#development and membership committee

Text

Via NasAlSudan

Learn about the Sudanese revolution, the significance of December 19, and a legacy of resistance and resilience.

Join our call to action today and everyday during Sudan Action Week.

December 19 2023

Transcript:

Breaking it down

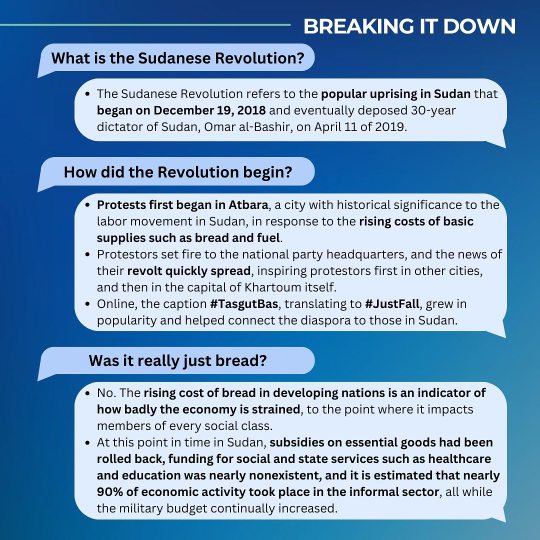

What is the Sudanese Revolution?

The Sudanese Revolution refers to the popular uprising in Sudan that began on December 19, 2018 and eventually deposed 30-year dictator of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, on April 11 of 2019.

How did the Revolution begin?

Protests first began in Atbara, a city with historical significance to the labor movement in Sudan, in response to the rising costs of basic supplies such as bread and fuel.

Protestors set fire to the national party headquarters, and the news of their revolt quickly spread, inspiring protestors first in other cities, and then in the capital of Khartoum itself.

Online, the caption #TasgutBas, translating to #JustFall, grew in popularity and helped connect the diaspora to those in Sudan.

Was it really just bread?

No. The rising cost of bread in developing nations is an indicator of how badly the economy is strained, to the point where it impacts members of every social class.

At this point in time in Sudan, subsidies on essential goods had been rolled back, funding for social and state services such as healthcare and education was nearly nonexistent, and it is estimated that nearly 90% of economic activity took place in the informal sector, all while the military budget continually increased.

Transcript:

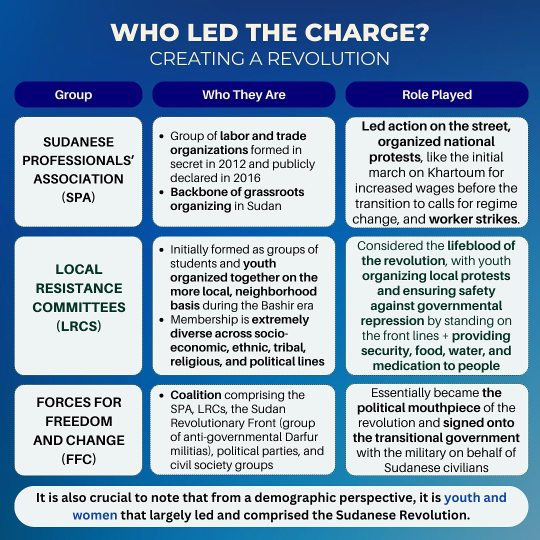

Who led the charge? Creating a revolution

Group: Sudanese Professional's association (SPA)

Who they are:

Group of labor and trade organizations formed in secret in 2012 and publicly declared in 2016

Backbone of grassroots organizing in Sudan

Role played:

Led action on the street, organized national protests, like the initial march on Khartoum for increased wages before the transition to calls for regime change, and worker strikes.

Group: Local Resistance Committees (LRCS)

Who they are:

Initially formed as groups of students and youth organized together on the more local, neighbourhood basis during the Bashir era

Membership is extremely diverse across socio-economic, ethnic, tribal, religious, and political lines

Role played:

Considered the lifeblood of the revolution, with youth organizing local protests and ensuring safety against governmental repression by standing on the front lines + providing security, food, water, and medication to people

Group: Forces for freedom and change (FFC)

Who they are:

Coalition comprising the SPA, LRCS, the Sudan Revolutionary Front (group of anti-governmental Darfur militias), political parties, and civil society groups

Role played:

Essentially became the political mouthpiece of the revolution and signed onto the transitional government with the military on behalf of Sudanese civilians

It is also crucial to note that from a demographic perspective, it is youth and women that largely led and comprised the Sudanese Revolution.

Trabscript:

How did the revolution succeed?

01. Learning from the Past

Following the Arab Spring wave, Sudan also attempted a revolution in September of 2013

Civilians faced violent crackdowns within the first three days of protest. 200 killed, 800+ arrested

Activists were deterred from mobilization + felt a lot of guilt at the massive loss of life and spent the next 5 years grounding themselves in the study of nonviolent theory and action

02. Building a Movement

Coalition Building and People Power

Diversification of the reach of the movement to make sure all sectors of Sudani society were represented

Decentralization of Activism

Past revolutions in 1964 and 1985 were concentrated in the labor movement and educational elites in Khartoum

This time, experienced nonviolent activists trained those in the capital and ensured ethnic, religious, and tribal diversity

Newly trained activists then taught others locally across the Sudanese states

Transcript:

Why december 19?

On December 19, 1955, the Sudanese parliament unanimously adopted a declaration of independence from the Anglo-Egyptian colonial power.

The declaration went into effect on January 1, 1956, which is why Independence Day is officially January 1, but December 19 is when the Sudanese people were truly liberated from colonial rule.

The flag shown is Sudan's independence flag. The blue is for the Nile, the yellow for the Sahara, and the green for the farmlands.

The current Sudanese flag was adopted in 1970, with the colors used being the Pan-Arab ones.

During the 2019 revolution, protestors often carried the independence flag instead as a form of resistance to the narrative of an exclusive Pan-Arab Sudanese identity.

December 19 is ultimately a tribute to Sudanese strength and resilience. It honors our independence and revolutionary martyrs - not just those of the 2019 revolution, but the democratic revolutions of 1964 and 1985 as well.

Transcript:

Why is the revolution ongoing?

The goal was never just the fall of a dictator. The goal was, and is, to build a better Sudan, one free from military rule. One with equal opportunities for everyone, with economic prosperity and safety and security - the key principles of freedom, peace, and justice that the revolution called for.

Today, though, before we rebuild Sudan, before we free it from foreign interests and military rule and sectarianism, we need to save it. Each day that passes by with war waging on is one where more civilians are killed. More people are displaced. More women are raped. More children go hungry. To live in the conflict zones in Sudan right now - whether that be Khartoum, Darfur, Kordofan, or now, Al Gezira, is to be trapped in a never-ending nightmare, a fight for survival. And to live elsewhere in Sudan is to wonder whether you're next.

Sudan Action Week calls on you to educate yourself and others about Sudan, and then to help the Sudanese people save it, because we can no longer do it alone.

Transcript:

What can you do? Uniting for Al Gezira and North Darfur

As we witness the unfolding events in Al Gezira and North Darfur, the communities of Abu Haraz, Hantoub, Medani, El Fasher, and many others are reaching out for assistance. Sudanese resilience persists to this day, with individuals on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok seeking and providing guidance on transportation services, medical care, food, shelter, protection, safe zones, operational markets, and more. This isn't new for the Sudanese community. A legacy of unity emerged, notably during the 2019 revolutions, where nas al Sudan [the people of Sudan], both within the nation and in the diaspora, rallied together to support each other online. Beyond merely sharing stories on social media, this was about strengthening collective action, enhancing mobilizations, and building a resilient community rooted in solidarity. The essence of the Sudanese community lies in people supporting people, notably during the uprising in 2018 and following the events of April 15th, 2023

Swipe to see how you can help.

