#doctrinal and jurisprudence controls

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي - دراسة نظرية

المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي – دراسة نظرية المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي – دراسة نظرية المؤلف: عصام عمر مندور كلية التجارة جامعة كفر الشيخ المستخلص: هدفت الدراسة الى التعرف على ضوابط الاستثمار الإسلامي بشكل عام وتحديد ما هو أخلاقي منها وما هو غير ذلك، ثم محاولة استنباط المقاصد الاخلاقية والاجتماعية من الضوابط غير…

View On WordPress

#doctrinal and jurisprudence controls#ethical controls#investment#investment controls#Islamic economics#monopoly#Positive economics#الاقتصاد الإسلامي؛ الاقتصاد الوضعي ؛ ضوابط الاستثمار ؛ المقاصد الاخلاقية والاجتماعية ضوابط عقدية وضوابط فقه

0 notes

Text

المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي - دراسة نظرية

المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي – دراسة نظرية المقاصد الأخلاقية والإجتماعية لضوابط الاستثمار في الاقتصاد الإسلامي – دراسة نظرية المؤلف: عصام عمر مندور كلية التجارة جامعة كفر الشيخ المستخلص: هدفت الدراسة الى التعرف على ضوابط الاستثمار الإسلامي بشكل عام وتحديد ما هو أخلاقي منها وما هو غير ذلك، ثم محاولة استنباط المقاصد الاخلاقية والاجتماعية من الضوابط غير…

View On WordPress

#doctrinal and jurisprudence controls#ethical controls#investment#investment controls#Islamic economics#monopoly#Positive economics#الاقتصاد الإسلامي؛ الاقتصاد الوضعي ؛ ضوابط الاستثمار ؛ المقاصد الاخلاقية والاجتماعية ضوابط عقدية وضوابط فقه

0 notes

Text

Vaccines: The Unsung Heroes of Modern Medicine

In the grand pantheon of medical triumphs, vaccines stand as the unparalleled epitome of human ingenuity and triumph over nature’s capricious whims. Vaccines are the linchpins of public health, their efficacy and safety underscored by an avalanche of incontrovertible data, yet their importance is often obfuscated by a cacophony of misinformation.

Vaccines have achieved a monumental feat: the near-eradication of diseases that once ravaged populations with impunity. Polio, that malevolent specter of paralysis, has been reduced to a ghostly whisper thanks to widespread immunization. The triumph over smallpox, once a scourge of biblical proportions, is a testament to the unassailable power of vaccination. The statistics are unequivocal: vaccines prevent an estimated 2 to 3 million deaths annually worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. This is not hyperbole; this is empirical reality.

Contrary to the alarmist rhetoric perpetuated by the misinformed, adverse reactions to vaccines are astonishingly rare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that serious allergic reactions occur in approximately one per million doses. To juxtapose this with the morbidity and mortality rates of vaccine-preventable diseases is to lay bare the absurdity of the anti-vaccine diatribe. The infinitesimal risk of adverse reactions pales in comparison to the devastating consequences of unchecked infectious diseases.

In the realm of jurisprudence, the mandate of vaccination is not merely a matter of public health; it is a legal imperative grounded in the doctrine of parens patriae. The state has an incontrovertible obligation to protect the welfare of its citizens, particularly those who are most vulnerable. Compulsory vaccination laws have withstood judicial scrutiny, their constitutionality upheld in landmark cases such as Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905). This jurisprudential precedent underscores the principle that individual liberties do not encompass the right to jeopardize public health.

In conclusion, vaccines are not merely a medical marvel; they are the bulwark against the resurgence of pernicious pathogens. The statistical evidence is irrefutable, the legal framework robust, and the ethical imperative clear. To eschew vaccination is not an exercise in personal autonomy but an abdication of social responsibility, a perilous flirtation with epidemiological disaster. Let us, therefore, extol the virtues of vaccines with the fervor they so richly deserve, recognizing them as the silent sentinels safeguarding our collective well-being.

#jurisprudence#science#disease#immunity#vaccine#bacteria#virus#pathogens#climate change#scientific-method#reality#facts#evidence#research#study#knowledge#wisdom#truth#honesty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the Supreme Court Lying When It Purports To Place Limits on its Extreme Rulings? Third Circuit: Obviously, Yes

Today, the Third Circuit sitting en banc in Range v. Attorney General invalidated federal prohibitions on possession of firearms by convicted felons, at least in cases of non-violent offenders (Range had been convicted of food stamp fraud), but potentially in many other circumstances as well (via). This creates a circuit split with the Eighth Circuit's opinion last week in United States v. Jackson that I discussed here.

The issue of felon disarmament under Bruen is interesting. At one level, it's always possible that any gun regulation might fall prey to Bruen's rigid history-or-bust methodology for determining constitutionality under the Second Amendment (though much here depends on necessarily subjective judgment regarding what counts as a proper historical analogy). But at another level, the felon prohibitions are distinct because Bruen (along with the other members of the Roberts trilogy on guns -- Heller and McDonald) were emphatic that these prohibitions should not be questioned under the Court's rulings. As Heller said: "The Court's opinion should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons." This was reiterated in McDonald, and confirmed again in Justice Kavanaugh's Bruen concurrence.

How does the Third Circuit get around this seemingly very explicit language? By suggesting the Court cannot be trusted to mean what it says.

The court in an opinion by Judge Hardiman analogized adhering to the Supreme Court's express declaration that these laws remained constitutional to how the Court talked about the application of means-end scrutiny in Heller. Heller suggested that the law in question in that case would be unconstitutional “[u]nder any of the standards of scrutiny that we have applied to enumerated constitutional rights.” Lower courts, Judge Hardiman continued, universally "overread that passing comment to require a two-step approach in Second Amendment cases, utilizing means-end scrutiny at the second step," an approach the Supreme Court ended up disavowing in Bruen. And so the Third Circuit says, in essence, it won't make the same mistake twice: it must be "careful not to overread" the language suggesting felon disarmament laws remain constitutional "as we and other circuits did with Heller’s statement that the District of Columbia firearm law would fail under any form of scrutiny."

In other words, the basic question is: can we trust the Supreme Court when it says, expressly, "our decisions should not be read to mean felon disarmament laws are unconstitutional"? Or was that a promise the Supreme Court never meant to keep? In fairness to the Third Circuit, given the choice between predicting (a) the Supreme Court will abide by its own expressly-stated doctrinal limits or (b) the Supreme Court will completely ignore its own promises the instant they seem to sanction gun control limits the Court dislikes, I'm hard-pressed to say that option b isn't the safer bet. But there is something discomforting about lower courts openly acknowledging that the best way to interpret the Supreme Court's Second Amendment jurisprudence is to assume that any limits the high court purported to place on Bruen's sweeping protections for guns everywhere-for-everyone-at-any-time are probably just lies.

As a sidenote, I'll also just say that I literally finished compiling my Con Law II course materials on the post-Bruen Second Amendment last night, and immediately had to revise them again to account for the Range decision. Again, spare a thought for the underappreciated constitutional law professor, the forgotten victims of the churn and chaos the Supreme Court has unleashed in our constitutional jurisprudence.

via The Debate Link https://ift.tt/JNaKwdE

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article 1180. When the debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit him to do so, the obligation shall be deemed to be one with a period, subject to the provisions of article 1197. (n)

CASE DIGEST: Yamamoto vs. Nishino Leather I G.R. No. 150283 | April 16, 2008 | CARPIO MORALES, J.

