on the backpacking trip to India

youtube

0 notes