#dinodontosaurus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

And so the Chañares Formation #paleostream! Our first stream decided by THE WHEEL!

Look below to see what it has decided on for next Saturday!

It appears we will visit the Hanson Formation! Realm of Cryolophosaurus!

445 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The advanced paramammals, the theraspids, evolved some 50 million years after the early flesh eaters. Giant lumbering plant eaters such as Moschops were forerunners of dicynodonts such as Lystrosaurus and Dinodontosaurus. Fierce flesh eaters such as Titanosuchus were ancestors of both the cynodonts (Thrinaxodon and Cynognathus) and the bauriamorphs (Bauria). Furry, warm-blooded flesh eaters, these were only a step away from being mammals. Morganucodon, the first true mammal, evolved around 200 million years ago."

From "The Evolution of the Mammals" (1978), by L.B. Halstead. This illustration by Enzo Carretti.

#theraspids#moschops#dicynodont#lystrosaurus#dinodontosaurus#titanosuchus#cynodonts#thrinaxodon#cynognathus#bauriamorphs#bauria#morganucodon#paleoart

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinovember 2024 Day 28: Santa Maria - The New Dawn

Ecology from Brazil’s Santa Maria Formation, showing from left to right: Saturnalia, Dinodontosaurus, Staurikosaurus, Gnathovorax, two Buriolestes, and the Lagerpetid Ixalerpeton

#paleoart#dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleontology#dinovember#dinovember 2024#staurikosaurus#late triassic#triassic period#triassic

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 20 - Prestosuchus chiniquensis

The Triassic was truly when Pseudosuchians ruled the earth. They came in a variety of different shapes and sizes and filled almost every niche. During this period, nearly every apex predator was a pseudosuchian. In the Middle Triassic of Brazil, this niche was filled by Prestosuchus chiniquensis. Originally estimated at around 5 meters long, a Prestosuchus specimen found in 2010 now places their upper size limits at nearly 7 meters (23 feet) long, making them one of the largest Triassic pseudosuchians, only surpassed by Saurosuchus. Like the crocodilians who would come later Prestosuchus walked on four legs, but in a more dinosaurian upright stance. Large Prestosuchians are assumed to be ambush predators, and this is supported by the finding of one Prestosuchus specimen in a fossil deposit assumed to be a local watering hole, a location ambush predators would have frequently haunted. This particular specimen had such a well-preserved hind leg that paleontologists were able to study its precise muscle groupings and confirm that Prestosuchus would have only been able to walk quadrupedally, unlike the related bipedal Poposaurus.

Prestosuchus chiniquensis could have preyed on most anything in Middle Triassic Brazil. Dicynodonts like Dinodontosaurus and Stahleckeria would have been their largest prey items. It could have hunted smaller pseudosuchians like Decuriasuchus, Pagosvenator, and Procerosuchus. Other archosauromorphs would have included silesaurids like Gamatavus, aphanosaurs like Spondylosoma, and rhyncosaurs like Brasinorhynchus. Cynodonts like the carnivorous Chiniquodon and the herbivorous Exaeretodon would have also been on the menu.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Prestosuchus chiniquensis#Prestosuchus#prestosuchid#pseudosuchians#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#archovember2023

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'm probs too late to get a dinovember prompt in, but... dinodontosaurus and a matador?

Dinovember Day 8: ¡Olé!

645 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Haja layer para tentar deixar o bicho com cara de vivo! #paleoart #dinodontosaurus #dino #dinossauro #dinosaur # #jurassicworld #jurassicpark #marciolcastro #3d #zbrush #Photoshop (em Belo Horizonte, Brazil)

#3d#dinossauro#dinosaur#jurassicworld#paleoart#jurassicpark#photoshop#zbrush#marciolcastro#dinodontosaurus#dino

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sample of Triassic terrestrial fauna, from Early to Late Triassic. From left to right: Lystrosaurus murrayi, Proterosuchus fergusi, Galesaurus planticeps, Erythrosuchus africanus, Shringasaurus indicus, Batrachotomus kupferzellensis, Dinodontosaurus turpior, Teleocrater rhadinus, Marasuchus lilloensis, Silesaurus opolensis, Hyperodapedon gordoni, Ornithosuchus woodwardi, Postosuchus kirkpatricki, Pseudochampsa ischigualastensis, Hesperosuchus agilis, Poposaurus gracilis, Blikanasaurus cromptoni, Desmatosuchus spurensis, Caelestiventus hanseni, Smilosuchus gregorii and Megazostrodon rudnerae.