FACTS:

The wrongful or unfair act in violation of a plaintiff's legal rights, as well as the distinct juridical personality of a business, must be convincingly demonstrated. Furthermore, a simple offer results in no obligation absent accep ance. Ikuo Nishino and Ryuichi Yamamoto decided to form a joint venture in which Nishino would purchase shares of stock equal to 70% of the company's authorized capital stock. But Nishino and Yoshinobu Nishino, his brother, ended up owning more than 70 percent of the authorized capital stock. Negotiations then took place in light of Nishino's intended takeover, which involved buying out Yamamoto's stock shares. Yamamoto was informed in writing that he could keep all of the equipment and machinery he had contributed to the business (for his own use and sale), as long as the value of those machines was subtracted from the capital contributions that he would receive. That being said, the letter asked that he provide his "comments on all the above, as soon as possible." Yamamoto tried to retrieve the machinery based on the aforementioned letter, but Nishino prevented him from doing so, prompting him to file a Writ of Replevin. The writ was issued by the Trial Court. On appeal, Nishino asserted that the corporation was the rightful owner of the properties being retrieved and that the aforementioned letter was only a proposal that had not yet received board approval. Yamamoto claimed that the corporation is only a tool of the Nishinos, but the Court of Appeals overturned the trial court's ruling.

ISSUE:

Whether or not machineries remained part of the capital property of the corporation

RULING:

Indeed. The defendant's use of control to commit fraud or other wrongdoing, to continue breaking a statute or other positive legal duty, or to engage in dishonest and unjust behavior in violation of the plaintiff's legal rights, is one of the factors determining the applicability of the doctrine of piercing the veil of corporate fiction. In order to overlook a corporation's distinct juridical identity, the unlawful or unjust act that violates a plaintiff's legal rights must be amply demonstrated; it cannot be assumed. It is not applicable until there is evidence that any of the ills that the concept aims to avert exist. The act of making a promise may result in estoppel. It is important to remember, too, that the letter was followed with a request for Yamamoto to provide his "comments on all the above, soonest." In other words, what was put forth to Yamamoto was an offer, contingent upon his acceptance, rather than a commitment. A simple offer results in no obligation if it is not accepted. As a result, Yamamoto's investment in machinery and equipment continued to be included in the corporation's capital.

Source:

Obligations and Contracts (2022); Atty. Ronaldo F. Flores | Central Book

0 notes

Text

Marbury v. Madison: Shaping the Foundations of Judicial Review and its Enduring Impact on American Governance

By Maya Mehta, Seattle University Class of 2025

November 29, 2023

The crucial Marbury v. Madison Supreme Court ruling, rendered in 1803, laid the groundwork for the judicial review doctrine and profoundly altered the nature of American governance. Chief Justice John Marshall's ruling in this case established the Court's authority to interpret the Constitution and deem acts of Congress unlawful. The tenets of Marbury v. Madison remain relevant almost two centuries later, influencing legal interpretation, the distribution of power among the organs of government, and the foundation of the US constitutional structure.

Historical Context:

It is crucial to examine the historical setting in which Marbury v. Madison originated to comprehend the case’s significance today. With the election of 1800, sometimes called the ‘Revolution of 1800’, the Democratic-Republicans gained political control over the Federalists. The Judiciary Act of 1801, which aimed to ensure Federalist dominance in the judiciary and expand the number of federal judgeships, was approved by the Federalist-controlled Congress in the final days of John Adams's administration.

In his haste to name these justices before to the inauguration of the Jefferson administration, Adams commissioned many ‘midnight judges’, among them William Marbury. After failing to get his commission, Marbury filed a writ of mandamus with the Supreme Court, directing Secretary of State James Madison to produce the document.

Establishing Judicial Review:

Supreme Court of the United States Justice Marshall upheld the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction to examine and interpret the Constitution. Despite rejecting Marbury on procedural grounds, Marshall clarified an important idea: the authority of judicial review. He said that it was the Court’s responsibility to decide whether laws were constitutional and, if not, to overturn those that did not comply with the Constitution.

With this historic declaration, the Supreme Court for the first time asserted its authority over judicial review, reshaping the check and balance mechanism among the three branches of government. The ongoing strength and stability of the American constitutional system may be attributed to Marshal’s ruling, which established the judiciary as an equal participant in interpreting and maintaining the Constitution.

Impact on Checks and Balances:

By strengthening the judiciary’s function as a check on the legislative and executive branches, Marbury v. Madison established the principle of checks and balances. The ruling gave the Court a way to protect constitutional values and stop any abuses of authority by the other arms of government. This fine balance is still very important in today’s political environment since the Court is still a major factor in deciding whether legislation and executive acts are constitutional.

The Supreme Court has used its judicial review authority to protect individual rights, maintain the separation of powers, and guarantee that government acts are faithful to the Constitution on several occasions because of this case. A range of legal and political circumstances find resonance with the concepts articulated in Marbury v. Madison, from historic civil rights decisions to discussions around presidential authority.

Legal Interpretation and Precedent:

The case of Marbury v. Madison established the legal theory of stare decisis or following precedent. The Court’s declaration of its judicial review authority served as a fulcrum for other rulings, influencing the development of American jurisprudence. Consequently, the ruling established a precedent for the Constitution as interpreted by the Court and the nullification of laws that were in violation with its provisions.

In the modern day, the Supreme Court's decision-making is still guided by the stare decisis doctrine. Because judges usually cite Marbury v. Madison as a seminal judgment when assessing the legitimacy of legislation or presidential acts, the judicial system is more stable and predictable.

Impact on Contemporary Issues:

The ideas upheld in Marbury v. Madison are still relevant in discussions and legal disputes today. The Court is often called upon to address fundamental questions like legality, the protection of individual rights, the extent of presidential power, and whether a particular statute is consistent with the Constitution.

Marbury v. Madison established a precedent that is often referenced in situations pertaining to issues of federalism, the extent of presidential directives, and striking a balance between civil liberties and national security. The case continues to be a benchmark for conversations about the boundaries of governmental power and the judiciary’s function in upholding the constitution.

Critiques and Challenges:

Although Marbury v. Madison is largely credited with creating the judiciary’s judicial review authority, there have been some who disagree with the ruling. Some contend that the ruling gave the courts excessive authority and gave elected representatives’ choices the ability to be overturned by unelected judges. The continuous conflict between democratic government and judicial review highlights how complicated and dynamic American constitutional interpretation is.

Critics often highlight the possibility of judicial activism, in which the Court interprets the Constitution in a way that supports the justices’ political or personal views, going beyond its constitutional authority. In today’s legal and political discourse, there is ongoing discussion and controversy about the right function of the judiciary within the constitutional framework.

Conclusion:

A cornerstone pillar supporting the structure of American constitutional law is Marbury v. Madison. The Supreme Court’s continued work demonstrates its lasting influence on the checks and balances, the division of powers, and the judiciary’s role in interpreting the Constitution. The ideas expressed in this historic case continue to direct and develop the American system of government, reinforcing the judiciary’s vital role in upholding the constitutional order as the country struggles with changing legal and political issues.

______________________________________________________________

Fawbush, Joseph. “Marbury v. Madison Case Summary: What You Need to Know.” Findlaw, 19 May 2020, supreme.findlaw.com/supreme-court-insights/marbury-v--madison-case-summary--what-you-need-to-know.html. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

“Marbury v. Madison | Background, Summary, & Significance | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023, www.britannica.com/event/Marbury-v-Madison. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

“Marbury v. Madison (1803).” National Archives, 28 May 2021, www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/marbury-v-madison. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

“Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).” Justia Law, 2023, supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/5/137/. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

“The Supreme Court . The Court and Democracy . Landmark Cases . Marbury v. Madison (1803) | PBS.” Thirteen.org, 2023, www.thirteen.org/wnet/supremecourt/democracy/landmark_marbury.html. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

“WILLIAM MARBURY v. JAMES MADISON, Secretary of State of the United States.” LII / Legal Information Institute, 2023, www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/5/137. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

0 notes

Text

Heyyyyyy, I bet you were DYING to know stuff about that Google v. Oracle decision, huh?

