#dhrupad

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Audio

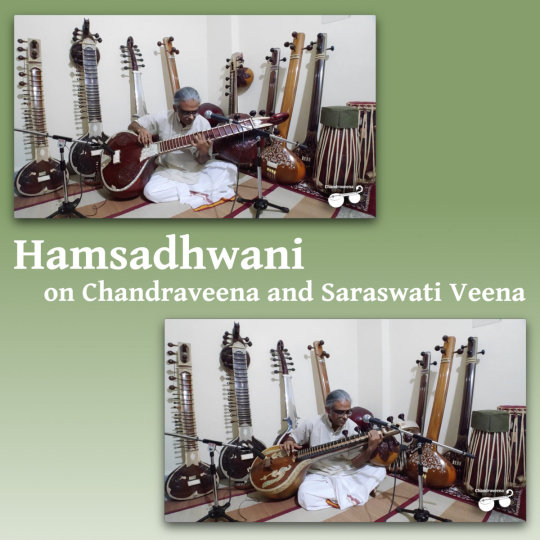

Listen/purchase: Hamsadhwani on Chandraveena and Saraswati Veena by S Balachander

Hamsadhwani on Chandraveena and Saraswati Veena ~by S Balachander

0 notes

Photo

There is nothing in American culture that is old, not in comparison to Asia. Dhrupad existed pre-C.E.

Fayiaz Wasifuddin #Dagar performing the oldest known form of Hindustani classical #music known as #dhrupad, a search for the original frequency through a series of escalating modulations. A mystical experience if you have the patience to listen through a 90 minute performance. Early references can be found in #sanskrit texts dating back to 200BC. Live recording on SoundCloud: https://goo.gl/7pcq0 (at New Delhi, India)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dagar Brothers — Berlin 1964 (Black Truffle)

Oren Ambarchi’s Black Truffle label has long been a source for challenging, rewarding music across genres from contemporary composition and free jazz to Thai mouth organ and wah-wah’d out solo bass recordings. Now it is becoming a great resource for Dhrupad music as well. Following up archival recordings of the recently departed Amelia Cuni and rudra veena virtuoso Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar is a revelatory set of lost recordings from the Dagar Brothers, two of the most important figures in establishing the documentation and preservation of this important vocal art form.

Dhrupad is the oldest form of Hindustani classical music, characterized by extensive, drawn-out improvisations. Within this lineage, the Dagar family, which includes the Dagar Brothers, their younger siblings and fellow vocal duo Zahiruddin Dagar and Faiyazuddin Dagar, the aforementioned Z.M. Dagar and his son Bahauddin Dagar, is not just a family, but an institution. Historically, the Dagars were court musicians, and to give a sense of how important the Dagar family is to Dhrupad, there are four styles of court (or darbārī) Dhrupad, and one of them is known simply as the Dāgar vānī. Ustad Nasir Moinuddin (1919-1966) and Ustad Nasir Aminuddin Khan (1923-2000) were born into this lineage at a critical period, coming of age as India broke free from centuries of British colonial rule. British colonialism had upended Indian court music and, starting in the 19th century, Dhrupad had begun to decline in favor of different styles of Hindustani classical music such as Khyal and Thumri. The development of recording technology further displaced the music from its regal context, as the music was now being presented to a much larger audience than the courts would have allowed. Indian classical music was extensively recorded on 78 rpm records from the very beginning, but the limited timeframe that the records allowed made documenting the lengthy Dhrupad music practically impossible. In the aftermath of decolonization, Dhrupad was in danger of disappearing entirely, and it was in this context that the Dagar Brothers took initiative to preserve their family tradition.