#paleoart#triassic#paleoblr#paleoillustration#palaeontology#dinosaurs#palaeoblr#archosaur#therapsid#illustration#animals#palaeoart

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lagerpeton

By Tas

Etymology: Rabbit Reptile

First Described By: Romer, 1971

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Crurotarsi, Archosauria, Avemetarsalia, Ornithodira, Dinosauromorpha, Lagerpetidae

Referred Species: L. chanarensis

Status: Extinct

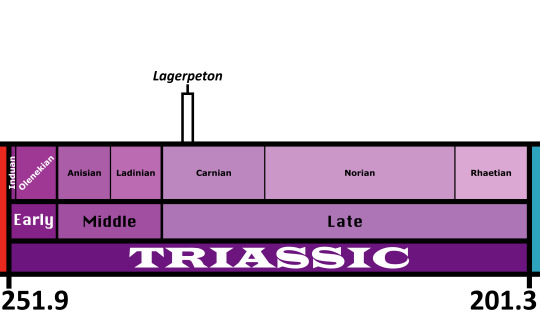

Time and Place: About 235 to 234 million years ago, in the Carnian of the Late Triassic

Lagerpeton is known from the Chañares Formation in La Rioja, Argentina

Physical Description: Lagerpeton was named as the Rabbit Reptile, and for good reason - in a lot of ways, it represents a decent attempt by reptiles in trying to do the whole hoppy-hop thing. You might think that it resembles Scleromochlus in that way, and you’d be right! Scleromochlus and Lagerpeton are close cousins, but one is on the line towards Pterosaurs - Scleromochlus - and the other is on the line towards dinosaurs - Lagerpeton. So, hopping around was an early feature that all Ornithodirans (Dinosaurs, Pterosaurs, and those closest to them) shared. Lagerpeton itself was about 70 centimeters in length, with most of that length represented as tail; it was slender and lithe, built for moving quickly through its environment. It had a small head, a long neck, and a thin body. While it had long legs, it also had somewhat long arms, and while it may have been able to walk on all fours it also would have been able to walk on two legs alone. It was digitigrade, walking only on its toes, making it an even faster animal. Its back was angled to help it in hopping and running through its environment, and its small pelvis gave it more force during hip extension while jumping. In addition to all of this, it basically only really rested its weight on two toes - giving it even more hopping ability! As a small early bird-line reptile, it would have been covered in primitive feathers all over its body (protofeathers), though what form they took we do not know.

By Scott Reid

Diet: As an early dinosaur relative, it’s more likely than not that Lagerpeton was an omnivore, though this is uncertain as its head and teeth are not known at this time.

Behavior: Lagerpeton would have been a very skittish animal, being so small in an environment of so many kinds of animals - and as such, that hopping and fast movement ability would have aided it in escaping and moving around its environment, avoiding predators and reaching new sources of food (and, potentially, chasing after smaller food itself). Lagerpeton may have also been somewhat social, moving in small groups, potentially families, to escape the predators and chase after prey together, given its common nature in its environment. As an archosaur, Lagerpeton was more likely than not to take care of its young, though we don’t know how or to what extent. The feathers it had would have been primarily thermoregulatory, and as such, they would have helped it maintain a constant body temperature - making it a very active, lithe animal.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Lagerpeton lived in the Chañares environment, a diverse and fascinating environment coming right after the transition from the Middle to Late Triassic epochs. Given that the first true dinosaurs are probably from the start of the Late Triassic, this makes it a hotbed for understanding the environments that the earliest dinosaurs evolved in. Since Lagerpeton is a close dinosaur relative, this helps contextualize its place within its evolutionary history. This environment was a floodplain, filled with lakes that would regularly flood depending on the season. There were many seed ferns, ferns, conifers, and horsetails. Many different animals lived here with Lagerpeton, including other Dinosauromorphs like the Silesaurid Lewisuchus/Pseudolagosuchus and the Dinosauriform Marasuchus/Lagosuchus. There were crocodilian relatives as well, such as the early suchian Gracilisuchus and the Rauisuchid Luperosuchus. There were also quite a few Proterochampsids, such as Tarjadia, Tropidosuchus, Gualosuchus, and Chanaresuchus. Synapsids also put in a good show, with the Dicynodonts Jachaleria and Dinodontosaurus, as well as Cynodonts like Probainognathus and Chiniquodon, and the herbivorous Massetognathus. Luperosuchus would have definitely been a predator Lagerpeton would have wanted to get away from - fast!