Transcript:

What can you do?

This week, on a day nearly mirroring Sudanese Independence and the popular 2018 uprising, Sudanese resilience endures as war follows nas al Sudan to Al Gezira and again in North Darfur. Our call to action this week is not just to share; it's a collective effort to uplift one another.

Share Resources:

If you have access to resources that can help such as transportation services, medical assistance, food, shelter, etc., please comment below.

Community Requests:

If you are in Al Gezira or North Darfur and require specific support, please comment on your needs

Connect Individuals:

For those unable to share resources directly, help amplify requests by sharing this information within your personal networks. Your connection may lead to support from individuals who can assist.

Spread the Word:

Share this call to action on your social media platforms to broaden the reach and encourage more people to contribute.

Transcript:

Hanabniho

حنبنيهوا

[We will rebuild]

#keepEyesOnSudan

#SudanActionWeek

924 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five Things Amy Lowell Said

OTW's donation form is up and running again!

And in today's Five Things, we chat with Amy Lowell, who works in the Development & Membership Committee, which handles donations and thank you gifts. Learn more about what this is like and also why her Christmases are particularly fannish: https://otw.news/1b494a

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTW Elections 2023: Become a Member!

Thank you for your interest in participating in our annual election! As you might already know, the Organization for Transformative Works holds yearly elections every August to appoint new directors to its Board. If you’re interested in supporting your favorite candidates and their causes, you can become eligible to vote by becoming a member of the OTW. The process to become eligible to vote is straightforward, but there are time limitations – read on to learn more about how to become a member of the OTW.

We welcome everyone to join the OTW as a member and vote in our elections. The membership fee amounts to US$10 and must be paid in a single donation. Members who pay the membership fee by June 30 are eligible to vote in August of the same year. Please note that volunteering for the OTW does not make you eligible to vote; you must be a paid member.

Please remember your donation is processed in the US Eastern time zone. Your donation must be registered by June 30, 7:59 PM (19:59) Eastern time for you to be eligible to vote in the next election – if the receipt shows a date and time later than this, you are not eligible to vote that year (though you will be able to vote next year!). Don’t forget to check out our Timeline for more important dates!

There are multiple ways you can donate – credit card, Paypal account, or, if you’re based in the U.S., personal check. Remember, your donation must be recorded by June 30; if you mail a check, make sure to account for the time needed for the check to be mailed and registered.

Click here to join the OTW and become a voting member!

We only need the information linked with your payment method to confirm you’re an individual and not any other legal body, because only individuals are allowed to vote for the Board of Directors. Rest assured, member's personal data is used in very limited circumstances, such as sending out receipts, ballots, and thank-you gifts. Only a small handful of people on the Development & Membership Committee have access to this information.

If you’re not sure if your donation was processed by the deadline, or you have general inquiries about your eligibility to vote, please get in touch with our Development and Membership Committee by using the contact form on our website and selecting “Is my membership current/Am I eligible to vote?”.

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would now like to deal with two extremes, two obsessions, on the question of workers' democracy that were to be noted in some of the discussion articles in Pravda.

The first extreme concerns the election principle. It manifests itself in some comrades wanting to have elections "throughout." Since we stand for the election principle, let us go the whole hog in electing! Party standing? What do we want that for? Elect whomever you please. That is a mistaken view, comrades. The Party will not accept it. Of course, we are not now at war; we are in a period of peaceful development. But we are now living under the NEP. Do not forget that, comrades. The Party began the purge not during, but after the war. Why? Because, during the war, fear of defeat drew the Party together into one whole, and some of the disruptive elements in the Party were compelled to keep to the general line of the Party, which was faced with the question of life or death. Now these bonds have fallen away, for we are not now at war; now we have the NEP, we have permitted a revival of capitalism, and the bourgeoisie is reviving. True, all this helps to purge the Party, to strengthen it; but on the other hand, we are being enveloped in a new atmosphere by the nascent and growing bourgeoisie, which is not very strong yet, but which has already succeeded in beating some of our co-operatives and trading organisations in internal trade. It was precisely after the introduction of the NEP that the Party began the purge and reduced its membership by half; it was precisely after the introduction of the NEP that the Party decided that, in order to protect our organisations from the contagion of the NEP, it was necessary, for example, to hinder the influx of non-proletarian elements into the Party, that it was necessary that Party officials should have a definite Party standing, and so forth. Was the Party right in taking these precautionary measures, which restricted "expanded" democracy? I think it was. That is why I think that we must have democracy, we must have the election principle, but the restrictive measures that were adopted by the Eleventh and Twelfth Congresses, at least the chief ones, must still remain in force.

The second extreme concerns the question of the limits of the discussion. This extreme manifests itself in some comrades demanding unlimited discussion; they think that the discussion of problems is the be all and end all of Party work and forget about the other aspect of Party work, namely, action, which calls for the implementation of the Party's decisions. At all events, this was the impression I gained from the short article by Radzin, who tried to substantiate the principle of unlimited discussion by a reference to Trotsky, who is alleged to have said that "the Party is a voluntary association of like-minded people." I searched for that sentence in Trotsky's works, but could not find it. Trotsky could scarcely have uttered it as a finished formula for the definition of the Party; and if he did utter it, he could scarcely have stopped there. The Party is not only an association of like-minded people; it is also an association of like-acting people, it is a militant association of like-acting people who are fighting on a common ideological basis (programme, tactics). I think that the reference to Trotsky is out of place, for I know Trotsky as one of the members of the Central Committee who most of all stress the active side of Party work. I think, therefore, that Radzin himself must bear responsibility for this definition. But what does this definition lead to? One of two possibilities: either that the Party will degenerate into a sect, into a philosophical school, for only in such narrow organisations is complete like-minded-ness possible; or that it will become a permanent debating society, eternally discussing and eternally arguing, until the point is reached where factions form and the Party is split. Our Party cannot accept either of these possibilities. This is why I think that the discussion of problems is needed, a discussion is needed, but limits must be set to such discussion in order to safeguard the Party, to safeguard this fighting unit of the proletariat, against degenerating into a debating society.

In concluding my report, I must warn you, comrades, against these two extremes. I think that if we reject both these extremes and honestly and resolutely steer the course towards internal Party democracy that the Central Committee set already in September of this year, we shall certainly achieve an improvement in our Party work.

The Party's Tasks. J. V. Stalin, 1923

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence appointed Patron of the International Maritime Rescue Federation

Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, the husband of Her Royal Highness the Princess Royal, has been named the Patron of the International Maritime Rescue Federation (IMRF), the world’s leading organisation for developing and improving maritime search and rescue (SAR) capabilities.

He replaces Sir Efthimios Mitropoulos, the Secretary-General Emeritus of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), who stepped down earlier this year, having been in the role since 2012.

Sir Tim holds a distinguished career as part of the UK’s Royal Navy, serving from the early 1970s upon leaving the University of Durham before retiring in 2010. His strong interest and background in maritime led to him being appointed to the Governing Council of the UK’s Royal National Lifeboat Institution in 2004, then to the Trustee Board and Chairman of the Operations Committee in 2011. He later became Deputy Chairman of the RNLI Board and, on retirement from the Board in 2020, became a Vice President.

As Patron, Sir Tim will become a leading voice and advocate for the work of the IMRF and maritime SAR organisations around the world, which continues to play a critical role in protecting and saving lives at sea.