Crucial to this mission was the rise of long-playing records in the 1950s and 1960s, which provided much more space for the expansive improvisations of the Dagar Dhrupad. There were also a number of record labels emerging around this time, such as Ocora and Lyrichord, which were dedicated to producing ethnographic recordings without consideration for commercial appeal. In the mid-1960s the Dagar Brothers made the very first Dhrupad record for the EMI-Odeon label, and went on a tour of Europe organized by the eccentric French historian Alain Daniélou. Daniélou recorded the Dagar Brothers in Berlin during this tour, which remained unreleased until now due to the tape abruptly cutting out just before the brothers finished their performance of Raga Jaijavanti. Fifty years later that recording, along with a live recording made in Berlin around the same time, is now being released by Black Truffle.

The Dagar Brothers participated in these recordings with the intention of documenting and preserving a musical tradition in danger of disappearing (and promoting it to a new audience), but this doesn’t make them any less singular as artists. Perhaps the most striking thing about these releases is the intensity of the brothers’ performances, which ought to single handedly dispel any preconceptions of Indian Classical music as new-agey “chill-out” music. On the performance of Rāga Miyān kī Todī from the live recording, that intensity is present from the very beginning and doesn’t let up during the nearly 40 minute run time. The Dagar Brothers sing in beautiful droning overtones, but when the energy hits peak levels their vocal ornamentations sound like deep, commanding shouts, all perfectly on rhythm. The court music context may make one expect otherwise, but this is deeply powerful, trance-inducing music.

In the present day, Dhrupad is often associated with what is now known as drone music. La Monte Young, who is perhaps more associated with drone than any other composer, famously studied under Pandit Pran Nath, as did Terry Riley, and those two composers helped set the stage for future works exploring long tones. But what makes Dhrupad music so important in understanding the “Western” experimental music it paved the way for isn’t just the drone, but the way in which its practitioners showed the endless sonic possibilities of such seemingly “static” music. There are even some moments of vocal overlap between the two brothers that are somewhat reminiscent of the phasing techniques utilized by Phill Niblock. But even beyond its importance to experimental music, these recordings are a testament to the living, breathing power of this ancient vocal art form, and the power of music in moving both the mind and the body. The voice, after all, is the original instrument.

by Levi Dayan

#dagar brothers#berlin 1964#black truffle#levi dayan#albumreview#dusted magazine#Dhrupad music#india#drone

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

only ensemble ever this is not a joke

#desi tag#desiblr#ponniyin selvan#like veera raja veera made me write a whole ass asoiaf fic with my own house like the#inspo hit#anyways#VEERA RAJA VEERA BANGER 💪💪💪#Spotify#-> 🎧 tag

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

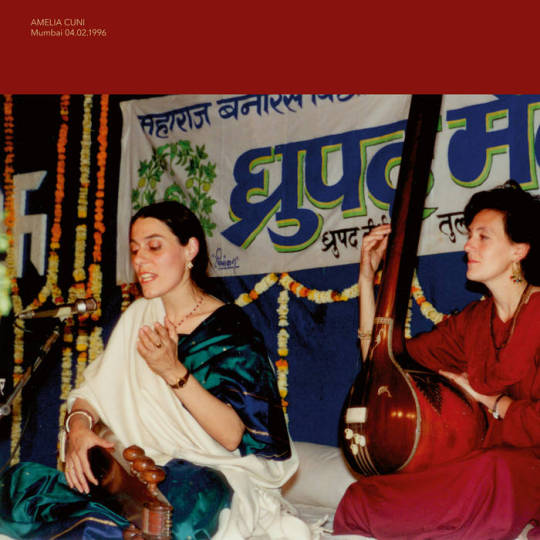

r.i.p. Amelia Cuni

(▶︎ Mumbai 04.02.1996 | Amelia Cuni | Black Truffleから)

