#discobolus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Let's Play: What's Wrong with this Sculpture?

Following in the theme of sharing astonishing moments of ancient sculpture pedantry here on Tumblr, based on my brief undergraduate stint as a T.A of ancient art history, I thought I'd share one of my other proudest moments of being an absolutely insufferable know-it-all about ancient sculptures.

In the process, I hope I can also share some of the sort of largely useless (from a practical perspective) information that Tumblr tends to glory in, so buckle up buttercups.

This question was posed to me on a walking tour of the Capitoline Museum in my ancient art history class while I was living abroad. Our professor, a delightfully curmudgeonly Belgian, stopped in front and asked us to figure out why this sculpture is just plain wrong.

I intend to walk you through the process of how I got the right answer and, after gaining my teacher's rare approval, glowed with enough serotonin to power a small nuclear reactor.

So, let's return to the original question: what is wrong with this sculpture?

Because if you are truly eagle-eyed you should be able to spot what very famous sculpture this actually is, before an overly imaginative Frenchman brought it back wrong.

Hint #1: It was incorrectly restored.

Look closely at the the difference of the patina, or color of the stone. It's a bit hard to tell in this photo, but the head was added later. It's a paler white than the core of the torso, which is what we have of the original sculpture.

Hint #2: It was incorrectly restored in the 18th century by a Frenchman (Pierre-Étienne Monnot) who made some, shall we say, creative interpretations of what's going on here.

You can tell it's by an 18th c. Frenchman because the facial features are so delicate. Ancient statues tend to have less narrow and delicate chins and noses. In general, that is a dead giveaway when something is 18th century French vs. Ancient Greek or Roman.

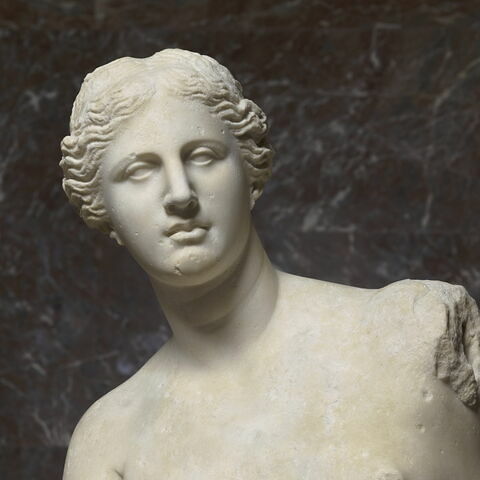

Here's a good example. The first sculpture is 18th c. French, the second is the famous Venus de Milo. Note her blockier chin and less delicate features. So in the future, you can tell these sort of later additions to Greek or Roman sculptures if they added a new head because 17-19th century sculptors in Europe had tools (like finer drill tips) and tastes (beauty standards that favored more delicate men and women) that led to a pronounced difference in the faces.

Hint #3: Check out the anatomy of his lower shoulder. That's another addition, that arm should not be coming straight out of a torso where the muscle, if you look closely, is turned inward.

Seriously, that looks painful.

Hint #4: The sword he's holding up is just total nonsense for the Roman era. I mean, the restoration makes no secret of the fact that this sword is a later addition, but it's also just an absolute nonsense sword with its silly little curved cross guard. This Frenchman literally just made it up.