“It is an honour to be appointed the new Patron of the IMRF, and I look forward to working closely with the organisation, its members and SAR personnel worldwide to advance the cause of safety at sea,” Sir Tim said.

Speaking about the appointment, Jacob Tas, Chair of the IMRF, said, “I am delighted that Sir Tim Laurence has accepted our invitation to become the new Patron of the IMRF. His tenure at the UK’s Royal Navy and his dedication to public service means he will be a fantastic supporter of the IMRF’s global work and the critical importance of maritime SAR organisations globally.”

Caroline Jupe, Chief Executive Officer of the IMRF, said, “The IMRF and its membership continue to play a major role in the maritime SAR sector as we look to prevent loss of life in the world’s waters. I am thrilled that Sir Tim has agreed to join the IMRF community as our new Patron, and I’m excited to see how we can work together to bolster the maritime SAR sector, tackle critical issues facing the sector and advance key initiatives to improve the lives of those working in a challenging industry.”

In addition to its work providing guidance and best practice for SAR operations, the IMRF has also launched a number of critical initiatives to improve the wellness and efficiency of SAR personnel, including its #WomenInSAR campaign, its #SARyouOK? mental health initiative and its #FutureSAR climate change awareness campaign.

#yaaaay#a tim patronage#ffs charles just make him a working royal already#tim laurence#timothy laurence#tim does stuff#british royal family#brf#princess anne#princess royal

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under capitalism, where part of the value of every product goes to the employer as profit, the workers in any single enterprise, or in a whole industry, can force the employers to raise their wages or otherwise to improve their conditions by direct action. If strikes are successful, wages rise at the expense of profits, which is satisfactory to the workers though unsatisfactory to the employers. When, however, as in the U.S.S.R. today, the whole of the means of production are owned and controlled by public bodies in the public interest, a strike by the workers in any factory or industry for higher wages can only react to the disadvantage of the working population itself. For, by a strike, production is restricted. And this is contrary to the public interest in a community in which every extra product is required and is utilized. A strike, therefore, is to the disadvantage of the workers of the Soviet community as a whole.

The method of fixing wages by means of strikes in a Socialist country is highly undesirable, for it is no longer possible for any workers to raise their wages at the expense of employers’ profits. If, as a result of a strike, higher wages are won, then they are won at the expense of the general fund which goes to paying the wages of all citizens. If the coalminers of the U.S.S.R. strike today for more wages, they are in fact fighting to force the Government to give to them what otherwise it would be dividing up among other workers. Strikes, then, in such conditions, can only represent sectional demands against the whole community, and in themselves are contrary to the general interest because they restrict production.

In a diary of a visit of a few weeks’ duration to the U.S.S.R., Sir Walter Citrine has said that “it was too much to assume a complete identity of interest between the director and the workers. The director was concerned with efficiency and output, and the worker with the amount he could earn, and the conditions under which it was earned” (Search for Truth in Russia, p. 129). And, in a later passage, he says that “liberty of association and the right to strike are the essential features of legitimate trade unionism” (p. 361).

It is clear, from what has been said here, that Sir Walter’s estimation of the relations between director and worker in the Soviet factory is based on a lack of understanding of the situation. Sir Walter ignores the unique fact that the Soviet director, as part of his job, is responsible for increasing the welfare of the workers. He ignores the fact that the workers, no longer working for an employer who takes part of their product in the form of profit, know that everything they produce is distributed to the community — that is, to themselves. Finally, he ignores the also important fact that, under such conditions as these, a strike is an attack by a small minority on the economic resources of the whole community; and at the same time, by holding up production, reacts to the disadvantage of all citizens.

As to the other matter — freedom of association — no other State in the world has ever given the encouragement to trade unionism which has been given in the U.S.S.R. We have already seen how the young Soviet State, in its first months of existence, made the trade union committees the official representative bodies of the workers in all industrial enterprises, with powers of control over the management. This was a tremendous stimulus to trade union development, as is shown by the figures of trade union membership. In October 1917, at the time when the Soviets seized power, there were 2 million trade unionists. By 1928 this figure had increased to 11 million, and was 18 million in 1934. No other country can show such figures, and it is absurd to suggest that the U.S.S.R. has ever done anything but encourage, to the greatest possible extent, the organization of the workers in trade unions.

Pat Sloan, Soviet Democracy, 1937

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posted on July 29, 2022 by Jean-Carl Elliott

Growing the IWW isn’t just about increasing the size of our membership, it’s also about increasing its depth. Part of “building the new world in the shell of the old” entails developing the people who will be able to run it once it’s built. We aren’t simply signing up workers from our jobs and industries for their dues. We are signing them up to make them into Wobblies! Being a Wobbly means that we know where we stand in the class struggle, we know the lessons learned from those who struggled before us, and we stand in solidarity with other Wobblies who are continuing the struggle today. Being a Wobbly isn’t just about having a Red Card, it’s about leveling each other up! I’ve met so many Wobblies throughout the years who sign a Red Card and then don’t know what to do next. Without a sense of direction, our members tend to gravitate towards other activist groups or they leave the union altogether. We want to keep workers involved and to give them a sense of purpose in the IWW. This article will be part of a series on how to level up your IWW membership. In this first edition, we’ll cover some ways that individual Wobblies can increase their participation in the One Big Union through developing their skills as workplace organizers. Future editions will focus on branches, committees, and other parts of the union. If you think of some additions to these lists, write them up and send them to Industrial Worker!

Take an Organizer Training

The IWW has two Organizer Trainings: the OT101 and the OT102. In the OT101, trainees learn the basic techniques of starting a workplace organizing committee. The committee meets regularly and plans direct actions on the job to build power and address grievances. The training is revised every few years based on the experiences of IWW organizers. We keep the stuff that is working and change the stuff that has been falling short. It’s also a really great way to get in touch with other Wobblies who are organizing their workplaces.

The 102 builds off of the 101. Once you have a committee up and running, you’ll need to learn how to sustain it. Business unions will usually start a committee and then once it’s up and running, they will petition the employer for recognition or they will file for a union election with the government. The IWW is a revolutionary union though. We don’t need or want the government to intervene in order to provide stability. We maintain our momentum through practicing better internal democracy and through recruiting more workers to take part in bigger workplace actions. You should take the 102 early on because it gets more into the details of practicing direct democracy, escalating direct actions, and sustaining your committee. It’s important to incorporate healthy committee practices and strategic planning at the early stages of a campaign. Our greatest weapon is solidarity and these trainings teach the nuts and bolts of Solidarity Unionism.

Start Organizing Your Workplace

There are all sorts of benefits that you and the union can get from organizing your own workplace, even if you just take the initial steps. When you start building good organizing habits, they will start to come more naturally over time. Getting people’s contact information will feel less awkward and you will start drawing your maps in more detail. One-on-one conversations with coworkers will flow more smoothly the more practice you get. And so even if you only make a small amount of progress at one job, you can build off of that experience at future jobs.

Take Another Training

No two trainings are ever the same! Each time, you will be learning from different trainers and with a different set of trainees. They all bring unique training styles and organizing stories. And let’s be honest with ourselves: each training is 16 hours worth of material. We are never gonna memorize it all after one take, or even two for that matter. Take lots of trainings and have fun with them!

Become a Trainer

Organizer Trainers are credentialed by the union to give our official trainings. You can draw from your experiences to give a personal touch to your trainings. It can be inspiring for trainees to hear personal stories from the front lines, even if it is just you showing a map or social chart from one of your workplaces. When you become an IWW trainer, you will be paired up with other trainers to do trainings and so you get to learn from their teaching styles and experiences. It’s a great way to learn new lessons and to pass along your learning experiences in the union.