You may have heard recently about a big deal Supreme Court decision called Google v. Oracle, a litigation that has dragged on for many, many, many years and focuses on Google having copied some pieces of computer programming owned by Oracle and known as APIs. Most of the write-ups I’ve seen about it have focused on its enormous repercussions for the technology sector, which makes sense since it’s a case about computer programming and APIs and other tech-y things.

But the thing about the decision is that it’s a fair use decision. The Supreme Court could have found that the APIs weren’t even protected by copyright. But instead, the Supreme Court used the doctrine of fair use, and this means that the case potentially has ramifications for all fair use situations, including fanfiction!

So, if you don’t know, fair use is a main defense to copyright infringement. Basically, you can use somebody else’s copyrighted work without their permission as long as what you’re doing with it is considered a “fair use.” E.g., you can write a story in somebody else’s fictional universe or draw art of somebody else’s fictional copyrighted characters without their permission as long as your use is a “fair use.”

“What’s a fair use?” is an incredibly complicated question. The long and tortured history of Google v. Oracle illustrates this: a jury found Google’s use was a fair use; an appellate court found that it wasn’t and basically said the jury was wrong; and now the Supreme Court says no, no, the jury was right and the appellate court was wrong. Like, this is not unusual, fair case rulings are historically full of disagreements over the same set of facts. All of the cases reiterate over and over that it’s a question that can’t really be simplified: every fair use depends on the particular circumstances of that use. So, in a way, Google v. Oracle, like every fair use case, is a very specific story about a very specific situation where Google used very specific APIs in a very specific way.

However, while every fair use case is always its own special thing, they all always debate the same four fair use factors (these are written into the law itself as being the bare minimum of what should be considered), and especially what’s known as the first and fourth factors. The first factor is formally “the purpose and character of the alleged fair use,” although over the decades of fair use jurisprudence this has come to be shorthanded as “transformativeness,” and the fourth factor is “effect on the market.”

Most of the energy and verve of a fair use case is usually in the transformativeness analysis; the more transformative your use is, the more likely it is to be fair (this is why AO3’s parent organization is called the Organization for *Transformative* Works – “transformative” is a term of art in copyright law). To “transform” a work, btw, for purposes of copyright fair use doesn’t necessarily mean that you have edited the work somehow; you can copy a work verbatim and still be found transformative if you have added some new commentary to it by placing it in a new context (Google Image Search thumbnails, while being exact reproductions of the image in question, have been found to be fair use because they’re recontextualizing the images for the different purpose of search results). The point is, transformativeness is, like fair use itself, built to be flexible.

Why? Because the purpose of copyright is to promote creativity, and sometimes we promote creativity by giving people a copyright, but sometimes giving someone a copyright that would block someone else’s use is the opposite of promoting creativity; that’s why we need fair use, for THAT, for when letting the copyright holder block the use would cause more harm to the general creative progress than good. Google v. Oracle recommits U.S. copyright to the idea that all this is not about protecting the profits of the copyright monopolist; we need to make sure that copyright functions to keep our society full of as much creativity as possible. Google copied Oracle’s APIs to make new things: create new products, better smartphones, a platform for other programmers to jump in and give us even more new functionality. The APIs themselves were created used preexisting stuff in the first place, so it’s not like anyone was working in a vacuum with a wholly original work. And, in fact, executives had thought that, the more people they could get using the programming, the better off they would be.

Which brings us to the fourth fair use factor, effect on the market (meaning the copyright holder’s market and ability to reap profits from the original work). There’s a lot of tech stuff going on in this part of the opinion but one of the points I find interesting from that discussion is that the court thought that Google’s use of the APIs was not a market substitute for the original programming, meaning that Google used the APIs “on very different devices,” an entirely new mobile platform that was “a very different type of product.”

But also. What I find most interesting in this part is the court’s explicit acknowledgment that sometimes things are good because they are superior, and sometimes things are good because people “are just used to it. They have already learned how to work with it.” Now, this obviously has special resonance in the tech industry (is your smartphone good because it’s the best it could be, or because you’re just really used to the way it’s set up?), but there’s also something interesting being said here about how not all of the value of a copyrighted work belongs *to the copyright holder* but comes *from consumers.* Forgive the long quote but I think the Court’s words are important here:

“This source of Android’s profitability has much to do with third parties’ (say, programmers’) investment in Sun Java programs. It has correspondingly less to do with Sun’s investment in creating the Sun Java API. . . . [G]iven programmers’ investment in learning the Sun Java API, to allow enforcement of Oracle’s copyright here would risk harm to the public. . . . [A]llowing enforcement here would make of the Sun Java API’s declaring code a lock limiting the future creativity of new programs. Oracle alone would hold the key. The result could well prove highly profitable to Oracle . . . . But those profits could well flow from creative improvements, new applications, and new uses developed by users who have learned to work with that interface. To that extent, the lock would interfere with, not further, copyright’s basic creativity objectives.”

This is picking up on reasoning in some older computer cases (like Lotus v. Borland, a First Circuit case from decades ago), but I think it’s so important we got this in a Supreme Court case: if WE bring some value to the copyrighted work through our investment in it, why should the copyright holder get to collect ALL the rewards by locking up further creativity involving that work? Which, incidentally, the Court explicitly notes is to the public detriment because more creativity is good for the public? This is such an important idea to the Supreme Court’s reasoning here that it’s the first part of the fair use test that it decides: that the value of the work at issue here “in significant part derives from the value that those who do not hold copyrights . . . invest of their own time and effort . . . .”

This case is, as we say in the law, distinguishable from fanfiction and fanart. APIs are different from television shows, and this case is very much a decision about technology and computer programming and smartphones and how old law gets applied to new things. Like, fair use is an old doctrine dating from the early nineteenth-century, and here we are figuring out how to apply it to the Android mobile phone platform. That, in and of itself, is pretty cool, and it’s rightly what most of the articles you’ll see out there about this case are focusing on.

But this case isn’t just a technology case; it’s also a fair use case that places itself in the lineage of all the fair use cases we look at when we think about what makes a use fair. And, to that end, this has some interesting things to say, about how much value consumers bring to copyrighted works and where a copyright holder’s rights might have to acknowledge that; about the fact that there are in fact limits to how much a copyright holder can control when it comes to holding the “lock” to future creativity building on what came before; about what part of the market a copyright holder is entitled to and what it isn’t. Think about the analogy you could make here: Given the investment of fans in learning canon, which is what makes the creative work valuable in the first place, allowing enforcement against fanfic or fanart would allow the canon creators to have a lock limiting future creativity, which would be highly profitable to the original creator (or, let’s be real, to Disney lol), but wouldn’t further copyright’s goals of promoting creativity because it would stifle all of that creativity instead. And just like Google with the APIs, what fandom is doing is not a market substitute for the original work: they’re “very different products.”

This is not to say, like, ANYTHING GOES NOW. Like I said, fanfic and fanart are very different from APIs. Fictional works get more protection than a functional work like the APIs at issue in this case. And there’s still a whole thing about commercial vs. non-commercial in fair use analysis which I didn’t really touch here (but which obviously has limits, since it’s not like Google isn’t making tons of money, and their use was a fair use). But this decision could kind of remind a big media world that maybe had forgotten that the copyright monopoly they enjoy is supposed to have the point of encouraging creativity; we grant a copyright because we think people won’t create without a financial incentive. (Tbh, there’s a lot of doubt that that is actually a true thing to believe, given all the free fic and art that gets produced daily, but anyway, it’s what the law decided several centuries ago before the internet was a thing.) Copyright is a balance, between those who hold the copyright and the rest of us, and the rest of us aren’t just passive consumers, we have creative powers of our own, and we might also want to do some cool things. And this case sees that. None of us are starting in a creative vacuum, after all; we’re all in this playground together.