By Ripley Cook

Other: Lagerpeton is one of our earliest derived Dinosauromorphs, showing some of the earliest distinctions the dinosaur-line had compared to other archosaurs. Lagerpeton was already digitigrade - an important feature of Dinosaurs - as shown by its tracks, called Prorotodactylus. These tracks also showcase that dinosaur relatives were around as early as the Early Triassic - and that their evolution, and the rapid diversification of archosauromorphs in general, was a direct result of the end-Permian extinction.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arcucci, A. 1986. New materials and reinterpretation of Lagerpeton chanarensis Romer (Thecodontia, Lagerpetonidae nov.) from the Middle Triassic of La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 23 (3-4): 233-242.

Arcucci, A. B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24: 89 - 94.

Arcucci, A., C. A. Mariscano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19: 228 - 232.

Bittencourt, J. S., A. B. Arcucci, C. A. Marsicano, M. C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1 - 31.

Brusatte, S. L., G. Niedzwiedzki, R. J. Butler. 2011. Footprints pull origin and diversification of dinosaur stem lineage deep into Early Triassic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278 (1708): 1107 - 1113.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2006. A review of the systematic position of the dinosauriform archosaur Eucoelophysis baldwini Sullivan & Lucas, 1999 from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA. Geodiversitas 28(4):649-684.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2016. The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriformes. PeerJ 4: e1778.

Fechner, R. 2009. Morphofunctional evolution of the pelvic girdle and hindlimb of DInosauromorpha on the lineage to Sauropoda (Thesis). Ludwigs Maximillians Universita.

Fiorelli, L. E., S. Rocher, A. G. Martinelli, M. D. Ezcurra, E. Martin Hechenleitner, M. Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle-Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496: 85 - 102.

Kammerer, C. F., S. J. Nesbitt, N. H. Shubin. 2012. The first Silesaurid Dinosauriform from the Late Triassic of Morocco. Acta Palaeontological Polonica 57 (2): 277.

Kent, D. V., P. S. Malnis, C. E. Colombi, A. A. Alcober, R. N. Martinez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 7958 - 7963.

Irmis, R. B., S. J. Nesbitt, K. Padian, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner, D. T. Woody, and A. Downs. 2007. A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs. Science 317:358-361.

Jenkins, F. A. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VII. The postcranial skeleton of the traversodontid Massetognathus pascuali (Therapsida, Cyondontia). Breviora 352: 1 - 28.

Langer, M. C., S. J. Nesbitt, J. S. Bittencourt, R. B. Irmis. 2013. Non-dinosaurian Dinosauromorphs. Geological Society London, Special Publications. 379 (1): 157 - 186.

Marsh, A. D. 2018. A new record of Dromomeron romeri Irmis et al., 2007 (Lagerpetidae) from the Chinle Formation of Arizona, U.S.A. PaleoBios 35:1-8.

Marsicano, C. A., R. B. Irmis, A. C. Mancuso, R. Mundil, F. Chemale. 2016. The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of AMerica 113 (3): 509 - 513.

Martz, J. W., and B. J. Small. 2019. Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae). PeerJ 7:e7551:1-71.

Nesbitt, S. J., R. B. Irmis, W. G. Parker, N. D. Smith, A. H. Turner and T. Rowe. 2009. Hindlimb osteology and distribution of basal dinosauromorphs from the Late Triassic of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(2):498-516.

Nesbitt, S. J. 2011. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 353:1-292.

Perez Loinaze, V. S., E. I. Vera, L. E. Fiorelli, J. B. Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502: 31 - 51.

Rogers, R. R., A. B. Arcucci, F. Abdala, P. C. Sereno, C. A. Forster, C. L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16: 461 - 481.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. I. Introduction. Breviora 247: 1 - 14.

Romer, A. S. 1966. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. II. Sketch of the geology of the Rio-Chañares-Rio Gualo Region. Breviora 252: 1 - 20.

Romer, A. S. 1967. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. III. Two new gomphodonts, Massetognathus pascuali and M. teruggii. Breviora 264: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1968. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IV. The dicynodont fauna. Breviora 295: 1 - 25.

Romer, A. S. 1969. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. V. A new chiniquodontid cynodont, Probelesodon lewisi - cynodont ancestry. Breviora 333: 1 - 24.

Romer, A. S. 1970. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VI. A chiniquodont cynodont with an incipient squamosal-dentary jaw articulation. Breviora 344: 1 - 18.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. VIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 373: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. IX: The Chanares Formation. Breviora 377: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians. Breviora 378:1-10.