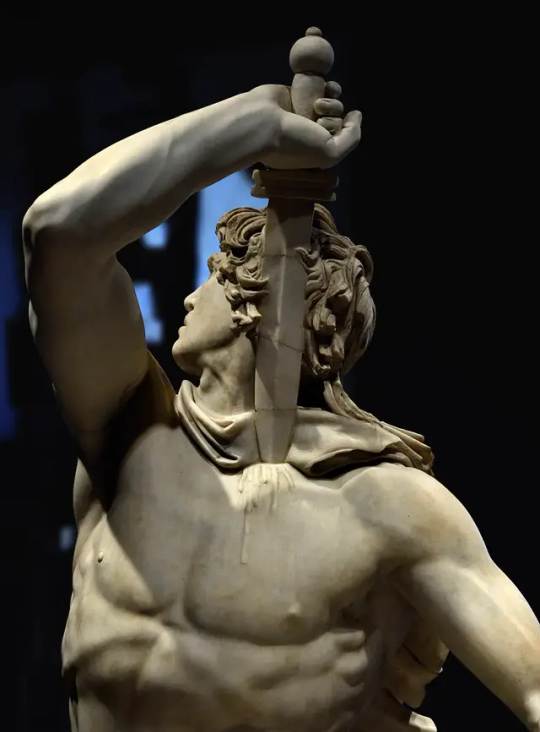

Here's an ancient sculpture with a sword in it that actually looks right:

From the Ludovisi Gaul, a famous Hellenistic Baroque work of Greek sculpture. Note the much blockier sword though I will admit, it could be a later addition, I don't know for 100% certain, but I'm pretty sure it's the original. Regardless, it fits the sculpture much better and let me add that sword I'm criticizing is completely made up for the sculpture we're talking about and is not there in the original sculpture that was incorrectly restored.

Ok, so those are all the hints.

Look closely at the body of the first sculpture. Cut away the arms that are not connected to the body correctly, the sword that shouldn't be there, the face that was far too delicate. When you separate those later additions out, can you tell me what sculpture that actually is?

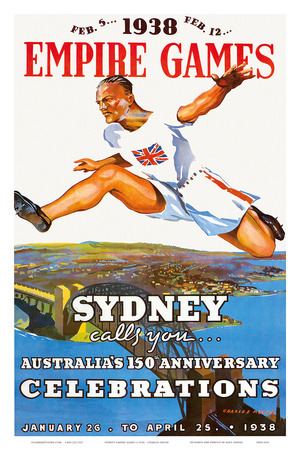

Because here is the reveal!

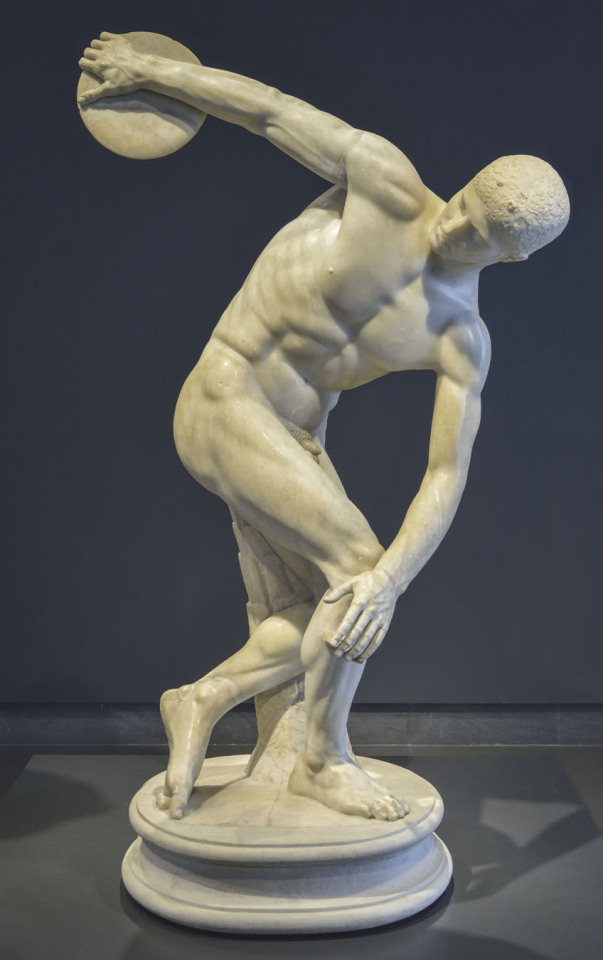

The Discus Thrower, aka, the Discobolus by Myron.

The French restorationist got carried away by his own imagination, saw a twisted torso and thought it could only possibly be a warrior in the midst of twisting around to fend off a blow, not an athlete in the midst of a demonstration of skill. It's a martial, fanciful read that completely misinterpreted the subject.