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

America’s “Interfaith” Outreach is Controlled by Jihadis

by John D. Guandolo

Have you wondered why so many American pastors say things about Islam which are objectively untrue or say nothing at all despite the fact Christians are being slaughtered around the world by muslims?

Like everything else we are experiencing these days, control of the narrative by muslims with regards to the understanding of Islam among Christian leaders and organizations is the intentional outcome of a long-term and well-coordinated effort by enemies of Jesus Christ.

In many cases, it is Christian Pastors letting the wolf in the door.

To set a few benchmarks down, lets compare the understanding of Jesus of Nazareth as taught in Christian and Islamic doctrine.

Christian doctrine teaches Jesus is the Son of God who is fully divine, and fully human, and is the Savior of the World. The Nicene Creed, the statement of faith for Christians accepted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, states, in part:

“I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he suffered death and was buried, and rose again on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures. He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end.”

Holy Scripture records Jesus himself said, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” (John 14:6)

In Islam, Jesus, like Adam, Noah, Abraham, and others, is a muslim prophet. Islam teaches – in the most authoritative hadith – that at the end of days Jesus will descend from heaven to kill all Jews and cast all Christians into hell for not converting to Islam.

Logic 101 teaches us an apple is an apple, and can only ever be an apple, never an orange.

Therefore, Christian pastors and Jewish rabbis who say “We all believe in the same God” are objectively wrong and can never be right.

The stated purpose of Islam, which is taught to eleven (11) year old children in U.S. Islamic schools as well as at the highest schools of Islamic jurisprudence, is to wage war against non-muslims until “Allah’s divine law”/sharia is imposed on all people on earth.

Are your pastors/rabbis teaching this? If not, why not?

How did pastors and rabbis become so clueless? One reason is that the U.S. Muslim Brotherhood owns the U.S. Interfaith Outreach movement.

The strategic center for the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), the International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT) is also at the center of Interfaith Outreach, and IIIT published Interfaith Outreach: A Guide for Muslims. In this publication the authors write, “We thank ISNA, especially Dr. Sayyid M. Syeed and Dr. Louay Safi, and that International Institute for Islamic Thought (IIIT) for their professional and moral support.”

ISNA (Islamic Society of North America) is identified by the Department of Justice as a Muslim Brotherhood organization which funds the designated Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) Hamas.

See UTT’s Statement of Facts which details the above fact and many others about the U.S. Muslim Brotherhood.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s publication, Methodology of Dawah, makes clear their devious use of Interfaith Outreach:

“The IMOA (Islamic Movement of America) will open dialogues with dignitaries of the religious institutions, presenting Islam as the common legacy of Judeo-Christian religions and as the only Guidance now available to mankind in its most perfect form for its Falah (Deliverance and Salvation). These talks must be held in a very friendly and non-aggressive atmosphere, as directed by Allah in the Quran as to how to talk with people of the scripture.”

As a reminder, Islamic Law (sharia) obliges muslims to lie to non-muslims when the goal is obligatory. Jihad is obligatory.

According to the Muslim Brotherhood, ISNA has the lead role for Interfaith Outreach, and the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR), a Hamas entity, has “social justice” and civil rights aspects of the this hostile effort.

A Jewish woman takes a photograph of (L-R) Mohamed Elsanousi (ISNA’s Director of Community Outreach & Interfaith Relations), Sayyid Syeed (ISNA’s National Director of Interfaith and Community Alliances), and Azhar Azeez (President of ISNA) at the Peres Peace Center in Jaffa, Israel in 2015

The purpose for all of the dialogue, outreach, interaction, and “togetherness” conducted by the Muslim Brotherhood is dissemination, intelligence collection, and control of the narrative. It has nothing to do with “Interfaith Outreach.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion analysis: Lawyers should lawyer, judges should judge – The court remands Sineneng-Smith

The Supreme Court today resolved United States v. Sineneng-Smith without reaching the merits of the underlying First Amendment question, instead holding that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit improperly injected the issue into the case. The court sent the case back for reconsideration based on the claims of the parties. Evelyn Sineneng-Smith had been convicted of violating 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(4), which prohibits “inducing or encouraging” unauthorized immigration. She charged noncitizen clients substantial fees for filing paperwork that she falsely claimed could lead to lawful permanent resident status. After her appeal had been briefed and argued in the 9th Circuit on more prosaic issues, the panel requested briefing on whether the statute was unconstitutionally overbroad, an issue Sineneng-Smith had not raised. The order for additional briefing was addressed not to the parties but to specified amici curiae, or “friends of the court,” although the parties and other amici could also elect to participate. The panel ordered re-argument in which the amici would have 20 minutes, and Sineneng-Smith only 10. The 9th Circuit ultimately reversed the conviction because it found that the statute was overbroad, the ground that the court’s re-argument order had brought into the case. In an opinion by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a unanimous Supreme Court held today that “the panel’s takeover of the appeal” warranted reversal and remand for reconsideration in light of “the case shaped by the parties.”

The court cited Greenlaw v. United States, another opinion by Ginsburg, as an example of the strength of the general principle that courts do not “sally forth each day looking for wrongs to right. They wait for cases to come to them, and when cases arise, courts normally decide only questions presented by the parties.” In Greenlaw, the Supreme Court held that on appeal of a criminal conviction and sentence by a defendant, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit had erred by ordering on its own initiative the correction of an illegally low sentence—the defendant had received 10 years, instead of the required 25. The error was substantial, in the record and crystal-clear, and it had even been mentioned in the government’s brief. However, in the absence of an actual appeal or cross-appeal by the United States, the court ruled that the court below should not have reached out to fix it.

Although the government noted that the 9th Circuit here had deviated from “the normal course of party-driven litigation,” the certiorari petition and the merits brief focused on the meaning and application of substantive law. There was no argument or citation of authority suggesting that the 9th Circuit’s actions, independent of the merits, warranted review or reversal. Similarly, the oral argument was entirely focused on the meaning of the law and its constitutionality, not the 9th Circuit’s unusual procedural approach. Therefore, it could be argued that the Supreme Court “reached out” to hold that the 9th Circuit improperly reached out to invalidate the statute at issue. Perhaps under its supervisory authority or on some other ground, the Supreme Court has more authority to reach out than do other courts. But it would have been useful for the court to explain why it was relying on a procedural problem that was not foregrounded in the Supreme Court litigation.

It may be that the court was looking for an exit. By this point, much of the drama has been drained from the case. Apparently, little is at stake for Sineneng-Smith herself; her convictions of several related mail-fraud offenses had been affirmed, so she will have a record in any event, and she is now out of custody. For the government’s part, it acknowledged before the Supreme Court that the statute at issue could not be applied to the full extent of its literal language. Due to seemingly contradictory positions taken below and in other cases, the government agreed, as the court put it, that the statute “should be construed to prohibit only speech facilitating or soliciting illegal activity, thus falling within the exception to the First Amendment for speech integral to criminal conduct.” With the Department of Justice agreeing that the statute had to be limited, yet with no question that much of the conduct covered by the law is constitutionally punishable, the precise scope of the law and its validity could be left for another case.

The impact of the decision on the role of courts is unclear. As Judge Stephen Williams once memorably wrote, “[w]hile a judge isn’t a pig hunting for truffles in the parties’ papers, neither is he a potted plant.” The Supreme Court did not disagree; Ginsburg noted that “[t]he party presentation principle is supple, not ironclad. There are no doubt circumstances in which a modest initiating role for a court is appropriate.” Surely judges have the right to control proceedings before them. Trial judges sometimes say “sustained” when no lawyer has objected but the judge perceives impropriety; Sineneng-Smith does not call that practice into question. Although what happened in this appeal is unusual, it is hardly uncommon for courts to order supplemental briefing based on an issue’s arising at oral argument. And judges have the ability to make things arise at oral argument. If, based on questions by the 9th Circuit panel, counsel for Sineneng-Smith had orally moved for additional briefing, and that motion had been granted, the legal issues before the 9th Circuit and Supreme Court would have been the same, but would have been “party-driven.” Unless the Supreme Court will police supplemental briefing orders, the reversible error here may have been one of form rather than substance, avoidable in future cases with more subtle but no less effective judicial actions.