Romer, A. S. 1971. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XI. Two new long-snouted thecodonts, Chanaresuchus and Gualosuchus. Breviora 379: 1 - 22.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XII. The post cranial skeleton of the thecodont Chanaresuchus. Breviora 385: 1 - 21.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIII. A fragmentary skull of a large thecodont, Luperosuchus fractus. Breviora 389: 1 - 8.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. Lewisuchus admixtus, gen. et sp. Nov., a further thecodont from the Chañares beds. Breviora 390: 1 - 13.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus. Breviora 394: 1 - 7.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVI. Thecodont classification. Breviora 395:1-24.

Romer, A. S. 1972. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVII. The Chañares gomphodonts. Breviora 396: 1 - 9.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XVIII. Probelesodon minor, a new species of carnivorous cynodont; family Probainognathidae nov. Breviora 401: 1 - 4.

Romer, A. S., and A. D. Lewis. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XIX. Postcranial materials of the cynodonts Probelesodon and Probainognathus. Breviora 407: 1 - 26.

Romer, A. S. 1973. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XX. Summary. Breviora 413: 1 - 20.

Sereno, P. C., and A. B. Arcucci. 1994. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(1):53-73.

#Lagerpeton#Dinosaurmorph#Lagerpetid#Triassic#Palaeoblr#Triassic Madness#Ornithodiran#Triassic March Madness#South America#Omnivore#Prehistoric Life#Prehistory#Palaeontology#Lagerpeton chanarensis#dinosaur#paleontology#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lisowicia bojani

By Scott Reid

Etymology: From Lisowice

First Described By: Sulej & Niedźwiedzki, 2019

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Synapsida, Eupelycosauria, Sphenacodontia, Sphenacodontoidea, Therapsida, Eutherapsida, Neotherapsida, Anomodontia, Chainosauria, Dicynodontia, Therochelonia, Bidentalia, Dicynodontoidea, Kannemeyeriiformes, Stahleckeriidae, Placeriinae

Status: Extinct

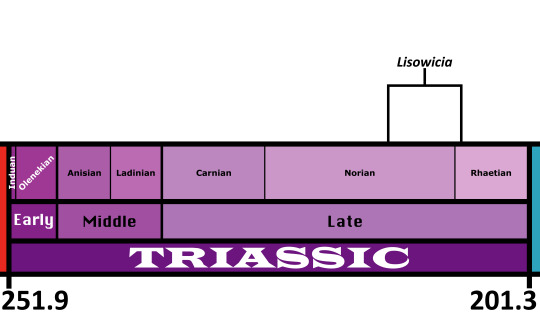

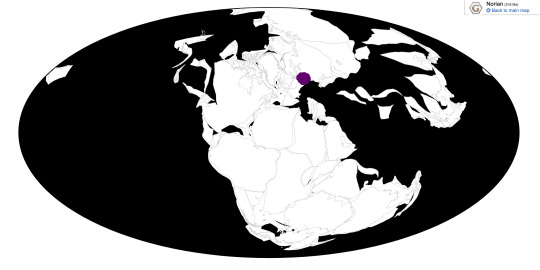

Time and Place: Approximately between 208 to 215 million years ago, in the late Norian to possibly the earliest Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Lisowicia is known from the Lipie Śląskie clay−pit near Lisowice, Poland, as well as possibly other coeval sites in Poland

Physical Description: Lisowicia was a very large dicynodont. In fact, with an estimated length of more than 4 metres, a hip height over 2 metres, and an average body weight of 5.88 tons (and possibly up to 7 tons), it was the largest non-mammalian synapsid period, and would be the largest synapsids would ever grow to until the Eocene after the non-avian dinosaurs died out. By and large (ha!), Lisowicia resembles other closely related Triassic dicynodonts like Placerias; it was heavily built with a large barrel-shaped torso and short, stocky legs, a short stubby tail and a large head with a relatively long snout and a tortoise-like beak. Lisowicia was apparently tuskless, like some other Triassic dicynodonts, meaning that it was entirely toothless.

Lisowicia is not only distinctive for its massive size, but also for the design of its limbs. Most dicynodonts had either fully sprawled limbs, or upright hindlimbs and sprawling forelimbs as is the case for larger dicynodonts. Uniquely for dicynodonts, and for any stem-mammal for that matter, Lisowicia had an entirely upright stance with all four limbs being fully erect, holding them directly under its body and swinging them forwards and backwards when moving, like the legs of modern large mammals and dinosaurs. These column-like limbs are no doubt an adaptation for growing to such a massive size, as such limbs are necessary to support large body sizes in land animals, and in the Late Triassic only some sauropodomorph dinosaurs rivalled it in size. This involved not only changes to the orientation of the forelimb, but also changes to the shoulders, shortening of the forearm, and completely rearranging the musculature of the forelimbs in a way no other dicynodont is known to have done. Based on the footprints of other related dicynodonts, the feet of Lisowicia would have been very elephantine in appearance. Like elephants, they would have walked on the tips of the toes with a large fleshy pad underneath the heel to cushion the feet and support its weight. Basically, almost everything about Lisowicia was built to support a massive body size.