The Organizer Training Committee (OTC) can train you to be an OT101 Trainer, an OT102 Trainer and a Training For Trainers (T4T) Trainer. There’s a leveling up system for trainers as well. First off, you can’t become a trainer unless you have taken the training. So in order to become a 101 Trainer, you should have taken the training a few times and put it to use in your own workplace. Same for the 102 and to be a T4T Trainer. At the end of each T4T, you will be reviewed by your trainers and they will decide if and how you will be credentialed.

At each T4T, you will learn some new training techniques, but it is assumed that you are coming in with some familiarity with the curriculum. This is why it’s good to have taken the training a few times and to have gained some first hand organizing experience. Don’t worry about knowing every single detail; you will get a better grasp the more trainings you do, and when you start as a trainer you will be paired with a more experienced trainer. On the flipside however, if your trainers don’t think you are ready, they aren’t obligated to credential you and they might recommend you go to another training and take another T4T.

Keep Organizing!

The more we organize and train other Wobblies to organize, the better organizers and trainers we become. Sometimes a campaign might only get so far as being able to draw up a social chart, but then you can use that social chart when you train other IWW members to do it! Maybe you participated in a direct action that flopped. You can turn that into a learning experience by debriefing with your coworkers or by writing about it. The more we learn to tackle the smaller hurdles, the better prepared we are to take on the next ones and to bring more Wobblies with us. Keep fighting the good fight and never stop leveling up!

301 notes

·

View notes

Note

oooooh what do you for ao3 now that you’ve moved on from wrangling?

I'm co-chair of the Development & Membership committee. (And somewhat on the Volunteers & Recruitment committee, it's complicated). DevMem is actually the first committee I joined: I picked up wrangling a year or so in, but had to drop it when I changed jobs.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

J.5.1 What is community unionism?

Community unionism is our term for the process of creating participatory communities (called “communes” in classical anarchism) within the current society in order to transform it.

Basically, a community union is the creation of interested members of a community who decide to form an organisation to fight against injustice and improvements locally. It is a forum by which inhabitants can raise issues that affect themselves and others and provide a means of solving these problems. As such, it is a means of directly involving local people in the life of their own communities and collectively solving the problems facing them as both individuals and as part of a wider society. In this way, local people take part in deciding what effects them and their community and create a self-managed “dual power” to the local and national state. They also, by taking part in self-managed community assemblies, develop their ability to participate and manage their own affairs, so showing that the state is unnecessary and harmful to their interests. Politics, therefore, is not separated into a specialised activity that only certain people do (i.e. politicians). Instead, it becomes communalised and part of everyday life and in the hands of all.

As would be imagined, like the participatory communities that would exist in an anarchist society (see section I.5), the community union would be based upon a mass assembly of its members. Here would be discussed the issues that effect the membership and how to solve them. Thus issues like rent increases, school closures, rising cost of living, taxation, cuts and state-imposed “reforms” to the nature and quality of public services, utilities and resources, repressive laws and so on could be debated and action taken to combat them. Like the communes of a future anarchy, these community unions would be confederated with other unions in different areas in order to co-ordinate joint activity and solve common problems. These confederations would be based upon self-management, mandated and recallable delegates and the creation of administrative action committees to see that the memberships decisions are carried out.

The community union could also raise funds for strikes and other social protests, organise pickets, boycotts and generally aid others in struggle. By organising their own forms of direct action (such as tax and rent strikes, environmental protests and so on) they can weaken the state while building an self-managed infrastructure of co-operatives to replace the useful functions the state or capitalist firms currently provide. So, in addition to organising resistance to the state and capitalist firms, these community unions could play an important role in creating an alternative economy within capitalism. For example, such unions could have a mutual bank or credit union associated with them which could allow funds to be gathered for the creation of self-managed co-operatives and social services and centres. In this way a communalised co-operative sector could develop, along with a communal confederation of community unions and their co-operative banks.

Such community unions have been formed in many different countries in recent years to fight against numerous attacks on the working class. In the late 1980s and early 1990s groups were created in neighbourhoods across Britain to organise non-payment of the Conservative government’s Community Charge (popularly known as the poll tax, this tax was independent on income and was based on the electoral register). Federations of these groups were created to co-ordinate the struggle and pull resources and, in the end, ensured that the government withdrew the hated tax and helped push Thatcher out of government. In Ireland, similar groups were formed to defeat the privatisation of the water industry by a similar non-payment campaign in the mid-1990s.

However, few of these groups have been taken as part of a wider strategy to empower the local community but the few that have indicate the potential of such a strategy. This potential can be seen from two examples of libertarian community organising in Europe, one in Italy and another in Spain, while the neighbourhood assemblies in Argentina show that such popular self-government can and does develop spontaneously in struggle.

In Southern Italy, anarchists organised a very successful Municipal Federation of the Base (FMB) in Spezzano Albanese. This organisation, in the words of one activist, is “an alternative to the power of the town hall” and provides a “glimpse of what a future libertarian society could be.” Its aim is “the bringing together of all interests within the district. In intervening at a municipal level, we become involved not only in the world of work but also the life of the community … the FMB make counter proposals [to Town Hall decisions], which aren’t presented to the Council but proposed for discussion in the area to raise people’s level of consciousness. Whether they like it or not the Town Hall is obliged to take account of these proposals.” In addition, the FMB also supports co-operatives within it, so creating a communalised, self-managed economic sector within capitalism. Such a development helps to reduce the problems facing isolated co-operatives in a capitalist economy — see section J.5.11 — and was actively done in order to “seek to bring together all the currents, all the problems and contradictions, to seek solutions” to such problems facing co-operatives. [“Community Organising in Southern Italy”, pp. 16–19, Black Flag, no. 210, p. 17 and p. 18]

Elsewhere in Europe, the long, hard work of the C.N.T. in Spain has also resulted in mass village assemblies being created in the Puerto Real area, near Cadiz. These community assemblies came about to support an industrial struggle by shipyard workers. One C.N.T. member explains: “Every Thursday of every week, in the towns and villages in the area, we had all-village assemblies where anyone connected with the particular issue [of the rationalisation of the shipyards], whether they were actually workers in the shipyard itself, or women or children or grandparents, could go along … and actually vote and take part in the decision making process of what was going to take place.” With such popular input and support, the shipyard workers won their struggle. However, the assembly continued after the strike and “managed to link together twelve different organisations within the local area that are all interested in fighting … various aspects” of capitalism including health, taxation, economic, ecological and cultural issues. Moreover, the struggle “created a structure which was very different from the kind of structure of political parties, where the decisions are made at the top and they filter down. What we managed to do in Puerto Real was make decisions at the base and take them upwards.” [Anarcho-Syndicalism in Puerto Real: from shipyard resistance to direct democracy and community control, p. 6]

More recently, the December 2001 revolt against neo-liberalism in Argentina saw hundreds of neighbourhood assemblies created across the country. These quickly federated into inter-barrial assemblies to co-ordinate struggles. The assemblies occupied buildings, created communal projects like popular kitchens, community centres, day-care centres and built links with occupied workplaces. As one participant put it: “The initial vocabulary was simply: Let’s do things for ourselves, and do them right. Let’s decide for ourselves. Let’s decide democratically, and if we do, then let’s explicitly agree that we’re all equals here, that there are no bosses … We lead ourselves. We lead together. We lead and decide amongst ourselves … no one invented it … It just happened. We met one another on the corner and decided, enough! … Let’s invent new organisational forms and reinvent society.” Another notes that this was people who “begin to solve problems themselves, without turning to the institutions that caused the problems in the first place.” The neighbourhood assemblies ended a system in which “we elected people to make our decisions for us … now we will make our own decisions.” While the “anarchist movement has been talking about these ideas for years” the movement took them up “from necessity.” [Marina Sitrin (ed.), Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina, p. 41 and pp. 38–9]