The case is also interesting for the concurrence of Justice Clarence Thomas, who in addition to agreeing that the 9th Circuit had erred, expressed doubts about the validity of the overbreadth doctrine itself. Under the overbreadth doctrine, someone like Sineneng-Smith, who has engaged in conduct that clearly can be criminalized, may nevertheless defend herself on the theory that the statute is invalid. Thomas explained that under existing jurisprudence, “a law may be invalidated as overbroad if a substantial number of its applications are unconstitutional, judged in relation to the statute’s plainly legitimate sweep.” Thomas argued that this rule is not compelled by the First Amendment itself, and is in tension with other jurisprudence: “The overbreadth doctrine appears to be the handiwork of judges, based on the misguided notion that some constitutional rights demand preferential treatment. It seemingly lacks any basis in the text or history of the First Amendment, relaxes the traditional standard for facial challenges, and violates Article III principles regarding judicial power and standing. In an appropriate case, we should consider revisiting this doctrine.” No other justice joined this opinion.

The post Opinion analysis: Lawyers should lawyer, judges should judge – The court remands <em>Sineneng-Smith</em> appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

from Law https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/05/opinion-analysis-lawyers-should-lawyer-judges-should-judge-the-court-remands-sineneng-smith/ via http://www.rssmix.com/

1 note

·

View note

Link

“ ... I’m not a student of Kavanaugh’s jurisprudence in particular, but he’s uniformly recognized as a product of the Federalist Society’s multi-decade project to cultivate a set of conservative jurists, and he’s been one of the crown princes of that movement and network for a long time.

Things that might happen if he had the controlling vote on the court would include very solid entrenchment of the basically unlimited protection of money in politics as political speech, and possibly its expansion to protect things like unlimited direct donations to campaigns.

I would expect an extension of the use of the free speech doctrine generally as a deregulatory instrument, to bring down things like mandatory disclosure or restrictions on transfers of data, or in industries like banking where transparency may be a big part of regulation.

Generally, the First Amendment has turned into the same kind of free-roaming tool of judicial deregulation that the “freedom of contract” in the due process clause was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. That would likely keep happening.

So those are very big in terms of the balance of power between organized money, concentrated wealth on the one hand, and votes or other forms of social and political organization on the other. Following in that vein, you could potentially see an extension of the libertarian anti-union doctrine, the constitutionalization of the right-to-work doctrine that we saw in the Janus case extended in some fashion to non-public-sector unions.

You could see invalidation of any effort to deal with climate change that doesn’t come out of brand-new legislation. Trying to do climate change regulation on the strength of the Clean Air Act alone could easily fail.

And even if Roe v. Wade were not formally overturned, it seems likely that you would not see many abortion restrictions invalidated. Additionally, it might very well be that a colorblind theory of constitutional equality would knock out all race-conscious policies, like affirmative action at public universities — which would possibly by extension make it much harder to do in private universities.

So, those are some of the stakes off the bat. I would say also that any thought about a progressive use of the courts, to push back against voter suppression for instance, would be dead for a couple of decades barring unexpected contingencies.... “

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grim History

The Rise of Wahhabi Islam and the Conquest of the Arabian Peninsula

In the early years of the 18th century, the impoverished region of the central Arabian peninsula called the Najd was a veritable backwater. Dominated by the northern Arabian Rashid tribe with support from the Ottoman Empire, the Najdi people were suffering from poverty due to agricultural difficulties. The practice of Islam had faded away and given rise to superstitious rites and the worship of saints in its place. Violence, lawlessness, and constant raiding by Bedouin tribes were seemingly never-ending problems. Out of the chaos came a young student of Islamic law named Muhammed ibn Abd-al Wahhab who promised to alleviate their distress if they returned to the way of life set out by the first adherents to the Muslim religion. His teachings transformed the Arabian lands and set the course of the region on the path to fundamentalist militant Islam.

Born sometime in the first decade of the 1700’s, Abd al-Wahhab came from a family of judges. Raised in the Sunni Hanbali school of Muslim jurisprudence, he chose his devotion to the practice of law at an early age. After going on pilgrimage in Mecca and Medina, Adb-al Wahhab returned to his native village of Uyayna, convinced after what he saw there that Muslims had abandoned the true and pure form of Islam as it was originally planned out by the prophet Mohammad. He began preaching about the purification of Islamic teachings and soon began attracting adherents to his revivalist style of militancy and literalism. Male followers were made to wear a plain white thobe and turban on their heads rather than the traditional Bedouin iqal, the black rope used to hold their headscarves in place. Female disciples were commanded to dress with extreme modesty in the full black burqa covering all parts of their bodies except for their eyes.

Aside from the memorization of the Qur’an, the early Wahhabis believed that every aspect of their lives had to be done in strict obedience to Allah without any influence from anything else. Thus, praying to saints, a practice that had gained in popularity in those times, was strictly forbidden. Even the intervention of doctors in illnesses or injuries was banned because the patient in such situations did not seek out guidance from Allah instead. Women were to be highly regarded just as long as they married and did their wifely duties. Social interaction between members of the opposite sex was outlawed to prevent extra-marital affairs; this social taboo, if broken, was punishable by public whippings and beatings. Followers of Christianity, Judaism, or any other religion were regarded as sorcerers and agents of evil and Muslims who practiced or believed anything other than the Wahhabi cult’s doctrine were thought of as heretics and enemies of the true faith of Islam.

Muhammad ibn Abd-al Wahhab starting gaining notoriety when he and his followers set out on a campaign to clean up their society. They began their rampage by destroying a coffin containing the remains of a revered saint, said to have healing powers. The people of the Najd also had taken to worshiping sacred trees which they believed to have supernatural powers; Abd-al Wahhab and his followers cut these down. They also found a woman who had been known for speaking publicly about cheating on her husband; when they commanded that she repent, she reacted with defiance and claimed to be proud of her infidelity. Her punishment was that they buried her up to the neck in sand and threw rocks at her head until she died. Public beheadings were another common punishment for other transgressions. To top it all off, the Bani Khalid tribal chief Sulaiman ibn Muhammad ibn Ghurayr forced the Wahhabis to leave the eastern Najdi region because they declared taxation to be against the teachings of Islam, something that did not impress a chief whose main source of income was tax revenues.

Abd-al Wahhab moved on. Upon arriving at the town of Dhiriya, he was welcomed in and soon struck up a friendship with Muhammad ibn Saud, the grandfather of Abdul-aziz ibn Saud, the first king of the modern nation of Saudi Arabia. Muhammad ibn Saud was impressed by the strictly disciplined followers of Abd-al Wahhab and the two agreed that by combining the Wahhabi teachings with militant tribal politics, they could conquer the Arabian peninsula. After forming this alliance, they built up an army and seized the town of Riyadh. Whipped up into a frenzy of religious zeal, the Wahhab-Saud alliance’s army began raiding nearby tribes, forcing them to convert as they conquered each one. They marched on the eastern towns of Hasa and Qatif, down to the peninsula of Qatar, south to Oman and Yemen, then north to the Rashid fortress in Ha’il and the Shi’ite-dominated city of Karbala. All along the way they gave the conquered people the choice of peacefully converting to the Wahhabi creed or being slaughtered. They all chose to convert and the first Saudi emirate of Dhiriya was born.