The outside appearance of Lisowicia is unknown, and the appearance of most stem-mammals in general is poorly understood. It’s possible it was covered in scales, had naked skin, or even hair, or maybe it had some other unknown structures. If it was anything like large herbivorous dinosaurs and mammals though, it may have been mostly naked anyways.

Diet: Lisowicia was a herbivore, browsing on low and mid-level vegetation using its long snout and toothless beak to crop and chew plants. Remarkably, coprolites attributed to Lisowicia can tell us what they were eating! Lisowicia appears to have mostly preferred eating softer vegetation, along with conifers, and in some cases they even supplemented it with pieces of wood! It’s possible this was a seasonal thing, feeding on tougher, fibrous vegetation during harder times.

Behavior: Like other large herbivores, Lisowicia may have been a herd animal based on fossil sites with multiple individuals preserved together, including adults and juveniles mixed together. Whether this means Lisowicia practised parental care is uncertain though, as it is with most other stem-mammals. Stem-mammal reproduction is poorly understood, but it’s at least probable that they laid eggs, and that includes Lisowicia. Other possible line of evidence for Lisowicia being social could be that they congregated in a specific place to defecate, called communal latrines. Hundreds of coprolites are known from where Lisowicia was first found, and other dicynodonts like Dinodontosaurus are known to have performed similar behaviour, so it’s possible Lisowicia did this too.

Ecosystem: The ecosystem in Late Triassic Poland is rather unusual, as it includes a mix of plants and animals that make it difficult to pin down just how old it really was. Some suggest an older Norian age, others seem more like they’re from younger Rhaetian ecosystems, and it’s still a bit of a mystery to what was going on in this environment compared to the rest of Europe at the time. In any case, the environment where Lisowicia was found was fairly wet and lush, an “everglades-like” swamp dominated by several types of conifers, alongside gingkos, cycads, seed ferns and liverworts. Lisowicia was one of the most common animals in this environment, but it coexisted with a wide variety of other animals. One of the most notable is the predatory archosaur Smok. Smok was the arch predator in this ecosystem, and is known to have directly fed upon Lisowicia, although whether they were actively hunted by it or just scavenged upon is unknown. Smok was certainly capable of crushing even the heavyset bones of Lisowicia, with not only bite marks on its bones attributed to Smok but even broken shards of its bones identified in Smok coprolites! Other reptiles that coexisted with Lisowicia included pterosaurs, dinosauromorphs and predatory theropods similar to Coelophysis or Liliensternus, a small predatory crocodylomorph, and small diapsids, including a sphenodont (a tuatara relative), a possible archosauromorph, and even a possible choristodere. The only other synapsid around was the little mammaliaform cynodont Hallautherium, which was many times smaller than the gigantic Lisowicia. There were also temnospondyl amphibians, including a large predatory capitosaur and a small plagiosaur (one of those very flat temnospondyls with the wide heads), as well as lungfish, coelacanths and even a hybodont shark. Notably, there are no sauropodomorphs known from this ecosystem, even though they were clearly already present in Europe at this time (e.g. Plateosaurus). It’s possible that Lisowicia occupied their role as a giant herbivore in their absence, although whether it had outcompeted them or just happened to live in a habitat without sauropodomorphs and got big is yet another mystery.

Other: In addition to achieving a size and stature amongst synapsids that wouldn’t be seen again until the mammals radiated during the Cenozoic, Lisowicia was also unique for how it grew. While some stem-mammals are known to have grown rapidly as young juveniles, Lisowicia is the only one known so far to never slow down its growth rate at all until adulthood. This type of continuous rapid growth is well known in dinosaurs and mammals, but is unique to Lisowicia amongst dicynodonts. Lisowicia is one of the most unique dicynodonts ever discovered, both as the largest and one of the most derived. It was also sadly one of the last. The cause of its—and all the other Late Triassic dicynodonts’—extinction is unknown, although it was probably a victim of the end-Triassic extinction event like so many other prominent Triassic animals. Late Triassic dicynodonts were once thought to be geographically restricted, left-over relicts from the past that eventually just fizzled away as “more advanced” animals pushed them out. But now we know that they were still globally widespread even in the latest Triassic, including in Europe with advanced forms like Lisowicia. Competition with sauropodomorphs was suspected, but the discovery of the related dicynodont Pentasaurus coexisting with sauropodomorphs in South Africa suggests they were capable of at least living together, and Lisowicia is proof dicynodonts could achieve similarly gigantic proportions. Ultimately, the extinction of the dicynodonts is a mystery, but Lisowicia shows that they were still getting bigger and better than ever, even at the end of their dynasty.