The idea of community organising has long existed within anarchism. Kropotkin pointed to the directly democratic assemblies of Paris during the French Revolution> These were “constituted as so many mediums of popular administration, it remained of the people, and this is what made the revolutionary power of these organisations.” This ensured that the local revolutionary councils “which sprang from the popular movement was not separated from the people.” In this popular self-organisation “the masses, accustoming themselves to act without receiving orders from the national representatives, were practising what was described later on as Direct Self-Government.” These assemblies federated to co-ordinate joint activity but it was based on their permanence: “that is, the possibility of calling the general assembly whenever it was wanted by the members of the section and of discussing everything in the general assembly.” In short, “the Commune of Paris was not to be a governed State, but a people governing itself directly — when possible — without intermediaries, without masters” and so “the principles of anarchism … had their origin, not in theoretic speculations, but in the deeds of the Great French Revolution.” This “laid the foundations of a new, free, social organisation”and Kropotkin predicted that “the libertarians would no doubt do the same to-day.” [Great French Revolution, vol. 1, p. 201, p. 203, pp. 210–1, p. 210, p. 204 and p. 206]

In Chile during 1925 “a grass roots movement of great significance emerged,” the tenant leagues (ligas do arrendatarios). The movement pledged to pay half their rent beginning the 1st of February, 1925, at huge public rallies (it should also be noted that “Anarchist labour unionists had formed previous ligas do arrendatarios in 1907 and 1914.”). The tenants leagues were organised by ward and federated into a city-wide council. It was a vast organisation, with 12,000 tenants in just one ward of Santiago alone. The movement also “press[ed] for a law which would legally recognise the lower rents they had begun paying .. . the leagues voted to declare a general strike … should a rent law not be passed.” The government gave in, although the landlords tried to get around it and, in response, on April 8th “the anarchists in Santiago led a general strike in support of the universal rent reduction of 50 percent.” Official figures showed that rents “fell sharply during 1915, due in part to the rent strikes” and for the anarchists “the tenant league movement had been the first step toward a new social order in Chile.” [Peter DeShazo, Urban Workers and Labor Unions in Chile 1902–1927, p. 223, p. 327, p. 223, p. 225 and p. 226] As one Anarchist newspaper put it:

“This movement since its first moments had been essentially revolutionary. The tactics of direct action were preached by libertarians with highly successful results, because they managed to instil in the working classes the idea that if landlords would not accept the 50 percent lowering of rents, they should pay nothing at all. In libertarian terms, this is the same as taking possession of common property. It completes the first stage of what will become a social revolution.” [quoted by DeShazo, Op. Cit., p. 226]

A similar concern for community organising and struggle was expressed in Spain. While the collectives during the revolution are well known, the CNT had long organised in the community and around non-workplace issues. As well as neighbourhood based defence committees to organise and co-ordinate struggles and insurrections, the CNT organised various community based struggles. The most famous example of this must be the rent strikes during the early 1930s in Barcelona. In 1931, the CNT’s Construction Union organised a “Economic Defence Commission” to organise against high rents and lack of affordable housing. Its basic demand was for a 40% rent decrease but it also addressed unemployment and the cost of food. The campaign was launched by a mass meeting on May 1st, 1931. A series of meetings were held in the various working class neighbourhoods of Barcelona and in surrounding suburbs. This culminated in a mass meeting held at the Palace of Fine Arts on July 5th which raised a series of demands for the movement. By July, 45,000 people were taking part in the rent strike and this rose to over 100,000 by August. As well as refusing to pay rent, families were placed back into their homes from which they had been evicted. The movement spread to a number of the outlying towns which set up their own Economic Defence Commissions. The local groups co-ordinated actions their actions out of CNT union halls or local libertarian community centres. The movement faced increased state repression but in many parts of Barcelona landlords had been forced to come to terms with their tenants, agreeing to reduced rents rather than facing the prospect of having no income for an extended period or the landlord simply agreed to forget the unpaid rents from the period of the rent strike. [Nick Rider, “The Practice of Direct Action: the Barcelona rent strike of 1931”, For Anarchism, David Goodway (ed.), pp. 79–105] As Abel Paz summarised:

“Unemployed workers did not receive or ask for state aid … The workers’ first response to the economic crisis was the rent, gas, and electricity strike in mid-1933, which the CNT and FAI’s Economic Defence Committee had been laying the foundations for since 1931. Likewise, house, street, and neighbourhood groups began to turn out en masse to stop evictions and other coercive acts ordered by the landlords (always with police support). The people were constantly mobilised. Women and youngsters were particularly active; it was they who challenged the police and stopped the endless evictions.” [Durrutu in the Spanish Revolution, p. 308]

In Gijon, the CNT “reinforced its populist image by … its direct consumer campaigns. Some of these were organised through the federation’s Anti-Unemployment Committee, which sponsored numerous rallies and marches in favour of ‘bread and work.’ While they focused on the issue of jobs, they also addressed more general concerns about the cost of living for poor families. In a May 1933 rally, for example, demonstrators asked that families of unemployed workers not be evicted from their homes, even if they fell behind on the rent.” The “organisers made the connections between home and work and tried to draw the entire family into the struggle.” However, the CNT’s “most concerted attempt to bring in the larger community was the formation of a new syndicate, in the spring of 1932, for the Defence of Public Interests (SDIP). In contrast to a conventional union, which comprised groups of workers, the SDIP was organised through neighbourhood committees. Its specific purpose was to enforce a generous renters’ rights law of December 1931 that had not been vigorously implemented. Following anarchosyndicalist strategy, the SDIP utilised various forms of direct action, from rent strikes, to mass demonstrations, to the reversal of evictions.” This last action involved the local SDIP group going to a home, breaking the judge’s official eviction seal and carrying the furniture back in from the street. They left their own sign: ”opened by order of the CNT.” The CNT’s direct action strategies “helped keep political discourse in the street, and encouraged people to pursue the same extra-legal channels of activism that they had developed under the monarchy.” [Pamela Beth Radcliff, From mobilization to civil war, pp. 287–288 and p. 289]

In these ways, grassroots movements from below were created, with direct democracy and participation becoming an inherent part of a local political culture of resistance, with people deciding things for themselves directly and without hierarchy. Such developments are the embryonic structures of a world based around participation and self-management, with a strong and dynamic community life. For, as Martin Buber argued, ”[t]he more a human group lets itself be represented in the management of its common affairs … the less communal life there is in it and the more impoverished it becomes as a community.” [Paths in Utopia, p. 133]

Anarchist support and encouragement of community unionism, by creating the means for communal self-management, helps to enrich the community as well as creating the organisational forms required to resist the state and capitalism. In this way we build the anti-state which will (hopefully) replace the state. Moreover, the combination of community unionism with workplace assemblies (as in Puerto Real), provides a mutual support network which can be very effective in helping winning struggles. For example, in Glasgow, Scotland in 1916, a massive rent strike was finally won when workers came out in strike in support of the rent strikers who been arrested for non-payment. Such developments indicate that Isaac Puente was correct:

“Libertarian Communism is a society organised without the state and without private ownership. And there is no need to invent anything or conjure up some new organisation for the purpose. The centres about which life in the future will be organised are already with us in the society of today: the free union and the free municipality [or Commune].

”The union: in it combine spontaneously the workers from factories and all places of collective exploitation.