Mumbai 04.02.1996 by Amelia Cuni

Following on from the stunning recording of her 1992 performance at the Berlin Parampara Festival (BT079), Black Truffle is pleased to continue its documentation of the work of Berlin-based Italian singer Amelia Cuni, one of the great contemporary exponents of dhrupad, the oldest surviving style of North Indian classical vocal music. Beautifully recorded in concert at Vishweshwarayya Hall, Mumbai. 04.02.1996 presents expansive performances of three ragas stretching across four sides and almost one and a half hours of music. Beginning with the serene Raga Lalit, Cuni dwells for over twenty-five minutes on its opening alap movement, accompanied only by tanpura, her limpid yet full-bodied voice moving from graceful exposition in free tempo to increasingly rhythmically active variations, gradually spiralling upward in register. She is then joined by master pakwahaj player Manik Munde for the raga’s dhrupad and dhamar sections, the resonant tone of the drum and his constant invention with the complex 14-beat cycle serving as the perfect accompaniment for Cuni’s ecstatic melodic developments. On the more solemn Raga Bhairav, Cuni’s alap, again stretching out over a whole side, is particularly notable for its powerful held notes and mastery of microtonal movement of pitch. After Munde returns for another rhythmically intricate dhamar movement, the record ends with the buoyancy of the Raga Alhaiya Bilaval, whose mode has, for the Western listener, an unmistakably ‘major’ quality. The rapturous applause that greets the performance is reflected in a remarkable selection of press clippings contemporary with the recording, which demonstrate Cuni’s success with Indian critics. Arriving in a gorgeous gatefold featuring stunning colour photographs of Cuni taken by legendary Australian fashion photographer Robyn Beeche (who resided in India from the early 90s), Mumbai. 04.02.1996 is a document of indescribable beauty and a moving testament to music’s ability to cross national and cultural borders. クレジット2022年9月30日リリース

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@dhrupad this account is literally baghdad's library, stunning account! plz comeback

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

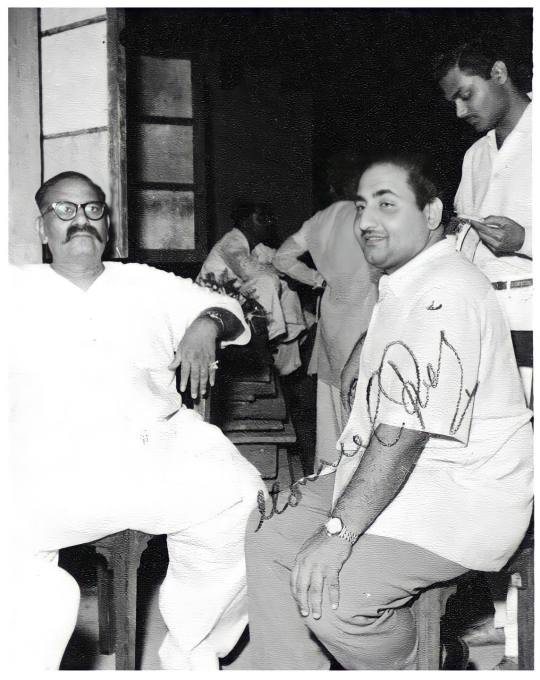

Remembering Ustad #BadeGhulamAliKhan Saab on his 56th death anniversary (25/04/1958). Bade Ghulam amalgamated the best of three traditions into his own Patiala-Kasur style: the Behram Khani elements of Dhrupad, the gyrations of Jaipur, and the behalves (embellishments) of Gwalior. Here is a rare photograph of Mohammed Rafi with Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. What are your favourite Bade Ghulam Ali Khan songs?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

miss the girlies who ran @dhrupad and @pyotra so fucking bad

#they went inactive long before i found out abt them but god 😞#a girl could only wish to be that cool#notebook

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Ambient Soundscape and Ancient Dhrupad Singing

A ethereal, dreamy, mystical journey that is sure to take you to somewhere magical. I have done spiritual energy work for many years and this transcendental piece has performed better than almost any other. This is very lucid invoking piece of music that can be a catalyst to an altar state of being, transcending time and space. Monsoon Point refers to the exact point of awakening .

#music#spiritual#meditation#energy work#energy healing#transcendental meditation#transcendental#mystical#India#dreamy#ethereal#Youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

16 for the Spotify Wrapped game pls!