This is why most restoration today employs a much lighter touch, rather than trying to reattach pieces incorrectly, they tend to just outline where the missing pieces are with a light sketch of an educated guess of what might have actually been there. Faulty restorations like the Capitoline Discobolus is one reason for this modern stylistic principle when it comes to restoration work.

When my professor asked us to identify the correct original sculpture that day on the museum tour, it was the sword that pinged me as wrong first, but zeroing in on the core of the sculpture, the torso, is what revealed the true statue underneath.

This notoriously difficult to please professor was very proud when I blurted out, "It's the Discus Thrower!" and the high-octane serotonin I got from his approval probably could have propelled me into the sun that day, and brought to you Yet Another Moment of Ancient Sculpture Pedantry.

#ancient history#ancient rome#art history#discobolus#there are very few things I'll brag about but naming this sculpture correctly is one of them#in part because there was so little to be gained lol oh well might as well make a tumblr post about it

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michelangelo's David is kitsch, and was the day it was sculpted.

The Discobolus of Myron is kitsch, and was the day it was sculpted.

The right half of Botero's Adam and Eve is kitsch, and was the day it was painted.

Pollaiuolo's Battle of the Nudes is kitsch, and was the day it was engraved.

No matter how much these works are puffed up in art history classes the world over, male nudity is inherently disgusting and kitsch, and always has been.

#male nudity#artistic nude#Michelangelo's David#David by Michelangelo#Fernando Botero#Adam and Eve by Botero#Antonio del Pollaiuolo#Discobolus#Kitsch

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Myron (Greek Athenian) Discobolus, ca. 460-450 BC

#roman#athenian#art#fine art#sculpture#european art#classical art#europe#european#cradle of civilization#discobolus#greek#greece#fine arts#mediterranean#europa#southern europe#traditional art

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discobolus, discus thrower statue. A young adult male discus thrower.

#discus#discobolus#statue#statues#thrower#discus thrower#discus throwers#a statue#human statue#sport#sports#athletics#photography#photo#photograph#picture#photos#photographs#image#a statue photo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Discobolus”. Comic by E. Shabelnik, published in Krokodil magazine (1981).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

myron's diskobolos

basic information

name: diskobolos

date: 460-450 bce

artist: myron

original, reconstructed, or copy: roman marble copy of a bronze original

subject matter

myron's diskobolos depicts a discus-thrower in the moment between the back swing and forward throw of the athlete. notably, this is a change from just athletic figures to actual athletes.

context

the sculpture is a marble copy of a bronze original, which has now been lost. the most important things to remember when analysing marble copies are that a) the tensile strength of marble is much lower than that of bronze, and so marble copies require supports that the original wouldn't, and b) there will be differences between the original and other copies; this is particularly evident in the positioning of the head.

composition

the pose of diskobolos is particularly notable as a bold move by sculptors that were becoming more familiar with the capabilities of bronze. the body and the arms create two intersecting arcs, which help to create more dynamism in the statue. the two arcs are from the right knee to the right shoulder, and from following the arms from one hand to the other. this demonstrates a very interesting depiction of motion, and some very appealing compositional lines. the pose is not particularly effective for a discus thrower, but this does not detract from the statue - the action is still clear, and the pose highlights the strength and beauty of the male form.

the anatomy is particularly advanced; while there are some muscle groups, such as the intercostal muscles, that appear slightly over-exaggerated, the majority of the muscles are naturalistically produced, and there is a notable consideration to the manner in which these muscles interact with each other.

despite the clear tension of the muscles, the face of myron's diskobolos is serene and largely unaffected by the effort of his action; this controlled subtlety of expression is one of the key symbols for the severe style. you can use this to argue either for or against its appeal; you could say it is less appealing because it is less realistic, or it is more appealing because it shows a more idealised yet still naturalistic representation of an athlete.

the statue is well proportioned; the muscles are defined, yet still make sense as part of the body, without appearing oversized or otherwise unnaturalistic. the human form is very well represented in this statue.