“And the free municipality: an assembly … where, again in spontaneity, inhabitants … combine together, and which points the way to the solution of problems in social life …

“Both kinds of organisation, run on federal and democratic principles, will be sovereign in their decision making, without being beholden to any higher body, their only obligation being to federate one with another as dictated by the economic requirement for liaison and communications bodies organised in industrial federations.

“The union and the free municipality will assume the collective or common ownership of everything which is under private ownership at present [but collectively used] and will regulate production and consumption (in a word, the economy) in each locality.

“The very bringing together of the two terms (communism and libertarian) is indicative in itself of the fusion of two ideas: one of them is collectivist, tending to bring about harmony in the whole through the contributions and co-operation of individuals, without undermining their independence in any way; while the other is individualist, seeking to reassure the individual that his independence will be respected.” [Libertarian Communism, pp. 6–7]

The combination of community unionism, along with industrial unionism (see next section), will be the key to creating an anarchist society, Community unionism, by creating the free commune within the state, allows us to become accustomed to managing our own affairs and seeing that an injury to one is an injury to all. In this way a social power is created in opposition to the state. The town council may still be in the hands of politicians, but neither they nor the central government would be able to move without worrying about what the people’s reaction might be, as expressed and organised in their community assemblies and federations.

#community unionism#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Migrant farm workers in Virginia are organizing for better workplace treatment.

The Farm Labor Organizing Committee has developed a union with two types of membership. The first is for people with H2A visas who come from other countries to work in the United States during agricultural seasons. The other is for community members or family members of farm workers. The group has relied on the immigrant community to alert people about this union.

Hilda Castaneda, an organizer for FLOC, said this has been needed for a long time.

"For 30 years we don't have, officially, any organization or something that can come in and help us and offer, because there's a lot in Richmond," she said. "But, they're not coming and continuing getting any kinds of programs to us."

Workers want relief from forced overtime and hope organizing will achieve that. It was almost handled at the state level last year when Virginia's General Assembly considered a bill giving farm workers the right to sue for unpaid wages. However, it was changed to exclude farmworkers before it was passed.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world’s largest Muslim-majority nation is set to normalize relations with the Jewish State, according to a report Thursday by the Ynet news outlet.

The deal was reportedly reached after three months of secret talks between Indonesia, Israel and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which the Jakarta government wants to join, and which Israel belongs to.

After weeks of talks, the OECD and Indonesia agreed that Jakarta would have to establish diplomatic ties with Israel prior to the vote to approve its entry to the organization.

Indonesia has opposed Israel’s military operation in Gaza that followed the invasion and war launched by Hamas on October 7. Jakarta also supported South Africa’s lawsuit against Israel at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide.

Earlier this week, however, for the first time an Indonesian aircraft participated in an airdrop of humanitarian aid into Gaza. It is also the first time an Indonesian aircraft has flown through Israeli airspace.

“I want to sincerely thank you for our very constructive discussions over the past few weeks and for Israel’s important decision to allow talks between Indonesia and the OECD regarding its joining the organization,” OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann wrote to Foreign Minister Israel Katz in a formal letter notifying him of the agreement.

“As discussed with you and Prime Minister Netanyahu, the precondition of the start of diplomatic relations prior to any decision to invite Indonesia as a member of the organization is included as a clause in the OECD Council’s official conclusions for the talks … As we discussed, this process will have a positive long-term impact, so it was crucial to allow the process to begin,” he added.

New membership in the OECD requires the establishment of diplomatic relations with all of the organization’s 38 member states, in addition to unanimous approval of the application.

It’s not a simple process. Indonesia’s legislation, policies and regulations will have to undergo review by 26 different committees — a process that could take up to three years — before receiving approval to join the OECD. Each of those committees will include an Israeli expert who will have the right to veto Indonesia’s accession if the country fails to make good on its promise to normalize ties with the Jewish State.

“I am pleased to announce the Council has officially agreed to the clear and explicit early conditions according to which Indonesia must establish diplomatic relations with all OECD member countries before any decision is made to admit it to the OECD,” Cormann wrote two weeks ago in a letter approved by Indonesia before it was sent to Israeli Foreign Minister Israel Katz.

“Furthermore, any future decision to accept Indonesia as a member of the organization will require unanimous agreement among all member countries, including Israel. I am convinced that this provides you with assurance at this crucial point,” the letter read.

In response, Katz sent a letter back to Cormann, welcoming the news.

“I share your expectation that this process will constitute a change for Indonesia, as I anticipate a positive change in its policy toward Israel, especially abandoning its hostile policy toward it, leading the path to full diplomatic relations between all sides,” Katz wrote.

#palestine#indonesia#israel#oecd#free palestine#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#boycott divest sanction#genocide#ethnic cleansing

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

NATO is seeking to expand its cooperation structures globally and also intensify its cooperation with Jordan, Indonesia and India. A “NATO-Indonesia meeting” was held yesterday (Wednesday) on the sidelines of the NATO foreign ministers’ meeting in Brussels – a follow-up to talks between Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in mid-June 2022. Last week, a senior NATO official visited Jordan’s capital Amman to promote the establishment of a NATO liaison office. Already back in June, a US Congressional Committee focused on China, had advocated linking India more closely to NATO. India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, however, quickly rejected the suggestion. NATO diplomats are quoted saying that the Western military alliance could conceive of cooperating with South Africa or Brazil, for example. These plans would escalate the West’s power struggle against Russia and China, while non-Western alliances such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) are expanding their membership.

Already since some time, NATO has been seeking to expand its cooperation structures into the Asia-Pacific region, for example to include Japan. Early this year, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg was in Tokyo, among other things, to sign a joint declaration with Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.[1] In addition, it is strengthening its cooperation with South Korea, whose armed forces are participating in NATO cyber defense and are to be involved more intensively in future conventional NATO maneuvers.[2] Japan’s prime minster and South Korea’s president have already regularly attended NATO summits. The Western military alliance is also extending its cooperation with Australia and New Zealand. This development is not without its contradictions. France, for example, opposes the plan to establish a NATO liaison office in Japan, because it considers itself an important Pacific power and does not want NATO’s influence to excessively expand in the Pacific. Nevertheless, the Western military alliance is strengthening its presence in the Asia-Pacific region – with maneuvers conducted by its member states, including Germany (german-foreign-policy.com reported.[3]).[...]

NATO has been cooperating with several Mediterranean countries since 1994 within the framework of its Mediterranean Dialogue and also since 1994, with several Arab Gulf countries as part of its Istanbul Cooperation Initiative.[4] However, the cooperation is not considered very intensive. At the beginning of this week, NATO diplomats have been quoted saying “we remain acutely aware of developments on our southern flank,” and are planning appropriate measures. The possibility of establishing a Liaison Office in Jordan is being explored “as a move to get closer to the ground and develop the relationship in the Middle East.[5] Last week, a senior NATO official visited Jordan’s capital Amman to promote such a liaison office.[6][...]

NATO diplomats informed the online platform “Euractiv” that “many members of the Western military alliance believe that political dialogue does not have to be limited to the southern neighborhood. One can also seek cooperation with states further away. Brazil, South Africa, India, and Indonesia are mentioned as examples.[7][...]

In a paper containing strategic proposals for the U.S. power struggle against China, the Committee also advocated strengthening NATO’s cooperation with India.[8] The proposal caused a stir in the run-up to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Washington on June 22. He was able to draw on the fact that India is cooperating militarily in the Quad format with the USA as well as NATO partners Japan and Australia in order to gain leverage against China. Close NATO ties could also facilitate intelligence sharing, allowing New Delhi to access advanced military technology.[9] India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, however, rejected Washington’s proposal, stating that the “NATO template does not apply to India”.[10] Indian media explained that New Delhi was still not prepared to be pitted against Russia and to limit its independence.[11] Both would be entailed in close ties to NATO.