Veera Raja Veera by A.R. Rahman, from the Ponniyin Selvan OST.

(ask me about my Spotify Wrapped!)

#inbox#q: anon#film: ponniyin selvan ii#see now this is how i KNOW i am unwell. still haven't watched either part but i can tell the exact way this made it onto the playlist#and it was bc of that 'rating every version of Veera Raja Veera' academic essay sh*t i did a while back. which i should link in the#comments if i can find it but uh. i saw it at number 16 and went ah. hello Kollywood hello Rahman#as expected tbh. why the playlist doesn't have MORE Rahman is mind-boggling these are the times i believe some of it is rigged#spotify wrapped

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday Morning Gandharva Veda Meditation Music

‘Rag Jaunpuri - Alap, jor and jhala - Dhrupad Vocal’ by Samvad is on

0 notes

Text

Price: [price_with_discount] (as of [price_update_date] - Details) [ad_1] This work aims to address the historical development of the great Indian raga tradition, enhanced by computational approaches, and to use computational strategies to analyze aspects of contemporary Hindustani classical music (HCM). It is divided into two parts with Part 1 focusing on the history and aesthetics of HCM and Part 2 covering its computational aspects. The historical development of HCM in the ancient, medieval and modern periods; its terms and genre; and its Khayal gharanas are covered in Part 1. The subtopics include essential concepts such as raga, tala, shruti, thaat, gharana, khayal, dhrupad, thumri, tappa, etc. Part 2 covers the state-of-the-art in computational musicology, raga analysis and song analysis using statistics. The subtopics include statistical modeling, inter onset interval, note duration analysis, pitch movement between the notes, rate of change of pitch (pitch velocity) and probabilistic analysis of musical notes. The author concludes the work with reflecting on the lives of a few renowned musicians and musicologists with an account of hilarious moments taken from their lives to excite the reader to know more about HCM. This book would be useful for musicians, musicologists, researchers in music history, aesthetics, computational musicology, and advanced undergraduate and postgraduate students of music and musicology. Publisher : Sanctum Books; First Edition (15 April 2021) Language : English Hardcover : 171 pages ISBN-10 : 8194783003 ISBN-13 : 978-8194783008 Item Weight : 788 g Dimensions : 23 x 2 x 15 cm [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

These are stories of women facing poverty, violence, and oppression,” Vafadari told MWN, her voice trembling with conviction. “But it’s also about their resilience, how they reclaim their voices despite everything. Sacred music isn’t just about tradition; it breathes, it lives. When we perform, something magical happens. Women from different worlds, different languages, different wounds, suddenly recognize each other. That’s transcendence.”

The festival, long celebrated for bridging spiritual traditions, emerged as a space where women’s stories, often suppressed, were amplified in a chorus of defiance and hope.

By Firdaous Naim May, 20, 2025

Yesterday, leading the ensemble “4Femmes,” mezzo-soprano and composer Ariana Vafadari and her troop delivered an unforgettable performance.

Fez – Fez’s ancient Jnan Sbil garden became a stage for a powerful women’s rights musical manifesto at the 28th edition of the Fez World Sacred Music Festival.

Yesterday, leading the ensemble “4Femmes”, mezzo-soprano and composer Ariana Vafadari and her troop delivered an unforgettable performance. She ignited a conversation on the global struggle for women’s rights through the transcendent power of sacred music.

In an exclusive interview with Morocco World News (MWN), Vafadari shared the emotional weight behind her return to Fez, a city she calls her “spiritual home.”

Moroccan handicrafts shopping

The festival, known for bridging cultures through sacred sounds, provided the perfect setting for her latest work, a fusion of ancient myth and modern resistance.

A project born from pain and hope

For Vafadari, 4Femmes is not just a musical piece. It’s a cry against the erosion of women’s rights worldwide. Inspired by real testimonies from Afghanistan, Iran, and beyond, the project reimagines the myth of Medea, transforming her from a tragic figure into a symbol of defiance.