Next they turned their attentions to the Hejaz, the western strip of the Arabian peninsula where the holy cities of Mecca and Medina were under the control of the Ottoman Empire. They seized these cities too and ruled them for years, refusing to allow any Muslims other than Sunni Wahhabis to perform the Hajj pilgrimage. But as time went on, the insular Wahhab-Saud alliance had no contact with the outside world. The Industrial Revolution produced new technologies for killing and new strategies for warfare and the Wahhabis, smug in their fanatical conceit, knew nothing of them. The Ottoman Empire built up a proxy army of Egyptian soldiers who marched on the Hejaz, decimating the Wahhabis and taking control, once again, of the cities of Mecca and Medina. Meanwhile, the Ottomans also supplied the Rashids with war materiel and assisted them when they attacked Riyadh, forcing the House of Saud to flee to Kuwait where they lived in exile until their return in the 20th century.

To this day, the Sauds have maintained their alliance with the Wahhabis who act as the official governing body of religious clerics in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Wahhabi doctrine not only acts as the founding principle of national and religious identity for Saudis but it also provides the belief system for fundamentalist terrorist groups like Al Qaeda and ISIS. Their goal of dominating the world through a radical, draconian interpretation of Islam is the modern ancestor of the fanatical teachings of Muhammad ibn Abd-al Wahhab.

Darlow, Michael and Bray, Barbara. Ibn Saud: The Desert Warrior Who Created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Skyhorse Publishing, 2012

#grim history#saudi arabia#muhammed ibn abd-al wahhab#wahhabis#muslim sects#islamic cults#middle eastern history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Coming Era of Forced Abortions

"We can't restore our civilization with somebody else's babies."

That is a direct, verbatim quote from a sitting member of Congress -- namely Representative Steve King (R-IA).

The "somebody else" King was referring to was immigrants -- specifically, brown immigrants from Latin America. Them and their children, for King, represent an existential threat to the American republic. And while King stands apart for the explicitness with which he indulges in racist rhetoric, he is not alone in the construction of immigrant births as threat. The term "anchor baby" -- used by Donald Trump, yes, but also Jeb Bush -- also presents it as illicit, even dangerous, when immigrants give birth inside the United States.

This is not a post about immigrants, exactly. It is a post about abortion. And particularly, it is a post about the possibility of government actors coercing or compelling women (particularly women under the custodial authority of the state) to have an abortion.

People scuff at this prospect -- less based on law than based on their own lack of imagination. Who in government might want mandatory abortions? Why, the pro-life movement wouldn't stand for it!

Which is why I bring up the view of Mr. King and his cohort. It is entirely plausible that King and his cohort could come to believe that it is permissible -- even a national security imperative -- that immigrant women not be allowed to birth their "anchor babies" on our shores. They already possess and wield the language that presents the prospects of such births as a wrong, even a threat. Do you really think him and his would really have a problem with someone forcibly terminating an immigrant mother's pregnancy? Do you really think they'd even struggle to justify it? The only question would be whether they'd politely avert their eyes or outright endorse the practice.

Everything about the contemporary state of right-wing politics suggests that this is not an idle fear. The average conservative hardly bats an eyelash if horrific conditions in ICE custody cause immigrant women to miscarry. Pro-life has never extended that far, after all -- it is a movement primarily about controlling women, not saving babies. Forcible births and forcible abortions are two sides of the same coin; the preference depends on the woman involved.

Or take it another step: Remember that infamous case where the Trump administration tried to prevent an undocumented immigrant teenager from procuring an abortion? Judge Kavanaugh's dissent assumed for sake of argument that the girl had an abortion right, but argued that the government could temporarily refuse to honor it if it could secure her an immigration sponsor with sufficient rapidity. But one Judge, Karen Henderson, went further -- in her opinion, undocumented immigrant minors exist in a lawless space, devoid of any rights over their own body at all by virtue of their illegal entry (Judge Kavanaugh, for his part, did not join that opinion). The logic of Henderson's dissent, at least, would apply equally if the government -- whipped into a hysteria that "demographics are destiny" (to use another Steve King-ism) -- sought to compel her to abort her child.

The thing is, Roe v. Wade does not protect, or does not solely protect, a woman's right to an abortion. It protects a woman's right to choose an abortion -- or not. And in a world without Roe, it isn't clear what judicial doctrine would render it unlawful for a government actor to compel or coerce a woman (particularly a woman under custodial authority of the state) to have an abortion.

Indeed, it's far from clear what legal principle absent Roe would or could give a woman -- again, especially women under the custodial authority of the state (which might include the incarcerated, immigrants, and some minors) -- a constitutional right to continue her pregnancy as against a state official claiming authority to compel her otherwise. Roe answers that women have a right to bodily autonomy which vests in them a private right to make reproductive decisions for themselves. Knock off Roe, eliminate the constitutional reproductive autonomy right, and it's replaced by ... what exactly?

I don't think there's an answer -- at least, not one that doesn't swing entirely in the other direction and say that abortion is constitutionally impermissible (which, of course, would remain blissfully apathetic regarding the rights of women in favor of waxing lyrical over the rights of blastulae). So imagine this: Roe is overturned. The issue of abortion is, as promised, "returned to the states". A few months later, a prison guard rapes an inmate and then, to cover up the crime, forces her to terminate the ensuing pregnancy. Is the latter act a constitutional violation? I don't know that it is. Is it a clearly established constitutional violation (thank you, qualified immunity)? I don't see how. The constitutional underpinnings that say women cannot be forced to involuntarily terminate their pregnancies rest entirely on Roe v. Wade -- if that's overturned, the best you can say about the state of that right is that it is up in the air.

It's well known by now that the end of Roe will fall hardest on the poorest, most marginalized, and most vulnerable women -- not surprisingly, the ones for whom "liberty" is barely given the pretense of acknowledgment whilst government authority is allowed near-boundless jurisdiction. But even this gives contemporary conservatism too much credit, as it suggests that ending abortion is the point. The fact that pro-life politics virtually never come tied to any sort of tangible commitment to expanding pre-natal care is a clue that the birthing isn't the key variable -- the control is. Sometimes you want to control women via compulsory motherhood, and sometimes ... you don't -- but "pro-life" isn't going to do any real work one way or the other. The tides of the contemporary right -- replete with White nationalist themes, anxious to the point of obsession about becoming a minority in "their" nation -- hardly are ones inclined to respect the rights of "someone else's babies."

Think I'm being hyperbolic? Answer me this: If reports emerged of ICE agents forcing immigrant women to abort their children, would Steve King utter a word against it? Would his "pro-life" instincts kick in? Or would he find that he's ... fine? Okay, even?

We know the answer. And the thing is, you don't have to think Steve King is the be-all end-all of modern conservatism to concede that he represents a real and growing portion of it -- a portion that no doubt has adherents amongst ICE enforcers, amongst authoritarian prison guards, amongst certain extreme (but less so everyday) pockets of fanatical racist and xenophobic authoritarians. If you don't think some among them aren't going to start endorsing "extraordinary measures" to ensure no babies get anchored, if you don't think some among them aren't going to turn to forced abortions as a means of covering up their own rape culture, you're deluding yourself.

And ultimately, that's all that's necessary, because we won't be talking about forced abortions as some sort of nationwide policy. We'd be talking about a patchwork of incidents and abuses and cover-ups and "oversights" that just so happen to fall upon the sort of women that the right doesn't care about in the first place. It will be so easy to ignore them, so easy to say they brought it on themselves, so easy to let the majestic lattice of qualified immunity and formalist textualism conclude that they have no remedy.

I think we'll see it. I really do (I know that if we do, the great bulk of the American conservative movement will not care one whit about it). It's not going the only part of a Roe-less future, but it will be a part. Because when your jurisprudence denies that pregnant women have the right to choice what happens to their own body and your politics grows ever more ravenously xenophobic and your acknowledgment that immigrants, the poor, and the incarcerated nonetheless have rights shrivels into nothingness -- the result of that cocktail isn't any mystery.

via The Debate Link https://ift.tt/2NDViWJ

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comment | September 27, 2021 Issue

The Supreme Court and the Future of Roe v. Wade

Abortion rights may hinge on a case involving a Mississippi law—and the errors of fact and judgment in the state’s brief are staggering.