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the Cut

Bajdek, P., Owocki, K. and Niedźwiedzki, G., 2014. Putative dicynodont coprolites from the Upper Triassic of Poland. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 411, pp.1-17

Dzik, Jerzy; Sulej, Tomasz; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2008). "A Dicynodont-Theropod Association in the Latest Triassic of Poland". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (4): 733–738

Fiorelli, L.E., Ezcurra, M.D., Hechenleitner, E.M., Argañaraz, E., Taborda, J.R., Trotteyn, M.J., Von Baczko, M.B. and Desojo, J.B., 2013. The oldest known communal latrines provide evidence of gregarism in Triassic megaherbivores. Scientific reports, 3, p.3348

Kowal-Linka, M., Krzemińska, E. and Czupyt, Z., 2019. The youngest detrital zircons from the Upper Triassic Lipie Śląskie (Lisowice) continental deposits (Poland): Implications for the maximum depositional age of the Lisowice bone-bearing horizon. Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology, 514, pp.487-501

NIEDŹWIEDZKI, G., GORZELAK, P. and Sulej, T., 2011. Bite traces on dicynodont bones and the early evolution of large terrestrial predators. Lethaia, 44(1), pp.87-92

Romano, Marco; Manucci, Fabio (14 June 2019). "Resizing Lisowicia bojani: volumetric body mass estimate and 3D reconstruction of the giant Late Triassic dicynodont". Historical Biology. 0: 1–6

Qvarnström, Martin; Ahlberg, Per E.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2019). "Tyrannosaurid-like osteophagy by a Triassic archosaur". Scientific Reports. 9

Sulej, T., Bronowicz, R., Tałanda, M. and Niedźwiedzki, G., 2010. A new dicynodont–archosaur assemblage from the Late Triassic (Carnian) of Poland. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 101(3-4), pp.261-269

Sulej, T. and Niedźwiedzki, G., 2019. An elephant-sized Late Triassic synapsid with erect limbs. Science, 363(6422), pp.78-80

Świło, M., Niedźwiedzki, G. and Sulej, T., 2013. Mammal-like tooth from the Upper Triassic of Poland. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 59(4), pp.815-821

#Lisowicia#Dicynodont#Triassic March Madness#Palaeoblr#Synapsid#Lisowicia bojani#Triassic Madness#Prehistory#Paleontology#Prehistoric life#Mammal-like reptile#Stem mammal

218 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love your gorgonopsid-inspired Zandalari cat forms! I have a theory that the sabertusks actually are synapsids and they are the closest living relatives to the Zandalari (like chimps/other apes and humans). Have you thought of drawing their "bear forms" based on dicynodonts such as placerias and lystrosaurus?

Holy crap so, I didn’t see this until now and I’m mad cause I love this ask. SO SORRY FOR THE LATE REPLY. I actually hadn’t considered doing that! Specially since Dicynodonts come in some many shapes and sizes seeing as they were like...the most obnoxiously prolific animals during the Permian. I think the one I would prolly adapt for it is Dinodontosaurus, cause its shaped very much like a friend.

I also like the theory! A synapsid like ancestor would make a lotta of sense. I’ll have to adapt that theory!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another #paleostream sketch

Dinodontosaurus using the communal latrine of its herd.

Communal latrines are not too uncommon among modern animals, llamas are a good example. But oh joy, we have evidence for these things from deep time as well. In this case from dicynodonts, probably Dinodontosaurus, leaving heaps of poop waaaay too large to come from just one animal.