“These are stories of women facing poverty, violence, and oppression,” Vafadari told MWN, her voice trembling with conviction. “But it’s also about their resilience, how they reclaim their voices despite everything. Sacred music isn’t just about tradition; it breathes, it lives. When we perform, something magical happens. Women from different worlds, different languages, different wounds, suddenly recognize each other. That’s transcendence.”

The lyrical monologues, penned by Atiq Rahimi (award-winning author and filmmaker), knot together personal narratives into a collective plea for justice. “Medea refuses to be a bargaining chip,” Vafadari explained. “She escapes her fate. That’s what we’re singing about, women who refuse to be silenced.”

Sacred sisterhood

For Marianne Svasek, a Dutch singer specializing in the rigorous tradition of Dhrupad (an ancient form of Indian classical music), joining 4Femmes was a revelation. Known for her solo performances, she found unexpected freedom in this cross-cultural collaboration.

“Normally, I sing classical music, and it’s very strict,” Svasek admitted in an interview with MWN.

“But here, collaborating with different styles and these incredible female voices, I discovered another side of myself. It’s not just about technique; it’s about emotion, about truth.”

When asked how she channeled the project’s heavy themes, stories of war, displacement, and survival, Svasek paused, then replied: “It feels different, deeper, singing with women about women’s lives. You can’t just perform these stories; you have to live them in the music. There’s a responsibility in that. And in Fez, with its sacred energy, it becomes even more powerful.”

Svasek described performing at the festival’s opening night as electrifying, but she was especially moved by their garden performance. “The city feels alive, like India’s sacred spaces. Singing surrounded by nature, it’s a different kind of magic.”

Vafadari’s vision for a global sisterhood

The seeds of 4Femmes were planted years ago when Vafadari met members of the Asian University for Women in Bangladesh, an institution offering free education to women from across Asia.

“Their stories stayed with me,” she said. “Music creates bridges, between eras, spiritualities, and people. That’s what we’re doing here.”

Trained at the Paris Conservatory yet deeply rooted in her Persian Zoroastrian heritage, Vafadari’s artistry defies categorization. Her compositions blend Persian classical music, jazz, and electronic soundscapes, creating what she calls “sonic epics”, where ancient wisdom speaks to modern struggles.

“Fez is the perfect place for this,” she reflected. “The festival isn’t just about preserving traditions; it’s about letting them evolve, letting them speak to today’s world.”

As 4Femmes left the stage, the echoes of their performance lingered. In a time when women’s rights are under siege globally, Vafadari’s message was clear:

“Sacred music is not just prayer, it is protest. And when women sing together, the world listens.”

Women’s rights remain a pressing global struggle, as gender inequality, violence, and systemic oppression continue to silence voices across cultures. Yet, in the face of adversity, women have turned to art, storytelling, and music as tools of resistance, transforming pain into power and isolation into solidarity.

This spirit of resilience found a profound stage at the Fez Festival of World Sacred Music, where artists like Ariana Vafadari and her ensemble 4Femmes wove these urgent narratives into the fabric of sacred sound. The festival, long celebrated for bridging spiritual traditions, emerged as a space where music confronted injustice, where ancient hymns carried modern cries for freedom, and where women’s stories, often suppressed, were amplified in a chorus of defiance and hope.

#Morocco#Fez#Fez World Sacred Music Festival#4Femmes#Ariana Vafadari#Atiq Rahimi#Marianne Svasek#Women in music

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Indian Music Is One of the Oldest in the World!

youtube

#HindustaniMusic #IndianClassicalMusic #Raga #Khayal #Dhrupad #Thumri #ClassicalVocal #IndianMusicTradition #Sitar #Tabla #Tanpura #RaagYatra #HindustaniVocal #GharanaStyle #IndianMusicLovers

1 note

·

View note