we also have the prop that the statue is holding - the discus. this prop allows the subject of the statue to become more clear, making the narrative of the statue much easier to follow.

stylistic features

this statue is part of the transitional severe style, where naturalistic human forms met idealised serenity and stoicism. this is particularly evident when analysing the difference between the expression and the musculature; the intercostal muscles are highly defined and clearly tensed, but the face remains still and unfeeling.

scholars

woodford: "consistently both symmetry and repetition are avoided"

boardman: "another difference [of] marble copies of bronzes is the addition of struts and supports ... which were unnecessary to a bronze original"

extra information

british museum

schmalbeck, furman university

#a level classical civilisation#a level classics#classics#classical civilisation#ocr classical civilisation#greek art#discobolus#diskobolos#greek statue

1 note

·

View note

Photo

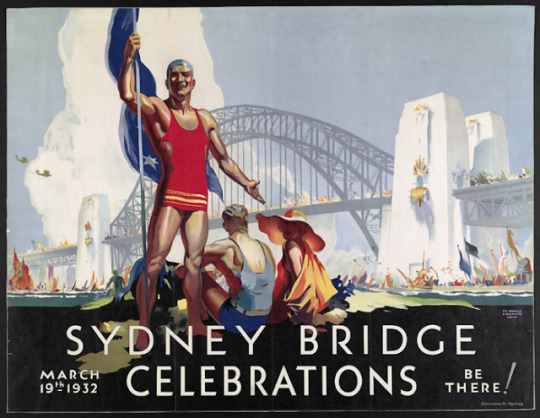

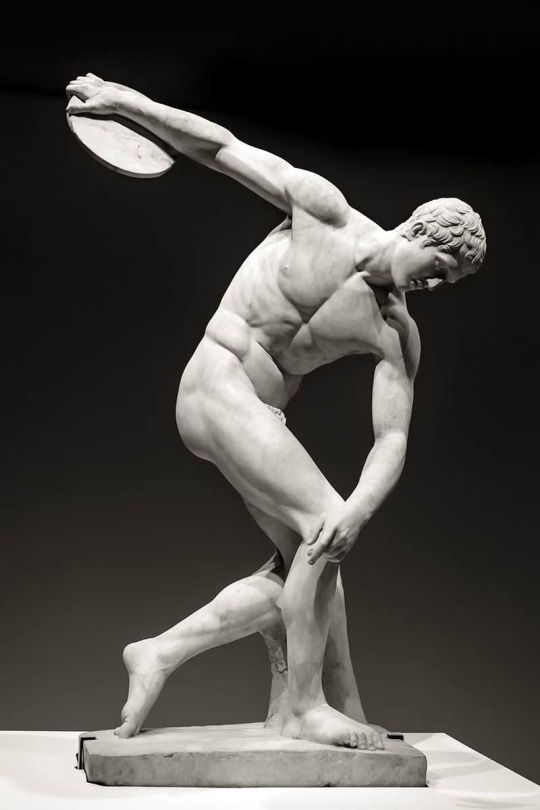

Persistence of the classical ideal

1 Myron, Discobolus (Discus Thrower), Roman copy of an ancient Greek bronze from c. 450 B.C.E. http://cciv214fa2012.site.wesleyan.edu/classical-period/exhibit-2/

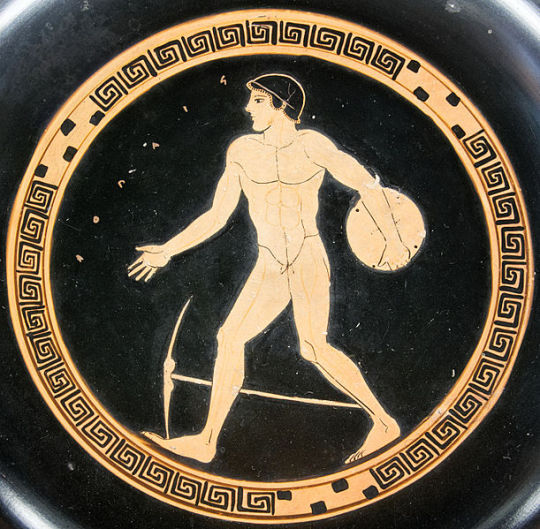

2 Artist unknown Discobolus motif on an Attic (Ancient Greek) red-figured ceramic cup, circa. 490 BC, is static by comparison.