236 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hábitos gregários de um réptil herbívoro https://ift.tt/eA8V8J Sempre se especulou que Dinodontosaurus, um dos maiores répteis herbívoros que viveram no Triássico, entre 250 e 200 milhões de anos atrás, andavam em grandes bandos para se proteger do ataque de predadores, como os répteis Prestosuchus e Decuriasuchus, parentes dos atuais crocodilos e jacaré... (on November 19, 2018 at 01:39PM)

0 notes

Text

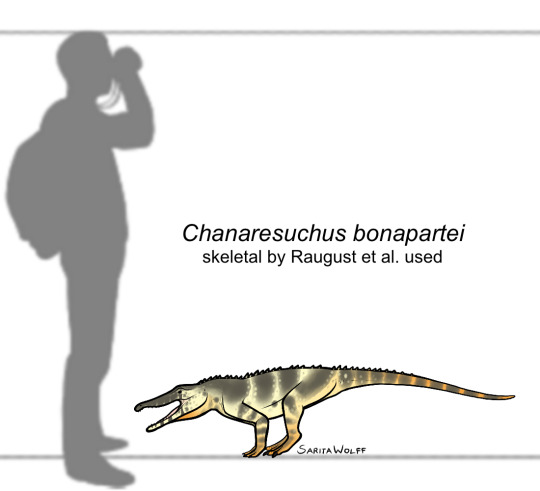

#Archovember Day 26 - Chanaresuchus bonapartei

The proterochampsians were early archosauriforms from the Triassic period. Of them, Chanaresuchus bonapartei was fairly large, living in Late Triassic Brazil. It had a long, narrow snout. Unlike many other early archosauriforms, it had very little body armour, and just a single row of small osteoderms down the back. It is hypothesized that Chanaresuchus lived a similar lifestyle to pseudosuchians and phytosaurs due to its upward facing nostrils and eyes. However, there is a distinct lack of aquatic animal fossils in the Chañares Formation, suggesting that the area was dry and arid.

Chanaresuchus would have lived alongside dicynodonts like Dinodontosaurus, cynodonts like Probainognathus and Massetognathus, silesaurs like Lewisuchus, the lagerpetid Lagerpeton, the basal dinosauriform Marasuchus, the pseudosuchians Gracilisuchus and Luperosuchus, and fellow proterochampsian Gualosuchus.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triassic invasion! Somewhere in this picture you’ll find different parts of: Batrachotomus, Blikanasaurus, Desmatosuchus, Dinodontosaurus, Hesperosuchus, Hyperodapedon, Ornithosuchus, Poposaurus, Postosuchus, Pseudochampsa, Silesaurus and Smilosuchus

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

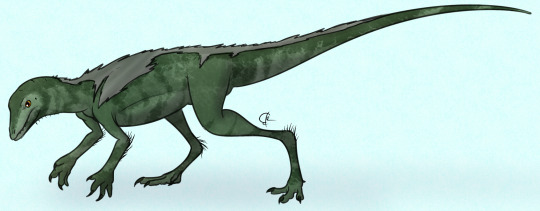

Lagosuchus talampayensis

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Rabbit Crocodile

First Described By: Romer, 1971

Classification: Dinosauromorpha

Status: Extinct

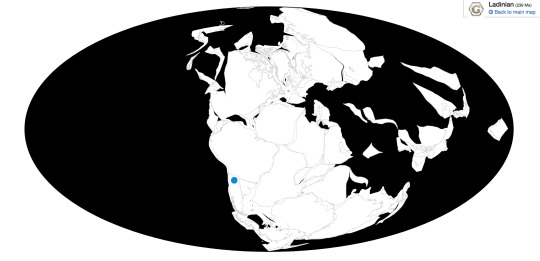

Time and Place: About 238 million years ago, in the Ladinian age of the Middle Triassic

Lagosuchus is found in the Chañares Formation of Argentina

Physical Description: Lagosuchus was an early Dinosauromorph, aka the group that includes dinosaurs and all their closest relatives. Thus, Lagosuchus is one of many early archosaurs that showcase the origins of all dinosaurs! Lagosuchus isn’t known from particularly good remains, but it does show it was a lightly built, agile animal, which was probably bipedal and spent most of its times on its toes. At about 30 centimeters in length, it was around the size of a ferret. Its legs were amazingly long, and its toes were too, giving it good speed. It had an almost-erect posture - without the open hip sockets of dinosaurs proper, it couldn’t hold its legs directly underneath its body, but it almost could. Its forelimbs are a bit more murky, though it seems likely that Lagosuchus moved on all fours most of the time, switching to two legs when it needed to move quickly from place to place. Being an early dinosauromorph, it would have had some covering of protofeathers, though how much is a bit of question.

Diet: Lagosuchus was probably an omnivore, given the fact that early dinosaurs probably came from omnivorous origins

Behavior: Lagosuchus would have been a moderately active animal - close to a warm-blooded metabolism but not quite. As such, it probably would have spent most of its time on the move, hunting for food or searching for grubs and possibly plants it could have eaten. Lagosuchus could have used its speed to run away from predators, which were very common in its environment; and, of course, running after its own food!