— By Margaret Talbot | September 19, 2021 | The New Yorker

Illustration by João Fazenda

One of the more dubious assumptions undergirding the latest assault on reproductive rights in this country is the idea that abortion is a kind of niche procedure for which there isn’t much need, and for which there will be even less need in some unspecified future. Defending the new Texas law that bans abortion after about six weeks, making no exception for pregnancies that are the result of rape, Governor Greg Abbott explained that this restriction won’t be a problem, because he plans to “eliminate rape” in the state. In the next few months, the Supreme Court will consider the constitutionality of a Mississippi law that bars most abortions after fifteen weeks. That case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is widely viewed as an opportunity for the Justices, if they so choose, to overturn the nearly fifty-year-old precedent set by Roe v. Wade.

Mississippi’s brief to uphold its law offers, among other rationales, the assertion that women’s lives are so much freer, more equal, and more replete with birth-control options now than they were in 1973, when Roe legalized the right to abortion nationwide, that we can let that right go by the wayside. “Modern options regarding and views about childbearing have dulled concerns on which Roe rested,” state officials claim—namely, that unwanted pregnancies were hard on women and on their prospects in life. But the Mississippi brief says that everything is different now: laws addressing pregnancy discrimination and offering family leave “facilitate the ability of women to pursue both career success and a rich family life.” They add that, although “abortion may once have been thought critical as an alternative to contraception,” this is no longer the case, since birth control is more available and reliable.

The errors of fact and judgment in this patronizing argument are staggering. The United States, alone among industrialized nations, does not mandate paid family leave. The major advances in women’s access to careers and to the public sphere have occurred since the early nineteen-seventies, when abortion was legalized, and it’s quite likely that the two developments had something to do with each other. Furthermore, even in an egalitarian society with reliable access to contraception and to child care for all, people will still want, and should be able to exercise, agency over the intimate, life-transforming decisions of when, or whether, to have children. Many people will still feel a need to end pregnancies for reasons—health risks and crises, destructive or failed relationships, personal economic hardship, the needs of other children—that have little to do with prevailing social conditions.

It’s true that the most recent data show that rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion have declined since the early two-thousands, but both remain common. Nearly one in four women will have had an abortion by the time she is forty-five, according to an analysis by the Guttmacher Institute. The procedure that anti-abortion lawyers want to portray as an unnecessary and outmoded privilege (and a shameful one) is a form of medical care that hundreds of thousands of people turn to each year, low-income people in particular. (Half of all abortions are obtained by people living below the federal poverty line.) Not everybody can afford or obtain reliable birth control. And, despite Abbott’s absurd claim, there will always be people who become pregnant through coerced unprotected sex.

Consistently preventing pregnancy during the reproductive life span isn’t so easy, and that span has been getting longer. The lawyer and bioethics professor Katie Watson has estimated that a fertile woman who has sex with a man regularly throughout her reproductive years will have to dodge up to twenty-nine pregnancies if she wants to have just two children and avoid an abortion. That’s a lot of contraceptive efficacy to rely on. Moreover, plenty of evidence shows that restrictions on abortion do not end the practice. The need remains, and women find a way to meet it, though this sometimes requires ingenuity, along with legal and physical risk-taking. People in exigent circumstances shouldn’t have to contend with such challenges.

All these facts of life are important to acknowledge, because anti-abortion lawyers are intent on erasing them. Mississippi claims that no “legitimate reliance interests call for retaining Roe and Casey,” the 1992 Supreme Court ruling that upheld a constitutional right to abortion while allowing states to impose limits before the stage of fetal viability. The state also says that Justices needn’t worry about stare decisis—the principle that would encourage them to respect legal precedent—or about the impact on people’s lives if Roe is tossed out. Abortion-law jurisprudence, the petitioners write, has always been “fractured and unsettled,” and the “Court is not in a position to gauge” how reliant society is on abortion. But, as the lawyers representing the lead respondent—the only remaining abortion clinic in Mississippi—point out, the Court has heard multiple abortion cases since Roe and, while it has allowed states to chip away at the constitutional right to abortion, it has also clearly upheld the core finding.

The Court that will consider the Mississippi law—the first major abortion case since Amy Coney Barrett replaced Ruth Bader Ginsburg—is composed of three liberals and six conservatives, three of them appointed by Donald Trump. Barrett, as a law professor at Notre Dame, signed a petition denouncing abortion. Clarence Thomas has openly declared his disdain for Roe. The best hope for retaining abortion rights might be if Chief Justice John Roberts and at least one other conservative decide that overturning Roe is too much of a blow to settled doctrine, or that it would make the Court look too nakedly political. Roberts has shown a penchant for this kind of thinking; the others, less so. (Last week, Barrett, while speaking at the McConnell Center, at the University of Louisville—named for the Republican senator who rushed through her confirmation—maintained that the Court is never partisan.)

Stare decisis is meant to protect not just institutions but also citizens who have come to depend on certain rights. Access to abortion, for all the dug-in objections to it, is one such right, and most Americans want to retain it. As Justices Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter wrote for the plurality in Casey, “The ability of women to participate in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.” That was true in 1992; it is no less true in 2021. ♦

Published in the print edition of the September 27, 2021, issue, with the headline “A Necessary Right.”

— Margaret Talbot joined The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2004. She is the author, with David Talbot, of “By the Light of Burning Dreams: The Triumphs and Tragedies of the Second American Revolution.”

0 notes

Text

There Are No “Never Trump” Republicans Anymore

(Image: The New Republic)

#NeverTrump isn’t a real political category. It’s a rhetorical strategy designed to give the GOP a pre-emptive chance to absolve itself once Trump is out of office.

It seemed for a moment in the arduously long, reality TV charade that was the 2016 election -- which, like all recent US presidential elections, took place over what felt like years instead of the one it was supposed to be -- that conservatives in the Republican Party were really going to fight the rise of Donald Trump. In March 2016, with Trump’s candidacy looking quite likely, Mitt Romney gave a speech in Utah condemning Trump on all fronts. “After all,” Romney said, reasonably, “This is an individual who mocked a disabled reporter, who attributed a reporter’s questions to her menstrual cycle, who mocked a brilliant rival who happened to be a woman due to her appearance, who bragged about his marital affairs, and who laces his public speeches with vulgarity.” Within just one year, captured in a now-infamous photo, Romney would meet with Trump in a fancy restaurant, where on the agenda was the possible scenario of Romney coming onboard the Trump cabinet. Romney didn’t get the job, which is probably for the best, but he did get spectacularly dragged by Trump, who by inviting him to dinner and then giving him nothing in return (except, one expects, the promise of tax cuts that would massively benefit people like Romney) made him out to be a “cuck,” to use the parlance of the Trump crowd.

The National Review, the long-standing conservative magazine founded by William F. Buckley, took what appeared to be a bold move in devoting a whole issue to opposing Trump’s nomination for the GOP. (The cover is the splash image at the top of this piece.) Popular conservative commentators like Glenn Beck, Erick Erickson, and Mark Helprin launched attacks at Trump from all angles, declaring him an opportunist taking advantage of a party with a long-standing intellectual and cultural tradition that Trump, according this argument, exploits solely for his personal gain. Hell, Beck even correctly presaged that if Trump were to win, “there will once again be no opposition to an ever-expanding government.” (I can think of dozens of families torn apart by Immigrations and Customs Enforcement [ICE] who would agree with Beck -- although probably for different reasons.) Beck even later confessed to fomenting the political paranoia that in part produced Trump. The National Review frequently peddles in party-loyalty lines of reasoning and the vacuous rallying call of “As long as it’s not the liberals!”, so it was surprising to see them adopt a firm anti-Trump stance so early into the primaries in January 2016. It appeared, for a moment, like a cautious self-reckoning on the part of these major conservative figures and, perhaps, the movement itself.

