#designofeverydaythings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

“With the passage of time, the psychology of people stays the same, but the tools and objects in the world change.” – Donald A. Norman, The Design of Everyday Things – and Chairman of IDF’s Executive Board #donnorman #designofeverydaythings #ixd #psychology

0 notes

Quote

Two of the most important characteristics of good design are discoverability and understanding. Discoverability: Is it possible to even figure out what actions are possible and where and how to perform them? Understanding: What does it all mean? How is the product supposed to be used? What do all the different controls and settings mean?

0 notes

Photo

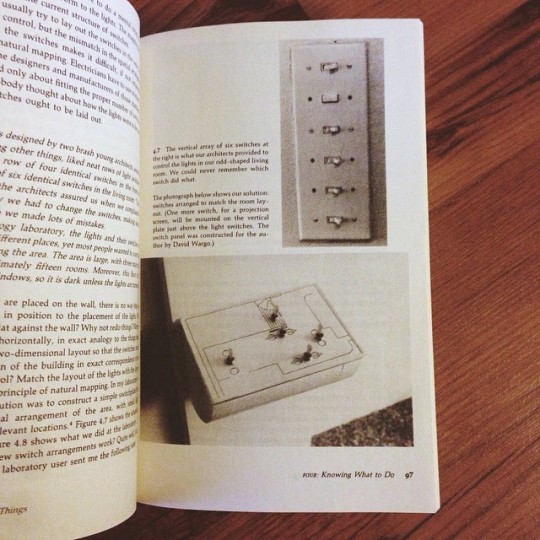

Genius. #DesignOfEverydayThings #DonaldNorman #1990

0 notes