It is uncertain if Lagosuchus was a social animal, or if it took care of its young; but it seems likely for the latter at least.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Chañares Formation was a middle triassic microcosm of the explosion of evolution occurring in the Triassic, showcasing a wide variety of animals evolving in the aftermath of the Permian mass extinction. This was a low lying lake system, filled with horsetails, ferns, and some nearby conifer trees. It was also very warm, though not as warm as locations closer to the equator. There were many kinds of animals - large predatory pseudosuchians that would have hunted Lagosuchus such as Gracilisuchus, Luperosuchus, and Tarjadia; other Avemetatarsalians such as Marasuchus, Pseudolagosuchus, Lewisuchus, and Lagerpeton; the carnivorous almost-mammals Probainoganthus and Chiniquodon; the herbivorous almost-mammal Massetognathus; giant Dicynodont herbivores like Dinodontosaurus and Jachaleria; and finally the vaguely-crocodile-like Proterochampsids Gualosuchus, Chanaresuchus, and Tropidosuchus. A fascinating community indeed!

Other: Lagosuchus isn’t a particularly well known dinosauromorph; fossils assigned to it at one point that are well known, Marasuchus, have been given their own genus. It is possible that Lagosuchus is, thus, closer to dinosaurs in relationship than we think just on its own without evidence from Marasuchus. More studying of these fossils is necessary to come to better conclusions.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Arcucci, A.B. 1987. Un nuevo Lagosuchidae (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) de la fauna de Los Chañares (Edad Reptil Chañarense, Triasico Medio), La Rioja, Argentina. Ameghiniana 24. 89–94.

Arcucci, A., and C.A. Marsicano. 1999. A distinctive new archosaur from the Middle Triassic (Los Chañares Formation) of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19. 228–232.

Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; Andrea B. Arcucci; Claudia A. Marsicano, and Max C. Langer. 2014. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology _. 1–31.

Fiorelli, Lucas E.; Sebastián Rocher; Agustín G. Martinelli; Martín D. Ezcurra; E. Martín Hechenleitner, and Miguel Ezpeleta. 2018. Tetrapod burrows from the Middle–Upper Triassic Chañares Formation (La Rioja, Argentina) and its palaeoecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496. 85–102.

Jose, B. 1975. "Nuevos materiales de Lagosuchus talampayensis Romer (Thecodontia-Pseudosuchia) y su significado en el origen de los Saurischia: Chañarense inferior, Triásico medio de Argentina." Acta Geológica Lilloana. 13 (1): 5–90.

Kent, Dennis V.; Paula Santi Malnis; Carina E. Colombi; Oscar A. Alcober, and Ricardo N. Martínez. 2014. Age constraints on the dispersal of dinosaurs in the Late Triassic from magnetochronology of the Los Colorados Formation (Argentina). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111. 7958–7963.

Marsicano, C. A., R. B. Irmis, A. C. Mancuso, R. Mundil, F. Chemale. 2016. "The precise temporal calibration of dinosaur origins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (3): 509–513.

Nesbitt, S.J. 2011. "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 189.

Romer, A. S. 1971. "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. X. Two new but incompletely known long-limbed pseudosuchians". Breviora. 378: 1–10.

Romer, A. S. 1972. "The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptile fauna. XV. Further remains of the thecodonts Lagerpeton and Lagosuchus". Breviora. 394: 1–7.

Palmer, D., ed. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 97.

Paul, G. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster.

Perez Loinaze, V. S., E. I. Vera, L. E. Fiorelli, J. B. Desojo. 2018. Palaeobotany and palynology of coprolites from the Late Triassic Chañares Formation of Argentina: implications for vegetation provinces and the diet of dicynodonts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 502: 31 - 51.

Pontzer, H., V. Allen, J. R. Hutchinson. 2009. "Biomechanics of Running Indicates Endothermy in Bipedal Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 4 (12): e7783.

Rogers, R.R.; A.B. Arcucci; F. Abdala; P.C. Sereno; C.A. Forster, and C.L. May. 2001. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16. 461–481.

Sereno, P. C., A. B. Arcucci. 1994. "Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (1): 53–73.

#Lagosuchus#Lagosuchus talampayensis#Dinosauromorph#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#prehistory#Outside Saurischia & Ornithischia#Triassic#South America#Omnivore#Mesozoic Monday

215 notes

·

View notes