The efforts to link third countries around the world more closely to NATO are being undertaken at a time when not only western countries are escalating their power struggles against Russia and above all against China and are therefore tightening their alliance structures. They are also taking place when non-Western alliances are gaining ground. This is true not only for the BRICS, which decided, in August, to admit six new members on January 1, 2024 (german-foreign-policy.com reported [12]). This is also true for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a security alliance centered around Moscow and Beijing that has grown from its original six to currently nine members, including India, Pakistan and Iran, and continues to attract new interested countries. In addition to several countries in Southern Asia and the South Caucasus, SCO “dialogue partners” now include Turkey, Egypt and five Arabian Peninsula states, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. Iin light of the BRICS expansion, the admission of additional countries as full SCO members is considered quite conceivable. Western dominance will thus be progressively weakened.[13]

12 Oct 23

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In Italy, there was considerable dissension between Britain and the United States over the nature of the provisional government. The British, considering themselves to have the paramount interest in Italy, claimed the right to play the dominant role in organizing the new government; FDR refused to concede this. But both Western Allies agreed that the Left should not be allowed to fill the gap left by the collapse of Mussolini’s regime and gradually retreating German occupation forces in the north; despite the publicly stated goal of “defascistization,” both British and American officers found it far easier in practice “to leave existing officeholders at their posts,” and the British (soon imitated by the Americans) used “the existing administrative system, including the police.” Only the socialists were strongly in favor of totally purging fascists from the administration, and even the Communist Party was “lukewarm” on the subject.[149]

The primary dispute between the Western Allies concerned Churchill’s desire to establish a reactionary regime under King Victor Emmanuel III and Marshal Badoglio (a fascist collaborator until 1943), as the “sole barrier to ‘rampant Bolshevism’.”[150] Immediately following Roosevelt’s March 1944 demand that Badoglio be removed because of his unpopularity, Stalin came to Churchill’s aid by recognizing Badoglio’s government; shortly thereafter the Communist Party announced its intent to participate in the government with no conditions.[151]

Occupation authorities banned electoral activity “during the period of military government,” and the military authorities complied with Badoglio’s request “to censor all criticism of the king, the government, and the army.”[152]

(...)

Italian antifascist forces and their base of public support were predictably dissatisfied with this arrangement. Badoglio and Victor Emmanuel

were universally regarded as remnants of the equally widely hated fascist order. From the moment they signed the “long surrender,” until the end of the year, opposition to the Badoglio government grew in intensity as part of the sustained political crisis that characterized Italian politics for the next two years.[154]

With the backing of Stalin and the Comintern, PCI leader Togliatti was able to enforce a non-revolutionary and cooperativist line over the objections of a much more radical rank and file. However, he did not purge the Party’s mass membership of dissidents — a policy that left it ideologically quite diverse and laid the way for the future emergence of Eurocommunism.[155]

When the Allies entered Rome in June 1944, the Committee of National Liberation refused to accept Badoglio as head of government. Churchill was furious, and — joined by Stalin — raised the issue of whether this was even legal under the terms of the surrender. But the new prime minister, Bonomi — former head of the Committee of National Liberation and a moderate constitutional monarchist — excluded Badoglio from the Cabinet, with the approval of the United States.[156]

Pietro Nenni’s Socialist Party and the leftist Action Party both soon became disaffected from the Bonomi government over its lackadaisical approach to defascistization, although the Communist Party remained neutral. Meanwhile the United States finally and unambiguously won the competition for influence in Italy, as Bonomi developed closer ties with Roosevelt and expressed his desire to be integrated into Washington’s vision of a postwar economic order.[157]

When Allied forces reached Rome, leftist antifascist partisans got considerably harsher treatment than fascist military and police forces had received in the south.

To the Allied soldiers reaching the Rome region the experience was strange indeed. Armed Italians, often in red shirts, waving revolutionary banners, greeted them, frequently after they had set up their own local administrations. The Allied armies pushed some Partisans aside, and even threatened them with the firing squad; they arrested many and threw them into prisons. “The problem is a novel one and is bound to be met with in further intensity the further north the advance goes,” one political officer reported in June, and whether these men were elected or not, Anglo-American officers decided, the Partisans would have to place themselves under occupation authority. The basic policy urged “tact and sympathy” but the Partisans were to surrender their arms; if possible, employment was to be found for former “patriots,” as the military authorities preferred calling them. Indeed, the Occupation followed the carrot and stick policy, those Partisans refusing to hand in arms facing prison, those cooperating being given special food rations and, if available, jobs, though not usually in the army and rarely in the police. Unemployed, the Partisan was a “menace,” armed a danger: “One thinks of the troubles of Yugoslavia and Greece in this connection,” one regional commander observed to his colleagues.[158]

The Western Allies also faced the problem of how to deal with CLNAI partisans in the north, which was considerably more complicated because they were more numerous, and were directly engaged in combat with German forces.

The problem of the Resistance, the Western leaders understood by the end of summer 1944, was not in controlling that small part of it liberated in the Rome area, but in reducing the potential danger that the very much larger groups still on Nazi-held territory posed.[159]

The partisans had organized a strike wave in the industrial cities in late 1943, in summer 1944 were tying down a sizeable German combat force, and considered themselves the legitimate governing authority in the region.[160] The British and Americans greatly feared that, in the event the German occupation forces withdrew, leftist partisans would take over the northern cities before Anglo-American military forces could move in. While the Communist Party was willing to appease the Western Allies, the socialists threatened to create a socialist separatist regime in the north after German withdrawal — a position that contributed greatly to their popularity compared to the communists.[161]

Throughout the summer [the Allies] sharply reduced the quantity of arms dropped to the Resistance, which had never been substantial in the first place. For purely military reasons — the Resistance was tying down as many as fourteen Axis divisions at one time — the Anglo-American authorities renewed sending in a somewhat greater quantity at the end of September, but OSS agents in Partisan territory were able to have non-Communist Partisans receive first priority. Then, when the Allied military decided the Italian campaign had gone as far as it might for the winter and should not detract from the war in Western Europe, it was possible to regard the problem of the Resistance as mainly political. With constant references to Greece, Yugoslavia, and the threat of Bolshevism everywhere, the military authorities embarked on a Resistance policy that was both military and political in its dimensions.