watch: A succinct explanation of dynamism in sculpture: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OhJKDqZgNXg

3 Artist unknown, promotional poster for the Empire Games in Sydney, (1938) colour lithograph

4 Charles Meere Atlanta’s Eclipse (1938)

A Joy Eadie 2012 www.shervingallery.com.au The S.H. Ervin Gallery collection contains two major paintings by significant artist Charles Meere (1890-1961). The Trust is committed to caring for and sharing these important artworks however conservation is costly.

Many Australian art lovers are familiar with Charles Meere’s iconic Australian Beach Pattern, one of the most popular and frequently-reproduced works in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, but are less familiar with his name.

English-born painter Charles Meere came to Australia after serving in France in World War I, training at the Royal College of Art in London, and living for some years in Brittany. While running a commercial art practice in Sydney, he taught at East Sydney Technical College, exhibited with the Society of Artists, and regularly entered the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prize competitions.

He painted landscapes, still life and portraits, and a number of paintings in Art Deco style. These are his crowning achievement, notable for their complexity, their use of allusion and ambiguity, and their sheer beauty. The National Trust is fortunate in holding two of them, Atalanta’s eclipse and Triptych, however they are in a fragile state and in urgent need of restoration.

Atlanta’s Eclipse is a remarkable work. It was awarded the Sulman Prize in 1938. Art historian Edward Lucie-Smith has described it as “surely one of the most elegant and accomplished of all the high-style classical compositions produced by Deco artists...”

With its classical subject, its complex allusions in style, imagery and composition, Meere probably designed it specifically for the 1938 inaugural exhibition of the Australian Academy of Art as the ultimate academic painting, not without an element of parody, in the context of the public debate about the Academy.

It depicts the race between Atalanta and Hippomenes, recounted in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. A light-hearted reworking of Guido Reni’s tense, rather dark version of the myth in the Prado, Meere’s painting plays with styles and images from International Gothic, the Renaissance, and Baroque, to the glamorised figures of 20th century advertising.

The complexity, the richness of visual imagination, and the eclectic use of allusion bring to Meere’s beautifully-executed image sophistication quite different from that of the mainstream Sydney modernists of the day.

Triptych is one of several similar works painted in the late 1930s. In a continuous scene spread across three panels, the central panel is given to the Three Graces, personifications of grace, beauty, and festivity, and friends of the Muses. The left panel evokes natural beauty through the putti strewing flowers and the leaping fawns, while in the right panel the gods Hermes with his lyre and Pan with his pipes evoke the Muses.

The Graces, rather sexy and modern, yet have some gravitas; they are elegant, cool and reserved rather than erotic. Triptych presents both classical restraint and charm, giving the kind of delight associated with the Graces themselves.

It is important that these works be restored for the public as exceptional examples of 1930s figurative painting; and to affirm Meere as the creator of a body of work unique in 20th century Australian art.

5 Douglas Annand Sydney Harbour Bridge Celebrations poster (1932)

6 Charles Meere poster for Sydney Empire Games (1938); 7 commemorative stamp issued at the time.

0 notes

Text

The Vatican Discobolus, 2nd century A.D., after a lost bronze of the discus thrower by the Greek sculptor Myron (circa 460-420 B.C.). The sculpture was discovered at Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli, in 1791.

Pio Clementino Museum, Vatican, Rome.

#The Vatican Discobolus#2nd century A.D.#Greek sculptor Myron#emperor hardian#Hadrian’s Villa#Pio Clementino Museum#marble#marble statue#marble sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman art#ancient art#art history

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DISCOBOLUS (DISCUS-THROWER) | 450 BCE | by MYRON

THE DISCOBOLUS is a renowned GREEK sculpture depicting an athlete about to throw a discus. It is considered one of the masterpieces of classical GREEK art and a testament to the skill and artistry of the sculptor, MYRON.