Two years later, in his Blaze studio, Beck sported a Make America Great Again hat and declared that he would happily vote for Donald Trump in 2020.

I could go on. “This person said Trump would ruin conservatism.... barely into his presidency, they’re already defending his every move!” is a story so common now that each new iteration feels like something barely worth mentioning.

The behavior of the conservative political scene made sense at first, even amongst those who expressed worry about Trump. People like Ben Shapiro made a big stink about how they could never vote for Trump, but then once in office, with Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, Shapiro and his colleagues in right-wing media weren’t going to use the boost in social and political capital afforded to their end of the political spectrum to damage the president. The Shapiros of the world expressed their misgivings about Trump -- he’s a liar, he’s really a New York liberal at heart, etc -- but they knew that in order to get any modicum of legislation out of their newfound control in Washington, they’d have to go through Trump. I remember tracking the posts and op-eds by the conservative commentariat in the first half year of Trump’s presidency and finding the temperature of the room pretty consistent: they could all tell he was bad news, but they weren’t about to sound the alarms just yet. After all, there are still libs to own -- and “owning the libs” is really all that can be said of the “philosophy” behind people like Shapiro, as Nathan J. Robinson so brilliantly put it -- and maybe if the GOP could ride Trump out and pick up a Gorsuch here, an Obamacare repeal there, the giant gamble of 2016 will have all been worth it.

Indeed, these “turning point” moments, where ostensible #NeverTrumpers realize just how good a conservative he is, are pretty easy to predict. The second Trump lands the GOP a mostly unqualified political win, like he did by appointing Neil Gorsuch to replace the Supreme Court seat vacated by the passing of Antonin Scalia and totally stolen from Merrick Garland, suddenly the #NeverTrumpers see the light. Immediately after it was announced that Anthony Kennedy would be stepping down, giving Trump the chance to fill another Supreme Court seat, conservative YouTuber Steven Crowder stated on Twitter, “I was pretty clearly a skeptical-optimist once Trump was nominee. And I readily admit now, that despite personal disagreements, @realDonaldTrump is absolutely the right man for THIS job at this time in history.” Like the conservatives in the executive and legislative branches of government, Crowder’s sudden enthusiasm for Trump makes sense, for now the GOP has a better shot of enshrining their increasingly unpopular policies through the least democratic of the three branches of government. (This is not to say that the Democrats haven’t liked the democratic insularity of the Supreme Court when it works to their advantage, as many astute commentators have pointed out in the wake of Kennedy’s departure announcement. Over-reliance on the judiciary, like so many problems with the US government, is a bipartisan problem.) And unlike the grueling and ultimately futile attempt to wholesale repeal Obamacare in Trump’s first year, the president’s general lack of professionalism -- to say nothing of human decency -- didn’t stop Gorsuch from getting his lifetime seat. Sure, Trump sounded weird when he introduced Gorsuch as his nominee; it seemed as if he skipped the part of Schoolhouse Rock where the Supreme Court gets explained. But at the end of the (supposed to be) perfunctory confirmation hearings, Gorsuch picked up where Scalia left off, and Trump, in the eyes of the GOP, couldn’t mess that up.

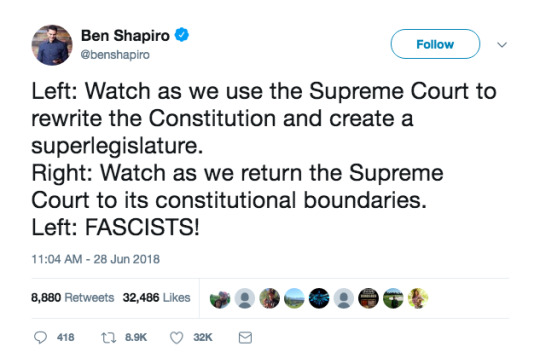

Since Trump will almost certainly get to fill the Supreme Court vacancy left by Kennedy -- anyone who thinks the likes of Susan Collins will fall out of the Senate ranks on the confirmation vote must have been asleep the past two years -- I fully expect that additional Trump skeptics will decide that in the end even the thin veneer that is their “Trump criticism” isn’t worth keeping up if it means that Roe v. Wade gets repealed. Shapiro, who in what seems like a half-joke offered himself up as a Supreme Court nominee to Trump, Tweeted,

There are so many interesting things about Shapiro’s characterization of how the two major parties have interacted with the Supreme Court, including the pervasive conflation of “Democrats” with “the Left” that renders the “criticism” and “comedy” of people like Shapiro and Crowder unintelligible most of the time. First and foremost, conservatives have been happy to use the highest court in the land to produce legislation (see Second Amendment jurisprudence, which over the course of the 20th century reads increasingly like NRA ad copy rather than sound legal scholarship) and even invent whole new nonsensical ontological doctrines (like the notion that money is speech). Secondly, Shapiro continues in the regrettably persuasive rhetorical trend of framing originalism, a doctrine that is as “forced into” the Constitution as any living document theory, as simply “returning the court to its constitutional boundaries.” Thirdly.... ah, crap, I’ve gone off topic. Some arguments are so bad that they must be rebutted immediately. I digress. I quote the Tweet merely to say: for all of his anti-Trump posturing, I get the sense he will end up intellectually prostrating just like the rest of his colleagues in conservative media. To quote George V. Higgins, whose slept-on 1974 novel A City on a Hill reads like a study of the cronyistic governance we now find ourselves under, Shapiro “is like the rest of the horses: they’re getting thirsty, but they won’t drink till they’re ready.”

Despite these ongoing series of conversions to the Trump cause, the phrase #NeverTrump, originated by conservatives in 2016 who refused to vote for Trump even after he became the GOP nominee, persists in the discourse. After a series of Tweets in which he contradictorily described “preventing illegal immigration” as “not racist” while also describing such policy as “slowing massive demographic change,” Andrew Sullivan qualified his opinions on immigration policy with this admission: “Trump is not Hitler; I am not Neville Chamberlain; i’m a passionate Never-Trumper who wants to solve a problem that is empowering white nationalism everywhere.” Writing for Bloomberg, Albert R. Hunt calls the post-Kennedy retirement moment as “a hard time” for “Never Trump Republicans.” Emerald Robinson’s analysis of Never Trumpers in the present moment offers a similarly glum prognosis: “The Never Trump intellectual crowd has no momentum and no popular following these days.” Just two years ago, the thought that the host of The Celebrity Apprentice could come to define contemporary conservatism seemed laughable, even following his 2016 win. Most had the sense that Trump would fumble through whatever time he had in office, either until he was voted out, removed from office for any number of reasons (violations of the emoluments clause or Russia, take your pick), or if he got bored and quit. But in 2018, President Trump is finally winning.

“Never Trump” does, to some extent, accurately characterize the internecine squabbles amongst the conservative side of American politics. Some have been openly critical, and some, like George Will, have even called on Americans to vote for the Democrats to hold the Republicans to account. (Some have decided not to run for re-election in 2018, having successfully completed their life’s work of kicking poor people further down the curb to further enrich the already money-drenched upper strata of American society. Er, I mean, to spend time with their families.) But the term really should have died on November 8th, 2016. Since that day, the category of “Never Trump” has dwindled. What we really have that comes closest to “Never Trumpers” in the present day are “conservatives who occasionally criticize Trump.” Perhaps it’s just me, but I feel that “Never” carries a firm, imperative force that occasional criticism cannot live up to -- especially when that criticism becomes increasingly occasional. Admittedly, my point here is not novel: conservative commentator Jonah Golberg pronounced the Never Trump movement to be “nevermore” and over just a month after the Trump/Clinton election. Yet the name persists. Why?