On November 13, General Alexander, Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, broadcast a message to the Resistance urging them, in light of winter conditions, not to engage in large-scale military operations, to save their supplies and await orders, and restrict their activities to smaller operations. To the Germans it was a notice that the Allies would not initiate a winter campaign, freeing the Nazis for other tasks, including greater efforts in wiping out the Partisans. The Resistance was demoralized and significantly only the Communist leaders in the north attempted to paint the best possible face on Alexander’s message. The Germans and fascists were now in a position to consolidate their power, and a widespread hunt resulted in an unprecedented elimination of Resistance leaders and members. Defections, death, and reprisals were everywhere.[162]

Allen Dulles, Swiss director of the OSS, actually entered into clandestine negotiations with the Nazi occupation forces and secured their agreement not to surrender to the CLNAI, and to maintain essential services and law and order until they could surrender to arriving Anglo-American forces.[163]

Despite this betrayal, German units disintegrated from low morale; armed workers took over the major northern cities and occupied the factories in April 1945, and then handed over control to the CLNAI. Ignoring the commands of communist leaders, partisans engaged in mass reprisals — including summary execution — of fascists.[164]

The Bonomi government itself never directly addressed or resolved the status of the area under CLNAI political control, preferring to treat CLNAI as “the directing organization of the Resistance in the north.” The Socialist Party and Action Party, however, hoped to leave them in territorial control as “the basis of a reconstructed political order” centered on workers’ councils.[165]

Togliatti helped salvage the situation for the Allies by refusing to side with the Socialists, and insisting on national unity — thus sabotaging the ability of the CLNAI to pursue regional separatism on their own.[166]

Finally, on December 7, the CLNAI signed an agreement — the Protocols of Rome — with humiliating terms:

In return for the promise of financial subsidies, food, clothing, and arms, the CLNAI agreed to subordinate itself to the Supreme Allied Commander, not to appoint a military head of the CLNAI unacceptable to him, to hand over power to the Allied military government upon its arrival in the north, and to follow the orders of the military government before and after liberation…. The Allies obtained assurances from the Resistance that it would not create a revolution.[167]

When Allied forces reached areas of CLNAI control, they removed them from power, and revoked all decrees.[168]

-Kevin Carson, "The Undeclared Condominium: The USSR As Partner in a Conservative World Order" (2023)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The president of the United Auto Workers (UAW) labor union leading the ongoing strike against the largest three U.S. automakers earned hundreds of thousands of dollars last year, placing him squarely in a top earning percentile in his home state, according to financial filings reviewed by FOX Business.

Shawn Fain — who was elected to lead UAW in March and has been a firebrand proponent of autoworkers — has at least two significant streams of revenue, the filings showed, earning $187,259 a year leading a UAW non-profit training program and another $160,130 per year in his previous role of administrative assistant at the union. Fain's UAW salary likely jumped well above $200,000 per year upon taking over as the union's president earlier this year.

"The Big Three want you to believe that what we are asking for is dangerous and unrealistic," Fain remarked in a UAW video released this week. "What is truly unrealistic is to keep making record profits year after year and then think that the workers who made those profits are just going to settle for scraps. What is truly dangerous is for corporations and the billionaire class to continue making out like bandits while the working class gets left further and further behind."

"That is why these companies and the corporate media are so desperate to try and convince the American people that unions are the problem," he continued. "We are not the problem. This so-called ‘competition’ is the problem. Corporate greed is the problem. Our solidarity is the solution."

Fain's annual salary of $347,389 places him in the top 5% of earners in his home state of Indiana where, according to a Forbes analysis, individuals whose salary exceeds $192,928 per year are in the top 5%.

If Fain's new salary as president matches his predecessor, former UAW President Ray Curry, his union income increased to $267,126 and his overall salary — including what he earns from the non-profit UAW Chrysler Skill Development & Training Program — increased to $454,385, a salary that would make him a top 1% earner.

Meanwhile, Fain has established himself as the face of the ongoing strike against Ford Motor Company, General Motors and Stellantis, even appearing alongside President Biden for one rally in which he compared automakers to Nazi Germany. The union boss has even donned an "eat the rich" T-shirt at protests and rallies.

"They look at me and they see some redneck from Indiana," Fain said during a rally last week. "They look at you and see somebody they would never have over for dinner or let ride on their yacht or let fly on their private jet. They think they know us. But us autoworkers know better."

And while striking UAW members are making just $500 a week in substitute pay from the union while they strike, ABC News reported, it is unclear whether Fain himself has taken a pay cut.

In an open letter to Fain sent Tuesday, the Mack Trucks Workers Rank-and-File Committee demanded the UAW bump striking workers' pay to $750 a week and that leaders including Fain should accept a pay cut taking their salary to the same level as strikers.

"President Fain, if you are unwilling to meet these demands, which correspond to the demands of the membership, then you should step aside and turn over control of the union to the rank and file," the workers wrote to Fain. "It is, after all, we who have the 'final say.'"

"To our fellow autoworkers in the Big Three, we call on you to take up this fight yourselves and not allow your strike to be sabotaged by the UAW leadership," the open letter continued. "We have launched our strike in defiance of the apparatus, and we call on you to do the same."

On Wednesday, the UAW expanded its strike to Ford's most profitable truck plant in Kentucky. Although leaders have signaled progress in UAW's negotiations with Ford and the other two automakers, Fain has continued to say the companies are failing to meet the union's lofty demands on wages, a modified work week and pension benefits.

Fain did not immediately respond to FOX Business's request for comment.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meredith Mathews (September 14, 1919 - March 19, 1992) was a prominent social and civic leader in Seattle who was born in Thomaston, Georgia. He received a BS in Science from Wilberforce University. He pursued graduate studies at Ohio University.

He began a lifelong association with the YMCA as Director of the racially segregated Spring Street YMCA in Columbus, Ohio. He continued his professional career directing similar YMCAs in Oklahoma City and McAlester, Oklahoma.

He arrived in Seattle after being named Executive Director of the East Madison YMCA. This “Y” served the mostly African American community of central Seattle. The fundraising and business management skills he had developed in Oklahoma were used to expand services, memberships, and programs at this Seattle branch. A new facility was built after a successful Capital Funds Campaign under his leadership.

He was appointed Associate Executive of the Pacific Northwest Area Council of YMCAs. He was named Regional Executive of the Pacific Region of YMCAs and was responsible for the oversight of 126 facilities and programs in 11 states. He retired after 39 years of outstanding service to the YMCA.

He was involved in other civic and social organizations. He was active with the Central Area Committee for Civil Rights. He served on the boards of the Seattle Urban League and the Randolph Carter Family and Learning Center. He was a Mason, a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, and one of 11 founding members of the Alpha Omicron Boule of the Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity.

The YMCA and other community groups honored his service and his leadership. The YMCA of Greater Seattle Board of Directors named the East Madison YMCA the Meredith Mathews East Madison YMCA. This was the first YMCA facility in the Seattle metropolitan area to be named for an individual. His name was placed in the YMCA Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #alphaphialpha #sigmapiphi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The activities of A.T. Hill during these years provide an example of how many socialists at the Lakehead reacted to the changing circumstances in Canada. Like many, Hill had re-evaluated his ideological position following the end of the Winnipeg General Strike and during the tumultuous years when the One Big Union (OBU) and Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had fought for hegemony in the region. By early 1920, he no longer believed that either the syndicalism offered by the IWW or the variation espoused by the OBU would result in the social change he desired. Travelling to Superior, Wisconsin, where he had worked in the past as a harvester and lumber worker, he enrolled in the American Finnish Socialist Federation’s school. There he and fellow future prominent Finnish Canadian Communists fell under the influence of Emeli Parras, editor of Työmies and secretary of a local unit of the American Communist Party. Parras’s courses spurred Hill to join William Z. Foster and Charles Ruthenberg’s United Communist Party. Shortly after, he became one of its many members who flooded the Canadian borderlands speaking to workers about Leninism and the Communist movement.

At first, Communist efforts focused on former IWW strongholds and those towns and regions where growing dissatisfaction with the OBU was greatest. Hill began agitating in Fort Frances, Ontario. Gradually, building on his earlier reputation as an organizer throughout the Lakehead area, he became a leading radical throughout the region. Often pitting himself against William Arnberg, a former organizer for the OBU and now a Wobbly agitator, he argued that the Soviet state, as constructed by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, was a necessary precondition for the transformation of capitalism into socialism. Social Democratic Party of Canada (SDPC) activists such as Richard Loughead (also referred to as Lockhead), William Checkley, and Harry Bryan followed Hill in seeing the Communist Party as a way to preserve and develop the radicalism they had developed before 1918.

...