The sculpture captures the athlete in a mid-throw, with his body coiled and poised in anticipation. His left arm is drawn back, ready to release the discus. The figure is rendered with an incredible sense of movement and tension, as if frozen in time. MYRON employed a technique revealing the underlying musculature. This technique showcased MYRON'S mastery of anatomy and the ability to convey movement through the depiction of form.

THE DISCOBOLUS is also notable for its use of contraposto, a pose where the weight of the body is shifted to one leg, creating a dynamic and asymmetrical composition. This technique emphasizes the athlete's athleticism and the tension in his body as he prepares to throw.

THE DISCOBOLUS celebrates the physical prowess and athleticism of the GREEKS. It encapsulates the spirit of competition and the pursuit of excellence that was so important to GREEK culture. Beyond its athletic and aesthetic significance, THE DISCOBOLUS has also been interpreted as a symbol of balance, harmony, and the pursuit of perfection. It represents the ideals of classical GREECE and continues to inspire awe and admiration in viewers today.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph looks like a cross between Michaelangelo's David statue and The Discobolus atm?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Resting Discobolus”, c.1830 by Mathieu Kessels (1784-1836). Dutch Neoclassical sculptor. Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome.

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of the Townley Discobolus, a Roman copy of an ancient Greek bronze by Myron. While the copy dates to the 2nd century CE, the original bronze would have been dated to 460-450 BCE.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my goodness I didn't even notice I have over 100 followers now, TBH I get a little scared posting because people might start booing and throwing tomatoes but I'm still very much active I promise!

Anywho, today I wanted to post about his statues since I find them neat. This post probably won't be super in-depth, maybe just pointing out which statues reference what, but if you know my account, you know I love to talk, so.

Sticking to the ones that are in reference to already existing statues, firstly his statue replicating Discobolus

Now, it's believed by many people that Discobolus represents the 'athletic ideal' while also being admired for capturing an unmatched representation of proportion, harmony, rhythm, and balance.

It is known through Ratio's character stories that he keeps his body in peak condition in the same way he does his mind. I enjoy the thought of him playing sports, especially after one of the Hoyofair videos, and the concept of him sculpting himself with inspiration drawn from what was considered ideal for athletes at the time is an interesting concept. Perhaps it is a way of channeling potential issues of perfectionism regarding his athletic capabilities.

Next up, his statue depicting The Benavides Monument

I find this one particularly interesting because the Monument was originally built to commemorate Miguel de Benavides, the founder of the University of Santo Tomas. As seen in Ratio's character stories the university that he graduated from does share a first name with him (why that is hasn't been disclosed to my knowledge), and such I find it neat that this is a potential reference to a University founder within history.

Lastly, I believe this statue is a reference to the statue of Arnold Schwarzenegger

This one I'm honestly not as confident about this in comparison to the other two, however, Arnold Schwarzenegger is regarded as one of the greatest bodybuilders of all time, and this statue was built to commemorate his relationship with Columbus. (Funnily enough, Arnold Schwarzenegger also commissioned the massive statue of himself and it's easy to assume that Ratio sculpted his himself.)

#guys ive had no idea what to post im gonna be honest#i would mention the other two but theyre just heart hands and the jojo stand pose respectively#i love the heart hands one so much why did he make that /pos#★ – posts!#★ – analysis!#dr ratio#dr veritas ratio#veritas ratio#hsr dr ratio#hsr ratio#honkai star rail#hsr

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

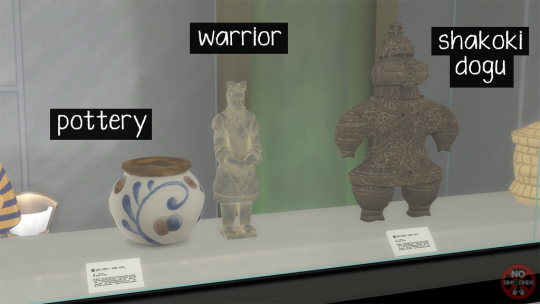

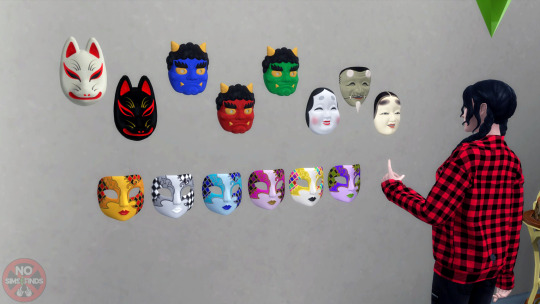

🏛️🏺 ACNH Museum Statues Set 🏺🏛️

Sims 4, base game compatible. 26 items. I hope you enjoy! This set is brought to you by the lovely patrons who voted 💗

Always suggested: bb.objects ON, it makes placing items much easier. For further placement tweaking, check out the TOOL mod.

Set Contains: -Armor | 4 swatches | 1202 poly -Capitolini Wolf | 1 swatch | 2259 poly -David | 1 swatch | 4704 poly -David Pedestal | 5 swatches | 104 poly -Discobolus | 2 swatches | 1238 poly -Houmuwu Ding | 1 swatch | 2226 poly -King Kamehameha | 1 swatch | 2410 poly -King Kamehameha Souvenir | 1 swatch | 2410 poly -Moai | 2 swatches | 3064 poly -Moai Souvenir | 4 swatches | 3064 poly -Mossy Guy | 6 swatches | 1200 poly -Nefertiti | 2 swatches | 972 poly -Nefertiti Souvenir | 2 swatches | 972 poly -Nike | 1 swatch | 3019 poly -Olmec | 2 swatches | 3498 poly -Pottery | 5 swatches | 802 poly -Shakoki Dogu | 1 swatch | 1076 poly -The Thinker | 2 swatches | 1144 poly -Venus de Milo | 3 swatches | 1138 poly -Wall Mask: Elder | 1 swatch | 1206 poly -Wall Mask: Fox | 2 swatches | 1216 poly -Wall Mask: Noh (woman's face) | 1 swatch | 1212 poly -Wall Mask: Ogre | 3 swatches | 1208 poly -Wall mask: Kokame (woman's face) | 1 swatch | 1212 poly -Wall Mask: Venetian | 6 swatches | 1602 poly -Warrior | 1 swatch | 1004 poly

Type “acnh museum statues" into the search query in build mode to find quickly. You can always find items like this, just begin typing the title and it will appear.

As always, please let me know if you have any issues!

📁 Download all or pick & choose (SFS, No Ads): HERE

📁 Alt Mega Download (still no ads): HERE

📁 Download on Patreon

Will be public on May 9th, 2024 💗

Happy Simming! ✨ Some of my sets are early access. If you like my work, please consider supporting me:

★ Patreon 🎉 ❤️ |★ Ko-Fi ☕️ ❤️ ★ Instagram📷

Thank you for reblogging ❤️ ❤️ ❤️

@sssvitlanz @maxismatchccworld @mmoutfitters @coffee-cc-finds @itsjessicaccfinds @gamommypeach @stargazer-sims-finds @khelga68 @suricringe @vaporwavesims @mystictrance15 @moonglitchccfinds @xlost-in-wonderlandx @jbthedisabledvet

-King Tut Bust-Bastet Statue -Museum Displays -More Museum Displays & Partitions -Rope Partition -Fossil Museum Sets (scroll page, sets contain other museum items) -Mini Statues Set

The rest of my CC

Please do also check out the 2 sets/collab from @aroundthesims & @mlyssimblr for the museum exhibit (lots of gift shop items):

⭐️https://sims4.aroundthesims3.com/objects/room_community_21.shtml

⭐️https://mlyssimblr.tumblr.com/post/153354021958/ats4-mlys-exhibition-set

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that's all of them?...

hc: his hobby is sculpting

(on the right is an antique statue of Discobolus by Myron)

312 notes

·

View notes